Abstract

This article examines the autobiographical writings of Sarah Bernhardt and Fatima Rushdi as strategic acts of self-fashioning that articulate transnational modes of fin-de-siècle New Womanhood. Through a comparative analysis of Bernhardt’s Ma Double Vie and Rushdi’s memoirs, particularly Fatima Rushdi bayn al-Hubb wal-Fann, the study explores how theatrical women performers employed life writing to craft public identities that challenged prevailing gender norms. Drawing on feminist theory, autobiography studies, and performance theory, the article argues that both figures used narrative self-construction to assert artistic agency and resist patriarchal constraints. Bernhardt’s flamboyant cosmopolitanism contrasts with Rushdi’s grounded nationalism, yet both converge in their symbolic use of cross-gender theatrical roles – Hamlet and Napoleon II – as vehicles of gender transgression. Positioned within the broader framework of celebrity culture and transnational feminism, their autobiographical narratives highlight how local and global discourses of modernity, resistance, and cultural reform intersect in women’s self-representations. By examining their life writings as performative acts, the article redefines autobiography not merely as personal recollection, but as a political medium for constructing feminist selves across borders. Ultimately, the study contributes to rethinking the New Woman archetype beyond Eurocentric paradigms, emphasizing how autobiographical performance enabled women like Bernhardt and Rushdi to renegotiate womanhood on their own terms.

1 Introduction

The “long” nineteenth century was an age of revolutionary upheavals and accelerated modernity, reshaping political structures, cultural practices, and gender norms across Europe and beyond. The democratization of culture and the rise of mass media gradually destabilized older hierarchies of representation, allowing figures outside the traditional elite to construct public identities of their own. With the spread of photography, illustrated journalism, and serialized print culture, a new form of celebrity culture emerged in which performers, writers, and activists fashioned themselves as cultural icons. These technologies of visibility created unprecedented opportunities for women to step into the public sphere, making self-fashioning a crucial element of fin-de-siècle culture.

Autobiographical writing became central to this new culture of representation. Memoirs, often serialized, satisfied public appetite for access to the intimate lives of famous figures while offering marginalized voices – ex-slaves, exiles, minorities, and women – a vehicle for political self-expression. As Doğan Gürpinar argues, memoir-writing flourished as a polemical form for authors with a “cause” (2012, p. 538), demonstrating that life writing was never a neutral record but always implicated in broader ideological debates. (Life) women writers of the late-Victorian/fin-de-siècle New Woman movement “question traditional gender roles, promote sisterhood among women, proclaim women’s control over their own bodies, reject normative sexuality and assert their right to shape their own lives” with the objective of “mak[ing] their voices and ideas heard through their art or their writing” (Louati, 2022, para. 18). In this sense, the feminist slogan “the personal is political” originally associated with the second wave of American women’s movement (Lee, 2007, p. 163), could well be traced back to the beginning of the long nineteenth century, or, in other words, “the modern world” (p. 166). Romantic women’s life narratives had already challenged conventions of respectability and sentimentality (Civale, 2019), but by the late nineteenth century, New Woman memoirs developed this further. As Heilmann (2000) notes, such texts blurred fiction and autobiography, dramatizing tensions between the personal and the professional, the national and the global, and offering new models of feminist selfhood.

While scholarship on the New Woman has often been dominated by Anglo-European contexts, life writing traditions in non-Western cultures complicate and enrich this framework. In the Arab world, autobiography has long been recognized as a particularly charged genre for women, where the act of narrating the self frequently collides with cultural prescriptions of modesty, silence, and domestic containment. As Samia Kholoussi observes, women’s autobiographies in the region occupy “a tension-ridden arena” that provokes both fascination and disapproval, precisely because they render visible experiences traditionally effaced from public discourse (2019, p. 287). In this sense, the very act of writing constitutes a form of transgression. Arab feminist thinkers such as Nawal El Saadawi insist that to write is to rebel (1999, p. 352), framing autobiography not as passive confession but as an intentional act of defiance against patriarchal erasure. Similarly, Mikhail (2004) emphasizes how modern Arab women writers, through memoirs, letters, and autobiographical fiction, have used narrative to craft spaces of agency and cultural critique, insisting on women’s presence in the historical record.

Within this framework, the life writings of the Egyptian theater actress, singer, film director, and producer Fatima Rushdi (1908–1996) are best understood as part of a broader Arab feminist tradition of using autobiography to negotiate questions of gender, nation, and modernity. Her memoirs do not merely record a theatrical career but actively challenge cultural scripts that sought to limit women’s participation in public life, situating her voice within Egypt’s nationalist and anti-colonial struggles. Approaching Rushdi’s autobiographical writings alongside Ma Double Vie (My Double Life), the autobiographical book published by the world-class French stage actress and performer Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923) illuminates two distinct but interconnected trajectories of women’s self-fashioning: one rooted in European celebrity culture and cosmopolitan spectacle, the other grounded in Arab feminist strategies of resistance and national reform. Such a comparative lens underscores the need to move beyond Eurocentric paradigms of the New Woman, highlighting instead the plurality of autobiographical practices across cultural geographies. By engaging with both Western and non-Western traditions of life writing, this study contributes to a more inclusive understanding of how women across different contexts mobilized the genre as a performative strategy to reimagine gender and modernity.

The personal memoirs of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt are investigated and revisited, not only as prominent samples of fin-de-siècle women’s life writing in the French/English and Arabic languages, but also as life narratives through which the various ramifications of the New Woman movement worldwide are characteristically showcased. Crafting themselves as iconic figures of fin-de-siècle new womanhood, Rushdi and Bernhardt used life writing to assert their agency, challenge gender norms, and negotiate their public and private identities. While Bernhardt’s memoirs reflect a cosmopolitan, performative self-fashioning that transcends national boundaries, Rushdi’s autobiographical writings reveal a deeply localized struggle for modernity within the context of Egypt’s nationalist/anticolonial movement. By comparing their life writings, this article argues that both women used personal memoirs as a tool to redefine womanhood in their respective societies, yet their narratives underscore the distinct regional and cultural contours of the “New Woman” archetype.

1.1 The Power of Self-Writing: Crafting the “New Woman” Identity

At the turn of the twentieth century, autobiography was more than a private narrative form for it became a cultural tool through which individuals, especially women, negotiated their place in rapidly transforming societies. Furthermore, autobiographical narratives emerged as a medium by which women/authors not only wrote but also performed their identities, to borrow Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson’s assertion in their Life Writing in the Long Run: A Smith & Watson Autobiography Studies Reader, that life writing is not merely a recounting of events, but a performance of identity shaped by social, political, and historical contexts. Smith and Watson (2016) discuss how autobiographical writing serves as a means of self-construction, noting that life narratives are not merely reflections of a pre-existing self but are instrumental in shaping and performing identity, making these writings an act of creating the self within the narrative. This dynamic might be particularly pronounced in the case of women who were performers by profession, specifically, actresses whose life writings may offer a unique intersection between narrative self-construction and the theatrical performance of a persona. For actresses/women authors such as Sarah Bernhardt and Fatima Rushdi, writing the self was an act of defiance and self-authorization, particularly in cultural climates where female agency was heavily policed. Their autobiographical narratives offer insight into how theatrical women performers used self-writing to assert authority over their public image and resist the confines of traditional gender roles.

