Abstract

This article intends to lay out a comparative study of Karma philosophy and literature scrutinizing Yann Martel’s novel Life of Pi through a panentheistic approach. Because Karma is one of the predominant philosophies in the novel and permeates the general atmosphere, this article intends to scrutinize Yann Martel’s novel Life of Pi through a panentheistic approach. Although karma is a very complex issue, since anyone committing evil acts can claim to be a mere agent of karma delivering punishment to others for sins they committed in their past lives, it is true that according to karma, our actions have consequences which affect the entirety of our lives, and this can also be seen as free will. Yet while this approach tends to focus on the action and reaction mechanisms of life, the flow of life in the universe should still be carefully contemplated, since if we believe the first story, Pi’s survival not only depends on his choices, but also on the opportunities that the universe offers him. In that sense, if we are to accept God as the soul of the universe, then the universal spirit must be omnipresent and omnipotent while also capable of transforming into anything in terms of s panentheistic approach. Thus God, being greater than the universe, is the ultimate force that balances everything, and is also the biggest karma controller. For this reason, this article analyzes Life of Pi from both inductive and deductive slants to demonstrate that all roads lead to God, the omniscient.

Introduction

It is not a new intention for humans to seek to understand the mechanisms of the universe. Throughout history, humankind has located itself in various centers of life known to exist and has also sought the presupposed life after death, which can neither be experienced nor conquered by humans, except through mythical heroes such as Hercules, Odysseus, Gilgamesh, and so on. Yet, in contemporary time, intellectual approaches consistent with the rise in technology (especially through the industrial revolutions) have co-existed within empirical methods and surrounding humanity, leaving almost no time for debates on metaphysics. Although some critics, including Lewis Mumford, tend to build a direct correlation in terms of mutual development among human tools, and social organizations via rituals and language (Mumford 12), in the present time, when we are experiencing industry 4.0, it might be hard to keep myths alive against the bizarre machinery at work.

In Life of Pi, two different stories are interwoven, each sustained through different perspectives. Notwithstanding the fact that karma, as one of the pre-dominant philosophies in the novel, permeates the general atmosphere, this article focuses on Yann Martel’s novel Life of Pi through a panentheistic approach. While karma is a highly complex issue, since anyone committing evil acts can claim to be a mere agent of karma delivering punishment to others for sins they committed in their past lives, it remains true that according to karma, our actions have consequences which affect the entirety of our lives, and this can also be seen as free will. Yet while this approach tends to focus on the action and reaction mechanisms of life, the flow of life in the universe should still be carefully contemplated, since if we believe the first story, Pi’s survival not only depends on his choices, but also on the opportunities that the universe offers him. In that sense, if we are to accept God as the soul of the universe, then the universal spirit must be omnipresent and omnipotent while also capable of transforming into anything. In other words, if we consider that the entire universe is a simulated order created by God, it may be easier for us to approach the novel from a panentheistic point of view. First of all, let us consider that every individual and even every living thing, regardless of which religion or belief they subscribe to, is a model formed in the studio of (the) God. Alternatively, we can assume that each of us is a coded individual, just as a programmer encodes characters in a computer game. Karma claims that not only for physical actions, but also for any mental actions, the consequences are inevitable. It represents a causality rule which states that everything we dream of, or the consequences of every action we perform, will affect us in this world or the next world. To be clear, even if the result of every action taken does not manifest itself in the world we are in now, it will certainly have consequences in the next life. In accordance with the Panentheistic approach, an arbiter is required for this balance to continue, and for the final cycle to continue in an order whereby the balance of causality is established. The scales of justice, which are both above and outside of everything, and whose presence or absence does not affect anything else, is an unshakable force: “Like most versions of ‘theisms,’ panentheism is about mapping relationships: between the self and the world, between the self and God, and between God and the world…” so that “it affords the possibility of a permeability between God and the world, a dynamic that offers God in matter and God as transcending matter” (Biernacki and Clayton 2). Thus God, being greater than the universe, is the ultimate force that balances everything, and is also the biggest controller of karma. For this reason, all roads lead to God, the omniscient.

