UDM (Unified Data Model) for chemical reactions – past, present and future

-

Jarosław Tomczak

, Markus Fischer

, Gabrielle Whittick

Abstract

The UDM (Unified Data Model) is an open, extendable and freely available data format for the exchange of experimental information about compound synthesis and testing. The UDM had been initially developed in a collaborative project between Elsevier and Roche, where chemical reactions data from a variety of disparate data sources existing at Roche was consolidated and integrated into the Roche in-house version of the Reaxys database. Elsevier adapted the UDM model to its needs and finally donated its pre-4.0 release to the Pistoia Alliance for further development together with the five project founders (Elsevier, Roche, BIOVIA, GSK and Novartis, joined later by BMS), who contributed with funding and expertise to the Pistoia Alliance UDM project between 2017 and 2020. The latest UDM version 6.0 has been made freely available for the community under the MIT license in January 2021. The past, present, and future of the UDM exchange format are discussed in this article and factors that contribute to the successful adoption of the UDM format.

Introduction

What is the problem?

A chemical reaction is defined as a process that transforms reactants into products. The products’ compositions differ from the reactants’ compositions. Several factors influence how reactions proceed, e.g., concentrations of reactants, temperature, pressure, catalysts, reagents, light and heat. In addition, the outcome of a reaction such as product, yield, purity, specificity and more recently environmentally friendly parameters define the reaction too.

Chemical reactions have been published for over 140 years starting with the canonical work by Friedrich Konrad Beilstein [1], although some researchers would go even further back to 1830, the year of the first issue of Pharmaceutisches Centralblatt which eventually became Chemisches Zentralblatt in 1856. In computer databases, chemical reactions have been captured for nearly 40 years [2, 3]. In the last two decades, both commercial organizations and academia have widely adopted electronic laboratory notebooks (ELNs) to help scientists to digitize their chemical syntheses. In the last years, there has been renewed interest in various aspects of reaction cheminformatics, in particular, in retrosynthesis, reaction similarity, synthetic feasibility, reaction prediction and reaction optimization.

Many of them rely on an availability of machine-readable representation of chemical reaction, reaction conditions and reaction outcome which can be stored, searched/retrieved and analyzed computationally.

Moreover, due to the maturity of AI/ML methods, increased computing power, availability of large datasets as well as a realization that AI/ML assisted methods can drastically save time and money for new drug development, the questions are no longer how to represent, store and search chemical reactions but rather how to integrate existing reactions datasets in various public and proprietary databases including ELNs to be able to create a large enough and diverse dataset to train a myriad of emerging synthesis predictive models.

Although there are various ways to store chemical reaction information (discussed later), there is no common way to represent chemical reaction, including their conditions and outcomes comprehensively. Despite many file formats used to store chemical reaction information with various limitations, none has been widely adopted as a standard approach that allows high-quality capture, validation, and exchange of such data. Even graphical representation standards for chemical reaction diagrams by the IUPAC are still a draft form [4].

All the above hamper integration, comparison and analysis of reaction data from various sources as well as comprehensive search and analysis for competitive intelligence and IP capture. This makes collaboration and data exchange between organizations using different ELNs unnecessarily difficult and expensive. Furthermore, the lack of a common data model makes it arduous to develop and share business rules for consistent representation of reactions and their IP capture. Anecdotal experience suggests that ELNs have less strict and enforceable chemistry rules for chemical reactions and, in particular, for their stereochemistry compared to compound registration systems.

Subsequent sections will introduce the Unified Data Model, present the history of its development, provide a high-level overview of how it is used to store reaction data, compare it to other formats and discuss its future.

UDM overview

UDM addresses a critical gap in the FAIRification of chemical synthesis data – the lack of their comprehensive and standardized digital representation. UDM provides a hierarchical model and controlled vocabularies to describe chemical reactions on the one hand and a well-defined file format to represent them on the other.

The Unified Data Model covers compounds and their properties, reaction conditions, preparations and outcomes, analytical data, literature references, and legal and licensing information. UDM files are defined by applying a pragmatic approach for data storage and relying on a proven, standard technology—XML. The entire data model, data types, value constraints and units of measure are implemented using an XML Schema [5]. It allows the use of widely available, generic XML tools for validating, querying and transforming UDM documents.

UDM files can use different representations of molecular structures, reaction diagrams and textual descriptions of reaction recipes. To reduce the cost of long-term adoptions, the file format aims to be stable (fewer major releases rather than a more continuous approach) and allow flexibility and openness to store additional data not foreseen by the UDM team or too specific for individual applications. Such scenarios are supported by several extension points built into the UDM. In the most basic case, they allow storing vendor- or process-specific data, which are only required to be well formatted XML document sections. In a more advanced case, derived, backwards-compatible versions of UDM can be created by extending the original UDM XML schema and validating the data stored in the extension points. The original Pistoia Alliance license was explicitly designed to reflect this model. The current MIT license offers even more flexibility.

How did UDM come about?

Reaxys® [6, 7] is a commercially available chemical information system originally consisting of the Gmelin and Beilstein handbooks which recorded systematically organized chemical data starting from the 19th century. Up to date, Reaxys continuously adds chemical information from peer-reviewed journals, patents and conference abstracts using manual and automatic content processing pipelines. Its organization of chemical information in the Reaxys databases is based on three pillars: citations, substances and reactions.

Reaxys and Roche understood that integrating the reaction data of the publicly available Reaxys information with all inhouse available data sources would improve productivity and save time for researchers as they would be able to launch a single search across multiple data systems and find information across them, including the related information, for example, via citations.

Therefore in 2012, Roche started the development of the Unified Data Model (UDM). Its goal was the integration of the different data formats from their various internal and externally licensed databases together with the reaction data from their ELNs into one common data model (UDM) to let this data be joined with the reaction data provided within Reaxys.

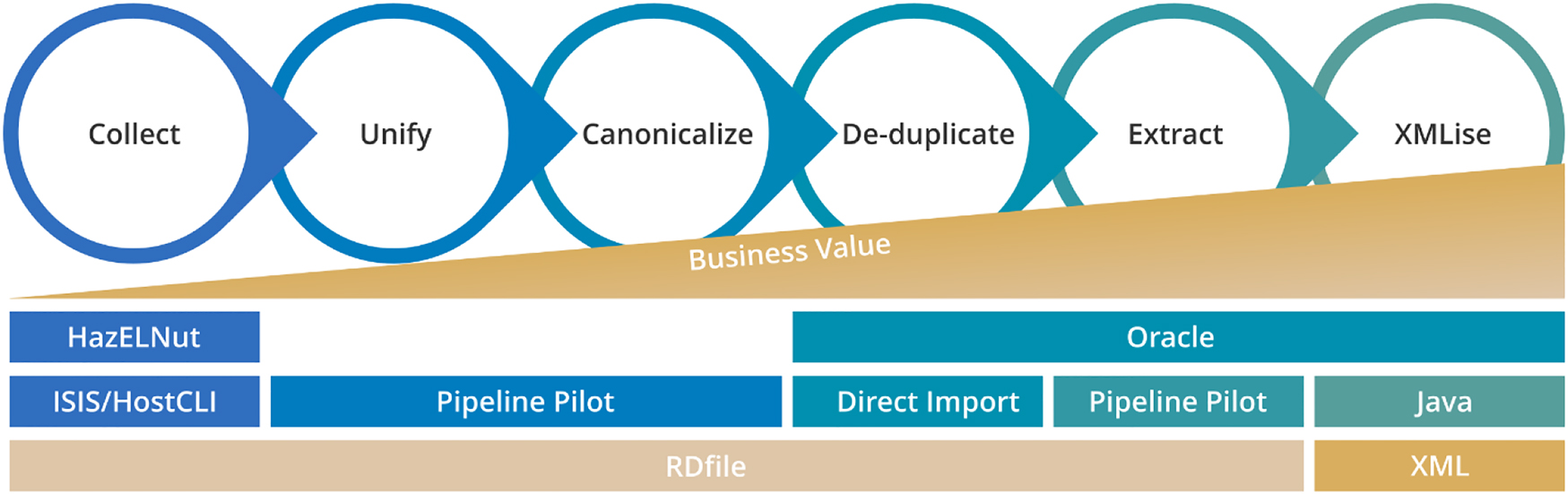

The overall data reaction migration consisted of five major steps: Collect, Unify, Canonicalize, De-duplicate and Extract (Fig. 1). Reactions were collected and unified into the single common UDM format. Using canonicalization, the reactions were de-duplicated so that frequently occurring reactions were represented by the same reaction scheme. The data was processed, and the essential information was extracted and migrated into Reaxys. The Reaxys User Interface (UI) was used for the simultaneous searches in both data sources [7, 8].

Reaction migration steps utilizing UDM.

The first UDM version was implemented based on the RD file format. In UDM RDfiles all molecular structures and their data were explicitly added to each reaction section where it belonged to. This lead to redundant and potentially inconsistent representation of identical molecules and citations from time to time. To remove these redundancies the UDM was further developed into an XML format where molecules and citations were de-duplicated, stored in a separate data block within the UDM file and referenced in the related reaction sections by the “XMLise” step. The adaption of these modifications and necessary extension by Reaxys for their upload process eventually constituted the UDM 1.0 version.

