Abstract

At the beginning of the sixteenth century, the controversy around the Hebraist Johannes Reuchlin rather quickly developed from a mere scholarly dispute into a mass media event. The German humanists played a large part in this, countering his supposed opponent, the Jewish convert Johannes Pfefferkorn, with a multitude of elaborate invectives, and acting as a vituperative community. Ulrich von Hutten participated particularly eagerly in the anti-Pfefferkorn discourse and was heavily involved in its satirical climax, the Epistolae obscurorum virorum. The concept of “invectivity” can provide a new heuristic focus for questions related to the function, effect and group dynamics of humanist invectives, especially in the example of Hutten, and help to better understand the complexity of this European media event.

1 Reuchlin versus Pfefferkorn: The So-Called “Jewish Book Controversy”

Words at war. Words can hurt and can therefore be understood as weapons.[1] However, invective communication cannot only provide an enormous arsenal of rhetorical weapons,[2] but in addition to this hurtful and exclusionary function, invectives also have a group-forming function.[3] This becomes particularly obvious in early sixteenth-century German humanism.[4] In this context, the media conditions must also be taken into account, since the invention of printing with movable types had also created conditions for a fundamental upheaval in the media landscape.[5] The disputes, which were in part characteristic of the humanist milieu, now took place in a more dynamic and multi-layered public sphere and not infrequently grew into spectacular verbal exchanges.[6] The preferred rhetorical form – following the communicative practices of their Italian prototypes, such as Francesco Petrarca, Lorenzo Valla, or Poggio Bracciolini – was the invective.[7] Especially due to its agonal, i.e. competitive, character, the invective out of the pen of the humanists advanced to become a diversely applicable weapon in their publishing activities.[8] For through the display of erudition (eruditio) and the immaculate use of the languages and genres of antiquity (esp. latinitas),[9] they succeeded in establishing a double position, on the one hand to distinguish themselves as authors (self-fashioning),[10] but at the same time to strengthen the cohesion of the group to the outside world (community-fashioning).[11] The distinctive potential of the humanist invective can be observed in particular in the context of the Reuchlin controversy (ca. 1510–1521), which was fought out all over Europe,[12] and in which the Franconian imperial knight Ulrich von Hutten participated with various invectives.[13] Due to the complexity of the event’s context, we will briefly outline the conflict surrounding the so-called “Judenbücherstreit”[14] and additionally offer some thoughts on the function and effect of invectives. Our starting point is the thesis that invective potential usually only becomes recognisable in follow-up communication or in contextualisation by third parties.[15]

As the complex of events in the Reuchlin controversy has already been well researched, we can limit ourselves to the most important stages of publication with regard to our question.[16] At the beginning of the sixteenth century, the jurist Reuchlin had already gained a certain European reputation in the field of Hebraic and Greek studies through his publications.[17] In our context, his Tütsch missiue, warumb die Juden so lang im ellend sind (1505)[18] and his Rudimenta (De Rvdimentis Hebraicis, 1510),[19] a short grammar of Hebrew, should be mentioned. The first text in particular is important for understanding the extensive dispute, since Reuchlin’s opponents would later refer to it again and again.[20] His later adversary Johannes Pfefferkorn,[21] a Jew who had converted to Christianity, had launched an anti-Jewish media campaign at the time.[22] With the help of the Cologne Dominicans, four anti-Jewish prints were produced in quick succession from 1507 to 1509: the Judenspiegel (1507),[23] the Judenbeichte (1508),[24] the so-called Osterbüchlein (1509)[25] and the Judenfeind (1509).[26] These texts are all directed against the Jews and their position in society, sharply attacking them, denouncing them as obdurate enemies of Christianity and ridiculing their customs and rituals. The “Jewish usury,” said Pfefferkorn, had to be stopped; the Jews themselves had to be forced into missionary work and their writings burned.[27]

The theological question of whether Jewish books should be burned or not eventually ignited the entire debate. Pfefferkorn’s anti-Jewish zeal initially paid off in that he was able to obtain a mandate from Emperor Maximilian I on 19 August 1509, which, together with a second mandate, entitled him to confiscate and destroy the Jewish books in Frankfurt/Main[28] and Worms.[29] The Emperor soon revised his decision, however, because a third mandate was subsequently issued (26 July 1510),[30] which ordered four universities and three scholars to examine the matter and draw up legal opinions accordingly.[31] Among them, only Johannes Reuchlin spoke out in favour of the preservation and against the confiscation of Jewish literature in his expert opinion of 6 October 1510,[32] reinterpreting in a humanist way the attack on Jewish books as an attack on knowledge.[33] The escalation that followed was unparalleled in the intellectual world. A scholarly debate turned into a palpable dispute, which soon gripped entire movements with its invective dynamics. Pfefferkorn initially reacted to Reuchlin’s supposed “advice” with the Handspiegel (1511),[34] which he regarded as a betrayal above all because Pfefferkorn at the beginning of the anti-Jewish campaign had still believed that he could win Reuchlin over to his own cause. However, after the latter had ridiculed Pfefferkorn’s Handspiegel with the Augenspiegel (1511)[35] in the same year, the two opponents took turns with numerous invective texts,[36] although it is precisely here that the invective mode is characterised by a dialogical nature.[37] As early as 1512, in a letter to his Cologne friend Konrad Kollin, Reuchlin expressed himself in an ironic undertone with regard to the initial dynamics of the dispute: “Easy is it to begin a dispute, but difficult to end it.”[38] This development was also evident a little later in the Reformation controversies, when the disputations still practised at the beginning gave way to less regulated religious discussions.[39] Reuchlin thus did not even think of leaving the matter in a small setting cut off from broad public discourse.

