Abstract

Based on the decline in real GDP growth, many economists now believe that the “Great Recession” is the deepest global economic contraction since the Great Depression. But as real-time real GDP data is typically revised, we investigate if the decline in, and total output loss (severity) of, G-7 real GDP during the “Great Recession” is really so different from the past. We use a GDP weighted average of, as well as a dynamic common factor extracted from, real-time G-7 real GDP data to verify if this is the case. Furthermore, we use a Mincer and Zarnowitz [Mincer, J., and V. Zarnowitz. 1969. “The Evaluation of Economic Forecasts.” NBER Volume: Economic Forecasts and Expectations: Analysis of Forecasting Behaviour and Performance, pp. 1–46.] forecast efficiency regression to predict the revision to G-7 real GDP growth during the “Great Recession,” based on outturns of unrevised variables. In real-time data, the depth and intensity of the “Great Recession” are similar to the mid-1970s recession. The Mincer and Zarnowitz model predicts significant revisions to G-7 real GDP for 2008Q4 and 2009Q1 of about 0.81% and 1.08%, respectively. Together these facts imply that G-7 real GDP growth during the “Great Recession” may yet be revised to be in line with past deep recessions.

- 1

Depth is defined as the maximum decline in real GDP growth, and severity as the total output loss, experienced during a recession.

- 2

Our weights are fixed and computed as an average over the period 1970–1980. This is the weighting scheme we use for all G-7 aggregates throughout the paper. Fixed weights obtained over a longer horizon do not make a difference to our results.

- 3

Indeed, real-time estimates of US real GDP growth during the 1990s recovery were substantially revised upwards later.

- 4

The body of literature studying this phenomenon has grown quickly in the past decade. See Croushore (2008a) for a recent survey.

- 5

Chiu and Wieladek (2012b) provide some evidence for this assertion. In contrast to their general exploration of revisions during recessions, here we are only interested in revisions to G-7 real GDP growth during the “Great Recession.”

- 6

For the G-7 aggregate, the real-time depth and total output loss (severity) during the 1970s recession were 2 and 5.2, compared to 2.2 and 3.75 for the “Great Recession.”

- 7

Most macroeconomic models suggest that monetary and fiscal policy should focus on stabilising prices and output. Banking sector problems, on the other hand, are typically within the remit of financial policy. Yet the size of the financial crisis associated with the “Great Recession” meant that monetary and fiscal policy makers were probably also targeting banking sector problems at the same time. To the extent that economic shocks were perceived to be severe at the time of previous recessions, such as at the time of oil shocks in the 1970s, one would have expected policy makers to have also targeted that particular economic shock in the past. It is therefore unclear if the “Great Recession” is necessarily unusual in that particular respect.

- 8

We will refer to data which was available at the time of previous recessions as “real-time” data for the rest of this paper.

- 9

Throughout this paper, we will refer to the current, namely 2010Q4, vintage of real GDP data as “revised” data. At the time of the revision of this paper, a more recent vintage of data, 2012Q3, which we refer to as “latest” vintage, became available. As we do not expect this vintage of data to change our estimates on past data, we use it to verify if our predicted revision has already taken place.

- 10

See Gregory, Head, and Raynauld (1997) and Kose, Otrok, and Whiteman (2008) for previous work for the G-7.

- 11

Del Negro and Otrok (2008) also introduce time-varying coefficients in addition to stochastic volatility into their dynamic common factor model to study the time-varying evolution of business cycles in 19 countries. We abstain from time-varying coefficients as Del Negro and Otrok (2008) find little role this type of time-variation, it does not affect the factor estimate in their sample and for reasons of parsimony.

- 12

One stylised fact about real GDP revisions, as argued by Jacobs and Van Norden (2011) and Siklos (2008), is that they may occur many years after the initial estimate has been published, which is why we choose 2005Q4 as a cut-off point.

- 13

- 14

The 2009 data is taken from the April 2010 edition of the OECD Main Economic Indicators.

- 15

- 16

For the UK we use the RPI.

