Abstract

Research on representation and responsiveness is based on the idea that voters have concerns about certain policy problems and that representatives respond to these concerns with concrete policy outputs, such as laws. In addition, once adopted, this policy output can feed back on voters’ concerns which are then satisfied. Consequently, citizens do not demand more of the respective policy (negative feedback, thermostatic model (Soroka & Wlezien 2010)) or are, in contrast, incited toward demanding even more of the policy (positive feedback, policy overreaction (Maor 2014, Jones et al 2014)). In this research note, I argue that by focussing mainly on such preference-policy linkages, existing research has underestimated the role emotions play in this “chain of responsiveness” (Powell 2004), especially when it comes to protective policies, that is policies that are presented as providing protection to citizens. I propose an amended concept of responsiveness which adds an emotional layer to the existing framework and present an empirical exploration on the emotion-policy link on the micro level using data from the European Social Survey which indicates the fruitfulness to bring in emotions more plainly into the literature on responsiveness.

1 Introduction[1]

Standard models of democratic representation usually conceptualize democratic representation as a principal-agent-relationship with some linkage that relates citizens’ preferences (as the principals) to the actions of the political representatives (as the agents) (e.g. Rohrschneider & Thomassen 2020). How this linkage between citizens and representatives exactly looks like, depends on the theoretical perspective as well as the empirical forms of representation that the authors look at. In their famous 1963 article on the American Congress, for instance, Miller and Stokes (1963) conceptualize a direct linkage between constituencies in electoral districts and their representative in Congress. Theorizing about the role of political parties, Klingemann et al. (1994) see parties and their programs as key transmission belt between citizens and voters – a point that has been further discussed by scholars like Powell (2004), Dalton et al. (2011) or Naurin et al. (2019) and harks back to the responsible party model (APSA 1950).

While these models differ in terms of how they conceptualize the linkage between principals and agents, they nevertheless converge in that they primarily see representation as based on issues – be it by linking specific preferences or general policy mood[2] to policies, by looking at issue-specific electoral pledges or by using party manifestos to measure party positions to voter positions.[3] In this research note, I argue that while much speaks in favour of using issue-linkages as backbone of representation theory (conceptualized as “substantive representation” (Pitkin 1967)), this focus may lead us to overlook situations in which policy does not respond to certain issue preferences, but to more general preoccupations of citizens linked to emotions. My main claim, which I develop theoretically and illustrate empirically, comes down to the idea that citizens’ needs and demands are sometimes linked more strongly to affective states than to actual policy preferences (see also Wenzelburger 2025). Moreover, they can be responded to by different policies – as long as they can be justified as adequate responses to the affective demands by politicians.

The empirical case on which this paper is based are protective policies, that is policies framed as responding to threats, anxieties and insecurity (Albertson & Gadarian 2015) – aspects which are often bundled up and addressed in speeches by politicians. Zooming in on protective policies makes sense, because insecurity has developed into a key characteristic of the current environment of politics (Inglehart 2018, Béland 2020, Starke et al 2024). Moreover, some scholars have argued that in such an era of insecurity emotions are increasingly dominating current politics (Flinders & Hinterleitner 2022, Bonansinga 2022). Hence, for the responsiveness in the case of protective policies, the basic expectation that can be derived from the theory is straightforward: Citizens that experience anxieties linked to insecurity are likely to translate them into a demand for protection by the state – with the concrete policy measures delivering such protection being open for debate (and framing) and possibly reaching from tougher migration laws to measures providing social and economic security. Hence, the basic question this article wants to address comes down to asking to what extent negative affect corresponds with citizens’ demands for protective policies, with protection coming in different policy disguises.

The reminder of this research note is structured as follows: In the next section, starting from the idea of policy responsiveness as backbone of representation, I will discuss how the idea of issue-specific responsiveness, which is at the heart of much of the current empirical research in this tradition, can be complemented by “issue-unspecific” policy responsiveness. I will concretize this idea with “emotional needs” as demands and hypothesize how “protective policies” may be a response to such demands. Section 3 illustrates the relevance of my argument by giving some insights in micro-level data about an emotion-policy link based on data from the European Social Survey. The last section concludes and provides some points of discussion for further research.

2 Policy Responsiveness, Issue Linkages and Beyond

2.1 A Brief Recap on the Insights from the Policy Responsiveness Literature

‘Democratic responsiveness’ is what occurs when the democratic process induces the government to form and implement policies that the citizens want. When the process induces such policies consistently, we consider democracy to be of higher quality. Indeed, responsiveness in this sense is one of the justifications for democracy itself. (Powell 2004, 91)

Democracy as a linkage between preferences of the citizens and policies – as summarized in the quote by Powell above – has been at the centre of an important research agenda studying the quality of democracy. Empirically, responsiveness has often been seen as the core of “substantive representation” (Pitkin 1967) and studied as policy responsiveness, which occurs when a government “adopts policies that are signalled as preferred by citizens” (Manin et al 1999, 9).[4] To empirically test this relationship between public opinion and policy adoption (for an overview, see Burstein 2003, 2010; Wlezien & Soroka 2021), studies have analysed (1) “congruence”, that is whether ideologies or public preferences on certain issues as measured in surveys overlap with policy outputs (Jones & Baumgartner 2004), as well as (2) “responsiveness” which occurs when politicians react (respond) to opinion changes during the policymaking process by adjusting policies in the direction preferred by citizens (Beyer & Hänni 2018, Stimson et al 1995). While studies on congruence often use aggregate measures of positions, such as left-right-scales (Golder & Stramski 2010), an important body of work interested in policy responsiveness emphasizes the need to differentiate between specific policies and issues when studying responsiveness through policy adoption (Rasmussen et al 2019). Scholars in the tradition of the thermostatic model have, for instance, looked into how changes in public opinion on certain policies (such as foreign aid, education, welfare or defence) are reflected in changes in public spending, and vice versa (Wlezien 1995, 2017, Soroka & Wlezien 2010). Similarly, studies based on the analysis of party manifestos have looked for correlations between public opinion, issue emphasis of parties in manifestos, and policy outputs – trying to model the entire democratic linkage from public opinion, political parties and policies (Dalton et al 2011).[5] And as part of the “Comparative Agendas Project”, an international team of political scientists has developed and applied issue-specific codes that enable them to link the content of legislative bills, parliamentary speeches and public opinion in order to see to what extent the public agenda is linked to the political agenda (in parliament) and, eventually, policy outputs (legislation) (Baumgartner et al 2019). The core of the data collection is the detailed coding of issue-specific policy domains, which can then be used to match the dynamics in the public and the political realm.

