Abstract

In the communications of modern organizations, text sharing and knowledge management are mainly digital. The digital systems that frame many types of communication consist of, e.g., intranets and document sharing software that are occasionally exchanged for new systems. Employees have to adjust to modified routines and learn new systems, and management has to make decisions about digital systems and how these are to be integrated with work processes and knowledge management. In this article, we contribute to research on work-life literacies by highlighting the increasingly frequent issue of digital text sharing in modern workplaces through the study of commercial companies, mainly through ethnographic observations and interviews. The theoretical framework comes from New Literacy Studies where literacy practices, i.e., common patterns of using reading and writing, form a key concept. Moreover, the sociolinguistic concept of metadiscourse is applied in order to uncover the reflexive orientation of participating professionals towards digital text sharing. The results show that these professionals relate the combination of digital text sharing and technological and organizational change to problems, obstacles and potential risks; ambitions of enhancing digital text sharing may exclude certain groups, and changes in digital text sharing systems per se may cause professionals to lose control. These risks are often associated with access to information: a person who cannot access information in their organization has a lower degree of agency or power over their situation. The results are discussed in light of theories concerning modern work life from New Literacy Studies.

1 Introduction

Digital text sharing is paramount in the work life of today. Writing a text in a modern organization often entails sharing it with others through digital tools, both during the writing process and when the text is completed. Reading a specific text in the workplace requires having access to it, and locating it means having to read short texts, such as options within the digital system, entering passwords and creating search strings. Since recurring activities involving reading, writing and texts can be conceptualized as literacy practices (Barton and Hamilton 2000), we regard digital text sharing here as a literacy practice, as defined by New Literacy Research (herafter NLS, see Barton and Hamilton 2000; Street 2003; Papen 2005).

Literacy in the sense of writing has been the focus of a vast amount of research on workplace communication (e.g., Bremner 2006; Gunnarsson 1997; MacKinnon 1993), as well as certain professional text genres (e.g., Bhatia 1989; Fløttum et al. 2006). Research within an NLS perspective often shifts the perspective to that of the practitioners or participants in a study, so that writing and texts can be seen as phenomena necessary for getting core activities of the workplace done (Nikolaidou and Karlsson 2012; Tusting 2015). In doing so, compared to research on finished text products, NLS research sometimes brings previously backgrounded aspects of literacy to the foreground, e.g., the filling of forms in work life (Karlsson and Nikolaidou 2011; Tusting 2010) and the networking behind publishing academic texts (Lillis and Curry 2013). This article can be regarded as an attempt to bring to the foreground the aspect of digital text sharing in modern organizations (for the aim of the article, see below). Digital text sharing is here defined as acts of exchanging, submitting, searching or showing written information – which can be verbal or numeral – by means of a digital tool. The concept focuses on the actions and strategies of sharing as such, in a more narrow sense than the broader concept of digital communication (Blåsjö et al. 2021).

The empirical point of departure of this particular focus is that, while constructing data for our research project Professional Communication and Digital Media – Complexity, Mobility and Multilingualism,[1] there was a strong tendency for professionals in the studied companies to handle issues of digital text sharing and speak about doing so at great length. These professionals have to share documents regularly, and they frequently engage in discussions about where and how to share and access what. Dealing with knowledge management, they cannot avoid everyday matters such as setting reading permissions for access of information. The phenomenon of digital text sharing, including such “small” everyday practices as entering passwords and knowing where different information is available, is rarely the focus of empirical studies in applied linguistics, although it is well known to researchers through their everyday work (cf. Geisler 2003; Gillen 2014: 35–36).

A theoretical point of departure of this study is the acknowledged notion that in a changing society where common practices are dissolved and new ones emerge, there is an increasing need for making previously invisible or implicit practices explicit (Jaworski et al. 2004). “The transformation of time and space, coupled with the disembedding mechanisms, propel social life away from the hold of pre-established precepts and practices” (Giddens 1991: 20), and in this transformation individuals and institutions are urged to engage in an enhanced reflexivity on issues of power and agency: how do these societal and organizational changes influence the everyday agency of the individual (cf. Giddens 1984)? This type of reflexivity on and within modern institutions or organizations, or this phenomenon of making implicit practices explicit in the struggle for preserved or enhanced agency, we will return to in terms of metadiscourse.

There is an extensive interest in society and research on digital or online communication and social media, in the sense of Internet use and information literacies such as searching the web (e.g., Limbu 2018; Phan et al. 2011). Sharing is the basis for Web 2.0, the Internet and social media, where openness and visibility are fundamental values (cf. Deumert 2014; Marwick and Hargittai 2019). In this article, we narrow the focus to the sharing of information within organizations, where the protection of and limited access to information is (also) valued. Certainly, professionals in organizations use the Internet, but here we focus on internal information often protected by passwords and firewalls. Within organizations, the important issue is often how to share information with precisely the right people, avoiding information overload (Edmunds and Morris 2000) and security risks, while simultaneously facilitating smooth work processes and knowledge management, in order to nurture corporate growth. The difference between public use of digital media and professional use can also be described as a distinction between sharing as distribution and sharing as collaborating (cf. Jones and Hafner 2012).

Since technological development is so rapid, studies of specific tools soon become outdated. Consequently, research needs to focus on more general tendencies, such as the rapid changes per se: “Any sensible approach to conceptualising digital literacies must take account of rapidly changing environments, people’s agency and developing skills” (Gillen 2014: 38). In this article, we address both technological changes and organizational changes, as they are made relevant by the participants of the study. Consequently, we will touch upon issues such as how people deal with technological changes, in relation to digital text sharing in our case, and how professionals relate to digital changes intertwined with organizational changes. On the whole, we aim to contribute to research on work-life communication and professional literacies by highlighting how digital text sharing in modern workplaces is intertwined with issues of change, agency and power. We approach this through a case study of commercial companies with offices in Sweden and examine these in light of two interrelated research questions:

How can digital text sharing be metadiscursively constructed by professionals?

What can this metadiscourse reveal about tendencies of digital text sharing in relation to technological and organizational changes, agency and power in modern organizations?

In what follows, we first present the theoretical framework. After a section on methodology and data, we present the analysis, starting with brief results based on data from the overall research project, and continue with detailed analyses of two examples of data. Finally, we discuss the research questions.