- 17

Croushore (2008b) notes that in the US, the CPI index is not revised. We assume that the same applies for the rest of the G-7.

- 18

Our implicit assumption is that real house prices are not revised, but our results are robust to excluding this variable.

- 19

The reporting convention for international statistics has recently been updated to “System of National Accounts 2008.” However, according to the OECD (2010), the implementation of these new guidelines has been delayed and even our most recent vintage of data (2010Q4) was still compiled according to the “System of National Accounts 1993” standards.

- 20

In preliminary estimations, with a model that assumed fixed variances, the estimate of the factor during periods of greater volatility was indeed larger.

- 21

The choice of this particular posterior coverage band interval follows recent work that estimates dynamic common factor models with Bayesian methods. See for example, Mumtaz and Surico (2012) or Kose, Otrok, and Whiteman (2003).

- 22

New information can emerge a long time after the preliminary real GDP estimate has been recorded. For example, following the 2001 census in the UK, it emerged that the total population grew by only 1 million in the 1990s, rather than the two million previously assumed (Dorling 2007).

- 23

- 24

In practical terms, Bayesian Model Averaging is implemented with the STATA BMA function documented in De Luca and Magnus (2011).

- 25

The subsequent results are not affected if we adopt a threshold of 0.9 instead.

- 26

Strictly speaking, the weighted forecast for both 2008Q4 is not statistically significant at the 5% level, since the lower bound includes zero. Nevertheless, a large mass of the forecast distribution for 2008Q4 still points to a positive revision for this point in time. As a result there is still a substantial likelihood that the revision at this point in time is statistically different from zero and this is the interpretation we choose to follow.

- 27

Revisions to real GDP growth will change estimates of the output gap, which monetary policy makers partially rely on in their justification of policy. See Chiu and Wieladek (2012a) for a detailed examination of revisions to OECD output gaps.

- 28

See Carter and Kohn (1994) for derivation and further description.

We would like to thank an anonymous referee, Charles Calomiris, Rob Elder, Lucrezia Reichlin, Andrew Sentance and Martin Weale for very helpful comments and advice.

Appendix A – Data

Unemployment rate changes

Unemployment rate change for the G-7 excluding France.

Source: Past and latest editions of OECD MEI.

Note: The blue and the red line show the preliminary and current vintage (2010Q2) outturns of changes to the unemployment rate. The scale is expressed in percent.

Unemployment rate change for Canada.

Source: Past and latest editions of OECD MEI.

Note: The blue and the red line show the preliminary and current vintage (2010Q2) outturns of changes to the unemployment rate. The scale is expressed in percent.

Unemployment rate change for Japan.

Source: Past and latest editions of OECD MEI.

Note: The blue and the red line show the preliminary and current vintage (2010Q2) outturns of changes to the unemployment rate. The scale is expressed in percent.

Unemployment rate change for Germany.

Source: Past and latest editions of OECD MEI.

Note: The blue and the red line show the preliminary and current vintage (2010Q2) outturns of changes to the unemployment rate. The scale is expressed in percent.

Unemployment rate change for Italy.

Source: Past and latest editions of OECD MEI.

Note: The blue and the red line show the preliminary and current vintage (2010Q2) outturns of changes to the unemployment rate. The scale is expressed in percent.

Unemployment rate change for the US.

Source: Past and latest editions of OECD MEI.

Note: The blue and the red line show the preliminary and current vintage (2010Q2) outturns of changes to the unemployment rate. The scale is expressed in percent.

Unemployment rate change for the UK.

Source: Past and latest editions of OECD MEI.

Note: The blue and the red line show the preliminary and current vintage (2010Q2) outturns of changes to the unemployment rate. The scale is expressed in percent.

Real GDP growth revisions in past UK and US recessions

Different vintages of real GDP data – UK 1973 recession.

Source: Bank of England Real-time Database.

Note: This figure shows real GDP year-on-year growth as indicated by the first-available vintage (real-time data), and 2 years (red line), 3 years (green line) and 9 years (purple line) after the end of the recession. The scale is expressed in percent.

