Abstract

Language aptitude is known to be a strong predictor of success in late second-language (L2) learning in instructional settings but is generally assumed to be irrelevant for native language (L1) acquisition. We investigated the relationship between language aptitude and L1 grammatical proficiency in the two studies reported here. Language aptitude was measured by means of a newly-developed test of grammatical sensitivity (Studies 1 and 2) and the Language Analysis subtest of the Pimsleur Language Aptitude Battery (Study 1), whereas grammatical proficiency was assessed by a grammaticality judgment task in Study 1 and a picture selection task in Study 2. The results of the two studies reveal a robust relationship between language aptitude and L1 grammatical proficiency that is remarkably consistent across different measures for both variables and appears to hold across the board for a variety of grammatical structures. These results fit well with the proposal that explicit learning may play an important role not only in adult L2 learning but also in L1 acquisition and raises questions about the validity of arguments for a fundamental difference between L1 and L2 acquisition based on the premise that only the latter is related to aptitude.

1 Introduction

Most language researchers assume that the acquisition of the grammar of one’s native language (L1) relies almost entirely on implicit learning mechanisms (DeKeyser et al. 2010; DeKeyser and Larson-Hall 2005; Ellis 1996; Kidd 2012; Kidd and Arciuli 2016; Montrul 2008; Ullman 2001). This is because the rules and principles underlying our linguistic knowledge are thought to be complex and highly abstract, yet children master them relatively quickly and apparently effortlessly and unintentionally: that is to say, they acquire the grammar of their language simply by engaging in communication – without trying to learn anything. Furthermore, the resulting knowledge is mostly tacit, and the rate of learning and ultimate attainment are often claimed to be independent of intelligence and explicit learning abilities (Bley-Vroman 1989; Chomsky 1965; DeKeyser 2000; Pinker 1999). This stands in sharp contrast to findings on adult second-language (L2) learning, where success has often been found to correlate with explicit instruction, intelligence and metalinguistic abilities (Carroll 1981; Carroll and Sapon 1959; de Graaff and Housen 2009; Li 2016; Norris and Ortega 2005; Sasaki 1996; Skehan 1986; Spada and Tomita 2010). These relationships are attributed to the fact that adult L2 learning, unlike L1 acquisition, is an effortful task that needs to rely to a considerable extent on explicit learning mechanisms (Bley-Vroman 1989; Carroll 1981; DeKeyser 2000).

However, there are several findings that are difficult to accommodate within the view of L1 acquisition outlined above. In the first place, children’s grammatical systems continue to evolve well into adolescence and even beyond. This was demonstrated by a recent large-scale study (Hartshorne et al. 2018) which found that native speakers’ performance on a task assessing their knowledge of some fairly basic grammatical structures continued to improve up to about age 30. Secondly, and possibly more importantly, there are considerable differences in the degree to which native speakers master the grammatical system of their language (Dąbrowska 2012, 2015, 2018, 2019; Farmer et al. 2012; Kidd et al. 2018). These differences have been shown to correlate with educational attainment, intelligence (IQ) and print exposure, as well as with language aptitude as measured using foreign language aptitude tests (Dąbrowska 2018; Dąbrowska and Street 2006; Street 2017; Street and Dąbrowska 2010).

The relationship between L1 grammar and (foreign) language aptitude is perhaps the most surprising. Measures of language aptitude such as the Modern Language Aptitude Test (MLAT) (Carroll and Sapon 1959) and the Pimsleur Language Aptitude Battery (PLAB) (Pimsleur 1966) were developed to predict L2 achievement in instructional settings, particularly at earlier stages of acquisition. Language aptitude as measured through these tests was believed to be irrelevant for first language acquisition. In fact, the purported lack of a relationship between aptitude and native language acquisition has been used to support the claim that L1 and L2 learning depend on fundamentally different mechanisms. For example, DeKeyser argues that

Children, of course, all learn their native dialect completely, regardless of their level of verbal ability (except in cases of a clear handicap), because they rely on language-specific mechanisms of implicit learning instead of on general mechanisms for explicit learning. If the implicit learning mechanisms used by the child are no longer available, then the adult must bring alternative, verbal-analytic problem-solving skills to the process of language acquisition in order to succeed, and these analytical verbal skills are characterized by strong individual differences. Therefore, the Fundamental Difference Hypothesis predicts that those adults who appear to be successful at learning a second language will necessarily have a high level of verbal ability. (DeKeyser 2000: 500–501)

Similarly, Carroll, the developer of the MLAT, maintained that aptitude is relevant in instructional settings where learners make a “deliberate effort to learn a foreign language” (1981: 83) – and, by implication, not in L1 acquisition, while Dörnyei and Skehan (2003: 600) argue that aptitude “presupposes a requirement that there is a focus on form” which, they assume, is not the case in L1 acquisition.

Performance on language aptitude tests is strongly associated with IQ, as shown for instance in a meta-analysis conducted by Li (2016), which reported a mean correlation of 0.50 between these two variables. For the MLAT, the correlation was even stronger (0.64). In spite of this, aptitude and IQ are regarded as distinct (though related) abilities. This is partly because aptitude has been found to predict foreign language attainment above and beyond IQ (see Li 2015, 2016).

It is important to note in this connection that language aptitude is not a unitary characteristic but rather a set of distinct abilities. According to Carroll’s (1964, 1990 influential model, aptitude comprises at least four distinct abilities: phonetic coding ability (which is most relevant for the acquisition of phonological structure), rote memory (important for learning vocabulary and collocations), and grammatical sensitivity and inductive language learning ability (most important for the acquisition of grammar). Because of this, most aptitude tests consist of a number of subtests measuring specific aspects of aptitude.

While the efficacy of aptitude tests in predicting foreign language learning in instructional settings is widely accepted, there is also evidence that aptitude can predict success in language learning in naturalistic settings (Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam 2008; DeKeyser 2000; Granena and Long 2013). In fact, it has been hypothesized that the relationship may be even stronger in naturalistic settings than in typical instructional scenarios because, in the former, learners must discover the rules of the language without the help of a teacher (cf. DeKeyser 2000; McLaughlin 1990). Along the same lines, and even more intriguingly, there is also some evidence that language aptitude correlates with the rate of native language acquisition and native language ultimate attainment. Thus, Skehan and Ducroquet (1988) found significant relationships, some as high as 0.52, between various measures of language development taken during early L1 learning (between 15 and 60 months) and the results of various foreign language aptitude tests administered much later, at age 14, while Sparks et al. (2009) showed even stronger relationships (from 0.61 to 0.77) between various measures of L1 literacy measured in grades 1–5 and language aptitude assessed in grade 9. Similarly, Dąbrowska (2018) reported a significant correlation (r = 0.46) between grammatical comprehension and the Language Analysis subtest of the PLAB, which measures aptitude to infer grammatical rules, in adult native speakers of English.

Findings suggesting that the acquisition of the grammatical system of the native language may depend (at least to some extent) on language aptitude are of considerable theoretical interest, as they invite the conclusion that the differences between L1 learners and late L2 learners may not be as fundamental as it is often assumed. In addition, the effects of language aptitude on L1 grammatical proficiency also point towards the idea that first language acquisition may depend to some extent on explicit learning mechanisms (cf. Dąbrowska 2010; Llompart and Dąbrowska 2020). The purpose of this paper is to explore this relationship in more detail. We report the results of two studies that examined the relationship between (foreign) language aptitude and grammatical proficiency in adult native speakers. We use two different measures of grammatical proficiency (a grammaticality judgment task and a picture selection task) and two measures of language aptitude (the Language Analysis subtest of the PLAB and a new test modeled on the Words in Sentences subtest of the MLAT).

In Language Analysis, participants are presented with some vocabulary and simple sentences in an unknown language and their English translations and are asked to infer the structure of new sentences in the language. In Words in Sentences, participants are asked to find correspondences in grammatical function between words presented in sentence pairs. The two tests were designed to measure inductive learning ability and grammatical sensitivity, respectively. Note that, while both tests involve verbal stimuli, the difficulties associated with them do not stem from the comprehension of the stimuli themselves, which are for the most part simple sentences with common vocabulary and hence are unlikely to be problematic for native speakers. Instead, the tasks are challenging because they involve making (explicit) inferences about the internal structure of the verbal stimuli and thus require a high level of metalinguistic awareness (as opposed to sheer linguistic abilities). As mentioned above, inductive learning ability and grammatical sensitivity are most relevant for learning grammar, and in fact, their predictive power for performance on L2 grammar tasks is comparable to that of the full aptitude tests (Li 2016). Although in Carroll’s (1964) framework they are presented as distinct components of language aptitude, other researchers (e.g., Li 2015, 2016; Skehan 2002) have proposed that Language Analysis and Words in Sentences examine the same underlying construct, namely, language analytic ability.

