Abstract

Globally, teachers hold a pivotal role in the professionalization of the TVET sector. However, there are still limited initiatives aimed at developing comprehensive approaches to equipping TVET educators with the competencies required for effective teaching and learning in technical vocational education and training (TVET). This paper underscores the necessity for TVET teachers to possess an integrated set of competencies. On one side, they require domain-specific expertise linked to their professional field, while on the other side, they must demonstrate personal, social, and work-process-related skills, alongside pedagogical and methodological-didactical abilities at a scientifically sound level. Cultivating these competencies and enabling teachers to carry out their responsibilities demand a sophisticated combination of the aforementioned competence areas, particularly integrating the aspects of “vocational pedagogy” and professional expertise as a “subject”. The paper’s argumentation is supported by a comparative analysis of teacher training strategies in various countries, highlighting international efforts to meet this challenge. Moreover, the paper examines initiatives led by political organizations to establish standards that reflect the intricate nature of teaching competencies.

1 Framing the Analysis

The notion that vocational education and training are fundamental to societal advancement has been echoed in numerous policy frameworks. In recent years, this perspective has gained significant traction among education policy stakeholders in both public and private sectors worldwide. A key reference in this context is the 2012 Shanghai Consensus, which offers recommendations for advancing technical and vocational education. This document serves as a critical message to UNESCO member states, urging them to enhance the relevance of vocational education and training across all regions (cf. ILO-UNESCO 2012).

With the growing prominence of TVET, the question of how and where TVET teachers should be trained has become increasingly central. Furthermore, identifying the professional profiles that would best suit TVET educators is of great importance in this discussion. This paper aims to address these questions through a case-based analysis of TVET teacher education in selected countries. While Hattie (2009) emphasizes the critical role of teachers across different educational systems, his extensive research does not specifically address TVET. Nonetheless, the necessity of training teachers specifically for the vocational education sector remains undervalued in many regions.

2 Outlining Trends in Selected Countries

Based on involvement in various projects, the author has gained insights into recent developments in TVET teacher education in Cambodia, Moldova, Vietnam, and Germany. The analysis of country-specific advancements is used to illustrate and highlight emerging trends. However, a comprehensive account of the developments in these nations cannot be fully explored in this paper and will be detailed in an upcoming publication (Becker and Spöttl 2022).

In general, teacher education programs in the four countries examined exhibit significant heterogeneity, a reflection of the diversity within their respective TVET systems. This variance is also mirrored in the differing profiles of TVET educators across these nations. For instance, while Germany adheres to the Bologna framework, Cambodia and Vietnam have developed unique educational models. Moldova, on the other hand, adopts European approaches with some alignment to the Bologna system. These varying approaches are a consequence of the political, cultural, economic, and social distinctions between the countries. Notably, there is only a limited focus on adopting higher standards in most cases. This trend is evident in the future planning of program expansion across the countries under consideration.

Although overarching standards may serve as a guideline for further program development, regional needs ultimately take precedence. This is evident in the emphasis placed on economic trends and educational policy requirements, which play a critical role in shaping TVET teacher education in each nation. These requirements often include considerations for social integration, conflict management, sustainability, and other relevant societal issues.

For Cambodia and Vietnam, the analysis of their program approaches can be summarized into three key areas:

Enhancing the quality of vocational education learning;

Developing vocational pedagogical competencies among teaching staff, particularly in the design of learning experiences;

Fostering subject-specific competencies among TVET educators.

Achieving these three objectives necessitates comprehensive and robust teacher training programs, which can only be effectively implemented through professional, pre-service training. A closer look at current training structures reveals significant gaps in standards and regulations. In Cambodia, for instance, educational standards have been broadly defined, yet their application remains underdeveloped. Conversely, Vietnam has established national standards, although these are inconsistently applied at the institutional level. Nevertheless, these standards are becoming increasingly influential, especially in the accreditation of vocational schools and the assessment of teacher competencies.

In summary, the design and implementation of pre-service teacher education for vocational education vary significantly between Cambodia and Vietnam, with even greater disparities evident in their in-service training programs. These differences can largely be attributed to the distinct trajectories of their educational systems and the varying responsibilities of the respective ministries overseeing them.

3 Moldova’s Approach

Moldova’s priority is to continue on its current path of TVET teacher education reform, with key focus areas that include:

Development of visual teaching materials. This encompasses creating didactic materials that align with learning outcomes and educational approaches, personalizing the visualization of educational content, employing diverse artistic and technological methods, and assessing the quality of the materials produced.

Training of pedagogical skills. This involves designing specific strategies for teaching, learning, and assessing facts, concepts, principles, processes, and procedures. It also includes developing project-based curricula, such as the learning matrix “Performance-Content” for theoretical instruction, and designing project-based didactic materials.

Assessment of practical skills. This includes creating assessment criteria for objectively evaluating learning outcomes, developing testing instruments, enhancing the validity and reliability of these tools, and interpreting assessment results to improve the quality of training (cf. Vodita et al. 2022, p. 314 f.).