Compared to nineteenth-century female autobiographies, male autobiographies of the same period were often shaped by Enlightenment ideals of the rational, autonomous self, as figures like Jean-Jacques Rousseau or Benjamin Franklin framed their life stories as linear narratives of progress, mastery, and public achievement. These texts typically emphasized individual will, moral fortitude, and the pursuit of greatness, mirroring patriarchal structures that encouraged male self-expression and public recognition. Alternatively, women’s autobiographies from the same period were frequently constrained by expectations of modesty, domesticity, and sentimentality. As Marcus (1994) notes in Auto/biographical Discourses, female self-writing was often “apologetic,” embedded within discourses of respectability that limited women’s ability to assert ambition or desire. However, rather than simply replicating these conventions, many women subverted them, using emotional candor, relational narratives, or performative self-fashioning to claim authority.[1] For theatrical women like Bernhardt and Rushdi, whose careers depended on visibility and transformation, autobiography became a stage in itself: a space where the traditionally private female self could become legible, political, and powerful, both written in text and played on stage.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the New Woman archetype emerged and was discussed in relation to the rise of feminism and shifts in societal roles during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the section titled “New Woman”, Rabinovitch-Fox (2017) discusses how education and employment reshaped women’s identities insofar as [the] New Woman became associated with the rise of feminism and the campaign for women’s suffrage, as well as with the rise of consumerism, mass media, and changes in women’s education, employment, and family roles. The figure of the “New Woman” embodied a growing challenge to established gender norms, symbolizing women’s increasing access to education, professions, and public life. In Europe, the New Woman appeared in fiction, periodicals, and political debates as both an aspirational model and a social threat, at once emancipated and deviant. Her emergence coincided with urbanization, industrialization, and the expansion of print culture, all of which facilitated new forms of female visibility. In Egypt, the New Woman archetype was shaped by overlapping forces of colonialism, nationalism, and modernity. Among other contributing factors, fin-de-siècle discourse on women’s liberation in Egypt is most commonly associated with the pioneering work of the Egyptian jurist and Islamic modernist/nationalist Qasim Amin (1863–1908), whose groundbreaking treatise Tahrir al-Mar’a (The Liberation of Women, first published in 1899) and its book-form addendum al-Marʾa al-Jadida (The New Woman, 1900) advocated female emancipation and national advancement and underscored the essential role of education in achieving it:

Hence, if Egyptians want to reform their current situation, they must begin with the roots of reform. They must believe that there is no hope that they will become a vibrant community, one that can play an important role alongside the developed countries, with a place in the world of human civilization, until their homes and families become a proper environment for providing men with the characteristics upon which success in the world depends. And there is no hope that Egyptian homes become that proper environment unless women are educated and unless they participate alongside men in their thoughts, hopes and pains, even if they do not participate in all their activities. (Amin, 2002, p. 66)

Accordingly, within the broader framework of this fin-de-siècle movement, a transnational cultural phenomenon marked by women’s increased visibility in the public sphere; life writings by Egyptian female authors of the time not only documented individual careers but also contributed to the evolving archetype of modern Egypt and modern womanhood.

