Abstract

Translating puns in audio-visual content is challenging, as they are often humorous, are paired with visual cues that restrict translators’ creativity, and do not last long on the screen. This research article investigates the translatability of puns in the animated movie Shark Tale from English into Arabic in both its subtitled and dubbed versions. The data are qualitatively analyzed according to Aleksandrova’s (2019. Audiovisual translation of puns in animated films. The European Journal of Humour Research, 7(4), 86–105) Taxonomy, and it is found that the translators generally tend to ignore or avoid translating puns in a way that preserves both or one of the pun signs or at least raises a sense of humor. This avoidance can take the shape of Literal Translation or No Translation (omission). Nonetheless, the alternative translations provided by the researchers confirm that puns can be translated by accepting the game of translation using two different strategies: (a) Quasi-Translation where the translator preserves one of the signs of the original pun and replaces the other with a suitable one from the target language and (b) Free Translation where the translator replaces the two signs of the source pun with new signs from the target language. Additionally, it is found in this study that the identity and complexity of puns are involved in their translatability. Specifically, visual puns and complex puns, which are culturally very local, are subject to being ignored by No Translation (i.e., omitting the linguistic host of a pun). Concerning the relation between translation of puns and modes of translation, no difference in the quality of pun translation in the subtitled and dubbed versions is found. These findings imply that humorous and figurative language is difficult to deal with while transferring them into another language; yet, they are translatable. Therefore, translators should have a positive attitude toward it, as translating this language, such as puns, can be obtained by more than one technique (i.e., Free and Quasi) that could preserve or raise a sense of humor.

1 Introduction

Translation between theory and practice is highly branching. It may divide depending on the domain where it operates. In the current study, the main concern is audio-visual translation (AVT). According to Au (2009, p. vii), AVT is often described as “a discipline that is much more than the mere transfer of pictures, music, sounds, and other non-verbal elements …, making it a kind of multi-semiotic transfer.” Within the vast domain of translation, AVT has a large share in contributing to globalization and integrating different parts of the world.

AVT, such as translating movies and TV shows, has two main modes, which are dubbing and subtitling (Coelh, 2003). Dubbing is the process of replacing the original actors’ dialog on the soundtrack with a recording of the target language that reproduces the message, making sure that the target language actors’ sound and lips are perfectly synced with the original to give the impression that the dialog was made in the target language (Diaz-Cintas, 2009; Diaz-Cintas & Remael, 2014). On the other hand, Gottlieb (2004, p. 87) defines subtitling as “the rendering in a different language of verbal messages in filmic media in the shape of one or more lines of written text presented on the screen in sync with the original message.” It is often described as adding captions in a different language (interlingual) or within the same language (intralingual) to audio-visual (AV) content, such as a movie, with the ability to access the original text.

The primary concern of the current study is evaluating the quality of subtitling and dubbing of puns embedded in one AV content. It targets instances of puns in a particular English animated movie, Shark Tale. Here, it should be emphasized again that a pun, which is a figurative tool that creates phonetic and semantic ambiguity, is generally composed to create a sense of humor. Therefore, humor should be first defined. Defining humor is challenging; however, it is generally depicted in the relevant literature as an event between some interlocutors where one or more of the involved individuals are amused and treats the event as funny (Cooper, 2008; Gervais & Wilson, 2005; Martin, 2007; McGraw & Warren, 2010; Warren & McGraw, 2015). Amusement can take various forms, such as laughter. Here, it is reported in theories of humor that what causes particular reactions, such as laughter, cannot be straightforwardly stated. Humor is a universal tool that serves many functions; however, the nature of the function(s) that interlocutors employ may vary among cultures. For the sake of concreteness, it has been reported in the relevant literature that students from different countries tend to use different types of humor to serve different functions. For example, students from India use more self-enhancing humor, while students from Hong Kong use more self-defeating humor (Hiranandani & Yue, 2014; Yue et al., 2014). Thus, humor poses a problem to translators, whether it takes the shape of a pun, parody, irony, or any other form of humor. The process of transferring puns in AV content, which is the main concern of the current study, and at the same time preserving its sense of humor is extremely difficult (Zabalbeascoa, 2005).

In the relevant literature, there is an increasing body of research tackling the translatability of AV humorous content, including puns, from English to Spanish (e.g., Chaume, 2020), French (e.g., Diaz-Cintas & Remael, 2014), and Italian (e.g., Massidda, 2015), for example. Regarding Arabic, little attention is paid to the translatability of humorous content in the relevant Arabic literature pertaining to the English-Arabic and Arabic-English contexts. Far less attention is paid to exploring the domain of pun translatability of AV content in these contexts. Hence, the significance of the current study springs from the scarcity of studies tackling AVT of humor, specifically puns, in the Arab world. The qualitative discussions, findings, and conclusions should contribute to the shared (cross-linguistic) knowledge of the triggers, types, obstacles, and strategies of translating puns, which are typically humorous. The significance of this study is also rooted in the attempt to contribute to the theoretical framework that can explain and predict all the possible deliberate (or even undeliberate) decisions that a translator may make once facing a case of pun.

This study attempts to answer the following questions:

What are the types of puns that exist in AV content, particularly the English movie Shark Tale?

Do translators transfer English puns in AV content (particularly in the animated movie Shark Tale) to Arabic in a way that preserves their signs, and is there any difference in the translatability of puns by employing different modes of translation, namely subtitling vs dubbing?

2 Literature Review

2.1 Theoretical Background

AVT is a field of translation that emerged in the middle of the last century. Recently, it has been regarded as a well-known field of translation, as the cinema industry witnessed a spectacular rise at the end of the twentieth century after a slow and shaky beginning in the 1950s and the 1960s (King, 2000). Concerning AVT as a field of academic study, in the last few decades, the AV industry has served as a solid basis for a rapidly growing activity in the academic research of translating AV content. As for pun, which is a linguistic and figurative form of humor, its translatability is investigated in the domain of translation in general and in the AVT context in specific.

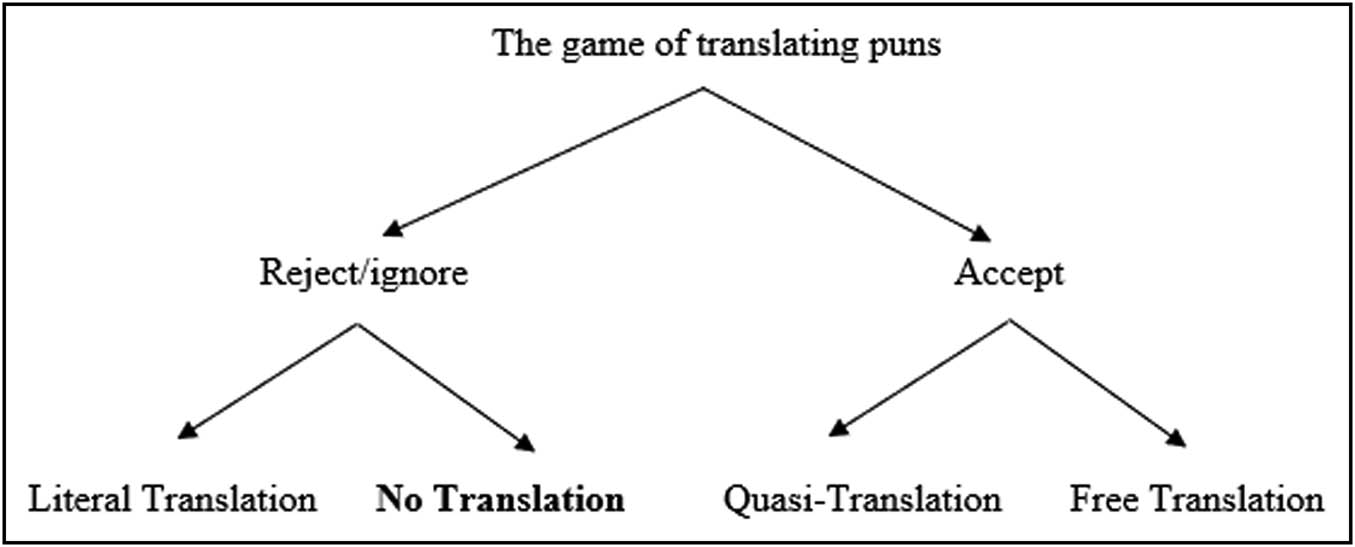

Aleksandrova (2019) proposes that translating puns is a cognitive game. Precisely, a translator may decline (ignore) the pun and its signs or accept it and once it is accepted, she/he will start thinking of a way to transfer it fully to the target language. This implies that declining the game of translating puns will hinder the translator’s creativity and any cognitive activities to process the pun. On the contrary, the acceptance of the game will unleash his/her creativity and many cognitive activities that may last for a long time to process the pun and its signs and transfer it in a particular way to the target language. For example, the translator may think of one sign or a pair of signs from the target language to substitute one or both signs of the source pun. Additionally, possible signs from the target language can be unconsciously retrieved while that translator is doing work other than dealing with the targeted pun.