To ensure the sustainability of these advancements, the Technical University of Moldova has taken the lead in establishing a new pre-service teacher training program. This initiative, developed in collaboration with both national and international partners, will be aligned with UNESCO/UNEVOC standards (cf. UNESCO-UNEVOC 2004). Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg is playing an active role in supporting this process.

Relevant dialogue partners at the national level, including the Ministry of Education and Research, higher education institutions, the National Accreditation and Quality Assurance Agency, and dual partners from both VET providers and the business sector, have engaged in discussions to analyze the various components and steps necessary for the development of a study program. These discussions encompass adjustments to the normative framework, accreditation procedures, the development of teaching and learning materials, and financial considerations. Additionally, there was a strong recognition of the need for capacity development among potential lecturers who would be involved in the implementation of the Master’s study program in Moldova.

As a result of these dialogues, a draft work plan, complete with milestones, activities, and deliverables, was developed. This plan sets out the goal of launching the MA Study Program at the Technical University of Moldova by September 2021 (cf. Vodita et al. 2022, p. 316 f.).

4 The Situation in Germany

In Germany, the focus has shifted from merely professionalizing the training of TVET teachers to addressing more strategic questions about how study programs for TVET educators should be positioned within universities and which educational model would be the most suitable. The key models under consideration include:

Consecutive model

Top-up model

Blended learning model

The ongoing debate centers around the quality of training that can be achieved for the future demands of TVET teaching. Special attention is given to how these programs can adapt to the growing digitalization of education, the balance between theoretical and practical training, and the depth of academic instruction required (cf. Bünning 2022, p. 497 ff.).

With the increasing demand for TVET teachers in Germany, particularly in technical vocational fields, there has been significant discussion around the Bachelor-Master model. This model is seen as a potential solution for recruiting and preparing career changers for teaching positions in TVET institutions. The top-up model, in particular, holds considerable promise in addressing the growing demand for qualified TVET educators.

5 Challenges in TVET Teacher Education Globally

In many countries, TVET teacher education, which includes the training of vocational trainers, is still viewed as a practice that can be developed “on the job”. In these settings, there are often no established career paths for individuals aspiring to become vocational teachers or trainers, nor are there clear training pathways through pre-service or in-service programs. This lack of structured training leads to significant challenges in the quality of vocational education and training, as inadequately prepared staff struggle to deliver education that meets quality standards.

Several international guidelines published in the past decade underscore the increasing significance of vocational education and training. Notably, the UNESCO Recommendation on Vocational Education and Training (cf. UNESCO 2016a) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals Framework (cf. UN 2015) highlight the crucial role TVET plays not only in fostering an economically productive workforce but also in supporting personal development and social cohesion – factors that are essential for achieving a sustainable future.

In many low-income countries, the provision of vocational education remains limited, financial investment in this area is insufficient, and the quality of both teachers and educational programs is inadequate. A study conducted by UNESCO-UNEVOC (2020) revealed that the primary reason TVET teacher training is not mandated in various countries is not due to a lack of funding or awareness of the benefits of in-service training, but rather the absence of effective systems and trained personnel with the requisite expertise to offer high-quality guidance and instruction.

The paper Teachers in the Asian-Pacific (cf. UNESCO 2016b) highlights additional considerations for TVET personnel. It emphasizes that their skills must:

go beyond the mastery of job-specific skills,

and instead focus on cultivating high-level cognitive and non-cognitive skills, such as problem-solving, critical thinking, creativity, teamwork, communication, and conflict resolution.

Furthermore, the paper calls for enhanced cross-border recognition of relevant qualifications and quality assurance mechanisms. This development is expected to directly influence teacher and student mobility, as well as the processes used to evaluate teachers (ibid).

In light of the ongoing challenges in professional education, greater attention needs to be directed towards transforming the attitudes, approaches, and professional activities of teachers and trainers (cf. Dittrich et al. 2009). Teachers are being tasked with increasingly complex roles, making them key players in successful reform and innovation within the TVET sector. However, TVET educator training and development often receive insufficient attention (cf. Maropeet al. 2015). Therefore, it is critical that TVET personnel become a focal point in international education policy discussions. The increasing significance of TVET, its unique role in bridging education and employment, and the complexity of TVET teaching highlight the need for more international peer learning and guidance in this area (cf. Rawkins 2018).

In a recent policy review by the OECD (cf. OECD 2021), a central role was ascribed to TVET teachers, who are required to have a “dual qualification” encompassing both pedagogical knowledge and practical industrial experience. As labor market demands evolve, it is essential that vocational education adapt to these changes while ensuring that TVET teachers are equipped with new pedagogical methods, the use of emerging technologies in teaching, and an understanding of current industrial practices.

The OECD recommends that programs aimed at both initial and in-service training for TVET teachers should provide a balanced mix of pedagogical skills, digital and social competencies, as well as the professional expertise required by the labor market. To achieve this, it is crucial that the curricula for teacher education remain continuously updated and be developed in close collaboration with vocational training institutions. Offering practical vocational learning experiences within industry settings as part of teacher training is seen as particularly beneficial.

