Abstract

This study investigated the use of persuasive strategies in argumentative academic writing by Arabic–English bilingual English as a foreign language (EFL) learners in their second language (English, L2), compared to their first language (Arabic, L1) and English L1 writing by native speakers of English. This tripartite comparison between bilinguals’ L1 and L2 writing and English native speakers’ writing is a key contribution of the study since it allows us to consider how persuasion is employed in the participants’ L2 in light of two baselines of comparisons. To this end, 60 Saudi undergraduates wrote argumentative paragraphs in English and Arabic, and these paragraphs were compared against one another and also against English argumentative paragraphs by American undergraduates for the use of persuasive strategies. The findings revealed statistically significant differences in the use of persuasive strategies across the three groups of paragraphs. While the EFL learners tended to employ logos and pathos strategies more frequently in their L1 and L2 writing than English Native Speakers (NS), the NS, in turn, produced significantly more ethos strategies than the EFL learners. The differences were most noted in the use of logos strategies involving logical reasoning, pathos strategies – such as evaluative expressions and fostering collegiality – and ethos strategies, including demonstrating involvement, sharing personal perspectives, and modulating commitment to claims and community use. In addition, the results showed that increased English language proficiency had a limited effect on the use of persuasive strategies by EFL learners in their English writing.

1 Introduction

Undergraduate students need to master argumentative academic writing to meet the requirements of higher education (Ghanbari & Salari, 2022; Ozfidan & Mitchell 2020, 2022; Wu, 2006). The ability to construct and assess arguments in academic writing is recognized as a fundamental university objective (e.g., El Majidi et al., 2021; Pérez-Echeverría et al., 2016; Teng & Yue, 2023). To successfully navigate their university studies, students must be adept at discerning and analyzing arguments and crafting coherent and convincing arguments themselves. Despite the undeniable importance of argumentative academic writing as a skill, it poses a significant challenge for many university students (Altınmakas & Bayyurt, 2019; Divsar & Amirsoleimani, 2021; Saprina et al., 2020; Sundari & Febriyanti, 2021). This challenge can be attributed to students’ difficulties in effectively organizing their arguments (Bacha, 2010; Su et al., 2021; Wingate, 2012). Students are often provided with only basic instructions on argumentative academic writing and are expected to apply them independently without sufficient support (e.g., Ahmad et al., 2024; Bailey & Almusharraf, 2022). This lack of support may result from the absence of comprehensive models for persuasive strategies. The literature has shown that university teachers sometimes struggle with uncertainty over the requirements of argumentative writing (Casanave, 2004; Jacobs, 2005; Mutch, 2003; Wingate, 2012).

Constructing arguments in a second language (L2) presents additional challenges for students (e.g., Majidi et al., 2023; Yoon, 2021), a common scenario in universities where English is the medium of instruction in non-English-speaking countries. Students in these contexts often struggle due to their limited L2 proficiency. They also encounter difficulties with the different writing conventions between their first language (L1) and their L2. According to Connor’s (2011) intercultural rhetoric, different cultures possess distinct rhetorical traditions that influence how individuals structure their arguments, develop ideas, and employ persuasive strategies. In this context, L2 learners may transfer rhetorical strategies and expectations from their L1 to their L2 writing. This is particularly relevant for English as a foreign language (EFL) learners, who are the focus of the current study, as they might approach English academic writing differently from American students given that Arabic and English are typographically, linguistically, and culturally distant languages. For instance, while American and British academic writing typically values explicit argumentation, directness, and clarity, Arabic, along with several Asian and Eastern cultures, is known for placing greater emphasis on indirectness, humility, and harmony. Therefore, examining how EFL writers express argumentation in their L2 English is an intriguing area of research.

Given the significant importance of argumentative writing and the considerable challenges it poses, numerous studies have investigated how language learners, particularly those studying EFL, construct arguments (e.g., Guo et al., 2024; Lee & Lee, 2024; Li & Wang, 2024; Zarrabi & Bozorgian, 2020). However, research on the use of persuasive strategies by EFL learners in their argumentative writing remains scarce. Thus, this study aims to address this gap by examining how EFL learners employ persuasive strategies in their argumentative writing, comparing their English compositions with both their Arabic writing and that of native English speakers. This comparison is crucial for several reasons. First, there is a genuine gap in the literature regarding how EFL learners attempt to persuade readers. It is important to address this gap because it will inform the fields of contrastive rhetoric and EFL pedagogy. By revealing how learners navigate persuasive writing in both their first and second languages, the study can contribute to a deeper understanding of the rhetorical adjustments learners make and the challenges they face, which in turn can guide more effective teaching strategies and curriculum design. Second, the current study contrasts two distinct languages, as noted earlier. Thus, the findings will be highly relevant to the field of contrastive rhetoric. Third, this study involves a tripartite comparison between the writings of EFL learners in their first language (Arabic) and their second language (English), alongside native speakers of English. This type of comparison is often overlooked in the literature, yet it is essential as it allows an examination of EFL learners’ second language writing compared to two pertinent baselines (i.e., writings in Arabic by NSs of Arabic and in English by NSs of English). This tripartite comparison constitutes a significant contribution to the present study. Finally, this investigation explores the influence of language proficiency on EFL learners’ use of persuasive strategies. The findings will offer valuable insights for educators, emphasizing the importance of incorporating targeted instructional interventions in teaching argumentative writing, especially regarding the application of persuasive strategies.

To provide context for the present study, the upcoming sections will explore the relevant theoretical frameworks as well as provide a review of key studies. Subsequently, the research questions, methodology, and results analysis will be presented. The article will conclude by discussing pedagogical implications and suggesting directions for future research.

2 Theoretical Background

The present study examines the rhetorical persuasive strategies utilized in the argumentative paragraphs produced by both EFL learners and native English speakers. The study of rhetorical persuasion strategies dates back to Aristotle’s triad of persuasive appeals: ethos, logos, and pathos. As noted by Perloff (2010), Aristotle identified three essential components of persuasion: ethos, which pertains to the character of the communicator; pathos, which relates to the emotional state of the audience; and logos, which focuses on the logic and reasoning within the message (p. 28). Thus, Aristotle’s three appeals involve emphasizing the credibility of the speaker’s information in the case of ethos, the provision of facts and logical content in the case of logos, and the use of emotions in the case of pathos. Although several studies have employed these appeals to examine the power of persuasion in different genres, they often lack a more in-depth and comprehensive model that associates each appeal with relevant persuasive strategies and linguistic resources (El-Dakhs et al., 2024).

To address this limitation, the current study adopts a more recent model of persuasion based on Aristotle’s three appeals. Proposed by Dontcheva-Navratilova et al. (2020) and informed by corpus studies, this model categorizes various rhetorical strategies into ethos, logos, and pathos. In addition, it offers four tailored versions of this classification to meet the specific needs of business, religious, technical, and academic discourse. The business version applies to any form of communication within the realm of business. The religious version pertains to texts that comment on, interpret, or refer to religious matters. The technical version is suited for texts aiming to disseminate knowledge and technological advancements. The academic version is most appropriate for texts used in academic settings, including academic paragraphs, as is the case in this study. Therefore, we utilize the academic version of the model to analyze the participants’ paragraphs in the current study. A thorough description of the model is provided in the methodology section of this paper.

The persuasive model proposed by Dontcheva-Navratilova et al. (2020) comprises persuasive strategies together with pertinent linguistic resources to implement these strategies. Most of these linguistic resources consist of metadiscourse markers, which serve as lexical tools to organize discourse, express attitudes, present evidence, and establish a connection with the reader (Afzaal et al., 2022). Hyland’s (2005) taxonomy categorizes metadiscourse into interactive and interactional markers, providing a valuable framework for analysis. Interactive markers, which include logical connectives, frame markers, endophoric markers, evidentials, and code glosses, assist readers in navigating the text. Conversely, interactional markers – such as hedges, boosters, attitude markers, self-mentions, and engagement markers – are designed to engage readers and promote their active participation in the text. Table 1 presents an overview of Hyland’s taxonomy, featuring specific markers and illustrative examples.

