Clinical benefit of measuring both haemoglobin and transferrin concentrations in faeces: demonstration during a large-scale colorectal cancer screening trial in Japan

Abstract

Background: While the faecal immunochemical test for haemoglobin (FIT) is an important screening tool to detect gastrointestinal bleeding, false-negative cases resulting from the enterobacterial degradation of haemoglobin (Hb) have emerged. When faecal Hb tests have given false-negative results, it is considered that digestive bleeding diseases can be detected by measuring faecal transferrin (Tf), which is less susceptible to enterobacterial degradation. This study evaluated the benefit of measuring both Hb and Tf as markers of blood in the faeces during a large-scale colorectal cancer screening trial in Japan.

Methods: We screened 12,255 participants, i.e., 8223 men and 4032 women, for faecal Hb and Tf using a Discrete Clinical Chemistry Analyser NS-Plus C15 system.

Results: Among the 1232 participants with positive test results for blood, 417 were detected based solely on Tf, which increased the positive rate from 6.7% to 10.1%. The Hb and Tf concentrations were not correlated directly, thereby suggesting that Tf can detect a positive group that differs from that detected based on Hb. The positive rate for Tf alone was significantly higher in women (4.9%) compared with men (2.7%) (p<0.0001), which may be explained by the significantly higher constipation complaint rate in the Tf-positive group compared with the haemoglobin-only-positive group (p=0.0069).

Conclusions: The results of this large-scale colorectal cancer screening study suggest that analysing both Hb and Tf using an NS-Plus system should be beneficial for subjects who are missed by conventional Hb testing alone.

Introduction

In Japan, the number of patients with colorectal cancer has increased steadily and the death rate due to colorectal cancer is higher in women than that attributable to any other form of cancer. Early detection of colorectal cancer by screening reduces the mortality rate.

The faecal immunochemical test for haemoglobin (FIT) is used widely in screening to facilitate the early detection of colorectal cancer [1]. The efficacy of the FIT in colorectal cancer screening has been established, but false-negative results cannot be avoided, which is a drawback of this method. A retrospective study by Uotani et al. showed that 36.3% of cancer patients had false-negative FIT results and 25% of these patients had advanced cancer [2]. Half of the advanced cancer cases were detected in the ascending colon, thereby confirming the weakness of FIT in detecting lesions in the distal part of the colon. Uchida et al. suggested that the degradation of haemoglobin (Hb) by faecal enterobacteria was the cause of the false-negative results [3]. Fujita et al. noted that a longer intestinal retention time for faeces decreases the sensitivity of the test [4].

Transferrin (Tf) is an iron-transporting protein (molecular weight=76,500 Da) that is synthesised mainly in the liver and is present at a concentration of 2.0–3.0 g/L in normal serum. The blood concentration of Tf is 1%–2% that of Hb, but Tf is highly stable and is considered to be a more sensitive indicator of bleeding than Hb, even when the intestinal retention time for faeces is long [3]. In the present study, we investigated the benefit of measuring both Hb and Tf in faeces during a large-scale colorectal cancer screening trial to identify subjects for further screening.

Materials and methods

Participants

From April 2009 to March 2010, the faecal Tf concentration was determined in addition to the usual faecal Hb concentration in 12,255 participants (8223 men and 4032 women) who visited the Health Care Center, Japan Community Health Care Organization, Sakuragaoka Hospital, Shizuoka, Japan, for a health examination and testing for blood in their faeces.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Japan Community Health Care Organisation, Sakuragaoka Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Specimen collection container and collection of faeces

The specimen collection container (Specimen Collection Container A, Alfresa Pharma Corporation, Osaka, Japan) was suitable for the collection of 10 mg of faeces and a serrated probe was attached to the cap, with 1.9 mL of buffer in the container. The participants provided specimens in containers. They removed the probe from the container and scraped it evenly across several regions of the surfaces of their faeces until the grooved portion of the probe collected a sample of faeces. The participants wrote the date of sample collection on the label. The container was then stored in a cool and dark place until it was returned to the hospital. The samples of faeces were collected within 5 days and brought to the Health Care Center.

