Abstract

The study challenges the dominant narrative that Romanian consumer and residential credit laws are a product of the country’s return to capitalism and the market economy, proposing an alternative interpretation. It demonstrates that the origins of Romanian consumer and residential credit laws lay in the pre-World War II and communist legislation that survived the 1989 Revolution. This shows that the communist legacy in consumer and residential credit is real and more enduring than expected and that communism did not differ from capitalism in this respect, other than how consumer and residential credit was organised. Using legal history and doctrinal analysis in a functional approach coupled with statistical and empirical data, the study proves the existence of a normative continuity between pre-and post-1989 Romanian consumer and residential credit laws that ended with the EU accession efforts. Finally, this continuity between communist and capitalist consumer and residential credit laws indicates functional similarities between the monarchic (capitalist) and communist legal systems, further undermining the relevance of political and economic ideology and the idea that communism was inimical to consumers and consumer or residential credit.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The Fundamentals of Consumer and Residential Credit

Historical Origins of Consumer Credit

Ideological Origins of Consumer and Residential Credit

Elements of Consumer and Residential Credit

Continuity in Transformation: Consumer and Residential Credit in Romania

Three Stages of Romanian History

The Emergence of the Consumer and Consumer and Residential Credit in Romanian Law

Modern Romania

Communist Romania

Contemporary Romania

Secured Credit for Residential Property

The Modern Period (1859–1947)

The Communist Period (1947–1989)

The Contemporary Period (1990–Present)

Categories of Consumers

Creditworthiness

Down-Payment Requirements

Duration and Cost of Credit

Risk-Mitigation Mechanisms

Enforcement and Cure of Default

Secured and Unsecured Credit for Consumer Goods

The Modern Period (1859–1947)

The Communist Period (1947–1989)

The Contemporary Period (1990–Present)

Categories of Consumers

Creditworthiness

Down Payment Requirements

Duration and Cost of Credit

Risk-Mitigation Mechanisms

Enforcement

Conclusions

References

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

1 Introduction

Discussing the legacy of communist consumer and residential credit laws in an EU Member State may seem anachronist. At first glance, the Romanian consumer and residential credit legal framework is a product of the country’s return to capitalism and the market economy following the 1989 anti-communist Revolution and EU accession efforts. Narratives provided by Romanian authorities, historians and academics support this view. Until 2022, the homepage of the National Authority for Consumer Protection in Romania stated that due to ‘political-ideological reasons’, the concepts of ‘society of consumption’ and ‘consumer protection’ could only circulate publicly after the fall of communism.[1] According to one of the most acclaimed Romanian historians, the Romanian communist system was utterly disinterested in the population’s consumption.[2] Such assertions suggest that since communist ideology was incompatible with consumerism and consumer protection, the latter are post-communist phenomena.

These misconceptions are even more evident concerning credit for consumers. The few legal academic works either downplay or ignore the impact of the 42 years of communist legal order (1947–1989) on consumer and residential credit laws.[3] Most authors addressing Romanian consumer and residential credit legislation begin with the transition period without acknowledging the historical background.[4] Peligrad traces the history of Romanian mortgage credit to the 19th century but completely overlooks the communist period, jumping to 1999 when the remaining communist laws were repealed.[5] Nicolae and Popa focus exclusively on the issues raised by the debt relief mechanisms implemented after the 2007–8 financial crisis.[6]

The legal academics’ disregard for the legislation adopted during the communist period appears to depend on the following assumptions: 1) communist law had no bearing on consumer finance (since consumer and residential credit was ideologically incompatible with communism), 2) the communist legislation and its heritage were erased by Romania’s return to capitalism and the adoption of the EU acquis, and 3) communist law was so different from current law that there is no reason to discuss or compare with it.

These explanations fail to consider that, between the 1947 abolition of the monarchy and the 1989 fall of communism, there was not a legal void but 42 years during which the Romanian society, economy and legislation continued to function and evolve. They also fail to explain consumer and residential credit’s apparent normative and functional continuity, which survived the transition from communism to capitalism until the implementation of the EU acquis. Ignored by the legal literature, this phenomenon is better evidenced by socio-economic works supported by the existing (albeit incomplete) statistical data.

According to these latter studies, discarding the potential communist legacy in consumer finance is misguided. Manko eloquently demonstrated an enduring communist legacy in Polish legal culture[7] with examples easily traceable in Romanian law. Chernyshova’s sociological enquiry into Soviet consumer culture showed that, despite certain constraints on consumption, ‘the Brezhnev period did see a limited version of capitalist consumer modernity’.[8] Heldmann documents a similar trend in the German Democratic Republic[9] and Valuch in Hungary.[10] Given the historical thesis that Romania strictly followed the USSR’s directives and example,[11] is unlikely that a similar consumer culture was absent. Other comprehensive works called for a reassessment of the ‘Anglo-centric story’,[12] pointing out that ‘fascist and communist societies consumed too’. In other words, not all consumers are ‘liberal capitalists.’[13] Romania’s example also proves this assertion.

The existence of consumer and residential credit in communist Romania does not entail the absence of differences between liberal-capitalist and communist countries. Most Romanian consumer and residential credit laws adopted during communism do not refer specifically to ‘consumers’ as a recognised category of natural persons engaging in transactions for consumption (as they are currently defined by EU or national legislation).[14] Instead, they rely on alternative terminology (‘workers = muncitori’, ‘retirees = pensionari’, ‘peasants = ţărani’), although it should be emphasised that these labelling differences are ideological and formal in nature, not of substance. In addition, communist countries experienced less choice, lower quality, and more shortages than their capitalist counterparts.[15]

However, these differences are irrelevant when analysed through the lens of functionality. While no recognisable and widely accepted functional method exists, legal comparatists agree on several elements. First, functionalist comparative law is factual, focusing not on the rules but their effects. Thus, it often responds to real-life situations (e.g., housing crisis, improvement of living standards), and legal systems are compared on their judicial responses to similar problems. From this perspective, one can easily trace several similarities deriving from the continuation of monarchical goals during the communist era: industrialisation driving urbanisation and increasing living standards. From this perspective, the communist period in Romania was ‘the longest unbroken period of increase in the living standard in the entire 1918–2018 century,’[16] and credit for consumers played a significant role.

Second, comparative law combines its factual approach with the idea that its legal objects under investigation must be understood in the light of their functional relation to society. Law and society are deemed separable, albeit related. Despite a common myth, the communist system accepted and even encouraged individual or personal property[17] for two main reasons: (a) to achieve its ideological and political goals (increasing the population’s standard of living, ensuring basic needs for all citizens) and (b) to create or maintain strong popular support. The functional analysis of credit legislation implemented during the communist period brings additional evidence.

Third, the function itself is used as a comparative element: institutions (legal or non-legal) are comparable if they fulfil similar functions in different legal systems.[18] In this regard, two aspects stand out: (a) the fundamental role of the state in the development of residential credit during the monarchic and communist periods, mainly via state guarantees, tax incentives and fixed, low (legal) interest rates; and (b) the fundamental role of instalment sale mechanisms during the monarchic and communist regimes in developing credit for consumer durables, due to the low purchase power of the population.

Thus, focusing on the economic reality of the transaction rather than the terminology used by the legislators, it becomes clear that various forms of credit existed and were widely employed during communism in Romania for residential purposes or the acquisition of durable goods. This functional reality suggests that ideology played a minor role in developing consumption and access to credit. Therefore, a legal analysis cannot discard periods when the political and economic system was allegedly incompatible with capitalism.

This study argues that the legacy of communist consumer and residential credit laws in Romania proved more enduring and influential than previous works have suggested. Using legal history and doctrinal analysis in a functional approach, coupled with statistical and empirical data, it demonstrates a normative continuity between pre-and post-1989 Romanian consumer and residential credit laws that endured until the adoption of the EU-driven framework in the late 1990s. It further ventures that this normative continuity indicates the existence of solid foundations and functional similarities between the two legal systems, undermining the idea that ideology alone could explain the creation of consumer and residential credit laws or that communism was inimical to consumers and consumer and residential credit.

The rest of the article is organised as follows. The second section deals with consumer and residential credit’s historical and ideological origins. It advances a set of core consumer and residential credit characteristics extracted from the current liberal-capitalist legal tradition of the European Union (EU) to assess the normative continuity and functional equivalence of consumer and residential credit laws during the monarchy and communism. Section three introduces the three stages of Romanian history and pursues the emergence and development of consumer and residential credit in Romanian law between 1859 and 2007. Section four discusses the secured credit granted to consumers for building or purchasing a residential property. In contrast, section five examines secured and unsecured credit given to consumers to acquire durable goods. Both sections reveal that communist legislation played an essential role in developing consumer and residential credit legislation in Romania, justifying the idea of legal continuity in this area. Lastly, concluding remarks emphasise that since the enduring impact of communist legislation on the advance and modernisation of consumer and residential credit law during the transition period is undeniable, the relevance of economic and political ideology regarding consumer and residential credit should be revisited.

