Abstract

This study aims to develop accountability practices that harmonize with the local spiritual culture in the Jimbaran traditional village. The current accountability practices are viewed not just as formal procedures but also as informal practices involving moral and ethical relationships with God. An ethnomethodological study integrated with Catur Marga culture as a critical perspective revealed the problem of delays in submitting accountability reports due to the shift in the cultural meaning of “ngayah” and the shift in the implementation of religious ceremonies from spiritual practices to more formal activities. These problems can be addressed by synergizing Catur Marga principles with accountability practices. First, involve community representatives, religious leaders, and traditional elders in the village's financial management, as in regular meetings to align the vision and mission to strengthen the “ngayah” motivation in governance and financial accountability. Second, the traditional village governments must consistently provide Dharmawacana and management accounting training to balance scientific knowledge with traditional spiritual–cultural knowledge. Last is the development of the Catur Marga-based Pararem, which regulates the technical aspects of financial management accountability and should be synchronized with the spirit of devotion to God to preserve the local spiritual culture in the Jimbaran traditional village.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, global trends in public administration have increasingly influenced financial sector reforms worldwide. These reforms have led to the adoption of New Public Management (NPM) principles in Indonesia. NPM is interpreted as a form of public policy oriented toward free market mechanisms and privatization of state and regional public companies, including local government autonomy policies based on private management models (Lutfillah, 2016). This regional government autonomy began with Law Number 22 of 1999 concerning Regional Government, known as the Regional Autonomy Law, which was later updated with Law Number 23 of 2014 (Dharma, 2023). Regional autonomy requires regional governments to provide welfare to their regions by providing public services needed by the community. Providing good public services significantly influences the success of good governance, where accountability is the key to implementing regional financial management. Accountability can be assessed as openness, transparency, accessibility, and reconnection with the public (Dubnick, 1998). To achieve the objectives of Good Governance, regional governments must be able to present accountability that explains all the activities carried out, especially in the financial sector, which aims to control the performance of regional governments so that they run according to the principles of Good Governance. Accountability provides accurate and reliable financial data and information, which helps regional governments achieve transparency, responsibility, efficiency, effectiveness, and a strategic vision in financial management (Ashari & Riharjo, 2019).

Accountability practices in Indonesia have attracted significant academic interest, especially those that incorporate elements of local genius and spirituality because Indonesia has many regions with local religious beliefs that are closely tied to spirituality in carrying out governance, such as regulating the use of natural resources, and managing village funds based on accountability, transparency, and community participation (Rahmatiani, 2016; Sumolang, 2022). Bali is one of the regional governments thick with local spiritual culture. Bali has a traditional village as the lowest government structure, focusing on traditional and religious functions. It is an area where the community carries out social and spiritual activities together, following the cultural system (Pitana, 1994). Traditional villages are also subject to regional autonomy regulations in Law Number 6 of 2014, followed by Regional Regulation (PERDA) number 4 of 2019 and Governor’s Regulation (PERGUB) number 55 of 2022. Apart from that, traditional villages are also bound by the culture in Bali to carry out governance, namely, the Tri Hita Karana culture of balance. The Tri Hita Karana concept emphasizes that all activities, including traditional village financial management, are based on aspects of the relationship between humans and God (parahyangan), humans and humans (pawongan), and humans and nature (palemahan) (Dharmawan & Yudantara, 2020; Santosa & Darmawan, 2021; Sari et al., 2021; Suidarma et al., 2021; Suminto & Kustiyanti, 2023). The Tri Hita Karana concept is also related to the process of planning activity programs and budgeting in traditional villages, as in Regional Regulation (PERDA) number 4 of 2019 and Governor’s Regulation (PERGUB) number 55 of 2022, which requires financial management of traditional villages to start from planning, budgeting, implementation, and accountability. This regulation also results from the implementation of an autonomy system originating from the NPM system. Therefore, financial management accountability in Balinese traditional village governments is also very important.

The Bali provincial government annually provides Village Revenue and Expenditure Budget (APBD) grant assistance to traditional village governments and must be able to provide accountability reports to the provincial government as a form of accountability for the use of grant funds. Apart from that, traditional villages also manage the original assets belonging to traditional villages (padruwen), which they manage themselves (because of the regional autonomy system), such as temples, land, and beaches, as well as non-binding donations. The traditional village government, as the manager, is also required to provide accountability for managing village assets to the community. This is why accountability is the central pillar of traditional village governance. Accountability also includes accounting practices and complete knowledge about environmental values according to where accounting is practiced. Therefore, accountability practices must be in synergy with the local cultural values of traditional villages (Kamayanti & Ahmar, 2019; Kamayanti, 2015, 2016, 2017; Ludigdo & Kamayanti, 2012; Mulawarman & Ludigdo, 2010; Triyuwono, 2011). Traditional villages generally have traditional cultural values and spiritual elements that serve as the basis for the lives of their people. These spiritual values must be integrated into accountability practices, which must be interpreted as not just recording finances and preparing financial reports but also efforts to balance worldly and spiritual life. Integrating spiritual values into traditional village accountability practices will build strong and sustainable governance, bring progress, and preserve cultural heritage and traditions for future sustainability.

However, the reality of accountability in traditional village financial management often has various problems. The decentralization of the regional government system has triggered paradigm differences between communities in traditional villages. The existence of PERDA Number 4 of 2019, which gives the village government the broadest authority to regulate and manage its finances, will cause traditional villages to become more autonomous. The more autonomous traditional villages are, of course, they are more vulnerable to financial management problems, such as the lack of knowledge capacity of traditional village government members in managing finances according to applicable regulations and fraud in financial management, which is the impact of the loss of morality of traditional village governments (Savitri et al., 2019). The lower the morality of traditional village government officials, the higher their tendency to commit fraud (Saputra et al., 2022). The phenomenon of corruption carried out by the Traditional Village government, which appears in regional print media, such as Penarukan Traditional Village, Candikuning Traditional Village, Songan Traditional Village, Tista Traditional Village, and Berawa Traditional Village, is also evidence that the government is increasingly low on morality and integrity (Bali Post, 2017, 2023; CNN Indonesia, 2024; Dewatapos, 2021; Nusa Bali, 2018; Saputra et al., 2022). Corruption is the abuse of authority using traditional village assets and provincial government aid funds for personal interests by falsifying financial reports as a form of accountability to the community. Wiguna et al. (2022) also prove that the Jimbaran traditional village government misappropriated village cash by making fictitious accountability reports. This phenomenon shows that the loss of morality, ethics, and even spirituality in the practice of accountability can give rise to unethical behavior and impact how humans practice accountability.

The meaning of accountability in materialism has been heavily infused with the value of rationality, which causes leaders to betray their people to seek worldly gain (Riyanti, 2020). The characteristics of materialism are based on the motive for personal gain and efforts to achieve more significant financial gains. Individuals and public organizations are encouraged to maximize profits by ignoring social, local, cultural, and spiritual values. Even though traditional villages were founded based on social values, local cultural values, and spiritual values that are balanced between humans and nature, humans and nature, and humans and God, changing times have also caused a shift in the mindset of traditional village government officials. This will shift the moral meaning of culture that government officials should use in managing their villages and will gradually eliminate this culture. This raises concerns about Bali’s future, closely related to the Tri Hita Karana concept, which is increasingly uncontrolled due to excessive intervention by worldly interests compared to heavenly interests (Wingarta et al., 2012).

Therefore, another perspective is needed to examine the problem of financial management accountability practices in traditional villages, especially those affected by the negative impacts of globalization and modernism, namely, the characteristics of capitalism, secularism, and rationalism, through the lens of local culture wrapped in religious teachings. This is because human morality can be created through local culture, religious teachings, or ideology (Ghazali et al., 2014; Kosec & Wantchekon, 2020; Liu & Wong, 2018; Meng & Zhang, 2011; Saputra et al., 2022; Wilfahrt, 2018). This phenomenon indicates the need to increase the spiritual culture to implement accountability practices in traditional villages. To address these problems, it is possible to establish accountability practices emphasizing spiritual aspects to reinforce the morality and integrity of traditional village governments. Therefore, this research aims to provide an accountability model based on a spiritual culture perspective that can restore local cultural elements of traditional villages wrapped in spirituality to remind traditional village government officials of the true purpose of life, not only prioritizing ego to obtain material benefits but also aiming to achieve spiritual happiness through actions that are by the traditional culture, which is closely wrapped in religious teachings. This reminder will regenerate village government officials’ morality, ethical behavior, and honesty in implementing traditional village financial management accountability practices.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Critique of Agency Theory in Accountability Practice

Agency theory, as proposed by Eisenhardt (1989) and Jensen and dan Meckling (1976), defines accountability as the obligation of one party to provide information and justification to another. The two parties in an accountability framework are usually described as principals and agents. The principal is the party that must be held accountable, and the agent carries the responsibility (Gray et al., 1987). This definition implies that accountability is an agency contract relationship with a form of delegation of authority in decision-making given by the owner to the company or organization (Rahayu, 2018). On the other hand, according to Scott (1997), the agency theory is a contract design that balances the interests of the principal and agent when a conflict occurs. As an agent, management should work based on the company’s or shareholders’ interests. However, the reality that often happens today is that management is concerned with itself by maximizing its utility through deviant actions that do not benefit the company in the long term or are detrimental to its interests (Rahayu, 2018). This condition gives rise to an imbalance of information and causes problems caused by the principal’s difficulty in controlling the actions carried out by the agent (Jensen & dan Meckling, 1976). Problems that can occur from this condition are (Eisenhardt, 1989) moral hazard, where the agent does not carry out things that have been mutually agreed upon in the employment contract, and adverse selection, a situation in which the principal does not know whether the decision taken by the agent is based on the information obtained or dereliction of duty.

