Abstract

Integrating intergroup contact theory and communication accommodation theory, this study examined associations between participants’ (N = 780) communication experiences with people with visible physical disabilities (PWVPD) and intergroup attitudes. Findings revealed that accommodative communication functioned as a positive form of intergroup contact. Specifically, perceptions of communication accommodation to PWVPD were positively associated with intergroup attitudes. Additionally, perceived accommodation to PWVPD had significant positive indirect associations with positive interability attitudes through anxiety reduction and empathy building. However, nonaccommodative communication behaviors functioned as a negative type of intergroup contact. While communication nonaccommodation did not directly affect intergroup attitudes, nonaccommodative communication from PWVPD had significant negative indirect associations through the same mediators with intergroup attitudes. This study highlights the ways in which positive and negative forms of interability communication influence disability attitudes directly and indirectly through empathy and anxiety.

Population growth, the COVID-19 pandemic, and increased longevity have led to an increase in the number of people with disabilities across the globe (Ives-Rublee and Anona 2023). Globally, over one billion people have a disability that impacts major life activities. Particularly, physical disability, or mobility impairment, represents the most reported disability, affecting approximately one in seven adults in the United States, for example (Okoro et al. 2018). Currently, people with disabilities are the world’s largest demographic minority group (World Health Organization 2023). However, they tend to be regarded in their communities as some of the most disadvantaged (Schmitt et al. 2014; United Nations 2022). Although there is an increased concern for people with disabilities in general due to social justice movements, little scholarly communication research has been devoted to this growing but stigmatized population (cf. Lash 2022; Ryan, Anas, and Gruneir 2006).

Scholars consider people with disabilities to be a unique social or cultural group and thus view communication between people with and without disabilities as intercultural communication (see Braithwaite and Braithwaite 2003; Emry and Wiseman 1987). Braithwaite and Braithwaite (2003) explain that

people with disabilities develop certain unique communicative characteristics that are not shared by the majority of nondisabled individuals in U.S. society. In fact, except for individuals who are born with disabilities, becoming disabled is similar to assimilating from being a member of the nondisabled majority to being a minority culture. That is, the onset of a physical disability requires learning new ways of thinking and talking about oneself and developing ways of communicating with others. (167)

This highlights that a cultural lens is applicable when studying disability because people with disabilities are a distinct cultural group with unique communication practices. Therefore, interability communication, which is communication between people with and without disabilities (Ryan et al. 2005), can be understood as intercultural communication because it involves understanding how group identity, experiences, and adaptive communication patterns emerge within the context of cultural differences and societal norms. Disability, in this sense, constitutes a cultural identity that shapes – and is shaped by – communication. Similar to those in other marginalized cultural groups, people with disabilities continue to be disadvantaged economically, communicatively, socially, and relationally due to prevalent and negative disability-stereotypes of being perceived as burdensome, unproductive, lazy, and helpless (Ryan et al. 2005). Negatively stereotyping people with disabilities results in inappropriate and ineffective interability communication and negative attitudes toward disability or people with disabilities in general (Allen 2023). Consequently, a majority of people with disabilities reported that their primary friendships involved other people with disabilities (Sense 2024). Additionally, most people without disabilities feel uncomfortable speaking to people with disabilities due to uncertainty and anxiety, leading to communication avoidance, which is a behavioral form of prejudice (Sense 2024). According to Allport (1954), outgroup ignorance and unfamiliarity result in intergroup prejudice. Hence, guided by intergroup contact theory, recent interability contact research has demonstrated the influence of positive communication or contact with specific persons with (in)visible physical disabilities in improving disability attitudes and reducing disability-stereotyping (Byrd and Zhang 2019; Byrd, Zhang, and Gist-Mackey 2019). From the perspectives of people without disabilities, this study contributes to the growing literature on disability prejudice reduction by focusing on the role played by interability communication (non)accommodation between people without disabilities and people with visible physical disabilities. Specifically, we are contributing to the theoretical intersection of intergroup contact (Brown and Hewstone 2005) and communication accommodation (Giles 2016) scholarship by examining the role specific forms of positive and negative intergroup contact play in reducing or exacerbating interability bias. In the following sections, intergroup contact theory and communication accommodation theory are reviewed, including discussion of the major dependent variable.

1 Intergroup Contact Theory

Intergroup contact theory explains that frequent and positive engagement in intergroup contact can reduce bias between in- and outgroups and improve intergroup relations (Pettigrew 1998). Intergroup contact theory is a guiding theoretical framework of intergroup communication (Pettigrew 1998; Pettigrew et al. 2011). Support for intergroup contact theory has been found in many intergroup contexts demarcated by age, religion, ethnicity, culture, disability, or gender (e.g., Byrd and Zhang 2019; Zhang et al. 2018). Research in the interability context has shown that contact or communication with participants’ specific outgroup contact who has a disability can reduce prejudice directly and indirectly through the enactment of social support, development of relational solidarity, and reduction of intergroup anxiety (Byrd and Zhang 2019; Byrd, Zhang, and Gist-Mackey 2019). These studies have examined various forms of contact or communicative manifestations of contact, such as communication frequency, quality, self-disclosure, and communication accommodation, in understanding bias reduction and the improvement of intergroup relations in the interability context.

Research from an intergroup contact approach explains several ways in which communication, especially with a specific outgroup member, such as a family member or close friend, can reduce prejudice. Several mechanisms have been examined explaining why contact works, such as gaining knowledge about the outgroup, reducing anxiety, and generating affective ties, which then lead to behavior modifications and changes (Pettigrew 1998; Pettigrew and Tropp 2008). The current study includes behavioral intergroup attitudes, which we conceptualize as future “behavioral intentions toward members of a group,” as the outcome variable (Esses and Dovidio 2002, 1204). Behavioral intergroup attitudes have been examined as a positive outcome of intergroup communication (e.g., Harwood et al. 2005; Imamura, Zhang, and Harwood 2011; Ristić, Zhang, and Liu 2019). People without disabilities’ intergroup attitudes in the interability context are essential since prior research shows that behavioral attitude change or willingness to engage with the outgroup is typically the precursor or the first step to long-lasting affective or cognitive change (Pettigrew 1998; Tropp and Pettigrew 2005). Thus, behavioral intergroup attitudes are included as the major outcome variable.