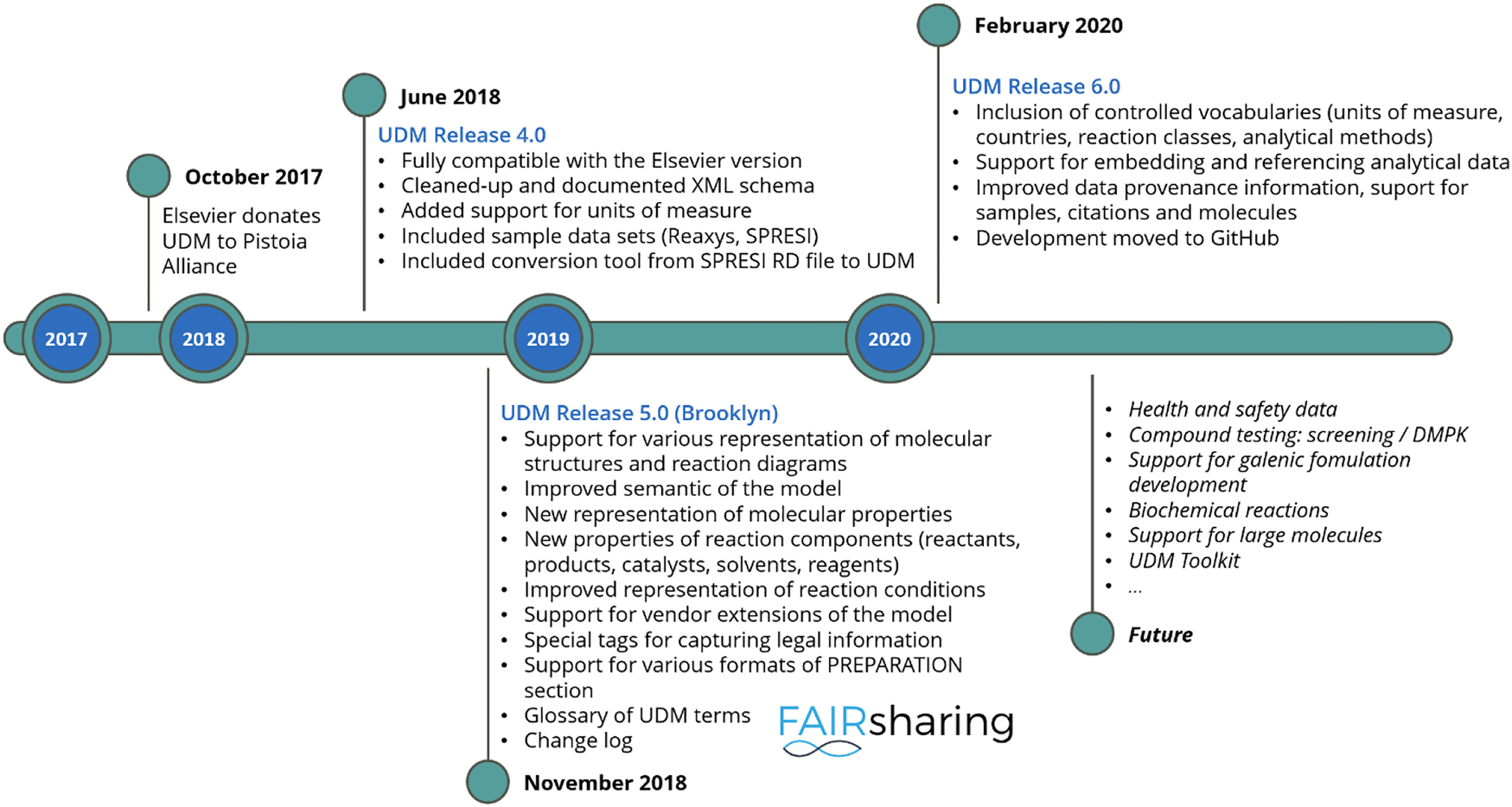

In the following few years, Elsevier has further developed the UDM schema with the help of other integration customers. The UDM was extended to cover additional properties that are more linked to molecules that come with a reaction. In October 2017, the latest Reaxys UDM version (UDM 3.6) was provided to the Pistoia Alliance to make it more generic and to let it be extended to other experiment types.

Subsequent developments and releases of UDM within the “Pistoia Alliance UDM” project were driven by the project founders (Elsevier, Roche, BIOVIA, GSK, Novartis, and BMS) and the UDM team members (see Table 1) under the governance by Pistoia Alliance.

UDM team members at Pistoia Alliance.

| AstraZeneca | Dotmatics | NextMove Software |

| BIOVIA | Elsevier | Novartis |

| BMS | GSK | PerkinElmer |

| Bayer | IDBS | Pistoia Alliance |

| Binocular Vision | InfoChem | Roche |

| CAS | Informatics Unlimited | StructurePendium |

| ChemAxon | KIT | … |

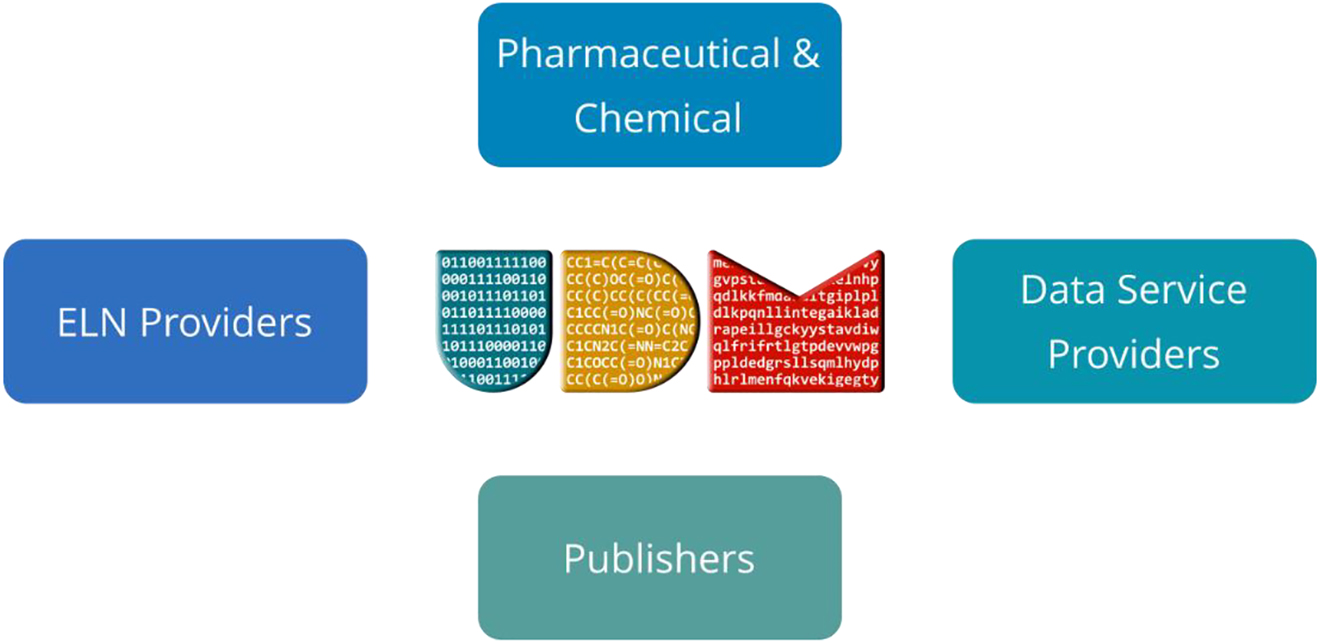

The UDM development team expanded and included other stakeholders such as pharma, chemical, and cheminformatics companies, as well as ELN providers as illustrated in Fig. 2.

UDM stakeholders.

During the Pistoia Alliance governance, the UDM team met online on a regular basis to discuss requirements, new developments, extensions to the format and new releases. There were also dedicated sessions during European and US Pistoia Alliance meetings, as well as a dedicated workshop in Amsterdam sponsored by Elsevier in 2019 where publisher and ELN provides met to exchange their experiences about reaction handling.

Developing successive versions of the Unified Data Model was guided by the requirements for new features gathered by the project team members without removing existing features already extensively used by some organizations. The result was that some of them were preserved for backward compatibility even though a better, more generic approach was identified and implemented. A good example is the handling of molecular properties. The pre-4.0 UDM version had dedicated XML entities to store values such as cLogP, the number of hydrogen bond donors or acceptors, the PSA (polar surface area) and so on. In UDM version 5, a concept of a generic molecular PROPERTY was introduced (with additional fields describing how it was obtained). It could be used to store the properties mentioned above. However, some stakeholders heavily rely on the original property entities, and therefore they are still present. In future UDM releases, such elements may be marked as deprecated or obsolete.

Fig. 3 illustrates vital milestones in the development of the UDM format under the umbrella of the Pistoia Alliance.

UDM development milestones as Pistoia Alliance project.

From the beginning of the Pistoia Alliance UDM project, the team was well aware of the critical importance and challenges of adopting the UDM. The group involved representatives from key informatics suppliers and their customers actively contributing to the specification and many of them declared future support for the format. For example, BIOVIA has implemented the UDM file format released in December 2020 in the Pipeline Pilot 2021 version. Considering the flexible nature of the product and its widespread adoption, it provides the ability to process UDM files to a large number of life-science organisations. To our knowledge, no other commercial ELN provider has adopted the UDM exchange format; however, the Chemotion ELN, a free ELN developed by Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) for the NFDI4Chem initiative, has incuded the UDM implementation on its development roadmap [9]. The support from other ELN providers for their adoption of the UDM exchange format is ongoing and will be essential for the successful adoption of the format.

The entry barrier to implementing the UDM is lowered by the fact that it is an XML-based file format with a well-defined schema, and one can use existing XML libraries and tools to convert, process, and query UDM files. This approach has been used by several organisations which adopted the UDM to ingest reaction data into Elsevier Reaxys. Furthermore, a sample Python code is included in the UDM distribution (and could be found on the UDM GitHub site), implementing the conversion of SPRESI RD files to UDM. The UDM team has also prepared a proposal for a toolkit facilitating various aspects of processing and curation of reactions in the UDM format and is looking for external funding to deliver it.

Unified Data Model

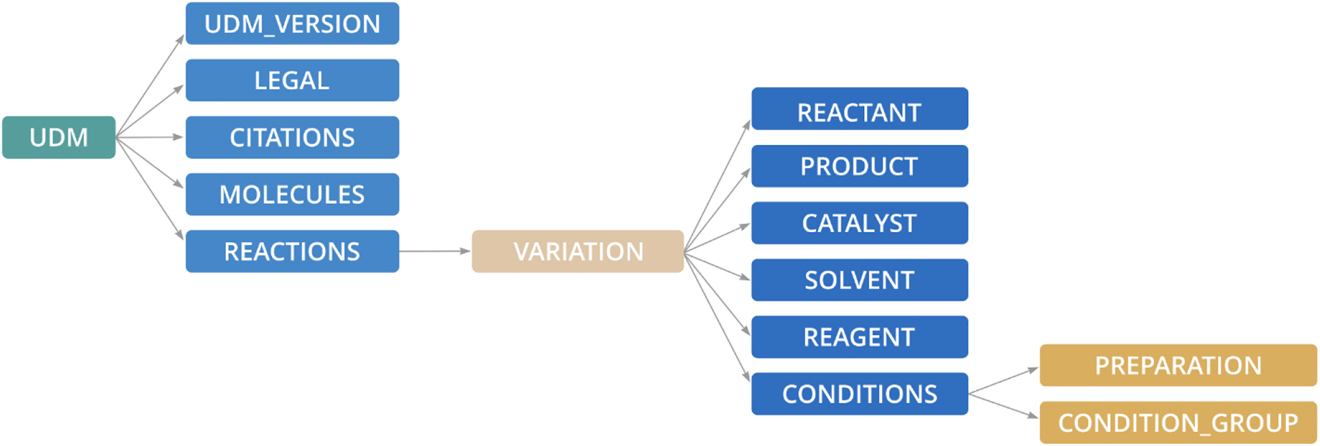

At its top level the Unified Data Model consists of the following five components:

1. The version of the UDM file format

2. Legal information about the data set

3. List of citations referenced by individual reaction records

4. List of molecules involved in reactions in the data sets in various roles: reactants, products, catalysts, solvents or generic reagents. Similar to the citations, they are referenced from different parts of the reaction hierarchy.