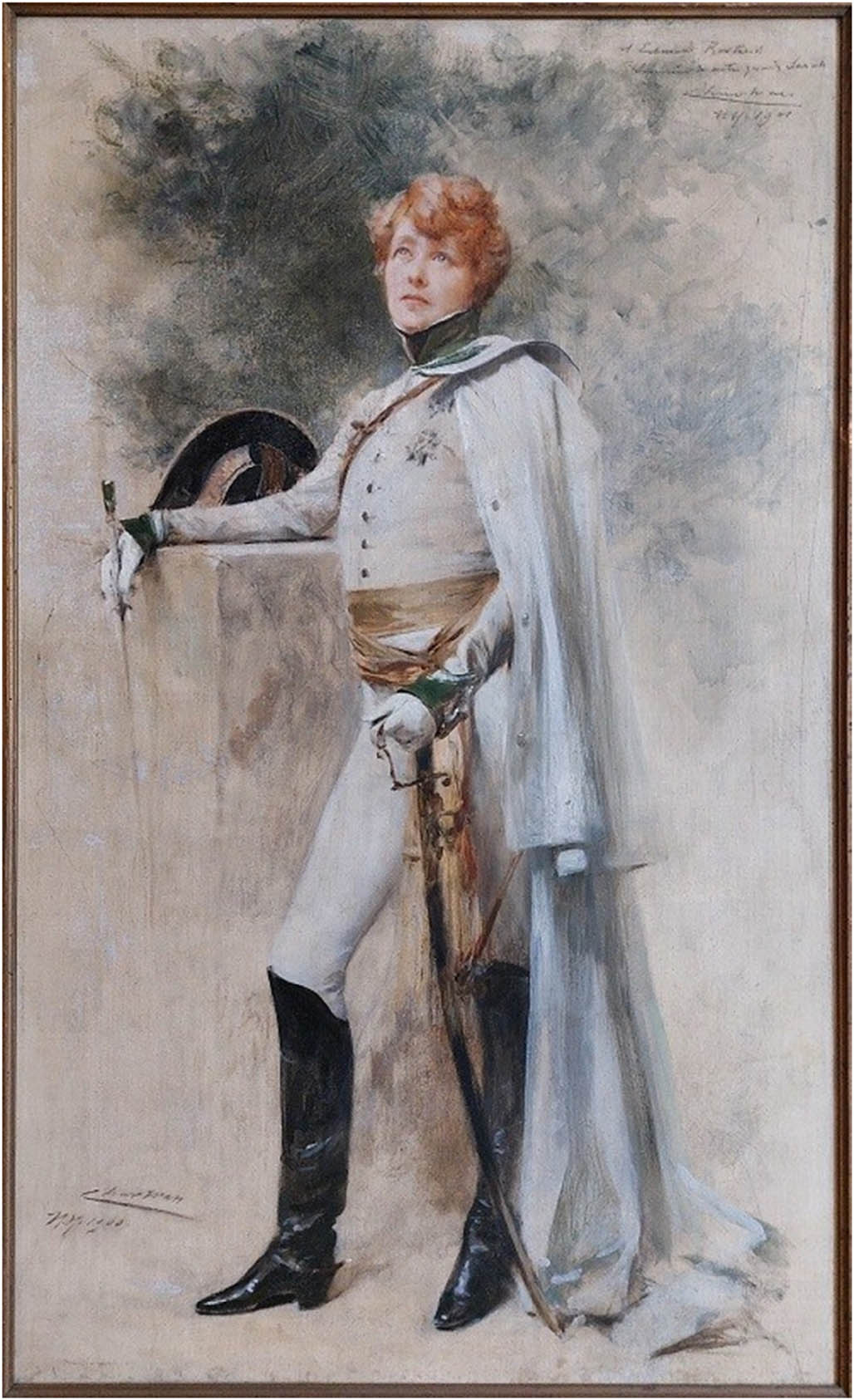

For both Sarah Bernhardt and Fatima Rushdi, theatre became a crucial site where the boundaries of gender, identity, and cultural belonging were questioned and reimagined. Their decision to cross-dress onstage, playing figures like Hamlet and Napoleon II, was not merely artistic but symbolic: an embodied critique of the roles women were expected to inhabit offstage. To illustrate, Bernhardt’s portrayal of Hamlet in 1899 was groundbreaking, as she was among the first women to take on this iconic male role and that of Napoleon was highly praised by her audiences and the press. The following first portrait (Figure 1) likely by Theobald Chartran, a frequent portraitist of Bernhardt, captures her in full regalia in the role of Napoleon II, the Duke of Reichstadt, wearing a white military uniform, complete with a long white cape, black boots, and sword, emblems of nobility and masculine military power, in an upright and commanding posture, with her hand resting confidently on a pedestal, eyes gazing upward with a dreamy and noble expression. Although Bernhardt does not explicitly pinpoint this role in her memoirs, she speaks of the Prince with admiration on the few occasions she recounts meeting him, portraying him as a man of great complexity and a richly layered personality. “The conversation of this man was brilliant, earnest, and witty; he laced his speeches and retorts with somewhat coarse expressions, yet everything he said was both engaging and enlightening” (Bernhardt, 1907b, p. 165). It is not surprising that Bernhardt embraced this role in Edmond Rostand’s play, which follows the Prince as he emigrates to Austria after the fall of the Empire – a trajectory marked by decline yet underscored by a persistent desire to maintain stature amidst the disintegration of a once-powerful kingdom. The second classic role played by Bernhardt is the character of Lorenzaccio, in the play by Alfred de Musset, which is based on Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449–1492), the most powerful of the Medicis, who ruled the city-state of Florence. In the play, Lorenzaccio struggles desperately to save Florence, which had grown rich during his reign, from the grip of a power-hungry conqueror. Figure 2 is a portrait by Alphonse Mucha, who represents this tyranny by a dragon menacing the city’s coat of arms and portrays Lorenzaccio pondering the course of his action. Sarah Bernhardt, never afraid to tackle a male role, made Lorenzaccio into the classic roles of her repertoire. By portraying such male historical figures, she subverted conventional gender norms, showcasing the performative nature of both gender and identity. In broader terms, these paintings are not just records of theatrical moments, but artifacts of Bernhardt’s self-fashioning as an icon of the fin-de-siècle: bold, androgynous, charismatic, and always in command of her public image.

Sarah Bernhardt in the title role of the play by Edmond Rostrand, “L’Aiglon”, by Theobald Chartran, © Villa Arnaga, Musée Edmond Rostand, Cambo-les-Bains (Credit Napoleon.org).

Sarah Bernhardt playing the character of Lorenzaccio, in the play by Alfred de Musset, by Alphonse Mucha in 1986 (Credit Mucha Museum).

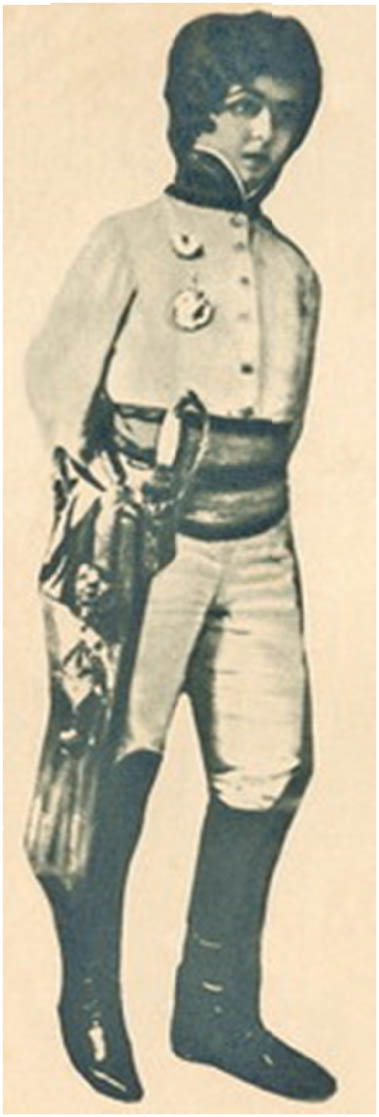

Similarly, Rushdi enjoyed taking on male roles, such as that of Mark Antony in an Egyptian version of Julius Caesar in 1928, as well as the roles of Tosca and Salambo. The following figure (Figure 3) shows her portrait in the same role played by her counterpart Bernhardt: Napoleon II in L’Aiglon.

Fatima Rushdi for the role of Napoleon II in L’Aiglon (Credit: Bibliotheca Alexandrina).

Through roles such as these, she became known as Sara Birnar al-Sharq (“Sarah Bernhardt of the East”) as well as the “Prima Donna of the East”. In an interview with her that was published in the famous Cairene Al-Kawakib magazine under the title “Uhib adwar al-rijal” (“I Like Men’s Roles”) (originally published in Arabic in February 1951), Fatima Rushdi explicitly expresses her preference to play male roles by stating that “[when] all is said and done, an actress can take it upon herself to render the male character more and better than the male portrayed, to give a performance less flat and more fulfilled than that given by a man. And herein lies the beauty of a feminine expression of the male, and the splendor of her creation” (1951). Indeed, Rushdi boldly asserts that a woman – an actress – can master male roles not merely adequately, but surpassingly, thus reclaiming creative mastery for women in a domain long considered the preserve of men: the portrayal of male power, complexity, and identity. The use of the term “creation” (or the “natural power of [women] art” in the original) frames performance not as mimicry, but as an act of “naturally powerful” artistic generation, countering traditional patriarchal logic, which often privileges male authorship, male experience, and male quintessence. For both women, these performances, reinforced by their autobiographical writings, constructed them as New Women not just in their societies, but in the broader history of gendered self-fashioning.

