Abstract

This article examines the applicability of three theoretical models – cultural appropriation, entanglement, and creolization – for understanding Jewish religious architecture in medieval Cologne in relation to contemporary Christian architecture in the same city. Focusing on the synagogue and mikveh constructed from the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries, it argues that these Jewish structures reveal underlying similarities despite being visually distinct from concurrent Christian buildings. Looking at shared technologies, resources, infrastructures, attitudes to ritual, and design aspirations confirms the underlying overlaps between these distinct architectural cultures. By favoring creolization as a model, the article illuminates how both rivalry and cooperation, adoption, and rejection underpinned by profound power imbalances influenced Cologne’s Jewish architecture in the Middle Ages.

Introduction: Different Models for Jewish-Christian Relations

The question of Jewish-Christian relations in Latin Europe in the Middle Ages has been discussed intensively by scholars with different conclusions. In the past, Jews were perceived as separate and isolated, maintaining an insular cultural life alongside Christian majorities in various regions of Europe [*][1]. Today the idea that social groups could be fully separated by the boundaries of their quarters, defined cultures or everyday practices, is no longer accepted. Scholarship, therefore, has suggested different types of interconnection and different phrases to define it [2].

In this paper I want to examine the relevance of different terms for describing the relationship between Jewish and Christian architectural culture in medieval Cologne ( North-Rhine Westphalia ). While such terms such as integration, cross-cultural exchange, acculturation, and multi-culturalism in material culture may be appropriate for describing the relationships between Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Mediterranean Islands or the Iberian Peninsula, though recently challenged by John Aspinwall and Theresa Jäckh [3], they do not capture the intricacies of Jewish-Christian relationships in Ashkenaz, a term found in medieval Hebrew texts for German-speaking lands [4]. Here, animosity was always intertwined with cultural immersion. Therefore, while isolation has been rejected as a model, there is likewise a problem with theoretical terms that fully blur cultural boundaries when tension between Jews and Christians is explicit in both sources and events [5]. Scholars have therefore suggested other terms that include a sense of difference between Jews and Christians on the one hand and, at the same time, acknowledge the porous, sometimes hard-to-define cultural boundaries.

Ivan Marcus advocated for ‘inward acculturation’ to describe Jewish selective adoption and adaptation of certain common practices from Christian society [6], internalized while maintaining differentiation and re-interpretation. Marcus held that Jews acculturated those aspects of Christian behavior that could be interpreted as serving an internal Jewish purpose, or used a common practice from Christian society in inverted or parodic ways. Elisheva Baumgarten suggested using appropriation while omitting the word culture in order to distance the term from the overtones of violence and inappropriate adoption and because ‘culture’ is not a stable entity with a fixed set of beliefs, values, and institutions [7]. For Baumgarten, ‘appropriation’ generated not just similarity but also difference, where groups in close contact invariably exchanged practices and beliefs while constantly recalibrating their identities vis-à-vis each other [8]. Acculturation, inward-acculturation or appropriation successfully replaced the no-longer popular term ‘influence’ which assumes a one-directional passage of cultural elements from one group to the other, one simply exerting influence and another simply taking it [9]. These terms, while spotlighting the complexity of adoption patterns, still remain one-sided: one society pliably acculturating certain norms, beliefs or isolated behaviors from another and translating them into their own needs or frameworks.

Entanglement

Georg Christ and colleagues used the term ‘Verflechtung’, entanglement or inter-weaving, to challenge the idea of a single direction and express the inextricable multi-directionality of cultural entwinement [10]. The English equivalent, ‘entanglement’, was used by Elisheva Baumgarten, Ruth Mazo Karras and Katelyn Mesler for Jewish-Christian relations in the Middle Ages, in order to reflect the idea that contact is two- or multi-directional and changes over time [11]. ‘Entanglement’ assumes that Jews and Christians drew to such a great extent from the same cultural pool that their two cultures, as they expressed themselves in western Europe in the Middle Ages, cannot be un-entangled and analytically set apart, yet – at the same time – that there was not full overlap, nor any one-directional influence. Baumgarten, Karras and Mesler used the image of an entangled vine to visualize the term, which reflects the idea of a shared root with branches intersecting, parting, turning, only to meet again and then separate once more [12].

The term entanglement is useful for reflecting division and co-dependence, accounting for simultaneous similarities and differences. The botanic metaphor of an entangled vine gives the sense of vibrant connections that grow and evolve with the passage of time. However, while the term is highly useful for daily practices, ideas or beliefs it is not fitting for architectural patronage. This is because the term implies equal weight in the process to all entangled groups. It therefore does not reflect disparity of power, differences in size or separate economic structures which all affect the ability to design and construct large-scale public buildings, the topic at hand. These differences in power and size, in the case of Jewish-Christian relations in the Latin west, were vast: small Jewish communities within large Christian cities; political control of Christians over Jews and monopoly of law and taxation; power imbalance between the pan-European network of the church and its hierarchy and the ‘soft’ and not institutionalized connections between Jewish religious leadership; economic and professional limitation placed on Jews that limited their access to wealth and social integration etc.

With architectural patronage demanding great funds and know-how, rapid technological changes that passed with groups of Christian workmen and access to materials in a changing industrial world, we cannot see Jewish architecture as an equal contributor to the developments of architectural culture. Quite the contrary, the Jews were dependent upon Christian architectural developments to realize their own projects. Yet Jewish communities created their own unique and creative architecture during the High Middle Ages, both participating in and differentiating themselves from the processes of design that were around them.

Appropriation

Was this a form of appropriation? Configuration of power is essential to analyzing overlaps or adoption in material culture and these are inherent to the term [13]. Where entanglement is too neutral, we might consider ‘cultural appropriation’ helpful because the term includes disparity of power and possibilities between majority and minority communities. However, the term was coined to express adoption, often inappropriate, of elements from a less powerful group by a stronger, bigger or otherwise superstrate society. This is the opposite direction to Jewish internalization of changing Christian architectural norms. The association of the term with misappropriation, privilege, and exploitation is hard to match historically for describing the process of Jews adopting Christian attitudes to public space, because of the inherent disadvantages they had in access to human and material infrastructure in comparison with Christian architectural commissions [14].

Appropriation, from the Latin verb appropriare, ‘to make one’s own’, doesn’t usually apply to minority groups making something their own [15]. For Kathleen Ashley and Véronique Plesch it includes a struggle, with an inherent motivation of ‘gaining power over’ [16]. Aspinwall and Jäckh define cultural appropriation as including an inherent violent dynamic, with the adoption of culture or cultural elements from a disadvantaged group [17]. These power-dynamics inherent in the term put into question the relevance of ‘cultural appropriation’ for cases where Jews adopted Christian architectural norms and building practices – the topic of this article. Jews formed the disadvantaged side of the equation in medieval Europe in many senses and therefore it is hard to posit an unwarranted, violent, cynical or advantageous taking possession of something that has its origins in Christian architectural culture.

