Abstract

Ternary rare earth metal-rich intermetallic phases containing osmium and magnesium were obtained by induction melting of the elements in sealed niobium ampoules under argon followed by annealing in muffle furnaces. The large rare earth elements form the series of Gd4RhIn-type (F4̅3m) intermetallics RE4OsMg with RE = La–Nd and Sm, while the smaller rare earth metals gadolinium and terbium form the Y9CoMg4-type (P63/mmc) phases Gd9OsMg4 and Tb9OsMg4. All samples were characterized by X-ray powder diffraction (Guinier technique). The structures of Ce4Os0.973Mg1.027 (a = 1406.54(7) pm, wR2 = 0.0478), Nd4Os0.978Mg1.022 (a = 1402.00(7) pm, wR2 = 0.0463), Sm4Os0.920Mg1.080 (a = 1387.33(5) pm, wR2 = 0.0378) and Gd9OsMg4 (a = 971.01(5), c = 980.43(5) pm, wR2 = 0.0494) were refined from single-crystal X-ray diffractometer data. The three RE4OsMg phases show small degrees of Os/Mg mixing, as is frequently observed for Rh/In in Gd4RhIn-type intermetallics. The basic building units in both structures are osmium-centered RE6 trigonal prisms that are condensed with empty RE6 octahedra. The magnesium atoms in both types build Mg4 tetrahedra. The latter are isolated (312 pm Mg–Mg in Ce4OsMg) and incorporated within the three-dimensional network of prisms and octahedra in the RE4OsMg phases while one observes rows of corner- and face-sharing tetrahedra in Gd9OsMg4 (305 and 314 pm Mg–Mg). In both structure types direct Os–Mg bonding is not observed.

1 Introduction

Osmium is one of the high-melting and chemically very inert transition metals. This is reflected in the binary phase diagrams. So far no binary compounds have been reported with magnesium, zinc, cadmium, indium, thallium, lead and bismuth [1]. It is obvious, that this concerns mainly the low-melting main group metals as well as zinc and cadmium. Such empty binary phase diagrams have a large influence on the ternary ones. It is empirically known that the ternary phase diagrams mostly exhibit only few phases if the binary diagrams show few or none and vice versa.

The ternary phase diagrams RE-T-Mg and RE-T-Cd (RE=rare earth metal; T=electron-rich transition metal) contain a huge number of compounds [2], [3]; however, so far no representatives with osmium were known. Recent phase analytical studies in these systems with osmium revealed a series of ternary phases RE4OsCd (RE=La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd) [4], RE9OsMg4 (RE=Y, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, Lu) [5] and RE10OsCd3 (RE=Y, Sm, Gd–Tm, Lu) [4]. There seems to be a simple crystal chemical feature that enables formation of such ternary osmium-based compounds. In these rare earth-rich phases osmium and magnesium (cadmium) are separated in different polyhedra: osmium within trigonal rare earth prisms besides tetrahedral Cd4 or triangular Cd3 clusters, respectively rows of corner- and face-sharing Mg4 tetrahedra. These magnesium and cadmium substructures are rare structural motifs in both solid state and molecular compounds.

The missing magnesium-based representatives with the light rare earth metals have now been synthesized and structurally characterized. Herein we report on the Gd4RhIn-type series RE4OsMg with RE=La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm and the Y9CoMg4-type phases Gd9OsMg4 and Tb9OsMg4.

2 Experimental

2.1 Synthesis

Starting materials for the syntheses of the RE9OsMg4 and RE4OsMg samples were ingots of the sublimed rare earth elements (Smart elements or Onyxmet, >99.9%), osmium powder (Merck, 99.9%), and a magnesium rod (Sigma-Aldrich, 99.98%), all with metal-based stated purities. The early rare earth elements which are sensitive to moisture were stored under dry argon in Schlenk tubes. The large magnesium rod was chipped on a turning lath. Pieces of the elements were weighed in the ideal atomic ratios of 9:1:4 and 4:1:1, respectively and arc-welded [6] in small niobium ampoules under an argon pressure of 700 mbar. The argon (Westfalen, 99.998%) was purified over titanium sponge (T=870 K), silica gel, and molecular sieves. The sealed ampoules were placed in a water-cooled sample chamber [7] of a high-frequency furnace (Hüttinger Elektronik, type TIG 1.5/300) under flowing argon. The RE4OsMg samples were rapidly heated up to 1500 K for about 5 min. The temperature was reduced to 900 K within 5–15 min and kept at this temperature for 4–5 h followed by quenching. The RE9OsMg4 samples were first annealed at 1500 K for about 5 min, followed by further annealing at 1300 K for 30–60 min and rapid quenching by switching off the high-frequency generator. The temperature was controlled through a Sensor Therm Metis MS09 pyrometer with an accuracy of ±30 K. The ampoules were subsequently sealed in evacuated silica tubes for oxidation protection and heated to 1223 K with a rate of 100 K h−1 in conventional muffle furnaces. The temperature was kept for another 48 h followed by cooling to 823 K with a rate of 3 K h−1. This temperature was kept for further 96 h. Finally, the samples were cooled to room temperature within 3–4 h by switching off the oven. The product samples could mechanically be separated from the ampoules. No reactions with the crucible material were observed. The compact samples show bright metallic lustre; ground powders of RE9OsMg4 are brown-gray. The RE9OsMg4 samples are stable in air while the RE4OsMg samples show sensitivity to moisture after a few days.