This problem also occurs in the reality of public sector accountability practices in Indonesia. Based on data from Indonesia Corruption Watch, from 2015 to 2020, there were 676 defendants in village officials’ corruption cases, which continued to increase until 2021 and 2022, occupying the top ranking of corruption cases (Indonesia Corruption Watch, 2022, 2023, 2024; Purwanti et al., 2024; Wiguna et al., 2022). Moreover, corruption cases arise in traditional villages with the lowest regional government structure. This is because local governments’ lack of understanding of modern financial management mechanisms can cause the implementation of accountability to become less professional and increase the risk of fraudulent behavior in local governments (Atmadja & Saputra, 2018; Chang et al., 2019; Saputra et al., 2022). On the other hand, the modernization of financial management mechanisms and the development of accountability practices will certainly influence cultural values and local genius in regional government, especially when this practice is dominated by the values of materialism, egoism, and utilitarianism, which conflict with the local values that exist in regional government (Thalib, 2022). Materialism also has become integral to economic rationality (Lehman, 2005). The main characteristic of the philosophy of materialism is the emphasis on the material dimension, and a similar characteristic is also present in economic rationality. Economic rationality possesses competition, egoism, and excessive rationalism (Kusdewanti & Hatimah, 2016). The implications of these values ultimately influence real-world practices, including the concept of conventional accountability (Riyanti, 2020). This materialism also leads humans to obey, comply, and submit to a combination of egoistic and materialistic values that merge into the adhesive of utilitarianism (Triyuwono, 2012). The egoistic traits brought by modernism will form individualistic values in the organization, thus providing a logical consequence on the economic reality that is always seen as revolving around material reality, not touching the realm of spirituality, nature, the environment, and God. Eventually, slowly but surely, humans will come to believe that the form and meaning of accountability are only the accountability that focuses on the interests of those in power and is materialistic (Djamhuri, 2011). This is the result of the concept of accountability that has developed so far focuses on accountability and is only limited to giving responsibility for human actions to other humans (Bovens, 2007; Ebrahim, 2003; Jurana et al., 2022). This phenomenon has given rise to criticism that accountability mechanisms should not only be limited to preparing financial reports using accounting media but should also emphasize preparing ethical and moral action mechanisms (Joannides, 2012; Overduin & Moore, 2017; Sullivan & dan Dwyer, 2009). The separation between physical and ethical relations, ultimately bringing misery to society, is an advantage for power holders. This is one of the weaknesses of the form of accountability derived from two relationships, which considers an organization only as a set of contractual relationships. The concept of accountability should not only be a formal linear responsibility process, such as in the principal-agent relationship, which is only dominated by quantitative matters, but can also be understood as an individual’s life experience and can go beyond the technicalities of financial accountability (Kusdewanti & dan Hatimah, 2016; Miller, 2002; Roberts, 1996). Accountability should not only be limited to physical relationships but also moral and spiritual relationships (Purwanti et al., 2024; Triyuwono & Roekhuddin, 2000). This means the current accountability mechanism cannot resolve problems in the local genius culture that arise in accountability practices if it only makes material things the center of interest.

The order in the social system of Indonesian society, especially in the regional government, cannot be separated from the existence of the local genius wrapped in spiritual elements – for example, the traditional village government of Bali. The traditional village government system is formed based on religious and cultural concepts, namely, Hinduism, which is evidenced by the establishment of traditional villages that must have the holy temple of Kahyangan Tiga and become a village that is managed religiously, in the sense that the application and practice of the traditional and culture of the community are wrapped in elements of spirituality that animate and influence its implementation (Arimbawa & Santhyasa, 2010). Traditional villages’ financial transparency and accountability are also closely associated with spiritual elements, which should make the traditional village government aware and believe in a power beyond themselves that always oversees the financial management they carry out, namely, the power of God (Kurniawan, 2016). Therefore, it can be conceptualized that the traditional village government must carry out financial reports and spiritual-based accountability as an ethical and moral responsibility to God. This is because the traditional village government is run with the philosophy of Tri Hita Karana, where the form of accountability is accountability to God, accountability to humans, and accountability to the universe.

However, the phenomenon of corruption cases in traditional villages (as described in Section 1) provides an awareness that the traditional village government only emphasizes accountability as a medium to fellow humans and eliminates the aspect of accountability to God. The loss of accountability to God can lead to a loss of moral awareness and a tendency to engage in actions that benefit oneself without considering the impact on the community (Almutawallid & Santalia, 2024). This also gives rise to the assumption that Western government mechanisms cannot be fully implemented in regional government. Supposedly, the concept of accountability in the regional government system must synergize with local social and cultural elements (Djamhuri, 2011). This leads to the following question: If an entity is considered accountable for the goals of the entity itself (which is material in nature), what about human, social, and even metaphysical accountability?

Accountability mechanisms, especially in Indonesian regional governments, must be based on cultural values that not only prioritize human interests but also internalize individual dimensions with spiritual dimensions and the surrounding environment. An area’s local culture can trigger the emergence of moral legitimacy, manifested in actual moral actions. The existence of local values can encourage regional governments to realize ethical and moral social changes (Lehman & dan Kuruppu, 2017; Toms & Shepherd, 2017). The critical view of the erosion of local culture and even spiritual dimensions has caused academics to begin to explore the concept of accountability based on local culture and spirituality in Indonesia: Zulfikar (2016) who revealed the accountability behind the veil of Awa cultural wisdom values, namely, Obah-Mamah-Sana; Randa and Daromes (2014) researched the transformation of local Kombongan’s cultural values in building accountability of public sector organizations in the Tana Toraja regional government; Salle (2015) regarding the concept of accountability based on the values of Pasang Ammatora; Tanasal et al. (2019) regarding Metta and Kamma-based accountability; Hanisa (2023) researched fraud prevention with accountability in managing Tarra Tallu Village funds based on the local culture of Siri’ Na Pacce; and Maulana and Bakri (2023) explored the meaning of Bugis organizational accountability based on the interpretation of Bugis Sufism, namely, “Dua Temmassarang Retaillue Temmallaiseng.”

2.2 The Catur Marga Culture Perspective

The era of globalization is accused of causing Indonesian people to “lose” territorial boundaries and integrate themselves into the wave of mass culture produced by international materialism. The development of a culture of materialism is evident when the cultural values of the original Indonesian nation begin to erode, which can be seen from the decline of the national spirit and the fading of the culture of tolerance built on spirituality. This loss causes division because of the loss of a sense of humanity, the emergence of competition in the economic sector, and the emergence of egoistic traits built upon rationality that override local culture and spiritual teachings. Spiritual culture can be built by holding tightly to the local culture in Indonesia, wrapped by elements of spirituality (Nova, 2022). Indonesia still has regions with a local culture closely tied to spiritual values, including Bali.

Nevertheless, the Balinese people, the majority of whom have a faith culture, still consistently carry out their local culture, proven by frequent religious ceremonies and enforced traditional rules. The faith upheld by Balinese culture is a universal teaching that is easy to understand and implement in everyday life is Catur Marga, which contains a divine philosophy (tattva) directly related to universal educational patterns (Jayendra, 2017; Segara, 2018). The word Catur means four, and Marga represents the path or method for humans to get closer to God and lead them to achieve moksartham jagathitaya ca iti dharmah, perfection in physical life, and spiritual life (Sirtha, 2016). The four paths or methods are Bhakti, Karma, Jnana, and Raja (Sukartha et al., 2003). Bhakti Marga is sincere in upholding and maintaining goodness for humanity through noble behavior as a form of devotion to God (Jayendra, 2017). Karma Marga is a sincere work and a noble deed. Jnana Marga is the study of knowledge and devoting oneself to para vidya (spiritual knowledge) and apara vidya (worldly knowledge). Raja Marga has self-control over egoism, thoughts, and actions.

In modern life, Catur Marga has the ideological potential to help people build a work ethic and compete through a holistic understanding of its values. This is why the Catur marga is also needed to manage traditional villages. Traditional village governments must adhere to Catur marga as one of the four paths to success in managing traditional villages according to Hindu religious philosophy (Berita Bali, 2018). Traditional village governments should uphold ethics and morality in carrying out accountability practices in managing traditional village finances and remain always attached to traditional and cultural concepts to lead themselves to successful management in traditional villages. The application of the Catur Marga cultural concept in traditional village accountability practices is: Bhakti, where traditional village officials show sincere dedication and devotion in carrying out their duties and responsibilities for the welfare of the traditional village and interpret this as a form of devotion to God (Budiadnya, 2019; Dharmawan, 2020). Apart from that, the decision-making process, in both the planning and budgeting process and responsibilities, involves the active participation of Indigenous communities, reflecting dedication and concern for the community’s aspirations. Karma financial management is based on sincere motivation without worldly personal interests. Village funds are managed well and can be accounted for by following customary rules and carrying out duties and responsibilities consistently, on time, and responsibly (Parta & Kusuma, 2018). Jnana, traditional village officials have in-depth knowledge and understanding of traditional spiritual culture and accountability in the planning, budgeting, implementation, and financial accountability processes carried out carefully and in detail. Raja, the traditional village government, shows exemplary actions and decision-making strategies that involve deliberation and considering the community’s aspirations, as well as belief in the existence of God as a power to control all their actions at work.

Thus, including Catur Marga in the concept of accountability practices can reduce individuals’ “worldly” nature, so that they return to synergy with the characteristics of spiritual culture (Ningsih & Yudi Prastiwi, 2019; Triguna & Mayuni, 2022; Widana, 2019). The concept of Catur Marga, when linked to accountability in traditional village financial management, emphasizes the spiritual meaning of financial management and the preparation of financial reports. The elements of Catur Marga form the financial management accountability practice, which focuses more on the meaning of human self-control and is layered with spiritual power as the final form, namely, spiritual accountability.

3 Methodology

3.1 Type of Study and Data Sampling

This qualitative research uses an ethnomethodological approach to explore daily accountability practices in traditional village financial management (Garfinkel, 1967). However, because this research also aims to create change by presenting spiritual elements in traditional villages (Freund & dan Abrams, 1976), a critical paradigm is applied to overcome and transform fundamental problems that integrate spiritual elements into accountability practices. The critical paradigm in this research uses a spiritual values perspective from Catur Marga, which will be later used to form a practice model for accountability in traditional village financial management by examining the daily lives of traditional village government officials. This dual approach allows for a comprehensive understanding and establishes accountability in the context of the spiritual culture of Balinese traditional villages.

The research site is the Jimbaran Traditional Village. Jimbaran traditional village is one of the largest and richest traditional villages in Badung Bali, with an area of 20.50 km2 and many tourist attractions, such as Jimbaran Beach, Muaya Beach, and Tegal Wangi Beach. However, the traditional village of Jimbaran was previously embroiled in a corruption case involving the village government’s traditional village misuse of funds for personal interests during the 2010–2015 period (Wiguna et al., 2022). Currently, the Jimbaran traditional village is still in the process of improving its financial management practices. Therefore, this research aims to examine the ongoing improvements and to help provide an ideal model of accountability practices. Apart from that, the results of improvements in the Jimbaran traditional village can later be used as a consideration for making decisions on enhancements that will be carried out in traditional villages with similar cases, for example, fraud and misappropriation of funds.

Research informants were selected based on purposive sampling. They were people who had experienced injustice in previous fraud cases and were currently trying to improve financial management accountability practices in the Jimbaran traditional village. The informants chosen were the traditional village government for the current period (2020–2025). The research informants are listed in Table 1. Informants asked researchers to abbreviate their names.

Research informants

| Name | Position in traditional village government |

|---|---|

| RD | Head of traditional village |

| WM | Secretary of the traditional village |

| AW | Deputy secretary of the traditional village |

| NA | Treasurer of traditional village |

| WS | Implementing officials (Baga) |

3.2 Informant Consent

Jimbaran traditional village, including all informants, has given researchers verbal permission to participate in all activities, including observation, interviews, and documentation. Interview, observation, and documentation data obtained at the research location can be used as appropriate.

