Abstract

Background and aims

Pain management is often inadequate in emergency departments (ED) despite the availability of effective analgesics. Interventions to change professional behavior may therefore help to improve the management of pain within the ED. We hypothesized that a 2-h educational intervention combining e-learning and simulation would result in improved pain treatment of ED patients with pain.

Methods

Data were collected at the ED of Horsens Regional Hospital during a 3-week study period in March 2015. Pain intensity (NRS, 0–10) and analgesic administration were recorded 24 h a day for all patients who were admitted to the ED during the first and third study weeks. Fifty-three ED nurses and 14 ED residents participated in the educational intervention, which took place in the second study week.

Results

In total, 247 of 796 patients had pain >3 on the NRS at the admission to the ED and were included in the data analysis. The theoretical knowledge of pain management among nurses and residents increased as assessed by a multiple choice test performed before and after the educational intervention (P = 0.001), but no change in clinical practice could be observed: The administration for analgesics [OR: 1.79 (0.97–3.33)] and for opioids [2.02 (0.79–5.18)] were similar before and after the educational intervention, as was the rate of clinically meaningful pain reduction (NRS >2) during the ED stay [OR: 0.81 (CI 0.45–1.44)].

Conclusions

Conduction of a 2-h educational intervention combining interactive case-based e-learning with simulation-based training in an ED setting was feasible with a high participation rate of nurses and residents. Their knowledge of pain management increased after completion of the program, but transfer of the new knowledge into clinical practice could not be found. Future research should explore the effects of repeated education of healthcare providers on pain management.

Implications

It is essential for nurses and residents in emergency departments to have the basic theoretical and practical skills to treat acute pain properly. A modern approach including e-learning and simulation lead to increased knowledge of acute pain management. Further studies are needed to show how this increased knowledge is transferred into clinical practice.

1 Introduction

Involving up to 60% of all patients, acute pain represents a considerable problem in the emergency department (ED) [1,2,3]. Undertreatment of acute pain has been extensively documented over the past decades and may have negative psychological and physiological consequences for the patients [4]. The reasons for undertreatment in the ED are numerous and involve some of the following: inadequate recognition and assessment of pain, narrow focus on the diagnosis and less attention of the painful condition, inadequate knowledge of and training in acute pain management of healthcare providers [5,6,7,8], and, in particular, the prejudice against prescription of opioid analgesics [9]. Consequently, one obvious strategy to reduce undertreatment is to educate ED nurses and residents in pain management.

Most educational research has focused on the implementation of new pain management guidelines and protocols, and only few studies have evaluated the effects of modern teaching methods such as e-learning and simulation [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Given the paucity of research in this field, we therefore decided to create an educational program (EP) combining interactive case-based electronic learning (e-learning) with simulation-based training. We hypothesized that (1) the EP would increase the knowledge of nurses and residents about acute pain management, and that (2) this increased knowledge would result in improved acute pain management in the ED.

2 Methods

2.1 The setting

The study was carried out in the ED of Horsens Regional Hospital (Denmark), which is one of five hospitals in the Central Region of Denmark receiving acute patients. The population of the Horsens area is approximately 208,000 out of a total population of 1,282,000 in the Central Denmark Region. The ED receives only patients referred from general practitioners and patients who have called 1-1-2 (a total of 34,000 patients annually). Patients are either treated and discharged immediately (e.g. in case of minor injuries) or hospitalized in the ED. Hospitalized ED patients are treated and discharged from the ED within 48 h or referred to other departments, if necessary (e.g. surgical or medical patients requiring specialized treatment). Acute patients with a clear tentative cardiologic diagnosis are not treated in the ED but are referred directly to the department of cardiology. At the time of the intervention, 58 nurses, 6 attending physicians, and 15 residents were employed in the ED. The attending physicians did not participate in the study. The educational intervention was conducted at the hospital in a separate department organized especially for simulation, education, and practical teaching.

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (2007-58-0010). We consulted the local ethics committee and they replied that ethical approval was not required for this study according to the Scientific Ethical Committees Act (section 14, subsection 1). Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients.