The escalation of this conflict cannot be attributed to a rigid ideological scholastic-humanist opposition. From the point of view of “invectivity,” it becomes apparent that affective aspects such as personal rivalry, injured sense of honour and competition for influence and power were dynamic components of “invectivity” that played a far greater role.[40] The real thrust of Reuchlin’s invective, and later that of his supporters, was actually aimed at the religious clergy and theologians of Cologne University behind Pfefferkorn.[41] In addition to the proceedings concerning Reuchlin’s expert opinion in Erfurt, Cologne and Mainz, there were further trials in Speyer (“Berufungsverfahren”), Paris and Rome.[42] Finally, the media affordances of the new forms of communication must also be taken into account, which for the first time addressed a supra-regional, ultimately pan-European public and were further fuelled by the invective interaction of the adversaries. Thus, by the time of the Roman condemnation of the Augenspiegel in 1520, the Causa Reuchlini had already taken on the features of a “media event.”[43] Numerous humanists took part in the anti-Pfefferkorn debate,[44] admittedly also in order to benefit from the matter for their own reputation. The latter thesis in particular is conspicuously illustrated perfectly by Ulrich von Hutten’s invectives.

With the term “invectivity,” which has already been used here several times, we refer not only to the rhetorical genre of invective (oratio invectiva), but more generally to hurtful communication.[45] Its individual aspects can only be adequately elaborated by taking into account the historical constellations, cultural contexts and media conditions. In our thematic context, this raises the question to which end Hutten’s invectives in the Reuchlin controversy may have served. With regard to function, the concept of “invectivity” suggests that the effects of the invective should be seen as contingent, since invectives are fundamentally beyond planning and only realise themselves in their respective contexts. Therefore, clear “functions” are by no means inherent to Ulrich von Hutten’s invectives.[46] They can, however, be fundamentally located in the correlation of self-fashioning and community-fashioning outlined at the beginning. The invectives were not primarily directed at the alleged opponents, but at a public audience. At the same time, invectives provoke follow-up communication that contributes to an escalation of the conflict, an invective public.[47] One of the main focusses of this article will therefore be the reconstruction of the media interactions between Hutten and his opponents. Furthermore, however, it must be taken into account that literature produces an “active cognitive force that is instrumental in generating attitudes, discourses, ideologies, values, patterns of thought and perception.”[48]

Accordingly, the question of functions is not to be understood in the sense of a functionalism that might attribute invective events entirely to external contexts presupposed in the analysis. Instead, we understand it in the sense of a functional analysis of the immanent modes of action, historical-social contexts of reference and structuring effects of “invectivity.” An obvious starting point is to describe invective communications in terms of their socially excluding or including effects. Thus – for example in the context of the hate speech debate – the focus is on their function to demean, shame, marginalise and exclude individuals, and above all to do so with entire groups, social milieus, ethnic groups or nations.[49]

Thus, functions are always interlinked with potential and intentions of effect, and at the same time framed by a wide variety of normative contexts.[50] Because various dimensions of “invectivity” can be observed,[51] such normative contexts are supposed to be inscribed in the invective arena[52] and its rules of the game.[53] The question remains to what extent Hutten, a Reuchlin supporter, was able to profit from this escalating dynamic with his literary zeal. Furthermore, we need to find out where the “turning points” of the dispute were and what concrete functions invectives had in the context.

