Abstract

Background

The presence of high blood flow in the structurally abnormal and painful regions of tendinosis, but not in the normal pain-free tendons, was recently confirmed by colour Doppler (CD) ultrasound (US). Biopsies from the regions with high blood flow demonstrated the presence of sympathetic and sensitive nerve fibres juxtapositioned to neovessels. Grey-scale US and CD are reliable methods used to evaluate structural homogeneity, thickness, and blood flow in the peripheral tendons. The aim of this study was to utilize CD to qualitatively evaluate for the presence of abnormal high blood flow in paravertebral tissues after whiplash injuries in patients with chronic neck pain.

Methods

Twenty patients with chronic neck pain after whiplash-associated disorder (WAD) and 20 pain-free control subjects were included in the study. The same experienced radiologist performed all grey-scale US and CD examinations.

Results

More regions with high blood flow were observed in the patient group than in the control group. At all levels, the high blood flow pattern was detected at the enthesis of the spinous processes and bilaterally juxtapositioned to the facet joints.

Conclusion

All regions identified by the patients as painful and tender corresponded to the positive high blood flow found during the CD examination.

Implications

These findings document increased blood-flow/neovascularisation at insertions of neck muscles which may indicate that there are pathological neovascularisation with accomanying pain-and sympathetic nerves, similar to what has been found in Achilles-tendinosis. These findings promise that similar treatments that now is successful with Achilles tendinosis, may be effective in the WAD-painful muscle insertions of the neck.

1 Introduction

In Western countries, whiplash injuries are a major health problem because of their high prevalence [1, 2] and increasing economic costs [3, 4]. The incidence varies from 1.0 to 3.2/1000 per year [5]. The prevalence of long-term symptoms after whiplash injuries varies. Mayou et al. reported that 35% of patients suffered physical problems 5 years after the injury [6]. Others reported persistent neck pain in 84–90% of patients 1–2 years after the injury [7], or in as much as 50% of patients 17 years after the injury [8].

Although many patients after whiplash trauma recover within a few months after the accident, a significant proportion continues to suffer from prolonged symptoms [5, 9]. The injury may lead to a variety of clinical symptoms known as whiplash-associated disorder (WAD) [10], and the conditions after WAD can affect the activities of daily living, work, and leisure [11, 12].

The pathogenesis of soft-tissue pain after whiplash injury is largely unknown, and several studies have failed to show pathology in the muscles and ligaments of the neck [13, 14, 15].

Recent studies of chronic painful Achilles and patellar tendons, using grey scale ultrasound (US) and colour Doppler (CD), confirmed the presence of high blood flow in the structurally abnormal tender and painful regions of such tendons, but not in the normal pain-free tendons [16, 17]. Studies on biopsies taken from the region with tendon changes and vascular ingrowths have confirmed nerves in close relation to blood vessels [18, 19], and injections of local anaesthetic in the regions with neovessels temporarily abolished the patient’s pain [20]. Grey scale US and CD are reliable methods to evaluate the structure, thickness and blood flow in the Achilles and patellar tendons [21, 22, 23, 24].

The knowledge of the pathogenesis and pathomechanisms behind WAD is lacking. Attempts at the diagnosis and treatment of painful cervical tendinopathies after whiplash injuries have been described since 1950s [25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31]. The only objective findings are the presence of tenderness that is relieved after local anaesthetic infiltration.

Recent findings suggest the presence of persistent paravertebral tissue inflammation in cervical soft tissue in patients with chronic pain after whiplash injuries [32].

More recent publications have disclosed the presence of abnormal blood flow in myofascial trigger points [33].

The aim of this cross-sectional, single-blinded, comparative study was to use US and CD to evaluate the presence of abnormal high blood flow in the painful neck regions in patients with chronic pain after whiplash injury.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

Twenty patients (10 men and 10 women) aged 39.1 ± 9.9 years (mean ± SD) with chronic neck pain from WAD (more than 2 years after injury) were included in the study. Patients were recruited through an internal announcement in the outpatient clinic of the Department of Community Medicine and Rehabilitation, Umeå University Hospital. All patients had sustained their injuries in a vehicle accident. Plain radiographs were obtained on all patients and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was obtained on 12 patients. The imaging did not show abnormal findings. The control group comprised 20 healthy subjects (10 men and 10 women) aged 39.9 ± 9.7 years, with no a history of whiplash injury or neck pain, MRI, or radiographic evaluation. Pain intensity was assessed using the visual analogue scale (VAS). The Disability Rating Index (DRI) was used to assess the level of activity. An additional questionnaire included in the Swedish Quality Registry for Pain Rehabilitation was used to assess pain and associated days lost from work.

2.2 Study design

A cross-sectional, single-blinded, comparative pilot study. The examiner was aware if the subject was a patient or control, but he was not aware of the localization or intensity of pain in patients.

2.3 Visual Analogue Scale

The Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) measures pain intensity [34]. Patients mark their experienced pain on a 100-mm-straight line, where 0 means “no pain” and 100 “worst pain imaginable.” Pain intensity was marked at the time of assessment (pain now) and pain intensity during the last week.

2.4 Disability Rating Index

The Disability Rating Index (DRI) is a clinical research instrument that measures the extent of physical disability (12 items). It covers activities ranging from basic activities (such as dressing and walking) to work-related activities (such as lifting). Patients rate their perceived ability to perform the activities on a 100-mm visual analogue scale, from 0 (no disability) to 100 (inability to perform at all). The distance is measured in mm and an index is obtained. The mean value provides the DRI-index. The DRI has shown acceptable reliability and validity [35].

2.5 Grey-scale ultrasound

The US examination was conducted with the patient in the sitting position with the head slightly flexed forward. It was performed with an Acuson S2000 (Siemens), using a curved 6–2 MHz probe (6C2) in the harmonic imaging mode.

