Abstract

The University of Luxembourg, renowned for its multilingual profile, promotes the use of English, French, German and Luxembourgish in its multilingualism policy. English is an important lingua franca in many academic disciplines worldwide, and French, German and Luxembourgish are the administrative languages of Luxembourg. However, data from the ongoing research project “Representations of Linguistic Diversity in Multilingual Universities (RELIDIMU)” reveals a dominance of English and French over German and Luxembourgish in most classroom settings at the University of Luxembourg. This imbalance prompted the design of a trial workshop aimed at familiarising teaching staff with concepts of receptive multilingualism to help them navigate the complexities of teaching and learning in multilingual classrooms and promote cultural and linguistic diversity in alignment with the university’s values. The workshop was given by the university’s Language Centre during the inaugural Teaching Day on the theme “ACT – Advancing Competence in Teaching for Student Success” in February 2024. In this report, we highlight two activities that combine receptive multilingualism with plain language strategies – concepts that, according to data from the research project, are unfamiliar to many members of the teaching staff at the University of Luxembourg. Drawing on participants’ feedback gathered during the trial workshop, we conclude with insights into how we plan to redesign and expand the workshop.

1 Description of context

Luxembourg is a multilingual country with three administrative languages: Luxembourgish, French and German. Notably, the primary language of over 33 % of the population is not one of these three official languages, with Portuguese (15.4 %), Italian (3.6 %), English (3.6 %) and South Slavic languages (2 %) being the largest groups. On average, residents of Luxembourg speak four languages, reflecting the country’s rich linguistic diversity and cultural complexity (see Fehlen et al. 2021).

Much like the country itself, the University of Luxembourg is multilingual by law, with English, French and German as official teaching languages. In 2020, the university adopted a policy on multilingualism, which outlines the roles that languages play in teaching and learning, research and administration.[1] The University of Luxembourg Language Centre (ULLC) is responsible for implementing and monitoring the multilingualism policy, with a particular focus on language training for academic literacies in the university’s teaching languages. Through its research focus on multilingual pedagogy in higher education, the ULLC fosters quality language education while promoting linguistic diversity and intercultural exchange. It supports university members within this multilingual educational landscape and encourages inclusive learning in alignment with the institution’s values.

The trial workshop and activities presented in this paper were designed for the University of Luxembourg’s inaugural initiative “ACT – Advancing Competence in Teaching for student success” in February 2024. The aim of ACT is to support the university teaching community and encourage sharing and collaboration. A total of nine workshops were offered (partly in parallel) over one day, with 94 participants attending the event. Each workshop was limited to 1 hour. Our workshop, entitled “Teaching and Learning in the Multilingual Classroom”, was part of the ULLC’s efforts to support teaching staff in addressing the complexities of multilingual classrooms and promoting inclusive learning. Twenty-five experienced teaching staff members and early-career academics from all three university faculties registered for the workshop. The workshop involved two short activities to train receptive language skills, applying the intercomprehension and lingua receptiva (LaRa) approaches combined with plain language strategies. By integrating plain language strategies into the receptive multilingualism approach, the goal was to enhance comprehension, ensuring that participants with limited language skills or lower proficiency levels could engage effectively in classroom interaction. Inspiration for the workshop came from the qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews with 13 teaching staff members and the open-ended questions of an online questionnaire completed by 68 Bachelor students, with balanced representation across the three university faculties, collected through the “Representations of Linguistic Diversity in Multilingual Universities (RELIDIMU)” project. Overall, 12 of the 13 teaching staff members interviewed and 66 % of the undergraduate students who completed the questionnaire indicated that they speak and/or understand the three university languages: English, French and German. More than half of the teaching staff interviewed, and nearly half of the participating students also speak or understand Luxembourgish as well as other languages, such as Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, Dutch or Arabic, with varying levels of proficiency.

However, participants reported that they are mainly exposed to French and English in the university context, while German and Luxembourgish play a minor role, and other languages hardly ever appear. Specifically, students estimated that the average exposure to languages other than the university’s official ones is less than 3 %.

