Abstract

Non-harmonization of laboratory results represents a concrete risk for patient safety. To avoid harms, it is agreed that measurements by in vitro diagnostic medical devices (IVD-MD) on clinical samples should be traceable to higher-order references and adjusted to give the same result. However, metrological traceability is not a formal claim and has to be correctly implemented, which in practice does not happen for a non-negligible number of measurands. Stakeholders, such as higher-order reference providers, IVD manufacturers, and External Quality Assessment organizers, have major responsibilities and should improve their contribution by unambiguously and rigorously applying what is described in the International Organization for Standardization 17511:2020 standard and other documents provided by the international scientific bodies, such as Joint Committee on Traceability in Laboratory Medicine and IFCC. For their part, laboratory professionals should take responsibility to abandon non-selective methods and move to IVD-MDs displaying proper selectivity, which is one of the indispensable prerequisites for the correct implementation of metrological traceability. The practicality of metrological traceability concepts is not impossible but relevant education and appropriate training of all involved stakeholders are essential to obtain the expected benefits in terms of standardization.

Introduction

It has been affirmed that the lack of standardization[1] in laboratory results may denote an ethical issue as it aims to affect the way laboratory tests are used in order to guarantee optimal care for patients in a global world [1]. Producing non-harmonized results may indeed create confusion in investigating the medical implications of laboratory testing, with an impact on patient safety: at best the patient will not receive the optimal treatment, at worst the patient may receive incorrect treatment [2]. However, it seems that the impact of this issue is underestimated and an optimistic perception of analytical quality in laboratory testing is widespread [3]. The 2015 Institute of Medicine report concludes that “the contribution of the analytical phase to diagnostic errors is small” [4]. Yet, the classical ‘hourglass paradigm’ of laboratory errors, which assign to analytic causes only approximately 10 % of errors, does not consider the contribution from errors caused by non-harmonized results in this phase of the examination process [5]. Medical laboratory customers (both clinicians and patients) are usually not aware about variability of laboratory results: for them, “the laboratory value is true, and a number is a number”. As laboratory users, they expect to get results that fulfil quality requirements for clinical use independent of laboratory location and which in vitro diagnostic medical device (IVD-MD) is employed for a certain measurement. To accomplish this expectation, laboratory professionals should know whether the quality of their measurement results is suitable for clinical use, independent of the IVD-MD type in use [6, 7]. To put it most simply, assays that claim to measure the same analyte should give measurement results that are equivalent, within clinically meaningful limits.

Metrological traceability as the agreed strategy to obtain IVD-MD standardization

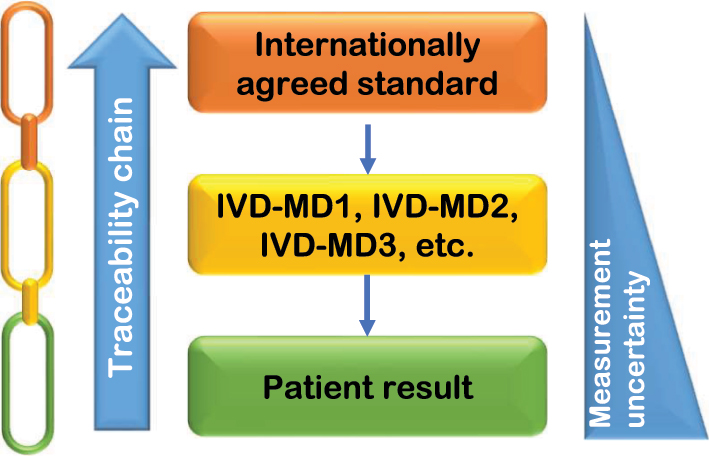

Obtaining comparability among different IVD-MDs should be a priority in order to assure interchangeability of results over time and space, and avoid result misinterpretation and patient harm. As in other scientific, manufacturing, trade, and technological fields, the agreed principle to achieve this outcome is represented by the establishment of metrological traceability of laboratory results obtained with IVD-MDs, in which the measurements are compared (‘anchored’) with a common standard (‘higher-order reference’) and adjusted to give the same result (Figure 1) [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]. This basic approach is also reflected in legislative requirements, e.g., as described in the IVD Regulation 2017/746 of the European Union (EU), which requires IVD manufacturers to ensure traceability of their IVD-MDs to recognized higher-order references [14].

Schematic representation of metrological traceability approach to obtain harmonization of laboratory results. Traceability of patient results to the internationally agreed standard is achieved by an unbroken sequence (‘chain’) of calibrations, each contributing to the measurement uncertainty of results. This provides a common basis for a calibration hierarchy that should be used by all available IVD-MDs for a given measurand. The three different colours in the chain can be used to identify the main parties responsible for the provision and the correct application of the metrological traceability steps, i.e., orange: reference material and/or reference measurement procedure providers; yellow: IVD manufacturers; green: medical laboratories.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 17511:2020 standard, the current normative basis for implementing metrological traceability into Laboratory Medicine, which is now also referenced in the EU Official Journal as harmonized standards of the EU IVD Regulation (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022D0015&from=EN), recognizes that different measurands may require different traceability models, ensuring traceability to the International System of Units (SI) or to a reference system agreed on by convention depending on the measurand nature [15]. In particular, ISO 17511:2000 qualifies six calibration hierarchy models that fulfil the requirement for metrological traceability of calibration to the ‘higher-order reference’. The first three (described in paragraphs 5.2 to 5.4) relate to calibration approaches that are metrologically traceable to SI. The remaining three (described in paragraphs 5.5 to 5.7) are intended to be used when measurements might not be metrologically traceable to SI, using international conventional calibrators (ICC), harmonization protocols, or standard materials arbitrarily selected by individual IVD manufacturers [15]. Except for the last calibration hierarchy using internal arbitrarily defined standards, frequently different for each manufacturer, the overall expected outcome is the achievement of result harmonization for a given measurand among different IVD-MDs [16].

Applicability of the metrological traceability concept: undoubtedly a not easy path

Traceability is not only a formal claim, but has to be correctly implemented [6]. Practical efforts began in the 1970s and international initiatives for improving standardization were launched by key organizations, such as the IFCC, World Health Organization (WHO), U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and European Commission’s Joint Research Centre [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. However, whereas procedures and protocols for standardizing measurements have been established and successfully applied in efforts focusing on serum total cholesterol, C-reactive protein, immunoglobulins, some important enzymes (i.e., creatine kinase and γ-glutamyltranspeptidase), and blood glycated hemoglobin, investigations of intercomparison data utilizing native biological samples demonstrated that, even for some commonly used measurands, inter-assay variability contributions are still remarkable and do lead to possible consequences in clinical decision making [24], [25], [26], [27]. Importantly, even in cases of end-user IVD-MDs for which the calibration hierarchy includes available certified reference materials (RM) and/or reference measurement procedures (RMP), harmonization may still not be achieved [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34].