5. Reaction hierarchy – the core part of the UDM.

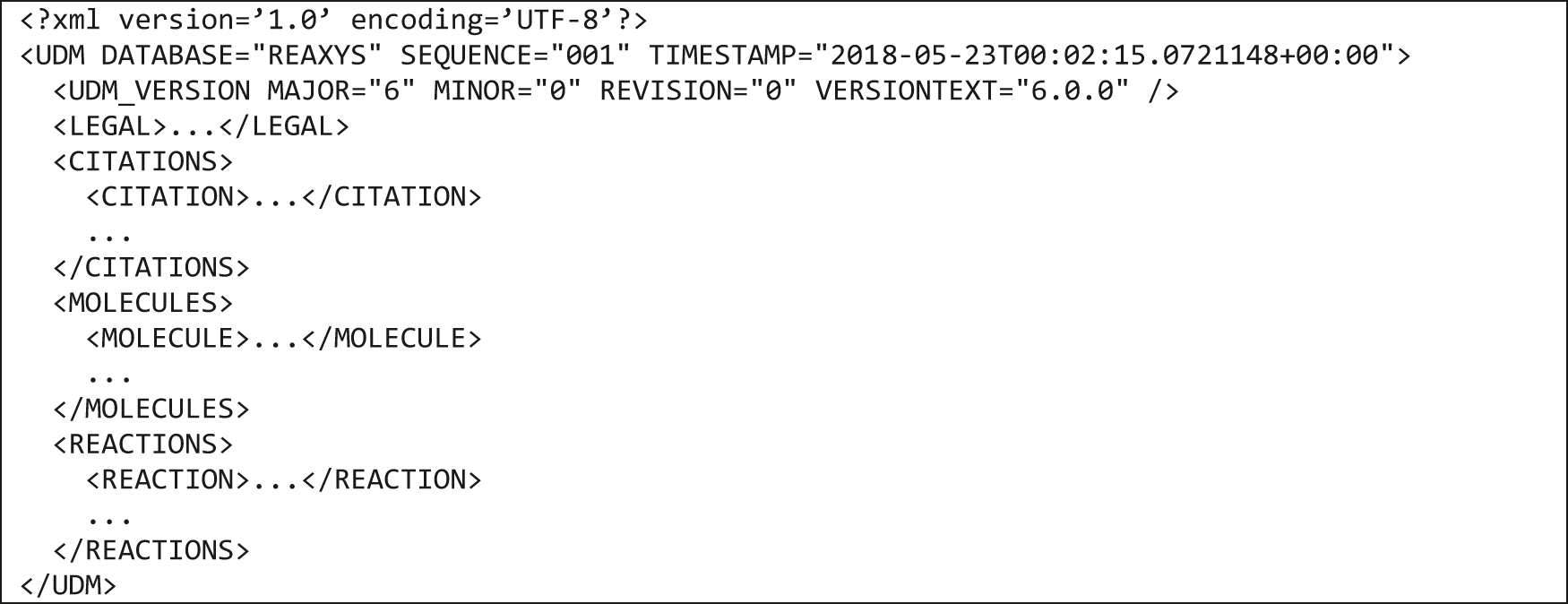

A high-level schema of the UDM is presented in Fig. 4.

Top-level elements of the Unified Data Model.

As mentioned earlier, the UDM XML file format is described by an XML schema that defines the allowed elements, their types and additional constraints on their values. The XML schema is also an XML document adhering to another XML schema. The XML Schema provides a rich set of pre-defined simple data types that can be associated with individual elements, for example, date, string, integer, positive integer, non-negative integer, negative integer, non-positive integer, decimal etc. UDM uses them to control values of elements like the DOI (Digital Object Identifier):

<xs:element name=“DOI” type=“xs:string”>

Or the YEAR of publication:

<xs:element name=“YEAR” type=“xs:positiveInteger”>

Another application of simple data types are enumerations employed by the UDM to create controlled vocabularies:

1. List of countries and their two- and three-letter codes based on ISO 3166 [10] with additional, frequently used names.

2. Reaction classes from the RXNO name reaction ontology [11].

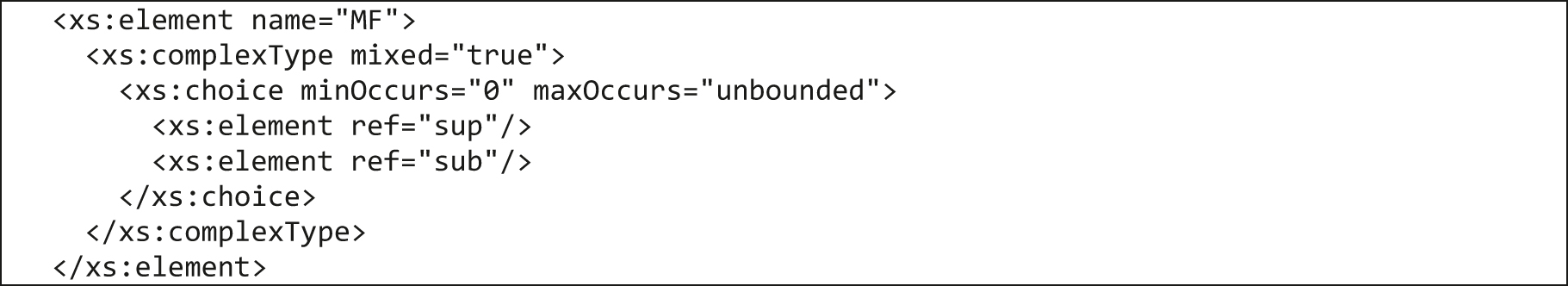

There are also complex, user-defined types (equivalent to records or structures in many programming languages) that can specify additional constraints on element values, define element attributes or group together multiple elements. The UDM MF (molecular formula) element illustrates the first case (Fig. 5) when strings are allowed to contain <sub> and <sup> XML tags to support subscripts and superscripts:

XML schema element defining molecular formula.

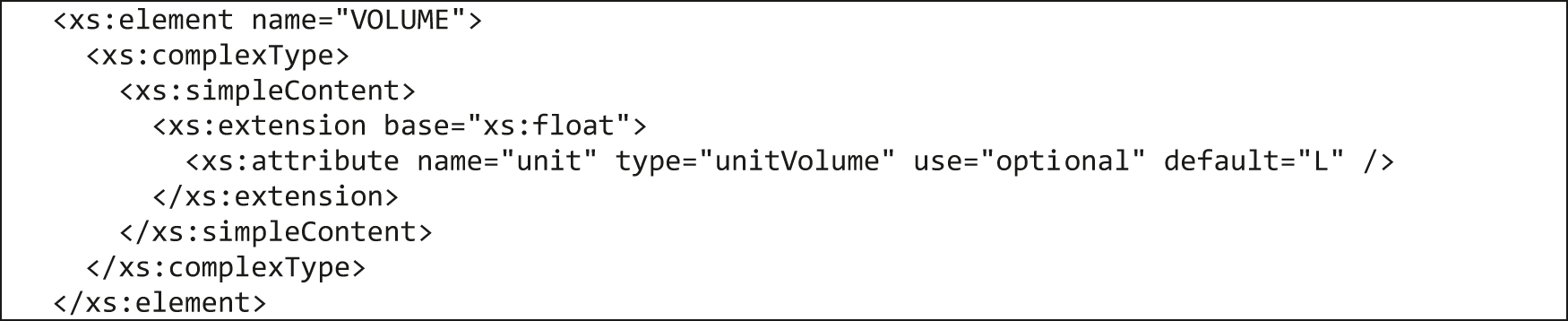

A simple example of using an additional attribute can be found in the VOLUME element, where the unit attribute represents the corresponding unit of measure. The volume units in the example below (Fig. 6) and other units of measurement are based on the Allotrope Foundation Ontologies (AFO) [13] with extensions to support units missing the AFO and special cases like “μL” and its English transliteration “uL”.

XML schema element defining volume of substance with the associate unit of measure.

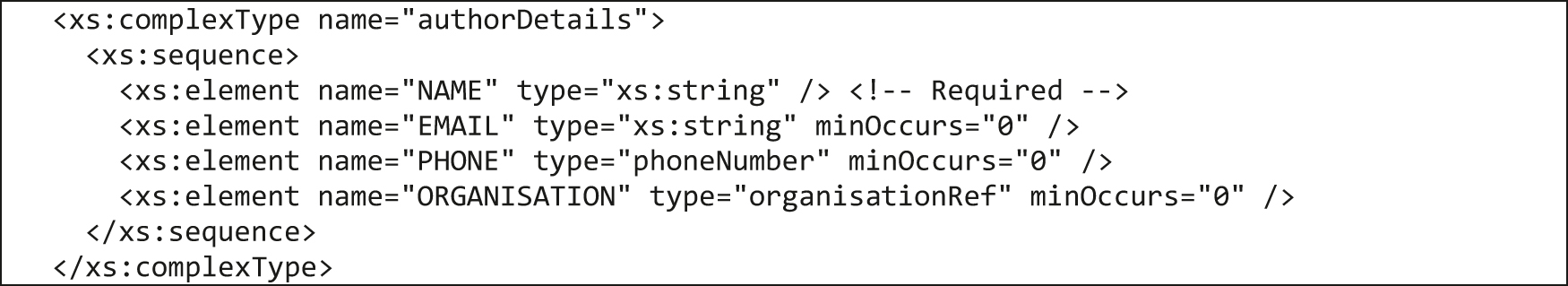

Finally, authorDetails is a relatively straightforward complex data type grouping other types that represents both publication authors and scientists directly performing reactions (as signed in ELNs). It is shown in Fig. 7.

Example grouping of XML elements into a sequence.

The XML Schema datatype system may seem to be complex at first sight, but it allows expressing many real-life scenarios, for example:

1. Numeric values where an exact value or a range value (minimum and/or maximum) are specified like pressure, time etc.

2. An extension of the above when the actual value changes from a minimum to its maximum at a specified increased speed, e.g., temperature of the reaction.