Hyland’s (2005) taxonomy of metadiscourse

| Category | Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Textual | Help to guide reader through the text | Resources |

| Logical connectives (transitions) | Express relations between main clauses | and, but, in addition, however, thus |

| Frame markers | Refer to discourse acts, sequences or stages | My purpose is…, first, second, the findings are…, In conclusion |

| Endophoric markers | Refer to information in other parts of the text | mentioned above, as follows |

| Evidentials | Refer to information from other texts | according to…., X states that… |

| Code glosses | Elaborate propositional meanings | in other words, it means that…, such as…, e.g., for example |

| Interpersonal | Involve the reader in the text | Resources |

| Hedges | Withhold writer’s full commitment to statements | may, might, could, would, perhaps, some, possible |

| Boosters | Emphasize force or writer’s certainty | in fact, definitely |

| Attitude markers | Express writer’s attitude including significance, obligation to proposition | should, have to, agree, surprisingly |

| Self-mentions | Refer to author(s) explicitly | I, my, exclusive we, our |

| Engagement markers | Build relationship with reader explicitly | imperatives (e.g., Please note that…), You can see that…, inclusive We |

3 Literature Review

Aristotle’ s principles of persuasion have been widely applied to analyze persuasive discourse across various genres. These include public speaking (e.g., Fanani et al., 2020; Zhiyong, 2016), research article abstracts (e.g., El-Dakhs et al., 2024; Mohamad, 2022), letters (e.g., Al-Momani, 2014; Chakorn, 2006), emails and faxes (e.g., Krishnan et al., 2020; Zhu, 2013), and social media posts (e.g., Berlanga et al., 2013; El-Dakhs, 2022). However, only two studies have utilized Aristotle’s appeals to examine the persuasive strategies in argumentative essays. One of these studies, conducted by Kamimura and Oi (1998), compared the argumentative techniques used in English essays about capital punishment by American and Japanese students. The analysis of 42 essays by high school students from both groups encompassed aspects such as organizational patterns, rhetorical appeals, diction, and cultural influences. The findings indicated that American students relied more on logical appeals (logos) by presenting rational justifications, while Japanese students favored emotional appeals (pathos), focusing on eliciting empathy and influencing emotions. The second study that employed Aristotle’s persuasive appeals in examining argumentative essays was conducted by Uysal (2012), who attempted to investigate how 18 native Turkish speakers expressed arguments in both their native language (Turkish, L1) and English (L2). To examine the different preferences within a cultural-educational framework, the participants completed a survey regarding their previous writing instruction, wrote argumentative essays in their L1 and L2, and participated in interviews. The essays were analyzed for the use of argument structures, indirect devices, persuasive appeals, and language style. The results indicated that despite the participants’ differences in their L2 competence and their previous L2 writing history, the L1 and L2 essays were similar for most categories, such as explicit statements of claims, similar frequencies of indirect devices, hedging, and the use of Aristotle’s rhetorical appeals. These similarities were interpreted in terms of a bi-directional transfer between the two languages (i.e., Turkish and English), as most patterns were traced to both L1 and L2 instructional contexts. The results also revealed some culture-motivated contrasts between the Turkish and English essays, particularly in the use of assertive devices, rhetorical questions, and elaborative language.

It must be obvious that there is a genuine lack of research on how L2 learners incorporate persuasive appeals in argumentative essays, with only two studies having thus far attempted to examine their use (i.e., Kamimura & Oi, 1998; Uysal, 2012). Nevertheless, several limitations were identified within the designs of these studies. First, they employed appeals without a comprehensive model that links these appeals to concrete linguistic resources for realizing them. The present study addresses this concern by employing the comprehensive model of persuasion by Dontcheva-Navratilova et al. (2020), as mentioned earlier. Second, Kamimura and Oi (1998) compared the use of persuasive appeals as utilized natively in two languages, while Uysal (2012) examined the appeals in the two languages of bilinguals. Neither of these two studies attempted to investigate L2 essay writing while comparing the use of persuasive appeals in the bilinguals’ L1 and L2 with essays written by L1 speakers as a baseline for comparison. The current study overcomes this limitation by examining Arabic–English bilinguals’ essays in their L1 and L2 in comparison with American students’ essays in their L1.

As in the case of Aristotle’s persuasive appeals, metadiscourse markers have been examined across a wide range of genres, including research articles (e.g., El-Dakhs, 2018a, b; Kashiha, 2021), master’s and doctoral theses (e.g., Kawase, 2015; Míguez-Álvarez et al., 2023), academic blogs (e.g., Hyland & Zou, 2020; Zou & Hyland, 2020), and book reviews (e.g., Birhan, 2021; Soleimani et al., 2020). However, studies examining metadiscourse markers in argumentative essays are far less common. One relevant study is Kobayashi (2016), which investigated the use of metadiscourse markers in English essays written by EFL learners from diverse L1 backgrounds, including Chinese, Indonesian, Japanese, Korean, Taiwanese, and Thai. The analysis revealed notable differences in the frequency of marker usage between the East Asian group (Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese) and the Southeast Asian group (Indonesian and Thai). Each group exhibited distinct patterns of marker usage. For instance, Japanese learners overused frame markers, reflecting a superficial focus on logical structure that resulted in artificial, mechanical prose. Surprisingly, Japanese learners also employed self-mentions, boosters, and attitude markers more frequently than other groups, despite Japanese being a reader-responsible language with grammatical features – such as the omission of subjects – that might suggest reduced use of self-mentions.

In addition to comparing the use of metadiscourse markers among EFL learners of different L1 backgrounds, other studies investigated the relationship between metadiscourse markers and essay quality, comparing their use in successful and less-successful argumentative essays. For instance, Lee and Deakin (2016) investigated how Chinese english as a second language (ESL) students used interactional metadiscourse in argumentative essays, comparing successful and less successful examples. They also compared the writing of these students with the high-rated essays written by L1 speakers. The analysis of the three groups of essays (i.e., 25 successful ESL essays, 25 less-successful ESL essays, and 25 successful essays by L1 speakers) revealed significant differences in the use of certain stance and engagement resources in the three groups. For example, successful essays, written by both native and non-native English speakers, utilized significantly more hedging devices compared to less successful essays. The results also failed to find statistically significant differences across the three groups regarding the use of other metadiscourse markers, such as boosters and attitude markers. Interestingly, the study revealed that the L2 speakers were generally reluctant to establish an authoritative identity in their writing, a finding that came in contrast to L1 speakers’ preference to establish a clear authorial identity.

Park and Oh (2018) examined the use of metadiscourse markers in argumentative essays written by native English speakers and Korean EFL learners of varying proficiency levels. Their analysis of interactive and interactional markers showed significant differences in both the quantity and quality of metadiscourse usage across proficiency levels. The findings showed that higher language proficiency correlated with decreased use of interactive markers, more balanced use of interactional markers (like hedges and boosters), and the overall number of metadiscourse markers increased. This suggests that higher language proficiency fosters a more dialogic approach to interaction and greater audience engagement in learners’ persuasive writing.

The connection between language proficiency and the use of metadiscourse markers has spurred additional research. For instance, El-Dakhs (2020) investigated the impact of language proficiency and learning context (EFL vs ESL) on metadiscourse use in 180 argumentative essays. These essays, written by American undergraduates and Japanese (EFL) and Hong Kong (ESL) learners, were sourced from the International Corpus Network of Asian Learners of English (ICNALE). Using Hyland’s (2005) metadiscourse taxonomy, the analysis showed that learning context significantly affected marker use. For example, EFL learners employed more frame markers, attitude markers, and self-mentions compared to the ESL group, while the ESL group used more hedges. In contrast, language proficiency had a more limited effect, influencing only the frequent use of transition markers, frame markers, and interactive markers by the lower proficiency group.

Taken together, the studies on metadiscourse reflect two limitations for this line of research. First, the research on the use of metadiscourse markers in argumentative essays has been restricted to specific language backgrounds. Most studies have focused on East Asian English learners, particularly Chinese, Japanese, and Korean students. Second, research in this area has mainly relied on comparing two corpora of argumentative essays: namely, one by EFL/ESL learners and one by native speakers of English. No earlier research considered including the essays of the same EFL/ESL learners in their native languages as a baseline for comparison. The current study overcomes these limitations by focusing on Saudi learners of EFL, a relatively underrepresented population in this line of research. In addition, the current study compared the argumentative essays of those EFL learners in both English and Arabic with the argumentative essays of American (L1) speakers. Hence, a baseline for comparison is established. Therefore, the current study fills a true gap in the literature by overcoming the limitations of earlier research on persuasion and previous studies on metadiscourse in relation to argumentative L2 writing. By integrating learners’ L1 writing into the analysis, the study contributes to contrastive rhetoric by illuminating how cultural and linguistic norms shape persuasive practices across languages. This understanding is essential for EFL pedagogy, as it can inform more nuanced, culturally responsive instruction that helps learners bridge rhetorical expectations in their L1 and L2 writing.

3.1 Research Questions

The current study examines the following research questions:

What are the persuasive strategies used by EFL learners in their L2, English?

What are the persuasive strategies used by EFL learners in their L1, Arabic?

What are the persuasive strategies used by native speakers of English in their L1, English?