Both Rushdi and Bernhardt approached autobiography as a form of strategic self-fashioning, yet their narrative modes reflect distinct cultural, temporal, and ideological concerns. In her memoir Ma Double Vie [My Double Life] (1907), Sarah Bernhardt merges memory with spectacle, crafting an autobiography that is as much a performance as any she gave on stage. Her narrative style is flamboyant, fragmented, and unapologetically dramatic, often blurring the boundaries between fact and theatrical embellishment. She states: “When the curtain rose, slowly, I thought I might faint. It was, indeed, the very curtain of my life that was rising” (Bernhardt, 1907a, p. 73) (my translation). This deliberate theatricality is central to her self-representation: Bernhardt fashions herself not as a passive subject of fame but as its author, mastering both the stage and the page. Notably, her descriptions of playing male roles, such as Hamlet and Napoleon II, are not defensive but celebratory. She presents these performances as expressions of artistic freedom and intellectual equality, suggesting that gender is not a limitation but a theatrical tool to be wielded. Despite a clear coolness on the part of her audience for “the public never accepted her turning to cross-dress roles as one of her endearing quirks,” Bernhardt persisted in her endeavor of male roles as many more followed throughout her career (Berlanstein, 1996, p. 348). In her treatise on acting, she includes a chapter titled “Why I Have Played Male Roles” in which she confesses her admiration of “male brains,” more interesting to perform (1923, p. 137). More specifically, Bernhardt identifies strongly with the “Hamlet” roles and declares them to be her finest parts insofar as she emphasizes the psychological complexity of the variations of such character, aligning herself with Shakespearean depth rather than mere novelty. “No female character has opened up such a wide field for the exploration of human feelings and pain as Hamlet. […] I can say that I have had the rare, and I think unique, opportunity to play three Hamlets: Shakespeare’s black Hamlet, Rostand’s white Hamlet, L’Aiglon, and Alfred de Musset’s Florentine Hamlet, Lorenzaccio” (1923, pp. 137–141).

Bernhardt’s Ma Double Vie exudes theatrical flair and deliberate mythmaking. Her cosmopolitan identity – fluent in multiple languages, adored across Europe, the Americas, and worldwide even in the Middle East, notably in Egypt as she first performed in Cairo Opera House during the winter of 1888–1889, and returned two decades later, in 1908, where she once again witnessed firsthand the enthusiasm and fervor of the Egyptian audience (Cormack, 2021) – is reflected in a memoir that resists national anchoring, presenting her life as a transgressive, borderless journey. As she narrates/fictionalizes the different stages of her life travelling around from one place to another, she constructs a persona that transcends not only nationality, gender, and genre, but also surpasses all kinds of challenges. Indeed, she recounts moments of public scandal, physical suffering, and professional triumph with a tone that veers between irony and grandeur, reinforcing her mythic status as “Divine Sarah.” For example, despite her rather thin curve-less body described by Chili, one of the theatre’s managers, as “a wisp of a figure for society’s elite, so slight, not even a morsel within” (1907a, p. 159) (my translation), Bernhardt would take on all kinds of roles in her beginnings in L’Odeon theater, even those typically written for female performers meant for pleasure and entertainment in plays such as Le Jeu de l’amour et du hasard (The Game of Love and Chance). She declares “I was not made for Marivaux, who demands a flair for coquetry and preciosity – qualities that were not mine then, and are still not mine. Besides, I was a little too slender” (1907a, p. 159) (my translation). Yet, she was determined to take on such challenges and make the best use of her other qualities, mainly her sweet, enchanting voice. Her efforts are rewarded as she describes the glorious aftermath: “The audience, captivated by the softness of my voice and the crystalline purity of its tone, called for an encore of the spoken chorus, and three rounds of applause rewarded me” (1907a, p. 161) (my translation). The intention is not solely for readers to acknowledge her perseverance, but to craft a figure imbued with an air of the extraordinary, one that rises above mere endurance to embody something almost divine. As her memoir oscillates between fact and fiction, it underscores her belief in identity as performance, a view that aligns with her career of shape-shifting onstage. Her narrating voice is confident, ironic, and unapologetically self-assured, embracing contradiction as part of her public mystique. Through her memoir, Bernhardt articulates a version of the New Woman rooted in performance, cosmopolitanism, and flagrant self-possession, challenging the gendered norms of her time, not through overt polemic, but through the seductive power of narrative control.

Yet, one of the most striking features of Bernhardt’s Ma Double Vie is its deliberate mythmaking, which often glosses over the harsher realities of her childhood and early struggles. Born to a Dutch Jewish courtesan who largely abandoned her, Bernhardt spent her formative years in convent schools and foster care, oscillating between neglect and precarious patronage. Yet her memoirs rarely dwell on these conditions of vulnerability. Instead, she constructs narratives of destiny, in which hardship is transfigured into theatrical opportunity. As Marcus (1994) notes, women’s autobiographies of the period often employed strategies of “apology or evasion” when addressing disreputable aspects of their past, reflecting the cultural suspicion directed at female self-exposure. Bernhardt’s memoir exemplifies this tendency: her silences around her mother’s profession, her illegitimacy, and her economic precarity reveal a calculated attempt to control the terms of her visibility. By transforming herself into a heroine of spectacle, she shields her readers from the stigmas attached to actresses, a group often associated with sexual availability and moral laxity (Berlanstein, 1996). In this way, the omissions in her memoirs are as performative as the flamboyant episodes she recounts: they underscore the precarious balance between asserting autonomy and defending respectability in a cultural context that policed women’s public presence.

These silences can be read as integral to Bernhardt’s strategy of self-authoring. Rather than presenting her life as a narrative of deprivation, she retroactively casts herself as an almost predestined figure, a woman born to command the stage and transcend circumstance. In doing so, she enacts what Smith and Watson (2016) call the “performative function” of autobiography: identity is not merely recalled but shaped through narrative omissions and emphases. Bernhardt’s refusal to dwell on abandonment or poverty was not only an act of concealment but also a means of transforming vulnerability into authority. Her romanticized drama of the self, complete with moments of irony, wit, and theatrical exaggeration, allowed her to overwrite the stigmatized subject position of the courtesan’s daughter with that of the “Divine Sarah,” the global icon who bent audiences to her will. At the same time, these omissions reveal the gendered pressures of her context: to confess too much risked reinforcing patriarchal suspicions about actresses, but to remain entirely silent about hardship risked undermining the narrative of triumph. The result is a contradictory text, where empowerment is staged through performance, but fragility lingers in what is unsaid. Reading these silences alongside her overt self-dramatization underscores how Bernhardt’s life writing functioned as a dual act: a claim to power and a shield against marginalization, both essential to her negotiation of authority as a woman artist at the fin-de-siècle.

Writing decades later and within a colonially imbued Egyptian context, Rushdi adopts a more documentary tone in her memoirs published in four sets under the titles Kifahi fi-l-Masrah wa-l-Sinima (My Struggle in Theater and Cinema) (1971), Fatima Rushdi bayn al-Hubb wa-l-Fann (Fatima Rushdi between Love and Art) (1971), and Mudhakkirat Fatima Rushdi: Sara Birnar al-Sharq (Memoir of Fatima Rushdi: Sarah Bernhardt of the East) (1990, could originally be traced back to the 1960s) edited by Muhammad Rif’at. Her narrative is shaped by both nationalist ideals and a personal quest for modernity; it traces her journey from illiteracy to cultural leadership, from the margins of respectability to the center of Egypt’s artistic revival. While Bernhardt revels in theatrical exaggeration, Rushdi’s self-presentation is more grounded, aimed at legitimizing her transgressive roles as both actress and director within a society that was still negotiating women’s place in public life. Yet despite their differences, both women use life writing as a means of narrative control, crafting public identities that challenge the binaries of masculine/feminine, East/West, and self/other.