According to the OECD, the ever-changing teaching and learning environments, coupled with shifting labor market requirements, mean that TVET teachers must continuously develop and enhance their competencies even after completing their formal training (cf. ibid).

Similarly, the Council of the European Union (2020, pp. 7–9) outlined conclusions for the qualification of future teachers, emphasizing the following:

Continuous professional development for teachers and trainers should be regarded as a prerequisite for high-quality education and training. Teachers and trainers should be encouraged to reflect on their methods, recognize their need for further development, and be supported through high-quality training opportunities and incentives.

Education and training institutions should foster effective, research-based opportunities for professional development, encouraging collaboration, peer observation, peer learning, consultation, mentoring, and networking. These opportunities should expand to include microlearning units, such as “microcredentials”, with accompanying quality assurance measures.

Professional development should also emphasize mobility in both physical and virtual spaces, integrating such experiences into the internationalization strategies of teachers and trainers. European instruments like e-Twinning and EPALE (Electronic Platform for Adult Education in Europe) could serve as valuable tools in this effort (cf. ibid, p. 7).

These reflections on TVET teacher training highlight the broad requirements for TVET educator development, yet leave open the question of which institutions are primarily responsible for providing this training. While the wide range of requirements, particularly those influenced by labor market developments, is well described, there remains uncertainty about where teachers should ideally receive both initial and in-service training. This ambiguity creates challenges for national planners in charge of designing teacher training programs. Additionally, the various national actors involved in teacher training and quality assurance often have differing perspectives, contributing to further complexity at the national level.

6 Structure and Standards of TVET Teacher Education

Approaches to teacher training in the TVET sector vary significantly from country to country due to differing cultural contexts and educational requirements, as illustrated by the following examples.

