Abstract:

We develop a stylized theoretical model showing that countercyclical transfers from a wealthy donor to a poorer recipient generate a signal of altruistic donor motivation. Applying the model to OECD foreign aid (ODA) data we find the signal present in approximately one-sixth of a large set of donor–recipient pairs. We then undertake two out-of-model exercises to validate the signal: a logit regression of signal determinants and the growth effects of ODA from signal-positive pairs are compared to non-signal bearers. The logit indicates our signal meaningfully distinguishes donor–recipient pairs by characteristics typically associated with altruism. The growth exercise shows ODA from signal bearers displays stronger reverse causation and more positive long-run effects. Beyond foreign aid, our signal of altruistic motivation may be applicable to a wide range of voluntary transfers.

Acknowledgements

We thank Christopher Kilby, Eric Bond, Stephen Smith, James Foster, Jon Rothbaum, Benedikt Rydzek, Sam Bazzi, and other seminar participants at Vanderbilt University, George Washington University, Villanova University, the 34th Annual Econometric Society Meetings in Brazil, the 9th Annual Conference on Economic Growth and Development at Indian Statistical Institute, LuBra-Macro Conference in Recife, and the XIV AEEFI Conference on International Economics for insightful comments and suggestions. We also thank Aaron Johnson and Hongwei Song for research assistance. Arilton Teixeira thanks CNPq (Brazilian National Research Council) for financial support. The usual disclaimers apply.

References

Addison, T., and F. Tarp. 2014. “Aid Policy and the Macroeconomic Management of Aid.” World Development 69 : 1–130.10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.02.009Suche in Google Scholar

Alesina, A., and D. Dollar. 2000. “Who Gives Foreign Aid to Whom and Why?” Journal of Economic Growth 5 (1): 33–63.10.3386/w6612Suche in Google Scholar

Andreoni, J 1989. “Giving with Impure Altruism: Applications to Charity and Ricardian Equivalence.” The Journal of Political Economy 97 (6): 1447–1458.10.1086/261662Suche in Google Scholar

Andreoni, J 1990. “Impure Altruism and Donations to Public Goods: A Theory of Warm-Glow Giving.” The Economic Journal 100 (401): 464–477.10.2307/2234133Suche in Google Scholar

Arellano, C., A. Bulb, T. Laneb, and L. Lipschitzb. 2009. “Dynamic Implications of Foreign Aids and Its Variability.” Journal of Development Economics 88 (01): 87–102.10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.01.005Suche in Google Scholar

Bearce, D. H., and D. C. Tirone. 2010. “Foreign Aid Effectiveness and the Strategic Goals of Donor Governments.” The Journal of Politics 72 (03): 605–615.10.1017/S0022381610000204Suche in Google Scholar

Berthélemy, J.-C 2006. “Bilateral Donors Interest vs. Recipients Development Motives in Aid Allocation: Do All Donors Behave the Same?” Review of Development Economics 10 (02): 179–194.10.1111/j.1467-9361.2006.00311.xSuche in Google Scholar

Berthélemy, J.-C., and A. Tichit. 2004. “Bilateral Donors Aid Allocation Decisions – A Three Dimensional Panel Analysis.” International Review of Economics and Finance 13 (03): 253–274.10.1016/j.iref.2003.11.004Suche in Google Scholar

Blackburn, D. W., and A. Ukhov. 2008. “Individual vs. Aggregate Preferences: The Case of a Small Fish in a Big Pond.” Working paper.10.2139/ssrn.941126Suche in Google Scholar

Bourguignon, F., and M. Sundberg. 2007. “Aid Effectiveness: Opening the Black Box.” American Economic Review 97 (02): 316–321.10.1257/aer.97.2.316Suche in Google Scholar

Bul, A., and A. J. Hamann. 2008. “Volatility of Development Aid: From the Frying Pan into the Fire?” World Development 36 (10): 2048–2066.10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.02.019Suche in Google Scholar

Burnside, C., and D. Dollar. 2000. “Aid, Policies, and Growth.” American Economic Review 90 (4): 847–868.10.1257/aer.90.4.847Suche in Google Scholar

