Abstract

The China Weekly Review ( The Review ) was an English-language weekly political and financial magazine established in Shanghai, China, in 1917 by Thomas F. Millard and John B. Powell, two American news professionals. With a team of skilled journalists trained in American journalistic practices, The Review covered major political and social issues in China using American reportorial methods. It tracked the evolution of extraterritoriality in China, offering detailed international context and presenting multiple perspectives from the Treaty Powers. It also humanized this complicated and controversial issue by relating it to gambling and opium smuggling, and thus published numerous compelling stories exposing various abuses related to this issue. As a periodical review, in the early years, it took a clear stance of arguing for complete abolishment of extraterritoriality in China, which distinguished it from most other Western newspapers in China. Therefore, The Review cultivated an image of the U.S. as more favorable to or aligned with Chinese interests than other Western powers, particularly Britain. However, by the late 1940s, its reporting began to reflect a more complex and sometimes negative view of developments in China. Consequently, assessments of The Review’s stance on Chinese affairs should consider the specific historical context and content of its reporting during different periods.

Extraterritoriality (or extrality) was an extremely complicated and controversial topic in the global colonial period, during which some Western powers used it to secure significant economic advantages in many countries and regions under colonial influence. It was even more complicated in China when the Treaty Powers expanded their privileges under the guise of extraterritoriality. Wellington Koo, a well-known Chinese diplomat, specifically defined the extraterritoriality that the powers acquired in China in his dissertation submitted to Columbia University, New York, where he majored in international relations and diplomacy. In his dissertation, Koo describes the two types of extraterritorialities enjoyed by the Powers in China:

Unlike the so-called extraterritoriality of diplomatic officers, the abnormal system is legally constituted by two concurrent conditions, namely, the exemption, partial or complete, of aliens from the territorial laws and the application to them to the same extent, by their representatives within the territory, of the laws of their own country. (Koo 1912, 62)

British colonizers initiated the Western powers’ quest for extraterritoriality in China. In retrospect, Koo also stressed the significance of British colonizers’ key role in the expansion of extraterritoriality in China:

Indeed, when hostilities broke out in 1839 between the two countries over the opium question, extraterritoriality in China, as far as the British subjects were concerned, may be said to have already traversed a persistent, though slow and irregular, course of development; to have fought many battles with the Chinese authorities for its own existence, undergone several stages of experimentation, and begun to assume an aspect of stability and appear as the inevitable, in spite of the vigorous and continued efforts of the [then Chinese government] to oppose and subvert it. What Great Britain succeeded, therefore, in wringing from China at the end of the expensive and ignoble war in 1842, in respect of China, was merely an official recognition of what had already been brought into being and engrafted on her, in practice, without her consent or countenance. (Koo 1912, 63)

The evolution of extraterritoriality in China proved this statement. All the extra rights that the aliens acquired in China were put into effect through a series of unequal treaties. Subsequently, the United States secured similar rights through its “Open Door” policy. Japan’s growing influence in China, particularly under the framework of unequal treaties, heightened concerns among Chinese intellectuals and reformers about national sovereignty, prompting calls for the gradual or immediate abolition of extraterritoriality.

Since 1911, when the Qing Dynasty was replaced by the Republic of China, the colonizers of various Treaty Powers had been constantly bothered by some questions: What type of government would replace the Qing Dynasty, which had appeared subservient to the Treaty Powers? Would there be changes to the settlements, where they had enjoyed a privileged lifestyle? More importantly, would they retain the extensive privileges granted by the unequal treaties signed with the Qing Dynasty? These concerns prompted the colonizers to consider making some policy concessions (Lu 2009, 171).

As a political and financial weekly magazine with pronounced anti-Japanese and anti-British sentiments, The China Weekly Review (here after The Review) was established by Thomas F. Millard and John B. Powell. Millard was among the first Western professional journalists to cover China, beginning in the late 19th century. He then founded The China Press, a daily newspaper in the American journalistic style, in Shanghai in 1903. Therefore, he was even called “the founding father of American journalism in China” (Mackinnon and Friesen 1992, 23). In 1910, John B. Powell graduated from the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism (MU J-School), the world’s first journalism school, established in 1908. Millard sought a professionally educated journalist to help him establish another American newspaper in Shanghai. In response to Millard’s request, Walter Williams, the first dean of MU J-School, recommended Powell. Powell agreed to come to China, intending to apply the American journalistic principles that Williams had championed throughout his career (Williams and Williams 1961). As a result, The Review was founded on June 9, 1917. For over 32 years, The Review provided extensive coverage of extraterritoriality, employing a range of journalistic techniques, with its publication in China and circulation worldwide.

