Abstract

We consider a developing economy where multinational corporations compete with foreign and local firms in a monopolistically competitive market. The focus of our paper is on consequences of a policy mix of tariffs and foreign direct investment (FDI) tax in a developing economy. We assume all firms are technologically heterogeneous and that foreign firms are technologically superior to local firms. Central to our model is the assumption that FDI activities by multinational corporations would lead to diffusion of technology in the developing economy. We show the existence of a non-trivial equilibrium where most technologically advanced foreign firms emerge as multinationals, engage in FDI activities and this in turn leads to the diffusion of technology. We also show that trade liberalization without liberalization of foreign investment may lead to the protection of most technological backward local firms in the developing economy and such liberalization can reduce the welfare of a representative consumer.

1 Introduction

The rapid pace of globalization over the past few decades has been to a large extent through expansion of foreign trade and international movement of capital. On the one hand, multinational corporations have played a major role in bringing about tremendous growth in the flow of foreign direct investment (FDI). On the other hand, pursuit of trade liberalization and reduction in foreign investment barriers by governments have been crucial factors in facilitating such growth in international trade and foreign investment. While interplaying of trade and investment liberalizations and its effects on growth of international trade and investment are generally applicable to any economy (developed or developing), there are additional issues specific to developing economies. One such issue is the stark technological differences between developed and developing economies and the possible diffusion of technology from developed countries to the less technologically advanced developing countries. In this paper we study the interaction between trade and FDI liberalization in a developing country as in Chao and Yu (1997) and its effects on FDI activities by multinational corporations. We then analyze their role in technology diffusion, assuming that all firms (foreign and local) are technologically heterogeneous.

In sum, this paper shows that trade liberalization may result in non-uniform outcomes in developing countries due to the effects of technology diffusion and its pattern. Foreign firms alter their decision on export to developing countries versus their FDI in these countries in response to trade liberalization in developing countries. As FDI is a carrier of foreign technology and causes technology diffusion in the host countries, trade liberalization can influence the flow of more advanced foreign technology into these developing countries. Also, technological heterogeneity of local firms in developing countries plays a crucial role and can determine the pattern of technology diffusion. If local firm heterogeneity leads to a non-uniform pattern of technology diffusion such that more technologically advanced local firms benefit more from diffusion of technology, then trade liberalization (without a change in investment policy) may have a more negative impact (as far as the benefit of diffusion is concerned) on technologically advanced local firms compared with the less advanced local firms. Thus, trade liberalization without liberalizing foreign investment may lead to the protection of small and technologically backward local firms in developing countries. Clearly, this is in sharp contrast with a generally held view by some policy makers and voiced by popular press that trade harms small businesses (for example, see Business (2013)). Hence, this result begs for an explanation at the outset of our paper. To make our case for such a possibility, consider footwear industry in India as an example. Local firms range from small shoe makers with backward handmade technology to automated shoe-making manufacturing. Since small low tech firms may not use computers in their production technology, presence of multinational corporation through FDI has little positive impact on these low tech firms as far as technology diffusion is concerned. However, the more foreign direct invest in Indian footwear industry will have positive technology spillover on more technologically advanced and automated local shoe manufacturing. On the other hand, the decision of foreign firms to invest and produce shoes in India versus producing shoes in their own countries and exporting to India depends on Indian tariff rates and corporate tax rates on multinationals. Due to fixed cost of investing abroad, the most technologically advanced (which are also large) foreign firms can engage in foreign investment activities. Hence, more foreign investment in India may result in more diffusion of technology. Now suppose India experiences trade liberalization without liberalizing foreign investment. This one-dimensional type of liberalization may induce less foreign FDI and more import of shoes into India as foreign firms opt more for export to India and less FDI. In turn, this may weaken the competitiveness of high tech shoe makers relative to low tech ones through technology diffusion channel, ceteris paribus, resulting in protection of low-tech firms. The flip side of this finding is that if developing countries pursue protectionary trade policies in this kind of environment, such policies may fail to protect less technologically advanced local firms.

