Abstract

The JCAMP-DX format is the most widely used vendor-independent data standard in spectroscopy. Based on the ASCII character set, the first standard was published for infrared spectroscopy in 1988 and over the years additional standards have been published covering most of the major spectroscopic techniques. This paper provides an overview of the JCAMP-DX standards, including a brief historical review. This is followed by a basic description of the format, example applications and a discussion of its continuing evolution.

Background

The Joint Committee on Atomic and Molecular Physical data (JCAMP) was established to generate better and broader reference spectroscopic data libraries. JCAMP was sponsored by the: American Chemical Society (ACS), American Physical Society (APS), American Society for Mass Spectrometry (ASMS), American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), Optical Society of America (OAS), Society for Applied Spectroscopy (SAS), and Spectroscopy Society of Canada (SSC). The scope of JCAMP was originally as follows:

The Joint Committee will generate, collect, evaluate, edit, and approve the publication and encourage the distribution of atomic and molecular physical data in suitable form to serve as references for pure compounds and mixtures.

Early on, the hurdles of collecting data from a multitude of different instruments and vendors, each with their own native binary data formats, not to mention operating systems and software versions, became very apparent. Paul A Wilks had encountered a similar issue from an industrial standpoint, as he pointed out to an interviewer. He had been contacted by a friend at Dupont who had noted that they had 32 IR instruments by four different manufacturers in their organization, and the different makes wouldn’t talk to each other. This created problems when trying to transmit spectral data. He contacted JCAMP, who were struggling with the same problem, and they agreed to sponsor a committee to find a way to communicate among the various companies. Paul Wilks was able to get representatives from each of the instrument manufacturers to attend a kick-off meeting at the landmark 1983 Pittcon analytical conference and the JCAMP Task Force on Spectral Data Portability was born under Paul’s chairmanship. The subcommittee commenced work and, through the efforts of the team including Robert S. [Bob] McDonald, a retired spectroscopist from General Electric and one of the pioneers of infrared spectroscopy, together they developed the first JCAMP-DX standard publication (Fig. 1).

Bob McDonald in a heated discussion on a finer point of one of the later JCAMP-DX standards (1996).

Bob McDonald was an industrial spectroscopist who, when working at the Stamford Research Laboratories of the American Cyanamid Company, was involved with the development of one of the first commercial infrared spectrometers, the Perkin-Elmer Model 12. He spent most of his working life with the Corporate Research and Development Center, General Electric Company in Schenectady, New York, USA working on materials characterization mainly by infrared spectroscopy, and he went on to serve with distinction for many years in the JCAMP-DX subcommittee and later in the IUPAC Subcommittee on Electronic Data Standards (SEDS).

The basics of the JCAMP-DX format

The JCAMP-DX standards were developed specifying the minimum information content required to successfully move spectroscopic data from one instrument vendor’s software package to another computer system without loss of resolution and to enable further processing within the second package. The main interest was to find a method to build much larger reference data collections than was currently possible at that time. It is a great testimony to the authors of the original infrared specifications, who worked closely with all the major instrument manufacturers on the various drafts, that, despite changing drivers and stakeholders in the scientific data arena the JCAMP-DX data standards are still as popular as ever and performing as specified more than 30 years after their initial development. The Task Force needed to consider different aspects and interests of the stakeholders when designing a standard file format. This data exchange capability was being demanded by end-users, who wished to transfer spectra between different spectrometers in their own and/or other laboratories. Spectrometer manufacturers’ existing data systems used different proprietary binary file formats; they recognized the need but were also concerned about possible effects on their commercial interests. Nevertheless, eight vendors (Analect, Bomem, Digilab, IBM Instruments, Mattson, Nicolet, Perkin-Elmer and Sadtler Laboratories) financially supported the project via donations to JCAMP and via technical representatives on the Task Force, providing in-kind contributions of their staff time and sample files for round-robin testing.

An early decision was to base the JCAMP-DX protocol on the ASCII character set as a common denominator among the various operating systems and computer types then on the market and deployed by spectrometer vendors. Everyone could read and write ASCII files! This also had the advantage that the files would be human readable and could be printed out for simple checking. The next decision was on how the actual numerical data should be stored and here they chose a complex method that has delivered some great unforeseen benefits to this day. Clearly it would be possible to write out the number using ASCII numbers but after considerable work, an ingenious encoding system was adopted that could store the numerical spectroscopic data in full spectrometer resolution using fewer bytes. This encoding also ensured maximum compatibility and longevity of the data. During the development of the NMR standards an intense debate raged amongst contributors and stakeholders around the requirement to store data in ASCII as opposed to a binary format due to a perceived explosion in the file size making the format unmanageable. Depending on the encoding software, it is possible to produce data exchange files with no loss of data, and the compression algorithms used could often yield ASCII exchange files that were smaller than the original binary spectrometer files, again with no loss of data.

The final step was to get agreement on the absolute minimum number of metadata that needed to be included with the numerical data to make sense of the spectrum and facilitate the correct display. An irreducible core of key/value pairs was agreed upon as well as a large number of optional standardized vocabulary terms that may or may not have been present on all of the contributing manufacturers’ systems.

In 1990 the former German Federal Ministry of Research and Technology (BMFT) set-up a large funding program covering specialized information in chemistry. Amongst the subjects funded was spectroscopy. The intentions of the German government, however, were much broader, including funding for converting Beilstein, Gmelin, and the Detherm Database into electronic forms. Within the spectroscopy project, the Institute of Spectrochemistry and Applied Spectroscopy (ISAS) in Dortmund was given the responsibility for the evaluation of infrared spectra and NMR data. The Max-Planck-Institut (MPI) für Kohlenforschung in Mülheim/Ruhr was given the responsibility for the evaluation of mass spectra. Eventually all the databases were hosted and made available to the public through STN International. Again, the ability to collect data from different collaborators with spectrometer systems of fundamentally different design, operating systems, and instrument control programs became a significant hurdle.

The German project saw that, for infrared spectra, the JCAMP-DX format had become the accepted and implemented data format of choice. However, no progress had been made in the other spectroscopic fields of interest, and comparable formats for NMR and MS data did not exist at that time. For example, tables of NMR peak lists were typically recorded in publications, but for full NMR spectra, only images were used. To redress this deficiency, the project decided to provide funding to support the development of a JCAMP-DX format for NMR data for spectra and/or FIDs. As with the work on the infrared standard, the first step was to define Labeled Data Records (LDRs) for all the metadata needed to correctly understand and interpret the data. Around this time, Bob McDonald suggested the JCAMP-DX NTUPLES structure for storing data tables. In this case data tables would be used to contain the real part and the imaginary part of the FID. This solved the problem that data quality experts were recommending at that time that the NMR data needed to be collected as FIDs rather than transformed spectra, and different vendors had either the real and imaginary data points aligned to the same time point or offset from one another making a classical numerical array structure difficult to encode. The JCAMP-DX NTUPLES format has since been extensively used for NMR data (see Section 3).

Over a period of several years, new techniques were added to the list of JCAMP-DX standards. In the field of spectroscopy, the publication and successful implementation of the JCAMP-DX protocols made it possible to transfer not only infrared and Raman spectroscopy datasets, but for a range of techniques, including Mass Spectrometry (MS), Nuclear Magnetic resonance Spectroscopy (NMR), Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS), Electron Magnetic Resonance Spectrometry (EMR) and Circular Dichroism (CD) see Table 1.