In Al-Hubb wa-l-Fann, Fatima Rushdi crafts a narrative of self-emergence that intertwines personal struggle with national aspiration. While she uses a realistic style, Rushdi presents her life as a metaphor for Egypt’s own pursuit of cultural modernity, as it shows when she recounts her move from Alexandria to Cairo “where the theatrical atmosphere and artistic life stood poised, ready to launch into vast and distant horizons” (Rif‘at, 1990, p. 16) (my translation). Her tone is candid yet calculated, drawing attention to the obstacles she faced not only as a woman but as an artist entering a field considered disreputable at the time. One of the most striking aspects of her narrative is the way she frames her illiteracy, not as a source of shame, but as a symbol of determination and transformation. By recounting how she was taught to read and write to elevate her theatrical craft, Rushdi positions herself as both student and innovator of Egyptian modernity while cementing her sisterhood/mentorship bond with world-class actors and actresses, notably Sarah Bernhardt, her artistic namesake.[2]

Furthermore, her accounts of playing male roles, most notably Hamlet and Napoleon II, serve as moments of narrative rupture, where gender boundaries are blurred and reclaimed.[3] In describing these roles, she emphasizes not just the technical difficulty, but the emotional and intellectual depth they required, implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) arguing for the legitimacy of her authority as an actress, director, and cultural figure. In other words, in her autobiographical narratives, she carves out something like an equation in which she incorporates dedication, hard work, perseverance, and extraordinary talent to get an output she succinctly sums up in her own words: “I have become the prima donna of Ramsis theatrical [troupe] for three years, I have become the greatest actress of the East, I have become the queen of hearts, the hearts of the audiences who loved me in Egypt and in all the Arab countries I have been to” (1971a, p. 60, my translation). Her portrayal of herself as a leader in the national theatre movement – managing a troupe, producing plays, and touring internationally – further challenges the domestic roles traditionally reserved for women. In this way, Rushdi’s autobiography functions as a political and aesthetic act: a self-written testimony of gender defiance, artistic ambition, and Egyptian womanhood in the early twentieth century.

While Rushdi and Bernhardt emerge from vastly different cultural and historical contexts, their autobiographical narratives reveal strikingly similar strategies of self-construction through performance. Both women use life writing to assert control over their public image, leveraging the authority of the autobiographical “I” to validate lives lived outside normative gender roles. Their portrayals of cross-gender theatrical roles – Hamlet and Napoleon II – function not only as artistic milestones but as symbolic acts of gender transgression, illustrating how the stage became a site of identity negotiation. Yet the tone and purpose of their narratives diverge meaningfully. Bernhardt’s Ma Double Vie revels in theatrical spectacle and mythmaking; she presents herself as a global icon whose defiance of gender norms is woven seamlessly into a cosmopolitan narrative of fame and excess. In effect, her sobriquet “the godmother of modern celebrity culture” (Marcus, 2020, p. 14) is well earned. Rushdi’s Al-Hubb wal-Fann (and her other memoir sets, especially her 1971 Kifahi fi al-Masrah wa-al-Sinima (My Struggle in Theater and Cinema), in contrast, are anchored in the national and the didactic, offering her life as both a personal testimony and a blueprint for the modern Egyptian (New) Woman. Her account foregrounds education, discipline, and national service, aligning her artistic ambition with the project of Egyptian cultural renewal. Such combination of the “personal” and the “political,” in a different and richer sense of the word, is evidently manifest in the first pages of her set of memoirs edited by Muhammad Rif’at when she pinpoints, in the course of her recounts of her late father, that she inherited from him “the desire to rely on myself, to adopt self-reliance as a guiding principle, and to step into the vast arena – the arena of success and failure, of struggle and perseverance, of individual and collective responsibility toward society – the very arena that Egyptians at the time often left to foreigners: the field of private enterprises” (Rif‘at, 1990, p. 10). Thus, while both autobiographies stage the self in ways that defy traditional femininity, they do so through distinct rhetorical strategies – Bernhardt through flamboyant cosmopolitanism and performative myth, and Rushdi through grounded realism and national consciousness. Together, they reveal the flexible contours of the New Woman archetype, shaped as much by geography and politics as by individual will.

Nonetheless, Rushdi’s memoirs similarly reflect the tension between narration and omission, particularly in her treatment of childhood, poverty, and social stigma. Rushdi lost her parents early, grew up in conditions of financial insecurity, and initially entered the theatrical world as an illiterate girl, dependent on others to teach her the skills necessary for her craft. While she acknowledges these facts in passing, she does not dwell on their emotional or social weight. Instead, she reframes them as obstacles overcome through determination, emphasizing perseverance rather than vulnerability. This narrative strategy resonates with what Kholoussi (2019) identifies as the contentiousness of Arab women’s autobiographical practice: female self-writing is often constrained by cultural expectations of modesty and propriety, leading to careful negotiation of what can and cannot be disclosed. Rushdi’s memoirs demonstrate this tension. By moving swiftly from orphanhood to theatrical triumphs, she minimizes the stigma historically attached to women in the performing arts in Egypt, where actresses were often viewed with suspicion or outright hostility (Cormack, 2021). Her silences, then, are not mere absences but purposeful omissions, designed to craft a public persona of legitimacy, national service, and artistic excellence. In presenting herself as a leader of Egypt’s theatrical renaissance, Rushdi distances her image from the disreputable associations of her profession, claiming instead the role of cultural reformer and national icon.

The performative function of these silences becomes clear when Rushdi’s memoirs are read in light of Arab feminist thought. As El Saadawi argues, for Arab women to write is itself an act of rebellion against structures that demand silence (1999, p. 352). Yet rebellion does not always take the form of overt disclosure; it can also manifest in strategic silences that allow women to assert authority without exposing themselves to further vulnerability. In Rushdi’s case, the absence of detailed discussion of childhood trauma, intimate relationships, or the social condemnation she faced reflects both constraint and agency. Mikhail (2004) reminds us that Arab women writers have often had to negotiate between personal truth-telling and the cultural imperative to protect family honor and public reputation. Rushdi’s omissions illustrate precisely this negotiation: they allowed her to position herself as the “Prima Donna of the East,” a figure of respectability, while sidestepping narratives that might have reinforced patriarchal dismissal. At the same time, these silences reveal the contradictions of her self-fashioning project. Her insistence on national service and artistic ambition masks the vulnerabilities of class, gender, and profession, but those very gaps remind readers of the pressures shaping women’s voices in twentieth-century Egypt. Thus, her memoirs exemplify what Smith and Watson (2001) describe as the “productive tension” of life writing: a genre where what is unsaid is as revealing as what is spoken. In Rushdi’s case, silence itself becomes a performative gesture, a way to contest marginalization while still claiming space in Egypt’s cultural and political history.