1 Backgrounding and Following Extraterritoriality

Unlike extraterritoriality in other countries, the special rights that the Powers enjoyed in China during its semi-colonial period were based on a series of unequal treaties. To explain the complexities of extraterritoriality in China, The Review published numerous “Special Articles” detailing its historical background. On April 24, 1937, a special article titled “History of Extraterritorial Rights in China” appeared in the magazine, extensively tracing the evolution of extraterritoriality globally and in detail within China. According to this article, the history of extraterritoriality can be traced to medieval Europe, from which colonizers expanded their privileges, notably from Türkiye to other parts of the world. The Portuguese initiated extraterritoriality in China when they established a presence in Macao in South China in the mid-16th century. Dutch and British businesspeople followed in the next century. The British played a crucial role in acquiring further privileges from China under the Qing Dynasty. In 1710, British businesspeople in Guangzhou elected the so-called “Select Committee of John Company’s Men” and began to manage the company by enforcing British laws in China. In 1787, the British government granted this committee legal administrative authority over British business in China. Although the Chinese government refused to acknowledge the existence of the committee and its rights endowed by the British government, it was regarded as the formal beginning of the long history of “extraterritoriality” in China (Loo 1937, 284). The article then traced how Western powers expanded extraterritoriality by compelling China to sign a series of unequal treaties.

In the twentieth century, China’s calls for the abolition of foreign powers’ privileges intensified. The Review provided a detailed account of the progress towards abolishing extraterritoriality in China. As commercial and economic interests in China grew, the Treaty Powers felt compelled to improve relations, signing further commercial treaties that included clauses regarding the potential relinquishment of extraterritorial rights. Britain took the lead with the 1902 Renewed Treaty of Commerce and Navigation, in which the British government agreed to relinquish extraterritorial privileges conditional upon China implemented certain reforms (Loo 1937, 285). The years leading up to the end of World War I saw no progress in China’s efforts to abolish extraterritorial rights. This was partly due to China’s focus on the rising tide of patriotic sentiment, culminating in the Revolution of 1911 and the establishment of the Republic of China. It was also partly due to the foreign powers’ preoccupation with the war, where their own national survival was at risk. In 1921, Germany became the first European Power to acknowledge and respect the absolute sovereignty of China, followed by the Soviet Union in 1924. According to The Review, in September 1926, 13 Western powers signed The Report of the Commission on Extraterritoriality, which recommended that, “when certain conditions have been satisfied, the Powers concerned should relinquish extraterritorial privileges” (Loo 1937, 286). This report represents the first constructive step taken collectively by foreign Powers. However, 10 years passed without significant progress towards abolition. The Review therefore argued, “It is time for European Powers to take collective action in relinquishing their extraterritorial rights, as these rights are detrimental to the sovereignty of China” (Loo 1937, 286). But this call was sidelined again as the Chinese People’s War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression began.