Intergroup contact researchers have argued that for attitude change to be successful, the encounter must qualify as intergroup, meaning that group membership must be salient (Fox and Giles 1996; Hewstone and Brown 1986). Therefore, participants were asked about their experiences communicating with people with visible, physical disabilities in general. As such, group salience or the awareness and visibility of physical disabilities is more likely to constitute the interaction as intergroup. The following sections outline the present study’s predicting and explanatory variables.

1.1 Communication Accommodation Theory: Positive and Negative Communication Processes

Informed by communication accommodation theory (CAT; Giles 2016), two communication variables are of interest in the current study: specific ways of positively (i.e., accommodative communication) and negatively (i.e., nonaccommodative communication) communicating in interability interactions that may influence behavioral intergroup attitudes. CAT explains how people modify their communication in accommodative and nonaccommodative ways according to interactional, relational, or identity goals. The current study highlights two accommodative behaviors – perceived accommodation and perceived nonaccommodation. Perceived accommodative communication may include linguistic features such as social support, sharing personal thoughts and interests, and positive emotional expression (Hummert 2019). Although specific forms of accommodation can vary depending on the intergroup context, CAT considers communication (non)accommodation as individuals’ “situated and subjective experience” (Gasiorek and Dragojevic 2017, 280) about communication behaviors received from or toward others (Soliz and Giles 2014). Specifically, we conceptualize accommodative communication as participants’ perceptions of their own engagement with people with disabilities using positive, appropriate, other-oriented communication that enhances relational development and communication effectiveness (e.g., Harwood 2000; Hummert 2019). Prior research demonstrates how accommodative communication functions as a type of positive intergroup contact. For instance, people without disabilities’ communication accommodation to a specific outgroup member who has a disability was positively associated with relational solidarity with that person, which, in turn, decreased anxiety and improved intergroup attitudes (Byrd, Zhang, and Gist-Mackey 2019). Hence, we introduce our first hypothesis:

H1:

Participants’ communication accommodation behaviors to people with visible physical disabilities (PWVPD) will be positively associated with positive intergroup attitudes.

We conceptualize nonaccommodative communication as participants’ perceptions of inappropriate and negative communication behaviors received from PWVPD (e.g., Soliz and Giles 2014; Zhang et al. 2018). The nonaccommodative communication behavior highlighted in the current study is when people with disabilities stereotype or perceive people without disabilities as judgmental and prejudicial. With an increased focus on inclusion, diversity, equity, and access, being judgmental or communicating prejudicial attitudes or behaviors, particularly toward marginalized groups, is viewed unfavorably and negatively impacts interability communication and intergroup relations. In other intergroup contexts, members from majority groups have begun expressing concern about being accused of being judgmental or stereotyped as prejudicial toward their minority conversation partners, which also leads to negative physiological and relational outcomes (e.g., Shelton, West, and Trail 2010). This type of communication experience is perceived as nonaccommodative in nature elevating negative emotions and is thus essential to explore when investigating the contact-attitude link (e.g., Fox and Giles 1996; Hewstone and Brown 1986). The items used to measure nonaccommodation from people with visible physical disabilities in the current study, which include stereotyping or perceiving people without disabilities as being judgmental and prejudicial in interability communication, were informed by a preliminary study and are conceptually consistent with CAT (Giles 2016). In addition, these nonaccommodative behaviors echo a prominent nonaccommodative theme uncovered in problematic intergenerational conversations between young and older adults (Williams and Giles 1996). Thus, we asked participants to consider to what extent they are stereotyped or perceived by their disability contact as judgmental or prejudicial in interability communication, which represents nonaccommodative communication.

It is imperative to remember the “situated and subjective” nature of communication accommodation and nonaccommodation. This is vital when conceptualizing and operationalizing communication (non)accommodation (Gasiorek and Dragojevic 2017, 280). In this study, we examine participants’ perceptions of PWVPD’s nonaccommodative behaviors with the hope of providing insight to improve interability communication. While there is general agreement that communication accommodation is a prosocial behavior with myriad positive outcomes (Byrd and Zhang 2023), we include nonaccommodative communication as a type of negative intergroup contact (e.g., Zhang et al. 2018). Intergenerational communication research illustrates how perceived nonaccommodation operates as a type of negative intergroup contact. For instance, when grandchildren perceived their grandparents as communicating nonaccommodatively, there were negative effects on shared family identity, relational solidarity, and attitudes toward older adults (Zhang, Li, and Harwood 2021). Essentially, when communication involves perceived nonaccommodation, group salience is intensified, leading to a variety of negative outcomes such as increased anxiety, reduced willingness to communicate, and increased prejudice (Hewstone 2000). We believe that investigating negative communication is essential since the valence of intergroup contact influences intergroup attitudes (Barlow et al. 2012). While this is an initial exploration into this specific nonaccommodation behavior in the interability context, it is theoretically supported and practically meaningful. Therefore, the following hypothesis is introduced:

H2:

Participants’ perceptions of PWVPD’s communication nonaccommodation toward them will be negatively associated with positive intergroup attitudes.

1.2 Emotions as Explanatory Mechanisms Between (Non)Accommodation and Intergroup Attitudes

Intergroup contact research has established that the arousal of anxiety common in intergroup communication is detrimental to intergroup relations (Stephan 2014; Stephan and Stephan 1985). Thus, anxiety has been a major pathway in understanding the contact-prejudice association (Pettigrew and Tropp 2008). As an affective construct, intergroup anxiety refers to “apprehensive, distressed, uneasy” feelings experienced when anticipating or engaging in communication with outgroup members (Stephan 2014, 240). Previous research has shown that experiencing contact-based interability anxiety is negatively associated with intergroup attitudes (Byrd and Zhang 2019). To put it simply, reducing anxiety is imperative to improving intergroup attitudes, hence anxiety is included as an explanatory variable.