The development of the JCAMP-DX series of Cheminformatics data standards.

| 1988 – first JCAMP-DX specification for Infrared Spectroscopy [1] |

| 1991 – JCAMP-CS specification [2] |

| 1991 – IUPAC JCAMP-DX-IR recommendation (for data collections including measurement recommendations) [3] |

| 1993 – JCAMP-DX-NMR 5.0 specification [4] |

| 1994 – JCAMP-DX-MS specification [5] |

| 1999 – IUPAC JCAMP-DX-NMR 5.01 specification [6] |

| 2001 – IUPAC JCAMP-DX-ion mobility specification [7] |

| 2001 – IUPAC JCAMP-DX for NMR pulse sequences [8] |

| 2002 – IUPAC JCAMP-DX-NMR 6.0 recommendation (widely circulated and adopted draft) [9] |

| 2006 – JCAMP-DX for EMR [10] |

| 2012 – IUPAC JCAMP-DX for CD [11] |

It was during this rapid development phase that it became clear that the interests of the JCAMP committee in standardizing data transfer protocols were substantially overlapping with that of the IUPAC Committee on Printed and Electronic Publications, who had published their own guidelines in this area. Steven Heller was chairing both organizations, saw the replication of effort, and proposed to transfer responsibility for the further development and maintenance of the JCAMP-DX series of standards to IUPAC. Thus in 1995 the JCAMP-DX formats and standards became the responsibility of IUPAC [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13].

The JCAMP-DX file format in brief

Basic file structure and labeled data records

The JCAMP-DX file format is record oriented with the advantage that each individual record length is unrestricted; one is not limited to the number of characters in the Title, for example. Each file consists of a number of generic and technique-specific “labeled-data-records” (LDRs). A record starts with a standardized “data-label” followed by a “data-set”. The data-label has the form ##label-name=. The label-name is the record name. “##” is called the data-label-flag and indicates that a new label is starting and the previous record has ended. “=” is the data-label-terminator. For example, ##XUNITS= is the data-label of the record defining the abscissa units. When data-labels are parsed, all spaces, dashes, slashes, and underlines are ignored, and all lower-case characters are converted to upper case. This means ##XUNITS= and ## x-units=, for example, are equivalent. Every JCAMP-DX file starts with ##TITLE= and ends, unsurprisingly, with ##END=.

In between the ##TITLE= and the ##END= are a variety of other LDRs, some of which are common to all JCAMP-DX file formats regardless of the data type they are representing (and yes ##DATATYPE= is also an LDR). This makes it far easier to write software to parse JCAMP-DX files, as there are many common elements which are shared between all the different JCAMP-DX standards.

Each different JCAMP-DX standard defines CORE LDRs that are the irreducible minimum metadata content that make that particular JCAMP-DX standard viable. Great lengths were taken to always make this section as small as possible. Table 2 provides an example JCAMP-DX infrared file with the CORE LDR’s highlighted in RED (bold) and the optional LDRs in BLUE (italic) for clarity. The standardized optional JCAMP-DX LDRs cover a multitude of areas of information about the spectra. Some are additional non-essential information about the dataset itself; others cover structured and unstructured notes about the dataset. There are defined LDRs which cover information about the sample that has been measured such as ##SAMPLE DESCRIPTION= or ##REFRACTIVE INDEX=. JCAMP-DX files can also contain sections for undefined comments using simply the LDR ##= (a label-less LDR) or $$ within a line such that the contents from there to the end of the line are not acted on.

Example of an IR data file.

| ##TITLE= o-eugenol |

| ##JCAMP-DX= 5.01 $$export from JSpecView |

| ##DATA TYPE= INFRARED SPECTRUM |

| ##DATA CLASS= XYDATA |

| ##ORIGIN= Dept of Chem, UWI, JAMAICA |

| ##OWNER= public domain |

| ##LONGDATE= 1997/07/01 09:24:00 |

| ##SPECTROMETER DATA SYSTEM= PERKIN-ELMER 1000 FT-IR |

| ##INSTRUMENTAL PARAMETERS= 4400.00,450.00 cm-1; 16 scans; mode ratio; apod strong |

| ##STATE= liquid |

| ##IUPAC NAME= 2-allyl-6-methoxyphenol |

| ##MOLFORM= C10 H12 O2 |

| ##BP= 271 |

| ##RESOLUTION= 2 |

| ##XUNITS= 1/CM |

| ##YUNITS= TRANSMITTANCE |

| ##XFACTOR= 3.93E-03 |

| ##YFACTOR= 9.40262357E-07 |

| ##FIRSTX= 470 |

| ##FIRSTY= 0.00520004 |

| ##LASTX= 4400 |

| ##NPOINTS= 3931 |

| ##XYDATA= (X++(Y…Y)) 119593E530R12K042n65l78n02q80J885K545o2j634K702r4r43J760J759O29K859A7942 124427B0990L048J89k891K263L362J288K325L237N97l14K891K828O91K043L865D8454 128753E1031K733M305J666K83L802M902J319L048N311J603n35K703K891N122M022I5934 133079I8416M431L991M336L174L362M493K766N813N844N374N122O630Q798O945A74114 137150A85238J0401q673m682m148m745l519l268k514k828l017l173m368m714o096A32353 |

| …… |

| 1119593H75220 $$checkpoint |

| ##END= |

As JCAMP-DX expanded into techniques other than infrared and Raman spectroscopy, starting with the JCAMP-DX NMR version 5.0, standard LDRs included a dot after the ## to be able to distinguish between global records used for all spectroscopic methods such as ##MOLFORM= for the molecular formula and LDRs used only for a specific technique such as ##.OBSERVE NUCLEUS= for the observed nucleus in NMR spectroscopy, or ##.IONIZATION MODE= in mass spectrometry, the label-name for the data-type specific records starts with a period “.”.

Finally, for organizations which want to use the IUPAC JCAMP-DX standard data formats and want to define their own internal private LDR terms, so-called user-defined data labels were introduced. These also start with ## but the third character is $ in order to identify them as private labels. Software that is parsing a file and encounters such a label and knows what it represents can parse the information contained in this LDR. Software from other sources that does not recognize the private LDR should move automatically on to the next label – it is important that it should not need to read these private records in order to be able to successfully process the data file. These ##$ private labels will be discussed more below.

Encoding data in a JCAMP-DX file

The method of encoding data in a JCAMP-DX file can be as simple as a table of numbers, however, as discussed briefly above, there is an ingenious substitution encoding scheme which can deliver enormous benefits in file size reduction without any loss of data resolution – something close to the heart of every regulator. This encoding system relies on substitution of numbers by ASCII characters. Table 3 gives the characters allowed in the compression.