Chong, A., and M. Gradstein. 2008. “What Determines Foreign Aid? The Donors’ Perspective.” Journal of Development Economics 81 (01): 1–13.10.1016/j.jdeveco.2007.08.001Suche in Google Scholar

Clemens, M. A., S. Radelet, R. R. Bhavnani, and S. Bazzi. 2012. “Counting Chickens When They Hatch: Timing and the Effects of Aid on Growth.” The Economic Journal 122 : 590–617. ((June)):.10.1111/j.1468-0297.2011.02482.xSuche in Google Scholar

Cliff, M. T. 2003 GMM and MINZ Program Libraries for Matlab.”. Unpublished Manuscript.Suche in Google Scholar

Dabla-Norris, E., C. Minoiu, and L.-F. Zanna. 2010. “Business Cycle Fluctuations, Large Shocks and Development Aid: New Evidence.” IMF Working Paper.10.5089/9781455209408.001Suche in Google Scholar

De Mesquita, B. B., and A. Smith. 2007. “Foreign Aid and Policy Concessions.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 51 (01): 251–284.10.1177/0022002706297696Suche in Google Scholar

Dreher, A., V. Z. Eichenauer, and K. Gehring. 2014. “Geopolitics, Aid and Growth.” Cepr discussion paper no. dp9904.10.2139/ssrn.2290915Suche in Google Scholar

Dreher, A., P. Nunnenkamp, and R. Thiele. 2008. “Does US Aid Buy UN General Assembly Votes? A Disaggregated Analysis.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 36 (1/2): 139–164.10.1007/s11127-008-9286-xSuche in Google Scholar

Dudley, L., and C. Montmarquette. 1976. “A Model of the Supply of Bilateral Foreign Aid.” American Economic Review 66 (01): 132–142.Suche in Google Scholar

Gravier-Rymaszewska, J. 2012. “How Aid Supply Responds to Economic Crises: A Panel VAR Approach.” Wider Working Paper 2012/25.Suche in Google Scholar

Hoeffler, A., and V. Outram. 2011. “Need, Merit, or SelfInterest What Determines the Allocation of Aid?” Review of Development Economics 15 (02): 237–250.10.1111/j.1467-9361.2011.00605.xSuche in Google Scholar

Kilby, C., and A. Dreher. 2010. “The Impact of Aid on Growth Revisited: Do Donor Motives Matter?” Economics Letters 107 (03): 338–340.10.1016/j.econlet.2010.02.015Suche in Google Scholar

Maizels, A., and M. K. Nissanke. 1984. “Motivations for Aid to Developing Countries.” World Development 12 (09): 879–900.10.1016/0305-750X(84)90046-9Suche in Google Scholar

McKinley, R. D., and R. Little. 1979. “The US Aid Relationship: A Test of the Recipient Need and the Donor Interest Model.” Political Studies 27 (02): 236–250.10.1111/j.1467-9248.1979.tb01201.xSuche in Google Scholar

Packenham, R. A 1966. “Foreign Aid and the National Interest.” Midwest Journal of Political Science 10 (02): 214–221.10.2307/2109149Suche in Google Scholar

Pallage, S., and M. A. Robe. 2001. “Foreign Aid and the Business Cycle.” Review of International Economics 09 (04): 641–672.10.1111/1467-9396.00305Suche in Google Scholar

Radelet, S. 2006. “A Primer on Foreign Aid.” Center for Global Development Working Paper Number 92.10.2139/ssrn.983122Suche in Google Scholar

Rajan, R., and A. Subramanian. 2008. “Aid and Growth: What does the Cross-Country Evidence Really Show?” Review of Economics and Statistics 90 (4): 643–665.10.3386/w11513Suche in Google Scholar

Schraeder, P. J., S. W. Hook, and B. Taylor. 1998. “Clarifying the Foreign Aid Puzzle: A Comparison of American, Japanese, French, and Swedish Aid Flows.” World Politics 50 (02): 294–323.10.1017/S0043887100008121Suche in Google Scholar

