Abstract

Background and objective

Perioperative low-dose ketamine has been useful for postoperative analgesia. In this study we wanted to assess the analgesic effect and possible side-effects of perioperative low-dose S (+) ketamine when added to a regime of non-opioid multimodal pain prophylaxis.

Methods

Seventy-seven patients scheduled for haemorrhoidectomy were enrolled in this randomized, double-blind, controlled study. They received oral paracetamol 1–2 g, total intravenous anaesthesia, intravenous 8 mg dexamethasone, 30 mg ketorolac and local infiltration with bupivacaine/epinephrine. Patients randomized to S (+) ketamine received an intravenous bolus dose of 0.35 mg kg−1 S (+) ketamine before start of surgery followed by continuous infusion of 5 μg kg−1 min−1 until 2 min after end of surgery. Patients in the placebo group got isotonic saline (bolus and infusion). BISTM monitoring was used. Pain intensity and side-effects were assessed by blinded nursing staff during PACU stay and by phone 1, 7 and 90 days after surgery.

Results

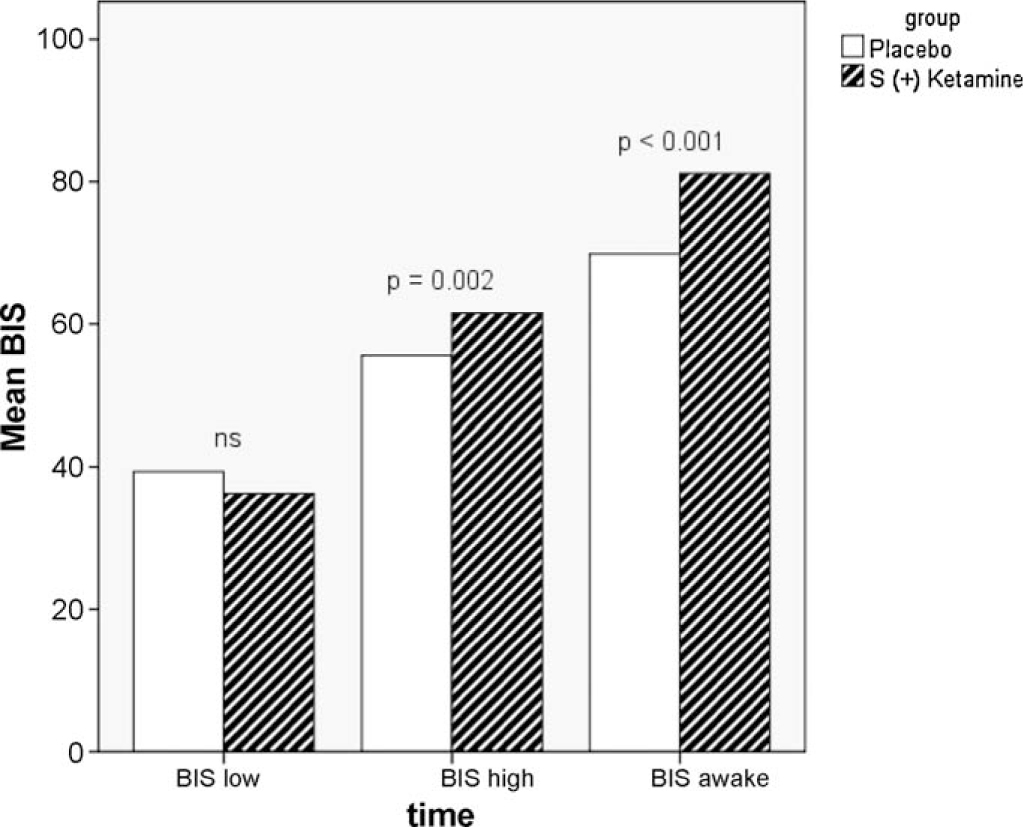

In patients randomized to S (+) ketamine emergence from anaesthesia was significantly longer (13.1 min vs. 9.3 min; p < 0.001). BIS values were significantly higher during anaesthesia (maximal value during surgery: 62 vs. 57; p = 0.01) and when opening eyes (81 vs. 70, p < 0.001). Pain scores (NRS and VAS) did not differ significantly between groups.

Conclusions

The addition of perioperative S (+) ketamine for postoperative analgesia after haemorrhoidectomy on top of multimodal non-opioid pain prophylaxis does not seem to be warranted, due to delayed emergence and recovery, more side-effects, altered BIS readings and absence of additive analgesic effect.

1 Introduction

Multimodal pain treatment improves analgesia and reduces opioid induced side-effects. Multimodal analgesic regimes are common in ambulatory surgery, but there are limited data regarding the comparative effectiveness of different multimodal analgesic combinations [1].

Ketamine can be used as an adjunct in a multimodal pain concept [2]. It interacts with several receptors and ion channels but is mainly an uncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist [3,4]. NMDA receptor block will, to some extent, prevent acute pain. As NMDA receptor mediated plasticity plays an important role in the development of hyperalgesia and chronic pain [3,5,6,7], ketamine may also be beneficial in this context.

