Abstract

Physiognomy finds itself in a strange position. On the one hand, it is considered false and even dangerous by common sense as a pseudo-scientific theory; on the other hand, it is implicitly practiced by everyone every day (Brandt 1980. Face reading. The persistence of physiognomy. Psychology Today 14(7). 90–96). This situation calls for an explanation. After a brief discussion of the problems of classical physiognomic theories, I will show how they embody the equational model of the sign and how this perspective helps in the understanding of why physiognomy have proved to be false. I will then introduce two recent articles by Dumouchel (2022. Making faces. Topoi 41. 631–639) and Crippen and Rolla (2022. Faces and situational agency. Topoi 41. 659–670) that address the perception of faces from a situated and ecological point of view. I will argue that these theories embody the inferential model of the sign, thus paving the way for a new science of the face.

1 Introduction

Physiognomy finds itself in a strange position. On the one hand, it is considered false and even dangerous by common sense as a pseudo-scientific theory; on the other hand, it is implicitly practiced by everyone every day (Brandt 1980). As stated by Allport (1937) and repeated by Alley (1983) more recently, the literature on physiognomy is striking for its quantity rather than quality. Yet, some physiognomic judgments are truthful, in a sense to be specified, otherwise speakers would not continue to express them (Alley 1983; Dumouchel 2022). This situation calls for an explanation. In the present paper I intend to provide the theoretical basis for such an explanation. I will start with a brief discussion of the problems of traditional physiognomic theories. Then, I propose to interpret physiognomic theories in the light of an important semiotic distinction, that between the equivalence and the inferential model of the sign (Eco 1984: 26–28; Manetti 1987), suggesting that if physiognomic theories have been shown to be false, it has to do with the fact that they are based on an implicit semiotic theory that sees the relationship between sign and meaning as a fixed relationship (equivalence) between facial signs and primitive, internal character traits or mental states. From this point of view, it is no accident that criticisms raised against physiognomic theories are structurally the same as those raised by Eco and other semioticians against the equivalence model.

I will then apply the other pole of the distinction to interpret some recent literature on the ecological psychology of face perception. According to this literature, there is evidence that the production and perception of faces is strongly dependent on context (Crippen and Rolla 2022; Zebrowitz et al. 2010) and that faces are mainly tools with which we do something and that afford actions instead of being the mirror of the soul. As I will show, these theories embody the inferential semiotic model. This implies that even if facial expressions do not have an internal structure that refers to simple concepts, they do, however, have an external structure (Bellucci 2013). This, in turn, invites a reflection on faces as rhemas (either icons or indices), i.e., signs that can become part of dicisigns (Peirce’s notion for proposition).

In sum, just as Eco (1979b) recognized the connection between the history of semiotics and physiognomic theories, the semiotic interpretation of ecological theories of face perception adumbrates the possibility of a new science of facial expressions capable of explaining why some physiognomic judgments are truthful.

2 Physiognomic theories

As we will see, the distinction between the equational and inferential models of the sign is related to the nature/culture divide. The inferential model emerged from the analyses of natural signs, while the equational one from linguistic signs. It is interesting, therefore, that most physiognomic theories exemplify the equational model. The best example to see this is Aristotle’s physiognomic. According to Aristotle, linguistic signs are symbolic, referring indirectly to things, whereas the affections of the soul are icons, which refer directly to things. In this way he also explained linguistic differences: while words may be different for different people and are therefore conventional, the affections of the soul, which are the same for everyone, are not. Based on his epistemology, Aristotle’s physiognomic theory, which is presented right after his sign theory as its exemplification (Prior Analytics II 70b: 16–17), actually embodies the equational model of the linguistic sign, influencing later physiognomic theories. For Aristotle assumes that accidents transform the body and the soul at the same time; that there is only one sign for an affection of the soul; and that each genus (e.g., the lion) has its own affection and its own sign (Manetti 1987: 126). Thanks to these assumptions, Aristotle could propose physiognomy as an exact science not limited to the kind of hypothetical knowledge conveyed by natural signs, a concern shared centuries later by Lavater’s physiognomic theory (see Gray 2004).[1] The same assumptions underlie the numerous examples of bodily traits indicating character traits in the Historia Animalium and in the second book of the pseudo-Aristotelian treatise Physiognomica, for instance: “animals with a large forehead are slower, those with a small one, more lively”; “large prominent ears indicate a tendency to silly chatter and garrulousness.”

The subsequent physiognomic theories have either relaxed the assumption that a single type of physical trait should be a sign of an affection, allowing several traits to indicate the same character trait, or changed the bodily indicators and/or psychological qualities examined.