2 Laughter and Violence as Invective Tipping Moments: Hutten’s Exclamatio on Pfefferkorn (1514)

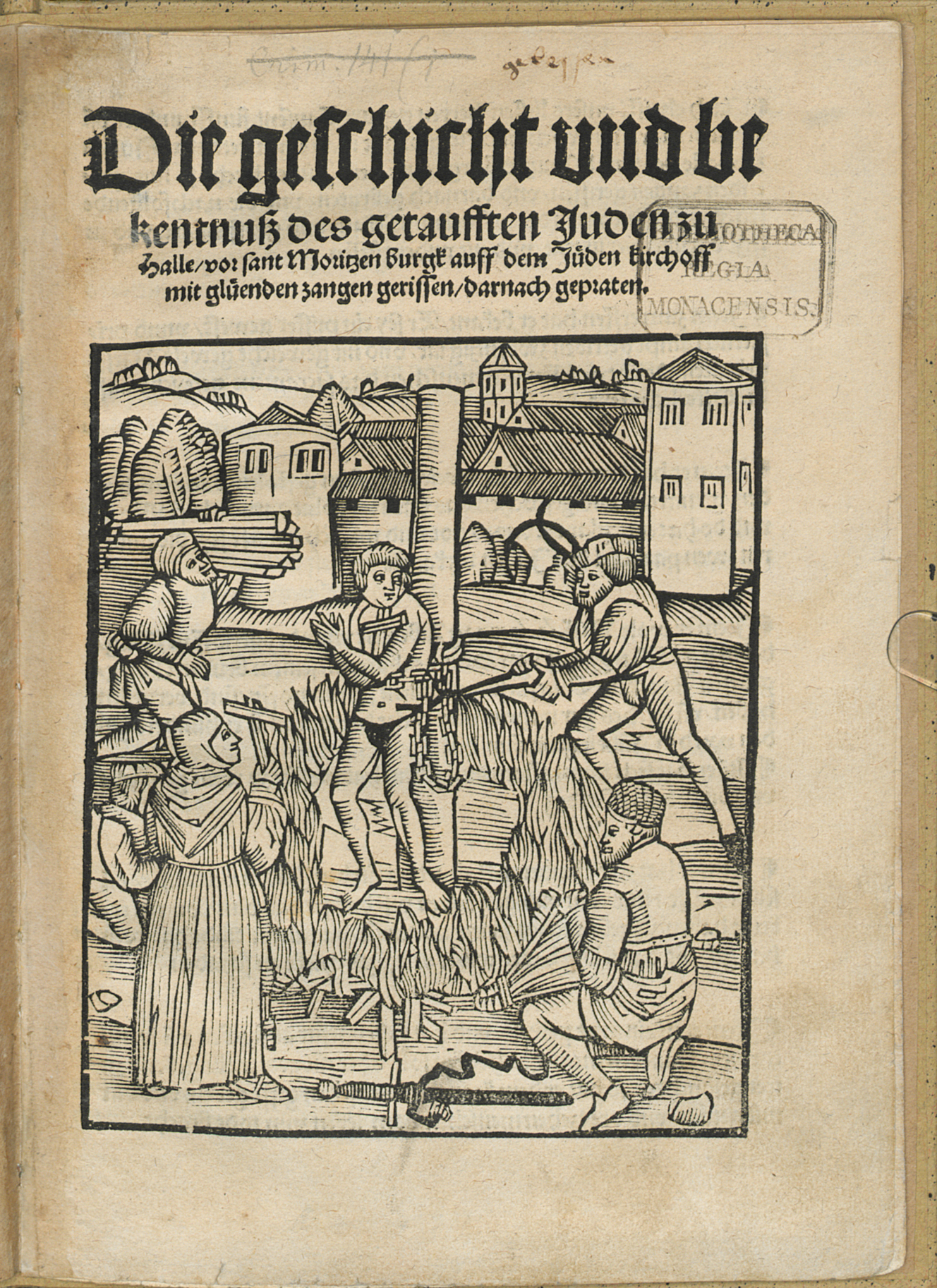

Hutten and Reuchlin met in person for the first time in 1514. Seemingly inspired by this meeting, Hutten wrote an anti-Jewish pamphlet of 119 hexameters as the first part of a panegyric on Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz, entitled In sceleratissimam Ioannis Pepericorni vitam exclamatio or Exclamatio heroica in Johannis Pepercorni vitam. This poem was probably first printed in the late autumn of 1514.[54] It referred to an event that apparently had nothing to do with the Causa Reuchlini. It is fairly certain that on 6 September 1514, a baptised Jew by the name of Johannes Pfefferkorn was killed and burned in front of the Moritzburg in Halle (Saale), after he had been accused of common Jewish stereotypes such as ritual murder or desecration of the host. Hutten himself, however, was not present at the trial at all, but compiled material for his account from the minutes that were leaked to him. It was probably through his encounter with Reuchlin that he got the idea to write the vicious poem, which not only offensively justified the evil treatment of the delinquent in Halle because he allegedly wanted to poison Archbishop Albrecht, but also denounced him in such a way that researchers have lately regarded it as “one of the darkest testimonies of early modern hostility towards Jews.” Hutten’s interest lay elsewhere anyway: in the context of the Reuchlin controversy, the text is characterised by a significant ambiguity. Of course, Hutten was aware that he could play on the already acquired audience of the Reuchlin feud through the (supposed) identical names of the two combatants and the identification of the delinquent as a “baptised Jew” with the name “Pfefferkorn.” Hutten’s depiction of the trial, however, not only defames Reuchlin’s main opponent, invoking all the anti-Judaic stereotypes, but also engages in a virtual reckoning with the “baptised Jew,” whose punishments of shame and corporal punishment, especially in the vernacular edition, are exhibited in a visual display of violence (Figure 1).[55]

Ulrich von Hutten, Die geschicht und bekentnuß des getaufften Juden zu Halle/ vor sant Moritzen burgk auff den Jüden kirchoff mit gluͤenden zangen gerissen/ darnach gepraten (Nuremberg: Jobst Gutknecht, 1514) (VD16 H 6305), title woodcut, Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Rar. 1658.

Hutten’s elaborate Latin Exclamatio compares the burnt convert from Halle with the sinister creatures of Greek mythology, such as the gorgones, the harpyiae or the tyrant Phalaris from Sicily,[56] whom he was also to deal with in literature a little later in a satirical dialogue directed against Duke Ulrich of Württemberg (Phalarismus).[57] In this way, he certainly succeeded in activating the humanist corona, which immediately recognised the goal behind the actual attack. Hutten’s invective, with its anti-Judaic tone, not only struck a chord by being in harmony with the spirit of the times, but, through translations into German, naturally also drew a wide audience whose interest had already been aroused by the Jewish book controversy.[58] Hutten was not the only one to exploit the similarity between the two converts’ names. Many other scholars took part in this supposed controversy with their texts, such as Johannes Rhomanus’s Das ist der hoch thuren Babel, printed in 1521,[59] so that Pfefferkorn could only note with consternation that “to my shame, the Reuchlinists printed books about it as if I were the man in question.”[60] At the beginning of the first Cologne edition, which was printed by Cornelius von Zierickzee, Hutten placed a vituperative quatrain (Ad lectorem) aimed against Pfefferkorn that appeared again and again in subsequent editions.[61]

Hutten’s plan worked. It was now completely irrelevant which Pfefferkorn Hutten had meant, since this name was now associated with the attributions of monstrous crimes and ignominious punishment (illusory truth effect).[62] Thus Pfefferkorn reacted twice in his invectives to Hutten’s accusations and vituperations against him. He apparently felt particularly affected by the staging of the cruel execution on the title page of the German edition, which he addressed in a pamphlet entitled Beschyrmung Johannes Pfefferkorn (den man nyt verbrant hat) (“who was not burned”), published in 1516.[63] Pfefferkorn refers directly to the Praefatio in the extended Latin version of the pamphlet, translated by Gratius, Defensio (1516).[64] In the later Streitbüchlein (1516),[65] which appeared at the spring fair in 1517, Pfefferkorn also referred to Hutten’s Exclamatio.[66] Pfefferkorn thus accused Hutten, even at the time of his first publication, of having publicly damaged him with a multitude of vituperative texts (libelli).[67] He was right.[68]

2.1 The Epistolae obscurorum virorum (1515–1517)

The Epistolae obscurorum virorum (EOV) (Letters of Obscure Men)[69] could be described as the satirical climax of the Reuchlin controversy. The first edition of the two-volume work appeared anonymously in the autumn of 1515, and the second part of the collection was published in the spring of 1517. The reference to “Obscure Men” is itself an invective; it alludes in parodic contrast to an anthology of well-known humanists by Reuchlin, the Clarorum virorum epistolae (Letters of Famous Men)[70] of 1514; obscuri auctores were considered to be “unfamous,” insignificant authors who did not meet the standards of the humanist corona.[71] This parodic approach is also revealed in the colophon, which admittedly only shows a fictitious printing place in the form of the Venetian printer Aldus Manitius (instead of the famous Manutius). The fact that Hutten was one of the main authors of the EOV has already been sufficiently discussed.[72]

