Abstract

The effectiveness of Curcuma longa extract in the control of low-carbon steel corrosion caused by sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) in Baar’s medium was investigated. The SRB taken for the study was Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Specimens in contact with the medium containing SRB exhibited a corrosion rate more than 10 times that of the specimens in contact with the medium without SRB. The weight loss studies showed that the addition of 50 ppm C. longa extracts to the medium containing SRB resulted in an average inhibition efficiency of 91.2% for a four week immersion period. The inhibitor extract altered the reaction rates of both cathodic and anodic reactions which were confirmed from the potentiodynamic polarization (PP) studies. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) studies showed a reduction in the number of sessile bacteria upon inhibitor addition which was confirmed by the microscopy. Severe pitting was observed in the morphological analysis of the specimen in the absence of inhibitor treatment. Apart from adsorption onto the specimen surface to minimize the biocorrosion, the inhibitor extract also served as an anti-film forming and antibacterial agent.

1 Introduction

The microbe-influenced damage to the metal or concrete structures is a big issue that affects all sectors from process industries to municipal water distribution lines and monuments. Microbes such as bacteria, fungi, and algae cause corrosion of metals either directly or indirectly (A. Sharma et al. 2020). Such damages to materials influenced by microbes are called microbial influenced corrosion (MIC) or biocorrosion or microbiological corrosion (Bhola et al. 2014). The incidence of MIC is widespread in various process plants, power stations, refineries, and water distribution systems. A general survey on corrosion economics states that out of the failures that arise due to corrosion of the pipelines, 50% is contributed by MIC. The corrosion cost contributed by MIC is reported to range between 30 and 78% (Singh 2020). Thus, the severity and the extent of damage caused by MIC cannot be ignored.

The MIC causing microbes damage the material either by consuming the electrons from the metal for their metabolic activity or by producing corrosive products out of their metabolic activity which damages the metal. The former is grouped as type-I MIC and the latter is classified as type-II MIC.

Among the microorganisms that contribute to corrosion, sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) including the genus Desulfovibrio desulfuricans are regarded as the more damage-causing group considering the extent of damages caused by them (Bhola et al. 2014). Various theories explain the mechanism of SRB-influenced corrosion in iron. The well-known cathodic depolarization (CDP) theory satisfactorily demonstrates the corrosion caused by hydrogenase-containing SRB. The CDP explains the bacterial utilization of the hydrogen produced at the cathode and the electron from the metal surface for sulfate reduction which results in corrosive metabolites production. Thus the hydrogenase enzyme plays a major role in hydrogen scavenging activity in certain hydrogenase-containing bacteria and causes corrosion. Production of corrosive and electrically active FeS by SRB leads to the formation of concentration cells and promotes corrosion.

Low-carbon steel is more extensively used in all the process industries at various levels and it is an important material in ship construction industries (Eyres 2006). It also finds application in oil transportation pipelines (Tang 2020). However, low-carbon steel is more prone to corrosion both by corrosive chemicals and microbes (A. Sharma et al. 2020). Various corrosion control measures have been reported for the MIC control in low-carbon steel. A few of them are cathodic protection, galvanization and the use of genetically engineered strains (Darbi et al. 2002). The use of cathodic protection and, galvanization did not yield fruitful results in the control of SRB-influenced MIC. The use of genetically modified strains for MIC control was successful at the lab scale but did not give a good outcome in the field study. It was not due to the highly sensitive nature of the bio-engineered strains to the changes in the environment. Not only the bio-engineered strains, but the entire microbial system is more sensitive to the changes in the local environmental conditions such as pH, light, and temperature. Change in any one of the environmental parameters may change the behavior of the microbial strains thus affecting their corrosion inhibition characteristics. It was found that the inhibition efficiency of certain bio-engineered bacterial strains decreased significantly with the change in temperature (Jayaraman et al. 1997). The use of corrosion protective epoxy coatings has also been evaluated for fighting MIC in low-carbon steel (Tang 2020). Though the application of coatings was found satisfactory, any discontinuity in the coating was found to increase the MIC corrosion (Victoria et al. 2021). The application of biocides or corrosion inhibitors is widely practiced in industries to control the MIC. The use of inhibitors is preferred over any other techniques of corrosion control because the addition of a small quantity of inhibitors can provide better corrosion control. Synthetic chemicals such as heterocyclic compounds, glutaraldehyde, and formaldehyde are among the commonly used biocides for MIC control. Plant-based inhibitors have been extensively studied for various metals in the control of SRB corrosion (Chaithra et al. 2018; Darbi et al. 2002; Swaroop et al. 2016). Extracts from Brassica nigra, Allium cepa, Piper guineense were studied as corrosion inhibitors for SRB-influenced corrosion of metals. These studies consisted of presence or absence studies with various SRB strains without including the metal in the system. No systematic studies were made for SRB-influenced MIC. There are very few works that report systematic MIC studies with plant-based corrosion inhibitors. Extract of neem was found to give satisfactory corrosion inhibition efficiency against the corrosion caused by SRB in pipeline steel. The use of 2 vol% extract of Ocimum sanctum has been found to offer 74% inhibition efficiency against SRB-influenced corrosion in mild steel (Chaithra et al. 2018).

With limited plant-based inhibitors being explored to control SRB-influenced MIC in metals, this work discusses in detail the efficacy of the Curcuma longa (turmeric) extract for combating the SRB-influenced corrosion in low-carbon steel. The C. longa extract was chosen for this study taking into account its antibacterial and anti-film forming properties (Sarkar and Hussai 2016). Studies have shown that C. longa has better antibacterial properties than the extracts of ginger, garlic, and mustard which have been already tested for their antimicrobial activity against SRB (Guiamet and Saravia 2005; Rakshit and Ramalingam 2010). According to studies on active ingredients in C. longa, curcumin is well-known for its metal-binding properties which were found to be useful in preventing corrosion (Florez-Frias et al. 2021). Apart from the medicinal properties, its inexpensive nature, widespread availability, and environment-friendly characteristics were some of the reasons behind the selection of C. longa as the corrosion inhibitor in the present study.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Coupon preparation and nutrient broth

Low-carbon steel (0.09% carbon) sheet of 1 mm thickness was used as the specimen for experiments. Low-carbon steel coupons of 1 cm × 1 cm dimension were cut from the metal sheet. For the weight loss studies, well-polished coupons were tied with a polymeric thread and hung into the corrosive medium with and without the SRB culture. One side and the edges of the coupon were sealed completely using adhesive Teflon tape to protect the surfaces from the corrosive medium. For the electrochemical experiments, copper contact was fixed to the unexposed surface of the low-carbon steel coupon. Care was taken to ensure that the exposed surface area for the metal coupons in both weight loss and electrochemical studies is 1 ± 0.1 cm2.

Turmeric tubers were washed, air-dried, and powdered. The collected powder was soaked in ethyl alcohol for one day. The solvent was removed from the filtrate using vacuum evaporation. The turmeric extract thus obtained was used as the inhibitor for the experiments. For all the experiments with inhibitors, 50 ppm of the turmeric extract was used. The Baar’s medium containing ammonium chloride, calcium and magnesium sulfate, dihydrogen phosphate, and ferrous ammonium phosphate was used for the studies. The composition of the nutrient medium is mentioned in detail elsewhere (A. Sharma et al. 2020). The medium thus prepared was purged with nitrogen to eliminate the dissolved oxygen and to create an anaerobic environment. The pH of the medium after the autoclave process was maintained at seven.

2.2 Gravimetric method

The gravimetric experiments were performed for four weeks by submerging the low-carbon steel coupons in test tubes containing diverse media namely – nutrient media without SRB and inhibitor as AUI, nutrient media with the inhibitor as AI, nutrient media with D. desulfuricans as BUI, and nutrient media consisting of D. desulfuricans and inhibitor as BI. The concentration of the inhibitor used was 50 ppm. Pre-weighed low-carbon steel coupons were hung in the test tubes containing different nutrient mediums and sealed properly and positioned in the incubator at 37 ± 2 °C. Every week, four low-carbon steel coupons were taken out from each media, washed to detach the biofilm and products of corrosion from the coupons. The cleaned coupons were weighed to calculate the corrosion rate (CR) using Eq. (1) (Swaroop et al. 2016). The weight loss of the cleaned coupons was measured and used to estimate the CR using Eq. (1) (Swaroop et al. 2016). The weight loss used in the study for each case is the average weight loss of four coupons. The CR in mmpy was obtained from the weight loss data (in mg) using Eq. (1) (Swaroop et al. 2016).

Eq. (1) uses the area of the specimen (A) in cm2, the metal density (ρ) in g cm−3, and the exposure duration (t) in ‘h’. The extent of corrosion inhibition (IE) offered by the inhibitor was calculated using the drop in the weight observed for the coupons in uninhibited (WWOI) and inhibited (WWI) medium using Eq. (2) (Swaroop et al. 2016).

2.3 Polarization and impedance spectroscopy

The electrochemical characterization studies were conducted for the low-carbon steel coupons in BUI and BI broths. Every week four coupons were taken out for the analysis. Before potentiodynamic polarization (PP) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) runs, coupons were maintained at OCP for 30 min. The PP studies were made by scanning the electrode at 1 mV for every sec. The Tafel parameters were calculated from the PP plots by the Tafel extrapolation route using the CH6091E electrochemical analyzer software. The CR was calculated from the obtained Icorr values using the method described elsewhere (Swaroop et al. 2016). The EIS runs were made by studying the response of the system between 105 Hz and 10−1 Hz frequency with 10 mV rms amplitude sine wave. The results of the impedance runs were analyzed with the help of Zsimpwin software to find the apt electrical equivalent circuit (EEC) consisting of electrical elements. The stability and validity of the results from EIS studies were tested using Kramers Kronig Transformation (KKT). In the case of electrochemical techniques, the test tubes containing prepared coupons immersed in different media were incubated at 37 ± 2 °C and the electrochemical analysis was conducted at the same temperature. For all the electrochemical techniques, 30 mL of the respective nutrient medium was used as the electrolyte.

