Abstract

Objectives

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and sepsis are significant global health challenges, both involving complex molecular mechanisms that may overlap. Identifying shared differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between these conditions could provide novel insights into disease progression and therapeutic targets. This study aimed to determine common DEGs between HCC and sepsis using microarray datasets and to explore their biological implications through bioinformatics analyses.

Methods

Publicly available microarray datasets for HCC and sepsis were retrieved from gene expression repositories. After preprocessing and normalization, DEGs were identified using statistical approaches, and overlapping genes were determined through comparative analysis. Functional enrichment analysis was performed with the DAVID platform to assess associated biological processes and pathways. A protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was then constructed to identify hub genes, and transcription factor (TF)–gene interaction analysis was carried out to evaluate potential regulatory mechanisms shared between the two conditions.

Results

A total of 379 common DEGs were identified between HCC and sepsis. Functional enrichment analysis indicated that these DEGs were mainly related to immune response, cell cycle regulation, and antigen presentation pathways. PPI network analysis revealed hub genes including CCNA2, NUSAP1, TOP2A, and CDK1, all of which were significantly upregulated in both diseases. TF–gene interaction analysis highlighted convergent transcriptional regulatory mechanisms linking immune dysregulation in sepsis with tumorigenesis in HCC.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates molecular similarities between HCC and sepsis, emphasizing shared DEGs and regulatory networks. The identification of hub genes and enriched pathways provides potential diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets, underscoring the importance of transcriptional dysregulation in both cancer development and sepsis pathophysiology.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and sepsis are two life-threatening conditions that significantly impact global health, contributing to high rates of illness and death worldwide [1], 2]. HCC, the most common and aggressive form of primary liver cancer, is a leading cause of cancer mortality, particularly in regions where hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) infections are prevalent. The absence of noticeable symptoms in the early stages of HCC often leads to late detection, reducing the availability of curative treatments and resulting in a poor prognosis [3], 4]. Major risk factors for HCC development include chronic viral hepatitis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), excessive alcohol intake, and metabolic disorders such as diabetes and obesity. These conditions drive persistent liver inflammation, fibrosis, and cirrhosis [5], 6]. The transformation from chronic liver disease to HCC is driven by complex molecular and genetic changes, including altered cell cycle regulation, immune evasion mechanisms, and dysregulated inflammatory pathways.

Sepsis, on the other hand, is a severe, life-threatening syndrome characterized by organ dysfunction due to a dysregulated host response to infection [7]. It is a major cause of mortality in critically ill patients and can rapidly progress to septic shock, leading to multiple organ failure and death [8]. The pathophysiology of sepsis involves excessive activation of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory pathways, endothelial dysfunction, and immune system dysregulation, which ultimately contribute to widespread tissue damage and impaired homeostasis [9]. Even while sepsis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have different clinical manifestations, new research indicates that they can have similar molecular processes, especially when it comes to immune control and inflammatory reactions. This suggests that there are biochemical pathways that overlap between the formation of tumours, infection-induced systemic inflammation, and chronic liver disease [10].

Although sepsis is a systemic inflammatory condition and HCC is a tissue-specific malignancy, recent studies have emphasized the interconnectedness of immune dysregulation and chronic inflammation in both diseases. The liver plays a central role in systemic immune responses, and it is both a target and an active modulator of inflammation during sepsis. Moreover, persistent inflammation following sepsis has been associated with long-term immunosuppression and tissue remodeling, which may predispose individuals to tumorigenesis, particularly in the liver. Conversely, chronic liver diseases that predispose to HCC often involve recurrent infections and microbial translocation, both of which can lead to systemic inflammatory responses resembling sepsis. Therefore, despite differences in primary tissue involvement, HCC and sepsis may converge at shared immune-related and inflammatory molecular pathways. Exploring these overlapping mechanisms through comparative transcriptomic analysis can provide valuable insights into immune-mediated pathogenesis and identify common therapeutic targets [10], [11], [12].

In recent years, bioinformatics-based approaches have revolutionized disease research by enabling the large-scale identification of DEGs across various pathological conditions. These DEGs have essential functions in fundamental biological processes such as immune regulation, apoptosis, oxidative stress, and cell proliferation, which are key factors in both cancer progression and the host response to infections [11], 12]. Investigating the shared genetic and molecular alterations between HCC and sepsis could reveal crucial biomarkers and therapeutic targets with translational potential. Previous studies have identified certain immune-related pathways, such as cytokine signalling, antigen presentation, and programmed cell death, as potential intersections between cancer and systemic infections, further supporting the hypothesis of a molecular connection between these two diseases [13], 14].

Given the increasing availability of high-throughput gene expression datasets, the integration of bioinformatics tools has provided a powerful strategy for uncovering novel disease mechanisms. In this study, we aimed to identify common molecular signatures between HCC and sepsis using publicly available microarray datasets. By analysing differentially expressed genes and their associated pathways, we sought to determine key regulatory networks that may underlie both conditions. To achieve this, we constructed a comprehensive protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, performed functional enrichment analyses, and explored transcription factor (TF)-gene interactions to map the shared molecular landscape of HCC and sepsis.

Despite growing recognition of these connections, there is limited integrated transcriptomic analysis directly comparing HCC and sepsis. Therefore, leveraging high-throughput bioinformatics tools to explore their shared molecular signatures could uncover novel insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets.

In this study, we aimed to identify common differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and biological pathways between HCC and sepsis by analyzing publicly available gene expression datasets. By constructing protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, performing gene ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analyses, and mapping transcription factor (TF)-gene interactions, we sought to elucidate converging molecular processes. We hypothesize that identifying these shared regulatory networks will enhance our understanding of immune dysfunction and inflammation across both diseases and support the discovery of novel biomarkers and drug targets.

Materials and methods

Retrieval of datasets

In order to find the related datasets, the publicly accessible Gene Expression Omnibus database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/accessed on 09 August 2024) was searched for HCC or sepsis. Two datasets, GSE28750 for sepsis and GSE45267 for HCC selected for analysis. GSE28750 includes peripheral whole blood samples consisting of 10 sepsis patients and 20 healthy controls. GSE28750 has been used as a validation set for key gene signatures and potential diagnostic biomarkers in different research, previously [15], 16]. Identification of GSE45267 comprises 48 healthy individuals having normal liver tissues and 39 HCC patients with tumor liver tissues. GSE45267 stands out due to its balanced and well-characterized sample set, its rich differential gene expression data. Both experiments were performed by GPL570 [HG-U133_Plus_2] Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Arraya widely used and well-validated microarray platform, ensuring high-quality, comparable gene expression data [17].

