Abstract

Crystallographically well-documented examples of “Racemic Mimic” pairs remain scarce. We describe two new species belonging to this rare class of pseudo-symmetric crystals, which we term “Racemic Mimics.” The Mn(III) and Co(III) compounds – azido-methanol-((R,R)-N,N′-bis(salicylidene)-1,2-diaminocyclohexane)manganese(III) and (1-cyanoethyl)-pyridine-bis(dimethylglyoximato)cobalt(III) – have been studied in two distinct crystalline forms: (1) a centrosymmetric form [P21/n, Z′ = 1.0] and (2) a Sohncke form [P21, Z′ = 2.0]. In each case, the structures are related by their nearly identical cell constants, with the latter form exhibiting a doubled Z′ due to the loss of the n-glide plane. Our findings expand the scope of racemic mimicry beyond previously recognized purely organic systems, demonstrating that this phenomenon is more widespread than previously appreciated. Additionally, we highlight the overlooked chirality of the tri-bonded oxygen in the Mn(III) compound, a feature typically disregarded in the Cambridge Structural Database. This work adds another chapter to the intriguing study of racemic mimicry in crystallography.

1 Introduction

In this study, we deal with the behavior of a pair of metal compounds of Mn(III) and Co(III) which illustrate the fact that Racemic Mimic compounds exist in a compositionally broad range of molecules – not limited by such common classifications as “amino acids”, “organometallics”, etc. The Mn(III) and Co(III) examples described here are:

Co: (1-Cyanoethyl)-pyridine-bis(dimethylglyoximato)cobalt(III) crystallizing as a racemate (BAGMUR10) (III) and in a Sohncke space group (BAGMOL10) (IV), both appearing in.3a In a follow-up study, the H atoms bonded to the chiral C atoms (stereogenic center) of the 1-cyanoethyl groups in two cobalt complexes, [(R)-1-cyanoethyl] bis(dimethylglyoximato) (pyridine)cobalt(III) were replaced with deuterium atoms and neutron diffraction was used (RALBUB).3a

2 Part (a) – the manganese pair

Recently, we 4 published a study of the structure of the Grubbs Catalyst-(1-(2,6-diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-trimethyl-3-phenyl-pyrrolidin-2-ylidene)-({5-nitro-2-[(propan-2-yl)oxy]phenyl}methylidene)-dichlorido-ruthenium(II) that constitutes Part I of our ongoing studies on the structural characteristics of compounds belonging in the class of “Racemic Mimics”. That publication gives a thorough recount of the history of the discovery, crystallization label assignment and structural knowledge available on the subject until the end of 2024. For the interested reader, we recommend a careful examination of that source. Herein, we discuss the properties of Mn(III) and Co(III) specimens that also belong in that class.