To what extent do persuasive strategies exhibit a different frequency of occurrence in the native and nonnative speakers’ argumentative paragraphs?

To what extent does language proficiency modulate the frequency of occurrence of persuasive strategies in EFL learners’ paragraphs?

4 Methodology

4.1 Participants

Eighty-one female Arabic–English bilinguals, aged 19–23 (average age of 21), were initially recruited to participate in the study. These students were enrolled in the Translation Department of a Saudi public university and were in their second or third year of study. The participants had completed several introductory linguistics and language enhancement courses, including an academic writing course, and were currently taking more advanced and specialized courses, including translation courses. All participants were native Arabic speakers and studied EFL. Participation in the study was voluntary. It must be noted that the study focused solely on female students because the researchers had access only to the female campus of the Saudi university from which the data were collected. Most Saudi universities have separate male/female campuses for undergraduate students and the second and third researchers of the current study were teaching in the female campus. It is advised to include male and female data in a future study and, perhaps, examine the effect of gender on the use of persuasive strategies.

The participants took the Oxford Quick Placement Test (OQPT) (2001), which had reading, vocabulary, and grammar parts (maximum score = 60), as an approximate indicator of their English language skills. With scores ranging from 27 to 58, they fell into the A2–C2 range for language proficiency according to the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). It must be noted that since the study required completing a language proficiency test and participating in writing two argumentative paragraphs at different times, 21 participants who missed one or more of these requirements were excluded from the study, and thus, there were 60 EFL students in the final participation pool.

The study used 60 paragraphs written by American undergraduate students who were native English speakers in addition to the 60 EFL learners. These paragraphs were sourced from the ICNALE, a corpus developed by Dr. Shin’ichiro Ishikawa at Kobe University in Japan. The ICNALE includes 1.3 million words from second-language paragraphs collected from ten Asian countries, as well as paragraphs written by native English speakers for comparison. This corpus is ideal for comparative research, as it standardizes key factors such as essay length, writing time, and topics.

4.2 Instruments

In the present study, two instruments were employed. The initial assessment tool employed was the OQPT, a standard instrument in research for measuring English language proficiency. This test aligns participant scores with the CEFR. Comprising 60 questions, the OQPT evaluates language skills through a written format, concentrating on grammatical concepts, including verb tenses, passive voice, parts of speech, and statements with conditions, as well as lexical features like word definitions, collocations, synonyms, antonyms, and phrases. The first five questions require participants to identify the usual locations of various notices, while questions six through twenty and forty-one to fifty involve completing sentences in short passages. For these tasks, test-takers select from three or four possible answers. This selection process is also necessary for items twenty-one through forty and fifty-one to sixty, which feature standalone sentences with blanks to be filled. The test has a total possible score of 60.

The second instrument was a computer-based writing task, which participants used when completing the writing tasks in English and Arabic. Participants were instructed to write a paragraph supporting or refuting the statement: “It is important for college students to have a part-time job.” The participants were asked to write 200–300 words in 30–40 min. It should be highlighted that the participants received prompts in the same language in which they were instructed to write. Specifically, prompts were given in Arabic for Arabic paragraphs and in English for English paragraphs. It must be noted that the ICNALE paragraphs by the English native speakers were written on the same prompts and under the same conditions.

4.3 Procedures

The following three tasks were carried out by the participants:

The participants completed the OQPT to gauge their level of language proficiency after signing the consent form. Although the test had no time constraint, most participants finished it in 30–40 min.

The participants were asked to compose an argumentative paragraph 2 days after finishing the test. The writing was done in a counterbalanced manner with respect to the language in order to obviate any confounding effects. That is, half the participants wrote the Arabic paragraphs first while the other half wrote the English paragraphs first.

After a month, the participants wrote the second argumentative paragraph in the other language. One month separated the first and second writing tasks to minimize any possible effect of the paragraphs on one another.

It must be noted that while our findings are expected to reveal cross-linguistic patterns, future research should diversify prompts (e.g., social vs academic topics) and participant demographics (e.g., gender-balanced cohorts) to assess generalizability.

4.4 Data Coding

After collecting the paragraphs, the data coding followed. The coding was completed by two coders; namely, the first researcher who holds a PhD in Linguistics and a research assistant who holds an MA in Linguistics. The coding was completed by the two coders independently as per the persuasion model of Dontcheva-Navratilova et al. (2020) as shown in Appendix B. An illustrative paragraph of the coding is provided in Appendix C. A comparison of the coding proved an inter-coder reliability of 91%. The two coders discussed the areas of disagreement until they reached an agreement on all the coding.

4.5 Analysis

An Excel sheet was created for each group of paragraphs, containing the participant’s number, the proficiency score of the EFL learners, the word count of each paragraph, and the numerical coding of the data. The first three study topics were addressed using descriptive statistics, calculating the number and frequency of strategies. For the fourth and fifth research questions, inferential statistics were applied. Before conducting inferential tests, the number of persuasive strategies was normalized to account for variations in paragraph length, meaning that the analysis focused on the ratio of total strategies to total words in each paragraph. The use of persuasive strategies in the three paragraph groups was then compared using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test (Research Question 4). The impact of English language proficiency on the use of persuasive strategies in the English paragraphs submitted by the EFL learners was then investigated using the Pearson Correlation test (Research Question 5).

5 Results

This section is divided as per the research questions.

5.1 What are the Persuasive Strategies Used by EFL Learners in English?

The persuasive strategies used by the students in English are represented in frequencies in Table 2. A little less than half of the strategies were represented in logos, particularly in the use of logical reasoning, including logical connections between sentences. This is followed by the use of pathos strategies, which occupied almost a third of the strategies in total. The pathos strategies were primarily represented with the use of expressive evaluation, which uses attitude cues and evaluative language, while fostering a collaborative environment, which involves using reader reference, appeals to shared knowledge, questions, and asides. Ethos was the final category of tactics, accounting for little over one-fifth of all strategies. The ethos strategies were primarily dominated by modulating commitment to claims, as mostly reflected by the usage of boosters and hedges.

The persuasive strategies in EFL learners’ English paragraphs

| No. | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ethos Logos Pathos | 1,769 | |

| Ethos | 421 | 23.8 |

| Showing involvement | 94 | 5.3 |

| Sharing personal views | 66 | 3.7 |

| Modulating commitment to claims | 222 | 12.5 |

| Reference to authority | 0 | 0.0 |

| Providing credientials | 0 | 0.0 |

| Claiming common ground | 36 | 2.0 |

| Sense of community | 3 | 0.2 |

| Reference to expert knowledge | 0 | 0.0 |

| Logos | 765 | 43.2 |

| Logical reasoning | 763 | 43.1 |

| Reference to statistics and facts | 2 | 0.1 |

| Experimental proof | 0 | 0.0 |

| Proof by exemplification/testing | 0 | 0.0 |

| Providing evidence | 0 | 0.0 |

| Pathos | 583 | 33.0 |

| Evoking positive/negative emotions | 60 | 3.4 |

| Expressive evaluation | 212 | 12.0 |

| Creating an atmosphere of collegiality | 311 | 17.6 |

Below are two illustrative excerpts from the paragraphs written in English by the Arab EFL learners (the paragraphs are taken as is from the data without correcting mistakes):

Example 1

First [logos – logical reasoning] I [ethos – showing involvement] really [ethos – modulating claims] agreed that student college should [logos – logical reasoning] do a part time job. In my opinion [ethos – sharing personal views] I think [ethos – sharing personal views] part time jobs have many benefit on college student So [logos – logical reasoning] I [ethos – showing involvement] am going to write some of the Advantages of college student to have a part-time job.

Example 2

Being a college student working a part-time job can be difficult [pathos – expressive evaluation] at times, but [logos – logical reasoning] at tough [pathos – expressive evaluation] times comes great [pathos – expressive evaluation] success. With that being said, it’s good [pathos – expressive evaluation] for students to work part time jobs because [logos – logical reasoning] they can gain a lot of experience, how to handle people, along with having a stable income.

5.2 What are the Persuasive Strategies Used by EFL Learners in Arabic?

The frequencies of persuasive strategies used by students in Arabic are shown in Table 3. Nearly half of the strategies were logos, primarily consisting of logical reasoning (i.e., using logical connections between sentences). Ethos strategies accounted for just over a quarter of the total strategies, with the most common form being modulation of commitment to claims (i.e., hedges and boosters). The fewest strategies were pathos, representing almost a fifth of the total, and these were mainly expressed through evaluative language and attitude markers (i.e., expressive evaluation).