Finally, an important mostly US-based body of research has followed Stimson’s work on public opinion in Stimson (1991), which argues that a promising way to capture citizens’ preferences is to focus on the policy mood – a general concept that can be related to different policy issues such as economic, cultural or crime-related issues. Stimson describes policy mood as a “shared feelings that move over time and circumstances” but links it to issues, arguing that “publics see every public issue through general dispositions” (Stimson 1991, 20). Hence, scholars from this tradition argue (and empirically find) some sort of “underlying preference for government action” (Wlezien & Soroka 2021), which can be aggregated based on different policy issues (Stimson 2012). Indeed, research finds clear indications of thermostatic responsiveness based linking this policy mood to government activity (Caughey & Warshaw 2017; Erikson et al. 2002; Stimson et al. 1995), although policy preferences do not always move together over time (Wlezien 2004).

Admittedly, this line of research has also not remained unchallenged. Critics have argued that most citizens are politically uninformed, do not care about what is written about certain policy issues in party manifestos and have not much knowledge about which policies have been decided (Jensen & Zohlnhöfer 2020). However, empirical analyses indicate that new information about policy is used even by less political sophisticated citizens to update their political views (Enns & Kellstedt 2008). Moreover, political communication researchers have pointed out that taking policy preferences as starting point of the chain of responsiveness is a heroic assumption, as preferences themselves are malleable and have shown to be influenced by political communication such as framing or priming (Druckman 2014). And similarly, theoretical work on representation has emphasized recursive processes that model the circularity between preference formation and policies (and vice versa) (Mansbridge 2018, Disch, van de Sande & Urbinati 2020). To address this issue, more elaborated perspectives such as the thermostatic model do indeed account for such endogeneity and propose statistical analyses using time lags model policy responsiveness (opinion-to-policy) and public responsiveness (policy-to-opinion) in an integrated framework (Soroka & Wlezien 2010, Esaiasson & Wlezien 2017).

Hence, the upshot of this rich literature is that – holding other important influences on policy-making constant – (1) policy outputs mostly do follow changes in public opinion and that (2) the extent of this responsiveness depends on context such as political institutions or the salience of the issue at stake (Wlezien & Soroka 2012).[6] In most of these studies, though, opinion-policy linkages are modelled as issue- or (area-)specific, differentiating, for instance, between criminal justice, social welfare or foreign policy (see for instance the key monographs by Soroka and Wlezien (2010) or Baumgartner and colleagues (Baumgartner & Jones 1993, Baumgartner et al 2019)), or by a more general aggregation of different issues into a more general indicator of “policy mood” (Stimson et al. 1995).

2.2 Beyond Policy Areas and Issue Linkages

As we have seen, although differences in degree can be observed when it comes to how empirical studies analyse policy responsiveness – e.g. whether they use some aggregation of issues in policy areas (“foreign domains”, “domestic domains”), analyse linkages between explicit and precise issues and policy outputs (“higher taxes”) or aggregate issue preferences up into an indicator of “policy mood” – the empirical backbone of most of the studies remains the general idea of more or less specific issue-related linkages between preferences or opinions on the one and public policies on the other hand. While policy preferences clearly are an important part of democratic representation, some scholars have argued that we may overlook parts of the story when we generally take preferences as starting point. Protective policies are a case in point. In fact, we know from political psychology that while feelings of insecurity produce psychological processes resulting in an increased demand for protection by the state, it very much depends on framing which policies are actually considered as fulfilling this need of protection (Albertson & Gadarian 2015). A good example for such a cross-cutting relationship is for instance the finding that governments use welfare chauvinist social policies to respond mainly to issues of cultural insecurity (i.e. threats to the traditional way of life) and only secondarily to economic and social insecurity (van der Waal et al. 2010). Hence, responsiveness in this case seems to be less preference-related than one going back to subjective feelings that citizens seek to be taken care of by politics.

Theoretically, Albertson and Gadarian argue that the proposed mechanism behind insecurity and threats on the one and the demand for protection on the other hand is linked to emotions, and mainly anxiety (Albertson & Gadarian 2015, 19–26). This general expectation can be traced back to psychological mechanisms from terror management theory (Pyszczynski et al 2015) and insights from research on political conservatism (Jost et al. 2007). And indeed, using experimental evidence on cases such as a (smallpox) epidemic, terrorist attacks, climate change and migration, the study finds evidence that protective policies are indeed supported when people are anxious and fearful – depending on whether a threat is “out there” (i.e. unframed) or framed by political actors. Similarly, researchers working on fear of crime have not only shown that fear is correlated with more punitive attitudes (Singer et al. 2019), but also that people living in generous welfare states are less fearful of crime, probably because the “higher the capacity of the welfare state to cushion social and economic risks, the less existential insecurity should be left to be projected onto crime” (Hummelsheim et al. 2011, 331). Hence, social as well as penal policies seem to be correlated with fear of crime – a finding which is also reflected by the association between economic vulnerability and fear of crime (Vieno et al 2013). Hence, if such affective states generate demand for (protective) policies, research on responsiveness may be missing parts of the story by mainly considering preferences as the starting point.[7]