3.3 Data Analysis

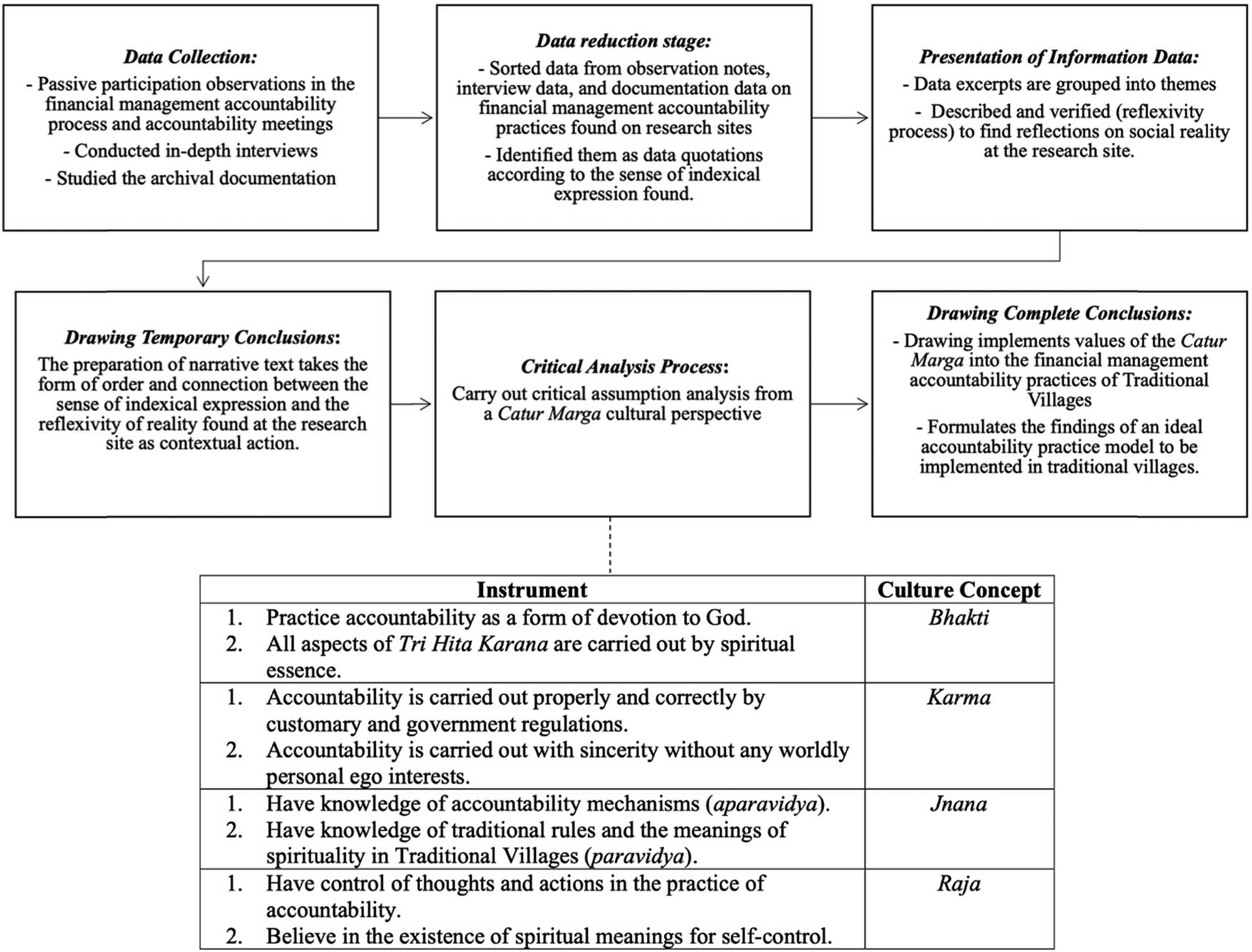

The data analysis in this study modifies the data analysis stage of the interactive model in qualitative research by Miles and Huberman (1992). The interactive model has four stages of data analysis, carried out continuously and repeatedly and can be carried out simultaneously with data collection (Damayanti, 2017). Researchers added two analysis stages to this interactive model. The six stages of data analysis are shown in Figure 1.

Data analysis stages (prepared by the author, 2024).

Based on Figure 1, the critical analysis process uses instruments derived from the meanings contained in the Catur Marga culture. In addition, to ensure the validity and credibility of the data, this research uses indexicality, contextualizing responses within the cultural environment, and reflexivity, which involves continuous reflection on the research process. Triangulation is used to cross-verify data from interviews, observations, and documents to ensure comprehensive and reliable results.

4 Research Findings

In this section, the research will first present field findings regarding the accountability practices implemented by the government of the Jimbaran traditional village through observations, documentation, and in-depth interviews. These practices will then be critically examined through the lens of the Catur Marga framework.

4.1 Jimbaran Traditional Village Accountability Practices

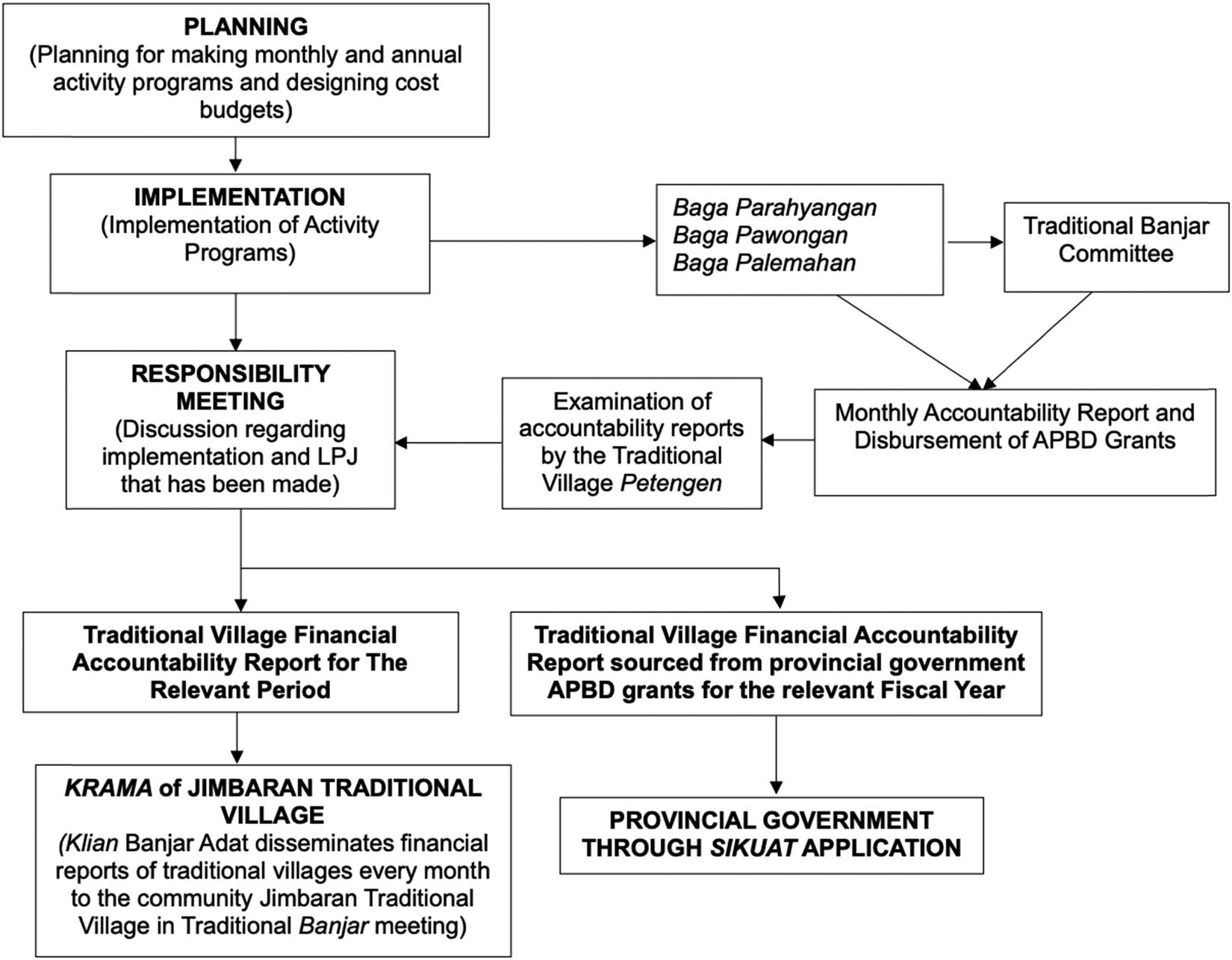

Based on the researchers’ observations, the village’s financial management was divided into two types. The first is funds from government grants, the entire management and distribution flow of which must follow the PERGUB number 55 of 2022 and are controlled by DPMA (the Service for the Advancement of Indigenous Peoples) and MDA (Traditional Village Assembly). Second, traditional village cash funds are generated from managing traditional village heritage assets. The village’s financial governance follows the flow of the rules related to accountability practices. It consists of accountability during activity planning, budgeting, and implementing activities. Accountability must always be achieved because every activity carried out by the village must be informed of the krama (community). Figure 2 shows the flow of the financial management accountability practices of the traditional Jimbaran village.

Flow of the financial management accountability practices of the Jimbaran traditional village. (Source: prepared by Authors, 2024).

