Abstract

Three experiments investigated the interpretation and production of pronouns in German. The first two experiments probed the preferred interpretation of a pronoun in contexts containing two potential antecedents by having participants complete a sentence fragment starting either with a personal pronoun or a d-pronoun. We systematically varied three properties of the potential antecedents: syntactic function, linear position, and topicality. The results confirm a subject preference for personal pronouns. The preferred interpretation of d-pronouns cannot be captured by any of the three factors alone. Although a d-pronoun preferentially refers to the non-topic in many cases, this preference can be overridden by the other two factors, linear position and syntactic function. In order to test whether interpretive preferences follow from production biases as proposed by the Bayesian theory of Kehler et al. (2008), a third experiment had participants freely produce a continuation sentence for the contexts of the first two experiments. The results show that personal pronouns are used more often to refer to a subject than to an object, recapitulating the subject preference found for interpretation and thereby confirming the account of Kehler et al. (2008). The interpretation results for the d-pronoun likewise follow from the corresponding production data.

1 Introduction

From the perspective of language production, pronouns provide an economical way to refer to referents that are in a highly activated state in the mind of the speaker or writer. From the perspective of language comprehension, in contrast, pronouns pose a challenge because they often lead to referential ambiguity. How this ambiguity is resolved has been a major topic in psycholinguistic research, with a focus on third-person personal pronouns in English. More recently, anaphorically used demonstrative pronouns, as they are found in languages like Dutch, Finnish or German, have attracted a fair amount of attention, too. German, in fact, has two demonstratives of this kind, the more formal dieser and the less formal der. In accordance with the literature on German pronouns, we use the term “d-pronoun” to distinguish der from the demonstrative pronoun dieser. For personal pronouns, we use the abbreviation “p-pronoun”. We focus on the contrast between p- and d-pronouns in the following, but come back to the difference between the two demonstratives in Section 5.

In German discourses as in (1), intuitions as well as experimental results, reviewed below, show that the p-pronoun er preferentially takes the subject as its antecedent whereas the preferred antecedent of the d-pronoun der is not the subject but the object of the prior sentence.

| Peteri | hat | auf | der | Konferenz | einen | ehemaligen | Kollegenj | getroffen. |

| P. | has | at | the | conference | a | former | colleague | met. |

‘Peter met a former colleague at the conference.’[1]

| Eri/Derj | hatte | viel | zu | erzählen. |

| he/ he-det | had | much | to | tell |

| ‘He had much to tell.’ | ||||

The interpretation of pronouns has often been discussed in terms of salience, accessibility, or prominence of the antecedent (see overview in Arnold et al.2013). For ease of presentation, we only speak of prominence in the following, but similar considerations apply to the other notions. As pointed out by Arnold et al., there is some agreement in the literature that a referentially ambiguous pronoun refers to the most prominent referent of the prior discourse. There is no agreement, however, how to define prominence for the purpose of pronoun resolution. We will use the cover term “structural bias” for three important antecedent properties that have been proposed to influence the resolution of p- and d-pronouns (see Gernsbacher and Hargreaves1988; Crawley and Stevenson1990; Crawley et al.1990)[2]:

Syntactic structure

A personal pronoun prefers a subject, a d-pronoun prefers a non-subject as antecedent.

Linear structure

A personal pronoun prefers an initial, a d-pronoun prefers a non-initial NP as antecedent.

Information structure

A personal pronoun prefers a topic, a d-pronoun prefers a non-topic as antecedent.

Numerous studies have shown that the typical antecedent of a p-pronoun is a subject, occurs sentence-initially, and is the sentence topic. For the d-pronoun, the opposite holds; its preferred antecedent is typically the object, sentence-final, and a non-topical referent (e. g. Fukumura and van Gompel2015; Portele and Bader2016).

In example (1), the three relevant dimensions – syntactic, linear, and information structure – are conflated, but this is not always the case. Due to the relatively free word order of German, a sentence can also start with the object instead of the subject. For context sentences with object-before-subject (OS) order, syntactic structure and linear structure make different predictions, in contrast to subject-before-object (SO) context sentences as in the example above. Similarly, the sentence topic is not necessarily the first NP in a sentence.

In addition to “structural biases”, pronoun resolution is subject to “semantic biases”, to use a term from Fukumura and Van Gompel (2010). Semantic biases reflect hearers’ and readers’ efforts to assign coherent interpretations to what they hear or read. The most prominent notion in this regard is the notion of implicit causality introduced by Garvey and Caramazza (1974) (see also, e. g. Stevenson et al.1994; Fukumura and Van Gompel2010; Kehler and Rohde2013). As an example, compare sentence (5-a) with a subject-experiencer verb to sentence (5-b) with an object-experiencer verb (from Stevenson et al.1994).

Ken admired Geoff, because he …

Ken impressed Geoff, because he …

The preferred antecedent is the object for a subject-experiencer verb but the subject for an object-experiencer verb. These preferences cannot be accounted for in terms of structural biases because structurally the two sentences are identical. However, the interpretive preferences can be accounted for in semantic terms. Since because-clauses give a reason for a state or event, hearers and readers resolve the p-pronoun toward the referent causing the psychological state of the experiencer – this is the stimulus argument for both subject- and object-experiencer psych-verbs.

Kehler et al. (2008) have shown that both structural and semantic biases are supported by some data and contradicted by other data. They have therefore proposed a theory that accounts for both kinds of biases on pronoun resolution (see also Kehler and Rohde2013). According to this theory, the choice of an antecedent during language comprehension is based on two probabilities derived from language production – the probability of referring to a particular referent and the probability of using a pronoun for this purpose. These two probabilities are combined by Bayes’ Rule, as shown in (6).

The term on the left-hand side, P(referent|pronoun), is the probability that a given pronoun refers to a particular referent. This is the probability that is needed for language comprehension in situations of referential ambiguity. In such situations, a pronoun and a set of possible antecedents are given, and the task is to choose the referent that the speaker or the writer intended for the pronoun. In order to do this, one computes P(referent|pronoun) – the probability of the referent given the pronoun – for each possible referent, and then selects the referent for which this probability takes the highest value.

With the help of the formula in (6), one can compute P(referent|pronoun) in terms of two probabilities stemming from language production. The term P(referent) gives the probability that a referent of the current discourse will be mentioned next. The term P(pronoun|referent) gives the probability that a pronoun is used for referring to the given referent. The denominator on the right-hand side of the formula in (6), finally, gives the total probability that a pronoun is used. This probability has the function to scale the probabilities of the individual pronouns to sum to one.

Our paper has two major aims. On the empirical level, we want to arrive at a more adequate characterization of the interpretive preferences of the p-pronoun er and the d-pronoun der by disentangling the influence of syntactic, linear, and information structure on pronoun resolution. On the theoretical level, our main aim is to provide a quantitative test of the Bayesian model of pronoun interpretation proposed by Kehler et al. (2008). Rohde and Kehler (2014) have shown that the model provides a good quantitative account for English p-pronouns, but it is an open question whether the model generalizes to other languages and to other types of pronouns.

This paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we review the existing literature on the interpretation of p- and d-pronouns in German. Our review identifies certain gaps in the available experimental evidence. We therefore tested the interpretation of p- and d-pronouns in two sentence completion experiments in which syntactic function, linear order, and information structure were systematically varied. These experiments are presented in Sections 3 and 4. An additional experiment investigating the production of p-pronouns and d-pronouns is presented in Section 5. This experiment provides the data needed to test the theory of Kehler et al. (2008) in Section 6. The paper concludes with a general discussion in Section 7.

2 Prior studies of p-pronouns and d-pronouns

Based on selected corpus examples and intuitive judgments, the theoretical literature concerned with pronouns in German (e. g. Abraham2002; Wiemer1996; Zifonun et al.1997; see Hinterwimmer2015, for a recent account) came to the conclusion that the topic status of the antecedent is the major factor governing the use of p-pronouns and d-pronouns. P-pronouns preferentially refer to referents that have been established as a topic in the prior discourse. D-pronouns, in contrast, signal a topic shift.[3]

In the first quantitative investigation of p-pronouns and d-pronouns, Bosch et al. (2003) provide corpus evidence for this hypothesis, which they dubbed the Complementary Hypothesis:

Complementary Hypothesis (Bosch et al.2003: p. 4)

Anaphoric personal pronouns prefer referents that are established as discourse topics while demonstratives prefer non-topical referents.

In an analysis of the Negra corpus, a corpus of German newspaper articles, Bosch et al. (2003) found a clear difference with regard to the antecedent’s syntactic function. For p-pronouns, the antecedent was a subject most of the time whereas most antecedents of d-pronouns were objects. When taken at face value, these results suggest preferences based on syntactic structure. Since topics are typically subjects, Bosch et al. nevertheless formulated their Complementary Hypothesis in information-structural terms.