The literature on multinational corporations and FDI is rich and extensive. A branch of this literature, that is particularly related to our paper, studies the choice between export and foreign investment and its implications (e.g., see Batra and Ramachandran (1980) and more recently Helpman, Melitz, and Yeaple (2004) and Mukherjee (2011), among others).[1] Another strand of literature, to which our paper is related and contributes to, focuses on the effects that FDI has on diffusion of technology in developing countries (see Findlay (1978)).[2]In the current paper we build upon Dixit and Stiglitz (1977) and introduce a continuum of heterogeneous firms that produce a continuum of differentiated goods (see also Baldwin and Forslid (2010), Dinopoulos and Unel (2013), Helpman, Melitz, and Yeaple (2004), Melitz (2003), and Marjit and Kar (2012)).[3]Baldwin and Forslid (2010) also consider trade liberalization when firms are heterogeneous. In contrast to Baldwin and Forslid (2010), we study the implications of a policy mix of tariffs and taxes on multinationals vis-a-vis the choice between FDI and export to a developing country by foreign firms. We consider a case in which foreign firms compete with local firms in the developing country in a monopolistic competitive industry. We define firm heterogeneity on the basis of technological levels of firms as in Helpman, Melitz, and Yeaple (2004). We assume that all local firms in the developing country (which are also heterogeneous in their technological advancement) are technologically backward relative to foreign firms. Also, in contrast to both Helpman, Melitz, and Yeaple (2004) and Baldwin and Forslid (2010), we assume that FDI activities by foreign firms lead to diffusion of their superior technology in developing economies. There are empirical studies that support this hypothesis.[4] As it will be shown, this central feature of our model has crucial consequences on the theory of multinational corporations and its implications are essential in our understanding of the effects of trade liberalization for developing economies.

We first show that for a policy mix of import tariffs and tax on profits of multinational corporations imposed by the developing country, there exists an equilibrium whereby the more technologically advanced foreign firms will opt for FDI (i.e., become multinational) while the less technological advanced foreign firms will export their goods to the developing country (hereafter, we simply call these goods imported goods, from the point of view of the developing countries). Although this particular observation is similar to Helpman, Melitz, and Yeaple (2004) where they showed that the most productive firms in a country opt for FDI, while mid-level productive firms will export their goods and the least productive firm will serve the domestic market only, our focus is on policy mix for a developing country and the consequences of such a policy mix for a developing economy given the possibility of technology diffusion (absent in both Helpman, Melitz, and Yeaple (2004) and Baldwin and Forslid (2010)).

While a large portion of literature on theory of trade liberalization deals with unidimensional liberalization, most economies face many distortions.[5] As far as trade liberalization is concerned, it is crucial to consider the confluence of liberalization of trade and foreign investment. The combined influence of the trade distortions (such as tariffs) and capital market distortions (such as tax on FDI) is particularly amplified in our set up due to the technology diffusion effects. Studies on multiple distortions are also abundant and there is an extensive body of literature that focuses on various combination of commercial policies (for example, see Ruffin (1979)) as well as combination of commercial policies and other domestic taxes (for example, see Batra and Ramachandran (1980)).[6]Next, we show that trade liberalization has profound effects on FDI, the local firms, as well as the aggregate industry in developing countries. Most notably, as we stated earlier in this introduction, we show that trade liberalization by the developing country may lead to the protection of the most technologically backward local firms. The paradoxical aspect of this result is due to the generally held view that trade barriers are designed to protect local firms that would otherwise not survive, including the less technologically advanced firms. According to this widely held view, these firms are expected to be the first victim of trade liberalization. We will show that this need not be true, given that trade liberalization is coupled with liberalization of foreign investment. Finally, we study the effects of changes in a mix of trade policies on the welfare of a representative consumer.

Our paper has very important policy implications for firms in developing countries when facing trade liberalization. Empirical studies that address the effects of trade liberalization on local firms in developing countries are extensive. While the earlier studies present a mixed picture (for example, see Krishna and Mitra (1998)), more recent ones support the positive effects of trade liberalization on firm productivity. One of the best case studies for the effects of trade liberalization is India, which undertook vast liberalization reforms in 1990s. The empirical investigation of Indian experience is also rather rich (see Krishna and Mitra (1998), among others).

Our theoretical results begs for studying empirically the effects trade liberalization without FDI liberalization may have on developing economies. Again, India experience of 1990s may offer a good case study. Our results constitute a foundation for empirical re-examination of Indian liberalization of 1990s and effects of such reforms on firms with a wide range of technological heterogeneity.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 1 sets up a theory of FDI and multinational corporation for a developing country with a focus on a policy mix at the presence of technologically heterogeneous firms. We will present an extended model that incorporates technology diffusion in the developing economy in Section 3. Section 4 studies welfare consequences and Section 5 concludes that paper. All proofs for the results of Section 2–Section 4 are presented in Appendix A. We also study robustness of our results by constructing a more complex model and revisiting our results in Appendix B.