Intergroup contact theorists have argued for the importance of examining positive intergroup emotions such as intergroup empathy (Johnston and Glasford 2017). Intergroup empathy, which is also an affective construct, refers to people without disabilities’ other-oriented feelings of sympathy and concern for people with disabilities developed in interability communication (e.g., Davis 1983). Developing empathy enables people to relate to and consider outgroup members in ways that may promote cooperation and ingroup categorization rather than intergroup conflict and separation (Konrath, O’Brien, and Hsing 2011). Essentially, positive communication with people with disabilities may provide participants better opportunities to develop understanding and empathetic concern for people with disabilities. This empathetic concern may, in turn, contribute to improved intergroup attitudes (Vezzali et al. 2016). Researchers have found support for intergroup empathy mediating attitude change in intergroup contact settings with people with AIDs, those who are experiencing homelessness, and in extended intergroup contact involving children (Batson et al. 1997; Pettigrew and Tropp 2008; Vezzali et al. 2016). Therefore, we introduce the following hypothesis:

H3:

Participants’ (a) perceived accommodation to and (b) perceived nonaccommodation received from people with visible physical disabilities will have significant associations with intergroup attitudes indirectly through the parallel mediators of intergroup anxiety and empathy.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and Procedures

Participants (N = 780) who identified as not having any disabilities were recruited from CloudResearch Prime Panels, a leading platform for recruiting participants for surveys and online research. The survey was completed through Qualtrics, an online data collection tool. When beginning the survey, the term “visible physical disability” was defined as “a physical disability or chronic condition that is immediately noticed by an observer” (e.g., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2024b). Participants were asked if they had experience communicating with any people with visible physical disabilities (PWVPD). If participants answered yes, they were asked to consider their communication experiences with PWVPD while completing the questionnaire. Demographic information, including information about participants’ sex, ethnicity, age, and educational level, can be found in Table 1.

Demographics.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

|

|

||

| Men | 380 | 49.7 |

| Women | 400 | 51.3 |

|

|

||

| Ethnicity | ||

|

|

||

| White | 655 | 84 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 47 | 6 |

| Sub-Saharan Africans/African American | 35 | 4.5 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 29 | 3.7 |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 6 | 0.8 |

| Other | 8 | 1 |

|

|

||

| M | SD | |

|

|

||

| Age | 46.97 | 17.74 |

| Educational level | 14.95 | 3.75 |

Given the sensitive nature of some of our major measures (e.g., perceptions of communication nonaccommodation received from PWVPD), we took steps to reduce social desirability bias. First, following Institutional Review Board protocol, we informed participants that there were no correct or incorrect answers and that we were simply interested in their honest answers about their communication experiences with people with disabilities. In addition, participants were informed that no direct identifiers were collected, they should not list their names in any place in the survey, and that data from this study would be reported in aggregate, not individually. In the following section, the major measures are introduced. Response options for the major measures were 7-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

2.2 Major Measures

2.2.1 Communication Accommodation to PWVPD

Communication accommodation refers to the degree to which participants engage in positive other-oriented accommodative behaviors to maintain and pursue communication with PWVPD in general. The four items (e.g., “I am attentive in conversations with PWVPD,” “I share personal thoughts and feelings with PWVPD”; α = 0.84; M = 5.72, SD = 0.97) formed a reliable scale (e.g., Harwood 2000).

2.2.2 Communication Nonaccommodation From PWVPD

Communication nonaccommodation refers to the degree to which participants perceived receiving nonaccommodative communication behaviors from people with visible physical disabilities. Specifically, participants reported the degree to which they received communication from PWVPD stereotyping or accusing them as being judgmental and prejudicial in communication with PWVPD. The two items (i.e., “In my communication with PWVPD, they frequently stereotype me as being judgmental,” “In my communication with PWVPD, they frequently view me as prejudicial”; α = 0.93; M = 2.96, SD = 1.6) were informed by a preliminary study[1] examining retrospective reports of communication nonaccommodation in the interability context (e.g., Harwood 2000).

2.2.3 Intergroup Anxiety

Intergroup anxiety measured the degree to which participants experienced anxiety during or in anticipating interaction with PWVPD. Specifically, participants were asked how they would feel if they were the only person without a disability communicating or interacting with PWVPD. The six items (e.g., “I feel anxious,” “I feel awkward”; α = 0.88; M = 2.85, SD = 1.26) formed a reliable scale (e.g., Stephan 2014).

2.2.4 Intergroup Empathy

Six items adapted from Davis (1983) were used to measure the degree to which participants experience feelings of sympathy and concern for PWVPD. The six items (e.g., “I consider myself soft-hearted toward PWVPD,” “I have tender, concerned feelings for PWVPD”; α = 0.84; M = 5.54, SD = 0.90) formed a reliable scale.

2.2.5 Intergroup Attitudes

Intergroup attitudes, which is the likelihood that participants would engage in various inclusive behaviors with PWVPD in the future (e.g., “I am willing to accept PWVPD as my neighbors,” “I am willing to accept PWVPD as my close friends”; α = 0.92; M = 5.79, SD = 0.96) was measured with seven items (e.g., Cooke 1978).

2.3 Covariates

We measured general interability communication frequency as a covariate, which is a typical variable included in intergroup contact research. Adapted from Spencer-Rodgers and McGovern (2002), the items for communication frequency (α = 0.92; M = 3.81, SD = 1.52) measured how often participants do things socially, initiate conversations, and engage in communication with PWVPD with three 7-point Likert (1 = never, 7 = daily) items. Participants’ age and sex were also considered as covariates.

3 Results

We utilized Model 6 of PROCESS with 5,000 bootstrap iterations (Hayes 2022) to conduct regression-based analyses testing direct and indirect effects. When conducting an analysis, one of the communication variables (i.e., perceived accommodation or perceived nonaccommodation) functioned as the independent variable (X), intergroup anxiety and empathy functioned simultaneously as explanatory variables (M1 and M2), and intergroup attitudes functioned as the outcome variable (Y). When one focal independent variable (e.g., communication accommodation) was analyzed, the other predictor variable (e.g., communication nonaccommodation) was entered as a covariate.

Prior to hypothesis testing, correlation analyses were conducted among all major variables, and included participants’ age, sex (0 = female, 1 = male), ethnicity (0 = white; 1 = non-white), and communication frequency to investigate the potential influence of demographic characteristics and general interability communication experiences on our major variables. Correlation testing showed that there was a significant negative association between participants’ age and nonaccommodative communication (b = −0.20, p < 0.001), as well as intergroup anxiety (b = −0.23, p < 0.001). There was a significant positive association between participant’s sex and both nonaccommodative communication (b = 0.12, p < 0.001) and intergroup anxiety (b = 0.20, p < 0.001), but there was a negative association with empathy (b = −0.13, p < 0.001) and intergroup attitudes (b = −0.16, p < 0.001). Communication frequency was positively associated with accommodative communication (b = 0.43, p < 0.001), intergroup empathy (b = 0.16, p < 0.001), and intergroup attitudes (b = 0.28, p < 0.001). There were no significant correlation findings related to ethnicity. Therefore, participants’ age, sex, and communication frequency functioned as control variables in the analysis of our hypotheses. See Table 2 for correlations of the major measures.

