Corrosion characteristics of plasma spray, arc spray, high velocity oxygen fuel, and diamond jet coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution

Abstract

30MnB5 boron alloyed steel surface is coated using different coating techniques, namely 60(Ni-15Cr-4.4Si-3.5Fe-3.2B 0.7C)-40(WC 12Co) metallic powder plasma spray, Fe-28Cr-5C-1Mn alloy wire arc spray, WC-10Co-4Cr (thick) powder high velocity oxy-fuel (HVOF), and WC-10Co-4Cr (fine) diamond jet HVOF. The microstructure of the crude steel sample consists of ferrite and pearlite matrices and iron carbide structures. The intermediate binders are well bonded to the substrate for all coated surfaces. The arc spray coated surface shows the formation of lamellae. The cross-section of HVOF and diamond jet HVOF coated surfaces indicates the formation of WC, W2C Cr, and W parent matrix carbide structures. The corrosion characteristic of the coated steel has been investigated in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), scanning electron microscope (SEM), and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDAX) techniques. The results reveal that the steel corroded in the medium despite the coatings. However, the extent of corrosion varies. HVOF coated sample demonstrated the highest corrosion resistance while arc spray coated sample exhibited the least. EDAX mapping reveals that the elements in the coatings corroded in the order of their standard electrode potential (SEP). Higher corrosion resistance of HVOF coated sample is linked to the low SEP of tungsten.

1 Introduction

Boron alloyed steels are widely used in different industrial applications such as agricultural production, automotive manufacturing, and mining. These steels provide superior properties in terms of corrosion resistance, weldability, and formability compared to other steels of equivalent hardness (Ilca et al. 2019). Improved machinability and mechanical properties after heat treatment are important characteristics of boron alloyed steels (Ghali et al. 2012). These properties make 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel more desirable, especially for agricultural production of soil cultivation equipment. Specifically, 30MnB5 steel is widely used in agricultural machinery working in sea and ocean coasts as well as in high humidity and salty soils (Gibbons and Wimpenny 2000; Singh and Kaur 2020a; Singh et al. 2020; Sudhakar et al. 2018) in continental climates.

Corrosion of metals in contact with the soil depends on various parameters related to soil properties such as electrical resistivity, pH, water content, redox potential, ionic species, salinity, microbial activities, soil texture, porosity, and other physical factors (Arriba-Rodriguez et al. 2018; Benmoussa et al. 2006; Denison and Hobbs 1934; Liu et al. 2010; Moore and Hallmark 1987; Omran and Abdel-Salam 2020; Szymański et al. 2015). However, although metals and their alloys are widely used in industrial disciplines, the destructive corrosion problem significantly limits their economic life. This type of damage can occur via chemical (dry corrosion) or electrochemical (wet corrosion) reactions in the presence of the metal. Corrosion causes catastrophic deterioration in metals and alloys. Along with the severe deterioration due to corrosion and release of toxic substances into the environment, serious economic losses also arise resulting from the repair and/or replacement of parts exposed to corrosion and loss of products (Omran and Abdel-Salam 2020).

The most commonly used method for protecting metallic structures from corrosion is the thermal spray coating technique. Although there are many thermal spraying methods, in practice, the flame, arc, plasma, and high-velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF) techniques are more frequently used (Szymański et al. 2015). Thermal spray coating is a metallurgical process in which layers are added to the substrate surface using its own or a different type of material in the form of wire, powder, or rods. The resulting new combination may have better physical, mechanical, and chemical properties or lower costs than the substrate. This technique has advanced with the development of new alloys and processes that are highly desirable in industry, both in parts manufacturing and in the maintenance sector, thereby expanding its application areas (Cinca et al. 2013). However, the main problem that reduces the performance of coatings applied via thermal spray techniques is the speed at which the deposition particles hit the substrate and the presence of porosity, cracks, unmelted particles, and oxide residues caused by the high cooling rate (Bergant et al. 2014; Güney and Mutlu 2019; Kim et al. 2015; Pombo Rodriguez et al. 2007; Xie et al. 2019). For example, porosity is an inevitable property of thermal spray coatings and significantly affects corrosion behavior (Zhang et al. 2015). Recently, however, various methods have been applied, including thermal diffusion remelting to reduce coating porosity, self-closing coating technology, an improved spraying process, and a sealing process (Bobzin et al. 2019; Guozheng et al. 2019; Kumar et al. 2019; Milanti et al. 2015), in addition to increasing the spraying speed of the particles, improving heating and melting conditions, changing the ambient atmosphere, reducing the pollution and oxidation of high-temperature spray particles, and choosing laminar coatings instead of amorphous structures (Zhang et al. 2014).

Previous studies have investigated the effect of austenitization and annealing temperatures on the corrosion properties of boron alloyed steels and a weak correlation was found between the average ferrite grain size and the corrosion rate under heat treatment conditions (Aydın and Yazıcı 2019). The corrosion behavior has been investigated and promising results reported for coatings using WC-10Co-4Cr cermet powders (Ding et al. 2018a,b, 2020; Tian et al. 2020), on different substrates via the HVOF technique, metallic powder using the plasma spray technique (Ghasemi et al. 2014), and Fe-28Cr-5C-1Mn alloy wire using the arc spray technique (Oerlicon 2020; Szymański et al. 2015). However, no comprehensive study is found in the literature on coatings applied via the thermal spray technique on the surface of 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel. This study was carried out to investigate corrosion behavior of coatings on a 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel surface using various techniques including 60(Ni-15Cr-4.4Si-3.5Fe-3.2B 0.7C)-40(WC 12Co) metallic powder plasma spray, Fe-28Cr-5C-1Mn alloy powder wire arc spray, WC-10Co-4Cr (thick) powder HVOF, and WC-10Co-4Cr (fine) powder diamond Jet HVOF. Henceforth, 60(Ni-15Cr-4.4Si-3.5Fe-3.2B 0.7C)-40(WC 12Co) metallic powder plasma spray, Fe-28Cr-5C-1Mn alloy powder wire arc spray, WC-10Co-4Cr (thick) powder HVOF, and WC-10Co-4Cr (fine) powder diamond Jet HVOF are referred to as plasma spray, arc spray, HVOF, and diamond jet, respectively. It should be mentioned that coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel, irrespective of the coating technique used, could gain application in agricultural machinery working in sea and ocean coasts as well as in high humidity and salty soil environments. This investigation could therefore help in the selection of the most suitable 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel for such application.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Substrate material

Structurally, the substrate material used was low-carbon special-alloyed boron steel (30MnB5), whose elemental composition is given in Table 1. Samples prepared in dimensions of 15 × 25 × 10 mm were degreased in acetone before coating. To ensure the mechanical bonding of the coating, the sample surfaces were roughened to an average Ra of 8–9 μm by spraying with Al2O3 sand at 9 bar pressures.

Elemental composition of 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel sample.

| C% | Mn% | P% | Si% | Al% | Ti% | B% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3–0.33 | 1.30–1.33 | 0.010–0.014 | 0.034 | 0.036 | 0.042 | 0.0008–0.005 |

2.2 Coating method and coating materials

Sample surfaces were coated at Senkron Surface Technologies (San. ve Dış Tic. Ltd., Kocaeli, Turkey). The samples were treated with four different coating materials as listed in Table 2. Although the elemental composition of the coating powder used for HVOF coating and Diamond Jet HVOF coating was the same, different particle sizes were chosen. The powder particle sizes used in HVOF coating were coarser and a conventional-type spray gun was selected. The powder particle sizes used in Diamond Jet HVOF coating were finer and the Diamond Jet spray gun was used. The parameters used in the plasma spray, arc spray, HVOF, and Diamond Jet HVOF coating techniques are listed in Table 3.

Sample properties and coating methods.

| Coating technique | Plasma spray | Ark spray | HVOF | Diamond jet HVOF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemistry of intermediate binder (undercoat) powder | Ni-22Cr-10Al-1.0Y | Ni20-Al | Not used | Not used |

| Intermediate binder powder trade name | Amdry 962 | Metco 8405 | No | No |

| Intermediate binder thickness | 50–60 micron | 50–60 micron | No | No |

| Coating powder chemistry | 60(Ni-15Cr-4.4Si-3.5Fe-3.2B 0.7C)-40(WC 12Co) | Fe-28Cr-5C-1Mn | WC-10Co-4Cr | WC-10Co-4Cr |

| Coating powder trade name | Woka 7703 | Metco 8222 | Woka 3652 | Woka 3654 |

| Coating thickness | 250–300 micron | 250–300 micron | 250–300 micron | 250–300 micron |

| Particle size | −106 + 45 µm | – | −45 + 15 µm | −30 + 10 µm |

| Diameters | 16.2 mm | – | – | |

| Manufacture | Blended | Cored wire | Agglomerated & sintered | Agglomerated & sintered |

-

HVOF, high velocity oxygen fuel.