2.4 Characterization

The dissolved sulfide concentration of the nutrient medium after inoculation with the D. desulfuricans was analyzed periodically to study the growth characteristics. Iodometric titration explained elsewhere in detail has been followed to estimate the dissolved sulfide content (Baird et al. 2017). The sulfide content of the nutrient medium after removing the immersed low-carbon steel coupons was also measured every week. The coupons which were submerged in different media for the four immersion periods were analyzed for their morphology using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Characterization of the films adhering to the coupon’s surface was performed using FTIR. The type of deposits on the surface of the coupons was investigated by X-ray diffraction studies.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Gravimetry

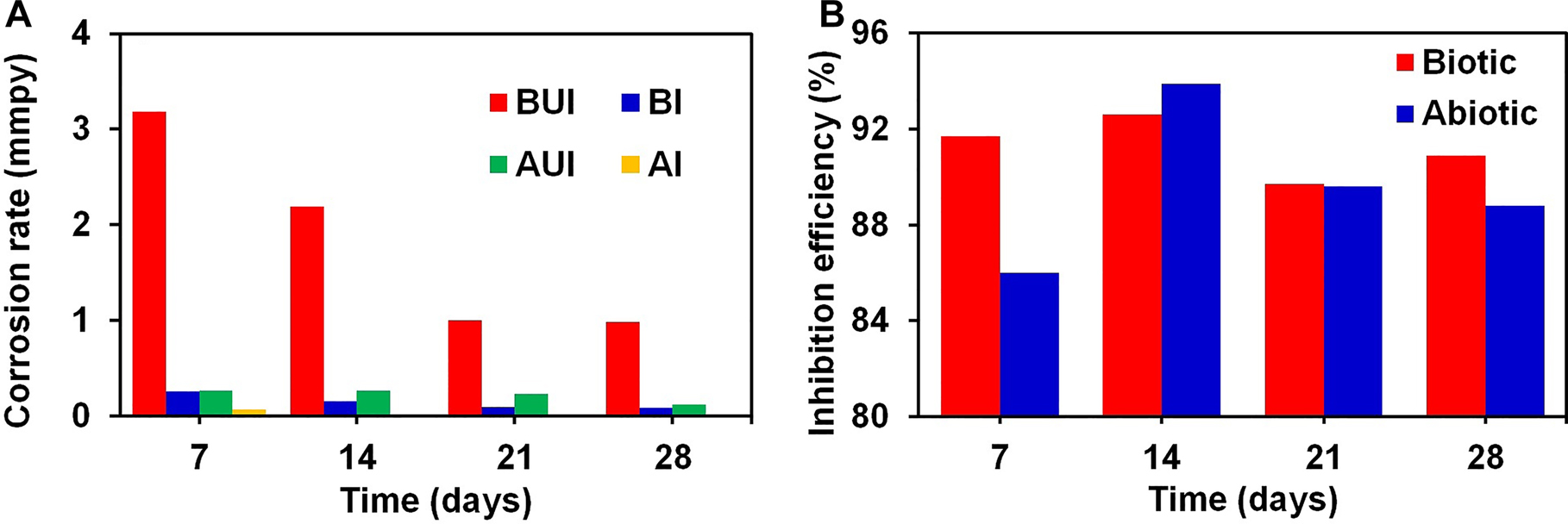

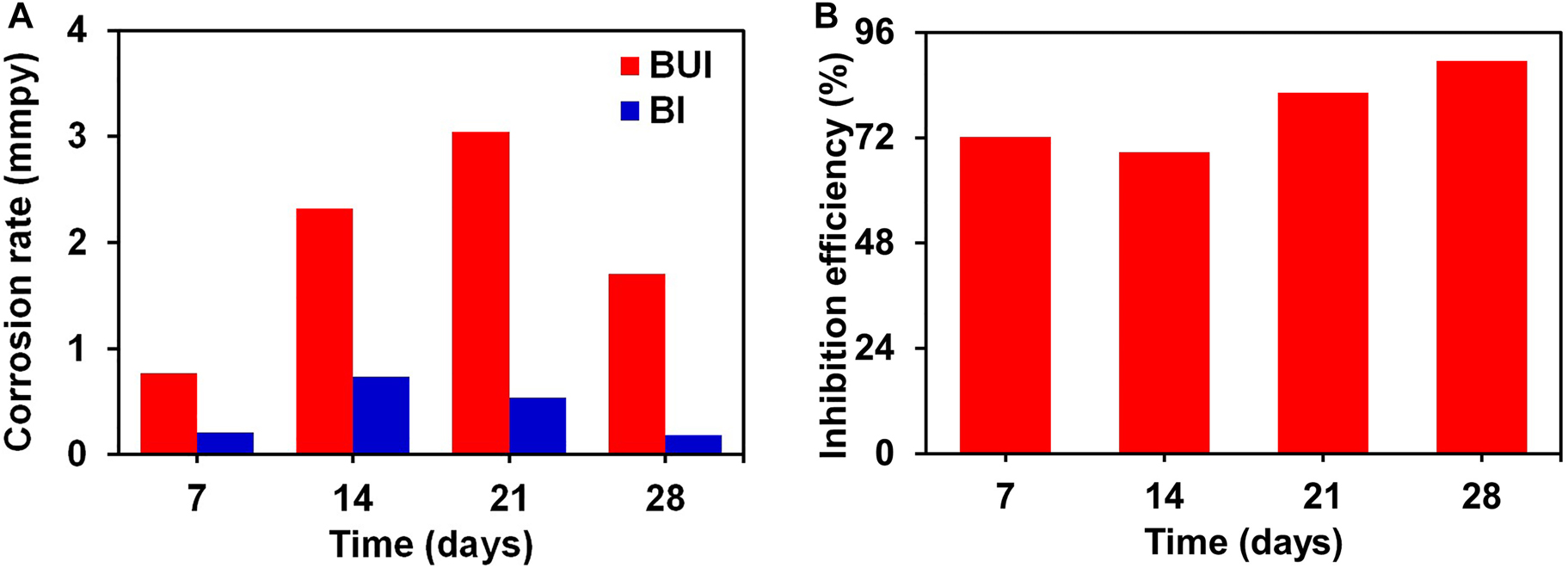

Figure 1A shows the effect of four immersion periods on CR for the low-carbon steel coupons in contact with various media. The CR of the low-carbon steel specimens in contact with the AUI broth (without SRB culture) for the first three weeks was about 0.27 mmpy and for the fourth week, it decreased to 0.12 mmpy. This could be due to the accumulation of corrosion products on the coupon surface which blocked the path for corrosive medium to reach the coupon surface and thereby decreased the CR. The CR of the coupons in contact with the BUI broth increased significantly to 3.18 mmpy for the first week due to the bacterial action. This dropped to 2.19 mmpy during the second week. For the third and fourth weeks, this decreased further to 1.0 mmpy. Such a continuously dropping CR with time could be due to the biofilm formation that poses a resistance to the corrosive medium from reaching the substrate.

Gravimetric study: effect of immersion time on (A) corrosion rate (CR) and (B) inhibition efficiency for low-carbon steel in biotic and abiotic medium.

The CR increased more than 10 times with the introduction of D. desulfuricans to the nutrient broth. Figure 1A also gives information on the CR of the low-carbon steel coupons exposed to the AI and BI broth with 50 ppm turmeric inhibitor. A significant drop in CR can be observed in both cases. The weight loss observed in the low-carbon steel coupons with inhibitor was approximately 10% of the weight loss values observed in the uninhibited case. This shows that the turmeric inhibitor is capable of protecting the low-carbon steel surface from both the chemical attack of the nutrient medium and also from the corrosive metabolic activities of the SRB. The inhibition efficiency (IE) for the turmeric extract was calculated from the weight loss data and is shown in Figure 1B. An average IE of 91.2% was observed for a four week immersion period against the corrosion caused by SRB. This shows that the turmeric extract can control the population and metabolic activity of the SRB present in the medium. Similarly, an average inhibition efficiency of 90% was observed for the abiotic coupons.

3.2 Sulfide analysis

Supplementary Figure S1 shows the dissolved sulfide concentration in the nutrient medium which has been inoculated with D. desulfuricans culture at various time intervals. The sulfide concentration increased with immersion period till 96 h and remained stable till 192 h. The sulfide concentration began to drop slightly after 192 h. The maximum sulfide concentration observed for the biotic medium without low-carbon steel coupons was 105 ppm.

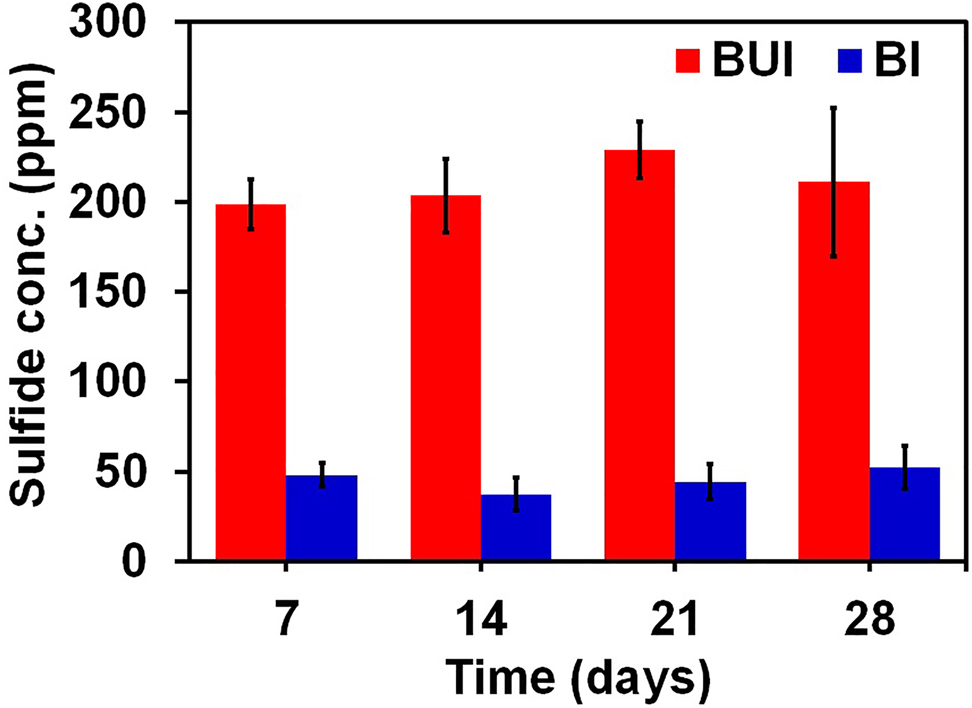

The BUI and BI broth in which the coupons were soaked for defined durations were analyzed for dissolved sulfide concentration after removing the low-carbon steel coupons. The results of the sulfide analyses are shown in Figure 2. The uninhibited nutrient medium with bacterial culture presented sulfide values greater than 198 ppm for all the immersion periods. The broth with turmeric extract showed an average dissolved sulfide concentration between 37.2 ppm and 52 ppm for all the immersion periods. This shows that the inhibitor extract controls the SRB growth and metabolic activities of the SRB effectively. The observed increase in the sulfide values for the nutrient broth with the metal coupon is due to the enhanced growth of the bacteria resulting in increased sulfide production.