Various recently published studies have confirmed the antihyperalgesic effect of low-dose ketamine after major orthopedic or abdominal surgery [8,9,10]. Low-doses of racemic ketamine are defined as an intravenous bolus of less than 1 mg kg−1 and/or continuous intravenous infusion at rates below 20 μg kg−1 min−1 [11]. Still, it is disputed whether perioperative ketamine is useful when only given as a bolus dose or short-term infusion during a short-lasting ambulatory procedure [12,13,14]. Treatment of haemorrhoids in day surgery is a short-lasting procedure but associated with significant postoperative pain [15].

In this study we assessed the usefulness of adding low-dose S (+) ketamine bolus and infusion on top of a multimodal non-opioid regimen in patients undergoing ambulatory haemorrhoidectomy.

2 Materials and methods

The study protocol was approved by the National Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics and the Norwegian Medicines Agency, and the study was registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov.1 Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki in a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled manner and is conform to the CONSORT guidelines [16,17].

Patients scheduled for day-care elective haemorrhoidectomy were enrolled in the period from August 2006 to June 2008. Inclusion criteria were age ? 18 years and ASA grade I + II. Patients with known heart-, liver-, kidney-, or psychiatric disease and patients with a history of gastric ulcer disease, glaucoma or regular use of opioids, as well as pregnant or breast feeding patients were excluded from study participation.

Approximately 1 h before surgery all patients were premedicated with oral paracetamol (weight < 60 kg: 1000 mg; 60–90 kg: 1500 mg; >90 kg: 2000 mg). Total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA) was induced with a bolus dose of propofol (2 mg kg−1) and remifentanil (2 μg kg−1) followed by continuous infusion of propofol (3–7 mg kg−1 h−1) and remifentanil (0.1–0.3 μg kg−1 min−1). BISTM-monitoring (Aspect Medical Systems, Leiden, The Netherlands) was used during anaesthesia. After insertion of a laryngeal mask (BIS ≤ 45) normoventilation with FiO2 0.4 was started. The infusion rate of remifentanil was guided by systolic blood-pressure and heart rate within ±20% of preoperative values. Infusion rate of propofol was guided by BISTM values in a range between 45 and 55. During operation all patients received intravenous 8 mg dexamethasone (Fortecortin®) and 30 mg ketorolac (Toradol®). After completion of surgery the surgeon injected local anaesthesia (10–20 ml bupivacaine 2.5 mg ml−1 + epinephrine 5 μg ml−1) in the surgical field. TIVA was stopped when surgery was finished. BISTM values were registered continuously during anaesthesia (lowest, highest and emergence (when patients opened their eyes)).

Permuted block randomization, blinding and packing of the study medication were performed by the hospital pharmacy. The randomization codes were provided in sealed envelopes which only were opened in case of emergency or after completion of the study protocol of all study participants.

After insertion of laryngeal mask, but before start of surgery, patients in the S (+) ketamine group received an intravenous bolus dose of 0.35 mg kg−1 S (+) ketamine (Pfizer, 2.5 mg ml−1) followed by continuous infusion of 5 μg kg−1 min−1 S (+) ketamine. Patients in the placebo group received an equivalent volume of isotonic saline (bolus and infusion). Identical looking 50 ml syringes were used. For bolus dose and continuous infusion an Alaris®-Asena® infusion pump was used. Continuous infusion was stopped two minutes after end of surgery.

All patients were transferred to the postanaesthetic care unit (PACU) and observed there for at least 1 h. They were observed and evaluated by nursing staff which were blinded to the treatment. Pain intensity was assessed after 15, 30, 60 min and before discharge from PACU using visual analoge scale (VAS, 0–100) and numeric rating scale (NRS, 0–10) for pain. Rescue pain medication was fentanyl 0.05–0.1 mg IV during 0–30 min after end of surgery and paracetamol + codeine (500 mg + 30 mg) orally later on; and was given when VAS > 30, NRS > 3 or upon patient request. At the same time intervals, the patients were asked if they suffered from PONV, hallucinations, diplopia and/or abnormal colour vision. At 30 min after the end of surgery the patients completed the trail making test due to the fact that S (+) ketamine may have potential psychotomimetic side-effects. This is an easily administered test of visual conceptual and visuomotor tracking ability where the patient is asked to connect randomly distributed numbers (from 1 to 25) as fast as possible. This test was used to assess potential cognitive adverse effects of S (+) ketamine.

At discharge from the PACU patients’ grade of satisfaction was registered (satisfied–indifferent–not satisfied) and need of rescue analgesics in the PACU was documented.

In order to treat postoperative pain after hospital discharge, all patients were given an envelope containing five pills diclofenac 50 mg, 14 pills paracetamol 500 mg, seven tablets Pinex Forte® (500 mg paracetamol + 30 mg codeine) and an information letter explaining how the medication should be taken. Paracetamol and diclofenac were used as regular scheduled pain prophylaxis, whereas Pinex Forte® was used for additional need of rescue analgesics at the discretion of the patients.