The persuasive strategies in the EFL learners’ Arabic paragraphs

| No. | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ethos Logos Pathos | 1,471 | |

| Ethos | 424 | 28.8 |

| Showing involvement | 26 | 1.8 |

| Sharing personal views | 63 | 4.3 |

| Modulating commitment to claims | 291 | 19.8 |

| Reference to authority | 0 | 0.0 |

| Providing credientials | 0 | 0.0 |

| Claiming common ground | 33 | 2.2 |

| Sense of community | 11 | 0.7 |

| Reference to expert knowledge | 0 | 0.0 |

| Logos | 717 | 48.7 |

| Logical reasoning | 714 | 48.5 |

| Reference to statistics and facts | 2 | 0.1 |

| Experimental proof | 0 | 0.0 |

| Proof by exemplification/testing | 1 | 0.1 |

| Providing evidence | 0 | 0.0 |

| Pathos | 330 | 22.4 |

| Evoking positive/negative emotions | 73 | 5.0 |

| Expressive evaluation | 197 | 13.4 |

| Creating an atmosphere of collegiality | 60 | 4.1 |

The following are two illustrative excerpts from the paragraphs written in Arabic by EFL learners and their translations (the paragraphs are taken from the data without correcting mistakes):

Example 1

من رأيي الشخصي يعد الحصول على وظيفة بوقت جزئي أمر ممتاز خاصة لطلاب الجامعات لأن الوظيفة هي الطريقة الأمثل لاكتساب الخبرة اثناء مسيرة الطالب الجامعية التي بإمكانه اضافتها في سيرته الذاتية، وأيضًا حصول الطالب الجامعي على وظيفة يمكنه من التعلم وتطوير مهاراته الشخصية في سن مبكر وبالتالي يجعله أكثر نضج واتزان مقارنةً بباقي أقرانه.

In my personal opinion [ethos – sharing personal views], holding a part-time job is considered an excellent [pathos – expressive evaluation] matter especially for university students because [logos – logical reasoning] having a job is the ideal [pathos – expressive evaluation] way to gain experience during the university student’s journey that could [ethos – commitment to claims] be added to the student’s CV. Additionally [logos – logical reasoning], having a job allows the university student to learn and develop personal skills at an early age, and [logos – logical reasoning], consequently [logos – logical reasoning], make the student more [ethos – commitment to claims] mature and balanced compared to other counterparts.

Example 2

الوظيفة تهيء الطلاب الجامعيين بشكل كبير للمستقبل وتجعله اوعى اجتماعيا وماديا ونفسياً وايضا تنظم وقته. الطلاب الجامعيين يجب عليهم اخذ وظيفه كدوام جزئي بعد الانتهاء من محاضرات الجامعة لكسب الخبرة والمعرفة وايضاً تقوية المهارات لديهم كمهارة التحدث والاستماع والكتابة وغيرها.

Having a job greatly [ethos – commitment to claims] qualifies university students for the future. It also [logos – logical reasoning] makes them more [ethos – commitment to claims] aware socially, financially and psychologically, and [logos – logical reasoning] plans their time. University students should [logos – logical reasoning] have a part-timer job after finishing their university lectures to gain experience and knowledge and [logos – logical reasoning] also [logos – logical reasoning] to improve their skills, like [logos – exemplification] speaking, listening, writing, etc.

5.3 What Are the Persuasive Strategies Used by Native Speakers of English?

The native English speakers employed persuasive strategies differently, as shown in Table 4. Over half of the strategies were ethos-based, with a focus on showing involvement (i.e., self-mentions) and modulating commitment to claims (i.e., hedges and boosters). Logos strategies accounted for nearly a quarter of the total, primarily in the form of logical reasoning (i.e., using logical connections between sentences). The fewest strategies were pathos, making up almost a fifth of the total. The pathos appeal was mainly expressed through expressive evaluation (i.e., evaluative language and attitude markers) and creating a sense of collegiality (i.e., reader references, appeals to shared knowledge, questions, asides).

The persuasive strategies in the English native speakers’ paragraphs

| No. | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Ethos Logos Pathos | 1,738 | |

| Ethos | 905 | 52.1 |

| Showing involvement | 348 | 20.0 |

| Sharing personal views | 144 | 8.3 |

| Modulating commitment to claims | 328 | 18.9 |

| Reference to authority | 1 | 0.1 |

| Providing credientials | 0 | 0.0 |

| Claiming common ground | 28 | 1.6 |

| Sense of community | 56 | 3.2 |

| Reference to expert knowledge | 0 | 0.0 |

| Logos | 497 | 28.6 |

| Logical reasoning | 495 | 28.5 |

| Reference to statistics and facts | 2 | 0.1 |

| Experimental proof | 0 | 0.0 |

| Proof by exemplification/testing | 0 | 0.0 |

| Providing evidence | 0 | 0.0 |

| Pathos | 336 | 19.3 |

| Evoking positive/negative emotions | 78 | 4.5 |

| Expressive evaluation | 126 | 7.2 |

| Creating an atmosphere of collegiality | 132 | 7.6 |

Below are two illustrative excerpts from the paragraphs written in English by English native speakers (the paragraphs are taken as is from the data without correcting mistakes):

Example 1

I [ethos – showing involvement] am a student completing a full-time degree and working a part-time job out of necessity because [logos – logical reasoning] my [ethos – showing involvement] parents do not have enough money to pay for all of my [ethos – showing involvement] tuition and I [ethos – showing involvement] wasn’t fortunate enough to receive a scholarship although [logos – logical reasoning], I [ethos – showing involvement] applied for several.

Example 2

It was important [pathos – expressive evaluation] for me [ethos – showing involvement] because [logos- logical reasoning] it allowed me [ethos – showing involvement] to take time off and travel to Japan. I know [ethos – sharing personal views] that some of my [ethos – showing involvement] friends work because [logos – logical reasoning] they wanted the money for student fees and books etc. At first [logos – logical reasoning], I [ethos – showing involvement] had the same plan as they did but [logos – logical reasoning] as time went on I [ethos – showing involvement] found that I [ethos – showing involvement] was losing interest in studying and always tired.

5.4 To What Extent do Persuasive Strategies Exhibit a Different Frequency of Occurrence in the Native and Non-Native Speakers’ Argumentative Essays?

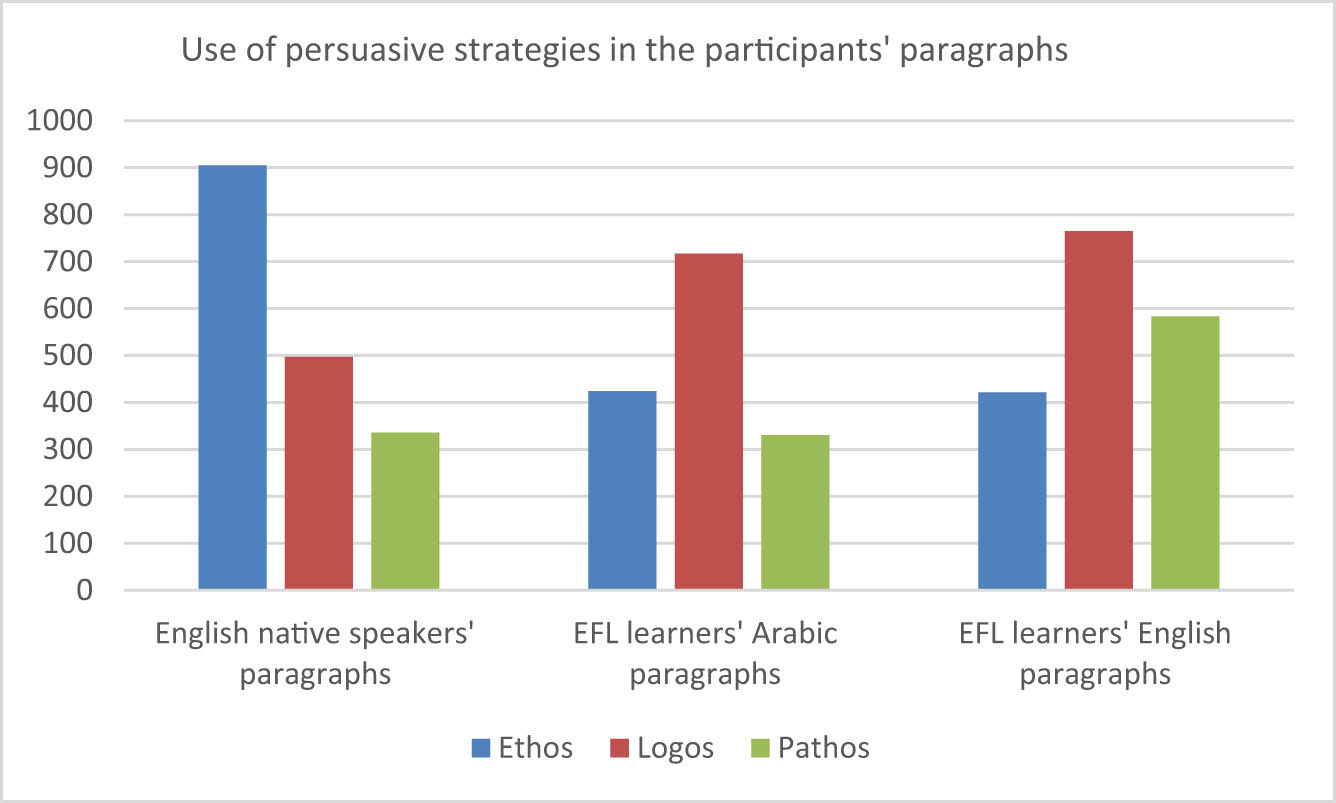

The use of different persuasive strategies in the participants’ paragraphs is represented in Figure 1 below:

Use of the persuasive strategies in the participants’ paragraphs.