Screening of differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

DEGs were identified using GEO2R [18] with a threshold of adjusted p-value (FDR) < 0.05. |log2FC| ≥ 1. The adjusted p-values were calculated using the Benjamini & Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate. Overlapping DEGs between sepsis and HCC were discovered with the Draw Venn Diagram (http://bioinformatics.psb. ugent.be/webtools/Venn/). Overlapped genes used in the downstream analysis.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis and hub genes identification

PPI of shared DEGs was carried out via STRING online data base (https://www.string-db.org/). The PPI network for common DEGs were created with a confidence score≥0.7. Next, the PPI network was viewed using the Cytoscape (www.cytoscape.org/) software [19]. CytoHubba is a plugin used within Cytoscape for identifying key hub genes or nodes in a biological network. We used cytoHubba [20] to identify highly connected or influential nodes within a protein-protein interaction network, which may be critical for understanding disease mechanisms or biological processes. By using Maximal Clique Centrality (MCC) algorithm top 10 hub genes were selected with the highest connectivity since the MCC algorithm effectively captures the most central and functionally important genes in complex biological networks.

Kyoto encyclopaedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathway and gene ontology (GO) functional enrichment analysis

For KEGG and GO analyses overlapped genes between datasets were utilized. The enrichment analysis was achieved by using The Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) version 6.8 (last updated: October 2021) online tool (http://david-d.ncifcrf.gov/). For KEGG and GO analyses, p-value of <0.05 was set as the threshold. Benjamini–Hochberg FDR method was applied for multiple testing correction within DAVID, and only terms with adjusted p<0.05 were considered significant.

Transcription factor (TF)- gene and miRNA-gene interaction prediction

Transcriptional Regulatory Relationships Unravelled by Sentence Based Text Mining (TRRUST) within the NetworkAnalyst, a database for predicting transcriptional regulatory networks, was employed for 10 hub genes to prediction of TF-gene interactions [21]. MiRNA-gene interaction network constructed by miRTarBase (version 8.0; https://mirtarbase.cuhk.edu.cn/) found in the Networkanalyst framework [22].

Results

Identification of shared DEGs in HCC and sepsis

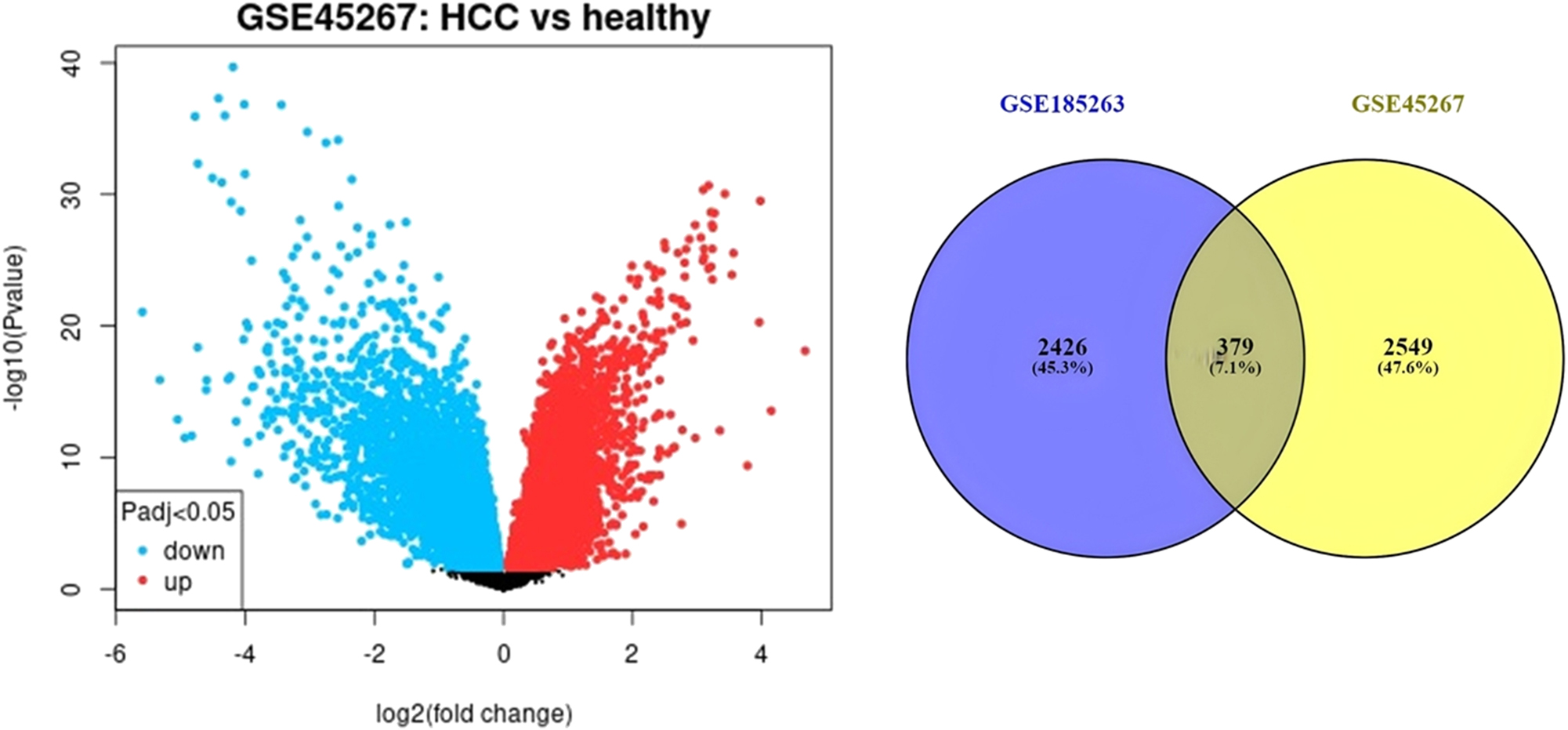

Using the NCBI GSE28750 and GSE45267 microarray datasets, we investigated the DEGs in Sepsis patient’s vs. healthy individuals and HCC patient’s vs. healthy individuals. Volcano plots were used to display the results of the differential analysis. In sepsis dataset we detected 2805 DEGs with 1,368 of them down-regulated and 1,437 up-regulated. The number of total DEGs found in HCC dataset was 2928. In this dataset 1,613 DEGs showed down-regulation whereas 1,315 showed up-regulation. Following, we identified 379 common DEGs between GSE28750 and GSE45267 (Figure 1). The further analysis was conducted upon common DEGs. Among these DEGs 129 of them were commonly up-regulated and the number of commonly down-regulated DEGs was 81. The heatmap demonstrates the expression level of common DEGs (Figure 1). Volcano plots visualize expression changes in both disease states (Figure 1).

