Abstract

Following the suspension of new US aid to Ukraine in early 2025, European countries faced mounting pressure to fill the resulting gap. This paper analyses the extent to which Europe has responded, drawing on data from the Kiel Institute’s Ukraine Support Tracker Release 23. The findings reveal that European donors have significantly increased their support, allocating a record €26.9 billion in the first trimester of 2025, helping to offset the absence of new US support. However, this surge is unevenly distributed between countries and partly reliant on exceptional financing sources, such as interest from frozen Russian assets. Structural constraints, including limited defense industrial capacity, raise further questions about the sustainability of this effort. While Europe’s initial response is encouraging, its durability remains uncertain in the absence of structural reforms and more balanced burden-sharing.

1 Introduction

Since the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, aid to Ukraine has emerged as a defining issue in international policy debates. Over the past three years, the United States has played a pivotal role, allocating a total of €114.6 billion – by far the largest contribution from any single donor. However, recent political developments have cast serious doubt on the continuity of US aid. The return of President Trump to the White House has led to a sharp turn in US policy on the war, most visibly through a public dispute between the American and Ukrainian presidents in the Oval Office, and the subsequent announcement of the suspension of US aid to Ukraine – an announcement that, while quickly reversed, signaled increasing volatility in Washington’s stance.

This shift has prompted a pressing question for Europe: can European countries fill the potential gap left by a US withdrawal? Our March 2025 study (Irto et al. 2025) offers a preliminary analysis of this question. Drawing on comprehensive data from the Kiel Institute Ukraine Support Tracker covering the period from 2022 to 2024, we calculated the level of effort required from European donors to fully compensate for a scenario in which the United States ceases allocating new aid to Ukraine. Our estimate suggests that European countries[1] would need to allocate approximately 0.21 percent of their combined GDP to close the gap left by the absence of US support.

As of mid-2025, this scenario has effectively materialized. The United States has not allocated any new aid to Ukraine since the inauguration of the Trump administration in January 2025. In light of this development, it is timely to assess: to what extent have European donors approached the 0.21 percent GDP benchmark? And, if that level has been reached, is it feasible for them to maintain this pace of support for the remainder of the year?

To address these questions, this paper is structured into three sections. First, it revisits the key findings of our March 2025 study to provide analytical context for what follows. Second, it draws on data from the Kiel Institute Ukraine Support Tracker Release 23 (Trebesch et al. 2024, 2025), which is the latest available version at the time of writing and covers aid announced through April 2025, to assess the extent to which European donors have progressed toward the 0.21 percent of GDP benchmark during the first four months of the year. Third, it examines the sustainability of this level of support, considering both structural constraints and enabling factors that are likely to shape European aid decisions over the remainder of 2025.

2 Ukraine Support Before 2025: The 0.21 Percent GDP Benchmark for Replacing US Contributions

With President Trump’s return to the White House in 2025, the continuity of US support for Ukraine can no longer be assumed. As a result, increased attention has turned to Europe’s capacity and willingness to assume a greater share of the burden. Against this backdrop, our March 2025 study estimated the level of support that would be required from European countries to fill this gap, drawing on aid allocations announced through the end of 2024 and recorded in the Kiel Institute Ukraine Support Tracker. Between the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion in early 2022 and the end of 2024, Ukraine received an annual average of €38 billion from the United States and €43.5 billion from Europe – together accounting for more than 90 percent of the yearly average aid allocated by all donor countries in the dataset.

If European countries were to fully offset the loss of US assistance while maintaining the overall level of support seen in previous years, they would need not only to sustain their own allocations, but to also compensate for the €38 billion per year previously allocated by the United States. This would require a combined annual allocation of approximately €82 billion, equivalent to 0.21 percent of Europe’s total GDP in 2023.