Different vintages of real GDP data – UK 1981 recession.

Source: Bank of England Real-time Database.

Note: This figure shows real GDP year-on-year growth as indicated by the first-available vintage (real-time data), and 2 years (red line), 3 years (green line) and 9 years (purple line) after the end of the recession. The scale is expressed in percent.

Different vintages of real GDP data – UK 1990s recession.

Source: Bank of England Real-time Database.

Note: This figure shows real GDP year-on-year growth as indicated by the first-available vintage (real-time data), and 2 years (red line), 3 years (green line) and 9 years (purple line) after the end of the recession. The scale is expressed in percent.

Different vintages of real GDP data – US 1975 recession.

Source: Croushore and Stark (2001).

Note: This figure shows real GDP year-on-year growth as indicated by the first-available vintage (real-time data), and 2 years (red line), 3 years (green line) and 9 years (purple line) after the end of the recession. The scale is expressed in percent.

Different vintages of real GDP data – US 1981 recession.

Source: Croushore and Stark (2001).

Note: This figure shows real GDP year-on-year growth as indicated by the first-available vintage (real-time data), and 2 years (red line), 3 years (green line) and 9 years (purple line) after the end of the recession. The scale is expressed in percent.

Different vintages of real GDP data – US 1990 recession.

Source: Croushore and Stark (2001).

Note: This figure shows real GDP year-on-year growth as indicated by the first-available vintage (real-time data), and 2 years (red line), 3 years (green line) and 9 years (purple line) after the end of the recession. The scale is expressed in percent.

Different vintages of real GDP data – US 2001 recession.

Source: Croushore and Stark (2001).

Note: This figure shows real GDP year-on-year growth as indicated by the first-available vintage (real-time data), and 2 years (red line), 3 years (green line) and 9 years (purple line) after the end of the recession. The scale is expressed in percent.

Real equity and house price growth in the G-7

Real year-on-year equity and house price growth for the G-7.

Source: OECD Main Economic Indicators.

Note: This figure shows year-on-year growth rates of equity and house prices, deflated by the CPI. The scale on either side is in percent.

Real year-on-year equity and house price growth for Canada.

Source: OECD Main Economic Indicators.

Note: This figure shows year-on-year growth rates of equity and house prices, deflated by the CPI. The scale on either side is in percent.

Real year-on-year equity and house price growth for France.

Source: OECD Main Economic Indicators.

Note: This figure shows year-on-year growth rates of equity and house prices, deflated by the CPI. The scale on either side is in percent.

Real year-on-year equity and house price growth for Germany.

Source: OECD Main Economic Indicators.

Note: This figure shows year-on-year growth rates of equity and house prices, deflated by the CPI. The scale on either side is in percent.

Real year-on-year equity and house price growth for Italy.

Source: OECD Main Economic Indicators.

Note: This figure shows year-on-year growth rates of equity and house prices, deflated by the CPI. The scale on either side is in percent.

Real year-on-year equity and house price growth for Japan.

Source: OECD Main Economic Indicators.

Note: This figure shows year-on-year growth rates of equity and house prices, deflated by the CPI. The scale on either side is in percent.

Real year-on-year equity and house price growth for the UK.

Source: OECD Main Economic Indicators.

Note: This figure shows year-on-year growth rates of equity and house prices, deflated by the CPI. The scale on either side is in percent.

Real year-on-year equity and house price growth for the US.

Source: OECD Main Economic Indicators.

Note: This figure shows year-on-year growth rates of equity and house prices, deflated by the CPI. The scale on either side is in percent.