Volcano plots of microarray data showing differential gene expression changes in HCC and sepsis. Intersection of DEGs detected in HCC and sepsis. The heatmap was generated based on expression levels of shared DEGs. Red colour indicates higher expression, and blue colour indicates lower expression.

PPI network analysis and identification of hub genes

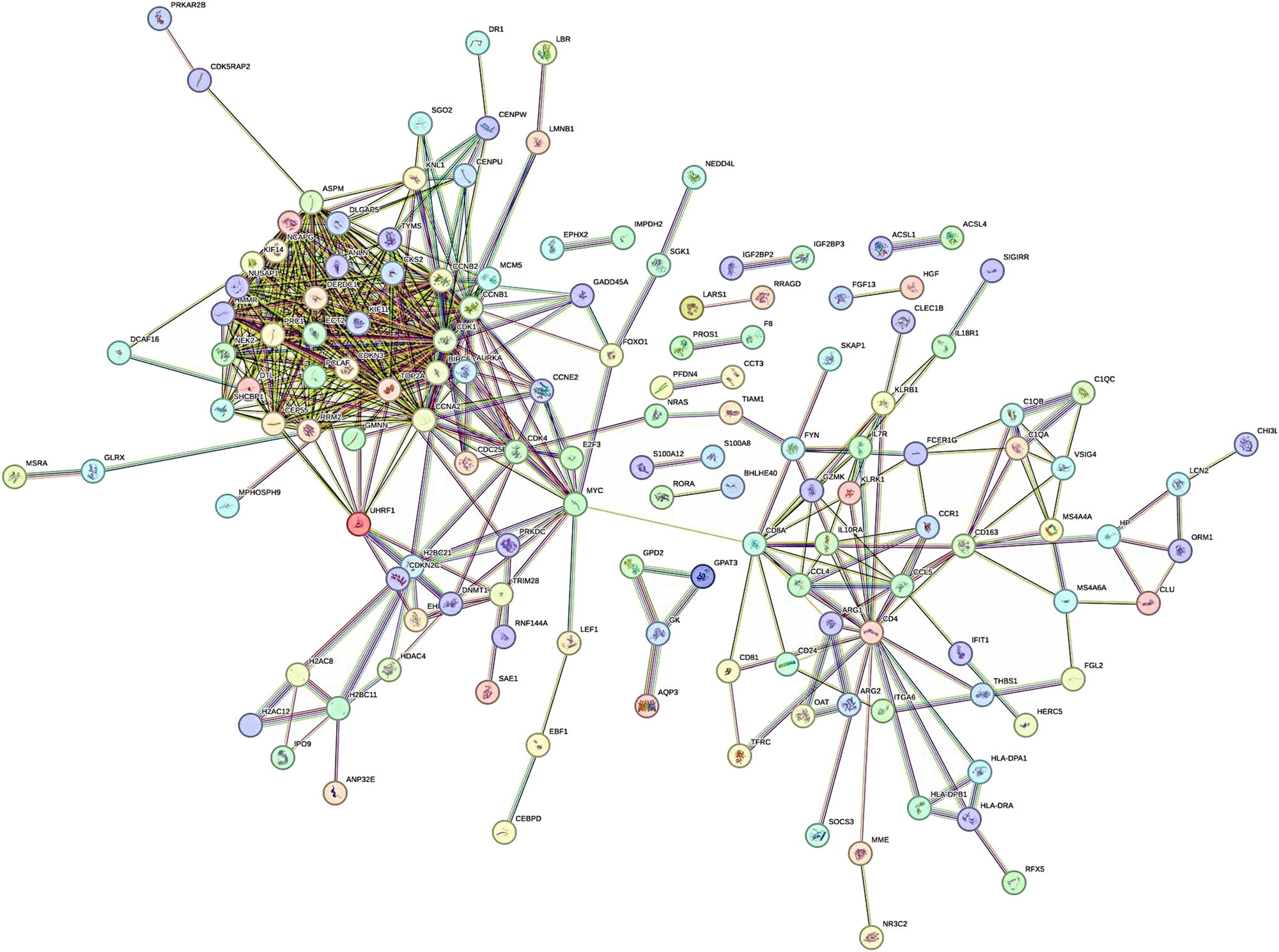

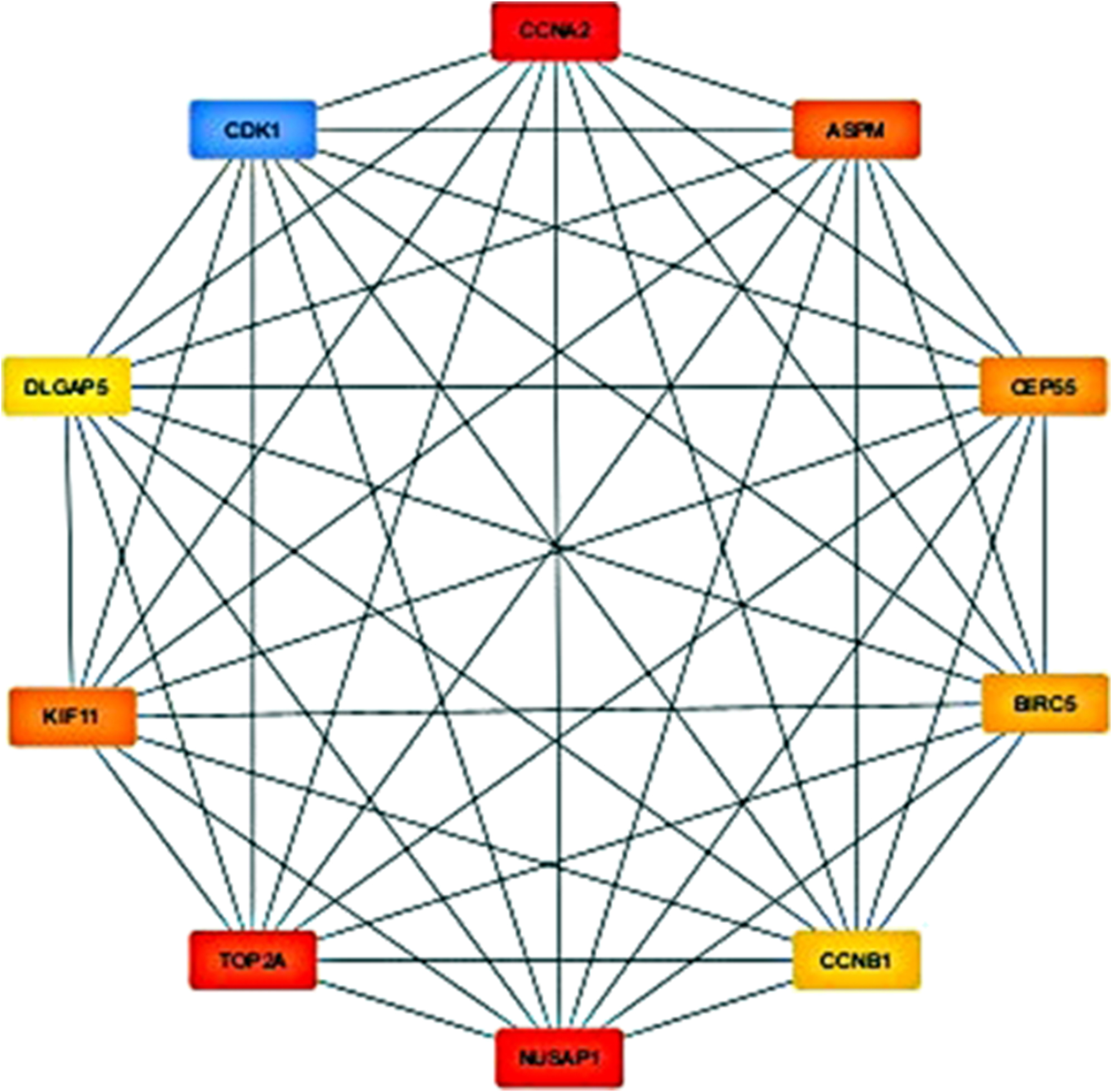

The PPI network of the common DEGs was constructed using STRING (Figure 2), where nodes represent proteins and edges represent predicted interactions. This network included 275 nodes and 687 edges, reflecting the complex interaction landscape of the shared differentially expressed genes. To identify the most critical genes within this network, the dataset was further analyzed using CytoHubba, a plugin in Cytoscape for hub gene identification. The CytoHubba analysis revealed 10 hub genes based on their topological importance: CCNA2, NUSAP1, TOP2A, CDK1, ASPM, KIF11, CEP55, BIRC5, CCNB1, and DLGAP5 (Figure 3). Expression analysis showed that all of these hub genes were upregulated in both HCC and sepsis samples, suggesting a potential shared pathogenic mechanism.

The PPI network of shared DEGs in HCC and sepsis.