In the last ten years, the interpretation of p- and d-pronouns has become the topic of a growing number of experimental studies, leading to a revision of the Complementary Hypothesis. The majority of experimental studies investigated nominative-accusative verbs in contexts as in (8-a), taken from Bosch and Umbach (2007). Most studies included not only context sentences with SO order (8-a-i) but also context sentences with OS order (8-a-ii). The target sentence then started with a p- or a d-pronoun and the preferred antecedent of the p- and/or d-pronoun was determined.

Context sentence

| Der | Chefarzt | untersucht | den | Patienten. | SO order |

| the-nom | head doctor | examines | the-acc | patient |

‘The head doctor is examining the patient.’

| Den | Patienten | untersucht | der | Chefarzt. | OS order |

| the-acc | patient | examines | the-nom | head doctor |

‘The head doctor is examining the patient.’

Continuation sentence

| Er/Der… | |||

| he/he-det… |

Table 1 presents an overview of research on pronoun interpretation in German. This table extends the table provided by Ellert (2013: p. 6), restricted to inter-sentential antecedent-pronoun relations (for intra-sentential anaphora, see e. g. Colonna et al.2012). As shown by Table 1, most research tested context sentences with nominative-initial verbs. In this case, the following conclusions emerge: First, p-pronouns prefer a subject as antecedent if they show a preference at all. Second, d-pronouns show a consistent preference for the non-subject in subject-initial sentences. For subject-final context sentences, in contrast, some studies found a preference for the clause-final subject whereas other studies found a preference for the clause-initial non-subject. The reason for this inconsistent picture is unknown.

Overview of experiments testing the interpretation of p- and d-pronouns following a subject-initial context sentence (SVX) or a non-subject-initial context sentence (XVS). The table shows whether the 1st or the 2nd NP of the context clause is reported as the preferred antecedent of the pronoun. Non-significant effects are marked by “n. s.”

| P-pronoun | D-pronoun | |||

| SVX | XVS | SVX | XVS | |

| Nominative-initial verb in context sentence | ||||

| Bosch and Umbach (2007): completion (unbiased) | 1st (n. s.) | 2nd (n. s.) | 2nd | 1st |

| Bosch and Umbach (2007): reading time (unbiased) | 1st (n. s.) | 2nd (n. s.) | 2nd (n. s.) | 1st (n. s.) |

| Bouma and Hopp (2007): Exp 2 | 1st | 2nd | – | – |

| Wilson (2009) | no pref, | no pref | 2nd | 2nd |

| 2nd → 1st1 | ||||

| Ellert (2013) | 1st | 2nd | 2nd | 2nd |

| Schumacher et al. (2016) | 1st | 2nd | 2nd | 1st |

| Dative-initial verb in context sentence | ||||

| Schumacher et al. (2016)2 | no pref | 1st (adv.) | 1st (non-adv.) | 2nd |

Note:(1) Whereas Wilson (2009) found no preference in her acceptability judgment task, there was a switch from a second- to a first-mentioned preference (2nd → 1st) over the course of time in her visual-world task for the p-pronoun in SVO contexts.(2) Schumacher et al. (2016) tested sentences in which the pronoun was either preceded by an adversative adverbial or not. The preferences given with restrictions in brackets imply that the preferences was only found in the respective condition with/without the adversative adverbial.

Schumacher et al. (2016) go beyond the prior literature by looking at a further factor that may be relevant for the interpretation of p- and d-pronouns – the thematic roles of the respective antecedents (stated in terms of proto roles as proposed in Dowty1991). To this end, they tested sentences with dative-experiencer verbs as shown in (9-a) and (9-a’) (translations as in the original).

| Der | Terrorist | ist | dem | Zuschauer | aufgefallen, | … |

| the | terrorist-nom | is | the | spectator-dat | noticed | |

| ‘It is the terrorist who the spectator noticed, …’ | ||||||

| Dem | Zuschauer | ist | der | Terrorist | aufgefallen, | … |

| the | spectator-dat | is | the | terrorist-nom | noticed, | |

| ‘The spectator has noticed the terrorist, …’ | ||||||

| … | und | zwar | nahe | der | Absperrung. | Aber | er/der | will | eigentlich | nur | die | Feier | sehen. |

| and | in fact | next to | the | barrier. | But | he/he-det | wants | actually | only | the | ceremony | watch. | |

| ‘… in fact next to the barrier. But he actually only wants to watch the ceremony.’ | |||||||||||||

In several conditions, there was no preference at all, but two of the preferences they found ran counter to previous generalizations concerning the interpretive preferences for p- and d-pronouns. First, in OS contexts the p-pronoun preferred the proto-agent/object in the presence of an adversative adverbial. Second, in SO contexts the d-pronoun revealed a preference for the proto-patient/subject for prompts without the adversative adverbial aber. Based on these findings, Schumacher et al. (2016) argue that pronoun resolution is governed by thematic proto-roles: the p-pronoun prefers a proto-agent as antecedent and the d-pronoun a proto-patient.

Much of the literature discussed above captures the interpretation of p- and d-pronouns in information structural terms. However, none of the studies included enough context to unambiguously determine the topicality of the potential antecedents. Conclusions concerning information structure had therefore to rely on assumptions concerning the default association between syntactic structure and information structure. A common assumption in this regard is that the phrase in the initial position of a main clause, the so-called prefield, is the topic. However, recent research into the relationship between information structure and syntactic structure has questioned this assumption (see Frey2004, and Speyer2007, among others). According to this work, the default topic position for German is at the left edge of the middlefield. Only when no other element has a strong preference for appearing in the prefield, like a frame-setting adverbial or a contrastive NP, is the topic NP placed into the prefield. For sentences presented without any context, it is therefore often not possible to decide which phrase is the sentence topic. Since previous work on the resolution of d-pronouns in German mainly comprises materials that did not use appropriate contexts, conclusions concerning the role of topicality are problematic.

The only study that we know of in which p- and d-pronouns were presented in contexts that unambiguously specified the topicality of the potential antecedents is Kaiser and Trueswell’s (2008) study of pronoun interpretation in Finnish. Like German, Finnish has both p-pronouns and d-pronouns. In a questionnaire study and an eye-tracking experiment, Kaiser and Trueswell (2008) investigated short texts as in (10).

| Context sentences 1 and 2 | |||

| Niina | oli | ostoksilla | ruokakaupassa. |

| Niina-nom | was | shopping-adess | grocery-store-iness |

| Jonossa | odottaessaan | hän | näki | takanaan | valkohattuisen | kokin. |

| Line-iness | waiting-iness.poss | she-nom | saw | behind-poss | white-hatted-acc | cook-acc |

| ‘Niina was shopping at the grocery store. While waiting in line, she saw a cook with a white hat behind her.’ | ||||||

Context sentence 3 – SO or OS

| Kokki | töni | jonon | hännillä | seisovaa | leipuria. |

| Cook-nom | pushed | line-gen | tails-adess | standing-part | baker-part |

| ‘The cook pushed a baker standing at the back of the line.’ | |||||

| Kokkia | töni | jonon | hännillä | seisova | leipuri. |

| Cook-part | pushed | line-gen | tails-adess | standing-nom | baker-nom |

| ‘A baker standing at the back of the line pushed the cook.’ | |||||

| Target sentence | ||

| Hän …/Tämä … | ||

| S/he …/he-det … | ||

Each text in the materials of Kaiser and Trueswell (2008) consisted of three context sentences that were followed by a fourth sentence starting either with the p- or the d-pronoun. The first context sentence sets the scene. The second sentence introduces a new referent. In terms of common ground managment (for an overview, see Krifka2007), a new file card is created for this referent. The third context provides further information to be added to the file card of the referent introduced in the second context sentence. This referent is therefore the sentence topic of the final context sentence, with sentence topic understood in the usual way as being the referent the sentence makes a statement about (Reinhart1981; Lambrecht1996). The final context sentence also introduces a second referent, which accordingly belongs to the comment part of this sentence. Both this second referent and the topic referent could serve as antecedent for the pronoun given in the continuation prompt.

In (10), the topic NP of the final context sentence always appears sentence initially whereas its syntactic function varies. It is the subject in SO sentences but the object in OS sentences. As discussed by both Reinhart (1981: 62) and Lambrecht (1996: 200), topics are typically, although not necessarily, subjects. Given an appropriate context, the topic can be realized as an object as well. Topicality is also confounded with givenness in (10). The topic referent in the final context sentence is given because it was already introduced in the preceding sentence whereas the non-topic referent is newly introduced in the final context sentence. Although there is no one-to-one relationship between topicality and givenness, as argued at length by Reinhart (1981), in the typical case topics are given referents.