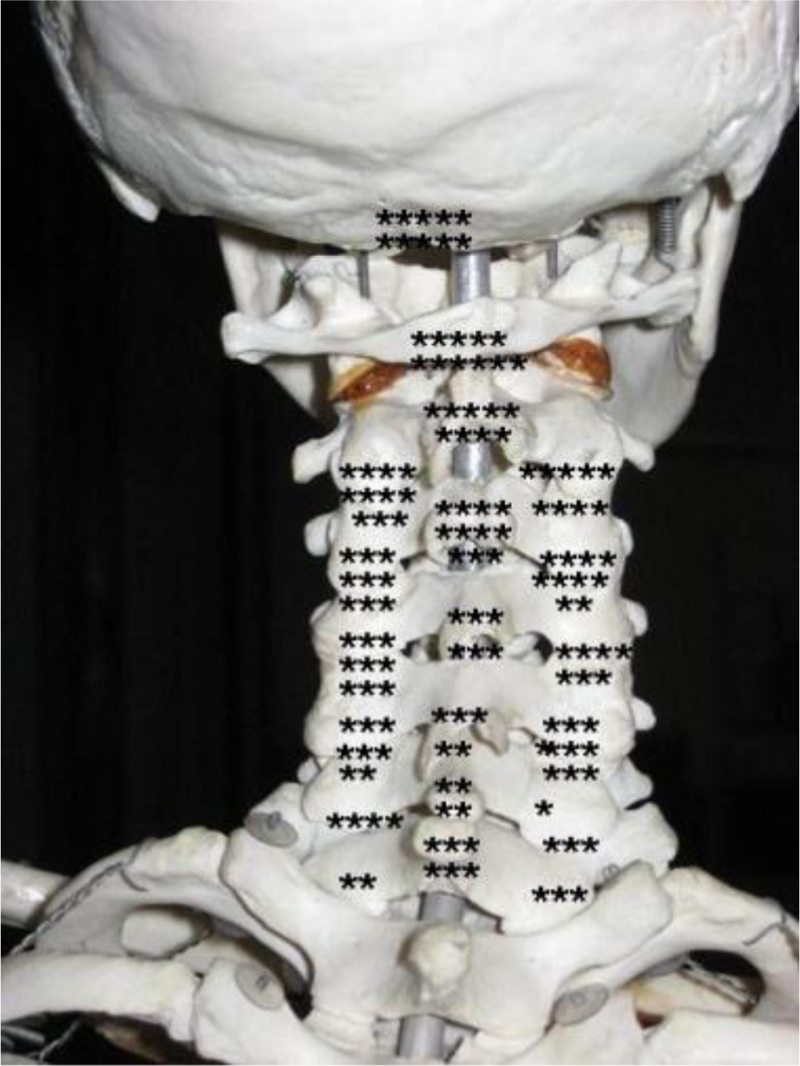

The examination was done systematically, beginning at the nuchal lines on each side, followed by C1 on the right side, then midline and C1 on the left side, followed by C2 on the right side, the spinous process, and C2 on the left side, and thereafter C3-C7 in the same manner.

2.6 Colour Doppler

For the CD examination, the CD velocity technique was used, where the colour of the flow indicated the direction and velocity of the blood flow. The intensity of high blood flow/neovascularisation was graded on a 3-point scale: 0 = 0 vessels, 1 = 1 to 2 vessels, and 2 = 3 vessels or more. All US and CD examinations were done by the same experienced radiologist, and the grading was done by 2 individuals. There was no disagreement in the grading process.

2.7 Ethics

The study was approved by the regional committee for medical research ethics, the Regional Ethical Review Board of Umeå University (Dnr:04–157M) and informed consent was obtained from each participant.

2.8 Statistical methods

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (version 17.0) for Windows. Data were reported as means ± standard deviations unless indicated otherwise. Comparisons of pain intensity, the level of disability, and areas of increased/high intensity blood flow between patients and the control group were made using the Mann-Whitney U test. Chi-square-test was used for the comparison of proportions between the groups. The statistical significance level was set at 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Participants

Eleven patients were working full time, 3 were on sick leave, 3 had disability pension, 2 were unemployed, and 1 was on parental leave. All individuals in the control group were working. A majority of the patients (18/20) complained of severe neck pain, and 2 patients had severe upper back pain. Patients reported statistically significantly (P<0.001) higher pain intensity scores (pain now: 49.4 ± 23.3; pain last week: 58.7 ± 21.6) compared with those in the control group (pain now: 0.1 ± 0.37; pain last week: 0.2 ± 0.5).

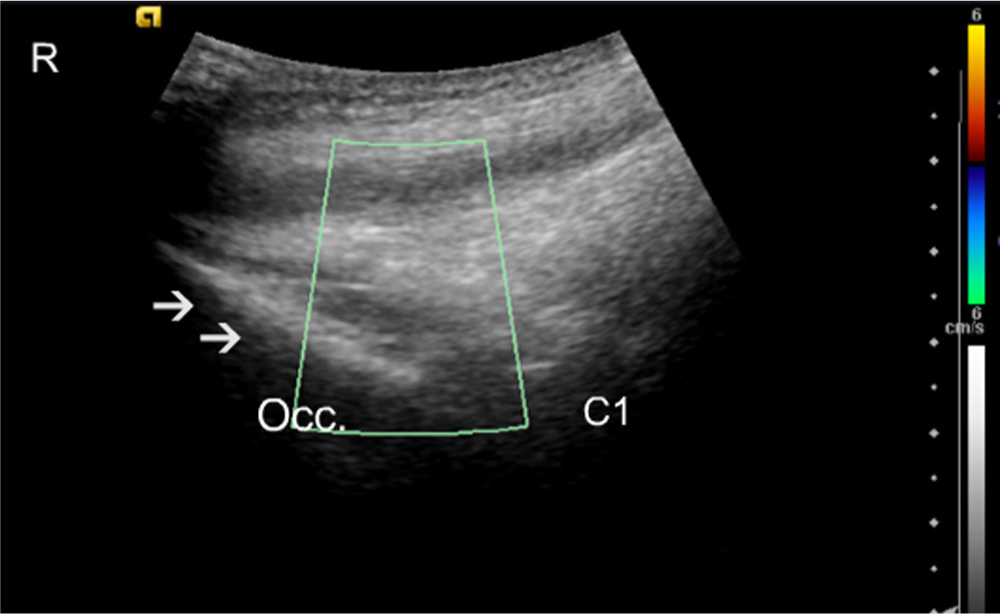

Control subject longitudinal midline. Colour Doppler scan. The C1 area is shown with no apparent blood vessels. Arrows identify the occipital bone (Occ.). R, rostral.

3.2 Disability Rating Index

Patients scored significantly (P <0.001) higher disability on all separate activities and on the DRI (46.4± 18.5) compared with the control-group (0.4 ± 1.2). The highest scores on the separate activities in the patients were running (70.6 ± 30.8), heavy work (79.3 ± 25.0), lifting heavy objects (78.6 ± 23.1), and sitting for a long period (55.6 ± 29.9).

