Abstract

This introduction to the special edition presents a literature review of scholarship on Justin, demonstrating via his traditional monikers (“Justin Martyr,” “Justin of Neapolis,” “Justin the Philosopher,” and “Justin the Apologist”) the need for a fresh treatment, here dubbed “Justin of Rome”—which properly embeds Justin in his imperial setting, encompassing both the literary and historical landscape of the 2d century AD. It teases out connections between the papers that follow and offers a synthesis of the contribution of the special edition, read as a whole, to our understanding not just of this one thinker but of early Christian literature and history more broadly.

1 Introduction

Justin has achieved fame as one of the most important authors of early Christianity.[1] As with most figures in antiquity, we know little of his life. He was born as the 1st century turned into the 2d, in Flavia Neapolis in Judaea, of Samaritan stock, to a father and grandfather both bearing Graeco-Roman names. He himself was well-educated, wrote in Greek, may well have been a Roman citizen,[2] and became an immigrant to Rome, a convert to Christianity, and a teacher of the latter in the former.[3] More than that we cannot say for certain.[4] His extant written works certainly encompass the First Apology, Second Apology and Dialogue with Trypho; a heresiological work called the Syntagma has not survived, and some scholars consider the treatise On the Resurrection to be Justin’s.[5] But even his definitive works have been enough to make Justin a pillar of early Christian studies—the first apologist whose work survives at any length and in its original language, a seminal figure in delineating the evolving relationship between Christianity and Judaism, inaugurator of the idea of the logos spermatikos, and, perhaps, inventor of the idea of heresy.[6]

Justin has gone by numerous epithets—most prominently “Martyr,” “Neapolis,” “philosopher,” and “apologist.” Each, entirely legitimately, privileges different facets of his identity; at the same time each has the potential to set a scholarly agenda. In this introductory essay, we sketch the history of scholarship on Justin via these labels.[7] Though schematic, this has the advantage of demonstrating both the thematic interests of his commentators and how some aspects of his identity—and thus some areas of his œuvre—have dominated over others. In particular, our contention is that the idea of Justin as a kind of public representative of Christianity has dominated scholarly discourse, to the detriment of our understanding. In this Justin is no different from most other Christian authors. But Christianity, or any religious affiliation, was (and is) only one—and not necessarily the most important—fluctuating aspect of individuals’ changing identities.[8] Here—and it is to this that the moniker “Justin of Rome” is intended to gesture—we seek to privilege not his Christianity but his existence as an eastern subject of the Roman empire. That broader grouping, we believe, opens up new approaches and comparisons, particularly for understanding his Apologies. Moreover, it also reveals Justin not just as an important witness of early Christianity, but of the 2d century AD Roman empire more broadly.