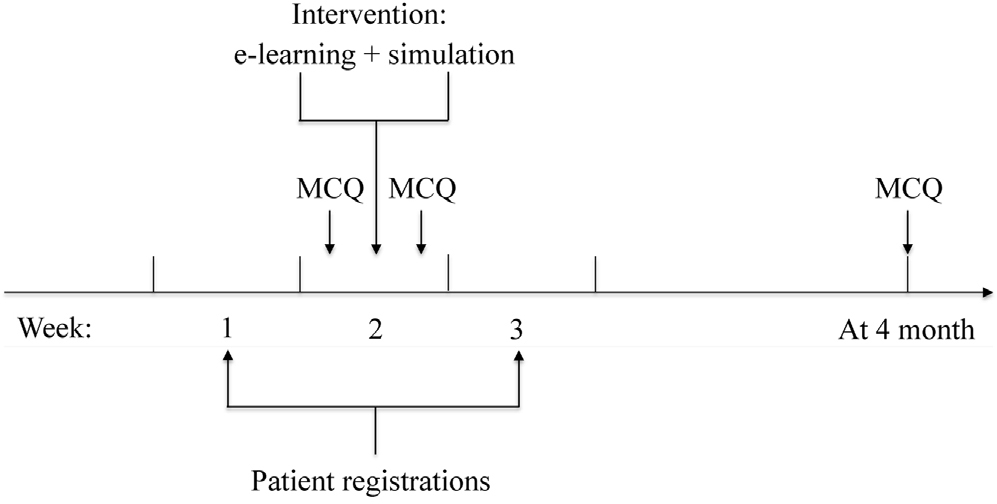

As presented in Fig. 1, the study period consisted of three consecutive weeks: Patient data were collected during the first and third weeks and the intervention was carried out in the second week.

Timeline of study period. MCQ: multiple choice questionnaire.

2.2 Patient data

Eight research assistants screened all consecutive patients for the presence of acute pain at the admission to the ED. This was done 24 h a day during the first and third study weeks, i.e., before and after the intervention. The pain was evaluated on an 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS, 0–10), where 0 indicated no pain and 10 indicated the worst imaginable pain. Patients with moderate to severe pain (NRS >3) at admission were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were as follows: severe trauma or medical illness causing activation of Trauma Team or Medical Emergency Team, age less than 15 years, or inability to rate pain intensity on the NRS. The research assistants also recorded pain intensity at discharge from the ED, i.e., hospital discharge, referral to other departments, or transfer to the operating room. If the patients had received analgesic treatment, the research assistants verified the drug’s name, dose, and administration form in the electronic patient journal. Pharmacological treatment options were paracetamol (Pinex®), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Burana®), tramadol (Dolol®) and morphine. The research assistants were trained thoroughly by the investigators prior to the study. Tentative diagnosis, occupancy rates, and time measures were subsequently extracted from the electronic patient journal. The research assistants were instructed not to interfere with the patient care or the nurses’ work, and they did not pass information on to any employee in the ED.

2.3 Educational program

During the second study week, the attending nurses and residents in the ED completed an EP consisting of interactive case-based e-learning and subsequent simulation training. One or two residents and 2–4 nurses typically participated in each EP session, which lasted approximately 2 h. The EP session was repeated 4 times daily for 5 continuous days in order to educate all nurses and residents in the ED.

Prior to the design of the EP, we identified barriers to sufficient pain management among nurses and residents during open discussions at staff meetings. The main barriers identified included inadequate knowledge about pain assessment and proper opioid dosing, a fear of inducing opioid-related adverse effects, and a general lack of attention to pain management. The nurses emphasized that the latter challenge occurred primarily during ED crowding. The authors formulated the content of the EP, and three pain management experts and two experts in simulation-based training from the Central Denmark Region carried out a critical revision. Graphic designers and experts in information technology managed the layout and technical composition of the e-learning module [17]. The e-learning module used an interactive case-based format and focused on pain assessment, administration and titration of commonly used analgesics, including opioids, and dose calculations based on patient age, weight, and comorbidities. (See Appendix or https://rm.plan2learn.dk/kursusvalg.aspx?id=32949&lang=en for details).

