Abstract

The two leading explanations of the observed persistence in policy interest rate changes are monetary policy inertia and omitted serially correlated shocks. This paper addresses the persistence debate from the perspective of how to properly model policy rates. An ordered probit model is used to account for the discrete nature of interest rate adjustment, an aspect of policy absent in standard models. Ordered probit results show that the impact of inertia on interest rate setting is considerably smaller than indicated by standard models.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Bill Neilson, Mohammed Mohsin, Christian Vossler, participants at the Midwest Econometrics Group and Southern Economic Association meetings, and seminar attendees at the University of Tennessee for helpful comments. Any remaining errors are mine.

Appendix

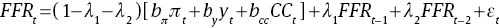

In this section, I present direct estimates of inertia in the ordered probit model. I start with the traditional partial adjustment model from equation (5), except the model is extended with FFRt−2 to allow second-order dynamics in monthly interest rate setting.

The extended policy rule is consistent with previous studies: Woodford (2003b) demonstrates that optimal policy rules in New Keynesian models feature second-order partial adjustment; Coibion and Gorodnichenko (2012) show that recent Fed policy is best described by partial adjustment of second order without a significant role for serially correlated shocks.

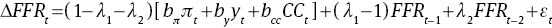

With FFRt−1 subtracted from both sides of equation (A1), the rule can be rewritten as follows.

The ordered probit estimates for equation (A2) along with autocorrelation score statistics and associated p-values are reported in the table at the end of the section.

The score statistics are insignificant at 5 percent level, indicating that residual serial correlation is not a major concern.

Regarding individual response parameters, I obtain bπ=1.36 for inflation, which is close to 1.5 originally proposed by Taylor (1993) and satisfies the Taylor-rule property; increases in inflation lead to greater than one-for-one changes in the nominal interest rate, thereby raising the real interest rate. For the output gap, I receive by=0.85, which is somewhat higher than 0.5 from the Taylor rule.

A word of caution is in order at this point. In the ordered probit framework, the assumed standard deviation of model errors determines the size of estimated parameters; estimates can be made arbitrarily large or small via renormalization. That said, in the current setting with the standard deviation of errors set to unity, the model appears to yield estimates for bπ and by that are realistic and in line with the literature on empirical policy rules.

For the parameter of interest, I obtain λ1+λ2=0.7 in monthly estimation. How does the speed of adjustment implied by this figure compare to standard rules? The typical estimate of λ=0.8 in standard quarterly models indicates that the Fed takes about 3.11 quarters, or over 9 months, to close one half of the gap between the desired funds rate and the actual funds rate: half-life=ln(0.5)/ln(0.8)=3.11. By contrast, the ordered probit estimate of λ=0.7 indicates that the Fed carries out the same adjustment in merely 1.94 months. This figure is consistent with the main result of an upward inertia bias in standard rules and a more convincing estimate of the speed with which the central bank responds to macro developments.

Direct estimates of inertia in the ordered probit model

| Coefficients | Parameter estimate | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| bπ | 1.36 | 0.00 |

| by | 0.85 | 0.00 |

| bcc | −4.60 | 0.00 |

| λ(λ1+λ2) | 0.70 | 0.00 |

| Autocorrelation score statistics | ||

| ξ1 | 0.04 | 0.84 |

| ξ2 | 1.70 | 0.19 |

| ξ3 | 3.59 | 0.06 |

| ξ4 | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| ξ5 | 0.17 | 0.68 |

| ξ6 | 3.01 | 0.08 |

Maximum likelihood estimates for policy response parameters in the ordered probit model are reported. Serial correlation scores and corresponding p-values are also presented.