2 Study 1

To our knowledge, Dąbrowska (2018) is the only published study so far to report a relationship between grammatical proficiency and (foreign) language aptitude in adult L1 speakers. Importantly, this study used a picture selection task involving a variety of grammatical structures (e.g., passives and subject and object clefts) as a test of participants’ grammatical comprehension. Most studies of grammatical knowledge in L2 speakers, however, use grammaticality judgment tasks (GJT; see Plonsky et al. 2020). One reason why GJTs are commonplace in L2 research is that they allow for the testing of a wider range of grammatical structures than picture selection or other comprehension tasks. Crucially, test items in GJTs can include the manipulation of grammatical morphemes which are semantically redundant (e.g., agreement markers). Such elements, which Dąbrowska et al. (2020) call “decorative” (as opposed to “functional”) grammar, arguably tap into different aspects of linguistic knowledge from comprehension tasks (Pili-Moss et al. 2020; Wulfeck 1988). Since “decorative” grammar is known to be particularly difficult for L2 learners (Dąbrowska et al. 2020; Hopp 2010, 2013; McDonald 2006; White 2003), GJT tasks are most often used with this population. However, GJTs have also become increasingly popular in L1 research, where even children as young as 4 have been tested using an adapted procedure (Ambridge 2012, 2014). Furthermore, even if some concerns have been voiced over the years about the validity and reliability of GJTs (e.g., Birdsong 1989; Orfitelli and Polinsky 2017; Tabatabaei and Deghani 2012) many researchers still believe that GJTs constitute a more direct reflection of grammatical competence than comprehension tasks (cf. Linebarger et al. 1983; van der Lely et al. 2011; see also Devitt 2006).

For all these reasons, in Study 1 we investigate whether the relationship between grammatical proficiency and language aptitude observed in Dąbrowska (2018) also holds for performance on a grammaticality judgment task.

2.1 Methods

2.1.1 Participants

Eighty native speakers of English (53 females; mean age = 23.96, SD = 3.99) took part in Study 1 in exchange for a small payment. Participants were recruited through the online recruitment platform Prolific (Palan and Schitter 2018). Using Prolific’s prescreening tools, we selected participants who were monolingual speakers of English and currently lived in the UK and who were between 18 and 30 years old. Additionally, participants were set to vary in their highest academic qualification in the following way: 20 participants had GCSEs[1] as their highest qualification, 20 had completed their A-levels, 20 had an undergraduate degree (i.e., Bachelor’s degree) and 20 were in possession of graduate degree (i.e., Master’s degree or PhD). This was done in order to have a heterogeneous sample in terms of education which could better approximate the characteristics of the whole population. Participants without formal qualifications were not included, however, because the grammar task had to be administered online and was expected to be relatively difficult. All participants filled in a background questionnaire in which they provided basic demographic information and gave their informed consent to participate in the study and to their data being collected. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.1.2 Materials and procedure

Study 1 consisted of two language aptitude tasks and one task measuring grammatical proficiency. All tasks were devised using the Gorilla Experiment Builder (gorilla.sc; Anwyl-Irvine et al. 2020) and administered remotely. Participants were instructed to access the study from a desktop or laptop computer equipped with a physical keyboard and either headphones or an external speaker. The three tasks included in the study are described below in the order in which they were presented to participants. The entire testing session took between 45 and 60 min to complete.

2.1.2.1 Language analysis

This task is a computerized adaptation of the subtest of the PLAB (Pimsleur 1966) that measures inductive learning ability. In Language Analysis, participants are presented with a list of words and short sentences in an unknown language followed by their English translations and are prompted to use these correspondences to infer the grammatical rules of the foreign language. An example extracted from the PLAB sample items (Pimsleur 1966) is provided in the Supplementary Materials. On each trial, an English sentence was presented in writing and participants were asked to choose between 4 possible translations into the unknown language by clicking on one of four response boxes in which the translations appeared. The reference list of words and sentences and their English translations remained visible throughout the task. After reading the instructions, participants were given a practice trial followed by feedback and proceeded to take part in the actual test, which contained 15 trials. The entire task took 8–10 min to complete.

2.1.2.2 Sentence pairs

Sentence Pairs is a grammatical sensitivity test inspired by the Words in Sentences subtest from MLAT (Carroll and Sapon 1959). The MLAT is a secure test that is only available to government agencies, licensed clinical psychologists and a few other groups that the Language Learning and Testing Foundation deems competent to administer the test. Specifically, the test is not available to individual researchers. Therefore, we developed our own version of the Words in Sentences subtest, Sentence Pairs, with the aim of making the test freely available to the research community. The entire test, including the instructions, is available in the Supplementary Materials. Hence, like Words in Sentences, Sentence Pairs measures awareness of the grammatical functions of individual elements in a sentence and the syntactic patterning of elements across sentences without using grammatical terminology such as “subject” or “verb” (Carroll 1973).

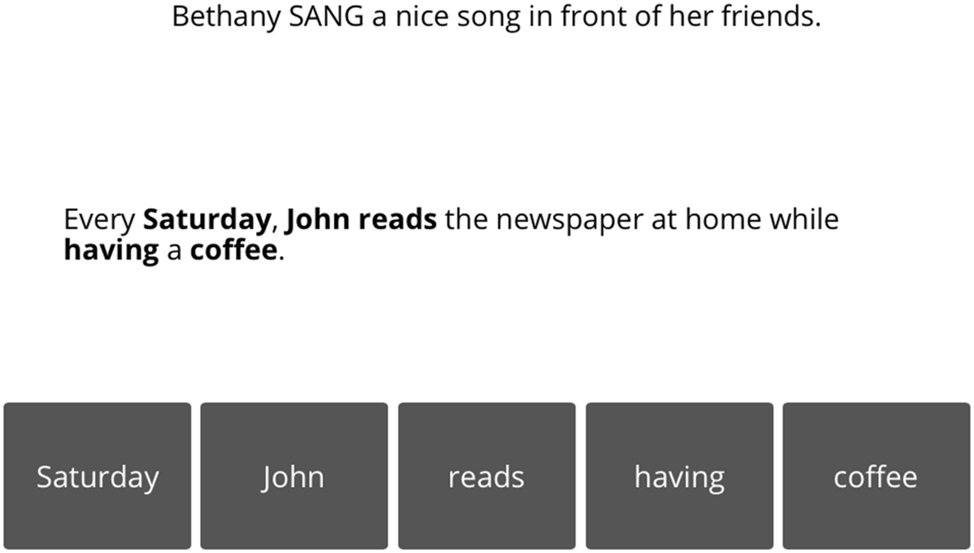

Our version of the test contained 32 items, each consisting of two sentences. The first sentence contained a word in capitals. In the second sentence, five words were highlighted, and the participant’s task was to select the highlighted word that had the same grammatical function in the second sentence as the word in capitals in the first sentence. Immediately below each of the highlighted words was a black square labeled with the same word. Participants responded by clicking on the appropriate square (see Figure 1). Before the start of the test, four practice trials were provided. In the practice trials, participants were given visual feedback on their responses by means of either a green tick (i.e., correct) or a red cross (i.e., incorrect). In addition, whenever they clicked on an incorrect box, they were allowed to choose another response until they selected the correct one. In the 32 experimental trials that followed, no feedback was provided and the next trial began as soon as the participant entered a response. The task took about 10–12 min to complete.

Example of a trial in the Sentence Pairs test. The correct answer for this trial is reads.

2.1.2.3 Auditory grammaticality judgment task

English grammatical proficiency was assessed through an auditory grammaticality judgment task (henceforth GJT). An auditory version of the GJT was selected because it has been argued that auditory GJTs measure implicit language knowledge more directly than GJTs in the written modality (Kim and Nam 2017, as cited in Plonsky et al. 2020). A total of 180 English sentences were used (half grammatical, half ungrammatical). Following a pilot study, we chose 8 types of items that were relatively challenging even for native speakers. There were 20 items for each structure (10 grammatical and 10 ungrammatical). In addition, there were 20 control items (10 grammatical and 10 ungrammatical) in which the ungrammatical sentences contained very clear violations which we expected all native speakers to be able to identify. Table 1 provides examples of ungrammatical items for each structure. A complete list of all items used in the GJT is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Examples of ungrammatical items for each of the 9 structure types in the GJT task.

| Category | Example of ungrammatical item |

|---|---|

| Control | Many kids has problems with adjusting to high school. |

| Double Tense | Who did your sister invited to the party? |

| Stranded Wh- Questions | What did your dad say what his favorite steakhouse was? |

| Embedded questions | John has always wondered what does papaya taste like. |

| Subcategorization | My friends and I really enjoy to play football. |

| that Trace | What did she claim that was problematic? |

| Agreement Attraction | The legs of the dining-hall table needs to be repaired. |

| Object Agreement | Which animals have the farmer fed? |

| Participial Clauses | Sitting on a bench, his watch was stolen. |

Items were randomized with the constraints that no more than two items belonging to the same structure could appear in a row and no more than three trials in a row required the same response (i.e., grammatical/ungrammatical). Because our study focuses on individual differences, all participants responded to the items in the same order, as this ensured that any order effects would be the same for all participants. All sentences were recorded by a female native speaker of English who attempted to keep the intonational patterns and speech rate as constant across items as possible. The audio files were then checked and trimmed where necessary to eliminate silent stretches at the onset and offset of the stimuli.