2 The Setup

Consider a developing economy with a possible range of differentiated goods denoted by

where

where

where

Similarly, the equilibrium expenditure for any good

where

Assume that all goods with

where

where

Following eq. (6), it can be shown that profit for firm

where

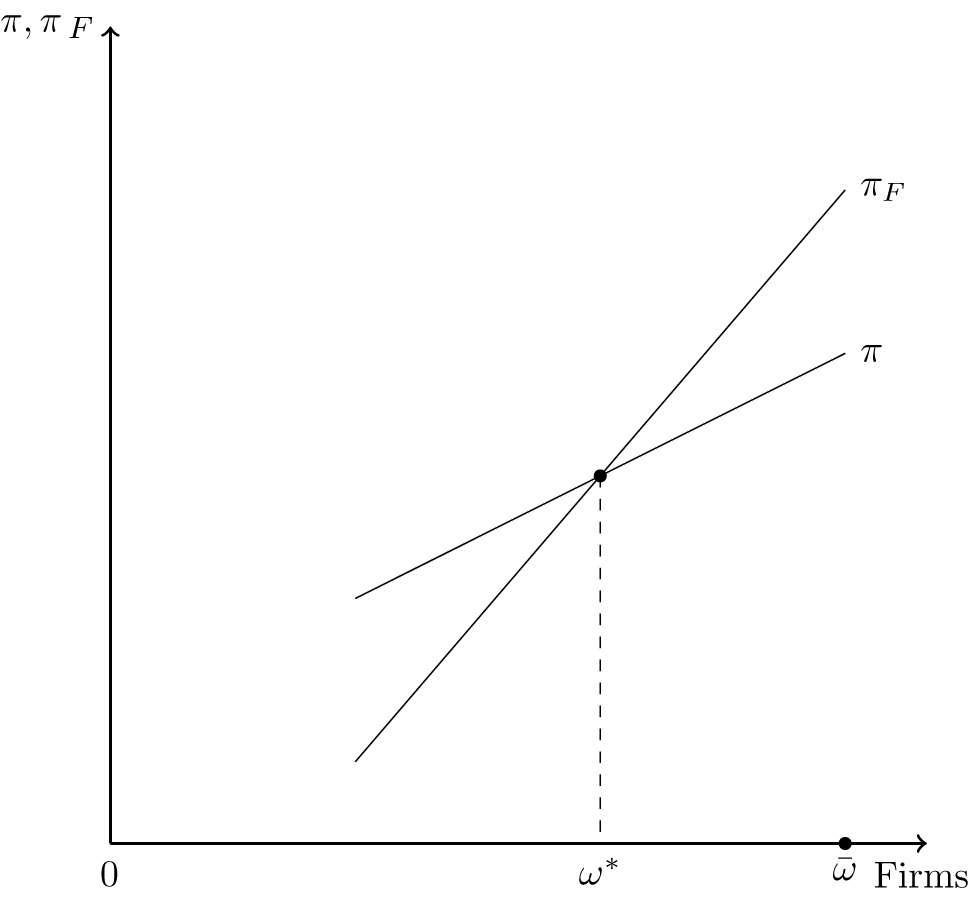

Proposition 1.

Assume that

Figure 1 shows the result of Proposition 1. For the right combination of taxes and the fixed cost of FDI, we will have an interior solution. If

FDI vs. imports.

As discussed above, both tariff and tax rates are crucial in the decision by foreign firms on their choice of FDI vis-a-vis import. Given that the result of Proposition 1 holds, that is, the goods produced by the less technologically advanced foreign firms are imported by our developing economy while more technologically advanced foreign firms produce their goods through FDI in the developing country, it is interesting to derive the combination