Correlations.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Accommodation | ||||

| 2. Nonaccommodation | −0.08* | |||

| 3. Empathy | −0.56*** | −0.15*** | ||

| 4. Anxiety | −0.24*** | 0.56*** | −0.27*** | |

| 5. Intergroup attitudes | 0.52*** | −0.24*** | 0.45*** | −0.39*** |

-

Note. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05; correlations controlled for participant’s age and sex (0 = female, 1 = male).

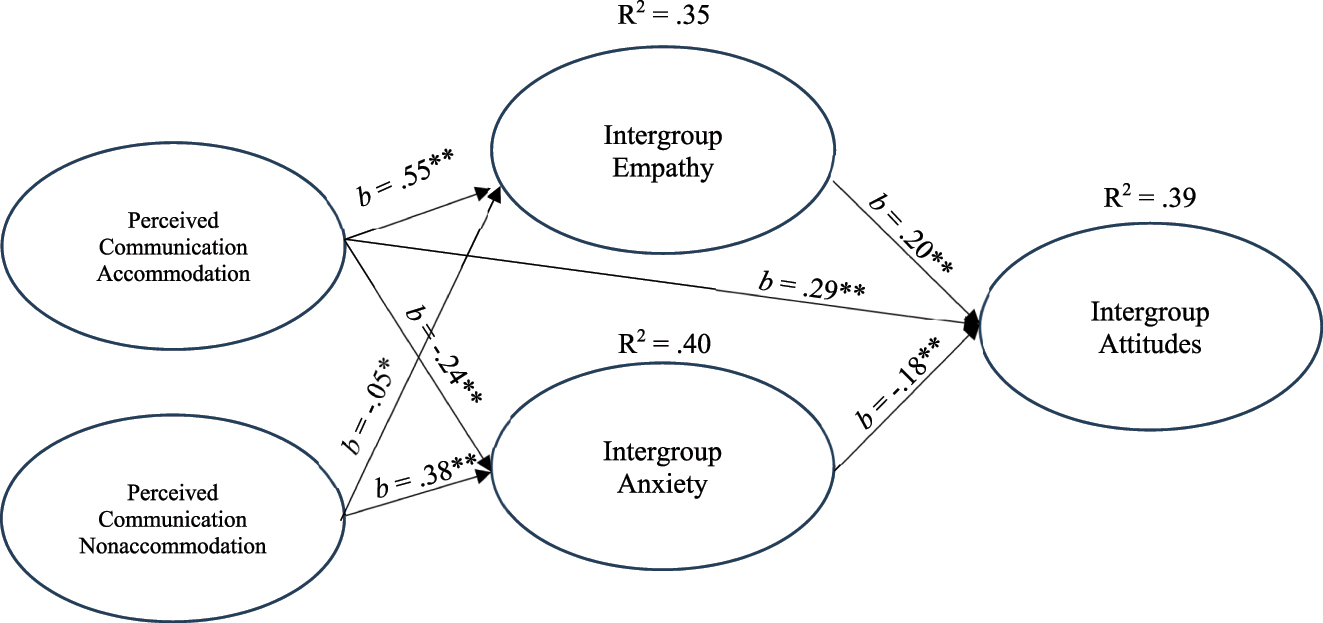

Supporting H1, perceived communication accommodation positively predicted intergroup attitudes. H2 was not supported since communication nonaccommodation did not have a direct association with intergroup attitudes. Supporting H3a, perceived accommodative communication positively influenced intergroup attitudes through intergroup anxiety and empathy in that perceived communication accommodation negatively predicted anxiety, which was then negatively associated with intergroup attitudes. However, communication accommodation positively predicted empathy, which then positively predicted intergroup attitudes. Finally, supporting H3b, perceived communication nonaccommodation negatively influenced intergroup attitudes through each of the two explanatory variables (see Table 3 and Figure 1). Communication nonaccommodation positively predicted intergroup anxiety, thus negatively predicting positive behavioral intergroup attitudes. On the other hand, perceived nonaccommodative communication negatively predicted empathy, which was then positively associated with positive behavioral intergroup attitudes.

Direct and indirect effects of accommodation and nonaccommodation.

| Perceived communication accommodation | Perceived communication nonaccommodation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | SE | 95% CI | Effect | SE | 95% CI | |

| Direct effect | 0.29*** | 0.04 | 0.21, 0.36 | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.08, 0.00 |

| Indirect effect through intergroup anxiety | 0.04** | 0.01 | 0.022, 0.069 | −0.07* | 0.01 | −0.092, −0.048 |

| Indirect effect through intergroup empathy | 0.11*** | 0.02 | 0.06, 0.16 | −0.01*** | 0.01 | −0.021, −0.004 |

-

Note. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Direct and indirect effects of communication variables on intergroup attitudes through empathy and anxiety. Note. **p < 0.001; **p < 0.01. Only significant paths reported.

4 Discussion

By integrating intergroup contact theory (Brown and Hewstone 2005) and communication accommodation theory (Giles 2016), this study investigated the role of interability communication, intergroup anxiety, and empathy in improving positive intergroup attitudes. Supporting our predictions, communication accommodation functioned as a positive type of intergroup contact influencing intergroup attitudes directly and indirectly through both intergroup anxiety and empathy. Communication nonaccommodation, however, did not have a significant direct effect on intergroup attitudes, but decreased positive intergroup attitudes by increasing intergroup anxiety and decreasing empathy. Our findings show the value in integrating intergroup contact theory and communication accommodation theory in the interability context and have several major theoretical and practical implications.

Most intergroup contact research demonstrates the importance of frequent, positive contact in reducing intergroup bias (Pettigrew and Tropp 2008; Pettigrew et al. 2011). As a result, we lack information about the specific communicative dynamics that constitute frequent and positive contact. Harwood et al. (2013) and Tropp, Ulug, and Uysal (2021) specifically emphasized the importance of examining communication content, including positive and negative communication content in understanding intergroup relations. As communication scholars, we too believe it is important to focus on specific communication processes (beyond general frequent and positive contact) to understand how positive communication facilitates bias reduction. Hence, in the current study, we measured both positive and negative manifestations of intergroup communication. Our measures of communication accommodation and nonaccommodation are theoretically informed by communication accommodation theory; however, future studies should continue to test the validity of these measures. For example, there may be subtypes of accommodative (e.g., identity support) and nonaccommodative (e.g., face threatening communication) communication in interability interactions that play an important role in intergroup relations.

