Abstract

American democracy is currently heavily reliant on plurality in single-member districts, or PSMD, as a system of election. But public perceptions of fairness are often keyed to partisan proportionality, or the degree of congruence between each party’s share of the vote and its share of representation. PSMD has not tended to secure proportional outcomes historically, partially due to gerrymandering, where line-drawers intentionally extract more advantage for their side. But it is now increasingly clear that even blind PSMD is frequently disproportional, and in unpredictable ways that depend on local political geography. In this paper we consider whether it is feasible to bring PSMD into alignment with a proportionality norm by targeting proportional outcomes in the design and selection of districts. We do this mainly through a close examination of the “Freedom to Vote Test,” a redistricting reform proposed in draft legislation in 2021. We find that applying the test with a proportionality target makes for sound policy: it performs well in legal battleground states and has a workable exception to handle edge cases where proportionality is out of reach.

1 Introduction

Most American legislative elections are plurality contests in single-member districts, a system we will abbreviate by PSMD: the single candidate with the most votes is elected from each geographical district. This stands in contrast to much of the rest of the world, where legislatures are filled by a mechanism that has proportionality guarantees by design, such as a “party list” system that awards seats to political parties in proportion to their vote share. The positive case for PSMD as a system centers on the importance of local and regional choice, with voters directly choosing their representatives; PSMD offers the prospect that preferences that are in the minority on a statewide level can secure majority support in a smaller geography. However, it has long been observed that actual PSMD elections are routinely disproportional, and recent years have seen increasingly sophisticated modeling that shows that even blind PSMD—via randomized legally valid districts—is disproportional in ways that are unpredictable from state to state, because they depend on the precise spatial arrangement of vote preferences. Nevertheless, public perceptions of fair outcomes remain closely tied to proportionality, i.e. the degree of congruence between vote share and seat share. In this paper, we consider whether PSMD can be made compatible with a fairness norm calling for proportional outcomes. That is, it possible to counteract the central tendencies of party-blind districting and to expressly design districts that are likely to produce proportional representation?[1] Below, we address this question in highly practical terms, by considering how a test of gerrymandering could be administered in law, via the “FTV Test” set down in draft Congressional legislation in 2021.

That is, suppose a state were to adopt partisan proportionality as a goal in its law or guidelines for redistricting, reflecting a preference for a plan that is likely to elect a delegation with each party’s seat share approximating its vote share. Indeed, one state—Ohio—has proportionality written into its state constitution as a policy goal.[2] Is that a feasible goal for mapmakers? Or is this an unattainable goal—and therefore an unreasonable legal standard?

After regaining control of both houses of Congress in 2021, Democratic lawmakers attempted several times to pass a bill that would address redistricting. In particular, they sought to rein in partisan gerrymandering in the wake of the 2019 Rucho v. Common Cause Supreme Court decision that declared it non-justiciable in federal courts. Here is the proposed test from Senate Bill 2747, the “Freedom to Vote: John R. Lewis Act” (S.2747 – Freedom to Vote Act 2747), paraphrased succinctly. We will call it the FTV Test (See Appendix B for full text.)

According to a recognized metric of partisan fairness, a plan must yield nearly (within a set tolerance) the ideal /target seat share for each party in at least three out of a prescribed list of four recent elections.

The metric that sets the target was left unspecified, as we explore below, but the four elections were designated in the bill to be the two most recent contests for President and for U.S. Senate. If the test is failed—i.e. if the tolerance is exceeded in two or more of the four contests—this triggers a presumption that the plan is gerrymandered, which can then be rebutted by the state. But as an initial matter, this is an unabashedly simple and results-based (not intent-based) test.

In this paper we consider what kinds of fairness metrics are potentially suitable for use in the test, first discussing them in normative terms. Circling back to the motivating question above, we focus on the viability of using the FTV Test with a proportionality target. We focus on five states that had extensive legal challenges with a partisan gerrymandering component circa 2018: North Carolina (challenged in federal and state court), Maryland (federal), Pennsylvania (state), Texas (federal), and Wisconsin (federal).[3] We add Massachusetts, which is known to have a very uniform political geography, making the state a hard case for many fairness norms, as we will see below. We are armed with large collections of alternative districting plans generated by computer as well as alternative plans drawn by courts and journalists, and we use contemporaneous election data from the period preceding 2018. We will demonstrate that in the contested states, mapmakers can reasonably produce examples that satisfy the FTV Test for proportionality, suggesting that the test is not too stringent. Massachusetts give us an example where proportionality is out of reach, and is used here to illustrate that the FTV test handles that case well with the rebuttal element in its design. But of course this proposed policy aims to validate plans for adoption that are likely to retain their good properties into the future. This leads us to investigate whether plans that are near-proportional in an earlier election window will tend to remain so in subsequent years. The findings there are encouraging as well.

2 Proportionality and Other Ideals

2.1 Norms of Fairness

By design, the FTV Test leaves open an obvious question—what is the ideal seat share? Several possibilities might be considered. Let us denote by V the statewide share of the (major-party) vote that belongs to a political party, and by S their share of representation, for a given vote pattern and districting plan.

2.1.1 Normative possibilities for representational outcome

Proportionality. The ideal seats outcome in a given election is S = V.