Pseudo-digits for ASDF forms.

| 1. ASCII digits | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 2. Positive SQZ digits | @ | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I |

| 3. Negative SQZ digits | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | |

| 4. Positive DIF digits | % | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R |

| 5. Negative DIF digits | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | q | r | |

| 6. Positive DUP digits | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | s | |

File size reduction was achieved in a number of stages starting with the idea of replacing the numerical Y data point by ASCII characters representing whitespace, sign, and first character of a number, squeezing the numbers together (SQZ format known as ASCII Squeezed Difference Format (ASDF) and shown in the second and third rows in Table 3 – green). So as an example, the seven-byte ASCII Y-value “−76354” would be represented by five-byte “g6354”, small letter ‘g’ representing WHITESPACE MINUS 7.

The next step was to realize that the two Y-values next to one another are often quite similar in size. So, if instead of storing the complete number the file format stored only the difference between the two numbers so as to save additional characters. Thus, instead of storing “−76354 −76362” we would encode “g6354q” where the “pseudo-digit” q in line 5 of Table 2 shows that the second Y-value is 8 less than the previous number. This is called DIF.

The icing on the cake is when two Y-values next to each other in the table are the same. In Table 3 the final line 6 is the pseudo-digits for encoding duplication (DUP). Continuing our example to the next five data points, “ −76354 −76362 −76362 −76362 −76362 −76362 −76362” could be encoded “g6354q%%%%%” using DIF compression but just “g6354q%W” using a “DIFDUP” encoding, the most compressed encoding (and the one most commonly used to date).

The compression is amazingly successful. Using an example from the Harvard University Dataverse (this example uses the search https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/harvard?q=BetaPinene), shows the native JEOL file for BetaPinene_6782ug200uL_CDCl3_1H_400MHz_Jeol.jdf with a file size of 1081 KB which will reduce to 988 KB when gzipped. The equivalent JCAMP-DX file BetaPinene_6782ug200uL_CDCl3_1H_400MHz_JDX.jdx is only 313 and 147 KB when gzipped. This is only 13.6 % of the original JDF file size and 14.9 % relative to zipped original binary file.

JCAMP-DX files containing multiple data sets or real & imaginary paired data arrays

In the section above, the structure of a simple dataset was described. From the time of the first released JCAMP-DX standard v4.24, it has been possible to allow for multiple datasets being stored in a single compound data file in individual blocks for each dataset. The related BLOCK format not only allows for the collection of multiple datasets of the same data type but also a way of collecting various spectral types into a single file for easier archiving, for example, of all the data collected on a single sample. Each BLOCK is a self-contained unit that can be extracted as a single dataset. The individual BLOCKS containing separate datasets are enclosed by an envelope called a LINK block shown in outline in Table 4.

Example arrangement of a BLOCK file.

| ##TITLE= Compound file with 4 spectral records |

| ##JCAMP-DX= 5.0 |

| ##DATA TYPE= LINK |

| ##BLOCKS=4 |

| Block 1 -e.g. with an IR ##TITLE= ##BLOCK_ID=1 ---- ##END= $$end of BLOCK 1 |

| Block 2 -e.g., with an H NMR ##TITLE= ##BLOCK_ID=2---- ##END=$$end of BLOCK 2 |

| Block 3 -e.g., with a C NMR ##TITLE= ##BLOCK_ID=3 ---- ##END=$$end of BLOCK 3 |

| Block 4 -e.g., with a MS ##TITLE= ##BLOCK_ID=4 ---- ##END=$$end of BLOCK 4 |

| ##END= $$ end of file |

With the introduction of many hyphenated techniques to the analysts’ arsenal, storing sequences of data using the JCAMP-DX 4.24 BLOCKS structure became unwieldy, as each BLOCK needed to contain the entire header information for each BLOCK. With improvements introduced with JCAMP-DX 5.0, it was now possible to use the JCAMP-DX NTUPLES data structures, which could store the data in multiple PAGES and inherit the same header records.

Table 5 shows a simple JCAMP-DX NTUPLES example where the two pages are storing the real and imaginary parts of the NMR SPECTRUM. As is clear, there is only one set of header information. For a 2D-NMR experiment, an additional dimension would be added.

Example arrangement of an JCAMP-DX NTUPLES file showing private labels and comments.

| ##TITLE=1H_ns16 CDCl3 /opt/topspin3.5pl6/data/complat/nmr SG 16 | ||||

| ##JCAMPDX= 5.01 $$ Bruker NMR JCAMP-DX V2.0 | ||||

| ##DATA TYPE= NMR SPECTRUM | ||||

| ##DATA CLASS= NTUPLES | ||||

| ##ORIGIN= SG | ||||

| ##OWNER= SG | ||||

| ##LONG DATE= 2020/03/06 15:50:44+0000 | ||||

| ##.OBSERVE FREQUENCY= 400.13240078 | ||||

| ##.OBSERVE NUCLEUS= ˆ1H | ||||

| ##.ACQUISITION MODE= SIMULTANEOUS (DQD) | ||||

| ##.ACQUISITION SCHEME= undefined | ||||

| ##.AVERAGES= 16 | ||||

| ##.DIGITISER RES= 22 | ||||

| ##SPECTROMETER/DATA SYSTEM= spect | ||||

| ##.PULSE SEQUENCE= zg30 | ||||

| ##.SOLVENT NAME= CDCl3 | ||||

| ##.SHIFT REFERENCE= INTERNAL, CDCl3, 1, 15.91658 | ||||

| ##NTUPLES= NMR SPECTRUM | ||||

| ##VAR_NAME= | FREQUENCY, | SPECTRUM/REAL, | SPECTRUM/IMAG, | PAGE NUMBER |

| ##SYMBOL= | X, | R, | I, | N |

| ##VAR_TYPE= | INDEPENDENT, | DEPENDENT, | DEPENDENT, | PAGE |

| ##VAR_FORM= | AFFN, | ASDF, | ASDF, | AFFN |

| ##VAR_DIM= | 32768, | 32768, | 32768, | 2 |

| ##UNITS= | HZ, | ARBITRARY UNITS, | ARBITRARY UNITS, | |

| ##FIRST= | 5165.28925619835, | 269484, | 237339, | 1 |

| ##LAST= | 0, | 72857, | 2565148, | 2 |

| ##MIN= | 0, | 670883, | 288569244, | 1 |

| ##MAX= | 5165.28925619835, | 435392836, | 324306192, | 2 |

| ##FACTOR= | 0.157636929111556, | 1, | 1, | 1 |

| ##PAGE= N=1 | ||||

| ##DATA TABLE= (X++(R…R)), XYDATA | ||||

| 65535c733L34J602E08c96k330k01j059n5d34A334c7j021r50L23H35J510L592J247 | ||||

| 65517G184C281A48J48a937m692J364g59a64f3Oq04b37r40o84k44N30b57A792K207 | ||||

| 65498C999K159P13j726m0o94A456b601j37p15l297O9b817a271L58d02j683l26 | ||||

| 65481b411m66M05A245K265M60j881q04OK580M29A839H7a000b94l99j149a89B220 | ||||

| …… | ||||

| 26B289B17a617r97k139j214M86J317p21P23J049R92g25O5j68m20M07A994q28a569 | ||||

| 6c453R1f44B652j73G43P6 | ||||

| 0H19 | ||||

| $$ Imaginary data points | ||||

| ##PAGE= N=2 | ||||

| ##DATA TABLE= (X++(I…I)), XYDATA | ||||

| 65535B5256J026J239j303k503N10J304O31L315J296k386j364O17R21K713Q42K47 | ||||

| 65519C2361p44n060l114J444P47j637L079O131M93j661J21o67O28K75l00J286 | ||||

| 65503C3382J249J898J272R61m81j161l260j336n95k068j918J640K704m26K025 | ||||

| …… | ||||

| 17a2216O93J020j71n00K29M21J924m63k869K27K087L477K342q70k601M26J286 | ||||

| 0e558 | ||||

| ##END NTUPLES=NMR SPECTRUM | ||||

| ##END= | ||||

Extensions to the JCAMP-DX format

The use of ##$-prefixed private labels and $$-prefixed comments has found enormous utility both amongst academic programmers and the instrument vendors for two quite distinct purposes, deployment examples of which will be detailed below.