2 Theoretical framework: literacy, power, agency and metadiscourse

Within NLS, communication is regarded as being integrated with social values, knowledge and ideas, and as constituting power relations between people and groups (Barton 2006; Street 2003). The difference between the NLS conception of literacy and a traditional one is that literacy is regarded as always related to different social practices, groups and discourses, in the sense that there are several different ways of reading and writing related to, e.g., the social practice of childcare (Tusting 2010), the social groups of academics (Lillis and Curry 2013), and the discourse of work-life surveillance (Karlsson and Nikolaidou 2016; Tusting 2015). The existence of different literacies is evident not least in the fact that a person needs more than basic skills of reading and writing to participate in different settings. In addition, knowing how to use texts in a functional way in different social practices or groups is a key competence (Barton and Hamilton 2000). Examples of texts mentioned in the literature are web pages, text messages and signs (Barton 2006: 23), user contributions to Internet sites (Papen 2010: 159), cargo information (Karlsson 2009) and digital forms (Barton 2009: 48). As mentioned above, texts and literacy practices can be backgrounded in the social settings (Barton 2006: 23) as their role is to get other things done.

Literacy is embodied and enacted by people in concrete ways such as writing a list, searching the Internet and reading an instruction. Such concrete, observable instances of literacy are called literacy events, defined as “activities which involve written texts” (Barton 2006: 24). Literacy events often recur, thus forming recognizable patterns, called literacy practices, “common patterns of using reading and writing in a particular situation where people bring their cultural knowledge to an activity” (Barton and Lee 2013: 12). Having been engaged in social practices, people have grown used to certain literacy practices over time. When the Internet was new, for instance, we were unsure how to handle it, but today most people are competent in searching for information there. People are more or less conscious about their literacy practices; these include “people’s awareness of literacy, constructions of literacy and discourses of literacy, how people talk about and make sense of literacy” (Barton 2006: 22). Today, the literacy practice of searching the Internet has a generalized label – “to Google” – that is often discussed. “Smaller” or more micro-level actions included in reading and writing are often regarded as literacy events. However, micro-level actions such as clicking OK or entering a password can also shape literacy practices when they are repeated or metadiscursively constructed (see below).[2]

As literacy practices are related to social practices, they also concern power relations (Barton and Hamilton 2000), for instance, in workplaces (Tusting 2015). These power relations include the status of the mode of writing versus other means of communication, the status of certain texts as dominant and visible compared to others, as well as the power of certain groups or authorities to enforce others to use the mode of writing or certain text genres (Barton and Hamilton 2012; Karlsson and Nikolaidou 2011; Tusting 2010). In this undertaking, the agency of the persons using writing may be limited or enhanced (Lillis 2013). In studying agency and power, NLS has partly related to the theory of “the new work order” (Gee et al. 1996; Karlsson 2009), which describes modern workplaces as seemingly less hierarchical, with workers expected to document and surveil their own work to a higher degree (Nikolaidou and Karlsson 2012). The documentation and self-surveillance tendency has also been observed in professional work, leading to less time for core activities (Tusting 2015). Moreover, an empirically based theoretical outline in NLS is that traditional texts with a long history and a formal structure (such as legal texts) tend to have a higher status, entailing wider agency than minor, short-lived texts (such as handwritten notes) (Barton and Hamilton 2012; Karlsson 2009). We wish to examine how digital text sharing corresponds to these theories on work-life literacy.

NLS theory is in line with the theory of metadiscourse, where a core notion is that discourse, communication and language use are always interrelated with social values and ideologies (Jaworski et al. 2004; Silverstein 2014).[3] Working from an ethnomethodological perspective (Garfinkel 1967), we wish to study how professionals in modern organizations conceptualize and make sense of relationships between digital text sharing and change. In this endeavour, we turn to the sociolinguistic concept of metadiscourse (or metalanguage, metapragmatics, metacommunication), i.e., how people speak about issues of communication and language (see Coupland and Jaworski 2004 on metalanguage and reflexivity).

The concepts of metadiscourse, metalanguage, metapragmatics and metacommunication have somewhat different definitions, and most of the literature applying these concepts deal with more “language-narrow” matters – such as metadiscursive labels for accents (Agha 2006) – compared to our study. Nevertheless, the general theory of metadiscourse is more generally applicable. Jaworski et al. (2004), for instance, refer to metalanguage as “how social groups value and orient to language and communication (varieties, processes, effects)” (p. 3), stating that it “needs to be conceptualised within as well as outside of or as an adjunct to language use” (p. 4), and Hanell (2018) investigates the metadiscursive comments of midwives to uncover their professional ideologies on what constitutes good communication. How the linguistic practices of digital text sharing are talked about in our data is conceptualized as metadiscourse or metadiscursive constructions in order to capture what lies behind the verbalized data in terms of social values, knowledge and ideas.

3 Methodology and data

The NLS methodology is based on discourse analysis and focuses on social aspects of literacies. Aspects such as social belonging, artefacts, identities, power and activities are related to data such as texts, observations and interviews (Barton 2009; Hamilton 2009; Tusting 2015; more on methods below).

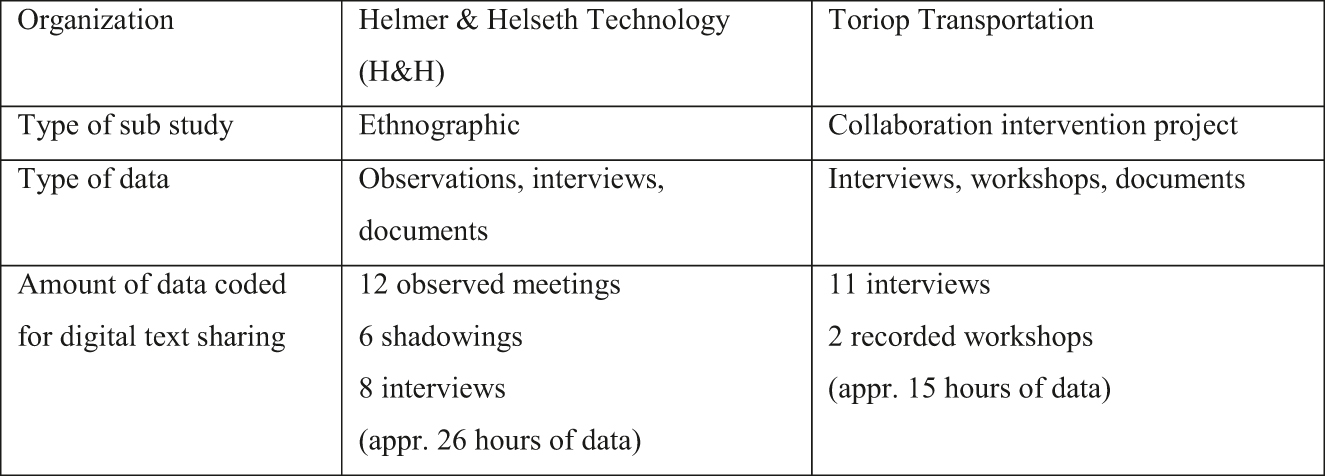

Our data stem from a three-year (2016–2019) research project entitled Professional Communication and Digital Media, which involves three organizations in the private sector. This article reports on empirical examples from two of these organizations. Figure 1 shows an overview of the coded (see below) data.