Each trial began with a fixation cross presented for 800 ms. Then, a “Play” button and the prompt “Click on Play to listen to the sentence” appeared on the top of the screen. At the same time, two response buttons appeared on the lower part of the screen, one green and with a white tick on it to the left and one red and with a white cross on it to the right. Participants were instructed to click on Play to listen to the sentence and then click either on the green button if they considered the sentence to be correct or on the red button if they considered it to be incorrect.

Before the start, participants completed two practice trials, one with a correct sentence and one with a clearly incorrect sentence. These were presented in writing rather than auditorily and participants received feedback on their responses. While participants were not explicitly instructed to attend to grammar, the examples in the practice trials, and in particular the ungrammatical sentence, targeted grammar in an obvious way. After completing the practice trials, participants were given the opportunity to test their audio system and to adjust the volume to a comfortable listening level before they started with the experimental trials. Participants were encouraged to take a short break every 60 trials (i.e., after trials 60 and 120). The entire task took approximately 25 min to complete.

2.2 Results

2.2.1 Data processing

For GJT data, trimming procedures were applied to eliminate outliers and invalid responses. First, only responses for trials in which participants had played the audios were included in the analyses. This led to the exclusion of 194 trials (out of 14,400, i.e. 1.35 % of the dataset). One participant had very few remaining responses (i.e., 23), indicating that s/he responded to the vast majority of trials without listening to the sentences. For this reason, all data from this participant were excluded. Secondly, trials with reaction times (RTs) longer than 3 Median Absolute Deviations (Leys et al. 2013) from the median of the entire dataset were removed from the analyses. This was done because the participants were tested remotely, and very long RTs could be indicative of them being distracted and not engaging with the task. No RTs were shorter than 3 Median Absolute Deviations from the median. This procedure established an upper RT limit of 8.45 s and resulted in the exclusion of 1,385 trials (9.62 % of all trials); thus, the total number of excluded trials was 1,579 (10.97 %). Note that this time limit still allowed plenty of time for participants to respond, as the main duration of the auditory-presented sentences was 3.33 s (SD = 1.01).

Subsequently, to obtain individual scores for the GJT, mean proportions of correct responses and d′ scores were computed for each participant. d′ is a measure derived from signal-detection theory (e.g., MacMillan and Creelman 2005) which takes individual participants’ response bias into account, and is computed by comparing the likelihood of a participant responding ‘correct’ when the stimulus is grammatical (the hit rate) and the likelihood of the same response when the sentence contains a grammatical error (the false alarm rate). Because of this, d′ scores provide a more sensitive measure of how well a participant is able to distinguish between grammatical and ungrammatical items than individual accuracy measures based on simple proportions of correct responses (Huang and Ferreira 2020). Individual d′ scores were obtained by subtracting the z-transformed false alarm rate from the z-transformed hit rate for each participant. The higher the d′ score, the better a participant is able to discriminate between grammatical and ungrammatical sentences. For Language Analysis and Sentence Pairs, individual scores were obtained by extracting the proportion of correct responses by participant by task. Split half reliabilities for the three tasks in Study 1 were calculated using the splithalf() function of the splithalf package (Version 0.7.2; Parsons 2021) in R (Version 4.1.1, R Core Team 2017). Using 5,000 random splits, the Spearman-Brown corrected reliability estimate for the GJT was 0.82 (95 % CI [0.74, 0.87]). The reliability estimates for Language Analysis and Sentence Pairs were 0.78 (95 % CI [0.7, 0.84]) and 0.86 (95 % CI [0.81, 0.9]), respectively.

2.2.2 General analysis

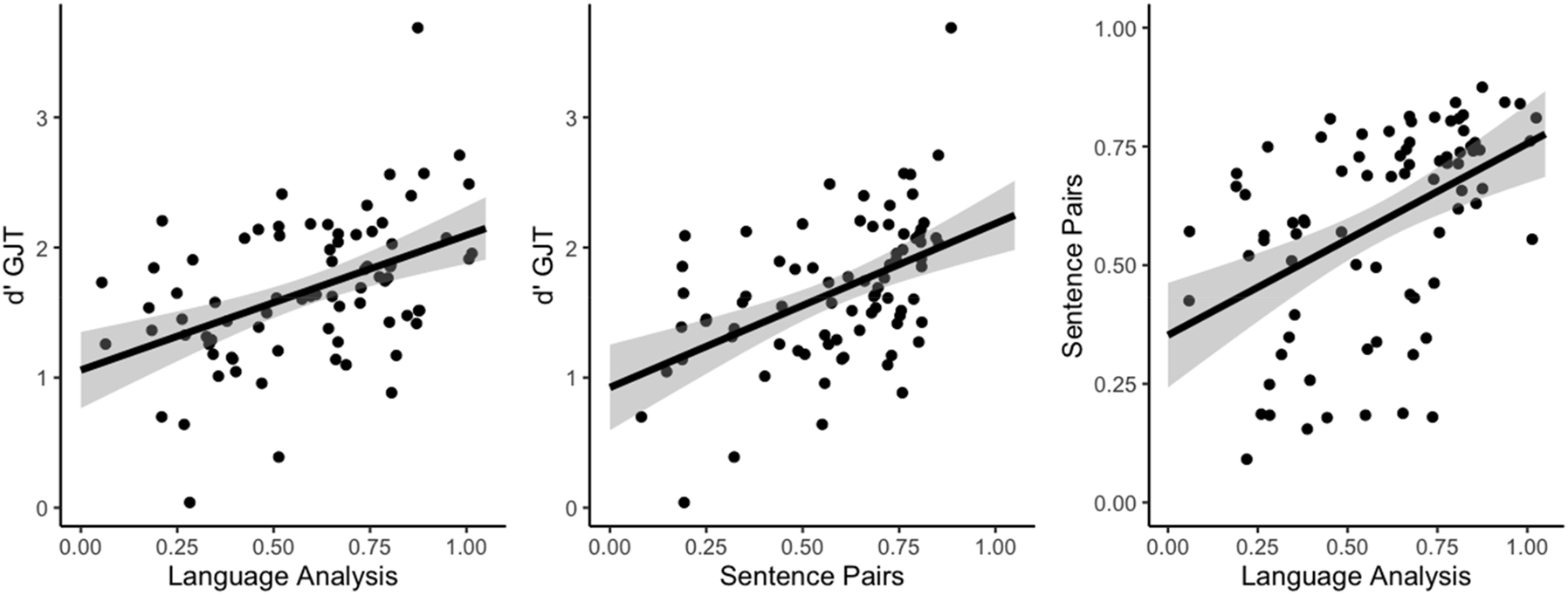

All datasets analyzed in this article and the code and materials necessary to reproduce the analyses reported are available at https://osf.io/qdkuh/. Table 2 shows descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for percentages of correct responses for grammatical and ungrammatical items in the GJT, d′ scores in the GJT, and percentages of correct responses in Language Analysis and Sentence Pairs for all participants pooled together and separately for the four education levels examined. So as to get a first impression of the relationship between native grammatical proficiency and language aptitude, as well as between the two language aptitude tasks, simple correlations were computed between all 3 measures. For the GJT, d′ scores were used and, for the two aptitude tasks, scores were entered as the proportion of correct responses. Results showed medium-to-large correlations (see Field et al. 2012) between Language Analysis and d′ scores for the GJT (r(77) = 0.45, p < 0.001) and between Sentence Pairs and d′ scores for the GJT (r(77) = 0.48, p < 0.001), as well as between the two aptitude measures (r(77) = 0.47, p < 0.001). Scatterplots outlining these relationships are provided in Figure 2.[2]

Mean percentages correct and standard deviations (in parentheses) for each task overall and for each education group separately. For the GJT, percentages for grammatical and ungrammatical items are presented separately and d′ scores are also provided.

| Task | Overall | GCSE | A-levels | Undergraduate degree | Graduate degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GJT grammatical | 88.8 % (9.4) | 88.4 % (5.8) | 88.8 % (8.9) | 89.7 % (5.9) | 88.3 % (14.6) |

| GJT ungrammatical | 63 % (13.5) | 58.9 % (15.1) | 60.4 % (9.4) | 65.3 % (13.2) | 67.7 % (14.6) |

| GJT d′ scores | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.6 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.6) |

| Language Analysis | 58.8 % (24.3) | 53.7 % (22.7) | 49.7 % (28.2) | 64.2 % (20.8) | 68 % (21.7) |

| Sentence Pairs | 59 % (21) | 53.9 % (20.1) | 60 % (20.8) | 58.4 % (23.3) | 63.6 % (20.2) |

Scatterplots of individual mean proportion of correct responses for Language Analysis and d′ scores for the GJT (left), mean proportion of correct responses for Sentence Pairs and d′ scores for the GJT (center) and mean proportion of correct responses for Language Analysis and Sentence Pairs (right) in Study 1.

