Abstract

In this paper, we develop an overlapping generations model with endogenous fertility and calibrate it to the Swedish historical data in order to estimate the economic cost of the 1918–19 influenza pandemic. The model identifies survivors from younger cohorts as main benefactors of the windfall bequests following the influenza mortality shock. We also show that the general equilibrium effects of the pandemic reveal themselves over the wage channel rather than the interest rate, fertility or labor supply channels. Finally, we demonstrate that the influenza mortality shock becomes persistent, driving the aggregate variables to lower steady states which costs the economy 1.819% of the output loss over the next century.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the editor Tiago Cavalcanti and an anonymous referee for many helpful suggestions that helped to improve the paper. All remaining errors are ours.

Calibration inputs.

| Cohorts | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10–20 | 20–30 | 30–40 | 40–50 | 50–60 | 60–70 | 70–80 | All | |

| Population, male | 582,195 | 458,157 | 358,275 | 274,301 | 223,427 | 155,228 | 106,211 | 2,157,794 |

| Population, female | 544,381 | 468,887 | 403,062 | 320,476 | 303,422 | 229,936 | 200,276 | 2,470,440 |

| LFPR, male | 0.250 | 0.825 | 0.897 | 0.898 | 0.869 | 0.723 | 0.362 | 0.665 |

| LFPR, female | 0.131 | 0.396 | 0.229 | 0.187 | 0.167 | 0.130 | 0.099 | 0.206 |

| Workers, male | 145,612 | 378,122 | 321,521 | 246,576 | 194314 | 112257 | 38499 | 1,436,901 |

| Workers, female | 71,571 | 185,712 | 92,455 | 60,209 | 50,959 | 29,897 | 19,963 | 510,766 |

| Average labor earnings, male, SEK | 1501 | 2394 | 3618 | 4122 | 4136 | 3541 | 3207 | 3220 |

| Average labor earnings, female, SEK | 1172 | 1560 | 2023 | 2323 | 2549 | 2972 | 3015 | 1917 |

| Per capita labor earnings, SEK | 268 | 1289 | 1774 | 1944 | 1772 | 1263 | 599 | 1210 |

| Normalized bill | 0.222 | 1.064 | 1.464 | 1.605 | 1.463 | 1.042 | 0.495 | 1 |

-

Data for Population before the pandemic are taken from Karlsson, Nilsson, and Pichler (2014). The number of workers is calculated based on the LFPR taken from Census 1920 (Statistics Sweden 1927). Average labor earnings are taken from Census 1920.

Fertility rates.

| Years | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918 | 1928 | 1938 | 1948 | 1958 | 1968 | 1978 | 1988 | 1998 | 2008 | |

| 10–20 | 8.79 | 8.88 | 13.12 | 19 | 20.93 | 15.865 | 6.78 | 5.36 | 3.21 | 2.572 |

| 20–30 | 115.485 | 87.775 | 116.84 | 130.345 | 140.31 | 122.805 | 106.8 | 109.65 | 78.235 | 80.277 |

| 30–40 | 108.39 | 71.915 | 81.945 | 70.445 | 62.58 | 46.17 | 52.025 | 72.17 | 81.275 | 99.877 |

| 40–50 | 27.46 | 15.355 | 12.54 | 9.16 | 5.81 | 2.675 | 2.52 | 3.645 | 4.855 | 7.311 |

-

Fertility rates per 1,000 women from official sources from (Statistics Sweden 1927, 2009, 2018) aggregated into cohorts.

