Abstract

Background

Bleeding into the vertebral canal causing a spinal haematoma (SH) is a rare but serious complication to central neuraxial blocks (CNB). Of all serious complications to CNBs such as meningitis, abscess, cardiovascular collapse, and nerve injury, neurological injury associated with SH has the worst prognosis for permanent harm. Around the turn of the millennium, the first guidelines were published that aimed to reduce the risk of this complication. These guidelines are based on known risk factors for SH, rather than evidence from randomised, controlled trials (RCTs). RCTs, and therefore meta-analysis of RCTs, are not appropriate for identifying rare events. Analysing published case reports of rare complications may at least reveal risk factors and can thereby improve management of CNBs. The aims of the present review were to analyse case reports of SH after CNBs published between 1994 and 2015, and compare these with previous reviews of case reports.

Methods

MEDLINE and EMBASE were used for identifying case reports published in English, German, or Scandinavian languages, using appropriate search terms. Reference lists were also scrutinised for case reports. Twenty different variables from each case were specifically searched for and filled out on an Excel spreadsheet, and incidences were calculated using the number of informative reports as denominator for each variable.

Results

Altogether 166 case reports on spinal haematoma after CNB published during the years between 1994 and 2015 were collected. The annual number of case reports published during this period almost trebled compared with the two preceding decades. This trend continued even after the first guidelines on safe practice of CNBs appeared around year 2000, although more cases complied with such guidelines during the second half of the observation period (2005–2015) than during the first half. Three types of risk factors dominated:(1)Patient-related risk factors such as haemostatic and spinal disorders, (2) CNB-procedure-related risks such as complicated block, (3) Drug-related risks, i.e. medication with antihaemostatic drugs.

Conclusions and implications

The annual number of published cases of spinal haematoma after central neuraxial blocks increased during the last two decades (1994–2015) compared to previous decades. Case reports on elderly women account for this increase.Antihaemostatic drugs, heparins in particular, are still major risk factors for developing post-CNB spinal bleedings. Other risk factors are haemostatic and spinal disorders and complicated blocks, especially “bloody taps”, whereas multiple attempts do not seem to increase the risk of bleeding. In a large number of cases, no risk factor was reported. Guidelines issued around the turn of the century do not seem to have affected the number of published reports. In most cases, guidelines were followed, especially during the second half of the study period. Thus, although guidelines reduce the risk of a post-CNB spinal haematoma, and should be strictly adhered to in every single case, they are no guarantee against such bleedings to occur.

1 Introduction

Spinal haematoma (SH) is a rare but serious complication of central neuraxial blocks (CNB), i.e. spinal (SPA), epidural (EDA), or combined spinal–epidural (CSE) techniques for pain relief during and after surgery, during labour, and for chronic pain. In the 1990s, the risk per procedure in Sweden was 1/160,000 after SPA, and 1/18,000 after EDA [1].The incidence varies from 1/200,000 after labour pain relief to 1/3600 in women after total knee replacement [1], and, similarly, 1/3600 after cardiac surgery [2].

In 1992, 1994, and 1996 case reviews, analysing 29, 61, and 51 cases of SH after neuraxial blocks respectively, between 1906 and 1996, were published 3,4,5]. Since then, several changes in the perioperative management of surgical patients have occurred. Thromboprophylaxis (Tpx) with low molecular heparin (LMWH) has been established, ADP-inhibitors, and, since 2002, fondaparinux and new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) such as dabigatran and rivaroxaban, have been introduced. Effective pain relief with neuraxial analgesia, such as CSE and prolonged EDA, have been used increasingly. More elderly patients are having major surgery, requiring both Tpx and CNB. Chronic medication with anticoagulants and platelet inhibitors is more common, especially among elderly, at the same time as guidelines for the management of CNB in patients at risk of SH have been published (e.g. [6-9]). All these measures tend to have an impact on the risk of SH after CNB, and indicate that the information from the previous reviews more than 20 years ago [3,4,5] now needs to be updated.

Ideally, guidelines should be based on evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses. For spinal haematoma after CNB, however, RCTs are impossible: guidelines have to rely on clinical experience and drug pharmacology [6,7,8,9]. Case reports are important sources of clinical experience [10].

The aims of the present study were to analyse demographics and risk factors (part 1), diagnosis, treatment, location of the spinal haematomas, and outcomes (part 2) reported in case reports of SH after CNB published between 1994 and 2015, and also changes of these variables over time. Adherence to guidelines issued to reduce the risks of spinal haematoma was also assessed.

2 Methods

2.1 Literature search

MEDLINE and EMBASE were accessed to find case reports published in English, German, and Scandinavian languages between 1994 and end of 2015 using the search terms “spinal”, “haematoma”, “haemorrhage”, “bleeding”, and “anaesthesia” in various combinations. Reference lists of the articles obtained, as well as from other relevant literature, were also scrutinised for additional case reports.

2.2 Selection of cases for analyses

Reports on concurrent intramedullary trauma caused by direct needle entrance into the spinal cord were excluded. For a case report to be of informative value, the following information was required: gender, type of intervention, type of block (spinal, epidural, or combined, level of insertion, single shot or indwelling catheter), as well as symptom(s), diagnostic method, and treatment of the haematoma, and ultimate outcome of the patient. Reported details about the CNB procedure, such as number of attempts, “bloody tap”, and unintended dural puncture were noted. Time from the procedure to 1st symptom, diagnostic methods, and time from 1st symptoms of an SH to laminectomy (in case of surgical evacuation of the haematoma), and outcome, (part 2) were also noted.

2.3 Comparisons

The results of the present study were compared with those of similar studies published over 20 years ago [3,4,5].Also, case reports from the first half of the study period (1994–2004) were compared to those from the second half. In demographic comparisons (age and gender), all obstetric cases were excluded. For comparison with nation-wide frequencies of various operations (orthopaedic and vascular surgery) and also changes in drug prescriptions over time, Sweden was chosen as reference country.

2.4 Statistics

Information extracted from each case report was categorised and noted on an Excel spreadsheet, and each category was analysed separately and in combination with others. Not all case reports had information about all non-mandatory variables. The number of informative reports was used as denominator for calculation of occurrences in per cent.

Differences between study groups (first half vs. second half of the years between 1994 and 2015) were analysed with the Chi square test. A P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

3 Results and discussion

3.1.1 Literature search

A sum of 147 published articles, case reports or letters [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157], describing altogether 169 cases relevant for this review were found. Three of these were excluded: a newborn child with multiple malformations, who developed a subdural spinal haematoma after a lumbar epidural catheter [155], and two patients where the cause of the haematoma was uncertain [156,157]. Thus,166 case reports from 25 countries were analysed. Sixtyfour cases came from Europe, 53 from North America, 4 from South America (Brazil),39 from Asia and 6 from Australia. There was a minor overlap (8 cases [11,12,14,*16(2)*,17,18,21]) between this review and that of Wulf[5].

3.1.2 Demographics

Of the 166 reports, there were 109 female cases, of which 14 cases were obstetric. Among the non-obstetric cases, there were 95 (63%) women, with a median age of 72 years, and 57 men, median age 66.

3.2 Neuraxial blocks

3.2.1 Conventional blocks (Table 1)

Spinal block (41):37 single shots (of which two were attempted epidurals, converted to SPA [20,121] and 4 continuous blocks, of which one haematoma (25%) appeared after catheter removal.

Type of “conventional” CNB (there were also 4 SCSs not accounted for here).

| Final block | Successful | Failed, intended block | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Lumbar | Thoracic | Cervical | Total | Single shot | Continuous | ||

| Spinal | 41[a] | 41 | 37 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Epidural | 49 | 46 | 6[b] | 101 | 17 | 84 | 1 |

| Combined | 14[c] | 14 | 14 | 1 | |||

| Total | 104 | 46 | 6 | 156 | 54 | 102 | 6 |

Epidural block (101):49 lumbar(12single shots),46 thoracic(all continuous), and 6 cervical locations (5 single shots, one of which also received a lumbar single shot [139]; the haematoma had acervical location,1 continuous).Thus, 17EDAwere single shots, and 84 were continuous. Of these latter, 55 haematomas (65%) appeared after catheter removal.

Combined spinal and epidural block (14): Nine of these (64%) appeared after catheter removal.

Additionally, 6 abandoned/failed procedures (4 SPA,1 EDA,1 CSE) were converted to general anaesthesia because of difficulties in performing the blocks.

3.2.2 Spinal cord stimulators

There were four percutaneous implantations of spinal cord stimulators (SCS), one thoracic, two thoraco-lumbar, and one lumbar, causing SH. Two of these appeared after removal of SCS trial leads.