The patients were interviewed by phone on postoperative day 1, day 7 and 3 months after surgery; assessing pain intensity (NRS), need for analgesics, grade of satisfaction and side-effects (nausea, hallucinations, double and/or abnormal colour vision). On the first postoperative day patients were asked to describe their state when interviewed, whereas during the later phone interviews patients described their mean condition for the last day before the interview was accomplished.

2.1 Statistics

Based on earlier studies we hypothesized a standard deviation of 30% regarding NRS pain intensity and assumed the effect of S (+) ketamine as clinically relevant if it provided 20% better analgesia [18]. Given a type I error of 5% and a power of 80%, the number of patients needed in each treatment arm was calculated to be 36. Compensating for missing data a total of 80 patients was planned for this study. SPSS® (version 16.0) was used for data analysis. Student t-test was used for comparisons of normally distributed data among treatment groups. Mann–Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed data. Non-paramedic variables were analysed with Kruskal–Wallis test and Chi-square test.

Demographic data.

| Variable | Placebo, N=38 | S (+) ketamine, N=39 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 50.2(11.4) | 46.4(11.6) |

| Sex (male/female), n | 15/23 | 17/22 |

| Height (cm) | 172(10.3) | 172(9.1) |

| Weight (kg) | 74.0(15.1) | 72.6(11.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.9 (3.7) | 24.6 (3.4) |

| Heart rate preoperatively (beats/min) | 68(13.3) | 70(15.8) |

| Systolic blood pressure preoperatively (mmHg) | 139(21.7) | 142(21.6) |

| Diastolic blood pressure preoperatively (mmHg) | 83(11.2) | 84(12.3) |

| ASA classification (I/II) | 18/20 | 24/15 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 17.4(7.1) | 20.3 (9.5) |

-

Data are means or numbers. Values in parentheses indicate SD. No significant differences between the groups were found (independent samples t-test and Chi-square test). BMI = Body mass index, ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists.