The imbalance of power in favor of Christians invites a different term to describe Jews taking possession of changing architectural culture and adopting aspects of it for their own use. Unlike some definitions of cultural appropriation elements adopted by Jews from Christian architecture were not meant to be ridiculed even if they were differently interpreted or used in intentionally different ways. No matter how strong the Jewish-Christian theological polemics, the adoption of architectural elements evidences interest in the developments in religious architecture at the time, despite their Christian source. At the same time Jews made sure to visually differentiate the architectural whole: they isolated single elements and attitudes from Christian architecture, reorganized them and used them for completely different functions. They designed the adopted elements into a reorganized fully Jewish whole, comprised of newly-developed Christian architectural parts. The term ‘cultural re-appropriation’ has been suggested for the reaction by the minority group to assimilate and gain access to the majority group, to express resistance, or to get something back [18]. However, for my discussion of architectural culture the assumption of a tug-of-war of easily divisible cultural elements cannot accurately describe the dynamic in which architectural elements were designed with practical considerations beyond any cultural divide. A term that may better capture this dynamic is ‘creolization,’ which Bernard Gowers has recently applied to describe majority-minority interactions in the medieval Latin West.

Creolization

‘Creolization’, according to Gowers, can describe the adoption of elements from majority society by minority society by using the elements out of place, in a different way or even inappropriately or intentionally stripping them of their context and meaning [19]. Like cultural appropriation the term ‘creolization’ includes the idea that similarity on the surface does not always mean deep-running similitude. Or as Caroline Bynum explained in a different context: sometimes things that look alike are not necessarily very much alike and visual language can be reinterpreted when used [20].

Creolization, originally a linguistic term, was coined to describe developments in modern Caribbean and Atlantic languages, adapted and reorganized to form a new language based on some of the same vocabulary and syntax but markedly differentiated. Due to the formation of Creole languages in the context of slavery in the Caribbean, the term includes a sense of one of the cultures being geographically local ( ‘core’ culture ) and the other being transported, late arrivals or out of place, a useful prism through which to think of Jews in medieval Latin Europe. I suggest to think of the term as a mirror image of cultural appropriation, namely minority culture adopting elements from majority culture while rejecting, even ridiculing, that culture’s system of norms and beliefs at the same time.

Gowers has argued for using creolization not merely as a linguistic phenomenon relevant for the Atlantic but as a means for understanding social and cultural processes that occur in the meeting between superstrate ( majority ) and substrate ( minority ) societies. Creolization ( whether as a language or a process ) acknowledges disparity of power, as opposed to inner-acculturation or entanglement. It focuses on the other side of the equation from appropriation: cultural appropriation involves isolated and/or inappropriate use of elements of minority cultures by members of the cultural majority. The process of creolization is the opposite – selective adoption of elements from a majority ( or superstrate ) culture by a minority ( substrate ). Adoption does not mean a fuzzing of boundaries but rather a self-conscious cultivation of distinctiveness, dissent, and disagreement, with adoption of superstrate practices, with adaptation or a differentiating interpretation.

In the case of Jews constructing monumental works of public architecture one of the defining characteristics of creol is relevant: that the ‘core’ or ‘superstrate’ societies possessed significantly greater opportunities for the accumulation of capital, urbanization, exchange, division of labor, literacy, military capacity, and so on. Therefore, when examining Jewish architecture, we cannot expect any fully-fledged copies of Christian architectural works, that would simply not be within their reach and would not serve the purpose of Jewish identification. We can, however, see in certain surviving buildings what Caroline Bynum has called “dissimilar similitudes” [21]. This is what I want to suggest using the case study of Cologne along the Rhine, that Jewish and Christian public buildings that don’t look very much alike display deep-rooted similarities at their base.

Jewish Architecture in Medieval Cologne: Isolation, Entanglement, Cultural Appropriation or Creolization?

Any theoretical model is best applied to a specific example to test its relevance and accuracy. In order to do that this article focuses on the Jewish architecture of one city, Cologne, in the German federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia. More specifically, I look at elements within the Cologne medieval synagogue and at the architecture of the Cologne mikveh ( Jewish ritual bath ) and suggest they can only be understood in light of the Christian architectural culture in Cologne in the eleventh and the twelfth centuries. I apply the term creolization to these buildings to express a parallel adoption of Christian architectural norms and an aware and intentional differentiation of Jewish religious buildings from church architecture. On the one hand the Jewish monuments will be shown to depend on Christian building activity, infrastructures and expertise. On the other hand, these were used to convey Jewish differentiated identity and celebrate aspects of Jewish ritual that were unique, most markedly Jewish purification rituals.

Cologne is situated in the Lower Rhine valley ( Niederrhein ). It is the largest city in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, and the fourth most populated city in modern Germany. Cologne was founded as a Roman colony, Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium, in c. 50 or 55 CE as a seat of the provincial and military administration [22]. The first record of Jews in the city is from Late Antiquity, they are mentioned in a constitution by Constantine from 321 found in the ‘Codex Theodosianus’ ( Cod. Theod. 16:8, 3–4 ) [23]. While some scholars see this as evidence of a continuous Jewish community in Cologne from Late Antiquity on, this remains a stand-alone textual witness to Jewish presence in Cologne until the eleventh century, from which point onwards they are well documented as a large community [24].

By the late eleventh century Cologne was one of the largest Jewish communities in Germany [25], along with Mainz, Speyer, Worms, Würzburg and Erfurt [26]. Like other Jewish communities in the Rhineland, the Jews of Cologne, too, suffered persecution at the end of the eleventh century when they were hard hit in attacks by Christian soldiers on their way to the first crusade in 1096 [27]. There is evidence of the community’s recovery already in the beginning of the twelfth century when they were, amongst other things, assigned their own gate ( Porta Judaeorum ) for the defense of the city [28]. According to the archaeological sources, the Jewish quarter of Cologne flourished in the twelfth and the thirteenth centuries [29]. The communal infrastructure was expanded, they built a strikingly monumental mikveh ( Jewish ritual bath ) and later a communal hall and a hospital [30]. The synagogue was adorned in the thirteenth century with a new Torah ark and a bimah, also of unprecedented monumentality – and a women’s synagogue was added [31].