6.1 Cambodia and Vietnam

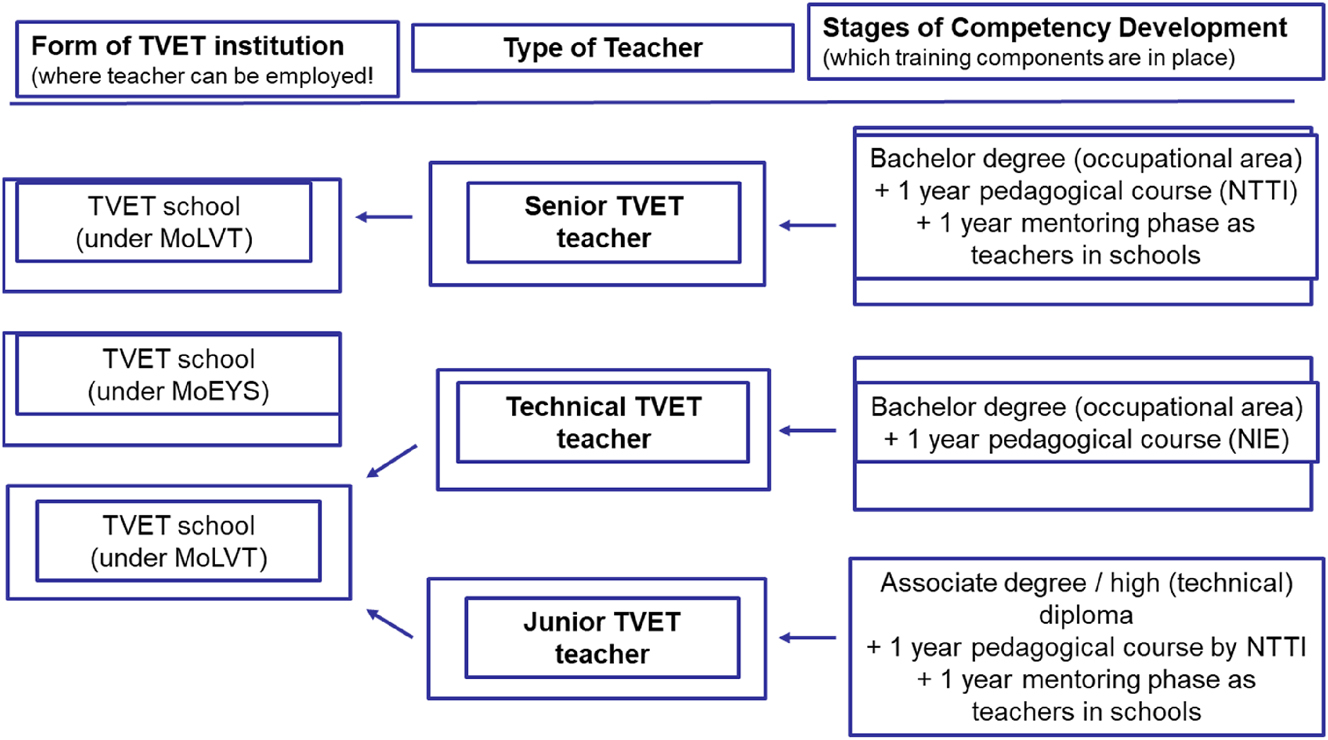

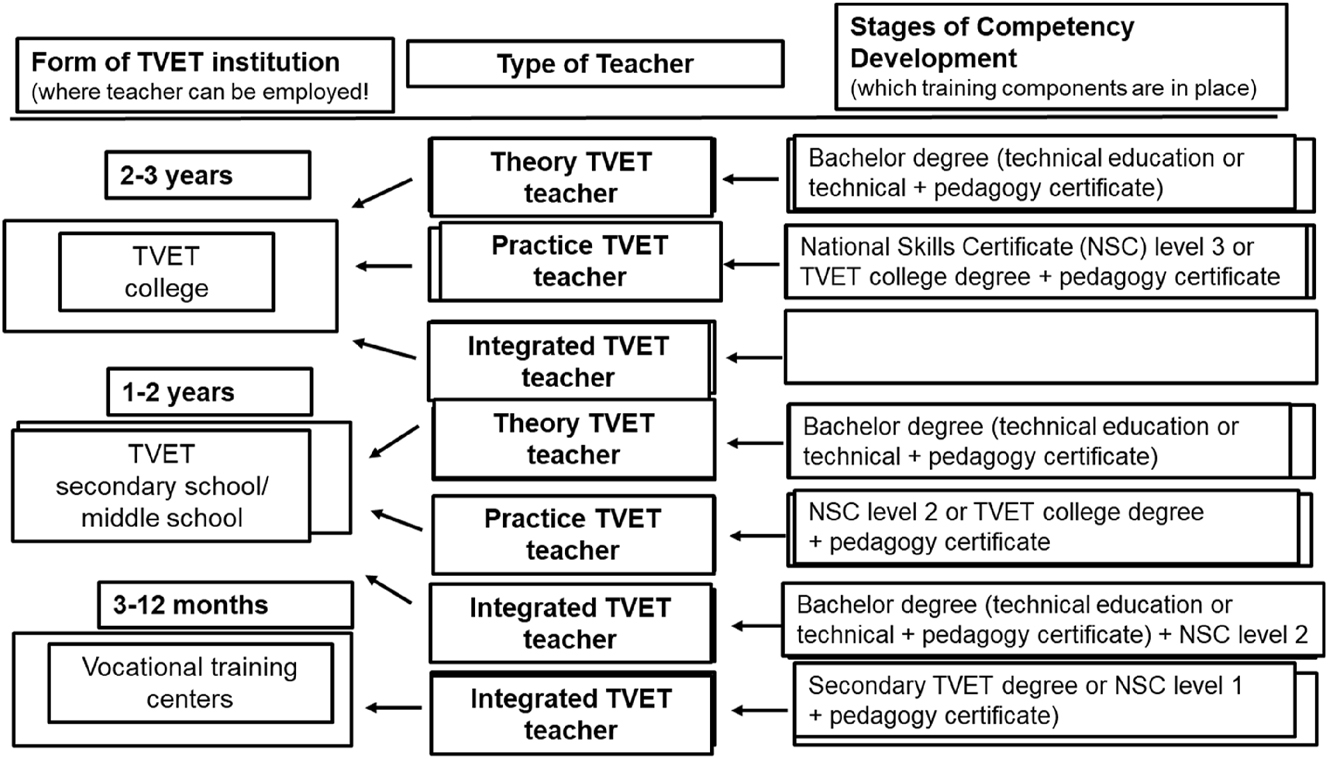

In both Cambodia and Vietnam, it is notable that in-service teacher training is not exclusively structured as Bachelor’s degree programs (see Figures 1 and 2). Instead, certificate-based courses are offered by continuing education providers that have been accredited by the respective ministries. The nature of these programs is highly diverse, leading to a wide range of certification types. A distinctive feature of these programs is the inclusion of substantial practical phases, often lasting up to one year.

Cambodia. National Teacher Training Institute (NTTI). Source: Euler (2018) (GIZ-RECOTVET).

Vietnam. NSC = National Skills Certificate. Source: Euler (2018) (GIZ-RECOTVET).

In Vietnam, for instance, 25 % of the technical teacher education programs must be conducted in university workshops or within companies, ensuring a strong connection between theoretical education and practical industry experience. The diversity in Vietnam’s training approaches can be attributed to the absence of a standardized framework governing the design of these programs. This results in a broad range of training pathways that are tailored to local needs but lack consistency across regions.

In Cambodia, while the variety of programs is less pronounced than in Vietnam, national standards have played a minimal role in shaping teacher education programs. As a result, there remains a significant degree of variability in the structure and content of teacher training courses in both countries (cf. Bünning et al. 2022; Euler 2018).

This comparison highlights the broader challenges faced by TVET systems in these nations, where the absence of overarching standards leads to a wide array of program types, making it difficult to ensure consistency in the quality of teacher training across different regions and institutions.