The linguistically rich environment at the University of Luxembourg and the reported dominance of English and French over German, Luxembourgish and other languages in most university teaching settings motivated us to design a workshop encouraging multilingualism and promoting the use and learning of underrepresented languages in this context.

2 Receptive multilingualism approaches to teaching and learning

Based on the data briefly presented in Section 1, we opted for receptive multilingualism approaches when designing activities for the workshop. As teaching staff and students are often highly proficient in a Romance or Germanic language and speak one or two additional languages at varying levels of proficiency, there is significant potential for mutual understanding, particularly among European languages.

In practice, we designed one reading comprehension activity based on the concept of intercomprehension and one oral activity based on the concept of lingua receptiva. Intercomprehension is defined as comprehension of a (foreign) language or linguistic variety without having acquired it by formal learning or in its cultural environment.[2] This approach is considered most effective among languages that are typologically closely related, such as European languages (see Carrasco Perea et al. 2008; Hufeisen and Marx 2007; Klein and Reissner 2006; McCann et al. 1999; Meißner 2016). Furthermore, especially in academic discourse, a significant number of terms derive from Greek and Latin origins (so-called internationalisms), contributing to a shared linguistic foundation among various languages. In academic discourse this commonality extends to similar structural elements, such as formal language use and text organisation (see Deroey et al. 2019).

Lingua receptiva (LaRa) also falls under the concept of receptive multilingualism. Here, mutual understanding occurs not because of linguistic similarities but because speakers have acquired the language, either being raised with it or having learned it later in life. As a result, they can use their receptive skills to understand their communication partner, even if they are not proficient enough to actively produce the language themselves (Rehbein et al. 2010). At the University of Luxembourg, where teaching staff and undergraduate students are often motivated to learn languages and acquire at least basic linguistic skills in the third university teaching language or speak an additional language, LaRa can be effectively employed for classroom interaction in a more structured way.

For our activities, we decided to combine receptive multilingualism with plain language strategies for three key reasons. First, in academic contexts, plain language strategies can be applied to academic genres such as abstracts or summaries (Stoll et al. 2022) to help novice students or second language learners familiarise themselves with a topic before engaging in deeper exploration. Second, written or oral communication in plain language helps participants with lower language skills overcome barriers and engage more effectively in classroom communication. Third, unlike receptive multilingualism, plain language is a concept already somewhat familiar to university teaching staff, allowing us to build upon their existing knowledge in our workshop activities. As well as using visual graphics to minimise reliance on text, one teaching staff member, for example, shared in an interview that she uses “a simpler language with the technical words in it”, describing it as a language “in the common range […] that people will understand”.

3 Intercomprehension activity

3.1 Objectives

The first workshop activity demonstrated the concept of intercomprehension. The goal was to encourage discussion on how abstracts and short summaries can be used to briefly introduce topics in various languages, while also fostering reflection on diverse cultural approaches to academic content.

3.2 Material used

To showcase the concept of intercomprehension, we chose a Polish text sample[3] presented and interpreted by Meißner (2008: 4); see example (1). We chose this text because it is written in plain language, is relevant to the academic participants in the workshop, and promotes discussion on the objectives of the activity. Additionally, we anticipated that most workshop participants would not be proficient speakers of this Slavic language.

| Weronika Wilczyńska jest profesorem Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu. Ma bogate doświadczenie w praktycznej dydaktyce językåw obcych. Jej zainteresowania naukowe obejmują psychologiczne aspekty akwizycji językåw, z uwzględnieniem wymiaru kulturowego. Opublikowala z tej dziedziny szereg prac o charakterze teoretycznym i praktycznym. |

3.3 Description of activity

Participants had 1 minute to go through the text and identify its central message, beginning with words that they found familiar and replacing them with words in English or another language. After this initial interpretation, the text resembled the example that appears in Meißner (2008: 4–5), including both words and symbols. Question marks were used in place of Polish words that, from this first read, could not be replaced with equivalents in another language. Brackets, dashes and hyphens were used to include different options and possibilities when trying to translate the text.

