Antibodies targeting enzyme inhibition as potential tools for research and drug development

-

José Manuel Pérez de la Lastra

, Victoria Baca-González

Abstract

Antibodies have transformed biomedical research and are now being used for different experimental applications. Generally, the interaction of enzymes with their specific antibodies can lead to a reduction in their enzymatic activity. The effect of the antibody is dependent on its narrow i.e. the regions of the enzyme to which it is directed. The mechanism of this inhibition is rarely a direct combination of the antibodies with the catalytic site, but is rather due to steric hindrance, barring the substrate access to the active site. In several systems, however, the interaction with the antibody induces conformational changes on the enzyme that can either inhibit or enhance its catalytic activity. The extent of enzyme inhibition or enhancement is, therefore, a reflection of the nature and distribution of the various antigenic determinants on the enzyme molecule. Currently, the mode of action of many enzymes has been elucidated at the molecular level. We here review the molecular mechanisms and recent trends by which antibodies inhibit the catalytic activity of enzymes and provide examples of how specific antibodies can be useful for the neutralization of biologically active molecules

Introduction

The interaction of biological macromolecules is common to all chemical processes of life. The specificity of binding is determined by chemical forces; such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and steric interactions [1,2,3]. Most biological processes; such as signal transduction, and cellular metabolism, are regulated by the binding of ligands to proteins. For example, protein-ligand interactions are critical for deciphering the molecular mechanisms underlying cell activity [4]. Protein-ligand interactions are important, not just for understanding how biological processes are regulated, but also for drug development [5]. A ligand-binding site typically serves as the functional center of a protein, arranging molecules in the right conformation for optimal function, such as catalysis or immune recognition [4, 6, 7].

Life, as we know it, would be impossible without enzymes, which are protein polymers that catalyze biochemical reactions [8]. They reduce the activation energy of the chemical reactions, speeding up the chemical processes that sustain life [9]. Enzymes mediate a wide variety of biological events that take place in the cell every second; such as energy metabolism, macromolecular synthesis, anabolic processes, cell signaling, and cell cycle [10]. Enzymes are also responsible for regulating the concentration of essential substances in the cell. For the formation of an enzyme-substrate complex, a tight fit between protein and ligand is necessary. This requirement explains the specificity found in enzyme-catalyzed activities [11, 12]. On the other hand, the immune system is capable of producing large folded polypeptides (immunoglobulins or antibodies) with high affinity and specificity for almost any synthetic or natural molecule. Therefore, fundamental similarities exist between enzymes and antibodies in terms of binding selectivity, the strength of interaction, and dynamics of formation and dissociation of ligand-protein complexes [13].

Antibodies are one of the most valuable macromolecules for life science research, and they are used in many biomedical disciplines; such as biotechnology, medicine, immunotherapy, and diagnostics [14,15,16]. In some instances, antibodies can modify the function of the antigen molecules toward which they are directed without being necessarily connected to the immune response [17]. The interaction of antibodies, enzymes, and substrates was long ago reviewed by B. Cinader in 1957 to describe the mechanism by which antibodies inhibit enzyme action [18]. The study of enzyme inhibition by specific antibodies is of particular interest, since these systems may be used as models for the study of neutralization of biologically active substances in general and to elucidate the catalytic mechanism of enzymes [19]. Enzyme inhibitors have been demonstrated to have a significant impact in many biological and therapeutic fields, such as fertility control [19], neurological disorders [20], skin diseases [21], or lysosomal storage diseases [22, 23], to name a few. In most cases, the interaction of enzymes with their particular antibodies results in a decrease in their in vitro enzymatic activity [19]. The inhibition of activity by antibodies is attributed to its binding to the enzyme molecule, which stops the catalytic process. This binding may alter the position of amino acid residues in the enzyme reactive functional groups [24]. Additionally, antibodies can act as an inhibitor by altering the structure of the enzyme [25]. These activities are referred to as cogno-effector functions of antibodies, since the process of identification by antibodies leads to a direct functional change in the target molecule in these situations [26].

The use of enzyme inhibitors as therapeutic drugs has been documented throughout the history of pharmacology [27, 28]. There are some situations in which the pharmacological use of inhibitors, for a given enzymatic biochemical reaction, might result in medically useful effects. For example, in the designing of different classes of pharmaceutical drugs, pesticides, or insecticides [29,30,31]. We here review the molecular mechanisms and recent trends by which antibodies inhibit the catalytic activity of enzymes and examples of how specific antibodies can be useful for the neutralization of biologically active molecules.

Enzyme diversity

An enzyme is more than simply a sequence or an active region. It is a whole protein with many distinct chains and structural domains. Multidomain or multi-subunit assemblies are frequently found in nature, contributing to the increase of structural complexity of enzymes and their active sites [32]. In the catalytic site, catalytic residues act either by stabilizing the transition states, or the intermediates, or destabilizing the ground states of the substrates [33, 34]. The active site of enzymes provides a favorable chemical environment for the formation of multiple binding contacts for the transformation of substrates into products [35]. In addition to amino acids, the active site often contains a variety of catalytic entities, such as cofactors, which can be either metal ions or tiny organic molecules. Cofactors allow enzymes to catalyze reactions that would otherwise be impossible [36]. Some enzymes, including homologs, may have diverged to perform diverse activities, each requiring their own active sites [37]. Several hundred enzymes have had their mechanism of action thoroughly characterized experimentally, although this represents just a small portion of the total number of enzymes found in nature. All of the enzymes that have been described to date have been assigned an Enzyme Commission (EC) number, according to their total transformation of the substrate into the product, which has been in use for many years to classify enzymes and which employs a four-level description. The first three levels (class, subclass, and sub-subclass) roughly characterize the overall chemistry that is taking place, while the fourth level (serial number) broadly defines the specificity of the substrate being used in the reaction [38] (Table 1).

Class of enzymes according to the Enzyme Commission (EC) number and the reaction catalyzed.

| Class | Name | Reaction catalyzed |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Oxidoreductase | The oxidation/reduction of a molecule |

| 2 | Transferase | The transfer of a group of atoms from one molecule to another |

| 3 | Hydrolase | Cleavage of a chemical bond by hydrolysis |

| 4 | Lyase | Add/remove atoms to/from a double bond of a molecule |

| 5 | Isomerase | Geometric or structural changes within a molecule |

| 6 | Ligase | Joining of two substrate molecules coupled to the hydrolysis of ATP |

SCOP and CATH are two classification systems for protein structure that are also used for enzymes [39, 40]. CATH is an acronym that stands for Class, Architecture, Topology, and Homologous superfamily and is the most often used classification system. CATH seeks to discover instances when the sequence similarity between two proteins is extremely low, yet the structure-based analysis indicates that they maintain enough similarity to indicate a common ancestor. According to CATH code, there are three levels of structure: the C level describes the secondary structure composition of each domain, the A level describes the shape revealed by orientations of secondary structure units, and the T level describes how the secondary structure units are connected in a specific order. When the structural similarities between proteins belonging to the same T level are high, along with the fact that the proteins perform comparable activities, the proteins are considered to have a common ancestor and are thus classified in the same H level [41]. If an enzyme's CATH code is identical to that of another enzyme, there is a high likelihood that the enzymes’ mechanisms are identical (or extremely similar) to one another. Any CATH domain that contains at least one catalytic residue is characterized as a catalytic domain. Not all of the protein structures may be catalytic, and therefore certain domains might be classified as catalytic while others are classified as binding or noncatalytic [40].

Differences and similarities between enzymes and antibodies

Due to the similarity in specificity between enzyme and antibody proteins in binding small molecular substrates, coenzymes, or haptens, the connection between enzyme and antibody proteins has long been of formal interest [42]. Antibodies are secreted proteins of vertebrates that bind specifically to foreign molecules and protect organisms by discriminating between non-self and self-molecules. Mammalian antibodies are synthesized by cells from the adaptive immunity called lymphocytes. Structurally, antibodies, such as IgGs are large proteins (~150,000 daltons) that are made up of four polypeptide chains: two identical heavy chains and two identical light chains [43, 44]. In natural bivalent antibodies, each polypeptide chain has a constant region, which does not vary significantly among antibodies, and a variable region, which is specific to each particular antibody. To achieve selective recognition, a range of weak bonding interactions are involved; including hydrogen bonds, van der Waals, and electrostatic contacts, as well as solvent interactions [45]. In vertebrates, antibodies are produced by B-lymphocytes that use genetic recombination to generate the diversity of antibody molecules. The antibodies not only recognize the molecular segments of certain foreign substances, but also all of the possible myriad of biological structures [46]. It is estimated that approximately 108 distinct germline antibodies are synthesized as early responses to the challenge of antibody recognition. The genes for each antibody are assembled from the V, D, J, and C gene segments (V variable, J joining, D diversity, and C constant segments) [47]. The segments of each gene can be taken from any one of several genes, and insertion or deletion of segments can occur during recombination of the segments, resulting in the generation of vast numbers of antibody sequences [47, 48]. The variable region of one antibody is comprised of around the first 110 amino acids of both the heavy and light chains. The basic fold of the variable region is an eight-stranded β-barrel with six hypervariable loops that serve as the antigen-binding site (three from each of the light- and heavy-chain variable domains). Each of these loop segments, referred to as hypervariable segments, has a significant degree of sequence variability, and it serves as the foundation for the diversity of the antibody molecule [43, 46, 47]. Upon recognition, a germline cell is selected to produce the specific antibody. Then, more structural diversity can be created by an affinity maturation process. Somatic mutations are introduced across the variable region of a germline antibody and can create up to a million-fold sequence variation. All these processes provide the precise adjustment of antibody-ligand specificity and affinity [47].