3 Results

3.1 Demographic data and patient flow

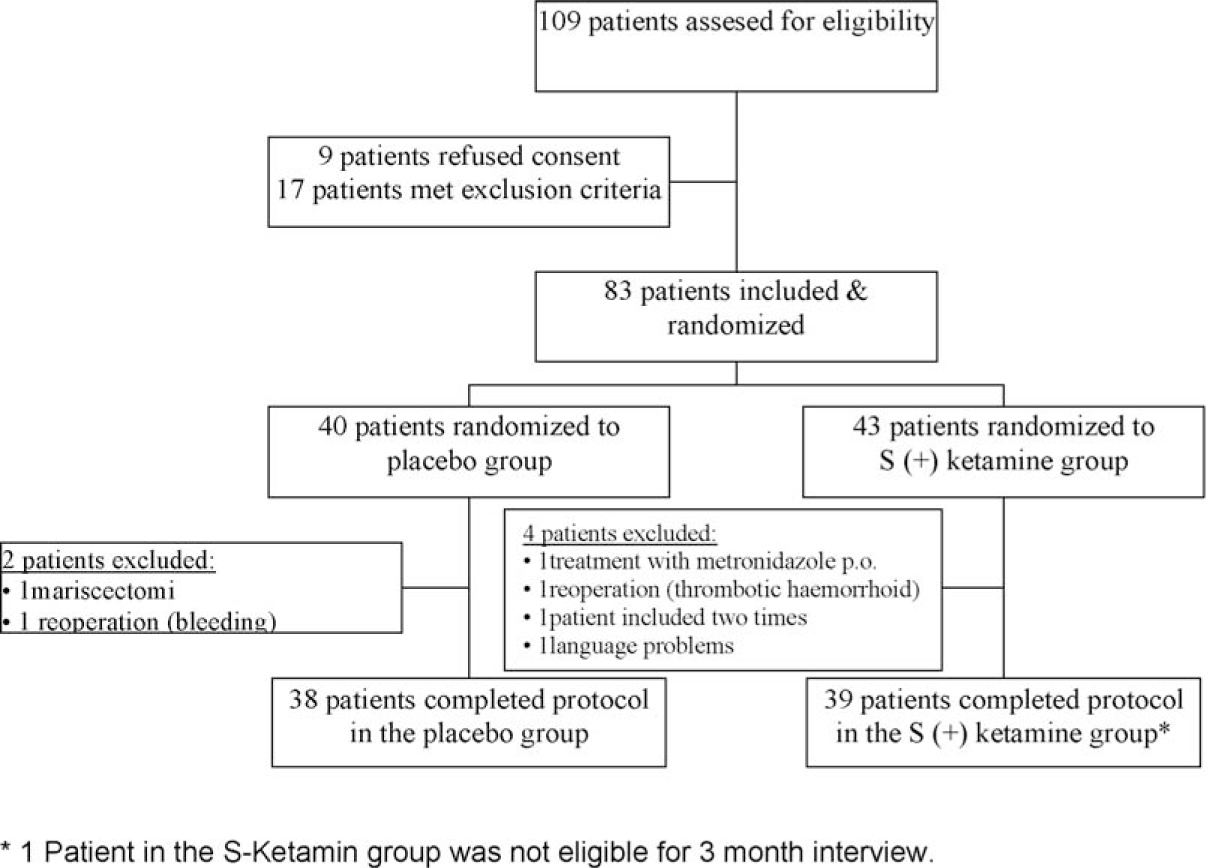

The two study groups had a similar distribution of sex, age, weight, height and ASA classification. Preoperatively measured heart rate, blood pressure and duration of surgery did not differ significantly between groups (Table 1). A total of 83 patients scheduled for elective haemorrhoidectomy were randomized to either treat ment with placebo or S (+) ketamine. Six of these patients (two from the placebo group and four from the S (+) ketamine group) were withdrawn from statistical analyses due to following reasons: One patient was treated with mariscectomy only instead of haemorrhoidectomy, two patients needed reoperation (one due to bleeding, one due to thrombotic haemorrhoids), one patient was treated with oral metronidazole for 10 days postoperatively (to prevent pain), one patient was by accident included twice into the study and one patient with immigrant background was unable to communicate (Fig. 1).

Patient flow chart according to the CONSORT guidelines.

BIS values measured during anaesthesia: BIS low = lowest BIS value (mean) for the different groups. BIS high = highest BIS value (mean) for the different groups. BIS awake = BIS value (mean) for the different groups when patients opened their eyes upon emergence from anaesthesia.

3.2 Perioperative period

In patients randomized to S (+) ketamine, time from finished surgery to removal of the laryngeal mask was significantly longer (13.1 min vs. 9.3 min, p < 0.001) and BISTM values were significantly higher during anaesthesia (maximal value during surgery: 62 vs. 57, p = 0.002) and when opening eyes (81 vs. 70, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The total dose of propofol was higher in patients treated with S (+) ketamine (propofol 388 mg vs. 328 mg, p = 0.02).

3.3 PACU period

Pain scores (NRS and VAS) did not differ significantly between the groups during the PACU period (Table 2). Less than 10% of the patients had worst VAS ? 30 or NRS ? 3. Five patients in the placebo group and four patients in the S (+) ketamine group needed rescue medication for pain relief (fentanyl i.v. or paracetamol/codeine p.o.). Side-effects were not significantly more frequent in patients who were treated with S (+) ketamine: Six patients reported diplopia (vs. one patient in the placebo group; ns, p = 0.052) and one patient complained about abnormal colour vision 15 min after arrival at PACU. All of these patients had normal vision at discharge. None of the study participants experienced hallucinations. Four patients in the placebo group and two patients in S (+) ketamine group complained about nausea. There was no time difference in completing the trail making test (39 s (placebo) vs. 44 s (S (+) ketamine), ns, p = 0.17). Participants randomized to placebo were discharged significantly earlier from PACU (74 min vs. 87 min, p = 0.03). All patients were satisfied with pain management during PACU stay.

Pain scores.

| Time after surgery | S (+) ketamine NRS | Placebo NRS |

|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 1.5 (1.4) | 0.9 (1.6) |

| 30 min | 1.7 (1.5) | 1.1 (1.4) |

| Discharge PACU | 1.4 (1.2) | 1.0 (1.2) |

| 1 day po rest | 1.4 (1.4) | 0.9 (1.3) |

| 1 day po sitting | 1.4 (1.6) | 1.3 (1.6) |

| 1 day po defecation | 1.6 (2.1) | 1.5 (1.7) |

| 1 week po rest | 1.8 (2.0) | 1.6 (2.4) |

| 1 week po sitting | 2.6 (2.3) | 2.3 (2.6) |

| 1 week po defecation | 6.2 (2.8) | 4.8 (3.4) |

| 3 months po rest | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.1 (0.7) |

| 3 months po sitting | 0.1 (0.6) | 0.2(1.1) |

| 3 months po defecation | 1.1 (2.2) | 0.9 (2.3) |

-

Data are means. Values in parentheses indicate SD. No significant differences between the groups were found (independent samples t-test). NRS = numeric rating scale (0-10), PACU = post anaesthetic care unit, po = postoperative.

3.4 Interview after 24 h

The pain scores (NRS) reported by phone about 24 h after hospital discharge did not differ significantly between the groups (Table 2). Only six patients in each group had NRS ? 3 for worst pain. Patients in the placebo group complained more frequently about PONV (7 patients vs. 3 patients in group K; ns, p = 0.17). All patients in both groups were satisfied with the pain management and none of them reported side-effects like diplopia or hallucinations.