Aleksandrova reports that translators of puns in AV content opt for one of the following general strategies: Literal Translation, Free Translation, and Quasi-Translation. Consider the following scenarios:

If the translator declines or ignores the cognitive game of pun translation, she/he will more likely focus on transferring the host of the pun, not the signs of the pun. This means that she/he opts for Literal Translation. Literal Translation is used when the original pun in the source language is transferable as is to the target language without distorting the denotation of the host of the pun (i.e., a word or phrase).

If the translator accepts the game, she/he can take one of the following pathways: (a) Free Translation creates a new pun in the target language to preserve a sense of humor, even if it is entirely different from the original one. This strategy is a form of compensation, yet pragmatic. The other pathway is (b) Quasi-Translation. It is an attempt to devise a pun in the target language but with the preservation of one of the signs of the original pun in the source language. This can be perceived as a process of linguistic and figurative hybridization (i.e., the resulting pun is expected to be conceptually a hybrid entity). More explanations and examples of these translation strategies will be provided whenever possible in Sections 3 and 4. For the sake of readers’ convenience, the scenarios of how translators deal with pun translation as a game, as proposed in Aleksandrova (2019), are schematized in Figure 1.

The game of translating puns.

2.2 Empirical Studies

Pun, as a figurative device, is often a carrier of humorous content, as is the case in AV content and, more precisely, in animated sources. Hence, puns are typically culturally bound and complex components that should be hard to translate. What emphasizes the difficulty of translating puns is that the one-to-one equivalence between languages (or the sameness of components) can be scarcely guaranteed (Delabastita, 1996, p. 133). As a result, the direct transference of puns and other humorous and figurative devices is not the optimal technique. Instead, paying more cognitive effort, reading more about the figurative and humorous components of other cultures, and paying more time are in great demand to obtain better translations that preserve the semantic and pragmatic content of a source token. This, in turn, indicates that translators should go beyond simple words and focus on contextual clues and cultural specifications, as suggested in Attardo and Raskin’s (1991) General Theory of Verbal Humor.

Translating humorous and pragmatic content, in general, has been the main concern in a body of studies that make use of the linguistic approach (including but not limited to Attardo, 2002; Ritchie, 2004; Vandaele, 2001; Yus, 2016). Concerning AVT of such content, it has been reported in the relevant literature that there are more hurdles that translators need to deal with, specifically the mode of translating AV content, whether subtitling or dubbing. In this relevant literature, more than one approach has been put forth, including (a) the application of Relevance Theory, such as Díaz-Pérez (2014) and Martínez Sierra (2009), where the dubbing of humorous and figurative tokens are investigated, and (b) the implementation of functional translation to such content in animated comedies, such as Mendiluce and Hernández (2004). Some other studies focus on the cultural limitations while translating such content, as in Díaz Cintas (2001). Since the English context pertains to the current study, the humorous content in the following animated movies is one of the main concerns in the relevant literature: Madagascar: Escape to Africa (Winarti, 2011) and Hotel Transylvania 2 (Auliah, 2017). The main and most relevant conclusion in such studies and similar relevant studies is that figurative and humorous tokens, specifically puns and wordplay instances, are typically ignored by literally translating or omitting them. This should imply that translating humorous figurative tokens is challenging to translators, as it is, maybe, time-consuming and cognitively hard to treat.

Regarding English-Arabic and Arabic-English contexts, almost no previous studies tackle the issue of the translatability of puns in the AV content to the best of the researchers’ knowledge. Below, a recent study that explores this issue in non-AV content is reviewed.

Mehawesh et al. (2023) explore the obstacles translators face while transferring English puns into Arabic in some English novels. The researchers found out that a non-trivial number of cases are inadequately translated into Arabic, leading them to suggest strategies to better translate puns.[1] They report that the main problems of the source English pun are mainly at the interface between sound and meaning. Particularly, phonetically based English puns do not have the same phonetic representation and meaningful message in Arabic. For instance, the researchers reported that the pair long tale vs long tail that is used as a case of homophonic pun in Alice Adventures in Wonderland in “It is a long and a sad tale! … It is a long tail, certainly,” is translated literally. As a result, the source homophony and the humoristic sense that it promotes in English are lost in the Arabic translation and are not compensated. One of the strategies provided by the researchers to deal with such a problem is to make a shift in the semantic field. For example, the pair axis vs axes in “You see the earth takes twenty-four hours to turn round on its axis” and “Talking of axes … chop off her head” from Alice in Wonderland is translated literally into Arabic, resulting in losing the phonetic resemblance and the humoristic sense that this resemblance evokes in the source text. To compensate for the meaningful and humoristic loss, the image of chopping off a head in the source English text is replaced with the image of spinning (of a rope) around a nick. Although the sense of humor is evoked in the researcher’s translation, the original pun is lost and is not replaced with one from the target language. At any rate, this translation is less harmful to the source text and is far better than Literal Translation that ruins the figurative and humorous content of the source token. Another possible strategy employed in their study is to provide a footnote explaining the figurative and humorous message of the source pun; however, explaining the humorous content will not necessarily or most likely cause the laughter of the target audience. Replacing the source pun with a pun from the target language is reported one time in their study, showing that this task is possible but difficult and needs more cognitive effort from translators who deal with figurative and humorous texts.

Hence, little effort, to the best of the researchers’ knowledge, has been put to investigate the translation of puns from English into Arabic and vice versa, and even less or no effort is paid to the translatability of puns in the AV content. However, what can be inferred from the relevant literature, in general, is that there is a common tendency that translators are often reluctant to treat cases of humorous figurative language and may ignore them by Literal Translation or omission, although it is reported in several theoretical studies that such language is translatable in a way that preserves its semantic, pragmatic, and humorous sense. Adopting Alexandrova’s Taxonomy, the current study shows that such language is translatable; yet, it needs cognitive effort, more readings, and time.

3 Methodology

This section presents the method and procedures adopted to collect, qualitatively analyze, and evaluate the tokens of puns in the movie Shark Tale. The main objective is to explore how pun is translatable and, at the same time, how this process is a cognitive game that can be declined or accepted by translators. Once accepted, it will be translated; however, the way it is translated may differ from one translator to another.

3.1 Why Animated Movies?

From a pragmatic viewpoint, animated movies are rich in humorous expressions that are expected to be challenging to translate. Therefore, such expressions are usually omitted or translated in a way that may lead to connotative and humorous loss. Animated movies typically target young audiences interested in humorous actions and expressions; thus, rendering humor incorrectly can be confusing and incomprehensible in some cases. The animated movie Shark Tale was chosen since it is rich in various humorous expressions and actions related to sea life, where different puns and jokes are made by playing with words to relate everything to the reef where the characters live. Translators may have difficulty finding the correct equivalence when rendering these expressions, such as those related to celebrities’ names and famous places.

3.2 Study Procedures

First, the English tokens are sorted according to the following classification of puns: (1) paronymy, (2) homonymy or polysemy, and (3) homophony. Second, the researchers evaluate the Arabic subtitling and dubbing of the English tokens of puns.

Puns are often classified into the following types (note that these types are semantic relations between words that are phonetically identical or similar):

Homonymy: it can be defined as two (or more) words that are orthographically and phonetically identical (Lyons, 1982), such as right1 “true or correct” and right2 “one of the two sides.”

Polysemy: it means that one single word can have more than one meaning (Nunberg, 1979). For example, the verb get may mean “obtain or have,” “become,” or “understand” as in the following sentences, respectively: (1) I’ll get the drinks, (2) she got scared, and (3) I get it. Note all the previously mentioned puns in this section constitute paronymic pairs, such as Kelpy kremes which is the paronym of Krispy kremes.

Homophony: it refers to two (or more) words that are phonetically identical but orthographically different (e.g., see vs sea) (Bréal, 1904).

Homography: it refers to cases where two (or more) words are phonetically identical but orthographically different (e.g., right/raɪt/and write/raɪt/) (Dijkstra et al., 1999).

Paronymy: it is another semantic relation that refers to two (or more) words that exhibit a slight phonetic and orthographic difference in sound and spelling, such as the difference between symbol and cymbal “musical instrument” (Valera & Ruz, 2021).

Note that in the relevant literature, the types of puns may show some variation. In Delabastita (1996), polysemy is not listed as a form of pun. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that any cases of homography, if any, are out of the scope of the current study, as the focus of the article is on oral content, making the relevance of orthography-based items less evident.