Normative rationale: democracy means that public preferences should be converted to representation. This standard keys representation directly to the share of votes secured. As a standard for single-member districts, it seeks for the delegation as a whole to reflect statewide preferences while individual representatives reflect local preferences.

Efficiency gap. [4] The ideal seats outcome in a given election is S = 2V − ½.

Normative rationale: some amount of bonus for the party with more support may provide a more effective ability to legislate, particularly to avoid near-parity and a corresponding deadlock. In addition, an amplified advantage for the party with more support can make a system more responsive to shifts in voter preference, which inclines against entrenchment of incumbents. This standard proposes a double-bonus, in which every additional point of vote share deserves two points of seat share. This slope of two also corresponds to equalizing the parties’ “wasted votes” under some simplifying assumptions.

Ensemble mean. The ideal seats outcome in a given election is the average S over all the districting plans in an algorithmically generated “ensemble” of comparator plans.

Normative rationale: we are committed to districts because they can secure regional or neighborhood-specific representation, because they may allow for minority representation within a plurality system, and/or because they are supported by a long history. Since we want to eliminate distortions caused by partisan control of the lines, we should key our notion of fairness to the typical consequences of party-blind redistricting, effectively converting a procedural norm to a substantive norm.

We note that there are quite a few other notions of partisan fairness in the literature, in addition to other ways to operationalize the norms cited here.[5] The partisan symmetry family of metrics (which includes the mean-median gap, the partisan bias score, and so on) is particularly prominent, but these metrics do not identify a target or ideal seat share in a given election. Advocates of partisan symmetry, principally Gary King and collaborators, argue that this feature—that the scores are not prescriptive of seat outcomes—is a conceptual strength (see [Katz, King, and Rosenblatt 2020] and its references). Whether or not this is so, it means that symmetry scores can not be plugged into an outcome-oriented evaluation test like this one.[6] The same holds for declination (Warrington 2018), which is denominated in an abstract trigonometric unit (the arctangent of a certain angle in a plot of votes by district) that has no direct relationship to the seats outcome.[7]

Reasonable people could differ about which normative argument listed above is the most persuasive. We argue here for proportionality. The definition is straightforward, the intuitive case for the norm is clear, and there are no arbitrary or black-box elements in the construction of the standard.

By contrast, the slope of two in the efficiency gap standard is arguably somewhat arbitrary and in any case has counter-intuitive effects: for example, a proportional outcome is often labeled as a gerrymander according to EG (for instance, if a party has 60% of the seats and 60% of the representation, i.e. S = V = 0.6, this registers as a significant gerrymander against that party). Secondly, if a state had a 75–25 voting advantage for one party, then no matter how large the delegation, efficiency gap advocates would find a 100–0% sweep of the seats to be ideal. (For a discussion of general features of the EG metric, see for instance [Duchin and Bernstein 2017].).

There are at least two obstructions to enshrining an ensemble-based standard, like the ensemble mean described above, in a simple litmus test for gerrymandering. One is that there are many details of ensemble construction that can have subtle impacts on the representational outcomes. (Should county preservation be encouraged in the algorithm that draws districts, or not?—and if so, how? If the modeler aims to draw a representative sample of plans, from what probability distribution should it be drawn? and so on.) As ensemble practitioners ourselves, we find the method to be best suited to holistic hypothesis testing about the consequences of different operational frameworks of rules; ensembles are far less suitable for deriving a manageable (still less a canonical) ideal outcome. Without a close look at the design choices of the modeler, ensembles risk becoming a high-stakes black box. The second major issue is the glaring question of whether it is normatively sound to promote the central tendencies of PSMD to the status of an ideal. Districting algorithms can produce plans that are neutral with respect to partisan (and racial, and other) data, but clearly the facial neutrality of a procedure is no guarantee of the fairness of the outcome in any larger social or political sense.[8] Indeed, if we are persuaded from first principles that proportionality is a healthy goal, then well-designed ensembles give us a measure of just how much blind-PSMD falls short of fairness. In this article, we will use the method of ensembles to generate a batch of plans that we can scan for some desirable properties—that is, the algorithms are mainly engines of examples—but we will studiously resist the move that declares the typical outcome to be the ideal.

2.2 Quantitative Formulation of Disproportionality and Near-Proportionality

Definition 1.

Given a districting plan

where

For example, in North Carolina (k = 13 before the 2020 reapportionment), the 2016 Presidential election had V ≈ 0.520, i.e. very nearly 52% Republican vote share statewide. Under that cast vote pattern, 10/13 of the Congressional districts had Republican majorities, so the enacted plan under Pres16 has a disproportionality of 10/13 − 0.520 = 0.249, meaning that Republicans got more seats than their vote share by a huge margin, amounting to nearly a quarter of the delegation. This is a signed metric; a negative disprop would similarly indicate Republican disadvantage. While this score is built from just one election pattern, we will make use of as many statewide contests as are available—serially, not by averaging—to best understand the political geography of the state. Table 1 shows statistics from nine elections from the period leading up to 2018.

Given our districting plan

Disproportionality scores themselves do not vary continuously, but by jumps, since the S term must be one of 0, 1/k, 2/k, …, 1 for a delegation of size k. In particular, it will typically not be possible to get the seat share to exactly match the vote share. So instead of demanding a perfect score, we should hope that a plan scores a disproportionality sufficiently close to zero on a sequence of past elections.

