Abstract

In important areas like medical malpractice and environmental torts, injurers are potentially insolvent and courts may make errors in determining liability (e.g. due to hindsight bias). We show that proportional liability, which holds a negligent injurer liable for harm discounted with the probability that the harm was caused by the injurer’s negligence, is less susceptible to these imperfections and therefore socially preferable to all other liability rules currently contemplated by courts. We also provide a result which might be useful to regulators when calculating minimum capital requirements or minimum mandatory insurance for different industries.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Richard R. W. Brooks, Guido Calabresi, E. Donald Elliott, Juan-José Ganuza, Fernando Gomez, Sharon Hannes, Christine Jolls, Douglas Kysar, Jacob Nussim, Nickolas Parillo, Ariel Porat, Susan Rose-Ackerman, Urs Schweizer, and John Witt for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We are also grateful to seminar participants at the American Law and Economics Association Annual Meeting (Princeton, 2010), the European Law and Economics Association Annual Meeting (Paris, 2010), Bar Ilan University, Tel-Aviv University, the University of Bonn, and Yale University. We would also like to thank Yijia Lu, Aileen Nielsen, and Andrew Sternlight for excellent research assistance.

References

Arlen, JenniferH. 1992. “Should Defendants’ Wealth Matter?.” The Journal of Legal Studies.21(2):413–29.10.1086/467912Suche in Google Scholar

Beard, T. R. 1990. “Bankruptcy and Care Choice.” RAND Journal of Economics21(4):626–34.10.2307/2555473Suche in Google Scholar

Ben-Shahar, O. 1999. “Causation and Forseeability.” In Encyclopedia of Law and Economics, edited by B.Bouckaert and G. D.Geest, Vol. 3, 644–88. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.Suche in Google Scholar

Calabresi, G., and J. O.Cooper. 1996. “New Directions in Tort Law.” Valparaiso University Law Review30(3):859–84.Suche in Google Scholar

Cooter, R. 1991. “Economic Theories of Legal Liability.” Journal of Economic Perspectives5/3:11–30.10.1257/jep.5.3.11Suche in Google Scholar

Craswell, R., and J. E.Calfee. 1986. “Deterrence and Uncertain Legal Standards.” Journal of Law, Economics and Organization2(2):279–303.Suche in Google Scholar

Dari-Mattiacci, G. 2004. “Soft Negligence and Cause in Fact: A Comment on Ganuza and Gomez,” George Mason University School of Law Paper 4.10.2139/ssrn.589324Suche in Google Scholar

Ganuza, J., and F.Gomez. 2008. “Realistic Standards: Optimal Negligence with Limited Liability.” Journal of Legal Studies37(2):577–94.10.1086/586718Suche in Google Scholar

Grady, M. F. 1983. “A New Positive Economic Theory of Negligence.” Yale Law Journal92:799–829.10.2307/796145Suche in Google Scholar

Grechenig, K., and A.Stremitzer. 2009. “Der Einwand Rechtmäß Igen Alternativverhaltens – Rechtsvergleich, Ökonomische Analyse Und Implikationen Für Die Proportionalhaftung.” RabelsZ73(2):336–71.10.1628/003372509788213561Suche in Google Scholar

Kahan, M. 1989. “Causation and Incentives to Take Care under the Negligence Rule.” Journal of Legal StudiesXVIII:427–47.10.1086/468154Suche in Google Scholar

Kaplow, L. 1994. “The Value of Accuracy in Adjudication: An Economic Analysis.” Journal of Legal Studies33:307–402.10.1086/467927Suche in Google Scholar

Kornhauser, L. A., and R. L.Revesz. 1990. “Apportioning Damages among Potentially Insolvent Actors.” Journal of Legal StudiesXIX:617–52.10.1086/467864Suche in Google Scholar

Landes, W. 1990. “Insolvency and Joint Torts: A Comment.” Journal of Legal Studies19(2):670–89.10.1086/467866Suche in Google Scholar

Landes, W., and R.Posner. 1983. “Causation in Tort Law: An Economic Approach.” Journal of Legal Studies12(1):109–34.10.1086/467716Suche in Google Scholar