2 Justin Martyr

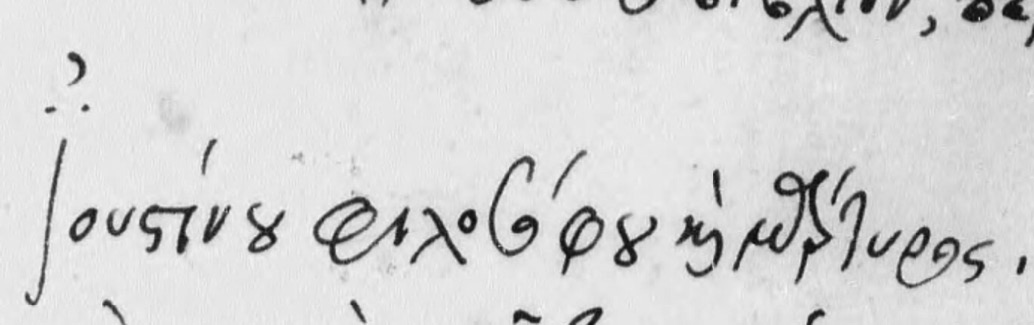

Justin is most often called “Justin Martyr,” the only Christian martyr for whom that status became part of his name. Justin does not, of course, give himself this title, although he does say that he anticipates such a death: “I expect that I will be plotted against and impaled on a stake by one of those mentioned, or at least by Crescens.”[9] His pupil Tatian commented that the cynic philosopher Crescens “set about involving Justin . . . in the death penalty.”[10] The Acts of Justin and Companions, the martyr narrative which recounts Justin’s execution, and survives in three recensions, claims to report Justin’s trial before Quintus Iunius Rusticus, urban prefect of Rome in the 160s A.D. Writing several decades later, Tertullian of Carthage, influenced both by Justin’s apologetic output, and his heresiological work, calls Justin philosophus et martyr, the label that persists in the manuscript tradition (Fig. 1).[11] Writing in the early 4th century, Eusebius cemented this tradition by both referring to Justin as “the martyr” in the fourth book of his Ecclesiastical History,[12] and suggesting that Crescens was behind Justin’s eventual death, though that was nowhere directly stated in the earlier layers of the tradition.[13]

Parisinus Graecus 450, fol. 4 (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10722125b/f4.item, last accessed 05 February 2024).

This name has not been a neutral moniker. Rather, we suggest, it has coloured how Justin’s writings have been read. Exemplary is Eric Osborn’s intellectual biography of Justin, arguably still the most oft-cited introduction to him.[14] Osborn’s book covers many of the themes we will consider below—his use of Scripture, his treatment of the Jews, and his relationship with contemporary philosophy. But the monograph as a whole is built on the principle that Justin was motivated in writing by opposition, whether that be from the state, philosophers, Jews, or heretics. The influence of this approach is demonstrated by its longevity. It still underlies, for example, Mary Sheather’s recent article reading Justin as concerned with the “challenge” of being a 2d-century Christian. Sheather considers Justin’s varying attitude to Rome, from conciliatory comments, to those which “suggest fundamental differences which would, in the case of Justin’s work, make his acquisition of the title of martyr entirely comprehensible.”[15]

This sense that Justin was writing as an opponent of the world, ever-destined for a fatal showdown with Roman authority, is naturally bound up with his presentation as an “apologist” (see section 5 below). On this reading, the principal aim of apology—and therefore Justin’s prime goal—was to stave off the persecution of Christians.[16] Such approaches are usually accompanied by credulous descriptions of the state of Christian persecution in the 2d century A.D., or use Justin’s writing to construct such concrete historical pictures of it.[17] But this simplistically reproduces early Christian claims about their place in the world, reinforcing an unhelpful binary model of exclusive politico-religious systems and thus characterisations of universal victimisation and persecution. Such readings of Justin “the martyr” are predicated on his Christianity being as important to others as it was to him—or perhaps better, to others and to him as it has been to modern commentators—and thus privilege this aspect of his identity as the determining factor in his relationship with the wider world, including and especially the Roman state.[18]

A further problem is raised by the question of Justin’s audience. Many of the works glossed above envisage that Justin’s Apologies were intended to be, and even were, read by the emperor and his officials.[19] Even when that is doubted, many scholars have hypothesised that such Christian apologies hoped to engage educated Graeco-Romans,[20] or provided fodder for real-life debates with them.[21] Such an external audience also lies behind many portraits of Justin as an itinerant philosopher or religious expert, enmeshed in the performative culture of the second sophistic (considered below in section 4). A more sceptical tradition, however, has suggested that the apologies—Justin’s included—are “literary fictions,” presented as if directed externally but in fact intended for internal consumption.[22] If this is correct, it further problematises the picture of apologetic as a “bridge” between distinct cultures.[23]

More important though, we suggest, is that such approaches prejudge the issue. If Justin is seen as martyr first and foremost, the question of his degree of antagonism to wider society naturally comes to permeate analysis. This mindset also lies behind much recent post-colonial work on early Christianity under Rome, which leans heavily on Justin as the first author to systematically and directly address persecution. Justin here becomes representative of a downtrodden minority (a claim taken from his opening gambit),[24] speaking truth to power to unmask and even undo imperial rule.[25] In their insistence that early Christian authors be read in their imperial context and alongside the political realia of 2d century Rome, such studies anticipate the approach we advocate here. But they also—almost by necessity—echo and amplify those models of binary opposition, and at times the traditional historical narrative of persecution, that we consider outdated and ultimately a hindrance to fully understanding Justin’s writings.