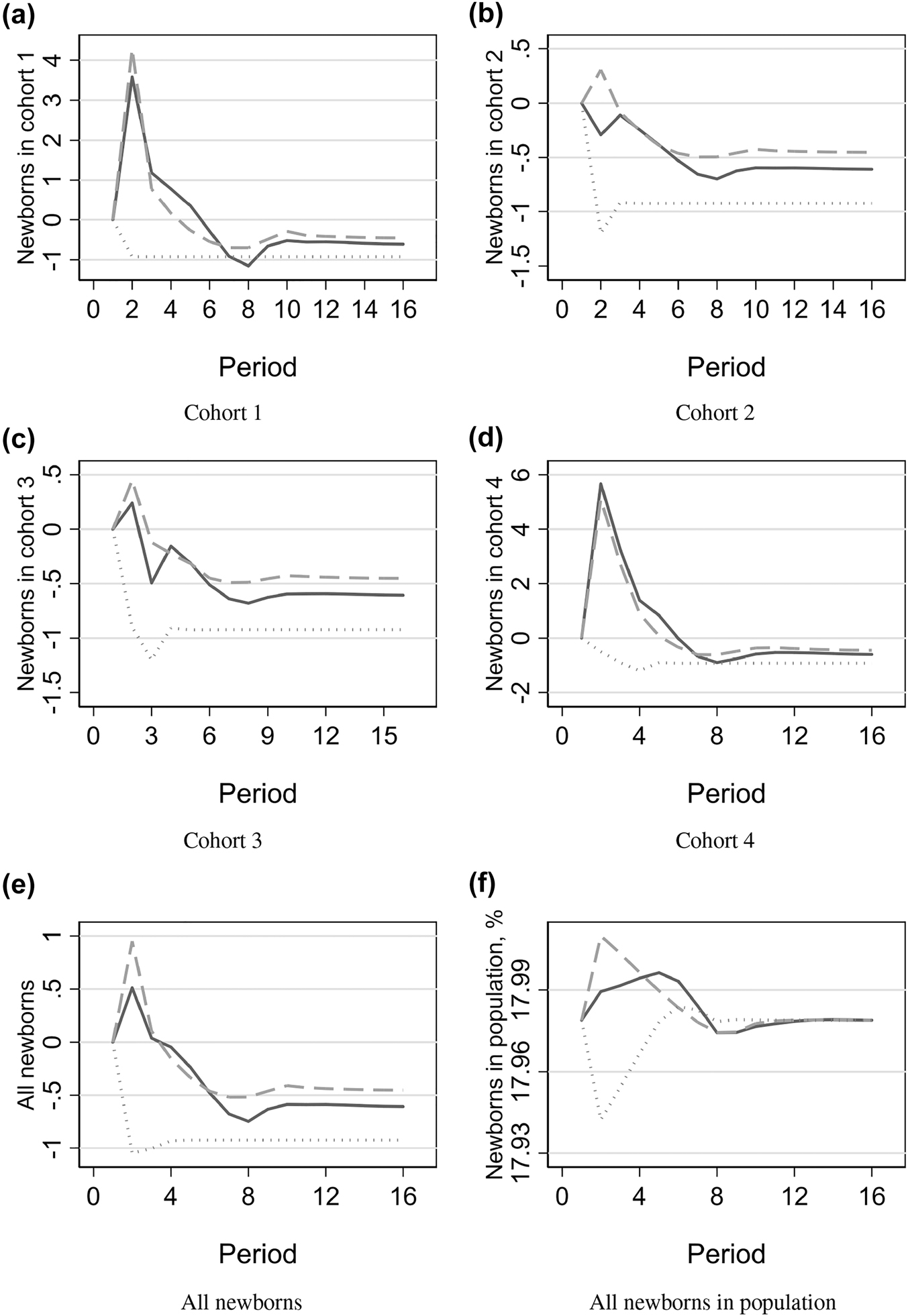

Adjustment in the number of newborns after the flu.

Plots depict percentage deviation from the steady state value. Dashed line shows the counterfactual scenario of uniform mortality across cohorts. Dotted line shows the scenario with constant fertility.