Election results from a series of “up-ballot” statewide contests

| Election | Gov08 | Sen08 | Sen10 | Gov12 | Pres12 | Sen14 | Pres16 | Sen16 | Gov16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R vote share | 0.483 | 0.457 | 0.560 | 0.559 | 0.511 | 0.508 | 0.520 | 0.530 | 0.500 | |

| targets |

Proportional | 6.3 | 5.9 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 6.5 |

| EG = 0 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 6.8 | 6.7 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 6.5 | |

| Ensemble mean |

4.3 |

3.0 |

10.3 |

9.7 |

7.3 |

7.6 |

7.8 |

8.5 |

7.3 |

|

| Leg12 |

R seats | 8 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| R seat share | 0.615 | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.769 | |

|

disprop

|

0.132 |

0.312 |

0.209 |

0.211 |

0.258 |

0.261 |

0.249 |

0.239 |

0.270 |

|

| Leg16 |

R seats | 7 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| R seat share | 0.538 | 0.385 | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.769 | 0.769 | |

|

disprop

|

0.055 |

−0.072 |

0.209 |

0.211 |

0.258 |

0.261 |

0.249 |

0.239 |

0.270 |

|

| Judges |

R seats | 4 | 4 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 8 |

| R seat share | 0.308 | 0.308 | 0.692 | 0.692 | 0.615 | 0.692 | 0.615 | 0.692 | 0.615 | |

|

disprop

|

−0.175 |

−0.149 |

0.132 |

0.134 |

0.105 |

0.184 |

0.096 |

0.162 |

0.116 |

|

| 538Pro | R seats | 5 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| R seat share | 0.385 | 0.462 | 0.692 | 0.538 | 0.538 | 0.538 | 0.538 | 0.538 | 0.538 | |

| disprop | −0.098 | 0.005 | 0.132 | −0.020 | 0.028 | 0.030 | 0.019 | 0.008 | 0.039 |