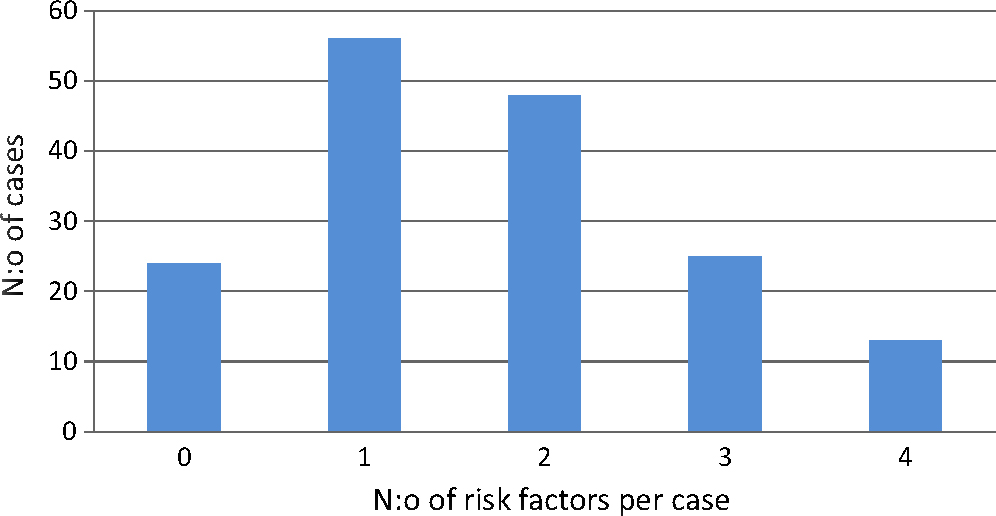

3.3 Risk factors (Fig. 1)

Recognised risk factors are of three main categories: those related to the patient’s health problems, those related to the CNB procedure (multiple attempts and “bloody tap”), and those related to drugs taken by the patient close to the procedure. There were 0-4 risk factors reported in each case, and the distribution of risk factors per case is shown in Fig. 1. In 24 cases, no risk factor was described; 18 of these specifically stated that no risk factor was present. Twelve patients were described to have all three kinds of risk factors. Details of the various kinds of risk factors are shown in Tables2,3,4.

Risk factors per case, obtainable from each report. Risk factor=complicated block (bloody tap), spinal or haemostatic disorder, or anti-haemostatic medication in the perioperative period.

Patient related risk factors.

| Disorder | No. of cases |

|---|---|

| Spinal stenosis | 14 |

| Spinal tumour | 6 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 4 |

| Osteoporosis | 4 |

| Herniated disc | 2 |

| Scoliosis | 2 |

| Spondylosis | 2 |

| Spina bifida occulta | 1 |

| Dural AV-fistula | 1 |

| Spinal AVM | 1 |

| Spinal disease (total) | 37 |

| Thrombocytopaenia[a] | 13[b] |

| Renal insufficiency | 10 |

| INR ≥1.5 | 6[c] |

| Liverdisease | 4 |

Complicated blocks by type of complication and type of block (abandoned blocks included). Multiple attempts = more than one skin penetration, bloody tap = sanguineous CSF or blood from an intraspinal catheter or needle. CSE = combined spinal/epidural anaesthesia.

| Intended block | Spinal n = 40[a] | Epidural n = 89[a] | CSE n = 14[a] | Total n = 143[a] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple attempts only | 18 (45) | 16 (18) | 3 (23) | 37 (26) |

| Bloody tap only | 2 (5) | 5 (5.6) | 1 (7.7) | 8 (5.6) |

| Both | 4 (10) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (7.7) | 6 (4.2) |

| No. of cases with complicated block | 24 (60) | 22 (25) | 5 (38) | 51 (36) |

| Total no. of cases with multiple attempts | 22 (55) | 17 (19) | 4 (31) | 43 (30) |

| Total no. of cases with bloody tap | 6 (15) | 6 (6.7) | 2 (15) | 14 (9.8) |

-

Numbers within brackets denote percentage of all informative cases. Spinal cord stimulators not included.

Drug classes reported, in order of frequency. Missing data = 6.

| No. of cases (percentage) | |

|---|---|

| Low molecular weight heparin | 50 (31) |

| Unfractionated heparin | 39 (24) |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 25 (16) |

| Vitamin-K antagonists | 17 (11) |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 17 (11) |

| Dextran | 6 (3.8) |

| Fibrinolytics | 4 (2.5) |

| ADP receptor inhibitors | 4 (2.5) |

| Phosphodiesterase inhibitor (dipyridamole) | 2 (1.3) |

| Direct fXa inhibitor (rivaroxaban) | 2 (1.3) |

| Direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran) | 1 (0.6) |

| Fondaparinux | 1 (0.6) |

| Selective serotonin receptor inhibitor | 1 (0.6) |

3.3.1 Patient-related risk factors (Table 2)

Most common patient related risk factors were various forms of spinal disorders (37 cases), with spinal stenosis (14 cases) as the most common diagnosis, followed by perioperative thrombocytopaenia (platelet count <150 X 109/L,13 cases). However, in only 7 cases, two cardiovascular [28,119] and three obstetric [46,116,120], one patient with a postoperative idiopathic thrombocytopaenic purpura [111], and one patient with ileus [117], were platelet counts below 80 X 109/L, which has been suggested as the limit value for safe spinal or epidural anaesthesia [158], reported. Renal insufficiency was reported in 10 cases, in 9 of those together with other risk factors: 3 cases with unfractionated heparin (UFH) + Dextran, 5 cases with LMWH (3 enoxaparin, 2 dalteparin) + additional drugs(2 clopidogrel, one warfarin, one aspirin, and one ketorolac, and one case with ketorolac + spinal stenosis.

3.3.2 Risk factors related to the CNB-procedure (Table 3)

Obviously, SCS is a risk factor per se, since it is performed with large bore needles (14G), and stiff, traumatic electrodes [159]. These are therefore accounted for in Section 3.4.1.1.Only “conventional” CNBs are accounted for in this section.

Procedure-related complications (multiple attempts and/or bloody tap) were reported in 51 patients (36%), with a much higher incidence (60%) during SPA than the other forms of CNB.

Multiple attempts were reported in 30% of CNBs, which is somewhat less than reported in a prospective study of 595 spinal and epidural anaesthetics (without neurological sequelae), with 36% multiple attempts [160]. In the epidural group in the present review, multiple attempts were reported in 19% of the cases, the same magnitude as reported by Pöpping et al. in a retrospective review of more than 14,000 epidurals (19%) [100].Thus, among the present cases, multiple attempts were not more common than in everyday clinical practise, and cannot be designated as an obvious risk factor for developing spinal haematoma. This seems logical, since most failed attempts depend on inability to enter the intraspinal space because the needle is hampered by bony structures. In such cases, a vessel trauma would occur outside of the spinal canal and may at the most cause a soft tissue haematoma.

Bloody taps were reported in 15% during SPA, 6.7% during EDA, and 15% during CSE, 9.8% overall. Horlocker et al. [161] reported 3.3% bloody taps in a retrospective review of 4767 spinal anaesthetics. Pöpping et al. [100] reported 2.1% bloody taps during EDA. The substantially higher percentage of BT in the present study indicates that bloody tap is a major risk factor for developing spinal haematoma.

3.3.2.1 Catheter placement or removal causing the SH?

Continuous CNBs were used in 102 patients (Table 1).In 32 cases, symptoms and signs from the SH started while the catheter remained in situ, in 2 of these directly after manipulation of the catheters. In 65 cases, symptoms started after removal of the catheter. Five reports were inconclusive. In 25 of the 65 cases (38%) it is likely that the haematoma was caused by the removal; in 15 of these 25 (60%), the patient was treated with a thromboprophylactic drug.

3.3.3 Drug-related risk factors (Table 4)

These were the most common risk factors in the present (Table 4) as well as in previous reviews [3,4,5]. Intake of antihaemostatic drugs was reported in 105 cases (66%, 6 reports were indeterminable). In 47 of the cases, more than one antihaemostatic drug was implicated; in 12 cases even three such drugs.

3.3.3.1 Heparins

Unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) are recognised risk factors for SH after a CNB. Eighty-three patients, 56 women and 27 men received these, in six cases (5 men,1 woman) both drugs. The prevalence of heparins in non-obstetric cases was 59% among women, and 47% among men.

Among the 143 peri-operative cases, postoperative thromboprophylaxis was generally achieved with LMWH (50 cases), followed by UFH (27 cases), while 10 patients received other forms: warfarin(2), rivaroxaban (2), active stockings (2), platelet inhibitors (2), fondaparinux (1), and dabigatran (1). In 56 cases, there was no mentioning of thromboprophylaxis, but in at least 25 of these there was a strong indication for it according to international guidelines [162]. In several of these cases, a “bloody tap”, or early signs of an SH, may have prevented the initiation of Tpx.In a majority of cases though, the lack of mentioning probably reflects unreported (or substandard) treatment.

3.3.3.2 Vitamin-K antagonists

Vitamin-K antagonists (VKA, mainly warfarin) were reported in 17 cases (11%). In one patient, an 85-year old woman whose epidural catheter was removed during on-going VKA treatment for thromboprophylaxis at an INR of 6.3 [40], this drug was the obvious cause of the haematoma. In the other cases, INR or the PT-time was only slightly elevated. In 13 cases, the VKA treatment had been interrupted for 2–14 days, INR was <1.5, except for 1.84 in one case [42]. Other drugs, mainly LMWH or UFH, in one case even acetylsalicylic acid, may as well have contributed, in combination with VKA, to the haematoma.