In a chapter of his book on face perception, entitled Physiognomy and social perception (1983: 168), Robert Alley distinguished four different approaches to physiognomy: (a) theories that make physiognomic judgements from comparisons between animals and humans, assuming that similarity in appearance to an animal indicates possession of the animal’s typical character trait; (b) theories that inductively infer personality from physical traits shared by an unknown person with another person whose personality is known; (c) theories that seek to correlate facial traits and common functions; and, (d) theories that seek to correlate facial expressions and emotions or mental states, taking the former as clues to the common emotional or cognitive state of an individual. Apart from the fourth approach, “the other three all assume that there are genetic relationships between facial characteristics and personality. Even if such relationships existed, training, self-discipline, or experience could modify or reverse these genetic tendencies” (Alley 1983: 169). In these cases, the relationship between the genetically encoded physical trait and the corresponding character trait is posited as independent of context and experience. Moreover, even if one considered context and experience as relevant, as in the fourth approach (d), which is based on facial expressions and muscular patterns instead of hereditary structural patterns of the body, the theory still assumes that there are universal patterns of facial expressions (an assumption supported by studies such as Darwin 1972 and Ekman and Oster 1979) that correlate with psychological qualities (for example: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise). A further assumption is that “common facial expressions produce a cumulative record in the form of detectable patterns (traces) left in the soft tissues of the face” (Alley 1983: 170).

In what follows, we will see how the fourth approach, (d), changes if the first assumption is rejected, namely through a critique of Ekman’s basic emotions theory. Alley does not criticize the first assumption but detects other problems. First of all, if for approaches (a), (b), and (c) one criticism was that in ontogeny culture and experience could modify posited correlations between facial structures and personality, in (d) structural features can bring forth individual differences in facial expressions engendered by an emotion; and a similar “masking” effect can also be produced by traces left by fake facial expressions: trivially, a person who always smiles is not necessarily a happy person (Alley 1983: 171).

Alley concluded his review by pointing out that, despite the problems, some physiognomic judgements are truthful as ordinary people continue to rely on them in social interactions. If this is the case, it is because physiognomic theory is one thing, and the origin of physiognomic judgments is another (Alley 1983: 170).

3 Situated theories of face perception

According to Alley there is a fifth approach to physiognomy that is more “reasonable and plausible” (1983: 171).

This perspective focuses on the variations in facial appearance commonly produced by biological anomalies (e.g., genetic defects), developmental processes, and environmental interactions (e.g., tanning). Stated simply, this perspective holds that physical traces of these events or states, or facial features that merely resemble such traces, will engender a reaction appropriate for typical individuals with the corresponding history or biology. (Alley 1983: 171)

In this fifth approach, physiognomy “is no longer based on special analogical, inferential, or perceptual processes,” but becomes “simply” a matter of how we perceive persons and situations. Interestingly, the same conclusion can be reached if we consider some recent proposals for studying the perception of faces, which criticize Ekman’s BET, as an amendment to the fourth approach (d) seen in the previous section.

I will address in particular two recent articles that appeared in Topoi in a volume edited by Marco Viola and Massimo Leone entitled What’s so special about faces?, one by Crippen and Rolla (2022) and the other by Dumouchel (2022). In both cases, the polemical target is Ekman’s BET. Paul Dumouchel begins by introducing a semiotic distinction: “faces made are neither mere indexes (in Pierce [sic] sense), nor readouts that directly reveal a person’s emotion or mental state” (2022: 631). Instead, faces can be conventionalized representations, such as those that can be used to tell stories: if I tell a friend about the misadventure that happened to Carlo who came face to face with a bear a week ago, and at a certain point I reproduce the expression of fright that had appeared on Carlo’s face in front of the bear, in no sense does my facial expression represent my emotion, but that which Carlo must have felt a week ago. In this sense, making faces serves as a narrative tool. They are “representations of events that are absent […] they are not readouts of the speaker’s present internal state, but representations of something that happened somewhere else at some other time” (Dumouchel 2022: 632). These kinds of faces are thus symbols, according to Peirce’s semiotics, general signs that can have different uses depending on the context. For example, my friend to whom I told Carlo’s story is likely to reproduce the same facial expression, just as one often laughs when others laugh as an act of social coordination (Paolucci and Caruana 2019; 2020).