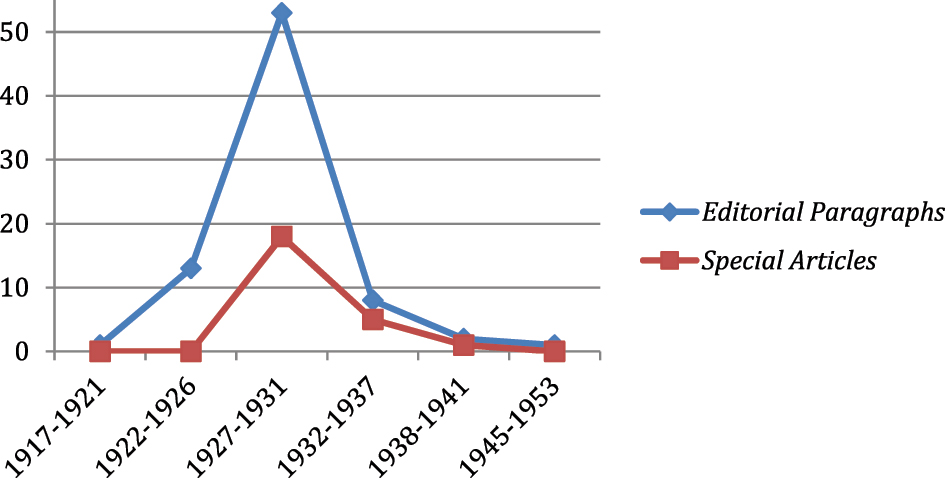

The Review consistently covered the issue of extraterritoriality, reporting on it through various methods. During its over 32 years of publication in Shanghai, The Review published at least 78 editorials and more than 20 special articles on this topic. The following graph shows the distribution of the two major types of articles concerning “extraterritoriality” in different periods of The Review. In the first period (1917–1921), only one editorial paragraph focused on extraterritoriality, as it was not a prominent issue at the time, with some countries viewing China as lacking the power to restore its autonomy in many areas. John B. Powell significantly increased coverage of extraterritoriality after becoming publisher of The Review. This became particularly evident after Kuomintang came to power in the late 1920s. From 1922 to 1931, The Review published 66 editorial paragraphs and 18 extensive special articles on extraterritoriality, demonstrating the magazine’s emphasis on this increasingly important issue. As China was caught in the turmoil of the ten-year civil war and later became embroiled in the War of Resistance against Japanese aggression, calls for abolishing extraterritoriality diminished in the 1930s. During this period, only 10 editorial paragraphs and six special articles were published in The Review. When the Chinese government formally signed an agreement abolishing extraterritoriality with the British and American governments in 1943, it had been one and a half years since The Review had been forced to cease publication in late 1941, shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The long-standing issue saw significant resolution when John W. Powell, son of John B. Powell, resumed publication of The Review in Shanghai in October 1945. In 1946, the magazine published its final commentary on this issue to be analyzed for this paper, noting that Chinese Hong Kong, Chinese Macao, and a few other foreign settlements in Chinese coastal cities still remained as symbols of extraterritoriality in China. That same year, France became the last country to agree to relinquish all its extraterritorial rights on the Chinese mainland (Graph 1).

The Distribution of The Review’s Coverage on Extraterritoriality. (1) Editorial Paragraphs refer to the most important column, which long occupied the front pages of The Review, which also spent much space on Special Articles, some in-depth stories including feature stories, interpretative reports and investigative reports, etc. (2) This graph only includes those Editorial Paragraphs and Special Articles with the key word of “Extraterritoriality” or “Extrality” in their titles, but excludes those articles which may mention this issue in their bodies. (3) The graph shows the number of Editorial Paragraphs and Special Articles about “extraterritoriality” in six periods of different time spans without clear cuts due to the situations in China.

The graph illustrates The Review’s sustained coverage of extraterritoriality throughout its over 32 years of publication in China. Compiling all of The Review’s “Editorial Paragraphs” and “Special Articles” on the topic would create a substantial record of extraterritoriality in China. Unlike other foreign newspapers in China, The Review advocated for the abolition of extraterritorial privileges long before the Chinese movement for abolition gained momentum. The magazine then continued to promote the progress of this abolition. In its early years of publication, The Review demonstrated understanding of some Chinese intellectuals’ calls for abolishing the powers’ special rights in China. This is evident in an editorial paragraph published on August 20, 1921, prior to the Pacific Conference in Washington:

There seems to be every indication that a certain section of the Chinese capable of voicing public opinion are convinced that the approaching Pacific Conference is the proper time and place to bring up the matter of the abolition of extraterritoriality. They see in the conference a panacea to alleviate all of China’s shortcomings and an opportunity to retrieve all of those grants which, because of the weakness of the nation and the instability of its government, have been made to foreign powers and citizens. They desire in addition to the abolition of extraterritoriality, the return of all concessions to China, an affirmation of the tariff autonomy of the country, and such other reforms as will completely restore the sovereignty of the nation. This movement has not had its birth since the calling of the Washington conference as it has been becoming more and more evident during the past three years. (The China Weekly Review, Aug 20, 1921, 595)