3.3.3.3 New anticoagulants

Among the “new” drugs, fondaparinux was implicated in one case [144], dabigatran in one case [135] and rivaroxaban in two cases [146,152]. In the case of fondaparinux, the drug was given postoperatively together with low dose warfarin because of pulmonary embolism; both drugs were given after removal of an epidural catheter, and the treatment continued until 12 days later, when neurologic symptoms started; INR was 1.51 at that time [144]. In the case of dabigatran, the patient had chronic medication because of atrial fibrillation. Dabigatran was discontinued for seven days before an epidural steroid injection, and restarted 24 h thereafter, which complies with guidelines [159]. Symptoms started after another 24 h. In one of the cases with rivaroxaban [146], the patient received both warfarin and enoxaparin postoperatively after knee arthroplasty (POD 0–3), but was switched to rivaroxaban on POD 4. Neurologic symptoms started at home 2 days later. At hospital arrival, INR was 0.9. In the other case [152], Tpx with rivaroxaban was started on the night after a knee arthroplasty, with an epidural catheter in place. This was removed 18 h later, whereupon the next dose of rivaroxaban was given after 6 h. Twelve hours later, the patient developed signs of an SH. In this case, rivaroxaban did undoubtedly contribute to the SH, in the other three cases [135,144,146] it may be argued that other drugs may have contributed as well. Furthermore, two cases implicating fondaparinux have been briefly reported in a large survey from Finland [163].

3.3.3.4 Fibrinolytic drugs

Fibrinolytics were given intraoperatively to four patients (1 alteplase [75] and 3 urokinase [26,28,38]), one undergoing aortic valve replacement (alteplase), and three vascular surgery. All of them also received UFH, in one case together with LMWH.

3.3.3.5 Antiplatelet drugs

Acetylsalicylic acid drugs (ASA) were reported in 25 cases (16%), in 5 of these the only drug implicated, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) in 17 cases (11%). NSAIDs are probably underreported, in Sweden approximately 20% of all inhabitants over 40 y of age were prescribed NSAIDs in 2005 (the median year of the study period) [164].This is especially so among the orthopaedic cases, where NSAID therapy is basic due to its analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties; however, intake of NSAID was reported in only 5/48 orthopaedic cases (10%). The reason for not reporting NSAIDs may be that these are relatively weak inhibitors, and therefore not considered risk factors [165,166].

Clopidogrel was reported in 4 cases, but there was no case report implicating any of the newer antiplatelets, such as prasugrel and ticagrelor, or the more potent platelet inhibitors such as GP IIb/IIIa-blockers.

3.4 Types of surgery or procedure

Treatment of chronic pain with EDA caused 21 haematomas,17 (5 cervical, 4 thoracic, and 8 lumbar) after steroid injections, and 4 after percutaneous applications of spinal cord stimulators (SCS).

Treatment of labour pain caused 3 haematomas (all EDA).

Treatment of acute perioperative pain caused the remaining 142 haematomas. The following surgical specialties were represented (number of cases in parenthesis):

Orthopaedics (48)

General surgery (32)

Vascular surgery (26)

Thoracic surgery (12)

Obstetrics (c-section) (11)

Urology (11)

Gynaecology (2)

3.4.1 Procedures of special interest

3.4.1.1 Chronic pain treatment

Of special interest are implantations of spinal cord stimulator trials (SCS). There were three articles [131,138,142] reporting four cases of spinal epidural haematomas after SCS, the first one published 2012. In 2015, an international task force of several pain societies published the first guidelines for interventional spinal and pain procedures [159]. In these, SCS is designated as a high-risk procedure, as compared to conventional epidural placement, which is classified as intermediate risk. The reason for the higher risk classification of SCS is because it is more traumatic, with large bore needles (often two 14 G needles) and stiff styletted leads. Such an increased risk is confirmed in a large cohort of patients undergoing stimulator implantations, either percutaneously or surgically via laminectomy [167]. The incidence of spinal haematoma after percutaneous implantation was 0.75% [167], which is approximately 150 times higher than after conventional epidural anaesthesia. It has been speculated that the surgical approach would be safer, since damaged vessels are visualised, as opposed to the blind, percutaneous technique. However, the incidence of SH after open implantations was 0.63%, not significantly different from the percutaneous approach [167]. Also, in a report of 154 patients undergoing surgical implantations, performed by one surgeon, there were 4 spinal epidural haematomas (2.6%) [168].

3.4.1.2 Orthopaedic surgery

This was the specialty with the highest frequency, 34% of all surgical cases. In the Swedish registry, orthopaedic surgery represents only around 20% of all major operations [164]. However, this may not indicate that orthopaedic surgery per se is a specific risk factor, since CNBs are employed more often for orthopaedic surgery than in most other specialties. Knee arthroplasty was the single most common type of surgery reported, with 14% of all surgical cases, and 43% of all orthopaedic cases. This operation was obviously overrepresented; only 1.5% of all operations and 7.1% of all orthopaedic operations performed in Sweden between 1998 and 2015 were knee arthroplasty [164]. In the US the corresponding figures were 2.5% and 12.9% respectively, in 2010 [169] (the difference may be explained by an almost 20% higher average BW in the US [170]). Hip arthroplasty represented 13.1% of orthopaedic surgery, and 2.7% of all surgery in Sweden [164] but there were only five patients (3.6% of all surgical cases) undergoing this operation among the case reports of SH. It is also notable that 80% of knee arthroplasty patients in the present review were women. In the Swedish surgical database, 62% of the patients undergoing knee arthroplasty were women [164]. In the US, the corresponding figure was 63% in 2006 [171]. Thus, the present review indicates that elderly women having a knee arthroplasty under CNB have a relatively high risk of developing an SH. This agrees with the results of Moen et al. [1], who found women undergoing this operation under epidural anaesthesia to be the subgroup with the highest incidence of spinal haematoma, 1/3600 compared with 1/18,000 in the entire population of patients having epidural anaesthesia [1].

The reason for the high incidence of SH among patients undergoing knee arthroplasty, not seen during hip arthroplasty, is unclear. Theoretically, a fibrinolytic effect of the tourniquet often used during knee arthroplasty [172] might have contributed. However, no signs of increased bleeding tendency in terms of postoperative blood loss have been demonstrated in any of several metaanalysis comparing tourniquet vs. non-tourniquet operations (e.g. [173,174]). More patients received UFH or LMWH after knee arthroplasty (74%) than after any other form of surgery. Many orthopaedic patients with osteoarthritis are treated with NSAIDs, and the combination of heparin and NSAID was pointed out by Heller and Litz [175] as a possible explanation to the high incidence of post-CNB SH in orthopaedic patients. Of the 142 surgical cases in the present review, this combination was reported in 8 cases, and five of these were orthopaedic patients (one knee arthroscopy, one hip arthroplasty, three knee arthroplasties). But, as pointed out above, NSAIDs are probably underreported, not least in orthopaedics.

Of the 116 cases with epidural anaesthesia (including CSE), 16 (13.8%) were because of knee arthroplasty. In Wulf’s review, with 51 epidurals, only two (3.9%) were for knee arthroplasty [5]. This difference between the present findings and those of Wulf [5] is most certainly explained by a much higher rate of knee arthroplasty in recent years. In Sweden, this operation was introduced in the mid-seventies, i.e. occurred only in the second half of Wulf’s study period, and its incidence was increased from a few cases in 1975 to 2800 in 1994, and was further increased to 14,100 in 2015 [164,176].

3.4.1.3 Vascular surgery

Eighteen per cent of all post-CNB SHs occurred after vascular surgery, a specialty that represents only 2.6% of all operations performed in Sweden [164]. In common with orthopaedic surgery however, the frequency of operations performed under CNB is relatively high in vascular surgery. Operations typically suited for CNB (aortic and infrainguinal vascular surgery, and varicose vein surgery) amounted to more than 60% of all vascular surgery in Sweden [164], but this can only partly explain the high number of vascular cases in the present review of spinal haematoma after CNB. The reason for this is most certainly related to laboratory findings and/or perioperative drugs: in nine cases, lab data indicated altered haemostatic function, 12 patients were prescribed one or more drugs with antihaemostatic effect, in all but four cases of vascular surgery the patients were reported to receiveUFH intraoperatively, in 4 cases together with dextran and in 3 cases with fibrinolytic drugs (urokinase or alteplase). Six patients received perioperative LMWH as well.

Also with respect to vascular surgery the findings correlate well to those of Moen et al. [1], who reported 8 cases related to vascular surgery or 26% of all surgical cases with SH in their study.

3.4.1.4 Gynaecology was not associated with a high risk of SH

A surprising finding is that, despite the high incidence of SH among female patients, gynaecology was only represented in two case reports. One was an 87-year old woman undergoing “minor surgery” under spinal anaesthesia [70], and one was a 67-year old woman undergoing vaginal hysterectomy, who received UFH intraoperatively, and also close to the removal of her epidural catheter [60]. There were 14 obstetric cases, 11 caesarean sections and 3 vaginal deliveries.