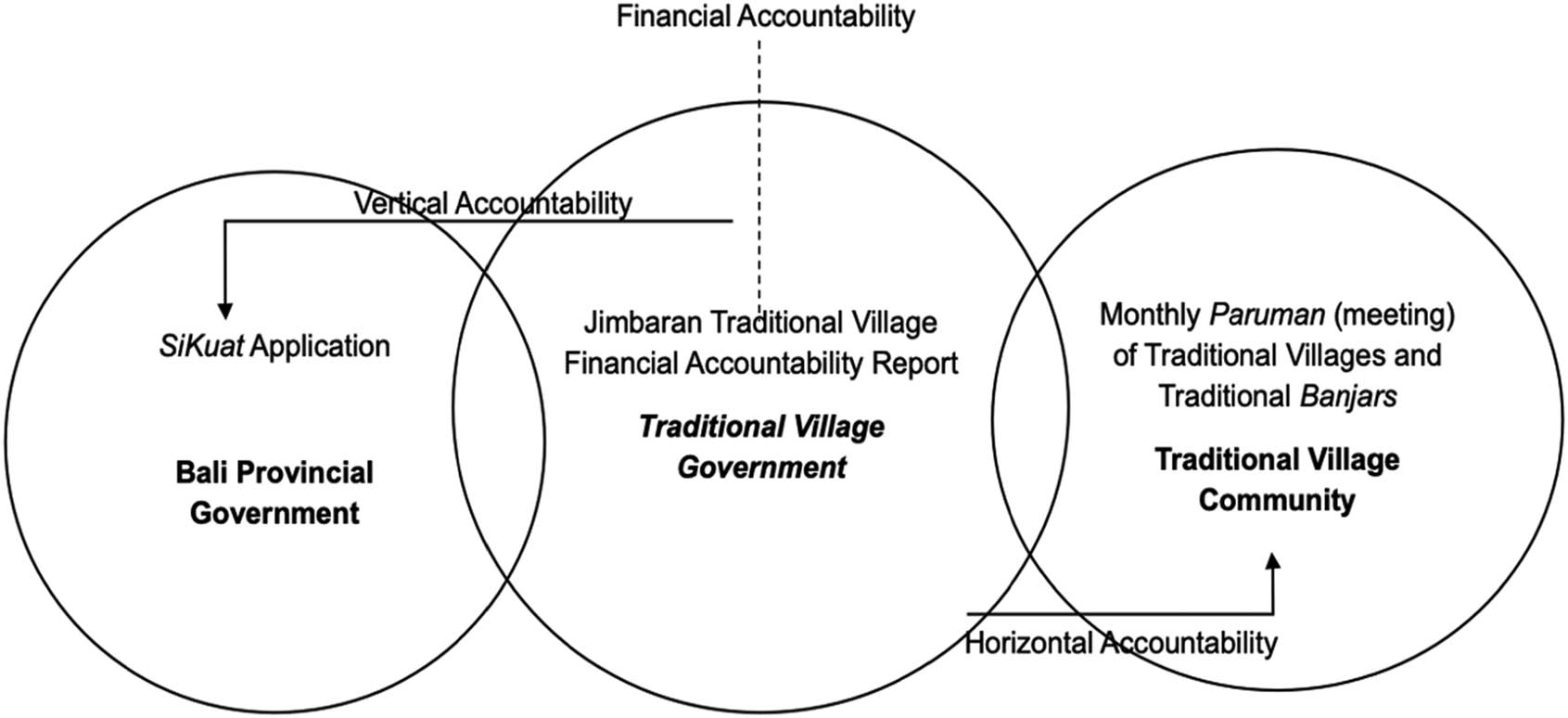

Based on Figure 2, responsibility in the traditional villages was carried out by making financial accountability reports (LPJ) using the village’s treasury, which were presented at monthly meetings. Following the amendment and agreement, accountability reports (LPJ) were signed, stamped, and socialized to the public through monthly Banjar meetings. Meanwhile, the use of grant funds has been regulated in PERGUB number 55 of 2022, which is reported in the SiKuat Traditional Village Financial System (SiKuat) application. This study formulates a mechanism for accountability financial management in the Jimbaran traditional village as shows in Figure 3.

The mechanism for accountability in the Jimbaran traditional village’s financial management. (Source: prepared by Authors, 2024).

Figure 3 shows that accountability practices in the financial management of the Jimbaran traditional village are still limited to financial accountability practices, marked by the availability of financial reports, vertical accountability to the government, and horizontal accountability to the community. In other words, the Jimbaran traditional village carries out conventional accountability (agency theory), namely, that the traditional village government, as an agent, is accountable for its financial management to the principals, which are the community and the government. Figure 3 also shows that traditional village governments only use apparatus knowledge to manage village finances during planning, budgeting, and making LPJ. Accountability practices based on Jnana Marga aparawidya knowledge direct traditional village government officials to seek scientific knowledge (accounting and management) to implement accountability. They will continue to learn and improve their understanding of effective financial management and accountability. However, aparavidya knowledge must be integrated with paravidya (spiritual) knowledge. A person’s success is not only determined by brain ability and thinking power but also by emotional and spiritual intelligence (Sihombing, 2019). Education based on morality and spirituality will develop other potentials so that future generations will always believe in the existence of God, be closer to God, and be more aware of their responsibilities as bearers of mandates and missions (Wahyuni, 2022). Spiritual knowledge is important because physical and material knowledge cannot add value to life (Agung et al., 2018). Thus, paravidya should also be applied to help traditional village government officials develop holistically, gain a deeper understanding of the purpose of life, strengthen moral values, and build integrity.

4.2 The Dilemma of Implementing Parahyangan Aspects and Delays in Submission of Accountability Reports (LPJ)

Accountability practices in Balinese Adat Villages should closely relate to traditional and spiritual culture. However, observations show that the parahyangan element is often carried out merely as a formality, creating a dilemma for traditional village governments. In addition, during traditional village government accountability meetings, debates arise due to implementing officials’ delays in the LPJ submission. This delay is caused by a lack of support from the officials responsible, who view the traditional village as operating on the concept of ngayah (selfless work without worldly motivation), where they are not paid as professional workers. Table 2 summarizes the key points from the interview transcript.

Summary manuscript of informant

| Topic | Informant | Interview |

|---|---|---|

| The dilemma of implementing Parahyangan aspects in traditional villages | RD | “Currently, there is a dilemma in Traditional Villages. The role of Traditional Villages is very strategic in developing the community, especially in traditional and spiritual ways. However, in the current conditions in Bali, we believe this era is Kali Yuga’s era (end of time), where the meaning of implementing Parahyangan is now more of a mere formality. For example, the routine activities we carry out, especially in the parahyangan program activities, namely religious ceremonies, and rituals, are often carried out purely ceremonially, so the spiritual side is usually not studied.” |

| AW | “In carrying out the parahyangan aspect, we run it as a mere formality. So, when we must perform temple ceremonies in the village, we just go ahead and do it. What will be a problem is that if we don’t implement it then we will be blamed by society.” | |

| NA | “How we carry out the parahyangan aspect is up to our beliefs. Which it is important that everything goes according to plan and does not forget to comply with the RAB (draft budget). Sometimes this also becomes a dilemma, the niskala meaning aspect is now covered by the sakala meaning, the important thing is that the implementation has been seen to be going well, so it is considered complete.” | |

| Delays in in submission of Financial Accountability Report (LPJ) | NA | “Implementing officials are often late in submission of LPJ. As with previous religious ceremonies, the implementing officials has not yet submitted an accountability report. If we record it like accounting in general, it will not be balanced.” |

| AW | “The reason for the delay in submission of LPJ is because there are many activities carried out in the Traditional Village, and the support from our officials is also very minimal. Moreover, we work based on ngayah, so our LPJ can sometimes be late. This usually delays the accountability process.” | |

| WS | “The reason for the delay in submission of LPJ is that we are still operating under the traditional term of ngayah. Our finances are not sufficient, meaning we are not paid like professionals.” | |

| WM | “If we are demanded to be perfect or something close to perfection, we should be given a salary commensurate with what we do. But in this traditional village, we perform ngayah. This is what creates a dilemma in carrying out the governance of traditional village.” | |

| RD | “The meaning of ngayah has shifted towards materiality. All work in traditional villages must be paid. It must be understood that in this Kali Yuga era, it must also be agreed that what is most meaningful is material.” | |

| AW | “Of course, this delay had impacts such as fraud during the previous government, which was initially due to frequent delays in submission of LPJ for activities. Lots of activities are the reason LPJ is not finished, and this has resulted in the fraud not being detected. This means that delay LPJ will be reported in the following period, which is easily distorted because financial reports are not presented clearly and transparently in one period.” | |

| NA | “In cases of fraud in the previous government, it was caused by abuse of authority. There is an accountability report provided that is fictitious. In the reported accountability, the traditional village treasury in 3 years totalled Rp. 29,145,000. Meanwhile, the actual cash is Rp. 13,768,000. The difference is indicated to be distorted for personal gain.” | |

| WM | “This fraud could have been caused by the absence of written rules regarding financial management in awig-awig (customary law) and pararem (customary regulations), weak supervision and opportunities, and weak morals of the management in the previous government.” |

Based on Table 2, the first topic is that the program of religious ceremony activities in the Parahyangan culture is carried out merely to fulfill the implementation of these activities according to the existing rules, without any appreciation of the meaning and values contained in the ceremony. Parahyangan is a medium through religious ceremonies in traditional villages that humans use to create a harmonious relationship between humans and God, ultimately creating peace and prosperity for humans themselves (Surpha, 2004). Religious ceremonies should contain vital elements of faith and belief as a form of human spiritual devotion to God. However, this is only done in formality because traditional villages prioritize Sakala (appearance/physical) over Niskala (transcendent/metaphysical). Parahyangan, which is only considered a formality, will erode the spiritual values contained in its aspects (Karmini, 2022; Sukma et al., 2020). The shift in the meaning of Parahyangan can be seen as part of the commodification of religious spirituality, which has given rise to different meanings of religious (spiritual) fervor. What was once the domain of the divine has now shifted to the realm of reason or cognition and even toward the realm of human desire or will (Atmadja & Atmadja, 2008; Juniartha, 2020). This also raises a critical view because parahyangan should be done with Bhakti (devotion). When parahyangan is only done formally without heart and belief, it will erode the true meaning of Bhakti because formality in parahyangan activities can separate individuals from deep spiritual experiences and a deep relationship with God (Karmini, 2022; Sukma et al., 2020).

In other words, the implementation of the parahyangan aspect, which was initially seen as a sacred activity, has now shifted to become a manifestation of the desire or desire of the traditional village government to demonstrate changes in the governance of traditional villages so that spiritual practices are assessed based on economic and financial measures. The reason is that the Jimbaran traditional village government currently prioritizes physical (visible) appearance elements because tangible actions are prioritized to show the changes made. For example, the implementation of the ceremony went according to what was planned, budgeted, and accountable. This is also a form of implementing modern financial management in traditional villages, which only focuses on accountability, namely, emphasizing strict financial recording, reporting, and accountability, but on the other hand, ignores the meaning and spiritual values of religious activities, which are the foundation of the life of the Indigenous community. Modern financial management that is too pragmatic can cause the erosion of cultural and traditional elements in implementing ceremonies. If left unchecked, it will gradually have implications for the erosion of culture and religious traditions and can threaten the preservation of cultural heritage and community spirituality.

Besides that, it is important to remember the case of the previous government, where fraud in the management of traditional village cash occurred by presenting fictitious financial accountability. This gives rise to the assumption that fraud can still be committed even though the accountability report has been prepared according to a modern financial management system. Similar to the phenomenon of conventional (non-traditional) government in Indonesia today, corruption is still rampant even though a standard system has been implemented. So, where is the problem? This does not lie in the system but in the individuals who run it (Osborne & Gaebler, 1992). A shift in spirituality causes individuals to lose morality. Therefore, spiritual strength is the most important factor in shaping an individual’s mentality and behavior according to spiritual teachings.