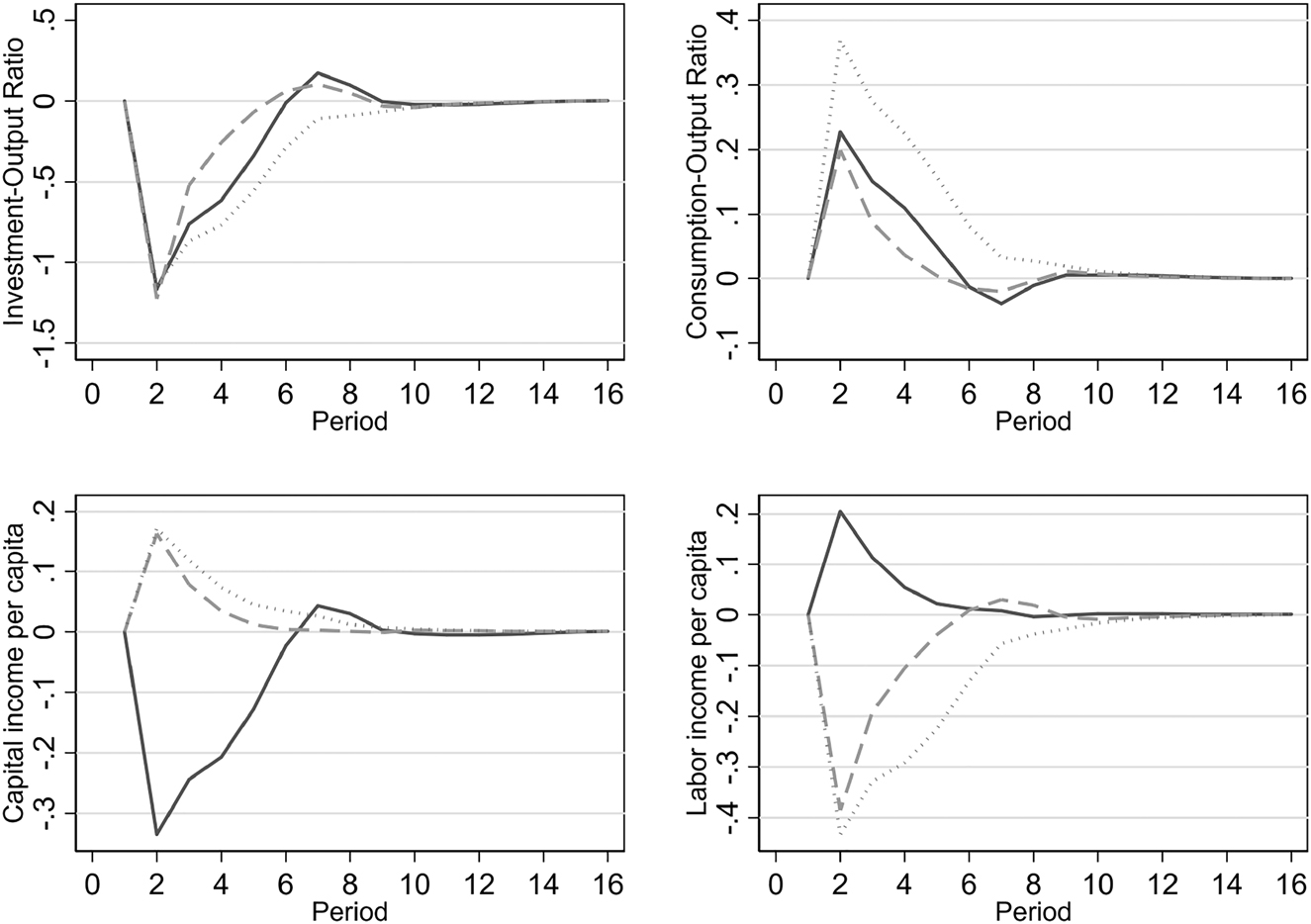

Adjustment of investment-output, consumption-output ratios and factor payments after the flu.

Plots depict percentage deviation from the steady state value. Dashed line shows the counterfactual scenario of uniform mortality across cohorts. Dotted line shows the scenario with constant fertility.

OLG model predictions versus the results in Karlsson, Nilsson, and Pichler (2014).

The round markers represent the effects estimated by Karlsson, Nilsson, and Pichler (2014) and their confidence intervals calculated as the parameter estimate multiplied by the overall mortality rate in the. The diamond markers represent the deviation from the pre-pandemic steady state according to our OLG model.

Decomposition of various effects on per capita output.