Both the questionnaire study and the eye-tracking study of Kaiser and Trueswell (2008) found that the p-pronoun prefers a subject as antecedent, independently of the subject’s linear position, whereas the d-pronoun preferentially chooses the post-verbal NP as antecedent, independently of the post-verbal NP’s syntactic function. As in Table 1 for German, the preferences for the p-pronoun and the d-pronoun are thus not complementary. As pointed out by Kaiser and Trueswell (2008), due to the confounding of linear position, givenness and topicality in their materials, the preference observed for the d-pronoun can also be described as a preference for an antecedent that is new or not the sentence topic.

In summary, the available evidence shows that the preferred antecedent of a p-pronoun is typically the subject of the preceding sentence, independently of the topicality of the subject and of its linear position. For d-pronouns, the existing evidence is less conclusive. First, with the exception of Kaiser and Trueswell (2008), the information structural status of the potential antecedents was not well controlled. Second, the competing factors were not fully crossed. Even in Kaiser and Trueswell’s experiments, information structure and linear position were confounded. It therefore remains an open question whether the interpretation of d-pronouns is governed by the topicality of the potential antecedents and/or by their linear position.

The aim of our first two experiments was to determine the preferred interpretation of German p- and d-pronouns in a controlled and systematic way. Following Kaiser and Trueswell (2008), we tightly controlled the information structural status of each potential antecedent. In order to disentangle syntactic function, clausal position, and information structure, we varied not only the position of subject and object in the sentence preceding the pronoun, but also the position of the topic. We therefore investigate a total of three factors: type of pronoun, order of subject and object, and position of the topic. Crossing these three factors results in eight conditions. Because including all eight conditions in a single experiment was not feasible, we ran two experiments that had the same 2×2 design (order × pronoun type). The position of the topic was varied between the two experiments. In Experiment 1, the first NP of the preceding context clause was the sentence topic. In Experiment 2, the final NP was the topic.

3 Experiment 1

Experiment 1 replicates Kaiser and Trueswell (2008) with German materials (see Table 2). Participants had to complete a target sentence starting with either a p- or a d-pronoun. The target sentence was always preceded by three context sentences. Following a scene-setting initial sentence, the second sentence introduced a male character, which was taken up in the third sentence. In addition, the third context sentence introduced a second male character. The first two context sentences were always identical across all conditions. The third context sentence varied according to the factor Order (SO or OS). Independently of the order of subject and object, the topic NP appeared clause-initially and the non-topic NP clause-finally.

A complete stimulus item for Experiment 1.

| Context sentences 1 and 2 | ||||||||||||

| Sabine war am Sonntag im Zirkus. Bevor die Aufführung begann, hatte sie schon einen Clown herumlaufen sehen. | ||||||||||||

| ‘Sabine visited a circus on Sunday. Before the show began, she saw a clown walking around.’ | ||||||||||||

| Context sentence 3 | ||||||||||||

| SO | Der | Clown | umarmte | einen | Mann, | der | ganz | wirre | Haare | hatte. | ||

| the-nom | clown | hugged | a-acc | man | who | totally | tousled | hair | had | |||

| OS | Den | Clown | umarmte | ein | Mann, | der | ganz | wirre | Haare | hatte. | ||

| the-acc | clown | hugged | a-nom | man | who | totally | tousled | hair | had | |||

| Target sentence: | Er | hat... | (p-pronoun) |

| Der | hat... | (d-pronoun) |

If p- and d-pronouns in German behave the same way as they do in Finnish, we expect similar results as the ones found by Kaiser and Trueswell (2008). First, the preferred antecedent of the p-pronoun should be the subject of the preceding clause (the clown in SO sentences, a man, who… in OS sentences). For the d-pronoun der, a general preference for the second NP is expected (a man in both SO and OS sentences).

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

Twenty students at the Goethe-University Frankfurt participated in Experiment 1 for course credit. In this and the following experiments, participants were always native speakers of German and naive with respect to the purpose of the experiment.

3.1.2 Materials

We constructed 16 experimental items, each consisting of three context sentences, as illustrated in Table 2 (see the online supplement for the complete materials). The first sentence introduced a female character using a proper name or indefinite NP. In the second sentence, the first of two masculine characters was introduced using an indefinite NP. The critical context sentence 3 mentioned two male characters. The one already introduced in the second sentence was taken up again by a definite NP; a second male character was introduced by an indefinite NP. Context sentence 3 varies the order of subject and object but keeps information structure constant. Thus, the definite topic NP always appeared in sentence-initial position, as subject in SO sentences and as object in OS sentences. The non-topical indefinite NP always appeared sentence-finally, as object in SO and as subject in OS sentences. To increase the naturalness of the experimental items, a relative clause modified the indefinite NP of sentence 3. Context sentence 3 was followed by the target sentence, which was an incomplete sentence starting with either Er hat ‘he has’ or Der hat ‘he-det has’. We included the finite auxiliary in addition to the pronoun in order to prevent participants from producing definite NPs, which is possible in the case of the d-pronoun der because der is also a form of the definite article.

Crossing the order of subject and object in the last context sentence (SO versus OS) and the type of pronoun (p- versus d-pronoun) in the target sentence resulted in four different versions of each experimental item. The 16 items were distributed across four lists according to a Latin square design. Each list contained exactly one version of each sentence and an equal number of sentences in each condition. 32 filler items that also contained female and inanimate entities in the last context sentence were added to each experimental list in such a way that experimental items were always separated by at least one filler item.

3.1.3 Procedure

Participants received a written questionnaire and were asked to read the contexts and complete the target sentences by writing natural-sounding continuations. Participants completed the questionnaires during regular class sessions. Completing a questionnaire took about 20 minutes.

3.1.4 Scoring

Two raters, the second author and a student assistant who was naive regarding our research questions, coded participants’ continuations according to which of the two characters mentioned in context sentence 3 (first or second mentioned NP) they chose as the referent for the pronoun. In case of ambiguity or disagreement between the two annotators as to which of the two NPs was the intended referent of the p- or d-pronoun, the sentence was marked and excluded from the analysis. Example continuations are shown in the online supplement. For three items, participants did not give a continuation. 47 continuations were excluded from the analysis because the raters did not agree and 6 continuations were excluded because both raters judged the continuation as ambiguous. The final data set contained a total of 264 continuations, covering 82.5 % of the total number of continuations. The numbers of continuation per condition are shown in Figure 1.

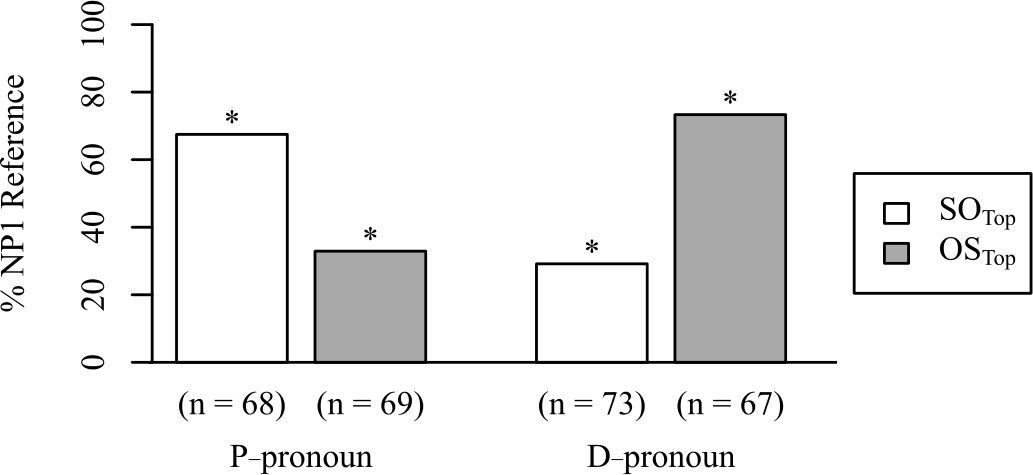

Percentages of completions referencing NP1 of context sentence 3 in Experiment 1. An asterisk indicates that the respective percentage differs significantly from 50% (chance performance).

3.2 Results

In the literature on pronoun interpretation, there are two different perspectives one can take when analyzing the kind of data gathered in completion experiments like Experiment 1. First, one can determine the preferred referent of a pronoun under all combinations of the factor levels. The question that arises under this perspective is whether the choice from a set of potential referents differs from chance performance. Second, one can ask how the different factors modulate the outcome variable. For example, does the probability of choosing a particular referent differ across the levels of a particular factor? Since both perspectives are necessary for a full understanding of the results, we present both types of analyses.