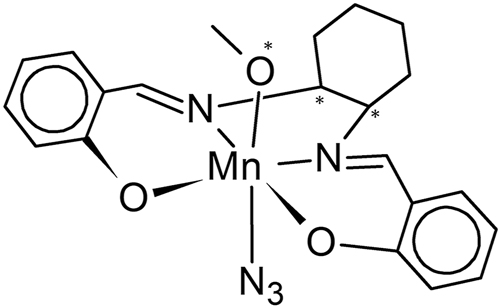

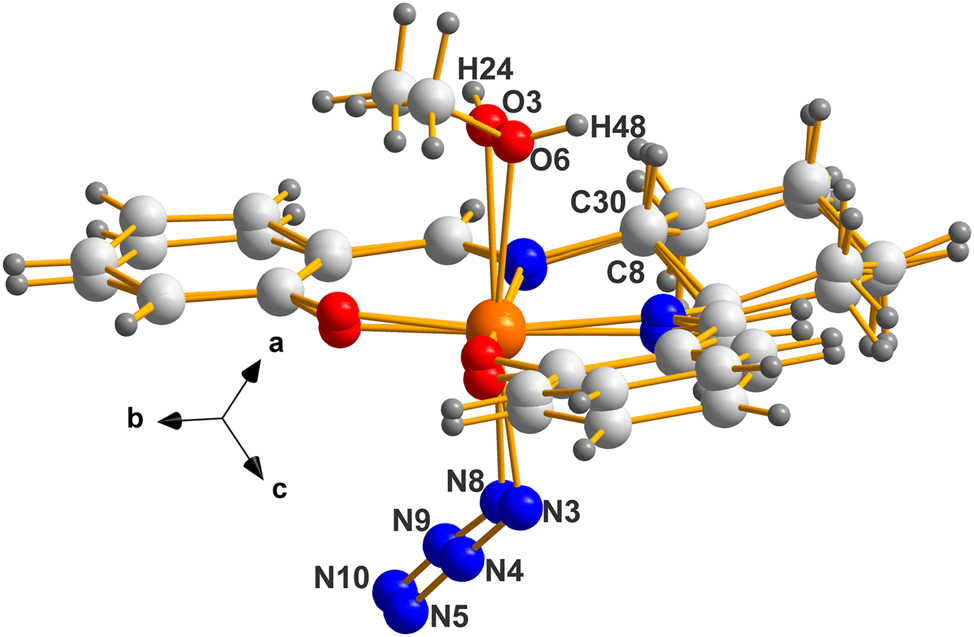

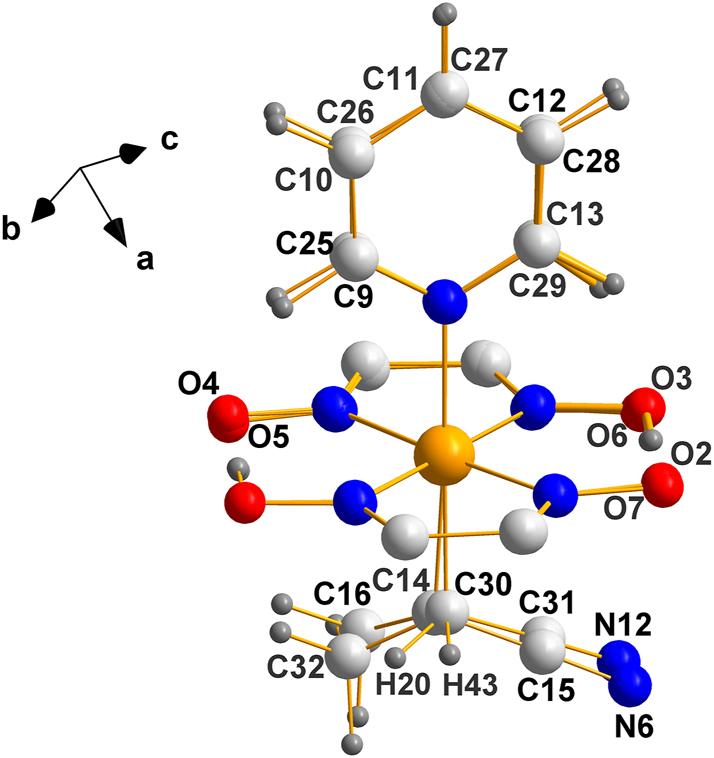

The structure of molecule (I) is depicted in Scheme 1 and Figure 1 using the coordinates of the species present in the asymmetric unit of the racemic form, labeled in the CCDC 5 as AXUZAV (I). 1 Hereafter overlay figures and data were obtained with MERCURY 6 and final text figures with DIAMOND. 7

Structural diagram of azido-methanol-((R,R)-N,N′-bis(salicylidene)-1,2-diaminocyclohexane)manganese(III) (I) with * indicating the chiral centers.

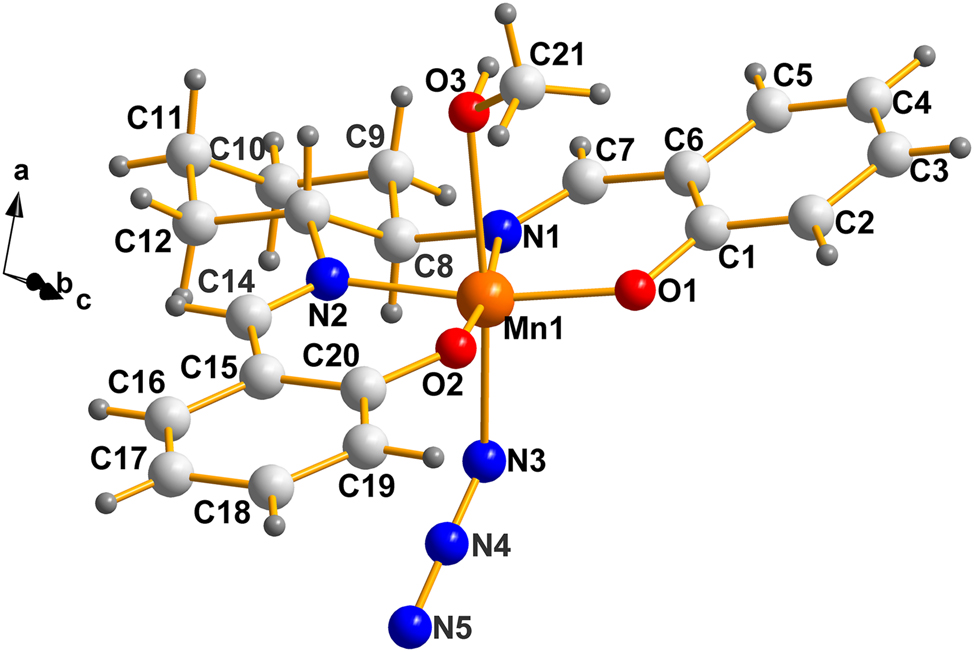

A labeled view of the molecule as it appears in the racemic version (I). Atoms C8, C13 and O3 are chiral centers. For more details, see Figure 2.