Plasma spray coating parameters.

| Plasma spray coating | Electric arc spray coating | HVOF spray coating | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Parameter | Parameter | HVOF | DJ-HVOF | ||

| Gun type | 3MB | Gun type | LD/U2 | Gun type | JP 5000 | DJ 2600 |

| Spray distance (mm) | 120 | Spray distance (mm) | 120 | Spray distance (mm) | 350 | 250 |

| Argon flow rate (lt/min) | 80 | Spray angle | 60° | Spray angle | 90° | 90° |

| Hydrogen flow rate (lt/min) | 15 | Current (A) | 200 | Oxygen pressure (Bar) | 12 | 10 |

| Nozzle and electrode | Cu/Cu-W | Voltage (V) | 40 | Kerosene pressure (Bar) | 7.6 ± 0.3 | – |

| Nozzle diameter (mm) | 6.7 | Air pressure (bar) | 5 | Propane (Bar) | – | 6 |

| Powder feeding rate (gr/min) | 42 | Gas consumption for atomizing | 80 m3/h | Powder feeding rate (gr/min) | 60–75 | 38 |

| Carrier gas and flow rate (lt/min) | Ar, 10 | Wire diameter | 16.2 mm | Transition layer thickness (µm) | 10–12 | 10–12 |

| Cooling pressure (bar) | 3–5 | Wire feeding | Pull-push | Barrel length (mm) | 100 | 100 |

| Average temperature (°C) | 80 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Disc rotation speed (rpm) | 35 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Transition layer thickness (µm) | 15–20 | – | – | – | – | – |

-

HVOF, high velocity oxygen fuel.

2.3 Electrochemical corrosion measurements

Electrochemical experiments were performed in a Gamry instrument, Reference 600 under static and atmospheric conditions. The setup consisted of the coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel sample as the working electrode, a graphite rod as the counter or auxiliary electrode, and a Ag(s)|AgCl(s)|sat.

2.4 Surface characterization

The surface morphology of the coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel samples before and after corrosion in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution for 6 h was examined using scanning electron microscope (SEM) Quanta FEG 250 model conjoined with an energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDAX) probe (accelerator voltage 10 keV) for the acquisition of elemental composition. The elemental distribution on the steel surface before as after corrosion was also mapped using the EDAX.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Microstructural of uncoated and coated 30MnB5 samples

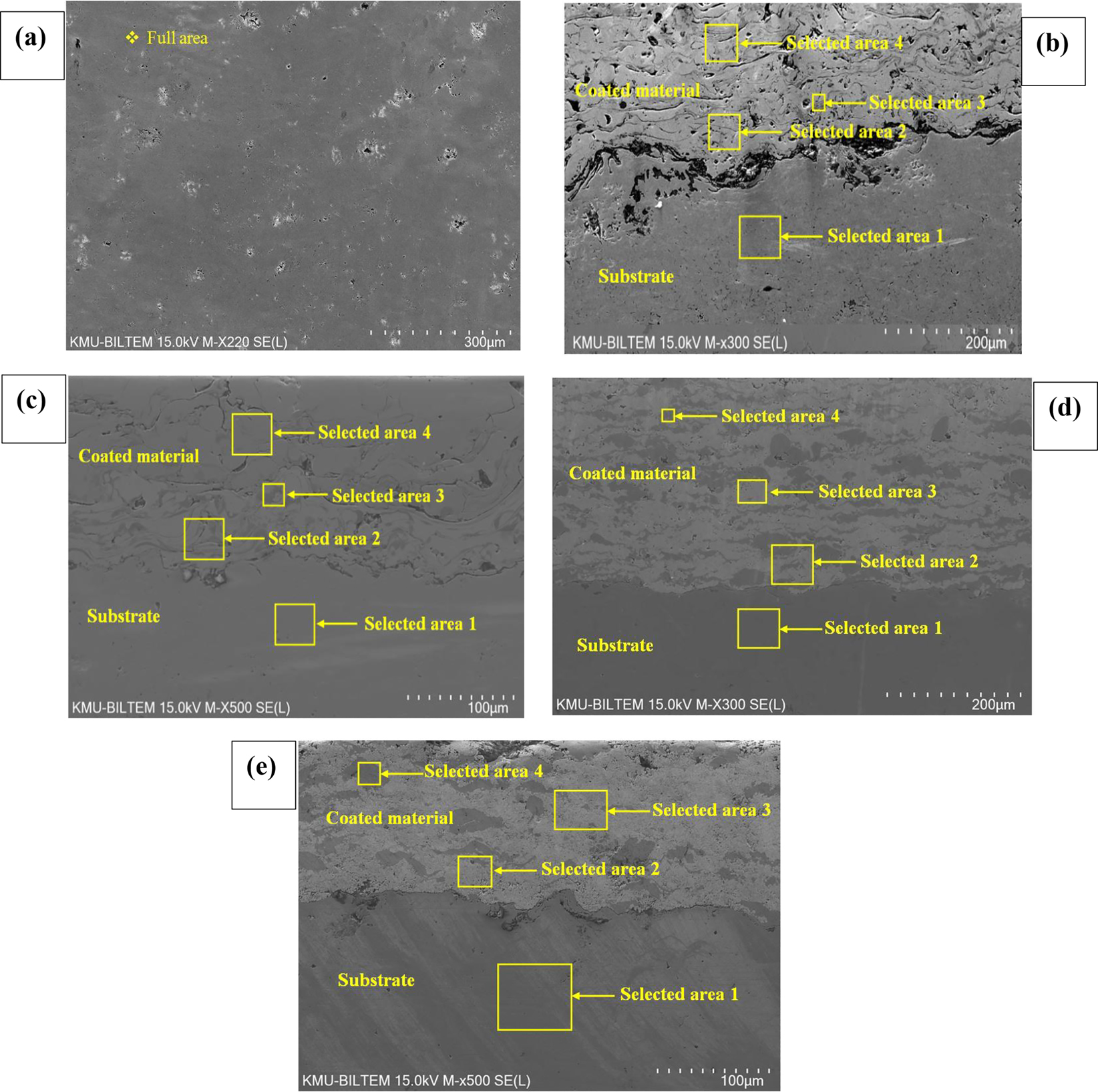

The microstructure of the crude 30MnB5 steel sample is given in Figure 1a. The structure of the crude steel consists of ferrite and pearlite matrices and iron carbide structures. Porosity and residues are also seen on the surface. In Table 4 the quantitative analysis (atomic%) of the elements Fe, C, Al, Si, P, Ti, Mn, and B for the full surface area in Figure 1a as determined by the EDAX tests is given. The analysis results show compatibility with the chemical composition of 30MnB5 substrate (Table 1).

SEM microstructural image of (a) crude 30MnB5 steel at ×220 magnification, (b) plasma spray coated 30MnB5 steel cross-section at ×300 magnification, (c) arc spray coated 30MnB5 steel cross-section at ×500 magnification, (d) HVOF coated 30MnB5 steel cross-section at ×300 magnification, and (e) DJ-HVOF coated 30MnB5 steel cross-section at ×500 magnification.