For the sake of concreteness, one case of pun extracted from Shark Tale, namely shell phone, is discussed below. Consider the substitution of a cell phone with its phonetic paronym, shell phone. Shell is used since this film is about sea life. The phonetic aspect of such an example in English, specifically the shared rhyme of cell and shell (i.e., it is an example of paronymy), is challenging to transfer to the target language (Arabic). More specifically, the two signs of the pun cannot be dropped as they are in the Arabic text, as the Arab audience will not fully comprehend this pun. Therefore, it will not leave the same humorous impact on Arab native speakers as it leaves on English native speakers. Here, in the Arabic subtitled version of the movie, the translator strives to transfer the humor and pun in this example, and she/he successfully transfers the direct meaning, humor, and pun altogether. To illustrate, the original pun, which is the pair cell phones vs shell phones, is substituted with the paronym ʔal-hawaatif ʔas

ʕ

-s

ʕ

adafijah “shell phones,” which relatively rhymes with ʔal-hawaatif ʔað-ðakijjah “smartphones.” Hence, this attempt to translate pun, deliberately or accidentally, is semantically and pragmatically adequate.

Each token of a pun from the original movie, as exemplified below, is investigated independently. The criteria of evaluation that have been conducted by the three researchers include the following:

To determine the type of pun each English token embeds.

To decide whether the figurative and humorous loads are also maintained in the translation.

To diagnose the preservation of one or both signs of each English pun in the Arabic translation.

If both signs are preserved, the following step will determine whether this full or partial figurative preservation has a humorous load in the target language.

Another possible scenario is that one of the two signs of a pun is preserved, and the other is altered by an Arabic counterpart. In this case, the role of the researchers is to check the pragmatic efficiency of the preserved sign and the alternative sign. Are they regarded as humorous?

If both signs are not preserved and replaced by Arabic signs (i.e., the English pun is replaced by an Arabic pun), their suitability to raise a sense of humor is also checked.

Another possible scenario is that the translator ignores the English pun signs. In this case, the question that should be answered is the following: does she/he literally translate the pun or omit it? Whether it is literally translated or ignored, it is expected that no pragmatic or humorous load will be in the target text unless the Literal Translation accidentally preserves a sense of humor. This is because it is possible that English and Arabic share a pun or the English pun is not language specific (e.g., it could pertain to a universal experience among human beings).

Whenever possible, the researchers may suggest alternative translations of puns unless the Arabic translation is efficient in securing a humorous and figurative load.

As noted earlier, Aleksandrova’s (2019) model of rendering puns, namely Literal Translation, Free Translation, and Quasi-Translation, is used.

Following Aleksandrova’s (2019) Taxonomy of the translation strategies of puns as a cognitive game, this translation is Quasi-Translation, which means that one of the two signs of the English source pun is maintained in the Arabic translation. Specifically, the shell is preserved by its Arabic equivalent ʔasʕ-sʕadafijah, but the cell is replaced with ʔað-ðakijjah “smart.” Note that ʔal-hawaatif ʔal-xalawijjah “cell phones” seem to be odd or less frequent in Standard Arabic. However, if ʔal-hawaatif ʔas ʕ -s ʕ adafijah rhymes with ʔal-hawaatif ʔal-xalawijjah, this entails that the two signs of the English source pun are preserved in Arabic, and therefore, it should be treated as Literal Translation. At first glance, the translator pays no attention or effort to signs of the source pun (i.e., it ignores these signs); yet, it is possible that she/he realizes that the Literal Translation will be efficient in transferring the signs of the pun to Arabic, as both languages seem to have similar signs (maybe by coincidence).

Based on such an example of analysis, pun is transferable; yet, the translator decides to accept the game of translating it (by finding a Quasi-Translation or Free Translation to it) or declining it, which is what makes us sometimes feel that it is impossible to transfer it the target text (to another language). It is a matter of hinder or unleashing cognition and creativity.

4 Findings and Discussion

This section starts with the qualitative analysis of the puns collected from the animated movie Shark Tale and evaluates the quality of their Arabic translations in their subtitled and dubbed versions. In Section 4.2, it is shown that puns are translatable. Nonetheless, its translatability depends on the translator’s decision whether to take the responsibility of transferring the pun to another language or leave (ignore) it.

4.1 Findings

In Table 1, the total number of the collected pun tokens, the number of tokens that belong to the same type of pun, and the translation strategy are offered:

Total number of puns, types of puns, and their translation strategies

| Total number of pun tokens | Paronymy | Homonymy | Homophony | Translation strategy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subtitling | Dubbing | ||||

| 11 | 7 | 3 | 1 | Literal Translation (11) | Literal Translation (9) |

| No Translation (2) | |||||

Below, the collected puns from Shark Tale are sequentially analyzed. In this section, the selected puns from the subtitled version will be analyzed according to Aleksandrova’s (2019) Taxonomy either by accepting the game of pun translation by using either (a) Quasi-Translation or (b) Free Translation or (c) by rejecting the game by using Literal Translation.

4.1.1 Pun 1: Snap Your Fin

Snap your fin is a pun involving two homonymous words, which form the two signs of the pun: fin 1 (of a fish) and fin 2 (the abbreviated form of finger) (Table 2).

Subtitling and dubbing snap your fin by Literal Translation

| 00:12:02 | ||

|---|---|---|

| English token | Subtitling | Back Translation |

| Oscar: Hey, baby, this is all gravy today. Now snap your fin, etc. | اضرب زعنفتك | Hit with your fin! |

| Dubbing | Back Translation | |

| ضع زعنفتك في زعنفتي | Put your fin in my fin. | |

Following Aleksandrova’s (2019) typology of how a translator could react to a particular pun, the two translations of snap your fin above point to the translators’ denial of pun translation by providing non-pun translations. More specifically, the English pun (or at least one of its signs) may be given little or no time and mental effort by the translators to be transferred into Arabic (i.e., the translators ignore them to save their time). The other scenario is that it is given some time and effort, yet the signs of the pun are not transferable to Arabic (i.e., the linguistic/phonetic relation between fin 1 “finger” and fin 2 “part of fish body” is non-existent in Arabic). Moreover, finding an alternative pun or one of its signs in Arabic (i.e., Free Translation or Quasi-Translation) is also difficult.

Following Aleksandrova’s Taxonomy, it is a case of Literal Translation, which gets rid of puns and preserves the literal meaning of the source content. In other words, it is carried out by replacing the English pun with a contextually plausible non-pun translation, albeit humorous. Note that the translation of the pun in the dubbed version is not away from Free Translation, although يد jadd “hand” and زعنفة zuʕnufah “fin” are not phonetically related. In other words, the dubbing alludes that there is a sort of figurative sense at the sentential level.

It is worth highlighting that the translators, maybe, did not reject or ignore translating the pun. It is possible that they accepted it and thought of a way to translate it by Quasi-Translation or Free Translation; however, they could not find adequate signs in Arabic. This implies that rejecting pun translation can be sometimes inevitable, not elective, by the translator.

4.1.2 Pun 2: Bring My Clams

As shown in the conversational turn in Table 3, the word clams can also be regarded as a homonymous pun. It is the first sign of a homonymous pair if the English lexicon has two words that are phonetically and orthographically identical, namely clams 1 “sea creatures” and clams 2 “dollars.” In other words, homonymy is yielded if the intuition of English native speakers indicates that clams 1 and clams 2 are two lexemes (two different lexical entries). Note clams 2 “dollars” exists in English slang. On the other hand, this pun is a case of polysemy (more accurately, a bisemous word) if the intuition of English native speakers indicates that English has only one word (one lexeme) with two possible meanings, sea creatures vs dollars, and the intended meaning is determined concerning contextual factors.

Subtitling and dubbing clams by Literal Translation

| English token | Subtitling | Back Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Sykes: That’s your problem. Bring my clams to the track tomorrow, or else, etc. | احضر بطليونستي غدا الى الحلبة | Bring my clams tomorrow to the track |

| Dubbing | Back Translation | |

| احضر دولاراتي غدا الى الحلبة | Bring my dollars tomorrow to the track |

As shown in Table 3, the word clams is used by the character Sykes, Oscar’s boss, to refer to the money Oscar owes to him. Therefore, it does not refer to sea creatures in the context. Nevertheless, this word is literally translated to Arabic in the subtitled version, entailing that the intended semantic and pragmatic meanings of this token are not transferred to Arabic. This means that, besides the loss of the English pun and the sense of humor, the Literal Translation using the Arabic name of the sea creature بطلينوس bat ʕ linoos “clam,” as shown in Table 3, cannot give rise to the meaning of money (i.e., it is entirely unfaithful to the denotation and connotation of the word).

