Abstract

We develop a simple growth model featuring individuals’ choices between general and specific skills, endogenous technological innovation, and a government subsidy for education. The two types of skills differ by their productivity and transferability: general skills are transferable across firms, while each firm-specific skill has a productivity advantage in the firm. Firms face uncertainty in their innovation activities, and the resulting heterogeneity in their labor demand makes the transferability of general skill valuable. We theoretically show that as a country catch up to the world technology frontier, firms invest more in innovation activities. This rises firms’ technological uncertainty and, thus, their demands for general skills increases. As a result, especially in more advanced economies, education subsidies may enhance GDP by increasing the supply of general skills. Using aggregated data for 12 European OECD counties, we calibrate the model and compare the theoretical prediction with the data. In cross-country comparisons, we find that the returns on general skills and the impact of general education expenditure on GDP are higher in countries with higher total factor productivity. These findings support our theoretical argument of the positive relationship between firms’ demand for general skills and countries’ stages of development.

Acknowledgement

I would especially like to thank Tatsuro Iwaisako for his invaluable comments and encouragement. I am grateful to Koichi Futagami, Masaru Inaba, Keiichi Kishi, Keigo Nishida, Ryosuke Okazawa, Yoshiyasu Ono, Kouki Sugawara, Katsuya Takii, participants in the DSGE conference 2016 at Ehime University, participants in the workshop on the economics of human resource allocation 2017 at Osaka University, participants in Nagoya Macroeconomics Workshop 2017 at Nagoya Gakuin University.

Appendix

Appendix A: proof of g L , t = 0

In this appendix, we prove that gL,t = 0 holds for any equilibrium. Conversely, we assume that gH,t > 0 and gL,t > 0. Then, firms’ demand for general skilled workers is obtained as follows:

Using these expressions, the firms’ problem in the first stage can be expressed as follows:

The maximization problem is linear in st and, hence, the non-negative constraint gL,t ≥ 0 has to be binding. Thus, we have gL,t = 0.

Appendix B: proofs of Lemma 1 and Proposition 1

From (18), we have that

Combining (33) and (20), we have that at−1 must satisfy the following inequality:

Solving the above inequality with respect to at−1 yields

Further, in order to guarantee the existence of general skills,

Appendix C: proof of Proposition 2

From (21), we have that the dynamics of at satisfy

Finally, because μ must satisfy

The left-hand side of the above inequality decreases in γ and is equal to 0 when γ → 1. On the other hand, the right-hand side increases in γ and is equal to 0 when γ → π. That is, γ has to be large enough to ensure that

Appendix D

First, we return to the second-stage problem of firms, and resolve gH, t and xi, t. The second-stage problem of type-H firms is as follows:

The first-order conditions with respect to gH, t and xH, t are, respectively,

and

Using the above two first-order conditions, we obtain

Then, we have the technology level of type-H firms as

Next, the first-stage problem of firms can be written as

Note that

We focus on the equilibrium that satisfies the condition given in (36), in which both G-skill and S-skill workers exist. Section 5 showed that all estimates obtained from our calibration satisfy (36). Finally, the first-order condition of this problem yields

Rearranging (34) and (37) by evaluating at the steady state and substituting

Appendix E: proof of Proposition 3

In this appendix, we examine the steady-state characteristics using the system given in (27) and (29). We first show that the steady-state values, g* and a*, increase in