Effect of immersion time on dissolved sulfide concentrations for low-carbon steel in BUI and BI medium.

3.3 FTIR analysis

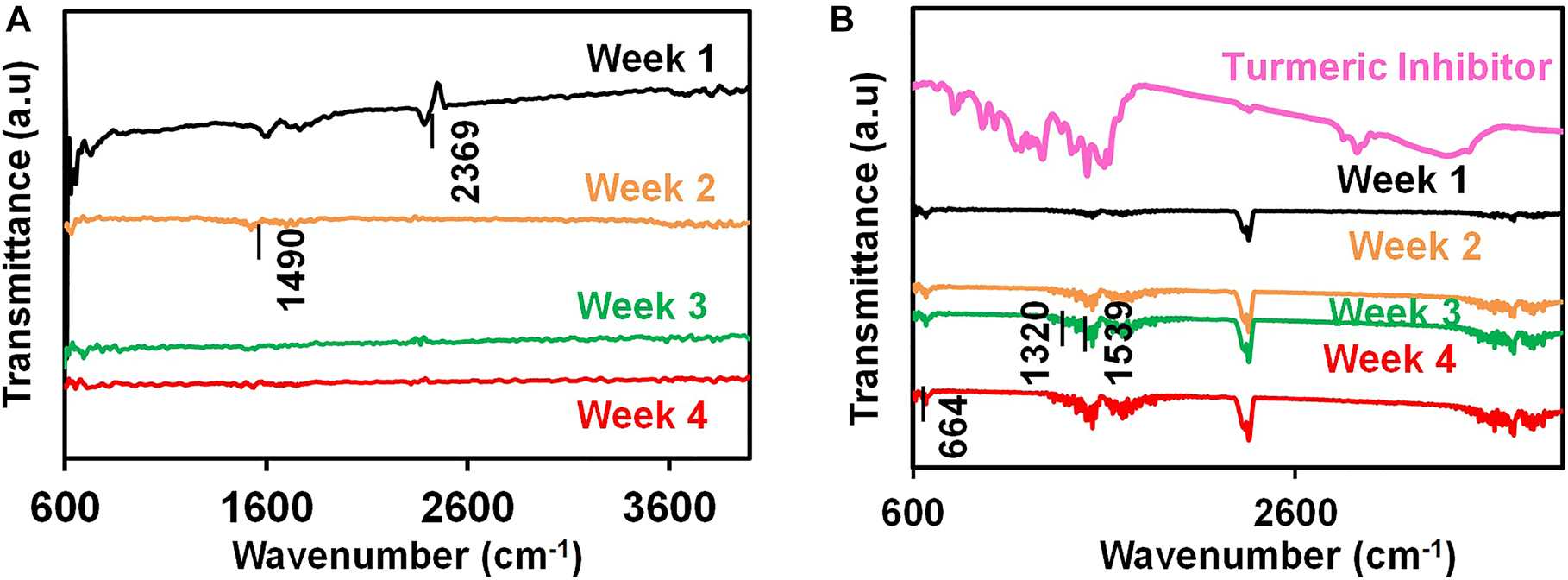

Figure 3A and B represent the FTIR spectra of the low-carbon steel coupons submerged in BUI and BI broth with external film layers. The low-carbon steel coupons exposed to the BUI broth showed few low-intensity peaks. Minor intensity peaks corresponding to the -OH group are present in the wavenumbers between 3500 cm−1and 3800 cm−1. This could be the contribution from the iron hydroxide which is one of the products of SRB-influenced corrosion of iron (Chaithra et al. 2018). The peak at 2360 cm−1 represents the CO2 from the environment (Stenclova et al. 2019). The peaks between 1490 cm−1 and 1570 cm−1 in the uninhibited specimen indicate the presence of amide-II groups contributed by proteins of the bacteria (Di Martino 2018). The peaks corresponding to the amide group present intensity changes due to the changing nature of the biofilm and bacterial population (Di Martino 2018). Peaks around 711 cm−1 are the contribution from weak C=O groups (Yuniarto et al. 2016). The specimen in contact with the BI broth showed the presence of various functional groups owing to the presence of turmeric extract coating on the surface. Peaks from 3500 cm−1 to 3800 cm−1 are caused by the –O–H stretching. The intensity of the peaks corresponding to the hydroxyl group is more, which could be the contribution from the adsorption of the polyphenolic compound curcumin (Yuniarto et al. 2016). The peaks referring to atmospheric carbon dioxide are also observed. The peaks from 1830 cm−1 to 1860 cm−1 and at 1680 cm−1 signify the occurrence of carbonyl compounds such as curcumin, the active compound in the turmeric (Malik and Mukherjee 2014). The coupon treated with the inhibitor also shows the presence of amide groups, the functional units of proteins such as turmerin, an antioxidant protein in turmeric (1539 cm−1) (Malik and Mukherjee 2014). There are peaks corresponding to turmerone at 1520 cm−1 in the turmeric extract and also in the coupons treated with turmeric extract (Priyanka and Khanam 2018). The peaks in the range between 1320 cm−1 and 1330 cm−1 in both turmeric inhibitor and the coupons treated with the inhibitor can be attributed to the presence of curcumin (Priyanka and Khanam 2018). Further, the peak at 664 cm−1 represents the bending of CH2 from carbohydrates (M. Sharma et al. 2020). The FTIR analysis of the inhibited coupon clearly shows the presence of adsorbed inhibitor molecules.

FTIR spectra for the low-carbon steel coupons immersed in (A) BUI broth (B) BI broth at four immersion periods.

3.4 Phase identification

X-ray diffraction spectra of the low-carbon steel coupons soaked in BUI and BI broth for four weeks are shown in Supplementary Figure S2A and B respectively. In Supplementary Figure S2A, the prominent peak at 44.9° corresponds to the (110) plane of metallic iron (JCPDS 01-087-0722). The peak at 30.1° in Supplementary Figure S2A is the contribution from FeS. The small intensity peaks at 36.7° and 40.2° correspond to the existence of pyrrhotite, an iron sulfide mineral with the general formula Fe1−xS with the value of ranging between 0 and 0.125. The formation of pyrrhotite has been reported in the SRB-influenced corrosion of carbon steel (El Hajj et al. 2013). The peaks at 65° and 83° correspond to iron (Shi et al. 2016).

The formation of iron sulfides can be explained using the following reaction steps using the CDP theory. The dissolution of iron occurs at the anodic sites releasing Fe2+ and electrons. Dissociation of water releases protons (H+) and OH− ions. The reaction between H+ and the electrons from metal dissolution produces H which is utilized by the SRB for sulfate reduction as shown in the reaction (3).

The reaction between dissolved Fe2+ and S2− result in iron sulfide formation (reaction (4)).

Due to the rapid formation kinetics, FeS forms in the early stages of SRB-influenced corrosion. The FeS formed further transform to form other forms of iron sulfide such as FeS2, pyrrhotite (Shi et al. 2016).

The coupons immersed in inhibited medium (Supplementary Figure S2B) show the presence of FeS and pyrrhotite which disappear after one week immersion. The coupons immersed for a longer duration show the peaks at 65° and 83° that corresponds to iron. The coupons in the uninhibited medium show the presence of iron sulfide to a greater extent when compared to the inhibited coupons. This indicates that the turmeric extract is helpful in the control of SRB-influenced corrosion.