2 The Fundamentals of Consumer and Residential Credit

Credit is generally understood as ‘loans and other deferred payment methods made available to consumers and companies to enable them to purchase goods and services, raw materials and components.’[19] The Latin root, credere, can be translated as ‘trust’. Without trust, there would be no credit, which explains why, in many instances, the creditor’s confidence must be enhanced by some form of guarantee (collateral).[20] Credit depends on legal and value systems that recognise the sanctity of contracts between parties.[21] Modern legal systems have added simplified and swift enforcement procedures to strengthen credit agreements’ legal and binding nature.[22]

In this context, consumer credit is a ‘short and medium-term credit extended to individuals through regular business channels, usually to finance the purchase of consumer goods and services or to refinance debts incurred for such purposes.’[23] This study adopts a broader understanding of the term. It addresses two primary forms of credit for consumers: (a) residential credit, meaning a secured loan granted to individuals to construct or purchase a dwelling, and (b) secured or unsecured commercial lending to individuals to acquire consumer goods.[24]

2.1 Historical Origins of Consumer Credit

Graeber traced the origin of credit and debt at least 5000 years back.[25] Most authors agree that the modern foundations of credit were laid in the Western world and developed alongside the nation-state, for instance, in the Netherlands, the UK, Germany, France and the US. However, it was generally a privilege for the wealthy and powerful.[26] The democratisation of credit (i.e., granting credit to lower strata of society) began only in the first decades of the 20th century[27] and rapidly expanded after WWII.[28]

The above historical overview should not be construed in the sense that poorer categories were deprived entirely of credit until recent years. Alternative banking has been documented to have existed alongside private commercial and merchant banking early in European history.[29] Charitable organisations such as ‘Monte de Pietà’ (Mount of Piety), which functioned as pawn-credit foundations, extended credit to the poor against security in personal goods,[30] including in Romania.[31] Credit cooperatives and saving houses were founded across German and French-speaking areas pooling member resources and facilitating access to cheap credit.[32] They played an essential role in promoting financial inclusion and increasing the standard of living of the low-income classes.[33] They were the source of inspiration for the first institutions designed to grant affordable residential credit in Romania,[34] which, however, did not save them from nationalisation under the communist regime.[35]

In the US, a substantial transformation of consumer credit occurred at the end of the second decade of the 20th century, when state governments pressured commercial banks to extend credit to the masses to curb predatory lending by loan sharks.[36] The democratisation of consumer and residential credit drove the consumers’ desire to improve their living standards[37] by committing their future incomes in exchange for immediate access to durable goods or housing.[38] Similarly, increasing the citizens’ living standards was the primary motivation for the communist system to provide consumers with credit for residential properties and other durable goods.[39]

2.2 Ideological Origins of Consumer and Residential Credit

An apparent ideological element is attached to consumer and residential credit and its effects. In the words of one historian, ‘today, the culture of consumption is largely responsible for legitimising capitalism in the eyes of the world.’[40] Another argued that ‘consumerism’ – and, implicitly, the tools that made it possible, consumer and residential credit – is one of the fundamental traits that made Western civilisation the dominating force in world history.[41]

Nevertheless, differences exist even within the capitalist system between private and alternative banking models. A broad and heterogenous set of financial institutions (i.e., credit cooperatives, savings banks, credit unions or mutual savings associations) has been less animated by considerations such as profit maximisation for shareholder benefits and risk-taking that generally characterise private commercial banking. On the contrary, their mission was focused on fostering economic and social development and facilitating savings or credit for poorer households via prudent banking and sustainable returns.[42] Despite their goals and alternative approaches, these institutions were created and active in the credit market.

On their end, communist systems, like the Romanian one, generally viewed credit as a manifestation of the capitalist order, representing an instrument for despoiling the poor and enriching the rich. Communist credit was motivated not by profit but by the fair and equal redistribution of resources[43] and the desire to instil loyalty to the Party and cohesion in the mass of citizens.[44] Thus, the position of the socialist economy appears to have embraced some of the alternative banking’s views in its rejection of profit-generating interest rates (which were perceived as neo-usurious) and sustainable, rational use of existing financial resources.[45]

Romanian communist legal scholars listed four types of credit: (a) banking credit (by which the state extended credit to economic units and the population); (b) public credit (by which the state used the population’s savings to lend to economic units); (c) cooperative credit (used in the cooperative system) and, of relevance to this study, (d) consumption credit (by which the state, through the banking apparatus and commercial units, fosters sale of durable goods to the population through credit repayable in instalments).[46]

In opposition to capitalist systems, where private commercial banks appear as intermediaries between the Central Bank and the credit beneficiaries, the socialist systems adopted a so-called ‘direct crediting’ policy, by which commercial units and the population could access credit directly from the operational branches of the National (Central) Bank (Table 1 ).[47]

Ideological approach concerning consumer and residential credit.

| Capitalism | Communism | |

|---|---|---|

| Role of credit | An instrument for advancing income for the immediate purchase of goods (commercial) | An instrument for implementing the financial and economic policy of the party (non-commercial) |

| Motivation of credit | Profit maximisation | Fair and equal distribution of resources |

| Source of credit | Private investors | The state |

| Grantor of credit | Private banking Alternative banking Retailers |

State-owned banks State companies (retailers) |

| Cost of credit (interest) | Cost of credit determined by market forces | Cost of credit determined by law |

Nevertheless, ideological considerations fade when one considers access to residential credit. Historians have linked the development of credit markets and products to growing urbanisation and industrialisation,[48] a trend easily discernible in communist systems. This study shows that as Romania continued industrialisation and urbanisation efforts under the communist regime, the role of residential credit granted to the population grew similarly, peaking at the end of the 1970s. Moreover, residential credit’s constitutive elements and mechanics are the same regardless of the political or economic regime. Ultimately, the evidence will show that the Western and communist types of residential credit are functionally equivalent from a legal perspective and answer the same social needs.

The main differences are the source of credit and the formation of interest. Regarding the source, credit comes mostly from retailers or banking and non-banking financial institutions in capitalist systems. In contrast, in communist systems, credit comes from the state via specialised financial institutions (such as the House for Savings and Consignments in Romania) or non-financial institutions (such as retailers – state-owned enterprises). Regarding interest, while in capitalist systems, it is governed by free-market forces and suffers the vagaries of the market, in communist systems, it is fixed by law and less affected by market changes.

Even so, capitalist systems were not always free from state credit. In the 1930s, the US government subsidised credit in the collapsed residential construction industry. Consequently, ‘state-subsidised credit (…) became an enduring entitlement of US citizenship.’[49] After WWII, the US Housing Act of 1949 expanded government credit subsidy programmes and established the amortised 30-year home mortgage as the industry standard,[50] free from purely market-based influences.

The situation was similar in modern Romania. Before and after WWI, the state offered credit to specific categories of consumers to foster access to owned housing. State credit was needed to induce private investment to build and meet the critical demand for housing, which communist governments, including Romania’s, have also confronted and attempted to solve. Thus, state-backed credit for addressing the social need for housing was hardly a communist invention or attribute and cannot count as an argument against the functional equivalence of communist and capitalist consumer and residential credit. On the contrary, it strengthens it.

How interest rates are determined in the two systems could also challenge the idea of functional equivalence from an ideological and economic perspective since communist systems considered interest a means of ‘supplementary exploitation’ of the population.[51] However, one should remember that capitalist systems initially urged private banks to get involved in crediting the population mainly to combat exorbitant and eventually predatory interest rates.[52] At the same time, alternative banking models provided customers cheap credit. In addition, communist systems did not entirely stop from charging interest. In communist Romania, interest rates were maintained: a) to cover the administrative costs of banks, b) to curb excessive use of credit, c) to stimulate specific sectors of the economy via differentiated interest rates and d) to punish those who did not repay on time.[53] However, interest rate levels were significantly decreased by law to deprive them of their exploitative potential. Therefore, by decoupling interest rates from free market mechanisms, the credit products offered by the state or its economic operators tended to be more advantageous to the population.