All statistical analyses reported in this paper were conducted using the statistics software R (R Core Team2016). For the inferential statistics, we computed generalized linear mixed models using the R package lme4 (Bates et al.2015). Figure 1 shows the percentages of completions that referred back to the referent of the first NP in each of the four conditions of Experiment 1. An asterisk in this and all following figures indicates that the choice in the given condition differs from chance. We tested for chance performance by running a generalized linear mixed-effects model with the interaction term as the only fixed effect. In this model, every factor combination is allotted a separate parameter and the statistical test of the parameter tells us whether the parameter differs significantly from zero, which, when log odds are translated into proportions, corresponds to a value of 0.5. For the p-pronoun er, a significant subject preference is observed in OS contexts. The numerically visible advantage for the subject in SO sentences is not significantly different from chance performance. For the d-pronoun der, the second NP is the preferred antecedent following both SO and OS contexts. In both cases, the observed preferences are significantly different from chance.

We ran a second generalized linear mixed model with both main factors and the interaction term as fixed effects, using effect coding (i. e., the intercept represents the unweighted grand mean, fixed effects compare factor levels to each other). In addition, we included random effects for items and subjects with maximal random slopes supported by the data, following the strategy proposed in Bates et al. (2015). The response variable was again defined as reference to the referent of the first NP. We report the full model summary and give the

Table 3 summarizes the results of the statistical analysis, which reveals a significant main effect of Pronoun, no significant main effect of Order, and a significant interaction between Pronoun and Order. The interaction reflects the finding that in SO contexts, reference to the first NP occurred much more often for the p-pronoun than for the d-pronoun (59 % versus 10 %;

Mixed-effects model for Experiment 1 with

| Fixed effects | Estimate | Std. Error | z value | p (LRT) | ||

| Intercept | 1.2364 | 0.2504 | 4.939 | <.001 | – | – |

| Pronoun | −1.6625 | 0.3951 | −4.208 | <.001 | 17.03 | <.001 |

| Order | 0.1646 | 0.5408 | 0.304 | n. s. | 0.01 | n. s. |

| Pronoun × Order | −3.5700 | 0.9323 | −3.829 | <.001 | 11.50 | <.001 |

3.3 Discussion

The results of Experiment 1 show clear differences between p- and d-pronouns. The p-pronoun was preferably resolved towards the subject of the prior sentence. However, it is only in OS contexts that we see a significant preference. In SO contexts, there is only a numerical difference. This pattern is in accordance with the prior findings from German as summarized in Table 1. For example, Bouma and Hopp (2007) found a rate of 64 % subject antecedents for the p-pronoun following an SO main clause. The d-pronoun, on the other hand, showed a robust preference for the final NP of the last context sentence. This preference for the final NP was modulated by the syntactic function of the referent. The preference was extremely strong in SO sentences, that is, when the final NP was an object. It was significantly weakened in OS sentences, that is, when the final NP was the subject. Thus, although the d-pronoun preferred the final NP as antecedent independent of its syntactic function, we still see the often noted object-orientation of d-pronouns at work.

The general pattern we found for the p- and d-pronoun resembles the one found by Kaiser and Trueswell (2008) for Finnish. P-pronouns seem to prefer subjects, whereas d-pronouns prefer post-verbal NPs. The preference of the d-pronoun is modulated by the syntactic function of the referent with objects being preferred over subjects. A similar finding was obtained by Kaiser and Trueswell (2008). The preference for the d-pronoun can be captured either in terms of information structure or in terms of linear position. A decision between information structure and linear position is not possible because they were confounded in Experiment 1 in the same way as in Kaiser and Trueswell (2008). The purpose of the next experiment was to disentangle these two factors.

4 Experiment 2

A complete stimulus item for Experiment 2.

| Context sentences 1 and 2 | ||||||||||

| Sabine war am Sonntag im Zirkus. Bevor die Aufführung begann, hatte sie schon einen Clown herumlaufen sehen. | ||||||||||

| ‘Sabine visited a circus on Sunday. Before the show began, she saw a clown walking around.’ | ||||||||||

| Context sentence 3 | ||||||||||

| SO | Ein | Mann, | der | ganz | wirre | Haare | hatte, | umarmte | den | Clown. |

| a-nom | man | who | totally | tousled | hair | had | hugged | the-acc | clown. | |

| OS | Einen | Mann, | der | ganz | wirre | Haare | hatte, | umarmte | der | Clown. |

| a-acc | man | who | totally | tousled | hair | had | hugged | the-nom | man. | |

| Target sentence: | Er | hat... | (p-pronoun) |

| Der | hat... | (d-pronoun) |

Experiment 2 investigates an information-structural mapping that has been neglected so far. The topic appears in sentence-final position whereas the non-topic appears in sentence-initial position.[4] Having the topic in final position and varying the order of subject and object allows us to disentangle effects of linear position and information structure. If the d-pronoun shows an anti-topic bias, as assumed in much of the prior literature, the first NP should be its preferred antecedent for both SO and OS context sentences. On the other hand, if a d-pronoun’s linear position governs its interpretation, the final NP should be preferred throughout. For the p-pronoun, we again expect a preference for subject antecedents.

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Participants

Experiment 2 had twenty participants, who were all students at the Goethe-University Frankfurt and had not participated in Experiment 1.

4.1.2 Materials

The material for Experiment 2 was identical to the material of Experiment 1 with one exception (see the online supplement for the complete materials). As can be seen in Table 4, the order of the topic and the new NP in the final context sentence was reversed. Thus, in Experiment 2, the new and indefinite NP always appeared clause-initially and the definite topic NP appeared clause-finally. Crossing the two factors Order (SO versus OS) and Pronoun (p-pronoun versus d-pronoun) resulted in four versions of each experimental stimulus. The experimental items were again distributed onto four different questionnaires that contained the same 32 filler items as the first experiment.

4.1.3 Procedure and scoring

The experimental procedure and the scoring procedure were identical to those used in Experiment 1. Example continuations are shown in the online supplement. For five items, participants did not give a continuation. The agreement rate of the two raters amounted to 88 % of participants’ continuations in Experiment 2. 36 continuations were excluded due to rater disagreement and 2 continuations were excluded because they were classified as ambiguous by both raters. This left 277 continuations for the analysis. The numbers of continuations in each condition are given in Figure 2.

Percentages of completions referencing NP1 of context sentence 3 in Experiment 2. An asterisk indicates that the respective percentage differs significantly from 50% (chance performance).

4.2 Results

The results of Experiment 2 were statistically analyzed in the same way as for Experiment 1 and we again report an analysis regarding the different preferences of the pronouns as well as a multivariate analysis. Figure 2 shows the percentages of completions for Experiment 2 in the different conditions. The p-pronoun and the d-pronoun show complementary preferences. The p-pronoun shows a subject preference whereas the d-pronoun shows an object preference. For both pronouns, the preference is observed in both SO and OS contexts and is thus independent of order. All preferences in Experiment 2 were significantly different from chance.

Table 5 summarizes the mixed-effect model for Experiment 2. The two main effects were not significant, but the interaction between them was. Pairwise comparisons show that in SO contexts, the rate of reference to the second NP was higher for the d-pronoun than for the p-pronoun (71 % versus 32 %;

Mixed-effects model for Experiment 2 with

| Fixed effects | Estimate | Std. Error | z value | p(LRT) | ||

| Intercept | 0.05068 | 0.18982 | 0.267 | n. s. | – | – |

| Pronoun | −0.07666 | 0.19060 | −0.402 | n. s. | 0.06 | |

| Order | −0.14366 | 0.28602 | −0.502 | n. s. | 0.19 | |

| Pronoun×Order | 1.14906 | 0.21916 | 5.243 | <.001 | 20.94 | <.001 |

4.3 Discussion

In line with the prior literature and Experiment 1, Experiment 2 revealed a subject preference for the p-pronoun er independent of order. For the d-pronoun, the observed pattern is different from the one found in Experiment 1, where the d-pronoun showed a preference for the second-mentioned NP. In Experiment 2, in contrast, the d-pronoun showed an order-independent preference for the object. The pattern of preferences is reflected in the interaction of the multivariate analysis, which shows that both pronouns are influenced by the word order of the last context sentence. The p-pronoun was more often resolved towards the first NP in SO contexts compared to OS contexts. The d-pronoun, on the other hand, was less often resolved towards the first NP in SO contexts compared to OS contexts.