3 The question of chirality centers present in molecules of interest

Before we discuss chirality details for the current cases, we must clarify the issue of the chirality at O3 (see Figure 1) which is not dealt with properly in the CCDC 5 because of ignoring the stereogenic contribution of non-bonded pairs in tri-bonded oxygen, as in the current case (n.b. the chirality of stereogenic, asymmetric, tri-bonded N and S, and others, are also ignored; but, the CCDC have indicated they are in the process of doing so). The identification of chiral oxygen atoms in metal complexes, involving a lone pair of electrons on oxygen, has been discussed previously by Bernal et al. 8 in the case of Hexol Cluster Cations [Tris(cis-tetraaminedihydroxo)Co]+6. They identify “six OH oxygens (that) are chiral centers once the presence of the unused non-bonding pair is identified.”

More recently, Alkorta et al., 9 have discussed how the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog (CIP) rules can be extended to supramolecular structures involving lone pairs of electrons.

In the case of the Mn(III) compound, AXUZAV (I), discussed in this work, it is important to note that the atoms around O3 (namely H24, and the methyl group C21), are not flexible in the crystalline state. Their orientation is fixed due to the hydrogen bond between H24 at (x, y, z) and N5 of the neighbouring molecule at (x − 1, y, z). This is shown in Figure 2(a). The atom, O3, is tetrahedral and its non-bonded pair points up and to the left (in the direction of the adjacent H atom). The chirality ranking sequence is: Mn>C21>H>non-bonded Pair; thus, O3 is (R) in Figure 2(b). For a more detailed illustration, depicting the racemic pair of molecules, see Figure 2(b), next.

Molecules of AXUZAV (I) (a) the intermolecular hydrogen bond between H24 and N5 fixes the orientation of the lone pair of electrons on O3. (b) C8 and C13 are the chiral atoms of a racemic pair of (I). In the left image, the non-bonded pair points into the plane of the paper; thus, it is S. The one on the right points out of the paper; thus, it is R.

If necessary, experimental techniques such as solid-state circular dichroism (such as described by Jain et al. 10 ) could be used in future work to study the chirality of crystalline the Mn(III) compound.

Note the inversion center between images of the racemic pair in (I), made obvious by the atomic labels. As a result, the chirality sequence (C8, C13, O3) for the left image is SSS while that at right is RRR. These results are to be compared with those for the two independent moieties present in the asymmetric unit of GISXAK (II), dealt with below.