3.3 Colour Doppler

All patients (20/20) hade areas of increased blood flow compared with 12/20 of the controls (P =0.003). Totally, patients had 147 regions of increased blood flow, compared with 39 among the control group, with a ratio 3.7:1, (P <0.001). The high blood flow in the patient group was markedly greater in intensity at each identified level.

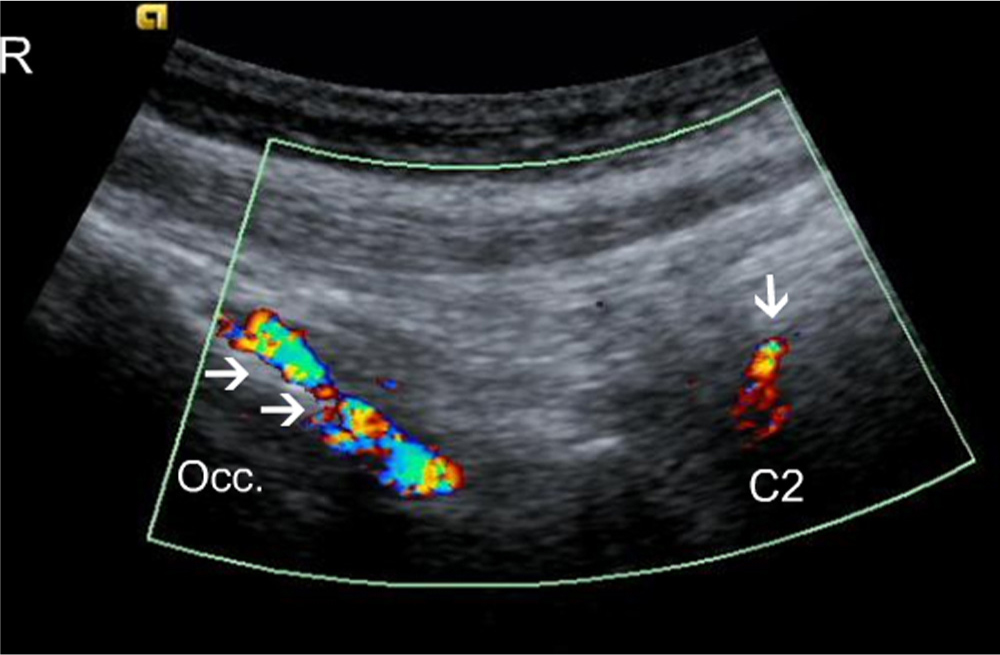

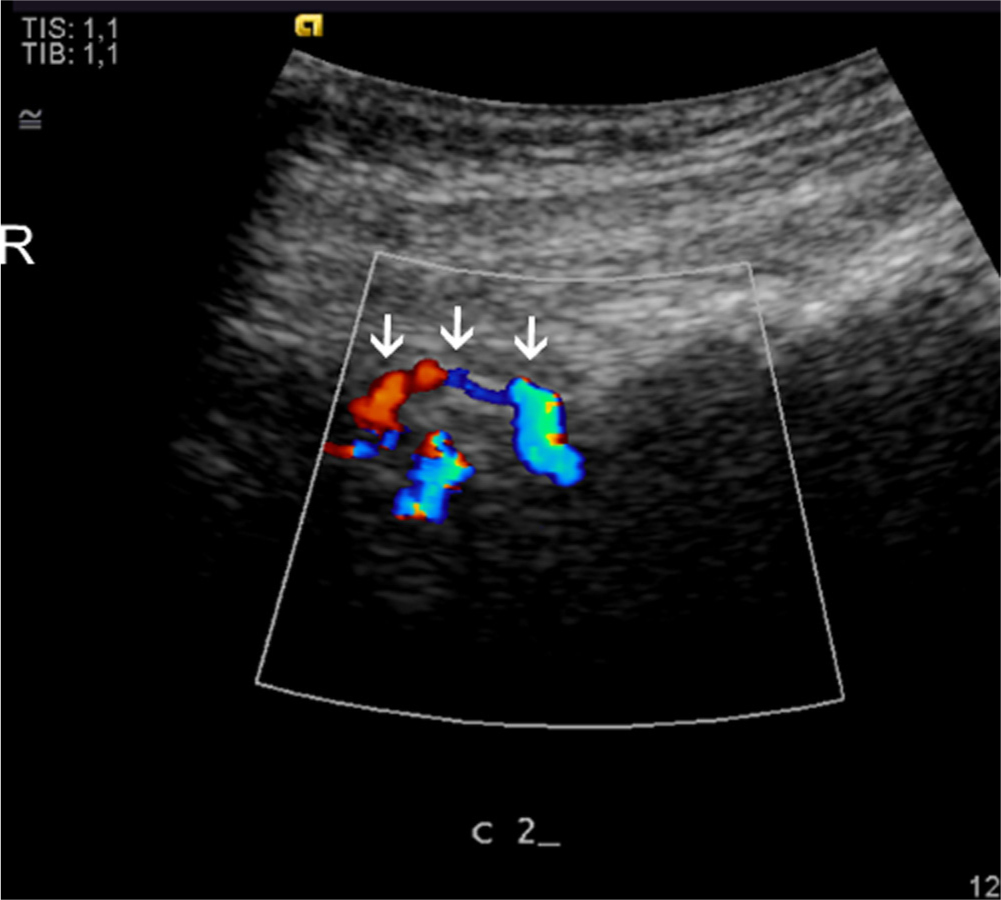

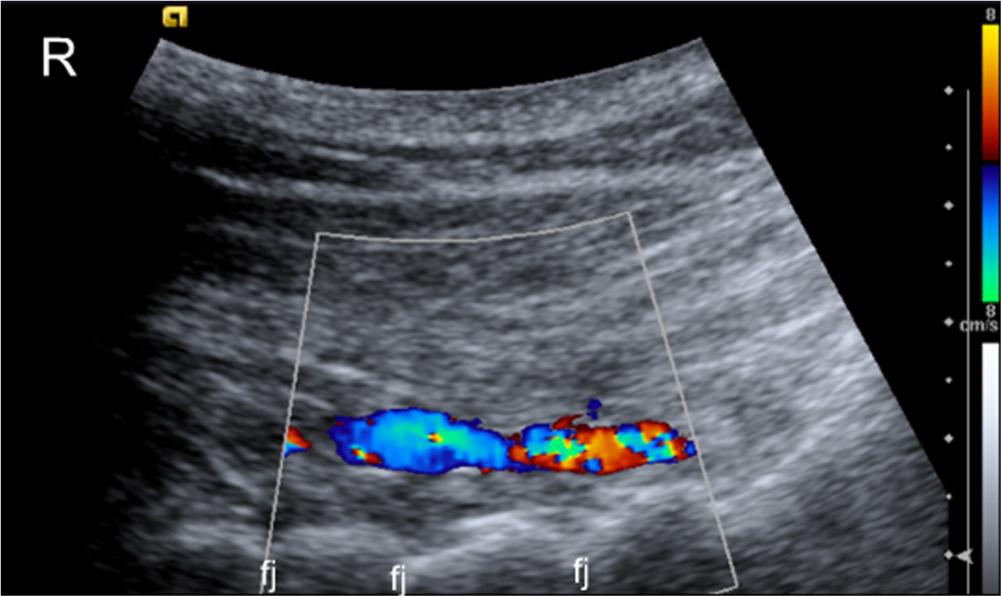

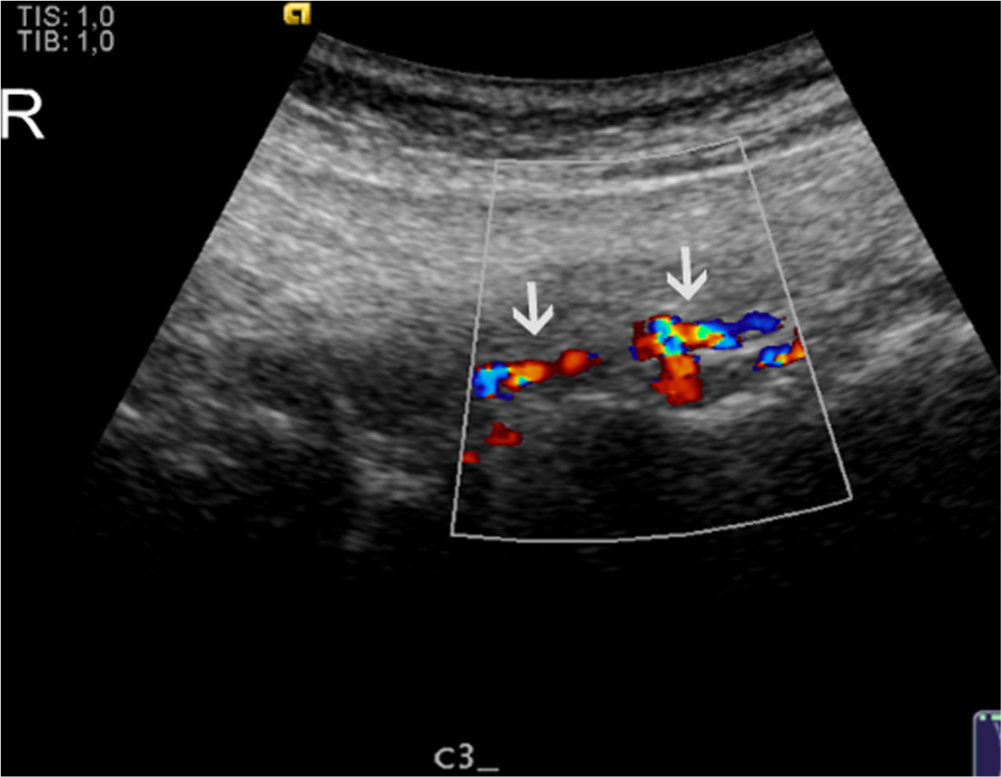

It was not possible to visualize the origin of the blood vessels exactly; however, in the suboccipital region, the high blood flow corresponded to the insertion of the semispinalis capitis and the rectus capitis posterior minor muscles. At the C1 level the high blood flow was more pronounced at the posterior tubercle, corresponding to the insertion of the rectus capitis posterior minor muscles (Figs. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, 4). At the C2 level the high blood flow was found in the region of the spinous process, corresponding to the origin of the rectus capitis posterior major and the obliquus capitis inferior muscles, and bilaterally juxtapositioned to the facet joints (Figs. 5, Fig. 6, 7).

Longitudinal colour, Doppler scan of a patient. Arrows identify blood vessels jusxtapositioned to the occipital bone (Occ.); the single arrow indicates the C2 spinous process and blood flow in the vessels juxtapositioned to it. Occ., Occipital bone; R, rostral.

Longitudinal colour, Dopplerscan of a patient. Arrows identify the C2 spinous processes with blood vessels in the tendons. R, rostral.