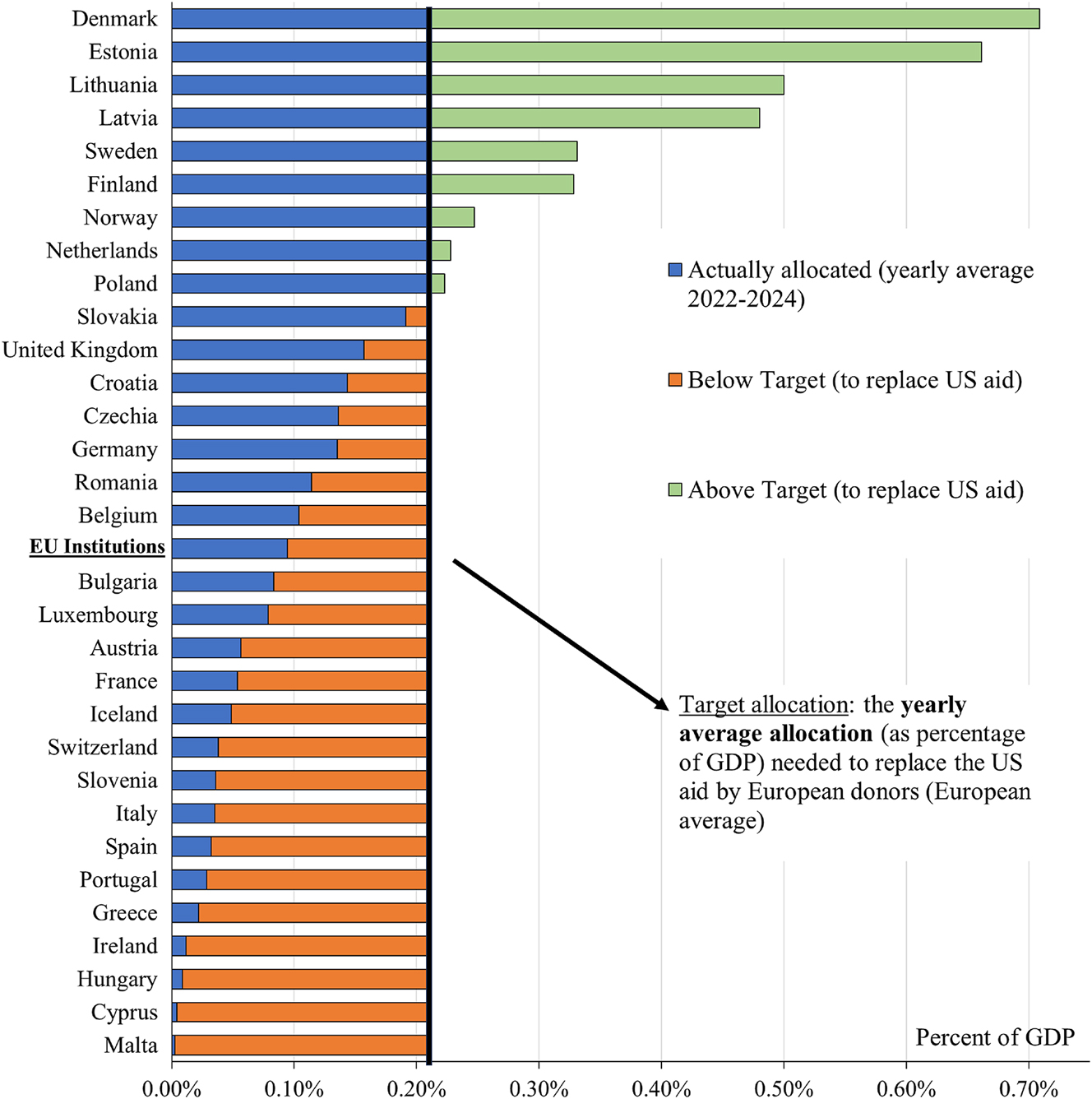

In order to identify which countries would need to increase their efforts to meet this benchmark, we assess the extent to which individual European donors[2] met or fell short of the 0.21 percent target, based on their average annual aid allocations between 2022 and 2024, as illustrated in Figure 1. According to this graph, a small group of countries – notably the Nordic and Baltic states, as well as Poland – had already allocated more than 0.21 percent of GDP on average during this period. By contrast, the majority of countries, particularly the larger European economies, allocated substantially less in bilateral aid: the United Kingdom and Germany mobilised, on average, 0.16 percent and 0.13 percent of GDP, respectively, while France allocated just 0.05 percent, Italy 0.04 percent, and Spain only 0.03 percent. Given the size of their economies, an increase in allocations from these countries would significantly enhance Europe’s ability to meet the 0.21 percent benchmark.