Overview of data (with pseudonyms for participating companies).

At Helmer & Helseth Technology (H&H), we conducted ethnographic field work over the course of a year. The company works with technological development and had gone through several reorganizations during the years prior to the study, as well as during our data construction. It operates nationally in Sweden but has many international contacts. Our research mainly focused on a primary participant, Per, manager in one of the departments. Following him during his work day, we observed several different activities, one of which was a meeting that is used as an example in this article. The other persons who participated in the meeting are presented in the beginning of the results section about H&H below.

In one sub-study, we collaborated with Toriop Transportation, a multinational transportation manufacturer that was planning a new global intranet and wished to discuss with us how to deal with different languages and translations within this intranet. We conducted workshops and interviews, mainly with participants in internal project groups working with the intranet. Some of these had managerial positions, and some were experts in areas such as IT, translation and communication. The semi-structured interviews were held at the Toriop office and lasted 40–120 min. The purpose of this data construction was to obtain input on what the participants regarded as important issues of language choice and translation in the intranet. These data are used to answer the research questions of this article (after approval by the participants). All of the 11 conducted interviews were coded, and the three interviews that include the most relevant data are cited in this article. These three interviewees are presented in the beginning of the results section covering Toriop below.

The third company was an international firm in the medical business where we did field work at the Swedish office. Field work and coding of data from this firm strongly contributed to the observed tendency mentioned above, and these data contribute to the general findings below (see also Blåsjö et al. 2021).

All interview and interaction data were roughly transcribed; the meeting transcript used in this article has been complemented with descriptions of relevant gestures. The transcripts below are presented in their original Swedish with English translation. In interview transcripts, we have excluded minimal responses from the interviewer (cf. Tusting 2015).

The data were analyzed with the tool NVivo in accordance with the following analytic procedure:

Code in NVivo for instances where participants make digital text sharing relevant.

Study these instances inductively to discover characteristics of the phenomena relevant to the research questions.

Formulate themes from step 2.

Provide participant feedback on results and make subsequent adjustments.

Choosing data to present in the article, we selected examples that highlight the phenomenon of technological and organizational change, in order to approach the theme of the special issue, the aim of this article and research question 2:[4]

Example 1, which covers authentic real-time meeting interaction when the participants who mainly worked with core activities spontaneously speak about digital text sharing and changes (professionals at H&H discussing digital changes partly due to reorganizations).

Example 2, which covers aspects expressed in interviews capturing digital text sharing as conceptualized by participants in management and project-leading positions (professionals at Toriop, in interviews, speaking of challenges and possibilities when launching a new intranet).

The overall research project was performed in close collaboration with the companies, with whom we signed confidentiality agreements. Participants were given the opportunity to read and react to interpretations and publications, as well as to react to how data were used.

4 Results

The results are presented here, starting with roughly quantitative general findings from the total coded data of the overall research project, followed by deeper qualitative analyses of the two chosen examples.

4.1 General findings

Step 1 in the analytical procedure described above, i.e., coding the total data for instances where participants make digital text sharing relevant, resulted in over 2/3 of the data items including coding for digital text sharing (each interview and observation defined as one item). An average of approximately 1/10th of the total data were covered with the digital text sharing code. Consequently, digital text sharing was a frequent topic and concern for the participants in situations that we observed, such as meetings, working with emails and other tasks at the computer (see Blåsjö et al. 2021 for more details).

4.2 “What am I supposed to do when I’ve written an application?” Metadiscourse about change at H&H Technology

In the first example, a meeting at H&H, the communications manager Berte informed about how the company worked with information issues such as intranet and other digital communication during a time of reorganization. The meeting, which she also chaired, was a virtual meeting with several remote participants. Additionally, there were six persons physically present, excluding the researcher: Berte, a communications manager; Per, the head of the unit and subject specialist; Ellida and Johan, senior project managers; Rebecka, a financial officer; and Gina, an assistant. They were seated at a rectangular table in a room with a large screen on a wall.

At the end of the meeting, Berte asks the participants if they have comments or questions. A discussion of greater than 15 min takes place, in which a great deal of problems are raised that focus on the issue of the workplace having exchanged digital tools several times recently, that several of the tools are in use parallel to each other, and that employees are finding it hard to know about all the systems, routines and passwords to access these different tools. Ellida, a senior project manager who often works with reports and project applications, begins the discussion about digital tools (OPI and DI mentioned are previous organizational labels):

| Translation | Original | |

| Ellida | since a while back I have some kind of (.) exhaustion when it comes to learning new systems (.) and (.) it gets harder and harder because I’ve learnt so many systems (.) and they are constantly replaced I don’t remember any longer if it was (.) this was applicable the last six months or if it’s applicable now | sen en tid har jag nån slags (.) utmattning när det att lära mig nya system (.) och (.) det blir svårare och svårare eftersom jag lärt mig så många system (.) och de byts ut hela tiden jag kommer inte ihåg längre om det var (.) det här gällde förra halvåret eller om det gäller nu |

| Berte | no (.) and I can understand that it was it was an issue that I forgot | nej (.) och det förstår jag det var det var en punkt som jag glömde |

| Ellida | yes | ja |

| Berte | that that came up also in (.) that it’s very fragmented (.) where one finds the information today | som som kom upp också i (.) att det är väldigt fragmenterat (.) var man hittar informationen idag |

| Ellida | yes and it’s not (.) it’s not that now we have CDM we used to have Maconomy we had (.) some other system before we had an economics system (.) Dynamics as OPI then Dynamics as DI now we will | ja och det gäller inte (.) det gäller inte det nu har vi CDM vi hade Maconomy vi hade (.) nåt annat ekonomisystem innan vi har haft ett ekonomisystem (.) Dynamics som OPI sen Dynamics som DI nu ska vi |

| Berte (overlapping) | yes [laughs] | ja |

| Ellida | have Dynamics maybe as H&H or who knows […] it concerns every every matter what am I supposed to do when I’ve written an application (.) it changes every sixth months | ha Dynamics kanske som H&H eller vem vet […] det gäller varenda varenda punkt vad ska jag göra när jag skrivit en ansökan (.) det förändras för varje halvår |