3. Equivalents of reactants that can be specified as numeric values (percentages by default) or using a special “excess” keyword.

Example UDM file

The following sections discuss a simplified UDM file describing synthesis of 2-nitrobenzoic acid from Reaxys.

At the top level, the UDM file consists of the five components mentioned above and most of them group the similar elements: citations, molecules or reactions as presented in Fig. 8.

High-level structure of a UDM XML file.

UDM version

The UDM_VERSION element specifies the UDM file format (XML schema) version used to encode the reaction data.

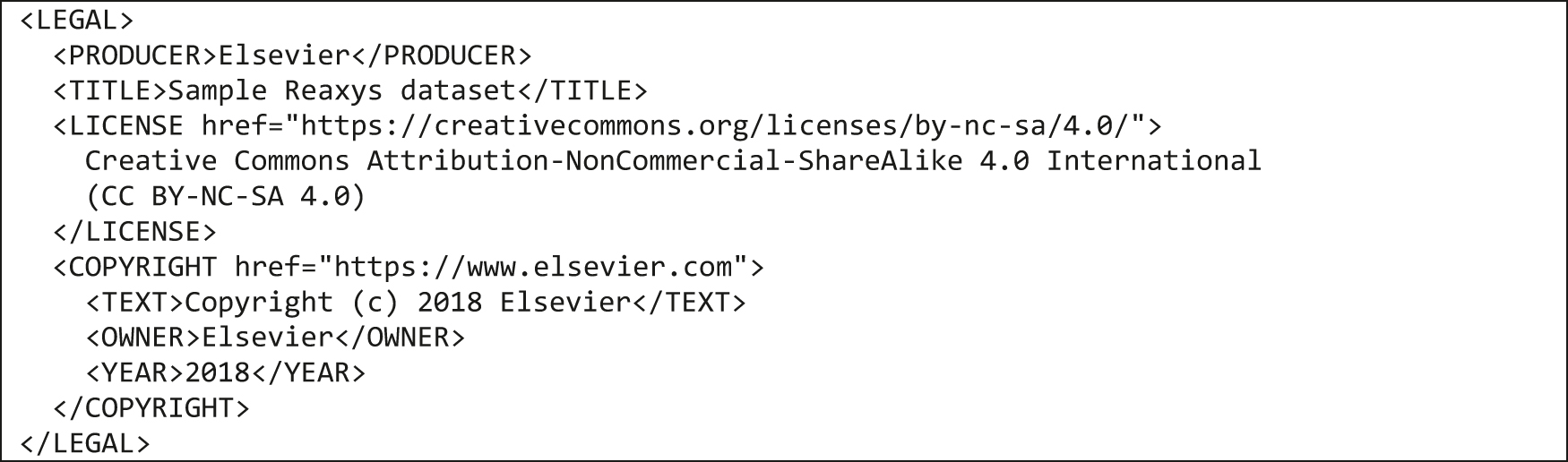

Legal information

Many of the widely used chemistry file formats are not designed to contain machine-readable legal information, which is essential for FAIRification and sharing of data. The UDM team recognized that it was important to clarify the allowed uses of a UDM data set and introduced an XML block making it explicit. It follows the Creative Commons ALM (Author, License, Machine-readability) recommendation, and it specifies the name of the dataset (TITLE), who should be attributed for the dataset (PRODUCER and COPYRIGHT) and how the data can be used (LICENSE) as presented in Fig. 9.

LEGAL block of a UDM file.

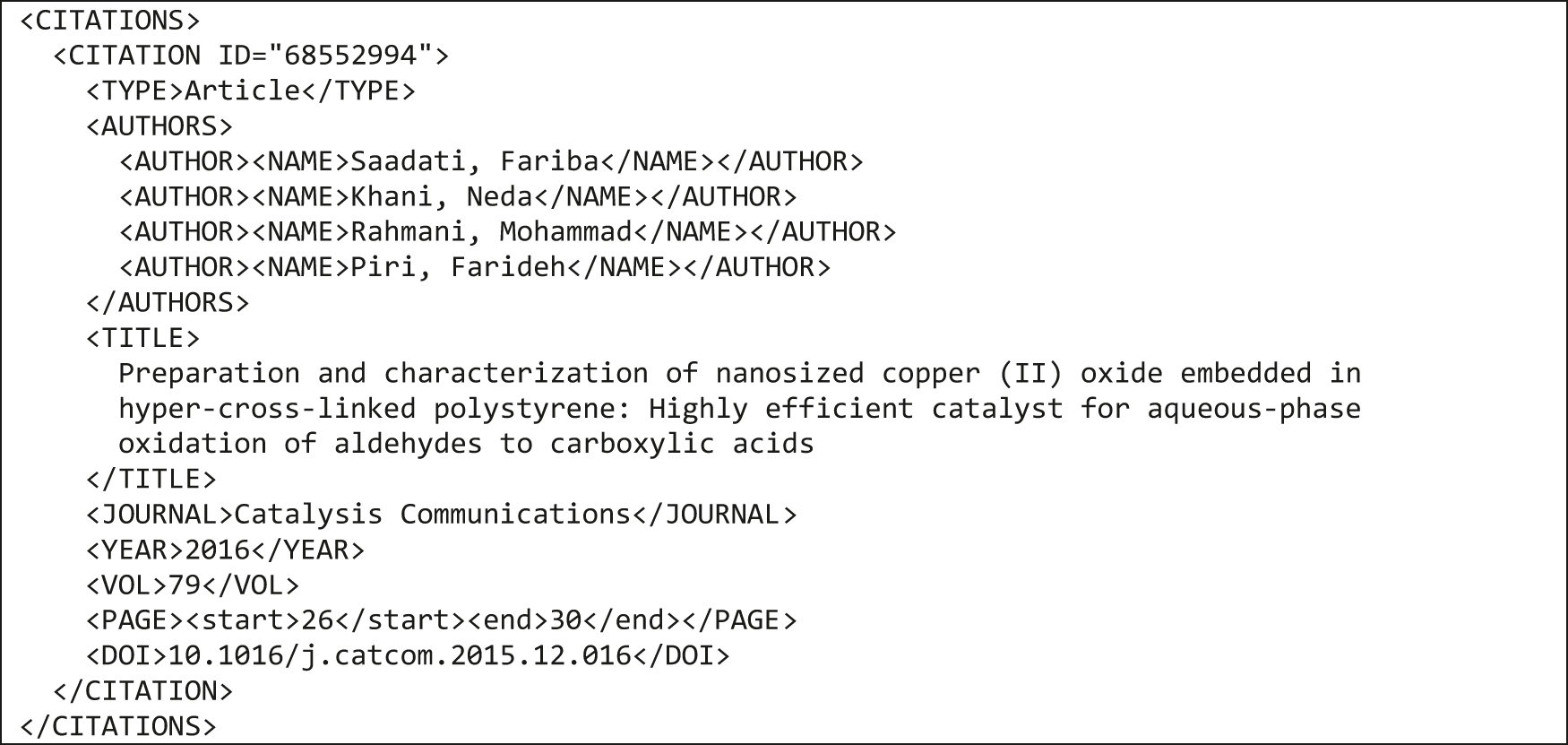

CITATIONS section

The CITATIONS block contains a list of preferable de-duplicated literature or patent references identified by unique IDs. The IDs are used to reference the citations from other parts of the UDM document in a particular molecule or reaction variation elements. The newest version of the UDM (6.0) allows the direct inclusion of complete citations instead of referencing them by ID. This feature was introduced to simplify the transformation of smaller RDfile sets, but it is not recommended as a general practice. A sample CITATIONS section is show in Fig. 10.

Example of a CITATIONS block containing a single literature reference.

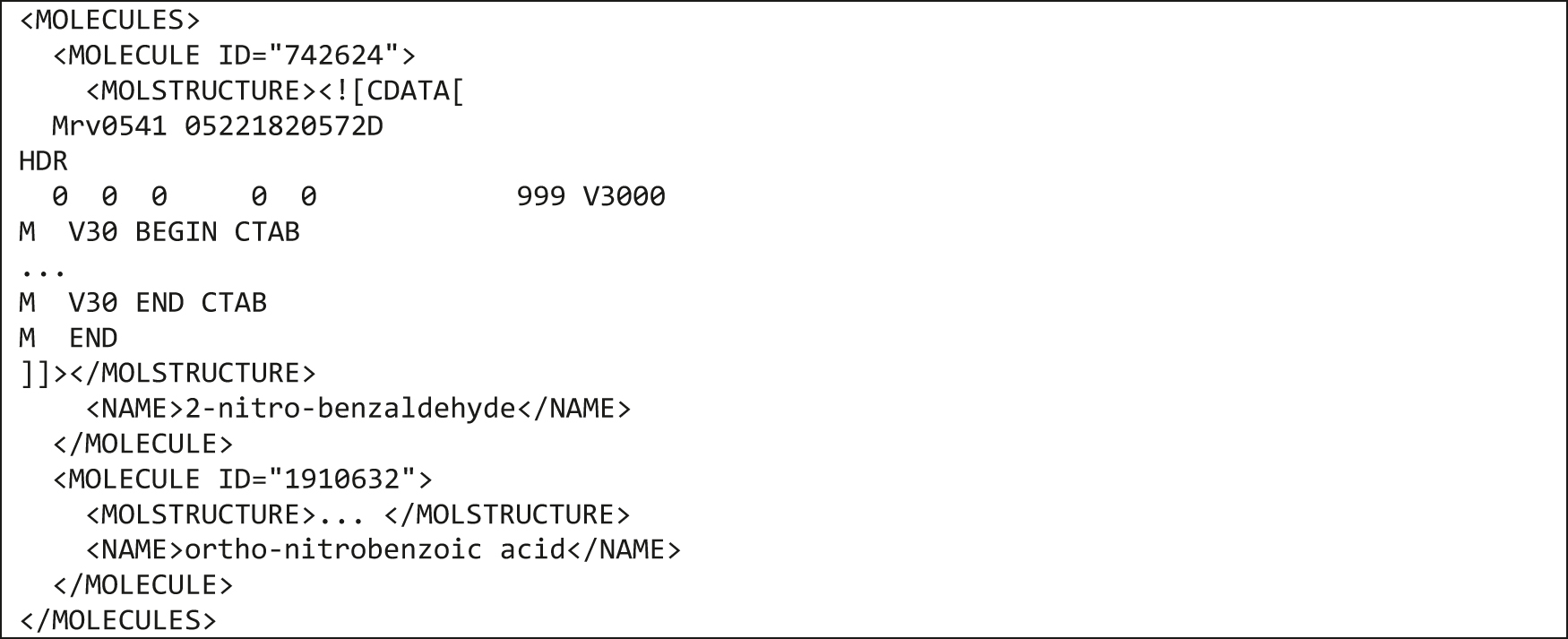

MOLECULES section

Molecules are represented in two locations within the UDM file: the RXNSTRUCTURE entity containing reaction diagram described in a later section and the MOLECULES block. The latter stores common properties of molecules involved in the reaction in various roles: reactants, products, solvents, catalysts or other types of reagents. Although the list of molecules is expected to be de-duplicated based on their structures to improve the data quality and to remove redundancy, it is not a hard requirement. Similar to citations, molecules have unique identifiers used to reference them from within the reactions. The UDM version 6.0 can also be directly embedded within reactions (again, this is not a recommended practice).