2 Navigating the Regional and Transnational Contours of “New Womanhood”

Women’s participation in public discourse and cultural production was deeply tied to national identity and reform. Debates about women’s roles were central to broader struggles over cultural authenticity, national identity, and modernization (Ahmed, 1992); it was evident that Egyptian women progressively “[claimed] public space” (Badran, 1995, p. 47). Based on women’s memoirs, oral histories, correspondence, essays and speeches, and on the records of the Egyptian Feminist Union, Badran (1995) argues for “women’s agency and their insistence upon empowerment – of themselves, their families and their nation” (p. 3), and their gradual journey to change their community from within. Assuming this agency subverted and refigured the conventional patriarchal order and led the way to the rise of Egyptian feminism, thus threatening the hitherto stable conviction that feminism is Western. Fatima Rushdi’s life writings and theatrical journey can be approached and read within this historical and ideological framework, where the self becomes a site of both gendered resistance and national symbolism.

The memoirs written by Rushdi, qualified as a pioneering figure in Egyptian theater, articulate a complex negotiation between individual ambition and collective expectation, between art and resistance. When describing how she chose some of her roles around the time of the Egyptian 1919 Revolution, she narrates,

The reader will notice that the closing lines of the taqtuqas (light popular songs) exalt the Egyptian people and celebrate the honor of belonging to Egypt. This was no mere coincidence—it was a phenomenon born of the national consciousness awakened by the 1919 Revolution, a flame that continued to burn brightly in its aftermath. Every song and monologue became a channel for Egypt’s voice, a call to arms through art, urging diligence in the struggle […] In this way, I took part in the 1919 Revolution—I was not separate from it, just as art itself—whether the art of theatre or of music—was never detached from the cause. (Rif‘at, 1990, p. 21/22) (my translation)

Later, she became increasingly politically active, particularly in her support for the liberation movements in the Maghreb region in northwest Africa. She recounts a pivotal encounter with a Tunisian political leader who was living in Cairo at the time. This leader entrusted her with a mission to leverage her theatrical works for the dissemination of political speeches aimed at various Arab leaders in Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. He explicitly stated: “You have always played a role in spreading Arab culture through your art. Now the time has come for you to serve the Arab cause with that same art – to wield it as a weapon and join, through it, the Arab Liberation Army in North Africa” (1990, pp. 86–87) (my translation). Following these perilous missions, she encountered significant opposition from the French colonial authorities, who feared her growing popular support, particularly in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. In her memoir Kifahi fi al-Masrah wa al-Sinima, Rushdi recounts a striking encounter with a French officer, on one of her tours, who bluntly informed her that her forthcoming performances would be cancelled due to the unrest they would incite. Although she asserted to him that the plays she performed were originally French and had been regularly staged in France without issue, the officer alleged that, within the volatile political climate of the Maghreb, these same plays acquire a subversive dimension and need to be stopped immediately (1971b). Consequently, she was forced to leave North Africa after much pressure was imposed by the French colonial regime. It is through such engagement that Fatima Rushdi, both woman and artist, can be seen as an iconic figure of the Egyptian/Arab struggle towards liberation from the shackles of the French (and British) colonial powers.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Egyptian resistance unfolded not only against European colonial domination but also against entrenched traditional structures that hindered progress from within. Egypt’s trajectory toward modernity began in the private sphere, behind closed doors, where domestic life slowly gave way to a broader social awakening. It was within these intimate spaces that the earliest challenges to patriarchy emerged, as girls and women began to step beyond the confines of their familial “nests”, seeking education as a gateway to professional opportunity and public presence. In her memoirs, Fatima Rushdi refers to Qasim Amin’s Tahrir al- mar’a (The Liberation of Women) (1899) as the turning point in Egyptian history for women which marked breaking with traditional female roles that consisted of being “merely a tool for reproduction and service in the home, and it is not appropriate for her to do any other work” (Rif‘at, 1990, p. 9) (my translation). Read within this socio-historical context, Rushdi’s appearance on stage – both literally and symbolically – constitutes a powerful disruption of normative gender roles, introducing the female body and voice into a cultural domain long dominated by men.

Her theatrical work embodied a radical performative rupture from the conventions of domestic containment, as her presence on stage reconfigured the boundaries between private femininity and public expression. By stepping into the spotlight, Rushdi claimed a space traditionally denied to women, transforming the theatre into a platform for socio-political articulation. Her performances did not merely represent characters, they enacted a “performing self”, to borrow Erving Goffman’s term coined in his foundational sociological work The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959), wherein identity was constructed and asserted through embodied gesture and public voice. As Davis and Postlewait (2003) contend, “theatricality is the performative display of self as a representational strategy” (p. 1), and in this sense, Rushdi’s stagecraft became a powerful mode of cultural intervention, allowing her to rewrite the narrative of womanhood in early twentieth-century Egypt. Indeed, at a moment when Egyptian identity was actively reshaped in response to colonial pressures and nationalist aspirations, Rushdi’s narrative encapsulates the broader cultural tension between inherited tradition and emergent modernity. Her unwavering pursuit of artistic and professional autonomy positions her not only as an early feminist figure but as a cultural agent who helped redefine the contours of modern Arab womanhood. Reflecting on her journey, Rushdi underscores the formidable challenges she faced: “I did not find my path to my goals paved before me. I was a poor, orphaned girl, unable to read or write, who had only just set foot on the first rung of the ladder – so how could I hope to ascend to the summit ? What qualifications did I possess? What resources, what tools for success were at my disposal?” (Rif‘at, 1990, p. 32). (my translation). These lines serve not only as a personal testament to Rushdi’s feminist engagement, but also as a potent metaphor for Egypt’s own national ascent, from the margins of illiteracy to the ideals of enlightenment, from the weight of tradition to the promises of modernity.

Later in her career, Fatima Rushdi transitioned into the role of a cultural producer by founding her theatrical company, where she both performed and produced her own plays. Despite the financial challenges of this venture, Rushdi persisted in her commitment to theater, driven by a deep passion for the art form. However, as cinema gradually supplanted theatre in popularity and audience tastes shifted toward films, Rushdi’s resilience enabled her to adapt to the changing cultural landscape. She not only participated in the rising film industry, appearing in numerous commercially successful movies, but she also consistently returned to the stage, driven by a desire to leave a lasting dramatic legacy. Through her dynamic and multifaceted career, Rushdi emerged as a cultural beacon, embodying the ideals of New Womanhood and symbolizing Egypt’s transitional position between the tradition of theatre and the modernity of cinema.

On another continent, Sarah Bernhardt’s France was at a pivotal juncture, undergoing profound transformations in its socio-cultural, political, and artistic landscape. In fact, the first decades of the twentieth century in France were marked by intense cultural ferment, as emerging ideas, artistic movements, and shifting social dynamics reshaped national identity. The tension between tradition and modernity, political conservatism and artistic innovation, wove a complex socio-cultural fabric, characterized by both an optimistic embrace of progress and a pervasive anxiety about the future. These contradictions were reflected in the lives of cultural figures like Bernhardt, whose career both mirrored and influenced the evolving currents of French society. Her autobiographical narrative presents a self-fashioned identity that is deeply rooted in individualism and artistic mythmaking, positioning her as both an icon of French cultural modernity and a global celebrity. In her memoirs and public persona, Bernhardt crafted an image of herself as an autonomous artist, defying the conventions of her time and shaping a personal mythology that blurred the lines between reality and performance.