6.2 Vietnam

In Vietnam, two main types of teacher education programs exist. On one hand, there are consecutive programs, where technical studies are followed by pedagogical training. On the other hand, concurrent programs are offered, integrating both technical and pedagogical components simultaneously. Depending on the program, students may earn a bachelor’s degree or obtain certification in either pedagogical or technical studies – or in some cases, both. The qualification level varies based on the type of school for which the students are being prepared.

As for Cambodia, it distinguishes between junior degree programs, which require an associate degree or diploma for entry, and senior degree programs, where a bachelor’s degree is necessary for admission (cf. Bünning et al. 2022; Euler 2018, p. 24).

6.3 Moldova

In Moldova, TVET teacher education is structured around a university Master’s degree, which builds on a subject-specific Bachelor’s degree. Over the past five years, Moldova has undertaken significant reforms in vocational education and training (VET), aligning with the Moldovan TVET Strategy 2013 – 2020 (cf. VET 2013). These reforms aim to modernize the TVET system and tailor it to the needs of the private sector. The initial phase of reform included restructuring the network of TVET institutions and revising the legal framework to create a more responsive and industry-aligned TVET system. A key focus has been the development of curricula that emphasize practical and work-related skills to ensure students are better equipped for employment.

However, one of the ongoing challenges is the insufficient competences of the teaching personnel to meet the requirements of a modern vocational training system. While universities offer continuing education courses for TVET educators, these programs do not fully address the range of competencies required and are not universally accepted by all teachers.

To address these gaps, it is expected that teachers will engage in continuous professional development according to the specific needs of their TVET centers. This approach is complemented by encouraging educators to develop a professional development portfolio by participating in ongoing training programs.

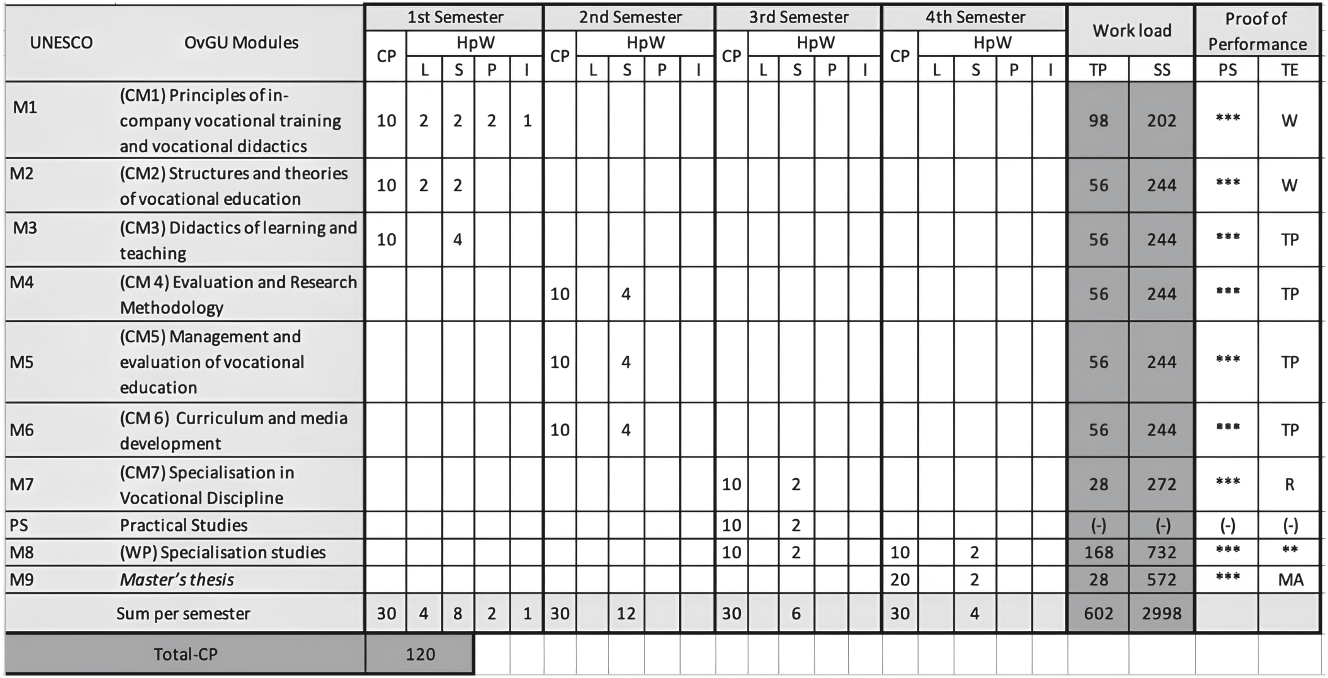

Currently, a Master’s degree program for the vocational education of teachers is under development through collaboration between the Technical University of Moldova and the Otto von Guericke University Magdeburg (OvGU) (cf. Vodita et al. 2022, p. 309 ff.). This program, outlined in Figure 3, is modular in nature and designed to be flexible, offering students multiple pathways to pursue various employment opportunities and teaching roles.