The de-duplication of molecular entities based on their structures eliminates the risk of inconsistent property values to be specified for the same compound. It also simplifies integration with molecule-centric applications, such as compound registry systems. For example, in a typical outsourcing scenario, reaction information provided by CROs is often ingested into two systems: reactions are stored in the customer’s ELN, and individual molecules are centrally registered.

Each molecule is described by its structure, various names and identifiers and an extensible list of properties. Initially, UDM allowed only molfiles to represent molecular structures. Still, later version added support for InChI [14], SMILES [15, 16], CDXML [17] and WLN—Wiswesser Line Notation [18, 19]. The inclusion of the last one was a light-hearted tribute to an important milestone in the history of the representation of chemical structures. Interestingly, PubChem [20, 21] contains over six thousand historical compounds with specified WLN. An even more exciting outcome of this tribute was an open-source WLN parser published by Sayle et al. [22] and contributed to both RDKit and Open Babel.

An example of an extremely simplified MOLECULES block containing two molecules is shown in Fig. 11.

Simplified example of the MOLECULES block.

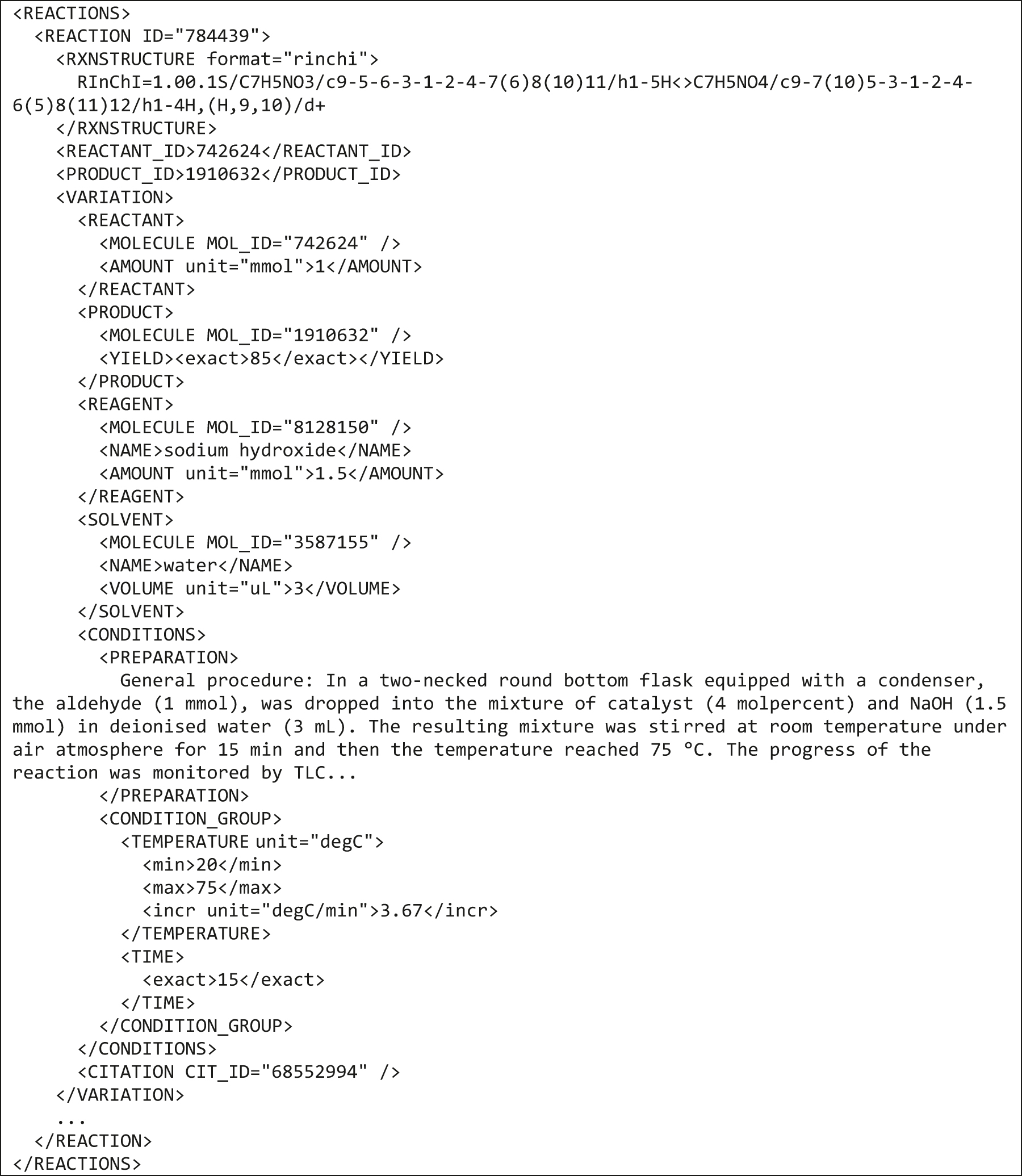

REACTIONS section

The REACTIONS section is at the very heart of the Unified Domain Model, and it contains a list of reactions with all the related data. A reaction is specified by a general single-step chemical transformation as a reaction diagram and a list of involved reactants and products. The reaction diagrams can be stored using one of the following common representations: RXN, RInChI, Reaction SMILES or CDXML. Multi-step reactions are not supported by the current UDM version 6.0, however, an UDM extension to describe multi-step reactions has been developed and is on the roadmap for release in version 6.1.

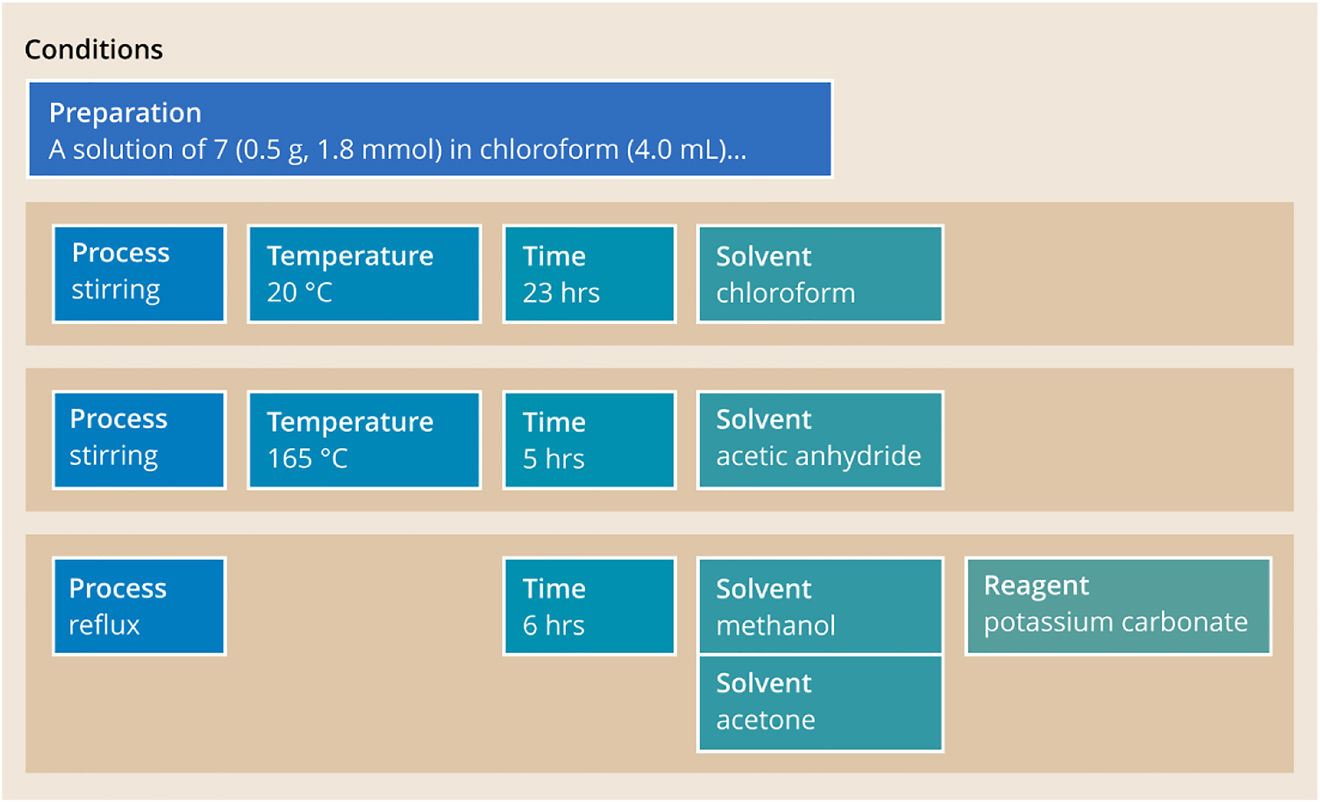

Each reaction has one or more variations that provide detailed information about how it was performed—its stoichiometric amounts, conditions, used solvents, catalysts and the outcomes (yield, purity and other analytical results). This approach is similar to many legacy reaction databases, which relied on the MDL ISIS/Host technology. An important part of a reaction variation is the CONDITIONS section which serves two purposes:

1. It stores an optional preparation section—a textual description of how the synthesis was performed. This part of the document may store the content in any format (plain text, HTML/XML, serialized binary documents) to support various approaches used by ELNs.

2. Following that, there can be zero, one, or multiple condition groups that gather conditions applied simultaneously. The purpose of this approach is to allow a precise description of the reaction stages.