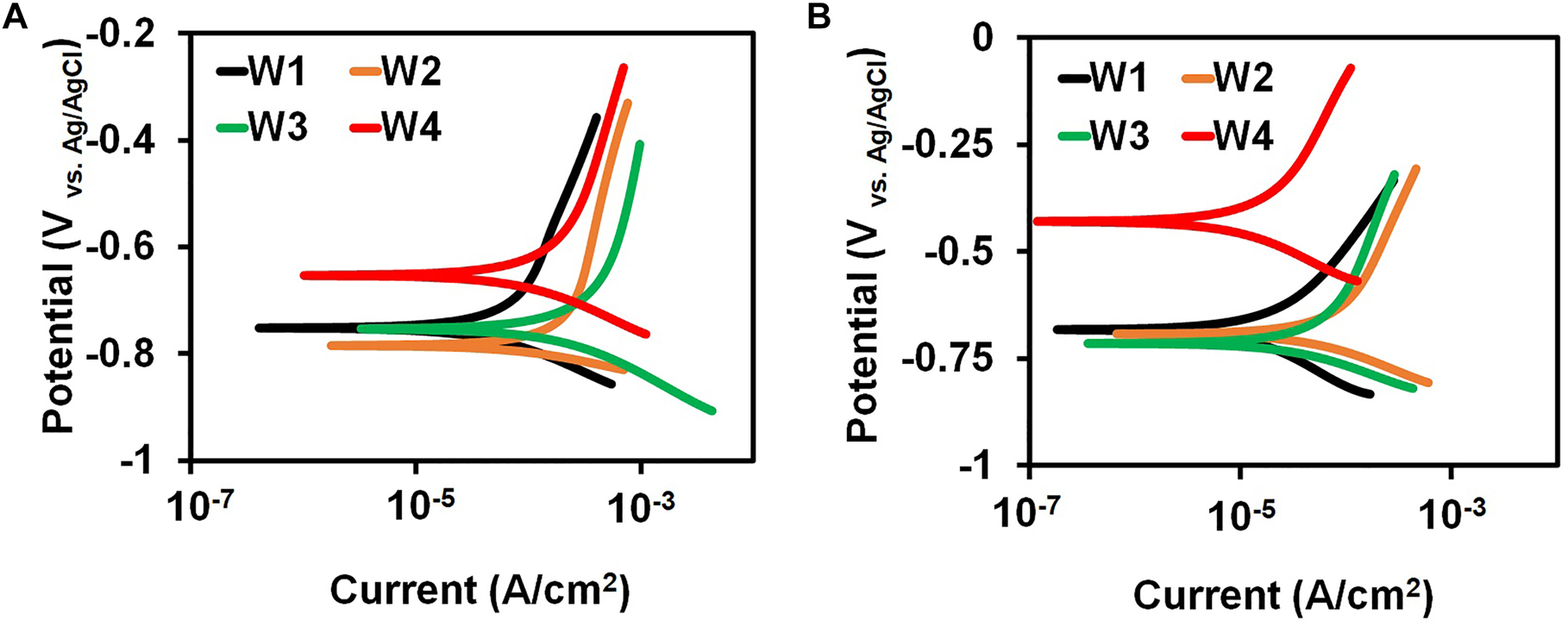

3.5 Polarization studies

Figure 4A and B displays the results of PP analysis for the low-carbon steel coupons in BUI and BI broth at four immersion periods. The branches corresponding to the negative and positive electrode regions in the polarization plot show no drastic changes upon inhibitor addition. This shows that the inhibitor addition to the biotic system did not alter the mechanism of hydrogen evolution reaction at the cathode and metal dissolution at the anode (Guo et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2019). The Tafel parameters for low-carbon steel BUI and BI media are presented in Table 1. The cathodic branches in both uninhibited and inhibited biotic specimens did not show well-defined Tafel region. Hence the Tafel parameters were calculated using the anodic Tafel region extrapolation as explained in the literature (Villamizar et al. 2008). The corrosion rate and the inhibition efficiency calculated from the PP study against the four immersion periods are shown in Figure 5A and B respectively.

Polarization plots for low-carbon steel coupons immersed in (A) BUI (B) BI media at four immersion periods.

Tafel parameters for low-carbon steel BUI and BI media.

| Parameters | Biotic uninhibited | Biotic inhibited | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 days | 14 days | 21 days | 28 days | 7 days | 14 days | 21 days | 28 days | |

| E corr (V vs. Ag/AgCl) | −0.75 | −0.79 | −0.78 | −0.66 | −0.68 | −0.69 | −0.72 | −0.43 |

| I corr (µA cm−2) | 65.2 | 198 | 259 | 145 | 18.1 | 62 | 45.6 | 15.2 |

| β a (mV dec−1) | 460 | 312 | 500 | 486 | 265 | 378 | 405 | 360 |

Potentiodynamic polarization study: effect of immersion time on (A) corrosion rate (CR) and (B) inhibition efficiency for low-carbon steel in biotic and abiotic medium.

The cathodic and anodic current densities decrease with the inhibitor addition for the four immersion periods. Overall, the Ecorr values show a positive shift upon inhibitor addition which is due to the adsorbed inhibitor molecules that influence the anodic dissolution process (Aoun 2017; Szatmari et al. 2015). A positive shift in the Ecorr with inhibitor addition signifies the suppression of the anodic dissolution to a greater extent when compared to the cathodic process (Szatmari et al. 2015). Besides, to support this claim, the Tafel plots also present a decreased anodic current density with the inhibitor addition for all the immersion periods showing a decreased anodic dissolution (Yaro et al. 2015). The Ecorr values in both inhibited and uninhibited cases present a non-monotonic behavior with immersion time. The Ecorr value for the uninhibited coupon moves in a negative direction from −750 mV to −790 mV versus Ag/AgCl after two weeks of immersion due to the growth in the bacterial population and the increased corrosive activity (Guo et al. 2013). The Ecorr shows a significant shift in the positive direction for the fourth week which could be due to the corrosion products formed. An increase in the thickness of the biofilm with exposure time serves as a barrier for the corrosive environment which shifts the potential to the positive side (Guo et al. 2013). With the addition of the turmeric inhibitor, the Ecorr values show a positive shift for all the immersion periods. The magnitude of this positive shift ranges between 70 mV for the first week and 230 mV for the fourth week. The positive swing in the Ecorr is larger than 85 mV for the second week and the fourth week which might lead one to the conclusion that the inhibitor is anodic (Özkir et al. 2013). However, analysis of the cathodic and anodic branches shows that the turmeric extract influences both electrode processes because both the branches show significant current density changes with the inhibitor addition. Since the inhibitor influences both cathodic and anodic reactions it behaves as a mixed inhibitor. The inhibitor adsorbs on the surface of the metal and helps in controlling the corrosion. It also acts as an antimicrobial agent. A positive shift greater than 85 mV in the Ecorr values for the second and fourth week upon inhibitor addition can be considered as the effect of adsorption of the turmeric extract molecules, biofilm development, changes in the bacterial population, and the metabolic products formed (El Lateef et al. 2019; Moradi et al. 2013).

3.6 Impedance analysis

Supplementary Figure S3 presents the Bode plots from EIS studies for the specimen in BUI and BI broth at various times. The reliability of the data set was tested using the KKT. The Bode plot relating the changes in the impedance modulus with the frequency for the coupons in BUI medium and the BI medium containing turmeric extract is provided in Supplementary Figure S3-BUI-A and BI-A. The phase angle plots for the uninhibited and inhibited coupons are shown in Supplementary Figure S3-BUI-B and BI-B respectively. The impedance modulus in the high-frequency region from 105 to 101 Hz in both cases exhibits a capacitive behavior (Parthipan et al. 2017). In the middle frequency regime, a continuously increasing trend is observed for the impedance values which are characteristic of capacitive nature (Parthipan et al. 2017). The modulus of impedance value for the uninhibited case is the lowest for the first week of immersion indicating more corrosion. The development of a thicker biofilm causes the impedance values to increase continuously for the second and third-weeks. There is however a drop in the impedance value for the fourth week when compared to the third-week value due to the changing thickness and composition of the biofilm (Luo et al. 2018; Mazón et al. 2014; Swaroop et al. 2016). The impedance moduli increased for the coupons exposed to broth containing turmeric extract which shows that the turmeric extract has better anticorrosive properties. The low-frequency impedance values for the inhibited coupon increase continuously with immersion time. Such a trend of increased impedance with prolonged immersion in the inhibited medium has been reported elsewhere (Luo et al. 2018; Mazón et al. 2014). The enhanced impedance in the inhibited coupons with immersion duration is due to the increased stability of the protective layer due to the changes taking place in the medium such as pH and ionic composition (Lan et al. 2017; Luo et al. 2018; Mazón et al. 2014). The Bode-phase plot for the uninhibited coupons indicates an increasing trend in the low-frequency zone representative of capacitive behavior (Supplementary Figure S3 BUI-B) (Mazón et al. 2014). Maximum phase angle values in the frequency range between 10 and 0.1 Hz fall between 28° and 42° for the uninhibited coupons. The addition of the inhibitor was found to increase these values, because of the protective film formation at the surface (Pilić et al. 2019). The maximum phase angle ranges between 55° and 35° in the presence of the turmeric inhibitor (Supplementary Figure S3 BI-B). The phase angle indicates the presence of a finite-length Warburg element (WL). There is a phase shift towards the high-frequency side which is an indication of decreased corrosion rate (Bhola et al. 2014; Pilić et al. 2019). The high-frequency region of the Bode-phase plot presents an additional time constant in both inhibited and uninhibited coupons. Such a high-frequency time constant has been observed when SRB-influenced corrosion was studied in cupronickel. The high-frequency time constant represents the formation of biofilm or conductive layer (Bai et al. 2011; Sharma et al. 2018).

