Abstract

A high proportion of patients suffering from neuropathic pain do not receive satisfactory pain relief from their current treatment, due to incomplete efficacy and dose-limiting adverse effects. Hence, one strategy to improve treatment outcome is the use of a combination of analgesic drugs. The potential benefits of such approach include improved and prolonged duration of analgesic effect and fewer or milder adverse effects with lower doses of each drug. Gabapentin is recommended as a first-line drug in the treatment of neuropathic pain, and has recently been demonstrated to act on supraspinal structures to stimulate the descending noradrenergic pain inhibitory system. Hypothetically, the analgesic effect of gabapentin may be potentiated if combined with a drug that prolongs the action of noradrenaline.

In this study, gabapentin was co-administered with the serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine, and subsequently evaluated for its effect on mechanical hypersensitivity in the rat spared nerve injury model of neuropathic pain. In this model, two branches of the sciatic nerve (the tibial and common peroneal nerves) are ligated and cut, leaving the third branch (the sural nerve) intact to innervate the hind paw of the animal. Treatment-induced ataxia was tested in order to exclude biased effect measurements. Finally, the pharmacokinetics of gabapentin was investigated alone and in combination with venlafaxine to elucidate any alterations which may have consequences for the pharmacological effect and safety.

The overall effect on nerve injury-induced hypersensitivity of co-administered gabapentin (60 mg/kg s.c.) and venlafaxine (60 mg/kg s.c.), measured as the area under the effect-time curve during the three hour time course of testing, was similar to the highest dose of gabapentin (200 mg/kg s.c.) tested in the study. However, this dose of gabapentin was associated with ataxia and severe somnolence, while the combination was not. Furthermore, when administered alone, an effect delay of approximately one hour was observed for gabapentin (60 mg/kg s.c.) with maximum effect occurring 1.5 to 2.5 h after dosing, while venlafaxine (60 mg/kg s.c.) was characterised by a rapid onset of action (within 30 min) which declined to baseline levels before the end of the three hour time of testing. The effect of co-administered drugs (both 60 mg/kg s.c.), in the doses used here, can be interpreted as additive with prolonged duration in comparison to each drug administered alone. An isobolographic study design, enable to accurately classify the combination effect into additive, antagonistic or synergistic, was not applied. The pharmacokinetics of gabapentin was not altered by co-administered venlafaxine, implying that a pharmacokinetic interaction does not occur. The effect of gabapentin on the pharmacokinetics of venlafaxine was not studied, since any alterations are unlikely to occur on the basis of the pharmacokinetic properties of gabapentin.

In conclusion, the results from this preclinical study support the rationale for improved effect and less adverse effects through combination therapy with gabapentin and venlafaxine in the management of neuropathic pain.

1 Introduction

Neuropathic pain may affect as much as 3% of the population, and these patients are a challenge to manage due to the severity of the pain and the lack of effective treatment [1, 2]. Many patients experience impaired mood and quality of life, with depression and sleeping disorders as common complications [3, 4].

Gabapentin is recommended as a first-line drug in the treatment of neuropathic pain [5, 6], based on evidence from numerous clinical trials [7, 8, 9]. Nevertheless, gabapentin as monotherapy may be limited by incomplete efficacy and dose-limiting adverse effects (sedation, dizziness, ataxia), resulting in unsatisfactory pain relief in a high proportion of patients. This is reflected in the estimated number needed to treat; approximately four patients need to be treated with gabapentin to reduce the pain by 50% in one patient [10]. Hence, one strategy to improve pain relief and/or reduce adverse effects is the use of a combination of analgesic drugs acting through different mechanisms [11].

Gabapentin is identified as a ligand to the α2δ subunit of the voltage-gated calcium channel [12]. Binding to this site inhibits calcium influx at presynaptic nerve terminals, and subsequently reduces the release of several neurotransmitters. The antihyper-sensitivity actions of gabapentin are correlated with up-regulation of the α2δ subunit in the spinal cord and/or dorsal root ganglia in experimental models of neuropathic pain [13]. Even though the spinal cord has been in focus as the primary site of the analgesic actions of gabapentin, it has in recent experimental studies been demonstrated that gabapentin also acts on supraspinal structures to stimulate the descending noradrenergic endogenous pain inhibitory system [14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]. This finding suggests a new treatment approach for gabapentin, i.e. to combine with a drug that prolongs the action of noradrenaline.

The present study evaluated the effect of co-administered gabapentin and venlafaxine in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Venlafaxine facilitates neurotransmission in the brain by blocking presynaptic reuptake of serotonin and noradrenaline [20], and may serve as a suitable adjuvant to augment the analgesic effect of gabapentin. It was further tested whether the treatments were associated with ataxia and other side effects that may interfere with the effect measurements.

Finally, the pharmacokinetics of gabapentin was investigated alone and in combination with venlafaxine to elucidate any alterations which may have consequences for the pharmacological effect and safety of the drug.

2 Materials and methods

All experiments were approved by the Animals Experiments Inspectorate, The Danish Ministry of Justice (no. 2007/561-1284 C7), and were in accordance with the ethic standards of IASP’s guidelines for pain research in animals [21].

2.1 Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (200–250 g), obtained from Taconic (Ejby, Denmark), were housed under a 12:12 h light–dark cycle with standard diet and water ad libitum. The animals were allowed to habituate to the housing facilities for at least one week prior to surgery or behavioural testing.

2.2 Surgical procedures

2.2.1 Induction of neuropathic pain behaviour

SNI was performed to induce neuropathic pain behaviour as previously described [22]. Animals were anaesthetised with a subcutaneously administered mixture of fentanyl 0.21 mg/kg, fluanisone 6.8 mg/kg and midazolam 3.4 mg/kg. The skin of the lateral left thigh was incised and the proximal and distal parts of the biceps femoris muscle were separated to expose the sciatic nerve and its three terminal branches; the sural, tibial and common peroneal nerves. The tibial and common peroneal nerves were tightly ligated using 4.0 silk sutures (Ethicon Black Perma-hand, E-vet, Haderslev, Denmark) and 2–3 mm of the nerve distal to the ligation was removed. Any stretching or contact with the intact sural nerve was avoided. The muscle and skin were closed in two layers with 4.0 synthetic absorbable surgical sutures (Ethicon violet, E-vet, Haderslev, Denmark). After this procedure, the animal developed hypersensitivity of the hind paw, as an indication of neuropathic pain. The animals were allowed to recover from surgery for one week.