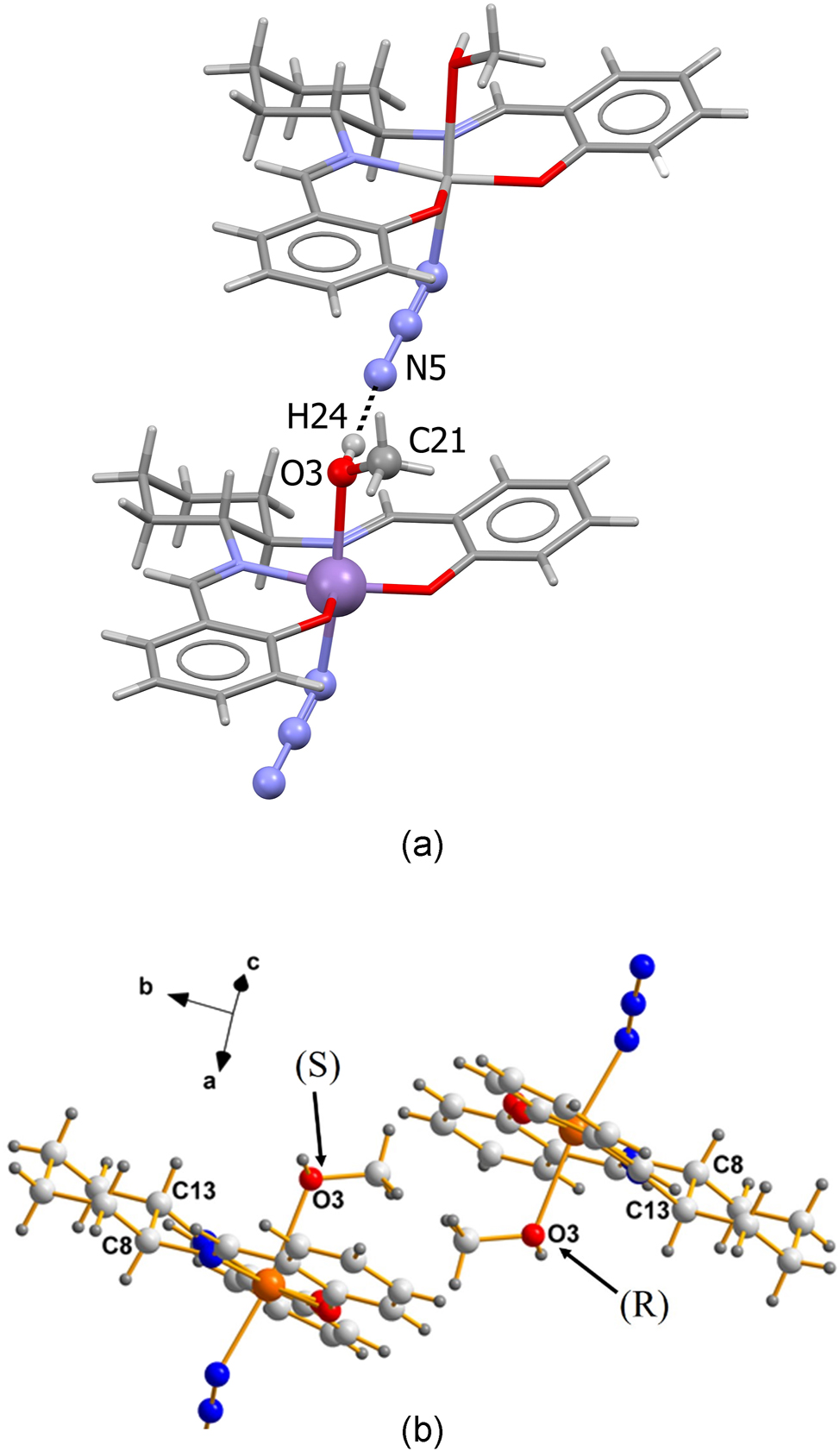

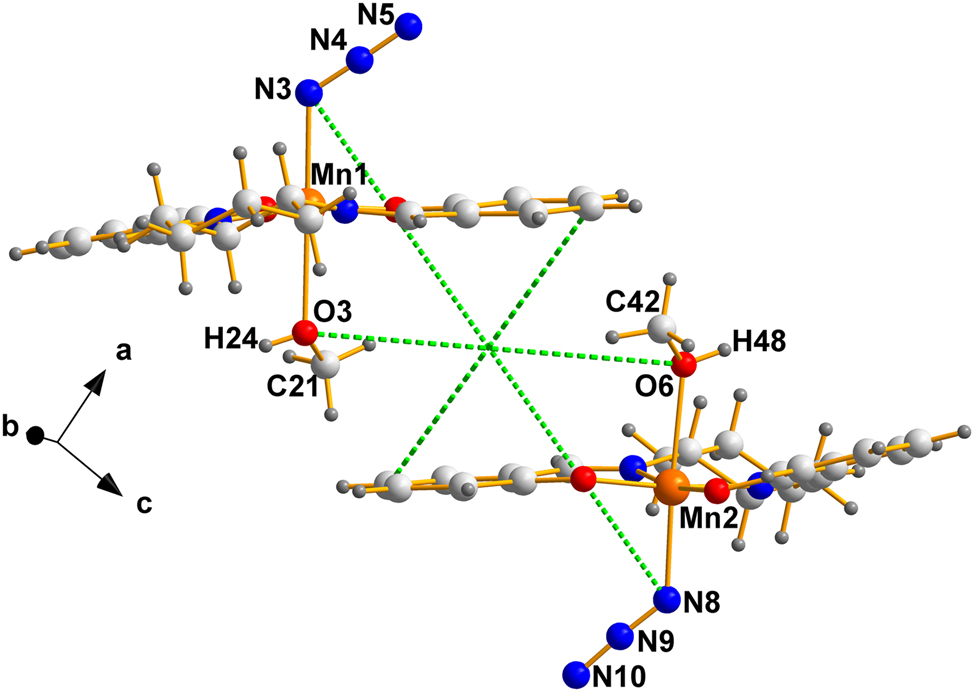

The crystallization characteristics of the cells in (I) and (II) are typical of those belonging in the Racemic Mimic class, for which the packing is nearly identical; in fact, sometimes remarkably so, as is obvious by examining the pair of molecules present in (II), depicted in Figure 3.