Societies whose members have recourse to credit need growth and, more importantly, employment prospects. Thus, a deteriorating economic situation negatively affects repayments.[54] This was evident during the financial crisis of 2007–8 and the COVID-19 pandemic. From this standpoint, consumer debtors in communist economies appear to have been in a better position because unemployment was virtually non-existent (and even criminalised), and the risk of non-payment was minimal. Moreover, in case of default, they had multiple occasions to repay their dues before their property was foreclosed.

2.3 Elements of Consumer and Residential Credit

A reference point is needed to assess the functional equivalence of consumer and residential credit in Romania’s capitalist and communist systems. To that end, I propose juxtaposing and comparing the following building blocks of consumer and residential credit 1) the subject of credit (consumers), 2) responsible lending (assessment of creditworthiness, down payments and risk-mitigating mechanisms), 3) the cost of credit (interest, charges and penalties), 4) the duration of the agreement and 5) the availability of swift enforcement mechanisms for honouring debt payments and obligations. These fundamental elements will be used in sections 4 and 5 to test the functional equivalence of Romania’s communist consumer and residential credit legislation with monarchic or transition counterparts.

Paradoxically, the same building blocks can be identified in the 2008 Consumer Credit Directive (CCD)[55] and the 2014 Consumer Mortgage Directive (CMD),[56] which would have suggested a normative continuity after EU accession. However, adopting the EU-driven acquis has discontinued the normative continuity of the monarchic and communist consumer and residential credit laws by promoting asset-based credit and market-based interest rates and limiting consumer protection measures to mandatory disclosures and financial prudential rules.

3 Continuity in Transformation: Consumer and Residential Credit in Romania

This section reflects that Romania has undergone a continuous legislative and institutional transformation. This process is even more pronounced in the case of consumer finance.

3.1 Three Stages of Romanian History

Three main stages can be identified in Romanian history. The first covers the modern period, from the 1859 Union until the abolition of the monarchy in 1947. It constituted the country’s foundational period when its institutional and legal framework was created. The second is the communist period, lasting from 1947 until the 1989 Revolution, nowadays commonly regarded as an unwanted intermezzo in the country’s development. The third is the contemporary period, which extends from the fall of communism in 1989 to the present and is generally portrayed as a return to the democratic and capitalist system built during the foundational years. During this period, Romania joined the EU in 2007.

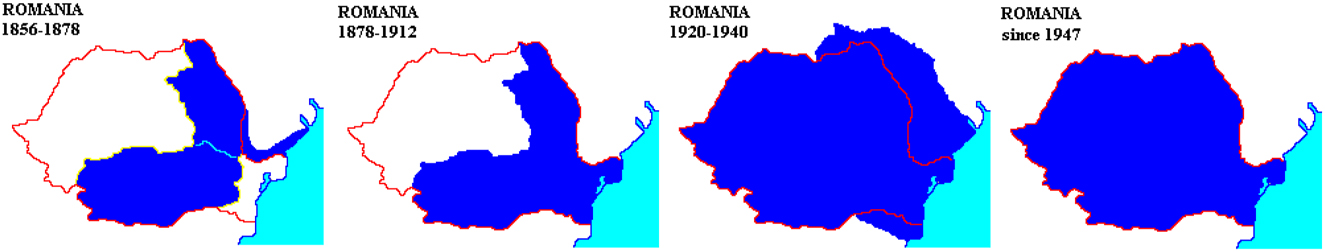

Each stage was marked by efforts to develop, industrialise, and modernise the country and its institutions, even though most contemporary historians and legal scholars deny any merits to the communist period. The continuous transformation is more evident if analysed chronologically, based on these three stages (Figure 1).

The territorial evolution of Romania from 1856 to the present day. Source: World History at KMLA (https://www.zum.de/whkmla/region/balkans/xromania.html). The figure illustrates the fast pace of Romania’s unification, which also meant territorial and population changes that posed significant challenges to Romanian policymakers and legislators.

3.2 The Emergence of the Consumer and Consumer and Residential Credit in Romanian Law

The common wisdom that Romanian consumption and consumer and residential credit are creations of the transition from communism to capitalism is misleading and incorrect. Before and, especially during communism, efforts were made to increase access to consumer goods, curb unfair trading practices and ensure fair and equitable access to credit. The emergence and expansion of consumer finance accompanied the establishment and development of the Romanian financial system during the foundational years and the improvement of citizens’ living standards during communism via access to housing and durable goods.

3.2.1 Modern Romania

During the modern period (1859–1947), the local economy had a preponderant agricultural character. Thus, most imports concern products for consumption,[57] which indicates the emergence of a preoccupation with and an inclination toward buying consumer goods, in line with the international trend. Empirical data also reveals a steady increase in consumer goods imports as the country’s financial situation and the population stabilised and improved (Table 2).

The increase of imports of specific consumer items during 1879–1903. Source: Romania’s Statistical Yearbook 1904, p. 315, Table 10.

| Years | Rice | Raw coffee | Cacao | Citric, exotic fruits, nuts, etc. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kilograms | ||||

| 1879 | 3.613.076 | 804.857 | 1.282 | 2.211.916 |

| 1884 | 5.156.222 | 1.272.015 | 2.419 | 2.606.802 |

| 1889 | 6.039.195 | 1.188.576 | 7.417 | 3.070.248 |

| 1894 | 6.636.637 | 1.378.894 | 23.279 | 4.913.179 |

| 1899 | 7.369.690 | 1.826.806 | 52.574 | 5.695.392 |

| 1903 | 9.396.457 | 2.206.416 | 60.727 | 7.094.352 |

As of 1878, the House of Deposits and Consignments, a public financial institution, would also start issuing loans to “particulars”. During 1878 and 1902, these loans totalled Lei 50,007,758, of which only Lei 1,479,350 were still outstanding in 1902.[58] However, it would not be the sole provider of credit. By 1898, 18 banks were active on the Romanian market; in 1914, there were 215. A rapid expansion could be witnessed in the number of popular (cooperative) banks. In 1914 there were 2935 such institutions.[59]

The rate of consumer goods imports decreased during the interwar years due to a combination of protective tariffs, import substitution with local products[60] and a decrease in the population’s purchasing power due to the economic crisis in the 1930s (Table 3).

Romania: commodity composition of exports and imports 1922–1938 (Per cent). Source: Kaser, M.C. and Radice, E.A (eds), The Economic History of Eastern Europe 1919–1975, Volume I, Clarendon Press (Oxford), 1985, 461, Table 7.36, 7.56 and 7.57.

| Average 1922–1924 |

Average 1928–1929 |

1932 | 1935 | Average 1937–1938 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Export | Import | Export | Import | Export | Import | Export | Import | Export | Import | |

| Agricultural produce | 62.1 | 11.2 | 49.6 | 9.2 | 46.7 | 9.0 | 36.0 | 8.5 | 43.9 | 6.2 |

| Raw materials | 35.4 | 2.3 | 49.6 | 4.4 | 50.7 | 4.7 | 61.8 | 4.3 | 52.0 | 7.7 |

| Primary products | 97.5 | 13.5 | 96.2 | 13.6 | 97.4 | 13.7 | 97.8 | 12.8 | 95.9 | 13.9 |

| Consumer goods (other than agricultural) | 1.1 | 51.1 | 2.5 | 42.0 | 1.4 | 46.3 | 1.6 | 36.5 | 3.3 | 25.0 |

| Machinery and vehicles | 0.2 | 9.5 | 0.1 | 18.4 | 0.3 | 10.6 | – | 17.9 | – | 25.0 |

| Manufactures | 2.5 | 86.5 | 3.8 | 86.4 | 2.6 | 86.3 | 2.2 | 87.2 | 4.2. | 86.1 |

According to empirical data, consumer credit emerged early in the form of instalment sales of durables and other consumer goods. In 1887, Singer sewing machines were sold in instalments in several Romanian cities[61] under the influence of economic models imported from the United States. These were later joined by bicycles and musical instruments (1897),[62] gramophones, furniture, and carrycots (1909), commercialised via specialised shops.[63] According to the advertisements, all these consumer goods were destined for “industrialists and families of high quality (Figure 2).”[64]

Advertisement for instalment sales retail shop destined for “Families of Superior Quality”. Source: Opinia, Year VI, no 831/1909, p. 4. The figure illustrates that instalment purchases were not available for everyone, but for the well-off segments of the population.