2.2 X-ray diffraction

All compounds were characterized by their X-ray powder patterns (Guinier technique, Enraf-Nonius FR552 camera, imaging plate detector, Fuji film BAS-1800) using CuKα1 radiation and α-quartz (a=491.30, c=540.46 pm) as an internal standard. The cubic, respectively hexagonal lattice parameters (Table 1) were obtained from least-squares refinements. Correct indexing was ensured through intensity calculations with the Lazy-Pulverix routine [8].

Refined lattice parameters (Guinier powder data) of the intermetallic compounds RE4OsMg and RE9OsMg4.

| Compound | a (pm) | c (pm) | V (nm3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| La4OsMg | 1436.22(6) | a | 2.9612 |

| Ce4OsMg | 1407.6(2) | a | 2.7889 |

| Ce4Os0.973Mg1.027a | 1406.54(7) | a | 2.7826 |

| Pr4OsMg | 1408.3(1) | a | 2.7931 |

| Nd4OsMg | 1402.4(1) | a | 2.7581 |

| Nd4Os0.978Mg1.022a | 1402.00(7) | a | 2.7558 |

| Sm4OsMg | 1386.59(7) | a | 2.6659 |

| Sm4Os0.920Mg1.080a | 1387.33(5) | a | 2.6702 |

| Gd9OsMg4 | 971.5(5) | 980.4(3) | 0.8013 |

| Gd9OsMg4a | 971.01(5) | 980.43(5) | 0.8006 |

| Tb9OsMg4 | 963.3(4) | 977.6(4) | 0.7856 |

aSingle-crystal data. Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Single-crystal fragments were selected from the carefully crushed RE4OsMg and Gd9OsMg4 samples. The crystals were glued to quartz fibers using beeswax and were studied on a Buerger camera (using white Mo radiation) to check their quality. Intensity data sets of the Ce4OsMg, Nd4OsMg and Gd9OsMg4 crystals were collected on a STOE IPDS-II diffractometer (graphite-monochromatized MoKα radiation; oscillation mode). Numerical absorption corrections were applied to the data. The Sm4OsMg crystal was measured on a STOE StadiVari (Mo micro focus source and a Pilatus detection system) single-crystal diffractometer. The Gaussian-shaped profile of the micro focus X-ray source required scaling along with numerical absorption correction. Details about the data collections and the crystallographic parameters are summarized in Table 2.

Crystallographic data and structure refinement of Ce4Os0.973Mg1.027, Nd4Os0.978Mg1.022, Sm4Os0.920Mg1.080 and Gd9OsMg4.

| Empirical formula | Ce4Os0.973Mg1.027 | Nd4Os0.978Mg1.022 | Sm4Os0.920Mg1.080 | Gd9OsMg4 |

| Space group | F4̅3m | F4̅3m | F4̅3m | P63/mmc |

| Structure type | Gd4RhIn | Gd4RhIn | Gd4RhIn | Ordered Co2Al5 |

| Formula units, Z | 16 | 16 | 16 | 2 |

| Formula weight, g mol−1 | 770.5 | 787.8 | 802.7 | 1702.7 |

| Lattice parameters (single-crystal data) | ||||

| a, pm | 1406.54(7) | 1402.00(7) | 1387.33(5) | 971.01(5) |

| c, pm | 980.43(5) | |||

| Cell volume, nm3 | 2.7826 | 2.7558 | 2.6702 | 0.8006 |

| Calculated density, g cm−3 | 7.36 | 7.60 | 7.99 | 7.06 |

| Crystal size, μm3 | 20×30×90 | 30×40×40 | 20×30×60 | 60×100×150 |

| Transm. ratio (min/max) | 0.248/0.641 | 0.109/0.471 | 0.136/0.320 | 0.039/0.120 |

| Diffractometer type | IPDS-II (STOE) | IPDS-II (STOE) | StadiVari (STOE) | IPDS-II (STOE) |

| Detector distance, mm | 70 | 70 | 40 | 70 |

| Exposure time, min | 30 | 5 | 30 | 4 |

| ω range/step width, deg | 0–180.0/1.0 | 0–180.0/1.0 | 0–180.0/1.0 | 0–180.0/1.0 |

| Integr. param. A/B/EMS | 14.0/−1.0/0.030 | 12.0/−2.0/0.030 | 7.0/−6.0/0.030 | 14.0/−1.0/0.03 |

| Abs. coefficient, mm−1 | 43.3 | 47.5 | 52.0 | 45.5 |

| F(000), e | 5092 | 5225 | 5294 | 1400 |

| θ range, deg | 2–34 | 2–34 | 2–34 | 2–34 |

| hkl range | ±21, ±21, ±21 | ±21, ±20, ±21 | ±21, ±21, ±21 | ±15, ±15, ±15 |

| Total no. reflections | 10 871 | 8954 | 17 510 | 10 578 |

| Independent reflections/Rint | 598/0.0574 | 3002/0.0463 | 575/0.0415 | 622/0.0364 |

| Refl. with I>3 σ(I)/Rσ | 545/0.0120 | 2270/0.0508 | 541/0.0091 | 531/0.0075 |

| Data/parameters | 598/21 | 3002/24 | 575/21 | 622/20 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.51 | 0.90 | 1.28 | 1.66 |

| R1/wR2 for I>3 σ(I) | 0.0214/0.0463 | 0.0243/0.0438 | 0.0163/0.0373 | 0.0210/0.0479 |

| R1/wR2 for all data | 0.0268/0.0478 | 0.0377/0.0463 | 0.0179/0.0378 | 0.0285/0.0494 |

| Extinction coefficient | 120(20) | 81(7) | 390(20) | 300(30) |

| Flack parameter | −0.01(2) | a | −0.02(2) | – |

| Largest diff. peak/hole, e Å−3 | 2.20/−1.56 | 1.87/−1.14 | 0.91/−1.02 | 2.65/−1.74 |

aTwinned crystal [twins of fourlings; five domains observed: 0.461(9):0.436(9):0.023(1):0.042(1):0.038(1)].