Satire[73] can be defined as a specific form of literary invective.[74] Accordingly, the aim of satire is not only to encourage the reader to laugh, but to laugh together at someone else.[75] They should – and this applies to the EOV in particular – form a “laughing or vituperative community” against the stylised adversaries.[76] Arguing against strict oppositions of humanism versus scholasticism, recent research has emphasised this group-dynamic aspect, which establishes the inclusion of the newly educated via an exclusion of certain exponents of the old elite. The object of laughter, however, the obscuri viri, are, as Hahn and most recently de Boer have shown, not simply “the” scholastics per se and certainly not monks and clerics.[77] The portrayed “theologians” are above all university scholars who are characterised by a specific form of ignorance. Shutting themselves off from the rediscovered sources of knowledge, they insist on their methods, which seem to guarantee the unassailable superiority of their learning. Nowhere is this more evident than in the first letter written by Hutten in EOV I, where a certain Thomas Langschneyderius reports on a disputation as to whether, according to convention, it should be magister nostrandus or noster magister. Research has shown that Hutten was trying to extrapolate Erasmus’s mockery of the magistri nostri. [78] For the sake of satirical self-exposure, Hutten’s presentation targets not only the “barbaric” language, but also the mind-sets and group consciousness of the opponents. The magistri nostri appear as a specific, self-affirming communicative community, as master intellectuals who arrogantly believe they are acting on behalf of the master himself, namely Christ. The “scholastic method,” as satirised by Hutten, appears here not as a truth-oriented form of argumentation, but as a performative and ritually employed strategy of self-legitimation.[79] From the point of view of this self-centred community of magistri nostri, the new intellectuals appear as questionable outsiders, as they question the sense of this method.[80] In contrast, from a humanist perspective, these theologians refuse not only to expand the textual sources,[81] but also to adopt new approaches to the textus, as manifested in Reuchlin’s philological critique. They prove, so to speak, to be incapable of criticism in a double sense. The satirical point of EOV lies in a staging of ignorance: the magistri nostri are presented as barbarians in their barbaric discourse and thus, through a strategy of “othering,” are themselves made “others,” the obscuri viri. [82]

The literary approach of the EOV consists in the counter-image: as in the model of Reuchlin’s Famous Men, a “correspondence of friendship” is imagined in the EOV, similar to what the humanists used to do in their sodalities, with the difference being that the magistri nostri continually embarrass themselves with their verbalised “Obscure Men’s Latin” teeming with solecism, barbarity and Germanism, without noticing it themselves. This invective also affects their own group. It is significant that almost all of the letters of the EOV are addressed to Ortwin Gratius († 1542)[83] from Cologne. Gratius thus became the central target of ridicule, especially as he was one of the few to be identified by his real name.[84] Moreover, he was not a “scholastic,” but originally a moderate humanist. However, he had sided with Pfefferkorn and against Reuchlin early on and translated some of Pfefferkorn’s writings into Latin.[85] Personal conflicts, with Hermann von dem Busche in particular, may have played a role here.[86] As de Boer has shown, the performative effect of the EOV consisted in a polarisation within the group of new intellectuals orienting themselves on the studia humanitatis, in which taking sides with Reuchlin translated into an obligation to position oneself and promoted the formation of a new “hegemonic humanism.” The EOV were not only directed at the scholastics, but also, as can be seen in Ortwin Gratius, at those intellectuals who were able to identify with both sides.[87]

Within this framework, the satirical profile of Hutten’s letters can only be characterised schematically. A brief overview that focuses on Hutten’s contribution must suffice here: whereas the first volume of the EOV was concerned with exposing the scholastic milieu to ridicule, the continuation of the EOV, for which Hutten was mainly responsible,[88] is characterised by a clearly more aggressive style of writing that does not shy away from obscene language and even scatological motifs.[89] It is also characteristic that in EOV II the Reuchlin debate itself becomes the object of literary depiction:[90] The Obscures inform Gratius about the latest developments in their places of residence, ask for his advice and support, but also articulate their fears and worries about the state of affairs; some letters almost bear the traits of a fictional report.

Sometimes this conflict even turns physical.[91] This is shown, for example, in the famous versified journey of Peter Schlauraff, who has to flee across Germany from one place to another and is beaten up everywhere by the local “poets.”[92] Of course, Hutten also wants to gain favour here, making his persona swear to whip Schlauraff with rods. In general, chivalrous violence is a central element of his self-portrayal.[93] Magister Silvester Gricius, for example, who writes to Gratius from Mainz, reports with horror about Reuchlin’s many advocates in Mainz, including a certain “Ulricus de Hutten, who is very beastly” and supposedly swore that if the brothers of the Order of Preachers were to insult him as they did Reuchlin, he would prove to be their “enemy” and “cut off their noses and ears.”[94] This is a function of the letters in general, to inform the recipient of hostile artists, poets and jurists who “hold it in common against you with Reuchlin.”[95] However, Gricius also shows that the other side is prepared: intellectually through Heinrich Han, alias Glockenheintz, who could push his opponents into a corner “while laughing,” and militarily through a certain Matthias von Falckenberg, who would come to the aid of Hochstraaten with a hundred horsemen if necessary.[96]