Bernhardt’s engagement with French cultural modernity was marked by a conscious embrace of innovation and a challenge to traditional gender roles. On stage, she consistently defied established conventions, crafting performances that reflected her distinctive dramaturgical vision. This departure from the norm drew criticism from contemporaries; for instance, in his review of Bernhardt’s portrayal of Adrienne Lecouvreur in Le Figaro, the prominent critic Auguste Vitu reproached her for straying from the precedent set by Rachel (Bernhardt, 1907b, p. 152). In addition, unlike Virginie Déjazet – arguably the most celebrated travesti performer of the nineteenth century, whose roles eventually came to be seen as formulaic and reliant on clichéd masquerade – Bernhardt’s cross-dressing performances offered a more nuanced interrogation of gender. Déjazet’s characters typically revolved around a linear quest for manhood, reinforcing a one-sex model of youth and maturity. In plays such as Vert-Vert (Green-Green) (1832), Les Premières Armes de Richelieu (Richelieu’s Early Exploits) (1839), and Prés Saint-Gervais (The Meadows of Saint-Gervais) (1862), youthful ambiguity was resolved through characters’ progression into socially acceptable masculine adulthood, thereby upholding gender norms. Bernhardt’s performances, by contrast, emerged during a period of increasing interest in the complexity of gender, spurred by developments in medical and psychological fields such as sexual psychology. Her travesti roles became a medium through which both personal and national anxieties about shifting gender paradigms were explored. Fin-de-siècle France was already grappling with a crisis of masculine identity following its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (July 1870–January 1871), a crisis that would later be compounded by a post-war reconfiguration of feminine identity (Roberts, 1993). Within this context of evolving gender discourse, France rose as “the birthplace of fin-de-siècle generational thinking and a leader in psychological studies of adolescents” (Berlanstein, 1996, p. 360), with Bernhardt emerging as both a participant in and an idol of this national debate.

Ultimately, Bernhardt’s embodiment of the “New Woman” is notable for its cosmopolitan scope, as she transcended national boundaries, positioning herself as a transgressive and globally influential figure rather than a mere symbol of French national identity. Her performances, both on and off the stage, emphasize autonomy, agency, and the ability to transcend traditional social roles, redefining the limits of femininity and artistic expression. As she justifies her decision to travel to America, she simply declares, “but I felt the need for different air, a greater space, another sky” (Bernhardt, 1907b, p. 167) (my translation). In this sense, Bernhardt’s theatrical presence becomes a vehicle for both personal and collective reinvention, embodying the tensions of a rapidly changing world where the individual could assert agency through the performative self. This multi-layered persona, both impacting and impacted by the sociopolitical and cultural context, became a tool for constant self-definition and transformation, allowing Bernhardt to continuously challenge and redefine her own identity and the very idea of womanhood in the modern age.

Through their life writings, in which they stage themselves as pioneering New Women within their respective national contexts, Bernhardt and Rushdi challenge and destabilize Western/non-Western feminism binarism. Both women’s texts operate as cultural artifacts that reflect and negotiate national ideologies. Viewed through the lens of transnational feminism, their autobiographical narratives position them as feminist activists engaged in broader dialogues of gender and agency across borders. In their theorization of transnational feminism – what they term “transnational feminist practices” – Grewal and Kaplan (1994) emphasize the solidarities and activism among feminists across national divides. While their focus is largely on the American context, their framework can be extended to encompass the current study, particularly given their assertion that “‘local-global’ spatial constructs erased the constitutive connections across national borders and […] transnational forces were critical to making gender, albeit in different ways because of different hegemonic arrangements of power and specific histories of colonialism and imperialism” (Grewal, 2023, p. 95). To zoom in the memoirs written/performed by Bernhardt and Rushdi within the broader context of New Woman movement marks the success in “crossing the First World/Third World divide” to borrow Robert Carr’s phrase (1994, p. 153) and foregrounding the shared, yet contextually distinct, feminist articulations of Bernhardt and Rushdi. In fact, Rushdi’s journey to France[4] and Bernhardt’s celebrated visits to Egypt serve as powerful symbols of the transnational outreach that shaped both women’s artistic and personal identities. These crossings were not merely geographical but symbolic of a broader cultural dialogue that transcended borders, linking their performative womanhood to global currents of modernity, aspiration, and resistance. Within the framework of transnational feminism – which understands gender inequality as shaped by intersecting global forces such as colonial histories, economic hierarchies, and cultural hegemonies – their respective travels foreground an intricate web of shared struggles and divergent realities. While Bernhardt navigated the privileges and limitations of European stardom, Rushdi contended with the constraints of postcolonial patriarchy and nationalist expectations. Yet, both figures illuminate a mode of feminist solidarity that does not erase difference but instead honors it – demonstrating how agency, self-representation, and the will to perform the self can resonate across continents, even as they are refracted through region-specific challenges. Their journeys, therefore, map out the expansive and layered contours of New Womanhood as a dynamic, border-crossing phenomenon.

3 Conclusion: Autobiographical Narratives as Acts of Empowerment/Resistance

(Re-)reading the autobiographical writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt through the intersecting lenses of feminist theory, autobiographical studies, and performance theory enables a fresher take on their life narratives as powerful acts of self-definition and resistance. Following Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson’s conceptualization of life writing as performative acts that construct identity within cultural and ideological frameworks, both Rushdi and Bernhardt can be seen as using autobiography not merely to recount experience but to shape it, turning the act of writing into a stage for enacting modern womanhood.

Yet to grasp the full significance of their narratives, it is necessary to situate them within broader traditions of both Western and non-Western life writing. Arab feminist thinkers such as Nawal El Saadawi and Mona Mikhail, along with Samia Kholoussi’s critical interventions, have emphasized that women’s autobiographical practice in the Arab world is always fraught with risk, often perceived as transgressive in patriarchal contexts. Rushdi’s memoirs exemplify this tension: she writes as both a national icon and a cultural dissenter, challenging inherited boundaries of gender and authorship. Her insistence on self-representation resonates with El Saadawi’s claim that writing by women is itself a rebellious act, but it also extends beyond rebellion, embodying the struggle to align female self-fashioning with the broader project of Egyptian modernity.

Placed in dialogue with Bernhardt, whose flamboyant cosmopolitanism crafted a global stage for female autonomy, Rushdi’s life writing underscores how the New Woman archetype emerges differently across cultural and political terrains. Bernhardt staged herself as a transgressive celebrity whose identity was deliberately borderless; Rushdi staged herself as a national figure who simultaneously carried the weight of collective liberation. Both disrupt the binaries of East/West and tradition/modernity by mobilizing autobiography as performance, thereby transforming the genre into a space of feminist agency.