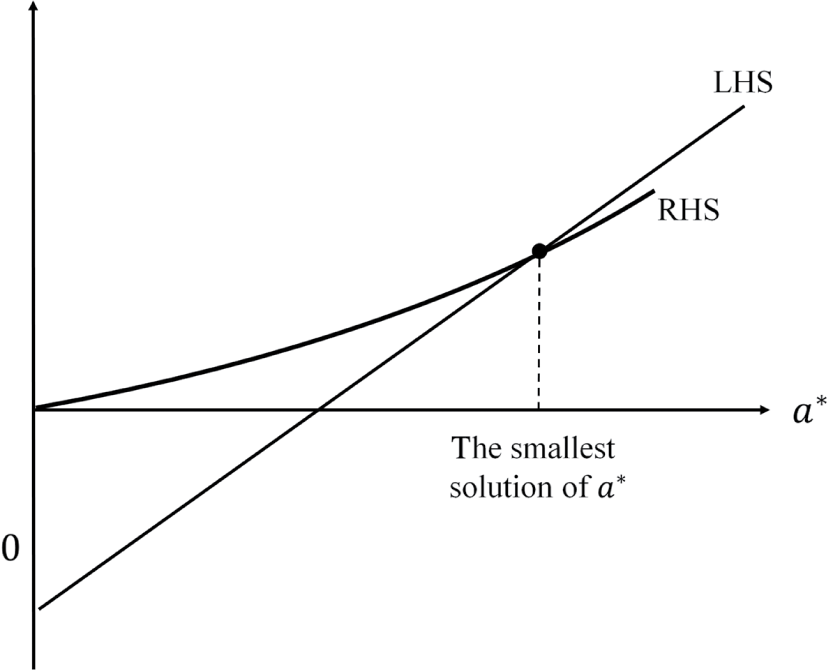

Here, a* is determined from the above expression. The left-hand side (LHS) of the above expression is increasing and is a linear function of a* with a negative intercept. At the same time, the right-hand side (RHS) increases in a*, and passes through the origin. However, we cannot examine the number of intersections between the LHS and RHS curves because very little is known about the shape of the RHS function. However, we have that if the LHS and the RHS curves have one or more intersections, the value of the smallest steady-state increases in

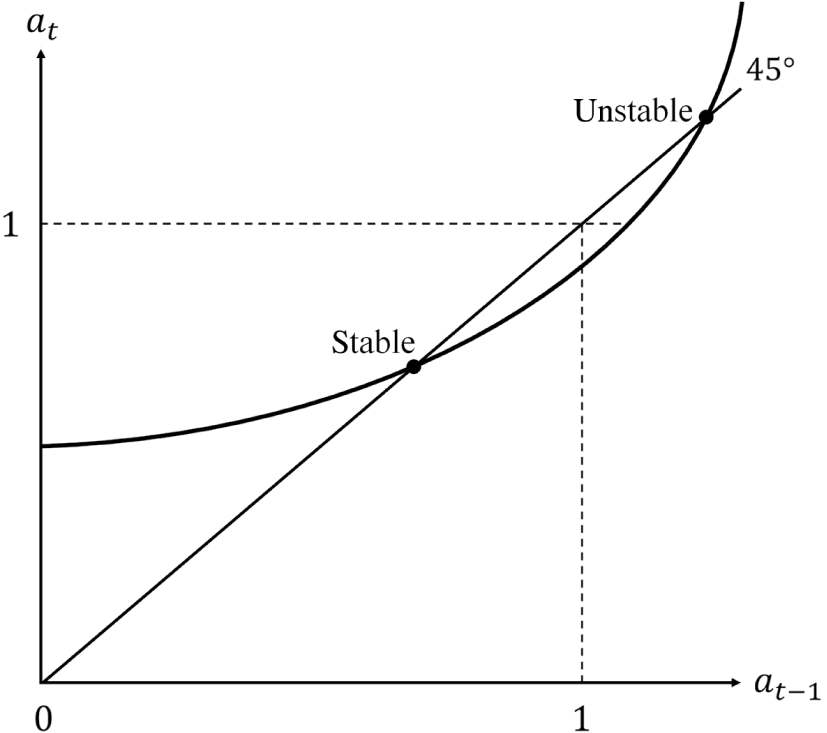

Next, we investigate the stability of the steady state corresponding to the smallest solution of a*. Let us denote as gt the total number of G-skill workers in equilibrium, but not in the steady state. Then, substituting

and

Moreover, using (22) together with st = 1 − gt and

The three endogenous variables, gt, at, and

References

Acemoglu, D. 1998. “Why do New Technologies Complement Skills? Directed Technical Change and Wage Inequality.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 113 (4): 1055–1089.10.1162/003355398555838Search in Google Scholar

Acemoglu, D., P. Aghion, and F. Zilibotti. 2006. “Distance to Frontier Selection and Economic Growth.” Journal of the European Economic Association 4 (1): 37–74.10.1162/jeea.2006.4.1.37Search in Google Scholar

Arum, R., and Y. Shavit. 1995. “Secondary Vocational Education and the Transition from School to Work.” Sociologw of Education 68 (3): 187–204.10.2307/2112684Search in Google Scholar

Basu, S., and M. K. Mehra. 2014. “Endogenous Human Capital Formation, Distance to Frontier and Growth.” Research in Economics 68 (2): 117–132.10.1016/j.rie.2013.11.002Search in Google Scholar