2.2.2 Implantation of femoral artery catheters

Femoral artery catheters were implanted according to standard surgical procedures. Animals were anaesthetised with isoflurane (1.75 vol%, O2 0.5 L/min, N2O 1.0 L/min). A small incision in the skin over the right femoral artery was made, followed by blunt dissection through the subcutaneous fat and connective tissue to expose the vessel. A 5 mm section of the vessel was isolated, a loose ligature was tied distally and the proximal end was ligated. A small incision was made between these ligatures, and a polyethylene catheter was introduced and secured in place with the preplaced sutures. The end of the catheter was tunnelled subcutaneously to exit at the surface of the neck, out of reach of the paws of the animal. After implantation of catheters, animals were housed individually and were allowed to recover from surgery for one week.

2.3 Behavioural tests

2.3.1 Von Frey test

Withdrawal threshold in response to mechanical stimuli following SNI was assessed using a set of calibrated von Frey monofilaments (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA). The bending force of the filaments in mN was: 0.196, 0.392, 0.686, 1.57, 3.92, 5.88, 9.80, 13.7, 19.6, 39.2, 58.8, 78.4, 98.0, 147 and 255 (equivalent to mass of 0.02–26 g). The filaments were applied to the lateral plantar surface of the hind paw, and response threshold was the bending force of the first filament in the series that produced three withdrawals after five consecutive stimulations. If there was no response to the stiffest filament, threshold was recorded as 26 g. Only animals showing distinct mechanical hypersensitivity, defined by a withdrawal threshold ≤2 g, from 6 to 10 days post-surgery were included in pharmacological testing experiments. 28 (93%) out of 30 SNI-operated animals fulfilled this criteria.

On the day of drug testing, after a baseline response was obtained prior to drug administration, the withdrawal response was monitored every 30 min for 3 h post-dosing. During this period of time, the animals had no access to drinking water and the experiments were therefore always terminated at the pre-specified time.

2.3.2 Rotarod test

Treatments with distinct increase in withdrawal threshold in the von Frey test were tested for interfering ataxic effects using a Rotarod (Ugo Basile, Comero, Italy). Normal, non-SNI rats were required to walk against the motion of the rotating drum (16 rpm), and the time on the rod from start until the animal fell from the drum was recorded. A cut-off of 200 s was used. Two training periods, separated by 3–4 h, were performed on two separate days before pharmacological testing.

On the day of drug testing, following a baseline measurement, animals were administered with drug and testing was subsequently performed at 1, 2 and 3 h post-dosing.

2.4 Pharmacokinetic investigation

2.4.1 Blood sampling

Sparse blood samples were collected following subcutaneous administration of gabapentin (60 mg/kg) alone and in combination with venlafaxine (40 mg/kg), using a cross over-design. All animals were subjected to two blood sampling sessions, which were separated by two weeks for recovery purposes. The animals were divided in two groups, and blood (300 μl) was withdrawn for group 1 at 0.25, 0.75, 1.5, 2.5 and 4 h after dosing and for group 2 at 0.5, 1, 2, 3 and 6 h after dosing. Plasma was immediately separated by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min and stored at −18°C until analysed for gabapentin concentrations. The maximum cumulative blood volume withdrawn from any one animal never exceeded 10% of the total blood volume [23] and a continuous infusion of isotonic saline (0.5 ml/h) was given in order to maintain fluid balance. Animals were habituated to restriction cages during 2 h one day before blood sampling, in order to avoid stress during handling.

2.4.2 Bioanalythical method

Derived plasma was analysed for gabapentin concentrations using a HPLC method with UV detection [24], which was validated for rat plasma. In brief, plasma was precipitated with acetonitrile, and sodiumhydrogencarbonate and an aqueous solution of trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid were used for derivatization. After acidification, a solution containing heptane and isoamylalcohol was added for extraction of the derivatized sample, and the organic phase was withdrawn and evaporated. The chromatographic separation was achieved by a Discovery C18 column. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile in phosphate buffer and the flow rate was 1 ml/min. The standard curve was linear over the range of 1.7 (CV 6.5%) to 51 μg/ml. Samples with concentrations exceeding the upper limit were diluted and reanalysed. Accuracy for three different concentrations (1.7, 6.9 and 13.7 μg/ml) were −3.3%, 1.3% and 0.5%, respectively (n = 8). Corresponding values for precision were 6.5%, 3.2% and 3.4%.

2.4.3 Non-compartmental analysis

Pharmacokinetic parameters of gabapentin were estimated by means of non-compartmental analysis in the software package WinNonlin version 5.2 (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA), using a mean of four blood sample concentrations for each individual time point. T½ was calculated as ln 2/β, where β is the linear terminal slope of the plasma concentration–time curve. AUC0–∞ was calculated using the trapezoidal rule with extrapolation to infinity. CL/F and V/F, with F being the absolute bioavailability following subcutaneous administration, was calculated from Dose/AUC and CL/β, respectively.

2.5 Drugs and administrations

Gabapentin was generously provided by Teva Pharmaceuticals (Beer Sheva, Israel). Venlafaxine hydrochloride was purchased from Haorui Pharma-Chem Inc. (Edison, NJ, USA). Drugs were dissolved in sterile isotonic saline and administered subcutaneously in dosing volumes of 2–4 ml/kg. Animals were studied up to three times on different occasions, and no animal received the same treatment twice. Experiments were separated by a minimum of four days. The person performing the behavioural tests was blinded to treatment. Ulceration at the site of injection was observed in six (25%) out of 24 animals administered with venlafaxine. Two (8%) of these animals were seriously affected, and were immediately taken out from the study and euthanized.

2.6 Statistical analyses

Data were analysed with non-parametric statistical methods. The Mann–Whitney test, the Wilcoxon test and the Friedman repeated measures one-way ANOVA were used as appropriate and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The area under effect–time curve during the 3 h time course of von Frey testing, AUE0–3 h, was calculated by the trapezoidal rule, and used for analyses of the overall treatment effect in comparison to vehicle.

3 Results

3.1 Response to mechanical stimulation following nerve injury

From a total of 30 SNI-operated animals, 28 (93%) developed hypersensitivity to mechanical von Frey hair stimulation of the lateral side of the hind paw ipsilateral to the nerve injury. The mean withdrawal threshold for the ipsilateral hind paw was 15 ± 1.5 g before SNI-surgery, and decreased to 0.4 ± 0.06 g (p < 0.0001) within 10 days after nerve injury. The withdrawal threshold remained stable during the period of pharmacological testing in all animals.