Why are we still not there in a non-negligible number of cases? Table 1 lists the major issues that can explain the situation, together with the relevant responsibilities and available solutions. The hope is that readers can identify themselves as one of the different mentioned stakeholders and use the table to learn what they can actively due to be part of the solution.

Major factors that may negatively influence or oppose the correct implementation of metrological traceability and the obtaining of harmonized laboratory results, together with the relevant responsibilities and proposed solutions.

| Factor | Responsible stakeholders | Proposed solution |

|---|---|---|

| More than one ‘higher-order reference’ available (when evidence of equivalence between them is not provided) | Reference material and/or reference measurement procedure providers | Provide evidence of the extent-of-equivalence (i.e., lack of non-negligible bias) through a comparison with ‘higher-order reference(s)’ already in use, as per JCTLM policy [44] |

| Commutability of the reference material selected to transfer trueness from the top of the calibration hierarchy to IVD-MD calibrators not assessed | Reference material providers, IVD manufacturers |

Apply the recommendations of the IFCC Working Group on Commutability in Metrological Traceability [46, 48], [49], [50], [51] |

| EQA programs using commutable materials appropriately value assigned seldom available | EQA program organizers | Apply the requirements for the use of EQA programs in the evaluation of the IVD-MD performance in terms of metrological traceability [7] |

| Lacking information on how IVD manufacturers have implemented and validated the calibrator traceability to the selected ‘higher-order reference’ | IVD manufacturers | Fulfil clause 4.1.b of ISO 17511:2020 [15] asking in detail for the following information: (a) indication of higher-order reference used to assign traceable values to calibrators; (b) which internal calibration hierarchy has been applied, with a detailed description of each step; (c) the combined MU of calibrators, and which, if any, acceptable limits for this MU were applied in the validation of the IVD-MD |

| Continual use of methods that lack measurement selectivity | Laboratory professionals | Strongly support the choice of selective assays by the international professional bodies by education of their members [16] |

-

JCTLM, Joint Committee on Traceability in Laboratory Medicine; IVD-MD, in vitro diagnostic medical device; EQA, External Quality Assessment; MU, measurement uncertainty.

Showcase serum ferritin

Here I will use the serum ferritin testing as a didactic example to discuss these aspects. Serum ferritin is the test of choice for diagnosis of iron deficiency and clinical practice guidelines advocate use of specific decision thresholds for its clinical application, which require close agreement among IVD-MDs for ferritin measurements [35]. Indeed, the common belief is that laboratory methods used to determine ferritin concentrations in serum have comparable accuracy enabling an adequate harmonization status for medical decision-making [36, 37]. A recent study has however shown that current ferritin IVD-MDs are still not sufficiently harmonized, complicating and potentially misleading the result interpretation [34]. In particular, in a simulation using clinical samples the ability of confirming an iron deficiency status varied significantly according to different IVD-MDs employed. Due to a poor inter-assay agreement, the same patient could be diagnosed as having iron deficiency anemia or not by simply changing the commercial IVD-MD for measuring ferritin.

With regard to the calibration hierarchy, ferritin belongs to the ISO 17511 cases with an ICC at the top with value assigned by an international protocol that defines the measurand [15]. The first ICC (containing human liver ferritin obtained postmortem) was released in 1985 as WHO International Standard (IS) code 80/602 and, when depleted, it was replaced by the second ICC (WHO IS code 80/578, containing human spleen ferritin from splenectomised patients with transfusion iron overload) [38]. However, the value of the second ICC was not traced to that of the first ICC, with a new traceability chain therefore put in place [39]. On the contrary, following released ICCs (WHO IS code 94/572 and WHO IS code 19/118) were value assigned assuring continuity with IS 80/578 [40, 41]. Unfortunately, the existence of two calibration hierarchies (the former with at the top IS 80/602 and the latter with at the top IS 80/578) introduced a between-calibration bias of approximately 5–10 %, which is entirely transferred to commercial immunoassays if both hierarchies are alternatively employed by various IVD manufacturers [39, 42]. This has a practical impact even today because some manufacturers (e.g., Abbott and Roche) still claim calibration traceability to the IS 80/602, while others (e.g., Beckman Coulter and Siemens) recalibrated their IVD-MDs to the second or third IS when they became available, with the practical consequence to introduce a substantial disagreement due to the bias outlined above. To avoid this problem, the Joint Committee on Traceability in Laboratory Medicine (JCTLM) recommends that preliminary investigations should be carried out to understand the implications of introducing a new calibration hierarchy for a certain measurand for patient clinical results before proceeding with adoption of newly characterized ‘higher-order reference’ [43]. The JCTLM requires demonstration of extent-of-equivalence to an existing higher-order reference (represented by the ICC in the case of ferritin) when a new candidate reference is characterized in order to check similarity in measurand definition and avoid the introduction of a bias in the calibration hierarchies of commercially available IVD-MDs [44].

Commutability is the ability of an RM to show inter-assay properties comparable to those of human samples [45]. Safe implementation of metrological traceability requires a commutable RM for directly transfer trueness from the top of the calibration hierarchy to IVD-MD calibrators [46]. Non-commutability of an RM means that using it for calibration will introduce a bias in the calibrated IVD-MD, with wrong results for measured clinical samples [16, 47]. None of the four mentioned WHO ISs for ferritin was originally assessed for commutability when released, sometimes justifying this failure with the wrong belief that “there is no formal requirement for a commutability study when a new IS is characterized for replacing the previous one” [41]. When the commutability of one of these IS (94/572) was independently assessed, results showed that for only two out of four tested IVD-MDs the IS 94/572 fulfilled the established commutability criteria [34]. It is therefore highly possible that a non-commutability of employed WHO ISs for at least some commercial IVD-MDs may have a causal role in the significant differences among ferritin concentrations assayed by different IVD-MDs. Further efforts should be made to produce commutable RM and to ensure that they are fit for use on the harmonization of patient results, preferentially by applying the recommendations of the IFCC Working Group on Commutability in Metrological Traceability [48], [49], [50], [51].