Vendor-specific extensions

Private labels and comments have been used extensively in NTUPLES file formats by NMR instrument manufacturers and software developers, where they add vendor-specific information related to instrument parameters and settings that are required for the JCAMP-DX file to describe the NMR experiment more fully. Indeed, some vendors have standardized their parsers to write out and read back all of their own vendor-specific metadata and parameters that are generated during an experiment. Table 6 is a small part of an excellent example of such use by Bruker Biospin for data generated by their instruments.

Example Bruker NMR JCAMP-DX file showing private labels and comments.

| $$ Bruker specific parameters |

| $$ -------------------------- |

| ##$DATPATH= <C:\Bruker\data\cga\nmr> |

| ##$EXPNO= 28 |

| ##$NAME= <cyclosporine-0813> |

| ##$PROCNO= 1 |

| ##$ACQT0= −6.36618283677107 |

| ##$AMP= (0…31) |

| 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 |

| 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 |

| ##$AMPCOIL= (0…19) |

| 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 |

| ##$ANAVPT= −1 |

| ##$AQSEQ= 0 |

| ##$AQ_mod= 3 |

| ##$AUNM= <au_sel180zg> |

| ##$AUTOPOS= <> |

| ………………. |

| $$ End of Bruker specific parameters |

| $$ --------------------------------- |

Structure-spectrum correlation extensions

From its inception in 1978, Molecular Design Limited, Inc. (MDL) established itself at the forefront of the field now known as cheminformatics and developed a MS-DOS based computer program called ChemBase. It was used to store chemical structures and metadata like the molecular mass (RMM), the molecular formula and the name of the compound and used a text-based format called the MDL Molfile. At its core was a table of the atoms with their 2D or 3D coordinates and a second table containing the bonds between the atoms. One issue though was that the Molfile format was copyrighted and not initially made publicly available.

In 1991, three years after the publication of the JCAMP-DX format for infrared data, a related recommendation for chemical structures was published, JCAMP-CS: A standard Exchange Format for Chemical Structure Information in Computer-Readable Form. This essentially contained the same information and was available for scientific and commercial purposes for anyone. Eventually, MDL Information Systems, Inc. (MDLI) published the CTfile/Molfile specifications and some other related formats [14]. Through this, the Molfile eventually became the de facto standard format for molecular structures, not only for MDLI, but for other software producers as well. This fulfilled the original purpose for the publication of JCAMP-CS, which never received widespread adoption.

Another example of the use of “user-defined” labels was designed to enable annotation and interaction between spectra and molecular graphic files particularly for use with J(S)mol The specifications have been included with all J(S)mol distributions since 2012 (and followed the merging of JSpecView code). They give a simple extension to the JCAMP-DX format using the data-labels, ##$MODELS= and ##$PEAKS=, to add 3D J(S)mol-readable models to the file and also associate spectral bands with specific IR and RAMAN vibrations, MS fragments, and NMR signals. The extensions can be used with all JCAMP-DX files, including BLOCK files (which can contain multiple spectra of diverse types as well as multiple models) Table 7.

Example of ##$MODELS- and ##$PEAKS= extensions for J(S)mol.

| ##$MODELS= |

| <Models> |

| <ModelData id=“acetophenone” type=“MOL”> |

| acetophenone |

| DSViewer 3D 0 |

| 17 17 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0999 V2000 |

| −1.6931 0.0078 0.0000 C 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 |

| …… |

| M END |

| </ModelData> |

| <ModelData id=“1” type=“XYZVIB” baseModel=“acetophenone” vibrationScale=“.1”> |

| 17 |

| 1 Energy: −1454.38826 Freq: 3199.35852 |

| C −1.693100 0.007800 0.000000 –0.000980 0.000120 0.000000 |

| … |

| 17 |

| 2 Energy: −1454.38826 Freq: 3191.02824 |

| C −1.693100 0.007800 0.000000 –0.000020 –0.000100 0.000000 |

| … |

| </ModelData> |

| </Models> |

| ##$PEAKS= |

| <Peaks type=“IR”> |

| <PeakData id=“1” title=“asymm stretch of aromatic CH group (∼3100 cm−1)” peakShape=“broad” model=“1.1” xMax=“3121” xMin=“3081” /> |

| <PeakData id=“2” title=“symm stretch of aromatic CH group (∼3085 cm−1)” peakShape=“broad” model=“1.2” xMax=“3101” xMin=“3071” /> |

| <PeakData id=“3” title=“asymm stretch of CH group (∼3060 cm−1)” peakShape=“broad” model=“1.3” xMax=“3077” xMin=“3047” /> |

| … |

| </Peaks> |

The added ##$MODELS records generally contain one Molfile (for NMR) or, for IR or RAMAN, a multi-model XYZ file with vibration information with an optionally associated Molfile that specifies bonding, or for MS a set of Molfiles, one for each fragment. The ##$PEAKS records simply indicate which bands on a spectrum correlate with which models (IR, RAMAN, MS) or model atoms (NMR) in the ##$MODELS record(s). Both records internally use a simplified XML-like format to differentiate and describe individual models and peaks.

Some examples using this specification are highlighted in the use of JCAMP-DX in teaching given below.

JCAMP-DX 6 and future developments

It was envisaged that n-D NMR and hyphenated spectroscopic techniques, such as GC-MS, would be covered with the release of Generic JCAMP-DX 6.0 standard and drafts of IUPAC Recommendations for these were prepared and circulated as early as 2002 [9, 13]. Developments in new XML file types for spectroscopy and analytical data in general that were more suited to meet the growing regulatory compliance needs of industrial customers meant that the IUPAC development team worked together with ASTM to produce a unified standard [15]. Unfortunately, this process dragged on for far too long to keep the instrument vendors on board and IUPAC eventually withdrew when the agreed procedure and timelines for completion of the work was subsequently rejected.

In the interim several NMR manufacturers implemented the 6.0 draft recommendations that had been circulated and were close to completion to meet the requirements of their customer bases and from both an instrument vendor and independent software supplier perspective these have become a de facto standard in NMR.

JCAMP-DX in teaching and research

By 2005, essentially all applications for the display and manipulation of spectroscopic data files for the techniques defined were capable of including JCAMP-DX files. One of the first freely available viewers for JCAMP-DX data files was released in 1997 by MDLI (then Symyx, then Accelrys, and now BIOVIA) as part of their Windows version of the browser plug-in Chime. This was based on code developed at The University of the West Indies, Jamaica. Up until 2005, when the development of the JCAMP-DX routines in Chime ceased, it was estimated that over 2 million copies of the free version had been downloaded from the MDL web site. The source code was never made available. Following a full rewrite of the code from C++ to Java, the source code for the JSpecView project was released on the SourceForge web site in March 2006 as Open Source. The code was later merged with the open-source project Jmol in 2012, which is automatically transpiled and released as both Java and JavaScript applications.