A one-way ANOVA test was used to look at how often persuasive strategies appeared in the argumentative essays written by native speakers and EFL learners. As shown in Table 5, several significant differences were found. First, native speakers of English used ethos strategies significantly more often, particularly in showing involvement (i.e., self-mentions), sharing personal views (i.e., self-mentions and attitude markers), modulating commitment to claims (i.e., hedges and boosters), and creating a sense of community (i.e., self-mentions, appeals to shared knowledge). Second, Arabic–English bilinguals used logos strategies more frequently than native speakers, especially in the form of logical reasoning (i.e., logical connections between sentences) in both their English and Arabic paragraphs. Third, the Arabic–English bilinguals employed the pathos appeal considerably more frequently in their English paragraphs, particularly when fostering a sense of camaraderie (i.e., reader references, appeals to common knowledge, enquiries, and asides). Regarding the expressive evaluation strategy (i.e., evaluative language and attitude markers) under the pathos appeal, it was employed significantly less frequently by native speakers of English than by the Arabic–English bilinguals.

One-way ANOVA results of the persuasive strategies

| EFL Participants – English paragraphs | EFL Participants – Arabic paragraphs | NS Baseline – English paragraphs | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| Ethos | 2.92 ± 1.87 | 3.02 ± 1.50 | 6.94 ± 2.95 | 66.291* | <0.001* |

| Showing involvement | 0.65 ± 0.86 | 0.18 ± 0.40 | 2.64 ± 2.50 | 43.426* | <0.001* |

| Sharing personal views | 0.45 ± 0.57 | 0.47 ± 0.58 | 1.10 ± 0.68 | 21.496* | <0.001* |

| Modulating commitment to claims | 1.54 ± 1.06 | 2.07 ± 1.15 | 2.53 ± 1.16 | 11.807* | <0.001* |

| Reference to authority | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.01 ± 0.05 | 1.017 | 0.364 |

| Providing credentials | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | — | — |

| Claiming common ground | 0.25 ± 1.27 | 0.22 ± 0.31 | 0.22 ± 0.40 | 0.028 | 0.973 |

| Sense of community | 0.02 ± 0.14 | 0.07 ± 0.24 | 0.45 ± 0.97 | 9.550* | <0.001* |

| Reference to expert knowledge | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | — | — |

| Logos | 5.35 ± 2.21 | 5.20 ± 1.43 | 3.84 ± 1.09 | 15.375* | <0.001* |

| Logical reasoning | 5.34 ± 2.20 | 5.18 ± 1.43 | 3.83 ± 1.08 | 15.441* | <0.001* |

| Reference to statistics and facts | 0.02 ± 0.09 | 0.01 ± 0.07 | 0.02 ± 0.09 | 0.021 | 0.979 |

| Experimental proof | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | — | — |

| Proof by exemplification/testing | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.01 ± 0.06 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.992 | 0.373 |

| Providing evidence | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | — | — |

| Pathos | 3.99 ± 3.10 | 2.36 ± 1.55 | 2.61 ± 2.0 | 8.868* | <0.001* |

| Evoking positive/negative emotions | 0.40 ± 0.70 | 0.52 ± 0.77 | 0.61 ± 0.67 | 1.227 | 0.296 |

| Expressive evaluation | 1.49 ± 0.92 | 1.43 ± 1.19 | 0.98 ± 0.87 | 4.769* | 0.010* |

| Creating an atmosphere of collegiality | 2.10 ± 2.93 | 0.41 ± 0.93 | 1.02 ± 1.66 | 10.939* | <0.001* |

F: F for One way ANOVA test.

*: Statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05.

5.5 To What Extent Does Language Proficiency Modulate the Frequency of Occurrence of Persuasive Strategies in EFL Learners’ Paragraphs?

A Pearson correlation test was conducted to determine whether L2 proficiency affected the Arabic–English bilinguals’ use of metadiscourse markers in their English paragraphs. The results presented in Table 6, show that the effect was limited to the use of the ethos strategies as a whole and the use of the pathos strategy of triggering pleasant or negative feelings (evaluative lexis and reader reference). The influence was positive. That is, increased language proficiency led to the increased use of the ethos appeal and the strategy of evoking positive/negative emotions.

Pearson correlation results regarding the effect of language proficiency

| Proficiency level | ||

|---|---|---|

| r | p | |

| Ethos | 0.256* | 0.047* |

| Showing involvement | 0.025 | 0.847 |

| Sharing personal views | 0.111 | 0.392 |

| Modulating commitment to claims | 0.236 | 0.067 |

| Reference to authority | — | — |

| Providing credentials | — | — |

| Claiming common ground | 0.135 | 0.299 |

| Sense of community | −0.146 | 0.260 |

| Reference to expert knowledge | — | — |

| Logos | −0.083 | 0.527 |

| Logical reasoning | −0.083 | 0.526 |

| Reference to statistics and facts | 0.007 | 0.956 |

| Experimental proof | — | — |

| Proof by exemplification/testing | — | — |

| Providing evidence | — | — |

| Pathos | 0.036 | 0.783 |

| Evoking positive/negative Emotions | 0.285 * | 0.026 * |

| Expressive evaluation | −0.023 | 0.859 |

| Creating an atmosphere of collegiality | −0.021 | 0.870 |

r: Pearson coefficient.

*: Statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05.

6 Discussion

The present study compared English and Arabic argumentative academic paragraphs written by Arabic–English bilinguals with English paragraphs written by native speakers of English. Five research questions were put out to accomplish the study aim. The first three research questions required the use of descriptive statistics, including the numbers and frequencies of the persuasive strategies and relevant linguistic resources used in these paragraphs. The results clearly showed that the appeal used mainly by the participants, whether in English or Arabic, is the logos appeal, as represented by the logical reasoning strategy. The excessive use of logical reasoning by the participants reflects the tendency of the Arabic language to make intersentential relations more explicit through the use of logical connectives (e.g., “wa” = and “fa-” = and/so). It is widely acknowledged that the Arabic language exhibits a more dense use of interclausal and intersentential connectors than the English language (Dickins, 2017). The English language, in contrast, tends to use fewer intersentential connectors as many of the connections are indicated implicitly.

Another finding related to the first three questions is that the appeal predominantly utilized by English native speakers is the ethos appeal, primarily represented by strategies involving showing involvement and modulating claims. According to Connor’s (2011) Intercultural Rhetoric framework, American writers may have developed this rhetorical choice based on specific cultural priorities. The individualistic nature of American society helps explain the predominant use of the ethos appeal, which likely pushed American writers to emphasize their involvement through the frequent use of self-mentions. In addition, there is a significant reliance on the strategy of modulating claims, as often represented by hedges and boosters. However, this usage is similar to the choices made by EFL learners in both their English and Arabic writing. Thus, this appears to be a feature of argumentative writing in general, which emphasizes specifying arguments carefully with boosting or hedging when necessary.

As for the pathos appeal, it was the least used by both the EFL learners and the English native speakers. This relative underuse of the pathos appeal might be a reflection of the nature of college argumentation writing, which is often dependent on facts and logical content in addition to obvious elements of credibility rather than emotional content. Interestingly, the majority of the pathos appeal in the three groups of paragraphs was represented by the use of evaluative lexis and attitude markers, which is expected since the argumentative paragraph the participants were required to write involved taking a position for or against having a part-time job during college years. Hence, it comes as no surprise that the participants would describe their choices with evaluative lexis and attitude markers. It must be noted that English native speakers and EFL writers in their English paragraphs created an atmosphere of collegiality through the frequent use of questions and appeals to common knowledge to a relatively great extent. According to Connor’s (2011) intercultural rhetoric, American writers may follow different writing conventions based on their cultural backgrounds. In this context, American English is known to be a writer-responsible language. This means that English native speakers are expected to involve their readers in their writing using various markers. In contrast, Arabic–English bilinguals may find it easier to replicate this approach because questions and appeals to shared knowledge (e.g., “as you may know”) are straightforward structures that EFL learners can employ easily. This result was also found in a previous study by El-Dakhs et al. (2022) about the use of metadiscourse markers by EFL learners in which it was found that instruction led the learners to use these two structures easily in their persuasive writing.

