Abstract

Background

Whether placental location confers specific neonatal risks is controversial. In particular, whether placenta previa is associated with intra-uterine growth restriction (IUGR)/small for gestational age (SGA) remains a matter of debate.

Methods

We searched Medline, EMBASE, Google Scholar, Scopus, ISI Web of Science and Cochrane database search, as well as PubMed (www.pubmed.gov) until the end of December 2018 to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the risk of IUGR/SGA in cases of placenta previa. We defined IUGR/SGA as birth weight below the 10th percentile, regardless of the terminology used in individual studies. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. We used odds ratios (OR) and a fixed effects (FE) model to calculate weighted estimates in a forest plot. Statistical homogeneity was checked with the I2 statistic using Review Manager 5.3.5 (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014).

Results

We obtained 357 records, of which 13 met the inclusion criteria. All study designs were retrospective in nature, and included 11 cohort and two case-control studies. A total of 1,593,226 singleton pregnancies were included, of which 10,575 had a placenta previa. The incidence of growth abnormalities was 8.7/100 births in cases of placenta previa vs. 5.8/100 births among controls. Relative to cases with alternative placental location, pregnancies with placenta previa were associated with a mild increase in the risk of IUGR/SGA, with a pooled OR [95% confidence interval (CI)] of 1.19 (1.10–1.27). Statistical heterogeneity was high with an I2 = 94%.

Conclusion

Neonates from pregnancies with placenta previa have a mild increase in the risk of IUGR/SGA.

Précis

Neonates from pregnancies with placenta previa have a mild increase in the risk of intra-uterine growth restriction (IUGR)/small for gestational age (SGA).

Introduction

Placenta previa refers to the presence of placental tissue that extends over the internal cervical os during pregnancy [1]. The incidence of this condition is reported to be 2% at 20 weeks of gestation, and through the process of placental migration known as trophotropism, decreases to around 4–6 per 1000 births between 34 and 39 weeks [2]. The primary risk factors for the development of placenta previa include a prior history of placenta previa, previous cesarean delivery, multiple gestations, use of fertility treatments and increasing maternal age, among others [3]. The risk of recurrence in subsequent pregnancies is reported at 4–8% [4].

Given its location over the cervical os, a proportion of the placental surface is exposed and lacks a proper uteroplacental interphase. Well-established sequelae of this condition include the potential for severe antenatal bleeding and preterm birth, as well as the need for cesarean delivery [3], [5]. The risk of bleeding is thought to occur when uterine contractions or gradual changes in the cervix and lower uterine segment apply shearing forces to the inelastic placental attachment site, resulting in partial detachment.

For this reason, it is theorized that a lower placental-decidua surface area may confer an increased risk of adverse neonatal outcomes, including neonatal anemia, respiratory distress, hyperbilirubinemia, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission and perinatal death [1]. Though given its pathophysiology of decreased placental surface and inadequate circulation may in theory explain an increased risk of adverse neonatal outcomes, whether the risk of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)/small for gestational age (SGA) is increased in placenta previa remains a matter of controversy [6], [7]. In this study, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the risk of IUGR/SGA in pregnancies complicated by placenta previa relative to those with normal placental insertion sites.