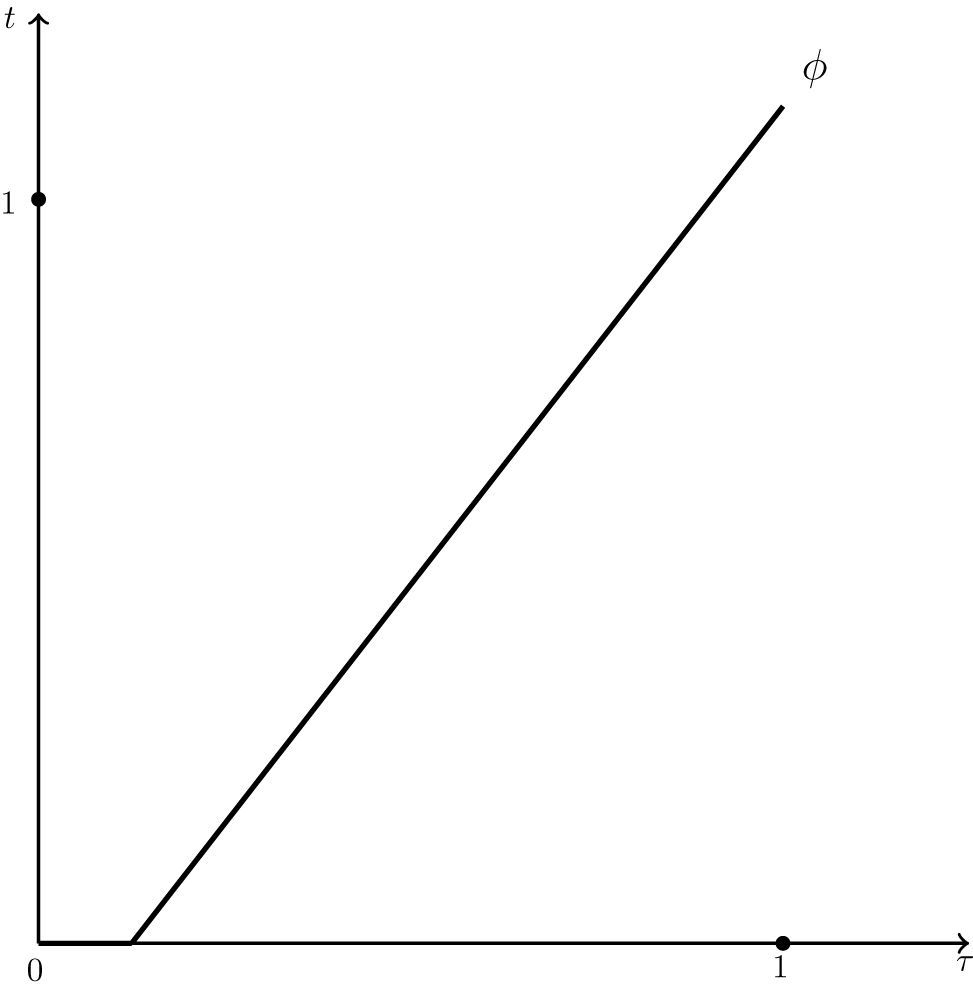

Proposition 2.

The above result formally highlights a relationship between profit tax rate on multinational corporations with FDI activities in the developing countries and the rate of tariffs. Since profit tax, tariffs and firm technological heterogeneity are the only factors that influence a firm’s decision on FDI activities versus import, it only makes sense that a non-decreasing relationship must exist between the profit tax rate on multinationals and the tariff rates that keep the balance of FDI vis-a-vis imports unchanged. Consider a firm that produces the marginal good

Relationship between tariff and FDI tax when

3 Technology Diffusion

Multinational corporations and their transnational investments have been credited for the rapid diffusion of new technologies. In this section we turn to the issue of how FDIs by multinational corporations affect a developing economy. In formulating the channel through which technology diffuses, we take the view that the spread of technology depends on proportion of the firms within the industry that already have adapted the new technology.[14] In our framework, we assume that multinational corporations use superior technologies, as formulated in the preceding section. Recall from the previous section that we assumed the local developing country firms are less technologically advanced than foreign firms and we showed that, among these more technological advanced foreign firms, the firms that engage in FDI activities are even more technologically advanced than those foreign firms that produce their goods abroad and export them to the developing country.