The immune system's combinatorial and mutational processes are interestingly comparable to those that occur during the natural development of enzymes [49]. Both enzymes and antibodies interact with tiny molecules in a powerful, reversible manner, that are essential for the transformation of substrates into products, or for the activation of the immune system [26]. Immunization with a transition-state analog can result in the production of antibodies that function like enzymes [50]. Structurally, enzymes are extremely complicated compounds in terms of their tertiary and quaternary structures. Although some are small, with only a single domain on a single chain (e.g. dihydrofolate reductase, which has a molecular mass of 18 kDa), others are massive (e.g. plant ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase, 540 kDa) [51,52,53].

Enzymes catalyze biological transformations with exceptional selectivity and efficiency using a small number of functional groups [54,55,56,57]. Although enzymes employ a broad variety of different protein scaffolds [58, 59], Nature does not appear to have adopted the immunoglobulin domain to build their active sites. The major difference between enzymes and antibodies is not only structural but also in the time interval required for the generation of their diversity. The immunological response that leads to the generation of antibodies takes place over weeks, whereas the process for enzyme origination takes place over millions of years (Table 2). Antibodies and enzymes use the same set of chemical interactions to bind their respective ligands and stabilize transition states, as their active sites are similar in size and structure [60]. However, the basic distinction between enzymes and antibodies is that the former selectively bind transition states, whereas the latter bind ground states [61]. The selective use of binding energy to stabilize transition states or destabilize ground states was crucial for the evolution of the catalytic function [62, 63].

Differences and similarities between enzymes and antibodies.

| Feature | Enzymes | Antibodies |

|---|---|---|

| Structural domains | Multidomain structure | Immunoglobulin |

| Recognition site | Catalytic cleft (critical residues) | 1CDRs (atomic level) |

| Selective binding | Transition states | Grounds states |

| Mechanisms for diversity generation | Exon shuffling, point mutations | V-D-J-rearrangement and somatic mutations |

| Mechanism of evolution | Natural selection | Clonal selection |

| Time-interval for diversity | 101–108 years | weeks |

| Main function | Catalysis | Recognition |

| Conformational flexibility | Can adapt to substrate | A broad range of changes |

- 1

Complementarity determining region (CDR)

Antibodies can be more specific for their ligands than enzymes are for their substrates. Antibodies bind antigens with association constants ranging from 104 to 1014 M−1 [3]. Based on crystallographic studies, antibody combining sites have shown the very restricted nature of intrinsic antibody-antigen interactions. The antibody combining site is made up of six hypervariable “loops” or bends in the polypeptide chain that is entirely exposed to solvent at the molecule's distal end [64], covering an extensive surface of 600 to 800 A2 [65]. It has been calculated that only 47 of the total hypervariable residues are possibly interacting at the combining site of the six loops, which comprise of around 80 total amino acid residues [44, 65, 66]. The residues on the antibody combining site form “contacts”, a contact is a location of physically near juxtaposition between antibody and antigen atoms or ions.

Enzymes undertake the binding, production, and degradation of many substances. The active site of the enzymes generally forms a groove, which is frequently buried in the enzyme and contains a very limited number of amino acids that are involved in binding the substrate (and/or cofactor), being essential for the enzyme's catalytic activity [67]. Antibodies, on the other hand, do not perform complex chemical activities. Instead, they operate as signaling molecules, activating effector systems when they come into contact with an antigen. However, if the secreted antibody targets an enzyme inhibitor, essential for the invading pathogen or tumor development, then recognition and killing are connected inside the antibody molecule. For example, antibodies used to treat cancer may recognize surface bound enzymes that can neutralize enzyme activity and signaling in tumor cells, leading to apoptosis. In this case, the antibody's contribution to immune defense extends well beyond simple signaling [68].

Another common issue of enzymes and antibodies is conformational flexibility (Table 2). The protein conformation of substrate-bound enzymes allows water to be excluded from its active site. As the reaction coordinate is traversed, the catalyst can adapt to changes in the substrate. On the other hand, antibodies exhibit a broad range of conformational changes in response to antigens; including changes in side-chain rotamers, segmental movement of hypervariable loops, and changes in the relative arrangement of the VH and VL domains [44, 69, 70].

Antibodies against enzymes induced by synthetic antigens

The ability of an antigen to react specifically with the functional binding site of a specific antibody is known as its antigenic reactivity or antigenicity. Antigenicity is a property shared by enzymes and other proteins. Our understanding of protein antigenicity has improved considerably in recent years by the knowledge of the three-dimensional structure of the antigen, mainly through the X-ray crystallographic analysis of protein-antibody complexes [71]. The use of peptides as antigens for the generation of antibodies can be challenging as the isolated peptides not always maintain the 3D structure of the corresponding intact protein. The identification of the key residues involved in the antigen-antibody complexes can be used to identify residues that are critical for the function of the antibody in general, and for antigen recognition in particular, and may guide antibody engineering [72].

The portion of a protein antigen that is recognized by an antibody molecule is known as the “epitope” of the protein [73]. Epitopes are usually classified as either continuous or discontinuous, depending on whether or not the amino acid residues at the epitope are contiguous in the sequence of the polypeptide chain [72, 74].

The majority of epitopes in proteins are discontinuous epitopes, made up of residues that are not necessarily contiguous in the sequence, but are brought into spatial proximity by the folding of the polypeptide chain [75].

The initial step toward the generation of antibodies against a single restricted area of a macromolecule is to discover antigenic epitopes on this molecule [76]. Synthetic peptides can be used as immunogens capable of inducing antibodies with the desired specificity against continuous epitopes [77]. The peptide approach has been crucial for the molecular dissection of protein antigens. This is of particular relevance for the development of peptide-based vaccines [78]. A peptide is often preferable to a protein as an antigen; such as when producing antibodies for a specific protein isoform, phosphorylated/glycosylated proteins, and proteins that are difficult to purify, such as large membrane proteins [79]. Most common purpose for raising antibodies against a peptide fragment is to obtain a reagent that will also react strongly and specifically with the complete protein. Peptide antigens are frequently used to produce polyclonal antibodies (mostly of the IgG subclass) in goats or rabbits that target specific epitopes. Particularly in protein families with high similarity [80]. The use of peptides as antigens can also improve the degree of steric complementarity between antigens and antibodies following structure-based rational design [81]. For example, instead of using the whole enzyme as antigen, antibodies can now be generated to recognize the natural conformation of a certain region of the molecule; such as the active site of enzymes or regulatory regions [18, 82]. An antibody of this type might be useful as a model for the investigation of variables that contribute to the catalytic activity of enzymes [22].

Currently, many peptide sequences can be produced at low-cost, and high purity. Using bioinformatics tools, it is also possible to predict antigenic epitopes and minimize the risk of selecting a peptide sequence that does not elicit a strong immune response [83, 84]. The knowledge of the 3D structure of the enzymes can help to identify regions that elicit inhibitory antibodies that could help to understand key aspects of the structure and function of enzyme catalysis [85, 86].

Types of antibodies

The type of antibody is of particular relevance for enzyme inhibition (Table 3). Polyclonal antibodies consist of a heterogeneous mixture of antibodies that are generated from the immune response of numerous B-cells, each of them recognizing a distinct epitope on the same antigen. However, monoclonal antibodies, consisting of identical antibody molecules from a single clone of cells, exhibit a lower batch-to-batch variability [87]. Recombinant antibodies, on the other hand, have several advantages over monoclonal antibodies and polyclonal antibodies. These recombinant antibodies are generated in vitro using synthetic genes, and the production method does not require the use of any animals [88]. Using recombinant technology, it is possible to generate Chimeric antibodies made up of domains from different species, such as mouse and human [89,90,91].