OvGU UNESCO based curriculum outline. M module, HpW hours distribution by activities, TP face to face teaching hours, SS workload in total, TE examination form, L lecture, S seminar, P practical lesson, PS credit value.

Without exception, the concepts for study programs across these countries are modular and flexible. Each country offers diverse pathways, providing students with opportunities to follow different career tracks and take on a range of teaching responsibilities.

6.4 Germany

Germany has implemented a two-cycle system for TVET teacher training, marking a significant shift from its traditional one-block degree program. Historically, TVET teacher training involved a single, continuous university program lasting four to five years, with two required internship placements (Praktikum). Upon completion, students would take the First State Exam, followed by a probationary period known as Referendariat (lasting one and a half to two years), which culminated in the Second State Exam.

The introduction of the two-cycle system reflects broader changes aimed at aligning with both national and international frameworks. The first cycle leads to a Bachelor’s degree, granting access to second-cycle (Master’s) programs, which in turn offer pathways to doctoral studies. However, this two-level system applies only to the university phase of teacher training. A significant challenge for curriculum designers lies in determining how to integrate the traditional probationary period (Referendariat) within the new two-cycle structure.

The proponents of this system anticipated that its implementation would open new career opportunities for graduates of TVET teacher training programs. The flexibility inherent in the two-cycle system was seen as a way for students to explore alternative career paths at various stages of their studies, instead of being restricted to a singular teaching trajectory. This adaptability is considered crucial in responding to the rapidly evolving job market (cf. Thierack 2004, p. 26; Bünning 2022, p. 479 ff.).

7 Competence Development in Vocational Education

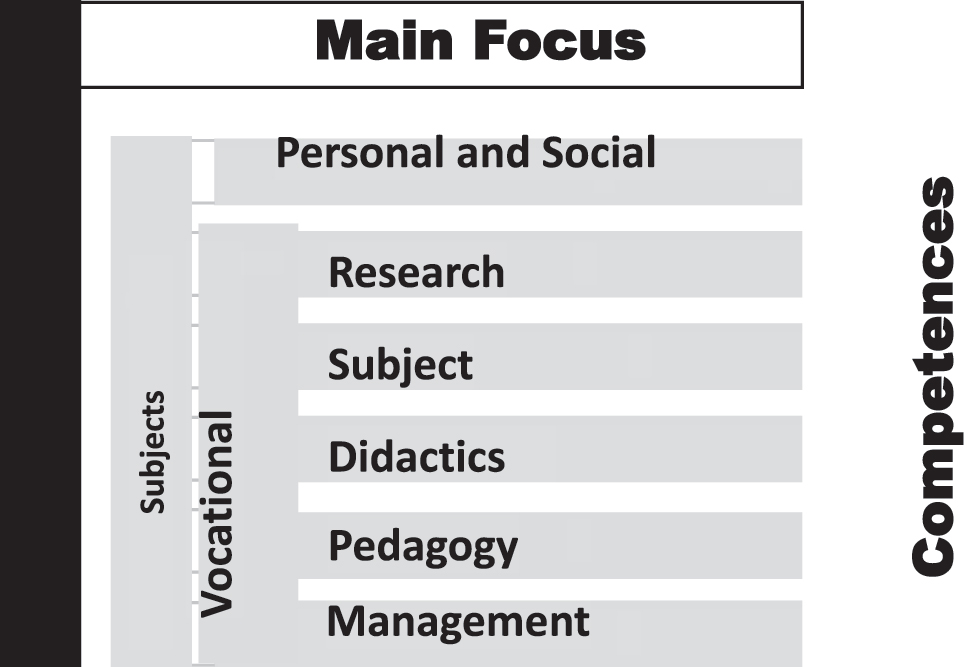

The discussions thus far highlight how international trends and research on teacher qualifications can be adapted to the specific needs of vocational and technical education. At the core of these efforts is the recognition that TVET teachers require a close integration of various competence areas. They must possess vocational competences related to their specific discipline, as well as personal, social, work process-related, and pedagogical competences, particularly in terms of scientifically grounded methodological-didactical skills.

In light of technological and social changes, these competence areas must also include digitalization and sustainability considerations, with a focus on preparing for “green professions” (cf. Beecker et al. 2019). The integration of these evolving areas ensures that TVET teachers are equipped to navigate the demands of the modern workforce.

The development of these competencies, and the empowerment of teachers to implement them, require a holistic approach that interlinks all these areas. Specifically, there must be a strong connection between vocational pedagogy and the vocational discipline as the “subject”. In general education, the subject matter for teachers is often defined by academic disciplines (e.g., biology for biology teachers, or technology for technology teachers). In contrast, vocational education teachers must operate with a “dual subject reference”, meaning their teaching is defined by vocational disciplines and the occupational roles they support.