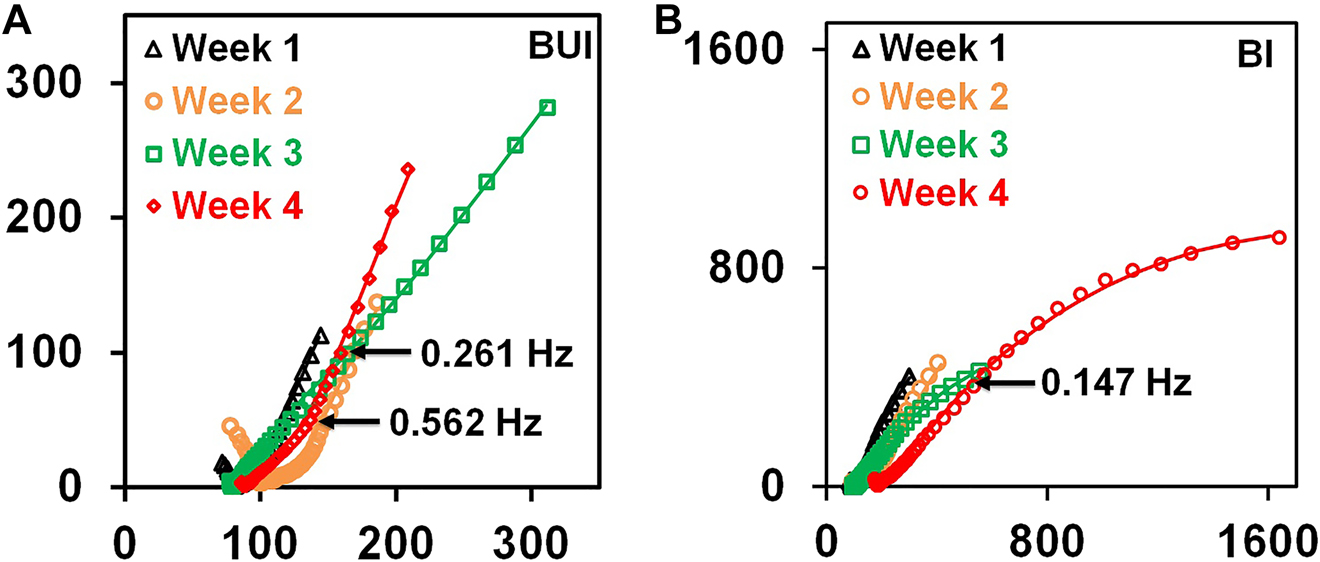

The Nyquist plots for the BUI and BI coupons are presented in Figure 6A and B respectively. The turmeric extract addition did not alter the form of the Nyquist plots. The high-frequency zone in both cases shows the occurrence of an incomplete capacitive curve. Such a feature at high-frequency regime has been reported by many groups (Pusparizkita et al. 2020; Song et al. 2017). Deposition of highly heterogeneous and conductive corrosion products on the specimen surface has been reported to be the cause of incomplete capacitive arc in the high-frequency region (Pusparizkita et al. 2020; Song et al. 2017). The Nyquist plot shows the presence of three-time constants. A finite-length Warburg element (WL) has been considered to account for the diffusion resistances. The finite-length Warburg impedance (ZWL) is expressed using the following Eq. (5)

Nyquist plot for low-carbon steel in uninhibited biotic coupon (BUI) (A) and inhibited biotic coupon (BI) (B). The experimental data is represented by dots and the continuous lines depict EEC fit.

In the above relation, the representation B stands for the ratio of diffusion path length (l) to the square root of diffusion coefficient (D). The admittance parameter Y0 is given by the expression Y0 = (3.29σ)−1 where the Warburg coefficient is given by σ.

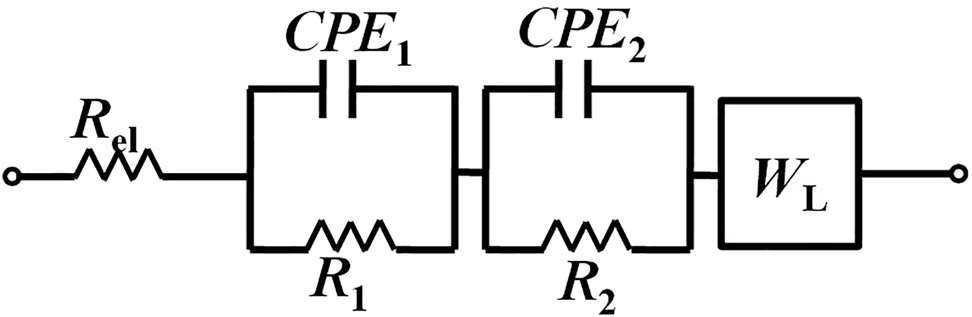

The impedance of the BUI coupons increases progressively with the immersion period till three weeks and decreases slightly for the fourth week as a result of the changes in the composition of the adherent layers on the coupon surface. An EEC with three-time constants consisting of two constant phase elements (CPE) to account for the external film and the double layer, three resistances to account for the effects of charge transfer resistance, the resistance associated with the external film and the solution resistance and a WL for the diffusion resistance is shown in Figure 7 was found to fit the experimental data well (Zhou et al. 2018). The Bode impedance modulus and phase angle plots show the existence of non-ideal capacitive behavior which led to the selection of CPE instead of an ideal capacitor. In the EEC, solution resistance is represented by the element Rel.

EEC used for fitting the EIS data for low-carbon steel showing the effect of inhibitor on MIC.

The best matching values of the EEC parameters can be obtained from Table 2. The total resistance values obtained from the sum of R1 and R2 values are lower for the uninhibited specimens in comparison with the inhibited specimens for all the immersion periods. This shows that the damage to the material by the SRB population has been brought down significantly with the turmeric inhibitor addition. The individual resistance values R1 and R2 in both cases did not show a systematic trend. This is because of the changes in the bacterial population which reside in the biofilm and the continuously changing composition and thickness of the biofilm. In addition to it, the conductivities of living and dead bacterial cells and the changes in the composition of the biofilm/corrosion products layer also influence the resistance of the biofilm layer (Swaroop et al. 2016). The capacitance values for C1 and C2 in both uninhibited and inhibited cases show a non-monotonic trend. The changes in the thickness of the biofilm and the bacterial population can influence the values of capacitance. A larger value of capacitance in comparison to the normal value is due to the effect of cytochromes that exist on the outer cell membrane (Swaroop et al. 2016). The inverse of admittance Y0, in WL component, gives information about the diffusion resistance (Y0−1). It can be seen that Y0−1 in the uninhibited biotic system is much higher when compared to the inhibited coupons. Similar trend has been reported in the study of biocorrosion by Escherichia coli where the application of corrosion preventive coating reduced the Y0−1 (Zhai et al. 2015). The formation of biofilm and the increased population of living sessile bacteria lead to increased Y0−1 in uninhibited system. The fluctuating values of Y0−1 in the uninhibited case with immersion weeks also show the continuously changing biofilm thickness and bacterial population at the surface of the specimen. The diffusion resistance in the uninhibited coupons arises out of the corrosion product deposits and the biofilm formation. Unlike uninhibited specimens, no significant variation is observed in the Y0−1 values of inhibited system.

EEC fitted values for the low-carbon steel in BUI and BI medium.

| Parameters | Biotic uninhibited | Biotic inhibited | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W1 | W2 | W3 | W4 | W1 | W2 | W3 | W4 | |

| R el (Ω cm2) | 11.5 | 9.5 | 66.1 | 118 | 23.2 | 15.6 | 61.5 | 192.4 |

| Y 1 × 106 (S sn cm−2) | 15,440 | 9430 | 7337 | 7448 | 0.015 | 0.2 | 0.39 | 339 |

| n | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| R 1 (Ω cm2) | 618 | 24,100 | 1294 | 2259 | 68.6 | 84.9 | 34.51 | 52.15 |

| C 1 (µF cm−2) | 17,777 | 96,590 | 7337 | 8783 | 0.010 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 26 |

| Y 2 × 106 (S sn cm−2) | 20,300 | 0.01696 | 2909 | 7379 | 5268 | 2525 | 1745 | 528.8 |

| n | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| R 2 (Ω cm2) | 255.4 | 161.9 | 309.6 | 192.3 | 35,190 | 68,700 | 2108 | 3207 |

| C 2 (µF cm−2) | 777,865 | 0.003 | 2726 | 11,492 | 8757 | 42,173 | 3587 | 687 |

| Y WL × 106 (S s0.5 cm−2) | 20.31 | 5533 | 125 | 33.7 | 7146 | 4194 | 8927 | 14.98 |