Concerning the translation strategy of this pun, the translator ignores/denies the English pun, as she/he literally translates the homonymous or bisemous clams to Arabic (Literal Translation). Particularly, the word hosting the pun is transferred as it is, without considering the transferability of the pair of signs that promote a sense of humor among spectators. Thus, this translation, which is an example of Literal Translation, is an example of total denotative, connotative, and figurative loss.

On the other hand, the translation strategy opted for the dubbed version, in Aleksandrova’s terms; it is also Literal Translation, which is in the form of non-pun translation.

Here, the Arabic قروش quruuʃ is suggested, as can serve the function of replacing the English source pun. It forms with its identical counterpart a case of homonymy, namely quruuʃ 1 “sharks” and quruuʃ 2 “piasters.” In this case, the translation strategy of pun is Free Translation which involves replacing the pair of English homonyms with a pair from Arabic. This asserts that the translation of a pun is just a game, as proposed in Aleksandrova. It can be rejected (right away or after the initial diagnosis of its signs) or accepted. If it is accepted, that will get the translator involved. It will stimulate thinking and help in finding a pair of signs of an alternative pun in the target language.

(1) احضر قروشي غدا الى الحلبة

Back Translation: “Bring my sharks tomorrow to the track.”

It is worth noting that the previous discussion points to a cultural gap between English and Arabic in terms of transferring the humorous load of slang words, such as words referring to money. Thus, the role of the translator is to search for an instance of a pun in the target language that can serve a similar function to the pun in the source language. Note that such a gap does not exist in languages sharing the same pun (the same signs). For example, this gap is not reported in Brotons (2017), where clams are translated into the Spanish dubbed version of Shark Tale, as it delivers the denotation and the humorous content to the Spanish audience. This is because the Spanish equivalent of clams is also used as slang for money. On this basis, Literal Translation, in Aleksandrova’s terms, is the best candidate to properly transfer all the components of the source token to the other language. Paying more cognitive effort to create Quasi-Translation or Free Translation in Spanish and spending much time on this attempt is not necessary, and the resulting translations are expected to be of low quality when compared to Literal Translation.

4.1.3 Pun 3: I Am a Wiener

I’m a wiener is a case of paronymy (paronymic pun). To illustrate this pun, wiener, which means sausage, is phonetically related to winner. These two words, which are the two signs of the pun, have identical rhymes. This phonetically related pair is created on the lips of the characters Bernie and Ernie, two jellyfish. It is a witty pun to parody what the female character Lola says to Oscar, who loves her when she realizes he is poor. Wiener, instead of winner, used to be in opposition with nobody in the dialog in Table 4.

Subtitling and dubbing wiener by Literal Translation

| 00:22:36 | ||

|---|---|---|

| English token | Subtitling | Back Translation |

| Bernie: Oscar, you are cute, but you’re a nobody | انا متذمر | I am grouchy. |

| Ernie: Wait. Lola. Come back. I’m not a nobody. I’m a wiener | Dubbing | Back Translation |

| انا شخص جبان | I am coward. | |

Regarding the transfer of the witty pun, all the previous translations are Literal Translation. This means that a translator, if she/he accepts the game of pun translation, should think of alternating one of the signs (Quasi-Translation) or both signs (Free Translation) of the source pun from the target language, Arabic, but let us assume that the Arabic word naqaaniq “sausages” is used in the translation (i.e., Literal Translation). Watching wieners on the screen while performing this dialog would make it easy for the Arab audience to understand why this Arabic word is used. However, it would be challenging, if not impossible, to understand the witty pun of the English pair wiener vs winner. On this basis, being informative should be prioritized over being humorous. Therefore, عظيم الفائدة ʕadiim ʔal-faaʕidah should be selected when transferring or replacing the pun is difficult or even impossible. Thus, the translator’s denial or negligence of the English pun is explainable: the denotation is more critical than the pragmatics of the pun to keep the Arabic audience engaged. Prioritizing the pun may lead to a problem in semantic transfer and confusion. This entails that the level of difficulty of the pun is not the only reason a translator may abandon the pun. The cause of the abandonment could be the sake of preserving the direct meaning and avoiding awkward translations. Another reason for the denial is that the pun is visual. Therefore, it is so difficult to replace the original pun with another one in Arabic, as the image of the wieners, or sausages, will block the use of new pun signs in Arabic. In other words, manipulating the signs to come up with Quasi-Translation or Free Translation is visually constrained.

As noted in the discussion previously, the translator should put more effort into finding a pun in the target language to compensate for the original pun. For example, let us assume that the intended meaning of wiener in the English movie is “coward.” Once the game of pun translation is accepted, a pun in Arabic surfaces, which is the homonymous case of dʒubn 1 “cowardice” and dʒubn 2 “cheese.” Thus, we suggest that I am a wiener can be translated as انا نقانق معروفة بالجبن ʔana naqaaniq maʕruufah bidʒdʒubn “I am a sausage known for cowardice (not cheese).” Note that the strategy for translating the pun here, in Aleksandrova’s terms, is Free Translation. The English pun is replaced with an Arabic one without preserving any of the two signs of the English pun (wiener vs winner). Again, this translation emphasizes that pun translation is just like a game: each instance of a pun has its peculiarities that may help or hinder a translator from rendering it fully into another language. Moreover, the translator decides to reject the game (of pun translation) or accept it. The rejection hinders any cognitive processes, whereas the acceptance boosts cognition and makes the translator take it personally.

4.1.4 Pun 4: Plankton Encrusted

Plankton-encrusted teeth is a complex pun. It embeds a paronymous pair and a homonymous pair. Plankton is a paronym (the phonetically related substitute) of plaque in the scene where Oscar is cleaning a whale’s mouth, which is full of plankton and seaweed. In this sense, the plankton on the whale’s teeth, which is a referent chosen from sea life, is humorously treated as if it is tooth plaque. Further, the word encrusted establishes the homonymous relation between plaque 1 “dental plaque” and plaque 2 “painting.”

In the Arabic subtitled version, the pun is literally translated, and the word encrusted is literally transferred, as the back translation and the glossing tier are shown in Table 5.

Subtitling plankton-encrusted by Literal Translation

| 00:10:48 | ||

|---|---|---|

| English token | Subtitling | Back Translation |

| Oscar: Welcome to Oscar’s crib – foot slime-covered tongue with canker sores, swim-in cavities, plankton-encrusted teeth, etc. | محشوه بالبلانكتون | Encrusted with plankton |

| Dubbing | Back Translation | |

| مرصعه بالطحالب | Set with plankton | |

In the Arabic dubbed version, the entire token plankton-encrusted is literally translated, as shown in Table 6. A point worth discussing is that مرصعة muras ʕ s ʕ aʕah, the Arabic equivalent of encrusted in the dubbed version, is semantically more suitable than maksuwwah in the subtitled version. مرصعة muras ʕ s ʕ aʕah, just like encrusted, gives the impression that what is set is precious, unlike the neutral expression مكسوة maksuwwah, which is synonymous with the English word clothed. Then, the word encrusted should be translated as مرصعة muras ʕ s ʕ aʕah, as the pun in the English movie involves the homonymy of plaque “dental plaque” and plaque “painting.” In other words, plaque-encrusted is more likely to create a humorous contrast between a mouth that is full of dental plaque and a painting encrusted with something precious.

Dubbing plankton-encrusted by Literal Translation

| 00:11:30 | ||

|---|---|---|

| English token | Dubbing | Back Translation |

| Oscar: Welcome to Oscar’s crib – foot slime-covered tongue with canker sores, swim-in cavities, plankton-encrusted teeth, etc. | مرصعه بالطحالب | Set with plankton |

The previous discussion implies that the translators refrain from transferring the complex pun or finding/creating another pun in Arabic (i.e., it is the Literal Translation of pun by focusing on the denotation of the source content). Alternatively, they may compensate for the missing pun by adding a sea element.

Here, in Arabic, the bisemous (or homonymous) مرجان mardʒaan which may refer to coral, a sea element, or small stones of pearl is suggested. If this word is added to the Literal Translation in the dubbing version, it is more likely perceived as a case pun by Arab viewers. Following Aleksandrova’s (2019) Taxonomy of translating puns as a game, this translation of pun is a case of Free Translation. Specifically, the English homonymous pair plankton and plaque are replaced with the Arabic bisemous مرجان mardʒaan “coral” or “small stones of pearl” (or homonymous مرجان mardʒaan 1 “coral” مرجان mardʒaan 2 “small stones of pearl”). A point worth discussing is that the pun of plankton-encrusted is fortified with visual cues (the scene of the whale’s mouth). Specifically, the scene shows that the mouth is full of plankton, not coral. Hence, replacing the signs of the paronymic source pun plankton vs plaque with the Arabic homonymous signs مرجان mardʒaan 1 “coral” vs مرجان mardʒaan 2 “small stones of pearl” can be constrained or blocked by these visual cues, as the audience may figure out this difference between the scene and the translation. This implies that visual cues, as expected, tend to hinder or block Free Translation, as one of the pun signs is visible in the scene. Note that Quasi-Translation is still an available option; yet, it is challenging due to the visual constraint.