Landes, W., and R.Posner. 1987. The Economic Structure of Tort Law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.10.4159/harvard.9780674864030Suche in Google Scholar

Leshem, S., and G. P.Miller. 2009. “All-or-Nothing Versus Proportionate Damages.” Journal of Legal Studies38:345–82.10.1086/593153Suche in Google Scholar

Mitchell Polinsky, A., and StevenShavell. 1992. “Optimal Cleanup and Liability After Environmentally Harmful Discharges” NBER Working Papers 4176, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.10.3386/w4176Suche in Google Scholar

Rose-Ackerman, S. 1990. “Market-Share Allocations in Tort-Law: Strengths and Weaknesses.” Journal of Legal StudiesXIX:739–46.10.1086/467869Suche in Google Scholar

Rosenberg, D. 1984. “The Causal Connection in Mass Exposure Cases: A ‘Public Law’ Vision of the Tort System.” Harvard Law Review97(4):849–929.10.2307/1341021Suche in Google Scholar

Schweizer, U. 2009. “Legal Damages for Losses of Chances.” International Review of Law and Economics29:153–60.10.1016/j.irle.2008.10.003Suche in Google Scholar

Shavell, S. 1985. “Uncertainty over Causation and the Determination of Civil Liability.” Journal of Law and Economics28(3):587–609.10.1086/467102Suche in Google Scholar

Shavell, S. 1986. “The Judgment Proof Problem.” International Review of Law and Economics6(1):427–47.10.1007/978-94-015-7957-5_17Suche in Google Scholar

Shavell, S. 1987. The Economic Analysis of Accident Law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.10.4159/9780674043510Suche in Google Scholar

Shavell, S. 2004. Foundations of the Economic Analysis of Law. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, Harvard University Press.10.4159/9780674043497Suche in Google Scholar

Stoll, H. 1976. “Haftungsverlagerung Durch Beweisrechtliche Mittel.” Archiv Für Die Civilistische Praxis176:145ff.Suche in Google Scholar

Stremitzer, A., and A. D.Tabbach. 2009. “Insolvency and Biased Standards – The Case for Proportional Liability,” Yale Law & Economics Research Paper No. 397.10.2139/ssrn.1507871Suche in Google Scholar

Tabbach, A. D. 2008. “Causation and Incentives to Choose Levels of Care and Activity under the Negligence Rule.” Review of Law and Economics3:133–52.10.2202/1555-5879.1198Suche in Google Scholar

Wagner, G. 2004. MünchKommBGB-Wagner, Vol. 5, 4th edn, p. §823 Rn 732ff. Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich.Suche in Google Scholar

- 1

Kornhauser and Revesz (1990) point to the problem that the strict liability rule under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act is likely to drive some injurers into bankruptcy.

- 2

Strictly speaking, the probability of causation can be calculated as just described if we rule out the possibility that harm is prevented because the injurer fell short of exercising due care. (See Schweizer 2009, for a rigorous treatment of the application of the causation requirement under uncertainty.) Given this assumption, the causation requirement is equivalent to the rule of proportional liability as proposed by Shavell (1985) and others. This rule exactly internalizes the consequences of deviating from the due care standard.

- 3

In Evers v. Dollinger, 95 N.J. 399 (1984), the Supreme Court held that, in the context of a claim of medical malpractice, when there is evidence that the defendant’s negligence increased the risk of harm to the plaintiff and that the harm was in fact sustained, it becomes a jury question whether or not the increased risk constituted a substantial factor in producing the injury. The Court determined that a less onerous burden of establishing causation should be applied. See also Hake v. Manchester Tp., 98 N.J. 302 (1985); Scafidi v. Seiler, 225 N.J. Super. 576 (App.Div.1988); Battista v. Olson, 213 N.J. Super. 137 (App.Div.1986); Gaido v. Weiser, 227 N.J. Super. 175 (App.Div.1988). Both Dubak v. Burdette Tomlin Memorial Hosp., 233 N.J. Super. 441, 450–452 (App.Div.1989) and Zuchowicz v. United States, 140 F.3d 381 (U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, 1998) contain very insightful discussions of increased risk/substantial factor theory. In King v. Burlington Northern Santa Fe Ry. Co. 277 Neb. 203, 762 N.W.2d 24 Neb., 2009 the Court, suggests that any positive association that could reasonably support a causal inference could be sufficient to send a case to a jury. See also Grechenig and Stremitzer (2009) for a survey of court practice across jurisdictions.