| B (s0.5) | 0.0014 | 0.11 | 0.002 | 0.0013 | 2 | 0.12 | 0.051 | 0.0013 |

| R T (Ω cm2) | 874 | 24,261 | 1603 | 2451 | 35,258 | 68,784 | 2142 | 3259 |

3.7 Morphological and compositional analysis

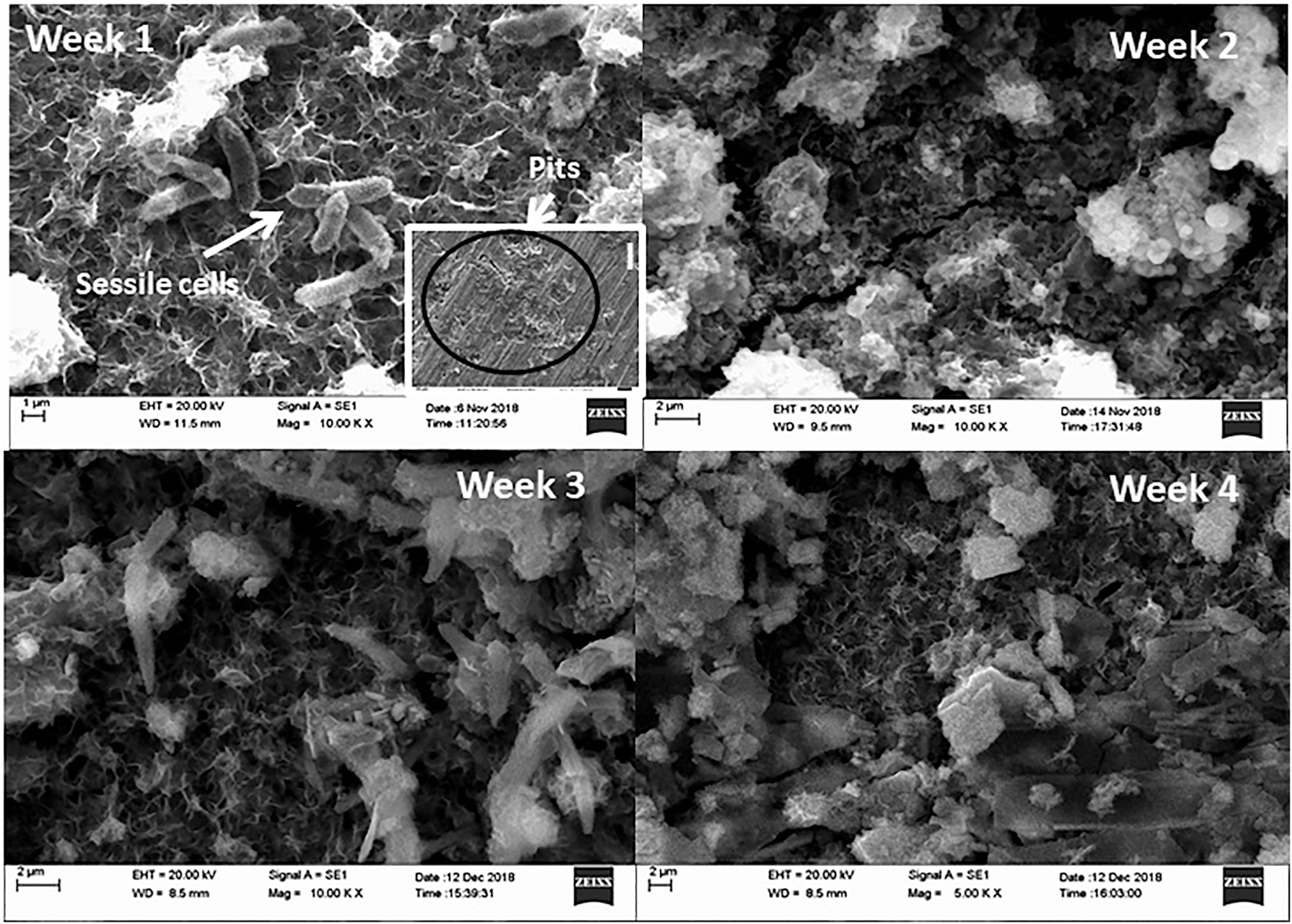

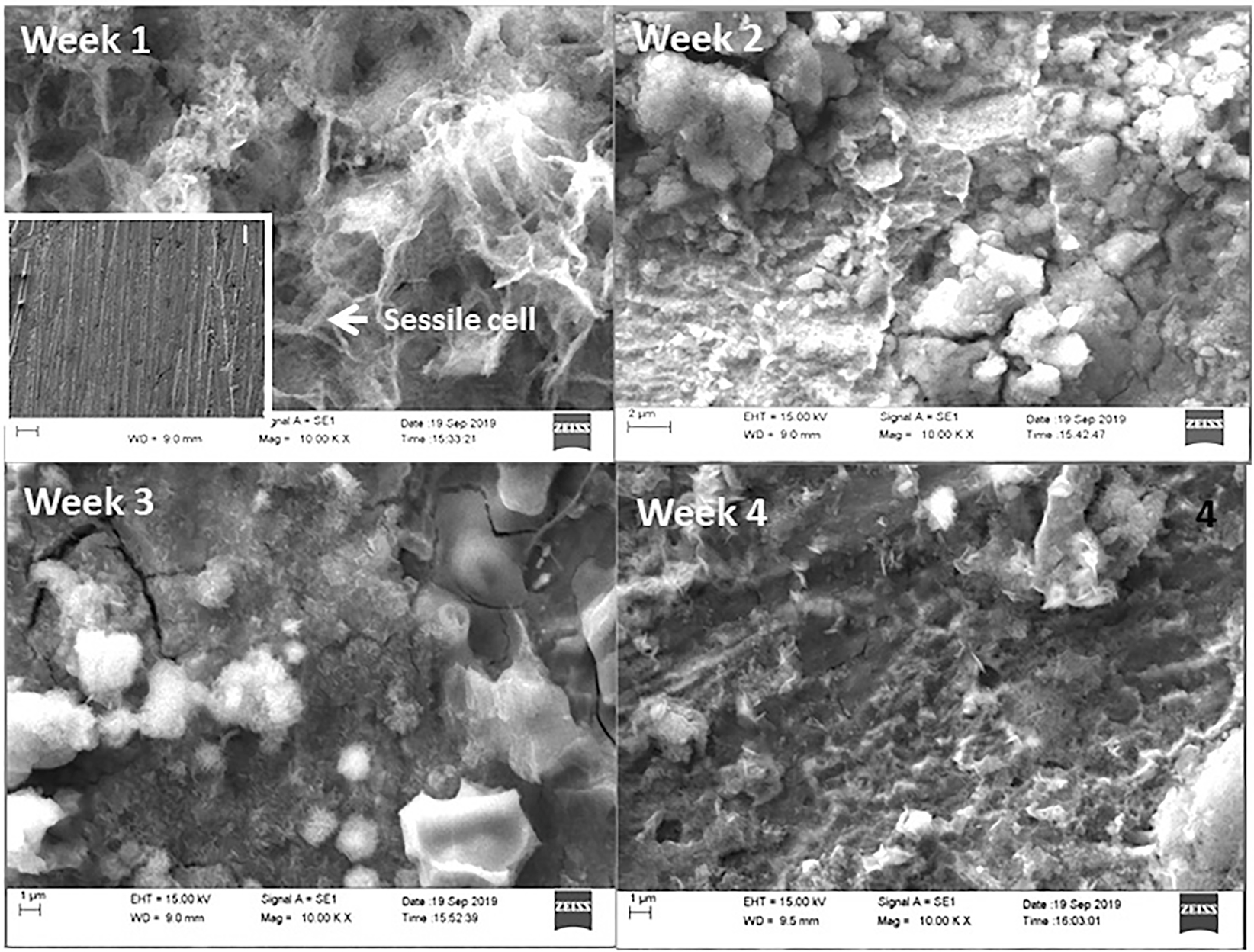

The low-carbon steel coupons immersed in various media for various exposure periods were analyzed for morphology by SEM. Figure 8 displays the results of the morphological studies of uninhibited low-carbon steel coupons. Sessile D. desulfuricans cells are visible on the first week specimen. Such sessile bacteria stay on the metal surface for a longer duration and cause more damage to the metal surface (Černoušek et al. 2020). The morphological analysis presents a continuous layer completely covering the metal surface and a highly discontinuous brighter, outer layer which is comparatively thicker than the inner layer. Such a two-layered structure is visible in all low-carbon steel specimens irrespective of the nature of the medium and duration of immersion. The outer, island-like growths show the presence of fibrous and globular structures of the biofilm formed by the bacterial activity. The inner continuous layer is formed from the corrosion products such as oxides of iron and iron sulfide (Černoušek et al. 2020). The low-carbon steel coupons in BUI media after two weeks of immersion show the growth of a thicker biofilm layer with some discontinuities. Biofilms on the uninhibited metal coupons for further immersion periods show an increase in the thickness and surface coverage. Figure 9 shows the morphology of the low-carbon steel coupons immersed in BI media. For all the immersion periods, the morphology of the deposits differs significantly when compared with the uninhibited coupons. The number of sessile bacteria is also very less in the presence of the turmeric extract. The inset I in Figure 8–week 1, shows the morphology of the low-carbon steel coupon immersed in BUI medium at the end of one week after removing the external film formed. Even at a low-resolution well-defined pit propagation is observed. The morphology of the inhibited low-carbon steel coupon at the end of one week after film removal shows a clear surface without any pit formation (Inset I in Figure 9-week 1). The markings of the polished surface are still visible in the inhibited coupon which shows that the turmeric inhibitor has protected the surface of the metal coupon to a greater extent.

SEM pictures of the low-carbon steel coupon in uninhibited biotic (BUI) media at four immersion periods with the biofilm. The inset -I in the week 1 image shows the SEM image of the week 1 coupon at 500× magnification after film removal.

SEM pictures of the low-carbon steel coupon in BI media at four immersion periods. The inset-I in the week 1 image shows the SEM image of the week 1 coupon at 500× magnification after film removal.

Table 3 shows the elemental composition of the low-carbon steel coupons immersed in different nutrient mediums for four immersion times. Table 3 also shows the elemental composition of the turmeric extract used for the study. The coupons immersed in the BUI broth show the presence of sulfur, which exists mostly as iron sulfide, an important product of SRB corrosion. The uninhibited and inhibited coupons in the biotic broth show the presence of phosphorus which is a contribution from the biofilm and nutrient media. An increased amount of C and O in the uninhibited low-carbon steel coupons show corrosion and biofilm formation. The XRD analysis of the coupons in the uninhibited media confirms the presence of iron oxide and iron sulfide. The low-carbon steel coupons in the inhibited media also show significant carbon and oxygen. However, the XRD analysis of the coupon does not show the presence of oxide. The turmeric extract shows the presence of a significant amount of C and O. This could be the reason for the presence of oxygen and carbon in significant quantities in the low-carbon steel coupons immersed in the inhibited medium. The existence of minerals such as phosphorus and calcium on the surface of the inhibited low-carbon steel coupons also comes from the turmeric extract (Ahamefula et al. 2014). The elemental analysis of turmeric extract was also found to contain traces of minerals iron, Ca, and Zn. Turmeric is a well-known source of minerals such as iron, Zn, and Ca (Ahamefula et al. 2014).

Elemental analyses of turmeric extract and the layer formed on the low-carbon steel coupons immersed in BUI and BI medium at four immersion periods.

| Elements | Biotic uninhibited (atomic%) | Biotic inhibited (atomic%) | Turmeric inhibitor (atomic%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 days | 14 days | 21 days | 28 days | 7 days | 14 days | 21 days | 28 days | ||

| C | 24.5 | 27.8 | 25.5 | 37.3 | 20.8 | 24.8 | 20.3 | 22.8 | 50.5 |

| O | 51.8 | 47.7 | 51.9 | 35.5 | 52.2 | 45.4 | 55.2 | 50.3 | 48.5 |

| Si | – | – | 0.13 | 0.29 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.36 | 0.88 | |

| Ca | 0.18 | 1.13 | 0.38 | 1.69 | 0.74 | – | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.04 |

| Fe | 19.9 | 16.1 | 17.7 | 14.3 | 24.1 | 28.6 | 22.7 | 24.2 | 0.05 |

| Mn | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| S | 3.11 | 5.39 | 3.35 | 10.73 | 0.43 | – | – | – | – |

| Al | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Mg | – | – | 0.6 | 0.32 | 0.23 | – | – | 0.82 | – |

| P | 0.23 | 1.89 | 0.18 | – | 0.75 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.73 | – |

| Cl | 0.15 | – | 0.14 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.4 |

| K | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.48 |

| Zn | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.03 |

3.8 Mechanism

The XRD analysis of the coupons in BUI broth shows the presence of iron sulfide and oxides. The reactions responsible for the formation of iron sulfide and iron hydroxide in the presence of D. desulfuricans are given by the well-known CDP theory. According to CDP, on a heterogeneous iron surface, the reactions (6) and (7) involve the dissociation of water and dissolution of iron at the anodic sites respectively (Daniels et al. 1987; King and Miller 1971).