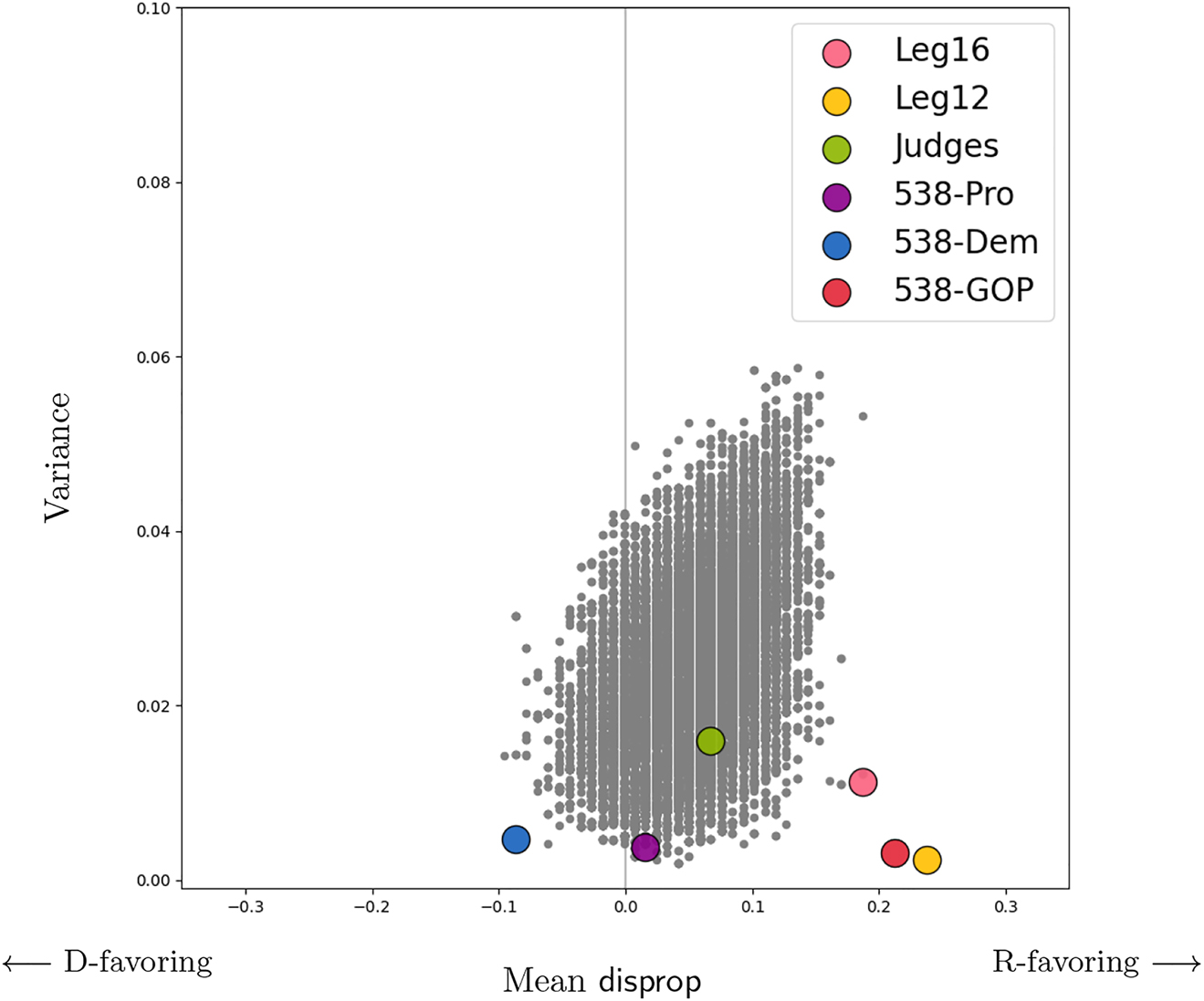

Statistics on disproportionality from North Carolina, with a party-neutral ensemble of 100,000 alternative plans plotted in gray. Handmade plans are marked with colored dots. Note that both legislative plans have high disproportionality, while the judges’ plan is much closer to a typical map in the ensemble. The 538 proportional plan succeeds at being very proportional with low variance, even though it was made using a different vote index. (This figure is repeated in Figure 5 below, alongside corresponding plots for the five other states studied here.)

Definition 2.

(Near proportionality). Given a threshold t > 0, a plan-election pair

This definition will help us study the FTV Test, which employed a threshold for Congressional plans of whichever is greater, one seat or 7%. That is, the language of the bill specified t = max (0.07, 1/k), where k is the number of seats. A proposed districting plan would be flagged as “materially favoring” a political party if its disproportionality exceeds

In this paper we focus on assessing the soundness of the FTV Test, granting its choice of elections

3 Validating Proportionality on Past Elections

Two questions are immediately posed by this discussion: first, how easy is it to design a near-proportional plan, even with perfect knowledge of the set of elections to be used in the test? And second, is past proportionality likely to predict future proportionality?

3.1 How Attainable is Near-Proportionality?

Figure 2 shows 100,000 population-balanced plans in each of six states, broken down by their success rate for near-proportionality in the four indicated elections.

Breakdown of 100,000 districting plans on each of NC, PA, WI, MA, MD, and TX, scored by near-proportionality using the most recent two presidential and Senate races with t = max (0.07, 1/k), as in the FTV test. Each slice of the pie shows how many plans had a near proportionality score of X/4, with X ranging from 0 (red) to 4 (green), counter-clockwise around the circle. For each state, the blue and green sectors show the share of plans that would pass the test with three or four successes, respectively. More than a quarter of neutrally-drawn plans pass the test in North Carolina, Maryland, Texas, and Wisconsin; in Maryland, it’s well over half. Thousands pass in Pennsylvania, while none at all do so in Massachusetts.

In the states from our dataset, we can see appreciable differences in whether the central tendencies of PSMD support the selection of plans with near-proportional historical outcomes. It is fairly common (25–30% frequency) for our process to generate a near-proportional plan by chance in North Carolina and Texas, while enforcing only contiguity, population balance, and a preference for compactness. In Maryland and Wisconsin, it is even more frequent, occurring over 40% of the time in our sample. The Pennsylvania sample gives over 13,000 examples of compliant plans, i.e. more than one in eight plans that were generated passes the test. (Recall that only a single compliant plan is ultimately needed, with no badge of typicality required in the test.) Finally, in Massachusetts, a proportional plan simply never occurred in our sample.[13]

Accordingly, ensemble evidence could clearly be used to protect an FTV-failing plan in Massachusetts from invalidation. Pennsylvania might attempt to rebut the presumption of a gerrymander, arguing that proportionality is difficult to secure. But on this reading of the bill’s intent, that attempt would fail and the other four states would have still more difficulty defending failing plans.

3.2 How Predictive is past Proportionality?

Given a plan that is shown to materially favor one party with respect to recent electoral data under a proportionality standard, is that property likely to persist into the future? Conversely, given a plan that secures proportional outcomes with respect to several past elections, how confident can we be that it will continue to do so? An empirical investigation of this question, starting again with North Carolina, is shown in Figures 3 and 4.[14]

A simple visualization of the predictive power of near-proportionality. Here, the training score is the number of near-proportional elections at t = 0.07 from an earlier set of contests. The test score shows the number of near-proportional elections with the same threshold for a later set of elections. In North Carolina, the proportionality performance on the later elections improves steadily as the earlier performance is increased. However, Massachusetts is different, as usual. The 2012–2014 period includes some election geography that makes it possible to achieve proportionality, so some maps earn a good training score. However, the 2016 and 2018 elections revert to form for the state, affording no instances of near-proportionality.

Near-proportionality predictions, continued. All four of these states show an overall tendency for near-proportionality (t = 0.07) on earlier elections to secure improved proportionality on later elections. With a minor exception in Wisconsin, where plans with a training score of 0–1 slightly outperform those that score 2–3, higher training scores always secure higher average test scores.

In these plots, the top histogram shows the breakdown of the ensemble by training score, which is the number of near-proportional outcomes from the earlier elections. Below that are histograms showing the test scores (near-proportionality in later elections) for the subset of plans with each training score, in turn. (The language of “training” and “testing” is borrowed from machine learning, where one collection of data is used to fit a model and a second collection of data is used to test the success of the model at making a prediction or classification.)

For instance, the North Carolina ensemble has 36,711 plans with a training score of zero, shown in the red bar. Below that, the red histogram breaks those plans down by test score, showing that the most common test score is also zero, while the gray line marks their average test score at 0.59. There are 39 plans with a training score of 4, barely visible in the top histogram, and expanded in green below (average test score 3.72). Texas and Wisconsin had more training score values achieved in the ensemble than the other states, so the training scores are grouped in pairs.