Although The Review expressed understanding of the Chinese position, it argued that resolving the issue would require a gradual process, not a single action. Then it stood along with Chinese intellectuals calling for abolishing the extraterritoriality enjoyed by the Treaty Powers in China. Even after extraterritoriality was abolished on the Chinese mainland, The Review criticized British and Portuguese authorities in Chinese Hong Kong and Chinese Macao, demanding the immediate return of the two port cities, which had been seized by force. In a separate article, the magazine predicted that all the other foreign settlements in Chinese cities would be ended soon: “Regardless of arguments for retaining these ‘concessions,’ such as their role as havens from political instability in China, the time has come for China to have full sovereignty over all its territories.” The article further argues that while the old privileges may be retained for the time being due to the ongoing Ten-Year Civil War and the current unstable government, the days of the concessions are numbered (The China Weekly Review Aug 20, 1921, 595). Despite the turbulence and governmental inaction during China’s Ten-Year Civil War, The Review maintained an optimistic outlook on the issue of extraterritoriality, firmly believing that it would and should be abolished soon.

Providing background for news events and issues is a hallmark of professional journalism as taught in universities, and represents a rebuke to the sensationalism of Yellow Journalism. The Review helped disseminate this reportorial style in China after its establishment in Shanghai in 1917. At that time, Westerners had a well-established presence, and their newspapers had become more assertive in commenting on and criticizing Chinese domestic affairs. The Review, imitated by more and more news publications, garnered wide public attention on the issue of extraterritoriality both in China and abroad.

2 Humanizing Abused “Extraterritoriality”

Although extraterritoriality is a complex and serious issue, The Review humanized its coverage by connecting it to specific, compelling cases. This allowed readers to understand the history and current state of extraterritoriality in China, making the topic more engaging. To enrich its coverage, The Review incorporated specific cases and specific examples into its stories on extraterritoriality. The Review frequently highlighted how colonizers abused their special rights in China. It closely followed opium smuggling and gambling, two issues directly linked to the abuse of extraterritoriality.

In June 1929, The Review reported on a raid of a gambling house in the International Settlement, where police arrested approximately 300 people of various nationalities. However, due to the diverse legal systems enforced by different countries within the settlement, the gamblers faced varying outcomes: Chinese gamblers were fined or imprisoned under Chinese law, while British gamblers were prohibited to go to any gambling establishments under a law dating back to the reign of King Henry VIII. Ironically, although operating a gambling establishment was illegal in both China and Britain at the time, the house remained open due to the protection of British authorities who controlled the Municipal Council of the International Settlement in Shanghai (The China Weekly Review, Jun 29, 1929, 186–188).

The Review exposed the Ezra family’s opium business in Shanghai and covered a subsequent lawsuit involving the family. N. E. B. Ezra claimed that he owned 180 cases of opium being shipped from Constantinople for Vladivostok (Haishenwai) by a Japanese steamer. The Ezra family was from Britain and made its fortune from the opium trade long before. The trade was forced underground when it became illegal all globally.

Some of the 180 cases of opium were seized by police in the Shanghai International Settlement. To avoid legal consequences, Mr. Ezra claimed to be Spanish in the International Settlement’s Mixed Court, citing a statement that “a Spanish Consul in Shanghai claims that he can actually confer Spanish protection and jurisdiction upon a British-born Jew.” In his initial court statement, Mr. Ezra stated that he was born in India, his ancestors were Spanish centuries earlier, his father and grandfather were born in Baghdad, and he did not know his great-grandfather’s birthplace. Ironically, Mr. Ezra had been prominent for years as an active anti-opium worker. In fact, the Ezra family continued to participate in the illegal trade of opium, morphine, and other drugs. The family was part of an international opium ring with operations in the Near East, China, Japan, and even Switzerland. Before reaching its intended destination, most of the smuggled opium disappeared upon arrival at Chinese seaports, where it was sold illicitly (The China Weekly Review, Mar 28, 1925, 94).