Many on-line resources have been created that make extensive use of the JCAMP-DX formats, including a number suitable for research and teaching purposes. This section will show a few examples from some of the leading groups in JCAMP-DX adoption where the JCAMP-DX plays a key role in different developments. Here use is often made of the capability to extend the JCAMP-DX using Private Label Data Records tailored to the new application under development.

JCAMP-DX in automated web-based walk-up spectral analysis

In 2002–3, a team of five undergraduates over the course of two summers working with one of us (RMH) in the Department of Chemistry at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minnesota, USA successfully built and installed the first real-time web interface for remote-access acquisition control and analysis using a Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer fitted with a 120-position BACS autosampler. The reconfigured Bruker system allows neophyte (second year) college students and undergraduate researchers essentially free, unsupervised 24/7 access to the instrument. Since then, it is estimated that over 60 000 spectra have been acquired, with fewer than 100 by users physically at the console (Fig. 2).

Automated off-site NMR data processing.

With the integration of JSpecView into Jmol and Jmol transpiling to JavaScript, the stage was set for a JavaScript version of JSpecView as well. The interface was configured to create JCAMP-DX files on demand using server-based Bruker command-line tools, passing the JDX files to the browser, where JSpecView-JS reads them and provides interactive spectral processing within a web page for both 1D and 2D spectra. The installation has been running without stop for close to 20 years with essentially no issues.

JCAMP-DX in automated online NMR prediction

With the advent of online services for the prediction of 1H and 13C spectra at Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL) in Lausanne, Switzerland, a collaboration arose that brought real-time spectral prediction into Jmol and JSpecView. Using the 2D drawing utility, JSME [16]. Bruno Bienfait and Peter Ertle …] or via direct 2D or 3D file model loading from PubChem or the NCI Computer Aided Drug Design (CADD) “Chemical Identity Resolver” service, it is now possible to quickly get predicted 1H or 13C spectra into JSpecView. The application interface in Lausanne receives a 3D MOL structure, queries the SPINUS server in Lisbon, Portugal [http://neural.dq.fct.unl.pt/spinus/] for a prediction, and returns a JSON structure containing an embedded simulated spectrum in JCAMP-DX format, along with full chemical shift and coupling information correlated to structure (One of the challenges in this project was that a different structure to the one used for the analysis is returned). Jmol uses its native SMILES processor to map all atoms, including H atoms, in the returned structure to their counterparts in the original 2D and 3D structures to allow interactive exploration of the structure-spectral relationships (Fig. 3).

![Fig. 3:

Interactive display of 2D and 3D structures, calculated 1H and 13C NMR spectra, and correlations using JSmol, JSME, and JSpecView at https://chemapps.stolaf.edu/jmol/jsmol/nmr_predict_HC.html: [ref. 17. Damiano Banfi and Luc Patiny].](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2021-2010/asset/graphic/j_pac-2021-2010_fig_003.jpg)

Interactive display of 2D and 3D structures, calculated 1H and 13C NMR spectra, and correlations using JSmol, JSME, and JSpecView at https://chemapps.stolaf.edu/jmol/jsmol/nmr_predict_HC.html: [ref. 17. Damiano Banfi and Luc Patiny].

NMRium is a joint project of Zakodium, a chemoinformatics company from Switzerland, and the DFG-funded IDNMR project. Together, they are developing a web-based visualizer and editor for 1D and 2D NMR spectra with data import functionality for JCAMP-DX NMR files. On the NMRium website, you can already test 1D and 2D NMR functionalities like peak picking, integration, assignment, and more, without installing software, completely in the browser! A teaching module is also available, where you can create your own exercises with 1D and 2D spectra for your students to elucidate the structure (Fig. 4).

![Fig. 4:

NMRIUM – NMR processing site [https://www.nmrium.org/] with drag and drop for JCAMP-DX files.](/document/doi/10.1515/pac-2021-2010/asset/graphic/j_pac-2021-2010_fig_004.jpg)

NMRIUM – NMR processing site [https://www.nmrium.org/] with drag and drop for JCAMP-DX files.

JCAMP-DX in circular dichroism

The PCDDB is a public repository that archives and freely distributes circular dichroism (CD) and synchrotron radiation CD (SRCD) spectral data and their associated experimental metadata (Fig. 5). It is a development of the Department of Biological Sciences, Institute of Structural and Molecular Biology, Birkbeck College, University of London and the School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, UK. The repository has around 700 spectra deposited and the ∼1000 Registered users are spread over 94 countries https://pcddb.cryst.bbk.ac.uk/.

The protein circular dichroism data bank (PCDDB) https://pcddb.cryst.bbk.ac.uk/.

JCAMP-DX in teaching structure – spectra relationships

When teaching spectroscopy one of the hardest lessons is the relationship between chemical structure and substructure elements and features observed in the different spectroscopic analyses. Again, using Private Label Data Records, it has been possible to generate an entire suite of examples with interactivity built in between the drawn chemical representation and the spectral display. A few examples are shown in the figures below. Fig. 6 shows an interactive display of a GC/MS chromatogram of a Synfuel manufactured from ethanol passed over a ZSM-5 heterogeneous catalyst for hydrocarbon isomerization. The static image doesn’t do it justice so try out the following link – http://wwwchem.uwimona.edu.jm/spectra/jsmol/demos/synfuelGCMS.html. Clicking on a peak in the GC trace loads the chemical structure as a Molfile in the left pane as well as updating the lower right-hand pane to show the respective Mass spectrum (Fig. 6).

Interactive GCMS displays. http://wwwchem.uwimona.edu.jm/spectra/jsmol/demos/synfuelGCMS.html.