3.5 Interview after 7 days

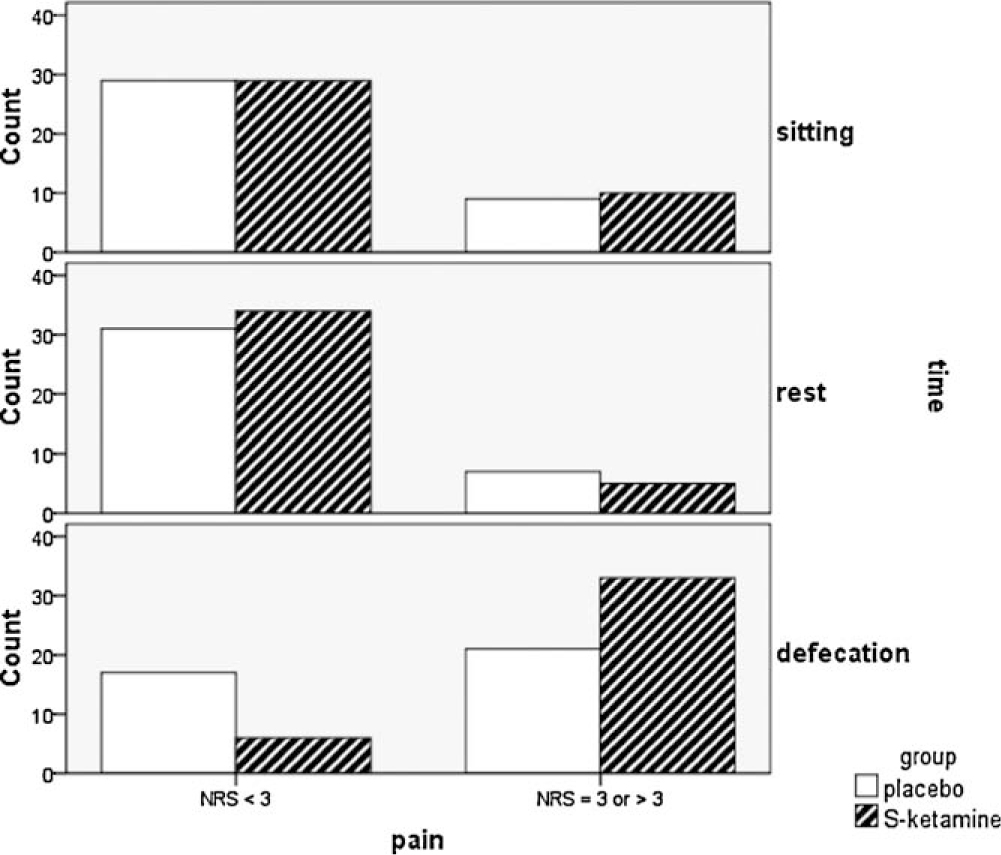

The pain scores (worst NRS during the sixth postoperative day) reported by phone 7 days after hospital discharge did not differ significantly between the groups but were markedly higher than reported in the previous interviews (Table 2). This was mainly due to reports of pain during defecation (Fig. 3). None of the study participants reported side-effects like diplopia or hallucinations. Four patients in the placebo group and five in the S (+) ketamine group reported PONV. Seven days after surgery three patients in the placebo group and five in the S (+) ketamine group were dissatisfied with the pain management.

3.6 Interview after 3 months

Analyses showed no statistical significant differences between the study groups concerning pain (NRS) (Table 2). The majority of all study patients had no pain at all during the day before the interview was accomplished. Three patients in the placebo group and six patients in S (+) ketamine group reported worst NRS ? 3. Eleven patients were not satisfied with the management of pain (five of these patients were treated with placebo, six patients with S (+) ketamine).

Results from phone interview 7 days after surgery. Number of patients reporting pain in different situations: sitting position, at rest and during defecation (numeric rating scale–NRS).

4 Discussion

Several systematic reviews have shown that subanaesthetic doses of racemic ketamine and S (+) ketamine may reduce the intensity of postoperative pain and the consumption of opioids [11,19,20,21,22].

However, in our study, when subanaesthetic doses of S (+) ketamine bolus and infusion were added on top of a multimodal perioperative analgesic treatment, there was no reduction in pain after haemorrhoidectomy. The use of S (+) ketamine resulted in a significantly prolonged time for emergence after end of surgery, an increased incidence of visual disturbance in the PACU and a prolonged stay in the PACU.

The absence of immediate analgesic effect in our study may be due to a low number of patients complaining about moderate to severe postoperative pain (VAS ? 30 or NRS ? 3) in both groups and this is an important limitation when we discuss the effect of adding S (+) ketamine for the immediate postoperative pain. This may be explained by the fact that all patients were treated with a multimodal non-opioid pain regime including premedication with adequate doses paracetamol and that all patients received intraoperatively both intravenous dexamethasone and ketorolac. In addition the surgeon injected local anaesthesia with epinephrine at the end of surgery. A recently published study in patients who underwent uterine artery embolization and where patients were treated with adjunctive paracetamol and diclofenac, also showed no additive effect of racemic ketamine [23]. In contrast Kwok et al., demonstrated that a single dose of racemic ketamine (0.15 mg ml−1) before incision for gynaecologic laparo-scopic surgery reduced pain scores significantly in the first 6 h after surgery. Patients in their study received neither paracetamol, steroids, NSAIDs nor local or epidural anaesthesia before or during anaesthesia [24]. The absence of proper prophylactic or preventive analgesia may explain the beneficial effect of a low-dose of racemic ketamine in their study. While the initial pain in our study was low, our patients in the control group had clinically significant pain after 1 week (mean 4.8 on the NRS). Although there is a potential for improving this figure, the S (+) ketamine adjunct did not in any way add any analgesia at this point with a mean value of 6.2 (ns from placebo).