The focus on Justin as martyr is thus both misleading and teleological. Misleading, because it obscures the degree to which Justin (and others like him) manufactured a rhetorical distance from their wider society which did not characterise their everyday existence. Teleological, because it uses Justin’s death as a key to understand his earlier life, despite the fact that neither his execution nor its catalysts were inevitable. More recent explications of the likely mechanics of persecution, of the social world intellectual men like Justin inhabited, and—crucially—of the common rhetorical strategies which groups (not only Christians) used to simultaneously assimilate themselves to and distance themselves from the Roman status quo, opens the door to a richer, thicker description of Justin and his engagement with the non-Christian world.

3 Justin of Neapolis

When Justin introduces himself at the start of his First Apology, he does so by reference to his city of birth: “I, Justin, the son of Priscus and grandson of Bacchius, natives of Flavia Neapolis in Syria Palaestina.”[26] That toponymic continues to be used to identify him, particularly in French scholarship (as “Justin de Naplouse”). For our purposes, it serves to indicate the extent to which scholarship on Justin has considered his relationship to the dominant religion of that region, Judaism. This focus is unsurprising. Justin’s Dialogue with Trypho purports to relay a conversation between Justin and one Trypho, “a Hebrew of the circumcision, and having escaped from the war lately carried on there.”[27] And much of that long text considers—at least ostensibly—the relationship between Christianity and Judaism. Justin’s knowledge of and engagement with Judaism has thus long been a key concern for scholars.

Two intellectual threads can be traced here. One has focused on Justin’s use of Jewish literature. This was in part built on deliberating whether Justin’s theology was more indebted to Philo or to the Palestinian rabbis,[28] a debate bound up with Justin’s use of the Hebrew Bible and the evolving New Testament. In particular, this has concerned Justin’s place in wider contemporary debates over such usage, in particular Marcion’s rejection of much of the Mosaic Law.[29] Oskar Skarsaune has perhaps been most significant here, demonstrating Justin’s systematic use of both earlier Christian testimonia and the Septuagint, as well as his rhetorical switching between them.[30] Skarsaune stressed Justin’s likely education in a Palestinian Jewish milieu, and the traces in his writing of the conflicted voices of Jewish and Gentile Christians in the aftermath of the Bar Kochba revolt.

A second strand has been Justin’s representation of the Jews. The figure of Trypho has naturally been key here. Where some have seen in him an exemplar of an authentic pre-rabbinic Diaspora Jew,[31] and perhaps even a germane historical basis to the dialogue,[32] others have seen only a hostile caricature of an intellectually weak opponent against which Justin could project his supercessionist argument with no risk of defeat.[33] Most important here has been Judith Lieu’s seminal Image and Reality, which covers Justin in two chapters—one on the Dialogue with Trypho and one on the apologists—analysing how Christian authors in 2d century Asia Minor in general constructed the Jews as literary motifs.[34]