3.5 Limitations and strength of the present study

At its best, evidence based practice and guidelines are based on meta-analyses on a large number of randomised controlled trials (RCTs). But, as pointed out in an editorial in Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Medicine [10] “many important questions cannot be answered using a randomised controlled clinical trial”. Although not mentioned in the editorial, post-CNB spinal haematoma, because of its rarity, may be one of the most obvious examples of such questions. Apart from pharmacological aspects of drugs that are included, and a few epidemiological studies (e.g. [1,163,177]), existing guidelines are based on compilations of case reports like those from the 1990s [3,4,5], which are still frequently cited. As with most studies, a review of case reports has its shortcomings. The most important one may be that there is no denominator for calculation of over-all incidences, and it is impossible to tell whether included reports are representative of all cases of post-CNB SH. On the other hand, any biases would even out the more cases that are included. This one is by far the biggest sample of case reports on post-CNB spinal haematomas ever published. There is no reason to believe that the results of the present review would be systematically biased towards one or the other direction. In fact, many of the findings in the present study are corroborated by epidemiological studies, such as those by Moen et al. [1] and Pitkänen et al. [163].Obvious examples are the clear overrepresentation of female patients (Section 3.6.2), and knee arthroplasties, which are almost exactly consistent with the results from those studies [1,163]. The present study includes 166 cases. With a rough incidence of post-CNB SH between 1/50,000 [1]and 1/100,000 [163], this number of cases in an epidemiological investigation would have to be based on somewhere between 8.5 and 17 million neuraxial blocks. Furthermore, the present cases are collected globally, from 25 countries representing all continents except for Africa. An epidemiological study of that width and size seems difficult, if not impossible, to carry out. So, it could even be argued that the advantages with a review like the present one outweigh the drawbacks, but nevertheless, the results should be interpreted with caution. This is also because of underreporting. As mentioned above, there is reason to believe that intake of, above all, ASA and NSAIDs is markedly underreported. Also the postoperative administration of LMWH seems to be underreported. Thus, these drugs, especially in combination, may cause an even greater risk than can be implicated from the present study.

Finally, Sweden was chosen as reference country for comparisons with nation-wide frequencies of operations and drug prescription over time, because of its reliable, easily accessible, and updated databases [164,176], enabling calculation of subgroup frequencies. Sweden has a population of 10 million people and a highly qualified health care; still it can only be assumed that Sweden is representative of all countries of origin of the case reports. On the other hand, there is no reason to believe that similar trends with respect to surgical panorama and drug prescription do not exist in those countries.

3.6 Comparison of the 1994–2015 results with those of previous reviews

3.6.1 Increasing numbers of spinal haematomas after CNB published as case reports

An annual average of 7.5 published cases of SH in the years 1994–2015 was identified. During the 18 preceding years, from 1976 to 1993, an average of only 2.5 case reports were published per year [4]. Of the 166 reports, 82 were published during the first part of the observation period (1994–2004), and 84 were published during the second part (2005–2015). Thus, the annual number of published case reports from 1994 to 2015 was trebled when compared to the previous two decades, and thereafter kept on a relatively steady level. Whether this reflects an increased utilisation of CNB, or indicates an increased incidence of post-CNB SH, or both, or whether it depends on publication bias cannot be firmly established by the present review. However, it seems unlikely that such a marked increase in reports would not mirror an actual increase in the incidence of post-CNB SH globally since the mid-nineties. In that case, the main reason would most probably be related to an increase in prescription and administration of anti-haemostatic drugs (Section 3.7.2).

3.6.2 Increasing numbers of spinal haematomas in elderly women

The present data clearly indicate that SH has become more common among women, and especially elderly women, during the last 20 years. In Wulf’s review [5], there were 23 male and 16 female cases, apart for 4 obstetric cases (8 missing data), median age 68 years in both groups. Fig. 2 shows the distribution of age and gender of non-obstetric cases in this review, (ranging from 1996 to 2015), compared with the corresponding figures from Wulf’s study [5] (1952–1995). This clearly shows the transition from male to female dominance among the cases (from 41% to 63% women), especially among elderly (≥60 years).

In accordance with Wulf [5], Schmidt and Nolte [3] reported only 9 women (31%) in their material of 29 cases, with a mean age of 62.6 years. Also, as little as 36% of more than 600 cases of mostly spontaneous spinal haematomas occurring between 1826 and 1996 were women [180].

Two later studies on post-CNB spinal haematoma report gender and age ratios similar to the ones in the present review. Moen et al. [1]report 22 women among their 31 non-obstetric cases (71%). Of those,18 (82%) were 70 years or older. Furthermore, they report an increase of cases during the second half of the 90s, when LMWH had been established for postoperative thromboprophylaxis in Sweden, 24 cases vs. 9 cases during the first half [1]. Pitkänen et al. [163] reported 9 women (69%) among 13 cases with post-CNB SH during 2000–2009 in Finland. Eight of these women were ≥70, and all those received LMWH. Only three of the patients in Wulf’s review (up and to 1995) received LMWH [5]. The “standard” dosage of LMWH does not respect weight, gender, or age. Two studies indicate that the pharmacokinetics of UFH [178] and LMWH [179] (in weight-adjusted dosage) are different in women and men, leading to increased sensitivity to these drugs in women compared with men. An increased prescription of LMWH, together with a higher susceptibility for heparin effects, may be one explanation to the higher prevalence of heparins among women than men, and also to the striking increase of post CNB spinal haematoma in elderly women after 1995 (Fig. 2).

![Fig. 2

Age distribution in the present study (1996–2015, light shaded bars) compared with Wuif,s study (1952-1995, dark shaded bars) [5] among men (left panel) and women (right panel, only non-obstetric cases). Note the transition to female dominance after 1995. Missing data from the period 1952–1995 = 5, from the period 1996–2015 = 2.](/document/doi/10.1016/j.sjpain.2016.11.008/asset/graphic/j_j.sjpain.2016.11.008_fig_005.jpg)

Age distribution in the present study (1996–2015, light shaded bars) compared with Wuif,s study (1952-1995, dark shaded bars) [5] among men (left panel) and women (right panel, only non-obstetric cases). Note the transition to female dominance after 1995. Missing data from the period 1952–1995 = 5, from the period 1996–2015 = 2.

3.7 Changes during the period 1994–2015

3.7.1 Effects of guidelines for reducing risks of spinal haematoma

In order to reduce the incidence of spinal haematoma in patients with increased risk, several national and international working groups have issued guidelines for safe administration of neuraxial anaesthesia. These guidelines define what should be safe time intervals from the last administration of an antihaemostatic drug to the CNB procedure and from a CNB procedure to the next administration of such a drug. The pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties of the drugs, the elimination rate in particular, determine these “safe” intervals [6,7,8,9,159,185].

The first guidelines published in an international journal were issued in United States 1997 [6], and these were followed by several national guidelines issued around the turn of the century, e.g.: Norway 1994, Europe 1998, Sweden and Belgium 2000, Germany and The Netherlands 2003, Austria 2005. Considering a delay of at least a couple of years from the occurrence of a case until its publication, it is reasonable to assume that most cases published during the first part of the observation period (i.e. 1994–2004) occurred before guidelines were published, whereas most cases from 2005 to 2015 occurred after such guidelines had become well known.

During the period 1994–2004 in about 30% of the published case reports, the clinicians did not comply with guidelines, compared with only 7.5% in the period 2005–2015 (P < 0.001,Fig.3).Also, cases are better described with respect to compliance with guidelines: in the first period possible compliance could not be determined in 15% of the cases, in the second part only 2.4% (2 cases). For obvious reasons, these differences between periods are simply because guidelines were not yet issued when the case occurred in most of the cases from the first period. However, despite the better compliance, the total number of case reports published yearly has not decreased. In several cases of SH occurring despite compliance with guidelines, the reason was apparently the combination of multiple causes, e.g. renal insufficiency and drugs dependent on renal function, such as LMWH. It must also be pointed out, that in 24 patients (15%), no risk factor was reported. Thus, although guidelines are a safeguard to minimise the risk of SH, they are no guarantee for it not to happen.

Annual number of published case reports, comparing the period 1994–2004 vs. 2005–2015 with regard to adherence to guidelines. see text for further explanation.

3.7.2 The clinical scenarios change rapidly and guidelines may become outdated

The clinical scenarios around surgical patients become more and more complicated. More elderly undergo surgery; the number of patients ≥80 years undergoing major surgery in Sweden increased by 30% between 1998 (earliest year recorded) and 2015, and even by 40% among those ≥85 years [164]. At the same time, new potent antihaemostatic drugs are continuously introduced, and they are prescribed to an increasing number of patients, especially among elderly. Thus, the number of Swedes aged ≥80 years, who are taking oral anticoagulant drugs almost trebled between 1994 and 2015, from 24% to 71% in men, and from 20% to 57% among women [164].

Of special interest are the novel (or non-AVK) oral anticoagulants, (NOACs).1 These are of two pharmacological classes, thrombin inhibitors, e.g. dabigatran, and factor Xa inhibitors, e.g. rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban. They are mainly prescribed for atrial fibrillation, and have to some extent replaced warfarin, but are also licensed for postoperative thromboprophylaxis after hip or knee arthroplasties (as alternatives to LMWH). There were three cases of post-CNB SH reported in patients treated with NOACs, in two cases rivaroxaban was implicated, and in one case dabigatran (see Section 3.3.3.3). In the period 2011–2015 NOACs were prescribed to around 20% (17–22% yearly) of the patients for Tpx after knee arthroplasty in Sweden [176]. Over all, NOACs have gained widespread popularity; after the release of the first NOAC (dabigatran) in Sweden in 2008 the total prescription of NOACs has gradually increased to 0.97% among the entire population in 2015; among elderly (≥80 y.o.) the corresponding figure is 5.8% [164]. At the same time, the prescription of warfarin has also increased, from 1.7% of the population in 2008 to 1.9% in 2015, and from 11% to 16% among elderly. Thus, the total prescription of oral anticoagulants (AVK and NOAC) in Sweden has increased by 75% from 2008 to 2015. Among elderly (≥80y.o.)the corresponding figure is 107%. With respect to platelet inhibitors in this age group, the prescription of ASA has decreased by 20%, while the prescription of the more potent ADP-receptor inhibitors (mainly clopidogrel) has increased by 86% (from 2.9% to 5.5%) between 2008 and 2015.