Distance from the 0.21 percent of GDP benchmark: Annual average aid allocation by donor, 2022–2024 (as a share of 2023 GDP). Source: Irto et al. (2025).

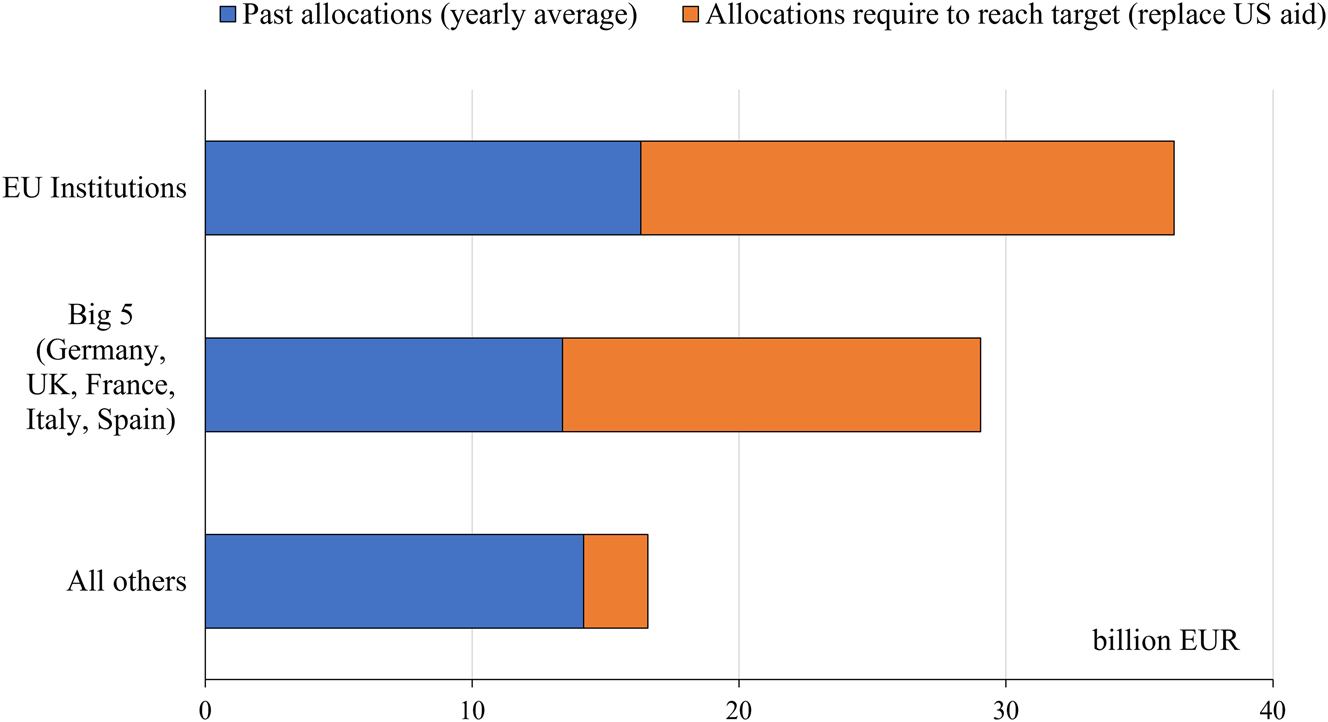

This disparity becomes even more evident in Figure 2, which visualizes the absolute shortfall from the 0.21 percent benchmark by grouping European donors into three categories: (i) the EU institutions, (ii) the five largest European economies (“Big 5”), and (iii) all other European donors tracked in the Kiel Institute Ukraine Support Tracker. Notably, more than 90 percent of the shortfall originates from the EU institutions and the Big 5. To contribute their proportional share in replacing US support, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom would need to more than double their bilateral aid allocations, bringing their combined annual allocations to nearly €30 billion. Likewise, the EU institutions would need to scale up their allocations substantially, increasing their annual aid to over €36 billion.

Distance from the 0.21 percent of GDP benchmark: Annual average aid allocation by donor group, 2022–2024 (in € billion). Source: Irto et al. (2025).

