Abstract

The multilingual turn in applied linguistics has produced a number of models that approach multilingualism from a variety of disciplinary and theoretical perspectives. However, fully developed models of multilingualism that focus on the language practices of individuals and groups are still lacking. This paper contributes to address this gap by introducing visual models that represent the contexts of practice and attitudes to the languages in the repertoire of lower secondary pupils in Norway. The paper starts by introducing the rich linguistic scenario in Norway and the role of language learning in developing students’ multilingual abilities. After a brief discussion on the role of practice in language learning, we provide an outline of current models of multilingualism, situating our visual models, the Ungspråk Practice-Based Models of Multilingualism (UPMM), in the field. The paper then focuses on the properties of the UPMM, which represent data collected from an online questionnaire answered by 593 students in lower secondary school and allow for the exploration of data both from the perspective of the whole group of participants and from an individual perspective. Particular attention is paid to the interactive features of the models, which can be used by teachers and educators as pedagogical tools for exploring multilingualism and language learning. The paper concludes with a discussion of the contexts of practice for the languages in the participants’ repertoires based on the visual models.

1 Situating our study: multilingualism in Norwegian society and education

Norway is a heteroglossic (Bakhtin 1982; Busch 2017) country whose intrinsic linguistic and dialectal diversity has inspired pioneering studies in linguistic anthropology and code-switching (Blom and Gumperz 1972; Gumperz 1982). The country has two official languages, Norwegian and Sami, an indigenous group of language used in northern Scandinavia and parts of Russia, as well as four minority languages, Kven, Romani, Romanes and Norwegian Sign Language. Norwegian has two official written variants, Bokmål and Nynorsk, which are linguistically close to one another. According to the Norwegian Language Council (Språkrådet) figures for 2022, Nynorsk (or ‘new Norwegian’) is used by 10% of the population, predominantly in Western Norway, whereas Bokmål (or ‘book language’) is the common variant in the rest of the country. Both written variants are taught simultaneously at public schools from year 8[1] of lower secondary school. As of 2022, both variants have the official status of separate languages (Ministry of Culture 2021). Sami is taught from school year 1 in the parts of the country where it is spoken. In addition, Norway boasts a wide variety of regional and local dialects, and their use is common in most domains of society. Most Norwegians are also able to understand standard Swedish and Danish, due to the typological proximity between the languages (Olerud and Dybvik 2014).

English as a foreign language is taught from the first year of primary school. At the age of thirteen, when students start lower secondary school (school year 8 and the focus of this study), they can opt for taking a second foreign language (predominantly, Spanish, German or French) or other elective subjects. According to official figures from The Foreign Language Centre (2020), around 75% of students choose a second foreign language when starting lower secondary school. In the last decades, the linguistic scenario has been enriched even further by a host of immigrant languages. According to Statistics Norway (2022), 18.9% of the Norwegian population is composed of immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents. Such figures imply that a significant percentage of the school population has a family language other than Norwegian. The most commonly spoken immigrant languages include Polish, Lithuanian and Somali (Statistics Norway 2021).

From the brief outline above, it can be stated that virtually all schoolchildren in Norway can be considered multilingual and such rich linguistic diversity has prompted an increased interest in language learning and multilingualism both in academia and in education and language planning. For example, the recently published new curriculum for foreign languages explicitly acknowledges the role of language learning in raising students’ awareness of multilingualism as “an asset, both in school and in society at large” (NDET 2019).

Even though some studies in Norway have looked into learners’ practices related to single foreign languages learned at school (Christiansen and Grønn 2017; Jakobsson 2018; Grønn and Christiansen 2019; Nordhus 2021), no study so far has attempted to map the out-of-school contexts of language practices for all the languages in the learners’ repertoire, including languages learned at lower secondary school and those learned elsewhere. From a general methodological perspective, this research gap is also reflected in studies on multilingualism internationally, which still lack “modelling tools that would describe the current language practices” (Aronin and Moccozet 2021: 3) of multilingual speakers.

Therefore, the aims of this paper are twofold. First, it addresses a research gap by providing a more fine-grained picture of the role of languages in the lives of lower secondary students in Norway. Second, by introducing different visual models representing contexts of language practices and participants’ attitudes in relation to the languages, this article aims to contribute to the future development of models of multilingualism that have as a central component the language practices students (or any other social group) routinely engage in. In order to do so, we introduce and discuss visual models that represent the contexts of language practice of students in lower secondary school, based on data from an online questionnaire (Haukås et al. 2021b) answered by 593 participants. Both the questionnaire and the visual models are part of the Ungspråk research project, a mixed methods study that explores different aspects of multilingualism and multilingual identity in Norwegian schools (Haukås et al. 2021a).

2 Defining language practices

In foreign language learning, the word ‘practice’ commonly refers to the regular, conscious exercising of a particular skill with the aim of improving overall proficiency in a language (for example, classroom activities designed to improve pronunciation, or ‘pronunciation practice’). In this sense, the goals of practice, and the pedagogical activities designed to promote it, are explicitly oriented towards language learning.

However, if schoolchildren are to develop in the languages they learn at school, such languages need to be used beyond the confines of the classroom in meaningful, situated practices (Gee 2004). In this broader sense of the word, ‘practice’ has the meaning of habitual, independently performed actions oriented towards the accomplishment of tasks in the real world.[2] With this connotation, the word ‘practice’ invariably reflects an individuals’ natural interests and inclinations (hence, ‘meaningful’ practices), which define the social domains and interactional[3] patterns in which a given practice occurs (hence, ‘situated’ practices). A few examples of regular practices young learners commonly engage in are the practice of playing video games, the practice of reading comics, the production of videos in digital platforms (such as TikTok) or conversational practices. In this broader sense of the term, the use and knowledge of languages are fundamental components, even though the practice in question might not have any explicit pedagogical, language-learning purpose. From a general theoretical perspective, the approach to language practice adopted in this paper reflects the need “to investigate the doing of language as social activity” (Pennycook 2010: 34), and is grounded on philosophical accounts of practice that conceive “meaning and language [as] arising from and tied to continuous activity” (Schatzki 2001: 21).

Therefore, we define ‘language practice’ as any regular, goal-oriented activity that involves the use of a given language or languages, whether the activity is performed with the intentional aim of improving the knowledge of those languages or not. In line with the holistic approach to multilingualism (Cenoz 2013; Jessner 2008) adopted in this paper, ‘practice’ is considered as any situation in which a language in an individual’s repertoire is regularly deployed for communication purposes, for example in listening or reading, but not necessarily implying the active production of language, as for example in writing or speaking.