Materials and methods

Sources

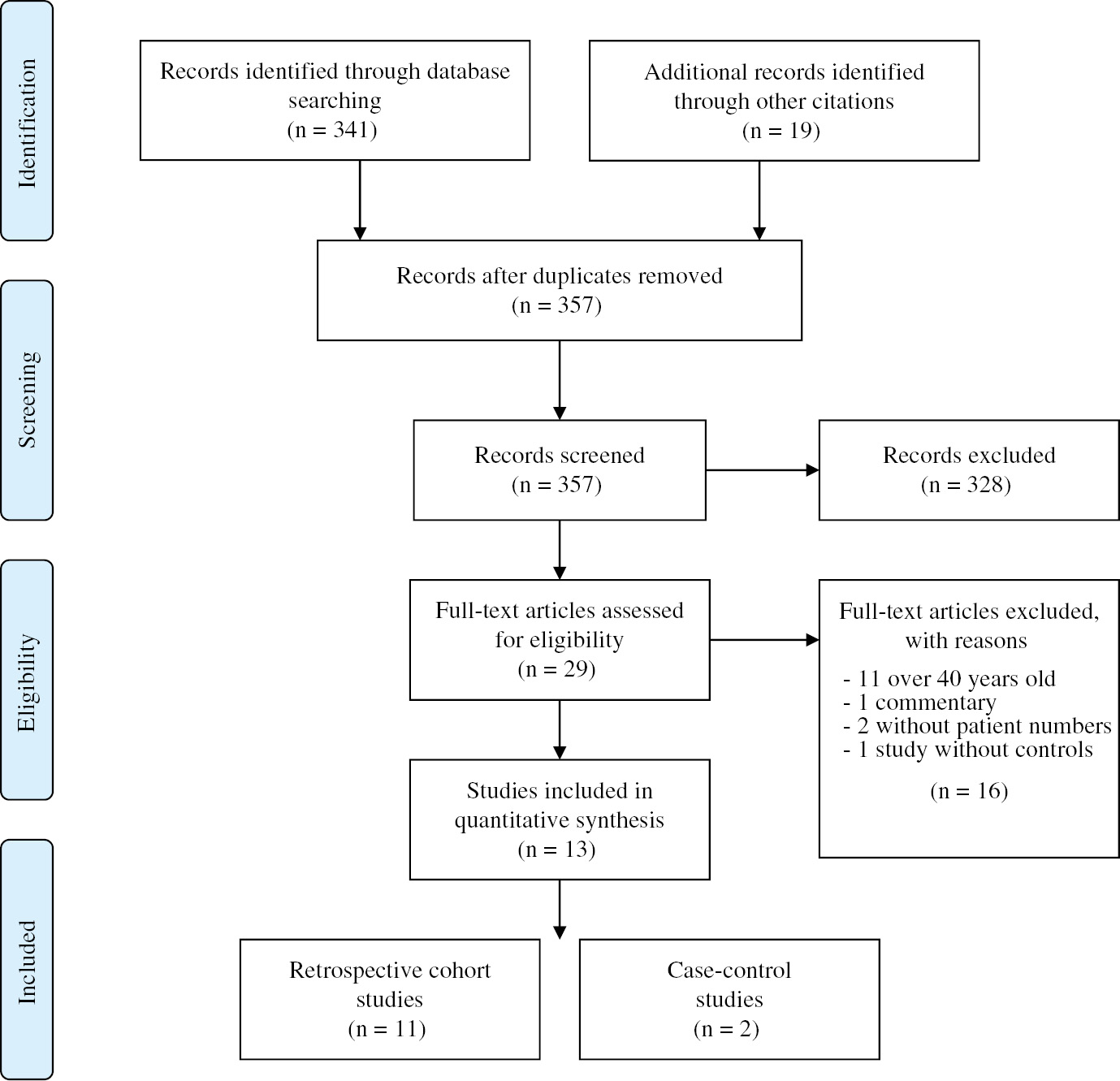

We performed a Medline, EMBASE, Google Scholar, Scopus, ISI Web of Science and Cochrane database search, as well as PubMed (www.pubmed.gov) search until the end of December 2018 from the last 30 years using the following Boolean search criteria: “(Placenta previa OR previa) AND (intrauterine growth restriction OR IUGR) OR (fetal growth restriction OR FGR) OR (small for gestational age OR SGA) OR (low birth weight OR LBW)”. Other than restricting the search to human studies and to articles in English, other limiting categorical terms used were the restriction to studies with singleton pregnancies and without any evidence of aneuploidy, congenital anomalies or placental trophoblastic invasion (accreta spectrum). The reference lists and bibliographies of included studies were then searched for other salient and pertinent manuscripts. Finally, manual searches of studies belonging to research teams having prior publications on placenta previa and growth restriction were undertaken, and other pertinent studies retrieved. This review was modeled on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement, and search flowchart depicting the search strategy is illustrated in Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart for the systematic review of studies.

Study selection

All authors independently examined the electronic search results for reports of possibly relevant studies and those reports were retrieved and analyzed in further detail. Published studies were eligible for inclusion if they compared the risk of IUGR/SGA between cases of placenta previa and cases of normal placental location. In undertaking our search, we defined IUGR/SGA as birth weight below the 10th percentile, regardless of the terminology used in individual studies. Indeed, we included studies, which used terminology such as “small for gestational age”, “fetal growth restriction” and “low birth weight”, provided that they referred to neonates born under the 10th percentile corrected for gestational age. In addition, we made no distinction between the mode of diagnosis of placenta previa, the placental orientation, the presence of antepartum bleeding, nor the year or country of origin of the study in question.

All studies were assessed following predetermined quality criteria including the presence of a power calculation, the unit of analysis used and risk of bias. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (results not shown). We attempted to contact one author to obtain supplementary information regarding their study, but did not receive a response. As such, we did not include the study in question into our analysis for lack of complete information.