Hutten thus translates the polemical constellation of Reuchlinists and theologians into a burlesque staging of enmity and violence. The satirical depiction also offers Hutten the opportunity to counter arguments and the positioning of the theologians’ party with public effect. Magister Bernhard Gelff, for example, feels compelled to defend Pfefferkorn’s Defensio (translated by Gratius) against a curial Reuchlinist in regards to the accusation of lèse majesté and heresy, whereby of course his clumsy and hair-splitting defence makes these accusations evident in the first place.[97] In addition to this dispute over content, Hutten’s invective is aimed primarily at the players themselves, at the renegade Gratius and specifically again at Pfefferkorn, who is depicted as an uneducated and malicious character. Hutten does not shy away from activating all of the resentments against the baptised Jew or, in addition, from spreading rumours about the loose lifestyle of Pfefferkorn’s wife, who allegedly also has an affair with Gratius. The function of such insinuations is to denounce the Cologne party in its entirety as a camarilla linked by impure relationships. The final reckoning is carried out by Gratius’s uncle, of all people, allegedly an executioner, whom Hutten has imagining (in a way analogous to the trial of the alleged Pfefferkorn in the Bekentnuß) burning the “illuminati in fide catholica” Hochstraaten, Arnold von Tongern, Gratius and Pfefferkorn, in order to produce in this way a great illumination of the world, “brighter even than the light of Bern.”[98]

How provocative these productions of EOV II must have come across only becomes understandable when one takes into account that even humanists had previously expressed criticism of the magistri nostri rather cautiously.[99] Paradigmatic of this is Erasmus’s thoroughly biting but ironically displaced mockery of the theologians in his Moriae Encomion, whom he pretends to pass over in silence, yet compares to the malodorous plant anagyros or the “Camarinian marsh.” Shields has pointed out the complexity of this allusion, for it is also the Camarine swamp, as Erasmus points out in his Adagia, who saves the city, i.e. Christianity in the context of the allusion, from worse things. Moreover, the mocking speaker is also amused by the new intellectuals’ “Greek obsession,” and thus cushions the attack on the theologians’ party.[100] EOV I is also content for long stretches with mocking the barbarism of the scholastic milieu by the indirect means of mimic satire and thus specifically identifying the Cologne magistri as being unable to ally with the diffuse group of those interested in the studia humanitatis. [101] In contrast, in the EOV II, Hutten depicts the struggle of both parties, admittedly in the distorted optics of the oppressed theologians, who know no other way to help themselves than by framing this conflict as a battle of faith (causa fidei), thereby demonstrating their ignorance.[102] The denunciation of mimic satire does no longer aim at the milieu in general, but at specific opponents of Reuchlin namely Gratius, Pfefferkorn and Hochstraaten, against whom Hutten is happy to adopt almost any means.

How did friends and opponents react? The aggressive gesture of the Obscure Men’s Letters did not meet with uniform approval in their own camp. Erasmus, for example, distanced himself from it because he was convinced that the studia humanitatis had suffered considerable damage, as had the amicitia cultivated in the humanist sodalities.[103] Reuchlin himself found the “exuberance of youthful frivolity,”[104] as he once ironically called the EOV, probably just a bit excessive. His main opponent Pfefferkorn, by contrast, promptly responded to the slanders of the EOV I with the above mentioned pamphlet Beschyrmung (1516), translated by Gratius under the title Defensio […] contra famosas et criminales Obscurorum virorum epistolas (1516) in an expanded version.[105] The inclination to compose one’s own invectives from a defensive stance is thus also encountered by the opponents of Reuchlin.[106] Pfefferkorn also addresses the individual accusations made against him by the Reuchlinists. For example, the magistri nostri were insulted as devils and the Parisians were slandered as unfair judges because they had accepted funds from the people of Cologne. It is precisely at this point that it becomes clear to what extent metainvective thematisations could also be inscribed in the degree of scandalisation of dynamic disputes.[107] He laments to the pope and his cardinals, requesting help against Reuchlin’s followers. Otherwise, he said, there was a danger of sectarianism worse than any that had ever existed before.[108] At the same time, he also compiled the mentioned Streitbüchlein (1516) from all kinds of testimonies, a work conceived as a supplement to the two aforementioned pamphlets. In four chapters, Pfefferkorn outlines the course of the dispute from his point of view in order to continue to promote his own cause and carry the fight to broader sections of the population.[109] A “colleague,” Ortwin Gratius, who had become his main opponent in the EOV, continued to react to the vituperative letters in form of a parody in which he tried to retaliate tit for tat. Under the title Lamentationes obscurorum virorum (1518),[110] a fictitious collection of letters also appeared under his name, a two-volume invective that intended to parody the satire of the “Obscure Men” once again. These letters suggested the idea that the fictitious authors of the EOV were real people who had merely posed as Cologne scholars in order to turn the tables, at least from the point of view of Gratius and the Cologne theologians. In the aftermath of the fictitious letters, these “contra-obscures” immediately broke out in broad lamentations against those whom they held responsible for the EOV. They railed against those who printed, distributed or read them. “One representational goal, above all, is their ‘realisation’ that unquestioning devotion to the classical model authors of the humanists causes a neglect of the Christian faith that ultimately leads to eternal perdition.”[111] However, it was not only the text that was to be satirised, but also, as it were, the successive publication and the title woodcut of the EOV.[112] Thus the first part (45 letters) was published for the Easter Fair on 15 March 1518, and the second edition (Lamentationes novae obscurorum virorum), which was supplemented by 40 further letters, in August of the same year.[113] Moreover, while the woodcut originally used in the first edition of the EOV II still caricatured the scholastic “Obscure Men,” an attempt was made to transfer this image iconographically in the Lamentationes. These, too, depict “Obscure Men,” but in this case, they stand for the humanist adversaries, the “Reuchlinists.”[114] Among them are Jews, Turks and false preachers, all of whom have their erroneous path whispered to them by winged devils, symbolised by the attributes of the candle and the bellows. One exception, however, is the figure in the background, who can probably be identified as a papal inquisitor. In the meantime, he is pronouncing an ecclesiastical ban on the enemies of Rome, a threat that can certainly be understood as such.