From the perspective of foreign language learning, out-of-school practices allow not only for the maintenance and development of the languages in an individual’s repertoire (Hufeisen 2018), including languages learned at school; equally important, they are the ultimate locus where learners’ linguistic and semiotic resources are deployed to act in the world, get things done and interact with other people in real-life situations. Under the current conditions of globalization, language practices usually take place in culturally diverse, hypermediated environments (Kramsch and Thorne 2001), which are structured on interconnected time and spatial scales (Blommaert 2010) and can “be arranged sequentially, in parallel, juxtapositionally, or in overlapping form” (Busch 2015: 4).

Such multiplicity and complexity of patterns of language use (Aronin 2019) pose a series of theoretical and methodological challenges, which partially explain the scarcity of models that attempt to describe the language practices of multilingual individuals and groups (Aronin and Moccozet 2021). In this respect, the current study aims to contribute by developing modelling tools that map the languages learned and used by lower secondary students, along with their respective contexts of practice.

3 Models of multilingualism: a general overview

Scientific models can be defined as forms of representation of the world created to explain and facilitate the understanding of phenomena that are usually too complex and multi-faceted to observe directly (Aronin and Moccozet 2021). In the natural sciences, computer-assisted mathematical modelling has a widespread use also as a predictive tool for a wide range of quantifiable phenomena. In linguistics, models have been amply used to describe and explain language-related phenomena, for example, the syntactic structures of natural languages (Chomsky 1957) or the learning and acquisition of foreign languages (Selinker 1972). However, regardless of the scientific domain where they are applied, all models are necessarily “abstractions, abbreviations […] occasionally even simplifications” (Hufeisen 2018: 174) that, in spite of their potential descriptive or explanatory power, should never be taken as a faithful substitute for the phenomena they purportedly represent.

The multilingual turn in applied linguistics (May 2014) has produced a number of models, albeit limited (Aronin and Moccozet 2021), that approach multilingualism from various theoretical perspectives and that are influenced by a range of research disciplines, such as psycholinguistics, sociolinguistics and foreign language teaching and learning (Hufeisen 2018). Some of them include the Factor Model (Hufeisen 2010, 2018), the Dynamic Systems Theory (DST) model of multilingualism (Herdina and Jessner 2002; Jessner 2008), the Plurilingual Didactic Monitor Model or PDMM (Meissner 2004), and the Dominant Language Constellation or DLC (Aronin 2019; Aronin and Moccozet 2021). It is not the intent of this paper to provide a detailed discussion of each of these models, which can be found, for example, in Hufeisen (2010, 2018 and Hufeisen and Jessner (2019). Instead, in what follows we outline the commonalities that permeate them, as a means of establishing the grounds for the practice-based model of multilingualism proposed in this paper.

All the current models of multilingualism feature a holistic approach (Cenoz 2013; Jessner 2008) that consider the linguistic repertoire of the multilingual individual as an integrated set of resources that are in constant mutual interaction and development, and that have the inherent potential of boosting the speakers’ proficiency in the languages they already know or are currently learning. In line with a holistic approach, all current models of multilingualism acknowledge that multilingual individuals “have a language proficiency that is not simply the sum of their skills in the several languages they have mastered or are mastering” (Aronin and Moccozet 2021: 4). Such synergistic effect, which implies that the whole proficiency of multilingual speakers is always more than the sum of its parts, is reflected in the concept of the multilingual factor or M-factor (Jessner 2008). According to the author, the M-factor “refers to all the effects in multilingual systems that distinguish a multilingual from a monolingual system, that is, all those qualities that develop in a multilingual speaker/learner due to the increase in language contact(s)” (Jessner 2008: 275). What this formulation implies is that the “language contacts” (i.e. the language practices) ultimately determine the qualities and abilities developed by multilingual speakers and learners.

In spite of their commonalities, what distinguishes each of the models above and determines their specific features and components, is the disciplinary perspective adopted in their construction (e.g., psycholinguistics, sociolinguistics, Dynamic Systems theory, foreign language learning pedagogy). In this respect, Hufeisen (2018) highlights the need for developing models that are guided by the specific needs of the discipline (in our case, multilingualism and foreign language learning) and that are designed to serve as the basis for further research.

To the best of our knowledge, the only model of multilingualism that has an explicit practice-based orientation is the DLC (Aronin 2019; Aronin and Moccozet 2021). The DLC focuses on the subset of languages deemed to be of prime importance in the repertoire of an individual (or group) and it is currently being developed in a digital version containing three factors: the dominant languages in a participant’s subset, the participant’s self-reported proficiency in each of the languages, and the perceived typological distance from a language in question to other languages in the individual’s dominant constellation (Aronin and Moccozet 2021). By considering these dimensions, the DLC model distinguishes a person’s most expedient languages which enable him/her to function in multilingual environments (Aronin 2019).

In spite of its advantages for research, the DLC model focuses only on the most prominent languages, thus leaving aside all other languages in a multilingual person’s language repertoire. When investigating multilingualism and foreign language learning, this might pose a limitation, since it fails to account for emerging practices in a foreign language that are restricted to specific contexts and situations, but that have the potential of developing the individual’s future competence in that language. In addition, although the DLC is stated to be a practice-based model, the important dimension of the contexts of practice for each language remains lacking. The model is based on the evaluation of how each language is important for an individual, however, it does not account for the contexts where these languages are practiced.

Addressing these gaps, the visual models introduced in this paper contribute to the field by presenting the whole linguistic repertoire (Busch 2015, 2017) of multilingual schoolchildren in contextualisation. Moreover, they also take into account an attitudinal dimension towards a language, which can significantly influence an individual’s disposition for using it in a particular context or not (Baker 1992; Garrett 2006).

Furthermore, the models presented in this paper approach multilingualism both from the perspective of individual participants and groups of learners; thus, they allow exploring multilingualism both as an individual and a societal phenomenon.

4 The data used in the development of the Ungspråk Practice-Based Models of Multilingualism (UPMM)

The empirical data that served as the basis for the development of our visual models come from the Ungspråk digital questionnaire (Haukås et al., 2021b). The questionnaire was specifically designed to investigate multilingualism and multilingual identity among schoolchildren, and it was answered by 593 pupils in their first year of lower secondary schools (i.e. school year 8). Data collection took place between April and August, 2019 in seven different schools in and around the city of Bergen.