The pattern we find for the d-pronoun in Experiment 2 demonstrates that neither information structure nor linear position alone can account for the interpretation of d-pronouns. In the SO context, the d-pronoun favored the final object NP, even though it was the sentence topic in Experiment 2. This argues against a sole anti-topic bias. In OS contexts, however, we found a preference towards the initial object NP, which was not the topic of the sentence. In this case, the preference found for the d-pronoun works against the typically preferred final position of the d-pronoun’s antecedent. From Experiment 2 alone, one could conclude that the d-pronoun prefers an antecedent with the syntactic function of an object, but this conclusion is not compatible with Experiment 1, which revealed a preference for the final NP independent of the NP’s syntactic function. In sum, when both experiments are considered together, the conclusion is that none of the structural properties alone – linear position, syntactic function, and topicality – can capture the interpretive preferences of the d-pronoun. Whereas the interpretation pattern found for the p-pronoun may be explained by just one factor – syntactic function – our results show that for the d-pronoun, all three factors – syntactic function, linear position, and topicality – influence the preferred interpretation.

5 Experiment 3

According to the Bayesian theory of pronoun resolution proposed by Kehler et al. (2008), the choice of a referent for a referentially ambiguous pronoun during language comprehension is based on two production probabilities, the probability of each potential referent to be mentioned again and the probability of using a pronoun for that purpose. The main aim of Experiment 3 was to provide empirical estimates of the production probabilities that are needed for a quantitative assessment of the Bayesian theory of pronoun resolution. Experiment 3 therefore used the same context sentences as Experiments 1 and 2 and changed only the continuation prompt. Instead of including a pronoun in the prompt, Experiment 3 presented a blank line for participants to write down a continuation sentence. Participants were thus completely free as to how they continued the context. Experiments of this kind yield the data needed to estimate the two production probabilities required to test the Bayesian formula in (6). First, the next-mention bias p(referent) of a referent mentioned in the context can be estimated by the frequency with which the referent is mentioned again. Second, for each referent that is mentioned again, one can compute the frequencies of the alternative anaphoric expressions in the continuation sentences produced by the participants and thus estimate p(pronoun|referent).

The next-mention bias is mainly determined by the meaning of a sentence. For example, the notion of implicit causality discussed in the introduction captures the contribution of verbs to the next-mention bias, as illustrated by example (5). A further important factor is the coherence relation of a clause to the prior context. When the causal connector because is replaced by the consequential connector so in examples like (5), the preference switches from stimulus to experiencer (Fukumura and Van Gompel2010). In accordance with a common practice in experimental investigations of d-pronouns, we relied on our intuitions when selecting verbs for the final context sentence of our materials. We only used verbs without an implicit causality bias according to our intuition, comparable to the non-IC verbs of Rohde and Kehler (2014), and therefore expect that subject and object are taken up again about equally often in the continuation sentence.

With regard to the choice of a referring expression, the syntactic function of the antecedent has been repeatedly found to be the main determinant in English (e. g., Stevenson et al.1994, Fukumura and Van Gompel2010). The probability of using a pronoun is much higher when referring to the subject of the preceding clause than when referring to the object. The semantic factors that have a strong effect on the next-mention-bias have no effect (Stevenson et al.1994; Fukumura and Van Gompel2010; Rohde and Kehler2014) or at most a small effect (Rosa and Arnold2017) on this choice. Given what is known from corpus studies of German (Bosch et al.2003; Portele and Bader2016), we expect a similar effect in the current experiment. In addition, Rohde and Kehler (2014) found an effect of topicality on the rate of pronoun use when comparing references to the subject of either an active or a passive clause.

5.1 Method

5.1.1 Participants

Forty-four students at the Goethe-University Frankfurt participated in Experiment 3 for course credit. None of the participants of Experiment 3 had participated in the two prior experiments.

5.1.2 Materials

The material for Experiment 3 was identical to the material of Experiments 1 and 2 with the exception of the continuation prompt, which was a blank line in Experiment 3. Since the prompt did not contain a pronoun, the factor pronoun type was dropped. Experiment 3 had therefore a two-factorial design with the factors Order (SO versus OS) and Topic (Topic First and Topic Last). The experimental manipulations were confined to the third context sentence. The experimental items in the condition Topic First were taken from Experiment 1 and the items in the condition Topic Last from Experiment 2. An original stimulus item in all four versions is shown in Table 6. Four experimental lists were created according to a Latin square design. Each experimental list was combined with 24 of the 32 filler items of the preceding experiments.

A complete stimulus item for Experiment 3.

| Context sentences 1 and 2 | ||||||||||

| Sabine war am Sonntag im Zirkus. Bevor die Aufführung begann, hatte sie schon einen Clown herumlaufen sehen. | ||||||||||

| ‘Sabine visited a circus on Sunday. Before the show began, she saw a clown walking around.’ | ||||||||||

| Context sentence 3 | ||||||||||

| Topic = First NP | ||||||||||

| SO | Der | Clown | umarmte | einen | Mann, | der | ganz | wirre | Haare | hatte. |

| the-nom | clown | hugged | a-acc | man | who | totally | tousled | hairs | had | |

| OS | Den | Clown | umarmte | ein | Mann, | der | ganz | wirre | Haare | hatte. |

| the-acc | clown | hugged | a-nom | man | who | totally | tousled | hairs | had | |

| Topic = Second NP | ||||||||||

| SO | Ein | Mann, | der | ganz | wirre | Haare | hatte, | umarmte | den | Clown. |

| a-nom | man | who | totally | tousled | hairs | had | hugged | the-acc | clown. | |

| OS | Einen | Mann, | der | ganz | wirre | Haare | hatte, | umarmte | der | Clown. |

| a-acc | man | who | totally | tousled | hairs | had | hugged | the-nom | man. | |

| Continuation prompt: _______________________________________________________ |

5.1.3 Procedure

Experiment 3 used a sentence production task. Four questionnaires were created based on the four sentence lists. An instruction included on the first page of the questionnaire told participants to read each context and then to write down a sensible continuation sentence. The instruction required participants to start a new sentence but did not impose any constraints with regard to the form and content of the continuation sentence. Participants completed the questionnaires either during a regular class session or in the psycholinguistics lab at the Goethe-University Frankfurt after they had participated in an unrelated online experiment. It took participants about 20 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

5.1.4 Scoring

66 of 704 trials were excluded because no continuation was given (

For all continuations, we classified the linguistic expression used for referring back to the referent according to the following categories: proper name (Maria), p-pronoun (er), d-pronoun (der), demonstrative pronoun (dieser), and definite NP (e. g. der Junge).

5.2 Results

The main aim of Experiment 3 was to obtain the data necessary to test the Bayesian model of Kehler et al. (2008). However, we also include a short discussion of the results independent of this particular aim because to our knowledge data of this sort have not been gathered for German pronouns before and the results are therefore of more general interest. The results were again analyzed using generalized mixed models. For the sake of brevity, we only present analyses for the variables that are of main interest.

5.2.1 Choice of referent

Table 7 shows how often the different referents of the context sentences were the first or only referent mentioned in the continuation. Overall, the female character of the initial context sentence was mentioned again – either first or alone – in 49 % of all continuations, which is the highest value for all referents. With 22 % the second highest value is observed for the second referent of the final context sentence. The first referent of the final context sentence was rementioned in 16 % of all continuations and thus somewhat less often than the second referent. In 13 % of all continuations, at least two of the three prior referents were referred to by a single NP.