3 Ukraine Aid in the First Trimester of 2025

3.1 General Trend: European Surge Broadly Offset the Halt in New US Aid Allocations

The preceding analysis sets a clear benchmark for what would be required of European donors should US aid cease entirely. The critical question in 2025, then, is whether this scenario has in fact materialized – and, if so, to what extent Europe has responded in line with the 0.21 percent benchmark. Figure 3, which presents cumulative aid allocations by the United States and European countries since 2022, illustrates two key trends that have emerged in early 2025. First, this graph shows that the new US aid allocations are completely halted following the inauguration of the Trump administration. This clarifies that the scenario we previously anticipated in our March 2025 study has now actually materialized.

Cumulative aid allocations over time: Europe versus United States, 2022–April 2025 (in € billion). Source: Ukraine support tracker release 23 (Trebesch et al. 2024, 2025).

Second, European countries significantly increased their support during this period. Between January and April 2025, they allocated a total of €26.9 billion in aid to Ukraine. This marks the highest amount ever allocated by Europe in a single trimester and represents a more than 40 percent increase compared to the same period in 2023 – the trimester that had previously recorded the highest level of European support.

If this elevated pace of European aid were sustained throughout the rest of the year, total allocations would reach approximately €80.7 billion – a figure that comes close to the original benchmark of €82 billion. While this projection remains hypothetical, it underscores the extraordinary scale of Europe’s response in the first trimester of 2025.

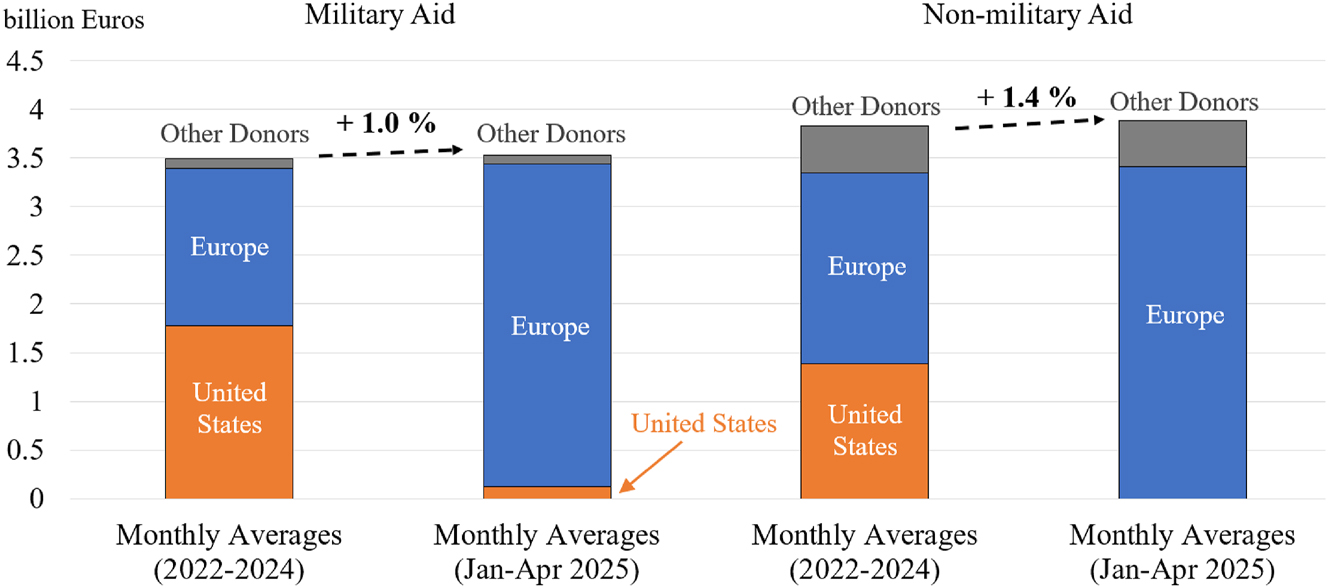

This increase in European aid has, in broad terms, helped to offset the halt in US aid allocation. Figure 4, which compares monthly average aid allocations during January–April 2025 with the average for the full period from 2022 to 2024, illustrates this point. Despite the absence of new US allocations, the monthly average level of aid to Ukraine in early 2025 was marginally higher, driven by a 1.0 percent increase in military aid and a 1.4 percent increase in non-military aid relative to the 2022–2024 average.