In one of the sections of the questionnaire, participants answered a series of 9 statements related to the languages they learned at school (Norwegian, English and either Spanish, German or French, if they took a second foreign language as an elective subject). After that, respondents were requested to list all the other languages in their repertoire. The textual prompt[4] in this subsection encouraged students to name all the languages they felt they knew, regardless of the level of proficiency. In line with a holistic approach to multilingualism, the rationale underlying the prompt was to make participants reflect on all the languages in their repertoire, including languages with expected receptive skills (such as Danish and Swedish), family languages, dialects, sign language and possibly languages structured on other semiotic systems, such as body language or coding.

For each language listed by the participants, the questionnaire generated the same battery of nine statements. The statements that served as data input for creating the UPMM are the following:

I use this language with my family.

I use this language to speak to (some of) my friends.

I (sometimes) use this language when I go on holidays.

I (sometimes) use this language when I am on the Internet.

I (sometimes) watch TV/films/listen to music in this language.

I am proud that I know this language.

I think I know this language well.

It is important for me to know this language.

I avoid using this language.

Statements 1–5 allow for the mapping of the different contexts in which a given language is practiced and they play a central role in the UPMM visual models presented in this paper.

Following the theoretical perspective outlined in Section 2 of this paper, ‘contexts of practice’ in the models should be conceptualised as more than just the commonplace assumption that people use languages in particular contexts (Pennycook 2010). Rather than just focussing on the idea that language knowledge and use are shaped by the contexts of practice, we are interested in understanding how languages, as ‘products of socially located activity’ (Pennycook 2010: 17), actually help create the contexts where they are used.

In this respect, it is important to point to the limitations of the available data since they do not provide any information about the type and quality of the language practices in each given context. However, the statements are important indicators for the presence of a language in particular contexts of practice, as well as the overlapping presence of different languages in the same contextual environment, for example, languages in the family. When transposed into the visual models presented below, the data provide an overview of the role of different languages in the participants’ lives and facilitate the visualisation of overlapping patterns and contexts of practice, both from an individual and a group perspective. The visual design of the UPMM also facilitate the comparison between the contexts of practice among languages learned and used at school or elsewhere.

Statements 6–9 provide extra information about some of the participants’ attitudes and opinions (Dörnyei and Taguchi 2010) in relation to each reported language, including their perceived knowledge and willingness to use it. Attitudes and opinions towards languages have been topics of extensive research in psycholinguistics and language learning (for example, Baker 1992; Gardner 1985; Garrett 2006) and, since they have a bearing on the individual’s disposition to use and practice a language, they serve as valuable complementary data in the models. To this end, statements 7 and 8 above provide information about the participants’ own opinions of their proficiency in the languages, as well as their perceived relevance and the societal value, respectively. Statements 6 and 9 look into more intangible positive and negative attitudes towards the languages that are largely determined by social factors and the participants’ own life experiences (Garrett 2006). Taken together, the statements are aimed at providing a holistic description of the participants’ attitudes towards languages in general. Such issues are resumed in Subsection 6.3.

5 UPMM: modelling the contexts of language practice with data visualisations

An important structural component of scientific models in general, and language models in particular, is that they invariably include a visual component that is “used to illustrate and clarify the verbal explanations” (Aronin and Moccozet 2021) needed to explain the model. Several authors have highlighted the relevance of visual representations, for example, in boosting cognition of abstract concepts and phenomena (Kirsh 2009, 2010; Scaife and Rogers 1996), as a crucial type of literacy in contemporary, data-driven societies (Tønnessen 2020), and in representing multilingual subjects’ identities (Kalaja and Melo-Pfeifer 2019). In the development of the visual models discussed in this section we drew on previous expertise acquired in designing interactive digital data visualisations that explore multilingualism with research participants based on data they generated (Storto 2022).

The visualisation models presented below incorporate the visual-haptic properties of digital media (Storto 2021) and invite users to explore and interact with the data both visually and manually. They are divided in two main sets which are explained below. However, for a better understanding of their mechanics and affordances, we strongly recommend that the readers access the visual models via the hyperlinks provided in the appendix.