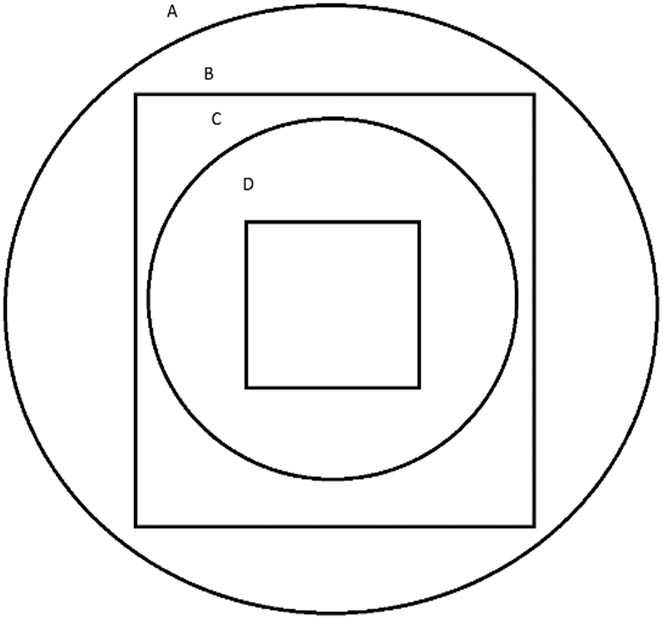

Considering a panentheistic view entangled with the philosophy of karma, Yann Martel’s Life of Pi is a multi-layered novel that encapsulates different modes, placing the novel in more than one genre. In other words, in parallel with that which the aesthetics of reception allows, the reader can see a fable, children’s literature, a fantasy novel, a theological story, a non-theological story, or even a science-fiction story. It is possible to maintain a critical approach through any of the sub-genres and theories, although the novel is not limited to these. The story is set in a highly intriguing atmosphere, whereby an Indian boy finds himself in a lifeboat following a shipwreck, with an “anthropomorphic-like” Bengal tiger that does not actually speak, but, as perceived through Pi’s instincts, chooses to accompany him throughout their spiritual and physical odyssey. Life of Pi begins as an ordinary story and ends in an unusual fashion as Mr. Adirubasamy states “that will make you believe in God” (Martel 7) if you prefer to see the story in either of the alternative endings. In these two alternative endings, as readers “we tend to define our humanity by drawing a line between it and our animality, where the human is defined by a boundary excluding the animal” (Mensch 135). Except for those times when Pi talks about his early childhood and memories, such as how he changes his name or what he does in the zoo, most of the novel focuses on Pi’s physical and spiritual odyssey in the Pacific Ocean. The choice of this ocean is noteworthy since “the Pacific Ocean, body of salt water extending from the Antarctic region in the south to the Arctic in the north and lying between the continents of Asia and Australia on the west and North and South America on the east” (Morgan et al.). The position of the Pacific Ocean to continents is analogous to Pi standing between different beliefs. It is like taking a piece of them all and blending them to achieve the perfect harmony. Similar to what ancient philosophers such as Thales or Anaximander (see Cohen et al.; Sassi) did, Pi strives to grasp the balance between his existence, the cosmos, and the creator. He remains in an atmosphere of solitude, completely isolated from the rest of the world. Much like the beginning of the universe some 13 billion years ago, with an explosion in the ship reminiscent of the Big Bang, Pi finds himself surrounded by a vast ocean: “[W]ater – the stuff of our oceans – has been virtually everywhere, from close to the beginning of time itself” (Zalasiewicz and Williams 2). Apparently, Piscine Molitor Patel is left to solitude as the so-called lone man on earth, who seeks to find the meaning of his connection with nature and his very own link with the creator. Depending on his intuitivist perceptions, Pi syndicates bits and pieces of the ocean with every single breath he takes. He suffers the utmost fear living between a hyena and a Bengal tiger, Richard Parker, a tiger with a human name who is wrongly named after a hunter. The dilemma between life and death is in point of fact the predicament of “[t]he finite within the infinite, the infinite within the finite” (Martel 70). Therefore, Pi, a finite man, experiences infinity through God’s essence. This essence is ever-ready in nature from the angle of a panentheistic approach. God persists in nature; nature persists in God. In that sense, if Pi (as a name) is inspired from the number π, mathematically speaking, the relationship between God, cosmos, nature, and life can be best described as follows:

In the set above, “A” represents God, “B” represents the cosmos, “C” represents nature, and “D” represents all forms of life. As B, C, and D coexist as the subsets of A, none of them exists without the presence of A. This actually means that the beginning of everything is in God, and the end of everything is again dependent on God’s will. Since everything begins with God and is at God’s center, it is possible to feel the presence of God and to see God in every material that exists. God is everywhere and in everything. God is the life-giver and life-taker, who can transform into anything: “Thank you, Lord Vishnu, thank you!” I [Pi] shouted. “Once you saved the world by taking the form of a fish. Now you have saved me by taking the form of a fish. Thank you, thank you!” (Martel 267). God is Vishnu, God is Father, and God is Allah. God is also nature, and thus nature is God. Whatever you do in nature will have a resonance, because the God who is the object and subject of everything is essentially karma itself.