3.2 Pharmacological effect on mechanical hypersensitivity

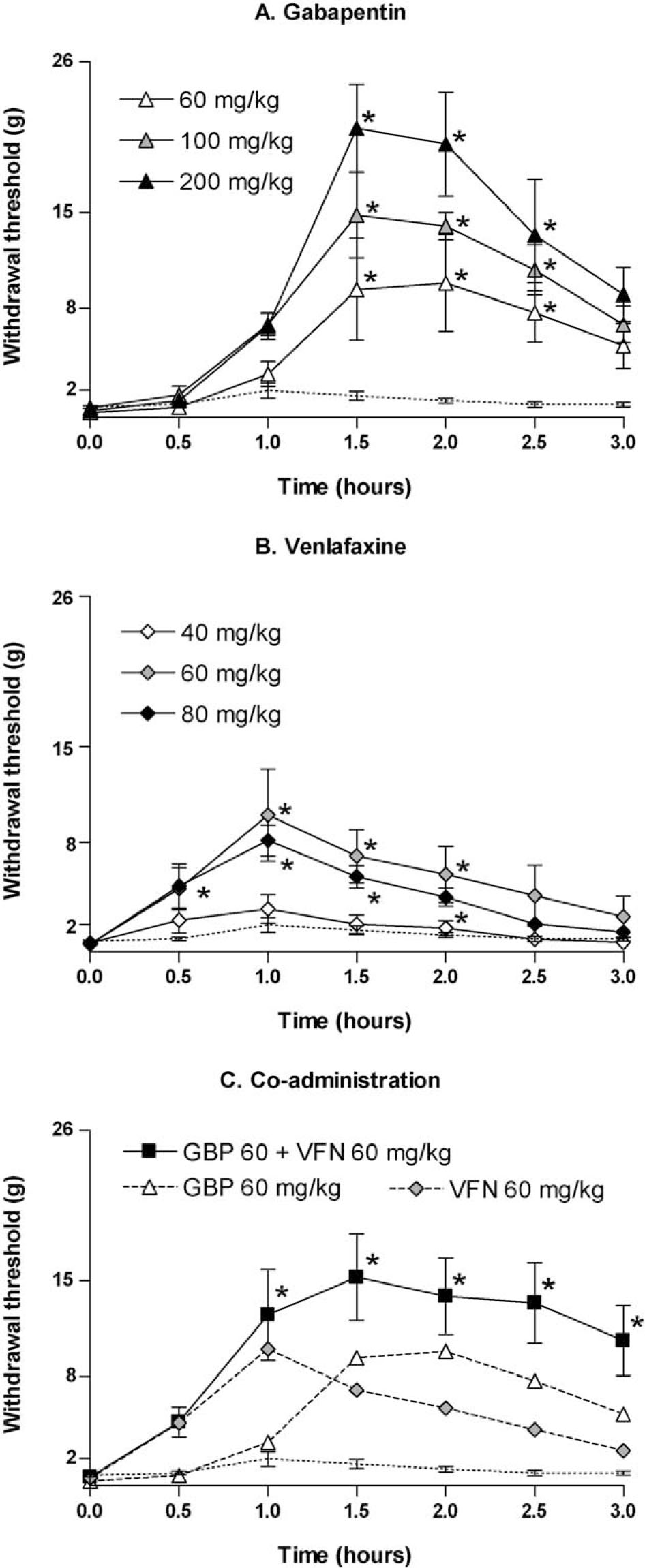

3.2.1 Gabapentin

Gabapentin (60, 100 and 200 mg/kg) dose-dependently reversed hypersensitivity in response to von Frey stimulation (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The overall effect of gabapentin, measured as AUE0–3 h, was significantly better than vehicle at the two highest doses tested (100 mg/kg; p = 0.0007 and 200 mg/kg; p = 0.0002). The time course of effect was typically a delay in the onset of action during the first hour, with maximum effect occurring 1.5–2.5 h following drug administration. During this interval, all doses significantly reduced the mechanical hypersensitivity in comparison to baseline (p < 0.05). Also, all doses produced peak withdrawal thresholds which were significantly different from vehicle (60 mg/kg; p = 0.02, 100 mg/kg; p = 0.0007 and 200 mg/kg; p = 0.0002).

Withdrawal threshold in response to von Frey stimulation to the paw ipsilateral to SNI following subcutaneous administration of (A) gabapentin (60 mg/kg, n = 6; 100 mg/kg, n = 5; 200 mg/kg, n = 6), (B) venlafaxine (40 mg/kg, n = 6; 60 mg/kg, n = 6; 80 mg/kg, n = 8) and (C) co-administered gabapentin and venlafaxine (60 + 60 mg/kg, n = 8). Dotted line represents vehicle (n = 10). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05 vs. time 0 (Friedman repeated measures one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparison test).

Summary of results from the von Frey and the Rotarod tests. Data are presented as mean (SEM).

| Treatment | von Frey test | Rotarod test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| n | AUE0-3h(gh) | Maximum effect (g) | Onset–offset (hours post-dosing) | n | Minimum performance (percentage of baseline) | Onset–offset (hours post-dosing) | |

| Vehicle | 10 | 3.7 (0.6) | 2.1(0.5) | ||||

| Gabapentin | |||||||

| 60 mg/kg | 6 | 16.8 (5.4) ns | 10 (3.5) * | 1.5–2.5 | |||

| 100 mg/kg | 5 | 25.9 (2.7) *** | 16 (2.6) *** | 1.5–2.5 | 6 | 59.8 (16.8) ns | |

| 200 mg/kg | 6 | 33.6 (5.4) *** | 23 (3.0) *** | 1.5–2.5 | 5 | 2.6(0.6) * | <1.0–>3.0 |

| Venlafaxine | |||||||

| 40 mg/kg | 6 | 5.4(1.6) ns | 3.1(1.0) ns | ||||

| 60 mg/kg | 6 | 16.5 (5.5) ** | 10 (3.4) ** | 1.0–2.0 | |||

| 80 mg/kg | 8 | 12.8 (2.2) *** | 8.1(1.1) *** | <0.5–2.0 | 5 | 95.9 (2.5) ns | |

| Co-administration | |||||||

| 60 + 60 mg/kg | 8 | 32.7 (6.9) *** | 16 (3.0) *** | 1.0–>3.0 | 5 | 88.6 (7.0) ns | |

-

von Frey test: “AUE0–3 h” is the area under effect curve during the time course of testing and “Maximum effect” is the peak withdrawal threshold measured at any time point during the testing period; ** p <0.01 and *** p <0.001 vs. vehicle (Mann–Whitney test). “Onset–offset” refers to the time interval where the withdrawal threshold is significantly higher than corresponding value at time 0 (Friedman repeated measures one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple comparison test). Rotarod test: “Minimum performance” is the shortest time on the rod, expressed as percentage of baseline, at any of the time points during the testing period; * p <0.05 vs. baseline (Wilcoxon signed rank test). “Onset–offset” is the time interval where the performance time is significantly shorter than baseline (Wilcoxon signed rank test).