In the last 20 years, many efforts have been dedicated on clarifying and discussing the specific requirements for the applicability of information given by External Quality Assessment (EQA) programs in the evaluation of the IVD-MD performance in terms of metrological traceability of the performed measurements [3, 7, 22, 52], [53], [54], [55]. A unique benefit of this type of programs is their ability of identifying measurands that need improved harmonization and stimulating standardization initiatives that are required to support the use of clinical practice guidelines [7, 56]. Unfortunately, the majority of current EQA programs are not adequate to assess harmonization of laboratory results as, once again, they disregard the commutability of employed materials [45, 54]. Even for ferritin, EQA programs paying attention to the commutability of their samples could help in better understanding the status of measurements and give information about the level of their harmonization. Some years ago, a pilot study using a commutable serum sample already showed an excessive inter-method difference of ferritin immunoassays, concluding that “traceability to reference materials as claimed by the manufacturers did not lead to acceptable harmonization” [57]. A limitation of that study was however the way used for establishing the target value of EQA material, which was defined as the total mean value determined from single mean values obtained for each IVD-MD group. Using this approach, it was impossible to establish the trueness of ferritin values provided by various IVD-MDs. While the information about the inter-assay variability was credible, data about the correctness of system alignment to higher-order references were lacking. In that study the Beckman Coulter system appeared to show a marked negative bias, although in a following study using the WHO IS 94/572 recovery to judge IVD-MD alignments, this was the only assay yielding a recovery close to 100 %, therefore showing a quite perfect alignment to the ICC [34]. Other ways of determining the target value of (commutable) EQA materials should be applied to understand if IVD-MDs show a good alignment to the selected references. The best option is the value assignment with RMP, when available [3, 7]. If an RMP is lacking, as in the case of serum ferritin, the validation of metrological traceability of IVD-MD values through an EQA strategy should employ examination of commutable samples intended for use as trueness control material (TCM) [15]. Unfortunately, this option remains so far very difficult because, as reported above, an RM/ICC with commutability confirmed for the available IVD-MDs to be used as TCM is currently not available for ferritin. A sustainable strategy involving EQA organizers together with TCM providers (possibly under a consortium structure) to make this approach more feasible and cost effective is urgently needed.

Finally, an exhaustive information on how IVD manufacturers have procedurally implemented the calibrator traceability to the selected ‘higher-order reference’ is usually lacking. Although the ISO 17511:2020 is clear in asking for “a description of the calibration hierarchy, usually consisting of alternating pairs of measurement procedures and RMs, establishing an unbroken sequence of value transfers, starting with the highest order reference system element available and culminating in measured quantity values for human samples using the IVD-MD” (clause 4.1.b) [15], it has been noted that available information about the procedural implementation of calibration hierarchy by IVD manufacturers is often poorly described and reference providers are only mentioned without context on how they are used to establish traceability [58, 59]. As the ISO 17511:2020 is now harmonized with the IVD Regulation by the EU, it should be pointed out that this standard is no longer just an informative document for the IVD manufacturers, but it has become a normative reference to the Regulation, obliging the industry to implement metrological traceability as described in the document. For instance, to reach ferritin concentrations in the IVD-MD measurement ranges, the available ICC must be diluted with a matrix ensuring similarity to clinical samples. As the ICC provider did not proceduralize a dilution, this step, performed differently by individual manufacturers, may introduce issues regarding suitability for use of the diluted material and correctness of traceability implementation [34, 60]. Therefore, it would be desirable to produce an ICC for ferritin to be specifically used for implementing traceability in the physiological and pathophysiological concentration ranges without dilution, an aspect unfortunately neglected even with the recent release of the 4th WHO standard for ferritin WHO IS 19/118, having a ferritin concentration of 10,500 μg/L, approximately 100 times the reference individual concentrations [41].

Very importantly, the mentioned study by Braga et al. [34] also described the practical approach that might be undertaken to compensate for or reduce the effects of IVD-MD differences, and obtain harmonized ferritin results in a relatively short period (Figure 2). The two proved premises to be considered were: (a) as Beckman Access correctly recovered the certified value of IS 94/572 (deemed commutable for this system), it may be selected as surrogate RMP, and (b) the bias detected for other evaluated IVD-MDs, even if sometimes large, is essentially proportional. In this situation, using the correction factors for each IVD-MD derived from obtained regression slope values vs. Access to perform a mathematical recalibration of systems other than Access made it possible to harmonize IVD-MDs for ferritin to the extent that clinical decision thresholds might be used [34]. In particular, prior to recalibration, the inter-assay CV in the ferritin concentrations lower than physiological range was 24.5 % and, following recalibration, this was reduced to <5.0 % [34].

![Figure 2:

Description of the practical applicability of metrological traceability concepts to obtain harmonized ferritin results on clinical samples, taking into account the status of marker measurements in terms of information derived by the study of Braga et al. [34]. The notation m.3 to m.7 corresponds to the sequence of materials, and the notation p.3 to p.7 corresponds to the sequence of measurement procedures, used in the corresponding calibration hierarchy in ISO 17511:2020 (clause 5.5 – Cases with an international conventional calibrator that defines the measurand). WHO IS, World Health Organization International Standard; RMP, reference measurement procedure; MP, measurement procedure; IVD-MD, in vitro diagnostic medical device.](/document/doi/10.1515/cclm-2024-0428/asset/graphic/j_cclm-2024-0428_fig_002.jpg)

Description of the practical applicability of metrological traceability concepts to obtain harmonized ferritin results on clinical samples, taking into account the status of marker measurements in terms of information derived by the study of Braga et al. [34]. The notation m.3 to m.7 corresponds to the sequence of materials, and the notation p.3 to p.7 corresponds to the sequence of measurement procedures, used in the corresponding calibration hierarchy in ISO 17511:2020 (clause 5.5 – Cases with an international conventional calibrator that defines the measurand). WHO IS, World Health Organization International Standard; RMP, reference measurement procedure; MP, measurement procedure; IVD-MD, in vitro diagnostic medical device.

This is not the end: selectivity as a stumbling block to the standardization strategy

In addition to the use of a commutable RM as common calibrator, to provide reported values that are harmonized with other available end-user IVD-MDs, each end-user measurement procedure should have identical, or at least very similar, selectivity for the defined measurand, without influence from components of the sample matrix other than the intended analyte [15]. Although this basic and indispensable prerequisite for correctly implementing metrological traceability was first emphasized more than 25 years ago [61, 62], today we are still facing with end-users (and industry) that do not abandon non-selective methods even for measuring common analytes.