Monthly average aid allocations: 2022–2024 versus January–April 2025, by type of aid (in € billion). Source: Ukraine support tracker release 23 (Trebesch et al. 2024, 2025).

3.2 The Surge Was Not Collective: Imbalanced Contributions Across Europe

These figures suggest that, in aggregate monetary terms, European donors are broadly on track to meet the €82 billion benchmark. However, this aggregate performance conceals considerable variation across countries. A key question, therefore, is whether this increase in aid reflects a collective European effort or is largely the result of a few high-contributing countries shouldering most of the burden.

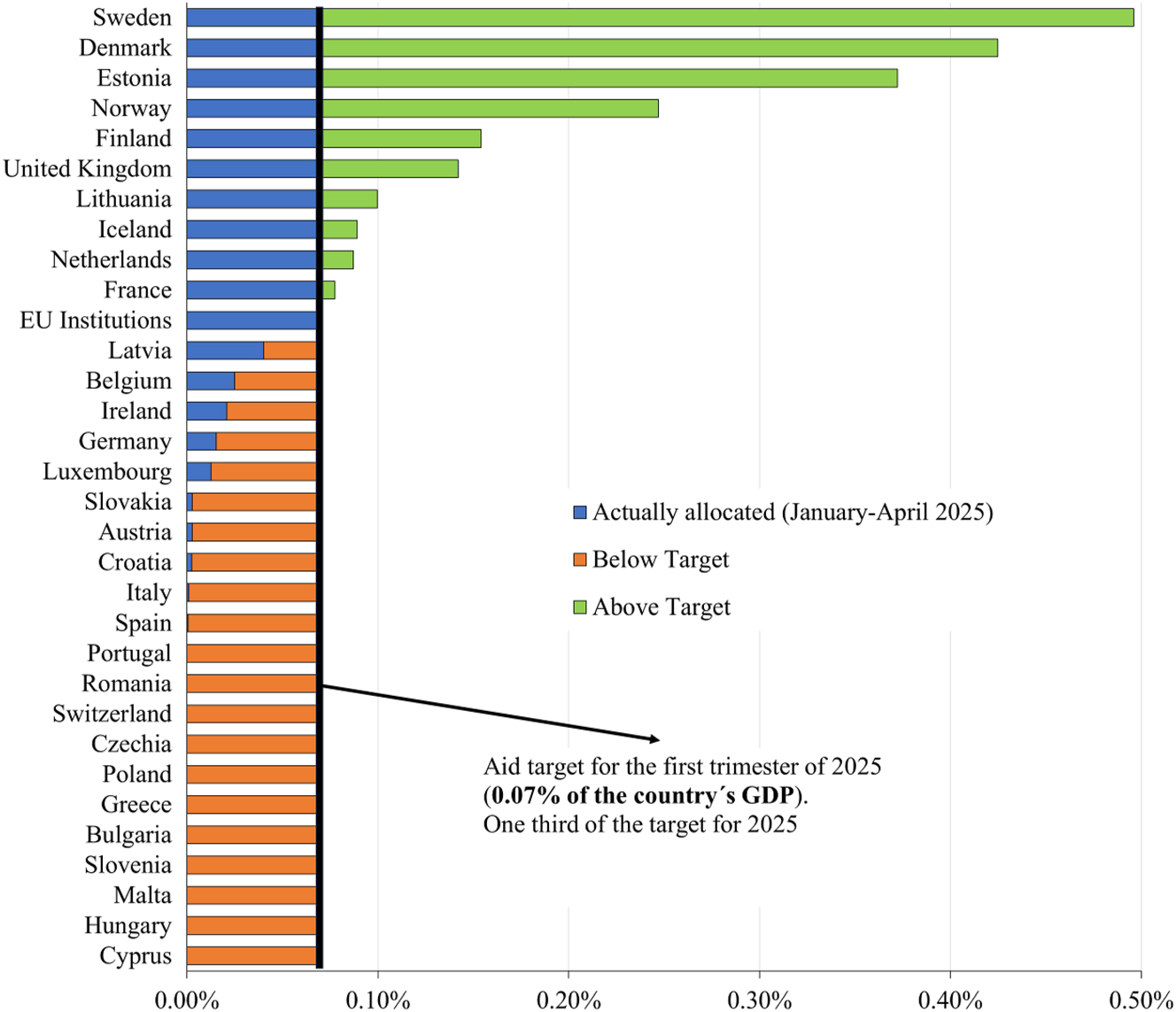

To assess this, we apply a proportional benchmark for the first four months of the year: if aid were allocated evenly across 2025, each country would be expected to allocate approximately 0.07 percent of GDP by the end of April – one-third of the annual 0.21 percent target. While aid disbursements are not always evenly distributed throughout the year and may be influenced by political or fiscal cycles, this benchmark provides a useful reference point for evaluating whether individual donors are broadly on track.