These data suggest that surgical patients with an elevated risk of bleeding have continuously increased in number during the last decades. Recent meta-analyses document that CNBs reduce major cardio-respiratory complications and postoperative morbidity and mortality, either alone [181,182], or in combination with general anaesthesia, for postoperative pain relief [183], and reduce the need for postoperative intensive care [184], when compared to general anaesthesia alone. Despite the risk of spinal haematomas, the overall cost-benefit is therefore overwhelmingly favourable for spinal, epidural, and combined spinal–epidural analgesia techniques, provided that the medical teams make thorough risk/benefit analysis in every individual case with elevated bleeding risk. The Nordic guidelines [8,185] attempt to give clinicians advice in this delicate balance.

The pharmacokinetic properties of drugs are often based on studies on young, healthy men, but may differ markedly in elderly patients in the perioperative period, making it difficult to determine the safe interval in individual cases. These patients, often with chronic medication with anti-haemostatic drugs, and, in addition, requiring postoperative thromboprophylaxis, are generally those who benefit most from a CNB [8,185]. The rapidly changing clinical scenarios with respect to new drugs, elderly patients, major surgery, and rapid postoperative rehabilitation programmes, require frequent updating of existing guidelines.

Most guidelines are now updated with recommendations for the perioperative management of NOACs and the new platelet inhibitors. The recommendation for NOACs is generally 2 days’ discontinuation before CNB and catheter manipulations, with an extended interval with dabigatran in patients with renal impairment, and 5–7 days for ADP-receptor blockers. However, the latest ASRA/ESRA guidelines recommend longer intervals in high risk procedures (see Section 3.4.1.1) [159].

4 Conclusions

There has been a transition from a male to a female dominance among patients suffering from a post-CNB spinal haematoma, in particular among elderly women, and even more so in elderly women undergoing knee replacement.

The annual number of published case reports of post-CNB spinal haematoma has increased by a 3-fold after 1994, and has been kept on a steady level up until 2015.

Guidelines issued around the turn of the century have not been followed by a reduced number of published case reports, although adherence to the guidelines has increased during the last decade (2005–2015). The complex and rapidly changing clinical scenarios, especially introductions of new antihaemostatic drugs, require frequent updates of such guidelines.

Heparins (UFH and LMWH) are major risk factors for developing SH. This is even more apparent in patients with renal impairment, which may be one of several reasons for the high number of cases occurring despite strict adherence to the guidelines.

“Bloody tap” at the introduction of a neuraxial needle or catheter is a major risk factor, but multiple attempts to reach the spinal canal do not seem to increase the risk of an SH.

5 Implications

This review demonstrates that spinal haematoma caused by neuraxial block is still a clinical problem worldwide, especially in elderly women, despite guidelines issued in order to prevent this complication in several countries during the last 20 years. At the same time, neuraxial anaesthesia reduces postoperative morbidity and mortality, as well as the need for postoperative intensive care, when compared to general anaesthesia alone. The overall cost-benefit is therefore favourable for these techniques, provided that clinicians make careful risk/benefit analyses in every individual case, and follow updated guidelines on optimal management of neuraxial blocks.

DOIs of original articles: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.01.011, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2016.11.009.

-

Funding: No funding or financial support has been received.

-

Ethical issues: None.

-

Conflict of interest: No conflict of interests is declared.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Drs. Vibeke Moen, Josué Avecillas-Chasin, and Daniel Pöpping for providing me with extended material from their articles, and to Professor Harald Breivik for valuable comments.

References

[1] Moen V, Dahlgren N, Irestedt L. Severe neurological complications after central neuraxial blockades in Sweden 1990–99. Anesthesiology 2004;101:950–9.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Landoni G, Isella F, Greco M, Zangrillo A, Royse CF. Benefits and risks of epidural analgesia in cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 2015;115:25–32.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Schmidt A, Nolte H. Subdural and epidural hematomas following epidural anesthesia. A literature review. Anaesthesist 1992;41:276–84.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Vandermeulen E, van Aken H, Vermylen J. Anticoagulants and spinal–epidural anesthesia. Anesth Analg 1994;79:1165–77.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Wulf H. Epidural anaesthesia and spinal haematoma. Can J Anaesth 1996;43:1260–71.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Horlocker TT, Heit JA. Low molecular weight heparin: biochemistry, pharmacology, perioperative prophylaxis regimens, and guidelines for regional anesthetic management. Anesth Analg 1997;85:874–85.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Tryba M. European practice guidelines: thromboembolism prophylaxis and regional anaesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med 1998;23:178–82.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Breivik H, Bang U, Jalonen J, Vigfússon G, Alahuhta S, Lagerkranser M. Nordic guidelines for neuraxial blocks in disturbed haemostasis from the Scandinavian Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2010;54:16–41.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Gogarten W, Vandermeulen E, Van Aken H, Kozek S, Llau JV, Samama CM. Regional anaesthesia and antithrombotic agents: recommendations of the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesth 2010;27:999–1015.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Butterworth JF. Case reports: unstylish but still useful sources of clinical information (editorial). Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009;34:187–8.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Bent U, Gniffke S, Reinbold WD. Epidurales hämatom nach single shotepiduralanästhesie. An epidural haematoma following single shot epidural anesthesia. Anaesthesist 1994;43:245–8.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Ganjoo P, Singh AK, Mishra VK, Singh PK, Bannerjee D. Postblock epidural haematoma causing paraplegia. Reg Anesth 1994;19:62–5.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Gerlif C, Myrtue GS. Atypical site of epidural hematoma – after epidural analgesia. Ugeskr Laeger 1994;156:7231–2.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Nicholson A. Painless epidural haematoma. Anaesth Intensive Care 1994;22:607–10.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Bougher RJ, Ramage D. Spinal subdural haematoma following combined spinal–epidural anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care 1995;23:111–3.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Dahlgren N, Törnebrandt K. Neurological complications after anaesthesia. A follow-up of 18000 spinal and epidural anaesthetics performed over three years. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1995;39:872–80.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Hartigan JD. Dangerous sequelae of epidural anaesthesia in geriatrics. Nebr Med J 1995;80:80–2.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Morisaki H, Doi J, Ochiai R, Takeda J, Fukushima K. Epidural hematoma after epidural anesthesia in a patient with hepatic cirrhosis. Anesth Analg 1995;80:1033–5.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Rainov NG, Heidecke V, Burkert WL. Spinal epidural hematoma. Report of a case and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev 1995;18:53–60.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Sternlo JE, Hybbinette CH. Spinal subdural bleeding after attempted epidural and subsequent spinal anaesthesia in a patient on thromboprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1995;39: 557–9.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Badenhorst CH. Epidural hematoma after epidural pain control and concomitant postoperative anticoagulation. Reg Anesth 1996;21:272–3.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Barontini F, Conti P, Marello G, Maurri S. Major neurological sequelae of lumbar epidural anesthesia. Report of three cases. Ital J Neurol Sci 1996;17:333–9.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Bartoli F, Barbagli R, Rucci F. Anterior epidural haematoma following sub-arachnoid block. Can J Anaesth 1996;43:94.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Hynson JM, Katz JA, Bueff HU. Epidural hematoma associated with enoxaparin. Anesth Analg 1996;82:1072–5.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Likar R, Mathiaschitz K, Spendel M, Krumpholz R, Martin E. Akutes spinales subduralhämatom nach spinalaästesiversuch. Anaesthesist 1996;45:66–9.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Martinez-Palli G, Sala-Blanch X, Salvadó E, Acosta M, Nalda MA. Epidural hematoma after epidural anesthesia in a patient with peripheral vascular disease. Case report. Reg Anesth 1996;21:342–6.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Pryle BJ, Carter JA, Cadoux-Hudson T. Delayed paraplegia following spinal anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 1996;51:263–5.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Rabito SF, Ahmed S, Feinstein L, Winnie AP. Intrathecal bleeding after the intraoperative use of heparin and urokinase during continuous spinal anesthesia. Anesth Analg 1996;82:409–11.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Allen D, Dahlgren N, Nellgård B. Risks and recommendation in Bechterew disease. Paraparesis after epidural anesthesia. Lakartidningen 1997;94:4771–4.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Aromaa U, Lahdensuu M, Cozanitis DA. Severe complications associated with epidural and spinal anaesthesia in Finland 1987–1993. A study based on patient insurance claims. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1997;41:445–52.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Gerancher JC, Waterer R, Middleton J. Transient paraparesis after postdural puncture spinal hematoma in a patient receiving ketorolac. Anesthesiology 1997;86:490–4.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Harvey SC, Roland PJ, Curé JK, Cuddy BC, O’Neil MG. Spinal epidural hematoma detected by lumbar epidural puncture. Anesth Analg 1997;84:1136–9.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Porterfield WR, Wu CL. Epidural hematoma in an ambulatory surgical patient. J Clin Anesth 1997;9:74–7.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Wood GG, Jacka MJ. Spinal hematoma following spinal anesthesia in a patient with spina bifida occulta. Anesthesiology 1997;87:983–4.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Cabitza P, Parrini M. Slow-onset subdural hematoma, evolving into paraplegia, after attempted spinal anesthesia – a case report. Acta Orthop Scand 1998;69:650–2.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Christensen PH, Johnstad B. Alvorlig neurologisk sekvele i tilslutning til spinal- og epiduralbedövelse. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1998;118:244–6.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Helland S, Berg-Johnsen J, Heier T, Nakstad PH. Intraspinal blødning etter torakal epidural smertebehandling. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen 1998;118:241–4.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Skilton RWH, Justice W. Epidural haematoma following anticoagulant treatment in a patient with an indwelling epidural catheter. Anaesthesia 1998;53:691–5.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Wildförster U, Schregel W, Harders A. Delayed lumbar epidural hematoma. Discussion of the risk factors: hypertension, anticoagulation and spinal anesthesia. Anästhesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmertzther 1998;33:517–20.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Woolson ST, Robinson RK, Khan NQ, Rogers BS, Maloney JM. Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis for knee replacement. Am J Orthop 1998;27:299–304.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Basta M, Sloan P. Epidural hematoma following epidural catheter placement in a patient with chronic renal failure. Can J Anesth 1999;46:271–4.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Domenicucci M, Ramieri A, Ciapetta P, Delfini R. Nontraumatic acute spinal subdural hematoma. Report of five cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg (Spine 1) 1999;91:65–73.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Goyal A, Dua R, Singh D, Kumar S. Spinal subarachnoid haematoma following lumbar puncture. Neurol India 1999;47:339–40.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Pedraza Gutiérrez S, Coll Masfarré S, Castañ o Duque CH, Suescún M, Rovira Cañ ellas A. Hyperacute spinal subdural haematoma as a complication of lumbar spinal anaesthesia: MRI. Neuroradiology 1999;41:910–4.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Yin B, Barratt SM, Power I, Percy J. Epidural haematoma after removal of an epidural catheter in a patient receiving high-dose enoxaparin. Br J Anaesth 1999;82:288–90.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Yuen TST, Kua JSW, Tan IKS. Spinal haematoma following epidural anaesthesia in a patient with eclampsia. Anaesthesia 1999;54:350–71.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Osmani O, Afeiche N, Lakkis S. Paraplegia after epidural anesthesia in a patient with peripheral vascular disease: case report and review of the literature with a description of an original technique for hematoma evacuation. J Spinal Disord 2000;13:85–7.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Ousname ML, Fleyfel M, Vallet B. Epidural hematoma after catheter removal. Anesth Analg 2000;90:1246–51.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Sandhu H, Morley-Foster P, Spadafora S. Epidural hematoma following epidural analgesia in a patient receiving unfractionated heparin for thromboprophylaxis. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2000;25:72–5.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Stroud CC, Markel D, Sidhu K. Complete paraplegia as a result of regional anesthesia. J Arthroplasty 2000;15:1064–7.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Esler MD, Durbridge J, Kirby S. Epidural haematoma after dural puncture in a parturient with neurofibromatosis. Br J Anaesth 2001;87:932–4.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Ghaly RF. Recovery after high-dose methylprednisolone and delayed evacuation. J Neurosurg Anesth 2001;13:323–8.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Litz RJ, Hübler M, Koch T, Albrecht M. Spinal–epidural hematoma following epidural anesthesia in the presence of antiplatelet and heparin therapy. Anesthesiology 2001;95:1031–3.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Pánek V. Epidural haematoma and timing of heparin prophylaxis. Anaesthesia 2001;56:811–2.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Siddiqui MN, Ranasinghe JS, Siddiqui S. Epidural hematoma after epidural steroid injection: a possible association with use of pentosan polysulfate sodium. Anesthesiology 2001;95:1307.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Gilbert A, Owens BD, Mulroy MF. Epidural hematoma after outpatient epidural anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2002;94:77–8.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Herbstreit F, Kienbaum P, Merguet P, Peters J. Conservative treatment of paraplegia after removal of an epidural catheter during low-molecular-weight heparin treatment. Anesthesiology 2002;97:733.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Inoue K, Yokoyama M, Nakatsuka H, Goto K. Spontaneous resolution of epidural hematoma after continuous epidural analgesia in a patient without bleeding tendency. Anesthesiology 2002;97:735–7.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Jaeger M, Rickels E, Schmidt A, Samii M, Blömer U. Lumbar ependymoma presenting with paraplegia following attempted spinal anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 2002;88:438–40.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Pay LL, Chiu JW, Thomas E. Postoperative epidural hematoma or cerebrovascular accident? A dilemma in differential diagnosis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2002;46:217–20.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Persson J, Flisberg P, Lundberg J. Thoracic epidural anaesthesia and epidural haematoma. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2002;46:1171–4.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Reitman CA, Watters W. Subdural hematoma after cervical epidural steroid injection. Spine 2002:E174–6.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Stoll A, Sanchez M. Epidural hematoma after epidural block: implications for its use in pain management. Surg Neurol 2002;57:235–40.Search in Google Scholar