Advantages and limitations of different types of antibodies used as enzyme inhibitors.

| Type of antibody | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Polyclonal | Multiple epitopes | batch-to-batch variability |

| large quantities | low repeatability | |

| Low cost | bioethical restrictions | |

| Possible use of phylogenetically distant species | Large size | |

| May cross-react with other proteins | ||

| Monoclonal | single epitope | High cost |

| less likely to cross-react with other proteins | limited production | |

| long-term production | ||

| Recombinant | Reduced production time | Requires advanced technical skills |

| Animal-free production | Costly to design and manufacture. | |

| Improved reproducibility and control | ||

| Chimeric | Fc-Dependent effector-functions can be modulated | Requires advanced technical skills |

| Half-life and glycosylation can be changed. | Costly to design and manufacture. | |

| Modifications must be validated in preclinical development and clinical trials. |

Polyclonal antibodies

There are several issues of concern with the generation of polyclonal antibodies for enzyme inhibition; such as the isotype or class of the immunoglobulin, the animal of choice, the relative size of molecules involved, the desired amount of antibodies, etc. [92]. One of the potential limitations of the use of antisera for specific enzyme inhibition is the low repeatability of the tests, which could be due to the differences among the batches of antibodies obtained from different animals [87]. The choice of animal to make polyclonal antibodies is also determined by the amount of antibody needed. When large quantities of antisera are needed, horses and goats are often used [93]. However, bioethical restrictions should be considered for the use of these animals. One exception is the use of laying hens to obtain such antibodies. Hens can concentrate antibodies, called IgY, in the yolk of the eggs and, therefore, bleeding of the animals would not be necessary. Purification of IgY antibodies from eggs is also a relatively simple and cheap method, that can be scalable industrially [94, 95].

In the choice of antibodies as enzyme inhibitors, it is also important to consider the optimal extent of the immune response induced against the enzyme. Generally, antibodies obtained from distant vertebrates, to the species of the antigen used, produce a greater immune response, and the antibodies obtained often exhibit better recognition (Table 3). For example, given the greater phylogenetic distance between mammals and birds, immunization of chickens to obtain IgY antibodies against mammalian proteins is often a good option in case a strong immune response is desired [96].

The size of the antibodies is another factor to be considered in enzyme inhibition. The size of the inhibitor molecule determines its ability to bind to different regions or clefts of the enzyme; such as catalytic sites, active or allosteric centers, or regulators. In this situation, it could be advantageous to obtain antibodies of reduced size by immunizing animals such as llamas, camels, or sharks, which have a form of miniature antibodies, called “nanobodies”. These types of mini-antibodies are very useful. For example, to determine the crystal structure of the proteins, nanobodies could fit better into crevices on molecules [97, 98]. Camel heavy-chain antibodies can be useful to interact with active sites of enzymes, such as lysozyme, and mimic carbohydrate substrates, offering advantages over classic antibodies in the design, production, and application of clinically valuable compounds [22].

Monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies were first created in mice. Monoclonal antibodies are derived from a single B cell clone. Thus, they bind to a single epitope. Antibody producing-B-cells are immortalized by fusing them with a parental tumor cell line. These hybridoma cells enable the long-term production of identical monoclonal antibodies [99]. Compared to polyclonal antibodies, monoclonal antibodies detect a specific epitope on the antigen, and they are less likely to cross-react with other proteins. Despite mice being still commonly employed for the production of monoclonal antibodies, they can be generated in other mammals (such as rabbits), or other vertebrates [99, 100]. As opposed to polyclonals, large-scale manufacturing of monoclonal antibodies does not need animals, and the specificity and repeatability from batch to batch is higher. Monoclonal antibody development, on the other hand, can be more expensive than polyclonals [88, 99, 100].

The shark is another intriguing and surprising animal employed in the manufacture of single-domain antibodies. Shark blood contains a high concentration of urea, which aids in their survival in the aquatic environment. Urea, however, denatures proteins if they are not sufficiently stable and led scientists to believe that shark antibodies are particularly stable. Sharks also generate a heavy chain-only antibody, named IgNAR, with lower size, greater stability, and solubility than other Ig isotypes [101].

Recombinant antibodies

The development of phage display libraries was a significant advancement in the monoclonal antibody production technique [102, 103]. Unlike monoclonal antibodies derived from hybridoma, the production of recombinant monoclonal antibodies is accomplished by cloning a library of Fab regions into a bacteriophage plasmid vector. Fab stands for the antigen-binding fragment, a portion of an antibody that binds to antigens. It is made up of one constant domain and one variable domain for each of the heavy and light chains, respectively. The Fab fragment is an antibody structure that still binds to antigens but is monovalent with no Fc portion. Infecting bacteria with Fab-modified bacteriophage vectors results in the production of virus particles with capsid proteins including viral proteins and the Fab fragment, useful in the production of recombinant antibodies [104]. The use of synthetic genes to create recombinant monoclonal antibodies in vitro allows the precise introduction of encoding sequences for optimal binding and repeatability. When the library is completed, the affinity between the different Fab regions in the library may be tested in vitro, and those bacteria transformed with the plasmid can be sequenced [105,106,107]. This approach has several advantages, including:

A single phage library can produce a great number of novel antibodies.

Animal immunization procedures are not required.

It is possible to test a wide range of antigens, including hazardous antigens.

Several issues with hybridoma culture; such as gene loss, gene alterations, and cell-line drift, can be avoided, providing high batch-to-batch consistency.

The time required to obtain recombinant antibodies is reduced, compared to classical antibody manufacturing processes.

In addition to full-length antibodies, recombinant antibodies can be made in several formats; such as chimeric antibodies, Fab fragments, fusion proteins comprising the variable regions of the heavy and light chains of an antibody, named single-chain variable fragments (scFvs), and bispecific antibodies, which are able to bind two different targets or two distinct epitopes on the same target. In addition, they may be produced in several expression systems, including bacteria, insect cells, yeast, and mammalian cells, among others [105]. Recombinant scFvs have been used as conformation-sensor antibodies for phosphatase drug development to enhance insulin signaling in a reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent manner [108].

Chimeric antibodies

Chimeric antibodies are created by fusing variable portions from one species, such as a mouse, with constant areas from another species, for example human. Chimerization of antibodies is often required when producing monoclonal antibodies for therapeutic applications to minimize immunogenicity and to enhance serum half-life. Chimeric antibodies may be obtained through genetic engineering by connecting the immunoglobulin (Ig) variable sections of a chosen mouse hybridoma to the constant regions of a human Ig. This is the first step toward the so-called “humanization of antibodies”. Using this technique, it is also possible to change the constant areas from one species to another, as well as from one subtype of Ig to another, within the same species [89,90,91]. For example, the mouse PM-1 monoclonal antibody to human interleukin 6 receptors, was reshaped to create a human PM-1 antibody consisting of human light chain and heavy chain variable regions that could be useful in human multiple myeloma patients [109].

Impact of antibodies on enzyme activity

The interaction between enzymes with their particular antibodies typically results in a decrease in enzymatic activity. The antibody inhibits the enzyme completely in some circumstances, partially in others, and not at all in a few situations. Several exceptions to this phenomenon have been documented, including antibodies that can occasionally enhance or stabilize the enzyme's activity. For example, specific antibodies can re-activate the beta galactosidase enzyme made defective by a missense point mutation, a phenomenon described as antibody-mediated enzyme formation (AMEF) [110]. The solubility state of the enzymes seems to play a significant role. Some antibodies, effective against enzymes in solution, may have significantly lesser inhibitory effects against their insolubilized forms[42].

Mechanisms of enzyme inhibition by antibodies

Enzyme inhibition by antibodies can proceed by several mechanisms (Table 4). In every case, however, the antibody's impact is determined by its specificity, e.g. the areas of the enzyme to which it is directed. Thus, the extent to which an enzyme can be inhibited or enhanced by an antibody is determined by the type and distribution of the different antigenic determinants on the enzyme molecule [111]. Antibodies can be directed against the catalytic active site and/or the prosthetic group of enzymes, which might be quite similar or identical across enzymes with the same activity from different species. In this case, antibodies that react with the catalytic region of one species’ enzyme may cross-react with the catalytic site of homologous enzymes [112, 113]. For example, rabbit antibodies against bovine hepatic L-glutamic dehydrogenase inhibited not only the bovine glutamic dehydrogenase but also glutamic dehydrogenases from the livers of rats, rabbits, humans, pigeons, and frogs, as well as frog renal and muscle glutamic dehydrogenases. However, this antibody did not affect the activity of yeast glutamic dehydrogenase, which differs from mammalian glutamic dehydrogenase in that it does not require cofactors [114]. In other cases, polyclonal antibodies raised against calf and Drosophila type-II casein kinase bind to both the alpha and beta subunits of the homologous enzyme, and cross-reacted with both subunits of the heterologous enzyme [115].