- 4

To the same effect, the German Federal Court (BGH) shifts the burden of proof to the injurer, if it can be established that he acted with gross negligence. He then has to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that his negligence did not cause the harm, which will be impossible for him. See Stoll (1976, 145, 155ff) and Wagner (2004).

- 5

Kahan (1989) discusses the case of uncertain causation and considers an all-or-nothing rule in combination with a preponderance of the evidence standard of proof. We will not analyze such a rule since it does not achieve socially efficient behavior even if the standard of due care is set at the socially optimal care and injurers are solvent (see Kahan 1989, 440–1; Shavell 1987, Proposition 1, 52–3).

- 6

See, for example, Landes and Posner (1983), Rosenberg (1984), and Shavell (1985).

- 7

See, for example, Sindell v. Abbott Laboratories, 26 Cal.3d 588, 607 P.2d 924, 163 Cal.Rptr. 132 (1980).

- 8

This is the case where the harm – for example cancer – can be “caused” by a particular substance, but where it is impossible to pinpoint which particular person’s cancer would have occurred naturally and which would not have occurred but for exposure to the substance (see the famous case In Re “Agent Orange” Product Liability Litigation, 597 F. Supp. 740 (E.D.N.Y. 1984).)

- 9

This is true if we rule out the pathological case that harm can be prevented precisely because the injurer was negligent, like in the case where an accident is prevented because he drove too fast.

- 10

This might be surprising, as one would expect that proportional liability performs better than full liability as the wealth constraint binds more often under full liability than under proportional liability. The reason this is not the case is that both rules cause injurers to pay more than is necessary to induce the efficient care level. As long as the wealth constraint just eats away the slack for deterrence purposes it does not matter. As soon as it starts to matter, it does so for both rules alike.

- 11

This is in the same vein as Ganuza and Gomez (2008) but a completely different effect than the one analyzed in their paper.

- 12

In a recent paper, Leshem and Miller (2009) compare full liability and proportional liability in a model of costly litigation. They recommend full liability on the ground that it leads to higher rates of compliance (conceding that it will also lead to higher rates of litigation and therefore to higher litigation cost). Yet, compliance is only unambiguously welfare increasing if it is assumed that courts set the standard of due care at the socially optimal level. Hence, they implicitly rule out the possibility of systematic court error. As they also assume solvent injurers, the two main ingredients of our model, court error and the judgment-proof problem, are absent from their analysis.

- 13

In the latter case, we assume the effort to take care has an opportunity cost of x. One could interpret non-monetary care as the cost of effort that can be evaluated in monetary terms but does not reduce the wealth constraint. Alternatively, one could think of non-monetary care as an investment that is made in an asset which is subsequently transferred to a limited liability company. The value of the asset would then determine the wealth constraint. The assumption that care is non-monetary is made in (Shavell 1986), the assumption that care is monetary is made in Beard (1990).

- 14

The second-order sufficient condition is satisfied by the convexity of the p(x).

- 15

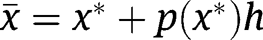

The analysis can be easily extended to the case where care is partially monetary in nature, in which case

. Strictly speaking the minimization problem here and in the rest of the paper is subject to the constraint

. Strictly speaking the minimization problem here and in the rest of the paper is subject to the constraint  . However, as will become evident in Footnote 16, this constraint never binds.

. However, as will become evident in Footnote 16, this constraint never binds. - 16

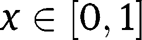

The first-order condition is necessary and sufficient as the probability function is decreasing and convex:

.

.Note that the constraint

is never binding as, for

is never binding as, for  , marginal benefits from care are zero, while marginal costs are strictly positive.