In an IFCC recommendation written in 2008 promoting the use of enzymatic assays for measuring serum creatinine, the first chapter started with a peremptory statement: “standardization does not correct for analytical non-selectivity problems” [63]. It is well known that as a result of reaction with plasma pseudo-creatinine chromogens, methods based on alkaline picrate reaction overestimate true serum creatinine concentrations. This still remains valid even after potential elimination of the error by introducing a steady adjustment in the assay calibration with a negative offset to ‘compensate’ the positive intercept due to the pseudo-creatinine contribution of plasma substances other than creatinine, which is actually of different magnitude in individuals with different pathologies [64]. The impact of this non-selectivity bias on creatinine measurements has a demonstrated clinical relevance and may cause major alterations in the number of subjects classified as having different grades of reduced kidney function [65, 66]. Nevertheless, it is disappointing to see in a recent survey performed by the EFLM Task Group on Chronic Kidney Disease that still approximately 60 % of the responding European laboratories use non-selective assays [67]. It is therefore advisable that, before to taking position on which equation should be used for estimating glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (e.g., Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Consortium 2009 vs. 2021 version), the international professional bodies more strongly support the choice of selective creatinine assays by medical laboratories in order to report an accurate eGFR in all the pertinent clinical situations.

The lack of harmonization in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values used in hepatology and the subsequent risk of using guideline-recommended fixed cut-offs for deciding further patient triage has been largely debated [26, 68]. Various scientific contributions explained that the primary reason of this non-harmonized situation of ALT measurements is the use by medical laboratories of various IVD-MDs with different selectivity for this enzyme [22, 26, 69, 70]. As the internationally agreed measurand definition of ALT catalytic concentration is the rate of conversion of NADH in the 2002 IFCC RMP, which defines the reaction conditions, only ALT IVD-MDs incorporating pyridoxal-5-phosphate as IFCC RMP does may give the same selectivity and provide a solid basis for harmonization of enzyme measurements [70, 71]. The last available national assessment of ALT measurements among Canadian laboratories has however revealed a between-laboratory CV for ALT of 25 %, which is clearly not compatible with an interchangeability of results from different marketed IVD-MDs [72].

The measurement of serum albumin is the last example that I would like to provide to explain the great importance of choosing selective methods for obtaining result harmonization. Although this measurand has indisputable clinical value, it is perplexing to note the lack of harmonization showed in well conducted studies [73, 74]. The situation is primarily compromised by the lack of analytical selectivity of chromogenic methods (as they measure both albumin and other globulins in serum), which are however still employed by the great majority of medical laboratories worldwide [75]. It is interesting to note that the strong association of low serum albumin concentrations with severe COVID-19 found during the first wave of the pandemic in Italy by using immunoturbidimetric assays specific for the protein measurements, was not replicated in the United States COVID-19 patients, in which albumin was measured by non-selective bromocresol green methods [76, 77]. The lack of selectivity of the latter methods, especially at low albumin and high globulin (including ‘acute phase reactants’) concentrations (i.e., the typical COVID-19 situation) may have negatively influenced the expected association, disabling the use of serum albumin to predict in-hospital death in the American study because of spuriously higher albumin values measured with non-selective methods [78].

The choice of IVD-MDs that are suitable for the clinical application of the measurements, including their harmonization, represents one of the main responsibilities of our profession. The commercial availability of methods with different selectivity for a given analyte points to the need for laboratory professionals to take responsibility to move to assays displaying optimal selectivity, which is one of the indispensable prerequisites for the correct implementation of metrological traceability. If users continue to ask for and buy non-selective assays, IVD manufacturers will continue to produce and market them. The often-raised issue of increased reagent costs when a selective assay replaces a non-selective one is a false problem. The value of a laboratory test must be indeed evaluated according to its influence on medical care, and the cost aspects in medical laboratories must be considered in the wider overall context of the impact on the health outcomes and not within the narrow focus of pure cost per test [79].

Concluding remarks

In 2017, Christa Cobbaert in her remarkable editorial on this journal observed that “notwithstanding the good intentions of several stakeholders and organizations, the current standardization process is fragmented, allows permissiveness, and does not consider enough the degree of patient harm caused by non-standardization” [80]. In the meantime, the new EU IVD Regulation has reiterated the requirement of traceability of laboratory test results to standards of higher order and ISO 17511:2020 has clarified the recommended practical approaches by describing a set of technical conditions that should be fulfilled to meet the requirements on metrological traceability of the Regulation [14, 15]. The review work of the JCTLM has become highly relevant and, although its database of higher-order references is still not mandated by any regulatory body, the important practical impact and the value added by the provided information is now well established [12]. On the other hand, the notable drawbacks in quality assessment by traditional EQA programs, usually based on consensus to peer groups using the same IVD-MD and use of non-commutable materials, became more and more evident, with participating laboratories usually meeting governmental regulations despite consistently reporting biased results among them [81]. Finally, the idea that IVD-MD and individual laboratory performance should be judged against analytical performance specifications defining the quality required for laboratory results to satisfy clinical needs, has been consolidated [82].

Now all the involved stakeholders, i.e., healthcare authorities, higher-order reference providers, IVD manufacturers, EQA organizers, and laboratory professionals, are expected to make an ultimate quantum leap forward in the way of practicality of metrological traceability concepts to benefit from standardization of laboratory results, with the unsolved shortcomings described in this paper addressed by improving their specific education and training. The lack of awareness by clinicians about the negative impact of interpreting results of IVD-MDs with suboptimal selectivity and unclear, ambiguous, unstandardized metrological traceability should also not be forgotten. Once made aware and brought to state of urgency, the laboratory professionals will have the task to educate awareness among clinicians about the interfering role of non-standardization in the elaboration of their guidelines. The risks to not involve specialists in laboratory medicine in clinical guideline committees to prevent important laboratory-related issues that can influence the panel’s conclusions and recommendations, and subsequent healthcare outcomes, have been previously highlighted [26, 83].