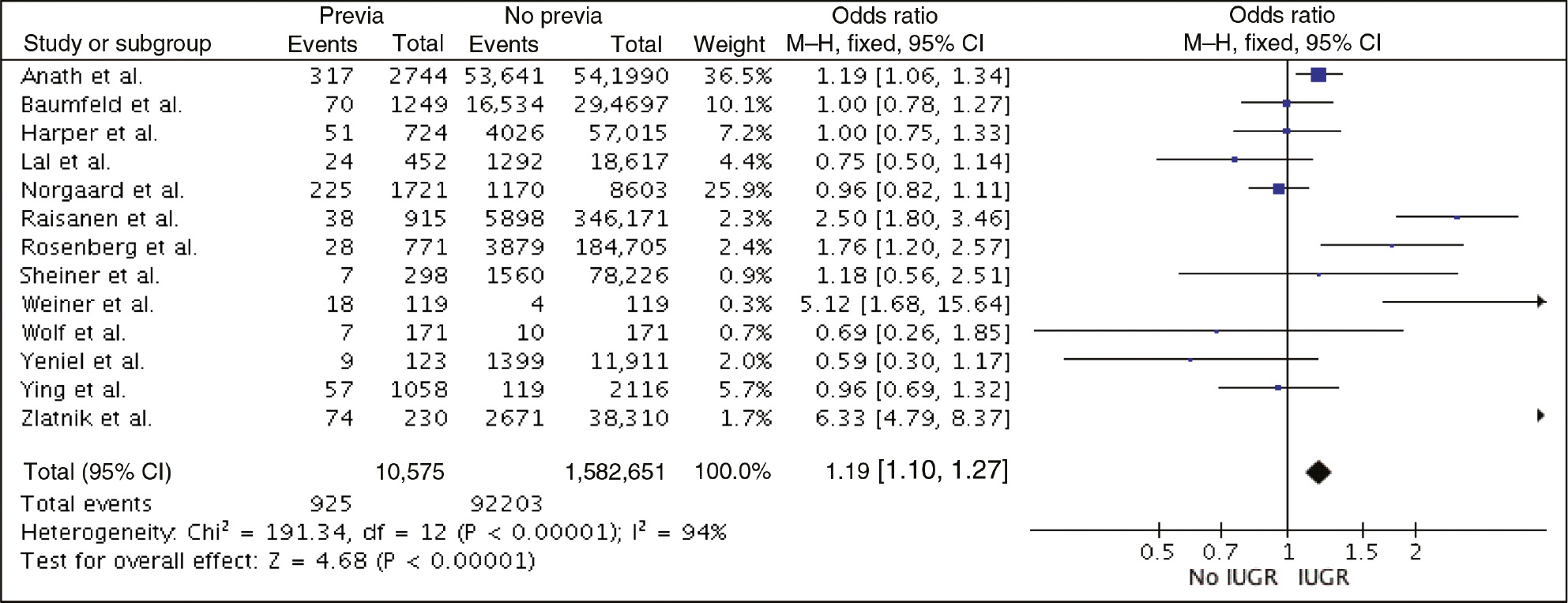

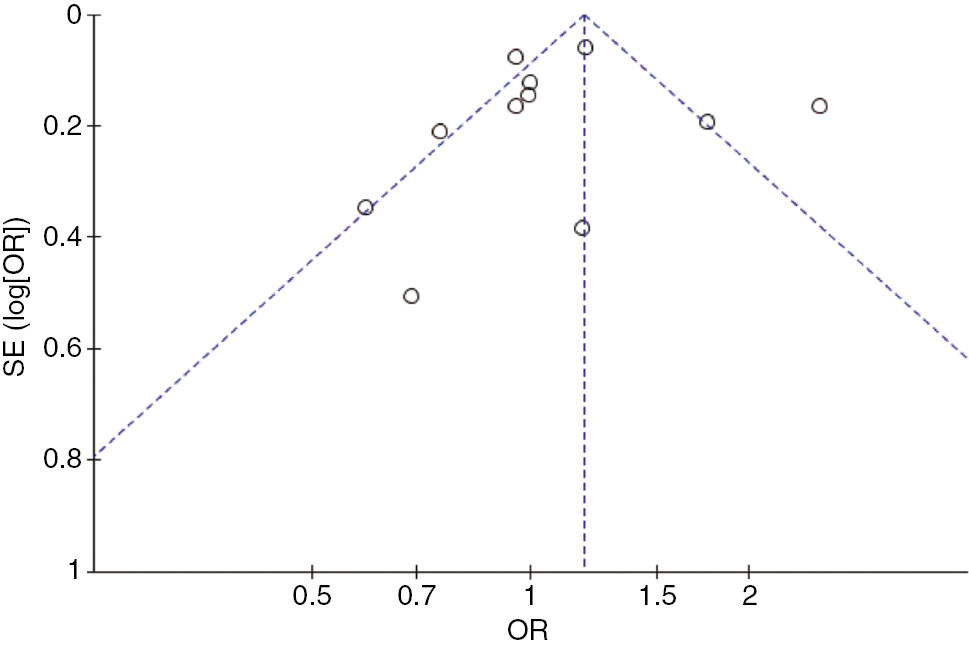

We used odds ratios (OR) and a fixed effects (FE) model with the Mantel-Haenszel method to calculate weighted estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) where appropriate. A forest plot and a funnel plot are provided for visualization of the results (Figures 2 and 3). Statistical heterogeneity between results of studies was examined by inspecting the scatter in the data points on the graphs and the overlap of CIs, and by checking the χ2 and I2 statistics. The Review Manager 5.3.5 software (Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) was used to combine data for the meta-analysis. This meta-analysis was exempt from Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval because of the nature of the research design (review article), as well as the lack of use of identified patient data.

Forest plot – risk of IUGR/SGA in placenta previa.

Funnel plot.

Results

We obtained 357 records, of which 13 met the inclusion criteria. All study designs were retrospective in nature, and included 11 cohort and two case-control studies. Study characteristics and individual inclusion criteria are provided in Table 1. A total of 1,593,226 singleton pregnancies were included, of which 10,575 had a placenta previa. The incidence of growth abnormalities was 8.7/100 births in cases of placenta previa vs. 5.8/100 births among controls. Relative to cases with alternative placental location, pregnancies with placenta previa were associated with a mild increase in the risk of IUGR/SGA, with a pooled OR (95% CI) of 1.19 (1.10–1.27) (forest plot – Figure 2). A funnel plot is provided in Figure 2 for visualization of the results. Statistical heterogeneity was high with an I2=94%.

Study characteristics.

| Year | Country | Design | n | Inclusion criteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ananth et al. [7] | 2001 | New Jersey, USA | Retrospective cohort study | 544,734 (previa=2744) | – | Singleton live delivery in NJ hospital between 1989 and 1993 |

| – | Restricted to cases of previa delivered by c/s | |||||

| – | SGA defined as <10th% | |||||