Such work has been hugely important. As with the other traditions discussed here, however, scholarly predispositions and preoccupations have coloured its conclusions. Firstly, these studies largely use Justin to shed light on the broader issue of 2d-century Christian views of Jews and Judaism. This is often bound up with the question of what Justin can tell us about the so-called “parting of the ways.” But this, like work considered under Justin “Martyr” above, is often predicated on a model of religious opposition—in this case Christian and Jewish.[35] Justin is thus again understood as antagonist. Moreover, since scholars have increasingly suggested that Justin’s interest in Judaism is partly motivated by heresiological concerns about extremists like Marcion who wanted to throw the baby out with the bathwater, this is ultimately concerned with Justin’s positioning amongst other Christians, again privileging his Christianity. Third, those works that focus on Justin’s engagement with Jewish texts are necessarily positioning him against a past Judaism. As with other approaches, this neglects Justin’s concrete enmeshment in his contemporary environment. Justin’s engagement with contemporary Judaism remains either out of focus or a matter of controversy. David Rokéah, for example, denies any such influence in his study of Justin’s debt in this regard to earlier Christian writing, especially Paul, arguing that Justin did not know Hebrew, Philo or midrashic material.[36]

Naturally, these approaches are more concerned with the Dialogue with Trypho than the Apologies (though the proof-from-prophecy sections of the First Apology are important in discussions of Justin’s use of the LXX). However, their advances are important for our present project on the Apologies. The complexity of Justin’s presentation of Jews and Jewishness in particular casts another spotlight, alongside that discussed above, onto the search for self-definition under the Roman principate, in which myriad competing and shifting communities tried to create unique identities over and against others, even as they went about the conflicting task of constructing a sense of belonging. That all of this took place under the aegis of the Roman emperor as arch-adjudicator injected a tangible material impetus to the game of identity.[37] So most recently, Maren Niehoff has argued that Justin sought to rhetorically position himself as Roman, and Trypho (and Jews more generally) as deviant, Greek, and “other.”[38] Though perhaps too neat in its presentation of Greek as “other” for a 2d-century educated Roman audience, this does showcase both how consideration of these complex background dynamics deepens our understanding of Justin’s rhetoric, and how peeling back that rhetoric offers fresh perspectives on those 2d-century social dynamics themselves. We thus hope that our approach will stimulate new considerations of how Justin’s discussion of Judaism is implicated in his experience of the mid–2d-century Roman Empire, including his concrete engagement with 2d-century Judaism.

4 Justin the Philosopher

Two of the most recent works on the Dialogue with Trypho, by Andrew Hayes and Matthias Den Dulk, have argued that it is fundamentally heresiological, and can thus be profitably read alongside contemporary philosophical discourse, which was similarly interested in internal group boundary-formation.[39] It is with philosophy that Justin has been best embedded in his wider context. He begins the Dialogue with Trypho by describing how “While I was walking one morning through the colonnades of the Xystus, a certain man, with others in his company, met me. Trypho: ‘Hail, O philosopher!’”[40] Justin here directly and indirectly paints himself in philosophical terms. He goes on to give us a description of his philosophical journey to Christianity, explaining how he tried—and found wanting—Stoicism, the Peripatetics, Pythagoreanism, and finally Platonism, before arriving at the “true” philosophy.[41] Tertullian, as we have seen, privileges this moniker alongside that of “martyr.”[42]

Modern scholars have taken that hint to read Justin against the Greek philosophical tradition. A string of studies in the second half of the 20th century saw a debate on the extent of Justin’s engagement with contemporary philosophy, and Platonism in particular. Though consensus has veered wildly here,[43] most scholars today would broadly accept Justin’s Platonism, at least to some extent.[44] But the effort to understand the degree and consequences of the dependency continues.[45]