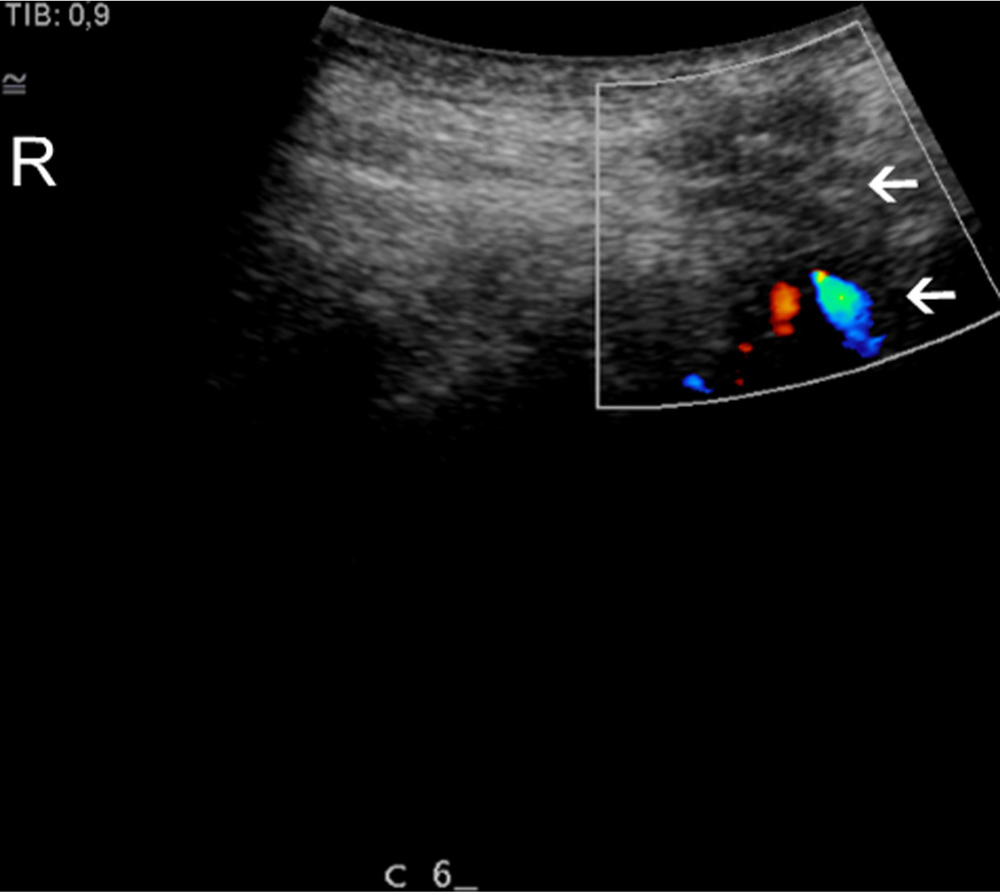

Longitudinal colour, Doppler scan of a patient with blood vessels in muscles juxtapositioned to the midcervical facet joints. Fj, facet joints; R, rostral.

Longitudinal colour, Dopplerscan of a patient. Arrows identify blood vessels juxtapositioned to the left of the C2–3 facet joint. R, rostral.

Longitudinal colour, Doppler scan of a patient. C6 spinous processes. Arrows identify homogeneity and blood vessels in the intraspinous ligament. R, rostral.

Caudally to C2, the changes were similar to those observed C2 level, such that high blood flow was detected at the apices of the spinous process and bilaterally juxtapositioned to the facet joints (Figs. 4, Fig. 5, 6). In the upper cervical region from the base of the skull down to C3, high blood flow was observed more frequently in female than in male patients, totally 48 areas of change in females compared to 33 areas in males (Figs. 7 and 8, Table 1).

Distribution of high blood flow in 20 patients. Each dot represents the localization of high blood flow found in a region in a single patient (regardless of intensity).

Distribution of high blood flow in 20 controls. Each dot represents the localization of high blood flow found in a region in a single control (regardless of intensity).

Regions with high blood flow were also identified in the control group, particularly in males. (Fig. 8 and Table 2).

4 Discussion

The pathogenesis of pain related to whiplash injury is largely unknown. Radiologic modalities such as radiograph, CT, and MRI usually cannot identify any pathology [13, 36, 37]. This, however, does not exclude the existence of pathology that is causing pain and is not detected by these modalities.

Recent findings have shown that WAD patients have higher retention of C-D-deprenyl, a potential marker for inflammation, on Positron Emission Tomography. Patients with WAD displayed significantly elevated tracer uptake in the neck, particularly in regions around the spinous process of the second cervical vertebrae, and also at the insertion of rectus capitis posterior major to the occipital bone [32].

Discoveries related to chronic painful Achilles tendinosis shed light on the pathogenesis of pain in other tendons [16, 38]. Until 10 years ago, the pain was considered to emanate from intrinsic components of the tendon, and treatments focused on intra-tendinous interventions; however, clinical results after such treatments were unpredictable and relatively poor. Treatment of Achilles tendinosis has improved dramatically after the discovery of high blood flow inside and outside the painful tendons but not in the pain free tendons [16]. By using immunohistochemical analyses of biopsies, multiple sensory and sympathetic nerves in close relation to blood vessels outside, but not inside, the painful tendons were found. [18, 19, 39, 40, 48, 49] There was a temporary total pain-relief after US and Doppler-guided injections of a local anaesthetic in the regions with high blood flow outside the painful tendons [20]. Therefore, we employed these methods to evaluate the soft tissue in the neck. In patients with persistent pain after whiplash injury, we found high blood flow in regions of the neck associated with localized pain. Studies of chronic painful tendinosis have attributed high blood flow in painful areas to neovascularization (neovessels), which is accompanied by extrinsic, and possibly also to some extent, an intrinsic neural ingrowth. Treatments were directed to target the pathologically increased blood flow in the regions with tendinosis, thereby also affecting the nerves juxtapositioned to the blood vessels. Clinical, pilot and randomized controlled studies, has shown a high success rate with a fast return to pain-free tendon loading activities [45, 46, 47]. US and Doppler follow-ups have demonstrated decreased thickness and improved tendon structure in pain-free tendons [41].

Distribution of high blood flow and blood flow intensity in patients.

| Patient | Sex | Age | SB | Cl | C2 | C2 | C2 | C3 | C3 | C3 | C4 | C4 | C4 | C5 | C5 | C5 | C6 | C6 | C6 | C7 | C7 | C7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP | Dx | Sin | SP | Dx | Sin | SP | Dx | Sin | SP | Dx | Sin | SP | Dx | Sin | SP | Dx | Sin | |||||

| 1 | F | 25 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | F | 32 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | F | 32 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | F | 33 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | F | 34 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | F | 37 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | F | 37 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | F | 41 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | F | 48 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | F | 51 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | M | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 12 | M | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 13 | M | 31 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | M | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | M | 42 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | M | 44 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 17 | M | 44 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | M | 53 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 19 | M | 53 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | M | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

-

0 indicates no vessels; 1, 1–2 vessels; 2, >3vessels; SB, base of the skull; SP, spinous process; Dx, right side; Sin, left side.

-

A grading system originating from the Ohberg grading system.

The current study investigated the possible existence of high blood flow in patients with persistent local pain and tenderness in the cervical spine after whiplash injuries. The radiologist who performed the US and CD examinations was blinded to the symptoms, points of tenderness and findings of the physical examination, and the US and CD evaluation was performed in a systematic fashion. Most regions, identified as tender by the patients, were positive for high blood flow during the CD examination. High blood flow was found most frequently at the common enthesis of the nuchal lines, the C2 and C7 spinous processes, and the C2–3 and C6–7 Z-joints.

The radiologist who performed all of the US examinations is highly experienced and was previously involved in multiple studies using CD technique to evaluate blood flow. Findings of his tendon examinations have a high degree of reproducibility [42].