2-Day method

Both the Hb and Tf tests were performed using the 2-day method. In this method, each subject collects faecal specimens in separate containers on two different days. The result is considered to be positive if either specimen is positive. Both the Hb and Tf analyses were performed using an automatic analyser with colloidal gold reagents, as described in the next section. Each specimen collection container can be used for both of the tests in this system, thus the two tests were performed simultaneously with a single specimen collection container.

In the FIT, the sensitivity differs between the 1-day and 2-day methods, but there is little difference in sensitivity between the 2-day and 3-day methods. Thus, we used the 2-day method, which is cost effective and used widely throughout Japan.

Measurement instrument and reagents

Instrument

A Discrete Clinical Chemistry Analyser NS-Plus C15 (Otsuka Electronics Company Limited, Osaka, Japan) with a processing capacity of 300 tests per hour was used. All the assays were performed using single samples, although this analyser was able to perform multiple measurements using up to nine replicates. The analytical working range was 4–240 μg Hb/g faeces. Remeasurement of samples with concentrations above the analytical working limit was performed by the automatic retest function of the instrument. This function allowed the instrument to recognize samples with concentrations above the analytical working limit and to calculate appropriate dilution rates from rough estimates before diluting and measuring the specimens again automatically.

Reagents

Hb was measured in faeces using i-FOBT Hemoglobin NS-Plus (Alfresa Pharma Corporation) and Tf was measured in faeces using i-FOBT Transferrin NS-Plus (Alfresa Pharma Corporation) according to a method based on immunological colloidal gold agglutination, as described in the next section.

Assay principle: immunological colloidal gold agglutination method

When colloidal gold-labelled polyclonal anti-human Hb or Tf antibodies react with human Hb or Tf in faeces, the antigen–antibody reaction causes the colloidal gold particles to aggregate, which is accompanied by a change in colour. The concentration of human Hb or Tf in faeces was measured by analysing this change in colour optically and based on the increase in turbidity over a specified period.

Quality management and data handling

All of the analyses were carried out by three clinical laboratory technicians who performed the FIT and a wide range of other analyses. The Health Care Center has a total quality management system.

Cut-off concentrations

Up to three cut-off concentrations can be set using the instrument. In Japan, the same institution may set and store more than one cut-off concentration and use different cut-off concentrations depending on the specific purpose. The cut-off concentration may be set higher in large-scale screenings covered by public insurance, such as wide-area residential health examinations, in order to minimise the false-positive rate, thereby reducing the costs of unnecessary endoscopies. In private clinics, the cut-off concentration can be set lower for medical check-up participants who are willing to pay for the increased fees incurred by multiphasic health examinations. The concentration of Tf or other substances is often measured in addition to Hb in private medical facilities. In the present study, the cut-off concentrations were set at 20 μg Hb/g faeces for Hb and 10 μg Hb/g faeces for Tf, which are the standard cut-off concentrations that are used most widely in Japan [5].

Statistics

The χ2-test was used to test for significant differences between non-parametric data, such as the male:female ratio and constipation ratio. For parametric data, unpaired t tests were performed to compare the means of the measured values, and the 95% confidence intervals were also compared. A p-value <0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Interpretation of test results

The present study employed the 2-day method using two analytes (Hb and Tf), thus 16 results are shown in sections [a] to [d] of Table 1. The results were interpreted as follows. [a] Cases with negative Hb and Tf results on both days were classified as “negative”. [b] Cases with a positive Hb result on either or both days and a negative Tf result on both days were classified as “Hb-only positive”. [c] Cases with positive Hb and Tf results on either or both days were classified as “both Hb and Tf positive”. [d] Cases with a positive Tf result on either or both days and a negative Hb result on both days were classified as “Tf-only positive”. [e] Cases with a positive Hb or Tf result on either or both days were classified as “positive”. This included all cases except the negative case [a], where Hb and Tf were both negative on both days, i.e., [b]+[c]+[d], as shown in Table 1. [f] Cases with a positive Hb result on either or both days regardless of the Tf results were classified as “Hb positive”, i.e., [b]+[c], as shown in Table 1. [g] Cases with a positive Tf result on either or both days regardless of the Hb results were classified as “Tf positive”, i.e., [c]+[d], as shown in Table 1.