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Competing interests: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Bossuyt, X, Louche, C, Wiik, A. Standardisation in clinical laboratory medicine: an ethical reflection. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1061–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2007.084228.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Almond, A, Ellis, AR, Walker, SW. Scottish Clinical Biochemistry Managed Diagnostic Network. Current parathyroid hormone immunoassays do not adequately meet the needs of patients with chronic kidney disease. Ann Clin Biochem 2012;49:63–7. https://doi.org/10.1258/acb.2011.011094.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Braga, F, Pasqualetti, S, Panteghini, M. The role of external quality assessment in the verification of in vitro medical diagnostics in the traceability era. Clin Biochem 2018;57:23–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.02.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Committee on Diagnostic Error in Health Care; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine; The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. In: Balogh, EP, Miller, BT, Ball, JR, editors. Improving diagnosis in health care. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2015.Search in Google Scholar

5. Plebani, M. Errors in clinical laboratories or errors in laboratory medicine? Clin Chem Lab Med 2006;44:750–9. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2006.123.Search in Google Scholar

6. Panteghini, M. Implementation of standardization in clinical practice: not always an easy task. Clin Chem Lab Med 2012;50:1237–41. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2011.791.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Panteghini, M. Redesigning the surveillance of in vitro diagnostic medical devices and of medical laboratory performance by quality control in the traceability era. Clin Chem Lab Med 2023;61:759–68. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2022-1257.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

8. Müller, MM. Implementation of reference systems in laboratory medicine. Clin Chem 2000;46:1907–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/46.12.1907.Search in Google Scholar

9. Thienpont, LM, Van Uytfanghe, K, Rodriguez Cabaleiro, D. Metrological traceability of calibration in the estimation and use of common medical decision-making criteria. Clin Chem Lab Med 2004;42:842–50. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2004.138.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Panteghini, M. Traceability as a unique tool to improve standardization in laboratory medicine. Clin Biochem 2009;42:236–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.09.098.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

11. White, GH. Metrological traceability in clinical biochemistry. Ann Clin Biochem 2011;48:393–409. https://doi.org/10.1258/acb.2011.011079.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

12. Panteghini, M, Braga, F, Camara, JE, Delatour, V, Van Uytfanghe, K, Vesper, HW, et al.. Optimizing available tools for achieving result standardization: value added by Joint Committee on Traceability in Laboratory Medicine (JCTLM). Clin Chem 2021;67:1590–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvab178.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Seger, C, Kessler, A, Taibon, J. Establishing metrological traceability for small molecule measurands in laboratory medicine. Clin Chem Lab Med 2023;61:1890–901. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2022-0995.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Regulation (EU) 2017/746 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices and repealing Directive 98/79/EC and Commission Decision 2010/227/EU. Off J Eur Union 2017;60:176–332.Search in Google Scholar

15. ISO 17511:2020. In vitro diagnostic medical devices — requirements for establishing metrological traceability of values assigned to calibrators, trueness control materials and human samples. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization (ISO); 2020.Search in Google Scholar

16. Miller, WG, Greenberg, N. Harmonization and standardization: where are we now? J Appl Lab Med 2021;6:510–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/jalm/jfaa189.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

17. Myers, GL, Cooper, GR, Winn, CL, The Centers for Disease Control-National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Lipid Standardization Program. An approach to accurate and precise lipid measurements. Clin Lab Med 1989;9:105–35.10.1016/S0272-2712(18)30645-0Search in Google Scholar

18. Panteghini, M, Myers, GL, Miller, GW, Greenberg, N. The importance of metrological traceability on the validity of creatinine measurement as an index of renal function. Clin Chem Lab Med 2006;44:1187–92. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2006.234.Search in Google Scholar

19. Johnson, AM, Whicher, JT. Effect of certified reference material 470 (CRM 470) on national quality assurance programs for serum proteins in Europe. Clin Chem Lab Med 2001;39:1123–8. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2001.177.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Hoerger, TJ, Wittenborn, JS, Young, W. A cost-benefit analysis of lipid standardization in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis 2011;8:A136.Search in Google Scholar

21. Braga, F, Panteghini, M. Standardization and analytical goals for glycated hemoglobin measurement. Clin Chem Lab Med 2013;51:1719–26. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2013-0060.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Infusino, I, Frusciante, E, Braga, F, Panteghini, M. Progress and impact of enzyme measurement standardization. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017;55:334–40. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2016-0661.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Borrillo, F, Panteghini, M. Current performance of C-reactive protein determination and derivation of quality specifications for its measurement uncertainty. Clin Chem Lab Med 2023;61:1552–7. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2023-0069.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Stepman, HC, Tiikkainen, U, Stöckl, D, Vesper, HW, Edwards, SH, Laitinen, H, et al.. Measurements for 8 common analytes in native sera identify inadequate standardization among 6 routine laboratory assays. Clin Chem 2014;60:855–63. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2013.220376.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Weykamp, C, Secchiero, S, Plebani, M, Thelen, M, Cobbaert, C, Thomas, A, et al.. Analytical performance of 17 general chemistry analytes across countries and across manufacturers in the INPUtS project of EQA organizers in Italy, The Netherlands, Portugal, United Kingdom and Spain. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017;55:203–11. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2016-0220.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Panteghini, M, Adeli, K, Ceriotti, F, Sandberg, S, Horvath, AR. American liver guidelines and cutoffs for “normal” ALT: a potential for overdiagnosis. Clin Chem 2017;63:1196–8. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2017.274977.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Panteghini, M. Lactate dehydrogenase: an old enzyme reborn as a COVID-19 marker (and not only). Clin Chem Lab Med 2020;58:1979–81. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2020-1062.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Infusino, I, Valente, C, Dolci, A, Panteghini, M. Standardization of ceruloplasmin measurements is still an issue despite the availability of a common reference material. Anal Bioanal Chem 2010;397:521–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-009-3248-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Carobene, A, Ceriotti, F, Infusino, I, Frusciante, E, Panteghini, M. Evaluation of the impact of standardization process on the quality of serum creatinine determination in Italian laboratories. Clin Clin Acta 2014;427:100–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2013.10.001.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30. Braga, F, Frusciante, E, Infusino, I, Aloisio, E, Guerra, E, Ceriotti, F, et al.. Evaluation of the trueness of serum alkaline phosphatase measurement in a group of Italian laboratories. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017;55:e47–50. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2016-0605.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Bargnoux, AS, Piéroni, L, Cristol, JP, Kuster, N, Delanaye, P, Carlier, MC, et al.. Société Française de Biologie Clinique (SFBC). Multicenter evaluation of cystatin C measurement after assay standardization. Clin Chem 2017;63:833–41. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2016.264325.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32. Braga, F, Frusciante, E, Ferraro, S, Panteghini, M. Trueness evaluation and verification of inter-assay agreement of serum folate measuring systems. Clin Chem Lab Med 2020;58:1697–705. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2019-0928.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Ferraro, S, Bussetti, M, Rizzardi, S, Braga, F, Panteghini, M. Verification of harmonization of serum total and free prostate-specific antigen (PSA) measurements and implications for medical decisions. Clin Chem 2021;67:543–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvaa268.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Braga, F, Pasqualetti, S, Frusciante, E, Borrillo, F, Chibireva, M, Panteghini, M. Harmonization status of serum ferritin measurements and implications for use as marker of iron-related disorders. Clin Chem 2022;68:1202–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvac099.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Ministry of Health (British Columbia). Iron deficiency—diagnosis and management. 2019. BCGuidelines.ca. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/bc-guidelines/iron-deficiency#risk-identification [Accessed 29 Mar 2024].Search in Google Scholar