Examples of different mechanisms of enzyme inhibition by antibodies.

| Mechanism of inhibition | Enzyme | Substrate | Type of antibody | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steric hindrance | Neuraminidase | Sialic acid | Monoclonal | 115 |

| Aggregation | Ribonuclease | RNA | Polyclonal | 116 |

| Allosteric | Dihydrofolate reductase | NADPH | Nanobody | 117 |

| Exo-site targeting | β-Secretase (BACE1) | Amyloid precursor protein (APP) | Recombinant | 81 |

| Combined mode | Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MM9) | Extracellular matrix proteins | Humanized | 118 |

One aspect that distinguishes the inhibition of the majority of enzymes by their respective antibodies is the existence of residual catalytic activity (Fig. 1). Particularly with low molecular weight substrates, catalytic activity is not affected by the addition of more antibody [18]. This circumstance can be interpreted in at least two ways. One explanation is that the antibody partially inhibits each enzyme molecule, while retaining some residual activity. Alternatively, in the case of polyclonal antibodies, the antibody population may be inherently diverse, containing species with varied inhibitory capabilities [18] (Table 4). The validity of this second premise was proved by physically separating antibodies into fractions with varied inhibitory capabilities using several enzyme systems [19]. Although inhibitor antibodies can obviously operate as a competitive inhibitor kinetically, their apparent competitive inhibition must be viewed only as a combination of antibodies to the enzyme active site. As a result, kinetic investigations between enzymes and antibodies are unlikely to reveal the identification and properties of the catalytic and antibody combining site [18, 19]. The inhibition of enzymes by antibodies occurs via the following mechanisms.

Kinetic of the interaction between enzyme and antibody showing a decrease in enzymatic activity with increasing concentration of antibody. The residual catalytic activity of the enzyme is typically found in excess of antibodies.

Steric hindrance at the active site

Antibodies that bind to the active site of enzymes, or immediately adjacent to the active site, are anticipated to compete with the substrate for that site, inhibiting the enzyme's activity via steric hindrance [18] (Fig. 2). Active site-directed antibodies that sterically block the access of substrate use their complementarity determining region (CDR) loops to insert into the cleft to occupy import substrate-binding sites [18]. For a constant amount of enzyme, a plot of enzyme activity as a function of the amount of antibody typically shows a linear decrease at first; then a deviation from linearity, and finally in excess of antibody, a residual level of activity (Fig. 1). This residual activity is not influenced by the addition of a further amount of antibody [18]. At this point, the reaction may become irreversible, and the enzyme may only operate on the substrate through catalytic sites that could not be blocked by the antibody [18].

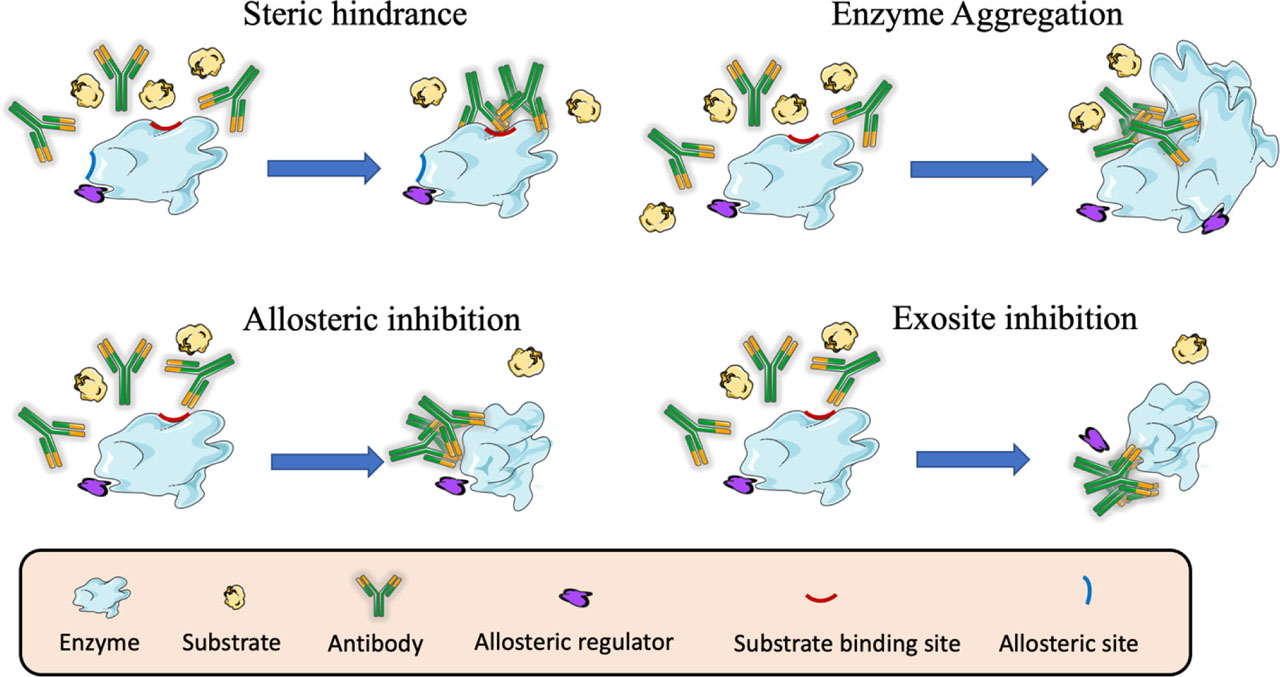

Different mechanisms of enzyme inhibition by antibodies.

In the enzyme inhibition by steric hindrance, antibodies targeting the active site of the enzyme block the access of the substrate and the development of the catalytic reaction. In enzyme aggregation the complex formed between enzymes and antibodies may block the access of the substrate to the catalytic site of the enzyme. In allosteric inhibition, antibodies targeting epitopes distant from the active site of the enzyme can induce conformational changes that prevent the correct access of the substrate and the development of the catalytic reaction. In exosite inhibition, antibodies can bind to an exosite and displace the binding of an allosteric regulator that is essential for the catalytic reaction.

For example, the neuraminidase (NA) enzymatic activity was inhibited by antibodies through steric hindrance, blocking the access to sialic acids [116]. Generally, the degree of inhibition by competitive inhibitors is determined by the relative concentrations of enzyme and substrate, whereas the inhibition by noncompetitive inhibitors is solely determined by the inhibitor's concentration [120, 121]. However, these notions were based on inhibitors and substrates with similar molecular weights, but much smaller than the enzyme molecule. When the inhibitor molecule is the same size or as larger than the enzyme, the inhibitor can combine with the enzyme across a broad region of the catalytic site. Despite this, small substrates might still find some access to active sites even when surfaces are bound by antibodies, and consequently the amount of inhibition by antibodies is related to the substrate size; the bigger the substrate, the greater the extent of inhibition [67].

Inducing aggregation that interferes with substrate access to the catalytic site

The antibody-induced aggregation of enzymes can contribute to steric hindrance by interfering with substrate access to the catalytic site (Fig. 2). For example, W.Y. Lee and H. Sehon, in 1971 demonstrated the presence of soluble ribonuclease-antibody complexes on the enzymatic activity of RNase. After adding sheep anti-r-s-RNase antibodies to a solution of r-s-RNase, the remaining enzymatic activity in the supernatant was attributed to soluble antigen-antibody complexes. Because of their capacity to react selectively with the enzyme, they concluded that bound antibodies represent effective inhibitors of the enzyme activity [117].

The impact of enzyme inhibition is not always attributable to the formation of antigen-antibody aggregates, as monovalent antibody fragments incapable of aggregation have a comparable dependence on substrate size on the amount of inhibition [122].

Induction of conformational changes that modify the enzymatic activity

Antibodies may also inhibit the enzyme indirectly by binding at a “regulatory site” distant from the active site, where antibody interaction results in a conformational change of the enzyme (Fig. 2). In these instances, the antibody-enzyme interaction might result in either suppression or augmentation of the enzymatic activity. Allosteric sites, as opposed to active sites, are typically less conserved and can be exploited to obtain specificity [123]. Excellent examples of selective and powerful allosteric inhibitors have been documented in the literature. For example, the interaction of the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) with the nanobody 216 resulted in conformational changes that modified the active site and its interaction with NADPH [118]. In another instance, the monoclonal antibody, AB0023, allosterically inhibited the enzyme lysyl oxidase–like-2 (LOXL2) by binding to a region remote from its catalytic domain. This antibody inhibits the enzymatic function of LOXL2 in a non-competitive manner, regardless of substrate concentration, and might be useful as therapeutics for oncological and fibrotic diseases [124].

The precise knowledge of enzyme 3-D structures and the location of antibody epitopes allowed the molecular dissection of the allosteric inhibitory mechanism of some antibodies, such as the phage display-derived antibody Ab40 [125]. This antibody was a potent inhibitor of the trypsin-like protease hepatocyte growth factor activator (HGFA), as it bounds to an epitope distant from the active site. Particularly, the structure of the Fab40/HGFA complex showed the existence of conformational changes, essential for the formation of a functional channel between the antibody epitope and the enzyme active site, thus defining a competitive inhibition mechanism that is allosteric in nature [125]. In enzymes with buried active sites, X-ray structures revealed that the substrate must navigate through a series of tunnels to access the active site. These tunnels may act as filters able to influence both substrate specificity and catalytic activity. Understanding tunnels and how they work adds another dimension to our knowledge of enzymatic activities and paves the way for innovative techniques of interfering with or modifying enzyme function [126].