2.3 Structure refinements

The Ce4OsMg, Nd4OsMg and Sm4OsMg data sets showed face-centered cubic lattices and no further systematic extinctions. This is compatible with space group F4̅3m and in agreement with our previous work on the RE4OsCd series [4]. The systematic extinctions of the Gd9OsMg4 data set indicated space group P63/mmc, similar to the RE9TMg4 series [5]. The starting atomic parameters were deduced by the charge-flipping algorithm [9] of Superflip [10] and the structure refinements based on F2 were performed with the Jana2006 [11] package (full-matrix least-squares on Fo2) with anisotropic displacement parameters for all atoms. Many of the previous single-crystal studies on the RE4TMg, RE4TCd, RE10TCd3 and RE9TMg4 phases showed small degrees of mixed occupied sites (RE/T, RE/Mg, RE/Cd, T/Mg or T/Cd mixing) [2], [3], [4], [5]. We thus refined all occupancy parameters of the present structures in separate series of least-squares cycles. While all sites of Gd9OsMg4 were fully occupied, we observed small degrees of Os/Mg mixing for the RE4OsMg crystals. These mixed occupancies were refined as least-squares variables in the final cycles, leading to the compositions Ce4Os0.973Mg1.027, Nd4Os0.978Mg1.022 and Sm4Os0.920Mg1.080 for the investigated crystals. The Nd4Os0.978Mg1.022 crystal showed twinning (spinel law), similar to the originally described RE4IrIn series [12]. In the present case this leads to twins of fourlings [13] but only five domains could be found in the refined ratio of 0.461(9):0.436(9):0.023(1):0.042(1):0.038(1). Refinement of the correct absolute structure of the other crystals was ensured through calculation of the Flack parameter [14], [15], [16]. The final difference Fourier synthesis revealed no significant residual peaks. The refined atomic positions, displacement parameters, and interatomic distances (exemplarily for Ce4Os0.973Mg1.027 and Gd9OsMg4) are given in Tables 3–5.

Atomic positions and isotropic displacement parameters (pm2) of Ce4Os0.973Mg1.027, Nd4Os0.978Mg1.022, Sm4Os0.920Mg1.080 (Gd4RhIn type, space group F4̅3m, Z=16) and Gd9OsMg4 (Co2Al5 type, space group P63/mmc, Z=2).

| Atom | Wyckoff site | x | y | z | Ueq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ce4Os0.973(6)Mg1.027(6) | |||||

| Ce1 | 24g | 0.44223(5) | 3/4 | 3/4 | 192(2) |

| Ce2 | 24f | 0.81124(5) | 0 | 0 | 154(1) |

| Ce3 | 16e | 0.65570(3) | x | x | 156(1) |

| 0.973(6) Os/ | 16e | 0.85997(3) | x | x | 251(1) |

| 0.027(6) Mg2 | |||||

| Mg1 | 16e | 0.4217(2) | x | x | 161(5) |

| Nd4Os0.978(3)Mg1.022(3) | |||||

| Nd1 | 24g | 0.55891(3) | 1/4 | 1/4 | 188(1) |

| Nd2 | 24f | 0.18841(3) | 0 | 0 | 144(1) |

| Nd3 | 16e | 0.34417(2) | x | x | 135(1) |

| 0.978(3) Os/ | 16e | 0.13851(2) | x | x | 171(1) |

| 0.022(3) Mg2 | |||||

| Mg1 | 16e | 0.5786(2) | x | x | 177(4) |

| Sm4Os0.920(4)Mg1.080(4) | |||||

| Sm1 | 24g | 0.55994(4) | 3/4 | 3/4 | 277(1) |

| Sm2 | 24f | 0.18795(3) | 0 | 0 | 212(1) |

| Sm3 | 16e | 0.34471(2) | x | x | 217(1) |

| 0.920(4) Os/ | 16e | 0.13942(2) | x | x | 276(1) |

| 0.080(4) Mg2 | |||||

| Mg1 | 16e | 0.5788(2) | x | x | 223(4) |

| Gd9OsMg4 | |||||

| Gd1 | 12k | 0.20915(2) | 2x | 0.05718(3) | 205(1) |

| Gd2 | 6h | 0.53962(3) | 2x | 1/4 | 230(1) |

| Os | 2c | 1/3 | 2/3 | 1/4 | 240(2) |

| Mg1 | 6h | 0.8923(2) | 2x | 1/4 | 228(10) |

| Mg2 | 2a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 262(15) |

Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Anisotropic displacement parameters (pm2) of Ce4Os0.973Mg1.027, Nd4Os0.978Mg1.022, Sm4Os0.920Mg1.080 and Gd9OsMg4.