The simulation training session began with an initial briefing of the participants, continued with a simulation scenario, and ended with a debriefing [18]. The simulation was carried out by an actor instructed to play a trauma patient with an open fracture of the tibia brought to the ED by ambulance. The actor was instructed to complain strongly but realistic upon arrival and to decrease the pain level in parallel with intravenous morphine titration. Dynamic vital parameters (non-invasive blood pressure, pulse, and peripheral oxygen saturation) were visualized and made audible on a screen with loudspeakers. Vital parameters were changed according to participants’ actions and controlled with a wireless Simpad® by one of the two instructors. The first part of the simulation focused on practical pain management and sufficient dosing of intravenous morphine. The second part of the simulation trained participants in the handling of opioid-induced respiratory depression with manual ventilation, supplemental oxygen therapy, and antidote administration. The other instructor facilitated the scenario and focused on non-technical skills, such as communication, situational awareness, decision making, and task management. Finally, both instructors took part in the participant debriefing in order to clarify and strengthen insights and lessons from the simulation [19]. Both instructors were experienced and trained simulation instructors with at least 1 year of education in anesthesiology.

2.4 Effect of educational program on knowledge

A one-group pretest–posttest design was applied. We evaluated the effect of the EP with an electronic multiple choice questionnaire (MCQ) test carried out immediately before and after completing the EP. The evaluation was conducted in a controlled setting in a room adjacent to the simulation area. The MCQ test contained 20 questions reflecting the contents of the EP program. Each correctly answered question was given a score of 5 points, yielding a total maximum score of 100 points. To evaluate the level of long-term knowledge retention, we urged the participants to repeat the MCQ test 4 months after the EP via an electronic access.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The primary outcomes of this study were: (1) the change in theoretical knowledge in EP participants, as evaluated by MCQ scores before and after completing the EP, and (2) the effect of the intervention on patient care, evaluated as the proportion of patients receiving analgesics (yes/no). The sample size was calculated based on the results from another study which showed that the proportion of patients receiving analgesics would increase from 40% before the intervention to 60% after the educational intervention, with an alpha level of 0.05 and power of 0.90 [11]. To account for potential dropouts and the daily variation in ED visits, 14 days of observation were required to obtain a sufficient sample size of approximately 100 patients before and after the educational intervention. Secondary outcomes included opioid administration (yes/no) to patients with NRS >5 at hospital arrival, the cumulative morphine dose (oral equivalents), calculated as the sum of equivalent doses of perioral morphine, intravenous morphine, and tramadol [20], and the proportion of patients with clinically meaningful pain relief (NRS decrease ≥2) during ED stay.

All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 13.1 (StataCorp, TX, USA). Categorical data are reported as numbers (%) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) are reported for continuous skewed data, means with CI are given for normally distributed data, and odds ratios (OR) with CI when appropriate. A mixed model analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to investigate MCQ scores among EP participants as a response variable and time as an explanatory variable. The assumptions of the model were tested by investigating scatter plots of the residuals versus fitted values and quantile plots of the residuals. A multivariat logistic regression model was used in order to explore any potential difference in the rate of analgesics administered before and after the EP program. As this study was not a randomized controlled trial, analyses were adjusted for potential confounders, including pain severity at hospital arrival, age, sex, chief complaint (abdominal, medical, orthopedic), hospitalization (yes/no), weekend (yes/no), time of day (day, evening, night), and crowding defined as occupancy rate above 100% for patients hospitalized in the ED or waiting time more than 1 h for patients treated and discharged immediately. For all statistical analyses, missing data were not treated as expected values and a 5% limit of significance was applied.

3 Results

The results of the MCQ test are presented in Fig. 2. In total, 53 nurses and 14 residents participated in the EP (91% of all employees in the ED who were invited to participate), and they all answered the MCQ test before and after the educational intervention. At follow-up 4 months after the educational intervention, 34 nurses and 6 residents answered the MCQ test (55%). The median MCQ scores for EP completers were 45 (IQR 35–50) before the intervention, 80 (IQR 70–85) after the intervention, and 60 (IQR 55–75) at the 4-month follow-up. There was an overall statistically significant difference between the MCQ scores at the different time points (P = 0.0001). For pairwise comparisons, MCQ scores after the intervention were higher compared with baseline scores [difference: 32.7 (CI 29.6–35.7), P = 0.001], as were follow-up scores compared with baseline scores [difference: 19.1 (CI 14.9–23.3), P = 0.001].