| Berte | mm | mm |

| Ellida | but simply exhausted to keep track of where I’m supposed to when I’ve finished a report (.) who to submit to (.) it to (.) it’s not the same thing as last time I wrote a report which may be just two months ago [hands firmly placed apart on the table] | men helt enkelt utmattad att hålla reda på var ska jag när jag skrivit klart en rapport (.) vem ska jag lämna till (.) den till (.) det är inte samma som gällde förra gången jag skrev en rapport vilket var kanske bara två månader sen |

| Berte | [laughs] yes | ja |

| Ellida | I mean | alltså |

| Berte | yes | ja |

| Ellida | you are totally exhausted | man är helt slut |

| Berte | I understand there is an unnecessary waste of energy on this that you could use for something else | jag förstår det går ju onödig energi till det nån som man kunde ägna åt annat också |

| Ellida | yes | ja |

| Berte | plus it becomes ineffective | plus att det blir ineffektivt |

Ellida’s concern above relates to texts that she is supposed to deliver and share with her colleagues. The problem concerns change, as she points to the problems induced by the digital tools being repeatedly replaced. She recounts different IT systems used during phases of reorganization, highlighting digital text sharing as an aspect of individual stress and problematic working environment. The communications manager Berte supports her, but highlights an aspect of structure and efficiency, i.e., more from an organizational or management perspective. Thus, the metadiscourse is constructing digital text sharing as something that the participants are bound to or ruled by, limiting their agency. Further, it touches upon both an individual perspective and an organizational perspective.

Directly after this, the responsible manager, participating at a distance, reports from the chat function of the distance meeting tool: several persons have expressed worries about having to learn additional systems. Berte adds that there are presently, due to reorganization, three organizational units working with their specific systems and intranets that make the situation for the communication unit complicated. Here, it is confirmed that the problem with changing digital tools is a general one, not only for Ellida.

After the meeting has formally ended, and the distance participants are logged out, the discussion on site continues for about 5 min:

| Translation | Original | |

| Rebecka | soon in a couple of years you will have to learn a new system | snart om ett par år får du lära dig ett nytt system |

| Ellida | […] it’s not that (.) it’s difficult many of us have PhDs we have the capability to learn this (.) but it’s about when you have twenty different systems [places her hands on table tapping three times from left to right] | […] det är ju inte det att (.) det är svårt många av oss är disputerade vi har förmågan att lära oss det här (.) men det handlar när du har tjugo olika system |

| Berte | yes exactly (.) and when it’s also constantly changing | ja precis (.) och när det hela tiden också ändras |

| Ellida | and it’s constantly changing | och det hela tiden ändras |

| Berte | yes | ja |

| Ellida | at the same time as it’s not my focus (.) I’m supposed to have my focus over here [reaches far back on her left side] this thing [hands back on table] should only help me or someone else in the organization | samtidigt som det inte är mitt fokus (.) jag ska ha mitt fokus här borta det här ska bara hjälpa mig eller nån annan i organisationen |

| Berte | yes | ja |

| Rebecka | mm | mm |

| Ellida | […] right now we have introduced Lime (.) and (.) well at the same time as it is with the library and (.) all other routines that I don’t really know if they (.) sort of | […] just nu har vi introducerat Lime (.) och (.) ja samtidigt som det nu är med bibliotek och (.) alla andra rutiner som jag inte riktigt vet om de (.) om de liksom |

| Berte | yes | ja |

| Ellida | well one hardly knows how should I search for old reports (x) like you can’t cope | ja man vet knappt hur ska jag söka på gamla rapporter (x) man orkar inte liksom |

| Berte | no exactly | nej precis |

Here, Rebecka is also supporting Ellida. Ellida’s take is that this is not an issue of lacking competence but that the changes in themselves are the problem, adhering to her perspective of individual stress and working environment. The individual focus can also be observed when she illustrates different areas of responsibility in the space around her: core activities and administration related to the digital tools, respectively. The administration or digital systems, she claims, should be of help, not something that takes focus from her core activities. She also seems to mark time periods or changes by tapping her hands on the table in front of her. Other metadiscursive constructions here are aspects of learning (new systems) and searching (for texts).

Then, Berte brings up that employees are regularly prompted to change their passwords to digital information systems, and that different requirements, e.g., how many characters of which type, are difficult to manage. The group engages in this issue:

| Translation | Original | |

| Per | switch three times then you can switch back again to the one you had before […] |

byt tre gånger sen kan du byta tillbaka till det du hade förut

[…] |

| Rebecka | no but otherwise you can have a beginning and then you switch you have some digits and then you switch the digits until it (.) it ends | nej men annars kan man ha början och så byter man har man några siffror och så byter man siffrorna tills det (.) det tar slut |

| Johan | but they do end […] | men de tar ju slut […] |

| Rebecka | well but then take enough digits so that they last a while | ja men då ta ta tillräckligt många siffror så att det räcker en stund |

The participants raise limitations and rules within systems, such as how many times you must change your password before you can go back to the original one. They report on different strategies for coping, e.g., adding different digits to existing passwords. Here, the problem is discussed as an individual one, not as an organizational or management issue.

To sum up, the metadiscourse on local use of digital text sharing constructs digital text sharing as an immense problem of being bound or ruled by different systems that are constantly changed. Changes at an organizational level are emphasized and connected to digital changes – each new organizational arrangement has come with new tools for digital text sharing. The problem is discussed both from an individual and an organizational perspective, being related to literacy practices such as writing, sharing, and searching for reports, as well as entering passwords. The metadiscourse about the problems raised can be regarded as risk discourse. The participants also bring up the competence of knowing which systems are in use for what, i.e., knowledge about the local digital infrastructure; thus, handling passwords and knowledge about the digital infrastructure are parts of the metadiscourse about required digital literacy. The individuals are constructed as searching, learning, (not) remembering, (not) finding and (not) knowing enough in relation to digital text sharing, while the management is constructed as replacing digital systems with new ones.

4.3 “Then you choose – these people will be able to see”: metadiscourse about a planned global intranet at Toriop transportation

Toriop had several local intranets in different parts of the world, as well as different systems for information sharing and project groups. In bringing these together to a global corporate intranet, here named Collanet, issues of translation and language choice were in focus for the part of the project that we, as linguists, participated in mainly through interviews. Three of the interviews are cited in this article: with Mollie, head of the Collanet intranet project group; Clarissa, communications specialist of the project group; and Oliver, IT specialist of the project group. Below, we present the most dominant themes of metadiscourse on digital text sharing coming from the analytic procedure described above.