3.2.2 Venlafaxine

Venlafaxine (40, 60 and 80 mg/kg) reduced mechanical hypersensitivity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1andTable. 1), with the two highest doses being significantly better in comparison to vehicle (60 mg/kg; p = 0.008 and 80 mg/kg; p <0.0001). Venlafaxine was characterized by a rapid onset of action, which reached its maximum approximately 1 h after dosing, and returned to baseline levels before the end of the 3 h time course of testing. The withdrawal thresholds were significantly higher than baseline between 1.0 and 2.0 h for 60 mg/kg, and between 0.5 and 2.0 h for 80 mg/kg (p <0.05). The peak withdrawal thresholds achieved from each dose were significantly higher than vehicle for the two highest doses tested (60 mg/kg; p = 0.003 and 80 mg/kg; p = 0.0002), but not for 40 mg/kg.

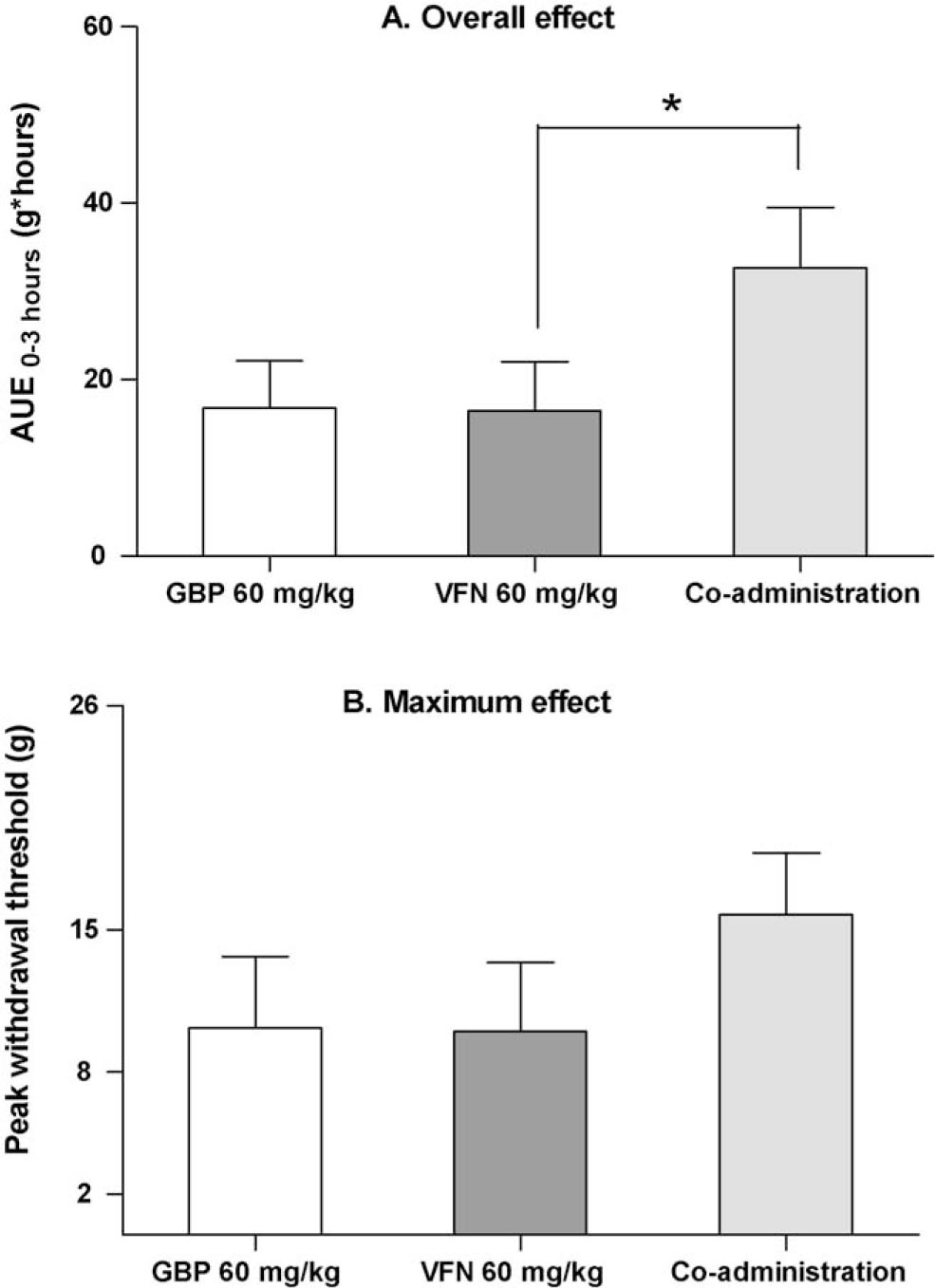

3.2.3 Co-administered gabapentin and venlafaxine

The combination of gabapentin (60 mg/kg) and venlafaxine (60 mg/kg) produced a significant reduction in mechanical hypersensitivity compared to vehicle (Fig. 1Cand table. 1; p <0.0001). The overall effect was also significantly improved compared to venlafaxine 60 mg/kg alone (p <0.02), but not in comparison to gabapentin 60 mg/kg (Fig. 2). The withdrawal thresholds were significantly higher than baseline threshold from 1 h post-dosing until the end of the 3 h testing period (p <0.05), thus, the duration of effect was prolonged as compared to each drug administered alone.