God can be anywhere, anytime, and in any form. From both the deductive and the inductive senses, the voyage of anything descending either from God or, conversely, from life on earth, the spherical voyage of any person or anything, both circulate in God. Thus, as Noble Quran warns: “Doubtless we have descended from the God and again our coming back will be to him” (The Quran 2:156). “Then we who are alive, who are left, shall be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air; and so we shall always be with the Lord” states the Holy Bible (1 Thessalonians 4:17). In that respect, this analysis defines Pi’s spiritual and physical odyssey through panentheism to understand Pi’s own Karma, which excludes nothing but includes a variety of religions and beliefs in terms of “[i]f there’s only one nation in the sky, shouldn’t all passports be valid for it?” (Martel 106). Because Martel’s Pi has a cumulative approach to God through an amalgamation of Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam, this article holds a panentheistic approach to portray an analysis of Life of Pi in order to gain better insight into Pi’s spiritual voyage, a voyage which extends beyond the physical.

Panentheism in Life of Pi

Panentheism as a philosophy “affirms that although God and the world are ontologically distinct and God transcends the world, the world is ‘in’ God ontologically” (Cooper 18). God exists as the Life Force, the dynamic Spirit that generates life, intelligent order, and oneness in the universe. When life depends on absolutely thin layers, Pi realizes that between himself and Richard Parker and other animals, there is the same instinct to survive at any cost:

A shiver went through my body. Between the life jackets, partially, as if through some leaves, I had my first, unambiguous, clear-headed glimpse of Richard Parker. It was his haunches I could see, and part of his back. Tawny and striped and simply enormous. He was facing the stern, lying flat on his stomach. He was still except for the breathing motion of his sides. I blinked in disbelief at how close he was. He was right there, two feet beneath me. (Martel 201)

Except for his faceoff with Parker, vast nature lies beyond Pi, and it functions as both life-giver and life-taker. Abundant life exists in a well-proportioned system. Pi is stuck in the ocean, the source of the first natural life on earth. In other words, forming 75% of the world, water is one of the primary elements of the life cycle and the human body. It is where everything started, and it is where everything ended and re-started for Pi. Having lost his family, Pi seeks to redeem himself from his pain. Surrounded by the Pacific Ocean, he has nowhere to go physically. However, overwhelmed by the ocean, Pi understands that the real voyage is not from the ocean to the land, but from nowhere to the core of his beliefs. Having experienced the utmost velocity of spinning around Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism, Pi sets his soul free into the depth of all beliefs. The notion of his belief has a close relationship with what he dreams or really experiences in his quest: the island of algae. Standing alone in the middle of nowhere, this island has a symbiotic life form. Pi later understands that algae have a deep connection with tree trunks and roots. They are interconnected and have a symbiotic relationship. This life form is actually a representation of Pi’s connection with God. That is, if the trees (strictly connected with algae) Pi sleeps on and spends his time in are the strongest and most solid forms of the island, similarly, he is spiritually connected to God, Allah, Vishnu, Mohammed, or Jesus in many ways. Like the form of algae that through interconnectedness creates a chemical chain, anything in this universe, planet, or nature is connected to each other, and thus to the creator. And while names and religious practices can differ, the veins ultimately link Pi to God. Therefore, the mechanisms of nature are cycled by the universe. The universe is driven by God, and he/she is omnipotent, omniscient, and ever-ready everywhere, from every single corner to every single atom that forges the universe: “[i]f all things are in God or the world is God’s body, then humans of both genders from all ethnic groups and social classes are included in cosmic salvation. God shares all human oppression and suffering, and all humans share in the life of God, which is liberating and enhancing the universe” (Cooper 299).