, marginal benefits from care are zero, while marginal costs are strictly positive. - 17

In this paper, acting negligently means exercising less than “due care” as determined by whoever sets the standard, regardless of whether it is determined efficiently.

- 18

Unless

.

. - 19

It is important to note that under a negligence-based full liability regime (or indeed under all negligence regimes) the potential minimizers

,

,  , or

, or  need not be unique. For example, if

need not be unique. For example, if  is set above efficient care level, then there exists such a level for which

is set above efficient care level, then there exists such a level for which  . In such a case, both

. In such a case, both  and

and  are minimizers of the cost function. We will adopt the convention that in such cases, the injurer chooses the care level that is more efficient from a social perspective. This qualification applies to the other negligence-based liability rules.

are minimizers of the cost function. We will adopt the convention that in such cases, the injurer chooses the care level that is more efficient from a social perspective. This qualification applies to the other negligence-based liability rules. - 20

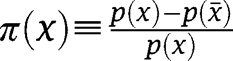

See, for example, Ben-Shahar (1999, 651); Tabbach (2008). The probability of causation can be calculated as in expression [4] if we rule out the possibility that harm is prevented because the injurer fell short of exercising due care (see Footnote 2).

- 21

This is because if the injurer is not wealth-constrained expected costs under threshold liability differ from expected costs under strict liability only by a constant.

- 22

Again the first-order condition is sufficient because of the convexity of the expected cost function.

- 23

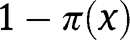

Threshold liability as formulated in this paper can be applied to situations of uncertain causation in the following way. Suppose that in the face of uncertainty over causation the courts or juries would toss an appropriate coin reflecting the probability of causation

and the probability of non-causation

and the probability of non-causation  and would find the injurer liable in the relevant case. We would like to thank Jacob Nussim for offering us this interpretation of threshold liability.

and would find the injurer liable in the relevant case. We would like to thank Jacob Nussim for offering us this interpretation of threshold liability. - 24

Rules in which the probability threshold required to impose liability is

were analyzed, for example, by Shavell (1985) and shown to induce socially non-optimal care even in the absence of wealth constraints. We therefore do not analyze these rules in the present paper.

were analyzed, for example, by Shavell (1985) and shown to induce socially non-optimal care even in the absence of wealth constraints. We therefore do not analyze these rules in the present paper. - 25

See Footnote 2.

- 26

In a previous working paper version of this paper we offer a full fledged analysis regarding the effects of insolvency and biased standards under the different negligence-based liability rules. The interested reader can find this analysis in Stremitzer and Tabbach (2009).

- 27

In so doing, we rule out the possibility that sophisticated courts would fine-tune the standard of due care depending on the liability rule they apply. Allowing for such fine-tuning would increase the range of implementable outcomes under different rules and would probably weaken the case for proportional liability. It is, for instance, a well-known result that full liability converges to strict liability if the standard of due care is set to a very high level, so that no potential injurer would ever adhere to it (see, for example, Landes and Posner 1987). In line with the literature, we rule out the possibility that sophisticated courts would “game” a particular liability rule in this way. We assume that courts aim for setting the due care standard to the level of socially optimal care, but sometimes fail to do so because of systematic biases.

- 28

Guido Calabresi and Jeffrey O. Cooper in the their 1995 Monsanto Lecture, published in the Valparaiso University Law Review, Vol. 30. No. 3, described the advent of splitting rules, replacing the dominance of all-or-nothing recovery rules, as one of the most important shifts in tort law over the past decades comparable only to the coming of insurance 80 years ago. Calabresi and Cooper deplored that while “splitting rules give us more options, we do not necessarily know whether they create a better package of incentives than existed before” (p. 883). They concluded that a much additional analysis is needed to answer this question. By showing that proportional liability as a prominent example of such a splitting rule has desirable welfare properties, our article contributes to the vast research program outlined in their article.