Even after WWI, although the territory and population of Romania tripled in size, its economy remained mainly agrarian (employing approximately 80% of the active population).[65] It depended on exports of commodities such as cereals and oil[66] and imports of consumer goods, machinery, and other finite products.[67] The market was only a secondary distribution mechanism. Income inequality was high, with 96% of people struggling to survive from one day to the next.[68] ‘Credit’ was primarily employed to make ends meet. For instance, in 1931, debts up to Lei 6000 represented 32.9% of the total debts owed to credit cooperatives and 73% of their total number of debtors at a time when the maximum hourly wage for a skilled worker was around Lei 28 and the daily wage for a male working in agriculture ranged between Lei 60 and 90.[69] At the same time, debts between Lei 6001 and 10,000 represented 19.2% of the total debt owed to credit cooperatives and 14.5% of the total debtors.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, debts between Lei 20,001 and 50,000 and debts over Lei 50,000 amounted to 15.7%, respectively 11.8% of the total debts owed to credit cooperatives, but only 3.3%, respectively 0.7% of their total number of debtors.[70] Newspapers abounded in advertisements of credit sales for consumer goods (e.g. vacuum cleaners, radio sets), although these were most likely addressed to the top 3–4% of the population.

Urbanisation levels were low before WWI, and efforts were made to facilitate access to credit for constructing new dwellings, with various success rates. For instance, the Urban Credit House (UCH) of Iasi issued 2379 loans during 1881–1903, totalling over Lei 40 million, out of which more than a quarter (Lei 12.7 million) were repaid by 1903.[71]

Housing availability and quality remained problematic between the two world wars. For instance, 16,400 housing units were built in the capital city of Bucharest during 1918–1938 for 631,000 inhabitants and 158,000 households at the 1930 census. During 1935–1938 only 38,892 constructions were authorised in the entire country.[72] Voluntary sales of immovables remained somewhat constant, with variations during the economic crisis of the 1930s. However, there is no exact indication of how many were sold and purchased on credit.[73] Thus, it is unsurprising that the legislature focused on solving the housing crisis, with consumer residential credit laws emerging in 1921.

Consumption suffered during WWII because production was redirected to support the war effort. The quantity and quality of the food supply and other essential goods (i.e., clothing or footwear) became critical.[74] Nevertheless, most foodstuffs and goods were freely traded on the market, encouraging speculation.[75] Housing was a significant issue, worsened by the Allied bombardments.

For these reasons, in 1945,[76] the Parliament adopted one of the first laws considering the interests of consumers as a specific category.[77] The law did not define consumers but implied that they were natural persons entering commercial agreements for consumption. Professional merchants were obliged to inform consumers of their prices for goods and services and publicly disclose their contact and registration details,[78] in what appear to be proto-consumer protection rules through mandatory disclosures and transparency.

Additionally, merchants could be liable for fraud if they used smaller measurements or sold underweight, counterfeit, or sub-quality products.[79] Selling consumer goods at prices either higher than the maximal ones or lower than the minimal ones set by law was also punishable.[80] In these cases, the consumer could be held liable alongside the merchant unless they reported the latter’s unlawful behaviour to the authorities.[81]

3.2.2 Communist Romania

Following WWII, Romania underwent severe structural changes in all areas as its economy and society were reorganised according to the communist model developed by the USSR. Nevertheless, it experienced its version of the ‘glorious thirty years’[82] – with economic recovery in the 1950s and an economic boom in the 1960s and 1970s – followed by a self-induced crisis in the 1980s that ultimately led to the regime’s collapse.[83]

These economic realities would be reflected in consumer and residential credit legislation. However, it should be mentioned from the outset that during the entire period, the banking system and access to credit – including for households – were placed under control and used as both an instrument for fair and equitable redistribution of resources and for achieving the party’s financial and economic policy.[84] The Romanian National Bank – the central bank – was nationalised (1946),[85] while all other banking and credit institutions were dissolved and liquidated (1948),[86] with some notable exceptions, such as the House of Savings and Cheques and the House of Deposits and Consignments. These were merged into one institution, the House of Savings and Consignments (1948),[87] whose mission was to attract the population’s savings and perform the crediting operations for the population, as provided by law.[88]

Empirical data for the first communist decade is scarce because official statistical reports were suspended during the war and only resumed in 1957.[89] Prior works addressing living standards in Romania have pointed out that the post-war and recovery periods were still affected by chronic shortages of consumer goods, including food, even if available income steadily increased.[90] Living standards only surpassed pre-war levels in the 1960s.

After the abolition of the monarchy in 1947, consumer protection against unfair trading practices became a criminal matter. Law 351/1945 was replaced by Decree 183/1949 on the punishment of economic crimes,[91] followed by Decree 202/1953 amending the Criminal Code.[92] The terms merchants (comerciant) and consumers (consumator) disappeared,[93] replaced by criminal or civil law-specific terminology (i.e., victim [victimă] or buyer [cumpărător]). Nevertheless, the decrees maintained consumer protective measures against unfair trading practices.[94] As criminal offences, these actions were investigated by prosecutors, police officers or special delegates of the relevant ministries and punished with imprisonment, fines and confiscations.[95]

While the criminalisation of unfair trading practices was also part of a repressive effort directed at those categories of citizens that rejected the communist regime, not all merchants were freedom fighters. Some were punished for their anti-consumer behaviour. Therefore, the rules protective character for consumers cannot be disregarded, as evidenced by their survival after the fall of communism. Moreover, the state bodies’ investigative and enforcement roles are still reflected in the architecture of the consumer protection apparatus developed after 1989, being subordinated to the government.

The sporadic resurfacing of the term consumer throughout Ceausescu’s regime (1965–1989) is also relevant. Decree 446/1972 on the organisation and management of the Ministry for Internal Commerce[96] states that one of its attributes is to ‘orient and influence the taste and preference of consumers towards local products (emphasis added).’[97] The increase in local production, economic efficiency and national income improved the population’s living standards,[98] access to consumer goods and means of redress. More growth in the total net income of the population was foreseen, coupled with an expansion and diversification of consumer goods and the construction of more housing with state credit.[99]

The 1972 law on finances[100] constituted a solid legal basis for crediting consumers. It allowed the House of Savings and Consignments to offer credit to the population for constructing or buying housing properties and other goods, as provided by the law.[101] According to the Civil Code, beneficiaries could also guarantee credits through possessory securities in personal property (pawning).[102] Thus, credit improved the population’s living standards by unlocking future income and enabling faster access to durables. Empirical data confirms that the increased demand for consumer goods fuelled local production and the national economy (Table 4).[103]

Interior commerce in communist Romania. The table illustrates the continuous growth in both consumption and production in Romania during the communist years. Source: Statistical Yearbook of Romania 1990, as compiled by Bogdan Murgescu in Romania si Europa: Acumularea decalajelor economice, (Polirom, 2010), p. 353.

| 1948 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1989 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total commercial units (thousand units) | 108.4 | 65.8 | 50.8 | 61.6 | 78.7 | 82.0 | |

| Out of which | Private | 97.9 | 38.2 | 0.6 | |||

| State owned | 2.0 | 7.8 | 23.5 | 30.7 | 40.6 | 41.9 | |

| Cooperatives | 8.5 | 19.8 | 26.7 | 30.9 | 38.1 | 40.1 | |

| The total volume of sales (billion lei) | 9.9 | 13.6 | 39.8 | 93.7 | 213.0 | 297.3 | |

| Bread (thousand tons) | … | 667.5 | 1.2150 | 1.9617 | 2.4495 | 2.5719 | |

| Pasta (thousand tonnes) | … | 18.7 | 28.7 | 48.3 | 61.6 | 85.9 | |

| Meat (thousand tonnes) | … | 75.9 | 138.5 | 185.6 | 462.7 | 224.4 | |

| Meat products (thousand tonnes) | … | 9.9 | 45.8 | 94.1 | 236.7 | 257.1 | |

| Fish (thousand tonnes) | … | 6.9 | 10.8 | 52.7 | 72.3 | 75.3 | |

| Canned fish (thousand tonnes) | … | 18.5 | 26.3 | 37.6 | 44.3 | ||

| Edible oil (thousand tonnes) | … | 23.9 | 69.6 | 134.8 | 203.9 | 199.2 | |

| Milk (thousand hl) | … | 354.0 | 1.1900 | 3.7269 | 5.9579 | 5.5872 | |

| Cheese (thousand tonnes) | … | 8.5 | 28.1 | 59.0 | 95.2 | 57.7 | |

| Butter (thousand tonnes) | … | 2.0 | 8.9 | 14.7 | 28.7 | 23.5 | |

| Eggs (million pieces) | … | 27.0 | 159.6 | 610.4 | 1.5660 | 2.0664 | |

| Sugar (thousand tonnes) | … | 84.3 | 148.4 | 233.3 | 419.4 | 345.2 | |

| Sugar products (thousand tonnes) | … | 14.4 | 42.9 | 71.6 | 144.7 | 480.6 | |

| Fresh vegetables (thousand tonnes) | … | 105.2 | 241.7 | 649.3 | 813.8 | 860.5 | |