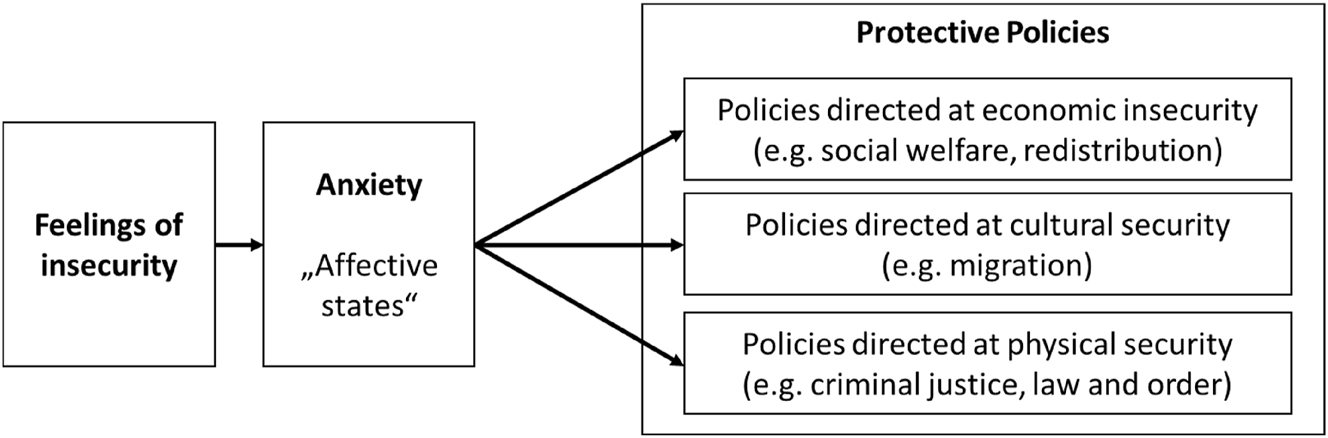

Summarizing these insights from the literature, it seems therefore straightforward that studies of responsiveness would also benefit from reaching beyond linking preferences and policies and include feelings, emotions and affect[8] – especially in cases linked to protection when emotional responsiveness through policy measures in different domains can be expected (see Figure 1). More concretely, I therefore expect that emotions of individuals will be systematically related to policies, in the sense that negative affective states and anxiety will go hand in hand with a demand for more protection (H1). In addition, reflecting the possibility of issue-unspecific responsiveness, I expect that negative affective states and anxiety will lead to an increased demand for protection by the state across different policy domains (H2).[9] Evidently, this does not mean that preferences are irrelevant – they clearly are. I simply argue that responsiveness research needs to be open to the fact that, sometimes, policies are adopted to respond to emotions of citizens, such as anxiety, which in turn can be the result of rather different policy preferences. Interestingly, this idea of subjective feelings, affect and emotions as key ingredients of responsiveness is not too far away from the idea of policy mood in Stimson’s 1991 book on public opinion in America, where he describes it as connoting “shared feelings that move over time and circumstance” (Stimson 1991, 20). However, whereas Stimson – and many other researchers following his work – have looked at preferences as basic entity of responsiveness (be it issue-specific or generalized), I argue that it may actually be worthwhile to look at emotions and affect directly and unrelated to policy preferences.

Summarizing the theoretical argument.

3 Affective States and Demand for Protective Policies: An Illustration using Micro-level Data from European Countries

While some empirical examples have already been given in the conceptual discussion above, this section of the article tries to probe whether individuals’ emotional states may be interrelated with favouring certain policies – as hypothesized above. Arguably, the core idea of our types of responsiveness always involves a linkage between the micro- and the macro-level – and we would therefore need to study whether governments on the macro-level respond to citizen’s affective states – with certain protective policies or, at least, discourse and symbolic action. However, testing these relationships would necessitate data on the aggregate level on protective policies and related public communication, which is not available (the most sophisticated data comes from the Comparative Agenda Project (Baumgartner et al. 2019), which does not include all countries selected here and has no specific code on protective policies). Hence, the following empirical section cannot provide a straightforward test of the model illustrated in Figure 1, but instead stops one step earlier – at the stage of policy demands for certain protective policies (as formulated in H1 and H2). While this is, admittedly, an imperfect solution, I would still argue that an analysis on the micro-level already can give an indication to what extent the proposed relationships between emotions and policies may actually hold. I will develop some ideas about a how to study the actual dynamics laid out in Figure 1 in the concluding section.

3.1 Data and Methods

I explore these relationships using wave 3 and wave 6 of the European Social Survey. I chose these survey waves, because they both include a short version of the widely used PANAS affect-scale, which measures positive and negative affect by asking respondents how they felt during the last weeks (see below for an overview of the data). In order to test the hypotheses above, I chose negative affective states, and anxiety in particular, as key independent variables in my analyses. For the aggregate affective state variable, I follow the re-analysis of the ESS-scales by Sortheix and Weber (2023). They find that five out of six standard negative affect items load on the same dimension and exclude “you felt that everything you did was an effort” from the final measurement model (Sortheix & Weber 2023, 5). The negative affect scale is therefore made up of five indicators. I use the mean of the respective variables, which is the usual procedure in research using these affect scales (Breyer & Bluemke 2016). In addition, I use the variable of “felt anxiety” as an alternative second independent variable, as it taps in specifically on the emotion which is theoretically most relevant to the demand for protection (see the discussion above). As dependent variables, I explore two different policies that related to protection. The first policy is related to economic insecurities and social welfare, namely policies aiming at redistribution of income. In contrast, the second policy is linked much more to cultural insecurities and related anxieties and proposes a harsher stance toward migration. Here, I use two different measures of those dimensions of protection.[10] Table 1 summarizes the variables and respective measurements.