The importance of context in the interpretation of a facial expression has also been emphasized by Crippen and Rolla. Their starting example is the well-known Kuleshov effect (Pudovkin 1926): the same facial expression changes in meaning depending on the images shown in the immediately preceding or following shots. Another example comes from the real cases of the same effect compiled by Heaven (2020):

One of them is a basketball player celebrating a slam dunk, whose expression looks pain-stricken when isolated from the context. Similarly, there are photographs of Adele receiving an award, Mexican spectators enjoying a football victory and Justin Bieber fans overcome by his presence, all of whom look sad if cut off from the broader circumstances. (Crippen and Rolla 2022: 661)

The strong thesis defended by Crippen and Rolla is not only that the context changes the meaning of a facial expression, but that it is constitutive. Further, that the perception of situated faces is direct, as in the case of affordances according to ecological psychology. As an example of the arguments for the direct perception of emotions and cognitive states, see the following one from Levin and Banaji (2006) cited in Gallagher (2020: 153):

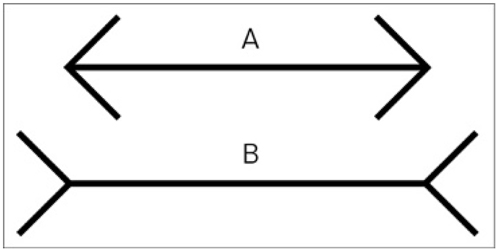

Despite the fact that all images are of the same color, we perceive faces with features stereotypically associated with a darker pigment as darker. However, these false differences are perceived directly, they do not depend on the cognitive penetration of mental representations, but on our perceptual apparatus.[2] Just like affordances to Gibson, these perceptions are neither subjective nor objective. They are perceived directly without the mediation of disembodied mental representations (1979: 129). The faces we see in Figure 1 and 2 are figurative gestalts that do not cease to operate even after we have acquired the knowledge that they are all images of the same color, just as, despite knowing that they are in fact the same, we still perceive Müller–Lyer’s arrows as being of different lengths.

From Levin and Banaji (2006).

Müller–Lyer’s optical illusion.

The notion of “physiognomic qualities” introduced in Gestalt psychology and cited by Crippen and Rolla is interesting in this respect:

The concept does not refer to expressions built up out of separate elements like a crooked nose and furrowed brow [equational model]. The term instead designates expressive wholes that are not reducible to the sum of their parts. (Crippen and Rolla 2022: 663)

To perceive a situated face is to perceive a physiognomic quality in this sense. Its meaning is determined by the context in which it is expressed, but also in relation to an observer.

Such happens when a cheerful pub district and the jovial faces of a group of revelers take on threatening tones when night falls, but more for a woman who objectively faces greater risk than her male counterpart. Here, the woman – who we will call Salma – finds herself in an unsettling public mood, as opposed to discovering a mood is inside her. (Crippen and Rolla 2022: 663)

Just like Salma, we make faces according to the situations we encounter, which can be dangerous, joyful, happy, etc. In short, emotions are properties of situations for us. Like affordances, emotions are “properties of things taken with reference to an observer but are not properties of the experiences of the observer. They are not subjective values” (Gibson 1979: 137). Similarly, the interpretation of a facial expression depends on the context and the observer.

If these kinds of physiognomic judgements are possible, it is because they are very standardized, and this is a point shared by Crippen and Rolla, Dumouchel, and Alley. Dumouchel (2022: 636) cites in particular a study by Crivelli et al. (2016) done at the Trobriand Islands (where Ekman had gone for his study on universal emotions), according to which the inhabitants of those islands tend to confuse surprise with fear. According to the authors, the confusion is not accidental, but has to do with the way frightening creatures are represented in their culture, “with a gasping face and large eyes” (Dumouchel 2022: 636). Thus, when confronted with expressions of surprise, for the Trobrianders they are instead fearful images. As Dumouchel points out, this more subtle analysis is only achievable if one has not already decided a priori that facial expressions are universal and must have a fixed meaning.

According to Dumouchel, moreover, making a face can also serve to say something about something, thus functioning as a quasi-proposition (as a conversational tool). Peirce used the same expression for his doctrine of dicisigns and his extended conception of proposition (cf. Stjernfelt 2014; and see below). According to Peirce, a dicisign is given by the co-localization (as Stjernfelt calls it) of an index, which indicates the subject of the proposition, and an icon, which functions as the predicate of the proposition. Unlike faces as narrative tools, which are highly conventionalized and deposited in the textual memory of a culture, faces as dicisigns “do not seem to have canonical expression”:

This is why, when shown still pictures of spontaneous emotions, people generally fail to recognize them correctly […]. Taken individually, out of that context, as a frozen moment of expression, the faces that we make in a conversation, unless they are conventionalized expressions (that is, narrative tools), are too diverse, fleeting and ambiguous to be interpreted properly. (Dumouchel 2022: 636)

Which does not mean that, given a context, it is impossible to interpret this type of sign. On the contrary, we find in Dumouchel’s distinction the tension between signs and contexts identified in semiotics by Eco (1979a) and Violi (1997), according to which it is not only contexts that determine the meaning of a sign, but also vice versa, depending on how much codified in a culture a given sign function is; “every term is always indexed to a standard reference context, in the sense that its typical meaning is the representation of that regularity that emerges in the standard context” (Violi 1997: 277, my translation). From this perspective a sign can be seen as a “virtual text” and a text as the “expansion” of a sign (cf. Eco 1979b: 23), a conclusion reached by Eco based on Peirce’s theory that a term can be regarded as a rudimentary proposition (or dicisign) and a proposition as a rudimentary argument.