Pi is happy at times in his journey (exactly 227 days), which takes almost a year. At other times, he is in complete despair. Similar to the relationships between Brahman–Atman, Yin and Yang, or God–Satan, Pi’s paradoxical survival depends on himself and his tacit skills, but mostly on what God offers to him. If we recall the island of algae, there are so many aspects of the island that are literally all-inclusive, and the secret of everything is undetectable, just as the undisclosed decisions of God. The dynamics and mechanisms of the island are difficult to understand. It is amazing that the ocean turns saltwater into fresh water and gives a refreshing re-generation and power to maintain the survival instincts of Pi and Richard Parker as carnivorous and consuming creatures. Taken from another point of view, the universe seems to be in a parallel cycle. The universe within the power and might of God performs the circulation of God’s life-giving and life-taking. While this power takes life, it gives back in another form, as Parker allegedly makes Pi hold strongly to life: “This was the terrible cost of Richard Parker. He gave me a life, my own, but at the expense of taking one. He ripped the flesh off the man’s frame and cracked his bones. The smell of blood filled my nose” (Martel 369).

Consequently, in accordance with the deductive and inductive approaches, the island of Algae is actually a microcosmic projection of the macrocosmic universal structure: “The algae naturally and continuously desalinated sea water, which was why its core was salty while its outer surface was wet with fresh water: it was oozing the fresh water out. I did not ask myself why the algae did this, or how, or where the salt went” (Martel 388). On the surface, algae seems to play a minor role in the entire universe, whereas it becomes a significant utility for Pi to understand what surrounds him. Therefore, although algae is a remarkable part of the eco-system that constructs the island, it also signifies Pi’s grand spiritual journey into his faith. As his spiritual journey becomes the ultimate guide for him to understand the mechanics of the universe, both microcosmic and macrocosmic analogies intertwine. The panentheistic point of view may actually be the form that represents the integrated or embodied belief in more than one modern religion, which asserts lives are the reflections of God. Therefore, such a tendency subsets modern religions and forges a decent understanding of the path to Pi’s attitude. As Noble Quran asserts: “[t]he path of God, to whom belongs everything in the heavens and everything on earth. Indeed, to God all matters revert” (The Quran 42:53). According to John Wesley, founder of the Methodist tradition:

God is in all things, and … we are to see the Creator in the glass of every creature; … we should use and look upon nothing as separate from God, which indeed is a kind of practical Atheism; but with a true magnificence of thought, survey heaven and earth and all that is therein as contained by God in the hollow of His hand, who by his intimate presence holds them all in being, who pervades and actuates the whole created frame, and is in a true sense the Soul of the universe. (quoted in Biernacki and Clayton 75)

As can be seen, Pi’s philosophy of grasping the universe is actually the structure of a collective thought that can be found in Islam, Hinduism, and Christianity: if God is the owner and creator of all, and if everything in the universe is the reflection of God and the reflection of the universe, and nothing can exist without God, then it would be possible for Pi to reach God, whether through Islam, Hinduism, Christianity, or all three. Because just as on the island all algae and trees are connected and maintain life, give life, or take life as a whole system, each belief is in the same manner connected to one another. Likewise, since the owner of the universe is the only singular entity, it is trivial to consider in which line you remain, because the owner of all lines is the same.

“God is always doing geometry,” is a famous statement by Plato (see Plutarch 119). Like Plato’s cave story, some people deny the truth when they see it, even if everything is exposed. Denial is actually one of the easiest things a person can do. This is because accepting is to believe in the existence of something, to fulfill the responsibility of that belief, and therefore to undertake a mission. In contrast, choosing to disbelieve and deny the truth means avoiding the responsibility of proving the existence of anything. Seeing Pi’s story completely fabricated in this context can be comforting to the novel’s audience. Just as in the world of Plato, when people who are accustomed to living in a cave in the dark suddenly go out, seeing things they never thought existed before, it often means the destruction of all of the phenomena they had known until that point – everything they knew. As Avicenna states, no one can be more blind than a person who does not want to see. In this respect, the two Japanese inquisitors fully intend not to believe Pi’s first story, which involves a hyena, a zebra, a tiger, and an orangutan. Just like the story, man is constantly being kept in a cave, and even when he goes out, he cannot understand the things he sees, nor can he transmit the things he witnesses to the people who do not even know how to speak. Pi never asks the Japanese investigators if they believe any of the stories but, rather, if they prefer any particular version. Nevertheless, as in the case of Plato’s cave, the Japanese investigators argue that the things they have not experienced do not exist. Assuming that everything which is experienced is actually a part of God, no further evidence is needed to verify God’s existence. However, the investigators realized that when they had first presumed that bananas could not float on water, but then found that they were wrong, they understood that even if something could not be ruled out because it had not been verified or confirmed by their own personal experience, that did not mean that what they had not practiced did not exist at all:

‘I’m sorry to say it so bluntly, we don’t mean to hurt your feelings, but you don’t really expect us to believe you, do you? Carnivorous trees? An algae that produces fresh water? Tree-dwelling aquatic rodents? These things don’t exist.’ ‘Only because you’ve never seen them.’ ‘That’s right. We believe what we see.’ ‘So did Columbus. What do you do when you’re in the dark?’… ‘The story with animals.’ Mr. Okamoto: ‘Yes. The story with animals is the better story.’ Pi Patel: ‘Thank you. And so it goes with God.’ [Silence]. (Martel 425, 457).