4.1.5 Pun 5: Shell Phone

Shell phone is a paronymic pun that belongs to sea life. It is the phonetic substitute for cell phone. In the subtitled version, according to Alexandrova’s terms, the subtitling of this pun is an example of Literal Translation. It seems that the translator does not accept the game of pun translation, but the Literal Translation coincidently transfers the signs of puns to Arabic. Note that the signs are preserved, yet they are not transliterated into Arabic letters. Instead, they are replaced with the Arabic equivalents, and this implies that the referents (the signified, in Saussure’s terms) are maintained yet the English paronymic words (the signifiers) are replaced. The second possibility is that the translator is aware of the paronymic pun in the source token and finds that Literal Translation is more adequate than Quasi-Translation or Free Translation to naturally transfer the original pun. Note that the existence of some cultural resemblances (i.e., both languages use the same pun or at least one of its signs) makes Literal Translation optimal (Table 7).

Subtitling shell phones by Literal Translation

| 00:03:03 | ||

|---|---|---|

| English token | Subtitling | Back Translation |

| [Katie]: Up next, a mother of 800 tells us how she does it all | الهواتف الصدفية | The shelled phones |

| [News reporter]: Thanks, Katie. Slight congestion here on the Inter Reef 95. There’s an overturned mackerel. Authorities are trying to calm him down. Get out those shell phones and call the boss | Dubbing | Back Translation |

| اتصلوا برب اعمالكم | Call your bosses | |

In the dubbed version, the strategy used is omission. For example, consider the back translation in Table 8. This strategy entirely neglects the humorous load (including the case of paronymy), leaving no sense of humor for the Arab audience. Thus, the Literal Translation in the subtitled version incurs less damage to the semantic and pragmatic content of the original item.

Dubbing shell phones by No Translation

| 00:03:34 | ||

|---|---|---|

| English token | Dubbing | Back Translation |

| [Katie]: Up next, a mother of 800 tells us how she does it all | اتصلوا برب اعمالكم | Call your bosses |

| [News reporter]: Thanks, Katie. Slight congestion here on the Inter Reef 95. There’s an overturned mackerel. Authorities are trying to calm him down. Get out those shell phones and call the boss | ||

Regarding omission in the dubbed version, it should be taken as No Translation, which clearly indicates that the translator deliberately ignores the pun, its signs, and all of its traces in the source text. In other words, the phrase shell phone is totally and intentionally omitted. On this basis, it seems that the best pathway that should be taken to translate this pun is to avoid paying cognitive efforts and time to come up with Quasi-Translation (preserving one of the source signs and replacing the other) or Free Translation (replacing both signs). In other words, ignoring the pun, even if it is intentional, is sometimes, and by coincidence the right decision. Such a coincidence maximizes the feasibility of translating puns in an efficient way and casts doubts on the falsifiable generalization of the non-translatability of puns.

4.1.6 Pun 6: Don Lame-o

The pun in the name Don Lame-o is complex. The real name Don Lame-o means stupid in slang English (Brotons, 2017). Therefore, it is a paronym of the actual name of the mob boss, the shark Don Lino. There is another type of pun in this name, homonymy. Don is the abbreviation of Donald, the first name of the mob boss. It can also carry another interpretation, the Spanish title prefix Don, as Don Lino is a boss.

In the subtitled version, Don Lame-o is literally translated. This transfer would entail that the humorous load is not transferred to Arabic, as the majority of the Arab audience cannot capture the cultural reference Don Lame-o, which means stupid in English slang. Regarding the homonymy of Don 1 “the abbreviation of Donald” and Don 2 “a Spanish title,” it is possible that some Arab viewers can grasp this pun if they know that Don is the abbreviation of Donald in the name Don Lino (Table 9).

Subtitling Don Lame-o by Literal Translation

| 00:55:18 | ||

|---|---|---|

| English token | Subtitling | Back Translation |

| Oscar: Yeah, and you tell Don Lame-o that I don’t never, ever, ever, never, want to see another shark on this reef again. Ever | الدون لينو | Don Lameo |

| Dubbing | Back Translation | |

| الضعيف لينو | Lino the weak | |

Concerning the dubbed version, the translator opts for Literal Translation, as shown in Table 12. However, the intended meaning of Don Lame-o is not to indicate that Don Lino is weak but stupid. This entails that this strategy is not efficiently used by the translator, as the meaning of the dubbed version is different from the denotation of the original version. Besides, the paronymy of Don Lino vs Don Lame-o and the homonymy of Don is lost.

On this basis, all the previous translations are examples of Literal Translation that ignores translating the signs of the pun, in Aleksandrova’s terms.

Quasi-Translation of a pun (i.e., preserving one of the signs in the original pun in the translation and replacing the other from the target language) is practically possible and pragmatically efficient, such as using the word ليمون lajmuun “lemons,” instead of lame-o in الدون ليمون al-doon lajmuun. ليمون lajmuun, in this translation, is expected to be treated by Arab viewers as a kind of paronymy (Don lino vs الدون ليمون ʔad-doon lajmuun) to mock Don Lino, i.e., it can (but not necessarily) be interpreted by Arab viewers as a sign of cowardness. Note that this case of paronymy is hybrid. Specifically, the Arabic word lajmuun is the derivative of the non-Arabic word Lino. That indicates that a pun’s Quasi-Translation is a real possibility and a useful tactic, but it requires the translator to accept the game of pun translation first. This translation indicates that the probability of rendering the pragmatic (humorous) and figurative load by Quasi-Translation would be greater if the target language shares more cultural grounds with the source language. In Brotons (2017), for example, it is reported in the Spanish dubbed version of the original movie Shark Tale that the translator successfully transfers the humorous and figurative loads (the pun) of Don Lame-o to the Spanish audience. This transference is attained by Quasi-Translation, following Aleksandrova’s, as follows: the Spanish paronym Don Limpio, a commercial brand of a famous cleaning product in Spain replaces Don lame-o. This substitution indicates that one of the signs of the English pun, which is Lino, is maintained and the second, Lame-o, is replaced with Limpio. Hence, the translator finds a humorous Spanish paronym of the English Don Lino to disparage the character.

4.1.7 Pun 7: Kelpy Kremes

Kelpy Kremes is another pun in the movie, which should be treated as both an oral and visual pun at the same time, as it is used in a dialog, as shown in Table 10, and is visible in the scene (on-screen). Note that this is the first case of visual puns in this section.

Subtitling Kelpy Kremes by Literal Translation

| 00:07:56 | ||

|---|---|---|

| English token | Subtitling | Back Translation |

| Oscar: l brought you some breakfast | دونات كيلبي كريمز | Kelpy Kremes Donates |

| Angie: You didn’t. Kelpy Kremes? | Dubbing | Back Translation |

| كلبي كريمز | Kelpy Kremes | |

Kelpy Kremes is the paronym derived from Krispy Kreme, an American doughnut company and coffeehouse chain. It is a combination of (1) kelpy, the substitute for Krispy, which refers to a spirit in the form of a horse that likes to drown its riders, and (2) Kremes, the plural of the second word in the brand Krispy Kreme (Brotons, 2017).

In both translations, the part of the source text containing the pun, according to Aleksandrova, is literally translated (i.e., Literal Translation), which neither preserves the signs of the pun nor the sense of humor. On this basis, the game of pun translation is rejected by the translators in the subtitled and dubbed versions. It seems that it is rejected because it is a visual pun, which either is regarded as a constraint that blocks Free Translation (replacing the signs of the source pun) or is left for the audience to be comprehended.

Free Translation can be an optimal candidate. Specifically, the original pun can be replaced as follows: a sea element can be used in the Arabic translation, such as tuunats, the blended derivative of tuuna “tuna” and donats “donates.” This Arabic paronymy, which replaces the paronymy of the original pun, along with the loan of Krispy Kreme (i.e., transliterating Krispy Kreme in Arabic) resulting in كرسبي كريم توناتس Krispy Kreme tuunats, conveys the direct meaning, compensates the original pun, and maintains a sense of humor in the target language, Arabic. At first glance, Quasi-Translation should be more appropriate than Free Translation to translate kelpy kremes, as this pun is visual. However, it is difficult to find a name of a sea creature or referent in Arabic to replace the word Krispy and be phonetically related to it. Thus, Free Translation is adequate even if it may cause some confusion, as kelpy kremes are visible to the target audience in the scene. Hence, visual puns could be problematic; yet, Free Translation can be employed in this case.