References

Acemoglu, D. 2008. Introduction to Modern Economic Growth. Princeton University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Alvaredo, F., B. Garbinti, and T. Piketty. 2017. “On the Share of Inheritance in Aggregate Wealth: Europe and the USA, 1900–2010.” Economica 84 (334): 239–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12233.Suche in Google Scholar

Åman, M. 1990. Spanska Sjukan: Den Svenska Epidemin 1918–1920 Och Dess Internationella Bakgrund. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.Suche in Google Scholar

Andreoni, J. 1990. “Impure Altruism and Donations to Public Goods: A Theory of Warm-Glow Giving.” The Economic Journal 100 (401): 464–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234133.Suche in Google Scholar

Auerbach, A. J., and L. J. Kotlikoff. 1987. Dynamic Fiscal Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Bagchi, S., and J. Feigenbaum. 2014. “Is Smoking a Fiscal Good?” Review of Economic Dynamics 17 (1): 170–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2013.04.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Bell, C., S. Devarajan, and H. Gersbach. 2006. “The Long-Run Economic Costs of AIDS: A Model with an Application to South Africa.” The World Bank Economic Review 20 (1): 55–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhj006.Suche in Google Scholar

Bloom, D. E., D. Canning, and G. Fink. 2014. “Disease and Development Revisited.” Journal of Political Economy 122 (6): 1355–66. https://doi.org/10.1086/677189.Suche in Google Scholar

Bloom, D. E., and A. S. Mahal. 1997. “Does the Aids Epidemic Threaten Economic Growth?” Journal of Econometrics 77 (1): 105–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4076(96)01808-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Boberg-Fazlic, N., M. Ivets, M. Karlsson, and T. Nilsson. 2021. “Disease and Fertility: Evidence from the 1918–19 Influenza Pandemic in Sweden.” Economics and Human Biology 43: 101020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2021.101020.Suche in Google Scholar

Boucekkine, R. 2012. “Epidemics from the Economic Theory Viewpoint.” Mathematical Population Studies 19 (1): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/08898480.2012.640857.Suche in Google Scholar

Boucekkine, R., B. Diene, and T. Azomahou. 2008. “Growth Economics of Epidemics: A Review of the Theory.” Mathematical Population Studies 15 (1): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/08898480701792410.Suche in Google Scholar

Brainerd, E., and M. V. Siegler. 2003. “The Economic Effects of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic.” In WP No. 3791. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.Suche in Google Scholar

Chesnais, J.-C. 1992. The Demographic Transition: Stages, Patterns, and Economic Implications. A Longitudinal Study of Sixty-Seven Countries Covering the Period 1720–1984. Oxford: Clarendon Press.10.1093/oso/9780198286592.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Corrigan, P., G. Glomm, and F. Mendez. 2005. “Aids Crisis and Growth.” Journal of Development Economics 77: 107–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2004.02.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Cuddington, J. T., and J. D. Hancock. 1994. “Assessing the Impact of Aids on the Growth Path of the Malawian Economy.” Journal of Development Economics 43 (2): 363–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(94)90013-2.Suche in Google Scholar

Edvinsson, R. (2005). “Growth, Accumulation, Crisis: With New Macroeconomic Data for Sweden 1800–2000.” Doctoral dissertation.Suche in Google Scholar

Elmér, Å. 1960. “Folkpensioneringen I Sverige.” PhD Thesis. CWK Gleerup.Suche in Google Scholar

Fischer, M., M. Karlsson, T. Nilsson, and N. Schwarz. 2020. “The Long-Term Effects of Long Terms: Compulsory Schooling Reforms in Sweden.” In Technical Report, IFN Working Paper. Journal of the European Economic Association 18 (6): 2776–823. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvz071.Suche in Google Scholar

Gagnon, E., B. K. Johannsen, and D. López-Salido. 2022. “Supply-side Effects of Pandemic Mortality: Insights from an Overlapping-Generations Model.” The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics 1: 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1515/bejm-2020-0196.Suche in Google Scholar

Galor, O., and D. N. Weil. 1996. “The Gender Gap, Fertility, and Growth.” The American Economic Review 86 (3): 374–87.Suche in Google Scholar