Effect of co-administered gabapentin (60 mg/kg s.c.) and venlafaxine (60 mg/kg s.c.) in the von Frey test, in comparison to each drug administered alone. (A) The overall treatment effect is estimated from the area under effect curve during the time course of testing (AUE0–3 h). (B) The maximum treatment effect is the peak withdrawal threshold measured at any time point during the testing period. Each bar represent mean + SEM. * p <0.05 (Mann–Whitney test).

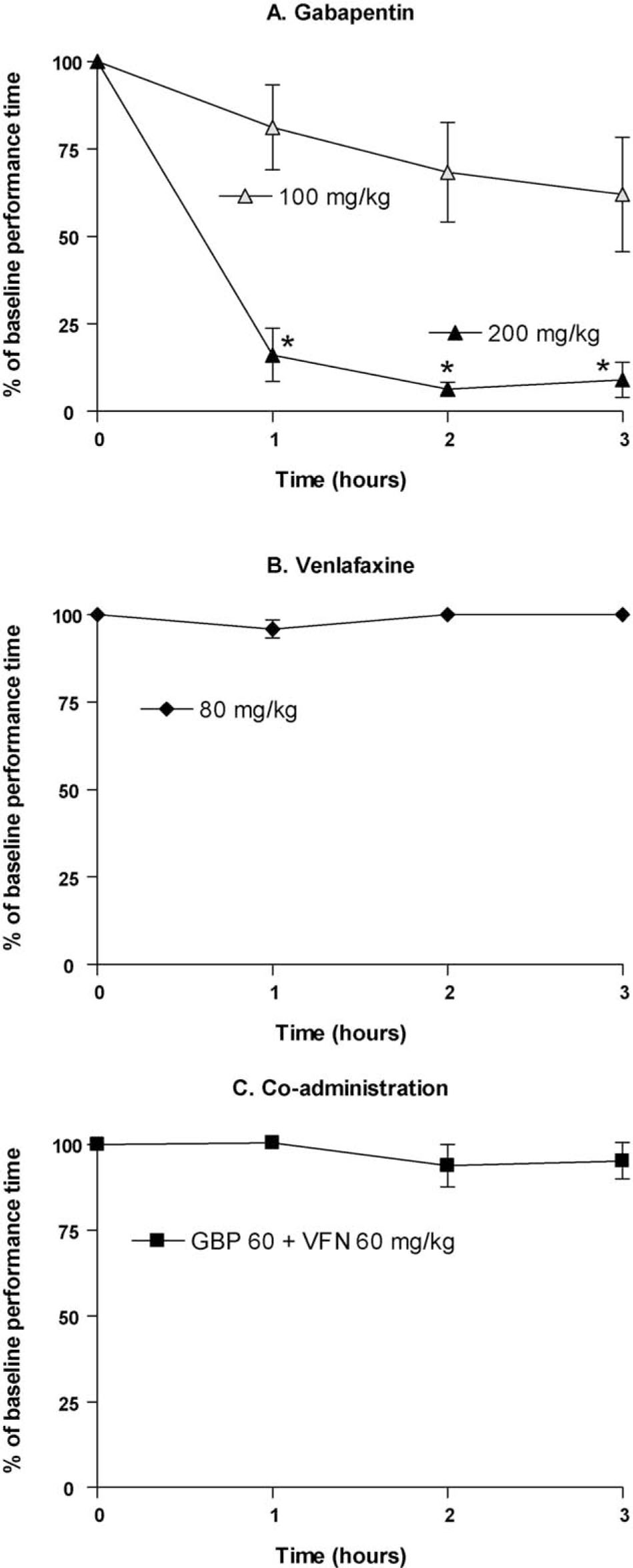

3.3 Treatment-induced ataxia

Administration of gabapentin 100 mg/kg resulted in a trend towards impaired performance in the Rotarod test (Fig. 3Aand Table. 1). This effect increased over the 3 h time course of testing, but did not reach significance in comparison to baseline. Gabapentin 200 mg/kg caused pronounced ataxia with somnolence, which was present at all time points (Fig. 3A and Fig. 1; p <0.05). Neither venlafaxine 80 mg/kg nor the combination of gabapentin and venlafaxine (60 + 60 mg/kg) was associated with reduced performance times in the Rotarod test (Fig. 3B, C and Fig. 1).

Performance time, calculated as percentage of baseline, in the Rotarod test following subcutaneous administration of (A) gabapentin (100 mg/kg, n = 6; 200 mg/kg, n = 5), (B) venlafaxine (80 mg/kg, n = 5) and (C) co-administered gabapentin and venlafaxine (60 + 60 mg/kg, n = 5). Non-SNI animals were used in the test. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * p <0.05 vs. time 0 (Wilcoxon signed rank test).