2.2 The Triumphus Capnionis (1518)

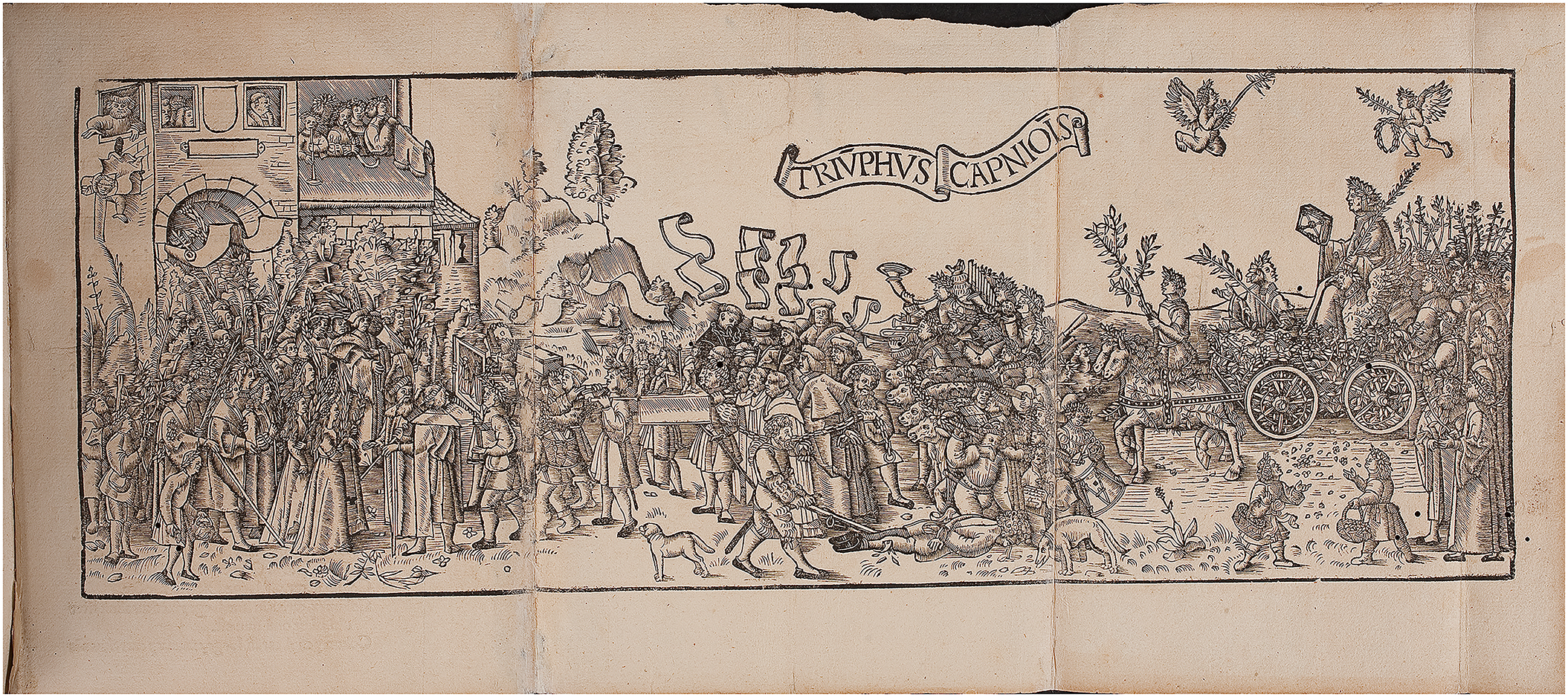

Hutten had already been working on a poem in praise of Reuchlin since 1514/15. However, the Triumphus Capnionis, a solemn hexameter epyllion of 1063 verses, was not printed until 1518 by Thomas Anshelm in Hagenau. Erasmus immediately thought he recognised Hutten’s pen behind it, again advising him against publication so that no greater damage would be done to Reuchlin. Mutian obtained a copy of the text in Erfurt probably as early as June 1514, while the humanist circle around Willibald Pirckheimer in Nuremberg probably had the eagerly awaited work in their hands in 1517. The Triumphus describes Reuchlin’s triumphal entry into his hometown of Pforzheim in grandiose hexameters, whereby Hutten not only borrows from the model of an ancient Roman triumphal procession, but also joins a longer contemporary tradition of such literary descriptions.[115] The preface, addressed to the emperor and the “German people,”[116] refers to the temporary suppression of the trial by Bishop George of Speyer and at the end to the EOV. Here Hutten also indirectly acknowledges his authorship.[117] In his concluding remarks, he attempts to raise the scholarly debate to a national level.[118]

The first edition of the text also came with a sophisticated woodcut that very clearly outlines Hutten’s programme and the intentions he associated with this invective.[119] However, since it is not accompanied by any further notes in a legend, it cannot be interpreted at all without the explanatory hexameters.[120] The triple-page, enormously elaborate woodcut (Figure 2) shows Reuchlin triumphantly entering his hometown of Pforzheim, seated on a triumphal chariot, a carriage of two, and flanked by flower children, Italian and German humanists, poets and jurists (ll. 990–1046). The procession is led by a number of sacrificial offerings, such as four cattle, as well as numerous musicians. While Reuchlin, crowned with a laurel wreath on his head (l. 1011), also holds a laurel branch in his left hand, he demonstratively holds up a code of his Augenspiegel (“oculare speculum,” l. 1013) in his right hand to emphasise its European effects.[121] In the centre of the picture, the opponents, the Cologne magistri, are also positioned as a group, but chained (ll. 382–473).

Woodcut, inserted in the first edition of Hutten’s Triumphus Capnionis (1518), folded four times in original size. Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Inv. no. 95.2 Theol. 14s.