The results are quite encouraging. In several states—North Carolina, Maryland, and Wisconsin—there is a pronounced trend for plans that are more often near-proportional in an earlier electoral window to stay so in a subsequent window. In Texas and Pennsylvania, there is not much variation in the test score, but the small differences incline the right way. Massachusetts, as usual, bucks the trend due to the uniform partisan geography in the later set of elections.

4 Finding Proportional Alternatives

In this section we present summary data showing that alternative plans can succeed from the point of view of average performance on the largest dataset available, as a complementary view to the serial performance considered above. We choose to average em scores rather than averaging the elections into a blended index. Election averaging, especially for a range of contests up and down the ballot, is fraught with issues of proper weighting given variable turnout, and can obscure consistent patterns that are important for understanding likely outcomes (see footnote 14 above).

When we do compute a mean disproportionality, the variance is also informative. If the state dataset includes elections that are variable in their party lean, then the mean and the variance of disprop combine to give a good view of a plan’s properties. Low-variance plans with disprop ≈ 0 across a diverse set of elections would be especially strong choices under a norm of proportionality. By contrast, the most egregious—and most successful—gerrymanders would have high-magnitude disprop and low variance.

In Figure 5, we present the data corresponding to North Carolina’s Figure 1 for other states under discussion. As in that figure, we include the Wasserman/538 Proportional, Democratic, and Republican plans. Notably, the 538 project used a different method to measure proportionality, using an election index based on averaging Presidential contests to designate a target seat split; this is then paired with Congressional voting history to gauge the lean of the seats.[15] Thus, if the 538 proportionally partisan (“538-Pro”) map succeeds in FTV Test terms, it is a good sign that the FTV standard is robust to different ways of aiming at proportionality.

The gray scatterplots show the mean and variance of disprop for each state’s ensemble of 100,000 plans. (The MA dataset looks smaller because many of the points coincide.) The colored dots show the corresponding data for plans made by people, including legislators, courts, and journalists. Besides legislative proposals and the 538 plans, these include a plan made by a bipartisan panel of retired judges in NC; a plan proposed by the Governor and a remedial plan ultimately adopted by the court in PA; and a limited modification of the legislative plan in TX that was drawn by a court (in the name of VRA compliance). Colored dots are vertically jittered for visibility. NC plot is repeated from Figure 1.

In Massachusetts, the enacted plan—which performs the same as 538-Dem—is typical of the ensemble. Maryland’s enacted plan is fairly D-favoring, with moderately low variance. By contrast, the benchmark plan from the previous cycle (though it would have become malapportioned in the intervening years) behaves similarly to the 538 Proportional map. In Pennsylvania, the 538 team used the same plan as both a Democratic and Proportional map. It is indeed fairly proportional, with disprop ≈ 0 and low variance. The 2011 enacted plan, the legislators’ proposed replacement plan from 2018, and the 538 Republican gerrymander are all strongly R-favoring, somewhat mitigated by moderate variance. The Texas 538 Proportional plan once again lives up to its name. The court’s VRA remedial plan displays a consistent Republican skew, with low variance, but the 538 Republican plan goes further. And Wisconsin follows the trend that a plan aimed at proportionality can succeed.

We can make a few other observations from the scatterplots. For instance, the Massachusetts scatterplot shows considerably higher variance than in the other states because it includes not only President and Senate races but also others such as Governor’s races, which can incline quite Republican in an otherwise Democratic-leaning state. The larger states (PA, TX) have more consistent statewide election shares, which contributes to lower variance in disproportionality.[16]

5 Conclusions

The 50 United States are often called “laboratories of democracy,” and they are constitutionally entitled to construct state-specific legal frameworks for the “times, places, and manner” of elections, within the bounds of federal law. The manner includes a choice of systems (such as plurality elections in single-member districts, or PSMD) and a choice of norms for redistricting. For Congress, 45 of 50 states conducted PSMD elections in 2022.[17] In this paper, we explore whether it might be compatible with PSMD for states to adopt proportionality as a goal for Congressional districting. We find evidence that the ease of securing a series of proportional outcomes varies by state, but that even party-blind redistricting can readily produce many examples in most states that we study—which includes all of the major legal hotspots from the previous Census cycle.

Our empirical work clarifies how to perform the simple “FTV Test” for extreme partisan gerrymanders that was set down in the draft legislation of the Freedom to Vote Act, and we confirm that the test is neither vacuous nor overly stringent. Applied with a proportionality target, the test requires that at least three out of four designated elections produce near-proportional outcomes; if not, then a reason for deviation must be provided to a court. We consider five states that were widely regarded as partisan gerrymanders and challenged in court, and one more (Massachusetts) that was not but that has a notable political geography. The results are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.[18]

Plans made by legislatures. The ✓ signs indicate whether the disproportionality is below threshold; if not, the ± signs tell us which side is favored by the skew. None of these legislative plans passes the FTV test overall by succeeding in at least three of the four designated elections.