Targeting regulatory sites that regulate the enzymatic activity

Many enzymes have secondary binding sites (exosites) that are located outside of the active site and contribute to substrate affinity by favoring productive interactions between enzyme and substrate (Fig. 2). This is related to allosteric sites but differs in that an enzyme's exosite modulate the reactivity of some enzymes by providing initial binding sites for substrates, inhibitors or cofactors, sterically hindering other interactions, and by allosterically modifying the active site. Ligands that bind to exosites inhibit enzyme activity, but not by blocking the binding of substrates. Instead, they change the shape of the active site. An example of this situation is provided by the aspartyl protease beta-APP cleaving enzyme (BACE), an enzyme involved in the production of Aβ plaque in Alzheimer′s disease. Recent exploration of BACE1 inhibition by peptides and antibodies has revealed exosites that can regulate enzymatic activity [82]. This exosite lies on the opposite side (apical) of the C-terminal transmembrane domain and is one of the most accessible areas of the BACE1 surface to antibodies. Antibodies targeting BACE1 exosite can change the enzyme conformation along the substrate-binding groove, reducing the catalytic efficiency toward its substrate, amyloid precursor protein (APP) [82].

Combined mode of action

Some antibody-enzyme complexes may display more than one mechanism of inhibition. For example, the humanized monoclonal antibody GS-5745 inhibits Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) preventing activation of the secreted zymogen by two mechanisms: binding to a position distal to the active site, and as an allosteric inhibitor, inducing conformational changes [119].

In the system of bromelain and its specific antibody from rabbit sera, the caseinolytic activity was almost completely inhibited by anti-bromelain antibodies. However, when a small molecular weight substrate, such as α-N-benzoyl-L-arginine ethyl ester was used, the residual activity of the antigen-antibody complex was much higher than for the casein substrate. It seems to be due to different steric hindrances depending on the molecular size of the substrates [127].

Therapeutic applications of antibodies as enzyme inhibitors

Compared to small molecules and peptides, antibodies as therapeutic agents can provide superior potency, selectivity, pharmacokinetic properties, and occasionally, a unique mechanism of action [128]. The use of antibody engineering to improve the properties of antibodies has advanced greatly in the last decades, offering novel formats with enhanced attributes for therapeutic and research purposes. Technologies, such as transgenic mice and phage display, facilitated the advancement from murine antibodies to humanized and fully humanized antibodies. Without being comprehensive, we here mention some of the following applications of anti-enzymes antibodies in disease (Table 5). For the enzyme-related diseases, we have followed the classification developed at the Institute of Biochemistry and Bioinformatics of the Technical University of Braunschweig (Germany), known as BRENDA enzyme database (https://www.brenda-enzymes.org) [129].

Diseases that could be treated by anti-enzyme inhibiting antibodies following the classification developed at the Institute of Biochemistry and Bioinformatics of the Technical University of Braunschweig (Germany).

| Disease/Disorder | Enzyme | Therapeutic action of the antibody | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neoplasms | Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) | Inhibits tumor cell invasion and angiogenesis | [129] |

| Carbonic anhydrase 12 | Inhibits spheroid growth of lung adenocarcinoma cells | [130] | |

| Quiescin sulfhydryl oxidase 1 (QSOX1) | Participates in ECM composition and architecture in cell migration | [131] | |

| CD39 ATPase | Activates an immune-mediated anti-tumor response | [132] | |

| CD73 ectonucleotidase | Retards tumor growth and reduces spontaneous lung metastases | [133] | |

| Alzheimer disease | Aspartyl protease β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) | Decreases amyloid-β peptide concentration in the central nervous system of mice and monkeys | [134] |

| Calpain II | Distinguishes different functional states of human brain calpain II | [135] | |

| Hereditary angioedema (HA) | Plasma kallikrein (pKal) | pKal inhibitor with in vivo efficacy for prophylactic treatment of HA | [136] |

| Hemophilia A | Activated protein C (APC) | Inhibits APC anticoagulant activity preventing thrombin production | [137] |

| Adenocarcinoma | Human adamalysin 19 (hADAM19)/meltrin | Localize the hADAM19 in tissues and clarify its pathological role | [138] |

| Influenza | Neuraminidase (NA) of A(H7N9) | Prevents viral cell-to-cell transmission in culture cells. Therapeutic potential | [139] |

| Arthritis | Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 2 (IDO2) | Decreased autoreactive T and B cell activation in preclinical models of arthritis | [140] |

Neoplasm

Neoplasia refers to a tumor that has grown as a result of aberrant cell or tissue development. Neoplasia encompasses a variety of different forms of tumors; including noncancerous or benign tumors, precancerous tumors, in-situ carcinoma, and malignant or cancerous tumors. Several enzymes are expressed on human tumors, and their activity could be inhibited by anti-enzyme antibodies. For example, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are substantially up-regulated in a variety of human cancers [119]. Overexpression of MMPs correlates with tumor stage, invasion, and metastasis in human malignancies. The membrane-associated pericellular protease MT1-MMP is involved in tumor cell invasion and angiogenesis. Human scFv antibodies against MT1 targeting the hemopexin outside the catalytic domain could be useful as diagnostic or therapeutic agents for cancer management [130].

The carbonic anhydrase 12 (CA12) is highly expressed in many human cancers. This enzyme is considered a poor prognostic marker and an attractive target for cancer therapy. A novel humanized CA12-specific antibody blocked CA12 enzymatic activity. In vitro, this antibody significantly inhibited the growth of A549-cells from lung adenocarcinoma. This antibody could be useful for the treatment of CA12-positive tumors [131].

Quiescin sulfhydryl oxidase 1 (QSOX1) is a disulfide bond-forming enzyme that is secreted by fibroblasts and overexpressed in adenocarcinomas and other malignancies. QSOX1 is necessary for the incorporation of certain laminin isoforms into the extracellular matrix (ECM) of cultured fibroblasts and, as a result, for tumor cells to adhere to and penetrate the ECM. Given the known role of laminins in integrin-mediated cell survival and motility, inhibiting QSOX1 activity may provide a novel strategy for combating metastatic disease. A recombinant scFv antibody was able to inhibit human QSOX1 and may be a useful tool for studying the role of ECM composition and architecture in cell migration. This antibody could be further developed for possible therapeutic uses based on its modulatory activity on tumor microenvironment [132].

The tumor microenvironment (TME), which has emerged as an essential immune-regulatory route, is high in the expression of the CD39 leukocyte antigen. Directly inhibiting the enzymatic function of CD39 with an antibody has the potential to activate an immune-mediated anti-tumor response through two mechanisms: 1) increasing the availability of immunostimulatory extracellular ATP released by damaged and/or dying cells, and 2) decreasing the generation and accumulation of suppressive adenosine within the TME.

TTX-030, a fully human anti-CD39 antibody is a strong allosteric inhibitor with sub-nanomolar efficacy that inhibits CD39 ATPase enzymatic activity. TTX-030 is now undergoing clinical trials for cancer treatment [133].

Carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) is a membrane-tethered, hypoxia-induced enzyme, that is significantly expressed in several forms of cancers. It catalyzes the reversible CO2 hydration to HCO3 and H+. CAIX has been hypothesized to contribute to cancer development toward more aggressive types of the disease. Antibody fragments (Fab) produced by phage-display against human CAIX demonstrated inhibitory efficacy on CAIX catalytic activity. These antibody-inhibitors can be used in experiments to investigate the role of CAIX, and for therapy by targeting a catalytically active cancer-related protein [142].

Adenosine is a powerful immunosuppressant that accumulates in the extracellular space during tumor development. CD73 is a dimeric ectonucleotidase that catalyzes the dephosphorylation of adenosine monophosphates to adenosine. CD73 is overexpressed on breast cancer cells and is a powerful inhibitor of the immune response. Inhibition of CD73 promotes migration and invasion of B16F10 melanoma cells in vitro but impairs angiogenesis and development of melanoma cells in vivo [134]. As a result, CD73 has gained considerable interest as a potential target for cancer treatment. Inhibiting CD73 activity in the tumor microenvironment may aid in tumor elimination and it is a potential strategy for cancer treatment. Biparatopic antibodies to CD73, which are able to bind two distinct epitopes, can be used to inhibit its enzymatic activity. Anti-CD73 monoclonal antibody treatment substantially retarded initial tumor growth in immune-competent animals and reduced spontaneous lung metastases. Epitope mapping, structural, and mechanistic investigations indicated that the biparatopic antibody MEDI9447 inhibits CD73 by dual mechanisms of inter-CD73 dimer crosslinking and/or steric hindrance, preventing CD73 from adopting a catalytically active conformation [119, 143].

Hereditary angioedema

Angioedema is a severe, often disfiguring, transient swelling of a specific body region. It is most frequently associated with allergic reactions to external substances and situations. The inherited version of the disease referred to as hereditary angioedema (HAE), is an autosomal dominant condition that affects around 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 150,000 individuals. This kind of angioedema is caused by a hereditary deficit of the C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) or an acquired deficiency of C1-INH. Plasma kallikrein (pKal) catalyzes the proteolytic cleavage of high molecular weight kininogen to produce bradykinin, a powerful vasodilator, and pro-inflammatory peptide. In healthy individuals, the serpin C1-inhibitor strictly regulates pKal activity, whereas patients with hereditary angioedema (HAE) lack the C1-inhibitor, resulting in increased bradykinin production and severe, and possibly deadly, swelling episodes. An antibody developed by phage display against pKal potently inhibits active pKal, but does not target either the zymogen (prekallikrein) or any other serine protease. As a highly specific pKal inhibitor with in vivo efficacy, this antibody was proposed for an effective prophylactic treatment for pKal-mediated diseases, such as HAE [137].