The interobserver reliability of neovascularisation score using colour Doppler ultrasonography in midportion Achilles tendinopathy has been shown to be excellent [43]. The modified Ohberg score is used to quantify the intensity of high blood flow in midportion Achilles tendinopathy where 0 (no vessels visible), 1+ (1 vessel, mostly anterior to the tendon), 2+ (1 or 2 vessels throughout the tendon), 3+ (3 vessels throughout the tendon), or 4+ (more than 3 vessels throughout the tendon) [44]. We used a similar grading system, but the increased blood flow detected in our study lies in deeper planes than the Achilles tendons and in more heterogeneous tissue, i.e., different muscle insertions, capsular ligaments, supraspinous ligaments, and adipose tissue juxtapositioned to the deep cervical structures.

Distribution of high blood flow and blood flow intensity in controls.

| Control | Sex | Age | SB | Cl | C2 | C2 | C2 | C3 | cs | C3 | C4 | C4 | C4 | C5 | C5 | C5 | C6 | C6 | C6 | C7 | C7 | C7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP | Dx | Sin | SP | Dx | Sin | SP | Dx | Sin | SP | Dx | Sin | SP | Dx | Sin | SP | Dx | Sin | |||||

| 1 | F | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | F | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | F | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | F | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | F | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | F | 37 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | F | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | F | 39 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | F | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | F | 51 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | M | 25 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | M | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | M | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | M | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | M | 41 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | M | 43 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 17 | M | 49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | M | 53 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 19 | M | 54 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | M | 60 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

-

0 indicates no vessels; 1, 1–2 vessels; 2, >3vessels; SB, base of the skull; SP, spinous process; Dx, right side; Sin, left side.

-

A grading system originating from the Ohberg grading system.

This study was limited in that it included a relatively small number of patients, and there were difficulties in quantifying the degree of blood flow. In addition, the radiologist was only blinded to the symptoms and to localization of pain in the patients group.

5 Conclusion

This study demonstrated the presence of high blood flow in painful tender regions of the neck in a group of 20 patients suffering from chronic neck pain after whiplash injury. Further studies to grade the increased blood flow and to evaluate the possible relationship between the region with localized high blood flow and pain are in progress.

HIGHLIGHTS

Painful neck regions in patients with whiplash-associated disorder were studied.

Grey scale ultrasound and colour Doppler were used to confirm high blood flow.

Whiplash patients had higher blood flow compared with the control subjects.