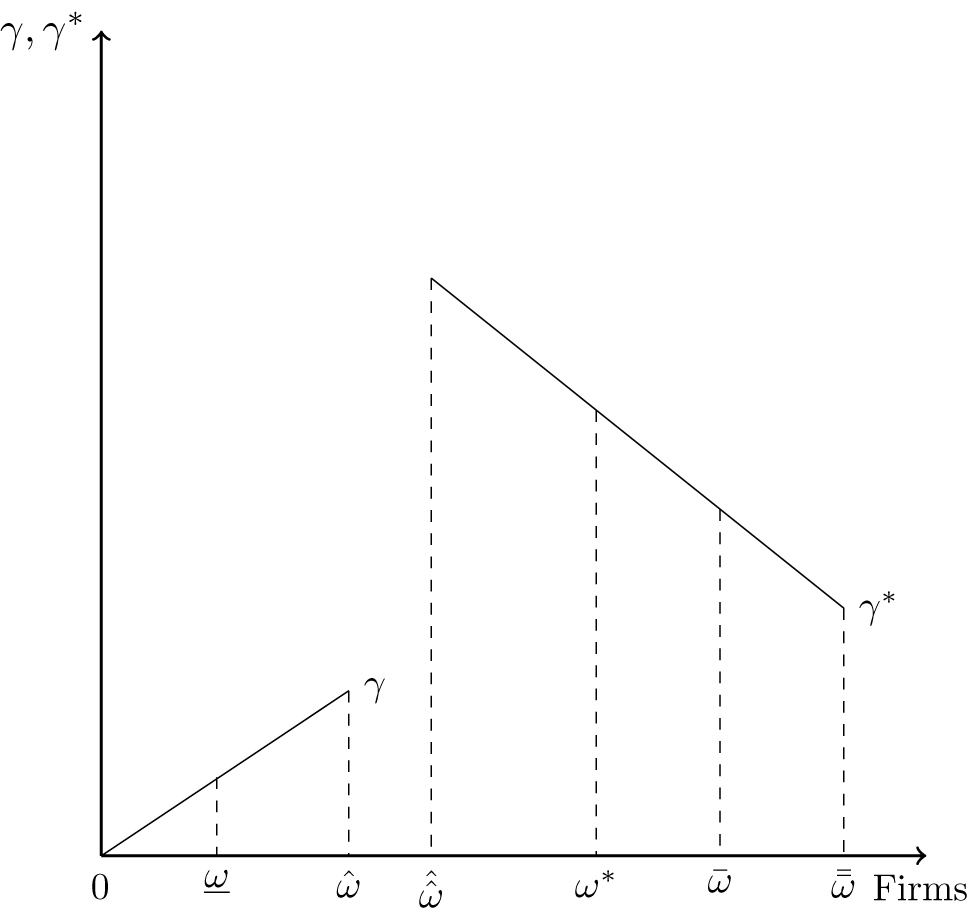

Hence, the spread of technology in the industry depends on the proportion of multinational corporations in the industry to all firms, denoted by

It is straightforward to see that Propositions 1 and 2 hold under the presence of technological diffusion we introduced in this section. That is, it is plausible in our model that both FDI activities and imports take place and that the relationship between tariff rate and FDI tax rate is non-negative (in particular, such a relationship is strictly positive for all

A change in the balance of FDI versus imports have consequences for the developing economy. Apart from the standard arguments in the literature with regard to commercial policy changes, our economy will also be influenced via the effect trade and foreign investment policy mix has on FDI balance vs. imports and thus a change in

Proposition 3

If trade liberalization is not matched with FDI, it increases the aggregate industry price. Moreover, such trade liberalization lowers the intra-industry relative price of the home marginal firm if

Intuitively, a reduction in trade barriers alone (i.e, without lowering barriers on FDI) will increase imports and reduce FDIs. As the level of FDI falls, technological diffusion will be restrained. This will have a negative impact on all local firms. However, the more technologically advanced firms will be affected more. The aggregate industry price rises. Since less technology diffusion results in a fall in productivity of all local firms which in turn leads to an increase in their prices. Thus, the aggregate industry price must rise. It is useful to highlight the channel through which the aggregate price will rise with trade liberalization of the sort we present here. In other words, trade liberalization without lowering taxes on FDI will encourage (discourage) import of foreign varieties (FDI), which lowers

It is widely argued in policy circles that trade liberalization will in general (and especially in the developing countries) eliminate marginal firms (i.e., firms that barely can survive given the presence of some sort of protectionary trade policies). Examples of these marginal firms are infant, old and dying firms, and technologically backward firms. Some policy makers argue passionately against trade liberalization by appealing to these cases, while some advocate this view by offering economic analysis that supports such a position. Even the main stream trade theorists admit that such firms will disappear within the paradigm of standard trade theory, but they argue for trade liberalization from the stand view of overall welfare and efficiency. In this paper we offer a different point of view, formally stated by the following proposition.

Proposition 4

Unilateral trade liberalization alone (without foreign investment liberalization) leads to the protection of the least technologically advanced firms if

According to the trade theory literature, trade liberalization has adverse effect on small and less productive local firms in importable sector. The above result presents a possibility that this may not be the case and that trade liberalization can indeed lead to the protection of technologically backward (and less productive) local firms. That is, this policy mix in a way shields the least technologically advanced local firm from foreign competition as it improves its competitive position within the industry. While this result may seem peculiar at the first sight, it is intuitive in the context of our theory and provides a deep insight. Since we have assumed firm technological heterogeneity in our model, the effect of liberalization differs across local firms. If trade liberalization is not coupled with liberalization FDI, the change in policy mix will encourage imports and discourage FDI. A reduction in FDI adversely impact transfer of technology from developed to the developing country. Since local firms are heterogeneous in their technology level, the adverse impact will differ across these local firms. On the other hand, it is also reasonable to assume that more technologically advance local firms are the main beneficiary of technology diffusion (i.e.,

This type of one-dimensional liberalization also affects the range of varieties that local firms produce. Recall that the marginal (low tech) firm that earns zero profit before the policy change will experience an increase. Its profit will be greater than zero as a result of this policy change and it will no longer be a marginal firm. This implies that the index of marginal good/firm falls. That is, new local variety/firms enter the market. Thus, we have the following corollary.

Corollary 5

Suppose that trade liberalization is not coupled with liberalization of FDI. Then, such type of trade liberalization will increase the number of local goods if

4 Welfare Analysis

The impact of the interaction between trade liberalization and foreign investment policy, given the presence of technology diffusion channel of the type we considered here, on welfare is another interesting issue that we could address within the context of our model.[20] First assume that a developing economy liberalizes trade in conjunction with foreign investment liberalization. More specifically, assume that these dual-liberalization policies take place along the curve

To see the effect of a reduction in trade barriers (i.e., an increase

Proposition 6.