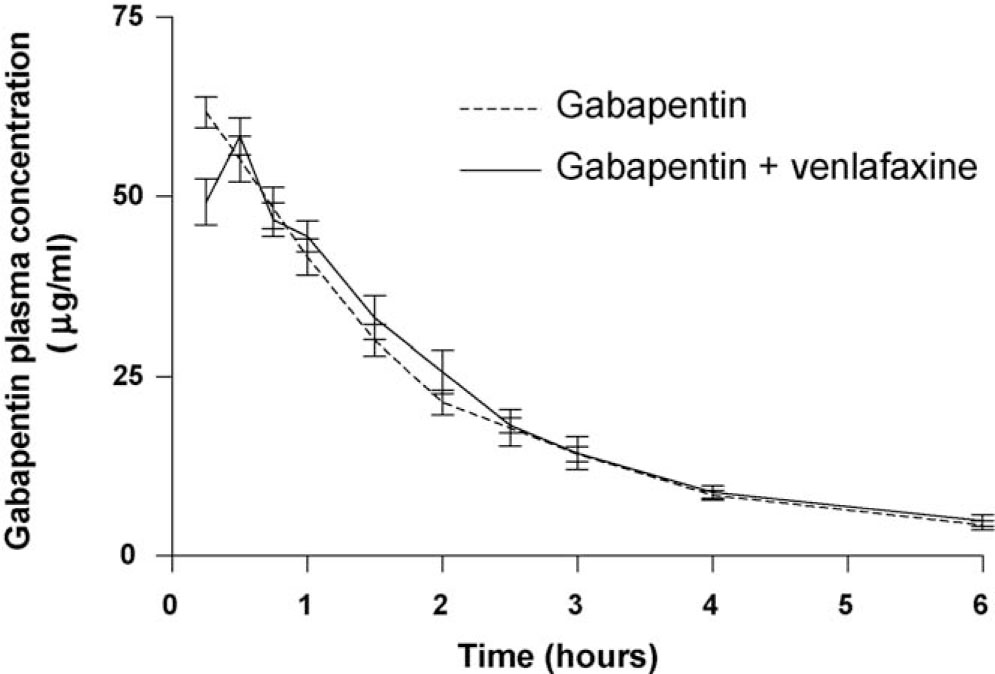

3.4 Effect of venlafaxine on the pharmacokinetics of gabapentin

Following subcutaneous injection of gabapentin (60 mg/kg) in the rat, the drug rapidly reached the systemic circulation with maximum plasma concentrations within 15–30 min. Concomitant administration with venlafaxine (40 mg/kg s.c.) did not alter the plasma concentration–time curve of gabapentin (Fig. 4), and consequently, the pharmacokinetic estimates for gabapentin were almost identical in the two scenarios of presence and absence of venlafaxine (Table. 2).

Plasma concentration–time profile for subcutaneously administered gabapentin (60 mg/kg) in presence (—) and absence (– – –) of co-administered venlafaxine (40 mg/kg s.c.). Data are presented as mean ± SD of four samples.

4 Discussion

Available clinical treatment algorithms for the management of neuropathic pain recommend combination therapy in cases of insufficient efficacy with first-line medications as monotherapy [5, 6]. The pharmacological treatment alternatives for neuropathic pain are limited, and do at most only offer partial pain relief in 50% of the neuropathic pain patients. Therefore, the use of combination pharmacotherapy in the clinic is substantial albeit in absence of evidence from clinical trials on the co-administered drugs [11].

Pharmacokinetics of gabapentin (60 mg/kg s.c.) when administered alone and when co-administered with venlafaxine (40 mg/kg s.c.). The parameters are estimated by means of non-compartmental analysis, and presented as mean only. SD cannot be calculated due to the sparse sampling design.

| Treatment | T½ (h) | AUC0–∞(μg h/ml) | V/F (l/kg) | CL/F (l/h/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gabapentin | 1.7 | 109 | 1.3 | 0.55 |

| Gabapentin + venlafaxine | 1.5 | 111 | 1.2 | 0.54 |

-

Abbreviations: T½= half-life; AUC0–∞ = area under plasma concentration-time curve extrapolated to infinity; CL/F = total, apparent clearance of drug from plasma following subcutaneous administration; V/F = apparent volume of distribution based on drug concentration in plasma following subcutaneous administration.

The potential benefits of combining drugs include improved and prolonged duration of analgesic effect and fewer or milder adverse effects with lower doses of each drug. However, combination therapy might also be complicated by some concerns. Firstly, the risk for pharmacokinetic drug interactions, which may result in reduced effect or increase of unwanted effects, should always be considered before a second drug is added. Secondly, large differences in the duration of the pharmacological effect require different dosing schedules (e.g. dosing twice daily for drug A and three times daily for drug B), which are more difficult to follow and may have a negative impact on patient adherence.

The present study investigated the combination of gabapentin and venlafaxine in the SNI model of neuropathic pain. Encouraging results were obtained when the combination was evaluated for its effect on nerve injury-induced hypersensitivity in the von Frey test:

The overall effect, measured as AUE, was similar to the highest dose of gabapentin tested alone.

The maximum effect was in the same range as the intermediate dose of gabapentin tested alone.

The duration of effect was prolonged in comparison to when gabapentin or venlafaxine were administered alone.

Sedation, dizziness and ataxia are reported as common and dose-limiting adverse effects of gabapentin in the clinic [10]. Furthermore, when performing preclinical studies involving measurements of stimuli-evoked hypersensitivity, these properties may result in an overestimated analgesic effect. Ataxic effects were in this study assessed in the Rotarod test. The highest dose of gabapentin was shown to massively reduce the performance time. Obvious somnolence may further have contributed to the impaired motor function. On the other hand, ataxia or somnolence was not detected for the combination, indicating more reliable results from the von Frey test as well as an improved side effect profile in comparison to equipotent doses of gabapentin.

Taken together, the results from the von Frey and the Rotarod tests indicate that co-administration of gabapentin and venlafaxine, in the doses combined here, provide an additive-like effect on mechanical hypersensitivity, but not on ataxic adverse effects. In order to accurately classify combination effects into additive, antagonistic or synergistic, an isobolographic study design should be applied [25]. Such design is time-consuming and requires a high number of animals to be sacrificed, but may for instance give valuable information on whether an observed combination effect is present over a broad range of dose pairs or only for a specific dose pair of the two drugs. The interpretations made in this study are, however, supported by an isobolographic study in which gabapentin reduced hypersensitivity in an additive manner when combined with the serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor duloxetine [26].

Single drug administration gives no information about effects that may occur following long term exposure, e.g. tolerance development or effect potentiation. In fact, a recently published study reported that gabapentin inhibits excitatory synapse formation in vitro and in vivo [27]; a process which probably occurs within a longer time frame. Thus, a single administration design may not fully reflect the complex mechanism of gabapentin. The new findings are supported by a study, in which repeated intraperitoneal administration of 30 mg/kg gabapentin once a day produced a gradually increasing analgesic effect in spinal cord injured rats [28].

From a pharmacokinetic point of view, gabapentin may be an attractive agent for combination therapy due to its uncomplicated pharmacokinetic profile; the drug is not an inducer or inhibitor of the CYP system, is not metabolised itself and binding to plasma proteins is insignificant [29]. Thus, potential targets for pharmacokinetic interactions with other drugs are few. The pharmacokinetic investigation in this study, performed in the rat, confirmed that neither distribution nor elimination of gabapentin was affected by co-administered venlafaxine. The effect of gabapentin on the pharmacokinetics of venlafaxine was not studied, since any alterations are unlikely to occur on the basis of the pharmacokinetic properties of gabapentin.

By relating the pharmacodynamic and the pharmacokinetic time profiles of gabapentin from this study, an effect delay of approximately 1 h is observed. This delay may be a reflexion of the distribution from the subcutaneous site of administration to the target site, where receptor binding subsequently gives rise to analgesia. Intrathecal and intracerebroventricular administrations of gabapentin have previously resulted in immediate analgesic effects (within 15 min) in nerve injured rats and mice [14, 18].