| Weronika Wilczyńska (is) [female?] professor at the University (?) Adam(a) Mickiewicza. Weronika Wilczyńska (at/in) Posen. (?) (?) (?) (in) practical/practice didactical/didactics (language/s) (?). [Her/She]? interes (?) (?) (?) psychologic aspect/s acquisition (of language/s) and (?)(?)(?) (?) culture. (?)publish/ed/ (we exclude publication as we know that the international series of –ation, azione, aciãn… is *atie or something like that) (?)(?)(?)(?)(?)(?)(?) charakterized theoretical (and) practical/in theory and practice. |

An exact translation of the text was not in the scope of the activity. Instead, the focus was on understanding the concept of intercomprehension using a practical example. At the end of the activity, participants engaged in a discussion about the strategies they used to decipher the meaning of the text. In this last step, participants were also invited to reflect on how they could apply intercomprehension to academic texts in their classroom. This enabled them to link the theoretical understanding of the concept with its practical application, enhancing their pedagogical practices.

3.4 Outcomes and observations

The activity demonstrated that, even though participants were not familiar with the concept of intercomprehension, they instinctively applied intercomprehension strategies to the text. Specifically, they began with words and terms of Latin or Greek origin that are similar across many European languages, such as profesorem, Uniwersytetu, praktycznej, dydaktyce, psychologiczne, aspekty, charakterze and teoretycznym, and then inferred the rest of the meaning because of the typologically related structures of this Slavic language and the Romance or Germanic language families.

In the discussion that followed, participants noted that intercomprehension and plain language strategies could be effectively applied to short texts such as summaries, abstracts and presentations of basic disciplinary concepts. Participants also mentioned that applying intercomprehension can encourage individuals to draw on their entire linguistic repertoire, particularly in a multilingual academic context like the University of Luxembourg. However, participants expressed a desire to experiment further with texts and strategies in various languages to determine which languages intercomprehension works best across and how to apply plain language strategies to complex academic texts.

4 Lingua receptiva activity

4.1 Objectives

The second activity of our workshop focused on the concept of lingua receptiva (LaRa). Our goal here was to activate listening and speaking skills which we consider important for inclusive classroom interaction and to encourage the expansion of linguistic skills.

4.2 Description of activity and material used

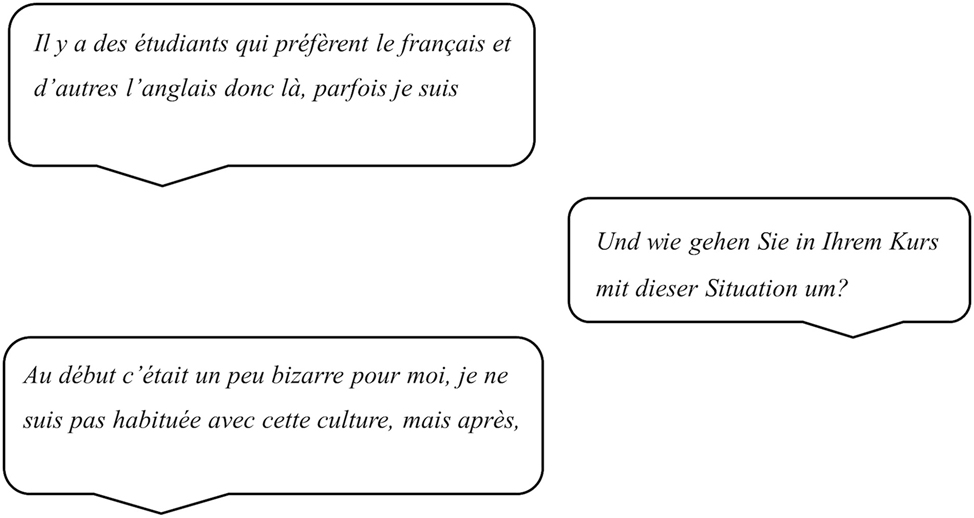

The activity was divided into two parts. In the first part we demonstrated the concept of LaRa using authentic data from interviews with teaching staff that were conducted as part of the RELIDIMU project (Figure 1). The excerpts were carefully selected to be short, in plain language, and relevant to the topic discussed at the workshop. The aim of the demonstration was to contribute to a better understanding of the process and set expectations for the second part of the activity.

Oral conversation in French and German.