Dumouchel’s distinction between narrative and conversational faces, according to which the former would be conventional but not the latter, is rather a difference of degree, in the same way as symbols for Peirce are general signs whose generality can be cultural or natural (cf. Bellucci 2017; Stjernfelt 2016) and vary from fixed referential relations to statistically weaker relations.

4 The inferential and equational models

I propose to divide physiognomic theories according to their semiotic structure, in relation to which sign model they embody. The reference is to the distinction between the inferential and equational models of the sign identified by Eco (1984) and Manetti (1987). In this section, I will therefore expound on this important distinction.

The distinction has its origins in the semiotic theories of classical antiquity and is due to the fact that semiotics as we know it today evolved from two different theories that, before Augustine, had always been kept separate, and that are related to the (problematic) nature/culture distinction: a semantic theory of the linguistic sign and an epistemological theory of natural or non-linguistic signs (Manetti 2010: 260).

In Aristotle, for example, the linguistic expression, defined as “voice” (ta en tei phonei), is not a sign of things but symbola, indicating the conventional nature of the relationship between voices and the affections of the soul or mental states. The latter, in turn, iconically represent the things of the world, which voices can only indirectly represent (De interpretatione 16: a3–8). Non-linguistic or natural signs are treated separately in his logico-epistemological theory, as strictly speaking-signs (semeia, or weak signs: the conclusions that can be deduced from them are only probable) or tekmerion (necessary signs; Prior analytics 70a: 6–70b: 6; cf. Manetti 1987: 105) through which it is possible to know something that is not present. In one case, the linguistic sign stands on a relationship of equivalence with the soul’s affections, of the type p = q, since if letters and sounds are not the same for everyone, the affections are the same for everyone (both for the Greeks and barbarians, De int. 16a3–8); the meaning of a linguistic term is furthermore given by its definition, which always tends to the essence and substance (Posterior analytics 90b: 30) of the things directly represented by the internal affections. To each other, definition and term are not only equivalent but fully convertible (it is possible to read the biconditional in both directions). Different from the definition is the model of inference, if p then q, on which the non-linguistic signs rest, “so much so that in the syllogism the terms are not convertible, whereas in the definition they are” (Eco 1984: 92, my translation).

Similarly, the Stoics also kept the two theories separate, and used semainomenon for the linguistic sign and semeion for non-linguistic signs.

In the linguistic model, deriving from ancient theories of language, an external sign refers strictly to its meaning (which may be a state of mind or an affection of the soul, as in Aristotle, a lekton as for the Stoics, or an idea as for Locke and later Saussure and Frege), which in turn is then conceived as synonymy and essential definition. In the sign model, on the other hand, deriving from logical theories, a sign refers by implication, more or less strongly depending on the context, to its meaning, which is not of a different nature from the source sign, but its consequent, an approach that culminates in Peirce’s semiotics whose principle of interpretation establishes that the meaning of a sign is another sign called its interpretant.

Now, classical physiognomic theories all embody the equational model of the sign. In (a), the judgment goes from large limbs = courage (as for all lions) to “individuals with large limbs are courageous,” which is easily falsified by a man with large limbs who is not courageous. That certain signs stably refer to personality is also assumed in (b), since to judge that an individual who shares some physical features with an honest man is himself honest presupposes that those features = honesty. In (c) a certain function corresponds to a personality trait, for instance, lip thickness is equated to “talkativeness.” Finally, in (d), the general idea is that the same emotions leave the same traces in the soft tissues of the face, hence wrinkled foreheads = anxiety (or an anxious person).

The problem is not only that facial expressions do not seem to share the same character of conventionality as linguistic signs (“the first truth about the face is that it is always together both natural and cultural” [Leone 2021: 11]), but also the impossibility of identifying a finite number of psychic qualities and corresponding signs that refer to them independently of context. These problems undermine Aristotle’s assumptions which were deemed necessary for physiognomy to become a science.

Notice that the fact that (a), (b), (c), and (d) embody the equational model of the sign does not imply, by itself, that any physiognomic theory that embodies the equational model is doomed to be falsified. However, it is interesting how all physiognomic theories seem to exhibit the same logical-semantic problem that Eco (1984) demonstrated for linguistic signs based on the equational model. It is not possible to repeat here Eco’s reasoning on the logical impossibility of dictionary semantics for linguistic signs. Suffice it to say that it is not possible to identify properties that can simultaneously define something and distinguish it from everything else without the same concepts, which were supposed to be primitive and finite in number, appearing in more than one definition, blowing up the difference between universal primitives (genus and species in the case of Aristotle) and accidental signs. Thus, just as it is not possible to strictly correlate a facial alteration and an emotion, similarly it is not possible to give the meaning of a sign independently of context.