In the philosophical arena then Justin has been systematically read within his contemporary intellectual backdrop. Most of this work has focused on the Dialogue with Trypho rather than the Apologies. And it has for the most part looked to a fundamentally theological or philosophical, rather than literary or historical, payoff.[46] But the exceptions build towards our own interests in this special collection. For example, as was realised already a century ago, Justin’s philosophical origin story in the opening of the Dialogue echoes the pedagogical peregrinations narrated by Lucian of Samosata in his Menippus.[47] All studies of Justin’s philosophy have grappled with this, since it influences the degree to which readers credit the historicity of his CV. More interesting for our purposes is why such a description was valuable to Justin. Whether Justin was really a philosopher (which is premised on a series of unhelpful value judgements) is less important than what work that label performed, practically, in Justin’s world, and what he gained and risked by claiming it. Similar questions are raised by considerations about the degree to which Justin’s Apologies are indebted, in direct and indirect ways, to Plato’s Apology of Socrates,[48] as well as by discussions about the importance of “good pagan philosophers”—like Socrates—to Justin’s view of history, the operation of his logos spermatikos, and his apologetic strategy.[49]

This taps into a broader scholarly interest in philosophy as a rhetorical stance under the empire. Extensive recent work has proved that Christians were part and parcel of this same intellectual world. As Kendra Eshleman has shown perhaps most effectively, Christian writers of this period moved in the same social circles, engaged in the same pedagogical competitions, and employed the same rhetorical strategies, as their non-Christian contemporaries.[50] Justin was no exception: a private teacher of philosophy in Rome, running his own school,[51] and competing for pupils and prestige.[52] Such readings have revealed Justin as above all more precarious than his canonical status suggests.[53] This living context, read together with the more accurate picture of persecution and personal risk under the empire alluded to above, represents an important launching pad for a number of our papers.[54]

5 Justin the Apologist

One reason for the sparser treatment of Justin’s Apologies in Jewish and philosophical terms—and thus their relative neglect in precisely those areas where Justin has been better embedded in his wider contemporary Graeco-Roman context—is, we suggest, because most work on them has been primarily interested in Justin’s place in the Christian apologetic corpus. Robert Grant’s seminal Greek Apologists of the Second Century best exemplifies this. This chronological treatment of the Greek apologists and their interactions offered an intellectual history of Christian apology.[55] Grant advocated that the apologists be read “of their moment.”[56] But in practice this meant weaving a selective chronological narrative of Roman imperial history into his account of the development of apology, pinning steps in the latter with precise moments in the former. So, for example, he argues that Justin was spurred to write by the martyrdom of Polycarp in 155 or 156,[57] and that Antoninus Pius perhaps wrote letters to Hellenic cities in response to Justin.[58] But such jigsaw-puzzle history is both vulnerable—to, for example, re-datings of our few pieces of evidence[59]—and fundamentally thin, since it anchors Christian authors to piecemeal events rather than engaging systematically with their contemporary society.

Grant also exemplifies a further problem with such approaches. Since he is interested in the genre of Christian apology, the terms of his project mean that Justin and the other Greek apologists are read against each other. He identifies the origins of apologetic in the New Testament, seeing Justin and his successors as emerging from the accommodationist thread nascent there.[60] Despite Justin never referring to Paul explicitly, Grant maintains that “he uses patterns of exegesis that are certainly Pauline in origin.”[61] The wider world is relevant only in so far as it informs these Judaeo-Christian precedents—Berossos and Manetho because they influenced Philo and Josephus; Menander, Epimenides and Aratus because Paul or deutero-Paul quoted them.[62] Grant’s apologists are thus intellectually formed entirely by Christian precedent. Grant’s section headings make clear that his focus, despite an apparent interest in the wider world, remains above all internal: liturgy; Bible; theology.[63]

Such an approach remains familiar. Despite the increasing tendency to pay lip service to the importance of context, Justin’s Apologies are still largely read against other Christian texts. The important edited collection of Sara Parvis and Paul Foster, Justin Martyr and His Worlds, illustrates the longevity of this tendency.[64] Despite its title, and beyond two opening important technical studies on the Apologies, it is almost exclusively interested in Justin’s Christianity. Its longest section contains five papers on his use of the Bible;[65] the next largest, on “Justin and His Tradition,” contains one paper on Justin and Hellenism but otherwise focuses exclusively on theology, liturgy, and Christian reception. Even more recently, David Nyström’s monograph on the Apologies focuses on Justin’s employment of theological strategies—the theft theory (enhanced by his logos doctrine), the proof from prophecy, and comparison with the demonic—and how Justin’s use of them differed from other Christian authors.[66]

