Abstract

For the past decades, income inequality has been on the rise, and so is the frequency of its mentions in recent speeches by central bankers. With the heightened importance of the topic, this research aims to study the impact of monetary policy on income inequality. The study used dynamic models for the analysis, namely; the Error-correction Model (ECM) and the Auto-regressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model to determine the relationship in both the short- and long-run. The data used were the top 10% income share and the short-term interest rate. Our main hypothesis is that changes in the short-term interest rate have a significant impact on the top 10% income share. We draw time-series evidence from a sample of nine economies at different stages of development: United States, United Kingdom, Russia, Germany, France, Greece, China, South Africa and Chile. The findings support the hypothesis with interestingly varying effects across our sample. These results provide important implications that can contribute in bettering policy setting and add to the discussion of the role of central banks in reducing income inequality.

Appendix

A Review of empirical studies on monetary policy and income inequality.

| Study | Country | Period | Method | Monetary policy change | Impact on inequality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contractionary monetary policy increases income inequality | ||||||

| Coibion et al. (2017) | US | 1980–2008 | Local projections | Contractionary | Increases inequality | |

| Guerello (2017) | Euro area | 2001–2015 | VAR | Expansionary and QE | Decreases inequality | |

| Mumtaz and Theophilopoulou (2017) | U.K. | 1969–2012 | Structural VAR | Contractionary | Increases inequality | |

| Furceri, Loungani, and Zdzienicka (2018) | Thirty two advanced and emerging economies | 1990–2013 | IRF from local projections | Contractionary | Increases inequality | |

| Casiraghi et al. (2018) | Italy | 2011–2013 | Micro-simulation | QE/UMP | Decreases inequality | |

| Lenza and Slacalek (2018) | France, Germany, Italy, and Spain | 1999Q1–2016Q4 | BVAR and micro-simulation | QE/UMP | Decreases inequality | |

| Contractionary monetary policy decreases income inequality | ||||||

| Saiki and Frost (2014) | Japan | 2008Q4–2013Q3 | VAR | UMP | Increases inequality | |

| Villarreal (2014) | Mexico | 2003–2012 | Local projections | Contractionary | Decreases inequality | |

| O’Farrell, Rawdanowicz, and Inaba (2017) | Eight OECD countries | 2007–2012 | Micro-simulation | Expansionary | Decrease in U.S., Canada, and The Netherlands. Increase in European economies. |

|

| Davtyan (2017) | US | 1983–2012 | VECM | Contractionary | Decreases inequality | |

| Inui, Sudou, and Yamada (2017) | Japan | 1981–2008 | Local projections | Expansionary | Increases inequality | |

| El Herradi and Leroy (2019) | Twelve advanced economies | 1920–2015 | Panel VAR and a single-equation model with local projections | Expansionary | Increases inequality | |

| Cloyne, Ferreira, and Surico (2020) | U.S. and U.K. | U.S.: 1981–2007 U.K.: 1975–2007 | Romer and Romer (2004) procedure | Expansionary | Increases inequality | |

| Dolado, Motyovszki, and Pappa (2021) | U.S. | 1979M1–2016M6 | NK-SAM frictions | Expansionary | Increases inequality | |

Data sample (maximum no. of years obtained).

| Country | Short-term interest rate | Top 10% income share |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 1971Q1–2014Q1 | 1971Q1–2014Q1 |

| United Kingdom | 1986Q1–2016Q1 | 1986Q1–2016Q1 |

| Germany | 1980Q1–2016Q1 | 1980Q1–2016Q1 |

| France | 1980Q1–2016Q1 | 1980Q1–2014Q1 |

| Russia | 1997Q1–2015Q1 | 1997Q1–2015Q1 |

| China | 1997Q3–2015Q1 | 2000Q1–2015Q1 |

| Greece | 1994Q2–2016Q1 | 1994Q2–2016Q1 |

| Chile | 2004Q1–2015Q1 | 2004Q1–2015Q1 |

| South Africa | 1990Q1–2017Q1 | 1990Q1–2017Q1 |

ECM results.

| Country | United States | United Kingdom | France | Russia | South Africa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample (adjusted for lags) |