The identified top 10 hub genes having maximum number of interactions detected via Cytohubba.

GO and KEGG analysis of overlapped genes

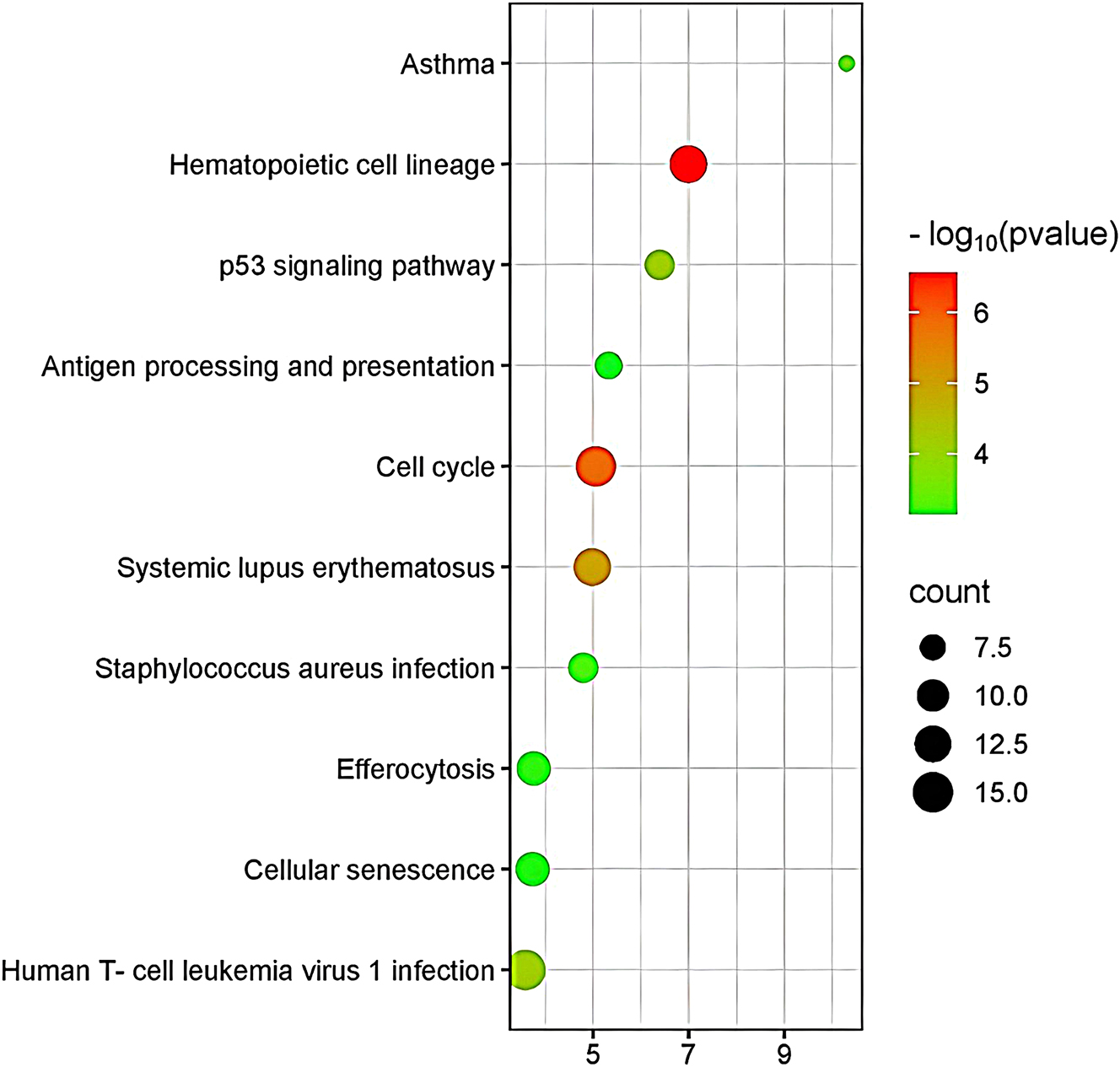

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses were performed using the DAVID online tool for 379 overlapping genes. Results were ranked by statistical significance (p-value), and the top 10 most significantly enriched GO terms and KEGG pathways were visualized in Figures 4 and 5, respectively.

GO analysis of HCC and sepsis shared DEGs (p≤0.05).

Pathway analysis displaying associations with shared DEGs of HCC and sepsis (p≤0.05).

Figure 4 illustrates the GO enrichment analysis results, highlighting key Biological Process terms. In the biological process category, enrichment analysis revealed significant involvement of shared DEGs in cell division (GO:0051301), G2/M and G1/S transitions of the mitotic cell cycle (GO:0000086, GO:0000082), and chromosome segregation (GO:0007059), indicating enhanced proliferative activity in both diseases. Immune-related processes were also enriched, such as antigen processing and presentation (GO:0019882) and peptide antigen assembly with MHC class II protein complex (GO:0002504), highlighting shared immune modulation pathways between HCC and sepsis.