Relatedly, in his recent commentary on the Apologies, Ulrich demonstrates Justin’s knowledge of, and proximity to, Graeco-Roman culture and education, and insightfully comments that a (secondary) aim of his was to show members of his Christian community that their religion, and at least some aspects of “pagan philosophy,” were congruent.[67] But even here, Justin’s Graeco-Roman cultural fluency is put at the service of his Christianity.[68] He is presented as labouring to make Christian knowledge understandable from a Graeco-Roman, implicitly pagan, perspective—as if, again, Christianity and the Graeco-Roman world are two exclusive systems of knowledge and identity between which the apologist builds a bridge. This in practice has a similar result as work that focuses only on the Christian context—Justin’s Apologies are read as distinct from the world in which they were written, and he is interpreted as a Christian (at best) translating Christian ideas for a Graeco-Roman context, rather than as himself simultaneously Greek, Roman, and Christian.

One consequence of this intra-Christian focus is that viewed within the narrow limits of early Christian apologetic Justin appears as inaugurator and innovator.[69] This framing certainly has value. Justin was indeed a major influence on his successors; Athenagoras, Tatian, most likely Melito of Sardis, Miltiades, Apollinaris (though we lack their complete texts), and Tertullian all wrote in his shadow and re-purposed his material.[70] Eusebius understood this in the early 4th century, and afforded Justin a key role in his own attempt to define the apologetic genre. So too did Arethas of Caesarea, whose assembly of apologetic texts in the 10th century (Parisinus graecus 451) helped establish this canon.[71] From the historian’s perspective, though, this focus is narrow and teleological. It may elucidate the evolution of the literary figure in subsequent centuries, but it occludes the historical man in 150s Rome.

When Justin wrote, there was no Christian apologetic genre. His supposed importance as innovator in fact highlights that the other Christian apologists, who necessarily postdate him, are not the proper interlocutors for the attempt to understand him in his own right. To do that, we must de-exceptionalise his Christianity, and take richer account of both the myriad literary cultures on which he drew, and the specific cultural and political institutions with which he engaged—not primarily, to contest and deconstruct them as a hostile sojourner (see section 2 above), but because they constituted his own social, intellectual, and political worlds. Doing so will help us access not the timeless apologist but the historical man—a contingent figure moulded by the world and writers around him.

6 Conclusion: Justin of Rome

This approach lies behind our chosen moniker, “Justin of Rome.” It indicates that we intend to emphasise his status as both inhabitant and, crucially, subject of the Roman empire. Justin wrote the Apologies in the 150s at Rome—an empowered subject from the empire’s margins, writing at its centre. Scholarship on what it meant to live and write from both has blossomed over the last thirty years. But that historiography has yet to transform our understanding of Justin’s Apologies (or indeed of many other early Christian figures).[72] Our goal is thus to explore the ways that Justin’s Apologies were moulded by, engaged with, appropriated, and manipulated their imperial context in pursuit of their literary and real-world goals. This Justin is thus fundamentally contingent.

This approach is situated within the Sitz im Leben tradition pioneered by Hermann Holfelder and Wolfram Kinzig, and recently employed by Jörg Ulrich and, most effectively, Laura Nasrallah (who also contributes in this special edition).[73] These authors have indeed paid close attention to the imperial context of the Apologies. The papers here build on this, while placing more emphasis on Justin’s position as a Roman subject and his legitimate claim to being a Greek intellectual (or at least, no less legitimate than those with whom he competed). They thus deprivilege his Christianity, which has been the starting point for almost all previous approaches.