The allusion to Plato’s cave, darkness, and Columbus is a very intelligent reference, since the things that are believed are inclined to change in parallel with reason and technological developments. Perhaps the problem Pi is pointing to occurs here. Can science prove the existence of God? Does God have a formula? If not, why do we still believe in God? If we don’t need evidence to believe in God, why do we need science to believe in things that sound extraordinary?

Consistent with the panentheistic philosophy, it is a peculiar essence of the creator of everything, who perpetrates a thing into everything with ease and order, and who also artily perpetrates everything into a thing in balance “… that may all be one; even as you,…. I in them and You in Me, that they may be perfected in unity” (NASB-Amplified Parallel Bible, John 17:21–23). As the creation of God, the cosmos reflects the presence of God through every entity in it. A human who takes a journey in the cosmos may see and experience the reflection signifying his oneness as the creator and beholder of every entity, including the cosmos. Every substance in the cosmos, from the system of a bacterial lifecycle to the solar system, or to the systems of galaxies, has such a perfect working balance, order, and harmonic system that it leaves no space for failure or haphazardness. Nothing in that perfectly created harmonic system is coincidental. In this regard, Pi is able to reach the existence of God as a creator and organizer of the perfectly created cosmos, despite being in the middle of nowhere in the ocean. Pi can see the reflection of God in Richard Parker, who accompanies Pi in such harmonic circumstances, ordered in balance through the novel. Richard Parker is the reflection of God, which Pi can see when he manages to grasp that the circumstances he experienced with Richard Parker are not coincidental and are perfectly organized by God. God created humans as “a thing,” a reduced, micro sample of the cosmos that is “everything” and at a macro level in terms of degree: “There is not a thing but with Us are its stores, and We send it down only in precise measure” (The Quran 15:21). Hence, a human is a seed of the genesis tree, the core of every entity in the universe. Everything and each human in the cosmos comprises a world within it, which is idiosyncratic. The idiosyncratic worlds are core components of the cosmos, which is idiosyncratic as well, and components of God hold the junction of it all. Pi and Richard Parker embrace a world unique to them in their self-individuality, which is also encompassed by God. In other words, Pi, Richard Parker, and God are all linked to one another. Thus, they are living in a symbiotic form of a panentheistic universe.

By the same token, Pi reaches the creator not only through religious motives, but also through observation and reason: “It was my first clue that atheists are my brothers and sisters of a different faith, and every word they speak speaks of faith. Like me, they go as far as the legs of reason will carry them – and then they leap” (Martel 40). As Pi emphasizes reason, Pythagoras of Samos, the founder of the Pythagorean theorem, proposes the eternity of the spirit, and through a transmigration of it into other animated entities. Thus, all animated beings ought to be judged as belonging to one big family. He also explains that with specific cycles, the same incidents happen over and over again, for nothing is completely new, and man is a microcosm, mirroring all aspects that constitute the universe. Pythagoras was the first to utilize the word kosmos (literally “world-order” or “ordered-world”) with regard to the universe (Sangalli XIV), and he was one of the earliest philosophers to express the reason for the existence of the universe by coinciding primordial thoughts, instincts, and divinity into mathematics. According to the Pythagorean Philosophy, “[t]he word kosmos, in addition to its primary meaning of order, also means ornament. The world, according to Pythagoras, is ornamented with order. This is another way of saying that the universe is beautifully ordered” (Fideler 22).