One of these metadiscursive themes is change. For instance, the project manager, Mollie, states that the biggest challenge with the intranet project is keeping it user-friendly while keeping up with technical changes, “providing something people can use at least for the time being without things getting too split up […] helping people to know how to work and where to find information […] that it’s not just changing all the time”. She seems to say that technical development can prevent staff from practically handling digital tools such as the intranet. Moreover, Mollie mentions the role of the new intranet in the changes of the organization over time:

| Translation | Original | |

| Mollie |

and then you know it’s also the case that (.) Torip as a company (.) goes through a journey of change […] by like (.) digitalization and so on (.) and (.) well new business models will arise and so on […] everyone working at Toriop needs to like keep up with this change and then the intranet is an important (.) carrier of that communication you know […]

there too we have like (.) linguistic but also of course cultural challenges but that (.) like how can the intranet support (.) it’s not sufficient that it’s like well-educated (.) professionals maybe that can read English that can take this in […] Toriop has […] like this family feeling […] and (.) then if this family goes through a change (.) then you need to communicate about it |

och sen är det ju också så att (.) Toriop som företag (.) genomgår ju en förändringsresa […] i och med liksom (.) digitalisering och så vidare (.) och (.) ja nya affärsmodeller kommer att uppstå och så vidare […] alla som jobbar på Toriop behöver liksom följa med i den här förändringen och då är ju intranätet en viktig (.) bärare av den kommunikationen […]

även där har vi ju liksom (.) språkliga men även så klart kulturella utmaningar liksom men att (.) liksom hur kan intranätet stötta (.) det räcker inte med att det är liksom välutbildade (.) tjänstemän kanske som kan läsa på engelska som kan ta till sig det […] Toriop har ju […] liksom familjekänslan […] och (.) om då den här familjen genomgår en förändring (.) då behöver man ju kommunicera kring det |

Here, Mollie highlights the importance of a global intranet for communicating corporate changes over time. In doing so, she does not emphasize the mere distribution of news from management to staff, but all employees’ feelings of belonging. In this concern, she mentions linguistic and cultural issues of the intranet, as well as different categories of employees, as being important for everyone really being able to access all necessary information.

Related to change, a metadiscursive theme of efficiency and knowledge management in a corporate perspective is shown. A tendency in the interviews is an apprehension that a key function of the intranet is to serve as a conduit from the management to all employees with respect to, e.g., ruling documents and policies, and that this may be difficult to accomplish. Communications specialist Clarissa addresses this issue (‘One Toriop’ mentioned is a corporate key value):

| Translation | Original | |

| Clarissa | if the reason is that we invest in a (.) big global intranet to have like One Toriop (.) then you have to bear that in mind when you decide which (.) texts are to be translated (.) and the worst thing is that (.) in my view that’s all that comes from (.) everything everything that (.) concerns global matters needs to be translated and then it’s practically (.) everything if we say that everything should be there (.) and be accessible for everyone and that we should have transparency and so forth |

om anledningen är att vi investerar i ett (.) stort globalt intranät för att vi ska ha liksom One Toriop (.) då måste man ha det i åtanke när man beslutar vilka (.) texter som ska översättas (.)

och det värsta är att (.) i min värld så är det allting som kommer från (.) allt allt det som (.) rör saker globalt behöver översättas och då är det i stort sett (.) allt om vi säger att allting ska ligga där (.) och vara tillgängligt för alla och vi ska ha transparency och så vidare |

Clarissa seems to mean that a big investment in digital technology can be wasted if important parts of the texts within the intranet are not accessible to certain people due to language issues. She uses the word ‘transparency’ quite frequently in the interviews (here even used in English in the otherwise Swedish utterance); i.e., digital text sharing is metadiscursively constructed as an ability to look through something, without being obstructed by opacity. Voicing a user perspective, she adds:

| Translation | Original | |

| Clarissa | the professional sites for example where you can actually find information that you may (.) need (.) that is best practice (.) aha did they do that way in (.) [country 1] how smart (.) maybe we can do that in [country 2] too (.) but how are you going to get that if you don’t understand it and you can’t go in and read on the [language 1] site | de professionella portalerna till exempel där du faktiskt kan hitta information som du kanske (.) behöver (.) alltså best practice (.) jaha har de gjort så i (.) i [land 1] vad smart (.) så kanske vi kan göra i [land 2] också (.) men hur ska du kunna få det om du inte förstår det och du kan ju inte gå in och läsa på på [språk 1] sidan |

A driving force behind the intranet is to improve knowledge management in the sense that new knowledge at one global site can be accessed in another country and used there to support corporate growth. Oliver, the IT specialist, mentions another aspect of this. He claims that “some people have a tendency to lock information in”. As the reason for this, he refers to internal studies showing that employees may hide information during a development process, when the information is “just a draft”. He says that people do not always change the accessibility when a project is finished: “It [the information] may be sensitive now that we are in the process of developing a new project, but when we have developed it, it’s totally harmless”. According to Oliver, internal studies show that only 3% of staff who would need access to information from previous projects actually do have it. Even if this aspect seems assigned to employees’ actions, it is strongly related to digital text sharing since it is through the digital tools that they are supposed to share new knowledge, and it is in this context that Oliver brings it up.

Another theme is the design of the intranet and related digital tools. The interviewees speak about the design of the intranet as including different places for different groups, i.e., an issue of how to share information. The planned intranet will include special parts or areas for groups to give each other access to certain material. Mollie says:

| Translation | Original | |

| Mollie | that anyone can start a sort of a (.) group (.) collaboration area (.) like here we store our documents and then I invite some people to this collaboration area (.) and it’s like a limited (.) then you choose (.) these people will be able to see | att vem som helst kan starta nån slags sån här (.) grupp (.) samarbetsyta (.) liksom här lagrar vi våra dokument och så bjuder jag in lite folk till den här samarbetsytan (.) och det är ju liksom en begränsad (.) alltså då väljer man ju de här ska kunna se |