From this analysis of the four physiognomic approaches, we can say that: (i) the same facial sign can have different meanings; (ii) because of (i), then the meanings of facial signs cannot be finite in number; (iii) because of (ii), then there is no difference in nature between facial signs and their meanings.

As for point (iii), in fact a further aspect unites physiognomic theories and the semantics of linguistic signs based on the equation model: in both there is the idea that a sign shall refer to something hidden or not perceptible to the senses. This is not the case in the semiotics derived from the inferential model: in antiquity the examples were “if a woman has milk in her breasts, then she has given birth,” “if sweat flows through the body, then it must be porous.” In the second example, consider how for the Stoics pores were also invisible, but this was not a reality of sweat concealed by the phenomenon of sweat, but something else in the natural world referred to by sweat as a sign. Similarly, the ecological theories of face perception that I introduced are based on a pragmatist epistemology that does not postulate anything mysterious in the mind that cannot be grasped through the senses.

5 The new science of the face

As we saw, physiognomy, if based on an ecological and situated theory of face perception, ceases to be a physiognomic theory in the classical sense and automatically becomes a theory about the origin of physiognomic judgments, just like Alley’s fifth “reasonable” approach. From this perspective, the traces and marks left on faces are not left by the activation of emotions or internal mental states (postulated as finite and the same for all), but by culture and inherited or acquired habits of response to situations.

Let’s review some examples given above from this different perspective. Regarding the example of the lion and courage, there is no doubt that the judgments “you are a lion,” “as brave as a lion,” etc., are often made, but in these cases it is not so much similarity in appearance that determines courage, but similarity in actions deemed courageous that makes an individual resemble a lion. If someone with large limbs is considered courageous because he or she resembles a lion, it is not because large limbs = courage, but because such an individual is believed to be capable of feats deemed courageous like those of the lion, which of course may not be the case. If physiognomic judgments based on resemblance to animals seem unreasonable, or metaphorical at best, the following inferences, though equally fallible, may seem more sensible: “if large limbs, then he works out a lot” (very likely if expressed in a gym); “if large limbs, then he eats a lot.” On the other hand, if physiognomic judgments such as “thick lips = talkativeness” and “large forehead = smart” seem very unreasonable, it is precisely because in our experience and culture it is not true that those things are related. However, it cannot be denied that stereotypes like “if he wears glasses, then he is smart” or “if he is Italian, then he is noisy” exist. On the other hand, the following inferences seem more reasonable: “if blue eyes, then either your father or your mother must have blue eyes”; “if you wear glasses, then you read a lot” (note that directly perceiving a social affordance or emotion in a face or situation, as is advocated by Crippen, Rolla and Dumouchel’s theories, does not mean that such perceptions are infallible, only that such perceptions are not mediated by concepts; again, see Figure 1). It is precisely because facial signs do not have a fixed meaning that we can be wrong in a physiognomic judgement. But an evolutionary argument can be given that at least some stereotypical physiognomic judgements must be truthful, otherwise people would cease, in the long run, to express them. This argument is also supported by theories such as Dumouchel’s, according to which faces are signs that we make to act and interact, not signals that we passively exhibit and that stand for our inner mental states. When physiognomic judgments work, it isn’t because the background physiognomic theory is true, but because they are based on the mechanism of the generality of signs and contexts.

From the examples, clearly physiognomic judgments come with different degrees of standardization and reliability. The possibility of being wrong implies a shift to the inferential model. According to this perspective: the meanings of a facial sign (whether a structural feature or a facial expression) can be different in different contexts; there is no finite number of possible meanings of facial expressions; there is no difference in nature between a facial sign and its meaning. Even in the case of emotions, as seen, the meaning of a facial expression is not the corresponding internal emotion, but the directly perceived emotion (without the mediation of concepts, theories of mind, or the activation of the same emotion or mental state in the mind of the interpreter) is a sign of something else: a sad face means that something has made that person sad, that if he or she is sad then he probably does not feel like joking, that if he or she is sad then I must behave in a certain way.[3]