References

Bayar, O. 2014. “Temporal Aggregation and Estimated Monetary Policy Rules.” The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics (Contributions) 14: 553–577.10.1515/bejm-2013-0124Search in Google Scholar

Carrillo, J., P. Feve, and J. Matheron. 2007. “Monetary Policy Inertia or Persistent Shocks: A DSGE Analysis.” International Journal of Central Banking 3: 1–38.Search in Google Scholar

Carstensen, K. 2006. “Estimating the ECB Policy Reaction Function.” German Economic Review 7: 1–34.10.1111/j.1468-0475.2006.00145.xSearch in Google Scholar

Choi, W. 1999. “Estimating the Discount Rate Policy Reaction Function of the Monetary Authority.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 14: 379–401.10.1002/(SICI)1099-1255(199907/08)14:4<379::AID-JAE516>3.0.CO;2-2Search in Google Scholar

Clarida, R., J. Gali, and M. Gertler. 2000. “Monetary Policy Rules and Macroeconomic Stability: Evidence and Some Theory.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 115: 1147–1180.10.1162/003355300554692Search in Google Scholar

Coibion, O., and Y. Gorodnichenko. 2012. “Why Are Target Interest Rate Changes So Persistent?” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 4: 126–162.10.1257/mac.4.4.126Search in Google Scholar

Consolo, A., and C. Favero. 2009. “Monetary Policy Inertia: More a Fiction than a Fact?” Journal of Monetary Economics 49: 1161–1187.10.1016/j.jmoneco.2009.06.007Search in Google Scholar

Dueker, M. 1992. “The Response of Market Interest Rates to Discount Rate Changes.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 74: 78–91.10.20955/r.74.78-91Search in Google Scholar

Dueker, M. 1999. “Measuring Monetary Policy Inertia in Target Fed Funds Rate Changes.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 81: 3–10.10.20955/r.81.3-10Search in Google Scholar

Eichengreen, B., M. Watson, and R. Grossman. 1985. “Bank Rate Policy under the Interwar Gold Standard: A Dynamic Probit Approach.” Economic Journal 95: 725–745.10.2307/2233036Search in Google Scholar

English, W., W. Nelson, and B. Sack. 2003. “Interpreting the Significance of the Lagged Interest Rate in Estimated Monetary Policy Rules.” The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics (Contributions) 3: 1–16.10.2202/1534-6005.1073Search in Google Scholar

Gali, J., S. Gerlach, J. Rotemberg, H. Uhlig, and M. Woodford. 2004. The Monetary Policy Strategy of the ECB Reconsidered: Monitoring the European Central Bank 5. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.Search in Google Scholar

Genberg, H., and S. Gerlach. 2004. Estimating Central Bank Reaction Functions with Ordered Probit: A Note. Manuscript, Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva.Search in Google Scholar

Gerlach, S., and G. Schnabel. 2000. “The Taylor Rule and Interest Rates in the EMU Area.” Economics Letters 67: 165–171.10.1016/S0165-1765(99)00263-3Search in Google Scholar

Gerlach-Kristen, P. 2004. “Interest-Rate Smoothing: Monetary Policy Inertia or Unobserved Variables?” The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics (Contributions) 4: 1–17.10.2202/1534-6005.1169Search in Google Scholar

Goodfriend, M. 1991. “Interest Rates and the Conduct of Monetary Policy.” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 34: 7–37.10.1016/0167-2231(91)90002-MSearch in Google Scholar

Gourieroux, C., A. Monfort, and A. Trognon. 1985. “A General Approach to Serial Correlation.” Econometric Theory 1: 315–340.10.1017/S0266466600011245Search in Google Scholar

Hakes, D. 1990. “The Objectives and Priorities of Monetary Policy and Different Federal Reserve Chairmen.” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 22: 327–337.10.2307/1992563Search in Google Scholar

Hamilton, J., and O. Jorda. 2002. “A Model of the Federal Funds Rate Target.” Journal of Political Economy 110: 1135–1167.10.1086/341872Search in Google Scholar

Hausman, J., A. Lo, and A. MacKinlay. 1992. “An Ordered Probit Analysis of Transaction Stock Prices.” Journal of Financial Economics 31: 319–379.10.1016/0304-405X(92)90038-YSearch in Google Scholar