The two crystallographically independent molecules in the Sohncke version (II). The intersection of the green dotted lines is the pseudo-inversion center, located in this case at an arbitrary point, since in P1 the origin is completely arbitrary and must be set.

Labels clearly identify the chiral oxygens, the chiral carbons resulting from solution and refinement of the specific crystal (II) selected by Bhargavi et al. 2 Some useful details of the pair are summarized in Table 1.

The unit cell information for the structures GISXAK (II) and AXUZAV (I) discussed in this paper. The Flack parameter was obtained from the deposited data.

| REFCODE | GISXAK2a (II) | GISXAK012b (II) | AXUZAV 1 (I) |

| Formula | C21H24MnN5O3 | C21H24MnN5O3 | C21H24MnN5O3 |

| Crystal system | Triclinic | Triclinic | Triclinic |

| Space group | P1 | P1 |

P

|

| a/Å | 8.3373(6) | 8.3907(18) | 8.5153(3) |

| b/Å | 9.9021(7) | 9.9664(18) | 9.8854(3) |

| c/Å | 12.1434(8) | 12.342(2) | 12.0241(5) |

| α/° | 96.7650(10) | 96.375(3) | 96.674(3) |

| β/° | 95.8970(10) | 97.023(3) | 96.564(3) |

| γ/° | 95.8960(10) | 96.001(2) | 97.083(3) |

| Volume/Å3 | 983.6(3) | 1,010.7(3) | 989.1(2) |

| Z | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Z′ | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Flack parameter | 0.012(18) | 0.04(2) | – |

| T/K | 100 | 295 | 120 |

| Density | 1.517 | 1.477 | 1.509 |

| Crystal color | Brown | Brown | Dark brown |

As is evident from the numerical information above, the fundamental constants of specimens (I) and (II) are remarkably close. Given that degree of resemblance in numerical constants, how close are the stereochemical features of the molecules present in the GISXAK (II) pair? Figure 4 answers that question.

The overlay of molecule 2 on molecule 1 in the enantiomorphic version (II), using only the routine Flexible in MERCURY. 6 Note the difference in chirality of oxygens O3 and O6 is evident here (H24 points into and H48 out of the paper) while C8 and C30 are closely overlaid.

4 Part (b) – the cobalt pair

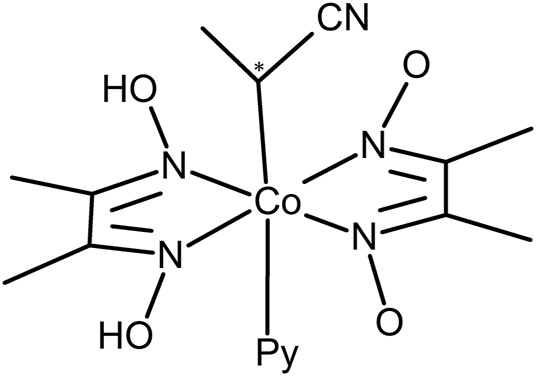

A structural diagram for (1-cyanoethyl)-pyridine-bis(dimethylglyoximato)cobalt(III) is given in Scheme 2 and the crystallographic details for BAGMOL10, RALBUB and BAGMUR10 are given in Table 2.

Structural diagram of (1-cyanoethyl)-pyridine-bis(dimethylglyoximato)cobalt(III) with * indicating the chiral center.

The unit cell information for the structures BAGMOL10 and RALBUB and BAGMUR10 discussed in this paper.

| REFCODE | BAGMOL103a [III] | RALBUB3b [III] | BAGMUR103a [IV] |

| Formula | C16H23CoN6O4 | C16H22DCoN6O4 | C16H23CoN6O4 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | P21 | P21 | P21/n |

| a/Å | 16.021(3) | 16.0665(15) | 15.824(3) |

| b/Å | 12.620(1) | 12.5929(11) | 12.704(1) |

| c/Å | 9.627(1) | 9.6440(11) | 9.559(1) |

| β/° | 94.27(2) | 94.626(9) | 92.78(2) |

| Volume/Å3 | 1941.0(5) | 1944.9(3) | 1919.4(5) |

| Z | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Z′ | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Flack parameter | Not reported | −0.01(3) | – |