1983Q2–2014Q1 (124 obs.) |

1988Q4–2016Q1 (110 obs.) |

1980Q2–2014Q1 (136 obs.) |

1999Q4–2015Q1 (62 obs.) |

1998Q2–2017Q1 (76 obs.) |

|

Dependent variable

|

∆ TOP10

t

|

∆ TOP10

t

|

∆ TOP10

t

|

∆ TOP10

t

|

∆ TOP10

t

|

| C | 0.003484 (0.000626) | – | – | – | – |

| ∆ TOP10t−1 | 3.069507 (0.027505) | 2.850251 (0.077547) | 2.687615 (0.048233) | 2.216673 (0.044591) | 2.607693 (0.100118) |

| ∆ TOP10t − 2 | −3.507040 (0.066480) | −3.091203 (0.169356) | −2.758519 (0.095373) | −1.679066 (0.101785) | −2.683514 (0.196039) |

| ∆ TOP10t − 3 | 1.780913 (0.073060) | 1.343358 (0.125373) | 1.185464 (0.093372) | 0.315829 (0.108222) | 1.273684 (0.144435) |

| ∆ TOP10t − 4 | −1.416347 (0.066476) | −1.027340 (0.086095) | −0.844045 (0.110127) | −0.924713 (0.109331) | −1.046205 (0.144255) |

| ∆ TOP10t − 5 | 3.167672 (0.077325) | 2.731838 (0.188359) | 1.971114 (0.159059) | 2.264273 (0.129471) | 2.272839 (0.360903) |

| ∆ TOP10t − 6 | −3.553632 (0.086904) | −2.996910 (0.219878) | −2.025221 (0.156287) | −1.521462 (0.080852) | −2.321162 (0.368091) |

| ∆ TOP10t − 7 | 1.744711 (0.066798) | 1.206523 (0.117157) | 0.779942 (0.065758) | – | 0.936600 (0.146428) |

| ∆ TOP10t − 8 | −0.314812 (0.024782) | – | – | – | – |

| ∆ TOP10t − 9 | – | – | – | 0.561536 (0.040360) | – |

| ∆ TOP10t−10 | – | −0.077403 (0.019266) | −0.030570 (0.009727) | −0.342708 (0.031460) | −0.052637 (0.015793) |

| ∆ INTQt | – | −0.006064 (0.002488) | −0.001521 (0.000546) | −0.003683 (0.001055) | −0.005516 (0.002427) |

| ∆ INTQt−1 | – | – | – | – | – |

| ∆ INTQt − 2 | – | – | – | – | – |

| ∆ INTQt − 3 | – | – | – | – | – |

| ∆ INTQt − 4 | 0.004123es (0.001333) | 0.005475 (0.002181) | – | – | – |

| ∆ INTQt − 5 | – | – | −0.003070 (0.000980) | – | – |

| ∆ INTQt − 6 | – | – | – | – | – |

| ∆ INTQt − 7 | – | – | – | – | – |

| ∆ INTQt − 8 | – | – | – | – | – |

| ∆ INTQt − 9 | – | – | – | – | – |

| ∆ INTQt−10 | – | – | – | – | – |

| ECTt−1 | −0.001209 (0.000378) | −0.006665 (0.003142) | −0.005405 (0.001560) | −0.010685 (0.002640) | −0.020039 (0.005204) |

| Dummy (structural break) | – | 0.099635 (0.010137) | – | – | – |

| Dummy (positive outliers) | 0.045437 (0.002122) | – | 0.032248 (0.006218) | 0.068294 (0.004460) | – |

| Dummy (negative outliers) | −0.036881 (0.003007) | – | −0.024497 (0.004016) | −0.069292 (0.010583) | – |

| R 2 | 0.999428 | 0.996525 | 0.997652 | 0.998346 | 0.995790 |

| Adjusted R 2 | 0.999366 | 0.996134 | 0.997423 | 0.997982 | 0.995216 |

| DW statistic | 1.717920 | 1.932719 | 1.722462 | 1.775729 | 2.038342 |

| S.E. of regression | 0.004759 | 0.019425 | 0.007491 | 0.021650 | 0.021622 |

| LR coefficient | −0.972296 | −0.298378 | −0.282019 | −0.153883 | −0.271646 |

-

*All variables included are statistically significant at 5% and all models were checked for autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity; es, exponential smoothing; – = does not apply; () includes standard error of the coefficients.