A regression analysis was then conducted to statistically test whether aptitude predicted native speakers’ overall performance (i.e., for both grammatical and ungrammatical items) in the GJT. Education and item grammaticality were also included as predictors to assess their effects on response accuracy and to test whether the potential effects of aptitude interacted with these factors. GJT trial-by-trial data were submitted to a generalized linear mixed-effects model with a logit linking function (lme4 package 1.1–23, Bates et al. 2015) with Response (0 = incorrect, 1 = correct) as the categorical dependent variable. The independent variables of interest were Language Aptitude, Education (secondary education, A-levels, undergraduate degree, graduate degree) and Grammaticality (grammatical/ungrammatical). For Language Aptitude, a composite measure was obtained combining individual scores for Language Analysis and Sentence Pairs based on the premises that i) the scores for the two tasks were correlated, ii) the two tasks are considered by some L2 researchers (e.g., Li 2015, 2016; Skehan 2002) to tap into the same underlying construct, namely language analytic ability, and iii) a combined measure was desirable to avoid predictor collinearity in the model. The composite measure was a weighted average of the two aptitude tests, where Sentence Pairs was given a weight of 0.67 and Language Analysis was weighted 0.33. This was motivated by the fact that Sentence Pairs had about twice as many items as Language Analysis and, this way, every item in each of the two tasks was given approximately the same weight in the computation of the combined score. The resulting weighted averages were centered and scaled using the scale() function in R. Education was contrast coded so that GCSE was coded as −1.5, A-levels as −0.5, undergraduate degree as 0.5 and graduate degree as 1.5. Grammaticality was also contrast coded with ungrammatical as −0.5 and grammatical as 0.5. Note that these procedures have the advantage that, when all predictors are centered on zero, the effects (and their interactions) can be interpreted as main effects, similarly to traditional ANOVA. That is, effects can be interpreted relative to the grand mean rather than to a particular combination of factor levels (see Llompart and Reinisch 2017, 2020, for a similar approach).

After recoding, the model included Language Aptitude, Education, Grammaticality and their two-way and three-way interactions as predictors. With regard to random effects, random intercepts for Participants and Items were included as well as random slopes for Grammaticality over Participants and Aptitude over Items. These slopes were included because they improved the model’s fit as assessed through log-likelihood ratio tests (Grammaticality over Participants: χ2(2) = 392.7, p < 0.001; Aptitude over Items: χ2(2) = 13.8, p < 0.001). Random slopes for Language Aptitude over Participants and for Education over Items were not included because they did not significantly improve the model’s fit (Language Aptitude over Participants: χ2(2) = 5.61, p = 0.06; Education over Items: χ2(2) = 0.05, p = 0.98). The model revealed significant effects of Language Aptitude (b = 0.43; z = 6.28; p < 0.001) and Grammaticality (b = 2.03; z = 6.47; p < 0.001). The effect of Education (b = 0.07; z = 1.32; p = 0.19) was not significant and neither were any of the two-way interactions or the three-way interaction between Aptitude, Grammaticality and Education (all p > 0.15).[3] The model’s marginal and conditional pseudo-R2 values as obtained by means of the r.squaredGLMM() function (MuMIn package 1.43.17, Barton 2009) were 0.16 and 0.61, respectively. The results of the model indicate that participants were more accurate in the GJT with grammatical items than with ungrammatical items, and that language aptitude scores predicted performance in the GJT: the higher the aptitude scores, the more accurate listeners were when judging the grammaticality of auditory sentences. Interestingly, this relationship was not modulated by the grammaticality of the sentences nor the educational attainment of the listener. In addition, education did not significantly predict scores in the GJT, although there was a tendency in the expected direction.

2.2.3 Analysis by structure

Building on the significant effect of Language Aptitude in the analysis above, additional analyses were conducted to assess accuracy differences between the grammatical structures probed in the GJT, and to examine whether there were differences in how well aptitude predicted performance with the different structures. Table 3 reports mean percentages correct and mean d′ scores for each structure. Information about simple correlations between performance on the individual structures and the composite Language Aptitude measure can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Mean percentages correct, mean d′ scores and the corresponding standard deviations for the nine grammatical structures examined in the grammaticality judgment task.

| Structure | Mean (%) | SD | Mean d′ score | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Sentences | 90.4 | 9.0 | 2.6 | 0.6 |

| Agreement Attraction | 68.9 | 15.2 | 1.2 | 1.0 |

| Double Tense | 88.7 | 11.0 | 2.5 | 0.8 |

| Object Agreement | 66.9 | 12.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| Participial Clauses | 59.8 | 14.5 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| Stranded Wh- Quest. | 86.2 | 14.3 | 2.3 | 1.0 |

| Subcategorization | 76.0 | 12.3 | 1.6 | 0.7 |

| That Trace | 69.2 | 11.6 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| Embedded Questions | 76.4 | 12.2 | 1.7 | 0.7 |

Table 3 first confirms that, as expected, participants were quite accurate with the control items. This indicates that they understood the task and were cooperative at the time of testing. In addition, the table shows clear differences between structures in terms of accuracy: accuracies for Double Tense and Stranded Wh- Questions were almost as high as those for the control items, while accuracies for that Trace, Agreement Attraction, Participial Clauses and Object Agreement were considerably lower and those for Subcategorization and Embedded Questions fell somewhat in between.

In order to systematically assess these differences in accuracy and probe the effects of aptitude for each structure, trial-by-trial data from the GJT were submitted to a second generalized linear mixed-effects model with a logit linking function with Response (0 = incorrect, 1 = correct) as a dependent variable and Language Aptitude, Grammatical Structure and their interaction as predictors. Education and Grammaticality were not included in this second analysis because they did not interact with Aptitude in the general analysis. Language Aptitude was centered and scaled as in the previous analysis. Since Grammatical Structure was a categorical predictor with 9 levels, it was recoded so that the Control Sentences were the reference level to be mapped onto the intercept. This way, the effect of Language Aptitude referred to the Control Sentences only, and the effects of Grammatical Structure and their interactions with Language Aptitude were to be interpreted relative to that baseline. The model’s random effects structure included random intercepts for Participants and Items and a random slope for Language Aptitude over Participants. This slope was included because it improved the model’s fit (χ2(2) = 6.22, p < 0.05). A random slope for Language Aptitude over Items was not included because it did not improve the model’s fit (χ2(2) = 2.99, p = 0.22) and a slope for Grammatical Structure over Participants was not included because it led to severe convergence issues. A summary of the model’s results is provided in Table 4. The model’s marginal and conditional pseudo-R2 values were 0.10 and 0.55, respectively.

Summary of the results of the generalized linear mixed-effects regression model assessing the effects of Language Aptitude and Grammatical Structure on accuracy in GJT.

| Predictor | b | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.11 | 7.55 | <0.001 |

| Language Aptitude | 0.25 | 2.04 | <0.05 |

| Grammatical Structure (Agreement Attraction) | −1.78 | −3.14 | <0.01 |

| Grammatical Structure (Double Tense) | −0.28 | −0.50 | 0.62 |

| Grammatical Structure (Object Agreement) | −2.22 | −3.93 | <0.001 |

| Grammatical Structure (Participial Clauses) | −2.16 | −3.79 | <0.001 |

| Grammatical Structure (Stranded Wh- Questions) | −0.93 | −1.63 | 0.10 |

| Grammatical Structure (Subcategorization) | −1.24 | −2.18 | <0.05 |

| Grammatical Structure (that Trace) | −1.85 | −3.26 | <0.01 |

| Grammatical Structure (Embedded Questions) | −1.03 | −1.79 | 0.07 |

| Language Aptitude × Grammatical Structure (Agreement Attraction) | 0.23 | 1.79 | 0.07 |

| Language Aptitude × Grammatical Structure (Double Tense) | 0.18 | 1.39 | 0.16 |

| Language Aptitude × Grammatical Structure (Object Agreement) | −0.06 | −0.50 | 0.62 |

| Language Aptitude × Grammatical Structure (Participial Clauses) | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.91 |

| Language Aptitude × Grammatical Structure (Stranded Wh- Quest.) | 0.17 | 1.32 | 0.19 |

| Language Aptitude × Grammatical Structure (Subcategorization) | 0.17 | 1.33 | 0.19 |

| Language Aptitude × Grammatical Structure (that Trace) | 0.19 | 1.54 | 0.12 |

| Language Aptitude × Grammatical Structure (Embedded Questions) | 0.10 | 0.78 | 0.43 |

In line with the descriptives discussed above, these results show that participants were less accurate with Agreement Attraction, Object Agreement, Participial Clauses, Subcategorization and that Trace items than with the Control Sentences and marginally less accurate with Embedded Questions than with the Control Sentences. No differences were found between the Control Sentences and Double Tense and Stranded Wh- Questions. Importantly, the model also revealed a significant effect of Language Aptitude on accuracy with the Control Sentences, and no significant interactions between Language Aptitude and Grammatical Structure. This suggests that the effect of Language Aptitude on performance on the GJT task is reasonably similar for all the structures tested; in other words, it seems to apply across the board. However, given that all interactions had to be interpreted relative to the baseline (i.e., the Control Sentences), we also assessed whether there was an interaction between Language Aptitude and Grammatical Structure by running a likelihood ratio test as an omnibus test of interactions comparing the final model with and without the interaction term. The results showed that including the interaction term did not significantly improve the model’s fit (χ2(8) = 13.77, p = 0.09). Hence, this additional test also failed to provide evidence that the effect of Language Aptitude significantly differs by structure, in line with the analysis above.