High blood flow was found in painful regions of the neck in whiplash patients.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2013.07.024.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Galasco CSB, Murray PA, Pitcher M. Prevalence and long-term disability following whiplash-associated disorder. J Musculoskele Pain 2000;8:15–27.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Herrstrom P, Lannerbro-Geijer G, Hogstedt B. Whiplash injuries from car accidents in a Swedish middle-sized town during 1993–95. Scand J Prim Health Care 2000;18:154–8.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Bylund PO, Bjornstig U. Sick leave and disability pension among passengercar occupants injured in urbantraffic. Spine 1998;23:1023–8.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Galasko CSB, Murray P, Stephenson W. Incidence of whiplash-associated disorder. B C Med J 2002;44:237–40.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Sterner Y, Toolanen G, Gerdle B, Hildingsson C. The incidence of whiplash trauma and the effects of different factors on recovery. J Spinal Disord Tech 2003;16:195–9.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Mayou R, Tyndel S, Bryant B. Long-term outcome of motor vehicle accident injury. Psychosom Med 1997;59:578–84.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Kyhlback M, Thierfelder T, Soderlund A. Prognostic factors in whiplash-associated disorders. Int J Rehabil Res 2002;25:181.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Bunketorp L, Nordholm L, Carlsson J. A descriptive analysis of disorders in patients 17 years following motor vehicle accidents. Eur Spine J 2002;11:227–34.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Haldorsen T, Waterloo K, Dahl A, Mellgren SI, Davidsen PE, Molin PK. Symptoms and cognitive dysfunction in patients with the late whiplash syndrome. Appl Neuropsychol 2003;10:170–5.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Spitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR, Cassidy JD, Duranceau J, Suissa S, Zeiss E. Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders: redefining “whiplash” and its management. Spine 1995;20: 1S-73S.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Peolsson M, Borsbo B, Gerdle B. Generalized pain is associated with more negative consequences than local or regional pain: a study of chronic whiplash-associated disorders. J Rehabil Med 2007;39:260–8.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Hagan KS, Naqui SZ, Lovell ME. Relationship between occupation, social class and time taken off work following a whiplash injury. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2007;89:624–6.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Borchgrevink GE, Smevik O, Nordby A, Rinck PA, Stiles TC, Lereim I. MR imaging and radiography of patients with cervical hyperextension-flexion injuries after car accidents. Acta Radiol 1995;36:425–8.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Dullerud R, Gjertsen O, Server A. Magnetic resonance imaging of ligaments and membranes in the craniocervical junction in whiplash-associated injury and in healthy control subjects. Acta Radiol 2010;51:207–12.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Wilmink JT, Patijn J. MR imaging of alar ligament in whiplash-associated disorders: an observer study. Neuroradiology 2001;43:859–63.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Ohberg L, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Neovascularisation in Achillestendons with painful tendinosis but not in normal tendons: an ultrasonographic investigation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2001;9:233–8.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Hoksrud A, Ohberg L, Alfredson H, Bahr R. Color Doppler ultrasound findings in patellar tendinopathy (jumper’s knee). Am J Sports Med 2008;36: 1813–20.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Bjur D, Alfredson H, Forsgren S. The innervation pattern of the human Achilles tendon: studies on the normal and tendinosis tendon using markers for general and sensory innervation. Cell Tissue Res 2005;320: 201–6.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Danielsson P, Alfredson H, Forsgren S. Distribution of general (PGP 9.5) and sensory (substance P/CGRP) innervations in the human patellar tendon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2006;4:125–32.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Alfredsson H, Ohberg L, Forsgren S. Is vasculo-neural ingrowth the cause of pain in chronic Achilles tendinosis? An investigation using ultrasonongraphy and colour Doppler, immunohistochemistry, and diagnostic injections. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2003;11:334–8.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Movin T, Gad A, Reinholt FP. Tendon pathology in long-standing Achillodynia. Biopsy findings in 40 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 1997;68:170–5.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Paavola M, Paakkala T, Kannus P, Jarvinen M, Rausing A, Sjoberg S, Westlin N. Ultrasonography in the differential diagnosis of Achilles tendon injuries and related disorders. Acta Radiol 1998;39:612–9.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Astrom M, Gentz CF, Nilsson P, Rausing A, Sjoberg S, Westlin N. Imaging in chronic Achilles tendinopathy: acomparison of ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging and surgical findings in 27 histologically verified cases. Skeletal Radiol 1996;1:615–20.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Weinberg EP, Adams MJ, Hollenberg GM. Color Doppler sonography of patellar tendinosis. Am J Roentgenol 1998;71:743–4.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Hackett G. Prolotherapy in whiplash and low back pain. Postgrad Med 1960;27:214–9.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Hackett G, Huang TC, Raftery A. Prolotherapy for headache: pain in the head and neck, and neuritis. Headache 1962;2:20–8.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Kayfetz D. Occipito-cervical (whiplash) injuries treated by prolotherapy. Med Trial Tech Q 1963;9:9–29.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Kayfetz D, Blumenthal LS, Hackett GS, Hemwall GA, Neff FE. Whiplash injury and other ligamentous headache-its management with prolotherapy. Headache 1963;3:21–8.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Linetsky F, Derby R, Miguel R. Pain management with regenerative injection therapy (RIT). In: Boswell M, Cole BE, editors. Weiner’s pain management: a practical guide for clinicians. 7th ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2006. p. 939–66.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Lord S. Chronic cervical zygoapophyseal joint pain after whiplash a placebo-controlled prevalence study. Spine 1996;21:1737–45.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Linetsky FS, Miguel R, Torres F. Treatment of cervicothoracic pain and cervicogenic headaches with regenerative injection therapy. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2004;8:41–8.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Linnman C, Appel L, Fredrikson M, Gordh T, Soderlund A, Langstrom B, Elevated Engler H. [11C]-D-deprenyl uptake in chronic Whiplash Associated Disorder suggests persistent musculoskeletal inflammation. PLoS ONE 2011;6: e19182.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Sikdar S, Shah JP, Gebreab T, Yen Rh Gilliams E, Danoff J, Gerber LH. Novel applications of ultrasound technology to visualize and characterize myofascial trigger points and surrounding soft tissue. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009;90:1829–38.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Price DD, Bush FM, Long S, Harkins SW. A comparison of pain measurement characteristics of mechanical visual analogue and simple numerical rating scales. Pain 1994;56:217–26.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Salen BA, Spangfort EV, Nygren AL, Nordemar R. The Disability Rating Index: an instrument for the assessment of disability in clinical settings. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1423–35.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Ronnen HR. Acutewhiplash injury: is there a role for MR imaging?-a prospective study of 100 patients. Radiology 1996;201:93–6.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Ichihara D, Okada E, Chiba K, Toyama Y, Fujiwara H, Momoshima S, Nishiwaki Y, Hashimoto T, Ogawa J, Watanabe M, Takahata T, Matsumoto M. Longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study on whiplash injury patients: minimum 10-year follow-up. J Orthop Sci 2009;14:602–10.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Gisslen K, Alfredson H. Neovascularisation and pain in jumper’s knee: a prospective clinical and sonographic study in elite junior volleyball players. Br J Sports Med 2005;39:423–8.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Ohberg L, Alfredson H. Effects on neovascularisation behind the good results with eccentric training in chronic mid-portion Achilles tendinosis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2004;12:465–70.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Alfredson H, Lorentzon R. Chronictendon pain: no signs of chemical inflammation but high concentrations of the neurotransmitter glutamate. Implications for treatment? Curr Drug Targets 2002;3:43–54.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Lind B, Ohberg L, Alfredson H. Sclerosing polidocanol injections in midportion Achilles tendinosis: remaining good clinical results and decreased tendon thickness at 2-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2006;14:1327–32.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Ohberg L, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Eccentric training in patients with chronic Achilles tendinosis: normalised tendon structure and decreased thickness at follow up. Br J Sports Med 2004;38:8–11.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Sengkerij PM, de Vos RJ, Weir A. Interobserver reliability of neovascularization score using power Doppler ultrasonography in midportion achilles tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:1627–31.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Ohberg L, Alfredson H. Ultrasound guided sclerosis of neovessels in painful chronic Achilles tendinosis: pilot study of a new treatment. Br J Sports Med 2002;36:173–5.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Alfredson H, Ohberg L. Sclerosing injections to areas of neovascularisation reduce pain in chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2005;13: 338–44.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Alfredson H, Ohberg L. Neovascularisation in chronic painful patellar tendinosis-promising results after sclerosing neovessels outside the tendon challenges the need for surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2005;13:74–80.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Willberg L, Sunding K, Ohberg L, Forsblad M, Fahlstrom M, Alfredson H. Sclerosing injections to treat midportion Achilles tendinosis: a randomised controlled study evaluating two different concentrations of Polidocanol. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2008;16:859–64.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Andersson G, Danielson P, Alfredson H, Forsgren S. Nerve-related characteristics of ventral paratendinous tissue in chronic Achilles tendinosis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007;15:1272–9.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Danielsson P, Andersson G, Alfredson H, Forsgren S. Marked sympathetic component in the perivascular innervation of the dorsal paratendinous tissue of the patellar tendon in arthroscopically treated tendinosis patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2008;16:621–6.Search in Google Scholar

© 2013 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain – The invisible disease? Not anymore!

- Clinical pain research

- New objective findings after whiplash injuries: High blood flow in painful cervical soft tissue: An ultrasound pilot study

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain is strongly associated with work disability

- Observational studies

- Chronic pain: One year prevalence and associated characteristics (the HUNT pain study)

- Editorial comment

- Pain rehabilitation in general practice in rural areas? It works!

- Clinical pain research

- Effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment for patients with chronic pain in a primary health care unit

- Editorial comment

- Mirror-therapy: An important tool in the management of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

- Topical review

- Mirror therapy for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)—A literature review and an illustrative case report

- Editorial comment

- New insight in migraine pathogenesis: Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the circulation after sumatriptan

- Original experimental

- Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the circulation after sumatriptan

- Editorial comment

- Statistical pearls: Importance of effect-size, blinding, randomization, publication bias, and the overestimated p-values

- Topical review

- Significance tests in clinical research—Challenges and pitfalls

- Editorial comment

- Biomarkers of pain – Zemblanity?