By including specific types of communication content as our independent variables, this study furthers intergroup theorizing by establishing communication accommodation toward others as a positive way of communicating that provides beneficial insights into interventions aimed at improving intergroup relations. Here, communication accommodation improved intergroup attitudes directly and indirectly by reducing anxiety and increasing empathy. Specifically, when people without disabilities are supportive, attentive, and disclosing in their communication to people with visible physical disabilities, there are positive outcomes. By including communication accommodation theory in this intergroup contact study, our findings provide helpful insights into specific communication moves that are particularly beneficial in the interability context. Echoing Trzeciak and Mazzarelli (2022), we emphasize the power of accommodation toward others for improving wellbeing, resilience, and professional success.

However, the opposite pattern was found for communication nonaccommodation. When people without disabilities felt that people with visible physical disabilities viewed them as judgmental and prejudicial, it had negative outcomes. Research shows that “individuals fear that prejudiced behavior on their part will lead to social censure or, worse, rejection” (Trawalter et al. 2012, para. 2). Essentially, concern that you are being viewed as prejudicial, or to a lesser degree judgmental, is a stressful process with real consequences. Our findings illustrate that these concerns regarding being viewed as judgmental or prejudiced in interability interactions elevate intergroup anxiety, lower empathy, and reduce positive intergroup attitudes. The inclusion of this specific form of nonaccommodation is a theoretical contribution allowed by integrating communication accommodation and intergroup contact theories. A majority of intergroup contact research focuses on the role of positive contact in reducing intergroup prejudice. However, research has demonstrated the importance of including negative communication processes in intergroup contact research because negative contact predicts increased prejudice more than positive contact reduces prejudice (Barlow et al. 2012). While this is an initial exploration into this specific form of communication nonaccommodation in this context, future work is necessary. It is reasonable to assume most people aim to communicate in non-prejudicial ways, and future work should explore the motivations behind communicating or willingness to communicate in non-prejudicial ways. For instance, research from a communication accommodation framework should explore motives and attributions and whether majority group members’ attempts to communicate non-prejudicially are motivated by their desire to avoid being negatively evaluated or are in line with their egalitarian views.

Essentially, communication nonaccommodation operated as a type of negative contact. When interpreting these findings, we should be mindful that this is the majority group’s perspective of a minority group’s communication behaviors. People without disabilities’ perceptions of received nonaccommodation could reflect not knowing how to engage with people with disabilities, since further exploration into communication frequency indicates that the mean is below the midpoint of the scale (t(734) = −3.45, p < 0.001, 95 %CI = −0.20, −0.06). Essentially, our participants reported that they are not frequently interacting or communicating with people with disabilities. However, the associations between communication nonaccommodation and intergroup emotions (i.e., anxiety and empathy) illustrate the negative social and behavioral consequences of this type of communication nonaccommodation in the interability context. Altogether, this highlights the importance of competent communication from both parties and appropriate intergroup dialogue in developing relationships and mutual understanding and improving intergroup relations. It is important to remember that research from an intergroup contact perspective is motivated to improve interactions between in- and outgroups and thus reduce biases (Tropp and Pettigrew 2005). As a result, most contact research puts the responsibility on majority group members, people without disabilities in this case, to improve communication and enhance intergroup relations (e.g., Pettigrew and Tropp 2008). However, this means that the perspective of minority group members has largely been overlooked (cf. Barlow et al. 2013; Byrd and Zhang 2023). Our findings demonstrate that both groups (people with and without disabilities) must work together to engage in positive, competent communication that can increase empathy, reduce intergroup anxiety, and improve intergroup relations in the disability context. Future research should aim for a “holistic view of intergroup contact” (Barlow et al. 2013, 4) to investigate majority and minority individuals’ communication and attitudes in efforts to improve intergroup relations.

In accordance with intergroup contact theorizing, our findings confirm the importance of lowering anxiety to improve intergroup relations and establish empathy as an important positive mechanism in this context. Echoing previous intergroup contact research, results revealed that reducing intergroup anxiety is essential to improving intergroup relations. This study provides both hope and challenges for interability communication. First, positive communication (i.e., communication accommodation) has the ability to reduce intergroup anxiety – this is good news for interability communication. However, the negative manifestation of communication (i.e., communication nonaccommodation) was a powerful predictor of anxiety, and the positive association between the two variables is concerning. In the interability context, members from the majority group must focus their energy on engaging in positive, inclusive communication behaviors so that anxiety can be reduced, and intergroup relations can be improved.

Finally, intergroup empathy functioned as a positive explanatory mechanism in improving intergroup relations. We found that communication (i.e., accommodative communication) resulted in increased intergroup empathy and intergroup empathy increased participants’ behavioral intergroup attitudes. Essentially, when people without disabilities engage in positive interability communication, they develop empathetic concern for people with disabilities in general. Developing empathy for an outgroup (i.e., people with disabilities) then promotes cooperation and enhances intergroup relations. Altogether, by including intergroup empathy as an explanatory mechanism, the current study illustrates that developing empathetic concern for outgroup members has positive benefits and provides evidence that intergroup empathy mediates attitude change in the interability context. There are two specific aspects related to the design of the study that are essential to keep in mind when discussing findings related to intergroup empathy. First, empathy is measured affectively or emotionally as feelings of sympathy and concern for people with disabilities (e.g., Davis 1983; Konrath, O’Brien, and Hsing 2011). Future research should also explore cognitive manifestations of empathy, such as perspective-taking, to further understand the role of this multi-dimensional construct in interability communication. Second, this study is from the perspective of people without disabilities. People with disabilities are oftentimes stereotyped as “pitiful” (e.g., Ryan et al. 2005). Therefore, people without disabilities considering themselves to be empathetic may be viewed as overaccommodative or inappropriate by people with disabilities. Future interability communication research should consider the perspective of people with disabilities when exploring intergroup empathy.