[64] Drogosch E, Perneczky A, Berhardt A. Koinzidenz eines epiduralen Hämatoms und epiduralen Metastasengewbes bei thorakaler Epiduralanästhesie. Anaesthesist 2003;52:925–8.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Lee BB. Neuraxial complications after spinal and epidural anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2003;47:371–3.Search in Google Scholar

[66] Muir JJ, Church EJ, Weinmeister KP. Epidural hematoma associated with dextran infusion. South Med J 2003;96:811–4.Search in Google Scholar

[67] Otsu I, Merrill D. Epidural hematoma after epidural anesthesia: a case report of non-surgical management. Acute Pain 2003;4:117–20.Search in Google Scholar

[68] Rodi Z, Straus I, Denic K, Deletis V, Vodusek DB. Transient paraplegia revealed by intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring: was it caused by the epidural anesthetic or an epidural hematoma. Anesth Analg 2003;96:1785–8.Search in Google Scholar

[69] Sidiropoulou T, Pompeo E, Bozzao A, Lunardi P, Dauri M. Epidural hematoma after thoracic epidural catheter removal in the absence of risk factors. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2003.Search in Google Scholar

[70] Zink M, Rath M, Waltensdorfer A, Engler J, Rumpold-Seitinger G, Toller W, Reinhardt F. Unilateral presentation of a large epidural hematoma. Anesthesiology 2003;98:1032–3.Search in Google Scholar

[71] Chan L, Bailin MT. Spinal epidural hematoma following central neuraxial blockade and subcutaneous enoxaparin: a case report. J Clin Anesth 2004;16:382–5.Search in Google Scholar

[72] Cullen DJ, Bogdanov E, Htut N. Spinal epidural hematoma occurrence in the absence of known risk factors: a case series. J Clin Anesth 2004;16:376–81.Search in Google Scholar

[73] Gottschalk A, Bischoff P, Lamszus K, Strandl T. Epidural hematoma after spinal anesthesia in a patient with undiagnosed epidural lymphoma. Anesth Analg 2004:1181–3.Search in Google Scholar

[74] Litz RJ, Gottschlich B, Stehr SN. Spinal epidural hematoma after spinal anesthesia in a patient treated with clopidogrel and enoxaparin. Anesthesiology 2004;101:1467–70.Search in Google Scholar

[75] Rosen DA, Hawkinberry II DW, Rosen KR, Gustafson RA, Hogg JP, Broadman LM. An epidural hematoma in an adolescent patient after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg 2004;98:966–9.Search in Google Scholar

[76] Schwarz SKW, Wong CL, McDonald WN. Spontaneous recovery from a spinal epidural hematoma with atypical presentation in a nonagenarian. Can J Anesth 2004;51:557–61.Search in Google Scholar

[77] Sharma S, Kapoor MC, Sharma VK, Dubey AK. Epidural hematoma complicating high thoracic epidural catheter placement intended for cardiac surgery. J Cardiovasc Anesth 2004;18:759–62.Search in Google Scholar

[78] Özgen S, Baykan N, Dogan IV, Konya D, Necmettin P. Cauda equina syndrome after induction of spinal anesthesia. Neurosurg Focus 2004;16:24–7.Search in Google Scholar

[79] Ain RJ, Vance MB. Epidural hematoma after epidural steroid injection in a patient withholding enoxaparin per guidelines. Anesthesiology 2005;102:701–3.Search in Google Scholar

[80] Hyderally HA. Epidural hematoma unrelated to combined spinal–epidural anesthesia in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis receiving aspirin after total hip replacement. Anesth Analg 2005;100:882–3.Search in Google Scholar

[81] Miyazaki M, Takasita M, Matsumoto H, Sonoda H, Tsumura H, Toriso T. Spinal epidural hematoma after removal of an epidural catheter. J Spinal Disord Tech 2005;18:547–51.Search in Google Scholar

[82] Robins K, Saravanan S, Watkins EJ. Ankylosing spondylitis and epidural haematoma. Anaesthesia 2005;60:617–32.Search in Google Scholar

[83] Afzal A, Hawkins F, Rosenquist RW. Epidural hematoma in a patient receiving epidural analgesia and LMWH after total-knee arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2006;31:480.Search in Google Scholar

[84] Agustin E, Aldecoa C, Rico-Feijoo J, Gómes-Herreras JI. Delayed sub-arachnoid hematoma after continuous epidural anesthesia in a patient without risk factors: good outcome after late laminectomy. Anesth Analg 2006;103:1599–600.Search in Google Scholar