| Baumfeld et al. [8] | 2016 | Beer Sheva, Israel | Retrospective cohort study | 295,946 (previa=1249) | – | Deliveries 1998–2013 at Soroka University Medical Center with pregnancy complicated by placenta previa |

| – | Excluded: multiple gestation and fetal chromosomal/congenital malformation | |||||

| – | IUGR defined as growth <10th% | |||||

| Placenta previa dx sonographically | ||||||

| Harper et al. [6] | 2010 | Washington, USA | Retrospective cohort study | 57,739 (previa=724) | – | Singleton pregnancy delivered after 20 weeks of gestation, at single tertiary center 1990–2008 |

| – | Excluded: fetal demise/major fetal anomalies/multiple gestation, marginal previa | |||||

| – | Placenta previa diagnosis confirmed by TV US | |||||

| – | IUGR defined as birth weight <10th% using Alexander growth standard for GA at delivery | |||||

| Lal and Hibbard [9] | 2015 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | 19,069 (previa=452) | – | First singleton pregnancy in Consortium on Safe Labor database with placenta previa noted at admission or as reason for c/s |

| – | SGA defined as <10th% birth weight | |||||

| Nørgaard et al. [10] | 2012 | Denmark | Retrospective cohort study | 10,324 (previa=1721) | – | Singleton deliveries with placenta previa during 2001–2006 |

| – | Excluded: delivery <22 weeks | |||||

| – | Placenta previa confirmed in the third trimester by US/bleeding in the second trimester+placenta covering internal cervical os on US | |||||

| Räisänen et al. [11] | 2014 | Finland | Retrospective cohort study | 596,562 (previa=1540) | – | All singleton birth >22 weeks of GA (or >500 g) on Finnish Medical Birth Register and Welfare 2000–2010 |

| – | Excluded: major congenital anomalies/multiple gestation, birth missing information on GA, birth weight or parity | |||||

| – | Placenta previa diagnosed on US, confirmed in the third trimester | |||||

| – | SGA defined as BW <2 standard deviations below the mean (Finnish population-based birth curves) | |||||

| Rosenberg et al. [3] | 2010 | Beer Sheva, Israel | Retrospective cohort study | 185,476 (previa=771) | – | All singleton pregnancy with placenta previa, delivered at Soreka University Medical Center 1988–2009 |

| – | Excluded: Multiple fetuses/pregnancies w/o adequate prenatal surveillance | |||||