| T/K | 295 | 295 | 295 |

| Density | 1.445 | 1.446 | 1.461 |

| Color | Red | Red | Orange |

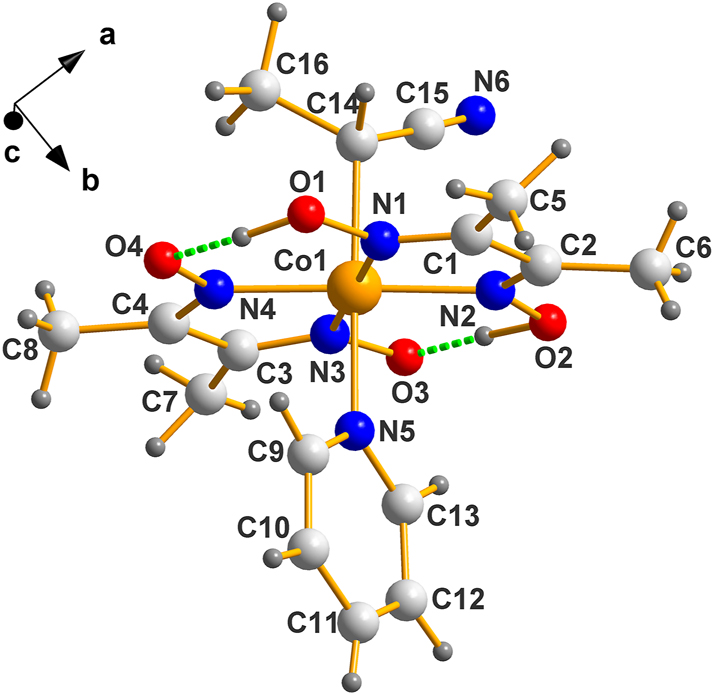

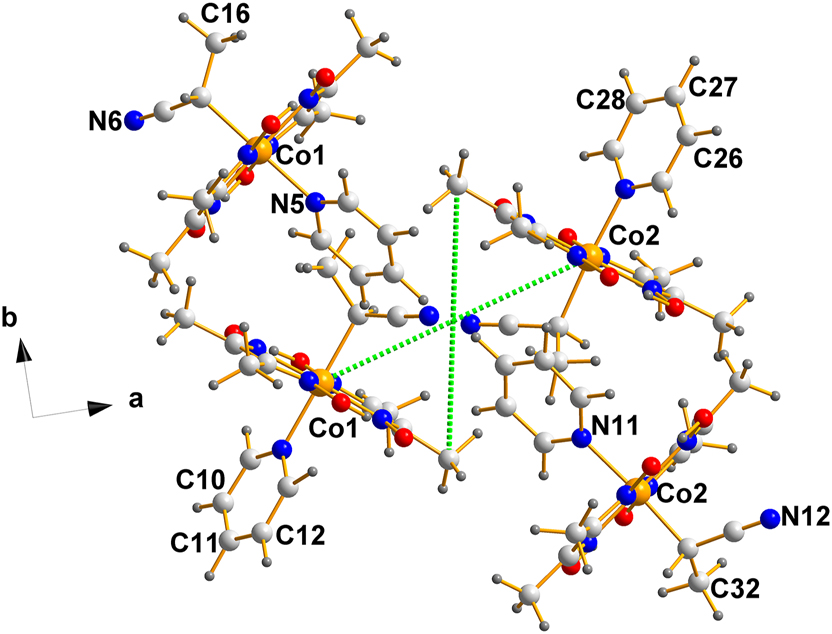

A representation of the molecules in this example appears next, Figure 5, where the asymmetric unit of the racemic BAGMUR10 is shown.

Molecular structure of the enantiomorphic version (IV), C14 is R as evident from the ranking Co>C15>C16. Exactly where the hydrogens between O1–O4 and O2–O3 belong is speculative, to say the least; they are depicted where reported.

One of the two molecules in the asymmetric unit of BAGMOL10 is depicted in Figure 6, next.

Molecular structure of one molecule of (III). Using the same ranking system as above, C14 is S. Obviously, the one belonging to Co2 is also S as demanded by the two components of the Sohncke member of a Racemic Mimic.