- Topical review

- Mechanistic, translational, quantitative pain assessment tools in profiling of pain patients and for development of new analgesic compounds

- Editorial comment

- Chronic Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV): A possible cause of chronic, otherwise unexplained neck-pain, headache, and widespread pain and fatigue, which may respond positively to repeated particle repositioning manoeuvres (PRM)

- Observational studies

- Pain and other symptoms in patients with chronic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

- Editorial comment

- The most important step forward in modern medicine, “a giant leap for mankind”: Insensibility to pain during surgery and painful procedures

- Topical review

- In praise of anesthesia: Two case studies of pain and suffering during major surgical procedures with and without anesthesia in the United States Civil War-1861–65

- Editorial comment

- Intravenous non-opioids for immediate postop pain relief in day-case programmes: Paracetamol (acetaminophen) and ketorolac are good choices reducing opioid needs and opioid side-effects

- Clinical pain research

- Intravenous acetaminophen vs. ketorolac for postoperative analgesia after ambulatory parathyroidectomy

- Editorial comment

- Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain 2013—Annual scientific meeting abstracts of pain research presentations and greetings from incoming President

- Abstracts

- Why does the impact of multidisciplinary pain management on quality of life differ so much between chronic pain patients?

- Abstracts

- Health care utilization in chronic pain—A population based study

- Abstracts

- Pain treatment in rural Ghana—A qualitative study

- Abstracts

- Pain psychology specialist training 2012–2014

- Abstracts

- Pain assessment, documentation, and management in a university hospital

- Abstracts

- Promising effects of donepezil when added to patients treated with gabapentin for neuropathic pain

- Abstracts

- A pediatric patients’ pain evaluation in the emergency unit

- Abstracts

- Proteomic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid gives insight into the pain relief of spinal cord stimulation

- Abstracts

- The DQB1(*)03:02 HLA haplotype is associated with increased risk of chronic pain after inguinal hernia surgery and lumbar disc herniation

- Abstracts

- On the pharmacological effects of two lidocaine concentrations tested on spontaneous and evoked pain in human painful neuroma: A new clinical model of neuropathic pain

- Abstracts

- The mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone enhances morphine antinociception

- Abstracts

- Expression of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in dorsal root ganglia in diabetic rats 6 months and 1 year after diabetes induction

- Abstracts

- Histamine in the locus coeruleus attenuates neuropathic hypersensitivity

- Abstracts

- Pronociceptive effects of a TRPA1 channel agonist methylglyoxal in healthy control and diabetic animals

- Abstracts

- Human inducible pluripotent stem cell-derived sensory neurons express multiple functional ion channels and GPCRs

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain – The invisible disease? Not anymore!

- Clinical pain research

- New objective findings after whiplash injuries: High blood flow in painful cervical soft tissue: An ultrasound pilot study

- Editorial comment

- Chronic pain is strongly associated with work disability

- Observational studies

- Chronic pain: One year prevalence and associated characteristics (the HUNT pain study)

- Editorial comment

- Pain rehabilitation in general practice in rural areas? It works!

- Clinical pain research

- Effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabilitation treatment for patients with chronic pain in a primary health care unit

- Editorial comment

- Mirror-therapy: An important tool in the management of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

- Topical review

- Mirror therapy for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)—A literature review and an illustrative case report

- Editorial comment

- New insight in migraine pathogenesis: Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the circulation after sumatriptan

- Original experimental

- Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) in the circulation after sumatriptan

- Editorial comment

- Statistical pearls: Importance of effect-size, blinding, randomization, publication bias, and the overestimated p-values

- Topical review

- Significance tests in clinical research—Challenges and pitfalls

- Editorial comment

- Biomarkers of pain – Zemblanity?

- Topical review

- Mechanistic, translational, quantitative pain assessment tools in profiling of pain patients and for development of new analgesic compounds

- Editorial comment

- Chronic Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV): A possible cause of chronic, otherwise unexplained neck-pain, headache, and widespread pain and fatigue, which may respond positively to repeated particle repositioning manoeuvres (PRM)

- Observational studies

- Pain and other symptoms in patients with chronic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

- Editorial comment

- The most important step forward in modern medicine, “a giant leap for mankind”: Insensibility to pain during surgery and painful procedures

- Topical review

- In praise of anesthesia: Two case studies of pain and suffering during major surgical procedures with and without anesthesia in the United States Civil War-1861–65

- Editorial comment

- Intravenous non-opioids for immediate postop pain relief in day-case programmes: Paracetamol (acetaminophen) and ketorolac are good choices reducing opioid needs and opioid side-effects

- Clinical pain research

- Intravenous acetaminophen vs. ketorolac for postoperative analgesia after ambulatory parathyroidectomy

- Editorial comment

- Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain 2013—Annual scientific meeting abstracts of pain research presentations and greetings from incoming President

- Abstracts

- Why does the impact of multidisciplinary pain management on quality of life differ so much between chronic pain patients?

- Abstracts

- Health care utilization in chronic pain—A population based study

- Abstracts

- Pain treatment in rural Ghana—A qualitative study

- Abstracts

- Pain psychology specialist training 2012–2014

- Abstracts

- Pain assessment, documentation, and management in a university hospital

- Abstracts

- Promising effects of donepezil when added to patients treated with gabapentin for neuropathic pain

- Abstracts

- A pediatric patients’ pain evaluation in the emergency unit

- Abstracts

- Proteomic analysis of cerebrospinal fluid gives insight into the pain relief of spinal cord stimulation

- Abstracts

- The DQB1(*)03:02 HLA haplotype is associated with increased risk of chronic pain after inguinal hernia surgery and lumbar disc herniation

- Abstracts

- On the pharmacological effects of two lidocaine concentrations tested on spontaneous and evoked pain in human painful neuroma: A new clinical model of neuropathic pain

- Abstracts

- The mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone enhances morphine antinociception

- Abstracts

- Expression of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in dorsal root ganglia in diabetic rats 6 months and 1 year after diabetes induction

- Abstracts

- Histamine in the locus coeruleus attenuates neuropathic hypersensitivity

- Abstracts

- Pronociceptive effects of a TRPA1 channel agonist methylglyoxal in healthy control and diabetic animals

- Abstracts

- Human inducible pluripotent stem cell-derived sensory neurons express multiple functional ion channels and GPCRs