EDAX cross-sectional analysis for uncoated and coated 30MnB5 steel sample.

| Crude 30MnB5 steel | Element | Atomic% | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Fe | Al | Si | P | Ti | Mn | B | W | Co | Y | Cr | Ni | ||

| Full area | 5.73 | 89.36 | 1.06 | 1.29 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 1.61 | 0.01 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Plasma spray coated cross-section | 1 Selected area | 4.99 | 92.04 | 1.23 | 1.23 | – | – | – | 0.02 | – | – | – | 0.49 | – |

| 2 Selected area | – | 2.66 | 2.36 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.42 | 0.25 | 1.89 | 92.42 | |

| 3 Selected area | 8.78 | 1.02 | – | 0.82 | – | – | – | 0.01 | – | 0.43 | – | 1.25 | 87.69 | |

| 4 Selected area | 7.06 | 1.01 | – | 0.54 | – | – | – | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.47 | – | 3.64 | 87.01 | |

| Arc spray coated cross-section | 1 Selected area | 5.03 | 90.03 | 1.01 | 1.24 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 1.59 | 0.03 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2 Selected area | – | 3.01 | 1.08 | – | – | – | 4.19 | – | – | – | – | – | 91.72 | |

| 3 Selected area | 7.73 | 62.76 | – | – | – | – | 0.76 | – | – | – | – | 28.76 | – | |

| 4 Selected area | 8.58 | 58.71 | – | – | – | – | 0.78 | – | – | – | – | 31.93 | – | |

| HVOF coated cross-section | 1 Selected area | 5.43 | 88.75 | 1.28 | 1.43 | 0.58 | 0.63 | 1.86 | 0.03 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2 Selected area | 14.87 | 4.67 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 53.82 | 0.85 | – | 25.75 | – | |

| 3 Selected area | 36.94 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 42.29 | 13.06 | – | 7.71 | – | |

| 4 Selected area | 27.36 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 40.77 | 19.41 | – | 12.46 | – | |

| Diamon jet–HVOF coated cross–section | 1 Selected area | 5.49 | 89.41 | 1.14 | 0.74 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 1.68 | 0.02 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2 Selected area | 24.5 | 2.03 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 37.11 | 21.19 | – | 15.61 | – | |

| 3 Selected area | 27.66 | 2.26 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 37.72 | 20.03 | – | 12.23 | – | |

| 4 Selected area | 21.94 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 6.45 | 3.89 | – | 67.72 | – | |

-

HVOF, high velocity oxygen fuel.

Thermal spray coatings generally produce porous structures. The image analysis software ImageJ was used to assess whether the coatings met the required specification (Singh and Kaur 2020b). The porosity rate in the microstructure of the coatings was determined via SEM images as 2–3%. Figure 1b shows the SEM micrograph taken for the section coated using the plasma spray technique. It can be seen that the 60(Ni-15Cr-4.4Si-3.5Fe-3.2B 0.7C)-40(WC 12Co) coating applied using the NiCrAlY intermediate binder bonded well to the substrate mechanically and metallurgically. The EDAX analysis given in Table 4 shows the presence of the powder elements on the surfaces. Moreso, high percentage of Fe (90.04%) was detected in Section 1 of Figure 1b. The binder, Ni-22Cr-10Al-1Y, may have contained some Fe or small Fe debris carried into the pores of the coating during grinding/polishing. Chen and Pfender (1996) had also reported the possibility of metallurgical diffusion and alloying during the coating process. It can be observed from the micrograph that the fully melted or semi-melted particles in the coating increased the mechanical interaction. Pores also observed in the micrograph are a characteristic feature of plasma coatings and are caused by the high pressure and temperature to which the coating is subjected to and are believed to result from the breakdown of the lamellae (Yilmaz et al. 2011).

As seen in Figure 1c, the SEM examination of the 28Cr 5C1Mn-based cored wire coatings produced using optimized coatings parameters via the arc spray technique shows that the lamellae typically produced by thermal spray coatings were formed in the structure (Stoica et al. 2004). It can be seen that the coatings made using the NiAl intermediate binder bonded well both mechanically and metallurgically to the substrate. Porosities and oxide zones are seen in the coatings’ structure. In addition, microcracks and particles that solidified afterwards are present in the coatings’ structure. Depending on the chemical content of the coatings’ powder, complex carbides were found in the structure, and carbide phases were deposited in the coating structure, especially along the grain boundaries. This can be explained using the results of the EDAX analysis given in Table 4. The EDAX results reveal that in the regions with darker color contrast than the main phase, Cr is atomically higher.

Figure 1d and 1e, respectively, show the SEM micrographs of cross-sections of coarse-grained WC-10Co-4Cr coatings applied using the kerosene-fueled HVOF technique and of fine-grained WC-10Co-4Cr coatings applied using the propane gas-fired diamon jet-HVOF technique. The general appearance on the micrographs reveals that the coatings are mechanically and metallurgically bonded to the substrate. It can be observed from the micrographs that the fully melted or semi-melted particles in the coatings increased the mechanical interaction. Quantitative analyses (atomic%) of the areas 1, 2, 3 and 4 in Figure 1d and 1e are also given in Table 4. The EDAX spectrum of the area designated 1 was taken from the substrate regions of the migrorographs in Figure 4d and 4e. These results describe the typical parent material. The EDAX analyses from areas 2 and 3 near the melding border provide a composition that almost matches the standard composition of the WC-10Co-4Cr powder. The presence of the element Fe in these coatings regions, respectively, is accepted as its inclusion in the structure by diffusion (Singh and Kaur 2020b). This is an indication that metallurgical bonding has occurred and strengthened the coatings (Singh and Kaur 2020b). It reveals that the light-gray particles in the same areas primarily contain W and C, indicating the presence of the tungsten carbide phase. The dark-gray matrix in area 4 shows the presence of significant C and Co as well as small amounts of other elements such as W, Cr, O, and so on. The surface cross-section of the WC-10Co-4Cr coatings indicates that under the effect of the high temperature of the coatings’ process,WC, W2C Cr, and W parent matrix carbide structures were formed. That is, the carbide matrices are represented by the dark gray region containing the phases in the morphology of the coatings. This matrix shows a low W content, representing low temperature and low WC solubility, causing the carbides to cluster. The porous WC particle grains (Figure 1d and 1e) are well bonded due to the dark-colored CoCr matrix material. Moreover, regions with a bright contrast have carbides with rounded morphology in their microstructure. Generally, the disadvantage of HVOF spray coatings is that more decarburization occurs (Singh and Kaur 2020b).

3.2 E ocp studies

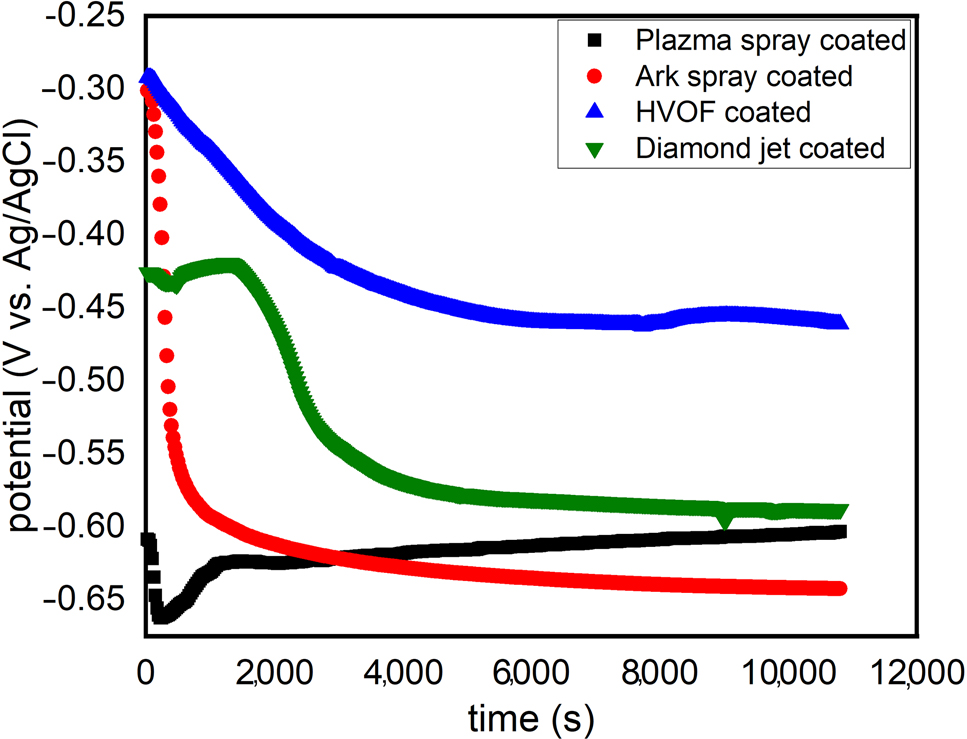

The variation of open circuit potential with time for the coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution at 25 °C is shown in Figure 2. For all samples, a steady-state Eocp was achieved at about 3000 s fulfilling one of the cardinal requirements for impedance measurement. The Eocp, as a thermodynamic property, can be used to examine the extent of metal susceptibility to corrosion in a corrosive medium (Solomon et al. 2021). The nobler the Eocp, the lesser the anodic dissolution reactions and vice versa (Aydın and Yazıcı 2019). In Figure 2, it is observed that the Eocp of all the tested samples decreased upon immersion in the corrosive medium indicating the corrosion of the coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel samples in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution. However, the susceptibility of the samples to corrosion in the corrosive solution varies. For instance, the Eocp value at 11,000 s for plasma spray, arc spray, HVOF, and diamond jet coated samples is −603.3, −642.3, −461.1, and −588.2 mV, respectively. Based on these results (Figure 2), the corrosion resistance of the samples in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution is in the order: HVOF coated ≫ diamond jet coated > plasma spray coated > arc spray coated.