Coincidentally, this case was heard in the International Mixed Court at Shanghai concurrently with the International Anti-Opium and Anti-Narcotics Conferences held under the auspices of the League of Nations in Geneva. The Review reprinted part of an editorial written by its chief editor, John B. Powell for The China Press:

During the course of the Geneva Opium Conference, Dr. Sao-Ke Alfred Sze, Chinese Minister to the United States and head of the Chinese Delegation at the Conference, stated in the course of an address that the Chinese Government was handicapped in its efforts to prevent the smuggling of opium into China, by foreigners taking advantage of technicalities in their extraterritorial rights. When this statement was cabled to the Far East, there was a great outcry on the part of a certain section of the foreign press to the effect that the Chinese Minister was camouflaging the real situation and taking advantage of the occasion to put over a plea for the abolition of the extraterritorial treaties. Now in spite of the real motives of Dr. Sze, we have a case at present before the public in Shanghai which indicates that the Chinese Delegate was on the right track. In this case, a man, who previously had been a British subject, was alleged to have had some connection with an opium case, but when he appeared before the International Mixed Court, he announced that he had changed his nationality to Spanish and refused to discuss his nationality until he had interviewed the Spanish Consul. Whether Spanish law is more lenient on this subject than is British law, we do not know, but at least to an outsider it appears strange that a foreigner could switch his nationality about the map of the world in this way, and do it almost overnight, so to speak. (The China Weekly Review, May 1, 1926, 217)

Along with two other American news professionals in China, Powell was sued for libel by N. E. B. Ezra for exposing the family’s opium business. Though the court finally judged that the three American news professionals were innocent, they were forced to leave The China Press, the above-mentioned daily newspaper of American style based in Shanghai.

By telling compelling stories about the serious topic of extraterritoriality, The Review established its reputation at the time as a more neutral and independent publication than most other newspapers established by Westerners in China. This characteristic is typical investigative report and a counter to sensationalism while digging deeper into the extremely complicated issue.

3 Presenting Transnational Perspectives

In addition to reflecting China’s efforts to abolish extraterritoriality, The Review also presented the diverse viewpoints of the Treaty Powers, particularly the positions of the American and British governments. Readers gained a clear understanding of the issue from multiple international perspectives.

Although calls for abolishing foreigners’ special rights in China intensified from the beginning of the 20th century, a nationwide campaign promoting abolition did not emerge until the 1920s due to persistent domestic instability. However, the Powers would not easily give up the special rights that they enjoyed for decades. They also maneuvered against each other regarding the retention or abolition of extraterritoriality in China, particularly as Japan usurped much more power, which significantly hampered progress towards abolition. None of them were willing to relinquish their special rights in China, but they feigned support for abolition to pressure other powers and cultivate favor with China. In April 1926, The Review quoted British writer Putnam Weal’s article titled “Why China Sees Red” as follows:

The Peking author then makes the startling statement that in order to further consolidate her relations with China, and her interests in China, and for the purpose of ham-stringing the Americans and Europeans, “Japan is preparing to make concessions where it will least inconvenience her and at the same time most inconvenience others.” This great concession which Japan is preparing to relinquish, should it be necessary, is, in Mr. Weal’s opinion, Extraterritoriality. (The China Weekly Review, Apr 10, 1926, 134–135)

In Mr. Weal’s view, Japan knew well that abolishing extraterritoriality would do great damage to British interests in China. However, he argued that the judicial system Britain had established in various Treaty Ports in China not only protected British interests, but also the interests and security of numerous businesspeople from various companies registered with British consuls in those ports. However, Japan’s situation in China is different from other Powers according to The Review:

Japanese investments, however, would not suffer by an abrogation of extraterritoriality, in his (Mr. Weal’s) opinion, because Japan’s one big investment – … Railway Company and the railway towns within its zone – is protected by special capitulations and by troops. In consequence of Japan’s peculiarly favorable position, Mr. Weal’s hazards the opinion that Japan may, regardless of the action of the International Commission of Jurists which is now investigating the subject of Extraterritoriality, as provided by the Washington Conference, act on her own initiative, no matter what the others may do “so that the Chinese people may be encouraged to believe in their (the Japanese) brotherly love.” (The China Weekly Review, Apr 10, 1926, 134–135)

The Review once reported that “there are three possible ways of settling the question of ‘extraterritoriality’ in China: immediate, outright relinquishment of consular jurisdiction; the Turkish plan; and the Siam plan”. Compared to the first solution, both the “Turkish plan” and the “Siam plan” are incomplete or gradual abolition of extraterritoriality, of which most Treaty Powers would approve at that time. On April 29th, 1929, the new China National Government led by Kuomintang sent diplomatic notes to the Powers suggesting an early consideration of the question of relinquishment of foreign consular jurisdiction in China. The “Notes” sent to the various “Powers” were not identical, but the American, British and French Governments received “notes” with exactly the same content (The China Weekly Review, May 11, 1929, 444).