Fig. 12 below illustrates the use of the CONDITIONS section.

Sample schematic UDM preparation section with a set of UDM condition groups.

The UDM also supports compound samples that are child nodes of compound playing different roles in a reaction like reactants, products, etc. The compound samples are used primarily to associate analytical results.

Fig. 13 contains a simplified example of REACTIONS section.

Sample reaction variation for the synthesis of 2-nitrobenzoic acid.

In the above example the reaction is represented as an RInChI string and the REACTANT_ID and PRODUCT_ID fields are references to molecules involved in the reaction. The VARIATION block below contains details about an individual experiment. The same chemical reaction may be performed in various conditions or using different catalysts and they are represented as individual VARIATIONs. As there may be experiment-specific data for individual chemical entities, for example, product yield, they are represented as more comprehensive elements such as REACTANT, PRODUCT and so on. Within these elements compounds from the MOLECULES block are referenced using their identifiers (<MOLECULE MOL_ID="3587155"/>) or alternatively complete compound information can be embedded since version 6.

Extensibility

The comprehensive capture of reaction data is one of the critical objectives of UDM. However, due to constant progress in synthetic chemistry (e.g., robotics) and virtual reactions, it is unrealistic to encode all possible and future data elements into the UDM. For that reason, the UDM contains extension points—a special SECTION entity which is defined in many places of the UDM hierarchy: reaction, reaction variation, condition group, molecule etc. They are designed to store any content which is a valid XML document. There are no additional restrictions put on sub-nodes of the SECTION element. It means that by default, the content of the SECTION elements will pass successfully a validation against the default UDM XML schema. However, it is also possible to create a specialized extension of the UDM XML schema that will provide additional checks of the structure and the content of SECTION sub-elements. An example of such extension is provided in the UDM documentation in its GitHub repository [23].

UDM versus other formats

There are several file formats currently used to represent reaction data: RDfile (BIOVIA), ELN XML (Perkin Elmer), CMLReact, Open Reaction Database Schema and, in the near future, RInChI.

RDfiles

MDL/Symyx/Accelrys/BIOVIA RDfiles (Reaction-Data files) [23, 24] have probably been the most widely used file format to store and exchange information about reactions for more than three decades. The RDfile and several other key formats representing chemical structures and chemical reactions (RXNfile, Molfile, SDfile, XDFile) were created by MDL Information Systems (MDL) in the 1980th and were originally only available to MDL customers but eventually published in 1991 [24]. Because of the MDL market position at those times, the MDL structure formats became the de facto standard for chemical databases straight after the publication of the format. The formats are open for general usage, but BIOVIA continues to own the formats used by many ELN vendors, pharma/chemical companies, data service providers and academics when working with chemical data. BIOVIA publishes yearly updates of the specifications under the title “CTFile Formats” [25] in the context of their yearly release cycle mostly in the beginning of December. An excellent review, including the historical development of many commonly used formats such as the standard MDL formats was written by Wendy A. Warr [26].

The actual RDfile format depends on the data model from where the data are exported from. It is hierarchically organized and may contain data for molecules as well as for reactions. The UDM version of the RDfile format uses a reaction represented as RXN file on top of the hierarchy. Each reaction may be characterized by one or more variations, each variation consists out of the reaction data for catalysts, reagents and solvents plus the reaction conditions (temperature, pressure, time, etc.) Because the molecules of catalysts, solvents and reagents are bound to the variation level, the structures and citations are denormalized and may occur multiple times within a file That may lead to inconsistencies within one file.

While offering a well-defined approach to store molecular structures and reaction diagrams, the RDfile format has very little support for storing any data model and data types for molecular and reaction properties. Reactions in a typical RDfile are represented by records, each consisting of an RXNfile block containing a reaction diagram and data fields with additional information about the process. Despite its popularity and wide adoption, the file format has serious shortcomings, which are addressed by the UDM:

1. It doesn’t define or enforce a standard data model to describe reaction information (conditions, outcomes etc.). It means that the same type of information is often represented differently in files generated by various systems or vendors. The UDM uses an XML schema to enforce a consistent data model.

2. It doesn’t use any controlled vocabularies for common properties (e.g. units of measure) or data types for various types of values – everything is text. The UDM relies on industry-standard taxonomies and controlled vocabularies.

3. The hierarchical data model used in most of the RDfiles (e.g. temperature values are kept in RXN:VARIATIONS(1):CONDITIONS(1):TEMP) is a convention based on the legacy ISIS/Host MDL product and is only briefy documented in the “Biovia CTFile Formats” document [25]. The UDM hierarchical model is explicitly defined and enforced by using XML.

4. There is a hardcoded limit of 80 characters on the length of data file lines and an implicit 7 bit ASCII character set resulting from the original implementation of MDL CTfile parsers. Longer lines of text should be split and a + mark character must be put in column 81 of such lines. One of the problems is that many RDfiles contain UTF-8 characters (non-English alphabets, for example, Greek letters) represented by more than one byte per character. The interpretation of their length is undefined in the context of RDfiles, i.e. “μ” is one character stored in two bytes). However, many vendors generating RDfiles ignore this part of the specification and generate lines of arbitrary length. UDM files are XML documents that explicitly use the UTF-8 character encoding and there are no artificial limits on the number of characters per line.

5. Validation, querying, and processing of RDfiles requires custom code as their format doesn’t rely on any widely supported format, for example, XML, JSON or ASN.1. UDM documents can be validated, searched and transformed using standard XML tools.

PerkinElmer ELN XML

The ELN XML file format was created by CambridgeSoft before it was acquired by PerkinElmer in 2011. It uses ChemDraw’s CDXML format [27] to represent molecular structure and chemical reaction diagrams and a set of generic XML entities: section, field, table, property, text and styled text (RTF content) to store the content of ELN records. Strangely, ELN XML files contain both data and presentation information (e.g. text color or table dimensions). The ELN XML files don’t have any formal model associated with them (DTD, XML Schema or RELAX NG) nor any controlled vocabularies, so they cannot be easily checked for correctness. Unfortunately, the actual format doesn’t seem to be officially documented and published.

The IUPAC international chemical identifier for reactions (RInChI)

The IUPAC Chemical International Identifier, InChI, is a widely accepted identifier, and its reaction extension, Reaction InChI (RInChI), is gaining popularity and increased usage for storing, searching, indexing and analyzing chemical reactions [28]. Vendors such as BIOVIA, ChemAxon, and Knime have included them in their applications as well as other academic and corporate institutions that are using them in their databases and data processing workflows.

While the RInChI serves primarily the role of an identifier for reactions additional layers are planned for the next release to cover atom mapping, enhanced stereo chemistry, and reaction condition data including flags for failing reactions. The UDM is planned to become an additional input format for the RInChI calculations [29].

CMLReact

CMLReact [30] is one of several modules of the Chemical Markup Language (CML) [31], and it uses similar technology (XML and XML Schema) to represent data models for molecules and reactions. However, there are significant differences between CMLReact and UDM. First of all, the UDM XML schema is significantly simpler and about ten times smaller (without vocabularies) than the combined core CML, CMLReact and STMML (Scientific-Technical-Medical markup language) [32] schemas covering similar representation domains (molecules, reactions, literature). CMLReact emphasizes a detailed description of molecules using its own CML model and chemical transformation, including a dedicated XML entity to represent electrons which can be associated with atoms and bonds or reactivity centers. The UDM takes a more pragmatic approach and allows using existing popular representations for both molecules and reactions (molfiles, SMILES, Rxnfiles etc.). CMLReact allows multistep reactions, while UDM focuses on single-step reactions at the current stage of its development but provides a detailed description of individual stages more detailed and explicit representation of reaction conditions.

Moreover, UDM has the concept of the reaction variation missing in CMLReact. Overall, the difference between the two approaches seems to reflect different objectives of the two representations. CMLReact has a strong focus on a comprehensive description of chemical transformation and builds its chemistry model, while UDM re-uses concepts from existing and historical databases and ELNs to standardize and simplify data exchange between different systems.

Open reaction database schema

The Open Reaction Database (ORD) Schema [33] is the newest approach to the representation of chemical reactions with special emphasis on “supporting machine learning and related efforts in reaction prediction, chemical synthesis planning, and experiment design” [34]. Similarly to UDM, the ORD Schema focuses on single-step reactions. In contrast to UDM which uses human-readable XML files, the ORD Schema uses Protocol Buffers [35]—an extensible mechanism for serializing structured data in various programming languages such as Python, C++, C#, Java etc. Protocol buffers define messages (equivalent to XML complex types) to describe data structures which are next converted to classes in individual programming languages. The classes are serialized to the Protobul binary files which can be subsequently de-serialized in applications.

The main difference is that UDM was designed to be an exchange data format which can be validated, queried and processed not only using programming languages, but by using generic XML tools or other data processing applications that support XML. The ORD Schema requires implementing its data model directly in application code and relies on a vendor-specific technology (Google Protocol Buffers) rather than open standards (XML and XML Schema).

Alternative representations of UDM documents

Even though UDM is currently defined using an XML schema, it is possible to create equivalent document models using a different representation, for example, JSON [36]. The XML schema technology was used due to its maturity and high level of standardization by W3C [37] and available tools for processing XML documents. JSON is used primarily as a communication format for web applications and configuration files. Although there are ongoing activities on JSON-equivalent versions of XML technologies like JSON Schema [38], they are at an early stage, not yet widely used, and their adoption would be risky and premature. Over time we could envisage a semi-automatic translation of the UDM XML schema definition to the JSON schema and adoption of JSON for the exchange of reaction data, but still rely on XML for the canonical definition of the UDM.

UDM challenges and how to address them

There are a couple of important challenges that any open data format will need to address. One is the adoption, and another is a proper guidance provided to the developing community on best practices and creation of compatible extensions to the original model. This is why the governance is of vital importance for any format that wants to become a standard. There are, however, opportunities with the open data format that allow various groups to experiment and to try how it fits with the original format/model. For example, there is a publication by M. Kappler and C. Lowden on BioChemUDM in this issue of the journal. Community experiments are crucial for the evolution of any data standard. After all, the standard is used by people and organizations who are the most interested in developing it.

To address the adoption challenge, one of the latest Post Pistoia Alliance UDM team activities included a qualitative and detailed investigation on pain points of chemical reaction data processing within a small group of chem/data scientists. The questions asked by the UDM project team included:

Can you give example(s) of your workflows when you extract, combine, store, analyze and use data?

What problems do you face when extracting, combining, storing, analyzing, and using data?

How do you communicate with external and internal parties in terms of data exchange?