Variation of open circuit potential with time for coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution at 25 °C.

3.3 EIS studies

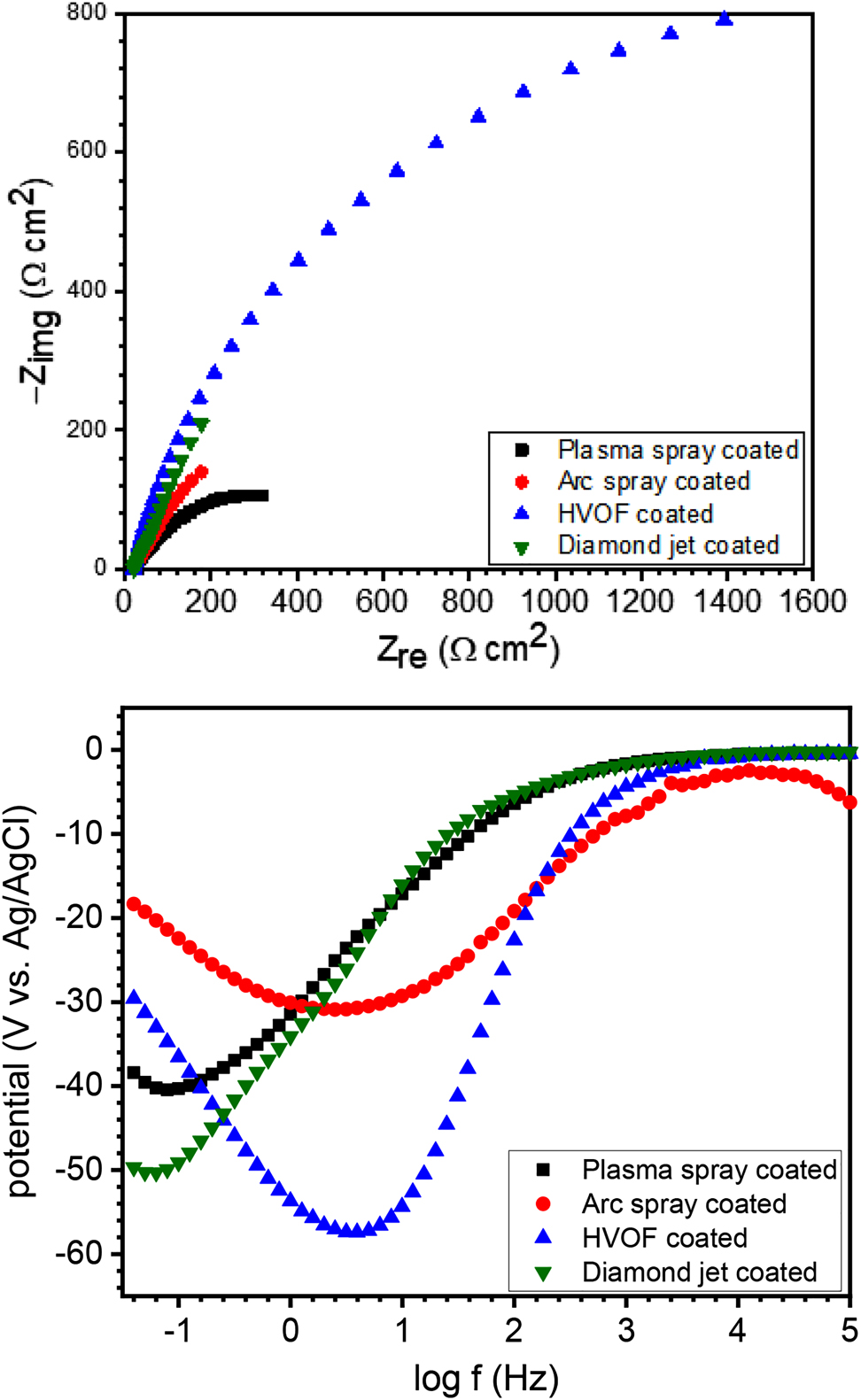

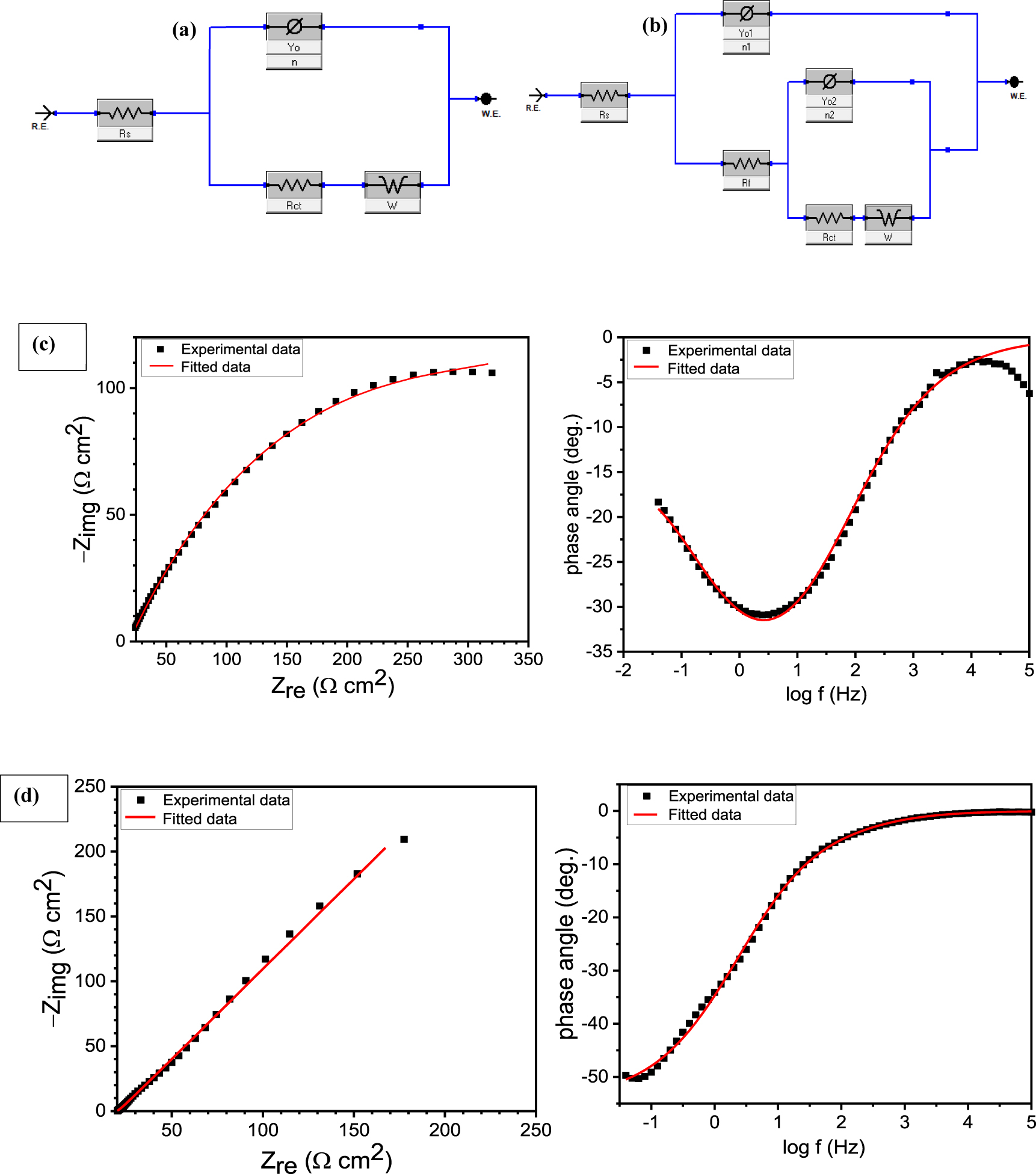

The impedance characteristics of 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel coated via plasma spray, arc spray, HVOF, and diamond jet techniques in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution at 25 °C in (a) Nyquist and (b) Bode phase formats are shown in Figure 3 In the Nyquist graphs (Figure 3a), a single and imperfect capacitive loop is observed at high frequencies for each of the studied samples. The imperfectness is a common characteristic of a solid electrode and is caused by micro roughness and other heterogeneity on the solid working electrode (Masroor et al. 2017). The singleness indicates a charge transfer phenomenon (Masroor et al. 2017). The capacitive loop, however, is seen to be an incomplete semi-circle suggesting that diffusion equally plays a part in the corrosion process. In the Bode phase representation (Figure 3b), the phase angle for the arc spray, plasma spray, diamond jet, and HVOF coated samples is 31°, 41°, 50°, and 57°, respectively, and confirms contribution from diffusion in the corrosion process. For a completely diffusion controlled corrosion system, the phase angle is expected to be 45° (Gerengi et al. 2016). These observations informed the selection of the equivalent circuits given in Figure 4a and 4b in the modeling of the corrosion of coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution. The selected equivalent circuits gave a good fit as could be seen in the representative fitted graphs in Figure 4c and 4d and the low chi-square values given in Table 5. The equivalent circuits consist of a solution resistance (Rs) that accounts for the resistance between the working electrode surface and the tip of the Luggin capillary holding the reference electrode, a constant phase element

Electrochemical impedance spectra for coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution at 25 °C in (a) Nyquist and (b) Bode phase formats.