Moving from equation to inference does not mean moving from science to pseudoscience, as per Aristotle, or from code to the ineffable. Peirce is the one who better proposed the inferential model in semiotics. As Bellucci pointed out, the inferential model does not mean that there is no structure to signs: “while Leibniz’s simple concepts are classified in respect to their matter, Peirce’s simple concepts are to be classified according to their form (MS 499: 17). In respect to form, simple ideas might not have an internal structure, but they must have an ‘external’ one” (Bellucci 2013: 348).[4] This principle is exemplified by Peirce’s logic of relatives, where there is no deep distinction between nouns and verbs, nor between primitive and composite concepts (a distinction that does not logically hold, as Peirce, before Eco, demonstrated) all of which are equally rhemi (or terms), signs unsaturated that can bound (be saturated) with other signs. All signs are rhemi with an external structure, hence all have a valency, just like chemical compounds:

And the result of Peirce’s inquiry is that there are only three kinds of primitive ideas, three kinds of primitive relations, that is, three kind of valency. Every primitive concept is a rhema, a predicate with a certain number of unsaturated bonds; there are only three kinds of rhemata: monadic, dyadic and triadic (CP 1.290–92, 3.421, 3.469, 5.469). Concepts, even simple concepts, differ not as their content but according to their form; such form is a form of relation (CP 4.5) by means of which any concept can be combined with others. The form of relation is not the value of the concept (its content) but its valency (its form). (Bellucci 2013: 348)

Plus, if signs have an external but not internal structure, then semantics must necessarily be a semantics based on interpretants (the meaning of a sign is another sign). This implied for Peirce an extended conception of propositions, as Stjernfelt (2014) has shown. The structure of a proposition is Subject + Predicate, that is two signs: rhema (index) + rhema (icon). The rhemi need not be linguistic, but can be multimodal, the prototypical example being a portrait with the legend indicating the subject represented. Hence, from a semiotic point of view a facial sign can be an index, as when we infer from a scar that the bearer of the scar is a reckless person, or that he cut himself with a knife; or it can be an icon, as when we infer that something is scary from the appearance of the faces of those who are looking at that thing. Finally, these inferences can be more or less standardized (more or less general) in a given culture, thus functioning as narrative tools (high standardization) or conversational tools (low standardization). According to interpretive semantics:

If someone starts talking and tells me /he ran/ it is not at all true that I, based on my linguistic competence, merely identify a portion of content represented by the articulation of some figures such as “action + physical + fast + with legs, etc.” [Instead] I dispose myself, by singling out a portion of content structured as a block of contextual instructions, to a series of expectations. For example: “he ran away in fright,” “he ran up to me,” “he ran against his nearest rival” […] (Eco 1984: 35, my translation)

We could paraphrase Eco and say that in a smile we can recognize a sign of happiness, satisfaction, surrender, and even resignation depending on the context, and respond accordingly. This does not mean that good and bad interpretations cannot be distinguished. It is possible that a person who always smiles is a happy person, but if someone smiles during a funeral, I should not conclude that he or she is happy, even though I can be wrong in both cases. A smile can mean different things, but I cannot smile at everything. Especially in the case of faces as narrative tools, I shouldn’t produce a happy or smiley face when I tell the story of Carlo’s encounter with a bear. There are limits of interpretations based on the external structures of signs.

6 Conclusions

One modest result I reached is that physiognomic theories that have been shown to be false embody the equational model of sign, while other physiognomic judgments, more and less reasonable, that are made at the level of common communication embody the inferential model. We may further ask whether the difference between the two models is not at least partly constitutive of the failure of classical physiognomic theories. As seen, the equation model dictates: (i) that the meaning of a sign is something other than a sign (a mental representation, an emotion, an idea, etc.); (ii) that the same sign “essentially” always has the same meaning; (iii) that the number of meanings is finite.

If the mentioned ecological and situated theories were right, then the equational model would directly have to do with the failure of physiognomic theories. In short, it would be possible that even if we tried all possible correlations between external signs and mental states we would never find a fixed code, because the meaning of signs, whether natural or cultural and everything in between, couldn’t be a mental representation. On the other hand, and from the point of view of semiotics, if there were a finite number of special mental representations for personality traits, emotions or other mental states these would not be able to account for the meaning of facial expressions, in particular they would not be able to account for the fake faces we make, for faces as narrative tools or even for faces as conversational tools, since the meaning of the latter is strictly determined by the context (Kuleshov effect).

But this does not mean that a weaker science of the face is impossible. As said, although faces do not have an internal structure that determines a fixed meaning invariable in all contexts and cultures, they do have an external structure that gives the meaning of facial signs and justifies the use of certain physiognomic judgments, and that can be studied by a semiotics based on the inferential model of the sign.