Becker, G. 1962. “Investment in Human Capital: A Theoretical Analysis.” Journal of Political Economy 70 (5): 9–49.10.1086/258724Search in Google Scholar

Bertocchi, G., and M. Spagat, 2004. “The Evolution of Modern Educational Systems: Technical vs. General Education, Distributional Conflict, and Growth.” Journal of Development Economics 73 (2): 559–582.10.1016/j.jdeveco.2003.05.003Search in Google Scholar

Caselli, F. 1999. “Technological Revolutions.” American Economic Review 89 (1): 78–102.10.1257/aer.89.1.78Search in Google Scholar

Cerina, F., and F. Manca. 2018. “Catch me if you Learn: Development-Specific Education and Economic Growth.” Macroeconomic Dynamics 22: 1652–1694.10.1017/S1365100516000857Search in Google Scholar

Charlot, O., B. Decreuse, and P. Granier. 2005. “Adaptability, Productivity, and Educational Incentives in a Matching Model.” European Economic Review 49 (4): 1007–1032.10.1016/j.euroecorev.2003.08.011Search in Google Scholar

Decreuse, B., and P. Granier. 2013. “Unemployment Benefits, Job Protection, and the Nature of Educational Investment.” Labour Economics 23: 20–29.10.1016/j.labeco.2013.03.001Search in Google Scholar

Di Maria, C., and P. Stryszowski. 2009. “Migration, Human Capital Accumulation and Economic Development.” Journal of Development Economics 90 (2): 306–313.10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.06.008Search in Google Scholar

Dohse, D., and I. Ott. 2014. “Heterogenous Skills, Growth and Convergence.” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 30: 52–67.10.1016/j.strueco.2014.01.003Search in Google Scholar

Dustmann, C., and C. Meghir. 2005. “Wages, Experience and Seniority.” Review of Economic Studies 72 (1): 77–108.10.1111/0034-6527.00325Search in Google Scholar

Galor, O., and O. Moav. 2000. “Ability-Based Technological Transition, Wage Inequality, and Economic Growth.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 115 (2): 469–497.10.1162/003355300554827Search in Google Scholar

Galor, O., and D. Tsiddon. 1997. “Technological Progress, Mobility, and Economic growth.” The American Economic Review 87 (3): 363–382.Search in Google Scholar

Gervais, M., I. Livshits, and C. Meh. 2008. “Uncertainty and the Specificity of Human Capital.” Journal of Economic Theory 143 (1): 469–498.10.1016/j.jet.2007.10.003Search in Google Scholar

Goldin, C. 2001. “The Human Capital Century and American Leadership: Virtues of the Past.” Journal of Economic History 61 (2): 263–292.10.1017/S0022050701028017Search in Google Scholar

Gould, E., O. Moav, and B. Weinverg. 2001. “Precautionary Demand for Education, Inequality, and Technological Progress.” Journal of Economic Growth 6 (4): 285–315.10.1023/A:1012782212348Search in Google Scholar

Guren, A., D. Hemous, and M. Olsen. 2015. “Trade Dynamics with Sector-Specific Human Capital.” Journal of International Economics 97 (1): 126–147.10.1016/j.jinteco.2015.04.003Search in Google Scholar

Hall, Caroline. 2012. “The Effects of Reducing Tracking in Upper Secondary School: Evidence from a Large-Scale Pilot Scheme." Journal of Human Resources 47 (1): 237–269.10.3368/jhr.47.1.237Search in Google Scholar

Hanushek, E. A. 2013. “Economic Growth in Developing Countries: The Role of Human Capital.” Economics of Education Review 37: 204–212.10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.04.005Search in Google Scholar

Hanushek, E. A., and L. Woessmann. 2012. “Do Better Schools Lead to More Growth? Cognitive Skills, Economic Outcomes, and Causation.” Journal of Economic Growth 17 (4): 267–321.10.1007/s10887-012-9081-xSearch in Google Scholar

Hanushek, E. A., G. Schwerdt, L. Woessmann, and L. Zhang. 2017. “General Education, Vocational Education, and Labor Market Outcomes over the Lifecycle.” Journal of Human Resources 52 (1): 48–87.10.3368/jhr.52.1.0415-7074RSearch in Google Scholar