Pi tries to complete this long journey in two ways. The first is to address the challenges of nature, which is a physical contest. Because of physical needs, such as water, food, and rest, which allow him to survive, Pi has to abandon all of his rituals and his civic mind. This is carried to such a degree that vegetarian Pi has to eat meat, become a savage man, and hunt. This is one of his most challenging moments in nature. On the other hand, while trying to be a hunter, he also strives not to be hunted by Richard Parker. As for his spiritual journey, Pi wants to complete his own mystical passage squarely in the middle of this limbo. Pi, who has a family on board a ship filled with many animals, faces a disaster which resembles Noah’s flood. The ship abandons him by sinking deep into the ocean, where his pilgrimage starts. He comprehends that the things he previously thought he possessed were, are, and will only be possessed by God: “At such moments I tried to elevate myself. I would touch the turban I had made with the remnants of my shirt and I would say aloud, “THIS IS GOD’S HAT!” I would pat my pants and say aloud, “THIS IS GOD’S ATTIRE!” I would point to Richard Parker and say aloud, “THIS IS GOD’S CAT!” I would point to the lifeboat and say aloud, “THIS IS GOD’S ARK!”” (Martel 302).

After the days Pi used to spend in the zoo, he was all alone with Parker, himself, and God in the ocean. Maybe Richard Parker never even existed. Maybe it was just Pi’s id or his primitive, brutal side. However, the central point for Patel is discovering himself in the possibilities and eternity of life by staying away from all of the commodities around him to reach the creator. Just like Aristotle’s seclusion on Lesbos island, or Yunus Emre’s search for the love of God (see Baskel), Pi realizes that God is actually everywhere. God has always been there from the very beginning; in Richard Parker, Orange Water, Zebra, flying fish, algae island, his past memories, and his salvation. Richard Parker, who does not look back at the Mexican beach, is actually a reflection of God, and therefore, instead of what Pi presumed, God never left him alone.

Conclusion

Through a comparative study of the philosophy of karma, the panentheistic approach, and the novel Life of Pi by Yann Martel, this article analyzes how life drags humans into the unknown on a journey where they face options, just as Pi’s boat drifts across the ocean. On this journey, the opening of human’s eyes, leaving behind the cave and feeling that everything is possible, is not only a physical journey, but also a spiritual crossing. Pi completes this journey by integrating himself into his surroundings with Peter Parker, denied the option of shutting his eyes to any belief or possibility, thus transcending his entity. In terms of the panentheistic approach, through the novel, this article lays out that to be a part of this universe, in which every millimeter is finely calculated and formulated, is also to be a part of this equation and God. Through a circulation of deductive and inductive voyages, nature, God, man, animals, trees, and the universe blend in such a harmonious way that distinguishing one from the other becomes nearly impossible, as long as one believes in what is really happening. In order to be able to do all of these things – that is, to understand the existence of the invisible – perhaps it is possible to understand the nature of everything by being empathetic to the nature of everything, just as one “lives” through feelings of love, hate, loyalty, and other emotions, once you exit the cave or leave the boat, it is possible to begin a transcendent journey. In this way, it is conceivable to sense things that do not already have a scientific definition. If the formula for love, hate, and God is not a requirement, why should a formula for anyone or anything else be required?

Just in the way Socrates would see the world, “If human beings do not understand the true nature of things, and principles like beauty and justice and goodness, he explained, then no one can expect them to live by those principles in their own lives. The world we live in, in other words, is a world created by our systematic ignorance – and our unwillingness to see things as they really truly are” (Herman 17). Through the comparative angle of Karma philosophy, and panentheistic philosophy, this study reveals that seeing life and death together through a single window is also the moment of maturation for Pi. The moments when he does not care to die are moments when he perceives that death and life are an ongoing cycle, and that he does not have to do anything to understand that he can be with God. Even if the integrity of the story seems extraordinary, there is nothing unusual about it. “I am who I am” (Martel 28) concludes Pi from the beginning, a reference to Exodus 3:14. No matter when or where, God is there. He is the Alpha and the Omega, as in Revelation 1:8. But does this mean that Pi should declare himself God? Not at all. If God creates man in his own image, if he is everywhere and in everything, then he is also in human’s body. Thus, when Pi says I am who I am, he refers to the power of God in his soul. God gives life to man, nature, and everything else. Searching for God means actually living with God. This is because the cosmos has been created by the grace of God in his own reflection, and in his own universe. Through the philosophies of karma and panentheism and the analysis of the novel, it may be proposed that the existence of “God” means the following: Humans belong to God, humans have descended from God, and the absolute return destination is God.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

Works Cited

Baskel, Zekeriya. Yunus Emre: The Sufi Poet in Love. Blue Dome Press, 2010.Search in Google Scholar

Biernacki, Loriliai and Philip Clayton, editors. Panentheism Across the World’s Traditions. Oxford University Press, 2013.10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199989898.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