Variables and data.

| Variable | Measurement and source | |

|---|---|---|

| Independent variables (negative affect measures) | Negative affect (mean) | Mean of five indicators: Please tell me how much of the time during the past week

|

| Anxiety | Please tell me how much of the time during the past week … you felt anxious (item 4). Scale: 1 [(almost)none of the time] to 4 [(almost) all of the time]) |

|

| Dependent variables (policy items) | Redistribution of income | Government should reduce income levels Scale: 1 [agree strongly] to 5 [disagree strongly] |

| Migration and living in country | Is country made a worse or a better place to live by people coming to live where from other countries? Scale: 0 [worse] to 10 [better] |

|

| Migration and culture | Would you say that [country]’s cultural life is generally undermined or enriched by people coming to live here from other countries? Scale: 0 [bad] to 10 [good] |

|

| Controls | Education | Years of full time education completed |

| Gender | Binary gender category Scale: 1 [male], 2 [female] |

|

| Age | Age in years | |

| Income | Feeling about household’s income Scale: 1 [living comfortably on present income] to 4 [living very difficult on present income] |

|

| Left right position | Self-placement on left-right scale Scale: 0 [left] to 10 [right] |

-

Some of the original items of the dependent variables have been rescaled. Scales in italic.

To analyse the data, I present descriptive statistics and results of regression analyses. The regressions also include a number of confounders, namely socio-demographics and variables related to economic status (see Table 1). Although the dependent variables are, strictly speaking, ordinally scaled (4 point or 10 point likert scales), I present results from OLS regressions for ease of interpretation. Estimations from ordinal logit models do not deviate substantially from the OLS results. As I am mainly interested in the associations on the individual level independently from cross-country variance or differences over time, I estimate a two-way fixed effects model that soaks up all variance between countries and waves. I estimate robust standard errors.

3.2 Empirical Results

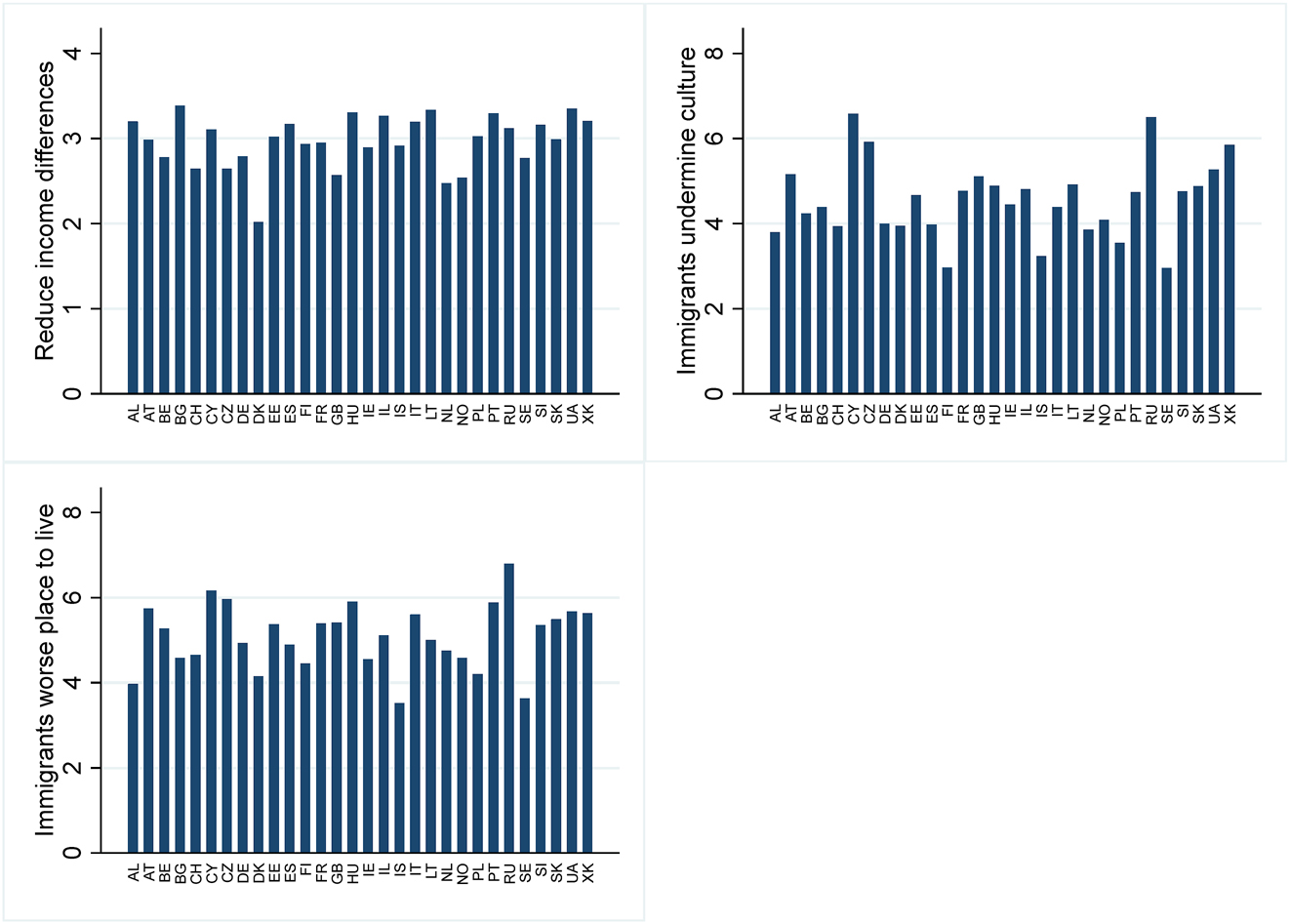

To get a sense of the data and the Figure 2 presents the three dependent variables linked to protective policies as country-wise arithmetic means for both rounds of the ESS analysed here (ESS round 3 and 6). While it shows considerable cross-country variance in all three cases, the graph also indicates that the differences between nation-states seem to be a bit more pronounced for attitudes toward migration, that is policies that can be interpreted as protecting from cultural insecurity. Although the aggregated means do not show the variance on the individual level within countries that we are most interested in, the graph nevertheless already indicates that citizens’ demands of protection by the state do vary considerably in Europe.

Attitudes toward protective policies in 30 European countries.

Moving on to bivariate associations on the individual level, Table 2 displays simple bivariate correlations between our dependent variables, that is how strongly respondents in the respective countries demand protection from the state in the case of economic insecurity and cultural insecurity on the one hand, and the emotional states that the respective persons feel when asked in the survey. Although correlation coefficients are not overwhelming in size, the pattern of association is clear-cut: Negative affect in general and anxiety in particular are positively correlated with demands for protection on both policies analysed here, namely policies directed at economic insecurity and cultural insecurity. This is at least a first indication that emotional states are linked to a general demand for protection, independent of the actual policy domain.