Hassler, J., and J. V. Rodriguez Mora. 2000. “Intelligence, Social Mobility, and Growth.” American Economic Review 90 (4): 888–908.10.1257/aer.90.4.888Search in Google Scholar

Kambourov, G., and I. Manovskii. 2009a. “Occupational Specificity of Human Capital.” International Economic Review 50 (1): 63–115.10.1111/j.1468-2354.2008.00524.xSearch in Google Scholar

Kambourov, G., and I. Manovskii. 2009b. “Occupational Mobility and Wage Inequlality.” Review of Economic Studies 76 (2): 731–759.10.1111/j.1467-937X.2009.00535.xSearch in Google Scholar

Kim, S. J., and Y. Kim. 2000. “Growth Gains from Trade and Education.” Journal of International Economics 50 (2): 519–545.10.1016/S0022-1996(99)00012-4Search in Google Scholar

Krueger, D., and K. B. Kumar. 2004a. “Skill-Specific Rather than General Education: A reason for US-Europe Growth Differences?” Journal of Economic Growth 9 (2): 167–207.10.1023/B:JOEG.0000031426.09886.bdSearch in Google Scholar

Krueger, D., and K. B. Kumar. 2004b. “US-Europe Differences in Technology-Driven Growth: Quantifying the Role of Education.” Journal of Monetary Economics 51 (1): 161–190.10.1016/j.jmoneco.2003.07.005Search in Google Scholar

Kuczera, M. 2017. “Striking the Right Balance: Costs and Benefits of Apprenticeship.” OECD Education Working Papers, No 153. Paris: OECD Publishing.Search in Google Scholar

Lazear, E. P. 2009. “Firm-Specific Human Capital: A Skill-Weights Approach.” Journal of Political Economy 117 (5): 914–940.10.1086/648671Search in Google Scholar

Malamud, O., and C. Pop-Eleches. 2010. “General Education Versus Vocational Training: Evidence from an Economy in Transition.” Review of Economics and Statistics 92 (1): 43–60.10.1162/rest.2009.11339Search in Google Scholar

Meyer, T. 2003. "When being smart is not enough: institutional and social access barriers to upper secondary education and their consequences on successful labour market entry. The case of Switzerland." Competencies and Careers of the European Research Network on Transitions in Youth (TIY).Search in Google Scholar

Mies, V. 2019. “Technology Adoption During the Process of Development: Implications for Long Run Prospects. ” Macroeconomic Dynamics 23: 907–942.10.1017/S1365100517000074Search in Google Scholar

Nelson, R., and S. Phelps. 1966. “Investment in Humans, Technological Diffusion, and Economic Growth.” American Economic Review 56 (1): 69–75.Search in Google Scholar

OECD. 2012. Education at a Glance: OECD Indicators 2012. Paris: OECD.Search in Google Scholar

OECD. 2014. Education at a Glance: OECD Indicators 2014. Paris: OECD.Search in Google Scholar

Ryan, Paul. 2001. “The School-To-Work Transition: A Cross-National Perspective.” Journal of Economic Literature 39 (1): 34–92.10.1257/jel.39.1.34Search in Google Scholar

Sanders, C., and C. Taber. 2012. “Life-Cycle Wage Growth and Heterogeneous Human Capital.” Annual Review of Economics 4: 399–425.10.1146/annurev-economics-080511-111011Search in Google Scholar

Silos, P., and E. Smith. 2015. “Human Capital Portfolios.” Review of Economic Dynamics 18 (3): 635–652.10.1016/j.red.2014.09.001Search in Google Scholar

Stenberg, A., and O. Westerlund. 2015. “The Long-Term Earnings Consequences of General vs. Specific Training of the Unemployed.” IZA Journal of European Labor Studies 4 (1): 1–26.10.1186/s40174-015-0047-9Search in Google Scholar

Sumsion, C., and J. Goodfellow. 2004. “Identifying Generic Skills Through Curriculum Mapping: A Critical Evaluation.” Higher Education Research & Development 23 (3): 329–346.10.1080/0729436042000235436Search in Google Scholar

Vandenbussche, J., P. Aghion, and C. Meghir. 2006. “Growth, Distance to Frontier and Composition of Human Capital.” Journal of Economic Growth 11 (2): 97–127.10.1007/s10887-006-9002-ySearch in Google Scholar