2.3 Interim discussion

Study 1 examined the relationship between language aptitude and grammatical proficiency using two different tasks to measure aptitude and a GJT to assess grammatical proficiency. The first relevant finding of Study 1 is that correlational analyses revealed very similar correlations with grammatical proficiency for Language Analysis (r = 0.45) and Sentence Pairs (r = 0.48), showing that the two aptitude tests predict performance on grammar similarly well. More importantly, Study 1 provides evidence for the existence of a robust relationship between language aptitude and grammatical proficiency in the native language when the latter is assessed by means of a GJT. This complements the findings reported by Dąbrowska (2018), where a very similar result was obtained when grammatical knowledge was assessed using a picture selection task. In contrast to Dąbrowska (2018), however, we found no effect of education and no interaction between education and aptitude. This could be due to the use of different grammatical tasks or to the fact that the participants in Dąbrowska’s (2018) study ranged even more broadly in educational attainment (from no formal qualifications to PhD).[4]

These results, in combination with those reported by Dąbrowska (2018), indicate that the effects of aptitude and L1 grammar are robust across grammatical tasks (comprehension vs. GJT). Furthermore, we observed no interactions between aptitude and structure, suggesting that the effects of aptitude apply across the board. We should note, however, that estimating interactions requires substantially more data than main effects (Gelman et al. 2020), so it is possible that such effects exist but require more statistical power to detect.

3 Study 2

Study 1 reported significant effects of (foreign) language aptitude, or more precisely grammatical sensitivity and inductive learning ability, on grammatical proficiency in adult native speakers recruited from a wide range of educational backgrounds. This finding suggests that the components of explicit language aptitude measured by the Sentence Pairs and Language Analysis tests may play a nontrivial role in the development of the native grammatical system. However, the presence of aptitude effects does not necessarily entail that grammatical sensitivity and/or (explicit) inductive learning ability play a role in language acquisition in all cases. One possible interpretation of our results would be that the acquisition of grammar is mostly implicit, but speakers with particularly good metalinguistic skills may complement the implicit learning mechanisms with conscious reflection in some cases – in other words, explicit aptitude could be regarded as a sort of “optional extra” available to speakers with high verbal ability.

Study 2 addresses this issue by testing whether aptitude effects can also be observed in speakers at the bottom end of the verbal ability spectrum. To this end, we tested participants who do not have any formal qualifications and have literacy levels below Level 1 of the National Qualifications Framework (NQF) for England, Northern Ireland and Wales (cf. Department for Business Innovation and Skills 2012), since such speakers are least likely to rely on metalinguistic strategies when learning their L1. Thus, the presence of aptitude effects in this group would provide particularly strong evidence against the fundamental difference hypothesis, at least with regard to the role of aptitude in L1 and L2 learning.

3.1 Methods

3.1.1 Participants

Twenty-one native speakers of English residing in the United Kingdom (14 females; mean age: 33.7, SD = 12.6) participated in the study in exchange for a small monetary compensation. Participants were recruited from Employability courses (Entry Levels 1, 2 and 3 and Level 1) and the City Horizons program offered at Southampton City College. Both courses aim to improve basic English and math skills and are intended for students who lack any formal educational qualifications; they are a prerequisite for the vocational courses offered in the same institution. NQF Entry Levels 1, 2 and 3 are equivalent to the literacy levels of typical children aged 5–7, 7–9 and 9–11 respectively. Level 1 is equivalent to GCSE grades D–G. According to the Department for Business Innovation and Skills (2012), adults with literacy levels below Level 1 constitute 15 % of the adult population of England, Wales and Scotland. All participants gave informed consent prior to testing and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

3.1.2 Materials and procedure

In this second study, we administered pen-and-paper versions of Sentence Pairs and a picture selection task assessing grammatical proficiency. Both tasks were administered by a research assistant (RA) who made sure that participants understood the instructions and answered all questions. We decided to administer all tasks on paper and with the support of an RA because the population in Study 2 was likely not to have had much experience with online testing and is known to have problems following written instructions; thus online testing and testing without supervision was likely to have a negative impact on performance.

3.1.2.1 Sentence pairs

A pen-and-paper version of the Sentence Pairs test described in Section 2.1.2.2 was used as the aptitude measure in Study 2 (see Supplementary Materials). This version was identical to the electronic version described in Study 1 except that participants respond by circling the relevant word in the second sentence of each pair.

Participants were tested in small groups in a quiet room at the institution in which they were studying. Participants were provided with a printed version of the test, and the research assistant read out the instructions. Then, the RA read out the two practice trials provided and invited participants to respond by circling one of the five underlined words. Subsequently, the RA provided the target answers and answered any questions the participants might have had before the start of the test trials. The 32 test trials were administered in the same way, that is to say, the RA read both sentences while participants followed in their own copies of the test, and then responded by circling one of the options. The RA made sure that participants had circled one of the responses before proceeding to the next item, but provided no feedback. The entire task took about 20 min to complete.

3.1.2.2 Picture selection

A picture selection task was used to measure participants’ grammatical comprehension. This was a shortened version of the task used in Dąbrowska (2018). Participants were shown pairs of pictures and an English sentence and they had to decide which picture matched the sentence. Four grammatical structures were examined, two that should be relatively easy and two that were expected to be more challenging. The former were subject relatives (e.g., the boy was the one that helped the man) and simple locative sentences (i.e., the spoon is in the cup) and the latter were object relatives (e.g., the boy was the one that the man helped) and postmodifying prepositional phrases (i.e., the spoon in the cup is red). There were a total of 10 items per structure. For subject and object relatives, the same 10 pairs of pictures were used, as each pair depicted the same action but with the roles reversed (e.g., a man helping a boy vs. a boy helping a man). For simple locatives, one of the pictures in the pair showed the correct location and the other showed the object in a different location (e.g., a spoon in a cup vs. a spoon next to the cup). Finally, for postmodifying prepositional phrases, the referent of the head noun phrase had the correct color in one of the pictures (e.g., a red spoon in a green cup), while in the other picture, the referent of the noun inside the prepositional phrase was in that color (e.g., a yellow spoon in a red cup).

The picture selection task was administered individually in a quiet room at the institution where the participants were studying. On each trial, the RA read one sentence aloud, asked the participant to indicate which picture went with it, and recorded their responses. Participants could respond verbally (e.g., “the first picture” or “the picture on the left”) or by pointing. The task took approximately 12–15 min.

3.2 Results

Performance on the Sentence Pairs task varied widely (from 3 % to 59 % correct, with a mean at 32 % and a SD of 20). Since there were five response options for each item, chance performance in this task would have been 20 % and there were 15 out of the 21 participants (i.e., 71 %) who performed above this level. Note, however, that a mean of 32 % is almost 1.3 standard deviations below the mean for the sample in Study 1. The Spearman-Brown corrected reliability estimate (i.e., split-half reliability) for the Sentence Pairs test in Study 2 was 0.85 (95 % CI [0.75, 0.93]).

In the grammatical comprehension task, participants had an overall mean accuracy of 87 % correct (SD = 12). Regarding the two more challenging structures, they were 85 % correct with postmodifying PPs (SD = 19) and only 69 % correct with object relatives (SD = 28), and exhibited large individual differences, as indicated by the high standard deviations. By contrast, scores for the two easier structures, that is, subject relatives and simple locatives, were much higher and in fact mostly at ceiling (subject relatives = 95 % correct, SD = 8; simple locatives = 98 % correct, SD = 4). The good performance on the easy sentences indicates that the participants had understood the task and were cooperative; thus, the errors on the more difficult structures are attributable to problems with understanding the sentences rather than to linguistically irrelevant performance factors. The split-half reliability estimate for the picture selection task was 0.83 (95 % CI [0.68, 0.93]).