The fourth research question sought to explore potential statistical variations in the application of persuasive strategies by Arabic–English bilinguals and native speakers of English. A one-way ANOVA test, which applied inferential statistics, revealed several statistically significant differences. One notable difference was related to the logos appeal. The EFL learners used logical reasoning far more frequently than native English speakers. This finding contrasts with the results of Kamimura and Oi (1998), who found that native English speakers used logos more frequently than Japanese speakers. However, this discrepancy was previously explained by the Arabic language’s tendency to use a large number of intersentential connectors (Dickins, 2017), which led to increased utilization of logical reasoning strategies and, consequently, a greater appeal to logos. In addition to the differences in logos, it was also found that native English speakers employed a substantially higher number of ethos strategies compared to EFL learners. This was evident in strategies such as showing involvement, sharing personal views, modulating claims, and community engagement. Once again, this statistical disparity can be attributed to the individualistic nature of American society, which emphasizes the use of self-mentions and individual opinions. It is widely recognized in the literature (e.g., Hu & Cao, 2011) that English writers often adopt a tentative stance in their writing, influenced by the rhetorical norms of the Anglo-American discourse community, which have roots in Socratic and Aristotelian philosophical traditions. These traditions place great importance on challenging notions and assumptions, critically evaluating knowledge, acknowledging subjectivity, and considering multiple interpretations.

Notably, the results of research by Lee and Deakin (2016) and El-Dakhs (2020) are consistent with the finding that native English speakers utilized a much higher number of hedges than EFL learners. Furthermore, compared to English native speakers, EFL learners employed the pathos appeal much more frequently. This was noted in the learners’ Arabic and English paragraphs regarding the usage of evaluative expression, primarily in the form of evaluative lexis. However, the difference was limited to the English paragraphs with the strategy of creating an atmosphere of collegiality. As explained earlier, it is relatively easy to incorporate simple grammatical structures (e.g., questions and “as you know”) in the learners’ writing to mirror the native speakers’ versions.

The fifth study question examined how EFL learners’ use of persuasive techniques in their English paragraphs was influenced by their English language proficiency level. Although the participants’ language abilities ranged from A2 to C2, the impact on the use of persuasive strategies was limited to an increased application of ethos appeal and emotion-evoking strategies. This limited influence indicates that the development of persuasive strategies does not necessarily advance with higher language proficiency. The Arabic–English bilinguals may continue to follow their native language patterns of persuasion, even when writing in a foreign language. One possible explanation for this is that learners may rely on culturally embedded rhetorical norms acquired through their first language, which are not automatically replaced or supplemented by new rhetorical conventions as language proficiency improves. The Arabic–English bilinguals in this study may have continued to follow their native language’s patterns of persuasion, even when writing in English, reflecting a transfer of L1 rhetorical preferences. In addition, instructional factors may play a role: many EFL curricula prioritize grammar, vocabulary, and general writing skills over rhetorical awareness and persuasive writing techniques. As a result, even advanced learners may not receive adequate training in adapting their persuasive strategies to fit the expectations of English argumentative writing. It must be noted that this finding aligns with Uysal’s (2012) results, which showed that Turkish EFL learners employed similar persuasive strategies in their L1 and L2. Therefore, explicit instruction on persuasive strategies and relevant linguistic resources may be considered essential for EFL learning, as recommended by Connor’s (2011) Intercultural Rhetoric framework, which posits that writers can learn to adjust their writing strategies through awareness-raising exercises, instructional interventions, and supported practice.

It is important to note that the current study’s findings should be interpreted with caution due to two key limitations. First, the Arabic–English bilinguals were all female undergraduates from a translation department at a public university. We collected data from this population because this is the population we had access to. The second and third researchers teach at the translation department from which the data were collected. In addition, they did not have access to the male campus because the male and female campuses are segregated. The female focus creates gender imbalance, preventing analysis of potential male–female differences in the data. It is recommended for future studies to collect data from both male and female participants and, perhaps, examine how the use of persuasive strategies might be influenced by gender differences. It is also recommended to collect data from non-English major students who might be using persuasive strategies differently. Second, the data were based on written paragraphs in response to a single prompt: “It is important for college students to have a part-time job.” Focusing solely on writings generated from one prompt raises concerns about the generalizability of our findings and leads us to draw tentative conclusions regarding the specific context in which the data were collected.

7 Conclusion

The purpose of this study is to investigate how EFL students employ persuasive techniques in their argumentative English writing. In light of this, 60 English argumentative paragraphs by Arabic–English bilinguals were compared with 60 Arabic paragraphs by the same participants and 60 English paragraphs by English native speakers for the use of persuasive strategies. The findings revealed statistically significant variations in the application of persuasive strategies in the three groups of paragraphs. Most importantly, the EFL learners tended to employ similar persuasive strategies in their Arabic and English paragraphs, which were sometimes different from the strategies employed in the English paragraphs by the American undergraduates. This was mostly obvious in the Arabic–English bilinguals’ more frequent use of logical reasoning and evaluative expression and less frequent use of showing involvement, sharing personal views, modulating commitment to claims, and community use. It was also found that increased language proficiency had limited influence on the persuasive strategies of EFL writers.

Based on these findings, we recommend explicit instruction in persuasive strategies and their relevant linguistic resources in university-level academic writing classes. As EFL learners followed persuasive patterns in their L2 similar to those in their L1, despite the rhetorical differences observed in American undergraduate writing, language instructors must address this disparity directly by adopting targeted pedagogical approaches. Notably, increased language proficiency alone did not significantly advance the use of persuasive strategies by EFL learners. One effective strategy is contrastive instruction, where students analyze and compare persuasive writing in Arabic and English, focusing on key rhetorical elements such as metadiscourse markers (e.g., transition words vs self-mentions) to enhance rhetorical awareness. In addition, a genre-based approach (Hyland, 2007) can be employed to increase students’ awareness of the specific conventions of argumentative writing by providing model texts, engaging them in scaffolded practice, and emphasizing audience expectations. Utilizing comprehensive frameworks, such as Dontcheva-Navratilova et al.’s (2020) model, further supports this process by linking Aristotle’s three persuasive appeals to concrete linguistic resources. It is important to note that our pedagogical implications align with Connor’s (2011) intercultural rhetoric, which posits that L2 learners can learn to modify their writing strategies to meet the expectations of L1 readers by raising their awareness of different writing conventions in both languages and engaging them in explicit instruction and practice.

In addition to these pedagogical recommendations, further research is needed to deepen our understanding of persuasive strategies in L2 writing. The use of persuasive appeals by L2 learners remains an area that requires further exploration, particularly regarding how these strategies vary across learners from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Comparative studies involving speakers of different L1s could provide valuable insights into whether transfer patterns in persuasive writing are universal among L2 learners or specific to particular language pairs. Future research could also investigate the impact of explicit instruction on the strategic use of ethos, logos, and pathos in L2 writing, examining how focused pedagogical interventions influence learners’ rhetorical awareness and performance. Longitudinal classroom-based studies might assess whether such instruction leads to sustained improvements, not just in the short term but across stages of language development. In addition, experimental designs could evaluate the relative effectiveness of different teaching approaches – such as genre-based instruction, contrastive rhetoric tasks, or corpus-informed writing exercises – in fostering adaptation to L2 rhetorical norms. Expanding the demographic scope of future studies to include male learners and learners from different educational contexts (e.g., secondary school, technical education) would also provide a more comprehensive understanding of how persuasive strategies develop across subgroups. By addressing these targeted research gaps, future studies can make stronger contributions to refining academic writing pedagogy and supporting L2 learners in achieving greater rhetorical competence.

-

Funding information: The researchers thank Prince Sultan University for funding this research project through the Language and Communication Research Lab (RL-CH-2019/9/1).

-

Author contributions: Dina Abdel Salam El-Dakhs, conception and design, analysis and interpretation, drafting of the paper & revising the paper critically for intellectual contribution. Noorchaya Yahya, design, data collection and coding & revising the paper critically for intellectual contribution. Buthainah M. Al Thowaini, design, data collection and coding & revising the paper critically for intellectual contribution. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

-

Conflict of interest: There are no conflict interests to declare.

-

Data availability statement: The research data will be made available upon request.