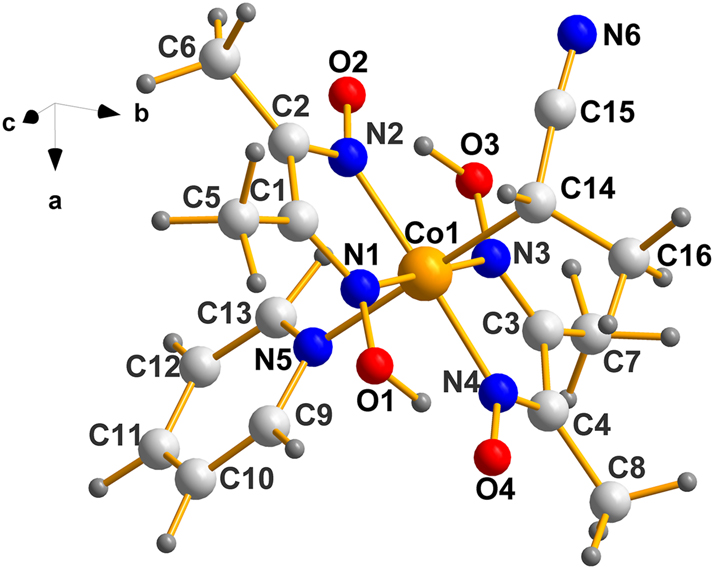

A useful comparison of how closely the Co1–Co2 molecules resemble each other stereochemically is shown in Figure 7 where molecule 2 was superimposed on molecule 1.

An overlay of the two independent molecules in the asymmetric unit of the enantiomorphic structure, (III). The agreement is remarkable given that the crystals contain two independent molecules in the asymmetric unit, which are quite flexible.

The fact that the planar [Co(dimethylglyoxime)] fragment superimposes almost exactly is no surprise since such fragments are extremely rigid; what is remarkable is the degree to which the axial ligands overlap because they are connected to the Co atom by single bonds; specially, since in solution those fragments must be freely rotating and as they crystallize, packing forces can readily move them around.

In generating Figure 7, the output of MERCURY in which the two images were overlayed “as is” was selected; therefore, it is obvious that (a) the chiral center(s) on both molecules are the same (b) torsional adjustments were not needed to obtain the recorded fit, which is notable given the size and bonding of the constituent fragments.

Finally, we come to the question of the packing of the molecules in the unit cell, which is depicted in Figure 8.

A projection down the c-axis of the unit cell of the non-centrosymmetric structure, (III). Note that they form columns with no apparent bonding connections among them or between them. The possibility of π–π stacking was explored with negative results.

As is evident from the intersection of the green dotted lines, located at the center of mass of the fragment displayed (0.2500, 0.5006, 0.5000), there is a pseudo-inversion center separating the Co1 and Co2 molecules, a feature that is characteristic of Racemic Mimics.

5 Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that the nature of the molecules crystallizing as Racemic Mimics is quite extensive and not limited to purely organic moieties, as may have appeared by the earliest examples in which the phenomenon was observed (see ref. 4]).

Importantly, and unexpectedly, the recognition and labeling of chiral centers of three-fold asymmetrically bonded atoms bearing a non-bonded pair (e.g., N, O, S, etc.) was, heretofore, ignored in the CCDC. 5 They are aware of that omission and plan to remedy it.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: DCL and IB conceptualized the project and wrote the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

-

Research funding: Funding from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, is gratefully acknowledged.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Khalaji, A.; Hadadzade, H.; Fejfarova, K.; Dusek, M. Synthesis, Characterization, and X-Ray Crystal Structure of the Manganese (III) Complex Mn (Sal2hn)(CH3OH)(N3)[Sal2hn = N,N′-Bis (Salicylidene)-1,2-Hexanediamine]. Russ. J. Coord. Chem. 2010, 36, 618–621. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1070328410080117.Search in Google Scholar

2(a). Bhargavi, G.; Rajasekharan, M. V.; Costes, J. Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Magnetic Properties of [Mn ((1R,2R)‐Salcy) N3/NCS] Complexes: Solvent Dependent Crystallization of Monomers, Chains and Dimers. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2 (26), 7975–7982. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.201701259.(b) Zhang, D.; Zhang, H.; Chen, K. Three Chiral Schiff-Base-Manganese (III)-Based Complexes: Synthesis, Structures and Magnetic Properties. J. Chem. Res. 2015, 39 (6), 346–350. https://doi.org/10.3184/174751915X14328908144330.Search in Google Scholar

3(a). Ohashi, Y.; Yanagi, K.; Kurihara, T.; Sasada, Y.; Ohgo, Y. Crystalline-State Reaction of Cobaloxime Complexes by X-Ray Exposure. 2. An Order-to-Order Racemization in the Crystal of [(S)-1-Cyanoethyl](Pyridine) Bis (Dimethylglyoximato) Cobalt (III). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104 (23), 6353–6359. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00387a033.(b) Ohhara, T.; Uekusa, H.; Ohashi, Y.; Tanaka, I.; Kumazawa, S.; Niimura, N. Direct Observation of Deuterium Migration in Crystalline-State Reaction by Single-Crystal Neutron Diffraction. III. Photoracemization of 1-Cyanoethyl Cobaloxime Complexes. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B 2001, B57 (4), 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108768101006838.Search in Google Scholar