Cohen, S. Marc, et al. Readings in Ancient Greek Philosophy from Thales to Aristotle. Hackett Publishing Company, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

Cooper, John W. Panentheism, the Other God of the Philosophers: From Plato to the Present. Grand Baker Academic, 2006.Search in Google Scholar

Fideler, David. The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library: An Anthology of Ancient Writings Which Relate to Pythagoras and Pythagorean Philosophy. Translated by K. S. Guthrie, edited by David Fideler. Phanes Press, 1987.Search in Google Scholar

Herman, Arthur. The Cave and the Light: Plato Versus Aristotle, and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization. Random House, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

Martel, Yann. Life of Pi. Mariner Books, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

Mensch, James. “The Intertwining of Incommensurables: Yann Martel’s Life of Pi.” Phenomenology and the non-human animal at the limits of experience, edited by C. Lotz and C. M. Painter, Springer, 2007, pp. 135–147.10.1007/978-1-4020-6307-7_10Search in Google Scholar

Morgan, Joseph R. “Pacific Ocean.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 28 January 2021, https://www.britannica.com/place/Pacific-OceanSearch in Google Scholar

Mumford, Lewis. The Pentagon of Powe. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970.Search in Google Scholar

NASB-Amplified Parallel Bible, compiled by Hendrickson Bibles, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

Plutarch. Moralia [Plutarch’s Moralia In Fifteen Volumes, IX]. Harvard University Press, 1961Search in Google Scholar

Sangalli, Arturo. Pythagoras Revenge: A Mathematical Mystery. Princeton University Press, 2009.10.1515/9781400829903Search in Google Scholar

Sassi, Maria Michela. The Beginnings of Philosophy in Greece. Princeton University Press, 2018.10.23943/princeton/9780691180502.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

The Quran. Translated by Talal Itani. ClearQuran, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

Zalasiewicz, Jan and Mark Williams. Ocean Worlds: The Story of Seas on Earth and Other Planets. Oxford University Press, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Timucin Bugra Edman and Hacer Gozen, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Gender Fluidity in Early-Modern to Post-Modern Children’s Literature and Culture, edited by Sophie Raynard-Leroy and Charlotte Trinquet du Lys

- Gender Fluidity: From Euphemism to Pride

- 1. The Early-Modern Legacy of Gender Bending onto the 19th Century

- Gender, Class, and Human/Non-Human Fluidity in Théodore and Hippolyte Cogniards’ féerie, The White Cat

- Naughty Girl, or Not a Girl? Behavior and Becoming in Les Malheurs de Sophie

- Ah!Nana’s Fairytale Punk-Comics: From the Comtesse de Ségur’s “Histoire de Blondine, Bonne-Biche et Beau-Minon” to Nicole Claveloux’s “Histoire de Blondasse, de Belle-Biche et Gros Chachat”

- A “Fabulous Monster” and a “Wonderful Boy:” Gender and the Elusive Victorian Child in the Alice Books and Peter Pan

- 2. Post-Modern Revisions of What Was Perhaps Too Modern Back Then

- Double Trouble: Gender Fluid Heroism in American Children’s Television

- The Queer Glow up of Hero-Sword Legacies in She-Ra, Korra, and Sailor Moon

- 3. Reflections on the Alternative Possibilities Offered by the Genre (Fairy Tales and Folklore) on issues of Gender and Sexuality

- The Transgender Imagination in Folk Narratives: The Case of ATU 514, “The Shift of Sex”

- A Tale of Two Trans Men: Transmasculine Identity and Trauma in Two Fairy-Tale Retellings

- Special Issue: Alberto Blest Gana at 100, edited by Patricia Vilches

- On Alberto Blest Gana

- Alberto Blest Gana: 100 Years Later

- New Problems of Realism in Martín Rivas

- Paris, the End of the Party in Alberto Blest Gana’s Los Trasplantados

- What About Realism? Alberto Blest Gana, Georg Lukács, and Their Chilean Readers

- Alberto Blest Gana and the Sensory Appeal of Wealth

- The Costumbrismo of Conflict in El ideal de un calavera

- Countering Acts of Dispossession through Alberto Blest Gana’s Mariluán

- Alberto Blest Gana: Four Chronicles and a Novel

- From the Newspaper Serial to the Novel (1853–1863): Mediation of the Periodical Press in the Foundation of Alberto Blest Gana’s Narrative Project

- Special Issue: Taiwanese Identity, edited by Briankle G. Chang and Jon Solomon - Part I