| Atom | U11 | U22 | U33 | U12 | U13 | U23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ce4Os0.973Mg1.027 | ||||||

| Ce1 | 210(3) | 183(2) | U22 | 0 | 0 | 0(1) |

| Ce2 | 154(3) | 154(2) | U22 | 0 | 0 | −21(2) |

| Ce3 | 156(2) | U11 | U11 | −4(2) | U12 | U12 |

| Os/Mg2 | 251(2) | U11 | U11 | −48(1) | U12 | U12 |

| Mg1 | 161(9) | U11 | U11 | −19(10) | U12 | U12 |

| Nd4Os0.978Mg1.022 | ||||||

| Nd1 | 215(2) | 174(1) | U22 | 0 | 0 | −6(2) |

| Nd2 | 145(2) | 143(1) | U22 | 0 | 0 | −22(2) |

| Nd3 | 135(1) | U11 | U11 | −2(1) | U12 | U12 |

| Os/Mg2 | 171(1) | U11 | U11 | −30(1) | U12 | U12 |

| Mg1 | 177(6) | U11 | U11 | −7(7) | U12 | U12 |

| Sm4Os0.920Mg1.080 | ||||||

| Sm1 | 311(2) | 259(2) | U22 | 0 | 0 | −20(2) |

| Sm2 | 205(2) | 216(1) | U22 | 0 | 0 | −24(2) |

| Sm3 | 217(1) | U11 | U11 | −1(1) | U12 | U12 |

| Os/Mg2 | 276(2) | U11 | U11 | −46(1) | U12 | U12 |

| Mg1 | 223(7) | U11 | U11 | −18(8) | U12 | U12 |

| Gd9OsMg4 | ||||||

| Gd1 | 208(1) | U11 | 206(2) | 108(1) | −6(1) | 6(1) |

| Gd2 | 224(2) | 244(2) | 228(2) | 122(1) | 0 | 0 |

| Os | 267(2) | U11 | 185(3) | 133(1) | 0 | 0 |

| Mg1 | 244(10) | 231(13) | 203(15) | 115(7) | 0 | 0 |

| Mg2 | 223(14) | U11 | 340(30) | 112(7) | 0 | 0 |

Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Interatomic distances (pm) for Ce4Os0.973Mg1.027 and Gd9OsMg4. Standard deviations are equal or smaller than 0.4 pm.

| Ce4Os0.973Mg1.027 | Gd9OsMg4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ce1: | 2 | Mg1 | 342.8 | Gd1: | 1 | Os | 281.7 |

| 2 | Os/Mg2 | 353.9 | 1 | Mg1 | 346.1 | ||

| 2 | Ce3 | 354.0 | 1 | Mg2 | 356.2 | ||

| 4 | Ce2 | 371.0 | 2 | Gd2 | 356.8 | ||

| 4 | Ce1 | 382.4 | 2 | Mg1 | 358.6 | ||

| Ce2: | 2 | Os/Mg2 | 286.8 | 2 | Gd1 | 361.7 | |

| 2 | Mg1 | 362.8 | 2 | Gd2 | 367.9 | ||

| 4 | Ce1 | 371.0 | 2 | Gd1 | 369.2 | ||

| 4 | Ce2 | 375.5 | 1 | Gd1 | 378.1 | ||

| 2 | Ce3 | 379.2 | Gd2: | 2 | Mg1 | 329.5 | |

| Ce3: | 3 | Os/Mg2 | 289.0 | 1 | Os | 346.9 | |

| 3 | Ce1 | 354.0 | 4 | Gd1 | 356.8 | ||

| 3 | Mg1 | 363.4 | 4 | Gd1 | 367.9 | ||

| 3 | Ce3 | 375.2 | 2 | Gd2 | 370.1 | ||

| 3 | Ce2 | 379.2 | Os: | 6 | Gd1 | 281.7 | |

| Os/Mg2: | 3 | Ce2 | 286.8 | 3 | Gd2 | 346.9 | |

| 3 | Ce3 | 289.0 | Mg1: | 2 | Mg2 | 304.8 | |

| 3 | Mg1 | 353.9 | 2 | Mg1 | 313.7 | ||

| Mg1: | 3 | Mg1 | 311.5 | 2 | Gd2 | 329.5 | |

| 3 | Ce1 | 342.8 | 2 | Gd1 | 346.1 | ||

| 3 | Ce2 | 362.8 | 4 | Gd1 | 358.6 | ||

| 3 | Ce3 | 363.4 | Mg2: | 6 | Mg1 | 304.8 | |

| 6 | Gd1 | 356.2 | |||||

All distances of the first coordination spheres are listed.

CCDC 1908721 (Ce4Os0.973Mg1.027), 1908722 (Nd4Os0.978Mg1.022), 1908723 (Sm4Os0.920Mg1.080) and 1908514 (Gd9OsMg4) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

2.4 EDX data

The four single crystals studied on the diffractometers were semiquantitatively analyzed by EDX in variable pressure mode (60 Pa) with a Zeiss EVO® MA10 scanning electron microscope. CeO2, NdF3, SmF3, GdF3, Os, and MgO were used as reference materials. All crystals showed extreme conchoidal surface fracture, leading to scattering of the analytical results (up to ±5 at%). Nevertheless, the experimental values were close to the ideal ones. No impurity elements (especially from the niobium containers) were observed.