To summarize, this study contributes to the theoretical intersection of communication accommodation and intergroup contact theories in several ways. First, previous interability contact research has investigated the contact-attitude association when considering people without disabilities’ communication with one specific outgroup member. This study contributes to the literature by exploring perceptions of communication with the outgroup overall or in general. Second, by incorporating specific positive and negative manifestations of interability contact, we have gained a more thorough understanding of what actually happens during contact that reduces (or increases) intergroup prejudice. Third, our findings demonstrate the critical importance of intergroup empathy in improving intergroup attitudes. Altogether, this emphasizes the importance of integrating communication accommodation theory and intergroup contact theory (see Zhang, Li, and Harwood 2021).

These theoretical advancements also shed light on important practical implications for interability communication. Researchers, practitioners, and individuals should focus their attention on ways to incorporate positive communication and intergroup emotions, including communication accommodation and empathy, into people without disabilities’ communication repertoire. Additionally, more work needs to be done to understand what communication is perceived as accommodative to people with disabilities (see Byrd and Zhang 2023) to better understand communication content from both perspectives. Just as importantly, we need to do our best to avoid negative interability communication situations as they increase intergroup anxiety and reduce positive intergroup attitudes.

5 Limitations and Future Directions

It is necessary to address limitations that highlight important future research directions. First, since this is a cross-sectional study, our findings represent one side of the story in interability communication. Specifically, similar to most intergroup contact literature, this study explored the majority group perspective (i.e., people without disabilities) since people with disabilities are a stigmatized group and reducing interability prejudice is a priority. However, research shows that minority group members (e.g., people with disabilities) experience high levels of distrust and are more negative about the nature of intergroup relations (e.g., Gaertner and Dovidio 2000). Thus, future studies guided by intergroup contact theory and CAT should focus on the perspective of people with disabilities to gain a more thorough understanding of intergroup contact, (non)accommodation, and prejudice reduction. In addition, a causal relationship between interability communication and prejudice reduction cannot be established since this is a cross-sectional study. Future experimental and longitudinal studies should be conducted to explore this causal relationship. For instance, we emphasize the importance of examining specific interactive dynamics (including accommodation vs. nonaccommodation) during a particular contact episode, which is better suited to an experimental approach.

Appropriate steps were taken to reduce social desirability bias, but we may not exclude social desirability completely given the sensitive nature of some of the items used to measure the major constructs (e.g., “I would feel awkward” communicating with PWVPD). To reduce social desirability and improve ecological validity, we measured nonaccommodation in terms of people with visible physical disabilities viewing participants as judgmental or prejudiced in interability interactions rather than having participants report how often they were judgmental or prejudiced in their communication behaviors. Future projects should explore this construct from other perspectives.

The current study included American participants recruited from CloudResearch Prime Panels, which has been established as a way to collect high quality data (Chandler et al. 2019). Our sample was large, representative in terms of gender, and had more diverse participants than other interability contact studies (Byrd, Zhang, and Gist-Mackey 2019; Byrd and Zhang 2019) in terms of age. However, our participants are primarily White, which must be considered when generalizing the findings of this study. Future research should aim to recruit representative samples and include participants from non-Western countries to better understand the ways in which communication processes can reduce intergroup anxiety, improve empathy, and improve intergroup attitudes. In line with this goal, we highlight the necessity of future research from a transcultural perspective. A cross-cultural study investigating specific communication processes and intergroup emotions that can reduce prejudice would be beneficial theoretically and practically. A transcultural approach would give us a broader understanding of how these processes operate in different cultural contexts and increase our ability to interpret and generalize findings.

6 Conclusions

The United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2024a) recognizes unsatisfying, inappropriate communication behaviors, as well as negative attitudes toward disability as major barriers experienced by people with disabilities. Therefore, communication work is well positioned to improve these outcomes for people with disabilities and future work should continue to prioritize investigation of positive interability communication processes and prejudice reduction. In this study, we have contributed to the theoretical intersection of intergroup contact and communication accommodation scholarship by examining specific positive and negative communication experiences as forms of intergroup contact in understanding how specific communication processes reduce (or exacerbate) interability bias.

Funding source: Office of Research, University of Kansas

Award Identifier / Grant number: Stereotyping and Intergroup Processing Fund

-

Research funding: This project was supported by the University of Kansas Stereotyping and Intergroup Processing Fund.

References

Allen, Brenda J. 2023. Difference Matters: Communicating social identity. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.Search in Google Scholar

Allport, Gordon W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.Search in Google Scholar

Barlow, Fiona Kate, Matthew J. Hornsey, Michael Thai, Nikhil K. Sengupta, and Chris G. Sibley. 2013. “The Wallpaper Effect: The Contact Hypothesis Fails for Minority Group Members Who Live in Areas with a High Proportion of Majority Group Members.” PLoS One 8 (12): e82228. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082228.Search in Google Scholar

Barlow, Fiona Kate, Stefania Paolini, Anne Pedersen, Matthew J. Hornsey, Helena R. M. Radke, Jake Harwood, Mark Rubin, and Chris G. Sibley. 2012. “The Contact Caveat: Negative Contact Predicts Increased Prejudice More than Positive Contact Predicts Reduced Prejudice.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 38 (12): 1629–43, https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212457953.Search in Google Scholar

Batson, C. Daniel, Marina P. Polycarpou, Eddie Harmon-Jones, Heidi J. Imhoff, Erin C. Mitchener, Lori L. Bednar, Tricia R. Klein, and Lori Highberger. 1997. “Empathy and Attitudes: Can Feeling for a Member of a Stigmatized Group Improve Feelings toward the Group?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 72 (1): 105–18, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.105.Search in Google Scholar

Braithwaite, Dawn O., and Charles A. Braithwaite. 2003. “Which is My Good Leg’: Cultural Communication of Persons with Disabilities.” In Intercultural Communication: A Reader, 10th ed., edited by Larry A. Samovar, and Richard E. Porter, 165–76. Belmont: Wadsworth.Search in Google Scholar

Brown, Rupert, and Miles Hewstone. 2005. “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Contact.” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 37, edited by Mark P. Zanna, 255–343. Amsterdam: Elsevier.10.1016/S0065-2601(05)37005-5Search in Google Scholar

Byrd, Gabrielle A., and Yanbing Zhang. 2019. “Perceptions of Interability Communication in an Interpersonal Relationship and the Reduction of Intergroup Prejudice.” Western Journal of Communication 84 (1): 19–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2019.1636131.Search in Google Scholar