Absence of analgesic effect in our study may also be due to low dosage given. Our dosing of S (+) ketamine periopertively was according to the recommendations by Himmelseher and Durieux [7] who proposed the use of a bolus dose before incision of 0.20–0.35 mg kg−1 followed by continuous infusion of 200–400 μg kg−1 h−1. The S (+) ketamine doses we used were probably adequate, as side-effects were observed more frequently in the S (+) ketamine group.

When regarding the preventive analgesic effect of racemic ketamine and S (+) ketamine, it has been shown that racemic ketamine can either be administered before incision or at the end of surgery, and that both ways may have a positive effect [25], although some studies are negative [26,27]. Stubhaug et al. [28] demonstrated that a combination of preincisional bolus dose of racemic ketamine followed by continuous infusion for 48 h can suppress central sensitization and postoperative hyperalgesia, although the subjective experience of pain intensity was unaltered.

In our study S (+) ketamine was administered as a bolus dose before surgery followed by continuous infusion throughout surgery and we could not demonstrate a reduction in pain scores 1 week or 3 months after surgery, compared with placebo. One reason for our negative findings may be that we stopped the S (+) ketamine infusion at the end of surgery and did not continue S (+) ketamine in the postoperative period. However, continued S (+) ketamine infusion postoperatively is not optimal in the day surgery setting as sedation may occur and delay the discharge readiness.

In our study, there was no effect of perioperative S (+) ketamine on late, often strong, postoperative pain associated with defecation during the first week postoperatively. This is acute pain, initiated by secondary stretching and tissue trauma. Moderate to high pain scores several days after haemorrhoidectomy have been reported earlier by several research groups [15,29,30] and the addition of S (+) ketamine did not reduce pain in our study.

Furthermore we could not demonstrate a preventive analgesic effect of S (+) ketamine regarding the development of chronic postoperative pain as measured 3 months after surgery. More than 10% of all our patients reported NRS ? 3. Our results are comparable to the findings of Katz et al. [31] who studied the effect of low-dose racemic ketamine for radical prostatectomy and found an overall incidence of pain of 10.5% at a 6-month follow-up interview. A recently published review estimated that the incidence of persistent pain after common operations is about 10–50% [32].

Another possible explanation is that NMDA receptor activation becomes more important with persistent nociceptive input [3]. The hypothesis that NMDA receptors are not activated during shortlasting pain is strengthened by several studies showing the absence of effect from sub-anaesthetic doses of racemic ketamine for tonsillectomy, where the surgical procedures lasted between 15 and 43 min [12,13,14].

As shown, we found negative effects of S (+) ketamine, both time for emergence after end of surgery and stay in the PACU were prolonged. This may be due to a slightly higher dose of propofol in the S (+) ketamine group, as dose need based on BIS values is more difficult to evaluate when S (+) ketamine is used. Delay of emergence increases the need for resources in the operation theatre and during the postoperative stay, and is especially unfavourable in day-care surgery with high patient turnover. Mathisen et al. [33] published similar findings for R (−) ketamine where extubation time was delayed and time to eyes opening after anaesthesia was nearly doubled in the R (−) ketamine groups.

We observed that diplopia 15 min after emergence from anaesthesia was more frequent in patients who were treated with S (+) ketamine. However, our patients described these impairments of vision as mild and short-lasting and none of the study participants reported hallucinations.

Lahtinen et al. [34] observed that seven of 54 patients receiving 2.5 μg kg−1 min−1 S (+) ketamine infusion developed major psychotomimetic adverse responses, vs. none in the placebo group. In contrast to our study their S (+) ketamine infusion was continued for 48 h after surgery. It has also been demonstrated that a subanaesthetic dose of racemic ketamine can result in a greater incidence of unpleasant dreams during the first three nights after infusion [35]. In our study none of the patients reported nightmares in the interviews made at 1 and 7 days after surgery.

The use of S (+) ketamine may compromise anaesthesia depth monitoring. Although the necessity of EEG monitoring may be questioned for short-lasting, non-curarized procedures; our study shows that even a small supplement of S (+) ketamine resulted in higher BIS readings during anaesthesia and a higher BIS value upon emergence, despite of higher propofol doses in the S (+) ketamine group.

These findings are comparable which other studies [36,37] although Faraoni et al. [38] recently stated that racemic ketamine had no effect on bispectral index during stable propofolremifentanil anaesthesia. In their study only a bolus dose of less potent racemic ketamine (0.2 mg kg−1) was administered over a 5-min period, whereas in our study 0.35 mg kg−1 S (+) ketamine were given over a 90-s period followed by infusion.

In conclusion, the addition of low-dose perioperative S (+) ketamine for postoperative analgesia after haemorrhoidectomy added to a multimodal non-opioid pain prophylaxis does not seem to be warranted. There is no extra analgesic effect from S (+) ketamine in this setting, intravenous anaesthetic dosing is more difficult to titrate, emergence and recovery from anaesthesia are delayed and side-effects occur more frequently. Low-dose S (+) ketamine significantly disturbs the BIS response at standardized clinical states.