| Previa diagnosed by US in the second or third trimester | ||||||

| Sheiner et al. [12] | 2001 | Beer Sheva, Israel | Retrospective cohort study | 78,524 (previa=298) | – | All computerized singleton deliveries at Soroka University Medical Center 1990–1998 |

| Placenta previa defined as placental attachment totally/mostly in lower uterine segment, covering internal os in the third trimester, diagnosed by US and during labor | ||||||

| Weiner et al. [13] | 2016 | Holon, Israel | Case-control study | 238 (previa=119) | – | Cesarean deliveries for placenta previa between 24 and 42 weeks of GA between 2009 and 2015 |

| – | Excluded: multiple gestation, deliveries <24 weeks, known fetal/neonatal malformation, cases with concurrent placenta accreta and cases missing data | |||||

| – | Control=elective c/s during same period, for malpresentation or previous c/s and placenta sent to pathology | |||||

| Diagnosis of placenta previa confirmed in all women in the third trimester TV US+placenta sent to pathology | ||||||

| Wolf et al. [14] | 1991 | Connecticut, USA | Case-control study | 342 (previa=171) | – | Deliveries between 1980 and 1990 in affiliated hospitals of MFM division of University of Connecticut |

| – | Known gestational age (two of gestational age criteria) | |||||

| – | Excluded: cases with chronic HTN, pregnancy induce HTN, multiple gestation, insulin dependent diabetes, fetal/neonatal anomalies | |||||

| – | Placenta previa defined as implantation in the lower uterine segment in advance of the presenting part | |||||

| – | Control=patient matched for race, parity, GA at delivery and fetal gender | |||||

| – | SGA defined as BW <10th% of GA | |||||

| Yeniel et al. [15] | 2012 | Turkey | Retrospective cohort study | 12,034 (previa=123) | – | Singleton gestation delivered between 20 and 42 weeks |

| – | Excluded: fetal anomaly cases, questionable placenta previa diagnosis | |||||

| – | Placenta previa defined as implantation over cervical os. Determined by the second/third trimester US and at c/s | |||||

| – | FGR defined as BW <10th% using Alexander growth monogram for GA at delivery | |||||

| Ying et al. [16] | 2016 | Shanghai, China | Retrospective cohort study | 3174 (previa=1058) | – | Singleton pregnancy with abnormal position of placenta delivered by c/section at a tertiary hospital, between 2010 and 2014 |

| – | Excluded: low lying placenta, history of gestational HTN/pre-eclampsia, abnormal gestation or birth history, recurrent spontaneous abortion, use of specific medications during pregnancy (ASA, LMWH, glucocorticoids), lethal fetal malformation, complication during pregnancy (chronic HTN, CKD, DMII, hyper/hypothyroidism, auto-immune disease) | |||||

| Placenta previa diagnosis confirmed by TV US between 32 and 36 weeks | ||||||

| Zlatnik et al. [17] | 2007 | California, USA | Retrospective cohort study | 38,540 (previa=230) | – | All singleton delivery between 1980 and 2006 at Moffit-Long Hospital |

| – | Excluded: delivery <24 weeks GA, fetuses with known lethal congenital anomalies, multifetal gestation and maternal transports | |||||

| – | Placenta previa diagnosed by US in the second trimester and confirmed subsequently | |||||

TV US, transvaginal ultrasound; GA, gestational age; c/s, cesarean section; BW, birth weight; HTN, hypertension; FGR, fetal growth restriction; ASA, acetyl salicylic acid; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DMII, type II diabetes mellitus; MFM, Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Discussion

The most common presentation of placenta previa is as a finding on routine ultrasound examination at about 16–20 weeks of gestation for assessment of gestational age, fetal anatomic survey or prenatal diagnosis [1], [3]. The diagnosis of placenta previa requires the identification of echogenic homogeneous placental tissue over the internal cervical os [18]. One to six percent of pregnant women are found to have sonographic evidence of a placenta previa on these examinations [19]. When placenta previa persists near term, several important adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes may ensue. However, whether placenta previa increases the risk of IUGR/SGA is controversial. In this meta-analysis of over 1,593,226 singleton pregnancies and 10,575 confirmed cases of placenta previa, we show that placenta previa increases the relative risk of IUGR/SGA by an average of 19% (95% CI 10–27%).

Whether one should consider placenta previa in the same category as other placental insertion abnormalities is unknown. Nevertheless, several clinical associations with other placental conditions exist, which may point to an underlying genetic susceptibility. One hypothesis is that the presence of areas of suboptimally vascularized decidua in the upper uterine cavity due to previous surgery or multiple pregnancies promotes implantation of trophoblast in healthy decidua near the lower uterine cavity [20].