The thirteenth century was also a time of institutional changes. In 1266 the Jews received a privilege from archbishop Engelbert II of Falkenburg ( 1261–1274 ), carved on a stone slab still situated in the Cathedral choir [32]. The privilege promised Jews protection and special tax arrangements and following its granting the situation of the Jews of the city improved and the community became a center of economic and intellectual activity [33]. However, while the privilege was intended to grant them protection, catastrophe hit again in the middle of the fourteenth century when, on the night of 23 to 24 of August 1349, the Jewish community of Cologne was brutally attacked, their quarter burned, and the community buildings destroyed [34]. A new community eventually arose for a short decade: receiving a privilege in 1414 but ultimately being expelled in 1424 [35].

While not officially limited to a closed area, documentary evidence shows that the majority of the Jews in medieval Cologne lived in the heart of the city between Hay Market ( Heumarkt ) and High Street ( Hohe Straße ) [36], most Jews living on two or three streets between Kleine Budengasse, Unter Goldschmied, Obenmarspforten, and Judengasse [37]. The area belonged to the Parish of St Laurence church ( Laurenzpfarre ) and a source from 1091 mentions the Jewish quarter by the name inter judeos [38]. The archive of the City of Cologne ( Historisches Archiv der Stadt Köln ), where these documents were found, collapsed in 2009, but the sources were published as the first volume of ‘Quellen zur Geschichte der Juden in Deutschland’ in 1888 and enable reconstruction of both the structure of the Jewish quarter and the history of its houses [39]. The Jewish community also purchased two plots of land upon which they built a community hall ( domus universitatis ) [40] and sources as early as the eleventh century evidence a Jewish cemetery, usually the mark of a significant and central community, protected by the archbishops of Cologne beginning in 1266 [41]. Rich archaeological evidence allows the reconstruction of several impressive public buildings, characterized by a well thought-out overall design, ambitious dimensions and artistic details which can only be understood within the context of the bigger architectural developments in Cologne, particularly the rebuilding of all the city’s churches, in the eleventh to thirteenth centuries.

Cologne’s Synagogue: Sculpted Animal Heads from Stone Reserved for the Cathedral

Walking around Cologne today one still sees echoes of the city’s medieval might, embodied in the twelve ‘Romanesque’ churches – today largely reconstructed after World War II damage and much altered already in the early modern period – and in the large Gothic Cathedral, today mostly Neo-Gothic with extensive parts constructed from the nineteenth-century onwards, that dominate the skyline [42]. In the shadow of these churches developed the ambitious and highly decorated communal center of the Jewish quarter right in the center of town. Cologne was an important cathedral city but also a city whose medieval Jewish community was wealthy and organized enough to build a splendid synagogue and a huge monumental mikveh ( ritual bath ) [43]. The lost buildings of the former Jewish quarter are reconstructable from their cellars and foundation levels are still extant despite extensive destruction in the 1349 attacks and the mikveh remains in a relatively good state of preservation [44]. Excavations of the lost Jewish quarter and its public monuments began in the 1950s under Otto Doppelfeld ( 1907–1979 ) after the remains were found accidentally during construction works around the city hall [45]. Doppelfeld’s excavation has been followed by campaigns led by Sven Schütte ( until 2013 ) [46] and currently an ongoing excavation led by Michael Wiehen [47].

The different excavations have shown at least four phases of the synagogue [48], built to the south of the central part of the Praetorium of the Roman governor [49], but the interpretation of the building phases of the synagogue is still debated. The earliest remains have been dated by Schütte and Gerechter to the tenth century but the more widely accepted date for the Cologne synagogue is the middle of the twelfth century [50]. Otto Doppelfeld argued for four building phases: phase I before 1000 to 1096 when the building was damaged in attacks on the Jewish community; phase II from 1100 to 1280 when rebuilding works were undertaken; phase III from 1280s to 1349 when the synagogue was burnt in attacks on the Jews; phase IV 1372–1426. After the expulsion of the community in 1426 the synagogue was converted into a chapel for the adjacent Christian town hall [51].

In addition to archaeological findings, written records attest to the existence of a synagogue in Cologne’s Jewish quarter as early as the second half of the eleventh century ( 1075 ) [52]. Decorations added to the window frames on the northern wall of the Cologne synagogue were lavish enough already in this early phase to be criticized by a rabbi from nearby Mainz [53]. Ephraim Shoham-Steiner has argued that the rabbi took issue with the images because they were three-dimensional, stone-cut decorative reliefs of lions and serpents added at the behest of a Cologne lay leader or leaders [54]. Shoham-Steiner presents a spectrum of local Christian examples of similar sculpture, for example a Romanesque stone window-frame relief on the northwestern sealed window of the Groß St Martin in Cologne [55]. According to a twelfth-century chronicle the synagogue was a place for regular assemblies for Jewish scholars and heads of communities from elsewhere in the Rhineland, evidenced in a chronicle by Rabbi Solomon bar Simson of Mainz written c. 1140 [56]. The chronicler mentions the arrival of members of other Jewish communities three times a year in Cologne for a commerce fair, the congregation of locals and guests for prayers in the local synagogue and speeches by a local Parnas being held in the synagogue with some pomp and ceremony [57]. The image that arises is of an extra-local center, known and visited, with unusual decoration that was known beyond Cologne.

The synagogue, damaged in attacks on the city’s Jews in 1096, was rebuilt at the onset of the twelfth century in a campaign already completed in 1115 [58]. The quick recovery and rebuilding after 1096 are quite astounding bearing in mind the violent circumstances of damage and the size and quality of the new synagogue. According to Simon Paulus, the synagogue was constructed using a mix of building materials – including trachyte, basalt, and greywacke ( a variety of sandstone known for its hardness, dark color, and poorly sorted angular grains of quartz ). The walls were approximately 90 cm thick, and the inner room measured 9.2 meters in width and 14.5 meters in length [59].

The synagogue and mikveh of Cologne were highly monumental [60]. In keeping with the local architectural culture in the twelfth century, the synagogue, like the churches of Cologne that were remodeled in waves throughout the eleventh and the twelfth centuries, was rebuilt consecutively: remodeled, as mentioned, in a campaign completed in 1115 and then remodeled again several times in later decades [61].

The reconstruction of the synagogue, the former dance-house, an annex perhaps used for women’s prayer, and a surviving mikveh, a Jewish ritual bath used for ablutions, shows a grand set of Jewish public monuments from the eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth centuries [62]. According to Katrin Kogman-Appel the time of the major renovation of Doppelfeld’s phase III at the end of the thirteenth century, 1270–c.1280, was one of real flowering for the Jewish community of Cologne [63]. There is evidence of sustained growth of the community throughout the twelfth and thirteenth centuries with the ‘Judenschreinsbuch’ from 1135 showing Jews owning 30 houses at the beginning of the period; 48 in 1170; 50 in 1235; 60 in 1300; 70 in 1325 and 73 in 1349 [64]. In terms of residents ( rather than houses ), by 1250 the community had grown to at least 500 members [65], and around 1340 there were already about 750 Jews living in the communal quarter [66]. Phases I and II show architectural ambition and this was sustained in the renovation of phase III ( 1270–1349 ) which seems to have been a particularly grand phase of the synagogue with a significantly expanded space and, it seems, the addition of a woman’s annex [67]. Each renovation entailed funds, time and expertise which the Jewish community was willing to dedicate.