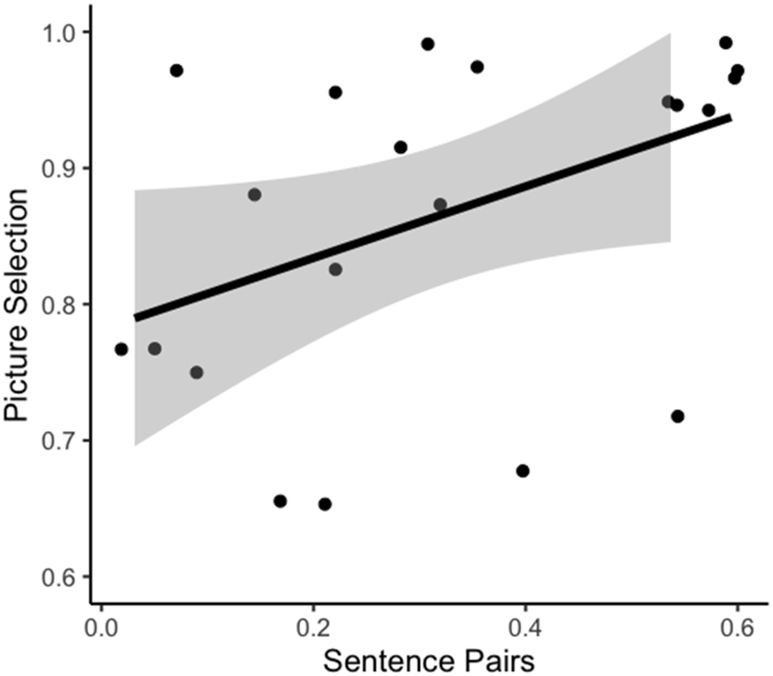

In order to assess the effect of language aptitude on performance on the picture selection task, trial-by-trial data from this task (840 trials; 21 participants × 40 trials) were submitted to a generalized linear mixed-effects model with a logit linking function with Response (0 = incorrect, 1 = correct) as the categorical dependent variable and Language Aptitude as a predictor. Language Aptitude scores were centered and scaled using the scale() function in R. The model included random intercepts for Participants and Items. Random slopes for Language Aptitude over Participants and Items were not included because they did not improve the model’s fit (over Participants: χ2(2) = 0.22, p = 0.90; over Items: χ2(2) = 2.47, p = 0.29). The model revealed a significant effect of Language Aptitude (b = 0.72; z = 2.35; p < 0.05). The model’s marginal and conditional pseudo-R2 values were 0.06 and 0.59, respectively. The significant effect of aptitude indicates that performance in the language aptitude test assessing (explicit) grammatical sensitivity predicted participants’ overall performance in the grammatical comprehension task. A scatterplot of the proportions of correct responses by participant in the two tasks is provided in Figure 3. The correlation between aptitude and grammatical proficiency as illustrated in Figure 3 was medium-sized and just about significant (r(19) = 0.43, p = 0.05). Correlations between performance on the four structures and Language Aptitude can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Scatterplot of individual mean proportion of correct responses for Sentence Pairs and mean proportion of correct responses for Picture Selection in Study 2.

3.3 Interim discussion

The results of Study 2 again revealed a significant effect of language aptitude on performance in a task assessing grammatical proficiency in the participants’ L1. Importantly, the relationship for aptitude as measured by the Sentence Pairs test and grammatical proficiency as measured through a picture selection task was virtually identical to that observed in Study 1 for the Sentence Pairs test and an auditory GJT, as well as to that of Dąbrowska (2018) for the Language Analysis subtest of the PLAB and picture selection.

This high degree of convergence across the three studies invites several conclusions. In the first place, Study 2 shows that the Sentence Pairs test is not only able to capture individual differences in language aptitude in educated participants (Study 1) but can also be used with participants with low literacy and academic attainment and still result in a wide range of scores, with most participants performing above chance but with plenty of room for improvement. Secondly, the fact that very similar relationships between Sentence Pairs and grammatical proficiency were obtained in Studies 1 and 2 shows that the findings of Study 1 cannot be explained away by saying that GJTs and Sentence Pairs both strongly rely on metalinguistic awareness. This is because the picture selection task used in Study 2 (and by Dąbrowska 2018) focuses on meaning and makes minimal metalinguistic demands. Finally, in spite of its small sample size (vs. Study 1), Study 2 also confirms that a relationship between language aptitude and grammar is still in place when educational attainment is controlled for.

4 General discussion

The present study tested the relationship between (explicit) language aptitude, more specifically inductive learning ability and grammatical sensitivity, as measured by the Language Analysis subtest of the PLAB (Study 1) and our newly-developed Sentence Pairs test (Studies 1 and 2) respectively, and two tasks probing native speakers’ grammatical proficiency: a GJT (Study 1) and a picture selection task (Study 2). The results of the two studies revealed a robust relationship between the two variables that appears to hold across a variety of grammatical structures and that is remarkably consistent across different measures of aptitude and grammatical proficiency. In fact, the correlation coefficients observed in the two studies and in Dąbrowska (2018) are almost identical: 0.46 for the relationship between Language Analysis and grammatical comprehension assessed using picture selection in Dąbrowska (2018); 0.43 for Sentence Pairs and Picture Selection in Study 2, and 0.45 and 0.48 for Language Analysis and GJT and Sentence Pairs and GJT respectively in Study 1.

Importantly, these relationships are all stronger than the mean effect size reported in Li’s (2015) meta-analysis of the effects of language analytic ability on L2 grammatical attainment (mean r = 0.31, CI from 0.25 to 0.36). As discussed in the Introduction, (foreign) language aptitude tests like the MLAT and PLAB measure explicit language aptitude, in that the tasks involved require explicit attention and conscious effort. Furthermore, performance on these tests correlates quite strongly with the results of IQ tests (see Li 2016). Therefore, our results are compatible with the proposal that explicit learning may also play a role in first language acquisition and not only in late L2 learning (Dąbrowska 2010; Llompart and Dąbrowska 2020).

Yet most language acquisition researchers take it as self-evident that language aptitude is only relevant for late L2 acquisition. Why is this the case? Before we discuss this question, it is important to point out that the empirical evidence for this claim is slim, to say the least. Most of the relevant evidence comes from studies reporting significant correlations between language aptitude and L2 performance in adult learners but not in native speaker controls. However, in most cases, the lack of an effect for native speakers is likely to be simply due to lack of statistical power. For instance, Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam (2008) report a non-significant correlation of 0.47 between aptitude and performance on a GJT task in native speakers. However, given the sample size (15), the probability of finding a significant result is only 0.50. In a study by Granena and Long (2013), the correlation coefficient for native speaker controls was lower (0.30); with only 12 participants, power was only 0.15. Finally, DeKeyser (2000) examined the relationship between aptitude and GJT in naturalistic L2 learners who differed in age of arrival and found a significant correlation in the older learners but no effect in younger learners (0.07). In this case, the lack of effect is likely to be due to ceiling effects in the latter group, as the younger arrivals’ mean score on the GJT was 96 %.

In contrast, three other studies (Dąbrowska 2018; Skehan and Ducroquet 1988 and an unpublished study by Abrahamsson discussed in Skehan 2014) do report significant results for native speakers. Furthermore, two other studies investigated the relationship between aptitude performance on a GJT in the L1 of heritage language speakers. The first of these (Bylund et al. 2010) tested native speakers of Spanish who moved to Sweden before puberty (mean AoA = 5.7) and found a significant relationship (r = 0.52). The second (Bylund and Ramírez-Galan 2016) tested Spanish-Swedish bilinguals with higher ages of arrival (mean = 24.3). In this group, the correlation was also positive but did not reach statistical significance (r = 0.27, p = 0.10). Thus, the conviction that (explicit) language aptitude is not relevant to first language acquisition is not based on solid empirical findings. Rather, it seems to follow from some fundamental (and often implicit) assumptions about how people learn their first language, and how L1 acquisition differs from late L2 acquisition.

Two caveats are necessary at this point. First, it is important to emphasize that the evidence for a relationship between aptitude and grammatical proficiency reported here is purely correlational. Therefore, it is possible that the direction of causality between these two variables is the opposite of the one we hypothesize here: that is to say, it could be argued that it is individual differences in L1 attainment that lead to differences in metalinguistic awareness, which are then reflected in differences in performance on language aptitude tests assessing grammatical sensitivity and inductive learning ability. Note, however, that the same reservation also applies to the arguments about the role of language aptitude in late L2 learning put forward in many previous studies (e.g., Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam 2008; Granena and Long 2013).[5] In fact, to the extent that learning foreign languages in instructional settings improves metalinguistic awareness, this argument might be more easily applied to adult L2 learning than ultimate attainment in the L1.