Liberalizing trade without liberalization of FDI will lower welfare of the representative consumer in the developing economy.

Another related question that begs for an answer is to ask under what policy scenario welfare improvement can be guaranteed? We claim that welfare of the representative consumer in the developing country will unambiguity increase if trade liberalization is accompanied with sufficient foreign investment subsidies. At this point in the paper the rationale should be clear. Recall from Proposition 2 that

5 Conclusion

In this paper we have explored the interaction between trade liberalization and liberalization of FDI by a developing country and its effects on technology diffusion. One of the fundamental differences between developing and developed economies is that the developed countries are more technologically advanced. It has been observed that the activities of multinational corporations in developing countries would lead to spread of technology in these countries. We have formalized this observation in our analysis and studied how trade and FDI policies interact at the presence of technology diffusion.

We formulated a monopolistically competitive market in a developing country that is populated by a continuum of foreign (developed world) and local firms. We assumed that all these firms are technologically heterogeneous, all local firms are less technologically advanced than foreign firms, and that the operation of foreign firms in the developing economy leads to technology diffusion. We showed that there exists a policy mix of tariffs and foreign direct investment tax at which among the technologically superior foreign firms the more technologically advanced ones will engage in foreign direct investment in the developing country while others will opt to produce their goods abroad (their home country) and export them to the developing countries. This gives rise to endogenously determined (emerged) multinational corporations. More importantly, we showed that trade liberalization alone (i.e., without liberalization of foreign investment) by a developing country can lead to protection of the most technologically backward local firms. We also showed that such type of one dimensional liberalization is welfare reducing.

Both of these results have important policy implications for developing economies. First, the impacts of trade liberalization without liberalizing FDI on local firms depend on pattern of diffusion. We show that the less technologically advanced local firms (more often observed to be smaller firms) can be protected when a developing country lowers trade barriers if foreign direct investment is not liberalized. Given that firms in an industry are technologically heterogeneous and the pattern of technology diffusion is sufficiently biased toward more technologically advanced local firm, then trade liberalization without FDI liberalization can strengthen the competitive position of less advanced local firms within the industry and lead to their protection. Second, we also showed that trade liberalization without FDI liberalization by developing countries may paradoxically lower the welfare of the representative consumer when firms are technologically heterogeneous.

Our results open multiple avenues for empirical research as it is interesting to test some of the hypotheses and results introduced in this paper. For example, one can study the pattern of technology diffusion in developing countries and test whether it is in fact biased toward more advanced local firms. As another example, one can study whether the presence of multinational has significant effect on diffusion of technology in developing countries. A more elaborate empirical research may be able to isolate the effects of trade liberalization and liberalization of FDI, and their interaction, on an industry with firms that are technologically heterogeneous in a developing country. In addition to these potential econometric studies, an empiricist may use simulation and calibrate some of the crucial parameters of our model.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Eric Bond, Ron Jones and the participants of WEAI conference for their comments and suggestions. We are also grateful to two anonymous referees and the editor of this journal for their insightful comments that improved this version significantly. Reza Oladi acknowledges financial support from Utah Agricultural Experiment Station. The Usual caveat applies.

Appendix A: Proofs

Proof of Proposition 1

First note a necessary condition for import to take place is

Recall that

Proof of Proposition 2

For the marginal firm

Differentiating eq. (9), we obtain

Proof of Proposition 3

First, re-write no-entry-exit (zero-profit) condition as:

Differentiating eqs (2), (10) as well as the definition of

where

Proof of Proposition 4

It follows from eq. (7) that profit for the marginal local firm is given by:

Differentiate eq. (16) with respect to

Next, using our earlier assumption of unit elasticity of industry aggregate demand, zero-profit condition of our (initial) marginal firm, as well as differentiating the definition of intra-industry price of the local marginal firm, we simplify eq. (17) to:

Recall from zero-profit condition of home marginal firm we can obtain

Proof of Corollary 1

Recall eq. (14) in Proof of Proposition 3. It implies that the bracketed term will be negative if

Proof of Proposition 5

Directly follows from

Appendix B: An Alternative Complex Model

In this appendix we will show that the assumption of not having a zero-profit (marginal) foreign firm has little consequence on our results and that our core argument remains valid if we relax this assumption. Let the set of local goods be

Technology levels for foreign and local firms.

Proposition 7

A decrease in tariff rate without a change in the tax rate on multinational corporations will increase the aggregate industry price.