Their memoirs thus expand the scope of life writing beyond Eurocentric paradigms. They reveal how women performers used the written self as a means of negotiating modernity, gender, and power in radically different yet interconnected contexts. In doing so, they demonstrate that autobiographical writing – whether in Paris or Cairo – operated as a political act, a form of cultural intervention, and a strategy for reimagining womanhood on their own terms. The legacies of Rushdi and Bernhardt remind us that the study of life writing must attend to both Western and non-Western traditions if it is to capture the richness of feminist self-fashioning across borders.

Acknowledgments

The authors used the publicly available version of ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2025) solely to improve the phrasing and clarity of the manuscript. No content was generated by AI, and all intellectual contributions, analysis, and interpretations are entirely the authors’ own.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. LL and AM developed the theoretical framework, conducted the primary textual analyses, and prepared the manuscript. LL contributed to the critical contextualization and integrated the comparative perspectives, while AM collaborated in the revision process and refined the manuscript for clarity and coherence.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors confirm that there are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

Ahmed, L. (1992). Women and gender in Islam: Historical roots of a modern debate. Yale University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Amin, Q. (2002). The emancipation of woman and the new woman. In C. Kurzman, Modernist Islam: 1840–1940 (pp. 61–69). Oxford University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Badran, M. (1995). Feminists, Islam, and nation: Gender and the making of modern Egypt. Princenton University Press.10.1515/9781400821433Search in Google Scholar

Berlanstein, L. R. (1996). Breeches and breaches: Cross-dress theater and the culture of gender ambiguity in modern France. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 38(2), 338–369.10.1017/S0010417500020302Search in Google Scholar

Bernhardt, S. (1907a). Ma double vie (Vol. 1). Bibliothèque Numérique Romande. Retrieved 2025, from https://ebooks-bnr.com/ebooks/pdf4/bernhardt_ma_double_vie_1.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Bernhardt, S. (1907b). Ma double vie (Vol. 2). Bibliothèque Numérique Romande. Retrieved from https://ebooks-bnr.com/ebooks/pdf4/bernhardt_ma_double_vie_2.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Bernhardt, S. (1923). Why I have played male parts. In The art of the theater (H. J. Stenning, Trans., pp. 137–141). The Bookman’s Shop.Search in Google Scholar

Carr, R. (1994). Crossing the first world/third world divides: Testimonial, transnational feminisms, and the postmodern condition. In G. Inderpal & C. Kaplan (Eds.), Scattered hegemonies postmodernity and transnational feminist practices (pp. 153–72). University of Minnesota.Search in Google Scholar

Civale, S. (2019). Romantic women s life writing: Reputation and afterlife. Manchester University Press.10.7765/9781526101273Search in Google Scholar

Cormack, R. (2021). Midnight in Cairo: The female stars of Egypt’s roaring ‘20s. Saqi Books. ISBN: 978-1-324-02193-3.Search in Google Scholar

Davis, T. C., & Postlewait, T. (Eds.). (2003). Thetaricality. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/S0040557405210098.Search in Google Scholar

El Saadawi, N. (1999). A daughter of Isis: The autobiography of Nawal El Saadawi. (S. Hetata, Trans.) Zed Books.Search in Google Scholar

Grewal, I., & Kaplan, C. (Eds.). (1994). Scattered hegemonies: Postmodernity and transnational feminist practices. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.Search in Google Scholar

Grewal, I. (2023). Theories of discrimination: Transnational feminism. In A. Deshpande (Eds.), Handbook on economics of discrimination and affirmative action (pp. 85–104). Springer Nature. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-4166-5.Search in Google Scholar

Gürpınar, D. (2012). The politics of memoir-writing and memoir-publishing in twentieth century Turkey. The International Journal of Turkish Studies, 21(2), 537–557.10.1080/14683849.2012.717443Search in Google Scholar

Heilmann, A. (2000). New woman fiction: Women writing first-wave feminism. Palgrave Macmillan UK.10.1057/9780230288355Search in Google Scholar

Kholoussi, S. (2019). Arab women’s autobiography: A contentious practice that elicits disapprobation, jeering, curiosity and/or … furor. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 6(7), 287–309. doi: 10.14738/assrj.67.6614.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, T-M-L. (2007). Rethinking the personal and the political: Feminist activism and civic engagement. Hypatia, 22(4), 163–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4640110.10.1111/j.1527-2001.2007.tb01326.xSearch in Google Scholar

Louati, L. (2022). Sexsation and the neo-new woman in Sarah Waters’s Fingersmith (2002). Études britanniques contemporaines [Online], 62. http://journals.openedition.org/ebc/11819. doi: 10.4000/ebc.11819.Search in Google Scholar

Marcus, L. (1994). Auto/biographical discourses: Theory, criticism, practice. Manchester University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Marcus, S. (2020). The Drama of celebrity. Princeton University Press.10.1515/9780691189789Search in Google Scholar

Mikhail, M. (2004). Seen and heard: A century of arab women in literature and culture. Interlink Books.Search in Google Scholar

Rabinovitch-Fox, E. (2017). New women in early 20th-century America. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.427.Search in Google Scholar

Rif‘at, M. e. (1990). Mudhakkirat Fatima Rushdi: Sara Birnar al-Sharq. Dar al-Thaqafa. Retrieved 2025.Search in Google Scholar

Roberts, M.-L. (1993). Samson and Delilah revisited: The politics of women’s fashion in 1920s France. American Historical Review, 98(3), 657–684.10.1086/ahr/98.3.657Search in Google Scholar

Rushdi, F. (1951, February). I like men’s roles. El Kawakeb (25). Retrieved April 13, 2025, from https://www.bibalex.org/alexcinema/articles/Fatma_Roushdi.html.Search in Google Scholar

Rushdi, F. (1971a). Fatima Rushdi bayn al-hubb wal-fann. Sa’di wa Shandi Press.Search in Google Scholar

Rushdi, F. (1971b). Kifahi fi al-masrah wa al-sinima. Dar al-Maʿarif.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, S. A., & Watson, J. A. (2016). Life writing in the long run: A smith and watson autobiography studies reader. Michigan Publishing. doi: 10.3998/mpub.9739969.Search in Google Scholar

Smith, S., & Watson, J. (2001). Reading autobiography: A guide for interpreting life narratives. University of Minnesota Press.10.5749/minnesota/9780816669851.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic

- “Geographical Imaginaries”: A Three-Decade Literature Review of Usage and Applications Across Academic Contexts

- Colonial Mimicry, Modernist Experimentation, and the Hegelian Dialectics of Empire: A Postcolonial Deconstructive Reading of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness

- Aesthetic Hybridization in the Creation of Contemporary Batik Motif Design

- Echoes of Past and Voices of Present: Intergenerational Trauma and Collective Memory in “The Fortune Men”

- Staging the Self: Life-Writings of Fatima Rushdi and Sarah Bernhardt as Emblems of Fin-de-Siècle New Womanhood