| State | Control | FTV elections | P/F | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC 2012 | R | + | + | + | + | F |

| NC 2016 | R | + | + | + | + | F |

| MA | D | – | – | – | – | F |

| MD | D | – | – | – | – | F |

| PA 2011 | R | + | ✓ | + | + | F |

| PA 2018 | R | + | + | + | + | F |

| TX | R | + | + | + | + | F |

| WI | R | + | + | + | + | F |

Here, we consider alternative plans that are plausibly more proportional, though they were not necessarily made with that goal in mind (particularly the Judges’ plan in NC, the Governor’s plan in PA, and the VRA plan in TX). For the ensemble plans, we look at the 25th percentile and 10th percentile performance, as explained in the text. The last column is a note on whether this evidence might help the state rebut the presumption of a gerrymander. Massachusetts would have a very strong case for rebuttal. Pennsylvania might attempt a rebuttal of the presumption of gerrymandering, but the evidence clearly favors the finding that their plans are impermissible under this standard. We see no reasonable grounds to attempt rebuttal in the other states.

| State | Alternative | FTV elections | P/F | Rebut? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | Judges | + | + | + | + | F | No |

| 538-Pro | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P | ||

| Ensemble25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | + | P | ||

| Ensemble10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P | ||

| MA | 538-Pro | – | – | – | – | F | Strong |

| Ensemble25 | – | – | – | – | F | ||

| Ensemble10 | – | – | – | – | F | ||

| MD | 2002 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P | No |

| 538-Pro | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P | ||

| Ensemble25 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | P | ||

| Ensemble10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | P | ||

| PA | Remedial | ✓ | + | ✓ | ✓ | P | Weak |

| 538-Pro | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P | ||

| Gov (D) | + | ✓ | + | + | F | ||

| Ensemble25 | ✓ | ✓ | + | + | F | ||

| Ensemble10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | + | P | ||

| TX | VRA | ✓ | ✓ | + | + | F | No |

| 538-Pro | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P | ||

| Ensemble25 | ✓ | + | ✓ | ✓ | P | ||

| Ensemble10 | ✓ | + | ✓ | ✓ | P | ||

| WI | 538-Pro | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P | No |

| Ensemble25 | ✓ | ✓ | + | ✓ | P | ||

| Ensemble10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | P | ||

In Massachusetts, the legislature’s plan scores 0 out of 4 with all deviations in a Democratic direction, but in fact every one of our 100,000 blind plans scores 0 out of four in the same way, indicating that this disproportionality is explained (and likely forced) by political geography. This provides ample evidence to rebut the presumption of gerrymandering, and it fits with earlier research findings in (Duchin et al. 2019). The case of Massachusetts illustrates the utility of setting up the FTV test as a rebuttable presumption of gerrymandering, so as to avoid requiring what is potentially impossible. In the other five states, the 538 Proportional plan and at least 1/10 of a neutral districting ensemble pass the test. As noted above, the randomized algorithms employed here explore the central tendencies of the PSMD system, and it is common for a mapmaker with a goal to produce plans that surpass the extremes of a neutral ensemble. Together, the 538 and ensemble evidence should give a court ample grounds to deny an attempted rebuttal in these five states.

Proportionality is a straightforward and intuitive normative standard, and in most states studied here, it is achievable in a single-member/plurality district system without extreme partisan tuning—in every state but Massachusetts, a substantial share of maps from a partisan-blind process pass the test. Taken together, our findings provide ample evidence that the FTV Test for redistricting is sound when used with a proportionality target (and a safety valve of rebuttability), in that it is both manageable and reasonably comports with the “ground truth” determinations from courts that identified certain plans as impermissible partisan gerrymanders. This should provide encouraging empirical support for policymakers to reintroduce a similar test at the federal level, or to specify a proportionality target at the state level.

Though proportionality is not to be automatically expected from plurality in single-member districts, even absent a gerrymandering agenda, the findings here should raise our confidence that in many cases proportionality can nonetheless be pursued—and achieved.

Acknowledgments and Disclosures

The authors thank Eric McGhee for helpful exchanges about the efficiency gap standard and Max Fan and Chanel Richardson for invaluable data support. We also thank Sarah Cannon, Devin Caughey, Daryl DeFord, Kenny Easwaran, Sam Hirsch, Michael Li, Ariel Procaccia, Jamie Tucker-Foltz, and Dave Wasserman for very useful feedback on this paper. MD served as an expert in LWV vs. Pennsylvania in 2018; this role was one of analysis and evaluation, and MD did not design any plan presented below.

Appendix A: Ensemble Specs

This paper uses ensembles of 100,000 districting plans produced by the recombination (“ReCom”) Markov chain method described in (DeFord, Duchin, and Solomon 2021a) and implemented by the MGGG Redistricting Lab in Python (MGGG 2018). Chains were run with uniform spanning trees and cut-edge district selection. This approximately targets the spanning tree distribution on plans, which has the property that the ratio of the probabilistic weight given to two plans only depends on shape statistics (in this case, spanning-tree compactness, or the product of the number of spanning trees over the districts) and not on any other features of the particular geography and population distribution.

The ensembles used here were made without a priority on county or municipality intactness, and with each district allowed to deviate no more than 1% from ideal population. Contiguity was enforced at every step. Ensemble scripts, a variety of outputs and plots, and other replication materials may be found in the GitHub repository associated to this paper (MGGG 2018).