In terms of molecular function, significant enrichment was observed in genes involved in protein binding (GO:0005515), which reflects general molecular interaction capacity. However, more specific and disease-relevant functions were also enriched, such as MHC class II protein complex binding (GO:0023026) and MHC class II receptor activity (GO:0032395), suggesting a potential role for antigen presentation and adaptive immune modulation in both HCC and sepsis. Additionally, enrichment in kinase-related functions – such as cyclin-dependent protein serine/threonine kinase regulator activity and protein kinase binding – indicates alterations in signaling pathways related to cell cycle control and inflammatory signaling cascades.

For cellular components, shared DEGs were enriched in the cytosol (GO:0005829) and cytoplasm (GO:0005737), consistent with intracellular signaling and metabolic processes. Notably, there was significant enrichment in extracellular exosomes (GO:0070062) and clathrin-coated vesicle membranes (GO:0030669), suggesting active intercellular communication and vesicle-mediated antigen transport, which are relevant to both tumor microenvironment remodeling and systemic immune responses during sepsis.

Figure 5 presents the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the shared DEGs revealed significant involvement in immune-related and proliferative pathways. The most significantly enriched pathway was Hematopoietic cell lineage, highlighting disruption in immune cell differentiation and development common to both HCC and sepsis. Other prominently enriched pathways included the p53 signaling pathway, associated with DNA damage response and apoptosis, and the cell cycle, supporting a role for uncontrolled proliferation. Pathways related to immune dysfunction and infection – such as antigen processing and presentation, systemic lupus erythematosus, Staphylococcus aureus infection, and effercytosis – further indicate immune dysregulation as a shared hallmark. Collectively, these results suggest convergence in cell cycle control and immune system perturbation across both disease states.

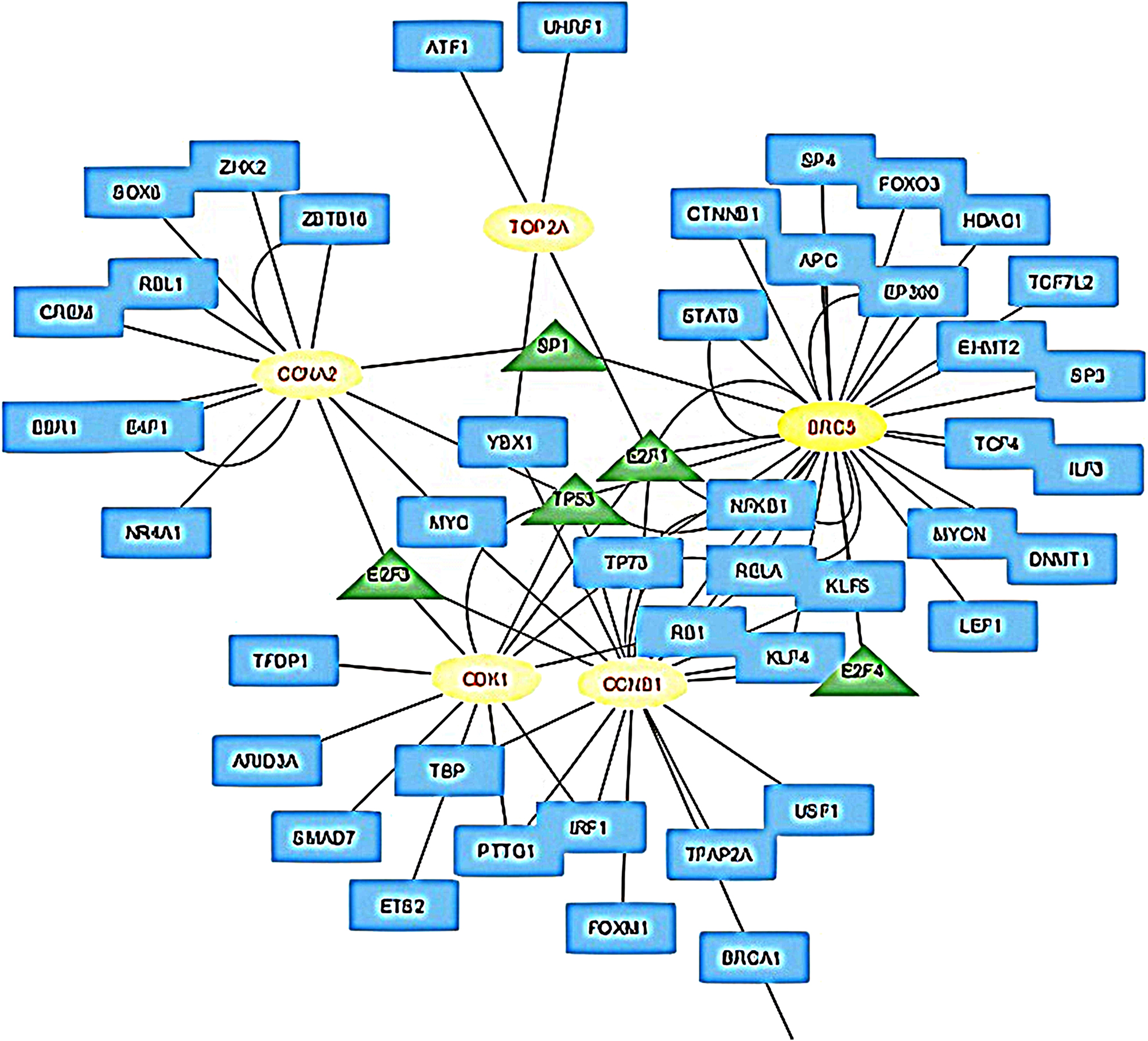

TF–gene ınteraction analysis

To further explore the regulatory mechanisms of the identified hub genes, transcription factors (TFs) targeting these genes were analyzed using the TRRUST database via NetworkAnalyst. The resulting TF-hub gene interaction network was visualized using Cytoscape (Figure 6). This analysis revealed five key transcription factors E2F1, TOP2A, TP53, E2F3, and E2F4suggesting their central roles in modulating the expression of hub genes involved in both HCC and sepsis.