ARDL results.

| Country | Germany | Chile | China | Greece | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample (adjusted for lags) | 1982Q4–2016Q1 (134 obs.) | 2006Q1–2013Q4 (32 obs.) | 2001Q1–2015Q1 (57 obs.) | 1996Q4–2016Q1 (78 obs.) | ||

| Dependent variable | ∆ TOP10t | TOP10t | TOP10t | TOP10t | ||

| C | 0.073485 (0.013304) | 2.788105 (0.718769) | 0.477802 (0.176245) | 0.110691 (0.035428) | ||

| ∆ TOP10t − 1 | TOP10t − 1 | 2.854849 (0.045755) | −0.002075 (0.000385) | 3.311579 (0.106029) | 3.184963 (0.099578) | 3.834818 (0.095365) |

| TOP10t − 2 | −3.278517d (0.118984) | −4.588927 (0.296774) | −4.161875 (0.266475) | −5.945079 (0.290375) | ||

| TOP10t − 3 | 1.854910d (0.148515) | 3.244637 (0.318631) | 2.774067 (0.267643) | 4.609347 (0.351702) | ||

| TOP10t − 4 | −1.370045d (0.132456) | −1.969754 (0.262054) | −1.810678 (0.243627) | −2.588678 (0.216820) | ||

| TOP10t − 5 | 2.430210d (0.183737) | 2.923204 (0.678437) | 2.949491 (0.491562) | 3.552954 (0.334263) | ||

| TOP10t − 6 | −2.473322d (0.171131) | −3.841791 (0.812115) | −3.648765 (0.556677) | −5.197256 (0.541891) | ||

| TOP10t − 7 | 1.012991d (0.072736) | 2.578326 (0.496640) | 2.284748 (0.337455) | 3.975559 (0.441095) | ||

| TOP10t − 8 | – | −0.709429 (0.132110) | −0.583060 (0.090101) | −1.320391 (0.166938) | ||

| TOP10t − 9 | – | – | – | – | ||

| TOP10t − 10 | −0.070621d (0.008695) | – | – | 0.075064 (0.016402) | ||

| INTQt | – | – | −0.028260es (0.006763) | – | ||

| INTQt − 1 | – | – | 0.027289es (0.008891) | – | ||

| INTQt − 2 | – | – | – | – | ||

| INTQt − 3 | −0.001538 (0.000316) | – | – | – | ||

| INTQt − 4 | – | – | −0.036627es (0.015661) | – | ||

| INTQt − 5 | – | – | 0.041975es (0.018506) | – | ||

| INTQt − 6 | – | – | – | – | ||

| INTQt − 7 | – | 0.009236 (0.002968) | – | 0.003854 (0.001735) | ||

| INTQt − 8 | – | – | – | 0.004111 (0.001656) | ||

| INTQt − 9 | – | – | −0.039254es (0.014066) | – | ||

| INTQt − 10 | – | – | 0.032643es (0.011380) | – | ||

| Dummy (structural break) | – | – | – | – | ||

| Dummy (positive outliers) | 0.028010 (0.003339) | – | – | – | ||

| Dummy (negative outliers) | −0.015255 (0.002494) | – | – | – | ||

| R 2 | 0.998605 | 0.999010 | 0.999934 | 0.999923 | ||

| Adjusted R 2 | 0.998467 | 0.998605 | 0.999912 | 0.999911 | ||

| DW statistic | 1.901167 | 2.255174 | 2.077281 | 2.089316 | ||

| S.E. of regression | 0.007113 | 0.036217 | 0.013092 | 0.016293 | ||

| Steady state | −0.7412048 | 0.179557 | −0.201098 | 0.07018 | ||

-

*All variables included are statistically significant at 5% and all models were checked for autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity; d, differenced dependent variable lag; es, exponential smoothing; – = does not apply; () includes the standard error of the coefficients.