Equivalent circuit model used in modeling the corrosion of (a) plasma spray coated, arc spray coated, HVOF coated, and (b) diamond jet coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel samples in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution at 25 °C; (c) and (d) show the representative fitted graphs.

Electrochemical impedance parameters for coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution at 25 °C.

| Sample/treatment | R s (Ω cm2) | CPEdl | R ct (Ω cm2) | CPEoxide | R oxide (Ω cm2) | R total (Ω cm2) | W (×10−3) | x 2 (×10−4) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y 01 (µ S*sˆa*cmˆ(−2)) | n1 | Y 02 (µ S*sˆa*cmˆ(−2)) | n2 | |||||||

| Plasma spray coated | 19.42 ± 0.03 | 1027.00 | 0.51 | 432.70 ± 1.30 | – | – | – | 432.70 ± 1.30 | 0.03 | 4.83 |

| Arc spray coated | 20.18 ± 0.01 | 2563.00 | 0.82 | 185.00 ± 1.10 | – | – | – | 185.00 ± 1.10 | 0.01 | 2.15 |

| HVOF coated | 19.83 ± 0.03 | 595.9 | 0.79 | 1233.00 ± 8.20 | – | – | – | 1233.00 ± 8.20 | 2.20 | 3.04 |

| Diamond jet coated | 20.09 ± 0.03 | 3364.00 | 0.63 | 434.80 ± 5.03 | 4457.00 | 0.65 | 7.44 ± 0.01 | 442.24 ± 5.04 | 1.78 | 2.20 |

Generally, the size of a capacitive loop is indicative of corrosion resistance by a sample in a corrosive environment (Masroor et al. 2017). The larger the capacitive loop, the higher the corrosion resistance property. From Figure 3, it is obvious that the HVOF coated specimen exhibited the highest corrosion resistance property with a measured total resistance (Rtotal) of 1233.00 Ω cm2 (Table 5). This is followed by the diamond jet and plasma spray coated samples having a Rtotal of 442.24 and 432.70 Ω cm2, respectively. The most susceptible to corrosion is the arc spray coated sample (Al-riched) with a Rtotal of 185.00 Ω cm2. Godlewska et al. (2020) recently reported a detrimental role of Al component in the corrosion of high-entropy alloys, AlCrFe2Ni2Mox in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution.

It had been reported that the coating technique could affect the properties of coatings. Huang et al. (2020) noted that high velocity oxygen liquid fuel (HVOLF) sprayed multimodal WC-10Co4Cr coating exhibited good fracture toughness and corrosion resistance, while high velocity oxygen gas fuel (HVOGF) sprayed coating had poor mechanical and electrochemical properties. Similarly, Ding et al. (2018a,b) found the HVOLF WC-10Co4Cr sprayed bimodal coating exhibited lesser WC decarburization, lower porosity, higher hardness, fracture toughness, and erosion resistance compared to HVOGF WC-10Co4Cr sprayed bimodal coating.

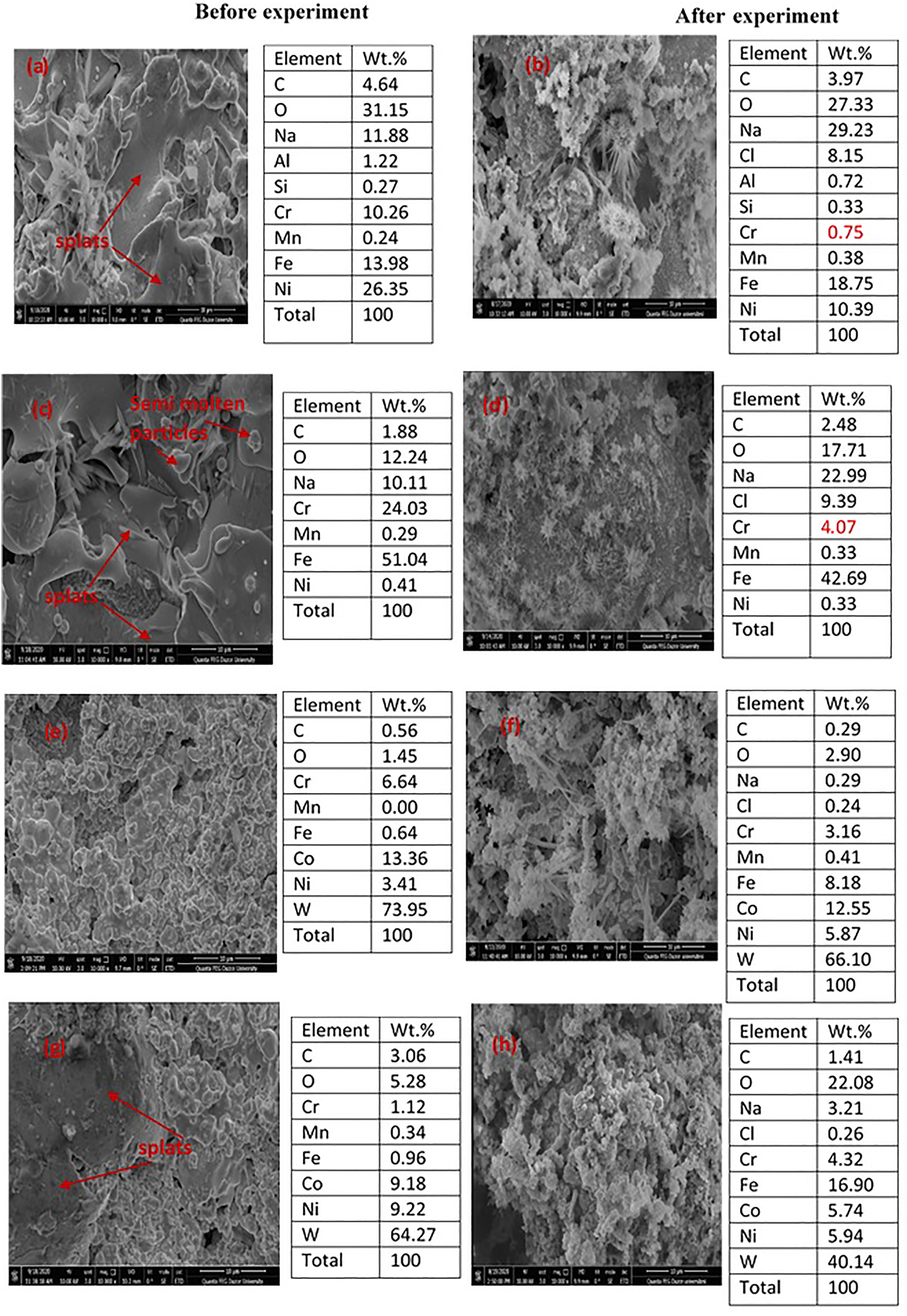

3.4 SEM and EDAX studies

Figure 5 displays the SEM images and EDAX data before and after experiments for (a, b) plasma spray coated, (c, d) arc spray coated, (e, f) HVOF coated, and (g, h) diamond jet coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel samples in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution at 25 °C. All the coated surfaces (Figure 5a, 5c, 5e and 5g) exhibit rough morphology but the HVOF technique produced the smoothest morphology (Figure 5e) followed by the diamond jet technique (Figure 5g). Splats and semi-molten powder particles are seen on the coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel surfaces particularly the plasma spray and arc spray coated surfaces. This is caused by the pinning effect of molten and semi-molten powder particles during the spraying process (Wang et al. 2020). Expectedly, the plasma spray coated surface (Figure 5a) is enriched with the binder and coated powder components (Table 2): Ni (26.35%), Cr (10.26%), and Al (1.22%). In addition, a high concentration of O (31.15%) is observed and is unarguably from elemental oxidization during the heating process. On the arc spray coated surface (Figure 5c), the content of O, Cr, and Ni detected is 12.24, 24.03, and 0.41%, respectively. On the HVOF coated surface (Figure 5e), the Ni content is 3.41%, Cr is 6.64%, W is 73.95%, and Co is 13.36%. Finally, the content of W, Ni, Co, and Cr detected on the diamond jet surface before corrosion experiments (Figure 5g) is 64.27, 9.22, 9.18, and 1.12%, respectively. Tungsten has an excellent solid solution strengthening effect and should improve the hardness and strength of the coating (Wang et al. 2020). Interestingly, less O content is detected on the HVOF (1.45%) and diamond jet (5.25%) coated surfaces and is suggestive of lesser elemental oxidation during the HVOF coating process relative to other techniques.