Percentages of referents from the context occurring as the only or first referent in the continuations of Experiment 3. Raw counts are given in parentheses.

| Referent | 1. NP = Topic | 2. NP = Topic | ||

| SO | OS | SO | OS | |

| Female NP | 53 (85) | 56 (87) | 43 (70) | 43 (69) |

| 1. NP | 13 (21) | 6 (10) | 20 (32) | 25 (41) |

| 2. NP | 23 (36) | 22 (34) | 24 (39) | 17 (28) |

| Multiple | 11 (18) | 15 (23) | 12 (20) | 15 (24) |

For the two referents of main interest, namely the referents of NP1 and NP2 of the final context sentence, Table 8 shows two separate logistic mixed effects models with either “reference to NP1” or “reference to NP2” as response variable. For reference to NP1, the factor Topic Position was significant. NP1 was rementioned more often when the topic occurred in final position than when it occurred in initial position (23 % versus 10 %). The interaction between Topic Position and Order was also significant. This reflects the finding that Topic Position had no significant effect for SO context sentences (

Mixed-effects model for choice of referent in Experiment 3 with

| Fixed effects | Estimate | Std. Error | z value | p(LRT) | ||

| Response variable ‘Reference to NP1’ | ||||||

| Intercept | −2.330 | 0.290 | −8.04 | <.001 | ||

| Topic Position | −1.224 | 0.377 | −3.25 | <.01 | 9.15 | <.01 |

| Order | 0.141 | 0.416 | 0.34 | n. s. | 0.02 | |

| Topic Position×Order | 1.253 | 0.564 | 2.22 | <.05 | 5.16 | <.05 |

| Response variable ‘Reference to NP2’ | ||||||

| Intercept | −1.551 | 0.176 | −8.80 | <.001 | ||

| Topic Position | 0.125 | 0.206 | 0.61 | n. s. | 0.29 | |

| Order | 0.238 | 0.369 | 0.65 | n. s. | 0.40 | |

| Topic Position×Order | −0.459 | 0.412 | −1.11 | n. s. | 1.20 | |

As a final point, let us consider the issue of semantic bias. As pointed out above, semantic properties of verbs can exert a strong influence on the resolution of ambiguous pronouns. This is especially true for so-called implicit causality verbs as in (5). Across all conditions of Experiment 3, the subject was mentioned again in 18 % and the object in 20 % of all continuations. This shows that we succeeded in construction materials without a next-mention bias due to verb semantics.

5.2.2 Choice of referential expression

Table 9 shows the distribution of the different types of referential expressions for the three human referents of the context. The female character was rementioned using the original proper name in slightly more than 80 % of all cases and using a p-pronoun in the remaining cases. The experimental manipulations had no influence on the referential expression chosen for the female character.

Percentages of referential expressions chosen in Experiment 3 for the female character of the first sentence and for the referents of the first and the second NP of the last context sentence. Raw counts are given in parentheses.

| Female character | Topic = 1. NP | Topic = 2. NP | ||

| SO | OS | SO | OS | |

| P-pronoun | 26 (22) | 22 (19) | 24 (17) | 19 (13) |

| Proper name | 74 (63) | 78 (68) | 76 (53) | 81 (56) |

| Referent of NP1 | Topic = 1. NP | Topic = 2. NP | ||

| SO | OS | SO | OS | |

| P-pronoun | 67 (14) | 30 (3) | 41 (13) | 22 (9) |

| D-pronoun | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dem. pronoun | 0 | 0 | 9 (3) | 12 (5) |

| Definite NP | 33 (7) | 70 (7) | 50 (16) | 66 (27) |

| Referent of NP2 | Topic = 1. NP | Topic = 2. NP | ||

| SO | OS | SO | OS | |

| P-pronoun | 11 (4) | 47 (16) | 10 (4) | 43 (12) |

| D-pronoun | 0 | 0 | 3 (1) | 0 |

| Dem. pronoun | 17 (6) | 0 | 13 (5) | 0 |

| Definite NP | 72 (26) | 53 (18) | 74 (29) | 57 (16) |

With regard to references to the referent of the first or the second NP of the final context sentence, consider first the percentages of p-pronoun use. For the statistical analysis, we took the subset of completions making reference to the NP1 or NP2 referent and introduced Referent as a third factor with the levels “NP1” and “NP2” in addition to the factors Topic Position and Order. The logistic mixed effects model with these three factors and p-pronoun use as response variable is shown in Table 10. The rate of p-pronoun use was higher for OS than for SO sentences, resulting in a significant main effect of Order, and the rate of p-pronoun use was higher for NP1 referents than NP2 referents, but this effect was only significant in the model comparison. Importantly, the two main effects of Order and Referent have to be qualified by a significant interaction. For SO context sentences, p-pronouns were more often used for referring to the NP1 referent than for referring to the NP2 referent (50 % versus 11 %). For OS sentences, it was the reverse; NP2 referents were more often referenced by a p-pronoun than NP1 referents (45 % versus 23 %). Since the syntactic functions of NP1 and NP2 are reversed in SO and OS sentences, this interaction amounts to a higher rate of p-pronoun use for reference to the subject than for reference to the object.

Mixed-effects model for using a p-pronoun to refer to the referent of NP1 or NP2 in Experiment 3 with

| Fixed effects | Estimate | Std. Error | z value | p(LRT) | ||

| Intercept | −1.2076 | 0.2723 | −4.43 | <.001 | ||

| Topic Position | 0.2252 | 0.4923 | 0.46 | n. s. | 0 | |

| Order | −1.7588 | 0.4897 | −3.59 | <.001 | 24.6 | <.001 |

| Referent | 1.0957 | 0.8037 | 1.36 | n. s. | 25.4 | <.001 |

| Topic Position×Order | 0.0456 | 0.9138 | 0.05 | n. s. | 0.31 | |

| Topic Position×Referent | 1.2180 | 1.4462 | 0.84 | n. s. | 0.78 | |

| Order×Referent | 6.9094 | 1.7898 | 3.86 | <.001 | 21.90 | <.001 |

| Topic Position×Order×Referent | 2.3301 | 2.9321 | 0.79 | n. s. | 1.43 |

As shown in Table 9, d-pronouns were produced extremely rarely whereas demonstrative pronouns occurred with some regularity. In total there were 19 continuations with a demonstrative pronoun and one continuation with a d-pronoun. In 17 out of these 20 continuations, the pronoun referred back to the referent of the object NP; the three subject references were all to non-topical subjects. In 14 out of the 20 continuations under consideration, the pronoun referred back to the non-topic; all topics that were referred to by a demonstrative pronoun were objects. These findings are in accordance with prior claims that d(emonstrative) pronouns prefer non-topical objects as antecedents, but the preferences are not categorical. We do not present a statistical analysis of these data because logistic regression is not applicable to data with empty cells.

5.3 Discussion

The main purpose of Experiment 3 was to provide the production data necessary to test whether the Bayesian theory of pronoun resolution proposed by Kehler et al. (2008) can account for the interpretation data of Experiments 1 and 2. This test is presented in the next section. In addition, Experiment 3 yielded several new findings concerning the next-mention bias and the choice of a referential expression.

With regard to the choice of a referential expression, we replicated the finding from English that the main factor governing the use of p-pronouns is the syntactic function of the antecedent. An additional finding was that d-pronouns and demonstrative pronouns were produced with low frequency, with demonstrative pronouns outnumbering d-pronouns by far. In the literature on German pronoun resolution, d-pronouns have played a major role whereas demonstrative pronouns have been neglected. In interpretation experiments, the referential form is chosen by the researcher(s) and the participants just have to interpret whatever pronoun they are given. In production experiments, like Experiment 3, the decision of a referential form is given to the participants. Experiment 3 could therefore reveal a preference for demonstrative pronouns to d-pronouns. We suspect that this preference is a matter of style. Demonstrative pronouns belong to a more formal register whereas d-pronouns are less formal and occur with a much higher frequency in spoken than in written language (Bosch and Umbach2007; see also Ahrenholz2007). Furthermore, d-pronouns are considered as impolite when referring to human referents (Dudenredaktion1997), although in fact most d-pronouns have human referents even in written texts (Portele and Bader2016). When estimating p(pronoun|referent) in the following section, we will add the frequencies for d-pronouns and demonstrative pronouns in order to get more stable estimates.

6 A test of the Bayesian theory

A central question of current psycholinguistic research concerns the relationship between language comprehension and language production. For a long time, comprehension and production have been investigated in relative isolation from each other. This situation has changed, however, and several theories have been proposed relating language comprehension to language production (e. g., Pickering and Garrod2013; MacDonald2013; Levy2008). In many of these approaches, expectations about how a sentence or a discourse will proceed provide the crucial link between production and comprehension.

The Bayesian theory of pronoun resolution proposed by Kehler et al. (2008) is an outstanding example of a theory explaining certain aspects of language comprehension in terms of expectations derived from language production. From the viewpoint of language comprehension, encountering a referentially ambiguous pronoun faces the language comprehender with the task of choosing the pronoun’s intendent referent from a set of potential referents. For example, when reading the pronoun er ‘he’ in (11), a reader must decide whether the pronoun refers to the referent of der Clown (CLOWN in the following) or the referent of einen Mann, der wirre Haare hatte (MAN in the following).

| [Der | Clown]i | umarmte | [einen | Mann, | der | wirre | Haare | hatte]j. | Eri/j | … | ||

| the | clown | hugged | a | man | who | tousled | hair | had | he |

According to Kehler et al. (2008), this decision is made by computing the conditional probability P(referent|pronoun) – the probability that a particular referent is the referent of a given pronoun – for each possible referent and then choosing the referent for which this probability is highest. In our example, this means determining which of the two probabilities P(CLOWN|er) and P(MAN|er) is higher.