Appendix B

Dynamic common factor model-estimation

Estimation with Gibbs sampling permits us to break the estimation down into several steps, reducing the difficulty of implementation drastically. For instance, if the unobserved dynamic common factor in equation (4) would be known, then the estimation of the factor loadings, γi, would only involve a simple OLS regression. Similarly, if the factor loadings and the time-varying variances are known, then the estimation of the unobserved factors only involves the application of the Kalman filter to the state space form of the model in equation (6). Furthermore, given the knowledge of the error terms in equation (3) and (4), one can estimate the stochastic volatility component by applying the Kalman filter to equation (5). Finally, given knowledge of the dynamic common factor, the estimation of the autoregressive parameter in equation (4) can be performed through a simple regression of the lagged factor on itself. For this purpose we employ a Gibbs sampling algorithm that approximates the posterior distribution and describe each step of the algorithm below.

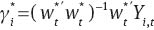

Step 1 – Estimation of the factor-loadings on all other parameters

Conditional on a draw of Wt, we draw the factor loadings γi and the associated covariance matrix. With knowledge of all the other parameters we can estimate each factor loading γi via OLS regression equation by equation. The posterior densities which we use to achieve this are:

where  and

and  where

where

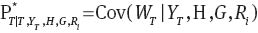

Step 2 – Estimation of the dynamic common factor and the autoregressive error terms

We can now obtain an estimate of Wt with the forward-filter, backward smoother’.28 We draw the unobservable factor Wt conditional on all other parameters from

We first iterate the Kalman filter forward through the sample, in order to calculate  and the associated variance-covariance matrix

and the associated variance-covariance matrix  at the end of the sample, namely time period T. The calculation of these parameters permits sampling from the posterior distribution in (12). We then use the last observation as an initial condition and iterate the Kalman filter backwards through the sample and draw Wt from the posterior distribution in (13) at each point in time.

at the end of the sample, namely time period T. The calculation of these parameters permits sampling from the posterior distribution in (12). We then use the last observation as an initial condition and iterate the Kalman filter backwards through the sample and draw Wt from the posterior distribution in (13) at each point in time.

Step 3 – Estimation of the stochastic volatility components

We follow the approach presented in Kim, Sheppard, and Chib (1998) to draw the stochastic volatility terms. To do this we first write the residual of each equation as  or

or  in case of the factor. We express zi,t as

in case of the factor. We express zi,t as  where c is small offset constant, to ensure that we do not take the log of 0. This transformation yields:

where c is small offset constant, to ensure that we do not take the log of 0. This transformation yields:

where  If

If  were normally distributed, then hi,t could be drawn using the standard Carter and Kohn (1994) algorithm with (14) as the measurement and (5) as the transition equation. But

were normally distributed, then hi,t could be drawn using the standard Carter and Kohn (1994) algorithm with (14) as the measurement and (5) as the transition equation. But  is distributed as a log(χ2). We follow the solution suggested in Kim, Sheppard, and Chib (1998) and approximate this distribution as a mixture of 7 normal distributions. Conditional on a draw from this distribution, we can now draw hi,t using (14) as the measurement and (5) as the transition equation. In particular:

is distributed as a log(χ2). We follow the solution suggested in Kim, Sheppard, and Chib (1998) and approximate this distribution as a mixture of 7 normal distributions. Conditional on a draw from this distribution, we can now draw hi,t using (14) as the measurement and (5) as the transition equation. In particular:

We first iterate the Kalman filter forward through the sample, in order to calculate  and the associated variance-covariance matrix

and the associated variance-covariance matrix  at the end of the sample, namely time period T. The calculation of these parameters permits sampling from the posterior distribution in (15). We then use the last observation as an initial condition and iterate the Kalman filter backwards through the sample to draw hi,t from the posterior distribution in (16) at each point in time. This procedure is performed equation by equation, consistent with the assumption that the error terms are uncorrelated across equations.

at the end of the sample, namely time period T. The calculation of these parameters permits sampling from the posterior distribution in (15). We then use the last observation as an initial condition and iterate the Kalman filter backwards through the sample to draw hi,t from the posterior distribution in (16) at each point in time. This procedure is performed equation by equation, consistent with the assumption that the error terms are uncorrelated across equations.