Temple, J. R.“Aid and Conditionality.”, edited by D. Rodrik, and M. Rosenzweig, In Handbook of Development EconomicsElsevier., chap. 67 2010. 4415–4523.10.1016/B978-0-444-52944-2.00005-7Suche in Google Scholar

Trumbull, W. N., and H. J. Wall. 1994. “Estimating Aid-Allocation Criteria with Panel Data.” The Economic Journal 104 (425): 876–882.10.2307/2234981Suche in Google Scholar

Werker, E. D., F. Z. Ahmed, and C. Cohen. 2009. “How is Foreign Aid Spent? Evidence from a Natural Experiment.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 1 (2): 225–244.10.1257/mac.1.2.225Suche in Google Scholar

Wik, M., T. A. Kebede, O. Bergland, and S. T. Holden. 2004. “On the Measurement of Risk Aversion from Experimental Data.” Applied Economics 36 (21): 2443–2451.10.1080/0003684042000280580Suche in Google Scholar

Yesuf, M., and R. A. Bluffstone. 2009. “Poverty, Risk Aversion, and Path Dependence in Low-Income Countries: Experimental Evidence from Ethiopia.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 91 (04): 1022–1037.10.1111/j.1467-8276.2009.01307.xSuche in Google Scholar

Younas, J 2008. “Motivation for Bilateral Aid Allocation: Altruism or Trade Benefits.” European Journal of Political Economy 24 (03): 661–674.10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2008.05.003Suche in Google Scholar

Appendix

A: Donor and Recipient Countries in Sample

The

The

B: Theoretical Elements

B.1 The Model

In each period, the donor country planner solves a static utility maximization problem to determine how much ODA to transfer to each of the

Let

The donor resource constraint links total absorption,

where

In the baseline model we adopt a log-additive utility function

in which total utility

We assume that the total gain function

The gain from each individual transfer,

The first component,

As implied above, we assume

Empirically, we will also allow the gain functions components to be affected by pair-specific shift factors,

The donor’s maximization problem is completed with the budget constraint of the recipient as seen from the donor’s perspective:

Equation (A4) makes explicit the relationship between

Consistent with clear empirical reality, we assume that constraint (A2) is never binding for any donor. Therefore, the local interior first-order necessary conditions of the donors problem are satisfied where the marginal utility of donor “own-consumption” is equal to the marginal gain (from the total gain function) for each of the recipients. Indirect effects of transfers across recipients that would be conveyed by the shadow price of constraint (A2), were it binding, are absent. Hence, we can obtain the local qualitative theoretical signal of altruism utilizing the ODA decision to a single representative recipient,

where, in order to simplify notation, let

The first-order condition with respect to the generic donation

which is eq. [2] in the main text.

B.2 Alternative Utility Functional Forms

This section describes more in detail the CARA version of the model used for the robustness exercise in Section D.1 and the results for the CRRA version. The basic assumptions and results of the paper hold for these two versions too with the only exception that we start directly from the additive functional form in (A5) instead of the log-additive function in (A3). In particular, the countercyclical-altruism condition [9] is not affected by the choice of the functional form. In eq. (A5), it is reasonable to assume in this case that

In the CARA version of the econometric model, we assume negative exponential functional forms for the own-consumption utilities

where

where

where

and

The CRRA version of the econometric model can be derived starting from constant relative risk aversion own-consumption utility functions

and following similar steps. As mentioned below, the CRRA specification is more troublesome than the CARA in the sense that the estimation of the model is more sensitive to the small variability of the ODA flows, especially when multiple controls are included in the regression equations. In particular, the number of pairs that empirically satisfy the countercyclical-altruism test drops to

C: ODA Accounting, Data, and Econometric Details

C.1 Dataset

Letting

National account data is drawn from the Penn World Tables dataset PWT 7.1 while ODA data is from the OECD DAC Aid Statistics dataset; PPP per-capita GDP is drawn from rgdpl in PWT. We use net ODA disbursements for