SEM images and EDAX data before and after experiments for (a, b) plasma spray coated, (c, d) arc spray coated, (e, f) HVOF coated, and (g, h) diamond jet coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel samples in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution at 25 °C.

On the surfaces exposed to 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution (Figure 5b, 5d, 5f and 5h), loosely held flake-like products are seen, which is in agreement with the electrochemical results (Figure 2) that the coated samples corroded in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution. The corresponding EDAX results (Figure 5b, 5d, 5f and 5h), however, provide an insight into the corrosion process. The corrosion of the plasma spray coated sample (Figure 5a and 5b) is basically along the elements: Cr, Al, and Ni phases. For instance, the Cr, Al, and Ni contents in the corroded surface (Figure 5b) decreased from 10.26, 1.22, and 26.35% to 0.75, 0.72, and 10.39%, respectively. This corresponds to 93, 41, and 61% decrease, respectively. A similar decrease in the Cr and Ni contents is observed on the corroded arc spray coated (Figure 5d), HVOF coated (Figure 5f), and diamond jet coated (Figure 5h) surfaces. Additionally, the Co and W elements also contributed to the corrosion of the HVOF and diamond jet coatings. The corroded surfaces are also enriched with chloride ions (Figure 5b, 5d, 5f and 5h).

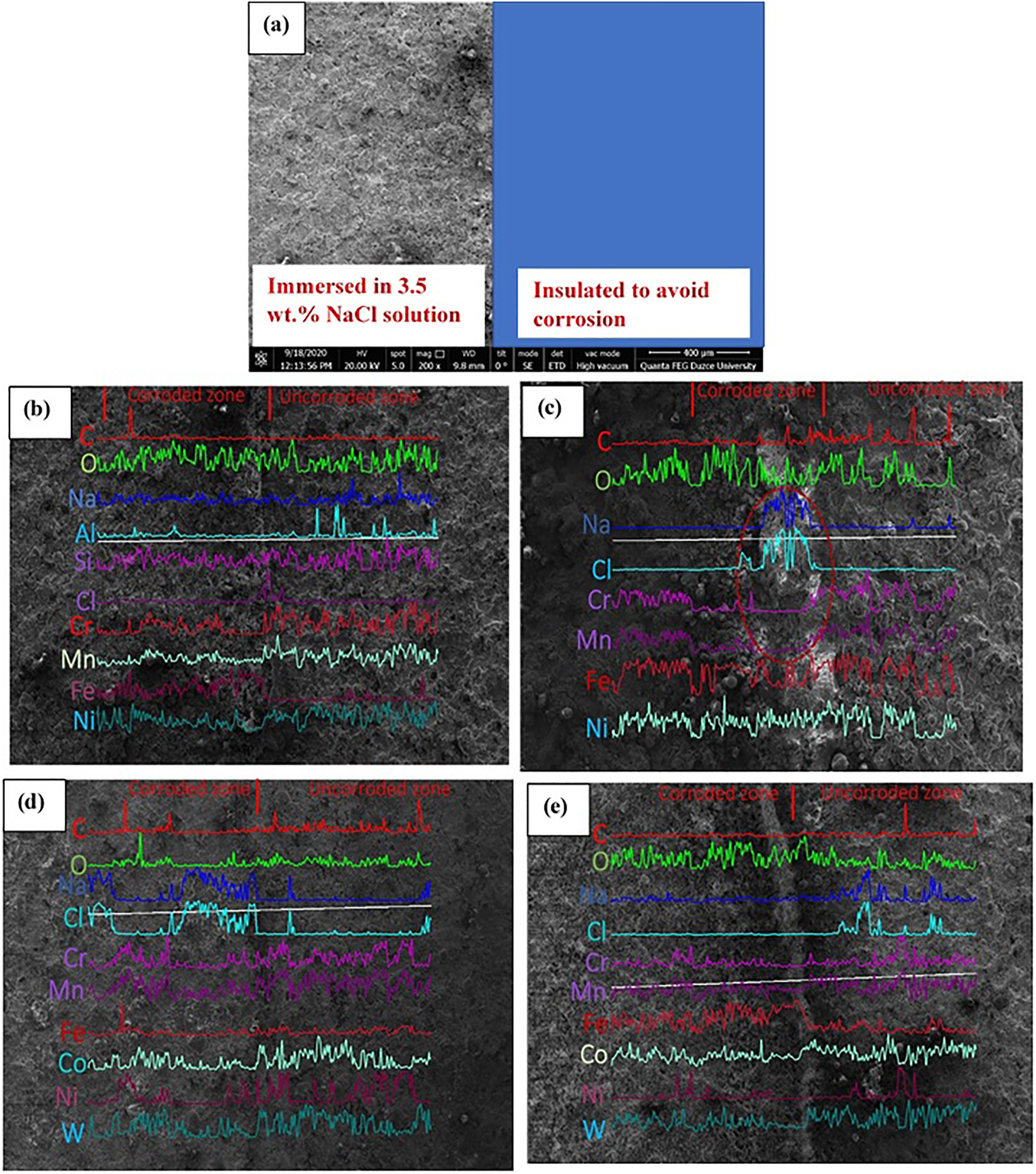

3.5 Explanation of the corrosion mechanism of the coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel

To gain insight into the corrosion of 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel coated via plasma spray, arc spray, HVOF, and diamond jet techniques in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution at normal atmospheric conditions, EDAX mapping was performed on the coated surfaces. Sample surface was segmented into two sections: one completely insulated from the corrosive solution and the other exposed to corrosive medium for 6 h (see Figure 6a). After the corrosion of the exposed area, the entire surface (exposed and unexposed) was mapped for elemental composition. The EDAX mapping results are given in Figure 6b–e. In the uncorroded portion of the surfaces (Figure 6), high content of Al, Cr, Mn, Ni, Co, and W is noted, which is expected as these elements constitute the undercoat binder or coating powder applied on the steel surface (Table 2). Additionally, O is found on the surfaces and is unarguably due to the elemental oxidation during heating (Huang et al. 2020). The Fe content is however found to be lesser relative to the aforementioned elements, which is due to the covering of the steel surface by the coating. In the exposed section, Cl content from the corrosive solution is observed in addition to the aforementioned elements. Interestingly, the Al, Cr, Mn, Ni, Co, and W content is seen to decrease substantially on the exposed portion and follow the order: Al > Mn > Cr > Co > Ni > W. The O content seems to increase on the corroded portion and could be due to the formation of more metal oxide film. The observed pattern of decrease in elemental content can be reasonably explained by considering the standard electrode potential of the detected elements (Table 6). As it is known, the higher the standard electrode potential of an element, the higher the tendency to corrode (Wang et al. 2020). It could be seen in Table 6 that the standard electrode potential of the elements mostly affected by the corrosion process is in the order: Al > Mn > Cr > Co > Ni > W. In the corrosive medium (3.5 wt.% NaCl), Cl− is enriched on the coating pores (see Figure 6) and consequently created an unbalance oxygen concentration between the inside and outside coatings. This resulted in the formation of oxygen concentration cells (Huang et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020). The elements acting as the anode gives up electrons and corrode in order of their standard electrode potential to form the cations (mostly Al3+, Mn2+, Cr3+, Ni2+, Co3+ and W6+). The electrons released from the anodic oxidation react with oxygen within the solution to form hydroxyl ions (OH−). Meanwhile, Figure 3 clearly shows that mass transfer processes played a role in the corrosion process. These processes encourage the rapid combination of the cations with the OH− to form insoluble hydroxides as the corrosion products, which is evidenced in Figure 3b, 3d, 3f and 3h (the flake-like and loosely adhered products). The corrosion products could hinder further corrosion reactions (Huang et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020) but Huang et al. (2020) noted that, the corrosion products are rapidly stripped off the coating surface by slurry erosion such that the elements continue to corrode. The fact that HVOF and diamond jet coated samples are devoid of undercoat binders, have no or lower amount of Al and Cr, and W has the least standard electrode potential in comparison to other constituent elements may be the reason for the high corrosion resistance of the HVOF and diamond jet coated samples relative to the plasma spray and arc spray coated samples.