2.5 Magnetic characterization

The temperature dependent magnetic susceptibilities of the Gd9OsMg4 and Tb9OsMg4 samples were studied with a Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS) from Quantum Design using the Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM) option. The powdered samples were packed into polypropylene capsules and attached to a brass sample holder. Both samples were investigated with applied magnetic fields of up to 80 kOe (1 kOe=7.96×104 A m−1) in the temperature range of 2.5–300 K.

3 Crystal chemistry

The present phase analytical studies in the RE-Os-Mg systems complete our work on rare earth-rich magnesium intermetallics. The RE4OsMg phases with RE=La–Nd and Sm crystallize with the cubic Gd4RhIn-type structure [12], a ternary ordered version of the Ti2Ni type [17]. The unit cell volume decreases from the lanthanum to the samarium compound, a consequence of the lanthanide contraction. An anomaly is observed for Ce4OsMg. Its cell volume is even slightly smaller than that of Pr4OsMg, indicating intermediate-valent cerium. This is similar to the isotypic series of RE4OsCd phases [4] and their ruthenium-based counterparts RE4RuMg [18], [19] and RE4RuCd [20].

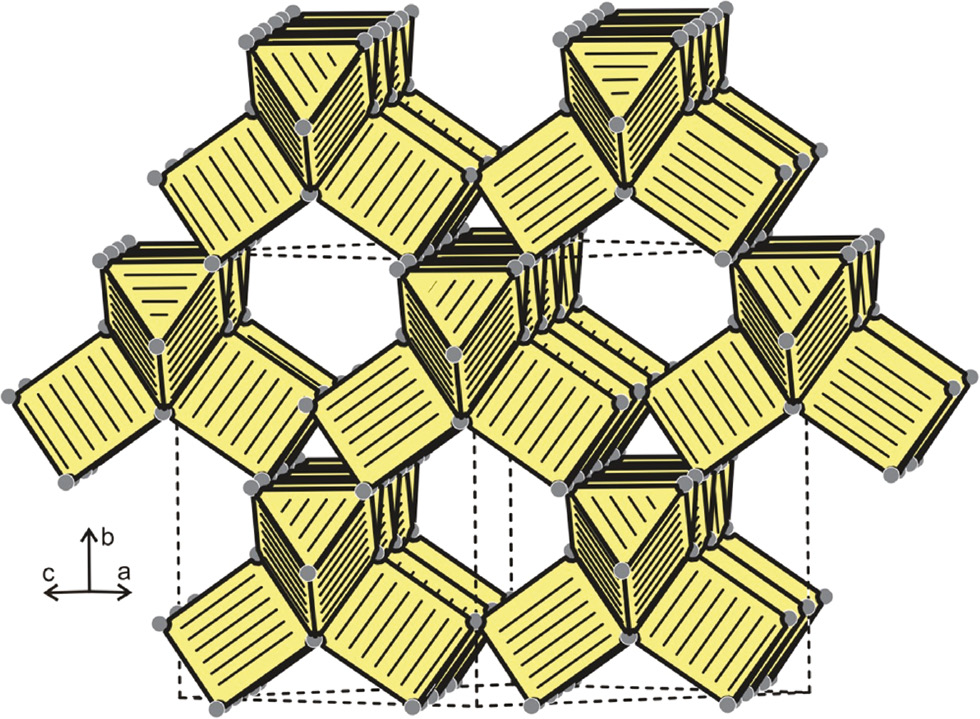

The crystal chemistry of the many RE4TX (X=Mg, Cd, Al, In) phases has been reviewed in detail [2], [3]. Herein we only focus on the peculiarities of the RE4OsMg series, exemplarily for Ce4OsMg. This structure has two striking motifs that can be considered as basic building units. The osmium atoms fill trigonal cerium prisms with Ce–Os distances of 287–289 pm. The small range of distances arises from the fact that the osmium atoms are slightly displaced from the centers of the trigonal prisms. The Ce–Os distances compare well with the sum of the covalent radii [21] of 291 for Ce+Os, indicating substantial covalent Ce–Os bonding. The Ce6Os trigonal prisms are capped by three further cerium atoms at 354 pm on the rectangular faces. Such tricapped trigonal prisms are a frequent coordination motif in intermetallic structures. As is emphasized in two review articles [2], [3], these Ce6Os trigonal prisms are condensed via common edges to a three-dimensional network. Figure 1 shows the substructure of condensed Ce6Os trigonal prisms. Since the Ce4OsMg structure derives from the aristotype Ti2Ni which adopts the diamond space group (vide infra), the tetrahedral symmetry is also preserved in the substructure of condensed prisms.

The substructure of condensed Os@Ce6 trigonal prisms of Ce4OsCd.

The second basic building units are Mg4 tetrahedra (Fig. 2) which fill the cavities formed by the network of condensed prisms. These tetrahedra have ideal symmetry with 312 pm Mg–Mg distances, which are even slightly shorter than in hcp magnesium (6×320 and 6×321 pm) [22]. Such magnesium tetrahedra are a rare structural motif in solid state and molecular materials. Since the Mg4 tetrahedra are embedded within the prismatic network, their nearest neighbors are exclusively cerium atoms. We thus observe a clear structural segregation of the magnesium and osmium atoms, avoiding direct Os–Mg bonding.