Violante, G. 2002. “Technological Acceleration, Skill Transferability, and the Rise in Residual Inequality.” Quarterly Journal of Economics CXVII: 297–338.10.1162/003355302753399517Search in Google Scholar

Wasmer, E. 2006. “General Versus Specific Skills in Labor Markets with Search Frictions and Firing Costs.” American Economic Review 96 (3): 811–831.10.1257/aer.96.3.811Search in Google Scholar

Westergaard, N., and A. Rasmussen. 1999. The Impact of Subsidies on Apprenticeship Training. Aarhus: Centre for Labour Market and Social Research.Search in Google Scholar

Wolter, Stephen C., and P. Ryan. 2011. “Apprenticeship.” In Handbook of Economics of Education, edited by Eric A. Hanushek, Stephen Machin, and Ludger Woessmann, Chapter 11, Vol. 3, 522–576. Elsevier.10.1016/B978-0-444-53429-3.00011-9Search in Google Scholar

©2020 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Contributions

- An empirical study on the New Keynesian wage Phillips curve: Japan and the US

- Risk averse banks and excess reserve fluctuations

- Advances

- Signaling in monetary policy near the zero lower bound

- Contributions

- Robust learning in the foreign exchange market

- Foreign official holdings of US treasuries, stock effect and the economy: a DSGE approach

- Discretion rather than rules? Outdated optimal commitment plans versus discretionary policymaking

- Agency costs and the monetary transmission mechanism

- Advances

- Optimal monetary policy in a model of vertical production and trade with reference currency

- The financial accelerator and marketable debt: the prolongation channel

- The welfare cost of inflation with banking time

- Prospect Theory and sentiment-driven fluctuations

- Contributions

- Household borrowing constraints and monetary policy in emerging economies

- The macroeconomic impact of shocks to bank capital buffers in the Euro Area

- The effects of monetary policy on input inventories

- The welfare effects of infrastructure investment in a heterogeneous agents economy

- Advances

- Collateral and development

- Contributions

- Financial deepening in a two-sector endogenous growth model with productivity heterogeneity

- Is unemployment on steroids in advanced economies?

- Monitoring and coordination for essentiality of money

- Dynamics of female labor force participation and welfare with multiple social reference groups

- Advances

- Technology and the two margins of labor adjustment: a New Keynesian perspective

- Contributions

- Changing demand for general skills, technological uncertainty, and economic growth

- Job competition, human capital, and the lock-in effect: can unemployment insurance efficiently allocate human capital

- Fiscal policy and the output costs of sovereign default

- Animal spirits in an open economy: an interaction-based approach to the business cycle

- Ramsey income taxation in a small open economy with trade in capital goods

Articles in the same Issue

- Contributions

- An empirical study on the New Keynesian wage Phillips curve: Japan and the US

- Risk averse banks and excess reserve fluctuations

- Advances

- Signaling in monetary policy near the zero lower bound

- Contributions

- Robust learning in the foreign exchange market

- Foreign official holdings of US treasuries, stock effect and the economy: a DSGE approach

- Discretion rather than rules? Outdated optimal commitment plans versus discretionary policymaking

- Agency costs and the monetary transmission mechanism

- Advances

- Optimal monetary policy in a model of vertical production and trade with reference currency

- The financial accelerator and marketable debt: the prolongation channel

- The welfare cost of inflation with banking time

- Prospect Theory and sentiment-driven fluctuations

- Contributions

- Household borrowing constraints and monetary policy in emerging economies

- The macroeconomic impact of shocks to bank capital buffers in the Euro Area

- The effects of monetary policy on input inventories

- The welfare effects of infrastructure investment in a heterogeneous agents economy

- Advances

- Collateral and development

- Contributions

- Financial deepening in a two-sector endogenous growth model with productivity heterogeneity

- Is unemployment on steroids in advanced economies?

- Monitoring and coordination for essentiality of money

- Dynamics of female labor force participation and welfare with multiple social reference groups

- Advances

- Technology and the two margins of labor adjustment: a New Keynesian perspective

- Contributions

- Changing demand for general skills, technological uncertainty, and economic growth

- Job competition, human capital, and the lock-in effect: can unemployment insurance efficiently allocate human capital

- Fiscal policy and the output costs of sovereign default

- Animal spirits in an open economy: an interaction-based approach to the business cycle

- Ramsey income taxation in a small open economy with trade in capital goods