Since P(referent|pronoun) cannot be computed directly, it is computed indirectly by applying Bayesian reasoning according to the formula in (12) (repeated from above).

According to this formula, the conditional probability P(referent|pronoun) can be computed from two probabilities that both reflect expectations with regard to language production. Empirical estimates for these probabilities were obtained in Experiment 3. The first probability – P(referent) – reflects the expectation that the referent will be mentioned in the next sentence. In our example (11), the reader will have formed expectations of how probable it is that the clown is mentioned in the next sentence and how probable it is that the man with tousled hair is mentioned again. Empirical estimates for these probabilities are provided by the next-mention biases that were found in Experiment 3 for the different referents given in the context.

The second probability – P(pronoun|referent) – reflects the expectation that a pronoun is used for referring to the given referent. For example, P(er|CLOWN) is the probability that a p-pronoun is used in case the clown is mentioned next. P(er|MAN) is accordingly the probability that a p-pronoun is used to refer the man in case the man is mentioned again. These probabilities can be estimated from Table 9 of Experiment 3. This table shows for each referent that is mentioned again how frequent the different referential expressions were used.

If the Bayesian theory of pronoun resolution proposed by Kehler et al. (2008) is correct, applying the formula in (12) to the production results of Experiment 3 should predict the interpretation results obtained in Experiments 1 and 2. By way of illustration, consider the SO context condition from Experiment 1. The final context sentence and the sentence fragment to complete are repeated in (13), together with the relevant probabilities.

What we want to know are the two probabilities P(CLOWN|er) and P(MAN|er) – that is, the probabilities of er referring to either CLOWN or MAN. To compute P(CLOWN|er), we need to know P(CLOWN) and P(er|CLOWN). P(CLOWN) is the probability that the clown mentioned in the context sentence will be mentioned again in the continuation sentence. As shown in Table 7, the referent CLOWN was mentioned again in 13 % of all cases in Experiment 3. This frequency serves as estimate for P(CLOWN). P(er|CLOWN) is the probability that a p-pronoun is used for referring to the referent CLOWN in case this referent is mentioned again. As shown in Table 9, a p-pronoun was used in 67 % of all cases to refer to CLOWN, and P(er|CLOWN) can therefore be estimated as 0.67. For the referent MAN, the corresponding values are P(MAN) = 0.23 and P(er|MAN) = 0.11.

For the sentence in (13), the referent of the non-topical clause-final object NP (MAN) has a higher probability of being mentioned next then the referent of the topical clause-initial subject NP (CLOWN) (0.23 versus 0.13). On the other hand, it is much more likely to use a p-pronoun for referring to the subject referent (CLOWN) than for referring to the object referent (MAN) (0.67 versus 0.11). The joint probability that the CLOWN is mentioned next and a pronoun is used for this purpose – that is, P(er|CLOWN) × P(CLOWN) – is therefore higher than the joint probability that the MAN is mentioned next using a pronoun (0.087 versus 0.025).

The two probabilities 0.087 versus 0.025 do not sum to 1 because the two cases considered so far – CLOWN referred to by er and MAN referred to by er – do not exhaust the possibilities of the speaker. For example, a different expression could be used to refer to each of the referents, or a different referent, for example the woman mentioned in the first sentence in our experimental items, could be mentioned. From the perspective of language comprehension, however, only the two cases considered above are relevant. The pronoun er is given in the input, and therefore alternative expressions need not be considered. Furthermore, due to morpho-syntactic constraints, only the two referents CLOWN and MAN are possible antecedents for the pronoun er. The two probabilities P(CLOWN|er) and P(MAN|er) therefore have to sum to 1. This is achieved by dividing each joint probability P(pro|ref) × P(ref) by the total probability that a pronoun is used, that is, by the sum of P(pro|ref) × P(ref) for all potential referents. This has the effect that the probabilities for the individual referents are scaled to add up to 1. The final probabilities are P(CLOWN|er) = 0.78 and P(MAN|er) = 0.22. These probabilities can then be compared to the proportions observed in the interpretation experiments. For the example under consideration, the first referent of the context sentence is predicted to be chosen as referent of the pronoun in 78 % of the cases and the second referent in the remaining 22 %. This correctly predicts a subject preference for the p-pronoun.

The corresponding computations for the d-pronoun are shown in (14). The two probabilities P(CLOWN) and P(MAN) are the same as for the p-pronoun in (13) because the decision of which referent to mention next is not contingent on the choice of a referential expression. As for this choice, neither a d-pronoun nor demonstrative pronoun was ever used in Experiment 3 for referring to the referent CLOWN, that is, the referent of the subject NP. Thus, P(der|CLOWN) = 0. The joint probability P(CLOWN) × P(der|CLOWN) – that is, mentioning CLOWN again by means of d(emonstrative) pronoun – is accordingly also 0. The corresponding values for the referent MAN, that is, the referent of the object NP, are P(der|MAN) = .17 and P(MAN) × P(der|MAN) = 0.037. As final probabilities, we thus get P(CLOWN|der) = 0 and P(MAN|der) = 1. This predicts that the referent of the object NP should always be taken as antecedent of the d-pronoun.

For each of the eight experimental conditions of Experiments 1 and 2, Table 11 lists all probabilities needed to assess the validity of the Bayesian formula. The last two columns give the predicted and the observed proportions of reference to either the first or the second NP.[5] These proportions (converted to percentages) are plotted in Figure 3 to facilitate the evaluation of the Bayesian model. Overall, we see a good fit between data and model, as confirmed by a high R2 value of 0.95 (

Application of the Bayesian formula; the probabilities are estimated from the results of Experiment 3.

| Topic | Pronoun | Order | Referent | P(ref) | P(pro|ref) | P(pro|ref) × | P(ref|pro) | |

| P(ref) | pred. | obs. | ||||||

| First position (Experiment 1) | P-pronoun | SO | 1. NP | 0.13 | 0.67 | 0.088 | 0.78 | 0.59 |

| 2. NP | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.025 | 0.22 | 0.41 | |||

| OS | 1. NP | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.010 | 0.16 | 0.27 | ||

| 2. NP | 0.22 | 0.47 | 0.104 | 0.84 | 0.73 | |||

| D-pronoun | SO | 1. NP | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.07 | |

| 2. NP | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.038 | 1.00 | 0.93 | |||

| OS | 1. NP | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.23 | 0.31 | ||

| 2. NP | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.77 | 0.69 | |||

| Second position (Experiment 2) | P-pronoun | SO | 1. NP | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.081 | 0.76 | 0.68 |

| 2. NP | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.025 | 0.22 | 0.32 | |||

| OS | 1. NP | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.055 | 0.43 | 0.30 | ||

| 2. NP | 0.17 | 0.43 | 0.074 | 0.57 | 0.70 | |||

| D-pronoun | SO | 1. NP | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.019 | 0.30 | 0.29 | |

| 2. NP | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.045 | 0.70 | 0.71 | |||

| OS | 1. NP | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.030 | 1.00 | 0.75 | ||

| 2. NP | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.25 | |||

Comparison of the experimental results yielded by Experiments 1 and 2 with the results predicted by applying the Bayesian model of Kehler et al. (2008) to the production data yielded by Experiment 3.

7 General discussion

A major aim of this paper was to arrive at an empirically valid characterization of the interpretive preferences of the p-pronoun er and the d-pronoun der. In contrast to prior experiments on German, but in accordance with Kaiser and Trueswell (2008), we closely controlled the topic status of all potential antecedents. Our study went beyond Kaiser and Trueswell’s study by fully disentangling three major factors that have been proposed to govern pronoun resolution – syntactic function, linear position, and topicality.

With regard to the German p-pronoun, our results add further evidence to the generalization in (15), which was reached in the prior literature (see Table 1). We discuss the scope of this generalization below.

Preferred interpretation of a p-pronoun

The preferred antecedent of a p-pronoun is the subject of the preceding clause.

For the d-pronoun, prior research found a consistent preference for the second NP in subject-initial sentences but mixed preferences for subject-final sentences (see Table 1). Experiments 1 and 2 replicated this pattern, but also suggest a reason for the inconsistent preferences for subject-final sentences. In Experiment 1, where the topic occurred clause-initially, the sentence-final subject was the d-pronoun’s preferred antecedent, as in the experiments of Wilson (2009) and Ellert (2013). In Experiment 2, where the topic occurred clause-finally, the sentence-initial object was the preferred antecedent of the d-pronoun, as in the experiments of Bosch and Umbach (2007) and Schumacher et al. (2016). For OS sentences, the generalization that d-pronouns prefer non-topical antecedents thus seems to hold. For SO sentences, however, the preferred antecedent of the d-pronoun is the sentence-final object, even when the object is the topic. Thus, SO sentences with a sentence-final topic contradict the often-made claim that d-pronouns prefer non-topical antecedents.