Proof

The aggregate price can be written as:

By differentiating eq. (19), home and foreign zero-profit conditions for marginal firms, as well as the definition of intra-industry price for the home marginal firm, we obtain:

where

where

As we observed throughout the paper, the relative intra-industry price for each firm is a determining factor for its viability since it defines the firm’s intra-industry competitive position. Our main result regarding the fate of technologically backward local firms in a developing country when faced with trade liberalization (without liberalizing FDI) also hinges on such firms’ intra-industry relative prices. Therefore, it is important to revisit the effect of liberalization on intra-industry relative price within our more general model. The following proposition addresses this robustness.

Proposition 8

Suppose trade liberalization is not matched with FDI liberalization in a developing country. Then, such type of trade liberalization will lower the intra-industry relative price of the home marginal firm if

Proof

By solving the system of eqs (20)–(23) for

Recall from Proof of Proposition 6 that

Since intra-industry relative price of the most technologically backward firm falls if

Finally, it is interesting to see whether the result of Proposition 5 is robust. Proposition 6 shows that the industry aggregate price rises as a result of trade liberalization without liberalizing foreign investment. As stated earlier in the paper, the driving force behind this unconventional result is the effect that ensuing change in FDI balance has on diffusion of technology to the local firms. Therefore, an increase in industry aggregate price will result in loss in welfare of the representative consumer, as stated in Proposition 5.

References

Anwar, S. 2009. “Sector Specific Foreign Investment, Labour Inflow, Economies of Scale and Welfare.” Economic Modelling 26: 626–630.10.1016/j.econmod.2009.01.009Suche in Google Scholar

Baldwin, R. E., and R. Forslid. 2000. “Trade Liberalisation and Endogenous Growth: A Q-theory Approach.” Journal of International Economics 50: 497–517.10.1016/S0022-1996(99)00008-2Suche in Google Scholar

Baldwin, R. E., and R. Forslid. 2010. “Trade Liberalization with Heterogeneous Firms.” Review of Development Economics 14: 161–176.10.1111/j.1467-9361.2010.00545.xSuche in Google Scholar

Batra, R., and R. Ramachandran. 1980. “Multinational Firms and the Theory of International Trade and Investment.” American Economic Review 70: 278–290.Suche in Google Scholar

Beladi, H., and R. Oladi. 2011. “An Elementary Proposition on Technical Progress and Non-traded Goods.” Journal of Mathematical Economics 47: 68–71.10.1016/j.jmateco.2011.01.002Suche in Google Scholar

Beladi, H., and R. Oladi. 2016. “On Mergers and Agglomeration.” Review of Development Economics 20: 345–358.10.1111/rode.12223Suche in Google Scholar

Branstetter, L., and K. Saggi. 2011. “Intellectual Property Rights, Foreign Direct Investment and Industrial Development.” Economic Journal 121: 1161–1191.10.3386/w15393Suche in Google Scholar

Chakrabarti, A. 2003. “A Theory of the Spatial Distribution of Foreign Direct Investment.” International Review of Economics and Finance 12: 149–169.10.1016/S1059-0560(02)00111-9Suche in Google Scholar

Chakrabarti, A. 2001. “The Determinants of Foreign Direct Investments: Sensitivity Analyses of Cross-Country Regressions.” Kyklos 54: 89–114.10.1111/1467-6435.00142Suche in Google Scholar

Chao, C. -C., and E. S. H. Yu. Domestic Equity Controls of Multinational Enterprises. The Manchester School 2000:321–330. 68.10.1142/9781783264797_0011Suche in Google Scholar

Chao, C. -C., and E.S.H. Yu. Foreign-Investment Tax and Tariff Policies in Developing Countries. Review of International Economics 1997:47–62. 5.10.1111/1467-9396.00038Suche in Google Scholar

Dinopoulos, E., and B. Unel. 2013. “A Simple Model of Quality Heterogeneity and International Trade.” Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 37: 68–83.10.1016/j.jedc.2012.07.007Suche in Google Scholar

Dixit, A. K., and J. E. Stiglitz. 1977. “Monopolistic Competition and Optimum Product Diversity.” American Economic Review 67: 297–308.Suche in Google Scholar

Findlay, R. 1978. “Relative Backwardness, Direct Foreign Investment, and the Transfer of Technology: A Simple Dynamic Model.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 92: 1–16.10.2307/1885996Suche in Google Scholar

Business, Fox Could Free-trade Mean Bad News for Small Business? 2013, http://www.foxbusiness.com/features/2013/07/10/could-free-trade-mean-bad-news-for-small-business.html.Suche in Google Scholar

Glass, A. J., and K. Saggi. 2002. “Intellectual Property Rights and Foreign Direct Investment.” Journal of International Economics 56: 387–410.10.1016/S0022-1996(01)00117-9Suche in Google Scholar