![Fig. 2: The magnesium, respectively cadmium substructures of Ce4OsMg, Gd9OsMg4 and Er10RhCd3 [32]. Atom designations and relevant interatomic distances are given in pm.](/document/doi/10.1515/znb-2019-0070/asset/graphic/j_znb-2019-0070_fig_002.jpg)

The magnesium, respectively cadmium substructures of Ce4OsMg, Gd9OsMg4 and Er10RhCd3 [32]. Atom designations and relevant interatomic distances are given in pm.

A general feature observed for the RE4OsMg phases concerns the small degree of Os/Mg on one of the 16e sites. At first sight this seems to contradict a ternary ordered variant; however, this mixing is understandable in view of the aristotype Ti2Ni. During the symmetry reduction (the complete Bärnighausen tree is published in Ref. [17]) from the centrosymmetric space group Fd3̅m to the non-centrosymmetric space group F4̅3m, the 32e Ni site of Ti2Ni splits into two 16e sites which are occupied by osmium and magnesium in the RE4OsMg phases. The Os/Mg mixing can be considered as a kind of residual disorder.

Gd9OsMg4 and Tb9OsMg4 complete the series of RE9OsMg4 phases [5]. We thus observe a switch from the Gd4RhIn to the Y9CoMg4 type between the rare earth elements samarium and gadolinium. This is the general trend for all RE4TX series which exclusively form with the larger rare earth elements [2], [3]. Besides Y9CoMg4, the structure types Pr23Ir7Mg4 [23], La15Rh5Cd2 [24] and Er10FeCd3 [25] are formed for rare earth metal-rich phases with the smaller rare earth atoms.

The RE9TMg4 phases crystallize with an ordered version of the aristotype Co2Al5 [26], [27], [28], first observed for Y9CoMg4 [29]. Besides the RE9CoMg4 (RE=Y, Dy–Tm, Lu) series [29], also the representatives RE9TMg4 (RE=Y, Dy–Tm, Lu; T=Ru, Rh, Os, Ir) are known [5]. The structure type itself has been discussed in detail in the original work. Herein we briefly discuss the structure of Gd9OsMg4 that has been refined from single-crystal X-ray diffractometer data. Similar to the RE4OsMg phases, also in the Gd9OsMg4 structure we observe a strict segregation of osmium and magnesium. The osmium atoms fill trigonal Gd6 prisms with 282 pm Gd–Os distances, compatible with strong covalent Gd–Os bonding. These Os@Gd6 trigonal prisms (TP) are condensed with empty Gd6 octahedra (O) in the sequence –T–O–O– forming rows that extend in z direction. These rows alternate with rows of corner- and face-sharing Mg4 tetrahedra (Fig. 2). Consequently, the whole structure can be described as a simple rod-packing of these two building units. This is discussed and illustrated in detail in ref. [29]. The row of corner- and face-sharing Mg4 tetrahedra reminds of the structure of the hexagonal Laves phases REMg2 [30]. The Mg–Mg distances within these rows range from 305 to 314 pm, similar to the data for the isolated tetrahedra in the RE4OsMg phases.

While the RE4TMg and RE4TCd phases are isotypic, there is a striking difference for the RE9TMg4 ones. With magnesium we observe formation of the rows of tetrahedra, while in the related cadmium-based phases the corner-sharing position in the rows is occupied by a rare earth element (Fig. 2), leading to the general composition RE10TCd3, characterized for T=Fe, Co, Ni, Ru, Rh, Pd, Ir, Pt [4], [25], [31], [32]. Recently also some aluminides RE10TAl3 (RE=Y, Ho, Er, Tm, Lu; T=Fe, Co, Ni, Ru, Rh, Pd, Os, Ir, Pt) [33], [34] were reported.

Thus we observe two different coloring variants of the Co2Al5 type, the RE9TMg4 compositions on the one and the RE10TCd3 respectively RE10TAl3 ones on the other hand. In view of the different bonding patterns within the rows of corner- and face-sharing tetrahedra, the RE10TCd3/RE10TAl3 and RE9TMg4 phases are rather isopointal [35], [36] than isotypic.

4 Magnetic behavior

The temperature dependence of the inverse magnetic susceptibilities of the Gd9OsMg4 and Tb9OsMg4 samples was only linear in the high-temperature regimes (T≥250 K). An evaluation of these parts according to the Curie-Weiss law led to experimental magnetic moments of 8.2(1) μB per Gd atom and 9.3(1) μB per Tb atom which approximately match with the free ion values of 7.94 μB for Gd3+ and 9.72 μB for Tb3+ [37]. The low-temperature regime was substantially influenced by small amounts (not detectable in the X-ray powder patterns) of GdMg and TbMg where the atoms are ordered ferromagnetically at TC=120, respectively 81 K [38]. These ferromagnetic impurity phases overlap the paramagnetic regime and we observe several weak anomalies. It is well known that these CsCl-type phases form as by-products for most of these rare earth-rich phases of magnesium as well as cadmium. Furthermore, they show the formation of solid solutions REMg1−xTx and RECd1−xTx with the respective transition metal [1]. Consequently, a distribution of domains with slightly different (now ternary) compositions is observed and thus a distribution of ferromagnetically ordering domains with different Curie temperatures. This is exactly the problem for the Gd9OsMg4 and Tb9OsMg4 samples studied herein and a deeper interpretation of the magnetically ordered regime is not appropriate. The dependence of the Curie temperature on the composition of such CsCl-type phases was exemplarily studied for the solid solution GdRuxCd1−x which extends up to x≈0.25 and shows a continuous decrease of TC from 258 K for GdCd to 61.5 K for GdRu0.20Cd0.80 [39], [40].