In the Triumphus Hutten describes in detail that the booty carried by the theologians on stretchers and in the hands of servants are “figurative representations” of the deities of the defeated, e.g. Superstition.[122] According to Hutten, the books and boxes in the middle of the woodcut embody the false arguments of the false theologians.[123] One in particular stands out among the opponents, however, because his tongue, also in the form of a chain, winds around his neck like a strangling snake when he speaks. This is apparently the Dominican and papal inquisitor Jakob von Hochstraaten, whom Hutten also intends to consign to the flames as revenge for the burning of the Augenspiegel.[124] Thus he appears as the leader of a criminal caste of “Obscure Men” (viri obscuri, l. 504),[125] to whom Hutten counts not only Hochstraaten but also Arnold von Tongern, Ortwin Gratius[126] and Peter Meyer from Frankfurt/Main.[127]

Even more so than the woodcut of the Exclamatio, the famous woodcut of the Triumphus illustrates Hutten’s fantasies of violence quite impressively. The picture of the main opponent, Pfefferkorn, is particularly drastic here: he lies in the mud, bound, at the feet of his torturers, and has had a scythe (uncus) driven into his calves by one of the henchmen, who drags the Cologne convert behind him.[128] In the course of this depiction, not only is his tongue cut out, but he eventually vomits,[129] so that the vomit can then be licked up by a dog in imitation of one of St. Peter’s letters.[130] Such scenes of cruel execution excesses became a popular stylistic device in the imagery of the early sixteenth century.[131] Nevertheless, for Hutten, in the course of his elaborate invective, we see in this very example the idea of wearing down the opponent and involving his confederates in the conflict in the sense of a logic of outbidding (aemulatio). Thus, we not only see the procedural character, i.e. the character that prepares or initiates a physical conflict, but also a highly dynamic group character. Collective vituperation is a highly socio-cultural act. This explains the immense entertainment value of Hutten’s humanist text-image invectives.[132]

3 Conclusion: Determining Functions of Humanist Invectives in the Pre-Reformation Debate

Hutten had become close to the well-known and well-connected scholar Reuchlin early on, as evidenced by the publication of a joint edition of works in 1513,[133] which reproduced both Reuchlin’s early comedy Henno [134] and Hutten’s dialogue Nemo from 1510. Unfortunately, due to the disappearance of records, countless letters from the correspondence between the two have been lost, so that only two of Hutten’s have survived, but Reuchlin’s replies to them have not.[135] While in the first letter of 13 January 1517 Hutten still reports hopefully of the perceptible unity “among the Reuchlinists” (inter Reuchlinistas),[136] in the later letter of 22 February 1521 from the Ebernburg (belonging to Franz von Sickingen), he is so incensed at what he saw as Reuchlin’s fundamentally changed attitude[137] that he even lets himself get carried away to a downright epistolary invective against the renowned scholar. Hutten was undoubtedly most agitated by the fact that Reuchlin had not only betrayed his own cause, but rather the struggle of his followers.[138] Reuchlin, meanwhile, tried several times to consult the responsible judges by letter in order to appease them and win a more lenient sentence and finally settle the case. To achieve this goal, in a letter to the curial Jakob Questenberg from Stuttgart on 12 February 1519, he also swore by the Styx, the river of death of the underworld, that he did not know the author of the Triumphus Capnionis.[139]

It is precisely the violent fantasies of the woodcuts in Hutten’s texts that show the complementarity of invective’s twilight zones, for these too were intended to inspire collective mockery and ridicule and, due to their imagery, admittedly make the dynamics of invective communication particularly three-dimensional.[140] It is only through this complementary understanding that it is at all possible to locate and name borderlines of “invectivity.” However, physical and violent language in text and image can not only be amusing,[141] but also have a socially cohesive function.[142] Appearing as a group further increases their power to push the opponent out of the common circle of recognition and to urge a public counter-attack. The power to interpret whether a crude joke is in bad taste or taboo-breaking thus becomes apparent precisely in the dynamics of these invectives’ grey zones and tipping points.[143] At this point, we might also raise the question if humorous elements might have aimed at alleviating some blatantly crude insults. Ridiculing might have distracted the readers’ attention from any superficial glorification of violence while cushioning its effects.[144]

In any case, it is a fact that Hutten’s action also turned into actual threats of violence. At a meeting in Stuttgart in 1519, he had already won over the condottiere Franz von Sickingen for the Causa Reuchlini.[145] When Reuchlin was still to be sentenced to pay the costs of his Augenspiegel trial in Rome, Sickingen unceremoniously declared a feud against the Dominican provincial Eberhard von Kleve for 29 July 1519.[146] In doing so, he demanded the cessation of the polemics of the Cologne Dominicans, the dismissal of the inquisitor Jakob von Hochstraaten and the reimbursement of the 111 guilders in legal costs. Eberhard subsequently had to appear at Sickingen’s Ebernburg (“Inn of Justice”)[147] and submit – at least the treaty of 10 May 1520 from Landstuhl seemed to indicate this at first. At the same time, however, contrary to Sickingen’s expectations, the Dominicans had intensified their efforts in the trial against Reuchlin and were ultimately able to obtain a final judgement in Rome on 23 June 1520.[148] Reuchlin, who had in the meantime retreated to Ingolstadt, subsequently showed a fundamental change of attitude in relation to the path taken by Sickingen in a letter to Willibald Pirckheimer from Nuremberg.[149] “Franz von Sickingen’s intervention with his threat of violence brought this result to Reuchlin, who had always spoken out against its use, but had succumbed here to Hutten’s and Sickingen’s whisperings.”[150]