Where in your existing workflows do you see use-cases for using UDM exchange format?

What value will UDM bring to your work? What problem will it solve?

What would you need to overcome/what could help adopting the UDM format?

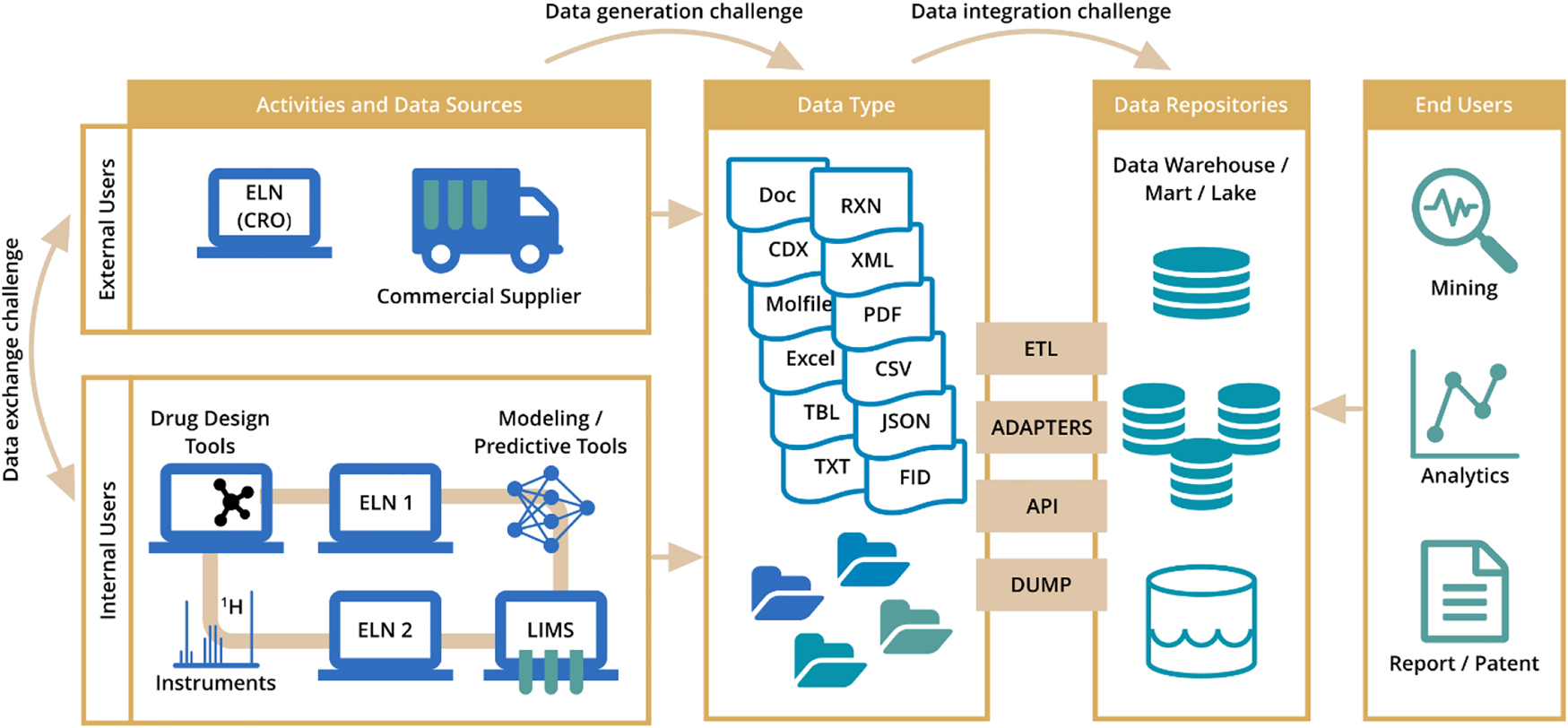

What we have learned in terms of problem statements can be summarized in the diagram below (Fig. 14).

Reconfirmed pain points in reaction data exchange, management, and analysis.

As quantitative statements are not possible to make due to the small size of the group, we were, however, able to identify the use cases and to discuss the value of the UDM. For example, reaction data integration from various ELNs is still a challenge for many pharmaceutical companies and they spend a good amount of time cleaning and integrating the data into one data repository. Reaction data preparation for ingestion into in-house repositories from other data sources including ELNs take a lot of time too due to the disparity of the data. Data exchange with CROs and pharma companies is suboptimal and most of it is happening via file sharing (e.g., PDF documents). It is impossible to collect information from these files into one database. Data cleanup and preparation for the modelling project is also tedious and time consuming due to lack of a common standard. Another increasingly important activity is data exchange between various applications, for example, from the database where a scientist has searched for a reaction of interest to the import of this reaction in their synthesis predictive tool to be able to modify the product or the reactant molecule and to run a new prediction based on the modifications. Last but not least, the data exchange from different laboratory devices is hampered by the vendor specific formats which are not interoperable.

The value of the UDM is defined by these use cases and how they help solving each issue, so what are the adoption barriers that slow down the adoption. A few important are elaborated on in the next paragraph.

The users rarely see the format being included in the ELNs or other applications dealing with chemistry data up to now. For example, if one draws and searches a molecule, collects additional information on the synthesis and conditions and wants to export it into another tool, UDM export and import buttons would simplify the work. The other barrier is that direct interconversion tools from the UDM to RDfile or vice versa or JSON to UDM and vice versa have not yet been developed due to a lack of funding so that workarounds like protocols of Biovia’s Pipeline Pliot must be used for this transfer process. In addition, UDM was focusing on the reactions and analytics data and, for example, bioassay data extension was planned afterwards and is still on the UDM’s roadmap. However, it is also understood from the discussions that the senior management in many pharma companies begin to understand the problem, the scale and the value of having a data standard once large data integration projects are planned. Although, the situation is changing as AL/ML methods developed by many pharma companies require lots of efforts to clean the data, lots of time spent on harmonization and integration of the data and the involvement of people with cheminformatics and data management skills. To address the adoption challenges, the UDM team is reaching out to ELN providers and other stakeholders to discuss UDM export/import functionalities in their tools.

UDM next steps

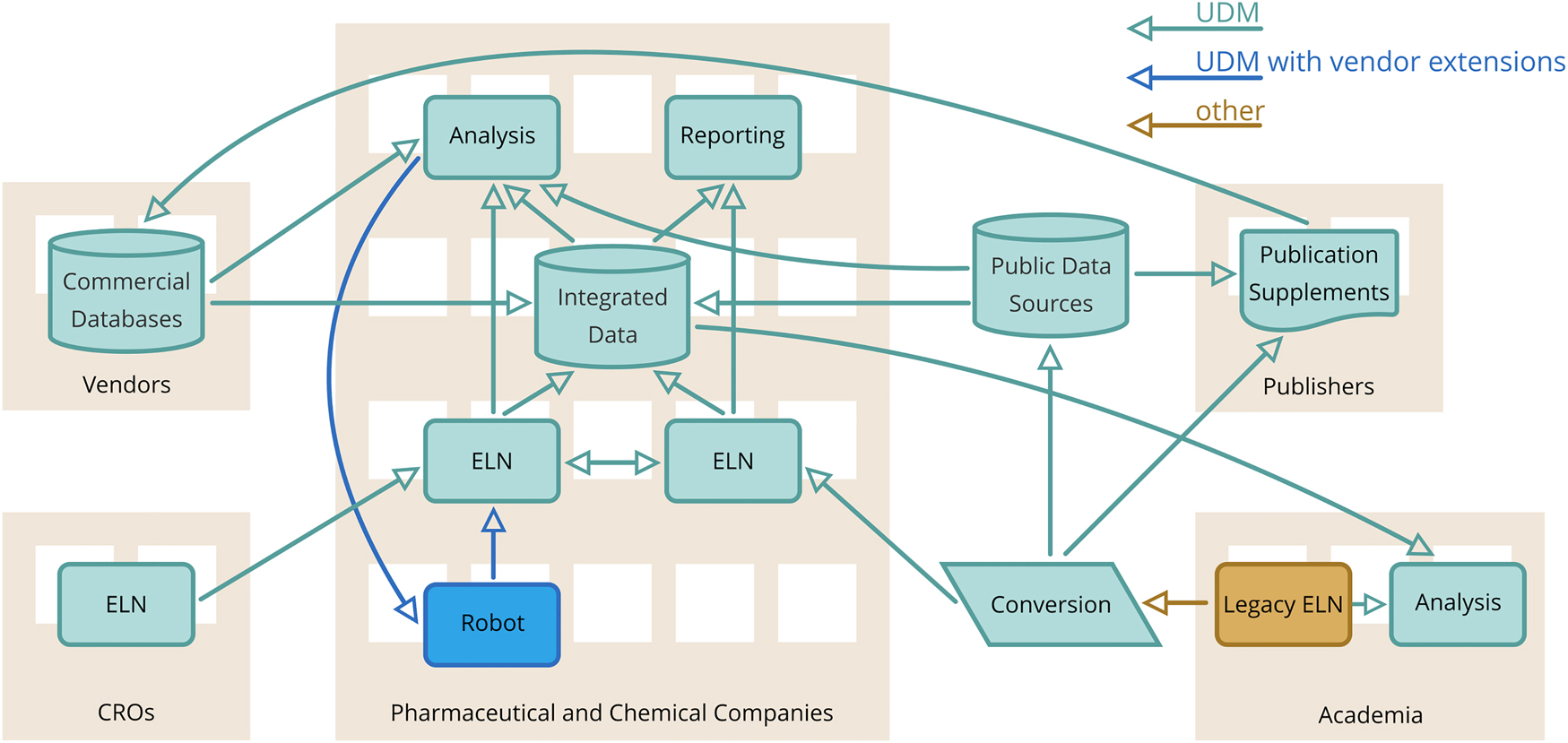

Our vision is UDM to become a common data exchange format used by different informatics systems dealing with chemical reactions so that data can be seamlessly exchanged without losing content and observing intellectual property constraints. Fig. 15 illustrates this vision by representing an ideal information flow between various types of systems that either use the core UDM or UDM with additional vendor extensions, e.g., for synthetic robot data specific to the used equipment. This would remove the need of constant processing and curation of data files using slightly different data models or data formats which is the situation still present in many organisations.

Vision of UDM usage at scale.