The wide hall of the synagogue was devoid of columns or piers and in its center was a large bimah, dated by Doppelfeld between 1270–1280, destroyed in the synagogue fire in 1349. According to Tanja Potthoff and Michael Wiehen the bimah was an impressive Gothic-style two-story structure lavishly decorated with Gothic pointed arches, richly profiled columns, tracery and finely designed tendrils and foliage with sculptural figures of small animals: birds, dogs and monkeys ( figure 1 ) [68]. These are a product of their time and the tastes of the day and region. A few fragments also survived from a gilded Torah shrine. Apparently, the Cologne Cathedral workshop both constructed the bimah in the synagogue in the thirteenth century and supplied building materials for it [69]. Remaining tiles from the synagogue flooring were part of patterned floors that can be found in many Rhenish medieval churches including St Pantaleon in Cologne ( 1170–1180 ) [70].

Reconstruction of Cologne Synagogue’s Thirteenth-Century Bimah: Stadt Köln, Dezernat Kunst und Kultur, VII/3: Archäologische Zone/Jüdisches Museum, MiQua. LVR-Jüdisches Museum im Archäologischen Quartier Köln; Technische Universität Darmstadt, Fachgebiet Digitales Gestalten; Ausführende: Marc Grellert, Pia Heberer, Tina Schöbel, Shoran Soltani, Norwina Wölfel und Arbeitsteam ‚Synagoge‘ des Rekonstruktionsprojekts. Printed with Permission.

Thinking of the infrastructure necessary for the construction and artistic embellishments I will posit that it was not accidental that the maintained effort was undertaken in a city where art and architecture were evolving all around with few halts for a century and a half. I suggest, therefore, looking deeper into the intersecting Jewish-Christian architectural culture in medieval Cologne through the prism of the phrases we have discussed. To do that we can add the evidence of a building that included highly sophisticated construction techniques and structural solutions, the Cologne Jewish ritual bath ( mikveh ).

Cologne’s Mikveh: Designing for Experience Deep Underground

Near the synagogue remains partially intact a Jewish ritual bath, a mikveh, used for ritual purification according to rabbinic law, which seems to have been built late in the second half of the twelfth century [71]. When Otto Doppelfeld excavated the city council’s chapel and former medieval synagogue in 1956, he detected the monumental mikveh very close at its south-western corner and uncovered the whole structure [72]. Some adaptions and reconstructions were made to grant public access, for example addition of concrete stairwells to replace the medieval original steps. In 2007 the City of Cologne started new excavations in preparation for the construction of the future MiQua LVR-Jewish Museum in the Archaeological Quarter [73].

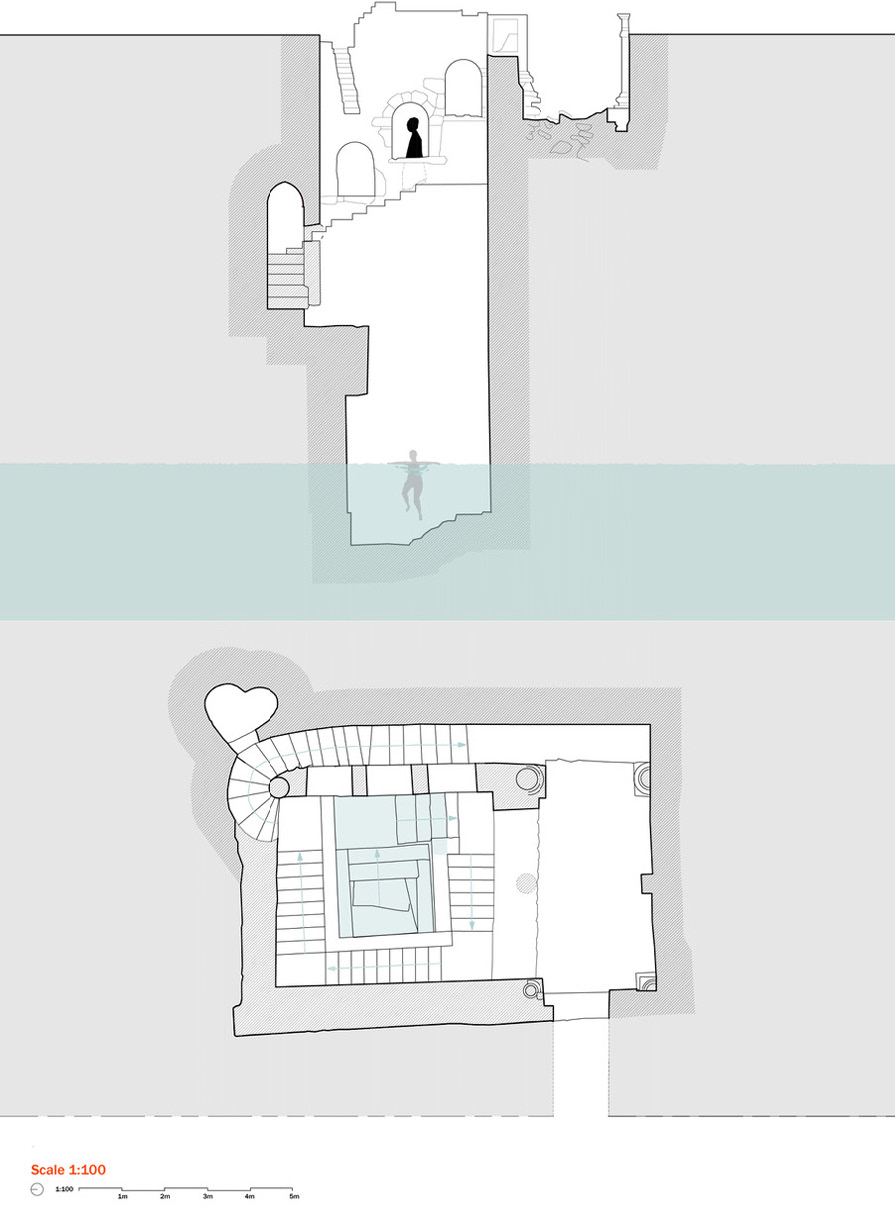

Remains of the mikveh show a deep building with stairwells dug into the ground and a wide shaft built over a naturally-replenishing pool of ground water. The main part of the building consists of an antechamber in the north ( 2.5x4.5 m ) that connects via a stairwell to a shaft sixteen meters deep ( 16x3.6x4 m ), with underground stairwells leading to a ground water pool in the south. The water pool is the main space of the building, meant for full-body immersion in the nude [74]. The mikveh consists of a decorated antechamber, perhaps a dressing-space for people preparing to ritually immerse, and a deep and wide shaft leading to a pool of naturally welling ground water sixteen meters below ground level ( figure 2 ) [75]. The building’s construction date is unknown, but it has been dated to before 1150 by the style of spolia columns within one of the interior spaces and to the mid twelfth-century on other stylistic grounds [76].