Appendix B: Text from the Freedom to Vote Act

Here is the text in full from §5003(c), the section dealing with partisan fairness, in S.2747 (Freedom to Vote Act).

(c) No Favoring Or Disfavoring Of Political Parties.—

(1) PROHIBITION.—A State may not use a redistricting plan to conduct an election that, when considered on a statewide basis, has been drawn with the intent or has the effect of materially favoring or disfavoring any political party.

(2) DETERMINATION OF EFFECT.—The determination of whether a redistricting plan has the effect of materially favoring or disfavoring a political party shall be based on an evaluation of the totality of circumstances which, at a minimum, shall involve consideration of each of the following factors:

(A) Computer modeling based on relevant statewide general elections for Federal office held over the 8 years preceding the adoption of the redistricting plan setting forth the probable electoral outcomes for the plan under a range of reasonably foreseeable conditions.

(B) An analysis of whether the redistricting plan is statistically likely to result in partisan advantage or disadvantage on a statewide basis, the degree of any such advantage or disadvantage, and whether such advantage or disadvantage is likely to be present under a range of reasonably foreseeable electoral conditions.

(C) A comparison of the modeled electoral outcomes for the redistricting plan to the modeled electoral outcomes for alternative plans that demonstrably comply with the requirements of paragraphs (1), (2), and (3) of subsection (b) in order to determine whether reasonable alternatives exist that would result in materially lower levels of partisan advantage or disadvantage on a statewide basis. For purposes of this subparagraph, alternative plans considered may include both actual plans proposed during the redistricting process and other plans prepared for purposes of comparison.

(D) Any other relevant information, including how broad support for the redistricting plan was among members of the entity responsible for developing and adopting the plan and whether the processes leading to the development and adoption of the plan were transparent and equally open to all members of the entity and to the public.

(3) REBUTTABLE PRESUMPTION.—

(A) TRIGGER.—In any civil action brought undersection 5006in which a party asserts a claim that a State has enacted a redistricting plan which is in violation of this subsection, a party may file a motion not later than 30 days after the enactment of the plan (or, in the case of a plan enacted before the effective date of this Act, not later than 30 days after the effective date of this Act) requesting that the court determine whether a presumption of such a violation exists. If such a motion is timely filed, the court shall hold a hearing not later than 15 days after the date the motion is filed to assess whether a presumption of such a violation exists.

(B) ASSESSMENT.—To conduct the assessment required under subparagraph (A), the court shall do the following:

(i) Determine the number of congressional districts under the plan that would have been carried by each political party’s candidates for the office of President and the office of Senator in the 2 most recent general elections for the office of President and the 2 most recent general elections for the office of Senator (other than special general elections) immediately preceding the enactment of the plan, except that if a State conducts a primary election for the office of Senator which is open to candidates of all political parties, the primary election shall be used instead of the general election and the number of districts carried by a party’s candidates for the office of Senator shall be determined on the basis of the combined vote share of all candidates in the election who are affiliated with such party.

(ii) Determine, for each of the 4 elections assessed under clause (i), whether the number of districts that would have been carried by any party’s candidate as determined under clause (i) results in partisan advantage or disadvantage in excess of 7 percent or one congressional district, whichever is greater, as determined by standard quantitative measures of partisan fairness that relate a party’s share of the statewide vote to that party’s share of seats.

(C) PRESUMPTION OF VIOLATION.—A plan is presumed to violate paragraph (1) if it exceeds the threshold described in clause (ii) of subparagraph (B) with respect to 2 or more of the 4 elections assessed under such subparagraph.

(D) STAY OF USE OF PLAN.—Notwithstanding any other provision of this title, in any action under this paragraph, the following rules shall apply:

(i) Upon filing of a motion under subparagraph (A), a State’s use of the plan which is the subject of the motion shall be automatically stayed pending resolution of such motion.

(ii) If after considering the motion, the court rules that the plan is presumed under subparagraph (C) to violate paragraph (1), a State may not use such plan until and unless the court which is carrying out the determination of the effect of the plan under paragraph (2) determines that, notwithstanding the presumptive violation, the plan does not violate paragraph (1).

(E) NO EFFECT ON OTHER ASSESSMENTS.—The absence of a presumption of a violation with respect to a redistricting plan as determined under this paragraph shall not affect the determination of the effect of the plan under paragraph (2).

(4) DETERMINATION OF INTENT.—A court may rely on all available evidence when determining whether a redistricting plan was drawn with the intent to materially favor or disfavor a political party, including evidence of the partisan effects of a plan, the degree of support the plan received from members of the entity responsible for developing and adopting the plan, and whether the processes leading to development and adoption of the plan were transparent and equally open to all members of the entity and to the public.

(5) NO VIOLATION BASED ON CERTAIN CRITERIA.—No redistricting plan shall be found to be in violation of paragraph (1) because of the proper application of the criteria set forth in paragraphs (1), (2), or (3) of subsection (b), unless one or more alternative plans could have complied with such paragraphs without having the effect of materially favoring or disfavoring a political party.