In any case, arguing that better grammatical knowledge results in higher metalinguistic awareness is problematic in itself because, to our knowledge, there is no evidence that mastering a grammatical construction boosts metalinguistic awareness of its internal structure. This hypothesis is particularly odd in the context of L1 acquisition, given that most native speakers have very little metalinguistic awareness yet are able to speak their language fluently and produce complex structures. In fact, as the mastery that L1 speakers possess is assumed to be associated to a high level of automaticity, one would actually expect the opposite; that is, that better grammatical knowledge were linked to less metalinguistic awareness. In contrast to this, there is ample evidence from adult L2 acquisition that an increase in awareness can lead to better acquisition of grammatical features (Norris and Ortega 2005; Spada and Tomita 2010). This also appears to hold for children. For example, in an experiment conducted by Lichtman (2016), children aged from 5 to 7 learned an artificial language either under explicit or implicit training conditions. Children in the explicit group developed better awareness of the grammatical properties of the artificial language than those exposed to the implicit training regime and, critically, better awareness was strongly associated with better overall performance.

A third possibility that should also be contemplated is that both explicit language aptitude and language acquisition depend on the same underlying ability. An obvious candidate here is general intelligence. As already mentioned, results of traditional language aptitude tests consistently correlate with intelligence, and studies using factor analytical procedures have shown that IQ and several components of aptitude tests load onto the same underlying constructs (Granena 2012, 2013; Sasaki 1996). All things considered, this is not extremely surprising, as many IQ tests include measures of L1 vocabulary and memory, which are also targeted by language aptitude tests. However, language aptitude is a better predictor of foreign language achievement than IQ (Li 2016), presumably because language aptitude tests also contain tasks that are particularly relevant for language learning, such as measures of phonetic coding ability or the ability to form associations between novel forms and visual representations.

The second caveat concerns the developmental period during which these causal relationships may play out. The existence of a relationship between grammar and language aptitude in adults does not allow us to make any inferences about when aptitude exerts its causal influence (if the relationship is indeed causal). It is possible that the effect occurs in early childhood, but it could also happen later, given that, as mentioned in the introduction, performance on tasks assessing grammatical ability continues to improve until about age 30 (Hartshorne et al. 2018).

Irrespective of the direction of causality and the point in development during which language aptitude may exert its influence, the results of the present study have important implications for our understanding of the mental abilities which contribute to language learning. In particular, together with findings from previous studies (Dąbrowska 2018; Skehan and Ducroquet 1988), we provide evidence that the arguments for a fundamental difference between L1 and L2 acquisition based on the premise that only the latter is related to aptitude (e.g., Bley-Vroman 1989; DeKeyser 2000; DeKeyser et al. 2010) are simply not valid. Our results are also compatible with a large body of research which noted a strong relationship between L1 literacy and the development of L2 skills (see, for example, Dufva and Voeten 1999; Hulstijn and Bossers 1992; Sparks et al. 2009).

This is not to say that there is no difference whatsoever between L1 and L2 regarding the roles of aptitude and explicit learning abilities. It could well be that language learning in adults relies to a greater extent on aptitude, metalinguistic awareness and explicit learning mechanisms, even if this view, at least as far as aptitude is concerned, is directly challenged by the fact that the correlations in this study for native speakers are larger than the average correlation reported by Li (2015) for late L2 learners. Be that as it may, the results reported here show that, at the very least, we need to seriously consider the idea that explicit learning and explicit learning abilities such as metalinguistic awareness play a relevant role in L1 acquisition as well as L2 acquisition. Further research will now be necessary to refine the characterization of potential similarities and differences between L1 and L2 in terms of the involvement of intelligence, aptitude and explicit learning mechanisms.

Funding source: Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung

Award Identifier / Grant number: ID-1195918

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by an Alexander von Humboldt Professorship (ID-1195918) awarded to the second author. We thank Magdalena Grose-Hodge for her help with participant recruitment and data collection for the second study in this article.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets analyzed in the current study and the code and materials necessary to reproduce the analyses are available in the Open Science Framework at: https://osf.io/qdkuh/.

References

Abrahamsson, Niclas & Kenneth Hyltenstam. 2008. The robustness of aptitude effects in near-native second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 30(4). 481–509. https://doi.org/10.1017/S027226310808073X.Search in Google Scholar

Acheson, Daniel J., Justine B. Wells & Maryellen C. MacDonald. 2008. New and updated tests of print exposure and reading abilities in college students. Behavior Research Methods 40(1). 278–289. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.1.278.Search in Google Scholar

Ambridge, Ben. 2012. Assessing grammatical knowledge (with special reference to the graded grammaticality judgment paradigm). In Erika Hoff & Li Wei (eds.), Research methods in child language: A practical guide, 113–132. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.10.1002/9781444344035.ch8Search in Google Scholar

Ambridge, Ben. 2014. Grammaticality judgment task. In Patricia J. Brooks & Vera Kempe (eds.), Encyclopedia of language development, 261–262. Washington, DC: SAGE.Search in Google Scholar

Anwyl-Irvine, Alexander L., Jessica Massonnié, Adam Flitton, Natasha Kirkham & Jo K. Evershed. 2020. Gorilla in our midst: An online behavioral experiment builder. Behavior Research Methods 52(1). 388–407. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01237-x.Search in Google Scholar

Barton, Kamil. 2009. MuMIn: Multi-model inference (R Package Version 1.43.17). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/MuMIn/index.html.Search in Google Scholar

Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker & Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01.Search in Google Scholar

Birdsong, David. 1989. Metalinguistic performance and interlinguistic competence (Language and Communication 25). Heidelberg: Springer.10.1007/978-3-642-74124-1Search in Google Scholar

Bley-Vroman, Robert. 1989. What is the logical problem of foreign language learning? In Jacquelyn Schachter & Susan M. Gass (eds.), Linguistic perspectives on second language acquisition (Cambridge Applied Linguistics), 41–68. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139524544.005Search in Google Scholar

Bylund, Emanuel, Niclas Abrahamsson & Kenneth Hyltenstam. 2010. The role of language aptitude in first language attrition: The case of pre-pubescent attriters. Applied Linguistics 31(3). 443–464. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amp059.Search in Google Scholar

Bylund, Emanuel & Pedro Ramírez-Galan. 2016. Language aptitude in first language attrition: A study on late Spanish-Swedish bilinguals. Applied Linguistics 37(5). 621–638. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amu055.Search in Google Scholar

Carroll, John B. 1964. The prediction of success in intensive foreign language training. In Robert Glaser (ed.), Training research and education, 87–136. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.Search in Google Scholar

Carroll, John B. 1973. Implications of aptitude test research and psycholinguistic theory for foreign language teaching. Linguistics 11(112). 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1515/ling.1973.11.112.5.Search in Google Scholar

Carroll, John B. 1981. Twenty-five years of research on foreign language aptitude. Individual Differences and Universals in Language Learning Aptitude 83(117). 867–873.Search in Google Scholar

Carroll, John B. 1990. Cognitive abilities in foreign language aptitude: Then and now. In Thomas S. Parry & Charles W. Stansfield (eds.), Language aptitude reconsidered, 11–29. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.Search in Google Scholar

Carroll, John B. & Stanley M. Sapon. 1959. Modern language aptitude test. Washington, DC: Second Language Testing Incorporated.Search in Google Scholar

Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.10.21236/AD0616323Search in Google Scholar

Dąbrowska, Ewa. 2010. Productivity, proceduralisation and SLI: Comment on Hsu and Bishop. Human Development 53. 276–284.Search in Google Scholar

Dąbrowska, Ewa. 2012. Different speakers, different grammars: Individual differences in native language attainment. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 2(3). 219–253. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.2.3.01dab.Search in Google Scholar

Dąbrowska, Ewa. 2015. Individual differences in grammatical knowledge. In Ewa Dąbrowska & Dagmar Divjak (eds.), Handbook of cognitive linguistics, 649–667. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110292022-033Search in Google Scholar

Dąbrowska, Ewa. 2018. Experience, aptitude and individual differences in native language ultimate attainment. Cognition 178. 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.05.018.Search in Google Scholar

Dąbrowska, Ewa. 2019. Experience, aptitude, and individual differences in linguistic attainment: A comparison of native and nonnative speakers. Language Learning 69(S1). 72–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12323.Search in Google Scholar

Dąbrowska, Ewa, Laura Becker & Luca Miorelli. 2020. Is adult second language acquisition defective? Frontiers in Psychology Frontiers 11. 1839. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01839.Search in Google Scholar

Dąbrowska, Ewa & James Street. 2006. Individual differences in language attainment: Comprehension of passive sentences by native and non-native English speakers. Language Sciences 28(6). 604–615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2005.11.014.Search in Google Scholar

DeKeyser, Robert M. 2000. The robustness of critical period effects in second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 22(4). 499–533. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263100004022.Search in Google Scholar

DeKeyser, Robert M., Iris Alfi-Shabtay & Dorit Ravid. 2010. Cross-linguistic evidence for the nature of age effects in second language acquisition. Applied Psycholinguistics 31(3). 413–438. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716410000056.Search in Google Scholar

DeKeyser, Robert M. & Jenifer Larson-Hall. 2005. What does the critical period really mean? In Judith F. Kroll & Annette M. B. De Groot (eds.), Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches, 88–108. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780195151770.003.0006Search in Google Scholar

Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. 2012. The 2011 skills for life survey: A survey of literacy, numeracy and ICT levels in England (Bis research paper number 81). Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/36000/12-p168-2011-skills-for-life-survey.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

Devitt, Michael. 2006. Ignorance of language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/0199250960.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Dörnyei, Zoltán & Peter Skehan. 2003. Individual differences in second language learning. In Catherine J. Doughty & Michael H. Long (eds.), The handbook of second language acquisition, 589–630. Malden, MA: Blackwell.10.1002/9780470756492.ch18Search in Google Scholar

Dufva, Mia & Marinus J. M. Voeten. 1999. Native language literacy and phonological memory as prerequisites for learning English as a foreign language. Applied Psycholinguistics 20(3). 329–348. https://doi.org/10.1017/S014271649900301X.Search in Google Scholar

Ellis, Nick C. 1996. Sequencing in SLA: Phonological memory, chunking, and points of order. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 18(1). 91–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263100014698.Search in Google Scholar

Farmer, Thomas A., Jennifer B. Misyak & Morten H. Christiansen. 2012. Individual differences in sentence processing. In Michael Spivey, Ken McRae & Marc Joanisse (eds.), Cambridge handbook of psycholinguistics, 353–364. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139029377.018Search in Google Scholar

Field, Andy, Jeremy Miles & Zoë Field. 2012. Discovering statistics using R. London: SAGE.Search in Google Scholar

Gelman, Andrew, Jennifer Hill & Aki Vehtari. 2020. Regression and other stories (Analytical Methods for Social Research). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781139161879Search in Google Scholar

de Graaff, Rick & Alex Housen. 2009. Investigating the effects and effectiveness of L2 instruction. In Michael H. Long & Catherine J. Doughty (eds.), The handbook of language teaching, 726–765. Oxford: Blackwell.10.1002/9781444315783.ch38Search in Google Scholar

Granena, Gisela. 2012. Age differences and cognitive aptitudes for implicit and explicit learning in ultimate second language attainment. College Park, MD: University of Maryland Dissertation.Search in Google Scholar

Granena, Gisela. 2013. Cognitive aptitudes for second language learning and the LLAMA language aptitude test. In Gisela Granena & Mike Long (eds.), Sensitive periods, language aptitude, and ultimate L2 attainment (Language Learning & Language Teaching 35), 105–130. Amsterdam & Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.10.1075/lllt.35.04graSearch in Google Scholar

Granena, Gisela & Michael H. Long. 2013. Age of onset, length of residence, language aptitude, and ultimate L2 attainment in three linguistic domains. Second Language Research 29(3). 311–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658312461497.Search in Google Scholar

Hartshorne, Joshua K., Joshua B. Tenenbaum & Steven Pinker. 2018. A critical period for second language acquisition: Evidence from 2/3 million English speakers. Cognition 177. 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.04.007.Search in Google Scholar

Hopp, Holger. 2010. Ultimate attainment in L2 inflection: Performance similarities between non-native and native speakers. Lingua 120(4). 901–931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2009.06.004.Search in Google Scholar

Hopp, Holger. 2013. Grammatical gender in adult L2 acquisition: Relations between lexical and syntactic variability. Second Language Research 29(1). 33–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658312461803.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Yujing & Fernanda Ferreira. 2020. The application of signal detection theory to acceptability judgments. Frontiers in Psychology 11. 73. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00073.Search in Google Scholar

Hulstijn, Jan H. & Bart Bossers. 1992. Individual differences in L2 proficiency as a function of L1 proficiency. The European Journal of Cognitive Psychology 4(4). 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/09541449208406192.Search in Google Scholar

Kidd, Evan. 2012. Implicit statistical learning is directly associated with the acquisition of syntax. Developmental Psychology 48(1). 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025405.Search in Google Scholar

Kidd, Evan & Joanne Arciuli. 2016. Individual differences in statistical learning predict children’s comprehension of syntax. Child Development 87(1). 184–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12461.Search in Google Scholar

Kidd, Evan, Seamus Donnelly & Morten H. Christiansen. 2018. Individual differences in language acquisition and processing. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 22(2). 154–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2017.11.006.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Jeong-eun & Hosung Nam. 2017. Measures of implicit knowledge revisited: Processing modes, time pressure, and modality. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 39(3). 431–457. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263115000510.Search in Google Scholar

van der Lely, Heather K. J., Melanie Jones & Chloë R. Marshall. 2011. Who did Buzz see someone? Grammaticality judgment of wh-questions in typically developing children and children with Grammatical-SLI. Lingua 121(3). 408–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2010.10.007.Search in Google Scholar

Leys, Christophe, Christophe Ley, Olivier Klein, Philippe Bernard & Laurent Licata. 2013. Detecting outliers: Do not use standard deviation around the mean, use absolute deviation around the median. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 49(4). 764–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2013.03.013.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Shaofeng. 2015. The associations between language aptitude and second language grammar acquisition: A meta-analytic review of five decades of research. Applied Linguistics 36(3). 385–408. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amu054.Search in Google Scholar

Li, Shaofeng. 2016. The construct validity of language aptitude: A meta-analysis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 38(4). 801–842. https://doi.org/10.1017/S027226311500042X.Search in Google Scholar

Lichtman, Karen. 2016. Age and learning environment: Are children implicit second language learners? Journal of Child Language 43(3). 707–730. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000915000598.Search in Google Scholar

Linebarger, Marcia C., Myrna F. Schwartz & Eleanor M. Saffran. 1983. Sensitivity to grammatical structure in so-called agrammatic aphasics. Cognition 13(3). 361–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(83)90015-X.Search in Google Scholar

Llompart, Miquel & Ewa Dąbrowska. 2020. Explicit but not implicit memory predicts ultimate attainment in the native language. Frontiers in Psychology 11. 569586. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.569586.Search in Google Scholar

Llompart, Miquel & Eva Reinisch. 2017. Articulatory information helps encode lexical contrasts in a second language. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 43(5). 1040–1056. https://doi.org/10.1037/xhp0000383.Search in Google Scholar

Llompart, Miquel & Eva Reinisch. 2020. The phonological form of lexical items modulates the encoding of challenging second-language sound contrasts. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 46(8). 1590–1610. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000832.Search in Google Scholar

Macmillan, Neil A. & C. Douglas Creelman. 2005. Detection theory: A user’s guide, 2nd edn. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.Search in Google Scholar

McDonald, Janet L. 2006. Beyond the critical period: Processing-based explanations for poor grammaticality judgment performance by late second language learners. Journal of Memory and Language 55(3). 381–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2006.06.006.Search in Google Scholar

McLaughlin, Barry. 1990. The relationship between first and second languages: Language proficiency and language aptitude. In Birgit Harley, Patrick Allen, Jim Cummins & Merrill Swain (eds.), The development of second language proficiency, 158–174. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139524568.014Search in Google Scholar

Montrul, Silvina. 2008. Incomplete acquisition in bilingualism: Re-examining the age factor (Studies in Bilingualism 39). Amsterdam & Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins. Available at: https://www.jbe-platform.com/content/books/9789027290410.10.1075/sibil.39Search in Google Scholar

Norris, John & Lourdes Ortega. 2005. Does type of instruction make a difference? Substantive findings from a meta‐analytic review. Language Learning 51. 157–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.2001.tb00017.x.Search in Google Scholar

Orfitelli, Robyn & Maria Polinsky. 2017. When performance masquerades as comprehension: Grammaticality judgments in experiments with non-native speakers. In Mikhail Kopotev, Olga Lyashevskaya & Arto Mustajoki (eds.), Quantitative approaches to the Russian language, 197–214. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781315105048-10Search in Google Scholar

Palan, Stefan & Christian Schitter. 2018. Prolific.ac – a subject pool for online experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 17. 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2017.12.004.Search in Google Scholar

Parsons, Sam. 2021. Splithalf: Robust estimates of split half reliability. Journal of Open Source Software 6(60). 3041. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03041.Search in Google Scholar

Pili-Moss, Diana, Katherine A. Brill-Schuetz, Mandy Faretta-Stutenberg & Kara Morgan-Short. 2020. Contributions of declarative and procedural memory to accuracy and automatization during second language practice. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 23(3). 639–651. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728919000543.Search in Google Scholar

Pimsleur, Paul. 1966. Pimsleur language aptitude battery (form S). New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace and World.Search in Google Scholar

Pimsleur, Paul, Daniel J. Reed & Charles W. Stansfield. 2004. Pimsleur language aptitude battery: Manual 2004 edition. Bethesda, MD: Second Language Testing.Search in Google Scholar

Pinker, Steven. 1999. Words and rules. The ingredients of language. New York, NY: Basic Books.Search in Google Scholar

Plonsky, Luke, Emma Marsden, Dustin Crowther, Susan M. Gass & Patti Spinner. 2020. A methodological synthesis and meta-analysis of judgment tasks in second language research. Second Language Research 36(4). 583–621. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658319828413.Search in Google Scholar