Classification of results.

| Hb | Tf | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 1 | Day 2 | ||

| a | Negative | – | – | – | – |

| b | Hb-only positive | + | – | – | – |

| – | + | – | – | ||

| + | + | – | – | ||

| c | Both Hb and Tf positive | + | – | + | – |

| + | – | – | + | ||

| + | – | + | + | ||

| – | + | + | – | ||

| – | + | – | + | ||

| – | + | + | + | ||

| + | + | + | – | ||

| + | + | – | + | ||

| + | + | + | + | ||

| d | Tf-only positive | – | – | + | – |

| – | – | – | + | ||

| – | – | + | + | ||

| e | Positive (b+c+d) | ||||

| b | + | – | – | – | |

| – | + | – | – | ||

| + | + | – | – | ||

| c | + | – | + | – | |

| + | – | – | + | ||

| + | – | + | + | ||

| – | + | + | – | ||

| – | + | – | + | ||

| – | + | + | + | ||

| + | + | + | – | ||

| + | + | – | + | ||

| + | + | + | + | ||

| d | – | – | + | – | |

| – | – | – | + | ||

| – | – | + | + | ||

| f | Hb positive (b+c) | ||||

| b | + | – | – | – | |

| – | + | – | – | ||

| + | + | – | – | ||

| c | + | – | + | – | |

| + | – | – | + | ||

| + | – | + | + | ||

| – | + | + | – | ||

| – | + | – | + | ||

| – | + | + | + | ||

| + | + | + | – | ||

| + | + | – | + | ||

| + | + | + | + | ||

| g | Tf positive (c+d) | ||||

| c | + | – | + | – | |

| + | – | – | + | ||

| + | – | + | + | ||

| – | + | + | – | ||

| – | + | – | + | ||

| – | + | + | + | ||

| + | + | + | – | ||

| + | + | – | + | ||

| + | + | + | + | ||

| d | – | – | + | – | |

| – | – | – | + | ||

| – | – | + | + | ||

Hb, haemoglobin; Tf, transferrin; –: negative, +: positive.

Definition of constipation

The health check-up participants were asked to complete an interview form in advance. The questionnaire items included asking whether the examinee “tends to be constipated”, where the answer was either “yes” or “no”. Those who answered “yes” were included in the constipation group and those who answered “no” were included in the non-constipation group.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Table 2 shows the sex, age, height, body weight and body mass index data for the participants in this study. The male:female ratio was 2:1, the median age was 51 years and the age range was 19–88 years.

Demographic data of participants.

| Parameter | Results |

|---|---|

| Male/female (percentage) | 8223/4032 (67%/33%) |

| Median age (range) | 51 (19–88) years |

| Median height (range) | 165.1 (111.4–192.3) cm |

| Median weight (range) | 61.3 (29.7–135.1) kg |

| Median body mass index (range) | 22.4 (13.4–47.8) kg/m2 |

Positive rates and relationships

The addition of the Tf test to the Hb test increased the positive rate from 6.7% with the conventional test (i.e., Hb-positive group) to 10.1% (i.e., positive group).