Appendix A – Typology of Persuasive Strategies in Academic Discourse by Dontcheva-Navratilova et al. (2020)

Ethos

Showing involvement (self-mentions)

Sharing personal views (self-mentions; attitude markers)

Commitment to claims (hedges; boosters)

Reference to authority/expertise (citations; text directives)

Providing credentials (self-citations)

Claiming common grounds (reader reference; appeal to shared knowledge)

Sense of community (self-mentions; appeal to shared knowledge)

Reference to expert opinion (citations; text act directives)

Logos

Logical reasoning (transition markers; cognitive directives)

Reference to statistics/facts (intratextual reference to data and visuals)

Experimental proof (reporting experimental results)

Proof by exemplification/testing (reporting statistical tests and sample analysis)

Providing evidence (referring to facts and other evidence)

Pathos

Evoking positive/negative emotions (reader reference; evaluative lexis)

Expressive evaluation (evaluative lexis; attitude markers)

Creating an atmosphere of collegiality (reader reference; appeal to shared knowledge; questions; asides)

Appendix B – Adapted Typology of Persuasive Strategies in Academic Discourse by Dontcheva-Navratilova et al. (2020)

| Strategy | Definition | Examples/Linguistic resources |

|---|---|---|

| Ethos | ||

| Showing involvement | Showing active participation in the text | self-mentions (e.g., I, we, our, us) |

| Sharing personal views | Expressing one’s opinions and thoughts | self-mentions (e.g., I, we, our, us); attitude markers (e.g., interestingly, unexpectedly) |

| Modulating commitment to claims | Exerting a modifying influence on the writer’s claims | hedges (e.g., kind of; a bit) and boosters (e.g., very; extremely) |

| Reference to authority/expertise | e.g., citations; text act directives (e.g., see, refer to, take a look at) | |

| Providing credentials | Writers refer to their former publications to enhance the credibility of their arguments | self-citations |

| Claiming common grounds | Referring to areas that the writer and the reader share and/or mutually identify | reader reference (e.g., you, your); appeals to shared knowledge (e.g., we know, needless to say, obviously, of course) |

| Sense of community | A sense of community and alliance with the audience may be achieved by acknowledging the reader’s presence, building shared common ground, and proximity of values and goals | Self-mentions (e.g., I, we, our, us); appeals to shared knowledge |

| Reference to expert opinion | Writers refer to the opinions of some experts to enhance the credibility of their arguments | Citations; text act directives (e.g., see, refer to, take a look at) |

| Logos | ||

| Logical reasoning | Presenting premises that lead to the drawing of certain conclusions that are entailed by the premises or providing explanations/causes for an action | Transition markers (e.g., however, furthermore); cognitive directives (e.g., imperatives; modals of obligation) |

| Reference to statistics and facts | Reference to data provided in the text, in other visual representations or outside the text | intratextual reference to data and visuals |

| Experimental proof | Reporting experimental results | The results showed; the findings of the experiment revealed |

| Proof by exemplification/testing | Reporting statistical tests and sample analysis | A T-test was conducted; The interviews were analyzed qualitatively |

| Providing evidence | Referring to facts and other evidence | Previous studies showed; Based on the literature survey |

| Pathos | ||

| Evoking positive/negative emotions | Triggering the readers’ emotions whether positively or negatively | reader reference (e.g., you, your); evaluative lexis (e.g., sustainable growth, good quality, novel, valuable) |

| Expressive evaluation | Expressing the author’s assessment of claims, facts and opinions mentioned in the text | evaluative lexis (e.g., sustainable growth, good quality, novel); attitude markers (e.g., valuable, significant, important) |

| Creating an atmosphere of collegiality | Highlighting the need for companionship and cooperation while sharing responsibility | reader reference (e.g., you, your); appeal to shared knowledge (e.g., we know, needless to say, obviously, of course); questions; asides (e.g., as you would agree) |

Appendix C – Sample of Data Coding

I [showing involvement/self-mention] am a student completing a full-time degree and working a part-time job out of necessity because [logical reasoning/transition marker] my [showing involvement/self-mention] parents do not have enough money to pay for all of my [showing involvement/self-mention] tuition and I [showing involvement/self-mention] wasn’t fortunate [evoking positive/negative emotions/evaluative lexis] enough to receive a scholarship although [logical reasoning/transition marker], I [showing involvement/self-mention] applied for several. Since [logical reasoning/transition marker] starting work, I [showing involvement/self-mention] can honestly [expressive evaluation/attitude marker] say that I [showing involvement/self-mention] am more [modulating commitment to claims/booster] confident, I [showing involvement/self-mention] manage my [showing involvement/self-mention] time a lot [modulating commitment to claims/booster] better [modulating commitment to claims/booster] than any of my [showing involvement/self-mention] classmates and [logical reasoning/transition marker] I [showing involvement/self-mention] seem [modulating commitment to claims/hedge] to have gained a certain level of respect from people that I [showing involvement/self-mention] wasn’t aware of before. It is difficult [evoking emotions/evaluative lexis] at times [modulating commitment to claims/hedge] especially during exams, but [logical reasoning/transition marker] I [showing involvement/self-mention] have been pretty [modulating commitment to claims/booster] lucky [evoking emotions/evaluative lexis] because [logical reasoning/transition marker] I [showing involvement/self-mention] have a very [modulating commitment to claims/booster] understanding [expressive evaluation/attitude marker] boss who goes out of his way to help me [showing involvement/self-mention] in any way that he can. I know [sharing personal views/self-mention] my [showing involvement/self-mention] money situation has improved, no surprises there but [logical reasoning/transition marker] I [showing involvement/self-mention] also [logical reasoning/transition marker] don’t stress out [evoking emotions/evaluative lexis] as much as some of my [showing involvement/self-mention] mates do when the pressure is on. I think [sharing personal views/self-mention] that the way I think about [sharing personal views/self-mention] and approach tasks has improved a lot [modulating commitment to claims/booster] and I [showing involvement/self-mention] make use of a few [modulating commitment to claims/hedge] mini systems that my [showing involvement/self-mention] boss helped me [showing involvement/self-mention] create which allow me [showing involvement/self-mention] to break my [showing involvement/self-mention] tasks down into smaller chunks. I can only say [sharing personal views/self-mention] that it has helped me [showing involvement/self-mention] and I [showing involvement/self-mention] feel [evoking emotions/evaluative lexis] a lot [modulating commitment to claims/booster] better [modulating commitment to claims/booster] within myself. So [logical reasoning/transition marker], I [showing involvement/self-mention] really [modulating commitment to claims/booster] do [modulating commitment to claims/booster] think [sharing personal views/attitude marker] that all students should [logical reasoning/cognitive directive] get a part-time job if not for the money, then [logical reasoning/transition signal] just for the extra skills that they can get while being paid to do so.

References

Afzaal, M., Imran, M., Du, X., & Almusharraf, N. (2022). Automated and human interaction in written discourse: A contrastive parallel corpus-based investigation of metadiscourse features in machine-human translations. SAGE Open, 12(4), 21582440221142210. doi: 10.1177/2158244022114.Search in Google Scholar

Ahmad, M., Mahmood, M. A., Siddique, A. R., Imran, M., & Almusharraf, N. (2024). Variation in academic writing: A corpus-based investigation on the use of syntactic features by advanced L2 academic writers. Journal of Language and Education, 10(3), 25–39. doi: 10.17323/jle.2024.21618.Search in Google Scholar

Al-Momani, K. R. (2014). Strategies of persuasion in letters of complaint in academic context: The case of Jordanian university students’ complaints. Discourse Studies, 16(6), 705–728. doi: 10.1177/1461445614546257.Search in Google Scholar

Altınmakas, D., & Bayyurt, Y. (2019). An exploratory study on factors influencing undergraduate students’ academic writing practices in Turkey. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 37, 88–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2018.11.006.Search in Google Scholar

Bacha, N. (2010). Teaching the academic argument in a university EFL environment. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 9, 229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2010.05.001.Search in Google Scholar

Bailey, D. R., & Almusharraf, N. (2022). A structural equation model of second language writing strategies and their influence on anxiety, proficiency, and perceived benefits with online writing. Education and Information Technologies, 27(8), 10497–10516. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11045-0.Search in Google Scholar

Berlanga, I., García-García, F., & Victoria, J. S. (2013). Ethos, pathos and logos in Facebook user networking: New “Rhetor” of the 21st century. Communicar: Scientific Journal of Media Education, 41(21), 127–135. doi: 10.3916/C41-2013-12.Search in Google Scholar

Birhan, A. T. (2021). An exploration of metadiscourse usage in book review articles across three academic disciplines: A contrastive analysis of corpus-based research approach. Scientometrics, 126, 2885–2902. doi: 10.1007/s11192-020-03822-w.Search in Google Scholar