TF-hub gene interaction network visualized via cytoscape. The blue rectangle shows TFs, the yellow ellipses represent hub genes and green triangles represents hub TFs.

miRNA analysis

To identify post-transcriptional regulators of the hub genes, miRNA-hub gene interactions were analyzed using miRTarBase (version 8.0) through the NetworkAnalyst platform. A total of 306 miRNAs targeting the 10 hub genes were identified. These interactions were assessed based on degree centrality to highlight the most influential regulatory miRNAs. The top 10 key miRNAs commonly involved in both sepsis and HCC were identified as: hsa-mir-193b-3p, hsa-let-7b-5p, hsa-mir-24-3p, hsa-mir-16-5p, hsa-mir-195-5p, hsa-mir-497-5p, hsa-mir-6507-5p, hsa-mir-192-5p, hsa-mir-215-5p, hsa-mir-186-5p, and hsa-mir-218-5p. This regulatory network highlights the potential roles of specific miRNAs in modulating hub gene expression in both disease contexts.

Discussion

HCC and sepsis are increasing global health concerns, with projections indicating that more than one million HCC cases are expected annually by 2025. The most common form of liver cancer HCC accounts for 90 % of all cases. The high mortality rate associated with HCC is primarily due to late-stage diagnosis and limited treatment options [23]. Meanwhile, sepsis continues to be a leading cause of death for severely ill individuals, worldwide, characterized by dysregulated host immune responses to infections [24].

Despite being different diseases, sepsis and HCC have some molecular pathways in common that contribute to their pathogenesis. Our bioinformatics analysis revealed significant overlaps in immune response modulation, inflammation, and cell cycle regulation, suggesting shared molecular networks. Although the molecular mechanisms underlying HCC and sepsis are distinct, both diseases may intersect at various biological pathways. Exploring these common pathways can enhance our understanding of the pathogenesis of both conditions and potentially lead to the development of novel therapeutic strategies. Specifically, fundamental biological mechanisms such as immune responses, cell cycle regulation, and inflammatory processes may present promising targets for both HCC and sepsis. Illuminating these intersections could pave the way for more effective treatment approaches in the future.

There may be an indirect link between HCC and sepsis, as both conditions are related to the immune system, infections, and inflammation. A key factor connecting these two conditions is immune system dysregulation, which can increase the risk of infections in HCC patients and contribute to sepsis severity. Individuals with HCC may become more susceptible to infections as their immune system weakens with the progression of the disease, increasing their risk of sepsis. Moreover, sepsis itself can cause liver damage, impairing liver function and potentially increasing the risk of HCC development. Additionally, bacterial translocation in cirrhotic patients has been associated with increased tumorigenesis risk, further linking these two conditions at the molecular level. So, while there is no direct cause-and-effect relationship, there may be an indirect connection between sepsis and HCC due to the roles of inflammation, immune system dysfunction, and infection. [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31].

In our study the relationship between sepsis and HCC-related genes was investigated using the GSE28750 and GSE45267 microarray datasets. Here, we identified the genes that are affected in common or different ways in sepsis and HCC by comparing gene expression profiles obtained from sepsis and HCC patients and healthy individuals. Our findings revealed that approximately 13 % of the genes differentially expressed in sepsis and HCC were common, supporting the hypothesis that shared molecular mechanisms exist between these diseases. A PPI network of the common DEGs was created via STRING, and 10 hub genes (CCNA2, NUSAP1, TOP2A, CDK1, ASPM, KIF11, CEP55, BIRC5, CCNB1, DLGAP5) were identified using Cytohubba. GO and KEGG enrichment analyses showed significant enrichment in biological processes such as cell division, G2/M transition, and antigen presentation. TF-gene interaction analysis identified five key TFs: E2F1, TOP2A, TP53, E2F3, and E2F4. In their study to identify hub genes and potential therapeutic drugs for HCC, Su et al. identified the genes TOP2A, CCNA2, CDK1, and CCNB1 [32]. In our study, these genes have also been detected.

Interestingly, gene ontology enrichment revealed a significant overrepresentation of MHC class II–related pathways in the liver-derived HCC dataset. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution. Hepatocytes, the main parenchymal cells of the liver, do not typically express MHC class II molecules under physiological conditions [33].Therefore, the observed enrichment likely reflects the presence of non-parenchymal immune cells – particularly infiltrating macrophages, dendritic cells, or B cells – within the tumor microenvironment, rather than intrinsic expression by hepatocytes or tumor cells [33]. Since our analysis was based on bulk RNA expression data, we could not directly quantify or adjust for cell type composition. Without immune deconvolution or single-cell resolution, such enrichment patterns may confound tissue-specific interpretations and overestimate the role of certain pathways in hepatocyte biology.

E2F1 and TP53 are two critical TFs that play pivotal roles in cancer biology and immune system regulation. They often interact in complex ways to influence tumor progression and immune responses. E2F1 is usually overexpressed in HCC and is related with poor prognosis. It regulates genes that control cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and DNA repair, encouraging tumour growth and metastasis. Beyond its role in tumour cell proliferation, E2F1 influences the tumour immunological microenvironment. Elevated E2F1 levels correlate with increased infiltration of immunosuppressive Th2 cells and suppression of antitumor Th1 responses, leading to immune evasion. Silencing E2F1 can reverse this impact by promoting a Th2-to-Th1 transition and increasing anticancer immunity [34], 35]. TP53, a crucial tumor suppressor gene, is the most commonly mutated gene in human cancers, including HCC [36]. In TP53 wild-type HCC cells, E2F1 can bind to the p53 protein, influencing the expression of immune checkpoint molecules like PD-L1 [35]. Both E2F1 and TP53 play critical roles in HCC progression and regulation of the tumor immune microenvironment. Their interactions affect immune cell behavior and tumor-immune crosstalk, making them potential targets for therapeutic interventions aimed at enhancing antitumor immunity in HCC.

The DNA topoisomerase II alpha (TOP2A) gene encodes an enzyme that regulates the topological state of DNA during essential cellular processes such as transcription and replication. This gene has a significant function in important biological mechanisms, including chromatid separation, alleviation of torsional stress during transcription and replication and chromosome condensation [37]. Given the regulatory importance of these hub genes, they could serve as potential biomarkers for disease progression and treatment response. In research on acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), the TOP2A gene was identified as one of the 20 hub genes in a PPI network. Other notable hub genes include Cyclin B1 (CCNB1), Cyclin B2 (CCNB2), and transcription factors such as FOXM1. These genes are considered potential candidates for innovative gene therapies that may be used in the treatment of sepsis-related ARDS. Studies comparing sepsis and healthy paediatric populations have shown that the TOP2A gene is significantly expressed in infected sepsis groups, suggesting that it could serve as a biomarker for distinguishing sepsis in children from healthy controls. Its involvement in cellular stress mechanisms during infection indicates that TOP2A could be a valuable target for therapeutic interventions [38]. In our study, TOP2A also appears among the common hub genes found for both HCC and sepsis, further supporting its relevance. Wu et al. identified 118 DEGs between very early-stage HCC and cirrhotic tissue samples in their study. These genes were found to have a strong association with important biological processes, such as negative regulation of growth and the p53 signalling pathway. The PPI network analysis results indicated eight hub genes, including CDK1, CCNB1, TOP2A, and CCNA2. In our study, we identified 379 DEGs between HCC and sepsis, and our PPI network analysis identified 10 hub genes, including CDK1, CCNA2, CCNB1 and TOP2A. Extensive investigations of these hub genes have been conducted in previous studies [37], [39], [40], [41], [42].