In sum, none of the three major properties that have been invoked to define prominence – syntactic function, linear position, and topicality – is sufficient to capture the interpretive preferences of the d-pronoun. A valid generalization is possible only when the three properties are considered jointly, as in (16).

Preferred interpretation of a d-pronoun

A d-pronoun prefers the antecedent that is least favored by the structural biases.

In SO sentences, the object is always structurally least favored – because it is an object and occurs clause-finally. It is therefore the preferred antecedent of a d-pronoun, whether it is the topic or not. In OS sentences, in contrast, there is a tie between subject and object as far as syntactic function and linear position are concerned. In this case, topicality decides – the d-pronoun prefers the argument that is the non-topic.

The theoretical question then is how to account for the generalizations yielded by the experimental results. As pointed out in the introduction, two general approaches to pronoun resolution can be distinguished. According to the first approach, p-pronouns refer to the most prominent referent (see Arnold et al.2013 for a recent overview). Under this perspective, the experimental findings contributed by this paper could help to refine the notion of prominence in relation to p- and d-pronouns. Whatever the merits of such a refinement may be, it would not give us a general theory of pronoun resolution, in particular because it would not account for the effects of semantic bias as discussed above. This holds even if thematic roles are taken into account when defining prominence, as proposed by Schumacher et al. (2016), because semantic bias cannot be reduced to thematic roles. For illustration, consider the following variation on example (9) from Schumacher et al. (2016).

| Der | Terrorist | ist | dem | Zuschauer | aufgefallen. |

| the | terrorist-nom | is | the | spectator-dat | noticed |

| ‘The spectator noticed the terrorist.’ | |||||

| Der | hat | nämlich | … |

| he-det | has | for-this-reason | |

| ‘The reason was that he …’ | |||

| Der | hat | deshalb | … |

| he-det | has | therefore | |

| ‘He therefore …’ | |||

Intuitions suggest that the terrorist is the preferred antecedent of the d-pronoun when the continuation sentence gives the reason for the preceding clause whereas the spectator is preferred as antecedent when the continuation sentence gives a consequence of the preceding clause (see Portele and Bader2018, for experimental evidence; see Fukumura and Van Gompel2010, for corresponding data for English p-pronouns). Thus, by merely changing the coherence relation between the two sentences, the preferred antecedent is either the subject/proto-patient of the preceding clause or the object/proto-agent.

Because research on pronoun resolution has revealed effects of both structural and semantic bias, Kehler et al. (2008) proposed a theory of pronoun resolution that accounts for both biases. According to Rohde and Kehler (2014), this theory makes the notion of prominence superfluous. In Experiment 3, we obtained the production data necessary to test whether the Bayesian theory can account for the interpretation preferences of German p- and d-pronouns. As shown in Section 6, there was a good quantitative fit between experimental results and predicted preferences. We therefore conclude that the Bayesian theory generalizes to German – to p-pronouns, for which Rohde and Kehler (2014) already provided a quantitative test in English, and to d-pronouns, for which no relevant data were available so far.

According to the Bayesian theory, interpretation preferences follow from production biases. This implies a shift of focus from language comprehension to language production. That is, we have to ask what causes the production frequencies that form the basis of predicting interpretive preferences. Because the sentences that we tested did not have strong next-mention biases, the term P(pronoun|referent) carries the burden of explaining the observed interpretive preferences. In line with research on English, we found that a p-pronoun is more likely used when referring to the subject than when referring to the object.

A more complicated picture emerged for the d-pronoun. It is at this point where the notion of prominence may be useful after all. As discussed above, the notion of prominence is of limited value for pronoun interpretation because it is not general enough to capture the whole range of factors affecting the choice of an antecedent during language comprehension. With regard to production, the explanatory burden of the notion of prominence is reduced – prominence is only needed to choose a referential expression for a given referent. Why a referent is mentioned in the first place is an independent issue that is captured by the next-mention bias, which subsumes all effects related to sentence meaning and world knowledge. Building on this idea, Portele and Bader (2017) have shown how the probability of using a d-pronoun for a given referent can be predicted by the antecedent’s prominence, with prominence jointly defined in terms of syntactic structure, linear structure, and information structure.

In conclusion, for the p-pronoun the results presented in this paper confirm the subject preference of varying strength found in the prior literature. As for the source of the p-pronoun’s subject preference, the results of Experiment 3 support Kehler et al.’s (2008) hypothesis that expectations derived from language production govern pronoun resolution. In our experimental materials, the two potential referents of the p-pronoun had about the same probability of being mentioned again. However, a p-pronoun was much more likely to be used for referring back to the subject than to the object. From this, a reader may conclude that the subject is the intended antecedent of a referentially ambiguous p-pronoun. For the d-pronoun, our results are at variance with the widely held conviction that d-pronouns prefer non-topical antecedents. This conviction is contradicted by the finding from Experiment 2 that the topic NP is the d-pronoun’s preferred antecedent when the topic occurs sentence-finally in a SO sentence. Thus, the alleged topic preference of the d-pronoun was the result of considering only sentences with the topic in initial position. When taking into account a wider range of structural configurations, no single factor can capture the preferred interpretation of the d-pronoun. As for the p-pronoun, the results of Experiment 3 suggest that the interpretive preferences of the d-pronoun are related to the use of d-pronouns and demonstrative pronouns in language production.

References

Abraham, Werner. 2002. Pronomina im Diskurs: deutsche Personal-und Demonstrativpronomina unter ‘Zentrierungsperspektive’. Grammatische Überlegungen zu einer Teiltheorie der Textkohärenz. Sprachwissenschaft 27(4). 447–491.Search in Google Scholar

Ahrenholz, Bernt. 2007. Verweise mit Demonstrativa im gesprochenen Deutsch: Grammatik, Zweitspracherwerb und Deutsch als Fremdsprache. Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter.10.1515/9783110894127Search in Google Scholar

Arnold, Jennifer E., Elsi Kaiser, Jason M. Kahn & Lucy K. Kim. 2013. Information structure: Linguistic, cognitive, and processing approaches. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science 4(4). 403–413.10.1002/wcs.1234Search in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker & Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). 1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01.Search in Google Scholar

Bosch, Peter, Tom Rozario & Yufan Zhao. 2003. Demonstrative pronouns and personal pronouns. German ‘der’ vs. ‘er’. In Proceedings of the EACL 2003 workshop on the Computational Treatment of Anaphora, Budapest.Search in Google Scholar

Bosch, Peter & Carla Umbach. 2007. Reference determination for demonstrative pronouns. ZAS Papers in Linguistics 48. 39–51.10.21248/zaspil.48.2007.353Search in Google Scholar

Bouma, Gerlof & Holger Hopp. 2007. Coreference preferences for personal pronouns in German. ZAS Papers in Linguistics 48. 53–74.10.21248/zaspil.48.2007.354Search in Google Scholar

Colonna, Saveria, Sarah Schimke & Barbara Hemforth. 2012. Information structure effects on anaphora resolution in German and French: A cross-linguistic study of pronoun resolution. Linguistics 50(5). 991–1013.10.1515/ling-2012-0031Search in Google Scholar

Crawley, Rosalind A. & Rosemary J. Stevenson. 1990. Reference in single sentences and in texts. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 19(3). 191–210.10.1007/BF01077416Search in Google Scholar

Crawley, Rosalind A., Rosemary J. Stevenson & David Kleinman. 1990. The use of heuristic strategies in the interpretation of pronouns. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 19(4). 245–264.10.1007/BF01077259Search in Google Scholar

Dowty, David. 1991. Thematic proto-roles and argument selection. Language 67. 547–619.10.1353/lan.1991.0021Search in Google Scholar

Dudenredaktion (ed.). 1997. Richtiges und gutes Deutsch: Wörterbuch der sprachlichen Zweifelsfälle 9. Mannheim: Dudenverlag.Search in Google Scholar

Ellert, Miriam. 2013. Information structure affects the resolution of the subject pronouns er and der in spoken German discourse. Discours. Revue de linguistique, psycholinguistique et informatique 12(12). 3–24.10.4000/discours.8756Search in Google Scholar

Frey, Werner. 2004. The grammar-pragmatics interface and the German prefield. Sprache und Pragmatik 52. 1–39.Search in Google Scholar

Fukumura, Kumiko & Roger P. G. van Gompel. 2015. Effects of order of mention and grammatical role on anaphor resolution. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 41(2). 501.10.1037/xlm0000041Search in Google Scholar