[85] Chan MY, Lindsay DA. Subdural spinal hematoma after epidural anesthesia in a patient with spinal canal stenosis. Anaesth Intensive Care 2006;34: 269–75.Search in Google Scholar

[86] Dinsmore J, Nightingale J, Baker S. Delayed diagnosis of an epidural haematoma with a working epidural in situ. Anaesthesia 2006;61:912–3.Search in Google Scholar

[87] SreeHarsha CK, Rajasekaran S, Dhanasekara R. Spontaneous complete recovery of paraplegia caused by epidural hematoma complicating epidural anesthesia: a case report and review of the literature. Spinal Cord 2006;44:514–7.Search in Google Scholar

[88] Tam NLK, Pac-Soo C, Pretorius PM. Epidural haematoma after a combined spinal–epidural anaesthetic in a patient treated with clopidogrel and dalteparin. Br J Anaesth 2006;96:262–5.Search in Google Scholar

[89] Boco T, Deutch H. Delayed symptomatic presentation of epidural hematoma after epidural catheter anesthesia: case report. Spine 2007;32:E649–51.Search in Google Scholar

[90] Flisberg P, Friberg H. Epidural anaesthesia complications – early warning signs. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2007;51:264–5.Search in Google Scholar

[91] Magalhaes E, Goveia CS, de Araujo Ladeira LC, de Queiroz LES. Hematoma after epidural anesthesia: conservative treatment. Case report. Rev Bras Anestesiol 2007;57:182–7.Search in Google Scholar

[92] Park J-H, Shin K-M, Hong S-J, Kim I-S, Nam S-K. Subacute spinal subarachnoid hematoma after spinal anesthesia that causes mild neurologic deterioration. Anesthesiology 2007;107:846–8.Search in Google Scholar

[93] Segabinazzi D, Brescianini BC, Schneider FG, Mendes FF. Conservative treatment of hematoma after spinal anesthesia: case report and literature review. Rev Bras Anestesiol 2007;57:188–94.Search in Google Scholar

[94] Varitimidis SE, Paterakis K, Dailiana ZH, Hanres M, Georgopoulou S. Epidural hematoma secondary to removal of an epidural catheter after a total knee replacement. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:2048–50.Search in Google Scholar

[95] Davignon KR, Maslow A, Chaudrey A, Ng T, Shore-Lesserson L, Rosenblatt MA. Epidural hematoma: when is it safe to heparinize after the removal of an epidural catheter? J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2008;5:774–8.Search in Google Scholar

[96] Hans GA, Senard M, Ledoux D, Grayet B, Scholtes F, Creemers E, Lamy ML. Cerebral subarachnoid blood migration consecutive to a lumbar haematoma after spinal anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2008;52:1021–3.Search in Google Scholar

[97] Kaneda T, Urimoto G, Suzuki T. Spinal epidural hematoma following epidural catheter removal during antiplatelet therapy with cilostazol. J Anaesth 2008;22:290–3.Search in Google Scholar

[98] Lam DH. Subarachnoid haematoma after spinal anaesthesia mimicking transient radicular irritation: a case report and review. Anaesthesia 2008;63:423–7.Search in Google Scholar

[99] Nitz P, Laubenthal H, Haller S, Mumme A, Meiser A. Symptomatic epidural haematoma under therapeutic dose heparin: occurrence after removal of a peridural catheter. Anästhesist 2008;57:57–60.Search in Google Scholar

[100] Pöpping DM, Zahn PK, Van Aken HK, Dasch B, Boche R, Pogatzki-Zahn EM. Effectiveness and safety of postoperative pain management: a survey of 18925 consecutive patients between 1998 and 2006. Br J Anaesth 2008;101:832–40.Search in Google Scholar

[101] Singh DK, Chauhan M, Gupta V, Chopra S, Bagaria HR. Spinal subdural hematoma: a rare complication of spinal anesthesia: a case report. Turk Neurosurg 2008;18:324–6.Search in Google Scholar

[102] Bindelglass DF, Rosenblum DS. Neuraxial hematoma and paralysis after enoxaparin administration 3 days after attempted spinal anesthesia for total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2009. October 16 [Epub ahead of print].Search in Google Scholar

[103] Eipe N, Restrepo-Garces CE, Aviv RI, Awad IT. Spinal epidural hematoma following epidural catheter removal in a paraplegic patient. J Clin Anesth 2009;21:525–8.Search in Google Scholar

[104] Elwood D, Koo C. Intraspinal hematoma following neuraxial anesthesia and low-molecular-weight heparin in two patients: risks and benefits of anticoagulation. PM&R 2009;1:389–96.Search in Google Scholar

[105] Fakouri B, Srinivas S, Magaji S, Kunsky A, Cacciola F. Spinal epidural hematoma after insertion of a thoracic epidural catheter in the absence of coagulation disorders – a call for raised awareness. Neurol India 2009;57:512–3.Search in Google Scholar

[106] Kasodekar SV, Goldszmidt E, Davies SR. Atypical presentation of an epidural hematoma in a patient receiving aspirin and low molecular weight heparin. Was epidural analgesia the right choice? J Clin Anesth 2009;21:595–8.Search in Google Scholar

[107] Moussallem CD, El-Yahchouchi CA, Charbel AC, Nohra G. Late spinal subdural haematoma after spinal anaesthesia for total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg 2009;91:1531–2.Search in Google Scholar

[108] Rocchi R, Lombardi C, Marradi I, Di Paolo M, Cerase A. Intracranial and intraspinal hemorrhage following spinal anesthesia. Neurol Sci 2009;30:393–6.Search in Google Scholar

[109] Ulivieri S, Olivieri G. Spinal epidural hematoma following epidural anesthesia. Case report. G Chir 2009;30:51–2.Search in Google Scholar

[110] Xu R, Bydon M, Gokaslan ZL, Wolinsky J-P, Witham TF, Bydon A. Epidural steroid injection resulting in epidural hematoma in a patient despite strict adherence to anticoagulation guidelines. J Neurosurg Spine 2009;11:358–64.Search in Google Scholar

[111] Yoo HS, Park SW, Han JH, Chung JY, Yi JW, Kang JM, Lee BJ, Kim DO. Paraplegia caused by an epidural hematoma in a patient with unrecognized chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura following an epidural steroid injection. Spine 2009;34:E376–9.Search in Google Scholar

[112] Zeynenoglu P, Gulsen S, Camkiran A, Ulu EMK, Aslim E, Pirat A. An epidural hematoma after epidural anesthesia for endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2009;23:580–2.Search in Google Scholar

[113] Cerroni A, Carvalho JA, Tancredi A, Volpe AR, Floccari A. Acute bleeding after spinal anaesthesia due to puncture of unsuspected lumbar myxopependimoma. Eur J Anaesth 2010;27:1072–4.Search in Google Scholar

[114] Guffey PJ, McKay R, McKay RE. Epidural hematoma nine days after removal of a labor epidural catheter. Anesth Analg 2010;111:992–5.Search in Google Scholar

[115] Han IS, Chung EY, Hahn Y-J. Spinal epidural hematoma after epidural anesthesia in a patient receiving enoxaparin – a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol 2010;59:119–22.Search in Google Scholar

[116] Koyama S, Tomimatsu T, Kanagawa T, Sawada K, Tsutsui T, Kimura T, Chang YS, Wasada K, Imai S, Murata Y. Spinal subarachnoid hematoma following spinal anesthesia in a patient with HELLP syndrome. Int J Obstet Anesth 2010;19:87–91.Search in Google Scholar

[117] Li S-L, Wang D-X, Ma D. Epidural hematoma after neuraxial blockade: a retrospective report from China. Anesth Analg 2010;111:1322–4.Search in Google Scholar

[118] Perrini P, Pieri F, Montemurro N, Tiezzi G, Parenti GF. Thoracic epidural haematoma after epidural anaesthesia. Neurol Sci 2010;31:87–8.Search in Google Scholar

[119] Bang J, Kim JU, Lee YM, Joh J, An E-H, Lee L-Y, Kim JY, Choi I-C. Spinal epidural hematoma related to an epidural catheter in a cardiac surgery patient – a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol 2011;61:524–7.Search in Google Scholar

[120] Chung J-H, Hwang J, Cha S-C, Jung T, Woo SC. Epidural hematoma occurred by massive bleeding intraoperatively in caesarean section after combined spinal epidural anesthesia – a case report. Korean J Anesthesiol 2011;61:336–40.Search in Google Scholar

[121] Goswami D, Das J, Deuri A, Deka AK. Epidural haematoma: rare complication after spinal while intending epidural anaesthesia with long-term follow-up after conservative treatment. Indian J Anaesth 2011;55:71–3.Search in Google Scholar

[122] Karakosta A, Kyrallidou A, Chapsa C, Pouliou A. Acute spinal anaesthesia treated conservatively: case report. Eur J Anaesth 2011;28:388–90.Search in Google Scholar

[123] Seouw K, Drummond KJ. Subdural spinal haematoma after spinal anaesthesia in a patient taking aspirin. J Clin Neurosci 2011;18:1713–5.Search in Google Scholar

[124] Shantanna H, Park J. Acute epidural haematoma following epidural steroid injection in a patient with spinal stenosis. Anaesthesia 2011;66:837–9.Search in Google Scholar