The second topic is implementing officials’ delay in the delay in submission of LPJ. This has led to criticism that the current meaning of ngayah is working as they please or according to the capabilities of the traditional village government because they are not paid as professional workers. This has resulted in a lack of motivation to work on time. Delays in the submission of LPJ will have a negative impact on the quality of financial reporting, for example, causing recording errors in the process of making financial reports and hampering the budget design process in the following period (Cao et al., 2016; Hembarwati, 2017; Rafsanjani & Cheisviyanny, 2021). Fraud in the previous administration also occurred due to opportunities arising from the fact that the implementing officials were often late in the submission of LPJ, supported by the abuse of authority and the weak personal integrity of the village government. The reason for this delay is that there are too many activities in the traditional village, and the implementing officials work based on ngayah, so the LPJ is not completed on time and is not recorded in the financial statements for the relevant period. The unrecorded LPJs lead to the preparation of fictitious monthly accountability reports, as cash inflows and outflows are not correctly recorded. This proves that good financial management and accurate presentation of accountability reports do not guarantee that the village government is free from fraud, as this is a matter of honesty.

It needs to be emphasized that the management system mechanism of the Balinese Traditional Village is indeed carried out using the ngayah system because ngayah is an ancestral customary order that prioritizes the religious work and must be carried out with sincerity (Putri & Candra, 2018). Ngayah is an obligation that humans must carry out. Implementing Karma Marga means dedication and sincere intention to carry out tasks responsibly, including respecting time and reporting well (Suharta & Parwati, 2022). The meaning of ngayah is not limited to human relationships; it is also related to vertical relationships with God (Dharmawan, 2020; Pradheksa et al., 2023). Karma Marga also means that every human being does not work for his benefit and is not tied to the results of his work; work is a form of devotion to God (David, 2018; Pudja, 2010). Karma Marga will lead traditional village governments not to be fixated on payment for doing professional work (such as making LPJ on time and providing good accountability) in traditional villages. The traditional village government does not yet understand that ngayah means professionalization in work, where ngayah is devotion and a sincere intention to be responsible by doing work well, including respecting time and delivering good quality work (Suharta & Parwati, 2022). Professionalism can also be measured not only by providing appropriate payments (salaries) but also by quality in financial management and good accountability practices. This is because professionalism in traditional villages differs from professionalism in the private sector, which is always related to material things. Professionalism in traditional villages is more concerned with spiritual and cultural aspects and devotion to Tri Hita Karana (Ardana et al., 2020; Gede et al., 2016). Therefore, the meaning of ngayah, which has shifted towards materialism, must return to the true meaning of ngayah, namely, working as a sincere dedication to fixing the problem of delays in the submission of LPJ.

5 Discussion and Conclusions

Based on these findings, this research seeks to build a synergy to restore the shifting spiritual and cultural meanings in the Jimbaran traditional village’s accountability practices through the Catur Marga’s values. How can the Catur Marga accountability model solve this problem?

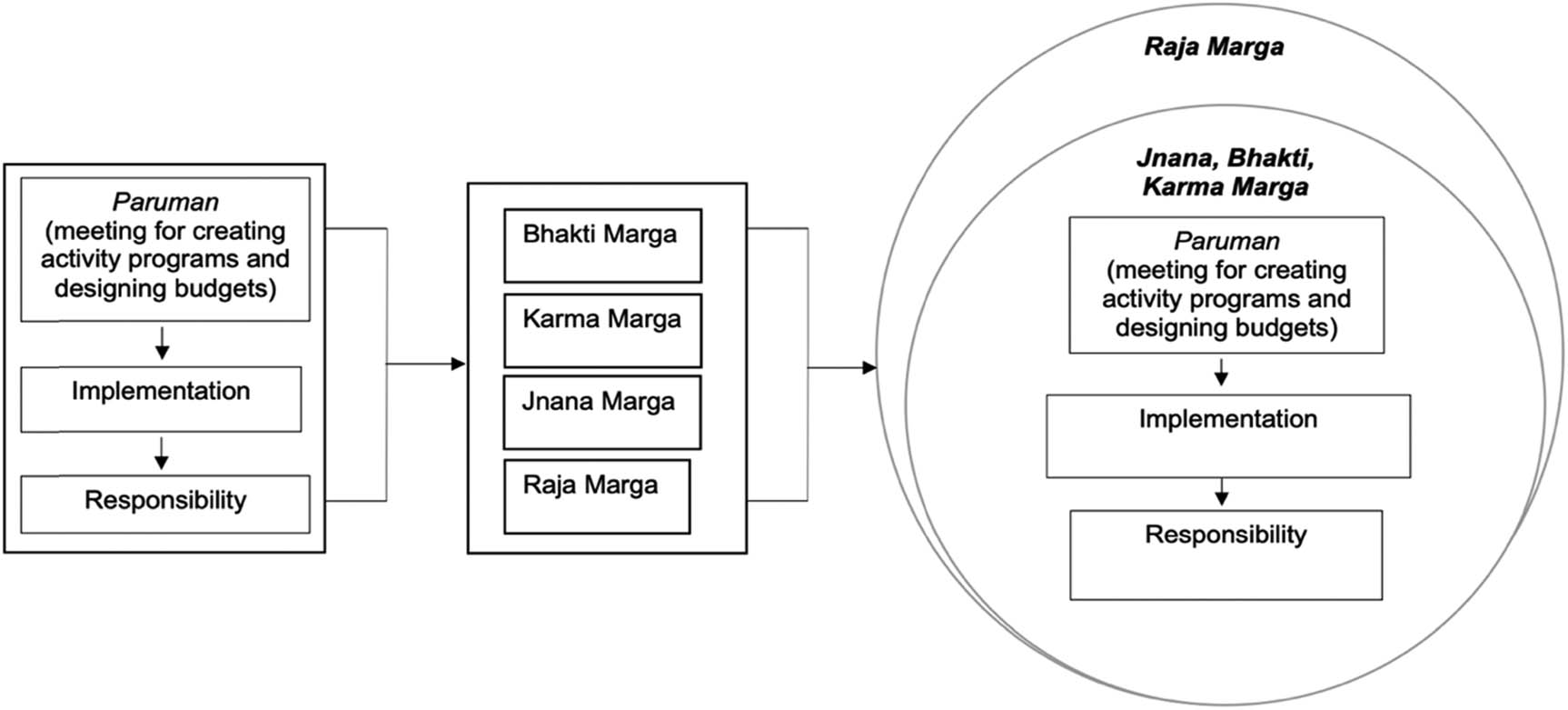

Synergizing Catur Marga into Traditional Village Accountability Practices (Figure 4) by applying Catur Marga values to all accountability practices in traditional villages. The routine activity of the Jimbaran traditional village government is to manage the finances of the traditional village. Good governance, according to applicable rules, must be transparent and accountable. However, accountability is seen not only as a form of accountability to fellow humans but also to God because accountability practices are accountable in this world and its afterlife (Prasetio & Sabihaini, 2023). As explained by Randa et al. (2011) in their research, accountability can concern a person’s responsibility to God, which is transcendent or spiritual. This spiritual aspect goes beyond just accountability between two parties but includes the relationship of an individual or organization with God. Jacobs and Walker (2004) also explained that accountability could be interpreted and implemented as something transcendent, namely, the personal relationship between God and humans, individually and organizationally, so that individuals or organizations can act according to the spiritual values they believe in. If associated with the traditional village government, the spiritual element in the government officials or the traditional village government can be a strong internal supervisor, which will encourage the traditional village government to act with more accountability and integrity in the financial management of the traditional village. Tyas et al. (2019) also argue that in a company or organization, there must be accountability in the form of spirituality as an internal responsibility that exists in human beings. This accountability includes the responsibility of the individual in the company or organization for everything he does, in the sense of deeds that are only known and understood by the individual because all acts of spiritual accountability are based on the individual’s relationship with God.

Synergizing Catur Marga into traditional village accountability practice. (Source: prepared by Authors, 2024).

In addition, accountability contains moral value principles from social aspects that are practiced, usually taught in traditional culture and religion, leading to ethical behavior in accountability practices (Roberts & Scapens, 1985; Suryaningrum, 2011). Integrating spiritual and cultural knowledge (paravidya) and material knowledge (aparavidya) is important because it will connect traditional village governance with a deeper dimension. This can help increase their integrity and dedication to their duties and responsibilities. Accountability practices will be carried out by increasing self-awareness of the obligation to provide accountability to God and the community and increasing community trust in traditional village government. Paravidya also creates self-control that emphasizes spiritual awareness, which allows them to see and understand traditional village financial management from a broader perspective, with the awareness that their actions have consequences outside the material world (Airlangga et al., 2021; Vaughan, 2002; Wijana, 2023).

Based on several opinions regarding the spiritual element in accountability, strengthening and awareness of the spiritual element in the traditional village government in Bali is an important challenge that must be carried out. This will be able to have a significant positive impact, including improving the ethics and integrity of the leadership of traditional village officials, strengthening a more thoughtful decision-making process and being in line with the values of spiritual traditional culture in the community, encouraging the provision of public services that are more responsive, sincere, and oriented to the needs of the community, increase community participation and empowerment in development and decision-making, especially related to finance in traditional villages, and maintaining the preservation of culture, traditions, and the integrity of Indigenous people’s lives. Catur Marga culture is a derivative of Hindu spiritual teachings, which has the meaning of a path to success to achieve harmony in the traditional village, which will develop moral and ethical values that can be a guideline for the traditional village government officials to strengthen their self-awareness in carrying out their work obligations. In this way, they can improve the practice of accountability from a spiritual point of view to carry out self-transformation, which makes their lives more meaningful by finding holistic happiness (Adiputra, 2003; Ningsih & Yudi Prastiwi, 2019).

The accountability practices of the Jimbaran traditional village government, built on spiritual and cultural elements, can help officials achieve holistic accountability and overcome the tendency of worldly interests. Traditional village government officials must work together to have a strong spirit and determination to dedicate themselves to the welfare of traditional villages as a form of devotion to God Almighty. Jayasinghe and Soobaroyen (2009) stated that the religious spirit historically built from local culture in the community is an important part of the accountability practice because it will dominate the actions it takes based on ethical and moral values. This religious spirit certainly requires the solidarity and awareness of the traditional village government officials to advance the welfare of all aspects of the Tri Hita Karana in the traditional village (Kristiyanto, 2010). By raising this awareness, the traditional village government can maintain the balance and harmony of the Tri Hita Karana aspect in the accountability of the traditional village’s financial management, uphold the values of indigenous culture and the environment, and achieve development goals that align with God’s teachings. As a result, this awareness will restore the meaning of ngayah culture and the shift of the implementation of parahyangan culture.