Bivariate correlations negative affect and policy items.

| Negative affect | Anxiety | |

|---|---|---|

| Policies to reduce income differences | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| Cultural life undermined by immigrants | 0.15 | 0.12 |

| Immigrants make country worse place to live | 0.15 | 0.12 |

-

All correlations are significant at p < 0.01.

Importantly, the regression analysis confirms the results of the bivariate correlational pattern. The models presented in Table 3 are structured by dependent variable and consist of three models per dependent variable, which include, first, the negative affect scale and, second, the specific item that taps into feelings of anxiety. From the table transpires that even when controlling for confounders that may be related to both the dependent variable and the independent variables, such as the left-right position, income, age, education level and gender, I still find a pattern that points to an association between negative affect on the one and individual demands for protective policies on the other hand. The signs of the coefficients are similar to what I found in bivariate correlation, indicating that people in a negative affective state and those feeling more anxious are in favour of more protection (more redistribution, less migration). However, it is important to note that the associations are more significant and robust in the case of protection of cultural insecurity than for policies aimed at protection of economic insecurity. Hence, anxious people seem to be slightly more inclined to ask for protection of a country’s culture and their way of life than for reducing income differences. Still, for anxiety, the coefficient meets the lowest threshold of significance even for economic insecurity (Model 2 in Table 3).

Results from regression analysis.

| Policies to reduce income differences | Cultural life undermined by immigrants | Immigrants country worse place to live | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Negative affect scale | 0.0028 | 0.18** | 0.16** | |||

| (0.43) | (10.71) | (9.68) | ||||

| Feelings of anxiety | 0.0073+ | 0.10** | 0.092** | |||

| (1.80) | (9.29) | (9.00) | ||||

| Age | 0.0039** | 0.0038** | 0.0069** | 0.0074** | 0.0072** | 0.0074** |

| (20.03) | (19.92) | (14.29) | (15.32) | (16.05) | (16.72) | |

| Life v difficult on present income | 0.16** | 0.15** | 0.22** | 0.24** | 0.26** | 0.27** |

| (33.70) | (34.09) | (18.50) | (20.12) | (22.96) | (24.51) | |

| Education | −0.018** | −0.018** | −0.11** | −0.11** | −0.080** | −0.080** |

| (−19.05) | (−18.75) | (−48.14) | (−48.42) | (−37.00) | (−37.23) | |

| Gender | 0.11** | 0.10** | −0.12** | −0.11** | −0.046** | −0.042** |

| (15.24) | (15.09) | (−6.86) | (−6.41) | (−2.95) | (−2.67) | |

| Left-right scale | −0.077** | −0.074** | 0.10** | 0.098** | 0.075** | 0.067** |

| (−47.86) | (−47.36) | (24.21) | (23.08) | (18.72) | (16.71) | |

| Constant | 3.16** | 2.96** | 3.49** | 3.58** | 5.10** | 5.20** |

| (78.71) | (67.06) | (35.26) | (36.56) | (48.50) | (49.99) | |

|

|

||||||

| N | 78,510 | 79,904 | 76,893 | 78,226 | 76,589 | 77,891 |

| R 2 | 0.149 | 0.148 | 0.170 | 0.167 | 0.136 | 0.135 |

-

Estimation with robust standard errors. All models include country and period (wave) fixed effects. t statistics in parentheses: + p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Turning to the control variables it is also important to note that especially high economic insecurity and low education (as well as high age) are significantly (and highly) correlated to both protective policies (i.e. all three dependent variables) – a pattern in line with research on welfare chauvinism (Careja & Harris 2022). In contrast, gender and attitudes on the general left-right scale differ between protective policies related to economic and cultural insecurity. This finding calls for more research into the relevance of economic hardship on anxieties that may feed into demand for protection – relationships that are difficult to uncover with the limited cross-sectional data at hand.

In sum, these results indicate that emotions and affect seem to be associated on the individual level, with people experiencing negative emotions being more inclined to support policies that provide more protection. Hence, the first hypothesis formulated above is supported by the data. Moreover, with regard to our second hypothesis, the regression estimations also point to the fact that feelings of anxiety push people to demand protection in quite different policy domains – such as economic policies and migration policies (confirming H2). While it is true that these results do not provide direct evidence for the idea of emotional responsiveness in the sense that politicians respond to affective states with different policies (or discourses), the regression estimates can be read at least as a first indication suggesting that different protective policies may indeed respond to one and the same affective states. This points – on a conceptual level – to the possibility that responsiveness does not only relate to policy preferences, but to affective states and emotions.

4 Conclusions

In this article, I have argued that most existing empirical research on substantive representation and policy responsiveness has focussed on the linkage between citizen’s policy preferences and policy outputs when conceptualizing responsiveness. This assumes that politicians answer to citizens’ demands for more or less policies in a certain area (e.g. welfare, foreign aid) or some aggregated policy mood related to the demand for government action with the respective policy outputs. While I concede that this perspective has resulted in a very fruitful research strand mostly confirming that policy responsiveness does exist, I have argued theoretically that in some cases, such linkages between preferences and policies may actually not be the only way to think about representation and responsiveness. Taking the case of protective policies as an example, policies that are framed by politicians as responding to rising insecurities and, relatedly, to anxiety and threats felt by citizens, this paper has argued that studying responsiveness to emotions and affective states of citizens can be a fruitful perspective to be studied by future research. More concretely: If people feel anxious, they demand protection by the state – and by which policy measures this protection is delivered may actually be open to debate (and strategic framing).[11] Opening up our idea of responsiveness from thinking in policies and preferences to include emotions as starting points of responsiveness, allows us to include emotional aspects and affect more plainly into thinking about representation (Wenzelburger 2025).[12]

Empirically, this article has provided a first indication that the conceptual arguments have some face validity. Using data from the ESS, I have shown that a negative affective state and feelings of anxiety are indeed related with demands for more protection by the state – together with important socio-economic correlates such as economic hardship or low education. Importantly, this demand expands to different protective policies – economic redistribution and protection of culture against immigrants in this case. People that are more anxious prefer more redistribution and they also want their culture to be protected. While this is no direct test of the linkage between emotions and policies – as I only analyse demand for protection on the individual level –, the results nevertheless indicate that if such demands are sensed by politicians, emotional responsiveness may result.