Grieben, W. -H., and F. Sener. Globalization, Rent Protection Institutions, and Going Alone in Freeing Trade. European Economic Review 2009:1042–1065. 53.10.1016/j.euroecorev.2009.04.003Suche in Google Scholar

Helpman, E., M. J. Melitz, and S. R. Yeaple. 2004. “Export versus FDI with Heterogeneous Firms.” American Economic Review 94: 300–316.10.1257/000282804322970814Suche in Google Scholar

Jones, R. W. 1967. “International Capital Movements and the Theory of Tariffs and Trade.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics: 81: 1–38.10.2307/1879671Suche in Google Scholar

Jones, R. W., and S. Marjit. 2001. “The Role of International Fragmentation in the Development Process.” American Economic Review 91: 363–366.10.1142/9789813200678_0015Suche in Google Scholar

Krishna, P., and D. Mitra. 1998. “Trade Liberalization, Market Discipline and Productivity Growth: New Evidence from India.” Journal of Development Economics 56: 447–462.10.1016/S0304-3878(98)00074-1Suche in Google Scholar

Krugman, P. 1980. “Scale Economies, Product Differentiation, and the Pattern of Trade.” American Economic Review 70: 950–959.10.7551/mitpress/5933.003.0005Suche in Google Scholar

Mansfield, E. 1961. “Technical Change and the Rate of Imitation.” Econometrica 29: 741–766.10.2307/1911817Suche in Google Scholar

Marjit, S. 1991. “Incentives for Cooperative and Non-cooperative R and D in Duopoly.” Economics Letters 37: 187–191.10.1016/0165-1765(91)90129-9Suche in Google Scholar

Marjit, S., and S. Kar. 2012. “Firm Heterogeneity, Informal Wage and Good Governance.” Review of Development Economics 16: 527–539.10.1111/rode.12002Suche in Google Scholar

Melitz, M. J. 2003. “The Impact of Trade on Intra? Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity.” Econometrica 71: 1695–1725.10.3386/w8881Suche in Google Scholar

Mukherjee, A. 2011. “Competition, Innovation and Welfare.” Manchester School 79: 1045–1057.10.1111/j.1467-9957.2010.02184.xSuche in Google Scholar

Mukherjee, A. 2010. “A Note on Firm-Productivity and Foreign Direct Investment.” Economics Bulletin 30: 2107–2111.Suche in Google Scholar

Mukherjee, A. 2006. “Patents and R&D with Imitation and Licensing.” Economics Letters 93: 196–201.10.1016/j.econlet.2006.05.002Suche in Google Scholar

Oladi, R. 2005. “Stable Tariffs and Retaliations.” Review of International Economics 13: 205–215.10.1111/j.1467-9396.2005.00499.xSuche in Google Scholar

Oladi, R., H. Beladi, and N. Chau. 2008. “Multinational Corporations and Export Quality.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 65: 147–155.10.1016/j.jebo.2005.08.004Suche in Google Scholar

Pi, J., and Y. Zhou. 2014. “Foreign Capital, Public Infrastructure, and Wage Inequality in Developing Countries.” International Review of Economics & Finance 29: 195–207.10.1016/j.iref.2013.05.012Suche in Google Scholar

Ruffin, R. J. 1979. “Border Tax Adjustments and Countervailing Duties.” Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 115: 351–355.10.1007/BF02696334Suche in Google Scholar

© 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Economic Conditions at School Leaving and Sleep Patterns Across the Life Course

- Retirement Decisions in Recessionary Times: Evidence from Spain

- The Legal Grounds of Irregular Migration: A Global Game Approach

- Banks Restructuring Sonata: How Capital Injection Triggered Labor Force Rejuvenation in Japanese Banks

- Origins of Adulthood Personality: The Role of Adverse Childhood Experiences

- Monopolistic Competition and Exclusive Quality

- Technology Diffusion and Trade Liberalization

- Letters

- Information Acquisition and Disclosure of Environmental Risk

- Fiscal Decentralization and Public Spending: Evidence from Heteroscedasticity-Based Identification

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Economic Conditions at School Leaving and Sleep Patterns Across the Life Course

- Retirement Decisions in Recessionary Times: Evidence from Spain

- The Legal Grounds of Irregular Migration: A Global Game Approach

- Banks Restructuring Sonata: How Capital Injection Triggered Labor Force Rejuvenation in Japanese Banks

- Origins of Adulthood Personality: The Role of Adverse Childhood Experiences

- Monopolistic Competition and Exclusive Quality

- Technology Diffusion and Trade Liberalization

- Letters

- Information Acquisition and Disclosure of Environmental Risk

- Fiscal Decentralization and Public Spending: Evidence from Heteroscedasticity-Based Identification