36. Garcia-Casal, MN, Peña-Rosas, JP, Urrechaga, E, Escanero, JF, Huo, J, Martinez, RX, et al.. Performance and comparability of laboratory methods for measuring ferritin concentrations in human serum or plasma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2018;13:e0196576. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196576.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. International Consortium for Harmonization of Clinical Laboratory Results. Summary of measurand harmonization activities: ferritin. https://www.harmonization.net/measurands/ [Accessed 29 Mar 2024].Search in Google Scholar

38. Thorpe, SJ, Walker, D, Arosio, P, Heath, A, Cook, JD, Worwood, M. International collaborative study to evaluate a recombinant L ferritin preparation as an International Standard. Clin Chem 1997;43:1582–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/43.9.1582.Search in Google Scholar

39. Ferraro, S, Mozzi, R, Panteghini, M. Revaluating serum ferritin as a marker of body iron stores in the traceability era. Clin Chem Lab Med 2012;50:1911–6. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2012-0129.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

40. Lotz, J, Hafner, G, Prellwitz, W. Reference values for a homogeneous ferritin assay and traceability to the 3rd International recombinant standard for ferritin (NIBSC code 94/572). Clin Chem Lab Med 1999;37:821–5. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.1999.123.Search in Google Scholar

41. Fox, B, Roberts, G, Atkinson, E, Rigsby, P, Ball, C. International collaborative study to evaluate and calibrate two recombinant L chain ferritin preparations for use as a WHO international standard. Clin Chem Lab Med 2022;60:370–8. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2021-1139.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

42. Blackmore, S, Hamilton, M, Lee, A, Worwood, M, Brierley, M, Heath, A, et al.. Automated immunoassay methods for ferritin: recovery studies to assess traceability to an international standard. Clin Chem Lab Med 2008;46:1450–7. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2008.304.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Miller, WG, Panteghini, M, Wielgosz, R. Implementing metrological traceability of C-reactive protein measurements: consensus summary from the Joint Committee for Traceability in Laboratory Medicine workshop. Clin Chem Lab Med 2023;61:1558–60. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2023-0498.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

44. Joint Committee for Traceability in Laboratory Medicine. Demonstrating the extent-of-equivalence between multiple certified reference materials (CRMs) for the same measurand. JCTLM DBWG P-04A v.4.0, 2023/02/01. https://www.bipm.org/en/committees/jc/jctlm/wg/jctlm-dbwg/publications [Accessed 29 Mar 2024].Search in Google Scholar

45. Braga, F, Panteghini, M. Commutability of reference and control materials: an essential factor for assuring the quality of measurements in Laboratory Medicine. Clin Chem Lab Med 2019;57:967–73. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2019-0154.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Miller, WG, Greenberg, N, Panteghini, M, Budd, JR, Johansen, JV. Guidance on which calibrators in a metrologically traceable calibration hierarchy must be commutable with clinical samples. Clin Chem 2023;69:228–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvac226.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

47. Zegers, I, Beetham, R, Keller, T, Sheldon, J, Bullock, D, MacKenzie, F, et al.. The importance of commutability of reference materials used as calibrators: the example of ceruloplasmin. Clin Chem 2013;59:1322–9. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2012.201954.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

48. Miller, WG, Schimmel, H, Rej, R, Greenberg, N, Ceriotti, F, Burns, C, et al.. IFCC working group recommendations for assessing commutability part 1: general experimental design. Clin Chem 2018;64:447–54. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2017.277525.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Nilsson, G, Budd, JR, Greenberg, N, Delatour, V, Rej, R, Panteghini, M, et al.. IFCC working group recommendations for assessing commutability part 2: using the difference in bias between a reference material and clinical samples. Clin Chem 2018;64:455–64. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2017.277541.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Budd, JR, Weykamp, C, Rej, R, MacKenzie, F, Ceriotti, F, Greenberg, N, et al.. IFCC Working Group recommendations for assessing commutability part 3: using the calibration effectiveness of a reference material. Clin Chem 2018;64:465–74. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2017.277558.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Miller, WG, Keller, T, Budd, J, Johansen, JV, Panteghini, M, Greenberg, N, et al.. IFCC Working Group on Commutability in Metrological Traceability. Recommendations for setting a criterion for assessing commutability of secondary calibrator certified reference materials. Clin Chem 2023;69:966–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvad104.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52. Miller, WG. Specimen materials, target values and commutability for external quality assessment (proficiency testing) schemes. Clin Chim Acta 2003;327:25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-8981(02)00370-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

53. Miller, WG, Jones, GR, Horowitz, GL, Weykamp, C. Proficiency testing/external quality assessment: current challenges and future directions. Clin Chem 2011;57:1670–80. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2011.168641.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Badrick, T, Miller, WG, Panteghini, M, Delatour, V, Berghall, H, MacKenzie, F, et al.. Interpreting EQA – understanding why commutability of materials matters. Clin Chem 2022;68:494–500. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvac002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

55. Jones, GRD, Delatour, V, Badrick, T. Metrological traceability and clinical traceability of laboratory results – the role of commutability in external quality assurance. Clin Chem Lab Med 2022;60:669–74. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2022-0038.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

56. Ferraro, S, Braga, F, Panteghini, M. Laboratory medicine in the new healthcare environment. Clin Chem Lab Med 2016;54:523–33. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2015-0803.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

57. Kristensen, GBB, Rustad, P, Berg, JP, Aakre, KM. Analytical bias exceeding desirable quality goal in 4 out of 5 common immunoassays: results of a native single serum sample external quality assessment program for cobalamin, folate, ferritin, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and free T4 analyses. Clin Chem 2016;62:1255–63. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2016.258962.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

58. Braga, F, Panteghini, M. Verification of in vitro medical diagnostics (IVD) metrological traceability: responsibilities and strategies. Clin Chim Acta 2014;432:55–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2013.11.022.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

59. Braga, F, Infusino, I, Panteghini, M. Performance criteria for combined uncertainty budget in the implementation of metrological traceability. Clin Chem Lab Med 2015;53:905–12. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2014-1240.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