Up to the present, numerous studies have reported various single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with the development of HCC. These SNPs are linked to genes involved in several critical biological processes. For instance, some SNPs are associated with inflammatory pathways, including genes such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10, and TGF-β. Others relate to iron metabolism, particularly the HFE1 gene. Additionally, SNPs have been found in genes related to oxidative stress pathways, such as GSTM1, SOD2, and MPO, as well as in DNA repair mechanisms involving MTHFR, TP53, and MDM2. Emerging evidence suggests that these SNPs may also influence sepsis susceptibility and progression, as inflammatory and oxidative stress-related pathways are crucial in both diseases. Collectively, these genetic variations play a significant role in influencing the risk of developing HCC by affecting key biological processes. Further investigations into these shared polymorphisms could provide insights into common genetic predispositions and potential biomarkers for early detection or risk assessment in both conditions [43], [44], [45].

306 miRNAs were found to interact with the hub genes, with hsa-mir-193 b-3p and hsa-let-7b-5p emerging as key miRNAs. hsa-mir-193 b-3p acts as a tumor suppressor in HCC by targeting CDK1 and inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and migration but its role in sepsis is not well established [46]. On the other hand, hsa-let-7b-5p has a protective, anti-inflammatory role in sepsis by modulating neutrophil function and TLR4/NF-κB signaling but its involvement in HCC remains to be clarified [47]. Both miRNAs represent promising molecular targets, yet further studies are needed to fully elucidate their roles across these diseases and to overcome translational limitations. Hence, both in vivo and in vitro experiments need to be done.

One important limitation of this study is the use of transcriptomic data derived from different tissues: peripheral blood for sepsis and liver tissue for HCC. This introduces a potential confounding factor due to the heterogeneous cellular composition and baseline expression profiles inherent to each tissue. Nevertheless, we aimed to uncover overarching immune and inflammatory gene signatures that might converge between a systemic inflammatory disease (sepsis) and an inflammation-driven cancer (HCC). Our results should thus be interpreted as hypothesis-generating and not as conclusive evidence of shared mechanisms without further tissue-matched validation. Second, the sample sizes in both datasets were relatively small, limiting statistical power and potentially affecting the robustness of differential expression and enrichment results. Third, although normalization and background correction were performed using the GEO2R platform, no explicit batch effect correction was applied, so it may have influenced the outcome. Finally, the retrospective nature of the data restricts the ability to control for confounding variables or perform systematic validation. Future studies incorporating larger, tissue-matched cohorts and standardized preprocessing pipelines are required to confirm and extend these findings.

In conclusion, our study highlights the molecular intersections between HCC and sepsis, revealing shared pathways related to immune response, cell cycle regulation, and inflammation. The identification of common hub genes, transcription factors, and miRNAs suggests potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for both diseases. Further research into these molecular mechanisms may contribute to the development of novel diagnostic and treatment strategies, ultimately improving patient outcomes in HCC and sepsis.

-

Research ethics: This study involved only publicly available datasets and computational analyses. No human participants or animals were used, and therefore ethical approval was not required.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission. The authors declare that their contributions are equal.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Esposito, S, De Simone, G, Boccia, G, De Caro, F, Pagliano, P. Sepsis and septic shock: new definitions, new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2017;10:204–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2017.06.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Ascione, A, Fontanella, L, Imparato, M, Rinaldi, L, De Luca, M. Mortality from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in Western Europe over the last 40 years. Liver Int 2017;37:1193–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.13371.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Bray, F, Ferlay, J, Soerjomataram, I, Siegel, RL, Torre, LA, Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Bruix, J, Gores, GJ, Mazzaferro, V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical frontiers and perspectives. Gut 2014;63:844–55. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306627.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Rosok, Ø, Sioud, M. Discovery of differentially expressed genes: technical considerations. Methods Mol Biol 2007;360:115–29. https://doi.org/10.1385/1-59745-165-7:115.10.1385/1-59745-165-7:115Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. McDermaid, A, Monier, B, Zhao, J, Liu, B, Ma, Q. Interpretation of differential gene expression results of RNA-seq data: review and integration. Briefings Bioinf 2019;20:2044–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bby067.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Dai, K, Liu, C, Guan, G, Cai, J, Wu, L. Identification of immune infiltration-related genes as prognostic indicators for hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2022;22:496. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09587-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Liu, Z, Qiu, E, Yang, B, Zeng, Y. Uncovering hub genes in sepsis through bioinformatics analysis. Medicine (Baltim) 2023;102:e36237. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000036237.Search in Google Scholar

9. Pessino, G, Scotti, C, Maggi, M, Immuno-HUB consortium. hepatocellular carcinoma: old and emerging therapeutic targets. Cancers (Basel) 2024;16:901. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16050901.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Chu, X, Wu, Q, Kong, L, Peng, Q, Shen, J. Multiomics analysis identifies prognostic signatures for sepsis-associated hepatocellular carcinoma in emergency medicine. Emerg Med Int 2024;2024:1999820. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/1999820.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Refolo, MG, Messa, C, Guerra, V, Carr, BI, D’Alessandro, R. Inflammatory mechanisms of HCC development. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:641. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12030641.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Zhao, H, Wu, L, Yan, G, Chen, Y, Zhou, M, Wu, Y, et al.. Inflammation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther 2021;6:263. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00658-5.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Ho, DWH, Lo, RCL, Chan, LK, Ng, IOL. Molecular pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer 2016;5:290–302. https://doi.org/10.1159/000449340.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Ewald, JD, Zhou, G, Lu, Y, Kolic, J, Ellis, C, Johnson, JD, et al.. Web-based multi-omics integration using the Analyst software suite. Nat Protoc 2024;19:1467–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-023-00950-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Lin, G, Li, N, Liu, J, Sun, J, Zhang, H, Gui, M, et al.. Identification of key genes as potential diagnostic biomarkers in sepsis by bioinformatics analysis. PeerJ 2024;12:e17542. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.17542.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

16. Li, J, Pu, S, Shu, L, Guo, M, He, Z. Identification of diagnostic candidate genes in COVID-19 patients with sepsis. Immun Inflamm Dis 2024;12:e70033. https://doi.org/10.1002/iid3.70033.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Di, C, Du, Y, Zhang, R, Zhang, L, Wang, S. Identification of autophagy-related genes and immune cell infiltration characteristics in sepsis via bioinformatic analysis. J Thorac Dis 2023;15:1770–83. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-23-312.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