5.1 UPMM - Model 1: representing the language practices for the whole group of participants

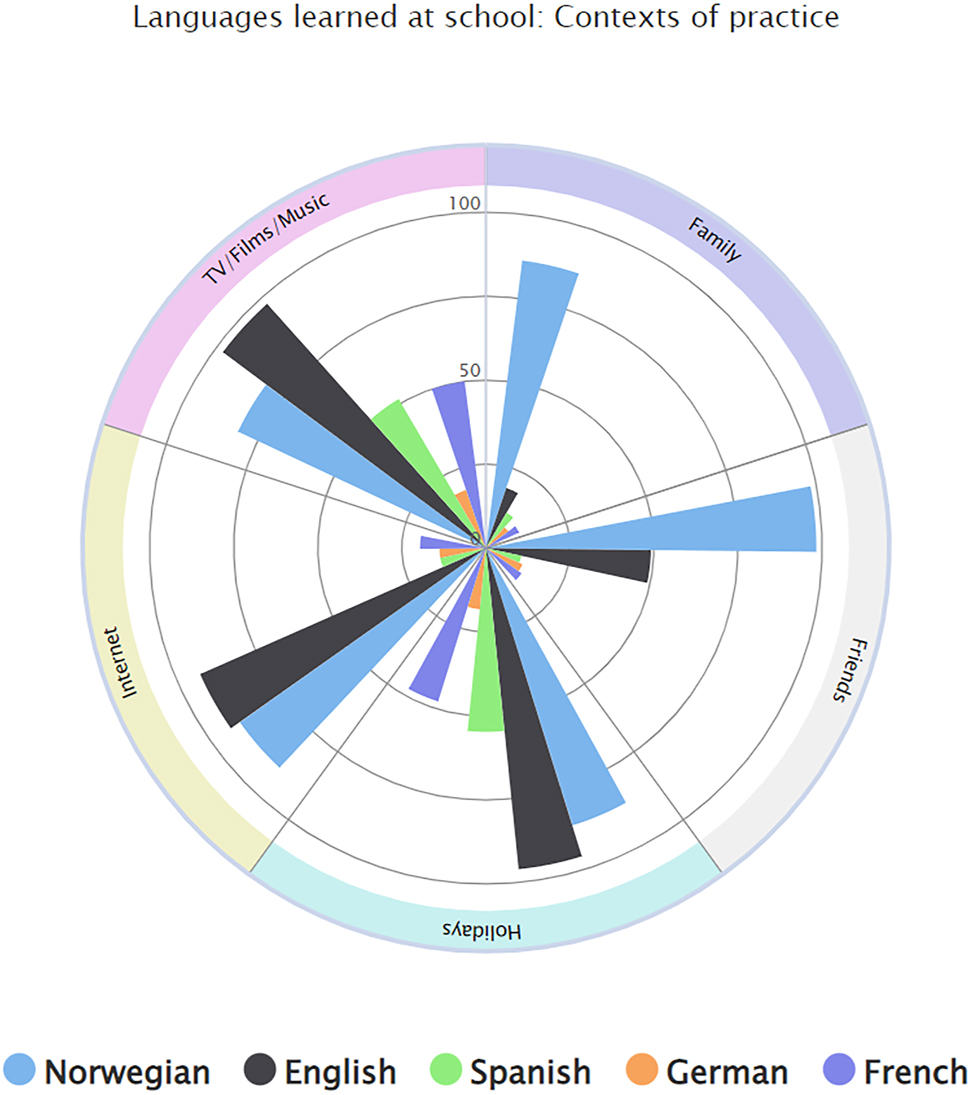

The first set of visual models represents the answers for the whole data set of the Ungspråk questionnaire (n = 593) and they focus on the languages learned and used in and out of school and their contexts of practice. Each model was designed to include five frequently reported languages at a time and their respective contexts of practice, and they are available in two versions which provide different perspectives on the same data. The first version highlights the contexts of practice for the languages (Figure 1). The contexts are presented in the outer circle of the visual, while the languages are represented as columns inside the chart. The design of the models in this version allows for the simultaneous display of five different languages and contexts of practice in one single visual ensemble, thus facilitating the comparison among languages.

Model representing the contexts of practice for the five languages learned at school.

When hovering the mouse over the columns, the contexts of practice for a given language are highlighted, forming a shape resembling a five-pointed star, thus highlighting the scope of a particular language in the five contexts, in a scale from 0 to 100% (Figure 2).

The scope of Norwegian in five contexts of practice.

The second version inverts the way the data is visualized and presents each language separately in the outer circle while the contexts of practice for each language are represented as radial columns in the inner circle (Figure 3).

Second version of the model presenting languages in the outer circle.

The second version also features the attitudes of participants for the languages. This function is activated by hovering the mouse over the language in question (Figure 4).

Detail of the visual model showing participants’ attitudes to English.

5.2 UPMM - Model 2: mapping the language practices of individual participants

The second set of visual models are composed of network graphs that approach the languages from the perspective of an individual participant. They also come in two versions. The first version represents the participants’ whole linguistic repertoire along with the contexts of language practice. Figure 5 shows the model for a prototypical participant, whose criteria for selection are explained in Subsection 6.3.

Network graph representing the linguistic repertoire of one of the prototypical participants.

The visual models in this version are composed of three factors: the languages in a participant’s repertoire (represented as a circle), the number of contexts where the languages are practiced (represented as slices in circle) and colour-coded arrows connecting the languages according to shared contexts of practice, thus allowing for a quick identification of overlapping contexts (Figure 6). The size of the circles representing each language are in scale to the number of contexts of practice (from 1 to 5), thus providing a visual representation of ‘how big’ a role a given language plays in the participant’s life. If a language was listed by the participant but had no reported practice in any of the contexts, it is represented as a tiny white dot with no connections (for example, Danish in Figure 5).

Arrows showing overlapping contexts of practice for English, Norwegian and Spanish (holidays).

The second version of the model represents the attitudes of the participant to the languages in their repertoire and its mechanics is similar to the first version (Figure 7).

Network graph representing the language attitudes of the prototypical participant.

6 Exploring contexts of language practice based on the visual models

In this section, we present and discuss the contexts of language practice and corresponding language attitudes based on the models described above. We start with the models representing the whole group of participants (Model 1). Under this category, we discuss the findings related to the five languages learned at school (Norwegian, English, Spanish, German and French), followed by the five most frequent languages in the dataset which are not learned at school. We conclude the section with an analysis of the linguistic repertoire of two individual participants (Model 2): a prototypical participant and a participant with the most common immigrant language in Norway in their repertoire. As stated earlier, for a complete visualisation of the data in the real models, we recommend accessing them via the links provided in Appendix I.

6.1 UPMM - Model 1: languages learned at school

The most outstanding general feature in the group of languages learned at school is that no language is used by all students in any context (see Figure 1). The highest percentage is the use of Norwegian in the family (98.3%), followed by English to watch TV/films and listen to music (97.6%) and on holidays (96.1%). Since both languages are learned from school year 1 and all participants (n = 593) were currently studying them at the time of data collection, some interesting comparisons can be drawn between the contexts of practice for Norwegian and English.

Even though the use of Norwegian is highly significant in all five contexts, English is the predominant language on the Internet (92.9% of the participants), on holidays (96.1%) and on TV/films and music (97.6%), followed closely by Norwegian (89.7%, 86.5% and 81.5%, respectively). The status of English as a global lingua franca (Gardner 2012; Mauranen 2015; Ricento 2016) and the cultural clout exerted by English-speaking countries, especially the United States, are possible explanations for the higher frequency of English than Norwegian in these three contexts. A more revealing finding, however, is the marked bilingual (Norwegian/English) character of Norwegian students, an inference that is strengthened by the fact that 49.1% of the participants mention the use of English in their interactions with friends. In this respect, the knowledge of English seems to be a relevant factor in the self-identification as multilingual individuals among the participants (Storto 2022).

In relation to the second foreign languages learned at school, our data set follows both national and regional trends (Foreign Language Centre 2020), with Spanish being the first choice among students (n = 296), followed by German (n = 109) and French (n = 92). The status of these languages differs from Norwegian and English in two important aspects. First, at the time of data collection (year 8 of lower secondary school), participants had just started learning these languages, so their presence in out-of-school contexts should expectedly be lower than Norwegian and English. Second, generally speaking, Spanish, French and German have a weaker cultural influence in Norwegian social contexts than English (a global lingua franca) and Norwegian (a national language). Coupled together, these factors contribute to the lower occurrence of Spanish, French and German in the contexts of practice represented in the model.

However, the relatively high number of participants who reported the occurrence of Spanish and French in the contexts of “TV/films and music” (51.4% and 50%, respectively) and “holidays” (54.7% and 47.8%, respectively) can be considered as relevant indicators of meaningful practices that involve the use of these languages. Even though it can be argued that the sporadic use of a language on holidays is not enough for a learner to become proficient, the experiences usually associated with it have the potential for making the learner establish affective connections with the people and places where the language is used, which ultimately might have a positive influence in their language learning. This does not seem to be the case of German which, in spite of being the second foreign language of choice among students, is the least used language outside school, with all five indicators below the mark of 20%.