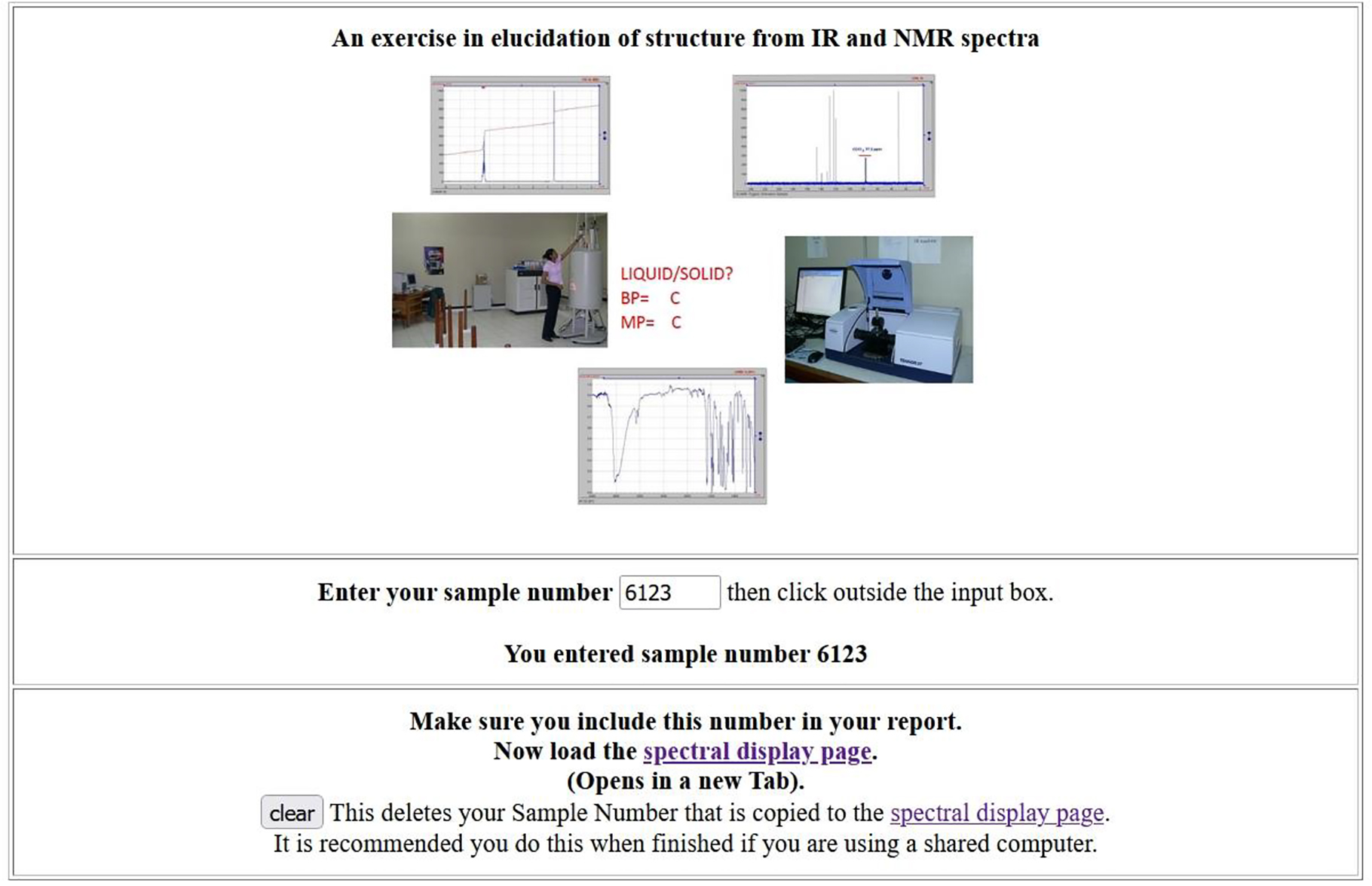

JCAMP-DX in teaching the identification of unknown substances

Traditionally, exercises in teaching the determination of unknown organic samples from spectra relied heavily on hard copies. To convert to a digital approach meant collecting spectroscopic data for around 150 compounds. To ensure that the data for each compound remained together, JCAMP-DX BLOCK files (each ∼250 Kb) were generated containing IR, H NMR, C NMR, and in some cases UV/Vis and MS as well. This began in the 1990s and when COVID-19 restrictions required closing the laboratory, an update was done to provide a virtual exercise that could be done with minimal remote supervision. The students were assigned unique numbers for each sample such that groups from other laboratory classes did not get numbers already in use. The JCAMP-DX BLOCK files contained IR, H NMR, C NMR, and in some cases UV/Vis and MS as well (See Figs. 7 and 8). http://wwwchem.uwimona.edu.jm/spectra/jsmol/demos/OrgUnknowns.html. Students are also pointed to resources such as ChemSpider (Fig. 9) where openly available JCAMP-DX formatted reference spectra are available for download.

Identifying unknowns from spectra. http://wwwchem.uwimona.edu.jm/spectra/jsmol/demos/OrgUnknowns.html.

Multiple spectroscopy types, data stored in JCAMP-DX formats, can be selected to assist the student in identifying the unknowns. http://wwwchem.uwimona.edu.jm/spectra/jsmol/demos/OrgUnknowns.html.

A search for information on ChemSpider returns several spectra in JCAMP-DX format. http://chemspider.com/.