Step 4 – Estimation of φ, and ωi

and ωi

We draw the variance-covariance matrix  from an inverse Gamma distribution:

from an inverse Gamma distribution:

where z2 is the number of time-series observations and

where

where  The AR coefficient φ is obtained through a standard regression of wtφ on its own lagged value and the coefficients are sampled from a normal distribution. We only retain draws with roots inside the unit circle. σ0 is set to 1 in order to identify the scale of the model. The posterior density in this case is:

The AR coefficient φ is obtained through a standard regression of wtφ on its own lagged value and the coefficients are sampled from a normal distribution. We only retain draws with roots inside the unit circle. σ0 is set to 1 in order to identify the scale of the model. The posterior density in this case is:

where  and

and  where

where  Similarly, the individual ρi’s are sampled from

Similarly, the individual ρi’s are sampled from

where  and

and  where

where  ωi is drawn from an inverse Gamma distribution:

ωi is drawn from an inverse Gamma distribution:

where z3 is T+1 and δ2=0.0001+(hi,t–hi,t–1)′(hi,t–hi,t–1).

Step 5 – Go to step 1

References

Aruoba, S. B. 2008. “Data Revisions Are Not Well Behaved.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 40(2–3): 319–340,03.Search in Google Scholar

Aruoba S. B., F. Diebold, A. Kose, and M. Terrones. 2011. “Globalization, the Business Cycle and Macroeconomic Monitoring.” IMF Working Paper 11/25.Search in Google Scholar

Carter, C., and R. Kohn. 1994. “On Gibbs Sampling for State Space Models.” Biometrika 81: 541–553.10.1093/biomet/81.3.541Search in Google Scholar

Chiu, A., and T. Wieladek. 2012a. Did output gap measurement improve over time? Bank of England External MPC Unit Discussion Paper No. 36; Available at:http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/externalmpcpapers/extmpcpaper0036.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Chiu, A., and T. Wieladek. 2012b. Are real GDP Revisions During Recessions Different? Bank of England, London, UK: mimeo.Search in Google Scholar

Cogley T., G. Primiceri, and T. Sargent. 2010. “Inflation-Gap Persistence in the US.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 2(1): 43–69.10.1257/mac.2.1.43Search in Google Scholar

Croushore, D. 2008a. “Revisions to PCE Inflation Measures: Implications for Monetary Policy.” Working Papers 08-8, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.10.21799/frbp.wp.2008.08Search in Google Scholar

Croushore, D. 2008b. “Frontiers of Real-Time Data Analysis.” Working Papers 08-4, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.10.21799/frbp.wp.2008.04Search in Google Scholar

Croushore, D., and T. Stark. 2001. “A Real-Time Data Set for Macroeconomists.” Journal of Econometrics 105: 111–130.10.1016/S0304-4076(01)00072-0Search in Google Scholar

De Luca, G., and J. R. Magnus. 2011. “Bayesian Model Averaging and Weighted Average Least Squares: Equivariance, Stability, and Numerical Issues.” The Stata Journal 11: 518–544.10.1177/1536867X1201100402Search in Google Scholar

Del Negro, M., and C. Otrok. 2008. Dynamic Common Factor Models with Time-Varying Parameters. University of Virginia, manuscript.Search in Google Scholar

Doppelhofer,G., R. Miller, and X. Sala-I-Martin. 2004. “Determinants of Long-Term Growth: A Bayesian Averaging of Classical Estimates (BACE) Approach.” American Economic Review 94(4): 813–835.10.1257/0002828042002570Search in Google Scholar

Dorling, D. 2007. “How many of us are there and where are we? A Simple Independent Validation of the 2001 Census and its Revisions.” Environment and Planning 39: 1024–1044.10.1068/a38140Search in Google Scholar

Eichengreen, B., and J. O’Rourke. 2009. A tale of two depressions: What do the new data tell us? www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/3421.Search in Google Scholar

Faust, J., J. Rogers, and J. Wright. 2005. “News and Noise in G-7 GDP Announcements.” Journal of Money Credit and Banking 37(3): 403–417.10.1353/mcb.2005.0029Search in Google Scholar