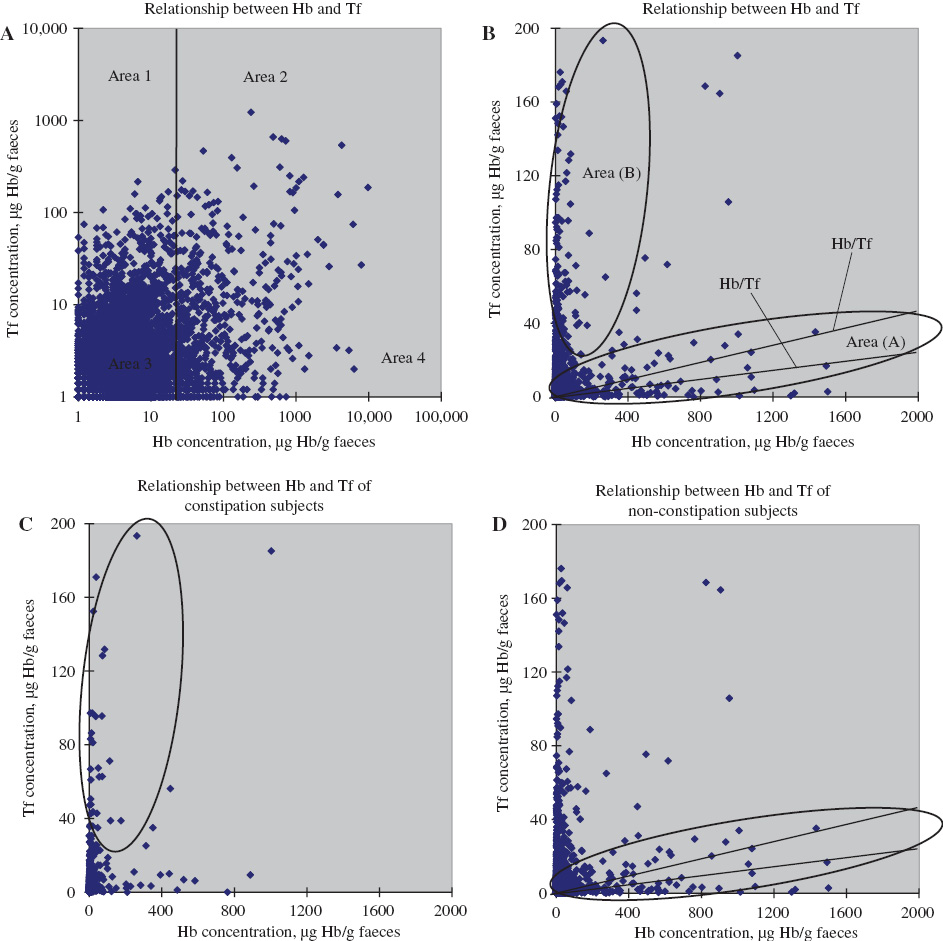

Figure 1A shows the concentrations of Hb and Tf on the logarithmic x- and y-axes, respectively, and their cut-off concentrations. The vertical line is the cut-off concentration for Hb and the horizontal line is the cut-off concentration for Tf. Areas 1, 2, 3 and 4 indicate Tf-only positive, both Hb and Tf positive, negative and Hb-only positive results, respectively. The proportions for areas 1, 2, 3 and 4 are 3.4%, 1.6%, 89.9% and 5.0%, respectively. FIT alone detected only 6.7% in areas 2 and 4, but the addition of the Tf test detected 3.4% in area 1.

Relationship between haemoglobin (Hb) and transferrin (Tf).

(A) Areas divided based on the Hb and Tf cut-off concentrations. The data are plotted on logarithmic axes. (B) Hb-intact and Hb-denatured areas. (C) Constipated group. (D) Non-constipated group. (B)–(D) The data ranges on the x- and y-axes have been reduced by 50 times relative to that used in (A) to illustrate the trends more clearly.

As shown in Figure 1B, the Hb and Tf concentrations were not correlated, which suggests that the Tf test identified a different group compared with that detected by the conventional Hb test. The relative Hb:Tf ratio in blood is considered to be 50:1 to 100:1. Figure 1B shows the Hb-intact area (A), which is approximately 50:1 to 100:1, and the Hb-denatured area (B), where the Hb concentration is reduced remarkably compared with the Tf concentration.

Figure 1C and D show plots for the constipation and non-constipation participants, respectively. The constipation and non-constipation groups tended to be distributed in the Hb-denatured and Hb-intact areas, respectively.