| Canned vegetables (thousand tonnes) | … | 16.7 | 79.8 | 163.0 | 237.8 | ||

| Fresh fruit (thousand tonnes) | … | 78.6 | 97.3 | 107.0 | 225.9 | 302.1 | |

| Beer (thousand hl) | … | 880.0 | 1.6160 | 4.2474 | 9.7340 | 11.7783 | |

| Textiles and clothing made of cotton (million m2) | … | 120.7 | 184.8 | 232.3 | 284.4 | 287.3 | |

| Woollen fabrics and garments (million m2) | … | 18.1 | 28.2 | 40.3 | 72.4 | 59.7 | |

| Woven fabrics and garments of silk (million m2) | … | 12.0 | 22.7 | 32.0 | 60.1 | 80.7 | |

| Knitwear (million lei) | … | 434 | 1.444 | 4.017 | 10.533 | 14.780 | |

| Footwear (million pairs) | … | 8.6 | 26.8 | 51.2 | 76.9 | 84.3 | |

| Furniture (million lei) | … | 58 | 998 | 3.243 | 7.960 | 6.539 | |

| Vacuum cleaners (million pieces) | … | 6.0 | 64.6 | 132.5 | 159.2 | ||

| Watches (thousand pieces) | … | 390.0 | 910.5 | 1.8561 | 1.7428 | ||

| Medicines (million lei) | … | 206 | 613 | 1.058 | 0.2252 | 4.428 | |

| Soap (thousand tonnes) | … | 12.2 | 29.0 | 25.6 | 23.7 | 20.6 | |

| Detergents (million lei) | … | 30.0 | 295.6 | 827.2 | 1.3963 | ||

Unfortunately, these developments were halted during the 1980s when Romanians had to endure some of the harshest economic conditions in the communist bloc due to Ceausescu’s decision to repay the country’s external debt. The result was penury in consumer goods and a drastic reduction in the quality of living, which culminated with the 1989 Revolution.

3.2.3 Contemporary Romania

After the fall of communism in 1989, sector-specific consumer law emerged relatively fast with the adoption of the Government Ordinance (GO) 21/1992 on consumer protection.[104] A Consumer Code was adopted in 2004.[105]

In 1993, Romania embarked on the path of legislative harmonisation with the EU, a precondition to the country’s entry into the Union.[106] The negotiation chapter concerning consumer protection was provisionally concluded in 2001, and the government signed the Treaty for joining the EU on 25 April 2005, undertaking to continue legislative harmonisation efforts.[107]

The most relevant pieces of legislation impacting consumer and residential credit include Law 58/1998 on banking,[108] Law 193/2000 on abusive terms in consumer contracts,[109] GO 85/2004 on consumer protection in concluding and performing contracts at a distance for financial services,[110] Law 289/2004 on the legal regime of credit contracts destined for consumers, natural persons[111] and its Application Norms.[112]

Several additions to the consumer and residential credit regime occurred after Romania acceded to the EU: Government Emergency Ordinance (GEO) 50/2010 on consumer credit,[113] the New Civil Code in 2011, GEO 52/2016 on credit agreements offered to consumers for immovable property[114] and the debt relief mechanisms attempted by Law 77/2016 on giving in payment of immovable property for the discharge of obligations under credit agreements.[115]

With these, the transition from communist to EU consumer and residential credit was complete. However, the EU legislation falls outside the scope of this study. The following sections referring to contemporary period focus instead on the normative acts adopted between 1990 and 1999 before Romania implemented the EU acquis concerning credit for residential property and durable goods. The subsequent analysis will reveal that although the new legislation was meant to replace the communist one, the building blocks remained the same.

4 Secured Credit for Residential Property

4.1 The Modern Period (1859–1947)

The issue of housing as purpose-built property has been a concern in the modern period, even before WWI. The state’s intervention and financial support played a tremendous role in slowly improving the housing situation, at least in urban areas.[116] If in Western Europe, the intervention could be explained by the governmental belief that housing improvement would be a pre-condition for raising the workforce’s physical, educational and cultural level, in Eastern Europe urban dwelling construction was part of the efforts towards industrialisation and economic development.[117] Romania was no exception from this trend.

In its old form, mortgage credit was extremely disadvantageous due to the high-interest level and short repayment period. Moreover, the local population lacked financial literacy, which made it easy prey to unscrupulous lenders. A new Law concerning mortgage credit[118] was implemented in 1873[119] to address these flaws. The law recognised the local economic situation, characterised by a lack of capital and poverty. The authorities employed the experience of other countries, such as Germany, to solve this situation.[120]

To tackle the usurious loans of the time and encourage building construction in the capital and emerging cities,[121] in 1874, the first UCH was set up in Bucharest. However, more were to appear during 1875–1881. These institutions did not lend money but issued bonds called ‘letters of credit’ (scrisori de credit). The bonds yielded an interest of 5% (in 1875–1881, the interest was 7%). They were backed by all the real estate mortgaged by the UCH. Although the initiative was advantageous for its customers, due to the low saving power of the population, it was too expensive to be appealing. The value of the loan could only amount to 50% of the total value of the dwelling, while the 5% interest rate meant that in 20 years, the initial value of the loan would double. Thus, this system was partially successful, with only 200 dwellings built in Bucharest in 1911–1930.[122]

In 1910, Romania adopted the first European law “regulating the construction of cheap and healthy housing.”[123] The Explanatory Memorandum acknowledged that “private initiative cannot generate the number of housings needed, due to the current state of the economy”, which required the state’s intervention and support.[124] These came as a series of facilities for builders and new owners, including exemptions from all taxes relating to housing for individuals and companies. The builder paid the city only half of the building work’s value planned for opening new streets, and the material for housing construction was exempt from taxes.[125] The law also imposed limits on profits for construction companies, capped at 6% of the dwelling’s price.

Among the first applications of the law was the subsequent creation by Bucharest City Hall of the Bucharest Communal Company for Cheap Housing Construction.[126] The law empowered the company to build cheap housing of a maximum value of Lei 8000 to sell to the inhabitants of Bucharest, who could pay a 10% down payment of the dwelling’s value. Preference was to be given to workers, public and private employees who were in good health, under the age of 50, and whose salary was below or equal to Lei 250. Since the company could not invest its capital during the first 20 years, it was empowered to issue bonds (obligaţiuni) with 5% interest, which were sold on the market.[127] The company was active until 1945.[128]

In the early 1920s, the challenge of housing aggravated. Besides the destruction caused by WWI, no new housing was constructed during 1916–1920. Moreover, cities became increasingly overcrowded due to the migration of the peasantry, attracted by the prospects of a better living standard and the emergence of new working places due to industrialisation.[129]

Thus, measures to encourage housing construction were adopted in 1921.[130] Cooperative societies were set up to buy and divide the land to construct low-cost housing for members: workers, civil servants, and pensioners, and build on this land. Thus, the envisioned solution for the housing issue began to involve urban owners’ direct, mutual, and solidary association. To this end, in 1926, another law on Urban Credit Houses was passed, authorising the establishment of companies with unlimited duration through direct association and mutual guarantee of urban owners, who could borrow against the mortgage on their properties.[131]

The 1921 initiative was renewed via Law 80/1927 on the encouragement of housing building[132] and later provided a series of facilities to specific categories of individuals, such as temporary tax exemptions[133] and access to cheap credit from the state.[134] The 1927 law was in force until 1973 when it was repealed as no longer compatible with the socialist legal framework.[135] Nevertheless, its survival long into the communist period is a compelling argument supporting the idea of continuity in the consumer-credit legislation and functional equivalence, ideology notwithstanding. It also indicates that consumer housing remained a concern for the new regime.

In 1930, a series of institutions with real consequences on credit and the economic orientation of the state appeared, among which the Transitory Mortgage Credit Institute,[136] the Autonomous House of Building Constructions and the Rural House, which were to make it possible for small farmers with no property, like the rest of the population, to obtain advantageous loans for the rational development of their households, transforming their debts guaranteed by short-term mortgages and exaggerated interest rates (12%) into long-term debts with low-interest rates.[137]

4.2 The Communist Period (1947–1989)

The state’s financial contribution and involvement in housing construction remained significant. Since WWII devastated a substantial part of the residential buildings in major cities (Ploiesti or Bucharest),[138] and Eastern countries rejected Western foreign aid, the reconstruction had to rely exclusively on domestic resources. These were affected by the war and the subsequent reparations – USD 1.2 billion – the country had to pay to the USSR for its role in the war. Moreover, Romania was occupied by Soviet troops for a decade (until 1956) and was thoroughly pillaged through the so-called SovRoms, joint-venture companies that had no other purpose but to extract Romanian resources for the benefit of the USSR.[139] Therefore, the housing situation improved modestly in the first years after the war, with most residences being built in rural areas from the population’s funds.[140] The explanation for this phenomenon is the population’s purchasing power fluctuation. Those in the rural areas who managed to save up before the war invested their savings in housing construction in the first decade after.