Figure 5 compares each donor’s aid allocations between January and April 2025 relative to their 2023 GDP. The data show that the recent European surge has been driven primarily by a limited number of countries, while many others remain well below the 0.07 percent threshold. Several countries – including Sweden (0.50 percent), Denmark (0.43 percent), Estonia (0.38 percent), and Norway (0.25 percent) – have already exceeded the full-year benchmark of 0.21 percent of GDP. Others, such as Finland (0.15 percent) and the United Kingdom (0.14 percent), are well ahead of pace.

Distance from the 0.07 percent of interim GDP benchmark: Aid allocation by donor, January-April 2025 (as a share of 2023 GDP). Source: Ukraine support tracker release 23 (Trebesch et al. 2024, 2025).

In addition, a group of donors appears broadly on track to reach the annual target if current levels of support are maintained. This includes Lithuania (0.10 percent), Iceland (0.09 percent), the Netherlands (0.09 percent), France (0.08 percent), and the EU institutions (0.07 percent).

By contrast, the remaining European donors – including major economies such as Germany, Spain, and Italy – have not yet met the four-month benchmark. Their current trajectory raises questions about whether they will be able to close the gap and reach the target by the end of 2025.

4 Assessing the Sustainability of the European Surge: Drivers and Constraints

In addition to the uneven distribution of aid across countries, there is considerable uncertainty regarding the sustainability of the current surge in European aid. While European donors appear broadly on track to meet the annual benchmark as of the first trimester of 2025, a key question remains: can this pace be sustained over the remainder of the year?

On the positive side, several large European economies have made substantial commitments for 2025, a significant portion of which has not yet been translated into formal allocations.[3] For instance, the German government has committed a total of €7 billion in support for Ukraine in 2025. As of April, however, only €0.65 billion – representing 9.3 percent of the committed amount – had been allocated to specific aid packages. This gap between commitment and allocation suggests that a substantial volume of additional support could still materialize in the second and third trimesters.

It is important to note, however, that not all committed funds are necessarily destined for direct support to Ukraine. Some may be allocated to the broader international response to the war – for example, social support for Ukrainian refugees residing in donor countries, or assistance to third countries affected by spillover effects of the conflict. While such uses are legitimate, they may reduce the volume of aid reaching Ukraine directly. Nonetheless, the existence of unallocated but committed funding offers a degree of flexibility that could help Europe sustain the current pace of aid allocations to Ukraine over the reminder of 2025.

On the other hand, several risk factors could undermine the sustainability of the current surge in European aid. First, it must be recognised that a portion of this increase is financed through interest revenues generated from frozen Russian assets, which does not reflect donors’ genuine budgetary efforts. The most prominent example is the ERA (Extraordinary Revenue Acceleration) loan mechanism, a joint initiative by G7 member states and the EU to provide Ukraine with up to €45 billion in loans, funded by interest accrued on immobilised Russian assets. Of the €26.9 billion allocated by Europe between January and April 2025, approximately €6.8 billion was channelled through ERA-backed financing – €1.8 billion from the United Kingdom and €5 billion from EU institutions. These two actors were among the largest contributors during this period. Given that ERA-related loans account for roughly 25 percent of total European aid in early 2025, concerns arise as to whether similar levels of support can be maintained once ERA funds are fully disbursed.