8 Pedagogical Dimension in Vocational Education

The pedagogical dimension (Figure 4, cf. Becker and Spöttl 2022) in vocational education serves as a bridge between practical vocational tasks (related to identifying, preparing, and performing work) and the learning content and processes that support this work. This bridging function, reinforced by the concept of “vocational”, ensures that teaching in TVET contexts aligns closely with professional requirements, distinguishing it from general subject teaching.

Areas of competence for standards for teachers in vocational training (Bünning et al. in print).

Vocational learning processes play a critical role in securing vocational competence, enabling learners to perform effectively in the world of work. This vocational ability to act underpins the distinctiveness of TVET learning, emphasizing the practical application of skills in real-world occupational settings. This approach ensures that learners not only acquire theoretical knowledge but also develop the practical competencies necessary for success in the labor market.

9 Competence Areas and Integration in TVET Teacher Education

It remains a significant challenge to differentiate between the various competence areas while simultaneously integrating them into a unified standard for TVET teacher education. Competences in the real world are not isolated; they are demonstrated as outcomes, particularly through achievements in occupational performance in relation to specific tasks. Therefore, the standards for TVET teachers are framed as competences, which represent expected outputs that align with recommendations for process and input.

The standards consist of two holistic competence areas, which are expressed as tasks for teachers in vocational education (cf. Becker and Spöttl 2022, p. 23 ff.):

Personal and Social Competences. These describe the competences of vocational education teachers who not only identify with the vocational school as an institution but also with the educational system as a whole. This includes the personal attitudes required for the continuous development of one’s skills and competences.

Vocational Research, Subject, Didactics, Pedagogical, and Management Competences. These encompass the competences needed to identify, prepare, and deliver instruction that is focused on vocational fields, building on expertise in a specific vocational specialty. This competence area is divided into several categories.

Occupational (Educational) Research: Competences in identifying occupational competence requirements, understanding developments in the world of work, and determining the instructional needs associated with these developments.

Vocational Specialization: Competences in analyzing a vocational field (e.g., manufacturing, automotive engineering) and recognizing the related requirements and transformations occurring in the workforce.

Vocational Didactics: Competences in selecting, structuring, and applying relevant content and methods to foster effective vocational learning processes.

Vocational Pedagogy: Competences in planning, implementing, and evaluating learning units tailored to vocational contexts.

Vocational Management: Competences in organizing and developing vocational schools and TVET programs.

10 Conclusions

The explanations provided highlight that international organizations such as the ILO and UNESCO have explored a variety of methods for professionalizing TVET teacher education systems. While standards have been introduced, they often lack the specificity required to be directly applied to quality development and assurance. In the final sections of the article, the key dimensions for quality development are discussed, particularly in terms of their interrelationships. The subject-specific dimension of professional disciplines is particularly crucial. A major point of interest lies in the potential usability of such approaches, not only for designing standards but also for structuring the work of teachers in both school-based and in-company vocational training institutions.

However, it would be a mistake to formulate standards without first establishing a fundamental understanding of the level of teacher training required. The diverse requirements and tasks outlined in the article make it evident that a university education for TVET teachers is essential, and a Master’s degree should be the goal in order to ensure a comprehensive education. Such a degree guarantees a teacher profile that is well-prepared to handle the complex range of responsibilities required of TVET teachers.

Moreover, this degree program must introduce students to research methodologies, equipping them to engage with everyday professional challenges through research-based problem solving. In this article, a framework for defining standards was developed based on the key tasks of TVET. These tasks and standards must be validated through TVET-oriented research in each country, considering the close link between TVET and the labor market, particularly the needs of industry.

Before proceeding with standard development, two fundamental questions must be addressed in each country.

Should TVET teachers be generalists or specialists? This involves determining whether teachers should focus on general technical subjects or more discipline-specific or sector-related topics, such as automotive engineering.

Should TVET teacher training take place at the university level, resulting in Bachelor’s or Master’s degrees?

The answers to these questions depend on the specific country’s level of development in TVET and its educational policy goals. Only after resolving these questions can the development of robust standards begin.

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: None declared.

-

Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

Becker, Matthias, and Georg Spöttl. 2022. “Standards für die Lehrer*innenbildung – ein transnationales Referenzkonzept.” In Berufliche Arbeit und Berufsbildung zwischen Kontinuität und Innovation, Hrsg S. Anselmann, U. Faßhauer, H. H. Nepper, and L. Windelband, 23–38. wbv Media GmbH & Co. KG: Bielefeld.Suche in Google Scholar

Becker, Matthias, Georg Spöttl, and Lars Windelband. 2019. “Berufliche Fachdidaktiken/Berufsdidaktik im Spannungsfeld der Berufspädagogik und der gewerblich-technischen Fachrichtungen.” In bwp@Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik – online, Ausgabe 37, 1–21. http://www.bwpat.de/ausgabe37/becker_etal_bwpat37.pdf (accessed September 15, 2024) 13.00.Suche in Google Scholar