Justin’s Apologies were influenced by his imperial Graeco-Roman context, we suggest, in two main ways, which we might label literary and historical (though as ever in practice that distinction usefully breaks down). First, Justin was one part of a rich, Mediterranean-wide literary tradition in multiple languages, employing shared rhetorical tools to negotiate identities within a world empire. As we have seen, scholars have belatedly included Christians in this conversation.[74] But they remain the beggars at the feast. Scholarship has yet to see in them the degree of sophistication seen in contemporary Greek authors. In particular, Tim Whitmarsh’s work has highlighted the multivalency of imperial Greek literature, and thus moved interpretation on from the simplistic binary between accommodation and resistance to empire which persists for Christian authors.[75]

Three papers bring Justin into dialogue with second sophistic literature. Whitmarsh himself applies the lens he pioneered to Justin, alongside his fellow apologist and possible pupil Tatian. Interrogating the authorial “I” in their writings, he demonstrates the subtlety of their self-presentation and self-construction, which parallels those of the non-Christian sophists his own work has revealed. Like Dio Chrysostom, in particular, Justin and Tatian mobilise the particularly rhetorical philosophy of their era, and its diverse genres and models, to produce complex identities best suited to the competitive landscape in which they operated. Eleni Bozia’s paper, similarly, represents a sustained and nuanced comparison between Justin’s First Apology and the most ludic of second sophistic authors, Lucian. Focusing on their respective attitudes to statue worship, she shows that they both employ cognitive estrangement and metacognition to push their readers to reflect on their own societies as if from the outside. Moreover, she argues that this particularly introspective characteristic of imperial literature was a productive force in practice, and thus that these narratological tools were key to Justin’s project to establish Christianity as a recognisable religious entity. James Corke-Webster’s paper, in turn, reveals not just Justin’s clear engagement with the themes and motifs of the extant Greek novels in his Second Apology, taking Achilles Tatius as exemplary, but the similarly complex way in which he plays with them, and, again, how this served his concrete historical purposes. All three papers thus show from different angles that Justin the Sophist deserves full integration into the pantheon of 2d-century Greek literature.

However, though he was born in the eastern provinces and wrote in Greek, Justin resided in the Italian capital. He should therefore be read alongside not just second sophistic Greek authors, but the Antonine Latin tradition. Much less has been done here. Corke-Webster’s paper thus also brings Justin into dialogue with the Latin Apology of Apuleius. Justin, he suggests, was employing the same defensive strategy as Apuleius, one built upon a claim to shared intellectual heritage with his judge, and tapping into an elite conceptual nexus between pedagogy, morality, and justice.[76] Again, this had twin concrete aims in his particular circumstances as a private teacher—both a prophylactic strategy against opportunistic accusation, and an advertisement of his wares. Next, Ben Kolbeck’s paper reads Justin alongside the less well-known Phlegon of Tralles, showing that both mobilise the same literary strategy of directing readers to state archives as a guarantor of the veracity of their claims to the miraculous. That both the Greek and the Latin traditions enable us to better understand his Apologies demonstrates clearly that Justin was a properly imperial author, and must be read as such.

Kolbeck’s paper also brings us to the second major theme of the essays, namely that Justin cannot be separated from the concrete realia of 2d-century Roman life. Building on Ari Bryen’s work on how Justin and other Christians were working with and within the mechanisms and principles of the Roman judicial system,[77] Kolbeck demonstrates that Justin’s appeals to imagined documentary evidence are built on not just the entire infrastructure of Roman archival practice, but a series of heuristic assumptions about accessibility and authenticity. Exposing that mental framework demonstrates not just a missing element in our understanding of Justin’s rhetoric, but that his Apology only works within the imagined world of the imperial subject, incorporating the structures of empire in its attempts at meaning-making.