Casanave, C. P. (2004). Controversies in second language writing: Dilemmas and decisions in research and instruction. The University of Michigan Press.10.3998/mpub.9691Search in Google Scholar

Chakorn, O. O. (2006). Persuasive and politeness strategies in cross-cultural letters of request in the Thai business context. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 16(1), 103–146. doi: 10.1075/japc.16.1.06cha.Search in Google Scholar

Connor, U. (2011). Intercultural rhetoric in the writing classroom. University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.3488851.Search in Google Scholar

Dickins, J. (2017). The pervasiveness of coordination in Arabic, with reference to Arabic > English translation. Languages in Contrast, 17(2), 229–254. doi: 10.1075/lic.17.2.04dic.Search in Google Scholar

Divsar, H., & Amirsoleimani, K. H. (2021). Developing voice in EFL learners’ argumentative writing through dialogical thinking: A promising combination. Journal of Language Horizons, 4, 145–166. doi: 10.22051/LGHOR.2020.28900.1210.Search in Google Scholar

Dontcheva-Navratilova, O., Adam, M., Povolná, R., & Vogel, R. (2020). Persuasion in specialized discourse. Palgrave Macmillan.10.1007/978-3-030-58163-3Search in Google Scholar

El Majidi, A., Janssen, D., & de Graaff, R. (2021). The effects of in-class debates on argumentation skills in second language education. System, 101, 102576. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102576.Search in Google Scholar

El-Dakhs, D. A. S. (2018a). Why are abstracts in PhD theses and research articles different? A genre-specific perspective. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 36, 48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2018.09.005.Search in Google Scholar

El-Dakhs, D. A. S. (2018b). Comparative genre analysis of research article abstracts in more and less prestigious journals: Linguistics journals in focus. Research in Language, 16(1), 47–63. doi: 10.2478/rela-2018-0002.Search in Google Scholar

El-Dakhs, D. A. S. (2020). Variation of metadiscourse in L2 writing: Focus on language proficiency and learning context. Ampersand, 7, 100069. doi: 10.1016/j.amper.2020.100069.Search in Google Scholar

El-Dakhs, D. A. (2022). Persuasion in health communication: The case of Saudi and Australian tweets on COVID-19 vaccination. In P. Hohaus (Ed.), Science communication in times of crisis (pp. 119–142). John Penjamins Publishing. doi: 10.1075/dapsac.96.06eld.Search in Google Scholar

El-Dakhs, D. A. S., Mardini, L., & Alhabbad, L. (2024). The persuasive strategies in more and less prestigious linguistics journals: Focus on research article abstracts. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 11(1), 2325760. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2024.2325760.Search in Google Scholar

El-Dakhs, D. A. S., Yahya, N., & Pawlak, M. (2022). Investigating the impact of explicit and implicit instruction on the use of interactional metadiscourse markers. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 7(1), 44. doi: 10.1186/s40862-022-00175-0.Search in Google Scholar

Fanani, A., Setiawan, S., Purwati, O., Maisarah, M., & Qoyyimah, U. (2020). Donald Trump’s grammar of persuasion in his speech. Heliyon, 6(1), e03082. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e03082.Search in Google Scholar

Ghanbari, N., & Salari, M. (2022). Problematizing argumentative writing in an Iranian EFL undergraduate context. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 862400. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.862400.Search in Google Scholar

Guo, K., Li, Y., Li, Y., & Chu, S. K. W. (2024). Understanding EFL students’ chatbot-assisted argumentative writing: An activity theory perspective. Education and Information Technologies, 29, 1–20. doi: 10.1007/s10639-023-12230-5.Search in Google Scholar

Hu, G., & Cao, F. (2011). Hedging and boosting in abstracts of applied linguistics articles: A comparative study of English- and Chinese-medium journals. Journal of Pragmatics, 43, 2785–2809. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2011.04.007.Search in Google Scholar

Hyland, K. (2005). Metadiscourse; Exploring interaction in writing. Continuum. doi: 10.1017/S0047404508080111.Search in Google Scholar

Hyland, K. (2007). Genre pedagogy: Language, literacy and L2 writing instruction. Journal of Second Language Writing, 16(3), 148–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2007.07.005.Search in Google Scholar

Hyland, K., & Zou, H. (2020). In the frame: Signalling structure in academic articles and blogs. Journal of Pragmatics, 165, 31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2020.05.002.Search in Google Scholar

Jacobs, C. (2005). On being an insider on the outside: New spaces for integrating academic literacies. Teaching in Higher Education, 10, 475–487. doi: 10.1080/13562510500239091.Search in Google Scholar

Kamimura, T., & Oi, K. (1998). Argumentative strategies in American and Japanese English. World Englishes, 17(3), 307–323. doi: 10.1111/1467-971X.00106.Search in Google Scholar

Kashiha, H. (2021). Metadiscourse variations in the generic structure of disciplinary research articles. International Review of Pragmatics, 13(2), 193–212. doi: 10.1163/18773109-01302004.Search in Google Scholar

Kawase, T. (2015). Metadiscourse in the introductions of PhD theses and research articles. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 20, 114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2015.08.006.Search in Google Scholar

Kobayashi, Y. (2016). Investigating metadiscourse markers in Asian Englishes: A corpus-based approach. Language in Focus Journal, 2(1), 19–35. doi: 10.1515/lifijsal-2016-0002.Search in Google Scholar

Krishnan, I. A., Lin, T. M., Ching, H. S., Ramalingam, S., & Maruthai, E. (2020). Using rhetorical approach of ethos, pathos and logos by Malaysian Engineering students in persuasive email writings. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 5(4), 19–33. doi: 10.47405/mjssh.v5i4.386.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, J. J., & Deakin, L. (2016). Interactions in L1 and L2 undergraduate student writing: Interactional metadiscourse in successful and less-successful argumentative essays. Journal of Second Language Writing, 33, 21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2016.06.004.Search in Google Scholar

Lee, J., & Lee, J. (2024). Development of argumentative writing ability in EFL middle school students. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 40(1), 36–53. doi: 10.1080/10573569.2022.2161438.Search in Google Scholar

Li, J., & Wang, J. (2024). A measure of EFL argumentative writing cognitive load: Scale development and validation. Journal of Second Language Writing, 63, 101095. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2024.101095.Search in Google Scholar

Majidi, A. E., Graaff, R. D., & Janssen, D. (2023). Debate pedagogy as a conducive environment for L2 argumentative essay writing. Language Teaching Research, 13621688231156998. doi: 10.1177/13621688231156998.Search in Google Scholar

Míguez-Álvarez, C., Varela, L. G., & Cuevas-Alonso, M. (2023). Identification of metadiscourse markers in bachelor’s degree theses in Spanish: Introduction of a text mining tool. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada/Spanish Journal of Applied Linguistics, 36(1), 329–351. doi: 10.1075/resla.20055.mig.Search in Google Scholar

Mohamad, H. A. (2022). Analysis of rhetorical appeals to Logos, Ethos and Pathos in ENL and ESL research abstracts. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), 7(3), e001314. doi: 10.47405/mjssh.v7i3.1314.Search in Google Scholar

Mutch, A. (2003). Exploring the practice of feedback to students. Active Learning in Higher Education, 4, 24–38. doi: 10.1177/1469787403004001003.Search in Google Scholar

Ozfidan, B., & Mitchell, C. (2020). Detected difficulties in argumentative writing. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, 7(2), 15–29. doi: 10.29333/ejecs/.Search in Google Scholar

Ozfidan, B., & Mitchell, C. (2022). Assessment of students’ argumentative writing. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, 9(2), 121–133. doi: 10.29333/ejecs/1064.Search in Google Scholar

Park, S., & Oh, S. (2018). Korean EFL learners’ metadiscourse use as an index of L2 writing proficiency. SNU Journal of Educational Research, 27(2), 65–89.Search in Google Scholar

Pérez-Echeverría, M. P., Postigo, Y., & García-Milá, M. (2016). Argumentation and education: Notes for a debate/Argumentación y educación: Apuntes para un debate. Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 39(1), 1–24. doi: 10.1080/02103702.2015.1111607.Search in Google Scholar

Perloff, R. M. (2010). Dynamics of persuasion: Communication and attitudes in the twenty-first century. Taylor and Francis. doi: 10.4324/9780429196959.Search in Google Scholar

Saprina, C. M., Rosyid, A., & Suryanti, Y. (2020). Difficulties in developing idea encountered by students in writing argumentative essay. Journal of English Language Studies, 5, 1–7. doi: 10.55215/jetli.v3i1.3419.Search in Google Scholar