60. Vesper, HW, Miller, WG, Myers, GL. Reference materials and commutability. Clin Biochem Rev 2007;28:139–47.Search in Google Scholar

61. Férard, G, Edwards, J, Kanno, T, Lessinger, JM, Moss, DW, Schiele, F, et al.. Interassay calibration as a major contribution to the comparability of results in clinical enzymology. Clin Biochem 1998;31:489–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0009-9120(98)00038-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

62. Panteghini, M, Ceriotti, F, Schumann, G, Siekmann, L. Establishing a reference system in clinical enzymology. Clin Chem Lab Med 2001;39:795–800. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2001.131.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

63. Panteghini, M, Scientific Division, IFCC. Enzymatic assays for creatinine: time for action. Clin Chem Lab Med 2008;46:567–72. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2008.113.Search in Google Scholar

64. Boutten, A, Bargnoux, AS, Carlier, MC, Delanaye, P, Rozet, E, Delatour, V, et al.. Enzymatic but not compensated Jaffe methods reach the desirable specifications of NKDEP at normal levels of creatinine. Results of the French multicentric evaluation. Clin Chim Acta 2013;419:132–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2013.01.021.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

65. Klee, GG, Schryver, PG, Saenger, AK, Larson, TS. Effects of analytic variations in creatinine measurements on the classification of renal disease using estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Clin Chem Lab Med 2007;45:737–41. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2007.168.Search in Google Scholar

66. Boss, K, Stolpe, S, Müller, A, Wagner, B, Wichert, M, Assert, R, et al.. Effect of serum creatinine difference between the Jaffe and the enzymatic method on kidney disease detection and staging. Clin Kidney J 2023;16:2147–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfad178.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

67. Cavalier, E, Makris, K, Portakal, O, Nikler, A, Datta, P, Zima, T, et al.. Assessing the status of European laboratories in evaluating biomarkers for chronic kidney diseases (CKD) and recommendations for improvement: insights from the 2022 EFLM Task Group on CKD survey. Clin Chem Lab Med 2024;62:253–61. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2023-0987.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

68. Hunt, CM, Lee, TH, Morgan, TR, Campbell, S. One ALT is not like the other. Gastroenterology 2023;165:320–3. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2023.04.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

69. Goossens, K, Van Uytfanghe, K, Thienpont, LM. Trueness and comparability assessment of widely used assays for 5 common enzymes and 3 electrolytes. Clin Chim Acta 2015;442:44–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2015.01.009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

70. Panteghini, M. Documenting and validating metrological traceability of serum alanine aminotransferase measurements: a priority for medical laboratory community for providing high quality service in hepatology. Clin Chem Lab Med 2024;62:249–52. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2023-0900.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

71. Panteghini, M. Serum enzymes. In: Rifai, N, Chiu, RWK, Young, I, Burnham, CAD, Wittwer, CT, editors. Tietz textbook of laboratory medicine, 7th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2023:350 p.Search in Google Scholar

72. Adeli, K, Higgins, V, Seccombe, D, Collier, CP, Balion, CM, Cembrowski, G, et al.. National survey of adult and pediatric reference intervals in clinical laboratories across Canada: a report of the CSCC working group on reference interval harmonization. Clin Biochem 2017;50:925–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.06.006.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

73. Van Houcke, SK, Rustad, P, Stepman, HC, Kristensen, GB, Stöckl, D, Røraas, TH, et al.. Calcium, magnesium, albumin, and total protein measurement in serum as assessed with 20 fresh-frozen single-donation sera. Clin Chem 2012;58:1597–9. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2012.189670.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

74. Bachmann, LM, Yu, M, Boyd, JC, Bruns, DE, Miller, WG. State of harmonization of 24 serum albumin measurement procedures and implications for medical decisions. Clin Chem 2017;63:770–9. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2016.262899.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

75. van Schrojenstein Lantman, M, van de Logt, AE, Prudon-Rosmulder, E, Langelaan, M, Demir, AY, Kurstjens, S, et al.. Albumin determined by bromocresol green leads to erroneous results in routine evaluation of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Chem Lab Med 2023;61:2167–77. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2023-0463.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

76. Aloisio, E, Chibireva, M, Serafini, L, Pasqualetti, S, Falvella, FS, Dolci, A, et al.. A comprehensive appraisal of laboratory biochemistry tests as major predictors of COVID-19 severity. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2020;144:1457–64. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2020-0389-sa.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

77. Hundt, MA, Deng, Y, Ciarleglio, MM, Nathanson, MH, Lim, JK. Abnormal liver tests in COVID-19: a retrospective observational cohort study of 1,827 patients in a major U.S. hospital network. Hepatology 2020;72:1169–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31487.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

78. Pasqualetti, S, Aloisio, E, Panteghini, M. Letter to the Editor: serum albumin in COVID-19: a good example in which analytical and clinical performance of a laboratory test are strictly intertwined. Hepatology 2021;74:2905–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31791.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

79. Panteghini, M. Laboratory community should be more proactive in highlighting the negative impact of analytical non-selectivity of some creatinine assays. Clin Chem 2022;68:723. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvac031.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

80. Cobbaert, C. Time for a holistic approach and standardization education in laboratory medicine. Clin Chem Lab Med 2017;55:311–3. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2016-0952.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

81. Badrick, T, Jones, G, Miller, WG, Panteghini, M, Quintenz, A, Sandberg, S, et al.. Differences between educational and regulatory external quality assurance/proficiency testing schemes. Clin Chem 2022;68:1238–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvac132.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

82. Panteghini, M. What the Milan conference has taught us about analytical performance specification model definition and measurand allocation. Clin Chem Lab Med 2024;62:1455–61. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2023-1257.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

83. Aakre, KM, Langlois, MR, Watine, J, Barth, JH, Baum, H, Collinson, P, et al.. Critical review of laboratory investigations in clinical practice guidelines: proposals for the description of investigation. Clin Chem Lab Med 2013;51:1217–26. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2012-0574.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- CD34+ progenitor cells meet metrology

- Reviews

- Venous blood collection systems using evacuated tubes: a systematic review focusing on safety, efficacy and economic implications of integrated vs. combined systems

- The correlation between serum angiopoietin-2 levels and acute kidney injury (AKI): a meta-analysis

- Opinion Papers

- Advancing value-based laboratory medicine

- Clostebol and sport: about controversies involving contamination vs. doping offence

- Direct-to-consumer testing as consumer initiated testing: compromises to the testing process and opportunities for quality improvement

- Perspectives

- An improved implementation of metrological traceability concepts is needed to benefit from standardization of laboratory results