Acknowledgements

We thank Dipl.-Ing. Jutta Kösters for the collection of the single-crystal diffractometer data.

References

[1] P. Villars, K. Cenzual, Pearson’s Crystal Data: Crystal Structure Database for Inorganic Compounds (release 2018/19), ASM International®, Materials Park, Ohio (USA) 2018.Search in Google Scholar

[2] U. Ch. Rodewald, B. Chevalier, R. Pöttgen, J. Solid State Chem.2007, 180, 1720.10.1016/j.jssc.2007.03.007Search in Google Scholar

[3] F. Tappe, R. Pöttgen, Rev. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 31, 5.10.1515/revic.2011.007Search in Google Scholar

[4] T. Block, R. Pöttgen, Monatsh. Chem.2019, 150. DOI: 10.1007/s00706-019-02400-y.10.1007/s00706-019-02400-ySearch in Google Scholar

[5] S. Stein, S. F. Matar, L. Heletta, R. Pöttgen, Solid State Sci.2018, 82, 70.10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2018.03.020Search in Google Scholar

[6] R. Pöttgen, Th. Gulden, A. Simon, GIT Labor-Fachzeitschrift1999, 43, 133.Search in Google Scholar

[7] R. Pöttgen, A. Lang, R.-D. Hoffmann, B. Künnen, G. Kotzyba, R. Müllmann, B. D. Mosel, C. Rosenhahn, Z. Kristallogr.1999, 214, 143.10.1524/zkri.1999.214.3.143Search in Google Scholar

[8] K. Yvon, W. Jeitschko, E. Parthé, J. Appl. Crystallogr.1977, 10, 73.10.1107/S0021889877012898Search in Google Scholar

[9] L. Palatinus, Acta Crystallogr.2013, B69, 1.10.1107/S0108767313099868Search in Google Scholar

[10] L. Palatinus, G. Chapuis, J. Appl. Crystallogr.2007, 40, 78610.1107/S0021889807029238Search in Google Scholar

[11] V. Petříček, M. Dušek, L. Palatinus, Z. Kristallogr.2014, 229, 345.10.1515/zkri-2014-1737Search in Google Scholar

[12] R. Zaremba, U. Ch. Rodewald, R.-D. Hoffmann, R. Pöttgen, Monatsh. Chem.2008, 139, 481.10.1007/s00706-007-0796-xSearch in Google Scholar

[13] Th. Hahn, H. Klapper, Twinning of crystals, (Ed.: A. Authier), International Tables for Crystallography, IUCr, 1st edition, Kluwer Academic Publishing, Dordrecht 2003.Search in Google Scholar

[14] H. D. Flack, G. Bernadinelli, Acta Crystallogr.1999, A55, 908.10.1107/S0108767399004262Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] H. D. Flack, G. Bernadinelli, J. Appl. Crystallogr.2000, 33, 1143.10.1107/S0021889800007184Search in Google Scholar

[16] S. Parsons, H. D. Flack, T. Wagner, Acta Crystallogr.2013, B69, 249.10.1107/S2052519213010014Search in Google Scholar

[17] P. Solokha, S. De Negri, V. Pavlyuk, A. Saccone, Chem. Met. Alloys2009, 2, 39.10.30970/cma2.0088Search in Google Scholar

[18] S. Tuncel, B. Chevalier, S. F. Matar, R. Pöttgen, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem.2007, 633, 2019.10.1002/zaac.200700252Search in Google Scholar

[19] S. F. Matar, B. Chevalier, R. Pöttgen, Intermetallics2012, 21, 88.10.1016/j.intermet.2012.06.005Search in Google Scholar

[20] F. M. Schappacher, R. Pöttgen, Monatsh. Chem.2008, 139, 1137.10.1007/s00706-008-0908-2Search in Google Scholar

[21] J. Emsley, The Elements, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1999.Search in Google Scholar

[22] J. Donohue, The Structures of the Elements, Wiley, New York 1974.Search in Google Scholar

[23] U. Ch. Rodewald, S. Tuncel, B. Chevalier, R. Pöttgen, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem.2008, 634, 1011.10.1002/zaac.200700552Search in Google Scholar

[24] F. Tappe, U. Ch. Rodewald, R.-D. Hoffmann, R. Pöttgen, Z. Naturforsch.2011, 66b, 559.10.1515/znb-2011-0602Search in Google Scholar

[25] M. Johnscher, T. Block, R. Pöttgen, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem.2015, 641, 369.10.1002/zaac.201400475Search in Google Scholar

[26] A. J. Bradley, C. S. Cheng, Z. Kristallogr.1938, 99, 480.10.1524/zkri.1938.99.1.480Search in Google Scholar

[27] J. B. Newkirk, P. J. Black, A. Damjanovic, Acta Crystallogr.1961, 14, 532.10.1107/S0365110X61001637Search in Google Scholar

[28] A. Ormeci, Yu. Grin, Isr. J. Chem.2011, 51, 1349.10.1002/ijch.201100147Search in Google Scholar

[29] S. Stein, R. Pöttgen, Z. Kristallogr.2018, 233, 607.10.1515/zkri-2017-2124Search in Google Scholar