A noteworthy aspect of the participants’ attitudes in relation to the languages is their higher confidence in using Norwegian and English. Only 3.7% and 9.8% respectively said they avoid using these languages, compared to Spanish (28.7%), German (30.3%) and French (27.2%). Even though these figures are not surprising, given that participants had been learning Norwegian and English since school year 1 or longer, the percentages of students who reportedly avoid using Spanish, German and French is quite high considering the stated goal of the curriculum for foreign languages (2019) that the foreign “language shall be practised from the very beginning, both with and without the use of various media and tools” (NDET 2019). If nearly one third of the students in the subject avoids using the language, this poses challenges for the teachers responsible for implementing the curriculum. However, the perceived importance of learning these languages is relatively high (Spanish = 57.1%, French = 55.4% and German = 51.4%) and can be interpreted as an indicator of participants’ awareness of the relevance of learning languages other than Norwegian and English. A further interesting finding related to foreign language learning in school is that almost all learners of French (93.8%) are proud of knowing the language. The percentage of students being proud of knowing Spanish (81.8%) and German (73.4) is markedly lower. The findings call for further research to explain the causes of these differences and also how taking pride in learning Spanish and German can be increased.

6.2 UPMM - Model 1: languages not learned at school

The models for languages not learned at school are represented in Figure 8 below.

Visual models for the languages not learned at school.

The most listed languages in this category are Swedish (n = 214) and Danish (n = 173). Another interesting finding in the category is the number of participants who listed Spanish (n = 84), German (n = 87) and French (n = 66) as languages they know, even though they do not learn it at school.

In relation to Swedish and Danish, apart from the typological similarities between these languages and Norwegian, which facilitates intercomprehension, the cultural commonalities and geographical proximity can be considered as relevant factors for the high occurrence of these languages among the participants’ repertoires. In relation to the contexts, both languages have high figures for use on holidays (51.2% for Swedish and 42.8% for Danish) while Swedish has a higher occurrence in the category “TV/films and music” than Danish (56.5% and 39.9%, respectively). The strong influence of Swedish cultural productions, such as TV series, in the Norwegian context is a possible determining factor for the figures.

In relation to Spanish, French and German, a noteworthy feature in this group is the consistently higher percentage of students who reportedly use these languages with friends, when compared to the participants who learn the same languages at school (Spanish 20.2% and 10.8%; German 24.1% and 11.9%; French 15.2% and 13%, respectively). However, the participants’ perceived proficiency in these languages is significantly lower when compared to the students who learn the same languages at school (Spanish 8.3% and 21.6%; German 2.3% and 26.6%; French 7.6% and 21.7%, respectively). Nevertheless, the fact that so many students confidently report having these languages in their repertoire, shows a flexible, ‘low threshold’ understanding of what it takes to know a language. Furthermore, the very frequent reports of knowing Swedish and Danish suggest that many students in the Ungspråk project do not require productive proficiency in a language to feel that they know them (see Haukås 2022 for a discussion of students’ understanding of multilingualism compared with the scholarly debate).

6.3 UPMM - Model 2: languages from the perspective of individual participants

This section presents and discusses the visual models for the languages in the repertoire of two individual participants. Since there were 593 participants in the original dataset from the questionnaire, some criteria of representativeness had to be adopted in their selection. The first participant (referred to as “prototypical participant”) was selected by adopting the following sequential criteria:

The participant had to take a second foreign language at school (505 participants took a second foreign language as opposed to 88 participants who took another elective subject).

The second foreign language had to be Spanish, which had the highest number of participants in the dataset (n = 296), as opposed to German (n = 109), French (n = 92).

The participant had to list both Swedish and Danish in their repertoire, which are the languages not learned at school with the highest number of occurrences in the dataset (n = 214 and n = 173, respectively).

Finally, the participant had to be a girl rather than a boy,[5] since there was a higher number of the former (n = 317) than the latter (n = 276) in the dataset.

After the criteria above were applied, a participant was chosen randomly from within the group.

The main criterion for selecting the second participant was that they included one of the most common immigrant languages in their repertoire. According to figures from Statistics Norway for 2022, Poland is the country with the highest number of immigrants or Norwegian-born to immigrant parents. Therefore, Polish was considered one of the main immigrant languages in our dataset. The participant was selected first by following steps 1 and 2 above. After that, only participants who listed Polish (the most common immigrant language in Norway) in their repertoire were selected. Finally, a participant was chosen randomly from within the group. Figure 9 below represents the models for the language repertoire of the two participants.

Models for the contexts of practice of a prototypical participant (left) and a participant with the most common immigrant language (right).

The most noteworthy distinction between the two participants is the central role of Norwegian and Polish, respectively, in the five contexts of practice. In both cases, English is the second language used in most contexts. Both participants report using English on the Internet, on holidays and to watch films and/or listen to music, which is, coincidentally, the three contexts of practice for the language with the highest number of respondents from the whole dataset (see Figure 1). In relation to languages in the family, both participants report the use of two languages: Norwegian/sign language and Polish/Russian. Such a finding can be an indicator of fluid language practices in which two (or more) languages are used simultaneously by multilingual family members in everyday interactions and which have been amply documented (Kusters et al. 2021; Lanza and Lomeu Gomes 2020; Lomeu Gomes 2020).

Even though both participants take Spanish at school, its role in their practices is peripheral. However, the reported use of Spanish on holidays by the first participant implies that the language has a role in the participant’s life that goes beyond the confines of the school, which is not yet the case with the second participant.

In relation to Norwegian, the dominant national language, the second participant reports using it only in two contexts, on the Internet and with friends. This finding might be indicative of a relatively peripheral role of Norwegian in the participants’ repertoire. Such an assumption is also supported by the fact that the participant reports avoiding using Norwegian as shown in the model for attitudes below (Figure 10, model on the right), even though she/he also claims to know the language well. A complementary analysis of the language profile of the participant based on data from the questionnaire showed that Norwegian is not her/his native language and that the participant had started using the language less than three years before. This may explain the hesitancy to use the language.

Models for the language attitudes of a prototypical participant (left) and a participant with the most common immigrant language (right).

In relation to the attitudes of the prototypical participant (Figure 10, model on the left), the fact that the participant feels proud and realises the importance of all the languages in his/her repertoire is indicative of a general positive attitude towards languages (and language learning), and it is reflected in the predisposition to use all the languages (reportedly, none of the languages are avoided by the participant). The self-reported good knowledge in all the languages should be interpreted holistically as further evidence of the participant’s attitudes, rather than as an accurate description of his/her abilities in each of the individual languages in the repertoire. This interpretation is also supported by the fact that the participant answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘are you multilingual?’, in another section of the Ungspråk questionnaire.