Plan and Section of Cologne’s Twelfth-Century Mikveh ( Current State ). Architectural Drawings: Moriya Erman with Neta Bodner.

The antechamber, shaft, and pool are connected by several flights of stairs: the first two dug into the earth outside the underground shaft-wall and the next two within the shaft around its perimeter. A fifth stairwell leads into the water pool itself, a self-replenishing natural underground spring ( figure 3 ) [77].

Above the water pool, at the summit of the towering shaft, was perhaps formerly a stone vault with an oculus – although the top of the building has been lost, but the west wall is broken by windows, so that if the original vault above the shaft possessed an opening, light could pass through the windows to the first stairwell outside the shaft and dimly light the stairs ( figure 4 ) [78]. If the shaft was originally open at the top, as I assume it was, it would have provided illumination directed from above the shaft overhanging the water into the stairwell wedged in between the shaft wall and the earthen masses outside the mikveh’s perimeters. The visual elements signal public monumental architecture on the one hand, and converge around the subjective, embodied perspective of a single naked user in the water on the other hand. The material framed by the whole is the water itself. The space spotlights the pool as the topic and the user interacts with the water in full nude form at the apex of the immersion ceremony. Walking downwards with flame illumination during the night, the walk towards the water has a mystical ambience. A niche in the wall may have held a lamp for nighttime use [79]. Looking upwards into the shaft from the waters during the day meant gazing up towards the light, creating a dramatic perspective and helping mark the pool as a climax.

Cologne Mikveh, View Looking Downwards. Photo: Author, with thanks to Michael Wiehen and Archäologische Zone/Jüdisches Museum, MiQua. LVR-Jüdisches Museum im Archäologischen Quartier Köln for access to the site.

Cologne Mikveh, View Looking Upwards. Photo: Author.

A building that evidences such planning and execution is an important source for understanding Jewish-Christian relations in medieval Cologne, and the ambitions of the Jewish community in the Middle Ages. Dug sixteen meters underground, Cologne’s mikveh is the deepest twelfth century example of a type of monumental mikvaot known only from the high Middle Ages and only found in today’s Germany and France. It is an impressive feat of engineering and construction work that necessarily entailed high costs and complicated logistical coordination [80]. Its construction would have been noisy and conspicuous, demanding tons of stone for building and wood for the scaffolding. Such a structure, even more so than the synagogue, would have been dependent on extant infrastructure for construction available in Cologne as a city that was undergoing perpetual architectural change over decades.

The revived quarries in Drachenfels up the Rhine from Cologne meant a steady influx of stones to the city, of different types fitting different construction needs and of different sizes, allowing large ashlar for steps and the immersion pool and smaller blocks for fill of higher shaft walls, stones fit for sculpture as seen in the synagogue’s bimah and stones of different colors to decorate the mikveh steps. The different cranes, pulleys, drills and scaffolds used for the churches, and seen in high-medieval paintings that record the continued church reconstruction that occurred in the city through the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, were a necessary prerequisite for imagining and realizing ambitious plans for the deep mikveh over ground water that still stands tall ( or rather, deep ) today.

Cologne’s Churches: A Fitting Background for Architectural Creativity and Ambition, Even by Minorities

The architectural culture in medieval Cologne and the anomalous extent of church construction and reconstruction help set the stage for understanding how the mikveh or such unusual elements as the synagogue’s bimah could have been imagined and commissioned. It was a culture of ambition, ability and creativity that facilitated both the construction ( or reconstruction ) of Cologne’s famous dozen Romanesque churches, with some of the most influential and innovative architecture from Late Antiquity to the High Middle Ages and, I would argue, gave rise to the realization of Jewish architectural ambition in the synagogue and mikveh buildings as well.

The synagogue and mikveh in Cologne are different from any works of Christian religious architecture built at the same time, yet can be compared with Christian Romanesque attitudes to building in Cologne as they changed in the eleventh to the twelfth centuries. Comparable strategies include ornamental details and design principles, such as shared structural solutions, use of ashlar stone blocks in evolving building techniques, architectural ornament, details of windows and arches, attitudes to subjective experience in religious space, emphasis on verticality, light from above and, indeed, in innovative and creative design of religious structures that push beyond extant norms of similar buildings before them ( figures 5–8 ).

The city of Cologne on the left bank of the Rhine was a seat of the provincial and military administration since founded as a Roman veterans’ settlement [81]. In the Middle Ages it was the largest city in the area of today’s Germany and an important episcopal center, the bishop’s seat in possession of a large and impressive Carolingian basilica ( later rebuilt ) and several Late Antique and Early Medieval churches within and immediately outside the city walls [82]. In the eleventh century the city of Cologne became one of the most important archbishoprics of the German empire [83]. In the twelfth century it became a buzzing center of creative Christian Romanesque architecture still evident today [84]. The surge of building, or rather rebuilding, included a dozen churches with Late Antique or Early Medieval origins that were redesigned in the Romanesque style and continued with the rebuilding of the Cathedral in the emergent Gothic style as well [85].

The eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth century changes to Cologne’s churches were the most prominent city-wide engagement with a wave of renewal that ran through the whole Rhine valley from one cathedral to the other with the support of the emperors [86]. The influence of Cologne’s architectural school was significant and throughout the Staufen period ( the whole twelfth century and the early years of the thirteenth ) it was the architecture of Cologne that pioneered the new building developments later dubbed the “Rhineland Romanesque” [87]. This Rhineland Romanesque style was associated with ideas of the greatness of the Holy Roman Empire, and imperial cathedrals became an architectural display of imperial power, an embodiment of the idea of the Roman Empire’s might, demonstrating the rank of their builders [88].