[30] P. I. Krypyakevych, V. I. Evdokimenko, Dopov. Akad. Nauk Ukr. RSR1962, 1610.Search in Google Scholar

[31] O. Niehaus, M. Johnscher, T. Block, B. Gerke, R. Pöttgen, Z. Naturforsch.2016, 71b, 57.10.1515/znb-2015-0145Search in Google Scholar

[32] T. Block, S. Klenner, L. Heletta, R. Pöttgen, Z. Naturforsch.2018, 73b, 35.10.1515/znb-2017-0181Search in Google Scholar

[33] N. Nasri, M. Pasturel, V. Dorcet, B. Belgacem, R. Ben Hassen, O. Tougait, J. Alloys Compd.2015, 650, 528.10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.07.277Search in Google Scholar

[34] C. Benndorf, H. Eckert, O. Janka, Dalton Trans.2017, 46, 1083.10.1039/C6DT04314CSearch in Google Scholar

[35] E. Parthé, L. M. Gelato, Acta Crystallogr.1984, A40, 169.10.1107/S0108767384000416Search in Google Scholar

[36] L. M. Gelato, E. Parthé, J. Appl. Crystallogr.1987, 20, 139.10.1107/S0021889887086965Search in Google Scholar

[37] H. Lueken, Magnetochemie, Teubner Studienbücher Chemie, Leipzig, 1999.10.1007/978-3-322-80118-0Search in Google Scholar

[38] K. H. J. Buschow, Rep. Prog. Phys.1979, 42, 1373.10.1088/0034-4885/42/8/003Search in Google Scholar

[39] F. Tappe, F. M. Schappacher, W. Hermes, M. Eul, R. Pöttgen, Z. Naturforsch.2009, 64b, 356.10.1515/znb-2009-0320Search in Google Scholar

[40] L. Li, O. Niehaus, M. Johnscher, R. Pöttgen, Intermetallics2015, 60, 9.10.1016/j.intermet.2015.01.005Search in Google Scholar

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Review

- The bio-relevant metals of the periodic table of the elements

- Research Articles

- Synthesis and investigation of 3,5-bis-linear and macrocyclic tripeptidopyridine candidates by using l-valine, N,N′-(3,5-pyridinediyldicarbonyl)bis-dimethyl ester as synthon

- Supramolecular assembly of two copper(II) coordination compounds of topiroxostat with dialkylformamide ligands

- Ferromagnetic interactions in a dicyanamide-bridged multinuclear metal-organic framework [Pr3NH]+ [Mn(dca)3]−·H2O

- Synthesis, structure, and properties of nickel(II) and copper(II) coordination polymers with the 5-ethyl-pyridine-2,3-dicarboxylate ligand

- Die monoklinen Seltenerdmetall(III)-Chlorid-Oxidoarsenate(III) mit der Zusammensetzung SE5Cl3[AsO3]4 (SE=La–Nd, Sm)

- Facile synthesis of model 2,4-diaryl-1,3,4-thiadiazino[5,6-h]fluoroquinolones

- The rare earth metal hydride tellurides REHTe (RE=Y, La–Nd, Gd–Er)

- Osmium and magnesium: structural segregation in the rare earth-rich intermetallics RE4OsMg (RE=La–Nd, Sm) and RE9TMg4 (RE=Gd, Tb)

- Note

- A heterometallic Cd/Ag/Se complex incorporating 3-ferrocenyl-5-(2-pyridyl)pyrazolato (fcpp) ligands: synthesis and structure of [Cd2{Ag(SePh)}2(μ3-OH2)2(μ2,η3-fcpp)4]·2C3H6O

- Book Review

- Essential Metals in Medicine. Volume 19 of the Metal Ions in Life Sciences series

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this Issue

- Review

- The bio-relevant metals of the periodic table of the elements

- Research Articles

- Synthesis and investigation of 3,5-bis-linear and macrocyclic tripeptidopyridine candidates by using l-valine, N,N′-(3,5-pyridinediyldicarbonyl)bis-dimethyl ester as synthon

- Supramolecular assembly of two copper(II) coordination compounds of topiroxostat with dialkylformamide ligands

- Ferromagnetic interactions in a dicyanamide-bridged multinuclear metal-organic framework [Pr3NH]+ [Mn(dca)3]−·H2O

- Synthesis, structure, and properties of nickel(II) and copper(II) coordination polymers with the 5-ethyl-pyridine-2,3-dicarboxylate ligand

- Die monoklinen Seltenerdmetall(III)-Chlorid-Oxidoarsenate(III) mit der Zusammensetzung SE5Cl3[AsO3]4 (SE=La–Nd, Sm)

- Facile synthesis of model 2,4-diaryl-1,3,4-thiadiazino[5,6-h]fluoroquinolones

- The rare earth metal hydride tellurides REHTe (RE=Y, La–Nd, Gd–Er)

- Osmium and magnesium: structural segregation in the rare earth-rich intermetallics RE4OsMg (RE=La–Nd, Sm) and RE9TMg4 (RE=Gd, Tb)

- Note

- A heterometallic Cd/Ag/Se complex incorporating 3-ferrocenyl-5-(2-pyridyl)pyrazolato (fcpp) ligands: synthesis and structure of [Cd2{Ag(SePh)}2(μ3-OH2)2(μ2,η3-fcpp)4]·2C3H6O

- Book Review

- Essential Metals in Medicine. Volume 19 of the Metal Ions in Life Sciences series