Mollie mentions the intranet design from a user perspective; all employees are meant to be able to set up digital areas where they can choose whom to invite. Here, digital text sharing is metadiscursively constructed as a physical place with similarities to a house where you invite guests. Places are also mentioned by Oliver, speaking from a designer perspective:

| Translation | Original | |

| Oliver |

generally we have a number of big access groups (.) so when you set up a (.) site or segment like this (.) then you can choose which access groups would have reading (.) permission then […] so on that level you can set up access groups

then we have these (.) so-called project areas or a bit like Sharepoint and so (.) and there apart from the access groups (.) you can control for individuals (.) it’s only these persons who will (.) [have] access or (.) that it’s kind of moderated so that everyone can find their way to it (.) but to read (.) then you have to knock on the door (.) and then you get (.) approve on that |

generellt så har vi ett antal stora accessgrupper (.) så när man sätter upp en sån här (.) site eller segment(.) då får man välja vilka accessgrupper ska ha läs (.) rättighet då […] så att på den nivån kan man sätta accessgrupper

sen har vi såna här (.) så kallade projektytor eller lite som sharepoint och så (.) och där förutom de här accessgrupperna (.) då kan man ju också styra det på individ (.) det är bara de här personerna som ska (.) access eller (.) att den är så här typ moderated så att alla kan hitta till den (.) men för att läsa (.) då får man knacka på dörren (.) och så får man (.) approve på det |

Oliver first describes the design through use of the words ‘site’, ‘segment’ and ‘access groups’ with different reading permissions. We interpret these as general choices done at management level. He then refers to other parts of the digital structure as ‘project areas’ where access can be set for, and requested by, individuals. We interpret this as referring to choices done at a local and user level. The actions or literacy practices of digital text sharing are formulated as something to ‘set (up)’ and ‘control’, and also to knock on the door (related to physical places) and getting a sort of key (‘approve’).[5]

The design of the intranet also allows for individual users to make their own settings for what to access on their own start page (interviews with Clarissa and Oliver). These settings include choice of language, another metadiscursive theme apparent in the interviews. A language that users do not understand is an obstacle for text sharing in itself – this may seem self-evident, but it appears as a specific problem when using a global intranet where users may find texts in an unknown language when searching. Searching can also be obstructed due to language choice and competencies. Oliver mentions that if the design does not include automatic translation, people may have to find out tricks of their own to search for information in another language. That is, if a person knows only Swedish and English, how would s/he write the search string for information that may only be available in another language? This is an example of the issue of language barriers for digital text sharing, mentioned by the interviewees.[6]

Apart from linguistic competencies, sheer digital competencies are unevenly distributed within the company and are, of course, relevant to digital text sharing in a global intranet. The project group working with Collanet shows concerns about how these could become obstacles to the free access of information in the intranet. As Clarissa formulates it, “everyone has completely different maturity both plain (.) Internet and computer and digital knowledge-wise”. More evidence of this concern is Mollie reporting on some people in other countries who did not know about Google. Partly due to differing educational levels, employees around the world have very different digital competence levels.

To summarize, the interviewees, partly due to the focus of the intranet project, speak a great deal about potential obstacles to intended transparency. Digital text sharing here is related to language in the sense that access is restricted if the user does not have competencies in the language of a certain information in the intranet, and that employees can use their own settings for language. Apart from linguistic competencies, digital competencies are mentioned as an important factor; the company cannot expect all employees to have sufficient digital competencies or literacies. The digital competencies of the staff are, in turn, related to change in the sense that the technical development is rapid. Additionally, informing staff about changes in the organization is a key function of the intranet, related to efficiency and sustainable knowledge management that is important for corporate growth. The participants also speak about the design of the digital structures as places accessible to different groups. Thus, digital text sharing is metadiscursively constructed as (physical) places similar to houses with different rooms that can be open or locked. Many of these aspects can be related to risk discourse, in which the interviewees reflect on existing and future obstacles, such as if the ambition of including all worldwide employees in a joint intranet will instead obstruct communication. Within the metadiscourse, individuals are constructed as inviting, reading and choosing in relation to digital text sharing, while the management is constructed as deciding, choosing and setting up.

5 Discussion

In this section, we discuss the two research questions.

5.1 Metadiscourse about digital text sharing

As Garfinkel (1967: 4) states, “Members’ accounts are reflexively and essentially tied for their rational features to the socially organized occasions of their use […]” In this article, the reflexive, metadiscursive statements of the participants were situated in a real-time meeting with each other and in discrete interviews with researchers, respectively. Consequently, they need to be interpreted as utterances grounded in different social practices. Moreover, participants belonged to differing professional groups: people working with digital media as a support to their core activities, management representatives planning a digital communication project, and IT specialists working with the design of digital tools. This diversity of data can be regarded as a weakness, but also as a strength with regard to validity. In regard to reliability, we wish to remind our readers that the results come from the overall project from which the data presented in this article are examples.

In speaking about the design, digital text sharing is metadiscursively constructed as places for different groups, similar to houses with rooms, to knock on the doors of, to get keys for, etc. The participants construct digital text sharing as something relatively physical or material (cf. Björkvall and Karlsson 2011). In addition, at both companies, they speak about obstructions to literacy practices such as presenting information to staff, searching for and submitting reports, and sharing knowledge about projects. Here, language barriers constitute a problem in the global company, as do different levels of digital competencies. Obstructions are also risks, and in the two empirical examples, risks with digital text sharing are constructed as having both an individual perspective (e.g., stress) and a management perspective (e.g., exclusion instead of inclusion).

Furthermore, individuals are constructed as learning, inviting, reading, finding, choosing, etc., in relation to digital text sharing, while managements are constructed as replacing, deciding, choosing and setting up. This result confirms the notion of literacy as an issue of power and agency (Barton and Hamilton 2000, 2012; Lillis 2013). In relation to this, digital text sharing is also metadiscursively constructed as an issue of efficiency and corporate growth, i.e., as an issue important for the management level of organizations.

5.2 Digital text sharing related to change, agency and power

A substantial part of the digital literacies required in today’s work life has to do with change. The participants in this study speak about the challenge of keeping track of changes in the digital information systems of their workplace – whether as managers planning for future changes or as employees struggling with their daily activities (cf. Nikolaidou 2011). The competencies required include different levels, such as a general macro-level knowledge of the digital environment of the workplace (e.g. which systems are in use for what, which digital group area is the appropriate for this issue) and a detailed micro-level knowledge of practical tricks for constructing one’s passwords, or having the competence to search for information in a language that one has not mastered. Both levels, but especially the micro-level, can be regarded as linguistic competencies; the overall interaction (i.e. the general linguistic function of communication and dialogue) between tool and user in a workplace is dependent on shared knowledge on where and how to communicate (cf. Swarts 2008), and placing every single character in the right position in a search string or password (i.e., a linguistic structure) is fundamental for digital text sharing. Consequently, knowing about and adjusting to changes between and in tools, as well as changes in required user input, are fundamental parts of communication competencies and digital literacies.