It remains an open question whether any theory that postulates mental representations implies the equational model of the sign.[5] If I look at the history of semiotics, indeed there seems to be a close connection between the equational model of sign and mentalism: in Aristotle as in Saussure, the mind is thought to reproduce the internal structure of signs. This is certainly also the case with many contemporary theories in cognitive science; so much so that the main problems in the philosophy of mental representations concern not only the format of representations, but how mental representations acquire their aboutness and what their determinate content is (cf. Egan 2020), and it is often unclear, comparing semiotic theory and philosophy of cognitive science, whether mental representations should be the meanings of external signs or vice versa (which is perfectly consistent with the equational model and the close interchangeability between the two sides of signifier and signified that the model postulates). On the other hand, in principle the inferential model is not necessarily bound to externalism. But what the semiotic discussion of physiognomic theories suggests is that semiotics, and cognitive semiotics in particular, should reflect on whether or not mental representations are necessary to account for the meaning of signs.

About the author

Michele Cerutti (b. 1992) is a PhD student at the University of Turn. His research interests include general semiotics, theory of truth, and semiotics of truth.

References

Alley, R. Thomas. 1983. Physiognomy and social perception. In R. Thomas Alley (ed.), Social and applied aspects of perceiving faces, 167–186. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.Search in Google Scholar

Allport, W. Gordon. 1937. Personality. A psychological interpretation. New York: Holt.Search in Google Scholar

Baggs, Edward & Anthony Chemero. 2021. Radical embodiment in two directions. Synthese 198. 2175–2190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-02020-9.Search in Google Scholar

Bellucci, Francesco. 2013. Peirce, Leibniz and the threshold of pragmatism. Semiotica 195. 331–355. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2013-0030.Search in Google Scholar

Bellucci, Francesco. 2017. Peirce’s speculative grammar. Logic as semiotics. New York & London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315211008Search in Google Scholar

Brandt, Anthony. 1980. Face reading. The persistence of physiognomy. Psychology Today 14(7). 90–96.Search in Google Scholar

Crippen, Matthew & Giovanni Rolla. 2022. Faces and situational agency. Topoi 41. 659–670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-022-09816-y.Search in Google Scholar

Crivelli, Carlos, Sergio Jarillo & Alan J. Fridlund. 2016. A multidisciplinary approach to research in small-scale societies: Studying emotions and facial expression in the field. Frontiers in Psychology 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01073.Search in Google Scholar

Darwin, Charles. 1972. The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London: D. Appleton.Search in Google Scholar

Di Paolo, Ezequiel, Anthony Chemero, Manuel Heras-Escribano & Marek McGann (eds.). 2021 Enaction and ecological psychology. Convergences and complementarities. Lausanne: Frontiers Media.10.3389/978-2-88966-431-3Search in Google Scholar

Dumouchel, Paul. 2022. Making faces. Topoi 41. 631–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-022-09799-w.Search in Google Scholar

Eco, Umberto. 1979a [1979]. Lector in fabula. La cooperazione interpretativa nei testi narrativi. Milan: Bompiani.Search in Google Scholar

Eco, Umberto. 1979b. Proposals for a history of semiotics. In Tasso Borbé (ed.), Semiotics unfolding. Proceedings of the second congress of the International Association of Semiotics Studies, 75–89. Berlin: De Gruyter.10.1515/9783110869897-012Search in Google Scholar

Eco, Umberto. 1984. Semiotica e filosofia del linguaggio. Turin: Einaudi.Search in Google Scholar

Egan, Frances. 2020. A deflationary account of mental representation. In Joulia Smortchkova, Krzysztof Dołęga & Tobias Schlicht (eds.), What are mental representations? 26–53. New York: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780190686673.003.0002Search in Google Scholar

Ekman, Paul & Harriet Oster. 1979. Facial expressions of emotion. Annual Review of Psychology 30. 527–554. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.30.020179.002523.Search in Google Scholar

Froese, Tom & Shaun Gallagher. 2012. Getting interaction theory (IT) together: Integrating developmental, phenomenological, enactive, and dynamical approaches to social interaction. Interaction Studies 13(3). 436–468. https://doi.org/10.1075/is.13.3.06fro.Search in Google Scholar

Gallagher, Shaun. 2001. The practice of mind: Theory, simulation, or interaction? Journal of Consciousness Studies 5(7). 83–108.Search in Google Scholar

Gallagher, Shaun. 2020. Action and interaction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198846345.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Gardner, Howard. 1985. The mind’s new science: A history of the cognitive revolution. New York: Basic Books.Search in Google Scholar

Gibson, J. James. 1979. The ecological approach to visual perception. New York: Psychology Press.Search in Google Scholar

Gray, T. Richard. 2004. About face: German physiognomic thought from Lavater to Auschwitz. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Heaven, Douglas. 2020. Why faces don’t always tell the truth about feelings. Nature 578(7796). 502–504. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00507-5.Search in Google Scholar

Hurley, Susan. 1998. Consciousness in action. London: Harvard University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Konderak, Piotr. 2018. Mind, cognition, semiosis: Ways to cognitive semiotics. Lublin, Poland: Maria Curie-Sklodowska University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Leone, Massimo. 2021. Preface to the special edition “artificial faces.” Lexia 37–38. 9–28.Search in Google Scholar