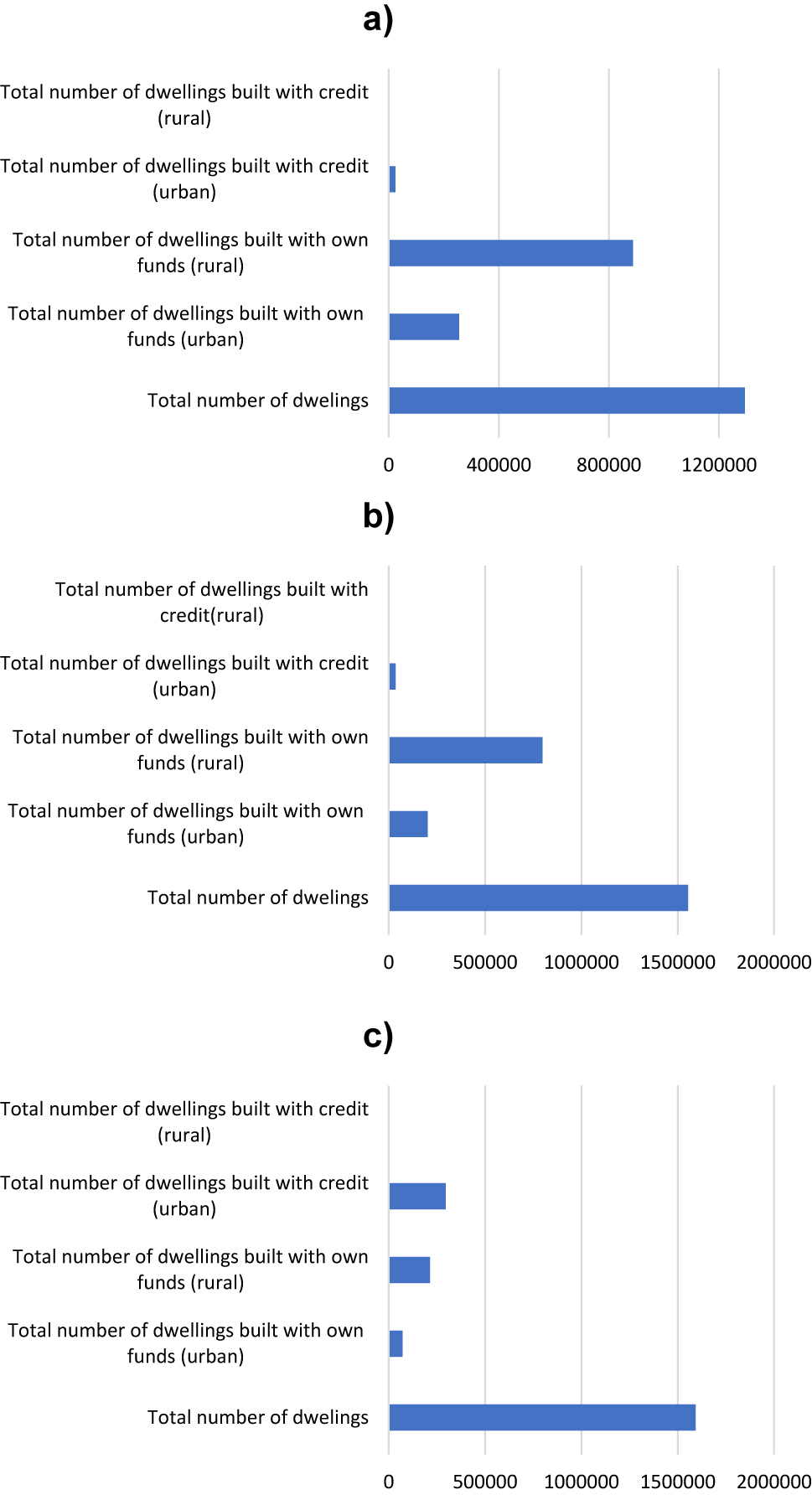

However, the ratio between dwellings constructed from own funds and those constructed from state funds or with state support (residential credit) will reverse in the next two decades. As a result of the massive internal migration caused by resumed efforts for industrialisation (and the implicit development of a numerous and skilled working class),[141] the communist state began an extensive program of apartment block building, which it supported both technically and financially. The primary purpose was to provide sufficient housing for those who needed it and to distribute it justly to the population. Therefore, the allocation and the sale of apartments did not observe market criteria but the premise that everyone has the right to one house (Figure 3).[142]

a)–c). Dwellings brought into use during 1950–1960, 1961–1970, 1971–1980. Source: Romania’s Statistical Yearbook 1990 and 1998. The figures illustrate a steady increase in residential credit granted to the urban citizenry for the purpose of building or purchasing a dwelling, coupled with a steep decline in housing construction from own funds in the countryside, while residential credit for similar purposes in the countryside is virtually non-existent.

The first normative measures by which the state credited the construction of new housing were Decision 4015/1953, corroborated by Decision 980/1954 and Decision 58/1956, whereby the employing enterprise or organisation guaranteed the employee’s loan for constructing new housing.[143] These enabled ‘workers, technicians, engineers, public employees, young married couples and members of collective agricultural households to access individual credit to build new housing.’[144] Decision 4015/1953 established a priority order[145] and a maximum cap for the credited amounts. The financial terms were extremely generous, as the required initial down payment was 10%, while the yearly interest rate was only 0.1%. Moreover, the necessary land for construction was made available by the state (although with retention of ownership), and the owners were exempted from property tax for 10 years.[146] These privileges, reminiscent of the monarchic legislation for residential constructions, were abrogated in 1977 as deemed no longer compatible with the socialist order.[147]

As mentioned, the communists maintained and steadily generalised the monarchic law’s incentives (i.e., cheap state credit and tax exemptions). The foundation was Decision 26/1966, by which the state offered the necessary land for construction and granted medium-term credits (15 years) with fixed interest (1% annually).[148] Newly built personal properties were exempted from taxes for 10 years, while those who made a down payment higher than the required 30% enjoyed more favourable credit terms.[149] These incentives were maintained by post-communist legislation, given that Decision 26/1966 was abrogated only in 1997.[150] The longevity of this normative act and its lasting effects are other arguments in favour of continuity and the success of credit activities for the population (Figure 4).

Legal continuation of Romanian residential credit laws. The figure illustrates the continuity of residential credit legislation throughout the three stages of Romanian history and their coexistence, despite ideological differences.

Subsequent laws expanded residential credit backed by a mortgage to more categories of consumers.[151] Decision 26/1966 was further implemented by Decree 445/1966 concerning state support for urban citizens in constructing private property dwellings[152] and Decree 713/1967 on the construction, by citizens, with state support, of vacation homes in touristic locations,[153] which became Law 19/1967.[154] Both decrees were replaced by Law 9/1968 for the development and sale of dwellings from the state fund to the population and the construction of personal vacation homes,[155] which unified and systematised the legal regime for residential credit.

The 1970s saw the peak of housing construction in Romania,[156] an unmistakable mark of the extent and success of residential credit during communism. Due to the state’s inability to continue building at the same pace and prices, it reverted to a system of housing construction based on the partnership between tenants and the cooperatives that had construction rights, with the aid of state loans, advancing, thus, the development of private property.[157] This effect was facilitated by the adoption of Law 4/1973 on the construction and sale of housing from the state fund to the population and the construction of personal vacation homes,[158] which abrogated Law 9/1968 and generalised the credit terms by consolidating all previous legislation into one comprehensive act. The premise of Law 4/1973 was the increased demand for more and better housing.[159] Construction continued to be financed by the population’s income, with cheap, long-term[160] state credit,[161] until the fall of communism.

The comprehensive housing policy of the communists produced spectacular results. Between 1951 and 1989, 5.5 million housing units were built in Romania, 2.98 million by the state, state-owned enterprises, cooperatives and local organisations and 2.54 million through the population’s private funds.[162] The communist type of residential credit enabled Romania to have one of Europe’s highest ratios of housing ownership.