In turn, these communication competencies and digital literacies are related to agency and power (Barton and Lee 2013; Gillen 2014; Jones and Hafner 2012). We have seen how employees can experience their sense of agency as being threatened when faced with constant change: how would they perform their work in core activities when digital practices repeatedly changed (see also Blåsjö et al. 2021)? Additionally, digital changes as part of a management strategy could be inferred from the analyses, both in the inclusion strategy at Toriop to use a new intranet as a tool and in the changing management at H&H implementing new digital systems to mark a reorganization (cf. Tusting 2015). Our analyses also imply that even professionals with high status, such as senior project managers, have to engage in trivial, “small” literacy practices such as remembering passwords and using tricks for searching in another language. This finding is not quite congruent with the theoretical outline from NLS that minor texts are related to low-status occupations (Karlsson 2009), but rather confirms other results from NLS about “the new work order” dissolving the boundaries between high- and low-status work (Nikolaidou and Karlsson 2012; Tusting 2015). The increasingly complex relationships between literacy, digitalization, globalization and power among different groups in work life has been briefly illustrated in this article.

In doing so, the study points to an awareness of risks concerning digital text sharing combined with change: a person’s access to information within their organization is crucial for their agency and social inclusion, and this access may be threatened by technical and organizational changes. An ambition to include all employees through a new global intranet also brings risks of exclusion due to differences in linguistic and digital competencies. The implementation of new digital tools for text sharing may restrain the possibilities for professionals to access and share information. In this article, we have studied the metadiscourse about such risks among the professionals, i.e., their verbalized reflexive statements of perceived conditions. This study has contributed with one of several potential perspectives on the relationships between, on the one hand, digital text sharing and literacy and, on the other hand, change, agency and power – an issue intricate and important for both practical work-life communication and literacy research.

References

Agha, Asif. 2006. Language and social relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511618284.Suche in Google Scholar

Barton, David. 2006. The significance of a social practice view of language, literacy, and numeracy. In Lynn Tett, Mary Hamilton & Yvonne Hillier (eds.), Adult literacy, numeracy and language: Policy, practice, and research, 21–30. Maidenhead: Open University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Barton, David. 2009. Understanding textual practices in a changing world. In Mike Baynham & Mastin Prinsloo (eds.), The future of literacy studies, 38–53. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9780230245693_3Suche in Google Scholar

Barton, David & Mary Hamilton. 2000. Literacy practices. In David Barton, Mary Hamilton & Roz Ivanič (eds.), Situated literacies, 7–15. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Barton, David & Mary Hamilton. 2012. Local literacies: Reading and writing in one community. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203125106Suche in Google Scholar

Barton, David & Carmen Lee. 2013. Language online: Investigating digital texts and practices. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Björkvall, Anders & Anna-Malin Karlsson. 2011. The materiality of discourses and the semiotics of materials: A social perspective on the meaning potentials of written texts and furniture. Semiotica 187. 141–165.10.1515/semi.2011.068Suche in Google Scholar

Blåsjö, Mona, Carla Jonsson & Sofia Johansson. 2021. “I don’t know if I can share this.” Agency and sociomateriality in digital text sharing of business communication. Journal of Digital Social Research 3(3). 1–31.10.33621/jdsr.v3i3.78Suche in Google Scholar

Bhatia, Vijay K. 1989. Legislative writing: A case of neglect in EA/OLP courses. English for Specific Purposes 8(3). 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/0889-4906(89)90014-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Bremner, Stephen. 2006. Politeness, power, and activity systems. Written Communication 23(4). 397–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088306293707.Suche in Google Scholar

Coupland, Nikolas & Adam Jaworski. 2004. Sociolinguistic perspectives on metalanguage: Reflexivity, evaluation and ideology. In Nikolas Coupland & Adam Jaworski (eds.), Metalanguage: Social and ideological perspectives, 15–52. Berlin: De Greuyter.10.1515/9783110907377.15Suche in Google Scholar

Deumert, Ana. 2014. Sociolinguistics and mobile communication. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.10.1515/9780748655755Suche in Google Scholar

Edmunds, Angela & Anne Morris. 2000. The problem of information overload in business organisations: A review of the literature. International Journal of Information Management 20(1). 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0268-4012(99)00051-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Fløttum, Kjersti, Trine Dahl & Torodd Kinn. 2006. Academic voices: Across languages and disciplines. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.10.1075/pbns.148Suche in Google Scholar

Garfinkel, Harold. 1967. Studies in ethnomethodology. Cambridge: Prentice-Hall.Suche in Google Scholar

Gee, James P., Glynda Hull & Colin Lankshear. 1996. The new work order: Behind the language of the new capitalism. Boulder, CO: Westview.Suche in Google Scholar

Geisler, Cheryl. 2003. When management becomes personal: An activity-theoretic analysis of Palm technologies. In Charles Bazerman & David Russel (eds.), Writing selves/writing societies: Research from activity perspectives, 125–158. Fort Collins, CO: WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/books/perspectives/selves-societies/ (accessed 2 December 2020).10.37514/PER-B.2003.2317.2.04Suche in Google Scholar

Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Gillen, Julia. 2014. Digital literacies. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315813530Suche in Google Scholar

Gunnarsson, Britt-Louise. 1997. The writing process from a sociolinguistic viewpoint. Written Communication 14(2). 139–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088397014002001.Suche in Google Scholar

Hamilton, Mary. 2009. The social context of literacy. In Meryl Wilkins & Anne Paton (eds.), Teaching adult ESOL: Principles and practice (developing adult skills), 7–27. Maidenhead: Open University.Suche in Google Scholar

Hanell, Linnea. 2018. Anticipatory discourse in prenatal education. Discourse & Communication 12(1). 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481317735708.Suche in Google Scholar

Jaworski, Adam, Nikolas Coupland & Dariusz Galasiński. 2004. Metalanguage: Why now? In Nikolas Coupland & Adam Jaworski (eds.), Metalanguage: Social and ideological perspectives, 3–8. Berlin: De Greuyter.10.1515/9783110907377.3Suche in Google Scholar

Jones, Rodney H. & Christoph A. Hafner. 2012. Understanding digital literacies: A practical introduction. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.10.4324/9780203095317Suche in Google Scholar

Jonsson, Carla & Mona Blåsjö. 2020. Translanguaging and multimodality in workplace texts and writing. International Journal of Multilingualism 17(3). 361–381.10.1080/14790718.2020.1766051Suche in Google Scholar

Karlsson, Anna-Malin. 2009. Positioned by reading and writing: Literacy practices, roles, and genres in common occupations. Written Communication 26(1). 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088308327445.Suche in Google Scholar