DOI of refers to article: 10.1016/j.sjpain.2010.01.009.

Acknowledgements

We thank our research nurse Elisabet Andersson and our pain nurses Helena Blom and Lena Windingstad for good support during the study. The study has been financed by institutional means.

-

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest has been declared.

References

[1] Schug SA, Chong C. Pain management after ambulatory surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2009;22:738–43.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Suzuki M. Role of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonists in postoperative pain management. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2009;22:618–22.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Chizh BA. Low dose ketamine: a therapeutic and research tool to explore N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-mediated plasticity in pain pathways. J Psychopharmacol 2007;21:259–71.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Lois F, De Kock MF. Something new about ketamine for pediatric anesthesia? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2008;21:340–4.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Guirimand F, Dupont X, Brasseur L, Chauvin M, Bouhassira D. The effects of ketamine on the temporal summation (wind-up) of the R(III) nociceptive flexion reflex and pain in humans. Anesth Analg 2000;90:408–14.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Petrenko AB, Yamakura T, Baba H, Shimoji K. The role of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in pain: a review. Anesth Analg 2003;97:1108–16.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Himmelseher S, Durieux ME. Ketamine for perioperative pain management. Anesthesiology 2005;102:211–20.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Webb AR, Skinner BS, Leong S, Kolawole H, Crofts T, Taverner M, Burn SJ. The addition of a small-dose ketamine infusion to tramadol for postoperative analgesia: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized trial after abdominal surgery. Anesth Analg 2007;104:912–7.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Aveline C, Gautier JF, Vautier P, Cognet F, Hetet HL, Attali JY, Leconte V, Leborgene P, Bonnet F. Postoperative analgesia and early rehabilitation after total knee replacement: a comparison of continuous low-dose intravenous ketamine versus nefopam. Eur J Pain 2008;13:613–9.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Zakine J, Samarcq D, Lorne E, Moubarak M, Montravers P, Beloucif S, Dupont H. Postoperative ketamine administration decreases morphine consumption in major abdominal surgery: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Anesth Analg 2008;106:1856–61.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Schmid RL, Sandler AN, Katz J. Use and efficacy of low-dose ketamine in the management of acute postoperative pain: a review of current techniques and outcomes. Pain 1999;82:111–25.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Van Elstraete AC, Lebrun T, Sandefo I, Polin B. Ketamine does not decrease postoperative pain after remifentanil-based anaesthesia for tonsillectomy in adults. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2004;48:756–60.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Batra YK, Shamsah M, Al-Khasti MJ, Rawdhan HJ, Al-Qattan AR, Belani KG. Intraoperative small-dose ketamine does not reduce pain or analgesic consumption during perioperative opioid analgesia in children after tonsillectomy. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007;45:155–60.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Abu-Shahwan I. Ketamine does not reduce postoperative morphine consumption after tonsillectomy in children. Clin J Pain 2008;24:395–8.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Stolfi VM, Sileri P, Micossi C, Carbonaro I, Venza M, Gentileschi P, Rossi P, Falchetti A, Gaspari A. Treatment of hemorrhoids in day surgery: stapled hemorrhoidopexy vs Milligan–Morgan hemorrhoidectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:795–801.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet 2001;357:1191–4.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, Gotzsche PC, Lang T. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:663–94.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Liu SS, Wu CL. The effect of analgesic technique on postoperative patient-reported outcomes including analgesia: a systematic review. Anesth Analg 2007;105:789–808.Search in Google Scholar