7 Conclusion and the way forward

This article presented and discussed visual models for the contexts of practice and language attitudes in the linguistic repertoire of lower secondary students, in an attempt to outline the potentials of developing practice-based, learner-oriented models of multilingualism. Although a number of models of multilingualism exist in the field, they mainly explore/explain the language learning processes in the multilingual mind (e.g., Hufeisen 2010, 2018; Herdina and Jessner 2002; Jessner 2008) or suggest how multilingual approaches can be implemented in education (Meissner 2004). As discussed earlier, in spite of its practice orientation, the DLC model (Aronin 2019; Aronin and Moccozet 2021) does not include the representation of the language practices multilingual individuals routinely engage in and is restricted to the most expedient languages. The main contribution of the practice-based models presented in this article is the added contextualisation of language practices and an attitudinal dimension related to learners’ multilingualism. A further contribution is the attempt to design interactive digital models that can be used by researchers as descriptive-analytical instruments and by language teachers as exploratory pedagogical tools for raising awareness and promoting discussions about language learning, language practices and multilingualism. In addition, the UPMM can serve as a basis for the future development of open, participant-centred modelling tools which would allow students and other stakeholders to input their own data.

Nevertheless, given their early stage of development, we make no claims about the UPMM as implying fully developed, practice-based models of multilingualism. It also needs to be stated that models like the UPMM can only represent incomplete parts of the multilingual lives of multilingual individual and groups. Thus, for a more detailed, in-depth view of the participants’ practices (and the languages associated with them), complementary methods of data collection are required. These would include, for example, questionnaires, language diaries, logs and semi-structured interviews. In addition, better data visualization techniques need to be designed to facilitate the interaction of participants with the data and the interpretation of the language use patterns by the researchers, educators and other stakeholders.

Language learning never happens in a vacuum. It is always embedded in larger ecologies of practice which shape and determine the patterns of language use and the competences developed by individuals and groups, which in turn end up shaping and transforming the practices themselves. To a large extent, it can be said that (language) learning occurs in this recursive, mutually influencing process. Building models of multilingualism that bring to the fore the interplay between language development and practice can be a fruitful way to understand the role of languages in the lives of individuals in contemporary societies, which are marked by increased mobility, intensified migration and engagement in digital networks of communication (Busch 2017). We hope that the UPMM represent a step in this direction.

Links to the visual models:

Models representing the language practices of the whole group of participants:

https://org.uib.no/multilingual/AllPolarCharts/UIB%20Project%20polar/LangLearnedAtSchool.html

https://org.uib.no/multilingual/AllPolarCharts/UIB%20Project%20polar/5MostFreqNotLearnedSchool.html

https://org.uib.no/multilingual/AllPolarCharts/UIB%20Project%20polar/OtherLangNotLearnedSchool.html

Models representing the language practices of individual participants:

https://org.uib.no/multilingual/AllNetworkGraphs%20-%20Copy/ProtoParticipant.html

https://org.uib.no/multilingual/AllNetworkGraphs%20-%20Copy/ParticipantWPolish.html

https://org.uib.no/multilingual/AllNetworkGraphs%20-%20Copy/PartNo3rdLangSchool.html

Ten most frequently mentioned languages in the dataset that are not learned at school.

| Ten most frequently mentioned languages in the dataset that are not learned at school | |

|---|---|

| LANGUAGE | Number of occurrences |

| Swedish | 214 |

| Danish | 173 |

| German | 87a |

| Spanish | 84a |

| French | 66a |

| Russian | 26 |

| Polish | 22 |

| Nynorsk | 19 |

| Chinese | 19 |

| Italian | 18 |

-

aThese occurrences refer to participants who do not study these languages as elective subjects at school.

References

Aronin, Larissa. 2019. Dominant language constellation as a method of research. International Research on Multilingualism: Breaking with the Monolingual Perspective 35. 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21380-0_2.Search in Google Scholar

Aronin, Larissa & Laurent Moccozet. 2021. Dominant language constellations: Towards online computer-assisted modelling. International Journal of Multilingualism. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2021.1941975.Search in Google Scholar

Baker, Colin. 1992. Attitudes and language. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.Search in Google Scholar

Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1982. The dialogic imagination. Austin: University of Texas Press.Search in Google Scholar

Blommaert, Jan. 2010. The sociolinguistics of globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511845307Search in Google Scholar

Blom, Jan-Petter & John Gumperz. 1972. Social meaning in linguistic structure: Code-switching in Norway. In John Gumperz & Del Hymes (eds.), Directions in sociolinguistics. New York: Holt Rinehart & Winston.Search in Google Scholar

Busch, Brigitta. 2015. Linguistic repertoire and Spracherleben, the lived experience of language. In Working papers in urban languages and literacies. London: King’s College.Search in Google Scholar

Busch, Brigitta. 2017. Expanding the notion of the linguistic repertoire: On the concept of Spracherleben—the lived experience of language. Applied Linguistics 38(3). 340–358. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amv030.Search in Google Scholar

Cenoz, Jasone. 2013. Defining multilingualism. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 33. 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026719051300007X.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1957. Syntactic structures. The Hague: Mouton.10.1515/9783112316009Search in Google Scholar

Christiansen, Ane & Berit Grønn. 2017. Spansk nivå III – nye læringsmuligheter og deltakelse i læringsrom i hverdag og frigid. Nordic Journal of Language Teaching and Learning 5(1). 3–15. https://doi.org/10.46364/njmlm.v5i1.383.Search in Google Scholar

Dörnyei, Zoltán & Tatsuya Taguchi. 2010. Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration, and processing. New York: Routledge.10.4324/9780203864739Search in Google Scholar

Foreign Language Centre. 2020. Elevane sit val av framandspråk på ungdomsskulen 2019–2020 [Pupils’ choice of a foreign language in lower secondary school 2019–2020]. https://www.hiof.no/fss/sprakvalg/fagvalgstatistikk/elevanes-val-av-framandsprak-i-ungdomsskulen-19-20.pdf (accessed 15 January 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Gardner, Robert C. 1985. Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.Search in Google Scholar

Gardner, Sheena. 2012. Global English and bilingual education. In Marilyn Martin-Jones, Adrian Blackledge & Angela Creese (eds.), The Routledge handbook of multilingualism, 247–263. Oxfordshire: Routledge. Available at: http://www.routledge.com/books/details/9780415496476/.Search in Google Scholar