Clearly, the empirical analysis is not more than a first illustration of possible interrelationships between emotions and policies and it clearly shows that more data is badly needed if we want to systematically study the three additional types of responsiveness. To do so, we would need comparable measures of emotions of citizens, reaching beyond the affect scales used in this paper. Advances in political psychology indicate that scales of discrete emotions may be a promising route forward, as they can also be linked to both general models such as the affective intelligence theory (Marcus 2002) and the policy process (Pierce 2021). Moreover, on the policy side, we need measurements of political communication that enables us to study to what extent politicians respond emotionally through rhetoric and/or visuals. Recent advances in automated text analysis seem to indicate that generating comparable data on a large scale may be within reach in the next years or so. Only such efforts would enable us to study symbolic and emotional responsiveness empirically, as proposed in the conceptual part of this contribution. Finally, a big leap forward would also be to be able to measure emotional intensity and emotional acceleration (Dietrich et al. 2019, Asker & Dinas 2019) as they may be used strategically by emotional policy entrepreneurs to stir up emotions in the public in the first place (Maor 2024).

This brings us back to an important question (and challenge) for future research – namely, the endogeneity of emotions. While it is true that the mainstream research on policy responsiveness has already been criticized for taking policy preferences as exogenous starting point (Druckman 2014) – a critique that has been solved by the thermostatic model which explicitly models feedback processes –, the issue of endogeneity will even be more critical for analysing emotional responsiveness. Indeed, studying emotional responsiveness needs to be particularly open to feedback and reverse directions of responsiveness, namely that emotions as well as preferences may be an outcome of policies and/or political communication. Policy researchers have shown numerous times that framing and rhetoric are an important strategy during problem definition and agenda setting – including emotions (Kuhlmann & Blum 2021; Maor 2016, 2024). Hence, while adding an emotional layer to the traditional model of responsiveness may help us better understand the interrelationships between citizens and politics, it does not release us from taking the recursive side of responsiveness into account.

Funding source: European Commission, Horizon Europe

Award Identifier / Grant number: Project 101132433

-

Research funding: This work was supported by European Commission, Horizon Europe under grant Project 101132433.

References

Albertson, Bethany, and Shana Kushner Gadarian. 2015. Anxious Politics. Democratic Citizenship in a Threatening World. New York: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139963107Suche in Google Scholar

APSA. 1950. “Towards a More Responsible Two-Party System: A Report on the Committee on Political Parties.” American Political Science Review 44 (3): supplement.Suche in Google Scholar

Asker, David, and Elias Dinas. 2019. “Thinking Fast and Furious: Emotional Intensity and Opinion Polarization in Online Media.” Public Opinion Quarterly 83 (3): 487–509. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz042.Suche in Google Scholar

Bartels, Larry M. 2008. Unequal Democracy : The Political Economy of the New Gilded Age. New York: Russell Sage.Suche in Google Scholar

Baumgartner, Frank R., Christian Breunig, and Emiliano Grossman, eds. 2019. Comparative Policy Agendas. Theory, Tools, Data, 1st ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780198835332.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Baumgartner, Frank, and Bryan D. Jones. 1993. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Béland, Daniel. 2020. “Right-Wing Populism and the Politics of Insecurity: How President Trump Frames Migrants as Collective Threats.” Political Studies Review 18 (2): 162–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929919865131.Suche in Google Scholar

Beyer, Daniela, and Miriam Hänni. 2018. “Two Sides of the Same Coin? Congruence and Responsiveness as Representative Democracy’s Currencies.” Policy Studies Journal 46 (S1): S13–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12251.Suche in Google Scholar

Bonansinga, Donatella. 2022. “Insecurity Narratives and Implicit Emotional Appeals in French Competing Populisms.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 35 (1): 86–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2021.1964349.Suche in Google Scholar

Breyer, Bianka, and Matthias Bluemke. 2016. “Deutsche Version Der Positive and Negative Affect Schedule PANAS (GESIS Panel).” Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS) (242). https://doi.org/10.6102/zis242.Suche in Google Scholar

Burstein, P. 2003. “The Impact of Public Opinion on Public Policy: A Review and an Agenda.” Political Research Quarterly 56 (1): 29–40, https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290305600103.Suche in Google Scholar

Burstein, P. 2010. “Public Opinion, Public Policy, and Democracy.” In Handbook of Politics: State and Society in Global Perspective, edited by K. T. Leicht, and J. C. Jenkins, 63–79. New York: Springer.10.1007/978-0-387-68930-2_4Suche in Google Scholar

Careja, R., and E. Harris. 2022. “Thirty Years of Welfare Chauvinism Research: Findings and Challenges.” Journal of European Social Policy 32 (2): 212–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/09589287211068796.Suche in Google Scholar

Caughey, D., and C. Warshaw. 2017. “Policy Preferences and Policy Change: Dynamic Responsiveness in the American States, 1936–2014.” American Political Science Review 112 (2): 249–66. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000533.Suche in Google Scholar

Dalton, Russell J., David M. Farrell, and Ian McAllister. 2011. Political Parties and Democratic Linkage: How Parties Organize Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199599356.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Dietrich, Bryce J., Matthew Hayes, and Diana Z. O’Brien. 2019. “Pitch Perfect: Vocal Pitch and the Emotional Intensity of Congressional Speech.” American Political Science Review 113 (4): 941–62. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000467.Suche in Google Scholar