4.1.8 Pun 8: Names of Some American Celebrities

The screenwriter parodies the names of some American celebrities by blending their names with those of some sea creatures. This parody produces the following phonetically related paronymic pairs: Tina Turner vs Tuna Turner, Russel Crowe vs Mussel Crowe, Jessica Simpson vs Jessica Shrimpson, and Rod Stewart vs Cod Stewart. Tuna Turner is literally translated in the subtitled version, as Tuna is a loan word in Arabic. Likewise, the last names Crowe and Stewart and the first name Jessica are all directly transferred to Arabic, whereas Mussel, Shrimpson, and Cod are translated into Arabic. On this basis, the target names have been subtitled in the same way; it is either the first name or the last name transferred as it is in the Arabic translation, and the other member is literally translated.

Tuna is a loan word in Arabic, and the meaning of the word shrimp is well-known among Arabs. Therefore, the Literal Translation of Tuna Turner and Jessica Shrimpson could convey the humorous load (paronymy) of these phonetically related pairs, especially for Arabs familiar with the names of those American celebrities. On the other hand, the Arab audience is unfamiliar with the meanings of Mussel and Cod. Thus, they are literally translated (Table 11).

Subtitling names of American celebrities by Literal Translation

| Subtitling 00:02:39 → 00:02:45 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dubbing 00:03:05 → 00:03:11 | ||

| English token | Subtitling | Back Translation |

| Starfish | ||

| Tuna Turner | تونا تيرنير | Tuna Turner |

| Mussel Crowe | بلح البحر كرو | Crowe, the mussel |

| Jessica Shrimpson | جيسيكا القريدسية | Jessica, the shrimp |

| Cod Stewart | القد ستيورت | Stwart, the cod |

On the contrary, all these names are omitted in the dubbed version for no apparent reason. This omission means that the translator of the dubbed version ignores the signs of puns and deletes their traces; therefore, this decision should be considered No Translation, in Aleksandrova’s terms. Here, it should be highlighted that the translator in the subtitled version opts for Literal Translation of the pun. The advantage of Literal Translation in this case is denotative faithfulness. Concerning Free Translation and Quasi-Translation, they are difficult to employ, as the translator should be (or maybe) reluctant to create pairs of paronymy (or any other type of pun) that mock Arab celebrities (i.e., it could be illegal). Nonetheless, the puns in these English names are lost, as they are literally translated, and these names are not expected to be known by most of the Arabic audience. In other words, these puns are extremely local from a cultural perspective and are paired with paronyms from the sea life, and therefore, they are difficult to be rendered by Quasi-Translation or Free Translation. Again, it should be emphasized that replacing the original pairs of paronyms with ones from Arabic (i.e., Free Translation) can be constrained in the Arabic World, as translators are reluctant to refer to Arab celebrities and pair their names with names of referents from the sea life. The previous discussion implies that translators may block any cognitive efforts and give no time for a pun, as she/he knows right from the beginning that the final product (the translation or replacement of the pun) could be criticized or illegal in the target culture/region. However, this blockage does not mean that the pun is untranslatable or cannot be substituted.

4.1.9 Pun 9: Katie Current

The pun in the name Katie Current is an example of paronymy. The last name of Katie Couric, a famous American news reporter, is replaced with Current, the family name of the fish reporter. The sense of humor in this example of paronymy is that the family name Current, which is phonetically related to the family name Couric, is selected to show that the fish reporter consistently follows the events in a funny way. In the subtitled and dubbed versions, the employed strategy is Literal Translation (Table 12).

Subtitling and dubbing Katie Current by Literal Translation

| 00:02:36/00:02:14 | ||

|---|---|---|

| English token | Dubbing/subtitling | Back Translation |

| Katie: Good morning, Southside Reef. I’m Katie Current, keeping it current. | كيتي كيرنت | Katie Current |

In both subtitling and dubbing, translating the signs of the pun is ignored by the translators, and therefore it is Literal Translation, as the translation is solely faithful to the denotation of the token. Now, could another translation method be adopted to transfer the denotative meaning and the cultural reference (the signs of the pun) to the target audience? This can be achieved by Free Translation. It is by adding the name of a well-known Arab news reporter in the translation and pairing it with a phonetically related word that gives the meaning of current, or a meaning close to it, yet this needs much cognitive effort. Again, this Free Translation can be considered inappropriate (or be banned) in the Arabic World, so accepting the game of pun translation is not preferable in this context. This also implies that the pun is not necessarily untranslatable or cannot be substituted. Its translation or substitution is imaginable in the target language.

4.1.10 Pun 10: Superstar

Superstar is an example of homophony in the movie. Oscar, the fish, is showing off by calling himself a superstar. The signs of the pun (homonymy) are star 1, which means a famous person (a celebrity), and star 2, which refers to starfish, a sea creature.

In the subtitled version in Table 13, superstar is translated by Literal Translation. This translation is not faithful to the denotative meaning of the token, as سمكة نجم Samakat ndʒmh does not denote that Oscar is bragging. Likewise, this translation ruins the pun and misses the humorous load. The translation is neither funny nor figurative. In other words, the pragmatic connection between star 1 and star 2 is lost, and therefore, the Arab audience is not expected to guess that Oscar uses this pun to show off. This indicates that the translator ignores the pun and tries to preserve the denotation, although the translator did not deliver the right denotation.

Subtitling superstar by Literal Translation

| 00:04:27 | ||

|---|---|---|

| English token | Subtitling | Back Translation |

| Oscar: Cause even a superstar Mack daddy fish like me | سمكة نجمة | Starfish |

| Dubbing | Back Translation | |

| نجم | Superstar | |

The translator in the dubbed version also ignores translating the signs of puns, and therefore, it is an instance of Literal Translation that ignores the source pun and faithfully transfers the denotation.

4.1.11 Pun 11: Southside Sharks

Southside Sharks is a humorous and linguistic example that can be treated as a paronymic pun, as it is similar in a way to the second sign of the pun, which is Southern Sharks. The first sign differs, but the second one is identical in both phrases. This difference, I assume, results in generating a paronymic pair. For the sake of visualizing the scene, while the characters Oscar and Lenny were sneaking into a room, Lenny was imitating the Southern Sharks, which is an American baseball team. Further, another sound effect was added, the screaming of the fans. The translator in the subtitled version uses the Literal Translation strategy. She/he literally translates Southside Sharks. Additionally, the addition of فريق fariiq “team” can be adequate to refer to the second sign of the pun (the real baseball team). In this way, such translation will secure the signs of the pun, yet it is more likely not funny among Arab audiences. The translator ignores the signs of this pun (and the sense of humor in this pun). In this sense, the subtitling indicates that the pun is lost by Literal Translation (Table 14).

Subtitling Southside Sharks Literal Translation

| 00:43:15 | ||

|---|---|---|

| English token | Subtitling | Back Translation |

| Lenny: Now batting for the Southside Sharks | فريق الحيد الجنوبي | South reef team |

| Dubbing | Back Translation | |

| أسماك القرش | Sharks | |

Regarding the dubbing of this token, this phrase is also translated via Literal Translation, yet it reduces the linguistic weight of this phrase: Sharks literally translated and Southside is omitted.

This entails that subtitling and dubbing of the pun Southside Sharks are examples of Literal Translation of the pun, which means that the translators ignore paying effort to preserve the signs of the pun, replace one of its signs, or even replace its signs with ones from the target language, Arabic. This avoidance is understandable, as it involves a culturally very specific sign (Southern Sharks), which is not that known in the Arabic world. This implies the translation of a linguistic/figurative token (i.e., pun) becomes more complicated if it involves a cultural reference that is not known among target audiences.

4.2 Discussion

The researchers qualitatively analyzed the puns collected from the animated movie Shark Tale and the quality of their Arabic translations in its subtitled and dubbed versions. This research adopts Aleksandrova’s (2019) Taxonomy wherein a pun is treated as a cognitive game that can be accepted or rejected by the translator. According to Aleksandrova’s Taxonomy, there are three strategies for dealing with puns. These are: (1) Literal Translation, (2) Quasi-Translation, and (3) Free Translation. At first glance, the findings of the present study confirm that these strategies are employed while subtitling and dubbing the collected puns from the target animated movie, Shark Tale, into Arabic. The employment of these strategies is illustrated below:

(1) The game is rejected: The pun’s host is literally translated, and therefore the pun’s signs are expected to be lost, as no cognitive effort or time is spent dealing with the signs of the pun. Nonetheless, Literal Translation, by chance, could transfer the signs of the pun and a sense of humor when the source and target languages share similar puns.