Results from the multiple choice test at different time points. Score: The multiple choice questionnaire (MCQ) score: Each MCQ question correctly answered is given a score of 5, yielding a total maximal score of 100. Time: Before intervention (1), after intervention (2) and at follow-up (3). *For the null hypothesis of no overall difference between MCQ scores over time.

The patient flow is presented in Fig. 3. Based on our exclusion criteria, 222 patients were excluded from the analysis (107 patients before and 115 after the EP intervention). Excluded and included patients were similar in terms of age and sex. The prevalence of moderate to severe pain (NRS >3) at hospital arrival was 43.0% (CI 39.2–47.5). Patients discharged directly from the ED (n = 116) were treated for contusions (27%), distortions (21%), and fractures (20%). In ED hospitalized patients (n = 131), frequent tentative diagnoses were acute abdomen (27%), pyelonephritis or kidney stone (7%), and miscellaneous fractures (7%).

Flow chart for patients included in the study. NRS: numeric rating scale (0–10). EP: educational program.

After adjusting for potential confounders, there was no difference in the odds of receiving analgesics before and after the EP program (Table 1). Also, there were no differences before and after the EP program as regards opioid administration among patients with NRS >5 [OR 2.02 (0.79–5.18)], cumulative oral morphine [15 mg (IQR 10–30) vs. 15 mg (IQR 12.5–30), P = 0.5, and clinically meaningful pain relief [0.81 (CI 0.45–1.44)].

The odds of receiving analgesics before and after an educational intervention.

| n = 247 | Analgesics administered, % (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% Cl) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Crude | Adjusted[a] | |||

| Period | ||||

| Before EP | 136 | 35.3 (27.3–43.9) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| After EP | 111 | 42.3 (33.0–52.1) | 1.35 (0.80–2.25) | 1.79 (0.97–3.33) |

| Age, years | ||||

| ≤40 | 97 | 37.1 (27.5–47.5) | 0.73 (0.39–1.34) | 0.87 (0.43–1.80) |

| 41–59 | 76 | 44.7 (33.3–56.6) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| ≥60 | 74 | 33.8 (23.2–45.7) | 0.63 (0.33–1.22) | 0.53 (0.24–1.19) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 138 | 38.4 (30.3–47.1) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Male | 109 | 38.5 (29.4–48.3) | 1.01 (0.60–1.68) | 1.08 (0.59–1.96) |

| NRS at hospital arrival[b] | 247 | – | 1.41 (1.20–1.64) | 1.45 (1.22–1.73) |

| Chief complaint | ||||

| Abdominal | 77 | 57.1 (45.4–68.4) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Orthopedic | 135 | 25.9 (18.8–34.2) | 0.26 (0.15–0.48) | 0.31 (0.09–1.03) |

| Medical | 35 | 45.7 (28.8–63.4) | 0.63 (0.28–1.41) | 0.63 (0.25–1.57) |

| Hospitalized | ||||

| No | 116 | 23.3 (15.9–32.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 131 | 51.9 (43.0–60.7) | 3.56 (2.05–6.17) | 1.71 (0.53–5.45) |

| Crowding[c] | ||||

| No | 140 | 36.4 (28.5–45.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 107 | 41.1 (31.7–51.0) | 1.22 (0.73–2.04) | 0.85 (0.44–1.63) |

| Time of day (n = 238) | ||||

| 08:00–15:59 | 125 | 36.8 (28.4–45.9) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| 16:00–23:59 | 86 | 38.4 (28.1–49.5) | 1.07 (0.61–1.88) | 0.86 (0.43–1.73) |

| 00:00–07:59 | 27 | 40.7 (22.4–61.2) | 1.18 (0.50–2.77) | 0.49 (0.17–1.41) |

| Weekend (n = 246) | ||||

| No | 169 | 36.1 (28.9–43.8) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| Yes | 77 | 44.2 (32.8–55.9) | 1.40 (0.81–2.42) | 2.79 (1.37–5.65) |

-

EP, educational program

4 Discussion

In this prospective study, we confirmed our first hypothesis that nurses and residents increased their knowledge of pain management in the ED after completion of a 2-h EP combining interactive case-based e-learning with simulation-based training. However, the study did not allow us to confirm our second hypothesis that this knowledge was transferred into clinical practice.