Disch, Lisa, Mathijs van de Sande, and Nadia Urbinati, eds. 2020. The Constructivist Turn in Political Representation. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.10.3366/edinburgh/9781474442602.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Druckman, James N. 2014. “Pathologies of Studying Public Opinion, Political Communication, and Democratic Responsiveness.” Political Communication 31 (3): 467–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2013.852643.Suche in Google Scholar

Elsässer, Lea, Svenja Hense, and Armin Schäfer. 2021. “Not Just Money: Unequal Responsiveness in Egalitarian Democracies.” Journal of European Public Policy 28 (12): 1890–908, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1801804.Suche in Google Scholar

Enns, Peter K. 2022. “Reconsidering Representation: How the Same Data can Produce Divergent Conclusions About the Quality of Democratic Responsiveness in the United States.” In Contested Representation: Challenges, Shortcomings and Reforms, edited by Claudia Landwehr, Thomas Saalfeld, and Armin Schäfer, 103–28. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781009267694.009Suche in Google Scholar

Enns, Peter K., and Paul M. Kellstedt. 2008. “Policy Mood and Political Sophistication: Why everybody Moves Mood.” British Journal of Political Science 38 (3): 433–54. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000227.Suche in Google Scholar

Erikson, R. S., M. MacKuen, and James A. Stimson. 2002. The Macro Polity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139086912Suche in Google Scholar

Esaiasson, Peter, and Christopher Wlezien. 2017. “Advances in the Study of Democratic Responsiveness: An Introduction.” Comparative Political Studies 50 (6): 699–710. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414016633226.Suche in Google Scholar

Flinders, Matthew, and Markus Hinterleitner. 2022. “Party Politics Vs. Grievance Politics: Competing Modes of Representative Democracy.” Society 59 (6): 672–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-022-00686-z.Suche in Google Scholar

Geise, Stephanie, Katharina Maubach, and Alena Boettcher Eli. 2024. “Picture me in Person: Personalization and Emotionalization as Political Campaign Strategies on Social Media in the German Federal Election Period 2021.” New Media & Society 7: 3745–69, https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231224031.Suche in Google Scholar

Gilens, Martin. 2005. “Inequality and Democratic Responsiveness.” Public Opinion Quarterly 69 (5): 778–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfi058.Suche in Google Scholar

Golder, Matt, and Jacek Stramski. 2010. “Ideological Congruence and Electoral Institutions.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (1): 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00420.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Hoggett, Paul, and Simon Thompson. 2012. “Introduction.” In Politics and the Emotions: The Affective Turn in Contemporary Political Studies, edited by Paul Hoggett, and Simon Thompson, 1–19. New York and London: Continuum International.Suche in Google Scholar

Hummelsheim, Dina, Helmut Hirtenlehner, Jonathan Jackson, and Oberwittler Dietrich. 2011. “Social Insecurities and Fear of Crime: A Cross-National Study on the Impact of Welfare State Policies on crime-related Anxieties.” European Sociological Review 27 (3): 327–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcq010.Suche in Google Scholar

Ibenskas, Raimondas, and Jonathan Polk. 2022. “Congruence and Party Responsiveness in Western Europe in the 21st Century.” West European Politics 45 (2): 201–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2020.1859756.Suche in Google Scholar

Inglehart, Ronald. 2018. “The Age of Insecurity: Can Democracy save Itself.” Foreign Affairs 97 (3): 20–8.Suche in Google Scholar

Jäckle, S., T. Metz, G. Wenzelburger, and P. D. König. 2019. “A Catwalk to Congress? Appearance-based Effects in the Elections to the U.S. House of Representatives 2016.” American Politics Research 48 (4): 427–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X19875710.Suche in Google Scholar

Jensen, Carsten, and Reimut Zohlnhöfer. 2020. “Policy Knowledge Among ‘Elite Citizens’.” European Policy Analysis 6 (1): 10–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1076.Suche in Google Scholar

Jones, Bryan D., and Frank R. Baumgartner. 2004. “Representation and Agenda Setting.” Policy Studies Journal 32 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0190-292X.2004.00050.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Jones, Bryan D., F. Thomas Herschel, and Michelle Wolfe. 2014. “Policy Bubbles.” Policy Studies Journal 42 (1): 146–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12046.Suche in Google Scholar

Jost, John T., Jaime L. Napier, Hulda Thorisdottir, Samuel D. Gosling, Tibor P. Palfai, and Ostafin. Brian. 2007. “Are Needs to Manage Uncertainty and Threat Associated with Political Conservatism or Ideological Extremity?” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 33 (7): 989–1007. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207301028.Suche in Google Scholar

Klingemann, Hans-Dieter, Richard I. Hofferbert, and Ian Budge. 1994. Parties, Policies, and Democracy. Boulder/San Francisco/Oxford: Westview.Suche in Google Scholar

Kuhlmann, Johanna, and Sonja Blum. 2021. “Narrative Plots for Regulatory, Distributive, and Redistributive Policies.” European Policy Analysis 7 (S2): 276–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1127.Suche in Google Scholar

Manin, Bernard, Adam Przeworski, and Susan C. Stokes. 1999. “Introduction.” In Democracy, Accountability, and Representation, edited by Adam Przeworski, Susan C. Stokes, and Bernard Manin, 1–28. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139175104.001Suche in Google Scholar

Mansbridge, Jane. 2018. “Recursive Representation.” In Creating Political Presence: The New Politics of Democratic Representation, edited by Dario Castiglione, and Johannes Pollak, 298–338. Chicago: Chicago University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Maor, Moshe. 2014. “Policy Bubbles: Policy Overreaction and Positive Feedback.” Governance 27 (3): 469–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12048.Suche in Google Scholar

Maor, Moshe. 2016. “Emotion-Driven Negative Policy Bubbles.” Policy Sciences 49 (2): 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-015-9228-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Maor, Moshe. 2024. “An Emotional Perspective on the Multiple Streams Framework.” Policy Studies Journal 52 (4): 925–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12568.Suche in Google Scholar

Marcus, George. 2002. The Sentimental Citizen: Emotion in Democratic Politics. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Miller, Warren E., and Donald E. Stokes. 1963. “Constituency Influence in Congress.” American Political Science Review 57 (1): 45–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/1952717.Suche in Google Scholar