Bünning, Frank. 2022. “Models of TVET Teacher Education in Germany and their Potential to Meet Growing Demands in TVET Teacher Education.” In Technical and Vocational Teacher Education and Training in International and Development Co-Operation – Models, Approaches and Trends, edited by F. Bünning, G. Spöttl, and H. Stolte, 479–91. Singapore: Springer.10.1007/978-981-16-6474-8_28Suche in Google Scholar

Bünning, Frank, Georg Spöttl, and Harry Stolte, eds. 2022. Technical and Vocational Teacher Education and Training in International and Development Co-Operation – Models, Approaches and Trends. Singapore: Springer.10.1007/978-981-16-6474-8Suche in Google Scholar

Bünning, F., G. Spöttl, and H. Stolte. in print. “Qualification of TVET Teachers in an International Context – Status and Perspectives.” In Empowering Vocational Education in Georgia, edited by F. Bünning, and T. Henninge. WBV Bielefeld.Suche in Google Scholar

Dittrich, Joachim, Jailani Md. Yunos, Georg Spöttl, and Masriam Bukit, eds. 2009. Standardisation in TVET Teacher Education. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.10.3726/978-3-653-02366-4Suche in Google Scholar

Euler, Dieter. 2018. TVET Personnel in ASEAN. Investigation in Five ASEAN States. Detmold: EUSEL.Suche in Google Scholar

European Union. 2020. “Council Conclusions on European Teachers and Trainers for the Future.” Official Journal of the European Union C 193/04: 11 ff. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.C_.2020.193.01.0011.01.ENG (accessed October 1, 2024) 17.00.Suche in Google Scholar

Hattie, Joh A. C. 2009. Visible Learning – A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Abingdon: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

ILO-UNESCO, eds. 2012. Transforming TVET: Building Skills for Work and Life (Shanghai Consensus): Recommendations of the Third International Congress on Technical and Vocational Education and Training. Paris 2012. https://unevoc.unesco.org/home/Report:+Building+Skills+for+Work+and+Life,+Shanghai,+China,+13-16+May+2012:+Third+International+Congress+on+TVET&context (accessed September 30, 2024) 15.00.Suche in Google Scholar

Marope, Priscilla Toka Mmantsetsa, Borhene Chakroun, and King Holms. 2015. Unleashing the Potential: Transforming Technical and Vocational Education and Training. Paris: UNESCO.Suche in Google Scholar

OECD. 2021. Teachers and Leaders in Vocational Education and Training. OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training. Paris: OECD Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Rawkins, Christa. 2018. A Global Overview of TVET Teaching and Training: Current Issues, Trends and Recommendations. Joint ILO-UNESCO Committee of Experts on the Application of the Recommendations Concerning Teaching Personnel (CEART). Paris, Geneva: CEART.Suche in Google Scholar

Thierack, Anke. 2004. Lehramtsspezifische BA-MA-Studienkonzepte – offene Fragen für die Erziehungswissenschaften im Lehramt. http://www.uni-hannover.de/bama-lehr/download/thierack%20_vortrag0304.pdf (accessed October 4, 2024) 18.00.Suche in Google Scholar

UN, ed. 2015. United Nations Summit on Sustainable Development 2015. Informal summary. 25–27 September. New York: UN. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/8521Informal%20Summary%20-%20UN%20Summit%20on%20Sustainable%20Development%202015.pdf (accessed May 8, 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

UNESCO, eds. 2016a. Recommendation Concerning Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET). Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245178 (accessed October 1, 2024) 15.30.Suche in Google Scholar

UNESCO, eds. 2016b. Teachers in the Asia-Pacific: Career Progression and Professional Development. Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000246011 (accessed October 1, 2024) 15.30.Suche in Google Scholar

UNESCO-UNEVOC, eds. 2004. UNESCO International Meeting on Innovation and Excellence in TVET Teacher/Trainer Education. Documentation. Hangzhou 2004: UNESCO-UNEVOC. https://unevoc.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/pubs/Hangzhou_International_framework.pdf (accessed October 1, 2024) 15.30.Suche in Google Scholar

UNESCO-UNEVOC, eds. 2020. Future of TVET Teacher. UNESCO-UNEVOC Study. Education 2030. Bonn: UNESCO-UNEVOC. https://www.skillreporter.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Future-of-TVET-Teaching-Pooja-Gianchandani-Gita-Subrahmanyam-UNESCO-UNEVOC-Report-Skill-Development.pdf (accessed October 1, 2024) 15.30.Suche in Google Scholar

VET. 2013. Technical Vocational Education Development Strategy for the Years 2013–2020. Government Decision No. 97. http://lex.justice.md/md/346695/ (accessed November 4, 2022).Suche in Google Scholar

Vodita, Oana, Ecaterina Iosnascu-Cuciuc, and Lilian Hincu. 2022. “Education and Training of Vocational Education and Training (VET): Teachers in the Republic of Moldova.” In Technical and Vocational Teacher Education and Training in International and Development Co-Operation – Models, Approaches and Trends, edited by F. Bünning, G. Spöttl, and H. Stolte, 309–18. Singapore: Springer.10.1007/978-981-16-6474-8_19Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.