[19] McCartney CJ, Sinha A, Katz J. A qualitative systematic review of the role of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonists in preventive analgesia. Anesth Analg 2004;98:1385–400.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Subramaniam K, Subramaniam B, Steinbrook RA. Ketamine as adjuvant analgesic to opioids: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review. Anesth Analg 2004;99:482–95.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Elia N, Tramer MR. Ketamine and postoperative pain—a quantitative systematic review of randomised trials. Pain 2005;113:61–70.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Bell RF, Dahl JB, Moore RA, Kalso E. Peri-operative ketamine for acute post-operative pain: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review (Cochrane review). Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2005;49:1405–28.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Jensen LL, Handberg G, Helbo-Hansen HS, Skaarup I, Lohse T, Munk T, Lund N. No morphine sparing effect of ketamine added to morphine for patient-controlled intravenous analgesia after uterine artery embolization. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2008;52:479–86.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Kwok RF, Lim J, Chan MT, Gin T, Chiu WK. Preoperative ketamine improves postoperative analgesia after gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. Anesth Analg 2004;98:1044–9.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Menigaux C, Fletcher D, Dupont X, Guignard B, Guirimand F, Chauvin M. The benefits of intraoperative small-dose ketamine on postoperative pain after anterior cruciate ligament repair. Anesth Analg 2000;90:129–35.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Dahl V, Ernoe PE, Steen T, Raeder JC, White PF. Does ketamine have preemptive effects in women undergoing abdominal hysterectomy procedures? Anesth Analg 2000;90:1419–22.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Burstal R, Danjoux G, Hayes C, Lantry G. PCA ketamine and morphine after abdominal hysterectomy. Anaesth Intensive Care 2001;29:246–51.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Stubhaug A, Breivik H, Eide PK, Kreunen M, Frey K. Mapping of punctate hyper-algesia around a surgical incision demonstrates that ketamine is a powerful suppressor of central sensitization to pain following surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1997;41:1124–32.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Rowsell M, Bello M, Hemingway DM. Circumferential mucosectomy (stapled haemorrhoidectomy) versus conventional haemorrhoidectomy: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000;355:779–81.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Mehigan BJ, Monson JR, Hartley JE. Stapling procedure for haemorrhoids versus Milligan–Morgan haemorrhoidectomy: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000;355:782–5.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Katz J, Schmid R, Snijdelaar DG, Coderre TJ, McCartney CJ, Wowk A. Preemptive analgesia using intravenous fentanyl plus low-dose ketamine for radical prostatectomy under general anesthesia does not produce short-term or long-term reductions in pain or analgesic use. Pain 2004;110: 707–18.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet 2006;367:1618–25.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Mathisen LC, Aasbo V, Raeder J. Lack of pre-emptive analgesic effect of (R)-ketamine in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 1999;43:220–4.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Lahtinen P, Kokki H, Hakala T, Hynynen M. S(+)-ketamine as an analgesic adjunct reduces opioid consumption after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg 2004;99:1295–301.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Blagrove M, Morgan CJ, Curran HV, Bromley L, Brandner B. The incidence of unpleasant dreams after sub-anaesthetic ketamine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;203:109–20.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Vereecke HE, Struys MM, Mortier EP. A comparison of bispectral index and ARX-derived auditory evoked potential index in measuring the clinical interaction between ketamine and propofol anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2003;58: 957–61.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Joly V, Richebe P, Guignard B, Fletcher D, Maurette P, Sessler DI, Chauvin M. Remifentanil-induced postoperative hyperalgesia and its prevention with small-dose ketamine. Anesthesiology 2005;103:147–55.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Faraoni D, Salengros JC, Engelman E, Ickx B, Barvais L. Ketamine has no effect on bispectral index during stable propofol-remifentanil anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 2009;102:336–9.Search in Google Scholar

© 2010 Scandinavian Association for the Study of Pain

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial comment

- Neuroinflammation explains aspects of chronic pain and opens new avenues for therapeutic interventions

- Review

- Long-term pain, neuroinflammation and glial activation

- Editorial comment

- Long-term pain and disturbed sensation after plastic surgery

- Original experimental

- Hyperesthesia one year after breast augmentation surgery increases the odds for persisting pain at four years A prospective four-year follow-up study

- Editorial comment

- Trismus—An important issue in pain and palliative care

- Review

- Prevention and treatment of trismus in head and neck cancer: A case report and a systematic review of the literature

- Editorial comment

- Why would studies on furry rodents concern us as clinicians?

- Original experimental

- Co-administered gabapentin and venlafaxine in nerve injured rats: Effect on mechanical hypersensitivity, motor function and pharmacokinetics

- Editorial comment

- Why we publish negative studies – and prescriptions on how to do clinical pain trials well

- Effects of perioperative S (+) ketamine infusion added to multimodal analgesia in patients undergoing ambulatory haemorrhoidectomy

- Editorial comment

- Inguinal hernia surgery—A minor surgery that can cause major pain

- Sensory disturbances and neuropathic pain after inguinal hernia surgery

- Letter to the Editor

- Paravertebral block is not safer nor superior to thoracic epidural analgesia

Articles in the same Issue

- Editorial comment

- Neuroinflammation explains aspects of chronic pain and opens new avenues for therapeutic interventions

- Review

- Long-term pain, neuroinflammation and glial activation

- Editorial comment

- Long-term pain and disturbed sensation after plastic surgery

- Original experimental

- Hyperesthesia one year after breast augmentation surgery increases the odds for persisting pain at four years A prospective four-year follow-up study

- Editorial comment

- Trismus—An important issue in pain and palliative care

- Review

- Prevention and treatment of trismus in head and neck cancer: A case report and a systematic review of the literature

- Editorial comment

- Why would studies on furry rodents concern us as clinicians?

- Original experimental

- Co-administered gabapentin and venlafaxine in nerve injured rats: Effect on mechanical hypersensitivity, motor function and pharmacokinetics

- Editorial comment

- Why we publish negative studies – and prescriptions on how to do clinical pain trials well

- Effects of perioperative S (+) ketamine infusion added to multimodal analgesia in patients undergoing ambulatory haemorrhoidectomy

- Editorial comment

- Inguinal hernia surgery—A minor surgery that can cause major pain

- Sensory disturbances and neuropathic pain after inguinal hernia surgery

- Letter to the Editor

- Paravertebral block is not safer nor superior to thoracic epidural analgesia