Garrett, T. A. 2009. “War and Pestilence as Labor Market Shocks: Us Manufacturing Wage Growth 1914–1919.” Economic Inquiry 47 (4): 711–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.2008.00137.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Hagen, J. 2013. “A History of the Swedish Pension System.” In Working Paper 2013, 7. Uppsala: Uppsala Center for Fiscal Studies.Suche in Google Scholar

Heer, B., and A. Maussner. 2009. Dynamic General Equilibrium Modeling: Computational Methods and Applications. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.10.1007/978-3-540-85685-6Suche in Google Scholar

Holmlund, B. 2013. “Wage and Employment Determination in Volatile Times: Sweden 1913–1939.” Cliometrica 7 (2): 131–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-012-0084-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Huggett, M. 1996. “Wealth Distribution in Life-Cycle Economies.” Journal of Monetary Economics 38 (3): 469–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3932(96)01291-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Jörberg, L., and O. Krantz. 1978. Ekonomisk Och Social Politik I Sverige, 1850–1939. Lund: Ekonomisk-Historiska Institutionen, Lunds Universitet.Suche in Google Scholar

Karlsson, M., D. Kühnle, and N. Prodromidis. 2021. The 1918–1919 Influenza Pandemic in Economic History. Oxford: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance.10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.013.682Suche in Google Scholar

Karlsson, M., T. Nilsson, and S. Pichler. 2014. “The Impact of the 1918 Spanish Flu Epidemic on Economic Performance in Sweden: An Investigation into the Consequences of an Extraordinary Mortality Shock.” Journal of Health Economics 36: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.03.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Keogh-Brown, M. R., R. D. Smith, J. W. Edmunds, and P. Beutels. 2010. “The Macroeconomic Impact of Pandemic Influenza: Estimates from Models of the United Kingdom, France, Belgium and The Netherlands.” The European Journal of Health Economics 11 (6): 543–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-009-0210-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Lee, R. D. 1974. “Forecasting Births in Post-transition Populations: Stochastic Renewal with Serially Correlated Fertility.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 69 (347): 607–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1974.10480177.Suche in Google Scholar

Lorentzen, P., J. McMillan, and R. Wacziarg. 2008. “Death and Development.” Journal of Economic Growth 13 (2): 81–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-008-9029-3.Suche in Google Scholar

Lucas, R. E. 1976. “Econometric Policy Evaluation: A Critique.” In Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, Vol. 1, 19–46. North Holland: Elsevier.10.1016/S0167-2231(76)80003-6Suche in Google Scholar

Maddison, A. 2003. The World Economy: Historical Statistics. Paris: Development Centre of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.10.1787/9789264104143-enSuche in Google Scholar

Magnusson, L. 1996. Sveriges Ekonomiska Historia. Lund: Raben Prisma.Suche in Google Scholar

Mamelund, S.-E. 2004. “Can the Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918 Explain the Baby Boom of 1920 in Neutral Norway?” Population 59 (2): 229–60. https://doi.org/10.3917/pope.402.0229.Suche in Google Scholar

Mamelund, S.-E. 2011. “Geography May Explain Adult Mortality from the 1918–20 Influenza Pandemic.” Epidemics 3 (1): 46–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epidem.2011.02.001.Suche in Google Scholar

Menon, M., K. Pendakur, and F. Perali. 2012. “On the Expenditure-Dependence of Children’s Resource Shares.” Economics Letters 117 (3): 739–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2012.08.012.Suche in Google Scholar

Morens, D. M., and A. S. Fauci. 2007. “The 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Insights for the 21st Century.” The Journal of Infectious Diseases 195 (7): 1018–28. https://doi.org/10.1086/511989.Suche in Google Scholar

Nyström, H. 1994. Hungerupproret 1917. Falun: Zelos.Suche in Google Scholar

Richter, A., and P. O. Robling. 2013. Multigenerational Effects of the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic in Sweden, Vol. 5. Stockholm: Swedish Institute for Social Research.Suche in Google Scholar

Ríos-Rull, J.-V. 2001. “Population Changes and Capital Accumulation: The Aging of the Baby Boom.” The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics 1 (1): 1008. https://doi.org/10.2202/1534-6013.1008.Suche in Google Scholar