The hydrogen generated from reaction (8) is used by the SRB as shown by reaction (9).

The S2− and Fe++ react further to give FeS. The Fe++ also reacts with the hydroxyl group to give hydroxide of iron.

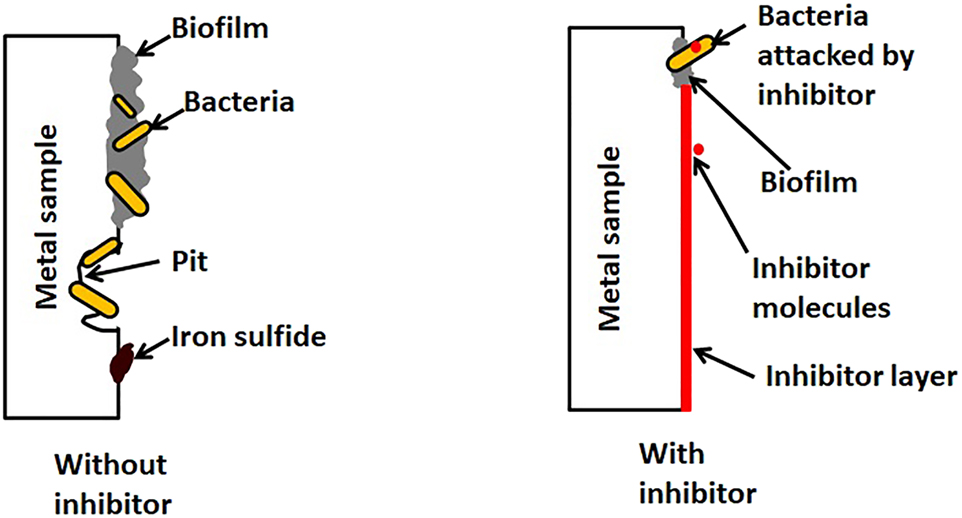

The Fe(OH)2 formed oxidizes when it comes to contact with atmospheric air to gives Fe2O3. Moreover, the FeS formed during the reaction is also electrically active and the FeS layer on the iron surface serves as an electrochemically active cathode while the neighboring iron region as anode forming a local concentration cell promoting corrosion (King and Miller 1971). With the addition of the inhibitor, the antibacterial components in the turmeric extract such as curcumin interfere with the metabolism of SRB. Figure 10 shows the schematic of the proposed hypothesis for the progress of low-carbon steel corrosion influenced by D. desulfuricans. The bacterial activity aids the formation of biofilm and corrosion products layer on the metal surface. The turmeric extract contains active antimicrobial molecules such as curcumin that increase the permeability of the bacterial cell wall (Tyagi et al. 2015). Some theories also support the mutation in the bacterial cells. These activities result in the death of the D. desulfuricans. Apart from these, the turmeric extract is a well-known anti-film forming agent which reduces biofilm formation (Hayat et al. 2018). A decrease in the dissolved sulfide in the inhibited biotic system and the decreased number of sessile bacteria in the presence of inhibitor supports the claim of the influence of the turmeric extract on the metabolic pathways of the bacteria. The SEM images of the specimen in BI medium show the absence of biofilm (Teow et al. 2016). The FTIR results also confirm the adsorption of functional compounds from turmeric on the low-carbon steel surface. The turmeric extract forms a coating on the metal surface and also interferes with the bacterial life cycle resulting in low-carbon steel surface protection.

Schematic of the proposed mechanism for steel showing the effect of inhibitor on MIC.

4 Conclusions

The effectiveness of turmeric extract as an inhibitor to control the damages caused by the D. desulfuricans in low-carbon steel has been studied. Use of 50 ppm turmeric extract in Baar’s media inoculated with the SRB was found to give more than 91.2% inhibition efficiency for four weeks immersion period. The SEM analysis shows the formation of two different layers on the surface of the low-carbon steel. The EIS studies also confirm the contribution of two layers. X-ray diffraction studies and FTIR analysis have affirmed the adsorption of the turmeric extract molecules on the low-carbon steel coupon.

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

Ahamefula, I., Onwuka, G.I., and Nwankwo, C. (2014). Nutritional composition of turmeric (Curcuma longa) and its antimicrobial properties. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 5: 1085–1089.Search in Google Scholar

Aoun, S.B. (2017). On the corrosion inhibition of carbon steel in 1 M HCl with a pyridinium-ionic liquid: chemical, thermodynamic, kinetic and electrochemical studies. RSC Adv. 7: 36688–36696, https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ra04084a.Search in Google Scholar

Bai, Y.J., Wang, Y.B., Cheng, Y., Deng, F., Zheng, Y.F., and Wei, S.C. (2011). Comparative study on the corrosion behavior of Ti–Nb and TMA alloys for dental application in various artificial solutions. Mat. Sci. Eng. 31: 702–711, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2010.12.010.Search in Google Scholar

Baird, R.B., Eaton, A.D., and Rice, E.W. (Eds.) (2017). Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. American Public Health Association, Washington.Search in Google Scholar

Bhola, S.M., Alabbas, F.M., Bhola, R., Spear, J.R., Mishra, B., Olson, D.L., and Kakpovbia, A.E. (2014). Neem extract as an inhibitor for biocorrosion influenced by sulfate reducing bacteria: a preliminary investigation. Eng. Fail. Anal. 36: 92–103, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2013.09.015.Search in Google Scholar

Černoušek, T., Shrestha, R., Kovářová, H., Špánek, R., Ševců, A., Sihelská, K., Kokinda, J., Stoulil, J., and Steinová, J. (2020). Microbially influenced corrosion of carbon steel in the presence of anaerobic sulphate-reducing bacteria. Corrosion Eng. Sci. Technol. 55: 127–137.10.1080/1478422X.2019.1700642Search in Google Scholar

Chaithra, S., Gupta, A., Manivannan, R., and Victoria, S.N. (2018). Studies on corrosion inhibitory action of Ocimum sanctum (Tulsi) leaves extract in low-carbon steel corrosion induced by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Indian J. Chem. Technol. 25: 441–450.Search in Google Scholar

Daniels, L., Belay, N., Rajagopal, B.S., and Weimer, P. (1987). Bacterial methanogenesis and growth from CO2 with elemental iron as the sole source of electrons. Science 237: 509–511, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.237.4814.509.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Darbi, M.M.A., Muntasser, Z.M., Tango, M., and Islam, M.R. (2002). Control of microbial corrosion using coatings and natural additives. Energy Sources 24: 1009–1018, https://doi.org/10.1080/00908310290086941.Search in Google Scholar

Di Martino, P. (2018). Extracellular polymeric substances a key element in understanding biofilm phenotype. AIMS Microbiol. 4: 274–288, https://doi.org/10.3934/microbiol.2018.2.274.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

El Hajj, H., Abdelouas, A., El Mendili, Y., Karakurt, G., Grambow, B., and Martin, C. (2013). Corrosion of carbon steel under sequential aerobic–anaerobic environmental conditions. Corrosion Sci. 76: 432–440, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2013.07.017.Search in Google Scholar

El Lateef, H.M.A., El Sayed, A.R., Mohran, H.S., Abdel, H., and Shilkamy, S. (2019). Corrosion inhibition and adsorption behavior of phytic acid on Pb and Pb–In alloy surfaces in acidic chloride solution. Int. J. Ind. Chem. 10: 31–47, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40090-019-0169-4.Search in Google Scholar

Eyres, D.J. (2006). Ship construction, 6th ed. Massachusetts: Butterworth-Heinemann.10.1016/B978-075068070-7/50017-7Search in Google Scholar

Florez-Frias, E.A., Barba, V., Lopez-Sesenes, R., Landeros-Martínez, L.L., Flores-De los Ríos, J.P., Casales, M., and Gonzalez-Rodriguez, J.G. (2021). Use of a metallic complex derived from Curcuma longa as green corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in sulfuric acid. Int. J. Corros. 6695299: 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6695299.Search in Google Scholar

Guiamet, P.S. and Saravia, S.G.G.D. (2005). Laboratory studies of biocorrosion control using traditional and environmentally friendly biocides: an overview. Lat. Am. Appl. Res. 35: 295–300.Search in Google Scholar

Guo, X.P., Song, G.L., Hu, J.Y., and Huang, D.B. (2013). Corrosion inhibition of magnesium (Mg) alloys. In: Song, G.L. (Ed.), Corrosion prevention of magnesium alloys. Woodhead Publishing, New Delhi, pp. 72–75.10.1533/9780857098962.1.61Search in Google Scholar

Guo, Y., Meng, T., Wang, D., Tan, H., and He, R. (2017). Experimental research on the corrosion of X series pipeline steels under alternating current interference. Eng. Fail. Anal. 78: 87–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2017.03.003.Search in Google Scholar

Hayat, S., Sabri, A.N., and McHugh, T.D. (2018). Chloroform extract of turmeric inhibits biofilm formation, EPS production and motility in antibiotic resistant bacteria. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 63: 325–338, https://doi.org/10.2323/jgam.2017.01.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Jayaraman, A., Earthman, J., and Wood, T. (1997). Corrosion inhibition by aerobic biofilms on SAE 1018 steel. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 47: 62–68, https://doi.org/10.1007/s002530050889.Search in Google Scholar

King, R.A. and Miller, J.D.A. (1971). Corrosion by the sulphate-reducing bacteria. Nature 233: 491–492, https://doi.org/10.1038/233491a0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Lan, G., Chen, C., Liu, Y., Lu, Y., Du, J., Tao, S., and Zhang, S. (2017). Corrosion of carbon steel induced by a microbial enhanced oil recovery bacterium Pseudomonas sp. SWP-4. RSC Adv. 7: 5583–5594, https://doi.org/10.1039/c6ra25154d.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, H., Meng, G., Li, W., Gu, T., and Liu, H. (2019). Microbiologically influenced corrosion of carbon steel beneath a deposit in CO2-saturated formation water containing Desulfotomaculum nigrificans. Front. Microbiol. 1298: 1–13.10.3389/fmicb.2019.01298Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Luo, H., Li, Z., Mingers, A.M., and Raabe, D. (2018). Corrosion behavior of an equiatomic CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy compared with 304 stainless steel in sulfuric acid solution. Corrosion Sci. 134: 131–139, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2018.02.031.Search in Google Scholar