This focus on realia is inspired in part by Laura Nasrallah’s path-breaking work embedding the apologists in contemporary architectural landscapes and archival practice.[78] Nasrallah’s own paper here adds a new dimension to this earlier work, reading the extensive material in the Apologies on demons alongside the ubiquitous deposition of so-called defixiones, or curse tablets, in the Roman world. She treats the latter here as judicial archives—an alternative route to effective justice parallel to that offered by the Roman government. Seen thus, Justin’s apparent obsession with the demonic becomes not a feature of his Judaeo-Christian heritage but a feature of Roman-ness. Nasrallah thus not only shines a spotlight on a further neglected aspect of the Apologies, but demonstrates how it is explicable only when read from the perspective of Rome on—or in this case under—the ground.

These papers taken together demonstrate how these two approaches, the literary and the historical, go hand in hand. Culture and administration were not separate fields of knowledge in antiquity, but deeply intertwined, since the empire was ruled by an elite who predicated their right to do so on their cultural superiority. Educated Christians were part of that elite and shared that mentality, alternately profiting off its dynamics and chafing at its restrictions and iniquities. This is perhaps best demonstrated in the intensely agonistic culture of contemporary public sophistic performance.[79] The goals identified here as characteristic of the Apologies—to carve out a distinct public persona which nonetheless drew on existing material and styles; to demonstrate one’s literary, rhetorical, and practical competence; to be properly philosophical; to court the favour of both public and rulers; to access reward and resources; and above all to avoid the threat not only to reputation, but also life and limb which lay latent in failure—are all characteristic of public performance under the empire more broadly.[80] What is striking is not just how closely such conditions match the claims made by Christians of their environment, but how unnecessary is their Christianity as an explanation for their experience. A key contribution of our approach, then, is that it allows us to see in stark clarity the nature of the early Christian manoeuvre. It is not that they invented their experiences under empire.[81] It is that they wrote them up as if they were unique, sowing the seeds of the Christian exceptionalism that has plagued our understanding ever since.

In turn, this helps transform our understanding of Christian apology more broadly. Read thus, it appears a more natural, understandable, and contingent genre than has generally been allowed by scholars of early Christianity. It becomes both more familiar and more complex, rooted in traditional apologetic but influenced by the broad literary and rhetorical landscape, and catalysed by the particular historical circumstances of the mid–2d century Roman empire. And precisely because of that, it also has much more to tell us about the experience of being a Roman subject than has been realised by classicists and ancient historians. Finally, eroding those elements that appear to make Justin and his Apologies distinctive and even singular, and mobilising early Christian writings to better understand antiquity, cuts across and thus helps to dismantle those cultural barriers between Christians and their contemporaries that generations of theology and disciplinary resource-allocation have erected.

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Titelseiten

- Justin of Rome: Introduction

- Read it in Rome: Miracles, Documents, and an Empire of Knowledge in Justin Martyr’s First Apology

- Apologists on Trials: Justin’s Second Apology, the Literary Courtroom, and Pleading Philosophy

- Making Justice: Justin Martyr and a Curse From Amathous, Cyprus

- To Know Thyself Through the Other: The Literary Convergences of Lucian and Justin

- Justin, Tatian and the Forging of a Christian Voice

- Edition

- Der pseudoaugustinische Sermo 167: Beobachtungen und Überlegungen zu Ursprung und Überlieferung mitsamt einer Edition seiner vermuteten Vorlage

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Titelseiten

- Justin of Rome: Introduction

- Read it in Rome: Miracles, Documents, and an Empire of Knowledge in Justin Martyr’s First Apology

- Apologists on Trials: Justin’s Second Apology, the Literary Courtroom, and Pleading Philosophy

- Making Justice: Justin Martyr and a Curse From Amathous, Cyprus

- To Know Thyself Through the Other: The Literary Convergences of Lucian and Justin

- Justin, Tatian and the Forging of a Christian Voice

- Edition

- Der pseudoaugustinische Sermo 167: Beobachtungen und Überlegungen zu Ursprung und Überlieferung mitsamt einer Edition seiner vermuteten Vorlage