Only a few other studies have investigated the impact of education on pain management in the ED, and none of them have used e-learning or simulation. Jackson found that educating 85 nurses in assessing, documenting, and treating pain in 302 elderly patients with hip fracture did not increase the rate of analgesia within 60 min [14]. Jones reported that 4 h of conventional education of resident physicians in pain management improved pain score reductions and global satisfaction in a mixed population of 126 patients with acute pain [12]. Sucov et al. examined the effect of conventional education at regular staff meetings and individual feedback on pain management of 1454 patients with isolated extremity fractures in three different EDs. An adjusting multiple logistic regression found that patients admitted to hospital after the intervention had 5 times the odds of receiving pain therapy compared with patients admitted before the intervention [16].

A systematic review from 2014 found that 42 studies on improvements of pain management in EDs varied widely in terms of intervention, study population, inclusion period, and outcomes reported. No firm conclusions could therefore be made as to which type of intervention had the highest impact on clinical practice. Most studies were multifaceted approaches involving implementation of pain scoring tools, pain management protocols, audits, nurse-administered analgesia and/or reminders of administering analgesia, with the majority of studies reporting some effect of intervention [13]. For instance, a study by Decosterd and colleagues found that analgesic treatment, patient satisfaction, and pain relief were higher in patients admitted to the ED after a full-scale multifaceted implementation of new pain management guidelines and thorough education of around 100 nurses and physicians in Switzerland [11]. However, the study was biased due to its single-center pre-/postinterventional design, convenient sampling of patient data by one non-blinded investigator, and no attempt to statistically adjust for potential confounders.

The strengths of our study were the immediate consecutive sampling of patient data carried out by different research assistants in order to reduce the risk of recall bias and missing data. The consecutive sampling of patient data also ensured a precise description of the prevalence and causes of pain in our ED.

Our study also had shortcomings. First, the fact that we did not use a multifaceted approach to improve acute pain management may partially explain that we were unable to detect any advances in clinical practice. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of an educational intervention and not how several adjustments and increased attention would impact clinical care. However, it cannot be ruled out that many nurses and residents considered their pain management as sufficient and therefore they did not change behavior. Second, the physical presence of research assistants during pain score collection might have increased the patients’ awareness of pain, resulting in increased reporting to healthcare providers. The reporting itself rather than the intervention could thus have changed the behavior of healthcare providers. Blinding of the research assistants and participating healthcare providers is difficult in educational studies, so the risk of potential changes in patient care as a result of study awareness could hardly have been avoided. We would have preferred to collect pain scores from an electronic source without the physical presence of research investigators in the ED. However, like in most other departments, documentation of pain assessment and reassessment after pain management are deficient and inconsistent in our department, making it less useful for clinical or scientific matters [21]. Third, as for most other studies trying to improve ED pain management, our study was not randomized [13]. Although we addressed this problem by controlling for several potential confounders, it can be argued that residual confounding remains an issue of concern. Cluster-randomization of different EDs to different interventions would be preferable, but results would remain difficult to interpret as EDs differ in terms of treatment strategies, organizational manners, and healthcare providers’ clinical competencies. Randomization of employees to different interventions within one ED is also difficult due to the risk of dilution bias. These difficulties seem to emphasize the challenges of educational science [13]. Fourth, it can be argued that our short period of inclusion decreased the chance of detecting any change of healthcare provider behavior. On the other hand, a longer period of inclusion would have increased the risk of bias due to secular variation and trends. Fifth, the evaluation of our EP was not a validated international test, and therefore these results should be cautiously interpreted. However, the test simply tried to see if there were any changes in knowledge and did not aim to investigate the magnitude of change or absolute levels of knowledge. Last, using an actor in the simulation training session could have affected our results if her way of expressing pain was unrealistic or somehow varied between sessions. However, as acute pain is a subjective sensation, a standardized scenario with a computerized simulation doll would have been less realistic.