Appendix C: FTV Test with Other Standards

How easy is it to pass the FTV test with different partisan fairness metrics setting the target? We compare the shares of a 100,000-map ensemble that are close to ideal with respect to proportionality (repeated from Figure 2 above), efficiency gap, and the ensemble mean, respectively, recalling that the green and bluesectors pass the test. An EG target is more commonly hit than a proportionality target in NC, MD, and especially TX, while there is no difference in MA and WI, and near-proportionality is slightly more common in PA. (In PA, but not in WI, one of the four test elections has far enough from even vote share that the two standards diverge.) Finally, the large green sectors in the bottom set of charts reflect the expected finding that a major share of an ensemble falls close to the ensemble mean.

References

Benadè, G., A. Procaccia, and J. T. Foltz. You Can Have Your Cake and Redistrict it Too. Preprint. Also available at https://www.gerdusbenade.com/files/21_gt.pdf.Suche in Google Scholar

Bycoffe, A., E. Koeze, D. Wasserman, and J. Wolfe. The Atlas of Redistricting. https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/redistricting-maps/ (accessed January 25, 2018).Suche in Google Scholar

Campisi, M., T. Ratliff, S. Somersille, and E. Veomett. “Geography and Election Outcome Metric: An Introduction.” Election Law Journal 21 (3): 2022–219.10.1089/elj.2021.0054Suche in Google Scholar

Cannon, S., A. Goldbloom-Helzner, V. Gupta, J. N. Matthews, and B. Suwal. 2022. “Voting Rights, Markov Chains, and Optimization by Short Bursts.” Methodology and Computing in Applied Probability. to appear.10.1007/s11009-023-09994-1Suche in Google Scholar

Cover, B. P. 2018. “Quantifying Partisan Gerrymandering: An Evaluation of the Efficiency Gap Proposal.” Stanford Law Review 70: 1131.Suche in Google Scholar

DeFord, D., N. Dhamankar, M. Duchin, V. Gupta, M. McPike, G. Schoenbach, and K.-W. Sim. 2022. “Implementing Partisan Symmetry: Problems and Paradoxes.” Political Analysis. to appear, https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2021.49.Suche in Google Scholar

DeFord, D., M. Duchin, and J. Solomon. 2021. “Recombination: A Family of Markov Chains for Redistricting.” Harvard Data Science Review 3 (1), https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.eb30390f.Suche in Google Scholar

DeFord, D., M. Duchin, and J. Solomon. 2020. “A Computational Approach to Measuring Vote Elasticity and Competitiveness.” Statistics and Public Policy 7 (1): 69–86, https://doi.org/10.1080/2330443x.2020.1777915.Suche in Google Scholar

DeFord, D., N. Eubank, and J. Rodden. 2021. “Partisan Dislocation: A Precinct-Level Measure of Representation and Gerrymandering.” Political Analysis 30 (3): 403–25, https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2021.13.Suche in Google Scholar

Duchin, M., and M. Bernstein. 2017. “A Formula Goes to Court: Partisan Gerrymandering and the Efficiency Gap.” Notices of the American Mathematical Society 64 (9): 1020–4, https://doi.org/10.1090/noti1573.Suche in Google Scholar

Duchin, M., T. Gladkova, E. Henninger-Voss, B. Klingensmith, H. Newman, and H. Wheelen. 2019. “Locating the Representational Baseline: Republicans in Massachusetts.” Election Law Journal 18 (4): 388–401, https://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2018.0537.Suche in Google Scholar

Eguia, Jon X. 2022. “A Measure of Partisan Advantage in Redistricting.” Election Law Journal 21 (1): 84–103.10.1089/elj.2020.0691Suche in Google Scholar

Katz, J. N., G. King, and E. Rosenblatt. 2020. “Theoretical Foundations and Empirical Evaluations of Partisan Fairness in District-Based Democracies.” American Political Science Review 114 (1): 164–78, https://doi.org/10.1017/s000305541900056x.Suche in Google Scholar

Landau, Z., and F. Su. 2014. “Fair Division and Redistricting.” In The Mathematics of Decisions, Elections, and Games, 17–36. Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society.10.1090/conm/624/12472Suche in Google Scholar

MGGG Redistricting Lab. GerryChain Python Package. GitHub Repository. Also available at https://github.com/mggg/gerrychain.Suche in Google Scholar

MGGG Redistricting Lab. Paper Replication Materials. Also available at GitHub Repository. https://github.com/gabeschoenbach/Proportionality-Paper.Suche in Google Scholar

McGhee, E. 2017. “Measuring Efficiency in Redistricting.” Election Law Journal 16 (4), https://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2017.0453.Suche in Google Scholar

Rodden, J., and T. Weighill. 2022. “Political Geography and Representation: A Case Study of Districting in Pennsylvania.” In Chapter 5 in Political Geometry, edited by M. Duchin, and O. Walch. Birkhauser.10.1007/978-3-319-69161-9_5Suche in Google Scholar

S.2747 – Freedom to Vote Act. Also available at https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/2747/text.Suche in Google Scholar

Stephanopoulos, N., and E. McGhee. 2015. “Partisan Gerrymandering and the Efficiency Gap.” University of Chicago Law Review 82: 831–900.Suche in Google Scholar

Veomett, E. 2018. “Efficiency Gap, Voter Turnout, and the Efficiency Principle.” Election Law Journal 17 (4): 249–63, https://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2018.0488.Suche in Google Scholar

Warrington, G. S. 2018. “Quantifying Gerrymandering Using the Vote Distribution.” Election Law Journal 17 (1): 39–57, https://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2017.0447.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.