This awareness can be raised by synergizing Catur Marga into the practice of accountability for the financial management of the Jimbaran traditional village by:

First, in preparing activity plans, budgeting, implementation, and accountability are carried out in the meeting, not only involving community representatives but also religious leaders and traditional village elders as a form of devotion and transparency in carrying out the financial management of traditional villages. There must be regular meetings to align the vision and mission regarding strengthening ngayah motivation to overcome delays in submitting LPJ. Ngayah is very tied to disciplinary actions because ngayah is part of the Karma Marga. Kinsley (1982) explains that Karma is a disciplinary act that involves acting without caring about the outcome of the action, letting go of the ego’s desires that exist in oneself. All actions are done without thinking about the result or consequences. This discipline is also related to professional actions. Traditional village government officials must understand that ngayah is a professional job, and the result of ngayah is not material but a reward or practice that will bring blessings and peace in life and the hereafter. Jacobs (2005) argues that a very religious person has a viewpoint that is always based on spiritual understanding, so the accounting practices and accountability that he does will be interpreted from the spiritual side. Therefore, through these regular meetings, the perspective of ngayah in the traditional village government officials must be able to be returned to the original meaning of ngayah itself, namely, as a form of worship and devotion to God, the community, and the environment.

Second, the traditional village government officials must continue to enhance their knowledge of the implementation of aspects of traditional and spiritual culture by holding dharmawacana (learning and enlightenment about spiritual teachings) by religious leaders or traditional stakeholders, as well as increasing knowledge about accounting management by requesting assistance and training from DPMA and MDA. This increase in knowledge is carried out to synergize paravidya and aparavidya, which the Indigenous village government owns. By having a paravidya, the implementation of all aspects of Tri Hita Karana will be carried out with complete confidence in God as a form of devotion to maintaining the harmony of traditional villages and as a self-controller so that they always have integrity, ethics, and morals in carrying out financial management accountability practices. Bovens (2007) in his research explains that accountability is not only formal (involving official mechanisms such as audits) but also informal. This informal accountability involves moral and ethical relationships with higher entities like God. This informal accountability can be stronger because it is based on the deep beliefs and values embraced by the individual. Thus, accountability practices will be carried out with high morality that can encourage the traditional village government to prioritize the welfare of the traditional village above personal interests, thereby preventing the emergence of corrupt behavior or abuse of authority over the managed budget (Herli, 2019).

Finally, the traditional village government can form a Pararem (customary regulation) on the financial management of traditional villages by synergizing administrative and technical practices and strengthening understanding of the importance of traditional and spiritual culture. The aim of establishing this pararem is not only to regulate the technical practices of financial management but also to strengthen the morality and spiritual mentality of traditional village government officials, protect traditional village government officials from all egos related to personal interests, deepen the knowledge of traditional culture and spirituality of traditional village government officials, uniting understanding and perception between traditional village government officials in managing traditional village finances based on devotion to God Almighty, realizing that the accountability practices they carry out are a form of responsibility to God, and prioritizing service with love in all aspects of Tri Hita Karana as a form of devotion to God. For example, in the planning and budgeting rules, there is always a dharmawacana agenda on the sidelines of the activity program, with the theme of strengthening traditional and spiritual culture. Furthermore, the pararem can also regulate the emphasis on the meaning of working based on ngayah, namely, sincerity, devotion, and commitment to carrying out financial management with a professional attitude. Also, in the monthly accountability meeting, there must be an additional agenda, a small opening that discusses the importance of balance between material and spiritual aspects of life.

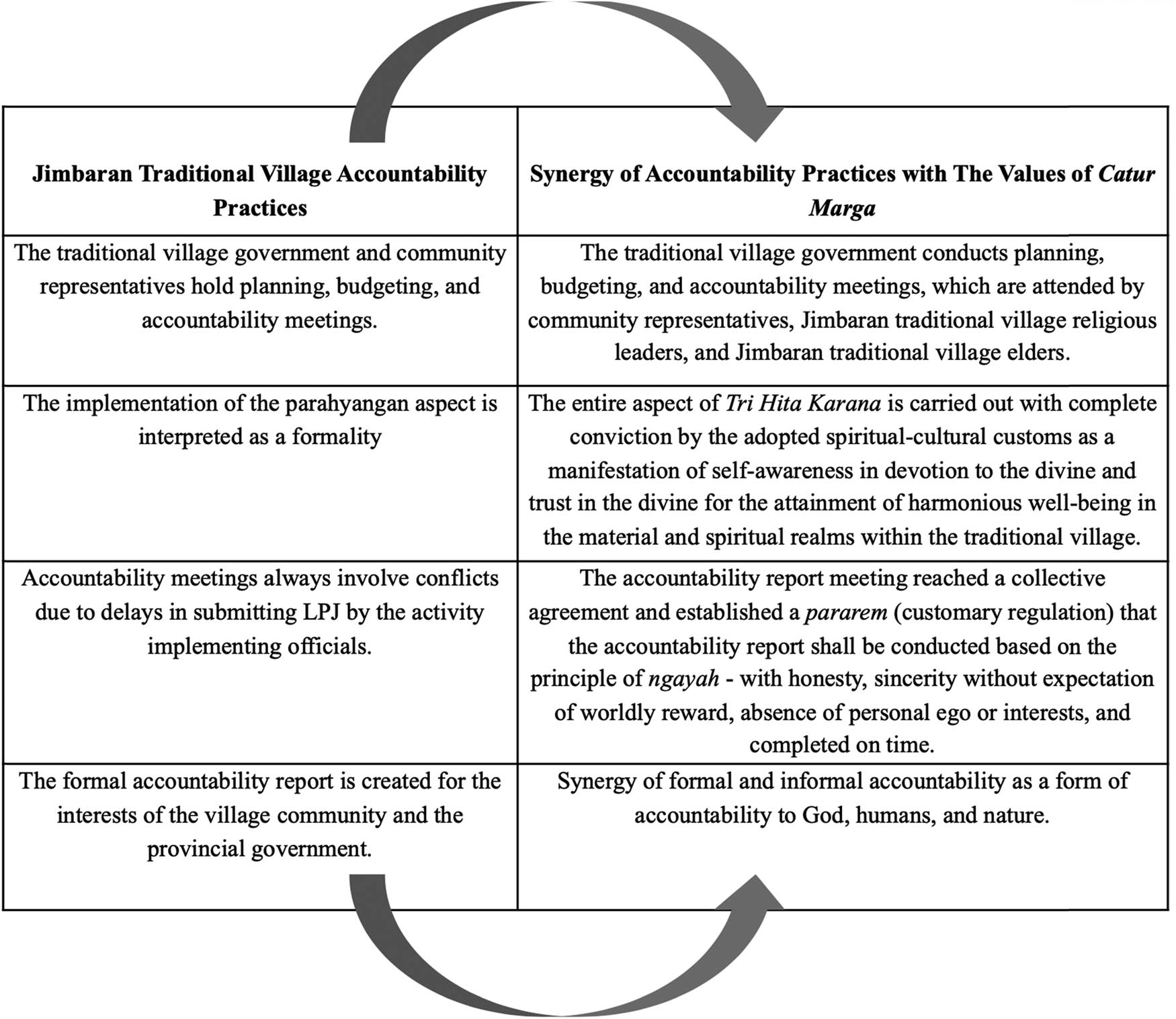

Figure 5 shows the difference between current practices and practices based on Catur Marga values.

The difference between current practices and practices based on Catur Marga values. (Source: prepared by Authors, 2024).

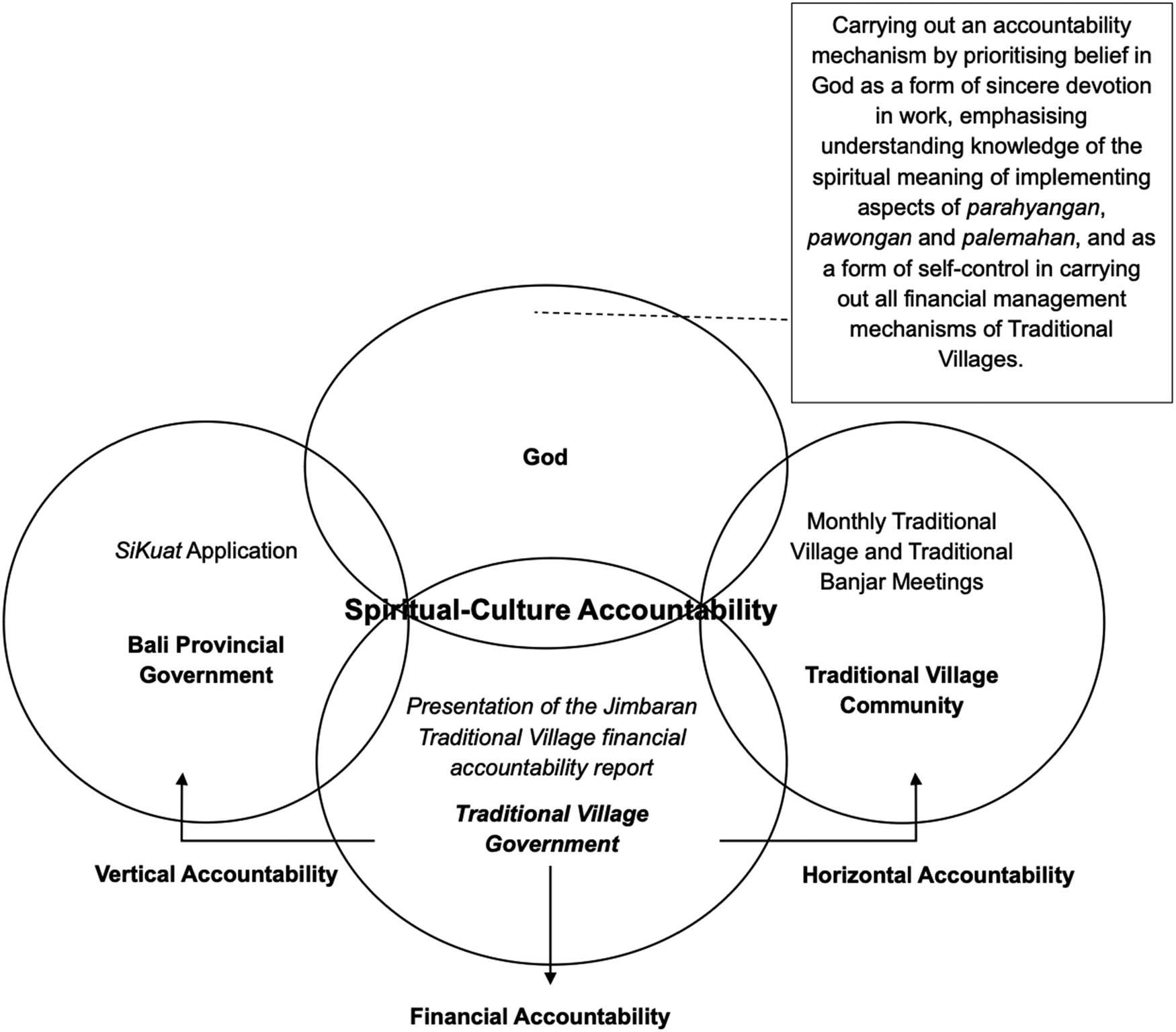

Based on Figure 5, it can be concluded that when improvements in financial management techniques are synergized with strengthening the spiritual side, traditional village government officials will be able to take a successful path to the prosperity of traditional villages in terms of economy, society, and culture. As previously explained in Figure 3, the accountability practices of the Jimbaran traditional village are carried out only in terms of financial accountability (vertical and horizontal). In contrast, the Catur marga-based accountability model will include spiritual aspects that protect all aspects of accountability practices in traditional villages. Figure 6 shows a model of accountability practice based on Catur Marga.