UDM as a community-based project

The Pistoia alliance closed the UDM project with the successful delivery of version 6.0. The UDM has now been transferred into an open-source, community-led project and, as a result, the UDM is available under the MIT license. The current version of the UDM XML schema, its vocabularies, example datasets, sample format conversion code and documentation are available on GitHub [39]. The UDM team consisting of vendors and life science organizations in collaboration with Elsevier, Pistoia Alliance and Roche continue to sustain the project and is looking for funding as well as to better define governance and decision-making processes.

Further developments

Further developments of the UDM exchange format will depend on how successful the adoption of the UDM is. Scientific innovations, industry trends and funding will, of course, have their impact, however, the immediate identified needs are improved documentation by providing comprehensive examples, full support for multistep reactions and better support for the results of reaction predictions. Medium term goals include extensions to cover biological data, chemical mixtures, recipes, formulations and materials.

Advances in predictive retrosysthesis applications requires support for exchange of synthesis routes between the predictor, the chemists and automated synthesis setups for a fully integrated synthesis model development. Therefore an upcoming UDM extension to be released with UDM version 6.1 will address this need. This extension will introduce the ROUTE concept to describe a multi-step reaction, where each step of a ROUTE can be defined by referencing a single-step reaction. Step-specific properties can be defined, including computational parameters, to assist adoption of UDM in the emerging field of synthesis model development.

One of the factors helping with the adoption of the UDM would be an open source UDM Toolkit which could be used to address the needs of high quality, analysis-ready data from chemical synthesis experiments. Its core functionality would implement two tasks:

1. Conversion to UDM and content enrichment—high-fidelity conversion of reaction data from the most popular data formats to UDM, including their normalization, reorganization to make them more suitable for further analysis and calculation of derived properties.

2. UDM validation and curation—verification and automated as well as manual curation of data records with user-friendly visual feedback and interface

Longer terms perspectives might discuss the potential of the Unified Data Model as a foundation for the Universal Data Model.

Article note:

A collection of invited papers on Cheminformatics: Data and Standards.

Funding source: BIOVIA

Award Identifier / Grant number: Unassigned

Funding source: BMS

Funding source: Elsevier

Funding source: GSK

Funding source: Novartis

Funding source: Roche

Funding source: Pistoia Alliance

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the entire UDM team and community for stimulating discussions and their contributions. In particular, to Roman Affentranger from Novartis, who was the original UDM project champion at Roche, the role was taken over by Brian Jones at a later stage. Hans Kraut from InfoChem (currently DeepMatter) made a remarkable contribution by his expertise and a donation of a sample SPRESI dataset that was converted to UDM and included in its release. Similarly, Elsevier donated a small dataset from the Reaxys database. Finally, Becky Upton and Nick Lynch from the Pistoia Alliance facilitated the transfer of the UDM license from the Pistoia owned license to the MIT license and supported the transfer of the project to a broader community.

-

Author contribution: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: This work was supported by BIOVA, BMS, ELSEVIER, GSK, Novartis, Roche and Pistoia Alliance.

-

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

[1] F. K. Beilstein. Handbuch der organischen Chemie, Hamburg (1881).Search in Google Scholar

[2] W. T. Wipke, J. D. Dill, S. Peacock, D. Hounshell. Search and retrieval using an automated molecular access system. in Presented at the 182nd National Meeting of the American Chemical Society, New York (1981).Search in Google Scholar

[3] L. Chen, J. G. Nourse, B. D. Christie, B. A. Leland, D. L. Grier. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 42, 1296 (2002), https://doi.org/10.1021/ci020023s.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] IUPAC, Graphical Representation Standards for Chemical Reaction Diagrams, https://iupac.org/projects/project-details/?project_nr=2017-036-2-800, (accessed Jun 2, 2022).Search in Google Scholar

[5] World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). W3C XML Schema Definition Language (XSD) 1.1, https://www.w3.org/TR/xmlschema11-1/.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Copyright © 2021 Elsevier Life Sciences IP Limited. Reaxys is a trademark of Elsevier Life Sciences IP Limited, used under license.Search in Google Scholar

[7] A. J. Lawson, J. Swienty-Busch, T. Géoui, D. Evan. ACS (Am. Chem. Soc.) Symp. Ser. 1164 (2014).Search in Google Scholar

[8] F. Agnetti, M. Bensch, H. Biller, M. Blapp, B. Cheikh, G. Blanke, J. Degen, B. Dienon, T. Doerner, G. Doernen, F. Farshchian, W. Gotzeina, P. Hilty, R. Horstmoeller, T. Jeker, B. Jones, M. Kappler, A. Momin, A. Regoli, D. Ribaud, B. Starck, D. Stoffler, K. Weymann, P. Udupa. Intuitive and integrated browsing of reactions, structures, and citations: the roche experience. in 245th National Meeting of the American Chemical Society, New Orleans, LA, April 7–11, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[9] N. Jung. Documentation and publication of reactions with Chemotion ELN and Repository, NIH Workshop on Reaction Informatics, May 18–20 (2021), https://www.piug.org/PIUG-PF/10518961 (accessed Oct 24, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

[10] ISO 3166 Country Codes available at https://www.iso.org/iso-3166-country-codes.html.Search in Google Scholar

[11] RXNO—reaction ontologies. https://github.com/rsc-ontologies/rxno.Search in Google Scholar

[12] The Allotrope Framework. https://www.allotrope.org/allotrope-framework.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Allotrope Foundation Ontologies (AFO), https://www.allotrope.org/ontologies.Search in Google Scholar

[14] S. R. Heller, A. McNaught, I. Pletnev, S. Stein, D. Tchekhovskoi. J. Cheminf. 7, 23 (2015), https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-015-0068-4.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] D. Weininger. J. Chem Inf. Comput. Sci. 28, 31 (1988), https://doi.org/10.1021/ci00057a005.Search in Google Scholar

[16] D. Weininger. J. Chem Inf. Comput. Sci. 29, 97 (1988).10.1021/ci00062a008Search in Google Scholar

[17] The CDXML text-based file format, https://www.cambridgesoft.com/services/documentation/sdk/chemdraw/cdx/IntroCDXML.htm.Search in Google Scholar

[18] W. J. Wiswesser. A Line-Formula Chemical Notation, Thomas Crowell Company publishers, New York (1954).Search in Google Scholar

[19] E. G. Smith. The Wiswesser Line-Formula Chemical Notation, McGraw-Hill Book Company Publishers, New York (1968).Search in Google Scholar

[20] Y. Wang, J. Xiao, T. O. Suzek, J. Zhang, J. Wang, S. H. Bryant. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W623 (2009), https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkp456.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] National Institutes of Health (NHI), https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.Search in Google Scholar

[22] R. Sayle, N. O’Boyle, G. Landrum, R. Affentranger. Open sourcing a Wiswesser Line Notation (WLN) parser to facilitate electronic lab notebook (ELN) record transfer using the Pistoia Alliance’s UDM (Unified Data Model) standard, poster at BioIT World (2019).Search in Google Scholar

[23] UDM XML Schema Change Log, https://github.com/PistoiaAlliance/UDM/blob/master/Docs/ChangeLog.md.Search in Google Scholar

[24] A. Dalby, J. G. Nourse, W. D. Hounshell, A. K. I. Gushurst, D. L. Grier, B. A. Leland. J. Laufer. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 32, 244 (1992), https://doi.org/10.1021/ci00007a012.Search in Google Scholar

[25] The most up-to-date version of description of RDfiles can be requested from, https://discover.3ds.com/ctfile-documentation-request-form.Search in Google Scholar

[26] W. A. Warr. WIREs Computational Molecular Science 1, 557 (2011), https://doi.org/10.1002/wcms.36.Search in Google Scholar

[27] CambridgeSoft CDX File Format, https://www.cambridgesoft.com/services/documentation/sdk/chemdraw/cdx/.Search in Google Scholar

[28] G. Grethe, G. Blanke, H. Kraut, J. M. Goodman. J. Cheminf. 10, 22 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-018-0277-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] G. Blanke, G. Grethe, H. Kraut, I. Öri, J. H. Jensen, J. Goodman. The International Chemical Identifier for Reactions, InChI Working Groups Meeting – April 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[30] G. L. Holliday, P. Murray-Rust, H. S. Rzepa. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 46, 145 (2006), https://doi.org/10.1021/ci0502698.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] P. Murray-Rust, H. S. Rzepa. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 43, 757 (2003).10.1021/ci0256541Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] P. Murray-Rust, H. S. Rzepa. Data Sci. 1, 128 (2002), https://doi.org/10.2481/dsj.1.128.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Open Reaction Database – The Schema, https://docs.open-reaction-database.org/en/latest/schema.html.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Open Reaction Database – Overview, https://docs.open-reaction-database.org/en/latest/overview.html.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Protocol Buffers, https://developers.google.com/protocol-buffers.Search in Google Scholar

[36] JSON (JavaScript Object Notation), https://www.json.org/json-en.html.Search in Google Scholar

[37] XML Schema, https://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema.Search in Google Scholar

[38] JSON Schema, https://json-schema.org/.Search in Google Scholar

[39] UDM GitHub repository, https://github.com/PistoiaAlliance/UDM/.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Cheminformatics: data and standards a Pure and Applied Chemistry special issue

- Invited papers

- Ontologies4Chem: the landscape of ontologies in chemistry

- IUPAC specification for the FAIR management of spectroscopic data in chemistry (IUPAC FAIRSpec) – guiding principles

- Launching a materials informatics initiative for industrial applications in materials science, chemistry, and engineering

- Analysing a billion reactions with the RInChI

- Reaction SPL – extension of a public document markup standard to chemical reactions

- RSC CICAG Open Chemical Science meeting: integrating chemical data from two symposia and a series of workshops

- UDM (Unified Data Model) for chemical reactions – past, present and future

- An overview of the JCAMP-DX format

- Data format standards in analytical chemistry

- BioChemUDM: a unified data model for compounds and assays

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Cheminformatics: data and standards a Pure and Applied Chemistry special issue

- Invited papers

- Ontologies4Chem: the landscape of ontologies in chemistry

- IUPAC specification for the FAIR management of spectroscopic data in chemistry (IUPAC FAIRSpec) – guiding principles

- Launching a materials informatics initiative for industrial applications in materials science, chemistry, and engineering

- Analysing a billion reactions with the RInChI

- Reaction SPL – extension of a public document markup standard to chemical reactions

- RSC CICAG Open Chemical Science meeting: integrating chemical data from two symposia and a series of workshops

- UDM (Unified Data Model) for chemical reactions – past, present and future

- An overview of the JCAMP-DX format

- Data format standards in analytical chemistry

- BioChemUDM: a unified data model for compounds and assays