4. Levendis, D. C.; Bernal, I. The Grubbs Catalyst–Dichlorido (1-(2,6-Diethylphenyl)-3,5,5-Trimethyl-3-Phenylpyrrolidin-2-Ylidene)-({5-Nitro-2-[(Propan-2-Yl) Oxy] Phenyl} Methylidene) Ruthenium (II)–Some Observations on the Crystallography and Stereochemistry of a Racemic Mimic Pair. Z. Kristallogr. 2025, 240, 173–179. https://doi.org/10.1515/zkri-2025-0001.Search in Google Scholar

5. Groom, C. R.; Bruno, I. J.; Lightfoot, M. P.; Ward, S. C. The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. B 2016, 72, 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1107/S2052520616003954.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Macrae, C. F.; Bruno, I. J.; Chisholm, J. A.; Edgington, P. R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Rodriguez-Monge, L.; Taylor, R.; Streek, J. V. D.; Wood, P. A. Mercury CSD 2.0 – New Features for the Visualization and Investigation of Crystal Structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889807067908.Search in Google Scholar

7. Brandenburg, K.; Putz, H. Diamond-Crystal and Molecular Structure Visualization (Version 4.6. 0); Crystal Impact GbR-Bonn: Germany, 2019.Search in Google Scholar

8. Bernal, I.; Gonzalez, M. T.; Cetrullo, J.; Cai, J. Why are Hexol Cluster Cations [Tris(Cis-Tetraaminedihydroxo)Co]+6 So Easily Resolved into Their Antipodes? Part 2. Preparation, Crystal Structural Studies and the Nine Sources of Chirality of Hexol Clusters. Struct. Chem. 2001, 12 (1), 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009266219630.10.1023/A:1009266219630Search in Google Scholar

9. Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J.; Cintas, P. Adding Only One Priority Rule Allows Extending CIP Rules to Supramolecular Systems. Chirality 2015, 27 (5), 339–343. https://doi.org/10.1002/chir.22438.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Jain, A.; Bégin, J.-L.; Corkum, P.; Karimi, E.; Brabec, T.; Bhardwaj, R. Intrinsic Dichroism in Amorphous and Crystalline Solids with Helical Light. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15 (1), 1350. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-45735-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Gd5Rh19Sb12 − a metal-rich antimonide with a Sc5Co19P12 related structure

- Synthesis of schafarzikite-type (PbBi)(Fe1−xMn x )O4: a study on structural, spectroscopic and thermogravimetric properties

- Crystals of Racemic Mimics. Part II. Some Mn(III) and Co(III) compounds crystallizing thus, and remarks on the chirality of atoms containing non-bonded electron pairs as stereogenic centers

- The plumbides SrPdPb and SrPtPb

- In situ crystallization of the tetrahydrate of pentafluoro-benzenesulfonic acid, featuring the Eigen ion (H9O4)+

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Two novel copper(II) supramolecular complexes: synthesis, crystal structures, and Hirshfeld surface analysis

- 6-Bromo-3-butyl-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine and its 4-butyl regioisomer: synthesis and analysis of supramolecular assemblies

- Synthesis, crystal structure, and Hirshfeld analysis of an ultrashort hybrid peptide

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Ni3Sn4 and FeAl2 as vacancy variants of the W-type (“bcc”) structure

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- In this issue

- Inorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Gd5Rh19Sb12 − a metal-rich antimonide with a Sc5Co19P12 related structure

- Synthesis of schafarzikite-type (PbBi)(Fe1−xMn x )O4: a study on structural, spectroscopic and thermogravimetric properties

- Crystals of Racemic Mimics. Part II. Some Mn(III) and Co(III) compounds crystallizing thus, and remarks on the chirality of atoms containing non-bonded electron pairs as stereogenic centers

- The plumbides SrPdPb and SrPtPb

- In situ crystallization of the tetrahydrate of pentafluoro-benzenesulfonic acid, featuring the Eigen ion (H9O4)+

- Organic and Metalorganic Crystal Structures (Original Paper)

- Two novel copper(II) supramolecular complexes: synthesis, crystal structures, and Hirshfeld surface analysis

- 6-Bromo-3-butyl-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine and its 4-butyl regioisomer: synthesis and analysis of supramolecular assemblies

- Synthesis, crystal structure, and Hirshfeld analysis of an ultrashort hybrid peptide

- Corrigendum

- Corrigendum to: Ni3Sn4 and FeAl2 as vacancy variants of the W-type (“bcc”) structure