Garrett, Peter. 2006. Language attitudes. In Carmen Llamas, Louise Mullany & Peter Stockwell (eds.), The Routledge companion to sociolinguistics, 136–141. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203441497-23Search in Google Scholar

Gee, James Paul. 2004. Situated language and learning: A critique of traditional schooling. New York: Taylor & Francis Group.Search in Google Scholar

Grønn, Berit & Ane Christiansen. 2019. Vg2-elevers kontakt med spansk i fritiden: Det er morsommere å se serier når du skjønner litt spansk. Nordic Journal of Language Teaching and Learning 7(1). https://doi.org/10.46364/njmlm.v7i1.524.Search in Google Scholar

Gumperz, John J. 1982. Discourse strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511611834Search in Google Scholar

Haukås, Åsta. 2022. Who are the multilinguals? Students’ definitions, self-perceptions and the public debate. In Wendy Bennett & Linda Fisher (ed.), Multilingualism and identity: Interdisciplinary perspectives, 281–298. Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108780469.014Search in Google Scholar

Haukås, Åsta, André Storto & Irina Tiurikova. 2021a. The Ungspråk project: Researching multilingualism and multilingual identity in lower secondary schools. Globe: A Journal of Language, Culture and Communication 12. 83–98. https://doi.org/10.5278/ojs.globe.v12i.6500.Search in Google Scholar

Haukås, Åsta, André Storto & Irina Tiurikova. 2021b. Developing and validating a questionnaire on young learners’ multilingualism and multilingual identity. Language Learning Journal 49(4). 404–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2021.1915367.Search in Google Scholar

Herdina, Philip & Ulrike Jessner. 2002. A dynamic model of multilingualism: Perspectives of change in psycholinguistics. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781853595547Search in Google Scholar

Hufeisen, Britta. 2010. Theoretische Fundierung multiplen Sprachenlernens – faktorenmodell 2.0 [Theoretical foundation of multiple language learning - factor model 2.0]. Jahrbuch Deutsch als Fremdsprache 36. 200–207.Search in Google Scholar

Hufeisen, Britta. 2018. Models of multilingual competence. In Andreas Bonnet & Peter Siemund (eds.), Foreign language education in multilingual classroom 7. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/hsld.7.08hufSearch in Google Scholar

Hufeisen, Britta & Ulrike Jessner. 2019. The psycholinguistics of multiple language learning and teaching. In David Singleton & Larissa Aronin (eds.), Twelve Lectures on multilingualism, 65–100. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781788922074-005Search in Google Scholar

Jessner, Ulrike. 2008. A DST model of multilingualism and the role of metalinguistic awareness. The Modern Language Journal 92(2). 270–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00718.x.Search in Google Scholar

Jakobsson, Jørgen. 2018. A study of the types, frequency and perceived benefits of extramural activities on Norwegian 10th graders’ development of English as a foreign language. Stavanger: University of Stavanger MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Kalaja, Paula & Silvia Melo-Pfeifer (eds.). 2019. Visualising multilingual lives: More than words. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.10.21832/9781788922616Search in Google Scholar

Kirsh, David. 2009. Interaction, external representation and sensemaking. In Niels Taatgen, Dirk van Rijn, John Nerbonne & Lambert Schomaker (eds.), Proceedings of the 31st annual conference of the cognitive science society, 1103–1108. Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society.Search in Google Scholar

Kirsh, David. 2010. Thinking with external representations. AI & Society 25(4). 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-010-0272-8.Search in Google Scholar

Kramsch, Claire & Steve L. Thorne. 2001. Foreign language learning as global communicative practice. In David Block & Deborah Cameron (eds.), Globalization and language teaching. New York: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Kusters, Annelies, Maartje De Meulder & Jemina Napier. 2021. Family language policy on holiday: Four multilingual signing and speaking families travelling together. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 42(8). 698–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.1890752.Search in Google Scholar

Lanza, Elizabeth & Rafael Lomeu Gomes. 2020. Family language policy: Foundations, theoretical perspectives and critical approaches. In Andrea C. Schalley & Susana A. Eisenchlas (eds.), Handbook of home language maintenance and development. Social and affective factors, 153–173. De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9781501510175-008Search in Google Scholar

Lomeu Gomes, Rafael. 2020. Talking multilingual families into being: Language practices and ideologies of a Brazilian-Norwegian family in Norway. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 43(10). 993–1013. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2020.1788037.Search in Google Scholar

Mauranen, Anna. 2015. English as a global lingua franca: Changing language in changing global academia. In Kumiko Murata (ed.), Exploring ELF in Japanese academic and business contexts, 29–46. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Search in Google Scholar

May, Stephen (ed.). 2014. The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL and bilingual education. Oxford: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Meissner, Franz-Joseph. 2004. Modelling plurilingual processing and language growth between intercomprehensive languages. In Lew N. Zybatow (ed.), Translation in der globalen Welt und neue Wege in der Sprach- und Übersetzerausbildung, 31–57. Frankfurt a.M.: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Ministry of Culture. 2021. Lov om språk [the language act]. https://lovdata.no/lov/2021-05-21-42 (accessed 22 December 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Nordhus, Anne W. 2021. Norwegian lower secondary school teachers’ and students’ beliefs and reported experiences concerning extramural English and language identity in teaching and learning L2 English. Stavanger: University of Stavanger MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training – NDET. 2019. Curriculum for foreign languages. Oslo: Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. https://www.udir.no/lk20/fsp01-02?lang=eng (accessed 19 November 2021).Search in Google Scholar

Olerud, Anna K. & Ingrig M. Dybvik. 2014. Holdninger til og forståelse av nabospråk: En undersøkelse av holdninger til og forståelse av dansk og svensk gjort ved tre norske ungdomsskoler [Attitudes and comprehension of neighboring languages: A survey of attitudes comprehension of Danish and Swedish conducted at three Norwegian upper secondary schools]. Drammen: Høgskolen i Buskerud og Vestfold MA thesis.Search in Google Scholar

Pennycook, Alastair. 2010. Language as a local practice. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge.10.4324/9780203846223Search in Google Scholar

Ricento, Thomas. 2016. Language policy and political economy: English in a global context. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199363391.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Scaife, Mike & Yvonne Rogers. 1996. External cognition: How do graphical representations work? International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 45. 185–213. https://doi.org/10.1006/ijhc.1996.0048.Search in Google Scholar