The Catur Marga-based spiritual accountability model. (Source: prepared by Authors, 2024).

The figure of the Catur Marga-based spiritual culture accountability model (Figure 6) is in all aspects of accountability in traditional villages. This model will strengthen spiritual harmony in traditional villages, such as the meaning contained in Tri Hita Karana, which creates balance and harmony between humans, nature, and God (Yusuf & Praptika, 2023). This Catur Marga-based accountability model can help overcome the problems of accountability practices in financial management in the Jimbaran traditional village by providing more spiritual culture reinforcement in the traditional village government environment. The presence of spiritual values in the financial management of traditional villages will encourage honesty and belief in the truth in giving responsibility openly (Rini et al., 2017). Evans (2019) argues that accountability is closely related to genuine trust, which involves a commitment to being accountable to God and oneself. The traditional village government must commit that accountability is a responsibility for the actions taken toward God and oneself. In other words, when the traditional village government officials act based on sincere dedication, the welfare of the traditional village and their happiness will be achieved. Conversely, by prioritizing their ego over the welfare of the traditional village, acts of corruption will recur, impacting the welfare of the traditional village and themselves (both Sakala and Niskala punishment).

In addition, the religious spirit presented by Jayasinghe and Soobaroyen (2009) will increase the credibility of managers and public trust in managers, which is also related to accountability practices. It can be interpreted that when the Jimbaran traditional village government officials have a religious spirit in carrying out financial management through spiritual values, it will restore the credibility and trust of the community, which was once tainted by fraud cases. On the other hand, when traditional villages implement accountability practices that are in synergy with Catur Marga, this can become part of the traditional village’s identity that is difficult to change or ignore and can strengthen the spiritual-cultural elements that exist in the village. This practice will influence the entire traditional village management system in the current and future periods and create traditional village management wrapped in a strong and sustainable spiritual culture (Dewi et al., 2023). Catur Marga-based accountability model can help Jimbaran traditional village government officials improve their financial management system by strengthening honesty, ethics, morality, and integrity, as well as increasing positive knowledge about financial management so that there is no more fraud and delays in making accountability reports.

The results of this research contribute to the consideration of decision-making and self-awareness of traditional village governments on the practice of accountability that must be carried out to achieve holistic accountability from both the technical and spiritual aspects. It also serves as input for local governments, the Village Community Empowerment Agency (MDA), and the Village Community Empowerment Council (DPMA) on achieving the welfare of traditional villages to be free from corruption through Catur Marga accountability. On the other hand, although it was previously mentioned that Catur Marga has a universal meaning, Catur Marga also has challenges and limitations in its application. For example, if one wants to synergize the meaning of Catur Marga in the accountability of profit-oriented organizations, it will undoubtedly have challenges and limitations. Synergizing the meaning of Ngayah as Karma Marga and Bhakti Marga will be challenging to apply to profit-oriented organizations because the work culture in such profit-oriented organizations is different from that of traditional village governments, which are nonprofit and closely related to local spiritual culture. Nevertheless, future researchers are expected to be able to conduct further research by involving other traditional village governments in Bali, which certainly have different characteristics, such as traditional villages in remote areas with a vital element of spiritual culture, or in administrative villages, or even local governments, to validate the universal application of the Catur Marga model in the government system.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the Brawijaya University Accounting Doctoral Program for permitting us to conduct this research. We also thank and appreciate the Jimbaran Village government officials and all informants who have shared their experiences and knowledge. However, the authors bear full responsibility for this paper.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by the Indonesian Education Scholarship (BPI) under the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP).

-

Author contributions: The authorship contributions for this manuscript are as follows: Anak Agung Istri Pradnyarani Dewi contributed to conceptualized the study, collecting data, analyzing and interpreting data, and original draft preparation. Made Sudarma contributed to conceptualizing the study, contributed to the methodology, original draft preparation, review, and editing. Ali Djamhuri contributed to conceptualizing the study, contributed to the methodology, interpreting data, original draft preparation, reviewing and editing. Wuryan Andayani contributed to conceptualizing the study, contributed to the methodology, and reviewing. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and all authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of this manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that the authors have no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data used in supporting the findings are included within the article.

References

Adiputra, I. G. R. (2003). Pengetahuan Dasar Agama Hindu. STAH Dharma Nusantara.Search in Google Scholar

Agung, A. A. G., Sudiarta, I. G. P., & Divayana, D. G. H. (2018). The quality evaluation of school management model based on balinese local wisdom using weighted product calculation. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology, 96(19), 6570–6579.Search in Google Scholar

Airlangga, A. J., Sayekti, Y., & Prasetyo, W. (2021). Revealing socio-spiritual accountability in church cooperative management (Phenomenological Studies). American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Science (ARJHSS), 11, 28–34.Search in Google Scholar

Almutawallid, S., & Santalia, I. (2024). Etika Kepada Tuhan, Manusia, dan Lingkungan. Jurnal Filsafat Indonesia, 7(1), 103–109.10.23887/jfi.v7i1.65290Search in Google Scholar

Ardana, I. K., Maunati, Y., Budiana, D. K., Zaenuddin, D., Gegel, I. P., Kawiana, I. P. G., Muka, I. W., & Wibawa, I. P. S. (2020). Pemetaan Tipologi dan Karakteristik Desa Adat di Bali. Cakra Media Utama.Search in Google Scholar

Arimbawa, W., & Santhyasa, I. K. G. (2010). Perpektif Ruang Sebagai Entitas Budaya Lokal Orientasi Simbolik Ruang Masyarakat Tradisional Desa Adat Penglipuran, Bangli-Bali. Local Wisdom: Jurnal Ilmiah Kajian Kearifan Lokal, 2(4), 1–9.Search in Google Scholar

Ashari, M. R., & Riharjo, I. B. (2019). Peran Akuntansi dalam Mewujudkan Good Governance (Studi pada Dinas Tenaga Kerja Kota Surabaya) Ikhsan Budi Riharjo Sekolah Tinggi Ilmu Ekonomi Indonesia (STIESIA) Surabaya. Jurnal Ilmu Dan Riset Akuntansi, 8(1), 1–20.Search in Google Scholar

Atmadja, A. T., & Saputra, K. A. K. (2018). Determinant factors influencing the accountability of village financial management. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 17(1), 1–9.Search in Google Scholar

Atmadja, I. N. B., & Atmadja, A. T. (2008). Ideologi Tri Hita Karana – Neoliberalisme = Vilanisasi Radius Kesucian Pura (Perspektif Kajian Budaya) dalam Dinamika Sosial Masyarakat Bali Cetakan I (editor I Wayan Ardika, dkk). Swasta Nulus.Search in Google Scholar

Bali Post. (2017, 29 August). Pelaku Korupsi Dana BKK di Songan Dilimpahkan ke Kajari. Retrieved October 30, 2023, from https://www.balipost.com/news/2017/08/29/19801/Pelaku-Korupsi-Dana-BKK-di.html.Search in Google Scholar

Bali Post. (2023, 27 October). Kejari Bangli Usut Dua Dugaan Korupsi. Retrieved October 30, 2023, from https://www.balipost.com/news/2023/10/27/370432/Kejari-Bangli-Usut-Dua-Dugaan.html.Search in Google Scholar

Berita Bali. (2018, 29 September). Laksanakan Tugas, Bendesa Adat Mesti Berpegangan pada Catur Marga. Retrieved October 30, 2023, from https://www.beritabali.com/news/read/laksanakan-tugas-bendesa-adat-mesti-berpegangan-pada-catur-marga#google_vignette.Search in Google Scholar

Bovens, M. (2007). Analysing and assessing accountability: A conceptual framework1. European Law Journal, 13(4), 447–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00378.x.Search in Google Scholar

Budiadnya, I. P. (2019). Tri Hita Karana Dan Tat Twam Asi Sebagai Konsep Keharmonisan Dan Kerukunan. Widya Aksara: Jurnal Agama Hindu, 23(2), 1–8.10.54714/widyaaksara.v23i2.38Search in Google Scholar

Cao, J., Chen, F., & Higgs, J. L. (2016). Late for a very important date: Financial reporting and audit implications of late 10-K filings. In Review of accounting studies (Vol. 21, Issue 2). Springer. doi: 10.1007/s11142-016-9351-5.Search in Google Scholar

Chang, Y., Chen, H., Cheng, R. K., & Chi, W. (2019). The impact of internal audit attributes on the effectiveness of internal control over operations and compliance. Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics, 15(1), 1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcae.2018.11.002.Search in Google Scholar

CNN Indonesia. (2024, 2 May). Kejati Bali OTT Kepala Desa Adat Berawa Diduga Peras Investor Rp10 M. Retrieved May 5, 2024, from https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20240502185029-12-1093207/kejati-bali-ott-kepala-desa-adat-berawa-diduga-peras-investor-rp10-m.Search in Google Scholar

Damayanti, S. (2017). Studi Etnometodologi atas Strategi Mempraktikkan Akuntabilitas untuk Menjaga Keberlanjutan Lembaga Swadaya Masyarakat (Doctor’s thesis). http://repository.ub.ac.id/id/eprint/305/.Search in Google Scholar

David, W. K. (2018). Colonial transformation and Asian religions in modern history. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Dewatapos, R. (2021, 5 May). Gunakan Dana Desa Adat Penarukan, Mantan Pengurus Resmi Ditahan. Retrieved October 30, 2023, from https://dewatapos.com/gunakan-dana-desa-adat-mantan-pengurus-desa-adat-penarukan-resmi-ditahan/.Search in Google Scholar

Dewi, A. A. I. P., Sudarma, M., Djamhuri, A., & Andayani, W. (2023). Regional financial governance reform in Indonesia through the Arthashastra Perspective. Southeast Asian Journal of Economics, 11(2), 169–197.Search in Google Scholar