Differences in the positive rates between men and women

As shown in Table 3, the Hb-positive rate was significantly higher in men (7.1%) compared with that in women (5.7%) (p=0.0037). By contrast, the Tf-only-positive rate was significantly lower in men (2.7%) compared with that in women (4.9%) (p<0.0001).

Positive rates in male and female participants.

| Hb positive | Tf-only positive | Positive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 7.1% | 2.7% | 9.8% |

| (n=8223) | (587/8223) | (221/8223) | (808/8223) |

| Female | 5.7% | 4.9% | 10.5% |

| (n=4032) | (228/4032) | (196/4032) | (424/4032) |

| p-Value | 0.0037a | <0.0001a | 0.2813 |

aSignificantly different according to the χ2-test. Hb, haemoglobin; Tf, transferrin.

Constipation complaint rate

Table 4 shows that the constipation complaint rate was significantly higher in the Tf-positive group compared with that in the Hb-only-positive group (p=0.0069).

Constipation rates in haemoglobin (Hb)-only-positive and transferrin (Tf)-positive participants.

| Negative | Hb-only positive | Tf positive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number with constipation (Yes) | 964 | 72 | 105 |

| Number without constipation (No) | 10,059 | 545 | 510 |

| Constipation rate | 8.7% | 11.7% | 17.1% |

| p-Value | Negative vs. Hb-only positive | Hb-only positive vs. Tf positive | Tf positive vs. Negative |

| 0.0131a | 0.0069a | <0.0001a |

aSignificantly different according to the χ2-test.

Distributions and mean Hb and Tf concentrations in the constipation and non-constipation groups

The mean values (95% confidence intervals) of the Hb and Tf concentrations in the constipation and non-constipation groups were 25.9 μg Hb/g faeces (12.8–39.0 μg Hb/g faeces) and 6.1 μg Tf/g faeces (4.6–7.6 μg Tf/g faeces), and 15.2 μg Hb/g faeces (12.0–18.3 μg Hb/g faeces) and 3.2 μg Tf/g faeces (2.8–3.5 μg Tf/g faeces), respectively. The confidence intervals for Tf did not overlap in the two groups and the Tf concentration was significantly higher in the constipation group compared with that in the non-constipation group (p=0.0002, unpaired t test). Although the Hb concentration tended to be higher in the constipation group compared with that in the non-constipation group, their confidence intervals overlapped and the difference was not significant (p=0.1202, unpaired t test).

Discussion

The 3.4% increase in the positive rate obtained by the addition of the Tf test (Tf-only-positive group) can be explained by the presence of blood due to bleeding. The Hb would have undergone degradation by enterobacteria, so a bleeding false-negative result was obtained based on the Hb test because the faeces remained in the large intestine for a long time, thus only the Tf test yielded a positive result. This suggests that the sensitivity (colorectal cancer detection rate based on bleeding) of health check-ups can be increased by adding the Tf test.

There are two possible causes of prolonged faecal retention times: bleeding in the ascending colon and constipation. With bleeding in the ascending colon, Hb is likely to be degraded because it takes longer to excrete faeces from this part of the colon compared with the descending colon or rectum. Even with rectal bleeding, Hb may also be degraded and bleeding false-negative results may be obtained if the subject has severe constipation. In these cases, measuring the Tf concentration may provide a complementary method if bleeding false-negative results are obtained using the Hb test.

Women are considered to be more prone to constipation because of the effects of oestrogen. Table 3 shows the differences in the positive rates between men and women. The Hb-positive rate was significantly higher in men compared with that in women. However, the positive rate was nearly the same in men and women when both Hb and Tf were measured (p=0.2813). Thus, the conventional Hb test yielded a higher positive rate in men, but the addition of the Tf test eliminated the difference between men and women. Therefore, the Tf test may be particularly effective when bleeding false-negative results are obtained for women according to the Hb test.