Fernandez, C., E. Ley, and M. Steel. 2001. “Model Uncertainty in Cross-Country Growth Regressions.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 16(5): 563–576.10.1002/jae.623Search in Google Scholar

Gerberding, C., M. Kaatz, A. Worms, and F. Seitz. 2005. “A realtime Data set for German Key Macroeconomic Variables.” Schmollers Jahrbuch 125: 337–346.10.3790/schm.125.2.337Search in Google Scholar

Gregory, A., A. Head, and J. Raynauld. 1997. “Measuring World Business Cycles.” International Economic Review 38: 677–702.10.2307/2527287Search in Google Scholar

Harvey, A. 1993. Time Series Models, 2nd ed., New York: Harvester-Wheatsheat.Search in Google Scholar

IMF. 2009. Joint foreword to ‘World Economic Outlook’ and ‘Global Financial Stability Report’ (2009)’. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2009/01/pdf/foreword.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Jacobs, J., and S. van Norden. 2011. “Modelling Data Revisions: Measurement Error and Dynamics of ‘True’ Values.” Journal of Econometrics 161(2): 101–109.10.1016/j.jeconom.2010.04.010Search in Google Scholar

Kim, S., N. Sheppard, and S. Chib. 1998. “Stochastic Volatility: Likelihood Inference and Comparison with ARCH Models. Review of Economic Studies 65: 361–393.10.1111/1467-937X.00050Search in Google Scholar

Koop, G., and D. Korobilis. 2011. “Forecasting Inflation Using Dynamic Model Averaging.” Working Papers 1119, University of Strathclyde Business School, Department of Economics.Search in Google Scholar

Kose, A., C. Otrok, and C. Whiteman. 2003. “International Business Cycles: World, Region and Country Specific Factors.” American Economic Review 93(4): 1216–1239.10.1257/000282803769206278Search in Google Scholar

Kose, A., C. Otrok, and C. Whiteman. 2008. “Understanding The Evolution of World Business Cycles.” Journal of International Economics 75(1): 110–130.10.1016/j.jinteco.2007.10.002Search in Google Scholar

Kose, A., P. Loungani, and M. Terrones. 2011. “Global Recessions and Recoveries.” Forthcoming IMF working paper.Search in Google Scholar

Magnus, J., O. Powell, and P. Prüfer. 2010. “A Comparison of Two Model Averaging Techniques with An Application to Growth Empirics.” Journal of Econometrics 154: 139–153.10.1016/j.jeconom.2009.07.004Search in Google Scholar

Mankiw, N., D. Runkle, and M. Shapiro. 1984. “Are Preliminary Announcements of the Money Stock Rational Forecasts.” Journal of Monetary Economics 14: 15–27.10.1016/0304-3932(84)90024-2Search in Google Scholar

Mincer, J., and V. Zarnowitz. 1969. “The Evaluation of Economic Forecasts.” NBER Volume: Economic Forecasts and Expectations: Analysis of Forecasting Behaviour and Performance, pp. 1–46.Search in Google Scholar

Mumtaz, H., and P. Surico. 2012. “Evolving International Inflation Dynamics: World and Country-Specific Factor.” Journal of the European Economic Association, 10(4): 716–734, 08.Search in Google Scholar

OECD. 2010. National Accounts at a Glance 2010. Paris, 2010.Search in Google Scholar

Siklos, P. L. 2008. “What can We Learn from Comprehensive Data Revisions for Forecasting Inflation? Some US evidence.” In: Forecasting in the Presence of Structural Breaks and Model Uncertainty, edited by D. Rapach and M. E. Wohar, Amsterdam: Elsevier.10.1016/S1574-8715(07)00207-2Search in Google Scholar

Stock, J. H., and M. H. Watson. 2005. “Understanding Changes in International Business Cycle Dynamics.” Journal of the European Economic Association 3(5): 968–1006.10.1162/1542476054729446Search in Google Scholar

United Nations Statistics Division. 1993. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/sna1993.asp.Search in Google Scholar