A previously reported antagonistic interaction on coadministered gabapentin and venlafaxine could not be confirmed in the study [30]. Confoundingly, these studies were performed in the same experimental model (the SNI model), the same route of administration was used (subcutaneous injection) and similar doses were tested. As mentioned above, the results from the pharmacokinetic investigation clearly demonstrated that venlafaxine did not alter the pharmacokinetics of gabapentin, thus a pharmacokinetic explanation as previously suggested for the observed antagonistic interaction is not likely. However, inbred Brown Norwegian rats were used in the first study, while outbred Sprague–Dawley rats were used throughout the present study. A preliminary study where sparse blood samples were drawn from Brown Norwegian rats during the elimination phase of gabapentin only did, however, not show any differences in the pharmacokinetics of gabapentin due to co-administered venlafaxine.

Serotonin and noradrenaline are both substrates in the descending inhibitory pathways, producing anti-nociception. However, serotonin is also active in the descending excitatory pathways, which are pro-nociceptive. The role of serotonin in nociception is not yet fully understood, although recent studies suggest that the net effect of serotonin is pro-nociceptive rather than antinociceptive [31, 32, 33]. Differences in the balance between proand anti-nociceptive effects of serotonin in different rat strains might be an explanation for the diverse study outcomes, but needs further substantiation. Hence, research is required to increase the knowledge about serotonergic actions in nociception; whether the pro-nociceptive and anti-nociceptive actions vary between subjects and its implications for treatment outcome.

The clinical evidence of co-medication with gabapentin and venlafaxine is sparse. The combination has so far only been evaluated for its effect on painful diabetic neuropathy in patients whose pain did not improve with gabapentin monotherapy. This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 8-week clinical trial concluded that patients who received gabapentin plus venlafaxine (n = 6) showed significant improvement in pain reduction, mood disturbance, and quality of life when compared with patients treated with gabapentin plus placebo (n = 6). An uncontrolled follow-up study was later undertaken on 38 patients, resulting in the same conclusion [34]. Another study showed that the combination of gabapentin and the tricyclic antidepressant drug nortriptyline was superior to each drug alone for the treatment of diabetic polyneuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia [35].

In conclusion, the rationale for better effect and less adverse effects through combination therapy with gabapentin and venlafaxine in the management of neuropathic pain is supported by this preclinical study.

DOI of refers to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjpain.2010.01.003.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank laboratory technician Kirsten Metz for supervision of the SNI surgery procedure; animal technician Iben Tangemann Nielsen and laboratory technician Amer Mujezinovic for help with catheter implantations; Ph.D. Jan Borg Rasmussen and bioanalyst Anne Christiansen for assistance during the bioanalythical work; and master students Maria Elgaard, Durita Mortensen and Cathrine Peulicke for performing the preliminary pharmacokinetic study and for validation of the bioanalythical method.

References

[1] Harden N, Cohen M. Unmet needs in the management of neuropathic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;25:S12–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Gilron I, Watson CP, Cahill CM, Moulin DE. Neuropathic pain: a practical guide for the clinician. CMAJ 2006;175:265–75.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Meyer-Rosberg K, Kvarnstrom A, Kinnman E, Gordh T, Nordfors LO, Kristofferson A. Peripheral neuropathic pain—a multidimensional burden for patients. Eur J Pain 2001;5:379–89.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Jensen MP, Chodroff MJ, Dworkin RH. The impact of neuropathic pain on healthrelated quality of life: review and implications. Neurology 2007;68:1178–82.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Attal N, Cruccu G, Haanpaa M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, Nurmikko T, Sampaio C, Sindrup S, Wiffen P. EFNS guidelines on pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Eur J Neurol 2006;13:1153–69.Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, Farrar JT, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS, Kalso EA, Loeser JD, Miaskowski C, Nurmikko TJ, Portenoy RK, Rice ASC, Stacey BR, Treede RD, Turk DC, Wallace MS. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain 2007;132:237–51.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Backonja M, Beydoun A, Edwards KR, Schwartz SL, Fonseca V, Hes M, LaMoreaux L, Garofalo E. Gabapentin for the symptomatic treatment of painful neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280:1831–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Rowbotham M, Harden N, Stacey B, Bernstein P, Magnus-Miller L. Gabapentin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280:1837–42.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Gordh TE, Stubhaug A, Jensen TS, Arnèr S, Biber B, Boivie J, Mannheimer C, Kalliomaki J, Kalso E. Gabapentin in traumatic nerve injury pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over, multi-center study. Pain 2008;138:255–66.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Gilron I. Gabapentin and pregabalin for chronic neuropathic and early postsurgical pain: current evidence and future directions. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2007;20:456–72.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Gilron I, Max MB. Combination pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain: current evidence and future directions. Exp Rev Neurother 2005;5:823–30.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Sutton KG, Martin DJ, Pinnock RD, Lee K, Scott RH. Gabapentin inhibits high-threshold calcium channel currents in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurones. Br J Pharmacol 2002;135:257–65.Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Luo ZD, Calcutt NA, Higuera ES, Valder CR, Song YH, Svensson CI, Myers RR. Injury type-specific calcium channel alpha 2 delta-1 subunit up-regulation in rat neuropathic pain models correlates with antiallodynic effects of gabapentin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002;303:1199–205.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Tanabe M, Takasu K, Kasuya N, Shimizu S, Honda M, Ono H. Role of descending noradrenergic system and spinal alpha2-adrenergic receptors in the effects of gabapentin on thermal and mechanical nociception after partial nerve injury in the mouse. Br J Pharmacol 2005;144:703–14.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Tanabe M, Takasu K, Takeuchi Y, Ono H. Pain relief by gabapentin and pregabalin via supraspinal mechanisms after peripheral nerve injury. J Neurosci Res 2008;86:3258–64.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Takasu K, Honda M, Ono H, Tanabe M. Spinal alpha(2)-adrenergic and muscarinic receptors and the NO release cascade mediate supraspinally produced effectiveness of gabapentin at decreasing mechanical hypersensitivity in mice after partial nerve injury. Br J Pharmacol 2006;148:233–44.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Takeuchi Y, Takasu K, Honda M, Ono H, Tanabe M. Neurochemical evidence that supraspinally administered gabapentin activates the descending noradrenergic system after peripheral nerve injury. Eur J Pharmacol 2007;556:69–74.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Hayashida K, DeGoes S, Curry R, Eisenach JC. Gabapentin activates spinal noradrenergic activity in rats and humans and reduces hypersensitivity after surgery. Anesthesiology 2007;106:557–62.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Hayashida K, Obata H, Nakajima K, Eisenach JC. Gabapentin acts within the locus coeruleus to alleviate neuropathic pain. Anesthesiology 2008;109:1077–84.Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Holliday SM, Benfield P. Venlafaxine. A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic potential in depression. Drugs 1995;49:280–94.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Zimmermann M. Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain 1983;16:109–10.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Decosterd I, Woolf CJ. Spared nerve injury: an animal model of persistent peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain 2000;87:149–58.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Diehl KH, Hull R, Morton D, Pfister R, Rabemampianina Y, Smith D, Vidal JM, van de Vorstenbosch C. A good practice guide to the administration of substances and removal of blood, including routes and volumes. J Appl Toxicol 2001;21:15–23.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Hengy H, Kolle EU. Determination of gabapentin in plasma and urine by high-performance liquid chromatography and pre-column labelling for ultraviolet detection. J Chromatogr 1985;341:473–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Tallarida RJ. An overview of drug combination analysis with isobolograms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2006;319:1–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Hayashida K, Eisenach JC. Multiplicative interactions to enhance gabapentin to treat neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol 2008;598:21–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Eroglu C, Allen NJ, Susman MW, O’Rourke NA, Park CY, Özkan E, Chakraborty C, Mulinyawe SB, Annis DS, Huberman AD, Green EM, Lawler J, Dolmetsch R, Garcia KC, Smith SJ, Luo ZD, Rosenthal A, Mosher DF, Barres BA. Gabapentin receptor alpha2delta-1 is a neuronal thrombospondin receptor responsible for excitatory CNS synaptogenesis. Cell 2009;139:380–92.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Hao JX, Xu XJ, Urban L, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z. Repeated administration of systemic gabapentin alleviates allodynia-like behaviors in spinally injured rats. Neurosci Lett 2000;280:211–4.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Vollmer KO, von HA, Kolle EU. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of gabapentin in rat, dog and man. Arzneimittelforschung 1986;36:830–9.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Rode F, Brolos T, Blackburn-Munro G, Bjerrum OJ. Venlafaxine compromises the antinociceptive actions of gabapentin in rat models of neuropathic and persistent pain. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;187:364–75.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Suzuki R, Rygh LJ, Dickenson AH. Bad news from the brain: descending 5-HT pathways that control spinal pain processing. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2004;25:613–7.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Suzuki R, Rahman W, Rygh LJ, Webber M, Hunt SP, Dickenson AH. Spinal–supraspinal serotonergic circuits regulating neuropathic pain and its treatment with gabapentin. Pain 2005;117:292–303.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Rahman W, Suzuki R, Webber M, Hunt SP, Dickenson AH. Depletion of endogenous spinal 5-HT attenuates the behavioural hypersensitivity to mechanical and cooling stimuli induced by spinal nerve ligation. Pain 2006;123:264–74.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Simpson DA. Gabapentin and venlafaxine for the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2001;3:53–62.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Gilron I, Bailey JM, Tu D, Holden RR, Jackson AC, Houlden RL. Nortriptyline and gabapentin, alone and in combination for neuropathic pain: a double-blind, randomised controlled crossover trial. Lancet 2009.Suche in Google Scholar