In a clinical-histopathological investigation, Oono et al. reported that advanced colorectal cancer with false-negative results according to the FIT tended to occur in the ascending colon and the caecum in women [6]. Thus, cancer patients with false-negative results according to the Hb test may be identified by the Tf test. A retrospective study by Miyoshi et al. reported that 11.7% of patients with colorectal cancer and 17.9% of patients with colorectal polyps had Tf-only-positive results, although the sample size was small [7]. Sheng et al. also reported that 15.0% of patients with colorectal cancer and 33.3% of patients with precancerous lesions (adenomatous polyps and ulcerative enteritis) had Tf-only-positive results [8].

In terms of the FIT, Fraser et al. [9] and Brenner et al. [10] reported that men have higher positive rates than women. Men are more likely to develop colorectal cancer than women, and men are prone to experiencing bleeding in the bowel. This implies that different cut-off concentrations should be applied for men and women. However, women tend to be more prone to constipation than men. As a result, it may be argued that the FIT-positive rate could be reduced in women because of Hb degradation in the bowel, thereby yielding bleeding false-negative results. Therefore, the addition of the Tf test to avoid obtaining false-negative results from the Hb test may be beneficial, as well as using different cut-off concentrations for men and women, or for constipated and non-constipated subjects. Further research is required to determine the most effective approach, but increasing the sensitivity of the test employed without reducing its specificity is important.

Recently, Hirata et al. proposed the following two-step cut-off method for use in Japan [5]. Set the first cut-off concentration for Hb (e.g., 20 μg Hb/g faeces). Subjects with concentrations higher than this first cut-off concentration proceed to a second round of screening, such as colonoscopy. Next, set the second cut-off concentration for Hb (e.g., 10 μg Hb/g faeces). Subjects with concentrations between the first and second cut-off concentrations are then subjected to the Tf test, and any Tf-positive subjects proceed to the second round of screening. Other researchers have also been designing methods that combine inflammatory markers such as lactoferrin and calprotectin with Hb. To make the FIT more effective, we expect that future studies will test the use of different cut-off concentration in subjects, or other markers in addition to Hb.

We hypothesize that patients with colorectal cancer that is not detected by the conventional Hb test because of the Hb degradation associated with constipation may be identified by the addition of the Tf test. This hypothesis requires validation in further studies.

In the present study, the definition of constipation was based on the judgement of the individual. However, the criteria used for constipation in large-scale colorectal cancer screening studies need to be fully established in the future. This will allow us to conduct further investigations into the relationship between constipation and false-negative results to detect bleeding (bleeding false negatives).

In conclusion, this large-scale medical examination-based study confirmed the benefit of employing a combination of Hb and Tf tests to detect blood in faeces, thereby reducing the false-negative rate. The NS-Plus analyser allows the simultaneous analyses of Hb and Tf, and it was shown to be useful for large-scale screening to detect colorectal cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Dr. Masahiro Murakami, Faculty of Pharmacy, Osaka Ohtani University, for his advice on this report.

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: None declared.

Employment or leadership: None declared.

Honorarium: None declared.

Competing interests: The funding organization(s) played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

1. Lee K-J, Inoue M, Otani T, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Tsugane S. Colorectal cancer screening using fecal occult blood test and subsequent risk of colorectal cancer: a prospective cohort study in Japan. Cancer Detect Prev 2007;31:3–11.10.1016/j.cdp.2006.11.002Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Uotani C, Mai M. A review of false negative findings in immunological fecal occult blood testing. Nihon Shoukaki Gan Kenshin Gakkai zasshi (The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Cancer Screening) 2007;45:204–13 [In Japanese].Search in Google Scholar

3. Uchida K, Matsuse R, Miyachi N, Okuda S, Tomita S, Miyoshi H, et al. A new immunochemical fecal occult blood test combination assay of haemoglobin and transferrin. Rinsho Byori (The Official Journal of Japanese Society of Laboratory Medicine) 1982;37: 58–62 [In Japanese].Search in Google Scholar

4. Fujita M, Sakamoto Y. A novel trial to improve the effectiveness of immunochemical fecal occult blood screening for colorectal cancer by using a supplement of dietary fiber. Nihon Shokaki Shudankenshin Gakkai Zasshi (Journal of Gastroenterological Mass Survey) 2003;41:276–83 [In Japanese].Search in Google Scholar