In the second part, participants selected a sticker representing their preferred language at the University of Luxembourg (yellow for Luxembourgish, green for German, purple for English or blue for French). They then paired up with someone who had a differently-coloured sticker. In these pairs, participants engaged in a conversation about multilingual teaching practices, following two rules: they had to use their preferred language throughout and both partners were required to use plain language to accommodate varying proficiency levels. After this partner activity, participants reflected on their experiences in an open discussion.

4.3 Outcomes and observations

Participants reported that the activity was engaging, as it provided an opportunity to express themselves in their preferred language, while also training their listening skills. However, it was also challenging, as some mentioned that it was difficult to stick to their preferred language while their partner spoke another language or avoid switching to the lingua franca of English. LaRa therefore appears to be a practice that requires further training to effectively support a conversation partner in developing reflective language skills, foster communication in underrepresented languages and promote inclusive classroom communication.

5 Summary of experiences and future prospects

The aim of our workshop was to familiarise participants with basic concepts and practices of receptive multilingualism applicable to the multilingual academic classroom. Participants’ feedback confirmed that both intercomprehension and LaRa are suitable for our multilingual academic context. The activities and the discussions showed that participants made use of their diverse linguistic and cultural repertoire. In addition, participants suggested that applying the presented multilingual practices in the classroom could provide motivation to learn languages that are less visible or less frequently used in the university context and created a more inclusive environment.

At the same time, the workshop revealed the need for further and more systematic training in multilingual practices. To address this, we have decided to expand the length of the workshop to a half-day format, include more activities, incorporate work with authentic materials from teaching staff, and facilitate activities in smaller groups. In practical terms, we will ask teaching staff in advance to upload texts from their disciplines that they would like to work on during the workshop so that we can provide a step-by-step demonstration of how plain language strategies can be applied to academic texts. Furthermore, we will ask participants to suggest short academic texts in different languages to practise intercomprehension in mixed-language groups. Lastly, we will incorporate more playful and interactive LaRa activities aimed at developing receptive skills. An example of such an activity resembles the board game “Taboo” in which participants pair up and use different languages to help their partner guess the word on their card (Majdańska-Wachowicz et al. 2021).

We consider this type of workshop particularly relevant and beneficial for the multilingual context at the University of Luxembourg. It could also serve as a model for other multilingual university contexts to support both teaching staff and students, fostering intercultural understanding and encouraging language learning.

References

Carrasco Perea, Encarnación, Christian Degache & Yasmin Pishva. 2008. Intégrer l’intercompréhension à l’université. Les Langues Modernes L’Intercompréhension. Travaux en intercompréhension: conceptions, outils et démarches pour la formation en langues 1. 62–74.Suche in Google Scholar

Deroey, Katrien L. B., BirgitHuemer & Eve Lejot. 2019. The discourse structure of literature review paragraphs: a multilingual study. In Birgit Huemer, Eve Lejot & Katrien L. B. Deroey (eds.), Academic writing across languages: Multilingual and contrastive approaches in higher education, 149–177. Vienna: Böhlau.10.7767/9783205208815.149Suche in Google Scholar

EuroComDidact. The site for Romance intercomprehension and foreign language learning. https://eurocomdidact.eu/?page_id=2247&lang=en (accessed 20 November 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Fehlen, Fernand, Peter Gilles, Louis Chauvel, Isabelle Pigeron-Piroth, Yann Ferro & Etienne Le Bihan. 2021. RP 1st results 2021 N°08 Linguistic diversity on the rise. Statec. https://statistiques.public.lu/en/publications/series/rp-2021/2023/rp21-08-23.html (accessed 30 October 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Hufeisen, Britta & Nicole Marx (eds.), 2007. EuroComGerm. Die sieben Siebe: Germanische Sprachen lesen können. Aachen: Shaker.Suche in Google Scholar

Klein, Horst & Christina Reissner. 2006. Basismodul Englisch. Englisch als Brückensprache in der romanischen Interkomprehension. Aachen: Shaker.Suche in Google Scholar

Majdańska-Wachowicz, Urszula, Magdalena Steciąg & Lukáš Zábranský. 2021. Lingua receptiva: An overview of communication strategies. The role of pragmatic aspects in receptive intercultural communication (the case of Polish and Czech). Forum Lingwistyczne 8. 1–18.10.31261/FL.2021.08.08Suche in Google Scholar