Abbreviations

- AUC0–∞

-

area under plasma concentration–time curve extrapolated to infinity.

- AUE0–3 h,

-

area under effect–time curve during the three hour time course of testing.

- CL/F

-

total, apparent clearance of drug from plasma following subcutaneous administration.

- HPLC

-

high performance liquid chromatography.

- SNI

-

spared nerve injury.

- T½

-

terminal half-life of drug in plasma.

- V/F

-

apparent volume of distribution based on drug concentration in plasma following subcutaneous administration.

© 2010 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial comment

- Neuroinflammation explains aspects of chronic pain and opens new avenues for therapeutic interventions

- Review

- Long-term pain, neuroinflammation and glial activation

- Editorial comment

- Long-term pain and disturbed sensation after plastic surgery

- Original experimental

- Hyperesthesia one year after breast augmentation surgery increases the odds for persisting pain at four years A prospective four-year follow-up study

- Editorial comment

- Trismus—An important issue in pain and palliative care

- Review

- Prevention and treatment of trismus in head and neck cancer: A case report and a systematic review of the literature

- Editorial comment

- Why would studies on furry rodents concern us as clinicians?

- Original experimental

- Co-administered gabapentin and venlafaxine in nerve injured rats: Effect on mechanical hypersensitivity, motor function and pharmacokinetics

- Editorial comment

- Why we publish negative studies – and prescriptions on how to do clinical pain trials well

- Effects of perioperative S (+) ketamine infusion added to multimodal analgesia in patients undergoing ambulatory haemorrhoidectomy

- Editorial comment

- Inguinal hernia surgery—A minor surgery that can cause major pain

- Sensory disturbances and neuropathic pain after inguinal hernia surgery

- Letter to the Editor

- Paravertebral block is not safer nor superior to thoracic epidural analgesia

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Editorial comment

- Neuroinflammation explains aspects of chronic pain and opens new avenues for therapeutic interventions

- Review

- Long-term pain, neuroinflammation and glial activation

- Editorial comment

- Long-term pain and disturbed sensation after plastic surgery

- Original experimental

- Hyperesthesia one year after breast augmentation surgery increases the odds for persisting pain at four years A prospective four-year follow-up study

- Editorial comment

- Trismus—An important issue in pain and palliative care

- Review

- Prevention and treatment of trismus in head and neck cancer: A case report and a systematic review of the literature

- Editorial comment

- Why would studies on furry rodents concern us as clinicians?

- Original experimental

- Co-administered gabapentin and venlafaxine in nerve injured rats: Effect on mechanical hypersensitivity, motor function and pharmacokinetics

- Editorial comment

- Why we publish negative studies – and prescriptions on how to do clinical pain trials well

- Effects of perioperative S (+) ketamine infusion added to multimodal analgesia in patients undergoing ambulatory haemorrhoidectomy

- Editorial comment

- Inguinal hernia surgery—A minor surgery that can cause major pain

- Sensory disturbances and neuropathic pain after inguinal hernia surgery

- Letter to the Editor

- Paravertebral block is not safer nor superior to thoracic epidural analgesia