Schatzki, Theodore. 2001. Introduction. In Theodore Schatzki, Karin K. Cetina & Eike von Savigny (eds.), The practice turn in contemporary theory. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Selinker, Larry. 1972. Interlanguage. International Review of Applied Linguistics 10. 209–231. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.1972.10.1-4.209.Search in Google Scholar

Sloterdijk, Peter. 2013. You must change your life: On anthropotechnics. Cambridge: Polity Press.Search in Google Scholar

Statistics Norway (Statistisks Sentralbyrå). 2022. Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant, by country background. https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/innvandrere/statistikk/innvandrere-og-norskfodte-med-innvandrerforeldre (accessed 1 Sept. 2022).Search in Google Scholar

Storto, André. 2021. Fingerprints: Towards a multisensory approach to meaning in digital media. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 16(3–4). 132–143. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1891-943x-2021-03-04-04.Search in Google Scholar

Storto, André. 2022. ‘To be multilingual means…’: Exploring a participatory approach to multilingual identity with schoolchildren. International Journal of Multilingualism Article in publication process in the International Journal of Multilingualism. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2022.2082441.Search in Google Scholar

Tønnessen, Elise. S. 2020. What is visual-numeric literacy and how does it work? In Martin Engebretsen & Helen Kennedy (eds.), Data Visualization in society, 189–206. Amsterdam University Press.10.2307/j.ctvzgb8c7.18Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Special Issue: The Yellow Peril or the Model Minority? Racialized identities and discourses of Asian Americans and Asian Canadians; Guest Editor: Christian Chun

- Research Articles

- Paradoxes of the Canadian mosaic: “being, feeling and doing Canadian”

- The Asian American teaching method? An overview of language education, social justice issues, and challenging ‘Oppressed’ versus ‘Model’ minority binary discourse

- Life and work between home and “homeland”: a narrative inquiry of transnational Chinese adoptees’ identity negotiations across time and space

- I ain’t your f*cking Model Minority! Indexical orders of ‘Asianness’, class, and heteronormative masculinity

- Special Issue: Assessment and Creativity through a Translingual Lens; Guest Editors: Lavinia Hirsu, Marta Nitecka Barche and Dobrochna Futro

- Editorials

- Assessment and creativity through a translingual lens: introduction

- Assessment and creativity through a translingual lens: transdisciplinary insights

- Creative translanguaging in formative assessment: Chinese teachers’ perceptions and practices in the primary EFL classroom

- Creativity, criticality and translanguaging in assessment design: perspectives from Bangladeshi higher education

- Integrating translanguaging into assessment: students’ responses and perceptions

- Research Articles

- Investigation of factors underlying foreign language classroom anxiety in Chinese university English majors

- Why can’t I teach English? A case study of the racialized experiences of a female Ugandan teacher of English in an EFL context

- Primary-concern solicitation in Chinese medical encounters

- The relationships between young FL learners’ classroom emotions (anxiety, boredom, & enjoyment), engagement, and FL proficiency

- Visualising the language practices of lower secondary students: outlines for practice-based models of multilingualism

- Observing a teacher’s interactional competence in an ESOL classroom: a translanguaging perspective

- Foreign language teacher grit: scale development and examining the relations with emotions and burnout using relative weight analysis

- Vocabulary learning in a foreign language: multimedia input, sentence-writing task, and their combination

- The predictive effects of reading speed and positive affect on first and second language incidental vocabulary acquisition through reading an authentic novel

- The effects of cultural and educational background on students’ use of language learning strategies in CFL learning

- Transl[iter]ating Dubai’s linguistic landscape: a bilingual translation perspective between English and Arabic against a backdrop of globalisation

- Exploring Tibetan residents’ everyday language practices in Danba county, Southwest China: a case study

- The mechanism for the positive effect of foreign language peace of mind in the Chinese EFL context: a moderated mediation model based on learners’ individual resources

- A latent profile analysis of L2 writing emotions and their relations to writing buoyancy, motivation and proficiency

- “Part of me is teaching English”: probing the language-related teaching practices of an English-medium instruction (EMI) teacher

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Special Issue: The Yellow Peril or the Model Minority? Racialized identities and discourses of Asian Americans and Asian Canadians; Guest Editor: Christian Chun

- Research Articles

- Paradoxes of the Canadian mosaic: “being, feeling and doing Canadian”

- The Asian American teaching method? An overview of language education, social justice issues, and challenging ‘Oppressed’ versus ‘Model’ minority binary discourse

- Life and work between home and “homeland”: a narrative inquiry of transnational Chinese adoptees’ identity negotiations across time and space

- I ain’t your f*cking Model Minority! Indexical orders of ‘Asianness’, class, and heteronormative masculinity

- Special Issue: Assessment and Creativity through a Translingual Lens; Guest Editors: Lavinia Hirsu, Marta Nitecka Barche and Dobrochna Futro

- Editorials

- Assessment and creativity through a translingual lens: introduction

- Assessment and creativity through a translingual lens: transdisciplinary insights

- Creative translanguaging in formative assessment: Chinese teachers’ perceptions and practices in the primary EFL classroom

- Creativity, criticality and translanguaging in assessment design: perspectives from Bangladeshi higher education

- Integrating translanguaging into assessment: students’ responses and perceptions

- Research Articles

- Investigation of factors underlying foreign language classroom anxiety in Chinese university English majors

- Why can’t I teach English? A case study of the racialized experiences of a female Ugandan teacher of English in an EFL context

- Primary-concern solicitation in Chinese medical encounters

- The relationships between young FL learners’ classroom emotions (anxiety, boredom, & enjoyment), engagement, and FL proficiency

- Visualising the language practices of lower secondary students: outlines for practice-based models of multilingualism

- Observing a teacher’s interactional competence in an ESOL classroom: a translanguaging perspective

- Foreign language teacher grit: scale development and examining the relations with emotions and burnout using relative weight analysis

- Vocabulary learning in a foreign language: multimedia input, sentence-writing task, and their combination

- The predictive effects of reading speed and positive affect on first and second language incidental vocabulary acquisition through reading an authentic novel

- The effects of cultural and educational background on students’ use of language learning strategies in CFL learning

- Transl[iter]ating Dubai’s linguistic landscape: a bilingual translation perspective between English and Arabic against a backdrop of globalisation

- Exploring Tibetan residents’ everyday language practices in Danba county, Southwest China: a case study

- The mechanism for the positive effect of foreign language peace of mind in the Chinese EFL context: a moderated mediation model based on learners’ individual resources

- A latent profile analysis of L2 writing emotions and their relations to writing buoyancy, motivation and proficiency

- “Part of me is teaching English”: probing the language-related teaching practices of an English-medium instruction (EMI) teacher