The results and findings of the study examine Hutten’s involvement in the Reuchlin controversy more closely on the basis of selected examples and define the function of humanist invectives. In fact, Hutten was also involved in the Reuchlin conflict with other invectives, which, however, must be dealt with elsewhere.[151] In all cases, it becomes apparent that Hutten was not only one of the most zealous and productive Reuchlinists, but also that productive or destructive effects or even functions of (literary) invectives can only be determined and understood within the framework of their specific event contexts and normative horizons. Thus Hutten, with the help of a rhetorical trick in the Exclamatio (1514), also succeeds extremely efficiently, for example, in publicising participation in the Reuchlin conflict by simultaneously activating mistrust against the baptised Jew. In the Epistolae obscurorum virorum, Hutten recalls the tensions between old and new intellectuals, whereby the “theologians” are mocked and ridiculed within the framework of mimetic-satirical self-exposure.[152] Finally, the Triumphus Capnionis (1518) refers to the Reuchlin–Pfefferkorn conflict itself and depicts the victory of the humanist scholar together with the ignominious treatment of his barbarian opponents and the cruel execution of Pfefferkorn, captured in the impressive title woodcut, showing him mutilated and humiliated at the feet of the poeta triumphans in the lower centre of the picture. To describe Hutten’s interventions as invectives therefore means not only to work out their disparaging intentions and effects, but also to analyse them from their communicative context. This communicative context can ideally be described as a triadic constellation in which Hutten not only targets the invected object, e.g. Pfefferkorn and the Cologne magistri, but also addresses an audience at the same time, since the invective unfolds its tangible effect only in front of a specific public or in an arena.[153] Hutten’s interventions must always be placed in the context of humanist group dynamics; they are fundamentally situated in the ambivalence of self-fashioning and community-fashioning.

Beyond this, however, the analysis must also take a look at the concrete literary forms and modes of depiction. Characteristic of Hutten’s interventions is an expansion of the spectrum of invective procedures, whereby the body also becomes a medium of invective.[154] Thus, Hutten enacts the defamation and virtual destruction of Pfefferkorn with the violence-saturated depiction of the execution of the delinquent in the Exclamatio; likewise, the EOV and the Triumphus Capnionis also work with violent, obscene and scatological elements of presentation. This has certainly always been part of the repertoire of the invective, as can already be seen from Cicero’s invectives against Piso. In the context of self-fashioning, these procedures can be traced back to an agonal strategy of surpassing the positioning of one’s own group and sharpening one’s own profile, which for Hutten always includes one’s own capacity for violence. In the context of the Reuchlin debate, Hutten’s invectives nevertheless produced an invective surplus, which has not only irritated the early researchers of the twentieth century, but also his contemporaries. Hutten’s way of writing is based on an ostentatious and provocative dissolution of the (literary and also medial) momentum of the invective. We find the depiction of violence particularly significant, whether in the trial of the alleged Pfefferkorn, the beating of magister Schlauraff, or the virtual funeral pyre for Gratius and his consorts, or finally in the punishment and humiliation rituals to which, for example, Pfefferkorn and Hochstraaten are subjected in the Triumphus Capnionis. While Erasmus is content to undermine the theologians’ self-assured claims to validity, and thus their discourse, Hutten also depicts the humiliation and depotency of the “theologians” on their bodies. Hutten’s invectives tie in with the hostility of the Reuchlin debate, which the Cologne magistri evoked against Reuchlin as a prospective heretic and which Reuchlin himself, for example in his Augenspiegel, turned against the Cologne magistri. Hutten extrapolates and functionalises them in the context of a comprehensive, cultural-political project aimed at driving barbarism out of Germany, whereby for Hutten a decidedly anti-Roman aspect also becomes increasingly decisive.[155] Against this background, the function of the literary invective can be described more precisely: now Pfefferkorn and the theologians are declared criminals in fictional scenarios, with their punishment and destruction being in a sense anticipated in literary fantasies of violence. This invective poetry has a performative dimension; it is no longer merely a matter of entertaining the corona as a laughing and mocking community and consolidating it in the sense of a hegemonic humanism, but of mobilising it against its enemies. Erasmus criticised the implicit pressure – indeed compulsion – to position oneself and described it as a breach of humanist norms of communication. For Hutten, this was the consequence of the literary warfare situation: true to the dictum, he attested to himself at the height of his writing activity: “by hook or by crook.”[156]

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Words at War: “Invectivity” in Transformative Processes of the Sixteenth Century. An Introduction

- Research Articles

- Ulrich von Hutten’s Partisanship in the Reuchlin Controversy (1514–1519): Determining Functions of “Invectivity” in Early Sixteenth-Century German Humanism

- Invectives as a Stylistic Device in Martin Luther’s Reformation Rhetoric

- Grobian Trouble: Grobianism and “Invectivity” in Thomas Murner and Martin Luther

- “Invectivity” and Theology: Martin Luther’s Ad librum Ambrosii Catharini (1521) in Context

- Deconstructing Memory Johannes Cochlaeus’s Life of Martin Luther between Polemics and “Invectivity”

- “Invectivity” and Interpretive Authority: Religious Conflict in Kilian Leib’s Annales maiores

- “zu grob gewest”: Metainvective Communication in Confessional Disputes over Narration of the Saints in the Sixteenth Century

- Winner of the REFORC Paper Award 2022

- “Nit allein den rechtglaubigen, sonder auch den irrigen: Two Sixteenth-Century German Catholic Prayer Books as Tools of Re-Catholicisation”

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Words at War: “Invectivity” in Transformative Processes of the Sixteenth Century. An Introduction

- Research Articles

- Ulrich von Hutten’s Partisanship in the Reuchlin Controversy (1514–1519): Determining Functions of “Invectivity” in Early Sixteenth-Century German Humanism

- Invectives as a Stylistic Device in Martin Luther’s Reformation Rhetoric

- Grobian Trouble: Grobianism and “Invectivity” in Thomas Murner and Martin Luther

- “Invectivity” and Theology: Martin Luther’s Ad librum Ambrosii Catharini (1521) in Context

- Deconstructing Memory Johannes Cochlaeus’s Life of Martin Luther between Polemics and “Invectivity”

- “Invectivity” and Interpretive Authority: Religious Conflict in Kilian Leib’s Annales maiores

- “zu grob gewest”: Metainvective Communication in Confessional Disputes over Narration of the Saints in the Sixteenth Century

- Winner of the REFORC Paper Award 2022

- “Nit allein den rechtglaubigen, sonder auch den irrigen: Two Sixteenth-Century German Catholic Prayer Books as Tools of Re-Catholicisation”