The Review reprinted two news reports from the United Press and the Associated Press published on June 3rd and 4th in 1929 respectively. The two American-based news agencies analyzed the major obstacles to abolishing extraterritoriality in China. They both predicted that any action by the American government would be ineffective until other Treaty Powers took similar action, and therefore, no significant change regarding the issue was expected. Therefore, The Review argued that the United States opposed the immediate relinquishment of American privileges in China, but would consider it once China’s new judicial system could provide sufficient guarantees to Americans in the country (The China Weekly Review, Jun 8, 1929, 51, 53).

Although the American government was the first to respond to the Chinese Government’s notes to the Treaty Powers, it insisted that the United States would only relinquish its special rights concurrently with all other Powers. This was confirmed in a formal note from U.S. Secretary of State J. V. A. MacMurray to Dr. Chengting T. Wang, the Chinese Minister for Foreign Affairs. The Review also reprinted the full text of this letter in the last issue of Volume 49 (The China Weekly Review, Aug 31, 1929, 7–8). One week later, The Review also reprinted the full text of the note that Miles W. Lampson, the representative of British government in China, sent to Dr. Chengting T. Wang. In the note, Mr. Lampson emphasized the “painful” effort Great Britain had expended in establishing extraterritoriality in the treaty ports. He countered China’s Government’s request by using typical diplomatic language with a threatening tone:

His Majesty’s Government would however observe that the promulgation of codes embodying Western legal principles represents only one portion of the task to be accomplished before it would be safe to abandon in their entirety the special arrangements which have hitherto regulated the residence of foreigners in China. In order that those reforms should become a living reality, it appears to His Majesty’s Government to be necessary that Western legal principles should be understood and be found acceptable by the people at large no less than by their rulers, and that the courts which administer these laws should be free from interference and dictation at the hands not only of military chiefs but of groups and associations who either set up arbitrary and illegal tribunals of their own or attempt to use legal courts for the furtherance of political objects rather than for the administration of equal justice between Chinese and Chinese, and Chinese and foreigners. Not until these conditions are fulfilled in a far greater measure than appears to be the case to-day will it be practicable for British merchants to reside, trade and own property throughout the territories of China with the same equality of freedom and safety as these privileges are accorded to Chinese merchants in Great Britain. Any agreement purporting to accord such privileges to British merchants would remain for some time to come a mere paper agreement to which it would be impossible to give effect in practice. Any attempt prematurely to accord such privileges would not only be of no benefit to British merchants but might involve the Government and people of China in political and economic difficulties.

So long as these conditions subsist there appears to be no practicable alternative to maintaining, though perhaps in a modified form, the treaty-port system that has served for nearly a century to regulate intercourse between China and British subjects within her domain. (The China Weekly Review, Sep 7, 1929, 47)

Clearly, in response to the request to abolish extraterritoriality in China, both the UK and the U.S. responded diplomatically but without genuine commitment, as they were unwilling to relinquish the privileges they had enjoyed for nearly a century. The Review presented the differing perspectives of the Chinese government and the various Treaty Powers on this issue. By doing so, it avoided one-sidedness in its report on the issue of extraterritoriality.

4 Differentiating from British Editors

The two founders of The Review, Thomas F. Millard and John B. Powell, were both from Missouri, a Midwestern American state. Their background influenced their journalistic approach. Millard and Powell imbued The Review with a critical perspective towards both Britain and Japan, recognizing Japan as a growing competitor to the United States in the Pacific. Millard defined American overseas expansion from the end of the 19th century as the “American Thesis,” contrasting it with the “Colonial Thesis” he ascribed to European powers in their global expansion (Millard 1906, 119). This can be seen in most of The Review’s editorials on some important issues concerning the Powers’ interests in China including “extraterritoriality.”

By the beginning of the 20th century, some Americans in China grew dissatisfied with their perceived role as subordinate to the British. They began to compete with the British in various fields, including the newspaper industry in China. Unlike its British competitors, The Review engaged with the long-standing issue of extraterritoriality, strongly advocating for its abolition. This stance can be traced back to The Review’s early years, when its publisher, John B. Powell, engaged in a significant debate on this issue with The North China Daily News, also based in Shanghai and often referred to as the “British organ” in the Far East.