Byrd, Gabrielle A., and Yanbing Zhang. 2023. “Cognitive, Emotional, and Behavioral Responses to Interability Communication Styles in the Workplace: Perspectives of People with Disabilities.” Communication Monographs 90 (4): 456–76, https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2023.2213305.Search in Google Scholar

Byrd, Gabrielle A., Yanbing Zhang, and Angela N. Gist-Mackey. 2019. “Interability Contact and the Reduction of Interability Prejudice: Communication Accommodation, Intergroup Anxiety, and Relational Solidarity.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 38 (4): 441–58, https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927x19865578.Search in Google Scholar

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024a. “Common barriers to participation experienced by people with disabilities.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability-barriers.html (accessed May 2, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024b. “Disability Impacts All of Us.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html (accessed July 3, 2024).Search in Google Scholar

Chandler, Jesse, Cheskie Rosenzweig, Aaron J. Moss, Jonathan Robinson, and Leib Litman. 2019. “Online Panels in Social Science Research: Expanding Sampling Methods Beyond Mechanical Turk.” Behavior Research Methods 51 (2019): 2022–38, https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01273-7.Search in Google Scholar

Cooke, Madeline A. 1978. “A Pair of Instruments for Measuring Student Attitudes toward Bearers of the Target Culture.” Foreign Language Annals 11 (2): 149–63, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1978.tb00024.x.Search in Google Scholar

Davis, Mark H. 1983. “Measuring Individual Differences in Empathy: Evidence for a Multidimensional Approach.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 44 (1): 113–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113.Search in Google Scholar

Emry, Robert, and Richard L. Wiseman. 1987. “An Intercultural Understanding of Ablebodied and Disabled Persons’ Communication.” Intercultural Journal of Intercultural Relations 11 (1): 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(87)90029-0.Search in Google Scholar

Esses, Victoria M., and John F. Dovidio. 2002. “The Role of Emotions in Determining Willingness to Engage in Intergroup Contact.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 28 (9): 1202–14, https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672022812006.Search in Google Scholar

Fox, Susan Anne, and Howard Giles. 1996. “Interability Communication.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 15 (3): 265–90, https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927x960153004.Search in Google Scholar

Gaertner, Samuel L., and John F. Dovidio. 2000. Reducing Intergroup Bias: The Common Ingroup Identity Model. East Sussex: Psychology Press.Search in Google Scholar

Gasiorek, Jessica, and Marko Dragojevic. 2017. “The Effects of Accumulated Underaccommodation on Perceptions of Underaccommodative Communication and Speakers.” Human Communication Research 43 (2): 276–94, https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12105.Search in Google Scholar

Giles, Howard. 2016. Communication Accommodation Theory: Negotiating Personal Relationships and Social Identities across Contexts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781316226537Search in Google Scholar

Harwood, Jake. 2000. “Communicative Predictors of Solidarity in the Grandparent-Grandchild Relationship.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 17 (6): 743–66, https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407500176003.Search in Google Scholar

Harwood, Jake, Miles Hewstone, Yair Amichai-Hamburger, and Nicole Tausch. 2013. “Intergroup Contact: An Integration of Social Psychological and Communication Perspectives.” Annals of the International Communication Association 36 (1): 55–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2013.11679126.Search in Google Scholar

Harwood, Jake, Miles Hewstone, Stefania Paolini, and Alberto Voci. 2005. “Grandparent-Grandchild Contact and Attitudes toward Older Adults: Moderator and Mediator Effects.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 31 (3): 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271577.Search in Google Scholar

Hayes, Andrew F. 2022. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Publications.Search in Google Scholar

Hewstone, Miles. 2000. “Contact and Categorization: Social Psychological Interventions to Change Intergroup Relations.” In Stereotypes and Prejudice: Key Readings, edited by Charles Stangor, 323–68. London: Psychology Press.Search in Google Scholar

Hewstone, Miles, and Rupert Brown. 1986. “Contact Is Not Enough: An Intergroup Perspective on the Contact Hypothesis.” In Contact and Conflict in Intergroup Encounters, edited by Miles Hewstone, and Rupert Brown, 1–44. Oxford: Blackwell.Search in Google Scholar

Hummert, Mary Lee. 2019. “Intergenerational communication.” In Language, communication, and intergroup relations: A celebration of the scholarship of Howard Giles, edited by Jake Harwood, Jessica Gasiorek, Herbert Pierson, Jon F. NussBaum, and Cindy Gallois, 130–61. London: Routledge.Search in Google Scholar

Imamura, Makiko, Yanbing Zhang, and Jake Harwood. 2011. “Japanese Sojourners’ Attitudes toward Americans.” Journal of Asian Pacific Communication 21 (1): 115–32, https://doi.org/10.1075/japc.21.1.09ima.Search in Google Scholar

Ives-Rublee, Mia, and Anona Neal. 2023. “The Recent COVID-Fueled Rise in Disability Calls for Better Worker Protections.” Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-recent-covid-fueled-rise-in-disability-calls-for-better-worker-protections/ (accessed October 26, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Johnston, Brian M., and Demis E. Glasford. 2017. “Intergroup Contact and Helping: How Quality Contact and Empathy Shape Outgroup Helping.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 21 (8): 1185–201, https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430217711770.Search in Google Scholar

Konrath, Sara H., Edward H. O’Brien, and Courtney Hsing. 2011. “Changes in Dispositional Empathy in American College Students over Time: A Meta-Analysis.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 15 (2): 180–98, https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310377395.Search in Google Scholar

Lash, Brittany N. 2022. “Managing Stigma through Laughter: Disability Stigma & Humor as a Stigma Management Communication Strategy.” Communication Studies 73 (4): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2022.2102668.Search in Google Scholar

Okoro, Catherine A., NaTasha D. Hollis, Alissa C. Cyrus, and Shannon Griffin-Blake. 2018. “Prevalence of Disabilities and Health Care Access by Disability Status and Type among Adults — United States, 2016.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67 (32): 882–7, https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6732a3.Search in Google Scholar

Pettigrew, Thomas F. 1998. “Intergroup Contact Theory.” Annual Review of Psychology 49 (1): 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65.Search in Google Scholar

Pettigrew, Thomas F., and Linda R. Tropp. 2008. “How Does Intergroup Contact Reduce Prejudice? Meta-Analytic Tests of Three Mediators.” European Journal of Social Psychology 38 (6): 922–34, https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.504.Search in Google Scholar