A second concern lies in the limited capacity of the European defence industrial base. While the first trimester of 2025 saw a notable increase in military aid in monetary terms, the ability to translate this funding into timely weapons deliveries depends heavily on industrial output. This constraint has become more pressing due to a structural shift in the nature of military aid: whereas early support for Ukraine was largely drawn from existing national stockpiles, recent assistance increasingly relies on procurement from defence industries (Bomprezzi et al. 2025). Although efforts are underway to expand production capacity across Europe, significant limitations remain – particularly for complex, high-demand systems such as multiple rocket launchers (e.g. HIMARS) and long-range air defence platforms (e.g. Patriot systems). These platforms continue to rely heavily on US manufactured weapons, and European countries currently lack the capability to provide them at scale independently. As a result, even if financial support continues to grow, Europe’s ability to deliver critical military equipment in sufficient quantity remains constrained, raising doubts about the long-term sustainability of current aid levels in the absence of US involvement.

In this context, Germany’s recent fiscal reform represents a notable shift. In March 2025, the Bundestag and Bundesrat approved a constitutional amendment allowing defence-related expenditures, including foreign aid to Ukraine, that exceed 1 percent of GDP to be excluded from the debt brake, which had previously capped structural borrowing at 0.35 percent of GDP. This adjustment creates additional fiscal space for military investment and offers Germany greater flexibility in scaling up defence procurement. It also positions the country to make progress toward its stated objective of raising defence spending to 3.5 percent of GDP by 2029, in line with NATO’s updated benchmark. While the measure remains specific to the German context, it reflects a broader recognition that increased fiscal flexibility may be essential for sustaining both national rearmament efforts and continued external support in a protracted conflict environment.

5 Conclusions

An analysis based on the updated Kiel Institute Ukraine Support Tracker dataset, which includes aid announced through April 2025, reveals that Europe has significantly increased its support to Ukraine – coinciding with the halt in new US aid allocations. As a result, European donors are broadly on track to meet the 0.21 percent of GDP benchmark, at least for the first third of the year. However, a closer examination suggests that this surge does not necessarily reflect Europe’s full capacity to replace US aid. Instead, it highlights a fragile surge, characterized by an unequal distribution of effort among donors and ongoing uncertainties about the sustainability of this elevated support.

Several policy implications emerge from this observation. First, European governments should consider establishing minimum benchmarks for national contributions to Ukraine-related aid. The surge in early 2025 has been driven largely by a small group of highly engaged countries – many of which were already among the leading donors between 2022 and 2024. By contrast, countries that contributed comparatively little in earlier years have, in most cases, not significantly increased their efforts. This suggests that the inequality in burden-sharing is not narrowing, but deepening. To address this, European donors could coordinate a more formal burden-sharing framework – such as GDP-based national targets – to encourage broader participation and greater accountability across the region. In this context, the recent agreement among NATO member states to raise their defense spending to at least five percent of GDP by 2035 is particularly relevant. Importantly, aid to Ukraine is included within this target, offering a potential framework for anchoring and institutionalizing a sustained European aid to Ukraine (NATO 2025).

Secondly, as noted in our March 2025 study, Europe must urgently invest in strengthening its own defense industrial base. While recent initiatives have made progress in expanding European production capacity, critical gaps remain. In particular, Europe still lacks the ability to supply Ukraine with complex and high-value weapons systems, such as long-range air defense platforms and multiple rocket launchers, at the scale and consistency that the United States has provided in recent years. The recent announcement that NATO may supply Ukraine with Patriot systems purchased from the United States offers a temporary solution, but it also highlights Europe’s structural dependency on US capabilities (BBC News 2025). In the context of an increasingly uncertain transatlantic environment, this reliance is unsustainable. Europe must therefore accelerate its efforts to develop indigenous production capacity for advanced systems and reduce long-term dependence on Washington’s support.

The observations and policy implications presented in this paper should be understood as interim rather than definitive. The situation remains fluid, and the analysis is based on short-term developments within a rapidly evolving policy environment. Nevertheless, the findings provide a data-informed early warning – highlighting both the scale of Europe’s recent efforts and the structural risks to their continuity. These developments warrant close and ongoing scrutiny. As the political and fiscal landscape continues to shift, sustained monitoring and timely follow-up will be essential to assess whether Europe can convert this fragile surge into a durable, equitable, and strategically grounded commitment to Ukraine.