- Genetics and Molecular Diagnostics

- Comparative analysis of BCR::ABL1 p210 mRNA transcript quantification and ratio to ABL1 control gene converted to the International Scale by chip digital PCR and droplet digital PCR for monitoring patients with chronic myeloid leukemia

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- IVDCheckR – simplifying documentation for laboratory developed tests according to IVDR requirements by introducing a new digital tool

- Analytical performance specifications for trace elements in biological fluids derived from six countries federated external quality assessment schemes over 10 years

- The effects of drone transportation on routine laboratory, immunohematology, flow cytometry and molecular analyses

- Accurate non-ceruloplasmin bound copper: a new biomarker for the assessment and monitoring of Wilson disease patients using HPLC coupled to ICP-MS/MS

- Construction of platelet count-optical method reflex test rules using Micro-RBC#, Macro-RBC%, “PLT clumps?” flag, and “PLT abnormal histogram” flag on the Mindray BC-6800plus hematology analyzer in clinical practice

- Evaluation of serum NFL, T-tau, p-tau181, p-tau217, Aβ40 and Aβ42 for the diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases

- An immuno-DOT diagnostic assay for autoimmune nodopathy

- Evaluation of biochemical algorithms to screen dysbetalipoproteinemia in ε2ε2 and rare APOE variants carriers

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Allowable total error in CD34 cell analysis by flow cytometry based on state of the art using Spanish EQAS data

- Clinical utility of personalized reference intervals for CEA in the early detection of oncologic disease

- Agreement of lymphocyte subsets detection permits reference intervals transference between flow cytometry systems: direct validation using established reference intervals

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Atypical cells in urine sediment: a novel biomarker for early detection of bladder cancer

- External quality assessment-based tumor marker harmonization simulation; insights in achievable harmonization for CA 15-3 and CEA

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Evaluation of the analytical and clinical performance of a high-sensitivity troponin I point-of-care assay in the Mersey Acute Coronary Syndrome Rule Out Study (MACROS-2)

- Analytical verification of the Atellica VTLi point of care high sensitivity troponin I assay

- Infectious Diseases

- Synovial fluid D-lactate – a pathogen-specific biomarker for septic arthritis: a prospective multicenter study

- Targeted MRM-analysis of plasma proteins in frozen whole blood samples from patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study

- Letters to the Editor

- Generative artificial intelligence (AI) for reporting the performance of laboratory biomarkers: not ready for prime time

- Urgent need to adopt age-specific TSH upper reference limit for the elderly – a position statement of the Belgian thyroid club

- Sigma metric is more correlated with analytical imprecision than bias

- Utility and limitations of monitoring kidney transplants using capillary sampling

- Simple flow cytometry method using a myeloma panel that easily reveals clonal proliferation of mature B-cells

- Is sweat conductivity still a relevant screening test for cystic fibrosis? Participation over 10 years

- Hb D-Iran interference on HbA1c measurement

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- CD34+ progenitor cells meet metrology

- Reviews

- Venous blood collection systems using evacuated tubes: a systematic review focusing on safety, efficacy and economic implications of integrated vs. combined systems

- The correlation between serum angiopoietin-2 levels and acute kidney injury (AKI): a meta-analysis

- Opinion Papers

- Advancing value-based laboratory medicine

- Clostebol and sport: about controversies involving contamination vs. doping offence

- Direct-to-consumer testing as consumer initiated testing: compromises to the testing process and opportunities for quality improvement

- Perspectives

- An improved implementation of metrological traceability concepts is needed to benefit from standardization of laboratory results

- Genetics and Molecular Diagnostics

- Comparative analysis of BCR::ABL1 p210 mRNA transcript quantification and ratio to ABL1 control gene converted to the International Scale by chip digital PCR and droplet digital PCR for monitoring patients with chronic myeloid leukemia

- General Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- IVDCheckR – simplifying documentation for laboratory developed tests according to IVDR requirements by introducing a new digital tool

- Analytical performance specifications for trace elements in biological fluids derived from six countries federated external quality assessment schemes over 10 years

- The effects of drone transportation on routine laboratory, immunohematology, flow cytometry and molecular analyses

- Accurate non-ceruloplasmin bound copper: a new biomarker for the assessment and monitoring of Wilson disease patients using HPLC coupled to ICP-MS/MS

- Construction of platelet count-optical method reflex test rules using Micro-RBC#, Macro-RBC%, “PLT clumps?” flag, and “PLT abnormal histogram” flag on the Mindray BC-6800plus hematology analyzer in clinical practice

- Evaluation of serum NFL, T-tau, p-tau181, p-tau217, Aβ40 and Aβ42 for the diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases

- An immuno-DOT diagnostic assay for autoimmune nodopathy

- Evaluation of biochemical algorithms to screen dysbetalipoproteinemia in ε2ε2 and rare APOE variants carriers

- Reference Values and Biological Variations

- Allowable total error in CD34 cell analysis by flow cytometry based on state of the art using Spanish EQAS data

- Clinical utility of personalized reference intervals for CEA in the early detection of oncologic disease

- Agreement of lymphocyte subsets detection permits reference intervals transference between flow cytometry systems: direct validation using established reference intervals

- Cancer Diagnostics

- Atypical cells in urine sediment: a novel biomarker for early detection of bladder cancer

- External quality assessment-based tumor marker harmonization simulation; insights in achievable harmonization for CA 15-3 and CEA

- Cardiovascular Diseases

- Evaluation of the analytical and clinical performance of a high-sensitivity troponin I point-of-care assay in the Mersey Acute Coronary Syndrome Rule Out Study (MACROS-2)

- Analytical verification of the Atellica VTLi point of care high sensitivity troponin I assay

- Infectious Diseases

- Synovial fluid D-lactate – a pathogen-specific biomarker for septic arthritis: a prospective multicenter study

- Targeted MRM-analysis of plasma proteins in frozen whole blood samples from patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study

- Letters to the Editor

- Generative artificial intelligence (AI) for reporting the performance of laboratory biomarkers: not ready for prime time

- Urgent need to adopt age-specific TSH upper reference limit for the elderly – a position statement of the Belgian thyroid club

- Sigma metric is more correlated with analytical imprecision than bias

- Utility and limitations of monitoring kidney transplants using capillary sampling

- Simple flow cytometry method using a myeloma panel that easily reveals clonal proliferation of mature B-cells

- Is sweat conductivity still a relevant screening test for cystic fibrosis? Participation over 10 years

- Hb D-Iran interference on HbA1c measurement