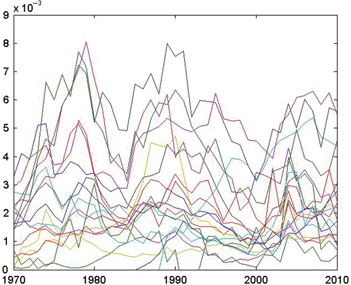

Total ODA disbursements as a ratio of GDP for the

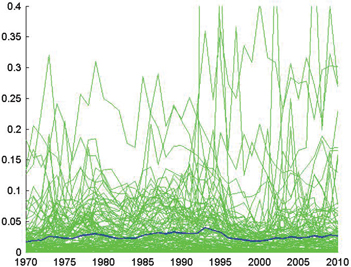

Figure A2 shows ODA relative to GDP for all

Total ODA Disbursements as a ratio of GDP for all recipients – sample

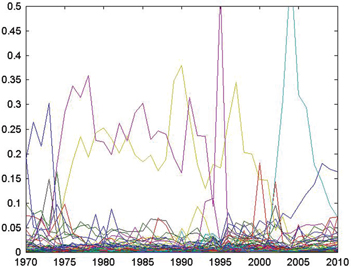

Shares of US ODA disbursements by recipient from

C.2 Estimation Details

In the GMM estimation, the optimal weighting matrix is computed using a Bartlett kernel with a Newey-West fixed bandwidth. The model is estimated in Matlab, using a modification of the toolbox developed by Cliff (2003)

which accommodates equation-specific orthogonality conditions. One estimation issue is that, for some pairs, it may be difficult to distinguish eqs (18) and (19) when

In the GMM, the asymptotic distribution of

where

in which

D: Robustness Checks

The assumptions made in the empirical implementation of the model warrant additional attention since the results of the paper could have been driven by implausible fortunate coincidences. We therefore conduct a series of robustness checks to address two main concerns. The first checks are sensitivity analyses of the role of the controls at the estimation stage in light of the small variability in ODA that, in some cases, affects eqs [18] and [19]. The second set of robustness checks explore how the parameter estimates and the set of pairs displaying the countercyclical-altruism signal change with alternative utility functional forms.

D.1 Robustness to the Model Specification

Regarding the control variables we find that increasing the number of controls reduces the number of pairs displaying the countercyclical-altruism signal for all specifications explored. For instance, going from zero controls to two controls in our baseline specification reduces the altruistic pairs from

We now turn to the choice of the functional forms. As an alternative to our baseline model of eq. (A5) we consider constant absolute risk aversion (CARA) own-consumption utility functions. The full description of the model under this different set of assumptions is given in Appendix B.[35] In order to avoid non-linear restrictions on the coefficients of the model, we keep the curvature parameters of the three functions separate from

The most interesting difference between the baseline model and the CARA specification is the higher number of countercyclical-altruistic pairs relative to the other countries for Luxembourg, Norway, and in part Finland as well. Our baseline specification reduces the Scandinavian countries’ signals and, in this sense, can be considered a more conservative choice. However, although the composition of the altruistic group changes somewhat with CARA, the output of the growth regressions for the basic CARA case reported in Table A1 and of the logit regressions reported in Table A3 does not differ from our baseline model. The fact that the quality of the signal is preserved across specifications provides further evidence that the theoretical model identifies a robust signal.

A final robustness feature worth noting concerns the theoretical model. In earlier stages of this work other versions of the theoretical model were explored. For instance, we developed models with linear direct returns from ODA in the donor’s budget constraint or returns proportional to the loss in utility of the donors. The basic countercyclical signal emerges from these formulations as well. The theoretical model presented herein is more general and more tightly linked to the estimation.