[125] Souza RL, Andrade LOF, Silva JB, Silva LAC. Neuraxial hematoma after epidural anesthesia. Is it possible to prevent or detect it? Report of two cases. Rev Bras Anesthesiol 2011;61:218–24.Search in Google Scholar

[126] Wajima Z, Aida S. Does hyperbaric oxygen have positive effect on neurological recovery in spinal–epidural haematoma? A case report. Br J Anaesth 2011;106:785–91.Search in Google Scholar

[127] Barbara DW, Smith BC, Arendt KW. Images in anaesthesiology: spinal subdural hematoma after labor epidural placement. Anesthesiology 2012;117:178.Search in Google Scholar

[128] Chung JY, Han JH, Kang JM, Lee BJ. Paraplegia after epidural steroid injection. Anaesth Intensive Care 2012;40:1074–6.Search in Google Scholar

[129] Luo F, Cai XJ, Li ZY. Subacute spinal subarachnoid hematoma following combined spinal–epidural anesthesia treated conservatively: a case report. J Clin Anesth 2012;24:519–20.Search in Google Scholar

[130] Madhugiri VS, Singh M, Sasidharan GM, Kumar VRR. Remote spinal epidural haematoma after spinal anaesthesia presenting with a ‘spinal lucid interval’. BMJ Case Rep 2012, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2012-007258. Published October 29.Search in Google Scholar

[131] Takawira N, Han RJ, Nguyen TQ, Gaines JD, Han TH. Spinal cord stimulator and epidural haematoma. BJA 2012;109:649–50.Search in Google Scholar

[132] Walters MA, Van de Velde M, Wilms G. Acute intrathecal haematoma following neuraxial anaesthesia: diagnostic delay after apparently normal radiological imaging. Int J Obstet Anesth 2012;21:181–5.Search in Google Scholar

[133] Volk T, Wolf A, Van Aken H, Bürkle H, Wielbalck A, Steinfeldt T. Incidence of spinal haematoma after epidural puncture: analysis from the German network for safety in regional anaesthesia. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2012;29:170–6.Search in Google Scholar

[134] Yao W, Wang X, Xu H, Luo A, Zhang C. Unilateral sensorimotor deficit caused by delayed lumbar epidural hematoma in a parturient after caesarean section under epidural anesthesia. J Anesth 2012;26:949–50.Search in Google Scholar

[135] Caputo AM, Gottfried ON, Nimjee SM, Brown CR, Michael KW, Richardson WJ. Spinal epidural hematoma following epidural steroid injection in a patient treated with dabigatran. JBJS Case Connect 2013;3:e64.Search in Google Scholar

[136] Jeon SB, Ham T-I, Kang M-S, Shim H-Y, Park SL. Spinal subarachnoid hematoma after spinal anesthesia. Korean J Anesthesiol 2013;64:388–9.Search in Google Scholar

[137] Ladha A, Alam A, Idestrup C, Sawyer J, Choi S. Spinal haematoma after removal of a thoracic epidural catheter in a patient with coagulopathy resulting from unexpected vitamin K deficiency. Anaesthesia 2013;68:856–60.Search in Google Scholar

[138] Buvanedran A, Young AC. Spinal epidural hematoma after spinal cord stimulator trial lead placement in a patient taking aspirin. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2014;39:70–2.Search in Google Scholar

[139] Chang Chien GC, McCormick Z, Araujo M, Candido KD. The potential contributing effect of ketorolac and fluoxetine to a spinal hematoma following interlaminar epidural steroid injection: a case report and narrative review. Pain Phys 2014;17:E385–95.Search in Google Scholar

[140] Doctor JR, Ranganathan P, Divatia JV. Paraplegia following epidural analgesia: a potentially avoidable cause? Saudi J Anaesth 2014;8:284–6.Search in Google Scholar

[141] Feltracco P, Galligioni H, Barbieri S, Ori C. Transient paraplegia after epidural catheter removal during low molecular heparin prophylaxis. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2014;31:172–80.Search in Google Scholar

[142] Giberson CE, Barbosa J, Brooks ES, McGlothlen GL, Grigsby EJ, Kohut JJ, Wolbers LL, Poree LR. Epidural hematomas after removal of percutaneous spinal cord stimulator trial leads. Two case reports. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2014;39: 73–7.Search in Google Scholar

[143] Iwashita K, Shigematsu K, Higa K, Nitahar K. Spontaneous recovery of paraplegia caused by spinal epidural hematoma after removal of epidural catheter. Case Rep Anesthesiol 2014;2014:291728.Search in Google Scholar

[144] Kobayashi Y, Nakada J, Kuroda H, Sakakura N, Usami N, Sakao Y. Spinal epidural hematoma during anticoagulant therapy for pulmonary embolism: postoperative complications in a patient with lung cancer. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;(Suppl.):493–6.Search in Google Scholar

[145] Makris A, Gkliatis E, Diakomi M, Karmaniolou I, Mela A. Delayed spinal epidural hematoma following spinal anesthesia, far from needle puncture site. Spinal Cord 2014;52:S14–6.Search in Google Scholar

[146] Radcliff KE, Ong A, Parvizi J, Post Z, Orozco F. Rivaroxaban-induced epidural hematoma and cauda equina syndrome after total knee arthroplasty: a case report. Orthop Surg 2014;6:669–71.Search in Google Scholar

[147] Schroll J, Giurguis M, D’Mello A, Mroz T, Lin J, Farag E. Epidural hematoma with atypical presentation. A&A Case Rep 2014;2:75–7.Search in Google Scholar

[148] Wang J, Lau ME, Gulur P. Delayed spinal epidural hematoma after epidural catheter removal with reinitiation of warfarin. J Cardiovasc Anesth 2014;28:1566–9.Search in Google Scholar

[149] Avecillas-Chasin JM, Matias-Guiu JA, Gomez G, Saceda-Guiterrez J. A case of acute spinal intradural hematoma due to spinal anesthesia. J Acute Dis 2015;4:341–3.Search in Google Scholar

[150] Goyal LD, Kaur H, Singh A. Cauda equine syndrome after repeated spinal attempts: a case report and review of the literature. Saudi J Anaesth 2015;9:214–6.Search in Google Scholar

[151] Lee JK, Chae KW, Ju C, Kim BW. Acute cervical subdural hematoma with quadriparesis after cervical transforaminal epidural block. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2015;58:483–6.Search in Google Scholar

[152] Madhisetti KR, Mathew M, Pillai SS. Spinal epidural haematoma following rivaroxaban administration after total knee replacement. Indian J Anaesth 2015;59:519–21.Search in Google Scholar

[153] Singhal N, Sethi P, Agarwal S. Spinal subdural hematoma with cauda equina syndrome: a complication of spinal epidural anesthesia. J Anesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2015;31:244–5.Search in Google Scholar

[154] Staikou C, Stamelos M, Boutas I, Koutoulidis V. Undiagnosed vertebral hemangioma causing a lumbar compression fracture and epidural hematoma in a parturient undergoing vaginal delivery under epidural analgesia: a case report. Can J Anesth 2015;62:901–6.Search in Google Scholar

[155] Breschan C, Krumpholz R, Jost R, Likar R. Intraspinal haematoma following lumbar epidural anaesthesia in a neonate. Paediatr Anaesth 2001;11: 105–8.Search in Google Scholar

[156] Diyora B, Sharma A, Mamidanna R, Kamat L. Chronic cervicothoracic spinal subdural hematoma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2009;49:310–2.Search in Google Scholar

[157] Walker C, Ingram I, Edwrads D, Wood P. Use of thromboelastometry in the assessment of coagulation before epidural insertion after massive transfusion. Anaesthesia 2011;66:52–5.Search in Google Scholar

[158] van Veen JJ, Nokes TJ, Makris M. The risk of spinal haematoma following neuraxial anaesthesia or lumbar puncture in thrombocytopenic individuals. Br J Haematol 2010;148:15–25.Search in Google Scholar

[159] Narouze S, Benzon HT, Provenzano DA, Buvanendran A, De Andres J, Deer TR, Rauck R, Huntoon MA. Interventional spine and pain procedures in patients on antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications guidelines. From the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy, The American Academy of Pain Medicine, the International Neuromodulation Society, the North American Neuromodulation Society, and the World Institute of Pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2015;40:182–212.Search in Google Scholar

[160] Sprung J, Bourke DL, Grass J, Hammel J, Mascha E, Thomas P, Tubin I. Predicting the difficult neuraxial block: a prospective study. Anesth Analg 1999;89:384–9.Search in Google Scholar

[161] Horlocker TT, McGregor D, Matsushige DK, Schroeder DR, Besse JA. A retrospective review of 4767 consecutive spinal anesthetics: central nervous system complications. Anesth Analg 1997;84:578–84.Search in Google Scholar

[162] Samama CM, Albaladejo P, Benhamou D, Bertin-Maghit M, Bruder N, Doublet JD, Laversin S, Leclerc S, Marret E, Mismetti P, Samain E, Steib A. Venous thromboembolism prevention in surgery and obstetrics: clinical practice guidelines. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2006;23:95–116.Search in Google Scholar

[163] Pitkänen MT, Aromaa U, Cozanitis DA, Förster JG. Serious complications associated with spinal and epidural anaesthesia in Finland from 2000 to 2009. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2013;57:553–64.Search in Google Scholar