(a) Sample preparation illustration; EDAX elemental mapping of (b) plasma spray coated, (c) Arc spray coated, (d) HVOF coated, and (e) diamond jet coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel samples after immersion in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution at 25 °C.

The standard electrode potential of main elements in the coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel.

| Equation | −E0 (V) |

|---|---|

| Ni → Ni+ + e− | 0.26 |

| Cr → Cr3+ + 3e− | 0.74 |

| W → W6+ + 6e− | 0.09 |

| Al → Al3+ + 3e− | 1.66 |

| Mn → Mn2+ + 2e− | 1.18 |

| Fe → Fe3+ + 3e− | 0.04 |

| Co → Co2+ + 2e− | 0.28 |

4 Conclusions

A boron alloyed steel, widely used in areas such as agricultural production, automotive manufacturing, and mining, was coated using four different coating techniques: 60(Ni-15Cr-4.4Si-3.5Fe-3.2B 0.7C)-40(WC 12Co) metallic powder plasma spray, Fe-28Cr-5C-1Mn alloy powder wire arc spray, WC-10Co-4Cr (thick) powder high velocity oxy-fuel (HVOF), and WC-10Co-4Cr (fine) powder diamond jet HVOF. The microstructure of the uncoated and coated alloyed steel has been studied. The corrosion behavior of the coated boron alloyed steel in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution has equally been studied using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, scanning electron microscope, and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy techniques. Based on the results, the following conclusions are drawn.

The microstructure of the crude 30MnB5 steel consists of ferrite and pearlite matrices and iron carbide structures.

Plasma spray coating ensures proper bonding of NiCrAlY intermediate to 30MnB5 steel surface.

NiAl intermediate is well bonded to 30MnB5 steel surface after arc spray coating and lamellae are formed on the coated surface.

HVOF and diamond jet HVOF techniques induced the formation of WC, W2C Cr, and W parent matrix carbide structures on coated surfaces.

The corrosion of boron alloyed steel in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution proceeded despite the coatings.

The order of corrosion resistance of the coated boron alloyed steel is: HVOF coated ≫ diamond jet coated > plasma spray coated > arc spray coated.

The observed best corrosion resistance property of HVOF is attributed to the low standard electrode potential of tungsten relative to the other elements in addition to the lesser amount of Cr, i.e., 22Cr in plasma spray, 28Cr in arc spray, and 4Cr in HVOF and diamond jet coatings.

Funding source: Duzce University Research Fund

Award Identifier / Grant number: 2019.06.05.941

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission.

-

Research funding: This work was funded by the Duzce University Research Fund, Project no. 2019.06.05.941.

-

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

Arriba-Rodriguez, L., Villanueva-Balsera, J., Ortega-Fernandez, F., and Rodriguez-Perez, F. (2018). Methods to evaluate corrosion in buried steel structures: a review. Metals (Basel) 8: 334, https://doi.org/10.3390/met8050334.Search in Google Scholar

Aydın, G. and Yazıcı, A. (2019). Effect of quenching and tempering temperature on corrosion behavior of boron steels in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 14: 2126–2135.10.20964/2019.03.22Search in Google Scholar

Benmoussa, A., Hadjel, M., and Traisnel, M. (2006). Corrosion behavior of API 5L X-60 pipeline steel exposed to near-neutral pH soil simulating solution. Mater. Corros. 57: 771–777, https://doi.org/10.1002/maco.200503964.Search in Google Scholar

Bergant, Z., Trdan, U., and Grum, J. (2014). Effect of high-temperature furnace treatment on the microstructure and corrosion behavior of NiCrBSi flame-sprayed coatings. Corrosion Sci. 88: 372–386, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2014.07.057.Search in Google Scholar

Bobzin, K., Öte, M., Knoch, M.A., and Sommer, J. (2019). Influence of powder size on the corrosion and wear behavior of HVAF-sprayed Fe-based coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 28: 63–75, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11666-018-0819-7.Search in Google Scholar

Chen, H.C. and Pfender, E. (1996). Microstructure of plasma-sprayed Ni-Al alloy coating on mild steel. Thin Solid Films 280: 188–198, https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-6090(95)08195-x.Search in Google Scholar

Cinca, N., Lima, C.R.C., and Guilemany, J.M. (2013). An overview of intermetallics research and application: status of thermal spray coatings. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2: 75–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2013.03.013.Search in Google Scholar

Denison, I.A. and Hobbs, R.B. (1934). Corrosion of ferrous metals in acid soils. J. Res. Natl. Bur. Stand. 13: 125, https://doi.org/10.6028/jres.013.008.Search in Google Scholar

Ding, X., Cheng, X.D., Shi, J., Li, C., Yuan, C.Q., and Ding, Z.X. (2018a). Influence of WC size and HVOF process on erosion wear performance of WC-10Co4Cr coatings. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 96: 1615–1624, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-017-0795-y.Search in Google Scholar

Ding, X., Cheng, X.D., Yu, X., Li, C., Yuan, C.Q., and Ding, Z.X. (2018b). Structure and cavitation erosion behavior of HVOF sprayed multi-dimensional WC–10Co4Cr coating. Trans. Nonferrous Metals Soc. China (English Ed.) 28: 487–494, https://doi.org/10.1016/s1003-6326(18)64681-3.Search in Google Scholar

Ding, X., Huang, Y., Yuan, C., and Ding, Z. (2020). Deposition and cavitation erosion behavior of multimodal WC-10Co4Cr coatings sprayed by HVOF. Surf. Coating. Technol. 392: 125757, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2020.125757.Search in Google Scholar

Gerengi, H., Mielniczek, M., Gece, G., and Solomon, M. M. (2016). Experimental and quantum chemical evaluation of 8-hydroxyquinoline as a corrosion inhibitor for copper in 0.1 M HCl. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 55: 9614–9624.10.4236/jmmce.2012.1110101Search in Google Scholar

Ghali, S.N., El-Faramawy, H.S., Eissa, M.M., Ghali, S.N., El-Faramawy, H.S., and Eissa, M.M. (2012). Influence of boron additions on mechanical properties of carbon steel. J. Miner. Mater. Char. Eng. 11: 995–999, https://doi.org/10.4236/jmmce.2012.1110101.Search in Google Scholar

Ghasemi, R., Shoja-Razavi, R., Mozafarinia, R., Jamali, H., Hajizadeh-Oghaz, M., and Ahmadi-Pidani, R. (2014). The influence of laser treatment on hot corrosion behavior of plasma-sprayed nanostructured yttria stabilized zirconia thermal barrier coatings. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 34: 2013–2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2014.01.031.Search in Google Scholar

Gibbons, G. and Wimpenny, D. (2000). Mechanical and thermomechanical properties of metal spray Invar for composite forming tooling. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 9: 630–637, https://doi.org/10.1361/105994900770345485.Search in Google Scholar

Godlewska, E.M., Mitoraj-Królikowska, M., Czerski, J., Jawańska, M., Gein, S., and Hecht, U. (2020). Corrosion of Al(Co)CrFeNi high-entropy alloys. Front. Mater. 7: 335, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2020.566336.Search in Google Scholar

Güney, B. and Mutlu, İ. (2019). Wear and corrosion resistance of Cr2O3 %-40%TiO2 coating on gray cast-iron by plasma spray technique. Mater. Res. Express 6: 096577.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2018.11.049Search in Google Scholar

Guozheng, M., Shuying, C., Pengfei, H., Haidou, W., Yangyang, Z., Qing, Z., and Guolu, L. (2019). Particle in-flight status and its influence on the properties of supersonic plasma-sprayed Fe-based amorphous metallic coatings. Surf. Coating. Technol. 358: 394–403, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2018.11.049.Search in Google Scholar

Huang, Y., Ding, X., Yuan, C.Q., Yu, Z.K., and Ding, Z.X. (2020). Slurry erosion behaviour and mechanism of HVOF sprayed micro-nano structured WC-CoCr coatings in NaCl medium. Tribol. Int. 148: 106315, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.triboint.2020.106315.Search in Google Scholar