Additionally, it has been found in the current study that a translator can ignore or reject the game of translating puns not only by Literal Translation but also by No Translation. The distinction between these two methods of rejecting the process of translating a pun is that Literal Translation is the Literal Translation of the linguistic host of a pun (i.e., a word or phrase), without considering the signs of the embedded pun, whereas No Translation is the deletion of the linguistic host of pun (the total loss of the word embedding pun). On this basis, this finding calls for integrating this flavor of rejecting the game of pun translation in Aleksandrova’s (2019) Taxonomy. A further minor issue raised in this study is the fact that visual puns and complex puns that are culturally local may be ignored using the No Translation strategy. It appears that translators leave it up to viewers to interpret them. On this basis, the game of translating simple puns is often subject to be accepted, while complex and culturally local puns are expected to be ignored. For example, Seal, Coral-Cola, GUP, Fish King, and Starfish Tours, which are examples of visual puns, were ignored by No Translation.

(2) The game is accepted: When it is accepted, cognition begins to work. It is the moment when the translator perceives the source pun and its signs and starts attempting to transfer it to the target text. At this stage, the translator may choose one of two strategies:

Quasi-Translation: The translator keeps one of the signs of the original pun and substitutes the other signs with a suitable one from the target language. Consider the pun Don Lame-o. The name “Don Lame-o” is a complex pun. Don Lame-o is a slang term for stupid. As a result, it is a paronym for the mob boss’s real name, Don Lino. For instance, to express humor in Arabic it was suggested to use the word lajmuun “lemons,” instead of lame-o in al-doon lajmuun. However, in this translation, Arab audiences are expected to perceive lajmuun as an example of paronymy (Don Lino vs al-doon lajmuun) to mock Don Lino, which might be interpreted as a sign of cowardice by Arab viewers. Similarly, in the Spanish translated version, Don Limpio, a commercial brand of a well-known cleaning product in Spain, replaces Don Lame-o. This substitution indicates that one of the English pun’s signs, Lino, is retained while the second, Lame-o, is replaced with Limpio. As a result, the translator creates a humorous Spanish paronym for the English Don Lino to mock the character.

Free Translation: The translator deletes the signs of the source pun and replaces them with a new pair of signs from the target language. To illustrate this strategy, the pun in Bring my clams, for example, which is the homonymous pair clams 1 “sea creatures” and clams 2 “dollars,” is replaced with the Arabic homonymous pair quruuʃ 1 “sharks” and quruuʃ 2 “piasters.” In this way, a figurative sense is secured, and a sense of humor is expected to be promoted among the Arab audience. Another example is Kelpy Kremes which is the paronym derived from Krispy Kreme, an American doughnut company and coffeehouse chain. For example, it is recommended that to convey humor in Arabic, a sea creature, such as tuunats, a blended derivative of tuuna “tuna” and donats “donates” can be used. This Arabic paronymy, which substitutes the original pun’s paronymy, as well as transliterating Krispy Kreme in Arabic, resulting in Krispy Kreme tuunats, expresses the direct meaning, compensates for the original pun, and keeps the target language, Arabic, amused.

To wrap up, puns are generally translatable especially when the translator decides to accept the game of pun translation and find a way to transfer one of its signs or replace its signs with a new pair from the target language. It is important to note that the signs of a pun can be accidentally transferred to the target language even if the translator decides to ignore the pun. However, when the pun is visual or culturally very local, it will be very difficult to be transferred or even substituted. Nonetheless, it should be emphasized that the level of creativity may differ from one translator to another. Hence, the focus while translating a pun should shift from the source and target text to the translator’s cognition. Specifically, the (un-)translatability is not an instant decision. It depends; what could be untranslatable to one person could be transferable (or be substituted) for another person. These results are consistent with Utami (2018) where puns are translatable according to the results of his research. The research revealed five different wordplay types used in the Shrek movie, including homonymy, paronymy, polysemy, idioms, and morphological development. Additionally, three translation strategies were used: literal translation, loan translation and deletion. Literal Translation was the most frequently. It appeared in twenty two cases. Loan translation is employed two times, and deletion one time.

Additionally, in Brotons (2017), the results produced are summed up in his examination of the translation techniques utilized in dubbing Shark Tale. The non-translation method, which was applied in 12 of the 21 examples examined, was the most prevalent translation strategy found. Three times each, the literal, explanatory, and successful translation procedures were also used. Following the application of these procedures, the evaluation of the primary type of equivalence showed that 24% of the translations achieved pragmatic equivalence, 14% achieved partial pragmatic equivalence (transferring only a portion of the funny effect), and 62% obtained denotative equivalent. When comparing his results with this research, it was found that puns and humor are translatable in general, but it needs more effort and cultural knowledge from the translator so he can render the connotation as well as the denotation meaning taking into consideration the sense of humor.

Concerning the difference between subtitling and dubbing in terms of efficiency in preserving puns or, at least, raising a sense of humor, the collected tokens from the subtitled and dubbed versions of the targeted movie indicate that ignoring puns and their signs is the prevailing tendency. It was expected that translators should take advantage of the mode of dubbing to raise a sense of humor and to use figurative language, as the figurative tools, such as homophony, are basically oral; however, such implementation has not been observed in the collected dubs.

It is worth mentioning before concluding this article that the findings of the current study have to be seen in light of some limitations pertaining to a number of pun tokens and the targeted AV content. Particularly, more pun tokens from a variety of movies are required to be compiled and investigated to check the validity of the current findings, and this is left for future research.

5 Conclusion

This study has examined the translatability of puns in the animated movie Shark Tale from Arabic. The dubbed and subtitled versions have been investigated. After the qualitative data analysis, which is based on Aleksandrova’s (2019) Taxonomy, it has been found that the translators avoided translating puns. They either literally translated (Literal Translation) or omitted them (No Translation). However, the translations suggested by the researchers indicate that puns can be translated by accepting the game of translation using two different strategies:

Quasi-Translation where the translator preserves one of the signs of the original pun and replaces the other with a suitable one from the target language.

Free Translation where the translator replaces the two signs of the source pun with new signs from the target language.

Further, it has been found in this study that the identity and complexity of puns are involved in their translatability. If a pun is visual and/or complex (i.e., culturally very local), it is subject to be ignored by No Translation (i.e., omitting the linguistic host of a pun). Concerning subtitling vs dubbing distinction, no difference in the quality of pun translation. The signs of a pun are often ignored. The main implication of this study is that it is hard to translate humorous and figurative language; yet, they are translatable. Therefore, the translator should have a positive attitude toward it, as translating this language, such as puns, can be obtained by more than one technique (i.e., Free and Quasi) that could preserve or raise a sense of humor.

-

Author contributions: Rozan Yassin conceptualized the study, conducted the research, and wrote part of the manuscript. Abdulazeez Jaradat assisted with the research, contributed to the manuscript writing, and proofread it. Ahmad S. Haider contributed to rewriting some sections of the manuscript, proofreading, and providing feedback on the final draft.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

Aleksandrova, E. (2019). Audiovisual translation of puns in animated films. The European Journal of Humour Research, 7(4), 86–105.10.7592/EJHR2019.7.4.aleksandrovaSearch in Google Scholar

Attardo, S. (2002). Translation and humour. The Translator, 8(2), 173–194.10.1080/13556509.2002.10799131Search in Google Scholar

Attardo, S., & Raskin, V. (1991). Script theory revis(it)ed: Joke similarity and joke representation model. Humor, 4(3–4), 293–347.10.1515/humr.1991.4.3-4.293Search in Google Scholar

Au, K. K. (2009). Introduction. In G. C. F. Fong & K. K. Au (Eds.), Dubbing and subtitling in a world context (pp. vii–xii). Chinese University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Auliah, S. N. (2017). An Analysis of Pun Translation in the Movie “Hotel Transylvania 2”. (Ph.D. dissertation). Universitas Islam Negeri Alauddin Makassar.Search in Google Scholar

Bréal, M. (1904). Essai de sémantique (science des significations). Hachette.Search in Google Scholar

Brotons, M. L. N. (2017). The translation of audiovisual humour. The case of the animated film Shark Tale (El Espantatiburones). MonTI. Monografías de Traducción e Interpretación, 9(2), 307–329.Search in Google Scholar

Chaume, F. (2020). Audiovisual translation: Dubbing. Routledge.10.4324/9781003161660Search in Google Scholar