As early as in May 30th, 1925, Powell and some other American news professionals in China “began to write that the old order in China had changed, and predicted the early restoration of tariff autonomy and the revision of all treaties concerning extraterritorial rights” (The China Weekly Review, May 15, 1926, 285) Initially, these American news professionals faced strong opposition from the business communities their newspapers served. However, The Review maintained that changes in the foreign presence in China were inevitable, and that businesspeople would benefit most by acknowledging this reality (The China Weekly Review, May 15, 1926, 285).

In contrast, The North China Daily News, as an organ of the British government, held the opposing view that China was not ready for change and that maintaining the status quo was in the best interests of both China and the Treaty Powers. From that point on, John B. Powell engaged in a prolonged editorial debate with The North China Daily News, represented by one of its editors-in-chief, O. M. Green. In fact, the U.S. government generally aligned its foreign policy towards China with that of the British government. The representatives of the two governments in Beijing generally acted in concert regarding China. As editor of an American newspaper in Shanghai, Powell’s concerned attitude towards China contrasted sharply with the more rigid and traditional stance often held by the British.

Upon the Chinese National Government’s 1928 request for the relinquishment of special rights, The North China Daily News and most other Western newspapers in China instinctively adopted a dismissive attitude. The Review criticized this collective rejection in an editorial paragraph, labeling those news professionals, mostly British, as “die-hards”:

Foreigners of the die-hard type have always argued that extraterritoriality should not be relinquished until China is in a position to provide protection equivalent to that extended to Chinese in foreign countries. The Chairman of the British Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai made this point in a recent address on this subject. This would be an ideal situation from the standpoint of the die-hard, but when he makes this demand he forgets that all of the remaining extraterritorial treaties will expire before 1934 and that no foreign government wants to drift into a non-treaty status. The American treaty pertaining to extraterritoriality expires in 1932, only three years in the future… (The China Weekly Review, Jun 15, 1929, 97)

For years, The North China Daily News focused its criticism on China’s tariff autonomy. When British delegates in Beijing agreed to China’s restoration of this sovereignty, the editors of the daily newspaper reacted with strong disapproval. They published an article in the newspaper titled “The Great Betrayal,” accusing the delegates of “surrendering ignominiously” to the Chinese. Later on, the British editors treated the question of extraterritorial rights with the same stubborn opposition (The China Weekly Review, May 15, 1926, 285).

These conflicting stances significantly influenced relations between China and the two powers. By this comparison and contrast, The Review persuaded more and more Chinese intellectuals to believe that Britain was adversarial, while America was friendly to China.

5 Conclusions

The China Weekly Review marks a turning point in the history of western journalism in China mainly because it was established and run by the first batch of news professionals from the West. Led by Millard and Powell and based on The Review, more and more American professionally educated journalists came to China, and formed a team of professional journalists with “Missouri mafia” as its core. Most of these professionals had Missouri background of having graduated from MU J-School or coming from Show-me State. In the huge background of American overseas expansion starting from the end of the 19th century, The Review’s team of professional journalists helped practice and disseminate American journalistic professionalism in China, which can be seen as part of Americans’ endeavor of promoting its values all over the world (English 1961, 2–3). However, in covering some big issues, such as “extraterritoriality”, these professionally educated and trained journalists managed to take advantage of various professional reportorial means Even though The Review’s stance shifted in the 1940s, by resorting to its freshly innovated journalistic professionalism in early 20th century, American news professionals outperformed most other foreign news practitioners in China, and therefore produced huge influence on both news as an industry and journalism as a profession in universities.