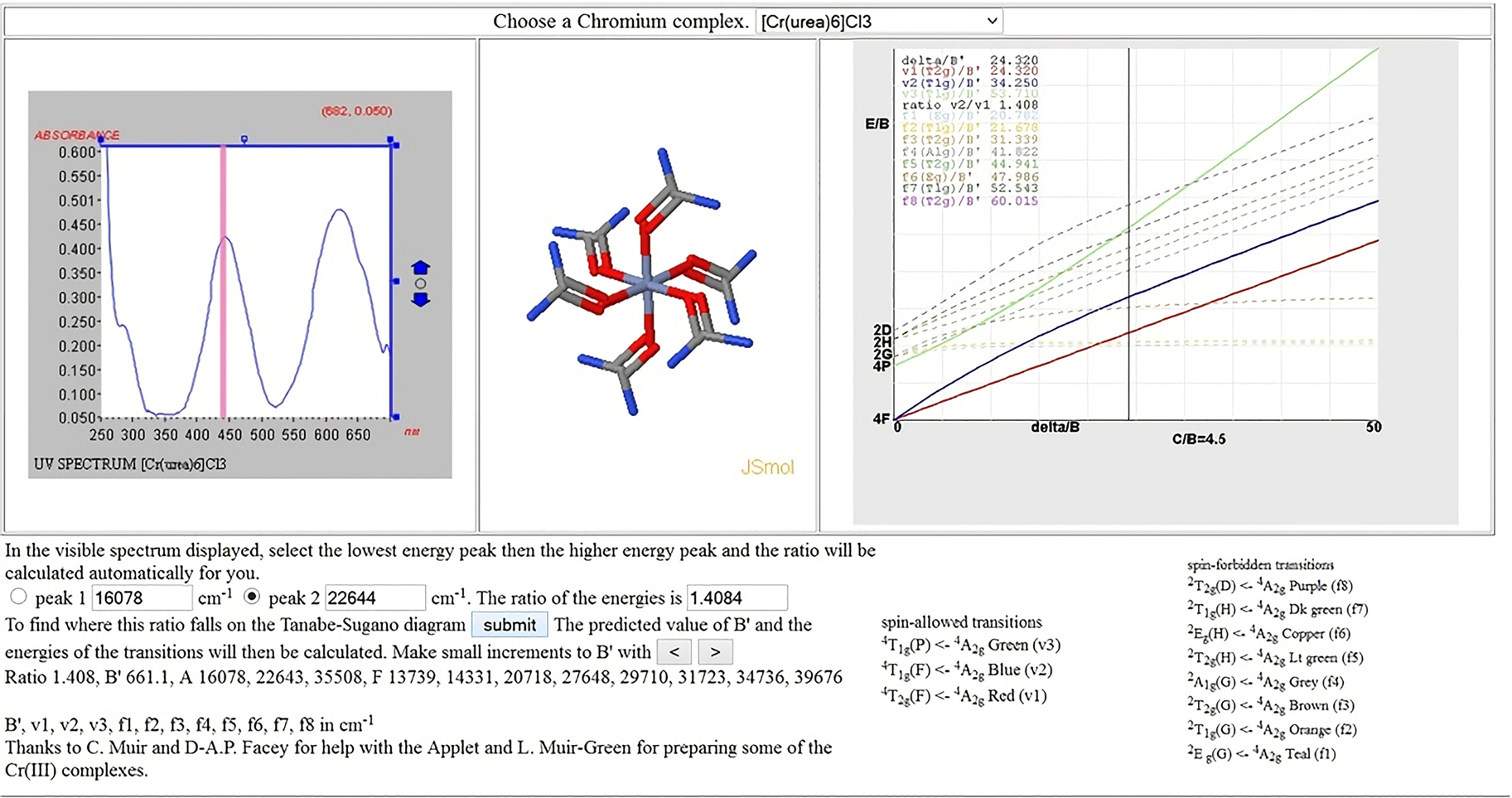

JCAMP-DX in teaching the interpretation of UV–vis spectra

This exercise has been a part of an Advanced Inorganic Chemistry Laboratory program at the UWI, Mona for many years (generally 50–80 students per year). Clicking on the 2 peaks in the visible spectrum passes that information to the Tanabe Sugano diagram on the right which then predicts the position of the 3rd spin-allowed transition, generally expected to be in the UV region and not seen since we give the students 1 cm plastic cells to use for the aqueous solutions (Fig. 10).

Interpretation of Cr(III) visible spectra. http://wwwchem.uwimona.edu.jm/lab_manuals/CrTSexptnu/Crexpt_TS.html.

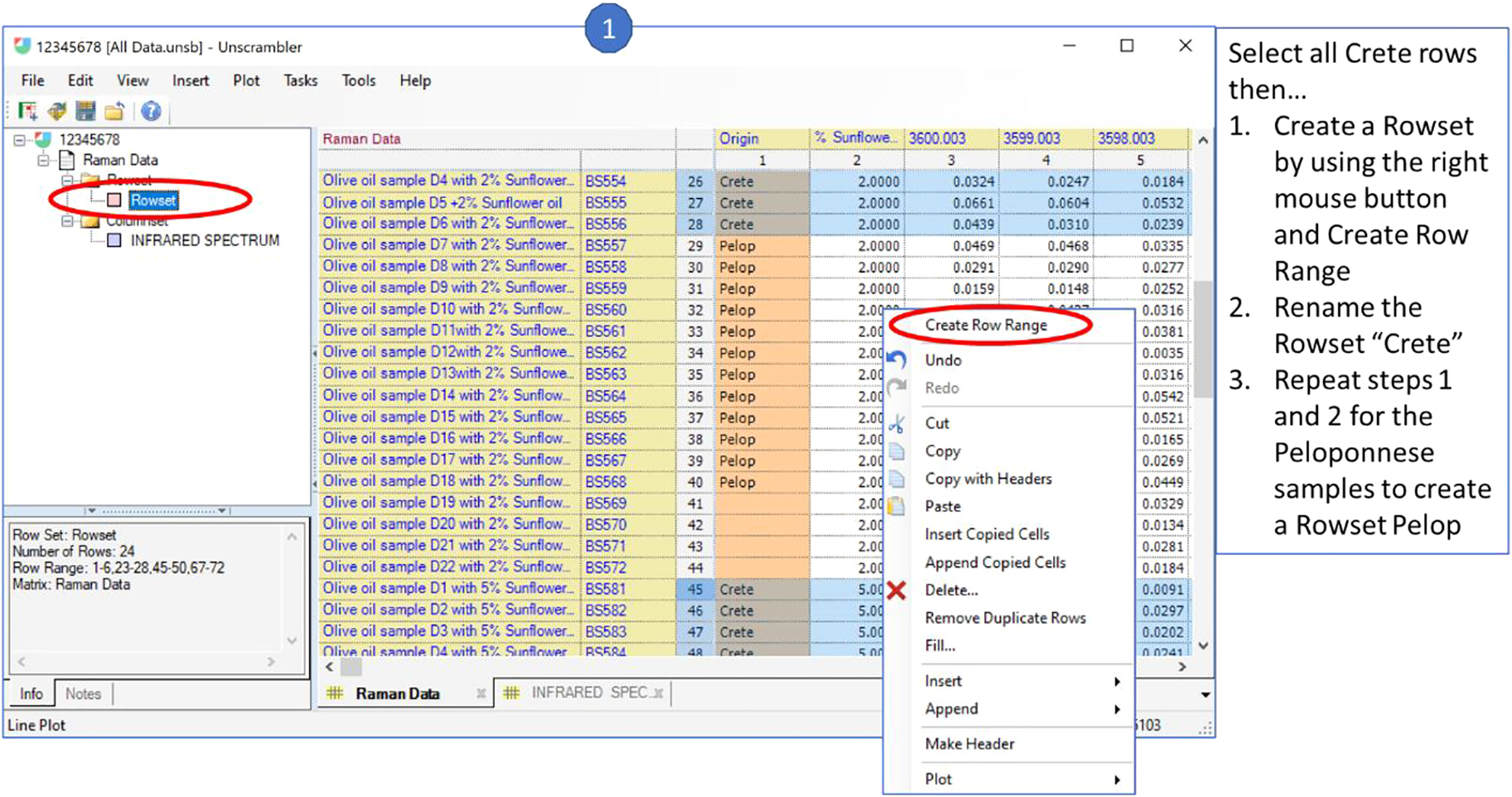

JCAMP-DX in teaching chemometrics

Over the years the use of the JCAMP-DX standard format has enabled the integration of the understanding of the importance of secure and robust data handling with other learning goals. In this example the JCAMP-DX formatted Raman spectra from a European Union sponsored research project into food authenticity have been integrated into training modules on chemometrics for the next generation of forensic spectroscopists. The students are provided with the data in JCAMP-DX format and a script which enables them to import the data into a new chemometrics package, carry out various data manipulation tasks and study the outcomes. In Fig. 11 they are annotating the JCAMP-DX spectra with metadata on the geographical origin of the samples which when plotted look something like Fig. 12 which stimulates discussion around the fluorescence signal in natural product data and how the chemometrics approach handles such spectroscopic information.

Data import into the unscrambler chemomteric data package from JCAMP-DX formatted spectra. https://www.aspentech.com/en/products/msc/aspen-unscrambler.

JCAMP-DX Raman spectra imported into chemometrics package as part of a teaching exercise. https://www.aspentech.com/en/products/msc/aspen-unscrambler.

Summary

A major objective of JCAMP-DX has been to enable routine capture of data at the source and to make it available for exchange, archiving, and entry into databases. In part, its success has been due to the following:

It was the first non-binary approach to spectroscopic data formats using only human readable ASCII characters

It was designed to be operating system and hardware independent

It covers the most important spectroscopic techniques: IR, Raman, MS, NMR, Ion Mobility, EMR, CD

It is accepted and used by most major instrument manufacturers

It is extendable, can contain unlimited metadata and open definitions allow further enhancements

It is non-proprietary, and self-documenting (i.e., is vendor independent and now maintained by IUPAC)

It can deliver good compression rates (important before cheap storage devices and higher internet bandwidths)

As of the 14 Mar 2022 an internet search of the LDR term “##JCAMP” found 584 000 separate documents that had allowed the search crawler to index their content.