The pattern of architectural intervention can be understood by looking at some examples [89]. The Collegiate Church of St Gereon was rebuilt in the eleventh century but incorporated some remains of an earlier Early Christian church into the renewed medieval one [90]. St Pantaleon, founded in the late tenth century by Bruno I, Archbishop of Cologne, was rebuilt as a large, triple-aisle church during the twelfth century [91]. An earlier flat wooden roof in the west transepts of St Pantaleon was replaced by stone vaulting, a trademark of the Romanesque architectural revolution [92]. St Georg, founded by archbishop Anno in 1059 and completed after 1067, was extensively rebuilt in 1140 with stone cross vaults, and in a second renovation, towards the end of the twelfth century, the western apse was replaced by a square tower [93]. St Severin, the original building on the site dating to the late fourth or early fifth century, was remodeled many times in the Middle Ages [94]. St Maria im Kapitol, founded in the seventh century, was rebuilt in the mid eleventh century ( consecrated 1065 ), and rebuilt again in c. 1200 [95]. While today the church is essentially a reconstruction after it was severely damaged in World War II [96], there is enough evidence of the Romanesque form to know that the spatial solutions for the eastern end were unique and creative: the church was rebuilt with a unique tri-conch choir attached to a three-aisled nave, resulting in transept arms that followed the form of the apse, the unusual ambulatory formed by the side-aisles now continued all the way along the perimeter of the three conches creating an unorthodox plan and resulting in a continuous, uniform choir area with a pendentive dome at the center [97]. This innovative spatial solution was adopted in renovations of two other churches in Cologne – Sankt Aposteln ( nave 1020/1030, east part 1192 ) and Groß St Martin ( 1050–1172 ) – showing internal impregnation with new ideas and a vibrant spirit of architectural change [98].

Cologne Cathedral, Current State Begun c. 1247, Construction Continued in Several Sequential Phases until the End of the Nineteenth-Century, View Looking Upwards. Photo: Author.

Church of St. Georg, Cologne, Current State Begun in the Mid-12th Century with later Changes and Twentieth-Century Reconstruction following War Destruction, View towards East. Photo: Author.

Church of St Kunibert, Cologne, Current State Begun c. 1210 with later Changes and Twentieth-Century Reconstruction following War Destruction, View towards East. Photo: Author.

Church of St Maria im Kapitol, Cologne, Current State Begun c. 1040 with later Changes and Twentieth-Century Reconstruction following War Destruction, View towards South. Photo: Author.

Cologne continued to be an influential school of innovative Christian architecture throughout the whole twelfth century and the early years of the thirteenth [99]. Cologne Cathedral was consecrated in 870, but it was decided in the High Middle Ages that this much-altered Carolingian church would be replaced with a building that would express the importance of the archbishop, serve as a shrine to the relics of the three magi and symbolize the prominence of Cologne as a flourishing center of commerce [100]. Therefore, when the cathedral caught fire in 1248, it was left to burn down in order to be rebuilt in the new ‘French style’ [101].

The same Romanesque churches continued receiving changes as well. As the rebuilding dates of the churches show, Cologne was a vibrant city characterized by almost sequential building and renovation campaigns of religious centers, sometimes beginning decades after completion of a previous construction phase: Abbey Church of St Gereon ( begun in the eleventh century ); St Georg ( founded 1059, rebuilt 1140, renovated again at the end of the twelfth century ); St Maria im Kapitol ( first rebuilding consecrated in 1065, rebuilt again c. 1200 ); St Apostolen ( rebuilding campaigns in c. 1020 and 1192 ); Gross St Martin ( rebuilding campaign between 1050–1172 ); St Pantaleon ( rebuilding begun in the twelfth century ); cathedral ( sequential rebuilding begun 1248 with major phases till the nineteenth century ) [102]. The large number of churches redesigned evidences decades if not centuries of perpetual building in the city, churches often renovated several times to update their style, evidencing creativity, innovation and an appetite for new architectural ideas. According to Joseph Huffman “the building and remodeling of the churches of St. Gereon, St. Severin, St. Ursula (as it would become known), St. Kunibert, and the bishop’s cathedral church were costly, longterm investments. They functioned economically like major public works projects that kept many an artisan, merchant, and laborer gainfully employed.” [103]

In their rapidly changing city-scape the communities of Cologne were utilizing new technologies developing around them in real time. The period of 1050–1300 was one of Latin Europe’s most fertile eras of cultural creativity, it included a race of amazing breakthroughs in technology and science and was characterized by bursts of renewal, revision, re-enlivening and restructuring of novelties achieved in earlier eras [104]. In Cologne the use of innovative new methods was accelerated by the sheer mass of churches being rebuilt over decades and even centuries. The Jews, despite their marginal social status, took part. This can be seen in this early example of a deep shaft-type mikveh, perhaps a precedent for later examples, in the huge and ambitious bimah with ornate sculpture, written evidence of animal decoration at the synagogue and general dynamic of change and addition of public buildings or building parts in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Therefore, while the churches and the synagogue and mikveh do not look alike, there are noteworthy parallels in the processes of change. In some churches new spatial solutions developed in Cologne were quickly adopted and expanded upon in other church-redesigns, reflecting a vibrant school of architecture with creative thinkers and technical ability. The Jews of Cologne joined their Christian neighbors in taking part in and benefiting from these developments [105]. The extent to which they chose similar or differentiated architectural strategies can be key to understanding what Baumgarten has already noted regarding daily life: that seemingly overlapping practices could serve distinctive, even contending, identities and do not necessarily reveal cultural overlap [106].

Each of the complexes – monastic, parish, Jewish, and cathedral – had two distinct visual narratives. One was internal, what the community saw of the latest artistic trends adopted by their place of worship. One was external, what others could see of their complex. Here, of course, it was the church steeples and towers that dominated the skyline of Cologne to all directions, as they do today, and communicated their remodeling beyond the circle of users. Fifteenth-century paintings that show the residual architectural activity in their day show nicely what remodeling entailed: people, materials, visible scaffolding, dust. In eleventh-century Cologne, when the synagogue was first rebuilt, and to a greater extent in twelfth-century Cologne with the foundation of the mikveh, these would have been all around the Jewish quarter where these rebuilding projects were carried out in the shadow of the reconstruction of the churches. That the Jews reacted to the atmosphere of architectural change teaches us about their participation in the characteristics of the Christian city.

One of the main features of Romanesque Cathedrals in the Rhineland is the stress on verticality [107], also evidenced in the Cologne mikveh. While large cathedrals were substantiated expressions of power, pride, and status [108], the Jews of Cologne too managed to express fortitude through architectural patronage and waves of expansion and creative additions throughout the twelfth century. Cologne’s churches incorporated remains of earlier structures ( for example the cathedral and the church of St Gereon ), perhaps to stress their antiquity. The mikveh building, too, incorporated spolia columns, though we can likewise only speculate regarding symbolic meaning. Addition of towers, as at St Georg, is a characteristic of Romanesque in German-speaking lands and the mikveh shaft should be studied in this context despite being subterranean as the construction methods could have been based on tower-building techniques, as it was a time of development of spires and a race for heights [109].