References

English, Earl F. 1961. Cold War Role for Journalists. Columbia: School of Journalism, University of Missouri.Search in Google Scholar

Koo, Vi Kyuin Wellington. 1912. The Status of Aliens in China. New York: Columbia University Press.Search in Google Scholar

Loo, W. K. 1937. “History of extraterritorial rights in China.” The China Weekly Review 80 (8). Western Historical Manuscripts Collections of Missouri University.Search in Google Scholar

Lu, Qiguo 陆其国. 2009. Jixing de fanrong: zujie shiqi de Shanghai 畸形的繁荣——租界时期的上海 [The Abnormal Prosperity: Shanghai during the Concessions.]. Shanghai: Oriental Publishing Center.Search in Google Scholar

Mackinnon, Stephen R., and Oris Friesen. 1992. China Reporting: An Oral History of American Journalism in the 1930s and 1940s. Berkeley: University of California Press.Search in Google Scholar

Millard, Thomas F. 1906. “The powers and the settlement.” Scribner’s magazine 39 (4): 109–120.Search in Google Scholar

The China Weekly Review. 1921. “Editorial Paragraphs.” The China Weekly Review 17 (12): 595. Western Historical Manuscripts Collections of Missouri University.Search in Google Scholar

The China Weekly Review. 1925. “Opium and the Extraterritoriality Problem.” The China Weekly Review 32 (4): 93–94. Western Historical Manuscripts Collections of Missouri University.Search in Google Scholar

The China Weekly Review. 1926a. “Japan and the Extraterritoriality Question.” The China Weekly Review 36 (6): 134–135. Western Historical Manuscripts Collections of Missouri University.Search in Google Scholar

The China Weekly Review. 1926b. “Judge Purdy’s Decision in the Ezra Libel Action.” The China Weekly Review 36 (9): 217. Western Historical Manuscripts Collections of Missouri University.Search in Google Scholar

The China Weekly Review. 1926c. “The British vs. The American Editors.” The China Weekly Review 36 (11): 285. Western Historical Manuscripts Collections of Missouri University.Search in Google Scholar

The China Weekly Review. 1929a. “British Reply to China’s Note On Extraterritoriality.” The China Weekly Review 50 (1): 47. Western Historical Manuscripts Collections of Missouri University.Search in Google Scholar

The China Weekly Review. 1929b. “China’s Demand for Extraterritoriality.” The China Weekly Review 48 (11): 444. Western Historical Manuscripts Collections of Missouri University.Search in Google Scholar

The China Weekly Review. 1929c. “Full Text of America’s Reply to China’s Note Requesting the Abolition of Extraterritoriality.” The China Weekly Review 49 (14): 7–8. Western Historical Manuscripts Collections of Missouri University.Search in Google Scholar

The China Weekly Review. 1929d. “Gambling and the Extraterritorial Question.” The China Weekly Review 49 (5): 186–188. Western Historical Manuscripts Collections of Missouri University.Search in Google Scholar

The China Weekly Review. 1929e. “Washington’s Reply on Extraterritoriality.” The China Weekly Review 49 (2): 51–53. Western Historical Manuscripts Collections of Missouri University.Search in Google Scholar

The China Weekly Review. 1929f. “What’s Likely to Happen on Extraterritoriality.” The China Weekly Review 49 (3): 97. Western Historical Manuscripts Collections of Missouri University.Search in Google Scholar

Williams, Sara Lockwood, and Walter Williams. 1961. Sara Lockwood Williams Papers. The Western Historical Manuscripts Collections of Missouri University: https://files.shsmo.org/manuscripts/columbia/C2533.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Improving Interability Attitudes: Examining Positive and Negative Communication Processes

- The Practice of Early American Journalistic Professionalism in China – An Analysis of The China Weekly Review’s Reportorial Coverage on Extraterritoriality in China

- Language and Social Transformation in Nyumbantobhu: A Gendered Perspective

- Commentary

- The Translation and Scholarship of African Literature in China

- Review Article

- Representation of Indian Muslims in Bollywood Cinema: A Scholarly Review

- Book Review

- Bao, Hongwei, and Daniel H. Mutibwa: Entanglements and Ambivalences: Africa and China Encounters in Media and Culture

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Improving Interability Attitudes: Examining Positive and Negative Communication Processes

- The Practice of Early American Journalistic Professionalism in China – An Analysis of The China Weekly Review’s Reportorial Coverage on Extraterritoriality in China

- Language and Social Transformation in Nyumbantobhu: A Gendered Perspective

- Commentary

- The Translation and Scholarship of African Literature in China

- Review Article

- Representation of Indian Muslims in Bollywood Cinema: A Scholarly Review

- Book Review

- Bao, Hongwei, and Daniel H. Mutibwa: Entanglements and Ambivalences: Africa and China Encounters in Media and Culture