References

BBC News. 2025. US has resumed military supplies to Ukraine, Zelensky says, 10 July https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/crl04200dp4o (accessed July 14, 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Bomprezzi, Pietro, Daniel Cherepinskiy, Giuseppe Irto, Ivan Kharitonov, Taro Nishikawa, and Christoph Trebesch. 2025. Ukraine Support After Three Years of War: Aid remains low but steady and there is a shift toward weapons procurement. 3rd Anniversary Report, Kiel Institute for the World Economy, February 2025. https://www.ifw-kiel.de/fileadmin/Dateiverwaltung/Subject_Dossiers_Topics/Ukraine/Ukraine_Support_Tracker/3rd_Aniv_Report.pdf (accessed July 14, 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Irto, Giuseppe, Ivan Kharitonov, Taro Nishikawa, and Christoph Trebesch. 2025. Ukraine Aid: How Europe Can Replace US Support. Kiel Policy Brief No. 186, Kiel Institute for the World Economy, March 2025. https://www.ifw-kiel.de/fileadmin/Dateiverwaltung/IfW-Publications/fis-import/c3f6146b-52c8-40d4-8e3e-78002913cb18-KPB_186_final_Version.pdf (accessed July 14, 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

NATO. 2025. The Hague Summit Declaration, adopted by Heads of State and Government, The Hague Summit, 25 June https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_236705.htm (accessed July 14, 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Trebesch, Christoph, Arianna Antezza, Yana Balanchuk, Pietro Bomprezzi, Katelyn Bushnell, Daniel Cherepinskiy, et al.. 2025. The Ukraine Support Tracker: Which Countries Help Ukraine and How? Kiel Working Paper No. 2218, 1–75. Kiel Institute for the World Economy. https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/ukraine-support-tracker-data-20758/ (accessed July 14, 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Trebesch, Christoph, Pietro Bomprezzi, and Ivan Kharitonov. 2024. Ukraine Support Tracker: Dataset Documentation. Kiel Institute for the World Economy. https://www.ifw-kiel.de/fileadmin/Dateiverwaltung/Subject_Dossiers_Topics/Ukraine/Ukraine_Support_Tracker/Dataset_Documentation.pdf (accessed July 14, 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The End of US Dominance?

- Policy Papers (No Special Focus)

- Alternative Policy Rules and Post-Covid Fed Policies

- Accountability in Action: The European Parliament’s Assessment of the ECB 2024 Annual Report

- Germany’s Fiscal Turn: Structural Challenges, Political Risks, and European Spillover Effects

- Trumpian Neomercantilism, European Fiscal Capacity and the Global Minimum Tax

- Factors Driving India’s Growth: Challenges and Policy Measures

- Policy Forum: The End of US Dominance?

- After Multilateralism: The US and the World Bank

- The Triple Mandate of Development, Climate, and Humanitarian Aid

- The WTO Minus One: A Rules-Based Global Trading System Without The US?

- The Fed in the Crosshairs

- Will China Replace the USA as the World’s Leading Power

- Will the US Protect Taiwan in Case of Chinese Military Aggression?

- War in Ukraine: Is Russia Challenging the US Global Dominance?

- A Fragile Surge: European Support to Ukraine in Early 2025 – New Insights from the Kiel Institute Ukraine Support Tracker

- A Strawman Proposal to Use International Flexibility in Achieving Developed Countries Climate Targets to Catalyse Global Decarbonisation

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- The End of US Dominance?

- Policy Papers (No Special Focus)

- Alternative Policy Rules and Post-Covid Fed Policies

- Accountability in Action: The European Parliament’s Assessment of the ECB 2024 Annual Report

- Germany’s Fiscal Turn: Structural Challenges, Political Risks, and European Spillover Effects

- Trumpian Neomercantilism, European Fiscal Capacity and the Global Minimum Tax

- Factors Driving India’s Growth: Challenges and Policy Measures

- Policy Forum: The End of US Dominance?

- After Multilateralism: The US and the World Bank

- The Triple Mandate of Development, Climate, and Humanitarian Aid

- The WTO Minus One: A Rules-Based Global Trading System Without The US?

- The Fed in the Crosshairs

- Will China Replace the USA as the World’s Leading Power

- Will the US Protect Taiwan in Case of Chinese Military Aggression?

- War in Ukraine: Is Russia Challenging the US Global Dominance?

- A Fragile Surge: European Support to Ukraine in Early 2025 – New Insights from the Kiel Institute Ukraine Support Tracker

- A Strawman Proposal to Use International Flexibility in Achieving Developed Countries Climate Targets to Catalyse Global Decarbonisation