5 Conclusions and implications

In conclusion, we conducted a 2-h educational intervention combining interactive case-based e-learning with simulation-based training in an ED setting. The participation rate of the invited nurses and residents was high, and their knowledge of pain management increased after completion of the program. However, we were unable to detect any transfer of their new knowledge into clinical practice. The negative findings reported in our study are multifactorial and imply that behavioral change among healthcare providers is complex, requiring repeated education, changes of attitudes towards pain management, and modification of daily practice adapted to the local environment as well as continuous support and follow-up by department management. Future studies should compare modern teaching such as our EP with conventional teaching methods in order to justify one approach over another. In addition, nurses and residents attitude towards pain management should be explored and addressed. Lastly, future research should explore how repeated education of healthcare providers would impact pain management and in this context, the patient perspective such as satisfaction and expectations should not be overlooked [22].

Highlights

A 2-h educational program increased the knowledge of pain management.

The increased knowledge was not transferred into clinical practice.

Acute pain is common in the emergency department.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.02.001.

-

Ethical issues: The local ethics committee of Central Denmark Region was consulted and they replied that ethical approval was not required for this study according to the Scientific Ethical Committees Act (section 14, subsection 1). Reference number 307/2014.

-

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

-

Funding: The Regional Postgraduate Medical Education Administration Office North and The Health Research Fund of Central Denmark Region funded this project.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Helle O. Andersen (Danish Pain Research Center, Aarhus, Denmark) for English language revision; Tina le Fevre and colleagues (Emergency Department, Horsens, Denmark) for great enthusiasm and practical help during pretrial preparation; Karina Houborg and Mette Poulsen (Department of Anesthesiology, Aarhus, Denmark) for critical revision of educational content.

References

[1] Berben SA, Schoonhoven L, Meijs TH, van Vugt AB, van Grunsven PM. Prevalence and relief of pain in trauma patients in emergency medical services. Clin J Pain 2011;27:587–92.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Todd KH, Ducharme J, Choiniere M, Crandall CS, Fosnocht DE, Homel P, Tanabe P. Pain in the emergency department: results of the pain and emergency medicine initiative (PEMI) multicenter study. J Pain 2007;8:460–6.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Cordell WH, Keene KK, Giles BK, Jones JB, Jones JH, Brizendine EJ. The high prevalence of pain in emergency medical care. Am J Emerg Med 2002;20:165–9.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Zohar Z, Eitan A, Halperin P, Stolero J, Hadid S, Shemer J, Zveibel FR. Pain relief in major trauma patients: an Israeli perspective. J Trauma 2001;51:767–72.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Rupp T, Delaney KA. Inadequate analgesia in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med 2004;43:494–503.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Pretorius A, Searle J, Marshall B. Barriers and enablers to emergency department nurses’ management of patients’ pain. Pain Manag Nurs 2015;16: 372–9.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Todd KH, Sloan EP, Chen C, Eder S, Wamstad K. Survey of pain etiology, management practices and patient satisfaction in two urban emergency departments. CJEM 2002;4:252–6.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Motov SM, Khan AN. Problems and barriers of pain management in the emergency department: are we ever going to get better. J Pain Res 2008;2:5–11.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Fosnocht DE, Swanson ER, Barton ED. Changing attitudes about pain and pain control in emergency medicine. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2005;23: 297–306.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Harting B, Abrams R, Hasler S, Odwazny R, McNutt R. Effects of training on a simulator of pain care on the quality of pain care for patients with cancer-related pain. Qual Manag Health Care 2008;17:200–3.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Decosterd I, Hugli O, Tamches E, Blanc C, Mouhsine E, Givel JC, Yersin B, Buclin T. Oligoanalgesia in the emergency department: short-term beneficial effects of an education program on acute pain. Ann Emerg Med 2007;50:462–71.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Jones JB. Assessment of pain management skills in emergency medicine residents: the role of a pain education program. J Emerg Med 1999;17: 349–54.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Sampson FC, Goodacre SW, O’Cathain A. Interventions to improve the management of pain in emergency departments: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Emerg Med J 2014;31:9–18.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Jackson SE. The efficacy of an educational intervention on documentation of pain management for the elderly patient with a hip fracture in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs 2010;36:10–5.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Jones JB. Assessment of pain management skills in emergency medicine residents: the role of a pain education program. J Emerg Med 1999;17:349–54.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Sucov A, Nathanson A, McCormick J, Proano L, Reinert SE, Jay G. Peer review and feedback can modify pain treatment patterns for Emergency Department patients with fractures. Am J Med Qual 2005;20:138–43.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Dror I, Schmidt P, O’Connor L. A cognitive perspective on technology enhanced learning in medical training: great opportunities, pitfalls and challenges. Med Teach 2011;33:291–6.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Rosen MA, Salas E, Wu TS, Silvestri S, Lazzara EH, Lyons R, Weaver SJ, King HB. Promoting teamwork: an event-based approach to simulationbased teamwork training for emergency medicine residents. Acad Emerg Med 2008;15:1190–8.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Rudolph JW, Simon R, Raemer DB, Eppich WJ. Debriefing as formative assessment: closing performance gaps in medical education. Acad Emerg Med 2008;15:1010–6.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Gammaitoni AR, Fine P, Alvarez N, McPherson ML, Bergmark S. Clinical application of opioid equianalgesic data. Clin J Pain 2003;19:286–97.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Dale J, Bjornsen LP. Assessment of pain in a Norwegian Emergency Department. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2015;23:86.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:42.Search in Google Scholar