Hemophilia A

Hemophilia A is a genetic disease characterized by a deficit or absence of clotting factor VIII (FVIII), which is inherited in an X-linked recessive manner. In endothelial cells, coagulation is tightly controlled by the protein C (PC) pathway. During coagulation, thrombin cleaves PC zymogen to its active enzyme in complex with thrombomodulin and PC-receptor. Activated protein C (APC) is a plasma serine protease that acts as an anticoagulant by degrading activated factor V and FVIII, and preventing the production of thrombin. Therefore, the inhibition of APC to increase thrombin production may be used for the treatment of bleeding diseases in which hemostasis is dysregulated. The APC anticoagulant activity was selectively inhibited by type II-antibodies without affecting its cytoprotective role, providing improved hemophilia therapy as revealed in a monkey hemophilia A model [138].

Alzheimer disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, with age being the major risk factor. Amyloid precursor protein (APP) is a central therapeutic strategy for treating Alzheimer's disease. As the main β-secretase in the brain, aspartyl protease β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) is a promising option for AD treatments. However, the existence of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) limits the delivery of biotherapeutics to the brain. Anti-BACE1 antibodies decrease amyloid-β peptide concentration in the central nervous system of mice and monkeys, consistent with detectable antibody absorption across the BBB. Thus, passive immunization with anti-BACE1 may be targeted as a potential strategy for treating Alzheimer's disease [135]. However, the efficacy of anti-BACE1 therapy will be dependent on increasing antibody absorption into the brain [144].

With no clinical data to support or refute the amyloid theory, new approaches to addressing potential targets are required. Calpains are a family of calcium-dependent cysteine proteases that are tightly regulated at the cellular level. Calpains activate or modify the regulation of certain enzymes, including important protein kinases and phosphatases, and cause-specific cytoskeletal rearrangements. To investigate the role of calpain II in human neurodegenerative disease, rabbit polyclonal antisera were raised to peptide sequences comprising the active site region of the catalytic domain in the 76-kDa subunit of calpain II. This antiserum distinguished different functional states of human brain calpain II and are promising tools for exploring the mechanisms by which these proteases contribute to the development of Alzheimer's pathology [136].

Influenza

Influenza viruses are a danger to worldwide public health; including humans, farm animals, and wild species. Influenza viruses can occasionally cross the species barrier, posing a risk for a worldwide pandemic. To date, there is no vaccine to prevent influenza A (H7N9) infection. The use of monoclonal antibodies to suppress influenza virus infection is a newly emerging approach. The prophylactic treatment with a murine monoclonal antibody (3c10-3) against the NA of A(H7N9), completely protected mice from lethal challenge with wild-type A/Anhui/1/2013 (H7N9), indicating the therapeutic potential of this antibody. Epitope mapping showed that 3c10-3 binds to the active site of neuraminidase (NA) enzyme, and functional analysis demonstrated that 3c10-3 reduces NA enzyme activity and prevents viral cell-to-cell transmission in culture cells. These findings imply that 3c10-3 has the potential to be used as a therapy in the treatment of A(H7N9) infections, either as an alternative to or in conjunction with existing NA antiviral inhibitors [140].

Adenocarcinoma

The ADAMs (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase) are a fascinating family of transmembrane and secreted proteins with important roles in regulating cell phenotype via their effects on cell adhesion, migration, proteolysis, and signaling. Members of the adamalysin have been shown to participate in processes critical for tumorigenesis and cancer progression, including ECM remodeling. Human adamalysin 19 (hADAM19)/meltrin is an active metalloproteinase and is a novel disintegrin antigen marker for dendritic cells. Polyclonal antibodies to hADAM19 peptide antigens could be useful to localize the hADAM19 protein selectively in tissues and cells and to clarify its biological and pathological activities, such as pro-growth factor processing [139].

Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease for which there is no cure. The immunomodulatory enzyme indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 2 (IDO2) is a critical mediator of the autoreactive B and T cell responses that contribute to rheumatoid arthritis (RA). However, therapeutically targeting IDO2 has been difficult due to the lack of small compounds that selectively inhibit IDO2, without affecting the closely related IDO1. In preclinical models of arthritis, it was possible to reduce the impact of hereditary IDO2 impairment by decreasing autoreactive T and B cell activation [141].

Conclusions

Antibodies are one of the most important macromolecules for life science research and are frequently used in several biomedical areas; including biotechnology, medicine, immunotherapy, and diagnostics. Enzymes and antibodies share basic similarities at the level of binding specificity and the strength of interaction. Because enzymes catalyze the majority of chemical processes in living organisms, enzyme inhibitors with therapeutic potential are being sought by scientists all over the world. Antibodies against enzymes impair their catalytic activity through steric hindrance, aggregation, and/or conformational alterations. Their mechanism of action varies depending on the enzyme and, in most cases, leads to the neutralization of enzyme activity. These processes are not mutually exclusive; they may coexist with their relative significance often depending on the size of the substrate. The development of anti-enzymes inhibiting antibodies could serve as tools for the study of biochemical and immunochemical dynamics of enzymes, the design of pharmaceutical drugs, insecticides, pesticides, or chemical weapons.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by projects APOGEO (Cooperation Program INTERREG-MAC 2014–2020, with European Funds for Regional Development-FEDER, “Agencia Canaria de Investigación, Innovación y Sociedad de la Información (ACIISI) del Gobierno de Canarias” (project ProID2020010134), CajaCanarias (project 2019SP43); AMdlN. also acknowledges contract (IMMUNOWINE) financed by Cabildo de Tenerife, Program TF INNOVA 2016–21 (with MEDI & FDCAN Funds). Currently, AMdlN is a recipient of a Marie Curie fellowship under grant agreement 101030604 (IGYMERA).

Conflict of interest:

Authors state no conflict of interest

Data availability statements:

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

1 Chattopadhyay K, Lazar-Molnar E, Yan Q, Rubinstein R, Zhan C, Vigdorovich V, et al. Sequence, structure, function, immunity: structural genomics of costimulation. Immunol Rev. 2009 May;229(1):356–86.10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00778.xSearch in Google Scholar

2 Du X, Li Y, Xia YL, Ai SM, Liang J, Sang P, et al. Insights into protein–ligand interactions: mechanisms, models, and methods. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Jan;17(2):144.10.3390/ijms17020144Search in Google Scholar

3 Kricka L. Molecular and ionic recognition by biological systems. Chemical sensors. Springer; 1988. pp. 3–14.10.1007/978-94-010-9154-1_1Search in Google Scholar

4 Szwajkajzer D, Carey J. Molecular and biological constraints on ligand-binding affinity and specificity. Biopolymers. 1997;44(2):181–98.10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1997)44:2<181::AID-BIP5>3.0.CO;2-RSearch in Google Scholar

5 Böhm HJ, Klebe G. What can we learn from molecular recognition in protein–ligand complexes for the design of new drugs? Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1996;35(22):2588–614.10.1002/anie.199625881Search in Google Scholar

6 Schreiber G, Keating AE. Protein binding specificity versus promiscuity. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011 Feb;21(1):50–61.10.1016/j.sbi.2010.10.002Search in Google Scholar

7 Seong SY, Matzinger P. Hydrophobicity: an ancient damage-associated molecular pattern that initiates innate immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004 Jun;4(6):469–78.10.1038/nri1372Search in Google Scholar

8 Mäntsälä P, Niemi J. Enzymes: the biological catalysts of life. Physiol Maintanance. 2009;2:1–22.Search in Google Scholar

9 Villa J, Warshel A. Energetics and dynamics of enzymatic reactions. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105(33):7887–907.10.1021/jp011048hSearch in Google Scholar

10 Sujitha P, Kavitha S, Shakilanishi S, Babu NK, Shanthi C. Enzymatic dehairing: A comprehensive review on the mechanistic aspects with emphasis on enzyme specificity. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018 Oct;118 Pt A:168–79.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.06.081Search in Google Scholar

11 Callender R, Dyer RB. The dynamical nature of enzymatic catalysis. Acc Chem Res. 2015 Feb;48(2):407–13.10.1021/ar5002928Search in Google Scholar