4.3 The Contemporary Period (1990–Present)

The changes that occurred during the 1990s in the economic and political spheres during the transition from a planned economy to a free market, respectively, from a totalitarian regime to a democratic one, had a tremendously detrimental impact on housing construction and residential credit in Romania leading to the financialisation of housing. Several factors contributed to this: (a) a decrease in construction of new state-financed dwellings due to the economic downturn and shift in funding priorities, (b) a surge in demand for housing caused by a population increase following Ceausescu’s anti-abortion laws, (c) the abrupt liberalisation of prices for construction materials, and (d) the decrease in real earnings coupled with the anti-inflationist policies of the government, which significantly reduced the purchasing power of the population (Figure 5).[163]

Indices of real earnings in Romania 1990–1999. Source: Romania’s Statistical Yearbook 1990, 1998 and 2004. The figure illustrates the steep decline in real earnings in Romania during the first decade following the 1989 Revolution, which, coupled with high inflation, significantly affected the purchasing power of the population.

Nevertheless, the most crucial cause of the decline in new housing construction was the disappearance of the state-backed financing system based on fixed and affordable interest rates. Market forces could not react and resolve the disparities between the demand and offer of housing[164] (and when they did, they behaved in a predatory manner by setting extremely high-interest rates). At the same time, in opposition to the approaches of the monarchic or communist periods, the transition governments were unable and unwilling to intervene and support low-income families to acquire a home.

Law 4/1973 survived the 1989 anti-communist Revolution until 1991 when Law 50/1991 on the authorisation of construction works repealed it[165] and re-fragmented residential credit legislation. During the transition, the state withdrew from financing new constructions,[166] and most state-owned dwellings were privatised between 1990 and 1994.[167] Thus, while Law 50/1991 tackled the construction of new dwellings and vacation homes, Decree 61/1990[168] and Law 85/1992 addressed the sale of dwellings built from state funds.[169] The two systems ran parallel until a new residential credit regime was adopted in 1999.

Law 50/1991 initially provided that state banks and the House of Savings and Consignments would grant credits to consumers (referred to as natural persons) to build a dwelling or vacation home.[170] The tax exemption used during the monarchical and communist construction laws was maintained,[171] and more incentives to build new dwellings were added. However, Law 50/1991 failed to implement any rules for mortgage-backed credit, and the abrogation of Law 4/1973 generated a legislative gap that endured until the end of the 1990s.

To encourage the construction of new dwellings, Law 114/1996 on housing[172] restated several incentives such as a reduced tax on profits on investing in the construction of housing, exemption from property tax for 10 years for buyers,[173] and subsidised credits granted for a maximum period of 20 years by the House of Savings and Consignments, which remained a state-owned financial institution. Concerning the interest rate applicable to the loan, the law initially stated that it could not be higher than the interest practised in the financial-banking market. The interest was subsidised by 85% by the state.[174] Nevertheless, when the average interest rate amounted to 50% per year, the interest rate paid by the credit beneficiary was 7.5%, which doubled the credit value in 13 years. Thus, in 1997 it was changed to match the interest practised by the House for the population’s saving deposits plus 5%. Even so, the interest rates remained high and unavailable to the largest segment of the population.

Therefore, during 1992–1998, credit for building or acquiring housing (other than those sold by the state) was virtually nonexistent in Romania. According to a study by the Romanian National Bank, several economic, political and legal factors contributed to the complete decline of residential credit: a) the high inflation of 1991–1994 and 1997–1998 (which diminished the value of credits to be repaid and exposed banks to financial losses), b) the volatility of the labour market (which made banks reluctant to lend to natural persons or specific categories of employees), c) the banks’ preference for short-term loans with high interest made to the industry[175] (which minimised the availability of credit for the population), d) high-interest rates for mortgage credits (which made them unaffordable to most population), e) high costs for housing corroborated with the low income of the population, f) a general legislative and social instability regarding ownership rights, and g) slow judicial mechanisms of enforcing a debt (Figure 6).[176]

Average interest rates for non-banking customers including consumers and average annual inflation rates 1991–1998. Source: The Romanian National Bank Annual Reports. The figure illustrates the spikes in inflation that affected the early and late 1990 and the steep annual interest rates practised by the Romanian banks in their relationship with businesses and consumers. These two factors made residential credit granted on market terms unaffordable for most of the population.

The state ultimately intervened to address the situation during the creation of the National Agency for Housing in 1998,[177] which was enabled to grant credits secured by a mortgage for building, purchasing, rehabilitating, consolidating, or expanding a dwelling. For this purpose, the Agency could conclude special agreements with banking institutions to finance the credits at a lower interest rate than the financial market average.[178]

The legal framework for mortgages for the construction, purchase, rehabilitation, consolidation, and expansion of dwellings was implemented by Law 190/1999,[179] coupled with the Methodological Norms 3/2000 issued by the National Bank.[180] The law was a general instrument covering any mortgage agreement for consumers or professionals.[181] Other financial institutions could also give mortgage credits besides banks, the House of Savings and Consignments and the National Agency for Housing. The law set mandatory rules for the protection of debtors (prior disclosure of contractual terms, a ban on unilateral modification of terms, right to early repayment and limitation of administrative costs). Nevertheless, it did not solve the issue of variable interest in consumer contracts and left most financial matters at the mercy of contractual negotiation between credit issuers and their clients. This lack of regulation enabled the financial institutions to dictate terms via adhesion contracts. Interest rates remained high, and residential credit remained unaffordable for most of the population.[182] In 2001, for instance, the interest rate for credits granted to natural persons by the House of Savings and Consignments was 41% per year for housing credit,[183] which, in 10 years, quadrupled the nominal value of the granted credit. It should be mentioned that if in 2000, the inflation was 40%,[184] in 2001 it was down to 13.5% in 2001 and 8.6% in 2002[185] and would continue to decrease and stabilise in the next decade. This suggests that the previously high inflation levels could no longer justify the amount of interest charged.

Later, in 2002, Law 541/2002[186] on collective savings and loans for housing was passed, based on the German model of houses for savings. It was a short-lived return to the ideas and incentives that funnelled housing construction in the early monarchic years of the late 19th Century as it was abrogated and replaced by GO 99/2006 on credit institutions and capital adequacy.[187]

Even so, the adoption of a comprehensive regime for residential credits coupled with access to foreign capital banks on the Romanian markets slowly revitalised residential credit, an aspect confirmed by the increase in mortgage payments as a percentage of GDP from almost zero in 2000 to 3.6% at the end of 2007. However, loans for housing purchases were expensive in the private sector, exacerbated by the low availability of cheap state loans. Thus, foreign currency loans (with slightly lower interest rates) – mainly in Euros, but increasingly also in Swiss francs – were the main driver of growth, expanding rapidly (83% year-on-year in 2007) and accounting for almost 90% of total housing loans at the end of 2007. Since interest rates were very high compared to other European markets, it incentivised the banks’ leniency in crediting. The exposure of Romanian consumers to exchange rate risks and high interest were the main drivers of the 2007–8 financial crisis and the subsequent collapse of the residential credit market in Romania.[188] High interests and inefficient governmental credit support schemes for young couples or those purchasing or building their first housing[189] continue to plague the Romanian residential credit market (Figure 7).

a) and b) Internal short-term versus medium- and long-term credit granted to the population in Lei and foreign currency 1990–2004 (Values in Billion Lei. Source: Romanian National Bank, Annual Reports 1999, 2000, 2002, and 2004). The figures illustrate the low level of crediting the population during the first decade following the 1989 Revolution and the steep increase in crediting following the revamping of the legal framework governing residential and consumer credit in 1999. At the same time, the figures reveal the closing gap between medium and long-term credits (generally associated with residential credit) granted in Lei and those granted in foreign currency. As unaffordable interest rates plagued medium and long-term credits in Lei, Romanian consumers had no choice but to pursue credits in foreign currencies, which exposed them to the additional risk of exchange rates.

The above developments did not reverse the high ownership ratio that existed at the fall of communism. The trend continued and was consolidated during the early years of the transition due to the legislation that enabled the population to purchase housing built from state funds with affordable state credit[190] and at sale prices set at the 01.01.1990 level.[191] As a result, in 2022, 96.1% of dwellings in Romania are private properties, the highest percentage in the EU (Figure 8).[192]

Share of people living in households owning or renting their home, 2020. Source: EUROSTAT. The figure illustrates the high level of housing ownership in Romania, which was reached during the communist years and the early years of transition when the state-owned housing fund was privatised at low nominal prices and with cheap state loans. One should also notice that the first positions in the table belong to former communist states, which had similar approaches to housing and residential credit for the population.