18. Gentleman, RC, Carey, VJ, Bates, DM, Bolstad, B, Dettling, M, Dudoit, S, et al.. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol 2004;5:R80. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

19. Xia, J, Gill, EE, Hancock, RE. NetworkAnalyst for statistical, visual and network-based meta-analysis of gene expression data. Nat Protoc 2015;10:823–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2015.052.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Chin, CH, Chen, SH, Wu, HH, Ho, CW, Ko, MT, Lin, CY. cytoHubba: identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst Biol 2014;8:S11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-0509-8-s4-s11.Search in Google Scholar

21. Han, H, Cho, JW, Lee, S, Yun, A, Kim, H, Bae, D, et al.. TRRUST v2: an expanded reference database of human and mouse transcriptional regulatory interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46:D380–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx1013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

22. Cui, S, Yu, S, Huang, HY, Lin, YCD, Huang, Y, Zhang, B, et al.. miRTarBase 2025: updates to the collection of experimentally validated microRNA–target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 2025;53:D147–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae1072.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Llovet, JM, Kelley, RK, Villanueva, A, Singal, AG, Pikarsky, E, Roayaie, S, et al.. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021;7:6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Zhang, X, Zhang, Y, Yuan, S, Zhang, J. The potential immunological mechanisms of sepsis. Front Immunol 2024;15:1434688. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1434688.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Ringelhan, M, Pfister, D, O’Connor, T, Pikarsky, E, Heikenwalder, M. The immunology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Immunol 2018;19:222–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-018-0044-z.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Toffanin, S, Cornella, H, Harrington, A, Llovet, JM, Groszmann, RJ, Iwakiri, Y, et al.. HCC is promoted by bacterial translocation and TLR-4 signaling: a new paradigm for chemoprevention and management. Hepatology 2012;56:1998–2000. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26080.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Conti, F, Dall’Agata, M, Gramenzi, A, Biselli, M. Biomarkers for the early diagnosis of bacterial infection and the surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis. Biomarkers Med 2015;9:1343–51. https://doi.org/10.2217/bmm.15.100.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Brown, ZJ, Heinrich, B, Greten, TF. Mouse models of hepatocellular carcinoma: an overview and highlights for immunotherapy research. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;15:536–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-018-0033-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Hotchkiss, RS, Moldawer, LL. Parallels between cancer and infectious disease. N Engl J Med 2014;371:380–3. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmcibr1404664.Search in Google Scholar

30. Venet, F, Monneret, G. Advances in the understanding and treatment of sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Nat Rev Nephrol 2018;14:121–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2017.165.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

31. Greten, TF, Grivennikov, SI. Inflammation and cancer: triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity 2019;51:27–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

32. Su, Q, Li, W, Zhang, X, Wu, R, Zheng, K, Zhou, T, et al.. Integrated bioinformatics analysis for the screening of hub genes and therapeutic drugs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2023;24:1035–48. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389201023666220628113452.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Herkel, J, Jagemann, B, Wiegard, C, Lazaro, JFG, Lueth, S, Kanzler, S, et al.. MHC class II-expressing hepatocytes function as antigen-presenting cells and activate specific CD4 T lymphocytes. Hepatology 2003;37:1079–85. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2003.50191.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Dong, M, Chen, J, Deng, Y, Zhang, D, Dong, L, Sun, D. H2AFZ is a prognostic biomarker correlated to TP53 mutation and immune infiltration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol 2021;11:701736. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.701736.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

35. Tan, Z, Chen, M, Peng, F, Yang, P, Peng, Z, Zhang, Z, et al.. E2F1 as a potential prognostic and therapeutic biomarker by affecting tumor development and immune microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Cancer Res 2022;11:2713–25. https://doi.org/10.21037/tcr-22-218.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Chen, X, Zhang, T, Su, W, Dou, Z, Zhao, D, Jin, X, et al.. Mutant p53 in cancer: from molecular mechanism to therapeutic modulation. Cell Death Dis 2022;13:974. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-05408-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Yang, J, Zhang, P, Wang, L. Gene network for identifying the entropy changes of different modules in pediatric sepsis. Cell Physiol Biochem 2016;40:1153–62. https://doi.org/10.1159/000453169.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. Wang, M, Yan, J, He, X, Zhong, Q, Zhan, C, Li, S. Candidate genes and pathogenesis investigation for sepsis-related acute respiratory distress syndrome based on gene expression profile. Biol Res 2016;49:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40659-016-0085-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Wu, M, Liu, Z, Li, X, Zhang, A, Lin, D. Analysis of potential key genes in very early hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol 2019;17:77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-019-1616-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

40. Xing, C, Xie, H, Lin, Z, Zhou, W, Wu, Z, Ding, S, et al.. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 3 is overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinoma and promotes tumor cell proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012;420:29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.02.107.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Deng, M, Wang, J, Chen, Y, Zhang, L, Xie, G, Liu, Q, et al.. Silencing cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 3 inhibits the migration of breast cancer cell lines. Mol Med Rep 2016;14:1523–30. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2016.5401.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Yu, C, Cao, H, He, X, Sun, P, Feng, Y, Chen, L, et al.. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 3 plays a critical role in prostate cancer via regulating cell cycle and DNA replication signaling. Biomed Pharmacother 2017;96:1109–16.10.1016/j.biopha.2017.11.112Search in Google Scholar PubMed

43. Luo, X, He, X, Zhang, X, Zhao, X, Zhang, Y, Shi, Y, et al.. Hepatocellular carcinoma: signaling pathways, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. MedComm 2024;5:e474. https://doi.org/10.1002/mco2.474.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

44. Duan, J, Huang, Z, Qin, S, Li, B, Zhang, Z, Liu, R, et al.. Oxidative stress induces extracellular vesicle release by upregulation of HEXB to facilitate tumour growth in experimental hepatocellular carcinoma. J Extracell Vesicles 2024;13:e12468. https://doi.org/10.1002/jev2.12468.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

45. Wang, Y, Deng, B. Hepatocellular carcinoma: molecular mechanism, targeted therapy, and biomarkers. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2023;42:629–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-023-10084-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Pang, X, Wan, W, Wu, X, Shen, Y. The novel action of miR-193b-3p/CDK1 signaling in HCC proliferation and migration: a study based on bioinformatic analysis and experimental investigation. Int J Genomics 2022;2022:8755263. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8755263.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Chen, B, Han, J, Chen, S, Xie, R, Yang, J, Zhou, T, et al.. MicroLet-7b regulates neutrophil function and dampens neutrophilic inflammation by suppressing the canonical TLR4/NF-κB pathway. Front Immunol 2021;12:653344. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.653344.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.