12 Kovermann M, Grundström C, Sauer-Eriksson AE, Sauer UH, Wolf-Watz M. Structural basis for ligand binding to an enzyme by a conformational selection pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017 Jun;114(24):6298–303.10.1073/pnas.1700919114Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13 Raso V, Stollar BD. The antibody-enzyme analogy. Comparison of enzymes and antibodies specific for phosphopyridoxyltyrosine. Biochemistry. 1975 Feb;14(3):591–9.10.1021/bi00674a020Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14 Carter PJ, Lazar GA. Next generation antibody drugs: pursuit of the ‘high-hanging fruit’. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018 Mar;17(3):197–223.10.1038/nrd.2017.227Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15 Elgundi Z, Reslan M, Cruz E, Sifniotis V, Kayser V. The state-of-play and future of antibody therapeutics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017 Dec;122:2–19.10.1016/j.addr.2016.11.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16 Tiller KE, Tessier PM. Advances in antibody design. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2015;17(1):191–216.10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071114-040733Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17 Roguin LP, Retegui LA. Monoclonal antibodies inducing conformational changes on the antigen molecule. Scand J Immunol. 2003 Oct;58(4):387–94.10.1046/j.1365-3083.2003.01320.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

18 Cinader B. Antibodies against enzymes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1957;11(1):371–90.10.1146/annurev.mi.11.100157.002103Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19 Arnon R. Enzyme inhibition by antibodies. Acta Endocrinol Suppl (Copenh). 1975;194 2_Suppl:133–53.10.1530/acta.0.080S133Search in Google Scholar

20 Graus F, Saiz A, Dalmau J. GAD antibodies in neurological disorders - insights and challenges. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020 Jul;16(7):353–65.10.1038/s41582-020-0359-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

21 Laureano AF, Zani MB, Sant’Ana AM, Tognato RC, Lombello CB, do Nascimento MH, et al. Generation of recombinant antibodies against human tissue kallikrein 7 to treat skin diseases. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2020 Dec;30(23):127626.10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127626Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22 Wang J, Lozier J, Johnson G, Kirshner S, Verthelyi D, Pariser A, et al. Neutralizing antibodies to therapeutic enzymes: considerations for testing, prevention and treatment. Nat Biotechnol. 2008 Aug;26(8):901–8.10.1038/nbt.1484Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23 Bigger BW, Saif M, Linthorst GE. The role of antibodies in enzyme treatments and therapeutic strategies. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Mar;29(2):183–94.10.1016/j.beem.2015.01.006Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24 Ogert RA, Gentry MK, Richardson EC, Deal CD, Abramson SN, Alving CR, et al. Studies on the topography of the catalytic site of acetylcholinesterase using polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies. J Neurochem. 1990 Sep;55(3):756–63.10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04556.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

25 Brennan C, Christianson K, Surowy T, Mandecki W. Modulation of enzyme activity by antibody binding to an alkaline phosphatase-epitope hybrid protein. Protein Eng. 1994 Apr;7(4):509–14.10.1093/protein/7.4.509Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26 Petrella RU. Iwamoto M, Yokoyama MM. Enzyme-Inhibiting Antibodies and Immunoglobulin Combining Site Functional Perspectives. Kurume Med J. 1991;37:209–28.10.2739/kurumemedj.37.209Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27 Sellergren B. Molecularly imprinted polymers: shaping enzyme inhibitors. Nat Chem. 2010 Jan;2(1):7–8.10.1038/nchem.496Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28 Copeland RA, Harpel MR, Tummino PJ. Targeting enzyme inhibitors in drug discovery. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007 Jul;11(7):967–78.10.1517/14728222.11.7.967Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29 Thapa S, Lv M, Xu H. Acetylcholinesterase: a primary target for drugs and insecticides. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2017;17(17):1665–76.10.2174/1389557517666170120153930Search in Google Scholar PubMed

30 Mosolov VV, Valueva TA. [Proteinase inhibitors in plant biotechnology: a review]. Prikl Biokhim Mikrobiol. 2008 May–Jun;44(3):261–9.10.1134/S0003683808030010Search in Google Scholar

31 Manivasagan P, Venkatesan J, Sivakumar K, Kim SK. Actinobacterial enzyme inhibitors—a review. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2015 Jun;41(2):261–72.10.3109/1040841X.2013.837425Search in Google Scholar PubMed

32 Holliday GL, Fischer JD, Mitchell JB, Thornton JM. Characterizing the complexity of enzymes on the basis of their mechanisms and structures with a bio-computational analysis. FEBS J. 2011 Oct;278(20):3835–45.10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08190.xSearch in Google Scholar

33 Cannon WR, Singleton SF, Benkovic SJ. A perspective on biological catalysis. Nat Struct Biol. 1996 Oct;3(10):821–33.10.1038/nsb1096-821Search in Google Scholar

34 Benkovic SJ, Hammes-Schiffer S. A perspective on enzyme catalysis. Science. 2003 Aug;301(5637):1196–202.10.1126/science.1085515Search in Google Scholar

35 Toscano MD, Woycechowsky KJ, Hilvert D. Minimalist active-site redesign: teaching old enzymes new tricks. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46(18):3212–36.10.1002/anie.200604205Search in Google Scholar

36 Broderick JB. Coenzymes and cofactors. e LS 2001.10.1038/npg.els.0000631Search in Google Scholar

37 Bartlett GJ, Porter CT, Borkakoti N, Thornton JM. Analysis of catalytic residues in enzyme active sites. J Mol Biol. 2002 Nov;324(1):105–21.10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01036-7Search in Google Scholar

38 Tipton K, Boyce S. History of the enzyme nomenclature system. Bioinformatics. 2000 Jan;16(1):34–40.10.1093/bioinformatics/16.1.34Search in Google Scholar PubMed

39 Csaba G, Birzele F, Zimmer R. Systematic comparison of SCOP and CATH: a new gold standard for protein structure analysis. BMC Struct Biol. 2009 Apr;9(1):23.10.1186/1472-6807-9-23Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40 Mitchell JB. Enzyme function and its evolution. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017 Dec;47:151–6.10.1016/j.sbi.2017.10.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41 Sillitoe I, Dawson N, Thornton J, Orengo C. The history of the CATH structural classification of protein domains. Biochimie. 2015 Dec;119:209–17.10.1016/j.biochi.2015.08.004Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42 Paul S, Nishiyama Y, Planque S, Karle S, Taguchi H, Hanson C, et al. Antibodies as defensive enzymes. Springer seminars in immunopathology. Springer; 2005. pp. 485–503.10.1007/s00281-004-0191-1Search in Google Scholar

43 Davies DR, Metzger H. Structural basis of antibody function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1983;1(1):87–117.10.1146/annurev.iy.01.040183.000511Search in Google Scholar

44 Chiu ML, Goulet DR, Teplyakov A, Gilliland GL. Antibody structure and function: the basis for engineering therapeutics. Antibodies (Basel). 2019 Dec;8(4):55.10.3390/antib8040055Search in Google Scholar

45 Braden BC, Goldman ER, Mariuzza RA, Poljak RJ. Anatomy of an antibody molecule: structure, kinetics, thermodynamics and mutational studies of the antilysozyme antibody D1.3. Immunol Rev. 1998 Jun;163(1):45–57.10.1111/j.1600-065X.1998.tb01187.xSearch in Google Scholar

46 Rose DR. The generation of antibody diversity. Am J Hematol. 1982 Aug;13(1):91–9.10.1002/ajh.2830130111Search in Google Scholar

47 Wysocki LJ, Gefter ML. Gene conversion and the generation of antibody diversity. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58(1):509–31.10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002453Search in Google Scholar

48 Kim S, Davis M, Sinn E, Patten P, Hood L. Antibody diversity: somatic hypermutation of rearranged VH genes. Cell. 1981 Dec;27(3 Pt 2):573–81.10.1016/0092-8674(81)90399-8Search in Google Scholar

49 Singer SJ, Doolittle RF. Antibody active sites and immunoglobulin molecules. Science. 1966 Jul;153(3731):13–25.10.1126/science.153.3731.13Search in Google Scholar PubMed

50 Mader MM, Bartlett PA. Binding energy and catalysis: the implications for transition-state analogs and catalytic antibodies. Chem Rev. 1997 Aug;97(5):1281–302.10.1021/cr960435ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

51 Ward RD. Relationship between enzyme heterozygosity and quaternary structure. Biochem Genet. 1977 Feb;15(1–2):123–35.10.1007/BF00484555Search in Google Scholar PubMed

52 MacBeath G, Kast P, Hilvert D. Probing enzyme quaternary structure by combinatorial mutagenesis and selection. Protein Sci. 1998 Aug;7(8):1757–67.10.1002/pro.5560070810Search in Google Scholar

53 Friedrich P. Supramolecular enzyme organization: quaternary structure and beyond. Elsevier; 2014.Search in Google Scholar

54 Arnold FH, Wintrode PL, Miyazaki K, Gershenson A. How enzymes adapt: lessons from directed evolution. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001 Feb;26(2):100–6.10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01755-2Search in Google Scholar

55 Galperin MY, Walker DR, Koonin EV. Analogous enzymes: independent inventions in enzyme evolution. Genome Res. 1998 Aug;8(8):779–90.10.1101/gr.8.8.779Search in Google Scholar PubMed

56 Kaplan NO, Ciotti MM, Hamolsky M, Bieber RE. Molecular heterogeneity and evolution of enzymes. Science. 1960 Feb;131(3398):392–7.10.1126/science.131.3398.392Search in Google Scholar PubMed