Ashlar stone blocks were brought from some of the same quarries, rediscovered in the Middle Ages after falling out of use at the end of the Roman period: it has been shown that the bimah was made from stones usually allowed for use only within the cathedral itself and by the cathedral opera [110]. In both the churches, the synagogue, and the mikveh there is new use of towers and lanterns for natural lighting ( over ground in the churches but subterranean in the mikveh shaft ) to accentuate the experience of space [111]. Continuous, uniform space characterizes the renovations of the churches and the synagogue, though the churches use stone vaults while the synagogue, uncharacteristically for the development of the time, is devoid of columns or piers and thus had a timber roof. The single synagogue space with no division into aisles or interior supports is very different from the plans and elevations of the churches. Yet the campaigns of renovation overlap and the attitude to innovation, space, decoration, and stone-ornament can point to sharing the same spirit of engagement with the stone revolution and its possibilities for redefining religious spaces.

Partaking in a spirit of renewal, even when there was no structural need for it, is a mark of the time for churches but is surprising for substrate ( Jewish ) rather than superstrate ( Christian ) societies. Churches were rebuilt by rich and stable institutions. Synagogues belonged to marginalized and small communities, some of which were subject to devastating attacks at the end of the eleventh century and at different points between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. Therefore, while the synagogues and Jewish ritual baths could not compete with imperial commissions and rebuilding of cathedrals in influential dioceses, their ambitious redesign in the eleventh and then again in the twelfth century in the city of Cologne should be marked. It can show parallel ambitions despite the huge power imbalance between groups.

Similarly Different: Comparing Architecture that Doesn’t Look Alike

Assuming that things can look different but have inherent underlying similarity is an insight that was developed by Caroline Bynum in ‘Avoiding the Tyranny of Morphology; or, Why Compare?’ [112], expanded upon in ‘Interrogating Likeness’ and theorized in ‘Dissimilar Similitudes. Devotional Objects in Late Medieval Europe’ [113]. According to Bynum “the issue of comparison is more difficult than we usually admit. Looking alike may not be the best basis for a comparative study that must [ … ] consider both similarity and difference to be problematic if it is to illuminate either side of a comparison.” [114] Engaging with Bynum’s idea that things can look different but be similar ( and vice versa ) is a good way to refine the scope of cultural appropriation, where in most examples things look similar but are actually used and interpreted differently, and become aware of its sometimes fuzzable boundaries. Inherent similarity between Jewish and Christian religious architecture, in Cologne and elsewhere in Latin Europe, is only partially anchored in visual similitude. Rather, it stems from shared assumptions about what religious rituals should look like, how spatial design can support their performance, the different visual metaphors for God and symbolic use of materials such as stone, water and, to the extent we can call it a material, light [115]. Jews in Cologne reorganized the details developed as part of Christian Romanesque into a new syntax and message – building a new architectural language by adopting ‘words’ and even isolated ‘sentences’ from the evolving style of Rhineland Romanesque whose major home was Cologne. If this interpretation is accepted, then one can ask if they were forming a local creole. Or, to complicate the question, if they were simply using the ‘ingredients’ available for architectural solutions in medieval Cologne. Or, if we discard the critical aspect of the term ‘to appropriate’ and focus on the etymology of ‘to actively make something one’s own’ then we can think of the Jewish use of some architectural practices as cultural appropriation [116]. Here, as Nelson notes, there is an active and a passive side [117], the Jewish community brought into its synagogue elements derived from Christian tastes; most well-preserved is the evidence of the gothic tracery and sculpture of the bimah. Like Marcus’ ‘inward acculturation,’ here too there is no reason to assume that any Christian interpretation or association was maintained, rather the aesthetics were turned into something serving internal Jewish needs and, we can imagine, interpretations.

Complicating the Question, Challenging the Theoretical Models: Technology as a Shared Resource above the Cultural Divide

The Romanesque building revolution, in which I have argued the Jews of Cologne partook, was based on a set of technological changes that flew through Europe, changed the economy, opened up new trade and occupations, and led to a change in the way cities looked and functioned [118]. Different machines for quarrying, transporting, sculpting, and lifting stones were invented and knowledge spread fast with moving groups of masons and other building professionals. Stone quarrying became one of the biggest industries, by far the most important mining industry, and a major source of income and occupation [119]. The mason was one of the highly skilled workmen of the medieval industrial revolution [120]. Underground quarries comprised an intricate web of stone galleries and the quarrymen tunneled long parallel and transverse galleries, sometimes on three levels [121]. The tunneling skills needed for constructing and expanding the quarries could have contributed to the design and construction of the mikvaot in Latin Europe as well. Over ground, vast workshops were cut out of the rock to provide space for rough-hewing and to make way for carts pulled by oxen or horses and ingenious machines were used to load and unload stones [122].

According to Tanja Pothoff, quarries for Cologne’s churches were situated nearby at Drachenfels ( Siebengebirge ), where trachyte, latite and basalt have been mined since Roman times. The quarries were high up on the mountains and cutting and transporting them demanded knowledge and effort. Stone was so expensive that ashlar blocks from older structures were recycled for new buildings in the eleventh and twelfth centuries: it is reported that Louis the German had the walls of both Frankfurt and Regensburg torn down in order to build two churches; the marble and limestone to build Lyons Cathedral were transported in 1192 from Trajan’s Forum in nearby Fourvire; Gauzlin, the abbot of Fleury ( Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire ) obtained marble a partibus Romanie from the Nivernais after 1026 [123]. One of the achievements at Speyer in an eleventh-century rebuilding was the roofing of the entire nave with stone cross-vaults [124].

Like food or materials, technology, too, is inherently connected to a time and place, and therefore is a shared reality for majority and minority societies alike. The accelerated speed of renovation was a result of different social and historical factors: the end of attacks by invaders, a rise in demographic growth, improvements in industry of different kinds, the rise of cities, a change in the structure and character of feudal rule, movements for church reform, the rise of new organizations and orders and other developments sometimes known as the Twelfth-Century Renaissance [125]. The Romanesque style period represented an age of expansion and consolidation of Christian Europe. It was characterized by increasing urbanization and witnessed remarkable technical and intellectual innovations. This is the time in which ‘The Europe of Cathedrals’ took shape, with bishops’ churches coming to dominate the skyline of many towns and cities across the continent [126]. It was also a time in which Jews built unprecedented mikvaot and expanded and beautified their synagogues in cathedral cities in the Rhineland.