Levin, Daniel T. & Mahzarin R. Banaji. 2006. Distortions in the perceived lightness of faces: The role of race categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology 135(4). 501–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.135.4.501.Search in Google Scholar

Manetti, Giovanni. 1987. Le teorie del segno nell’antichità classica. Milan: Bompiani.Search in Google Scholar

Manetti, Giovanni. 2010. The inferential and equational models from ancient times to the postmodern. Semiotica 178(1/4). 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.2010.011.Search in Google Scholar

O’Regan, Kevin J & Alva Noë. 2001. A sensorimotor account of vision and visual consciousness. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 24. 939–1031. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x01000115.Search in Google Scholar

Paolucci, Claudio & Fausto Caruana. 2019. A semiotic ethology of the “superiority laughter”: A pragmatist and evolutionary hypothesis. Reti, Saperi, Linguaggi, Italian Journal of Cognitive Sciences 2. 243–259.Search in Google Scholar

Paolucci, Claudio & Fausto Caruana. 2020. Riso e Logos. Il riso semiotico come protolinguaggio, tra emozioni e socialità. Rivista Italiana di Filosofia del Linguaggio 66–77. https://doi.org/10.4396/SFL2019I8.Search in Google Scholar

Paolucci, Claudio. 2021. Cognitive semiotics. Integrating signs, minds, meaning and cognition. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-030-42986-7Search in Google Scholar

Thomas Parr, Giovanni Pezzulo & Karl J. Friston (eds.). 2022. Active inference. The free energy principle in mind, brain and behavior. Cambridge & London: MIT Press.10.7551/mitpress/12441.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Piccinini, Gualtiero. 2020. Neurocognitive mechanisms. Explaining biological cognition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198866282.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Pudovkin, Vsevolod. 1926 [1968]. Film technique. In Ivor Montagu (ed.), Film technique and film acting, 19–220. London: Vision Press.Search in Google Scholar

Schlicht, Tobias. 2023. The philosophy of social cognition. Bochum: Palgrave McMillan.10.1007/978-3-031-14491-2Search in Google Scholar

Sterelny, Kim. 1986. The imagery debate. Philosophy of Science 53(4). 560–583. https://doi.org/10.1086/289340.Search in Google Scholar

Stjernfelt, Frederik. 2014. Natural propositions. The actuality of Peirce’s doctrine of dicisigns. Boston: Docent Press.10.1007/s11229-014-0406-5Search in Google Scholar

Stjernfelt, Frederik. 2016. Dicisigns and habits: Implicit propositions and habit-taking in Peirce’s pragmatism. In Donna E. West & Myrdene Anderson (eds.), Consensus on Peirce’s concept of habit, 241–262. Cham: Springer.10.1007/978-3-319-45920-2_14Search in Google Scholar

Violi, Patrizia. 1997. Significato ed esperienza. Milan: Bompiani.Search in Google Scholar

Zebrowitz, Leslie A., P. Matthew Bronstad & Joan M. Montepare. 2010. An ecological theory of face perception. In Reginald B. Adams, Ambady Nalini, Ken Nakayama & Shinsuke Shimono (eds.), The science of social vision, 3–30. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195333176.003.0002Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction to “The visage as text”

- Physiognomic theories between equation and inference

- Paolo Marzolo and Cesare Lombroso: a semiotic-medical inheritance between word, sounds, and face

- Lombroso’s criminal face across physiognomy and semeiotics

- Embodying genre: from Galton’s generic faces to Peirce’s embodied ideas

- Reading and writing in n-dimensional face space

- Face in the mirror, what do you see? Catoptric autoexperimentation and the physiognomic gaze

- Concealment of the face and new physiognomies

- Eyes on Chinese female models’ faces: stereotypes, aesthetics, self-Orientalism, and the moral discourse of the CPC

- The visage and the mask: semiotic considerations around representations of visages in Japanese Nō

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction to “The visage as text”

- Physiognomic theories between equation and inference

- Paolo Marzolo and Cesare Lombroso: a semiotic-medical inheritance between word, sounds, and face

- Lombroso’s criminal face across physiognomy and semeiotics

- Embodying genre: from Galton’s generic faces to Peirce’s embodied ideas

- Reading and writing in n-dimensional face space

- Face in the mirror, what do you see? Catoptric autoexperimentation and the physiognomic gaze

- Concealment of the face and new physiognomies

- Eyes on Chinese female models’ faces: stereotypes, aesthetics, self-Orientalism, and the moral discourse of the CPC

- The visage and the mask: semiotic considerations around representations of visages in Japanese Nō