Pettigrew, Thomas F., Linda R. Tropp, Wagner Ulrich, and Oliver Christ. 2011. “Recent Advances in Intergroup Contact Theory.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 35 (3): 271–80, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.001.Search in Google Scholar

Ristić, Igor, Yanbing Zhang, and Ning Liu. 2019. “International Students’ Acculturation and Attitudes towards Americans as a Function of Communication and Relational Solidarity with Their Most Frequent American Contact.” Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 48 (6): 589–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2019.1695651.Search in Google Scholar

Ryan, Ellen Bouchard, Ann P. Anas, and Andrea J. S. Gruneir. 2006. “Evaluations of Overhelping and Underhelping Communication.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 25 (1): 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927x05284485.Search in Google Scholar

Ryan, Ellen B., Selina Bajorek, Amanda Beaman, and Ann P. Anas. 2005. “I Just Want You to Know That “Them” Is Me’: Intergroup Perspectives on Communication and Disability.” In Intergroup Communication: Multiple Perspectives, edited by Jake Harwood, and Howard Giles, 117–40. New York: Peter Lang.Search in Google Scholar

Schmitt, Michael T., Nyla R. Branscombe, Tom Postmes, and Amber Garcia. 2014. “The Consequences of Perceived Discrimination for Psychological Well-Being: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Psychological Bulletin 140 (4): 921–48, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035754.Search in Google Scholar

Sense. July, 2024. “Loneliness.” Sense.org.uk. https://www.sense.org.uk/support-us/campaigns/loneliness/.Search in Google Scholar

Shelton, J. Nicole, Tessa V. West, and Thomas E. Trail. 2010. “Concerns about Appearing Prejudiced: Implications for Anxiety during Daily Interracial Interactions.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 13 (3): 329–44, https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430209344869.Search in Google Scholar

Soliz, Jordan, and Howard Giles. 2014. “Relational and Identity Processes in Communication: A Contextual and Meta-Analytical Review of Communication Accommodation Theory.” Annals of the International Communication Association 38 (1): 107–44, https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2014.11679160.Search in Google Scholar

Spencer-Rodgers, Julie, and Timothy McGovern. 2002. “Attitudes toward the Culturally Different: The Role of Intercultural Communication Barriers, Affective Responses, Consensual Stereotypes, and Perceived Threat.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 26 (6): 609–31, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0147-1767(02)00038-x.Search in Google Scholar

Stephan, Walter G. 2014. “Intergroup Anxiety.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 18 (3): 239–55, https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314530518.Search in Google Scholar

Stephan, Walter G., and Cookie White Stephan. 1985. “Intergroup Anxiety.” Journal of Social Issues 41 (3): 157–75, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1985.tb01134.x.Search in Google Scholar

Trawalter, Sophie, Emma K. Adam, P. Lindsay Chase-Lansdale, and Jennifer A. Richeson. 2012. “Concerns about Appearing Prejudiced Get under the Skin: Stress Responses to Interracial Contact in the Moment and across Time.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48 (3): 682–93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.12.003.Search in Google Scholar

Tropp, Linda R., and Thomas F. Pettigrew. 2005. “Differential Relationships between Intergroup Contact and Affective and Cognitive Dimensions of Prejudice.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 31 (8): 1145–58, https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205274854.Search in Google Scholar

Tropp, Linda R., Özden Melis Ulug, and Mete Sefa Uysal. 2021. “How Intergroup Contact and Communication About Group Differences Predict Collective Action Intentions Among Advantaged Groups.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 80: 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.10.012.Search in Google Scholar

Trzeciak, Stephen, and Anthony Mazzarelli. 2022. Wonder Drug: 7 Scientifically Proven Ways That Serving Others Is the Best Medicine for Yourself. New York: St. Martin’s Essentials.Search in Google Scholar

United Nations. 2022. “Factsheet on Persons with Disabilities.” United Nations. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/resources/factsheet-on-persons-with-disabilities.html.Search in Google Scholar

Vezzali, Loris, Miles Hewstone, Dora Capozza, Elena Trifiletti, and Gian Antonio Di Bernardo. 2016. “Improving Intergroup Relations with Extended Contact among Young Children: Mediation by Intergroup Empathy and Moderation by Direct Intergroup Contact.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 27 (1): 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2292.Search in Google Scholar

Williams, Angie, and Howard Giles. 1996. “Intergenerational Conversations Young Adults’ Retrospective Accounts.” Human Communication Research 23 (2): 220–50, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1996.tb00393.x.Search in Google Scholar

World Health Organization. “Disability and Health.” WHO. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health (accessed March 7, 2023).Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Yanbing, Sile Li, and Jake Harwood. 2021. “Grandparent–Grandchild Communication and Attitudes toward Older Adults: Relational Solidarity and Shared Family Identity in China.” International Journal of Communication 15 (0): 19.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, Yanbing, Soojeong Paik, Chong Xing, and Jake Harwood. 2018. “Young Adults’ Contact Experiences and Attitudes toward Aging: Age Salience and Intergroup Anxiety in South Korea.” Asian Journal of Communication 28 (5): 468–89, https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2018.1453848.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter and FLTRP on behalf of BFSU

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Improving Interability Attitudes: Examining Positive and Negative Communication Processes

- The Practice of Early American Journalistic Professionalism in China – An Analysis of The China Weekly Review’s Reportorial Coverage on Extraterritoriality in China

- Language and Social Transformation in Nyumbantobhu: A Gendered Perspective

- Commentary

- The Translation and Scholarship of African Literature in China

- Review Article

- Representation of Indian Muslims in Bollywood Cinema: A Scholarly Review

- Book Review

- Bao, Hongwei, and Daniel H. Mutibwa: Entanglements and Ambivalences: Africa and China Encounters in Media and Culture

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- Improving Interability Attitudes: Examining Positive and Negative Communication Processes

- The Practice of Early American Journalistic Professionalism in China – An Analysis of The China Weekly Review’s Reportorial Coverage on Extraterritoriality in China

- Language and Social Transformation in Nyumbantobhu: A Gendered Perspective

- Commentary

- The Translation and Scholarship of African Literature in China

- Review Article

- Representation of Indian Muslims in Bollywood Cinema: A Scholarly Review

- Book Review

- Bao, Hongwei, and Daniel H. Mutibwa: Entanglements and Ambivalences: Africa and China Encounters in Media and Culture