C.2 Robustness of the Results in Section 5

In this Appendix, we provide some robustness check of the two out-of-model exercises discussed in Section 5. We start estimating the growth regressions for two other specifications of our empirical altruism model, namely the baseline model with no controls and the CARA (with parameterization

The strength of the BD aid-growth relationship, compared to RS, is not surprising since the BD model generally yielded larger and more significant ODA-growth linkages. CL, for instance, can find significant effects of ODA on recipients’ growth only for early impact for the RS model. In our case, not even the early impact category provides particularly positive estimates. Finally, using quadratic ODA terms in the non-linear specification of the regression model does not improve the overall outlook of the results in Table A2. The coefficients change often sign across specifications with no particular regularity and the growth-ODA relation becomes convex with early impact aid. These results suggest that our signal effectively identify aid with more positive impact on growth only in the BD specification, which as we know estimates the effects of ODA conditional on the quality of the institutions of the recipient country.

Estimation of the growth regressions for the Burnside and Dollar (2000) (BD) model.

| Baseline – no controls: partitioned | Early impact | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.111 | |||||||

| (0.121) | |||||||

| 0.102 | |||||||

| (0.119) | |||||||

| 0.223 | 0.161 | 0.243 | 0.775 | 1.315 | 1.440 | ||

| (0.125)* | (0.159) | (0.264) | (0.324)** | (0.318)*** | (0.479)*** | ||

| 0.085 | 0.027 | 0.429 | 0.249 | 0.073 | –0.776 | ||

| (0.171) | (0.254) | (0.325) | (0.502) | (0.437) | (0.664) | ||

| −0.006 | −0.038 | −0.232 | −0.198 | ||||

| (0.015) | (0.015)** | (0.038)*** | (0.062)*** | ||||

| −0.020 | −0.013 | −0.034 | 0.025 | ||||

| (0.012)* | (0.017) | (0.041) | (0.051) | ||||

| Model | F.E. | F.E. | Diff. | F.E. | Diff. | F.E. | Diff. |

| Obs | 414 | 414 | 357 | 414 | 357 | 368 | 312 |

| 0.23 | 0.68** | 1.01*** | 1.17*** | ||||

| 0.37 | 0.21 | 0.01 | |||||

| CARA specification: partitioned | Early impact | ||||||

| 0.074 | |||||||

| (0.097) | |||||||

| 0.132 | |||||||

| (0.121) | |||||||

| 0.190 | 0.093 | 0.365 | 0.639 | 1.031 | 1.216 | ||

| (0.109)* | (0.129) | (0.249) | (0.302)** | (0.383)*** | (0.481)** | ||

| 0.110 | 0.113 | 0.408 | 0.348 | 0.373 | −0.495 | ||

| (0.164) | (0.237) | (0.287) | (0.454) | (0.393) | (0.739) | ||

| −0.014 | −0.030 | −0.179 | −0.176 | ||||

| (0.011) | (0.012)** | (0.053)*** | (0.058)*** | ||||

| −0.018 | −0.016 | −0.059 | 0.023 | ||||

| (0.010)* | (0.016) | (0.044) | (0.080) | ||||

| Model | F.E. | F.E. | Diff. | F.E. | Diff. | F.E. | Diff. |

| Obs | 414 | 414 | 357 | 414 | 357 | 368 | 312 |

| 0.33 | 0.57** | 0.81** | 0.99** | ||||

| 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.27 | |||||

Notes: The top panel reports the results with ODA donor partition between

Estimation of the growth regressions for the Rajan and Subramanian (2008)

(RS) model. ODA donor partition between

| Partitioned | Early impact | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.057 | 0.212 | |||||

| (0.135) | (0.165) | |||||

| −0.032 | 0.021 | |||||

| (0.109) | (0.154) | |||||

| 0.079 | 0.116 | 0.002 | 0.209 | |||

| (0.084) | (0.107) | (0.159) | (0.238) | |||

| 0.011 | 0.145 | 0.142 | 0.118 | |||

| (0.127) | (0.203) | (0.092) | (0.147) | |||

| Model | F.E. | F.E. | Diff. | F.E. | F.E. | Diff. |

| Obs | 384 | 387 | 310 | 383 | 335 | 270 |

Notes: The regression models are estimated either by including fixed effects (F.E.) or in first difference (Diff.); standard errors clustered at recipient level are reported in parentheses.