Schön, L. 2010. Sweden’s Road to Modernity: An Economic History. Stockholm: SNS förlag.Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, R. D., M. R. Keogh-Brown, and T. Barnett. 2011. “Estimating the Economic Impact of Pandemic Influenza: an Application of the Computable General Equilibrium Model to the UK.” Social Science & Medicine 73 (2): 235–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.025.Suche in Google Scholar

Statistics Sweden 1923. Dödsorsaker. 1918. Stockholm: Statistiska centralbyrån.Suche in Google Scholar

Statistics Sweden 1924. Dödsorsaker. 1919. Stockholm: Statistiska centralbyrån.Suche in Google Scholar

Statistics Sweden 1927. Folkrakningen 1920. Stockholm: Statistiska Centralbyrån.Suche in Google Scholar

Statistics Sweden 1930. Statistisk Årsbok För Sverige 1930. Stockholm: Kungl. Statistiska Centralbyrån.Suche in Google Scholar

Statistics Sweden 1937. Folkräkningen Den 31 December 1930. 6. Stockholm: Hushåll. Skolbildning. Yrkesväxling, Biyrke m.m.Suche in Google Scholar

Statistics Sweden 1999. Befolkningsutvecklingen Under 250 År. Historisk statistik för Sverige 1999.Suche in Google Scholar

Statistics Sweden. 2009. Tabeller Över Sveriges Befolkning 2009. Örebro: SCB-Tryck.Suche in Google Scholar

Statistics Sweden. 2018. Befolkningsstatistik. Örebro: SCB-Tryck.Suche in Google Scholar

Tamura, R. 1996. “From Decay to Growth: A Demographic Transition to Economic Growth.” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 20 (6–7): 1237–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1889(95)00898-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Taubenberger, J. K., and D. M. Morens. 2006. “1918 Influenza: The Mother of All Pandemics.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 12 (1): 15–22. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1209.05-0979.Suche in Google Scholar

Voigtländer, N., and H.-J. Voth. 2013. “The Three Horsemen of Riches: Plague, War, and Urbanization in Early Modern Europe.” The Review of Economic Studies 80 (2): 774–811. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rds034.Suche in Google Scholar

World Bank. 2017. “Drug-resistant Infections: A Threat to Our Economic Future.” The World Bank Documents & Reports 3.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Advances

- The Macroeconomic Impact of the 1918–19 Influenza Pandemic in Sweden

- Aggregate Costs of a Gender Gap in the Access to Business Resources

- The Macroeconomic Effects of Shadow Banking Panics

- Wealth Inequality and the Exploration of Novel Technologies

- Contributions

- Learning, Central Bank Conservatism, and Stock Price Dynamics

- Progressive Taxation and Robust Monetary Policy

- The New Keynesian Phillips Curve and Imperfect Exchange Rate Pass-Through

- The Macroeconomic Impact of Social Unrest

- Interest Rates, Money, and Fed Monetary Policy in a Markov-Switching Bayesian VAR

- Un-Incorporation and Conditional Misallocation: Firm-Level Evidence from Sri Lanka

- Idiosyncratic Shocks, Lumpy Investment and the Monetary Transmission Mechanism

- Open Economy Neoclassical Growth Models and the Role of Life Expectancy

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Advances

- The Macroeconomic Impact of the 1918–19 Influenza Pandemic in Sweden

- Aggregate Costs of a Gender Gap in the Access to Business Resources

- The Macroeconomic Effects of Shadow Banking Panics

- Wealth Inequality and the Exploration of Novel Technologies

- Contributions

- Learning, Central Bank Conservatism, and Stock Price Dynamics

- Progressive Taxation and Robust Monetary Policy

- The New Keynesian Phillips Curve and Imperfect Exchange Rate Pass-Through

- The Macroeconomic Impact of Social Unrest

- Interest Rates, Money, and Fed Monetary Policy in a Markov-Switching Bayesian VAR

- Un-Incorporation and Conditional Misallocation: Firm-Level Evidence from Sri Lanka

- Idiosyncratic Shocks, Lumpy Investment and the Monetary Transmission Mechanism

- Open Economy Neoclassical Growth Models and the Role of Life Expectancy