The original purpose of the JCAMP-DX formats delivers many of the requirements of data format which is required to be deployed in a FAIR environment. FAIR and FAIRSpec is covered in greater detail in another article in this Special Edition and has much more stringent requirements than were originally requested by the stakeholders during the development of the JCAMP-DX series of standards. There has been some discussion as to whether JCAMP-DX could have a role in this, given that there would be a need for a significant number of additional metadata. It is worth noting that JCAMP-DX currently already delivers on:

easy findability with simple content harvesting by Finding Aids due to the ASCII structure.

interoperability.

structured, extractable metadata.

essentially lossless compression.

open, available software libraries.

infrastructure for the exchange of data.

supplemental to proprietary formats.

an additional representation of data.

ridiculously efficient compression.

inter-version compatibilities.

robust format for longevity.

Useful sites for finding JCAMP-DX spectra are NIST Webbook, ChemSpider, Spectral Zoo and the Open Spectra Database (OSDB). At the NIST Chemistry Webbook for example, once a researcher has displayed a particular spectrum they can download a copy in the JCAMP-DX format where a significant mount of metadata for that spectrum has been carefully added. In ChemSpider the spectrum viewer is JSpecView where it is not only possible to download the JCAMP-DX file but even select different storage formats such as XY data pairs allowing for direct import into other software programs such as Excel.

After over 33 years the JCAMP-DX standards are still very much alive and kicking and deployed on a spectrometer near you. Under the guardianship of the IUPAC Committee on Publications and Cheminformatics Electronic Data Standards (CPCDS) The future of JCAMP-DX standards could well lie in providing the structure in which much greater levels of standardization for metadata completeness can be implemented. There are also newer techniques that have been developed in recent years that would benefit from the availability of a standard exchange format in their specialism if the user communities and the instrument manufacturers would decide to move forward and request such a IUPAC standard.

Article note:

A collection of invited papers on Cheminformatics: Data and Standards.

Funding source: International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry

-

Research funding: This work was funded by International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry.

References

[1] R. S. McDonald, P. A. WilksJr. Appl. Spectrosc. 42, 151 (1988), https://doi.org/10.1366/0003702884428734.Search in Google Scholar

[2] J. Gasteiger, B. M. P. Hendriks, P. Hoever, C. Jochum, H. Somberg. Appl. Spectrosc. 45, 4 (1991), https://doi.org/10.1366/0003702914337894.Search in Google Scholar

[3] J. G. Grasselli. Pure Appl. Chem. 63, 1781 (1991), https://doi.org/10.1351/pac199163121781.Search in Google Scholar

[4] A. N. Davies, P. Lampen. Appl. Spectrosc. 47, 1093 (1993), https://doi.org/10.1366/0003702934067874.Search in Google Scholar

[5] P. Lampen, H. Hillig, A. N. Davies, M. Linscheid. Appl. Spectrosc. 48, 1545 (1994), https://doi.org/10.1366/0003702944027840.Search in Google Scholar

[6] P. Lampen, J. Lambert, R. J. Lancashire, R. S. McDonald, P. S. McIntyre, D. N. Rutledge, T. Fröhlich, A. N. Davies. Pure Appl. Chem. 71, 1549 (1999), https://doi.org/10.1351/pac199971081549.Search in Google Scholar

[7] J. I. Baumbach, A. N. Davies, P. Lampen, H. Schmidt. Pure Appl. Chem. 73, 1765 (2001), https://doi.org/10.1351/pac200173111765.Search in Google Scholar

[8] A. N. Davies, J. Lambert, R. J. Lancashire, P. Lampen, W. Conover, M. Frey, M. Grzonka, E. Williams, D. Meinhart. Pure Appl. Chem. 73, 1749 (2001), https://doi.org/10.1351/pac200173111749.Search in Google Scholar

[9] DRAFT, JCAMP-DX vs 6.0 with n-D NMR, draft of 2002. http://www.jcamp-dx.org/drafts/JCAMP6_2b%20Draft.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[10] R. Cammack, Y. Fann, R. J. Lancashire, J. P. Maher, P. S. McIntyre, R. Morse. Pure Appl. Chem. 78, 613 (2006), https://doi.org/10.1351/pac200678030613.Search in Google Scholar

[11] B. Woollett, D. Klose, R. Cammack, R. J. Janes, B. A. Wallace. Pure Appl. Chem. 84, 2171 (2012), https://doi.org/10.1351/PAC-REC-12-02-03.Search in Google Scholar

[12] J. G. Grasselli. Pure Appl. Chem. 59, 673 (1987), https://doi.org/10.1351/pac198759050673.Search in Google Scholar

[13] DRAFT, JCAMP-DX V.6.00 for CHROMATOGRAPHY and MASS SPECTROMETRY HYPHENATED METHODS. http://www.jcamp-dx.org/drafts/Chromatography%20&%20MS%20JCAMP-DX%206%20-%20Draft%2031%20May%202005.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[14] A. Dalby, J. G. Nourse, W. D. Hounshell, A. K. I. Gushurst, D. L. Grier, B. A. Leland, J. Laufer. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 32, 244 (1992), https://doi.org/10.1021/ci00007a012.Search in Google Scholar

[15] R. J. Lancashire, A. N. Davies. Chem. Int. 28, 10 (2006), https://doi.org/10.1515/ci.2006.28.1.10.Search in Google Scholar

[16] B. Bienfait, P. Ertl. J. Cheminf. 5, 24 (2013), https://doi.org/10.1186/1758-2946-5-24.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] D. Bianfi, L. Patiny. Chimia 62, 280 (2008), https://doi.org/10.2533/chimia.2008.280.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 IUPAC & De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Cheminformatics: data and standards a Pure and Applied Chemistry special issue

- Invited papers

- Ontologies4Chem: the landscape of ontologies in chemistry

- IUPAC specification for the FAIR management of spectroscopic data in chemistry (IUPAC FAIRSpec) – guiding principles

- Launching a materials informatics initiative for industrial applications in materials science, chemistry, and engineering

- Analysing a billion reactions with the RInChI

- Reaction SPL – extension of a public document markup standard to chemical reactions

- RSC CICAG Open Chemical Science meeting: integrating chemical data from two symposia and a series of workshops

- UDM (Unified Data Model) for chemical reactions – past, present and future

- An overview of the JCAMP-DX format

- Data format standards in analytical chemistry

- BioChemUDM: a unified data model for compounds and assays

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Editorial

- Cheminformatics: data and standards a Pure and Applied Chemistry special issue

- Invited papers

- Ontologies4Chem: the landscape of ontologies in chemistry

- IUPAC specification for the FAIR management of spectroscopic data in chemistry (IUPAC FAIRSpec) – guiding principles

- Launching a materials informatics initiative for industrial applications in materials science, chemistry, and engineering

- Analysing a billion reactions with the RInChI

- Reaction SPL – extension of a public document markup standard to chemical reactions

- RSC CICAG Open Chemical Science meeting: integrating chemical data from two symposia and a series of workshops

- UDM (Unified Data Model) for chemical reactions – past, present and future

- An overview of the JCAMP-DX format

- Data format standards in analytical chemistry

- BioChemUDM: a unified data model for compounds and assays