Dharma, A. A. S. (2023). New Public Service Sebagai Paradigma Administrasi Publik Pengawasan Obat dan Makanan. Eruditio: Indonesia Journal of Food and Drug Safety, 3(1), 29–37. doi: 10.54384/eruditio.v3i1.128.Search in Google Scholar

Dharmawan, I. G. A. (2020). Bhakti Marga Yoga: Implementasi dalam Kehidupan Pribadi dan Sosial. Bawi Ayah: Jurnal Pendidikan Agama Dan Budaya Hindu, 11(2), 70–87.Search in Google Scholar

Dharmawan, N. A. S., & Yudantara, I. G. A. P. (2020). Accountability Based on Tri Hita Karana (THK) in Sangsit Village (Vol. 158, pp. 291–295). doi: 10.2991/aebmr.k.201212.041.Search in Google Scholar

Djamhuri, A. (2011). Ilmu Pengetahuan Sosial Dan Berbagai Paradigma Dalam Kajian Akuntansi. Jurnal Akuntansi Multiparadigma, 2(1), 147–185.10.18202/jamal.2011.04.7115Search in Google Scholar

Dubnick, M. (1998). Clarifying accountability: An ethical theory framework. In C. Sampford, N. Preston, & C. A. Bois (Eds.), Public sector ethics: Finding and implementing values. The Federation Press/Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Ebrahim. (2003). Making sense of accountability: Conceptual perspectives for northern and Southern Non-profits. Non-profit Management & Leadership, 14(2),191–212.10.1002/nml.29Search in Google Scholar

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57–74. doi: 10.2307/258191.Search in Google Scholar

Evans, C. S. (2019). Kierkegaard and spirituality: Accountability as the meaning of human existence. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.Search in Google Scholar

Freund, P., & dan Abrams, M. (1976). Ethnomethodology and Marxism: Their use for critical theorizing. Theory and Society, 3(3), 377–393.10.1007/BF00159493Search in Google Scholar

Garfinkel, H. (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. Prentice-Hall.Search in Google Scholar

Gede, I., Wirga, I. W., & Suryadi, I. (2016). Model Pemberdayaan Desa Adat Pada Dua Desa Tujuan Wisata Di Bali (Studi Komparatif Desa Adat Intaran Dan Kuta). Jurnal Bisnis Dan Kewirausahaan, 12(1), 62–67. http://ojs.pnb.ac.id/index.php/JBK/article/view/33.Search in Google Scholar

Ghazali, M. Z., Rahim, M. S., Ali, A., & Abidin, S. (2014). A preliminary study on fraud prevention and detection at the state and local government entities in Malaysia. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 164, 437–444. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.11.100.Search in Google Scholar

Gray, R., Owen, D., & Maunders, K. (1987). Corporate social reporting: Accounting and accountability. Prentice Hall.10.1108/EUM0000000004617Search in Google Scholar

Hanisa, N. (2023). Akuntabilitas Pengelolaan Dana Desa Berbasis Budaya Lokal Siri’ Na Pacce Dalam Pencegahan Fraud (Thesis). http://repository.umpalopo.ac.id/3722/.Search in Google Scholar

Hembarwati, A. (2017) Dampak Keterlambatan Penyampaian Laporan Pertanggungjawaban Terhadap Penyajian Laporan Keuangan Kantor Pelayanan Perbendaharaan Negara Surabaya II Sebagai UAKBUN Daerah (Thesis). http://eprints.perbanas.ac.id/4224/.Search in Google Scholar

Herli, M. (2019). Are spiritual management and accountability able to improve village financial management for the better? Case in Sumenep Regency, Indonesia. KnE Social Sciences, 3(11), 399. doi: 10.18502/kss.v3i11.4023.Search in Google Scholar

Indonesia Corruption Watch. (2022). Tren Penindakan Kasus Korupsi Tahun 2021. https://www.antikorupsi.org/id/tren-penindakan-kasus-korupsi-tahun-2021.Search in Google Scholar

Indonesia Corruption Watch. (2023). Tren Penindakan Kasus Korupsi Tahun 2022. https://www.antikorupsi.org/id/tren-penindakan-kasus-korupsi-tahun-2022.Search in Google Scholar

Indonesia Corruption Watch. (2024). Tren Penindakan Kasus Korupsi Tahun 2023. https://www.antikorupsi.org/id/tren-penindakan-kasus-korupsi-tahun-2023.Search in Google Scholar

Jacobs, K. (2005). The sacred and the secular: Examining the role of accounting in the religious context. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 18(2), 189–210. doi: 10.1108/09513570510588724.Search in Google Scholar

Jacobs, K., & Walker, S. P. (2004). Accounting and accountability in the Iona Community. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 17(3), 361–381.10.1108/09513570410545786Search in Google Scholar

Jayasinghe, K., & Soobaroyen, T. (2009). Religious “spirit” and peoples’ perceptions of accountability in Hindu and Buddhist religious organizations. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 22(7), 997–1028. doi: 10.1108/09513570910987358.Search in Google Scholar

Jayendra, P. S. (2017). Ajaran Catur Marga Dalam Tinjauan Konstruktivisme Dan Relevansinya Dengan Empat Pilar Pendidikan Unesco. Jurnal Penelitian Agama, 3(1), 73–84. https://ejournal.ihdn.ac.id/index.php/vs/article/download/329/291.Search in Google Scholar

Jensen, M. C., & dan Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the Firm: Managerial behavior, agency cost and ownership’s structure. Journal of Financial Economics, October, 3(4), 305–360.10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-XSearch in Google Scholar

Joannides, V. (2012). Accountability and the problematics of accountability. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 23(3), 244–257.10.1016/j.cpa.2011.12.008Search in Google Scholar

Juniartha, M. (2020). Praktik Spiritual Sebagai Komoditi Sosial Dalam Era Globalisasi. Widya Genitri: Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan, Agama Dan Kebudayaan Hindu, 11(1), 29–43. doi: 10.36417/widyagenitri.v11i1.346.Search in Google Scholar

Jurana, J., Indriasari, R., Totanan, C., Parwati, N. M. S., Mayapada, A. G., & Pakawaru, M. I. (2022). Basic environmental accountability in the yadnya ceremony in Malakosa Village, Indonesia. AMCA Journal of Community Development, 2(1), 1–6. doi: 10.51773/ajcd.v2i1.89.Search in Google Scholar

Kamayanti, A., & Ahmar, N. (2019). Tracing accounting in Javanese tradition. International Journal of Religious and Cultural Studies 1(1), 15–24. doi: 10.34199/ijracs.2019.4.003.Search in Google Scholar

Kamayanti, A. (2015). Paradigma Penelitian Kualitatif Dalam Riset Akuntansi: Dari Iman Menuju Praktik. Infestasi, 11(1), 1–10. https://ecoentrepreneur.trunojoyo.ac.id/infestasi/article/view/1119.Search in Google Scholar

Kamayanti, A. (2016). Fobi(a)kuntansi: Puisisasi Dan Refleksi Hakikat. Jurnal Akuntansi Multiparadigma, 7, 1–16. doi: 10.18202/jamal.2016.04.7001.Search in Google Scholar

Kamayanti, A. (2017). Akuntan (Si) Pitung: Mendobrak Mitos Abnormalitas dan Rasialisme Praktik Akuntansi. Jurnal Riset, 3(2), 171–180. doi: 10.18382/jraam.v2i3.176.Search in Google Scholar

Karmini, N. L. (2022). Factors That Influence Expenditure of the Manusa Yadnya in Bali Province. Baltic Journal of Law & Politics 15(3), 1604–1613. doi: 10.2478/bjlp-2022-002111.Search in Google Scholar

Kinsley, D. R. (1982). Hinduism: A cultural perspective. Prentice-Hall.Search in Google Scholar

Kosec, K., & Wantchekon, L. (2020). Can information improve rural governance and service delivery? World Development, 125, 104376. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.07.017.Search in Google Scholar

Kristiyanto, A. E. (2010). Spiritualitas Sosial: Suatu Kajian Kontekstual. Kanisius.Search in Google Scholar

Kurniawan, P. S. (2016). Peran Adat Dan Tradisi dalam Proses Transparansi dan Akuntabilitas Pengelolaan Keuangan Desa Pakraman (Studi Kasus Desa Pakraman Buleleng, Kecamatan Buleleng, Kabupaten Buleleng, Provinsi Bali). Seminar Nasional Riset Inovatif, 4, 485–515.Search in Google Scholar

Kusdewanti, A. I., & Hatimah, H. (2016). Membangun Akuntabilitas Profetik. Jurnal Akuntansi Multiparadigma, 7(2), 223–239.10.18202/jamal.2016.08.7018Search in Google Scholar

Lehman, G. (2005). A critical perspective on the harmonisation of accounting in a globalising world. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 16(7), 975–992.10.1016/j.cpa.2003.06.004Search in Google Scholar

Lehman, G., & dan Kuruppu, S. C. (2017). A framework for social and environmental accounting research. Accounting Forum, 41(3), 139–146.10.1016/j.accfor.2017.07.001Search in Google Scholar

Liu, R., & Wong, T. (2018). Urban village redevelopment in Beijing: The state-dominated formalization of informal housing. Cities, 72, 160–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2017.08.008.Search in Google Scholar

Ludigdo, U., & Kamayanti, A. (2012). Pancasila as accountant ethics imperialism liberator. World Journal of Social Sciences, 2(6), 159–168.Search in Google Scholar

Lutfillah, N. Q. (2016). Akuntansi Gayatri Dalam Perluasaan Wilayah Kekuasaan Kerajaan Majapahit (Doctor thesis). http://repository.ub.ac.id/id/eprint/160576/.Search in Google Scholar

Maulana, A., & Bakri, B. (2023). Menggali Makna Akuntabilitas Organisasi Berdasarkan Tafsir Tasawuf Bugis “Dua Temmassarang Ritellue Temmallaiseng.” Jurnal Akademi Akuntansi, 6(2), 242–256. doi: 10.22219/jaa.v6i2.22991.Search in Google Scholar

Meng, X., & Zhang, L. (2011). China economic review democratic participation, fiscal reform and local governance empirical evidence on Chinese villages. China Economic Review, 22(1), 88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2010.09.001.Search in Google Scholar

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1992). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Method. Terjemahan Tjetjep Rohendi Rohidi. Analisis Data Kualitatif: Buku Sumber tentang Metode-metode Baru. Universitas Indonesia (UI-PRESS).Search in Google Scholar

Miller, J. L. (2002), The board as a monitor of organizational activity: The applicability of agency theory to nonprofit boards. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 12, 429–450.10.1002/nml.12407Search in Google Scholar