5. Hirata I, Yoshioka D, Shibata T, Nagasaki M, Takahama K, Matsuse R. 5. Early stage colorectal cancer screening 1) A fecal occult blood test – hemoglobin and transferrin simultaneous assay. I to Cho (Stomach and Intestine) 2010;45:725–33 [In Japanese].Search in Google Scholar

6. Oono Y, Iriguchi Y, Oura M, Nakamura N, Tomino Y, Oda J, et al. A clinical histopathological investigation of advanced colorectal cancer with false-negative results. Nihon Shokakigan Kenshin Gakkai Zasshi (Journal of Gastroenterological Cancer Screening) 2007;45:421–5 [In Japanese].Search in Google Scholar

7. Miyoshi H, Ohshiba S, Asada S, Hirata I, Uchida K. Immunological determination of fecal haemoglobin and transferrin concentrations: a comparison with other fecal occult blood tests. Am J Gastroenterol 1992;87:67–73.Search in Google Scholar

8. Sheng J, Li S, Wu Z, Xia C, Wu X, Chen J, et al. Transferrin dipstick as a potential novel test for colon cancer screening: a comparative study with immune fecal occult blood test. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:2182–5.10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0309Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Fraser CG, Rubeca T, Rapi S, Chen LS, Chen HH. Faecal haemoglobin concentrations vary with sex and age, but data are not transferable across geography for colorectal cancer screening. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014;52:1211–6.10.1515/cclm-2014-0115Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Brenner H, Haug U, Hundt S. Sex differences in performance of fecal occult blood testing. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105: 2457–64.10.1038/ajg.2010.301Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2014, Yoshinori Takashima et al., published by De Gruyter.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Measuring diagnostic safety of inpatients: time to set sail in uncharted waters

- Review

- Clinical criteria to screen for inpatient diagnostic errors: a scoping review

- Original Articles

- Types of diagnostic errors in neurological emergencies in the emergency department

- Missed diagnoses of acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department: variation by patient and facility characteristics

- Assessment of machine-learning techniques on large pathology data sets to address assay redundancy in routine liver function test profiles

- Clinical benefit of measuring both haemoglobin and transferrin concentrations in faeces: demonstration during a large-scale colorectal cancer screening trial in Japan

- Classical vs. unit area method in the evaluation of differential renal function in unilateral hydronephrosis

- Comparison of two methods for measuring methylmalonic acid as a marker for vitamin B12 deficiency

- Case Report

- A case of factitious hyponatremia and hypokalemia due to the presence of fibrin gel in serum

- Letter to the Editor

- Diagnostic difficulties in homozygous hemoglobin E disorders

- Erratum

- Benefits and limitations of laboratory diagnostic pathways

- DEM Congress Abstracts

- Diagnostic Error in Medicine 7th International Conference

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Measuring diagnostic safety of inpatients: time to set sail in uncharted waters

- Review

- Clinical criteria to screen for inpatient diagnostic errors: a scoping review

- Original Articles

- Types of diagnostic errors in neurological emergencies in the emergency department

- Missed diagnoses of acute myocardial infarction in the emergency department: variation by patient and facility characteristics

- Assessment of machine-learning techniques on large pathology data sets to address assay redundancy in routine liver function test profiles

- Clinical benefit of measuring both haemoglobin and transferrin concentrations in faeces: demonstration during a large-scale colorectal cancer screening trial in Japan

- Classical vs. unit area method in the evaluation of differential renal function in unilateral hydronephrosis

- Comparison of two methods for measuring methylmalonic acid as a marker for vitamin B12 deficiency

- Case Report

- A case of factitious hyponatremia and hypokalemia due to the presence of fibrin gel in serum

- Letter to the Editor

- Diagnostic difficulties in homozygous hemoglobin E disorders

- Erratum

- Benefits and limitations of laboratory diagnostic pathways

- DEM Congress Abstracts

- Diagnostic Error in Medicine 7th International Conference