Abbreviations

- NRS

-

Numeric rating scale

- ED

-

Emergency department

- EP

-

Educational program

- MCQ

-

Multiple choice questionnaire

- CI

-

95% Confidence interval

- IQR

-

Interquartile range

© 2016 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Editorial comment

- Cardiovascular risk reduction as a population strategy for preventing pain?

- Observational study

- Diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidaemia as risk factors for frequent pain in the back, neck and/or shoulders/arms among adults in Stockholm 2006 to 2010 – Results from the Stockholm Public Health Cohort

- Editorial comment

- Exercising non-painful muscles can induce hypoalgesia in individuals with chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Exercise induced hypoalgesia is elicited by isometric, but not aerobic exercise in individuals with chronic whiplash associated disorders

- Editorial comment

- Education of nurses and medical doctors is a sine qua non for improving pain management of hospitalized patients, but not enough

- Observational study

- Acute pain in the emergency department: Effect of an educational intervention

- Editorial comment

- Home training in sensorimotor discrimination reduces pain in complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

- Original experimental

- Pain reduction due to novel sensory-motor training in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome I – A pilot study

- Editorial comment

- How can pain management be improved in hospitalized patients?

- Original experimental

- Pain and pain management in hospitalized patients before and after an intervention

- Editorial comment

- Is musculoskeletal pain associated with work engagement?

- Clinical pain research

- Relationship of musculoskeletal pain and well-being at work – Does pain matter?

- Editorial comment

- Preoperative quantitative sensory testing (QST) predicting postoperative pain: Image or mirage?

- Systematic review

- Are preoperative experimental pain assessments correlated with clinical pain outcomes after surgery? A systematic review

- Editorial comment

- A possible biomarker of low back pain: 18F-FDeoxyGlucose uptake in PETscan and CT of the spinal cord

- Observational study

- Detection of nociceptive-related metabolic activity in the spinal cord of low back pain patients using 18F-FDG PET/CT

- Editorial comment

- Patients’ subjective acute pain rating scales (VAS, NRS) are fine; more elaborate evaluations needed for chronic pain, especially in the elderly and demented patients

- Clinical pain research

- How do medical students use and understand pain rating scales?

- Editorial comment

- Opioids and the gut; not only constipation and laxatives

- Observational study

- Healthcare resource use and costs of opioid-induced constipation among non-cancer and cancer patients on opioid therapy: A nationwide register-based cohort study in Denmark

- Editorial comment

- Relief of phantom limb pain using mirror therapy: A bit more optimism from retrospective analysis of two studies

- Clinical pain research

- Trajectory of phantom limb pain relief using mirror therapy: Retrospective analysis of two studies

- Editorial comment

- Qualitative pain research emphasizes that patients need true information and physicians and nurses need more knowledge of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

- Clinical pain research

- Adolescents’ experience of complex persistent pain

- Editorial comment

- New knowledge reduces risk of damage to spinal cord from spinal haematoma after epidural- or spinal-analgesia and from spinal cord stimulator leads

- Review

- Neuraxial blocks and spinal haematoma: Review of 166 case reports published 1994–2015. Part 1: Demographics and risk-factors