Coelh, L. J. (2003). Subtitling and dubbing: Restrictions and priorities. Retrieved from Translation Directory.Search in Google Scholar

Cooper, C. (2008). Elucidating the bonds of workplace humor: A relational process model. Human Relations, 61(8), 1087–1115.10.1177/0018726708094861Search in Google Scholar

Delabastita, D. (1996). Traductio: Essays on punning and translation. St. Jerome Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Díaz Cintas, J. (2001). La traducción de la comedia en el cine: Un estudio de caso. In A. Sánchez (Ed.), La traducción en el siglo XXI (pp. 123–135). Universidad de Salamanca.Search in Google Scholar

Diaz-Cintas, J. D. (2009). New trends in audiovisual translation (pp. 133–141). Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781847691552Search in Google Scholar

Diaz-Cintas, J. D., & Remael, A. (2014). Audiovisual translation: Subtitling. Routledge.10.4324/9781315759678Search in Google Scholar

Díaz-Pérez, F. (2014) Relevance theory and translation translating puns in Spanish film titles into English. Journal of Pragmatics, 70, 108–129.10.1016/j.pragma.2014.06.007Search in Google Scholar

Dijkstra, T., Grainger, J., & Van Heuven, W. J. (1999). Recognition of cognates and interlingual homographs: The neglected role of phonology. Journal of Memory and Language, 41(4), 496–518.10.1006/jmla.1999.2654Search in Google Scholar

Gervais, W. M., & Wilson, D. S. (2005). The evolution and functions of laughter and humor: A synthetic approach. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 80(4), 395–430. PUBMED.NCBI.NLM.NIH.GOV.10.1086/498281Search in Google Scholar

Gottlieb, H. (2004). Language-political implications of subtitling. In Orero, P. (Ed.), Topics in audiovisual translation (pp. 83–100). John Benjamins Publishing Company.10.1075/btl.56.11gotSearch in Google Scholar

Hiranandani, N. A., & Yue, X. D. (2014). Humour styles, gelotophobia and self-esteem among Chinese and Indian university students. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 17, 319–324.10.1111/ajsp.12066Search in Google Scholar

King, J. (2000). Magical reels: A history of cinema in Latin America. Verso.Search in Google Scholar

Lyons, J. (1982). Language and linguistics. Cambridge University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Martin, R. A. (2007). The psychology of humor: An integrative approach. Elsevier Academic Press.Search in Google Scholar

Martínez Sierra, J. J. (2009). The relevance of humour in audio description. Intralinea, 11.Search in Google Scholar

Massidda, S. (2015). Audiovisual translation in the digital age: The Italian fansubbing phenomenon. Springer.10.1057/9781137470379Search in Google Scholar

McGraw, A. P., & Warren, C. (2010). Benign violations: Making immoral behavior funny. Psychological Science, 21(8), 1141–1149.10.1177/0956797610376073Search in Google Scholar

Mehawesh, M., Alnawasrah, N., & Saadeh, N. (2023). Challenges in translating puns in some selections of Arabic poetry into English. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 14(4), 995–1004.10.17507/jltr.1404.17Search in Google Scholar

Mendiluce, M., & Hernández, M. (2004). La traducción de la comedia en el cine: Un estudio de caso. In A. Sánchez (Ed.), La traducción en el siglo XXI (pp. 123–135). Universidad de Salamanca.Search in Google Scholar

Nunberg, G. (1979). The non-uniqueness of semantic solutions: Polysemy. Linguistics and Philosophy, 3(2), 143–184.10.1007/BF00126509Search in Google Scholar

Ritchie, G. (2004). The linguistic analysis of jokes. Routledge.10.4324/9780203406953Search in Google Scholar

Utami, I. B. (2018). Wordplay in shrek movie and its Bahasa Indonesia Subtitle (Doctoral dissertation). Universitas Muhammadiyah Sumatera Utara.Search in Google Scholar

Valera, S., & Ruz, M. (2021). Translating humor in audiovisual media: A case study of Friends and The Big Bang Theory. European Journal of Humour Research, 9(1), 76–92.Search in Google Scholar

Vandaele, J. (2001). The translation of humor: An integrated model. In A. Chesterman, N. Gallardo San Salvador, & Y. Gambier (Eds.), Translation in context (pp. 145–160). John Benjamins Publishing Company.Search in Google Scholar

Warren, C., & McGraw, A. P. (2015). What makes things humorous. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(23), 7105–7106.10.1073/pnas.1503836112Search in Google Scholar

Winarti, N. (2011). An Analysis of Pun Translation in The Animation Movie “Madagascar II Escape to Africa”. (MA thesis). Sebelas Maret University. www.ethesis.net/Wordplay/Wordplay.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Yue, X. D., Wong, A. Y. M., & Hiranandani, N. A. (2014). Humor styles and loneliness: A study among Hong Kong and Hangzhou undergraduates. Psychological Reports, 115, 65–74.10.2466/20.21.PR0.115c11z1Search in Google Scholar

Yus, F. (2016). Humour and relevance. Joh Benjamins.10.1075/thr.4Search in Google Scholar

Zabalbeascoa, P. (2005). Humor and translation – an interdiscipline. De Gruyter Mouton, 18(2), 185–207. doi: 10.1515/humr.2005.18.2.185.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Designing the Feminist City: Projects, Practices, Processes for Urban Public Spaces, edited by Cecilia De Marinis (BAU College of Arts and Design of Barcelona, Spain) and Dorotea Ottaviani (University of Sapienza, Italy)

- Feminist Urban Paideias: The Need for New Imaginaries of the Aesthetic Walk

- Special Issue: Violence(s), edited by Carolina Borda (NHS Scotland) and Cristina Basso

- “He Who Obeys Does Not Err”: Examining Residual Violence in the Practice of Obedience Within the Catholic Church Through a Case Study of the Capuchin Order

- “Violent Possible”: The Stochasticity of Institutional Violence

- Stepping Out of Line: Moving Through Vulnerability With Children in Transition

- Autoethnographic Enquiry of Sexual Violence in Academia

- Towards a Reparatory Theory of Creolization

- Special Issue: Challenging Nihilism: An Exploration of Culture and Hope, edited by Juan A. Tarancón (University of Zaragoza)

- Ecological Grief, Hope, and Creative Forms of Resilience: A Creative Practice Approach

- Longing for the Past and Resisting Oblivion: Palestinian Women as Guardians of Memory in Bye Bye Tiberias (2023)

- Research Articles

- A Socio-Historical Mapping of Translation Fields: A Case Study of English Self-Help Literature in Arabic Translation

- Interaction of Linguistic and Literary Aspects in the Context of the Cultural Diversity of the Turkic Peoples of Central Asia

- Challenges and Strategies of Translating Arabic Novels into English: Evidence from Al-Sanousi’s Fiʾrān Ummī Hissa

- Persuasion Strategies in Facebook Health Communication: A Comparative Study between Egypt and the United Kingdom

- Digital Games as Safe Places: The Case of Animal Crossing

- Traditional Metaphors of Indonesian Women’s Beauty

- Evaluation of Translatability of Pun in Audio-Visual Content: The Case of Shark Tale

- Bovarism’s Neurotic Reflections Across Cultures: A Comparative Literary Case Study in Light of Karen Horney’s Neurosis Theory

- Flower Representations in the Lyrics of A.A. Fet

- Kembar Mayang and Ronce as Motif Ideas in Natural Dye Batik of Keci Beling Leaves and Honey Mango Leaves

- The Transformation of Kazakhstan’s National Classics in World Performing Arts

- Congratulation Strategies of Crown Prince Hussein’s Wedding: A Socio-pragmatic Study of Facebook Comments

- New Model of Contemporary Kazakh Cinema – Artstream: Trends and Paradigms

- Implementation of the Alash Idea in Literary Translations (On the Example of Contemporary Kazakh Literature)

- Transformations of the Contemporary Art Practices in the Context of Metamodern Sensibility

- Tracing the Flâneur: The Intertextual Origins of an Emblematic Figure of Modernity

- The Role of Media in Building Social Tolerance in Kyrgyzstan’s Ethno-Cultural Diversity

- Persuading in Arabic and English: A Study of EFL Argumentative Writing in Contrast with Native English Norms

- Refusal Strategies in Emirati Arabic: A Gender-Based Study

- Urban Indonesian Women and Fandom Identity in K-drama Fans on Social Media

- Linguistic and Translational Errors on Bilingual Public Signs in the Saudi Southern Region: A Linguistic Landscape Study

- Analyzing the Pragmatic Functions of the Religious Expression /ʔallaːh yaʕtiːk ʔilʕaːfje/(May God grant you health) in Spoken Jordanian Arabic