McCann, William, Horst Klein & TilbertStegmann. 1999. EuroComRom. The seven sieves: How to read all the romance languages right away. Shaker: Aachen.Suche in Google Scholar

Meißner, Franz-Joseph. 2008. Teaching and learning intercomprehension: a way to plurilingualism and learner autonomy. In Inez de Florio-Hansen (ed.), Towards Multilingualism and cultural diversity. Perspectives from Germany, 37–58. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Meißner, Franz-Joseph. 2016. The core vocabulary of romance plurilingualism (the CVRP- project). In Tina Ambrosch-Baroua & Amina Kropp (eds.), Mehrsprachigkeit und Ökonomie, 91–106. Munich: Open Access LMU.Suche in Google Scholar

Rehbein, Jochen, Jan ten Thije & Anna Verschik. 2010. Lingua receptiva (LaRa) – the quintessence of receptive multilingualism. [Special issue of the International Journal for Bilingualism]. International Journal of Bilingualism 16. 248–268.10.1177/1367006911426466Suche in Google Scholar

Stoll, Marlene, Martin Kerwer, Klaus Lieb & Anita Chasiotis. 2022. Plain language summaries: A systematic review of theory, guidelines and empirical research. PLoS One 17(6): e0268789, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268789.Suche in Google Scholar

University of Luxembourg. 2020. Multilingualism policy. https://www.uni.lu/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2023/07/Multilingualism-Policy-English.pdf (accessed 20 November 2024).Suche in Google Scholar

Wilczyńska, Weronika. 2005. Introduction á la didactique du français langue étrangère. Wstęp do dydaktyki języka francuskiego jako obcego. Krakow: flair.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- 10.1515/cercles-2025-frontmatter2

- Introduction

- Language learning across cultures and continents: exploring best practices of dialogue, collaboration and innovation

- Research Articles

- Students’ perceptions of a sense of belonging in Language Centre courses – What role do teachers play?

- Use of ePortfolios in EAP classes to facilitate self-efficacy through the improvement of creative, organizational, reflective, revision and technological skills

- Boosting learner autonomy through a learner diary: a case study in an intermediate Korean language class

- Examining the (in)accuracies and challenges when rating students’ L2 listening notes

- The relationship between English Medium Instruction and motivation: a systematised review

- Generative AI in teaching academic writing: guiding students to make informed and ethical choices

- Developing writing skills and feedback in foreign language education with chatGPT: a multilingual perspective

- Activity Reports

- Fostering sustainability literacy and action through language education: perspectives and practices across regions

- Receptive communication skills to support inclusive learning in the multilingual classroom: a workshop for university teaching staff

- The challenge of LSP in languages other than English: adapting a language-neutral framework for Japanese

- Promoting autonomous learning amongst Chinese learners of Japanese – introducing flipped learning and learner portfolios

Artikel in diesem Heft

- 10.1515/cercles-2025-frontmatter2

- Introduction

- Language learning across cultures and continents: exploring best practices of dialogue, collaboration and innovation

- Research Articles

- Students’ perceptions of a sense of belonging in Language Centre courses – What role do teachers play?

- Use of ePortfolios in EAP classes to facilitate self-efficacy through the improvement of creative, organizational, reflective, revision and technological skills

- Boosting learner autonomy through a learner diary: a case study in an intermediate Korean language class

- Examining the (in)accuracies and challenges when rating students’ L2 listening notes

- The relationship between English Medium Instruction and motivation: a systematised review

- Generative AI in teaching academic writing: guiding students to make informed and ethical choices

- Developing writing skills and feedback in foreign language education with chatGPT: a multilingual perspective

- Activity Reports

- Fostering sustainability literacy and action through language education: perspectives and practices across regions

- Receptive communication skills to support inclusive learning in the multilingual classroom: a workshop for university teaching staff

- The challenge of LSP in languages other than English: adapting a language-neutral framework for Japanese

- Promoting autonomous learning amongst Chinese learners of Japanese – introducing flipped learning and learner portfolios