In Table A3 we present some robustness checks for the logit regression discussed in Section 5.1. We consider two alternative specifications: The baseline model with no controls and the main CARA functional specification (with parameterization

Logit model for alternative specification of the altruism model – odds ratios.

| Baseline – no controls | CARA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| consump. | 0.949 | 0.913 | 0.926 | 1.006 | 0.926 | 0.951 | 0.900 | 1.066 |

| (0.050)* | (0.616) | (0.004)*** | (0.975) | (0.013)** | (0.773) | (0.001)*** | (0.711) | |

| pop. | 0.983 | 0.825 | 0.988 | 0.884 | 0.971 | 0.772 | 0.976 | 0.828 |

| (0.121) | (0.066)* | (0.247) | (0.251) | (0.016)** | (0.031)** | (0.030)** | (0.112) | |

| democr. | 0.793 | 1.028 | 0.819 | 0.977 | 0.890 | 1.034 | 0.894 | 0.937 |

| (0.615) | (0.956) | (0.661) | (0.965) | (0.738) | (0.938) | (0.753) | (0.875) | |

| int. conflict | 1.170 | 1.210 | 1.073 | 1.091 | 1.354 | 1.402 | 1.203 | 1.239 |

| (0.464) | (0.379) | (0.733) | (0.675) | (0.130) | (0.127) | (0.340) | (0.296) | |

| ext. conflict. | 1.278 | 1.204 | 1.144 | 1.145 | 1.745 | 1.289 | 1.557 | 1.223 |

| (0.577) | (0.636) | (0.731) | (0.693) | (0.330) | (0.614) | (0.380) | (0.632) | |

| mortality | 1.005 | 1.719 | 1.005 | 1.510 | 1.005 | 1.866 | 1.004 | 1.679 |

| (0.076)* | (0.032)** | (0.131) | (0.105) | (0.112) | (0.012)** | (0.193) | (0.042)** | |

| colony | 1.600 | 1.302 | 1.577 | 1.515 | 1.097 | 0.917 | 1.045 | 1.040 |

| (0.021)** | (0.212) | (0.030)** | (0.045)** | (0.722) | (0.750) | (0.862) | (0.885) | |

| US influence | 0.837 | 0.671 | 0.808 | 0.778 | 0.733 | 0.628 | 0.688 | 0.719 |

| (0.718) | (0.418) | (0.661) | (0.615) | (0.588) | (0.380) | (0.504) | (0.536) | |

| JP influence | 1.651 | 1.757 | 1.370 | 1.597 | 2.513 | 2.949 | 2.122 | 2.739 |

| (0.353) | (0.321) | (0.563) | (0.422) | (0.073)* | (0.068)* | (0.139) | (0.090)* | |

| EU influence | 1.162 | 1.091 | 1.152 | 1.116 | 1.183 | 1.110 | 1.163 | 1.130 |

| (0.041)** | (0.093)* | (0.075)* | (0.044)** | (0.029)** | (0.056)* | (0.055)* | (0.022)** | |

| trade | 1.112 | 1.177 | 1.345 | 1.213 | ||||

| (0.472) | (0.002)*** | (0.037)** | (0.002)*** | |||||

| milit. G | 0.917 | 0.869 | 0.939 | 0.946 | 0.885 | 0.839 | 0.911 | 0.916 |

| (0.135) | (0.190) | (0.267) | (0.612) | (0.058)* | (0.074)* | (0.130) | (0.353) | |

| milit. trade | 0.992 | 0.987 | 1.003 | 1.000 | ||||

| (0.463) | (0.308) | (0.777) | (0.984) | |||||

| trade h1 | 2.279 | 1.336 | 2.317 | 1.356 | ||||

| (0.017)** | (0.002)*** | (0.020)** | (0.003)*** | |||||

| trade h2 | 0.628 | 0.795 | 0.751 | 0.803 | ||||

| (0.016)** | (0.022)** | (0.181) | (0.026)** | |||||

| mult. ODA | 1.353 | 1.461 | 1.310 | 1.514 | 1.244 | 1.521 | 1.186 | 1.544 |

| (0.028)** | (0.011)** | (0.037)** | (0.004)*** | (0.182) | (0.009*** | (0.240) | (0.004)*** | |

| Obs. | 1,800 | 1,800 | 1,874 | 1,874 | 1,800 | 1,800 | 1,874 | 1,874 |

| Pseudo | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

Notes: The dependent variable is our countercyclical-altruism binary signal from the baseline model estimated with no control variables and the CARA