Horowitz, J. 2001. “The Bootstrap.” In Handbook of Econometrics, Vol. 5, edited by J. J. Heckman and E. E. Leamer, Amsterdam: North-Holland.Search in Google Scholar

Judd, J., and G. Rudebusch. 1998. “Taylor’s Rule and the Fed: 1970-1997.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Review 3: 3–16.Search in Google Scholar

Kobayashi, T. 2010. “Policy Irreversibility and Interest Rate Smoothing.” The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics (Topics) 10: 1–27.10.2202/1935-1690.2106Search in Google Scholar

MacKinnon, J. 2006. “Bootstrap Methods in Econometrics.” The Economic Record, Economic Society of Australia 82: 2–18.10.1111/j.1475-4932.2006.00328.xSearch in Google Scholar

Orphanides, A. 2001. “Monetary Policy Rules Based on Real-Time Data.” American Economic Review 91: 964–985.10.1257/aer.91.4.964Search in Google Scholar

Rudebusch, G. 2002. “Term Structure Evidence on Interest Rate Smoothing and Monetary Policy Inertia.” Journal of Monetary Economics 49: 1161–1187.10.1016/S0304-3932(02)00149-6Search in Google Scholar

Rudebusch, G. 2006. “Monetary Policy Inertia: Fact or Fiction?” International Journal of Central Banking 2: 85–135.10.2139/ssrn.864484Search in Google Scholar

Rudebusch, G., and T. Wu. 2008. “A Macro-Finance Model of the Term Structure, Monetary Policy and the Economy.” The Economic Journal 118: 906–926.10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02155.xSearch in Google Scholar

Sack, B. 2000. “Does the Fed Act Gradually? A VAR Analysis.” Journal of Monetary Economics 46: 229–256.10.1016/S0304-3932(00)00019-2Search in Google Scholar

Sack, B., and V. Wieland. 2000. “Interest-Rate Smoothing and Optimal Monetary Policy: A Review of Recent Empirical Evidence.” Journal of Economics and Business 52: 205–228.10.1016/S0148-6195(99)00030-2Search in Google Scholar

Taylor, J. 1993. “Discretion versus Policy Rules in Practice.” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 39: 195–214.10.1016/0167-2231(93)90009-LSearch in Google Scholar

Woodford, M. 2003a. “Optimal Interest Rate Smoothing.” Review of Economic Studies 70: 861–886.10.1111/1467-937X.00270Search in Google Scholar

Woodford, M. 2003b. Interest and Prices: Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.10.1515/9781400830169Search in Google Scholar

©2015 by De Gruyter

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Advances

- International specialization and the return to capital

- How the wage-education profile got more convex: evidence from Mexico

- Contributions

- Africa’s missed agricultural revolution: a quantitative study of the policy options

- Structural transformation and productivity in Latin America

- Public debt and growth in the euro area: evidence from parametric and nonparametric Granger causality

- Transition dynamics in the neoclassical growth model: the case of South Korea

- Household saving in Australia

- An ordered probit analysis of monetary policy inertia

- Fiscal shocks, the real exchange rate and the trade balance: some evidence for emerging economies

- Topics

- Remittances and financial institutions: is there a causal linkage?

- Club convergence in Latin America

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Advances

- International specialization and the return to capital

- How the wage-education profile got more convex: evidence from Mexico

- Contributions

- Africa’s missed agricultural revolution: a quantitative study of the policy options

- Structural transformation and productivity in Latin America

- Public debt and growth in the euro area: evidence from parametric and nonparametric Granger causality

- Transition dynamics in the neoclassical growth model: the case of South Korea

- Household saving in Australia

- An ordered probit analysis of monetary policy inertia

- Fiscal shocks, the real exchange rate and the trade balance: some evidence for emerging economies

- Topics

- Remittances and financial institutions: is there a causal linkage?

- Club convergence in Latin America