It is well documented that when placenta previa is diagnosed, the possibility of placenta previa-accreta should be considered [21]. In a prospective study of women with placenta previa undergoing cesarean delivery, the frequency of placenta accreta increased proportionally with an increasing number of cesarean deliveries. Similarly, placenta previa is a known risk factor for vasa previa and velamentous umbilical cord insertion [19], [21].

Despite the controversial evidence, several theories have attempted to explain the potential etiologies of an association between placenta previa and growth abnormalities in the fetus. First, as the muscle mass and contractile work of the corpus uteri and fundus are greater than in the lower uterine segment, the blood supply to the latter is likely lower, presumably resulting in lower perfusion for a low-lying placenta previa. Similarly, repeated bleeding episodes from placenta previa may impact fetal oxygenation and growth. In keeping with this theory, numerous reports have documented an increased risk of fetal anemia in cases of placenta previa, which may be related both to intra-placental bleeding of fetal origin during pregnancy and to the incision through the fetal vessels in the placenta during cesarean delivery [1]. Finally, whether epidemiologic confounders or modifying variables in certain studies account for an increased risk of IUGR/SGA has been observed. The prime example is the study by Räisänen et al. [11], which finds an increased risk of IUGR with placenta previa, only among multiparous, but not nulliparous women. That said, differences in the risk of fetal growth restriction have been observed depending on whether univariate or multivariate analyses are undertaken [7], [20], [22], [23].

Clinical implications of the findings

The management of pregnancies at risk of IUGR includes the provision of prenatal screening, the adequate assessment of fetal anatomy, the continuous monitoring of fetal biometry throughout gestation and, in select cases, the provision of anticoagulation or anti-platelet therapy [24]. As with most normal pregnancies, before a placenta previa is diagnosed, the vast majority of patients will have undergone regular prenatal screening and evaluation of fetal anatomy. Given the need to re-assess placental location and its distance to the internal os in the third trimester to plan for delivery, fetal growth is already likely to be estimated at that time again. Moreover, given the substantial risk of antepartum hemorrhage, whether the provision of aspirin and anticoagulation in women with placenta previa increases such risk has not been studied. Therefore, at the present time, the findings of this study are unlikely to alter the current clinical management of these pregnancies.

That said, once IUGR is established, fetal Doppler studies are recommended to screen for signs of placental insufficiency and fetal distress [24]. Depending on the etiology and severity of IUGR, delivery is likely to be induced around 38–39 weeks of gestation. However, given the risk of catastrophic hemorrhage, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommend that pregnancies with uncomplicated placenta previa be delivered between 36+0 and 37+6 weeks of gestation [25]. Therefore, at the present time, there is no evidence that specifically monitoring fetal growth or Doppler studies with serial ultrasound examinations is useful in cases of placenta previa. Given the findings of this study, which only suggest a mild increase in the risk of IUGR/SGA, we do not propose that further screening with serial scans be undertaken at this time. Nevertheless, what the findings of this study may in fact prompt is a more comprehensive counseling to patients, as well as to the NICU team, who may care for the neonates with this condition, often born in the late-preterm or early-term period.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study are multiple and include the vast number of patients analyzed, the homogeneity of the inclusion criteria across studies, as well as the use of proper statistical techniques. Similarly, to the best of our knowledge, ours is the first and only meta-analysis in the literature addressing the association between placenta previa and growth restriction, an increasingly important and relevant question in clinical medicine today. On the other hand, the limitations of our study are several and worth mentioning. First, while all of the studies included in the meta-analysis addressed the outcome of IUGR, the definitions are not strictly identical and as such, they may introduce bias into our estimates. Indeed, the literature is notoriously heterogeneous with regard to terminology about growth restriction, with some reports considering growth under the 10th percentile as diagnostic while others do so in cases under the fifth or third centile. That said, all weight estimates were sonographically determined and the same criteria were used for all patients in each individual study. Likewise, though individual studies may use a different terminology, be it IUGR or SGA, all refer to fetuses whose growth falls below the 10th percentile for gestational age. Second, though the pooled number of patients is high, statistical heterogeneity between studies was large as well, with an I2 of 94%. Third, given the retrospective nature of the study designs included in the meta-analysis, adjusting for different confounders in individual studies may have introduced information bias. To mitigate these, we conducted sensitivity analyses looking at univariate and multivariate estimates in individual studies, and our findings and conclusion remained unchanged. Finally, despite the robustness of our findings, we cannot prove a causal relationship between placenta previa and IUGR/SGA.