Ilca, I., Kiss, I., and Miloștean, D. (2019). Study on the quality of boron micro–alloyed steels destined to applications in the automotive sector. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 477: 012003, https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899x/477/1/012003.Search in Google Scholar

Kim, Y.J., Jang, J.W., Lee, D.W., and Yi, S. (2015). Porosity effects of a Fe-based amorphous/nanocrystals coating prepared by a commercial high velocity oxy-fuel process on cavitation erosion behaviors. Met. Mater. Int. 21: 673–677, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12540-015-4580-x.Search in Google Scholar

Kumar, A., Kumar, R., Bijalwan, P., Dutta, M., Banerjee, A., and Laha, T. (2019). Fe-based amorphous/nanocrystalline composite coating by plasma spraying: effect of heat input on morphology, phase evolution and mechanical properties. J. Alloys Compd. 771: 827–837, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.09.024.Search in Google Scholar

Liu, T.M., Wu, Y.H., Luo, S.X., and Sun, C. (2010). Effect of soil compositions on the electrochemical corrosion behavior of carbon steel in simulated soil solution. Einfluss der Erdbodenzusammensetzung auf das elektrochemische Verhalten von Kohlenstoffstählen in simulierten Erdbodenlösungen. Mater. Werkst. 41: 228–233, https://doi.org/10.1002/mawe.201000578.Search in Google Scholar

Masroor, S., Mobin, M., Alam, M.J., and Ahmad, S. (2017). The novel iminium surfactant p-benzylidene benzyldodecyl iminium chloride as a corrosion inhibitor for plain carbon steel in 1 M HCl: electrochemical and DFT evaluation. RSC Adv. 7: 23182–23196, https://doi.org/10.1039/c6ra28426d.Search in Google Scholar

Milanti, A., Matikainen, V., Koivuluoto, H., Bolelli, G., Lusvarghi, L., and Vuoristo, P. (2015). Effect of spraying parameters on the microstructural and corrosion properties of HVAF-sprayed Fe-Cr-Ni-B-C coatings. Surf. Coating. Technol. 277: 81–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2015.07.018.Search in Google Scholar

Moore, T.J. and Hallmark, C.T. (1987). Soil properties influencing corrosion of steel in Texas soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 51: 1250–1256, https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1987.03615995005100050029x.Search in Google Scholar

Oerlicon (2020). Thermal spraying processes, Available at: https://www.oerlikon.com/metco/en/products-services/thermal-spray-equipment/thermal-spray/processes/ (Accessed 09 April 2021).10.1007/978-3-030-49532-9_1Search in Google Scholar

Omran, B.A. and Abdel-Salam, M.O. (2020). Basic corrosion fundamentals, aspects and currently applied strategies for corrosion mitigation. In: A new era for microbial corrosion mitigation using nanotechnology. Springer International Publishnig, Switzerland, pp. 1–45.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2007.05.067Search in Google Scholar

PomboRodriguez, M.H., Paredes, R.S.C., Wido, S.H., and Calixto, A. (2007). Comparison of aluminum coatings deposited by flame spray and by electric arc spray. Surf. Coating. Technol. 202: 172–179, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2007.05.067.Search in Google Scholar

Singh, G. and Kaur, M. (2020a). Sliding wear behavior of plasma sprayed 65% (NiCrSiFeBC)–35% (WC–Co) coating at elevated temperatures. Proc. IME J. J. Eng. Tribol. 234: 1396–1415.10.1080/02670844.2019.1639932Search in Google Scholar

Singh, G. and Kaur, M. (2020b). High-temperature wear behaviour of HVOF sprayed 65% (NiCrSiFeBC)−35% (WC–Co) coating. Surf. Eng. 36: 1139–1155.10.1016/j.jmapro.2020.03.040Search in Google Scholar

Singh, J., Chatha, S.S., and Sidhu, B.S. (2020). Abrasive wear behavior of newly developed weld overlaid tillage tools in laboratory and in actual field conditions. J. Manuf. Process. 55: 143–152, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2020.03.040.Search in Google Scholar

Solomon, M.M., Onyeachu, I.B., Njoku, D.I., Nwanonenyi, S.C., and Oguzie, E.E. (2021). Adsorption and corrosion inhibition characteristics of 2–(chloromethyl)benzimidazole for C1018 carbon steel in a typical sweet corrosion environment: effect of chloride ion concentration and temperature. Colloid. Surface. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 610: 125638, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125638.Search in Google Scholar

Stoica, V., Ahmed, R., Itsukaichi, T., and Tobe, S. (2004). Sliding wear evaluation of hot isostatically pressed (HIPed) thermal spray cermet coatings. Wear 257: 1103–1124, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wear.2004.07.016.Search in Google Scholar

Sudhakar, N., Jagadeesh, N., Ravikumar, N., and Ramana, V.S.N.V. (2018). Hot workability and corrosion behavior of EN31 grade steel. Mater. Today: Proc. 5: 6855–6861, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2017.11.346.Search in Google Scholar

Szymański, K., Hernas, A., Moskal, G., and Myalska, H. (2015). Thermally sprayed coatings resistant to erosion and corrosion for power plant boilers – a review. Surf. Coating. Technol. 268: 153–164.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2020.126012Search in Google Scholar

Tian, Y., Zhang, H., Chen, X., McDonald, A., Wu, S., Xiao, T., and Li, H. (2020). Effect of cavitation on corrosion behavior of HVOF-sprayed WC-10Co4Cr coating with post-sealing in artificial seawater. Surf. Coating. Technol. 397: 126012, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2020.126012.Search in Google Scholar

Wang, Y., Hao, E., An, Y., Hou, G., Zhao, X., and Zhou, H. (2020). The interaction mechanism of cavitation erosion and corrosion on HVOF sprayed NiCrWMoCuCBFe coating in artificial seawater. Appl. Surf. Sci. 525: 146499, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.146499.Search in Google Scholar

Xie, L., Xiong, X., Zeng, Y., and Wang, Y. (2019). The wear properties and mechanism of detonation sprayed iron-based amorphous coating. Surf. Coating. Technol. 366: 146–155, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2019.03.028.Search in Google Scholar

Yilmaz, S.O., Özenbas, M., and Yaz, M. (2011). FeCrC, FeW, and NiAl modified iron-based alloy coating deposited by plasma transferred arc process. Mater. Manuf. Process. 26: 722–731, https://doi.org/10.1080/10426914.2010.480997.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, C., Zhou, H., and Liu, L. (2014). Laminar Fe-based amorphous composite coatings with enhanced bonding strength and impact resistance. Acta Mater. 72: 239–251, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2014.03.047.Search in Google Scholar

Zhang, S.D., Zhang, W.L., Wang, S.G., Gu, X.J., and Wang, J.Q. (2015). Characterisation of three-dimensional porosity in an Fe-based amorphous coating and its correlation with corrosion behaviour. Corrosion Sci. 93: 211–221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2015.01.022.Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- A review on the corrosion resistance of electroless Ni-P based composite coatings and electrochemical corrosion testing methods

- Original Articles

- Water-droplet erosion behavior of high-velocity oxygen-fuel-sprayed coatings for steam turbine blades

- Corrosion characteristics of plasma spray, arc spray, high velocity oxygen fuel, and diamond jet coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution

- Corrosive-wear behavior of LSP/MAO treated magnesium alloys in physiological environment with three pH values

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on microstructure and corrosion resistance of PEO ceramic coating of magnesium alloy

- Investigating the efficacy of Curcuma longa against Desulfovibrio desulfuricans influenced corrosion in low-carbon steel

- Annual Reviewer Acknowledgement

- Reviewer acknowledgement Corrosion Reviews volume 39 (2021)

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review

- A review on the corrosion resistance of electroless Ni-P based composite coatings and electrochemical corrosion testing methods

- Original Articles

- Water-droplet erosion behavior of high-velocity oxygen-fuel-sprayed coatings for steam turbine blades

- Corrosion characteristics of plasma spray, arc spray, high velocity oxygen fuel, and diamond jet coated 30MnB5 boron alloyed steel in 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution

- Corrosive-wear behavior of LSP/MAO treated magnesium alloys in physiological environment with three pH values

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on microstructure and corrosion resistance of PEO ceramic coating of magnesium alloy

- Investigating the efficacy of Curcuma longa against Desulfovibrio desulfuricans influenced corrosion in low-carbon steel

- Annual Reviewer Acknowledgement

- Reviewer acknowledgement Corrosion Reviews volume 39 (2021)