- 29

This last point is similar to Ganuza and Gomez (2008) who have argued that, in the presence of wealth constraints, setting due care below socially optimal care is desirable as a second best. Dari-Mattiacci (2004), however, argued, that this effect does not occur if the causation requirement is taken into account and the precaution technology is such that only the probability of the harm occurring can be affected. Our analysis suggests that the effect of Ganuza and Gomez (2008) also holds in a setting where care reduces the probability of harm if causation is uncertain and proportional liability is applied. The criticism by Dari-Mattiacci (2004) is only valid under threshold liability.

- 30

Note that the wealth constraint is less binding under proportional liability than under strict liability.

- 31

To illustrate, suppose that

is set sufficiently high that no injurer abides by it. Then the superiority of proportional liability to threshold liability depends on whether excessive or insufficient care is induced by these rules. For non-monetary care,

is set sufficiently high that no injurer abides by it. Then the superiority of proportional liability to threshold liability depends on whether excessive or insufficient care is induced by these rules. For non-monetary care,  , implying that proportional liability is superior to threshold liability. For monetary care and certain wealth levels such as

, implying that proportional liability is superior to threshold liability. For monetary care and certain wealth levels such as  ,

,  . In this case, threshold liability is preferable to proportional liability.

. In this case, threshold liability is preferable to proportional liability. - 32

This differs from the argument by Rose-Ackerman (1990) that individualized causal claims should be discouraged in market-share liability cases because they are worthless and therefore only waste resources. See also Kaplow (1994) for the general argument that the benefits of accuracy be weighed against the cost of achieving it.

- 33

Strictly speaking, to induce the socially optimal care, damages should be a little bit higher than

, since otherwise the injurer is indifferent among all

, since otherwise the injurer is indifferent among all  . We shall assume that damages are set in order to induce injurers to take due care.

. We shall assume that damages are set in order to induce injurers to take due care. - 34

For details see Stremitzer and Tabbach (2009).

- 35

With a minor correction for the monetary nature of care, a similar result holds for monetary care.

©2014 by De Gruyter

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Contributions

- Cheap Talk and Editorial Control

- Adverse Effects of Patent Pooling on Product Development and Commercialization

- Discretionary Acquisition of Firm-Specific Human Capital under Non-verifiable Performance

- On-the-Job Search and Finding a Good Job Through Social Contacts

- Replication and Returns to Scale in Production

- An Adaptive Learning Model with Foregone Payoff Information

- A Single Parent’s Labor Supply: Evaluating Different Child Care Fees within an Intertemporal Framework

- Dynamic Price Discrimination with Customer Recognition

- Cournot and Bertrand Competition in a Model of Spatial Price Discrimination with Differentiated Products

- The Impact of Voter Uncertainty and Alienation on Turnout and Candidate Policy Choice

- Topics

- Trust, Truth, Status and Identity: An Experimental Inquiry

- Macro Meets Micro: Stochastic (Calvo) Revisions in Games

- The Robustness Case for Proportional Liability

- The Rise and Spread of Favoritism Practices

- Moral Hazard and Tradeable Pollution Emission Permits

- Reciprocity in the Principal–Multiple Agent Model

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Contributions

- Cheap Talk and Editorial Control

- Adverse Effects of Patent Pooling on Product Development and Commercialization

- Discretionary Acquisition of Firm-Specific Human Capital under Non-verifiable Performance

- On-the-Job Search and Finding a Good Job Through Social Contacts

- Replication and Returns to Scale in Production

- An Adaptive Learning Model with Foregone Payoff Information

- A Single Parent’s Labor Supply: Evaluating Different Child Care Fees within an Intertemporal Framework

- Dynamic Price Discrimination with Customer Recognition

- Cournot and Bertrand Competition in a Model of Spatial Price Discrimination with Differentiated Products

- The Impact of Voter Uncertainty and Alienation on Turnout and Candidate Policy Choice

- Topics

- Trust, Truth, Status and Identity: An Experimental Inquiry

- Macro Meets Micro: Stochastic (Calvo) Revisions in Games

- The Robustness Case for Proportional Liability

- The Rise and Spread of Favoritism Practices

- Moral Hazard and Tradeable Pollution Emission Permits

- Reciprocity in the Principal–Multiple Agent Model