Naurin, Elin, Terry J. Royed, and Robert Thomson. 2019. Party Mandates and Democracy. Making, Breaking, and Keeping Election Pledges in Twelve Countries, New Comparative Politics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.10.3998/mpub.9796088Suche in Google Scholar

Pierce, Jonathan J. 2021. “Emotions and the Policy Process: Enthusiasm, Anger and Fear.” Policy & Politics 49 (4): 595–614. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557321X16304447582668.Suche in Google Scholar

Pitkin, Hanna F. 1967. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Powell, G. Bingham. 2004. “The Chain of Responsiveness.” Journal of Democracy 15 (4): 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2004.0070.Suche in Google Scholar

Pyszczynski, Tom, Sheldon Solomon, and Jeff Greenberg. 2015. “Chapter One - Thirty Years of Terror Management Theory: From Genesis to Revelation.” In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, edited by James M. Olson, and Mark P. Zanna, 1–70. Amsterdam: Academic Press.10.1016/bs.aesp.2015.03.001Suche in Google Scholar

Rasmussen, Anne, Stefanie Reher, and Dimiter Toshkov. 2019. “The opinion-policy Nexus in Europe and the Role of Political Institutions.” European Journal of Political Research 58 (2): 412–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12286.Suche in Google Scholar

Rohrschneider, Robert, and Jacques Thomassen. 2020. “Introduction.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Representation in Liberal Democracies, edited by Robert Rohrschneider, and Jacques Thomassen, 1–14. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198825081.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Schumacher, Gijs. 2024. “Affective Representation: Capturing Preferences for Emotions of Dutch and American Voters.” PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ebsw7.Suche in Google Scholar

Singer, Alexa J., Cecilia Chouhy, Peter S. Lehmann, Jessica N. Stevens, and Marc Gertz. 2019. “Economic Anxieties, Fear of Crime, and Punitive Attitudes in Latin America.” Punishment & Society 22 (2): 181–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474519873659.Suche in Google Scholar

Soroka, Stuart N., and Christopher Wlezien. 2010. Degrees of Democracy: Politics, Public Opinion, and Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511804908Suche in Google Scholar

Sortheix, Florencia M., and Wiebke Weber. 2023. “Comparability and Reliability of the Positive and Negative Affect Scales in the European Social Survey.” Frontiers in Psychology 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1034423.Suche in Google Scholar

Starke, Peter, Laust Lund Elbek, and Georg Wenzelburger, eds. 2024. Unequal Security Welfare, Crime and Social Inequality. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003462132Suche in Google Scholar

Stimson, J. A. 1991. Public Opinion in America: Moods, Cycles, and Swings. Boulder: Westview Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Stimson, J. A. 2012. “On the Meaning & Measurement of Mood.” Dædalus 141 (4): 23–34.10.1162/DAED_a_00171Suche in Google Scholar

Stimson, James A., Michael B. Mackuen, and Robert S. Erikson. 1995. “Dynamic Representation.” American Political Science Review 89 (3): 543–65. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082973.Suche in Google Scholar

van der Waal, Jeroen, Peter Achterberg, Dick Houtman, Willem de Koster, and Katerina Manevska. 2010. “Some are More Equal than Others: Economic Egalitarianism and Welfare Chauvinism in the Netherlands.” Journal of European Social Policy 20 (4): 350–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928710374376.Suche in Google Scholar

Vieno, Alessio, Michele Roccato, and Silvia Russo. 2013. “Is Fear of Crime Mainly Social and Economic Insecurity in Disguise? A Multilevel Multinational Analysis.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 23 (6): 519–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2150.Suche in Google Scholar

Wenzelburger, Georg. 2025. “Emotional Responsiveness in an Age of Insecurity. A Conceptual Proposal and a Research Agenda.” Representation. Journal of Representative Democracy online first, https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2025.2541609.Suche in Google Scholar

Wlezien, Christopher. 1995. “The Public as Thermostat: Dynamics of Preferences for Spending.” American Journal of Political Science 39 (4): 981–1000. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111666.Suche in Google Scholar

Wlezien, C. 2004. “Patterns of Representation: Dynamics of Public Preferences and Policy.” The Journal of Politics 66 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-2508.2004.00139.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Wlezien, Christopher. 2017. “Public Opinion and Policy Representation: On Conceptualization, Measurement, and Interpretation.” Policy Studies Journal 45 (4): 561–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12190.Suche in Google Scholar

Wlezien, Christopher, and Stuart N. Soroka. 2012. “Political Institutions and the Opinion–Policy Link.” West European Politics 35 (6): 1407–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.713752.Suche in Google Scholar

Wlezien, C., and S. N. Soroka. 2021. Public Opinion and Public Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editors Note

- Editors’ Note

- Special Issue: Emotional Dynamics of Politics and Policymaking; Guest Editors: Georg Wenzelburger and Beatriz Carbone

- Bringing Emotions into the Study of Responsiveness: The Case of Protective Policies

- Emotional Reactions to Protective Policies on the Political Spectrum

- Regular Articles

- Determinants of Political Instability in ECOWAS (1991–2022)

- The Impact of International Remittances on Public Debt Sustainability in Kerala: Evidence from the FMOLS Approach

- Bayesian Analysis of Tuberculosis Cases in Bolgatanga Municipality, Ghana–West Africa

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editors Note

- Editors’ Note

- Special Issue: Emotional Dynamics of Politics and Policymaking; Guest Editors: Georg Wenzelburger and Beatriz Carbone

- Bringing Emotions into the Study of Responsiveness: The Case of Protective Policies

- Emotional Reactions to Protective Policies on the Political Spectrum

- Regular Articles

- Determinants of Political Instability in ECOWAS (1991–2022)

- The Impact of International Remittances on Public Debt Sustainability in Kerala: Evidence from the FMOLS Approach

- Bayesian Analysis of Tuberculosis Cases in Bolgatanga Municipality, Ghana–West Africa