©2016 by De Gruyter

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Article

- Voting in Central Banks: Theory versus Stylized Facts

- Delinquency Reinforcement and Balance: Is Exposure to Delinquent Peers Always Risky?

- Can Polluting Firms Favor Regulation?

- Cannabis Control and Crime: Medicinal Use, Depenalization and the War on Drugs

- Coasean Quality of Regulated Goods

- Can Low-Wage Employment Help People Escape from the No-Pay – Low-Income Trap?

- Auctioning Emission Permits with Market Power

- Privatization, Unemployment, and Welfare in the Harris-Todaro Model with a Mixed Duopoly

- Does Eco-labeling of Services Matter? Evidence from Higher Education

- What Do Regulators Value?

- Strategic CSR, Heterogeneous Firms and Credit Constraints

- Regulations to Supplement Weak Environmental Liability

- Intergenerational Educational Persistence among Daughters: Evidence from India

- A Signal of Altruistic Motivation for Foreign Aid

- Has Creative Destruction become more Destructive?

- Is There a Role for Higher Education Institutions in Improving the Quality of First Employment?

- Contribution

- The Effects of School Closure Threats on Student Performance: Evidence from a Natural Experiment

- School Entry, Compulsory Schooling, and Human Capital Accumulation: Evidence from Michigan

- Topics

- Overeducation, Overskilling and Mental Well-being

- Process and Product Innovation and the Role of the Preference Function

- Letter

- Does Evasion Invalidate the Welfare Sufficiency of the ETI?

- How Lobbying Affects Representation: Results for Majority-Elected Politicians

- Consumers’ Misevaluation and Public Promotion

- Meet-the-competition clauses and the strategic disclosure of product quality

- Import Competition and Post-displacement Wages in Korea: Whom You Trade with Matters

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Article

- Voting in Central Banks: Theory versus Stylized Facts

- Delinquency Reinforcement and Balance: Is Exposure to Delinquent Peers Always Risky?

- Can Polluting Firms Favor Regulation?

- Cannabis Control and Crime: Medicinal Use, Depenalization and the War on Drugs

- Coasean Quality of Regulated Goods

- Can Low-Wage Employment Help People Escape from the No-Pay – Low-Income Trap?

- Auctioning Emission Permits with Market Power

- Privatization, Unemployment, and Welfare in the Harris-Todaro Model with a Mixed Duopoly

- Does Eco-labeling of Services Matter? Evidence from Higher Education

- What Do Regulators Value?

- Strategic CSR, Heterogeneous Firms and Credit Constraints

- Regulations to Supplement Weak Environmental Liability

- Intergenerational Educational Persistence among Daughters: Evidence from India

- A Signal of Altruistic Motivation for Foreign Aid

- Has Creative Destruction become more Destructive?

- Is There a Role for Higher Education Institutions in Improving the Quality of First Employment?

- Contribution

- The Effects of School Closure Threats on Student Performance: Evidence from a Natural Experiment

- School Entry, Compulsory Schooling, and Human Capital Accumulation: Evidence from Michigan

- Topics

- Overeducation, Overskilling and Mental Well-being

- Process and Product Innovation and the Role of the Preference Function

- Letter

- Does Evasion Invalidate the Welfare Sufficiency of the ETI?

- How Lobbying Affects Representation: Results for Majority-Elected Politicians

- Consumers’ Misevaluation and Public Promotion

- Meet-the-competition clauses and the strategic disclosure of product quality

- Import Competition and Post-displacement Wages in Korea: Whom You Trade with Matters