Conclusion

Neonates from pregnancies with placenta previa have a mild but significant increase in the risk of IUGR/SGA. A greater understanding of placenta previa and its consequences can allow providers to better inform, counsel and manage patients with this condition. Whether the degree of IUGR/SGA is significant and whether it requires increased surveillance and/or prompt delivery are outside the scope of the current study. Future studies should attempt to address this question.

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

Research funding: None declared.

Employment or leadership: None declared.

Honorarium: None declared.

Competing interests: The funding organization(s) played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

References

1. Schneiderman M, Balayla J. A comparative study of neonatal outcomes in placenta previa versus cesarean for other indication at term. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;26:1121–7.10.3109/14767058.2013.770465Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Faiz A, Ananth C. Etiology and risk factors for placenta previa: an overview and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Mater Fetal Neonatal Med 2003;13:175–90.10.1080/jmf.13.3.175.190Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Rosenberg T, Pariente G, Sergienko R, Wiznitzer A, Sheiner E. Critical analysis of risk factors and outcome of placenta previa. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011;284:47–51.10.1007/s00404-010-1598-7Search in Google Scholar PubMed

4. Lavery JP. Placenta previa. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1990;33:414–21.10.1097/00003081-199009000-00005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Fan D, Wu S, Liu L, Xia Q, Wang W, Guo X, et al. Prevalence of antepartum hemorrhage in women with placenta previa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2017;7:40320.10.1038/srep40320Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Harper LM, Odibo AO, Macones GA, Crane JP, Cahill AG. Effect of placenta previa on fetal growth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203:330.e1–5.10.1016/j.ajog.2010.05.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Ananth CV, Demissie K, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. Relationship among placenta previa, fetal growth restriction, and preterm delivery: a population-based study. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:299–306.10.1097/00006250-200108000-00021Search in Google Scholar

8. Baumfeld Y, Herskovitz R, Niv ZB, Mastrolia SA, Weintraub AY. Placenta associated pregnancy complications in pregnancies complicated with placenta previa. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2017;56:331–5.10.1016/j.tjog.2017.04.012Search in Google Scholar PubMed

9. Lal AK, Hibbard JU. Placenta previa: an outcome-based cohort study in a contemporary obstetric population. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2015;292:299–305.10.1007/s00404-015-3628-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed

10. Nørgaard LN, Pinborg A, Lidegaard Ø, Bergholt T. A Danish national cohort study on neonatal outcome in singleton pregnancies with placenta previa. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2012;91:546–51.10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01375.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

11. Räisänen S, Kancherla V, Kramer MR, Gissler M, Heinonen S. Placenta previa and the risk of delivering a small-for-gestational-age newborn. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:285.10.1097/AOG.0000000000000368Search in Google Scholar

12. Sheiner E, Shoham-Vardi I, Hallak M, Hershkowitz R, Katz M, Mazor M. Placenta previa: obstetric risk factors and pregnancy outcome. J Matern Fetal Med 2001;10:414–9.10.1080/jmf.10.6.414.419Search in Google Scholar

13. Weiner E, Miremberg H, Grinstein E, Mizrachi Y, Schreiber L, Bar J, et al. The effect of placenta previa on fetal growth and pregnancy outcome, in correlation with placental pathology. J Perinatol 2016;36:1073.10.1038/jp.2016.140Search in Google Scholar

14. Wolf EJ, Mallozzi A, Rodis JF, Egan J, Vintzileos AM, Campbell WA. Placenta previa is not an independent risk factor for a small for gestational age infant. Obstet Gynecol 1991;77:707–9.Search in Google Scholar

15. Yeniel AO, Ergenoglu AM, Itil IM, Askar N, Meseri R. Effect of placenta previa on fetal growth restriction and stillbirth. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012;286:295–8.10.1007/s00404-012-2296-4Search in Google Scholar

16. Ying H, Lu Y, Dong Y-N, Wang D-F. Effect of placenta previa on preeclampsia. PLoS One 2016;11:e0146126.10.1371/journal.pone.0146126Search in Google Scholar

17. Zlatnik MG, Cheng YW, Norton ME, Thiet M-P, Caughey AB. Placenta previa and the risk of preterm delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2007;20:719–23.10.1080/14767050701530163Search in Google Scholar

18. Quant HS, Friedman AM, Wang E, Parry S, Schwartz N. Transabdominal ultrasonography as a screening test for second-trimester placenta previa. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123:628–33.10.1097/AOG.0000000000000129Search in Google Scholar

19. Oyelese Y, Smulian JC. Placenta previa, placenta accreta, and vasa previa. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:927–41.10.1097/01.AOG.0000207559.15715.98Search in Google Scholar

20. Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. The association of placenta previa with history of cesarean delivery and abortion: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;177:1071–8.10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70017-6Search in Google Scholar

21. Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, Leveno KJ, Spong CY, Thom EA, et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol 2006;107:1226–32.10.1097/01.AOG.0000219750.79480.84Search in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Balayla J, Bondarenko HD. Placenta accreta and the risk of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. J Perinat Med 2013;41:141–9.10.1515/jpm-2012-0219Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Balayla J, Lan Wo B, Bedard MJ. The optimal timing for delivery in placenta previa. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2016;29:2280–1.10.3109/14767058.2015.1083005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Grantz KL, Kim S, Grobman WA, Newman R, Owen J, Skupski D, et al. Fetal growth velocity: the NICHD fetal growth studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219:285.e1–36.10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Spong CY, Mercer BM, D’Alton M, Kilpatrick S, Blackwell S, Saade G. Timing of indicated late-preterm and early-term birth. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:323.10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182255999Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

©2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Placenta previa and the risk of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR): a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Research Articles – Obstetrics

- Total gestational weight gain and the risk of preeclampsia by pre-pregnancy body mass index categories: a population-based cohort study from 2013 to 2017

- Comparison of automated vs. manual measurement to estimate fetal weight in isolated polyhydramnios

- Strain and dyssynchrony in fetuses with congenital heart disease compared to normal controls using speckle tracking echocardiography (STE)

- Maternal abdominal subcutaneous fat thickness as a simple predictor for gestational diabetes mellitus

- Pregnancy outcome following bacteriuria in pregnancy and the significance of nitrites in urinalysis – a retrospective cohort study

- Nearly half of all severe fetal anomalies can be detected by first-trimester screening in experts’ hands

- Effect of maternal obesity on pregnancy outcomes in women delivering singleton babies: a historical cohort study

- Comparison of quantitative fluorescent polymerase chain reaction and karyotype analysis for prenatal screening of chromosomal aneuploidies in 270 amniotic fluid samples

- Effect of Sjögren’s syndrome on maternal and neonatal outcomes of pregnancy

- Intrapartum prediction of birth weight with a simplified algorithmic approach derived from maternal characteristics

- Efficacy of copy-number variation sequencing technology in prenatal diagnosis

- Socio-cultural and clinician determinants in the maternal decision-making process in the choice for trial of labor vs. elective repeated cesarean section: a questionnaire comparison between Italian settings

- Research Articles – Newborn

- Tidal volume monitoring during initial resuscitation of extremely prematurely born infants

- The level of extracellular superoxide dismutase in the first week of life in very and extremely low birth weight infants and the risk of developing bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- Effect of gender on growth-restricted fetuses born preterm

- Letters to the Editor

- Dermal bilirubin kinetics during phototherapy in term neonates

- Transcutaneous bilirubin to guide phototherapy: authors’ reply

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- Placenta previa and the risk of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR): a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Research Articles – Obstetrics

- Total gestational weight gain and the risk of preeclampsia by pre-pregnancy body mass index categories: a population-based cohort study from 2013 to 2017

- Comparison of automated vs. manual measurement to estimate fetal weight in isolated polyhydramnios

- Strain and dyssynchrony in fetuses with congenital heart disease compared to normal controls using speckle tracking echocardiography (STE)

- Maternal abdominal subcutaneous fat thickness as a simple predictor for gestational diabetes mellitus

- Pregnancy outcome following bacteriuria in pregnancy and the significance of nitrites in urinalysis – a retrospective cohort study

- Nearly half of all severe fetal anomalies can be detected by first-trimester screening in experts’ hands

- Effect of maternal obesity on pregnancy outcomes in women delivering singleton babies: a historical cohort study

- Comparison of quantitative fluorescent polymerase chain reaction and karyotype analysis for prenatal screening of chromosomal aneuploidies in 270 amniotic fluid samples

- Effect of Sjögren’s syndrome on maternal and neonatal outcomes of pregnancy

- Intrapartum prediction of birth weight with a simplified algorithmic approach derived from maternal characteristics

- Efficacy of copy-number variation sequencing technology in prenatal diagnosis

- Socio-cultural and clinician determinants in the maternal decision-making process in the choice for trial of labor vs. elective repeated cesarean section: a questionnaire comparison between Italian settings

- Research Articles – Newborn

- Tidal volume monitoring during initial resuscitation of extremely prematurely born infants

- The level of extracellular superoxide dismutase in the first week of life in very and extremely low birth weight infants and the risk of developing bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- Effect of gender on growth-restricted fetuses born preterm

- Letters to the Editor

- Dermal bilirubin kinetics during phototherapy in term neonates

- Transcutaneous bilirubin to guide phototherapy: authors’ reply