Karlsson, Anna-Malin & Zoe Nikolaidou. 2011. Writing about caring: Discourses, genres and remediation in elder care. Journal of Applied Linguistics & Professional Practice 8(2). 123–143.10.1558/japl.v8i2.123Suche in Google Scholar

Karlsson, Anna-Malin & Zoe Nikolaidou. 2016. The textualization of problem handling: Lean discourses meet professional competence in eldercare and the manufacturing industry. Written Communication 33(3). 275–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088316653391.Suche in Google Scholar

Limbu, Marohang. 2018. Digital and global literacies in networked communities: Epistemic shifts and communication practices in the cloud era. In Miltiadis D. Lytras (ed.), Information and technology literacy: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications, 1665–1687. Pennsylvania: IGI Global.10.4018/978-1-5225-3417-4.ch085Suche in Google Scholar

Lillis, Theresa. 2013. The sociolinguistics of writing. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.10.1515/9780748637492Suche in Google Scholar

Lillis, Theresa & Mary Jane Curry. 2013. Academic writing in a global context: The politics and practices of publishing in English. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

MacKinnon, Jamie. 1993. Becoming a Rhetor. Developing writing ability in a mature, writing-intensive organization. In Rachel Spilka (ed.), Writing in the workplace, 41–55. Carbondale/Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Marwick, Alice & Eszter Hargittai. 2019. Nothing to hide, nothing to lose? Incentives and disincentives to sharing information with institutions online. Information, Communication & Society 22(12). 1697–1713. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2018.1450432.Suche in Google Scholar

Nikolaidou, Zoe. 2011. The use of activity theory in literacy research: Working and developing a vocational portfolio and the interaction of the two activities. Literacy and Numeracy Studies 19(1). 3–18.10.5130/lns.v19i1.2415Suche in Google Scholar

Nikolaidou, Zoe & Ana-Malin Karlsson. 2012. Construction of caring identities in the new work order. In Charles Bazerman (ed.), International advances in writing research: Cultures, places, measures, 507–519. Anderson, S. C.: Parlor Press.10.37514/PER-B.2012.0452.2.28Suche in Google Scholar

Orlikowski, Wanda J. & JoAnna Yates. 1994. Genre repertoire: The structuring of communicative practices in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly 39(4). 541–574. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393771.Suche in Google Scholar

Papen, Uta. 2005. Adult literacy as social practice: More than skills. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203347119Suche in Google Scholar

Papen, Uta. 2010. Writing in health care contexts: Patients, power and medical knowledge. In David Barton & Uta Papen (eds.), The anthropology of writing: Understanding textually-mediated worlds, 145–169. London: Continuum.Suche in Google Scholar

Phan, Michel, Ricarda Thomas & Klaus Heine. 2011. Social media and luxury brand management: The case of Burberry. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing 2(4). 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2011.10593099.Suche in Google Scholar

Silverstein, Michael. 2014. Denotation and the pragmatics of language. In N. J. Enfield, Paul Kockelman & Jack Sidnell (eds.), The Cambridge handbook of linguistics anthropology, 128–157. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139342872.007Suche in Google Scholar

Street, Brian. 2003. What’s “new” in new literacy studies? Critical approaches to literacy in theory and practice. Current Issues in Comparative Education 5(2). 77–91.10.52214/cice.v5i2.11369Suche in Google Scholar

Swarts, Jason. 2008. Information technologies as discursive agents: Methodological implications for the empirical study of knowledge work. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication 38(4). 301–329. https://doi.org/10.2190/tw.38.4.b.Suche in Google Scholar

Tusting, Karin. 2010. Eruptions of interruptions: Managing tensions between writing and other tasks in a textualised childcare workplace. In David Barton & Uta Papen (eds.), The anthropology of writing. Understanding textually-mediated worlds, 67–89. London: Continuum.Suche in Google Scholar

Tusting, Karin. 2015. Workplace literacies and audit society. In Julia Snell, Sara Shaw & Fiona Copland (eds.), Linguistic ethnography: Interdisciplinary explorations, 51–70. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/9781137035035_3Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Mona Blåsjö and Carla Jonsson, published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Workplace communication in flux: from discrete languages, text genres and conversations to complex communicative situations

- Orienting to the language learner role in multilingual workplace meetings

- Negotiating belonging in multilingual work environments: church professionals’ engagement with migrants

- Changing participation in web conferencing: the shared computer screen as an online sales interaction resource

- Policing language in the world of new work: the commodification of workplace communication in organizational consulting

- “It’s not the same thing as last time I wrote a report”: Digital text sharing in changing organizations

- Regular Articles

- “It sounds like elves talking” – Polish migrants in Aberystwyth (Wales) and their impressions of the Welsh language

- Exploring lexical bundles in low proficiency level L2 learners’ English writing: an ETS corpus study

- Kingdom of heaven versus nirvana: a comparative study of conceptual metaphors for Christian and Buddhist ideals of life

- Linguistic multi-competence in the community: the case of a Japanese plural suffix -tachi for individuation

- Accent or not? Language attitudes towards regional variation in British Sign Language

- Validating young learners’ plurilingual repertoires as legitimate linguistic and cultural resources in the EFL classroom

- A corpus-based study of LGBT-related news discourse in Thailand’s and international English-language newspapers

- Academic emotions in giving genre-based peer feedback: an emotional intelligence perspective

- Detecting concealed language knowledge via response times

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Workplace communication in flux: from discrete languages, text genres and conversations to complex communicative situations

- Orienting to the language learner role in multilingual workplace meetings

- Negotiating belonging in multilingual work environments: church professionals’ engagement with migrants

- Changing participation in web conferencing: the shared computer screen as an online sales interaction resource

- Policing language in the world of new work: the commodification of workplace communication in organizational consulting

- “It’s not the same thing as last time I wrote a report”: Digital text sharing in changing organizations

- Regular Articles

- “It sounds like elves talking” – Polish migrants in Aberystwyth (Wales) and their impressions of the Welsh language

- Exploring lexical bundles in low proficiency level L2 learners’ English writing: an ETS corpus study

- Kingdom of heaven versus nirvana: a comparative study of conceptual metaphors for Christian and Buddhist ideals of life

- Linguistic multi-competence in the community: the case of a Japanese plural suffix -tachi for individuation

- Accent or not? Language attitudes towards regional variation in British Sign Language

- Validating young learners’ plurilingual repertoires as legitimate linguistic and cultural resources in the EFL classroom

- A corpus-based study of LGBT-related news discourse in Thailand’s and international English-language newspapers

- Academic emotions in giving genre-based peer feedback: an emotional intelligence perspective

- Detecting concealed language knowledge via response times