Malik, P. and Mukherjee, T.K. (2014). Structure-function elucidation of antioxidative and prooxidative activities of the polyphenolic compound curcumin. Chin. J. Biol. 2014: 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/396708.Search in Google Scholar

Mazón, O.S., Calderon, J.P., Arteaga, C.C., Hernandez, J.J.R., Gutierrez, J.A.A., and Gomez, L.M. (2014). EIS evaluation of Fe, Cr, and Ni in NaVO3 at 700°C. J. Spectrosc. 2014: 949168.10.1155/2014/949168Search in Google Scholar

Moradi, M., Duan, J., and Du, X. (2013). Investigation of the effect of 4, 5-dichloro-2-n-octyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one inhibition on the corrosion of carbon steel in Bacillus sp. inoculated artificial seawater. Corrosion Sci. 69: 338–345, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2012.12.017.Search in Google Scholar

Özkir, D., Bayol, E., Gurten, A.A., and Surme, Y. (2013). Thermodynamic study and electrochemical investigation of calcein as corrosion inhibitor for low-carbon steel in hydrochloric acid. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 58: 2158–2167.10.4067/S0717-97072013000400056Search in Google Scholar

Parthipan, P., Narenkumar, J., Elumalai, P., Preethi, P.S., Nanthini, A.U.R., Agrawal, A., and Rajasekar, A. (2017). Neem extract as a green inhibitor for microbiologically influenced corrosion of carbon steel API 5LX in a hypersaline environment. J. Mol. Liq. 240: 121–127, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2017.05.059.Search in Google Scholar

Pilić, Z., Dragičević, I., and Martinović, I. (2019). The anti-corrosion behaviour of Saturejamontana L. extract on iron in NaCl solution. Open Chem. 17: 1087–1094.10.1515/chem-2019-0126Search in Google Scholar

Priyanka and Khanam, S. (2018). Influence of operating parameters on supercritical fluid extraction of essential oil from turmeric root. J. Clean. Prod. 188: 816–824, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.052.Search in Google Scholar

Pusparizkita, Y.M., Schmahl, W., Setiadi, T., Ilsemann, B., Reich, M., Devianto, H., and Harimawan, A. (2020). Evaluation of bio-corrosion on carbon steel by Bacillus megateriumin biodiesel and diesel oil mixture. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 52: 370–384, https://doi.org/10.5614/j.eng.technol.sci.2020.52.3.5.Search in Google Scholar

Rakshit, M. and Ramalingam, C. (2010). Screening and comparison of antibacterial activity of Indian spices. J. Exp. Sci. 1: 33–36.Search in Google Scholar

Sarkar, T. and Hussain, A. (2016). Photocytotoxicity of curcumin and its iron complex. Enzyme Eng. 5: 143, https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-6674.1000143.Search in Google Scholar

Sharma, A., Manivannan, R., and Victoria, S.N. (2020). Investigation of SRB induced biocorrosion of low-carbon steel and its control. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 97: 1029–1032.Search in Google Scholar

Sharma, M., Liu, H., Chen, S., Cheng, F., Voordouw, G., and Gieg, L. (2018). Effect of selected biocides on microbiologically influenced corrosion caused by Desulfovibrio ferrophilus IS5. Sci. Rep. 8: 16620–16632, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34789-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Sharma, M., Thakur, M.P., Saini, R.V., Kumar, R., and Torino, E. (2020). Unveiling antimicrobial and anticancerous behavior of AuNPs and AgNPs moderated by rhizome extracts of Curcuma longa from diverse altitudes of Himalaya. Sci. Rep. 10: 1093, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67673-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Shi, F., Zhang, L., Yang, J., Lu, M., Ding, J., and Lia, H. (2016). Polymorphous FeS corrosion products of pipeline steel under highly sour conditions. Corrosion Sci. 102: 103–113, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2015.09.024.Search in Google Scholar

Singh, A.K. (2020). Microbial induced corrosion and industrial economy. In: Microbially induced corrosion and its mitigation. Springer Briefs in Materials. Springer, Singapore.10.1007/978-981-15-8019-2_3Search in Google Scholar

Song, Y., Shi, H., Wang, J., Liu, F., Han, E.H., Ke, W., Jie, G., Wang, J., and Huang, H. (2017). Corrosion behavior of cupronickel alloy in simulated seawater in the presence of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Acta Metall. Sin. 30: 1201–1209, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40195-017-0662-8.Search in Google Scholar

Stenclova, P., Freisinger, S., Barth, H., Kromka, A., and Mizaikoff, B. (2019). Cyclic changes in the amide bands within Escherichia coli biofilms monitored using real-time infrared attenuated total reflection spectroscopy (IR-ATR). Appl. Spectrosc. 73: 424–432, https://doi.org/10.1177/0003702819829081.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

Swaroop, B.S., Victoria, S.N., and Manivannan, R. (2016). Azadirachta indica leaves extract as inhibitor for microbial corrosion of copper by Arthrobacter sulfureus in neutral pH conditions- A remedy to blue green water problem. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 64: 269–278, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtice.2016.04.007.Search in Google Scholar

Szatmari, I., Tudosie, L.M., Cojocaru, A., Lingvay, M., Prioteasa, P., and Visan, T. (2015). Studies on biocorrosion of stainless steel and copper in Czapek Dox medium with Aspergillus niger filamentous fungus. U.P.B. Sci. Bull. B. 77: 91–102.Search in Google Scholar

Tang, I.D. (2020). Corrosion atlas. In: Khoshnaw, F. and Gubner, R. (Eds.), Corrosion atlas case studies. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands, pp. 1–58.10.1016/B978-0-12-818760-9.00001-5Search in Google Scholar

Teow, S.Y., Liew, K., Ali, S.A., Khoo, A.S.B., and Peh, S.C. (2016). Antibacterial action of curcumin against Staphylococcus aureus: a brief review. J. Trop. Med. 2016: 2853045, https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2853045.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Tyagi, P., Singh, M., Kumari, H., Kumari, A., and Mukhopadhyay, K. (2015). Bactericidal activity of curcumin I is associated with damaging of bacterial membrane. PLoS One 10: e0121313, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121313.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Victoria, S.N., Sharma, A., and Manivannan, R. (2021). Metal corrosion induced by microbial activity – mechanism and control options. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 98: 100083.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jics.2021.100083.Search in Google Scholar

Villamizar, W., Casales, M., Martinez, L., Chacon-Naca, J.G., and Gonzalez-Rodriguez, J.G. (2008). Effect of chemical structure of hydroxyethyl imidazolines inhibitors on the CO2 corrosion in water–oil mixtures. J. Solid State Electrochem. 12: 193–201.10.1007/s10008-007-0380-7Search in Google Scholar

Yaro, A.S., Khadom, A.A., and Idan, M.A. (2015). Electrochemical approaches of evaluating galvanic corrosion kinetics of copper alloy – steel alloy couple in inhibited cooling water system. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 6: 1101–1104.Search in Google Scholar

Yuniarto, K., Purwanto, Y.A., Purwanto, S., Welt, B.A., Purwadaria, H.K., and Sunarti, T.C. (2016). Infrared and Raman studies on polylactide acid and polyethylene glycol-400 blend. In: AIP conference proceedings, 1725. AIP Publishing, Maryland, USA, p. 020101.10.1063/1.4945555Search in Google Scholar

Zhai, X., Ma, X., Myamina, M., Duan, J., and Hou, B. (2015). Electrochemical study on 4,5-dichloro-2-n-octyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one-added zinc coating in phosphate buffer saline medium with Escherichia coli. J. Solid State Electrochem. 19: 2213–2222, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10008-015-2845-4.Search in Google Scholar

Zhou, Y., Guo, L., Zhao, Z., Zheng, S., Xu, Y., Xiang, B., and Kaya, S. (2018). Anticorrosion potential of domperidone on copper in different concentration of hydrochloric acid solution. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 32: 1485–1502, https://doi.org/10.1080/01694243.2018.1426542.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

The online version of this article offers supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/corrrev-2021-0019).

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- A review on the corrosion resistance of electroless Ni-P based composite coatings and electrochemical corrosion testing methods

- Original Articles

- Water-droplet erosion behavior of high-velocity oxygen-fuel-sprayed coatings for steam turbine blades

- Corrosion characteristics of plasma spray, arc spray, high velocity oxygen fuel, and diamond jet coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution

- Corrosive-wear behavior of LSP/MAO treated magnesium alloys in physiological environment with three pH values

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on microstructure and corrosion resistance of PEO ceramic coating of magnesium alloy

- Investigating the efficacy of Curcuma longa against Desulfovibrio desulfuricans influenced corrosion in low-carbon steel

- Annual Reviewer Acknowledgement

- Reviewer acknowledgement Corrosion Reviews volume 39 (2021)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- A review on the corrosion resistance of electroless Ni-P based composite coatings and electrochemical corrosion testing methods

- Original Articles

- Water-droplet erosion behavior of high-velocity oxygen-fuel-sprayed coatings for steam turbine blades

- Corrosion characteristics of plasma spray, arc spray, high velocity oxygen fuel, and diamond jet coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution

- Corrosive-wear behavior of LSP/MAO treated magnesium alloys in physiological environment with three pH values

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on microstructure and corrosion resistance of PEO ceramic coating of magnesium alloy

- Investigating the efficacy of Curcuma longa against Desulfovibrio desulfuricans influenced corrosion in low-carbon steel

- Annual Reviewer Acknowledgement

- Reviewer acknowledgement Corrosion Reviews volume 39 (2021)