4.4 Categories of Consumers

The banking legislation adopted during the interwar period favoured creating several Houses for Savings, Credit and Mutual Aid of different social categories – most of which were in a difficult economic situation – enabling them to access loans with low interest and favourable repayment terms. This concern is reflected by Law 80/1927, where housing credit was made available to specific categories of natural persons with lower incomes: state employees and retirees, persons with disabilities and war widows.[193]

The communists maintained a similar approach but, given the population’s increasing income and savings potential, steadily expanded the categories that could access residential credit to the urban citizenry (Decision 26/1966 and Decree 445/1966), followed by extensions via Law 9/1968 and generalised availability under Law 4/1973.

The consumer categories did not change after the 1989 Revolution. Law 50/1991 stated that natural persons (employees, peasants and retirees) benefit from credits and state subventions covering interest to build a dwelling or vacation home.[194] Moreover, the state incentivised specific categories of vulnerable consumers (married couples under 30 years, persons with disabilities, persons or families relocating from the cities to villages) to build a home with a state subvention of 30% of the construction’s value.[195]

If the communists restricted home ownership to a single dwelling, Decree 61/1990 adopted a milder stance stating that Romanian consumers[196] could purchase housing in instalments even if they already had one.[197] However, Law 85/1992 provided that one could not buy a dwelling built from state funds in instalments if they already owned a home.[198] Consumers under 30 years old, vulnerable categories (i.e., persons with disabilities)[199] and repatriated citizens[200] benefitted from more advantageous terms. Law 85/1992 also enabled ‘other categories of buyers’ than employees and retirees to purchase on credit by repaying directly at the House of Savings and Consignments, thus generalising the availability of residential credit for housing built from state funds.[201] This also meant the state-backed cheap loans for privatising its dwellings’ fund.

Generalisation and re-consolidation of credit for residential purposes were implemented via Law 190/1999.[202] However, the new regime opened the door to private creditors (commercial banks) and variable interest rates widespread in some EU countries (Table 5).

Comparison of categories of consumers that could access residential credit.

| Law 80/1927 | Decision 26/1966 | Decree 445/1966 | Law 9/1968 | Law 4/1973 | Decree-Law 61/1990 | Law 50/1991 | Law 85/1992 | Law 190/1999 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type and subject of credit | Residential | Residential & urban citizenry | Residential & urban citizenry | Residential & general population | Residential & general population | Residential & general population (no restrictions) | Residential & general population (no restrictions) | Residential and commercial & general population | Investment & general population and enterprises. |

4.5 Creditworthiness

Notably, under the monarchy or communism, all categories allowed to access residential credit enjoyed a stable income stream from the state, making them creditworthy. The monarchy favoured public employees and war widows, while the communists favoured employees (workers), the military and retirees. In both cases, a solid social and equitable element was involved. Under the monarchy, the beneficiaries of Law 80/1927 could not have a yearly income over Lei 200,000, could not own another dwelling and had to prove that they did not sell another dwelling in the past. The communists will later impose similar limitations, and these would survive (albeit amended) into the post-communist transition.

During communism, state support was first available through the Investment Bank of Romania for those who could provide evidence of savings of up to 30% of the dwelling’s value as a down payment.[203] Later, creditworthiness was assessed based on employment or retirement status and the length of savings deposited with the House of Savings and Consignments, which also determined the priority order (Table 6).[204]

Comparison of responsible lending elements in residential credit legislation.

| Law 80/1927 | Decision 26/1966 | Decree 445/1966 | Law 9/1968 | Law 4/1973 | Decree-Law 61/1990 | Law 50/1991 | Law 85/1992 | Law 190/1999 | RNB Norms 3/2000 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creditworthiness | Proof of stable income. | Proof of stable income. Evidence of savings. |

Proof of stable income. | Proof of stable income. Evidence of savings and length of deposits. |

Proof of stable income. | Proof of income. | Proof of income | Proof of income. | N/A | Proof of stable income. |

Interestingly, after the fall of communism and the revamping of residential credit, Law 190/1999 contained no provisions for assessing consumers’ creditworthiness. The matter was left entirely to the creditors by the National Bank’s Methodological Norms 3/2000.[205] The banks had to request proof of stable income; however, the norms allowed the indebtedness level to reach 50% of the consumer’s monthly net income.[206] This would have catastrophic consequences a decade later during the 2007–8 financial crisis when, the value of monthly instalments doubled or tripled because of changes in currency valuations for foreign denominated loans and increases in interest rates. Due to this phenomenon, coupled with the loss of jobs and decreased income, most consumer debtors could not meet their obligations and defaulted on their loans.[207]

4.6 Down-Payment Requirements

Anyone interested in accessing residential credit had to advance a down payment under the monarchist and communist regimes. Under the 1927 Construction Law, this varied between 10 and 20%, and the beneficiary had to prove that it had the land needed for construction.

In 1966, the communists solicited 30%,[208] although the rate lowered over time. From 1968, the down payment varied between 20 and 30% depending on the consumer’s income[209] and the length of the credit,[210] a differentiation which reflected the idea of equitable distribution and access to credit based on financial possibilities. From 1973, those needing additional credit to meet the down payment threshold or the remaining purchase price could obtain an unsecured loan from the House of Savings and Consignments for 5 or 10 years, with an 8% annual interest rate.[211] The minimum advance payment was not only a measure of what nowadays constitutes ‘responsible lending’ but also an indication of the population’s saving potential.

After the fall of communism, Law 50/1991 did not specify any down payment requirements. However, for vulnerable categories, the 30% state subvention was likely deemed as a down payment by banks with state capital and the House of Savings and Consignments.[212]

Conversely, Decree 61/1990 replicated most provisions of the communist legislation, with better terms for the vulnerable categories. The minimum down payment was 30%, while vulnerable individuals could deposit only 10%.[213] Moreover, those who could not meet the down payment requirement could obtain a credit from the House of Savings and Consignments for 5 years at a yearly legal interest of 5%. Favoured categories of consumers could get a credit facility for the down payment for 10 years, with an interest rate of only 3%.[214] Law 85/1992 lowered the down payment to 10%,[215] probably encouraging purchases and aiding the population, which started to feel the economic downturn. At this point, it is apparent that the legal mechanism of fixed interest was still applicable in the same manner it was employed by the communists, despite the high inflation rate.

Finally, Law 190/1999 and the National Bank’s Methodological Norms 3/2000 did not include any provisions concerning a minimum down payment, leaving the matter to the creditors. Removing the minimum requirements for advance payments implemented by the communists had a devastating effect on the viability of credits a decade later because of the reckless granting and taking of residential credit (Table 7).

Comparative down payment requirements for residential credits.

| Law 80/1927 | Decision 26/1966 | Decree 445/1966 | Law 9/1968 | Law 4/1973 | Decree-Law 61/1990 | Law 85/1992 | Law 190/1999 & NRB’s methodological norms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Down payment | 10% (public officers and pensioners)/20% + land | 30% or more | 30–40% | 20–30% | 20–30% | 30% or more/10% for under 30 years | 10% | N/A |

4.7 Duration and Cost of Credit

Under the 1927 Construction Law, the remaining credit was released in instalments over 20–30 years[216] as the dwelling’s construction progressed.[217] Credit repayment took place in two yearly instalments.[218] Thus, although income was available, significant discipline was needed to ensure enough was saved for the payments. The annuity bore an interest of 1% over the National Bank’s interest rate for public employees and retirees and 2% for other beneficiaries.

The communists opted for monthly payments. Under Decree 445/1966, the credit had to be repaid in 15 years maximum, in equal monthly instalments, with an annual legal interest of only 1%.[219] The explanation for the terms’ generosity lies either with the law’s addressees (urban citizenry and, probably, state employees) or the low risk of non-payment. At the time, unemployment was almost non-existent, and incomes steadily grew due to extrinsic (economic recovery) and intrinsic factors (party ideology and planned economy). The ideological positioning towards interest could also be a reason for the low level of interest, although rates will increase in the following years.

In 1973, the repayment period was extended to 15–25 years. However, the extension made credit more expensive. Interest varied between 1.5–3%[220] and 2–5% per year, depending on the consumer’s monthly salary.[221] The differentiated interest levels were indexed to wages, meaning those with higher incomes paid higher interest rates. This followed the principles of fairness and stimulation that still justified the use of interest by the communist credit system, thus enabling those with lower income to access credit more easily. It also suggests a concern regarding the indebtedness levels of consumers because a uniform interest rate would have been more cumbersome for lower-income employees and exposed them to a higher risk of non-payment.