As has already been mentioned, the surge of church rebuilding in Cologne, in the shadow of which the synagogue was renovated and the mikveh built, was not an isolated phenomenon. From around the year 1000 to the middle of the eleventh century nearly all German Empire cathedrals underwent large-scale reconstructions, most of them in modern and monumental design, after decades and even centuries of little building activity [127]. The appetite for renovation seems to have been contagious and affected different denominations, orders and – I have argued here – Jews as well as Christians. Looking at how ‘contagious’ the appetite for renovation seems to have been, we can ask whether technological advancement brings with it new ambition in a way that evades cultural divides. Perhaps developing technologies, at any time, are not identified by communities as connected to a limited identity group, they don’t seem to belong to closed social circles. Are new technologies like local production of foodstuffs: regionally specific and therefore used as a base for the different ‘kitchens’ of separate groups that live side by side in the same place? When people of different beliefs use cellular phones, the internet or virtual reality headsets, are they drawing from a shared cultural pool, appropriating western culture ( even if the items are made in East Asia ), or doing something else altogether? In what way can technological changes be associated fully with one ‘culture’? Perhaps they are more like raw materials that can be molded into different forms that serve different cultural purposes?

Conclusions

Spiro Kostof has argued that public places were repositories of a common history, and expressions of a shared destiny, places for shared ritual behavior and uniting ritual action [128]. According to Micha Perry there has been a scholarly view that sees the medieval Jews as ‘people of the book’ escaping the hardship of life into the pages of the Talmud, preoccupied with every miniscule detail of its laws as a sort of escapism of the powerless into an imaginary reality in which they and over which they held power [129]. For Perry this dichotomy between ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’, medieval reality and Talmudic law does not hold when thinking about the Eruv, where the two worlds – old laws and contemporary reality – were forced to meet [130]. I would like to suggest that the same statement holds true for architecture – the religious and religious-legal considerations had to meet on the ground realities of materials, techniques, available workmen, legal permissions regarding building, financial considerations, and communal ones. They also met the less practical and material considerations of taste and stylistic ambitions, the realms in which questions of appropriation, creolization or just cultural immersion can overlap. What can be said about the definition of that common history and shared destiny if the synagogue and other public buildings were entangled with the stylistic preferences and technological advances of contemporary church architecture? Here the term creolization may again be useful.

However, eliding these terms altogether I have also maintained that as core society shifts with technological innovation, so does the minority or substrate society in its midst. While adopting new technologies, the substrate society does not necessarily see it as belonging in some way to majority society in which it has only recently prior been born. Technology can serve as an empty cultural slate in real time and only be perceived by us in hindsight as a marker of only one original side of the cultural divide. The High Middle Ages are a technological moment, with new building practices and abilities. These should be considered in the analysis of the bath and synagogue in Cologne and in consideration of the Jewish-Christian relations that are reflected in the architectural decisions.

Here creolization, which describes, for example, how Slave families used African cooking traditions with ingredients found in the Atlantic, could be helpful in spotlighting the porous boundaries between culture, technology, and availability of materials. It helps to think of what culture is and suggests that in cases where ( due to new technologies or norms ) both minority and majority culture change together, it may not be a case of appropriation but of something else. Therefore ‘creolization’ as applied by Bernard Gowers to the Middle Ages, can complement ‘cultural appropriation’, to help explain some relationships expressed in the architectural works. Finally, Gowers distinguishes between ‘pragmatic’ and ‘programmatic’ creolization; the first involves practical considerations ( for example taking over a word or a technique because it is useful and absent elsewhere ), the second, involves self-consciously pushing the boundaries between groups and forming a self-aware combination. For this discussion both could be argued for: if emphasis were placed on the role of technological opportunity in the development of Romanesque then pragmatic creolization could be argued for. If, rather, we understand the buildings as bearers of meaning and facilitators of experience, designed for penance-based body rituals intended for reaching spiritual goals, then perhaps we should consider Cologne’s mikveh in the context of programmatic creolization.

Entanglement, being a neutral term when it comes to asymmetric power dynamics, cannot fully account for adoption of Christian architectural norms and tastes in Jewish religious architecture, perhaps more so for the practical side of adoption of new Christian building technologies by Jews. Here the term ‘appropriation’ could be useful for cases in which Christian society chose to use Jewish symbols, objects or language in a way that is out of place, derogative or misinterpreted. Appropriation and creolization are two mirror-terms, the first looking from the point of view of majority and the second from the point of view of minority society.

Whichever term is considered to best describe the case study, it has been argued throughout the article that changes to architecture can reveal various social processes, changing values, shifting circumstances, reaction to events, and altered ideals. Religious buildings came to fill highly significant religious and social functions for the communities and cities in which they are situated. For Jews in medieval German-speaking lands these changes occurred partially as a result of shifts in Christian architectural norms and ambitions.

Public architecture, and over time especially religious public architecture, often came to be perceived as embodying something of the community that built and used it. Therefore, design decisions and patterns of use were never only practically driven or a technical act, but rather should be studied as meaningful decisions that reflect both values and self-perception. Contrary to expectation, design decisions often resulted from reasons entirely unrelated to safety, conservation, or other practical needs, but rather stemmed, in fact, from broader social and cultural developments such as political ambition, theological developments or military achievements [131]. They are a good source, therefore, for gauging both the abilities and the beliefs of societies, and in this case a good source for discussing Jewish-Christian relations on the boundaries between separation, influence, appropriation or entanglement.

© 2025 the author(s), published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Titelseiten

- Von Sisebut zu Sisenand

- Augustine vs Wodan

- Mobility, Trade and Control at the Frontier Zones of the Carolingian Empire ( 8th–9th Centuries AD ) *

- Ottonian Notions of imperium and the Byzantine Empire

- What Did Comitatus Mean in the Ottonian-Salian Kingdom?

- The ‘Traitor’ of Béziers

- Die feinen Unterschiede zwischen einem Einsiedler und einem Apostel

- Serielle Notation

- Premodern Forms of Cultural Appropriation

- When Can We Speak of Cultural Appropriation?

- Designing the Divine

- Instances of Cultural Appropriation in the Works of Paulus Alvarus and Eulogius of Córdoba

- Unstable Races?

- Appropriation, Creolization or Entanglement?

- “The Emir of the Catholics”

- Orts-, Personen- und Sachregister

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Titelseiten

- Von Sisebut zu Sisenand

- Augustine vs Wodan

- Mobility, Trade and Control at the Frontier Zones of the Carolingian Empire ( 8th–9th Centuries AD ) *

- Ottonian Notions of imperium and the Byzantine Empire

- What Did Comitatus Mean in the Ottonian-Salian Kingdom?

- The ‘Traitor’ of Béziers

- Die feinen Unterschiede zwischen einem Einsiedler und einem Apostel

- Serielle Notation

- Premodern Forms of Cultural Appropriation

- When Can We Speak of Cultural Appropriation?

- Designing the Divine

- Instances of Cultural Appropriation in the Works of Paulus Alvarus and Eulogius of Córdoba

- Unstable Races?

- Appropriation, Creolization or Entanglement?

- “The Emir of the Catholics”

- Orts-, Personen- und Sachregister