- The Pandemic and its Repercussions on Taiwan, its Identity, and Liberal Democracy

- From Taiwan New Cinema to Post-New Cinema: The Transition of Identity in Cape No. 7 and the Naming Issue of Post-New Cinema

- Regular Articles

- Friction in the Creative City

- The Impact of Image on Translation Decision-Making in Dubbing into Arabic – Premeditated Manipulation par Excellence: The Exodus Song as a Case Study

- God, Man, and Nature: Life for Reason and the Reason Behind the Universe – A Panentheistic Approach to Life of Pi

- The Revival of the Past: Privatizing Cultural Practices in the Festival Era

- “Riffraff” On the Waterfront: A Critical Analysis of Labor Imagery on the Imagined Docks of the Hollywood Dream Factory, 1934–1937

- “Thrice the brindled cat hath mew’d” – The Three Trials of William Hone

- Erratum

- Erratum to “‘Thrice the brindled cat hath mew’d’ – The Three Trials of William Hone”

Articles in the same Issue

- Special Issue: Gender Fluidity in Early-Modern to Post-Modern Children’s Literature and Culture, edited by Sophie Raynard-Leroy and Charlotte Trinquet du Lys

- Gender Fluidity: From Euphemism to Pride

- 1. The Early-Modern Legacy of Gender Bending onto the 19th Century

- Gender, Class, and Human/Non-Human Fluidity in Théodore and Hippolyte Cogniards’ féerie, The White Cat

- Naughty Girl, or Not a Girl? Behavior and Becoming in Les Malheurs de Sophie

- Ah!Nana’s Fairytale Punk-Comics: From the Comtesse de Ségur’s “Histoire de Blondine, Bonne-Biche et Beau-Minon” to Nicole Claveloux’s “Histoire de Blondasse, de Belle-Biche et Gros Chachat”

- A “Fabulous Monster” and a “Wonderful Boy:” Gender and the Elusive Victorian Child in the Alice Books and Peter Pan

- 2. Post-Modern Revisions of What Was Perhaps Too Modern Back Then

- Double Trouble: Gender Fluid Heroism in American Children’s Television

- The Queer Glow up of Hero-Sword Legacies in She-Ra, Korra, and Sailor Moon

- 3. Reflections on the Alternative Possibilities Offered by the Genre (Fairy Tales and Folklore) on issues of Gender and Sexuality

- The Transgender Imagination in Folk Narratives: The Case of ATU 514, “The Shift of Sex”

- A Tale of Two Trans Men: Transmasculine Identity and Trauma in Two Fairy-Tale Retellings

- Special Issue: Alberto Blest Gana at 100, edited by Patricia Vilches

- On Alberto Blest Gana

- Alberto Blest Gana: 100 Years Later

- New Problems of Realism in Martín Rivas

- Paris, the End of the Party in Alberto Blest Gana’s Los Trasplantados

- What About Realism? Alberto Blest Gana, Georg Lukács, and Their Chilean Readers

- Alberto Blest Gana and the Sensory Appeal of Wealth

- The Costumbrismo of Conflict in El ideal de un calavera

- Countering Acts of Dispossession through Alberto Blest Gana’s Mariluán

- Alberto Blest Gana: Four Chronicles and a Novel

- From the Newspaper Serial to the Novel (1853–1863): Mediation of the Periodical Press in the Foundation of Alberto Blest Gana’s Narrative Project

- Special Issue: Taiwanese Identity, edited by Briankle G. Chang and Jon Solomon - Part I

- The Pandemic and its Repercussions on Taiwan, its Identity, and Liberal Democracy

- From Taiwan New Cinema to Post-New Cinema: The Transition of Identity in Cape No. 7 and the Naming Issue of Post-New Cinema

- Regular Articles

- Friction in the Creative City

- The Impact of Image on Translation Decision-Making in Dubbing into Arabic – Premeditated Manipulation par Excellence: The Exodus Song as a Case Study

- God, Man, and Nature: Life for Reason and the Reason Behind the Universe – A Panentheistic Approach to Life of Pi

- The Revival of the Past: Privatizing Cultural Practices in the Festival Era

- “Riffraff” On the Waterfront: A Critical Analysis of Labor Imagery on the Imagined Docks of the Hollywood Dream Factory, 1934–1937

- “Thrice the brindled cat hath mew’d” – The Three Trials of William Hone

- Erratum

- Erratum to “‘Thrice the brindled cat hath mew’d’ – The Three Trials of William Hone”