- Review

- Neuraxial blocks and spinal haematoma: Review of 166 cases published 1994 – 2015. Part 2: diagnosis, treatment, and outcome

- Editorial comment

- CNS–mechanisms contribute to chronification of pain

- Topical review

- A neurobiologist’s attempt to understand persistent pain

- Editorial Comment

- The triumvirate of co-morbid chronic pain, depression, and cognitive impairment: Attacking this “chicken-and-egg” in novel ways

- Observational study

- Pain and major depressive disorder: Associations with cognitive impairment as measured by the THINC-integrated tool (THINC-it)

Articles in the same Issue

- Scandinavian Journal of Pain

- Editorial comment

- Cardiovascular risk reduction as a population strategy for preventing pain?

- Observational study

- Diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidaemia as risk factors for frequent pain in the back, neck and/or shoulders/arms among adults in Stockholm 2006 to 2010 – Results from the Stockholm Public Health Cohort

- Editorial comment

- Exercising non-painful muscles can induce hypoalgesia in individuals with chronic pain

- Clinical pain research

- Exercise induced hypoalgesia is elicited by isometric, but not aerobic exercise in individuals with chronic whiplash associated disorders

- Editorial comment

- Education of nurses and medical doctors is a sine qua non for improving pain management of hospitalized patients, but not enough

- Observational study

- Acute pain in the emergency department: Effect of an educational intervention

- Editorial comment

- Home training in sensorimotor discrimination reduces pain in complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

- Original experimental

- Pain reduction due to novel sensory-motor training in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome I – A pilot study

- Editorial comment

- How can pain management be improved in hospitalized patients?

- Original experimental

- Pain and pain management in hospitalized patients before and after an intervention

- Editorial comment

- Is musculoskeletal pain associated with work engagement?

- Clinical pain research

- Relationship of musculoskeletal pain and well-being at work – Does pain matter?

- Editorial comment

- Preoperative quantitative sensory testing (QST) predicting postoperative pain: Image or mirage?

- Systematic review

- Are preoperative experimental pain assessments correlated with clinical pain outcomes after surgery? A systematic review

- Editorial comment

- A possible biomarker of low back pain: 18F-FDeoxyGlucose uptake in PETscan and CT of the spinal cord

- Observational study

- Detection of nociceptive-related metabolic activity in the spinal cord of low back pain patients using 18F-FDG PET/CT

- Editorial comment

- Patients’ subjective acute pain rating scales (VAS, NRS) are fine; more elaborate evaluations needed for chronic pain, especially in the elderly and demented patients

- Clinical pain research

- How do medical students use and understand pain rating scales?

- Editorial comment

- Opioids and the gut; not only constipation and laxatives

- Observational study

- Healthcare resource use and costs of opioid-induced constipation among non-cancer and cancer patients on opioid therapy: A nationwide register-based cohort study in Denmark

- Editorial comment

- Relief of phantom limb pain using mirror therapy: A bit more optimism from retrospective analysis of two studies

- Clinical pain research

- Trajectory of phantom limb pain relief using mirror therapy: Retrospective analysis of two studies

- Editorial comment

- Qualitative pain research emphasizes that patients need true information and physicians and nurses need more knowledge of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

- Clinical pain research

- Adolescents’ experience of complex persistent pain

- Editorial comment

- New knowledge reduces risk of damage to spinal cord from spinal haematoma after epidural- or spinal-analgesia and from spinal cord stimulator leads

- Review

- Neuraxial blocks and spinal haematoma: Review of 166 case reports published 1994–2015. Part 1: Demographics and risk-factors

- Review

- Neuraxial blocks and spinal haematoma: Review of 166 cases published 1994 – 2015. Part 2: diagnosis, treatment, and outcome

- Editorial comment

- CNS–mechanisms contribute to chronification of pain

- Topical review

- A neurobiologist’s attempt to understand persistent pain

- Editorial Comment

- The triumvirate of co-morbid chronic pain, depression, and cognitive impairment: Attacking this “chicken-and-egg” in novel ways

- Observational study

- Pain and major depressive disorder: Associations with cognitive impairment as measured by the THINC-integrated tool (THINC-it)