57 Bunzel HA, Anderson JL, Mulholland AJ. Designing better enzymes: insights from directed evolution. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2021 Apr;67:212–8.10.1016/j.sbi.2020.12.015Search in Google Scholar PubMed

58 Buljan M, Bateman A. The evolution of protein domain families. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009 Aug;37(Pt 4):751–5.10.1042/BST0370751Search in Google Scholar PubMed

59 Cannon JP. Plasticity of the immunoglobulin domain in the evolution of immunity. Integr Comp Biol. 2009 Aug;49(2):187–96.10.1093/icb/icp018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

60 Tramontano A, Ammann AA, Lerner RA. Antibody catalysis approaching the activity of enzymes. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110(7):2282–6.10.1021/ja00215a045Search in Google Scholar

61 Lerner RA, Benkovic SJ, Schultz PG. At the crossroads of chemistry and immunology: catalytic antibodies. Science. 1991 May;252(5006):659–67.10.1126/science.2024118Search in Google Scholar PubMed

62 Kraut J. How do enzymes work? Science. 1988 Oct;242(4878):533–40.10.1126/science.3051385Search in Google Scholar PubMed

63 Arnon R. Immunochemistry of enzymes. The antigens: Elsevier, 1973:87–159.10.1016/B978-0-12-635501-7.50008-3Search in Google Scholar

64 Kabat, E. A., Te Wu, T., Perry, H. M., Foeller, C., & Gottesman, K. S. (1992). Sequences of proteins of immunological interest. DIANE publishing.Search in Google Scholar

65 Sundberg EJ, Mariuzza RA. Molecular recognition in antibody-antigen complexes. Adv Protein Chem. 2002;61:119–60.10.1016/S0065-3233(02)61004-6Search in Google Scholar

66 Novotný J, Bruccoleri R, Newell J, Murphy D, Haber E, Karplus M. Molecular anatomy of the antibody binding site. J Biol Chem. 1983 Dec;258(23):14433–7.10.1016/S0021-9258(17)43880-4Search in Google Scholar

67 Laskowski RA, Luscombe NM, Swindells MB, Thornton JM. Protein clefts in molecular recognition and function. Protein science: a publication of the Protein Society 1996;5:2438.Search in Google Scholar

68 Lu LL, Suscovich TJ, Fortune SM, Alter G. Beyond binding: antibody effector functions in infectious diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018 Jan;18(1):46–61.10.1038/nri.2017.106Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

69 Dondelinger M, Filée P, Sauvage E, Quinting B, Muyldermans S, Galleni M, et al. Understanding the significance and implications of antibody numbering and antigen-binding surface/residue definition. Front Immunol. 2018 Oct;9:2278.10.3389/fimmu.2018.02278Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

70 Yang D, Kroe-Barrett R, Singh S, Roberts CJ, Laue TM. IgG cooperativity–Is there allostery? Implications for antibody functions and therapeutic antibody development. MAbs. Taylor & Francis; 2017. pp. 1231–52.10.1080/19420862.2017.1367074Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

71 Van Regenmortel MH. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of synthetic peptides. Biologicals. 2001 Sep–Dec;29(3–4):209–13.10.1006/biol.2001.0308Search in Google Scholar PubMed

72 Braden BC, Poljak RJ. Structural features of the reactions between antibodies and protein antigens. FASEB J. 1995 Jan;9(1):9–16.10.1096/fasebj.9.1.7821765Search in Google Scholar PubMed

73 Van Regenmortel MH. What is a B-cell epitope? Epitope Mapping Protocols. Springer; 2009. pp. 3–20.10.1007/978-1-59745-450-6_1Search in Google Scholar PubMed

74 Kringelum JV, Nielsen M, Padkjær SB, Lund O. Structural analysis of B-cell epitopes in antibody:protein complexes. Mol Immunol. 2013 Jan;53(1–2):24–34.10.1016/j.molimm.2012.06.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

75 Haste Andersen P, Nielsen M, Lund O. Prediction of residues in discontinuous B-cell epitopes using protein 3D structures. Protein Sci. 2006 Nov;15(11):2558–67.10.1110/ps.062405906Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

76 Caoili SEC. Benchmarking B-cell epitope prediction for the design of peptide-based vaccines: problems and prospects. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology 2010;910524.10.1155/2010/910524Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

77 Sanchez-Trincado JL, Gomez-Perosanz M, Reche PA. Fundamentals and methods for T-and B-cell epitope prediction. Journal of immunology research 2017;2680160.10.1155/2017/2680160Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

78 Ahmad TA, Eweida AE, Sheweita SA. B-cell epitope mapping for the design of vaccines and effective diagnostics. Trials Vaccinol. 2016;5:71–83.10.1016/j.trivac.2016.04.003Search in Google Scholar

79 Li W, Joshi MD, Singhania S, Ramsey KH, Murthy AK. Peptide vaccine: progress and challenges. Vaccines (Basel). 2014 Jul;2(3):515–36.10.3390/vaccines2030515Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

80 Trier N, Hansen P, Houen G. Peptides, antibodies, peptide antibodies and more. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Dec;20(24):6289.10.3390/ijms20246289Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

81 Peczuh MW, Hamilton AD. Peptide and protein recognition by designed molecules. Chem Rev. 2000 Jul;100(7):2479–94.10.1021/cr9900026Search in Google Scholar PubMed

82 Wang W, Liu Y, Lazarus RA. Allosteric inhibition of BACE1 by an exosite-binding antibody. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013 Dec;23(6):797–805.10.1016/j.sbi.2013.08.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

83 Yang X, Yu X. An introduction to epitope prediction methods and software. Rev Med Virol. 2009 Mar;19(2):77–96.10.1002/rmv.602Search in Google Scholar PubMed

84 Tong JC, Tan TW, Ranganathan S. Methods and protocols for prediction of immunogenic epitopes. Brief Bioinform. 2007 Mar;8(2):96–108.10.1093/bib/bbl038Search in Google Scholar PubMed

85 Soria-Guerra RE, Nieto-Gomez R, Govea-Alonso DO, Rosales-Mendoza S. An overview of bioinformatics tools for epitope prediction: implications on vaccine development. J Biomed Inform. 2015 Feb;53:405–14.10.1016/j.jbi.2014.11.003Search in Google Scholar

86 Backert L, Kohlbacher O. Immunoinformatics and epitope prediction in the age of genomic medicine. Genome Med. 2015 Nov;7(1):119.10.1186/s13073-015-0245-0Search in Google Scholar

87 Hjelm B, Forsström B, Löfblom J, Rockberg J, Uhlén M. Parallel immunizations of rabbits using the same antigen yield antibodies with similar, but not identical, epitopes. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e45817.10.1371/journal.pone.0045817Search in Google Scholar

88 Gray A, Bradbury AR, Knappik A, Plückthun A, Borrebaeck CA, Dübel S. Animal-free alternatives and the antibody iceberg. Nat Biotechnol. 2020 Nov;38(11):1234–9.10.1038/s41587-020-0687-9Search in Google Scholar

89 Billetta R, Lobuglio AF. Chimeric antibodies. Int Rev Immunol. 1993;10(2–3):165–76.10.3109/08830189309061693Search in Google Scholar

90 Roque AC, Lowe CR, Taipa MÂ. Antibodies and genetically engineered related molecules: production and purification. Biotechnol Prog. 2004 May–Jun;20(3):639–54.10.1021/bp030070kSearch in Google Scholar

91 van Dijk MA, van de Winkel JG. Human antibodies as next generation therapeutics. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2001 Aug;5(4):368–74.10.1016/S1367-5931(00)00216-7Search in Google Scholar

92 Lauwereys M, Arbabi Ghahroudi M, Desmyter A, Kinne J, Hölzer W, De Genst E, et al. Potent enzyme inhibitors derived from dromedary heavy-chain antibodies. EMBO J. 1998 Jul;17(13):3512–20.10.1093/emboj/17.13.3512Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

93 Leenaars M, Hendriksen CF. Critical steps in the production of polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies: evaluation and recommendations. ILAR J. 2005;46(3):269–79.10.1093/ilar.46.3.269Search in Google Scholar PubMed

94 Schade R, Calzado EG, Sarmiento R, Chacana PA, Porankiewicz-Asplund J, Terzolo HR. Chicken egg yolk antibodies (IgY-technology): a review of progress in production and use in research and human and veterinary medicine. Altern Lab Anim. 2005 Apr;33(2):129–54.10.1177/026119290503300208Search in Google Scholar PubMed

95 Amro WA, Al-Qaisi W, Al-Razem F. Production and purification of IgY antibodies from chicken egg yolk. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2018 Jun;16(1):99–103.10.1016/j.jgeb.2017.10.003Search in Google Scholar

96 Larsson A, Sjöquist J. Chicken IgY: utilizing the evolutionary difference. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;13(4):199–201.10.1016/0147-9571(90)90088-BSearch in Google Scholar