Zellner, A. 1958. “A Statistical Analysis of Provisional Estimates of Gross National Product and Its Components, of Selected National Income Components, and of Personal Saving.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 53: 54–65.10.1080/01621459.1958.10501423Search in Google Scholar

Zellner, A. 1986. “On Assessing Prior Distributions and Bayesian Regression Analysis with g-Prior Distribution.” In: Bayesian Inference and Decision Techniques: essays in honour of Bruno de Finetti, edited by P. K. Goel and A. Zellner, 233–243. Amsterdam, North Holland: Elsevier Science Ltd.Search in Google Scholar

©2013 by Walter de Gruyter Berlin Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Advances

- How have global shocks impacted the real effective exchange rates of individual euro area countries since the euro’s creation?

- Employment by age, education, and economic growth: effects of fiscal policy composition in general equilibrium

- Overeducation and skill-biased technical change

- Strategic wage bargaining, labor market volatility, and persistence

- Households’ uncertainty about Medicare policy

- Contributions

- Deconstructing shocks and persistence in OECD real exchange rates1)

- A contribution to the empirics of welfare growth

- Development accounting with wedges: the experience of six European countries

- Implementation cycles, growth and the labor market

- International technology adoption, R&D, and productivity growth

- Bequest taxes, donations, and house prices

- Business cycle accounting of the BRIC economies

- Privately optimal severance pay

- Small business loan guarantees as insurance against aggregate risks

- Output growth and unexpected government expenditures

- International business cycles and remittance flows

- Effects of productivity shocks on hours worked: UK evidence

- A prior predictive analysis of the effects of Loss Aversion/Narrow Framing in a macroeconomic model for asset pricing

- Exchange rate pass-through and fiscal multipliers

- Credit demand, credit supply, and economic activity

- Distortions, structural transformation and the Europe-US income gap

- Monetary policy shocks and real commodity prices

- Topics

- News-driven international business cycles

- Business cycle dynamics across the US states

- Required reserves as a credit policy tool

- The macroeconomic effects of the 35-h workweek regulation in France

- Productivity and resource misallocation in Latin America1)

- Information and communication technologies over the business cycle

- In search of lost time: the neoclassical synthesis

- Divorce laws and divorce rate in the US

- Is the “Great Recession” really so different from the past?

- Monetary business cycle accounting for Sweden

Articles in the same Issue

- Masthead

- Masthead

- Advances

- How have global shocks impacted the real effective exchange rates of individual euro area countries since the euro’s creation?

- Employment by age, education, and economic growth: effects of fiscal policy composition in general equilibrium

- Overeducation and skill-biased technical change

- Strategic wage bargaining, labor market volatility, and persistence

- Households’ uncertainty about Medicare policy

- Contributions

- Deconstructing shocks and persistence in OECD real exchange rates1)

- A contribution to the empirics of welfare growth

- Development accounting with wedges: the experience of six European countries

- Implementation cycles, growth and the labor market

- International technology adoption, R&D, and productivity growth

- Bequest taxes, donations, and house prices

- Business cycle accounting of the BRIC economies

- Privately optimal severance pay

- Small business loan guarantees as insurance against aggregate risks

- Output growth and unexpected government expenditures

- International business cycles and remittance flows

- Effects of productivity shocks on hours worked: UK evidence

- A prior predictive analysis of the effects of Loss Aversion/Narrow Framing in a macroeconomic model for asset pricing

- Exchange rate pass-through and fiscal multipliers

- Credit demand, credit supply, and economic activity

- Distortions, structural transformation and the Europe-US income gap

- Monetary policy shocks and real commodity prices

- Topics

- News-driven international business cycles

- Business cycle dynamics across the US states

- Required reserves as a credit policy tool

- The macroeconomic effects of the 35-h workweek regulation in France

- Productivity and resource misallocation in Latin America1)

- Information and communication technologies over the business cycle

- In search of lost time: the neoclassical synthesis

- Divorce laws and divorce rate in the US

- Is the “Great Recession” really so different from the past?

- Monetary business cycle accounting for Sweden