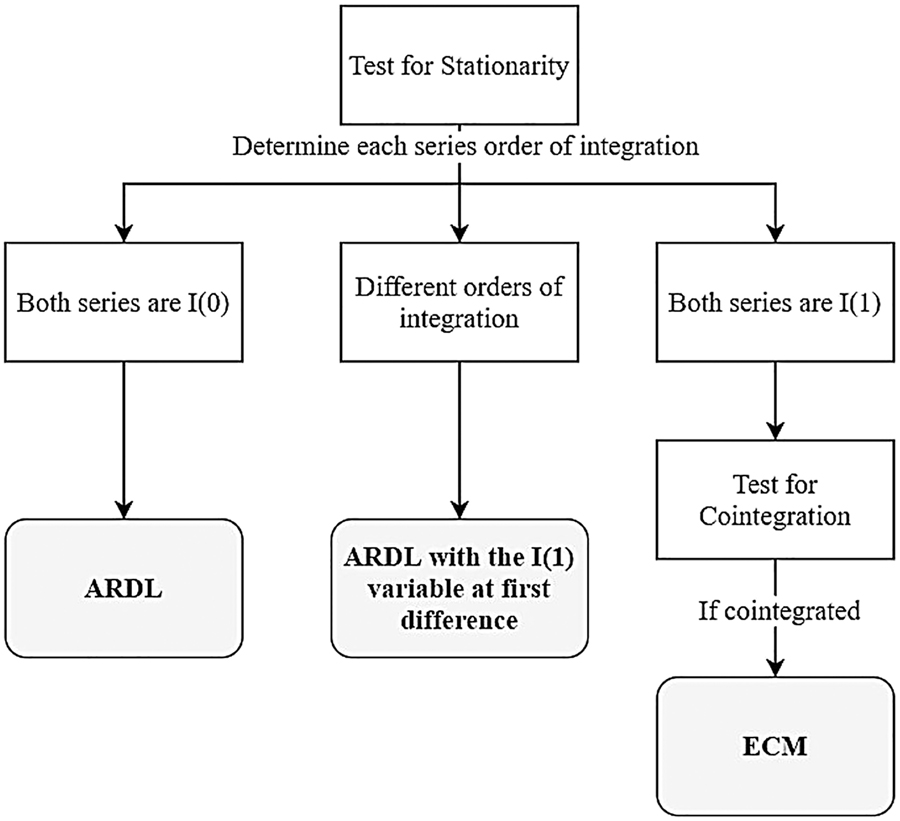

Methodological approach.

References

Ajani, H. A. 1978. “Quarterly Interpolation of Constant Price Gross Domestic Product of Nigeria-1963/64-1972/73.” Economic and Financial Review 16 (2): 2.Suche in Google Scholar

Ajao, I. O., A. G. Ibraheem, and F. J. Ayoola. 2012. “Cubic Spline Interpolation: A Robust Method of Disaggregating Annual Data to Quarterly Series.” Journal of Physical Sciences and Environmental Safety 2 (1): 1–8.Suche in Google Scholar

Bernanke, B. S. 2015. Monetary Policy and Inequality. Economic Commentary (Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland). Also available at https://www.brookings.edu/blog/ben-bernanke/2015/06/01/monetary-policy-and-inequality/.Suche in Google Scholar

Casiraghi, M., E. Gaiotti, L. Rodano, and A. Secchi. 2018. “A “Reverse Robin Hood”? The Distributional Implications of Non-Standard Monetary Policy for Italian Households.” Journal of International Money and Finance 85: 215–35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2017.11.006.Suche in Google Scholar

Cloyne, J., C. Ferreira, and P. Surico. 2020. “Monetary Policy when Households Have Debt: New Evidence on the Transmission Mechanism.” The Review of Economic Studies 87 (1): 102–29, https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdy074.Suche in Google Scholar

Coibion, O., Y. Gorodnichenko, L. Kueng, and J. Silvia. 2017. “Innocent Bystanders? Monetary Policy and Inequality.” Journal of Monetary Economics 88: 70–89, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2017.05.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Davtyan, K. 2017. “The Distributive Effect of Monetary Policy: The Top One Percent Makes the Difference.” Economic Modelling 65: 106–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2017.05.011.Suche in Google Scholar

Dolado, J. J., G. Motyovszki, and E. Pappa. 2021. “Monetary Policy and Inequality Under Labor Market Frictions and Capital-Skill Complementarity.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 13 (2): 292–332, https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20180242.Suche in Google Scholar

El Herradi, M., and A. Leroy. 2019. “Monetary Policy and the Top One Percent: Evidence from a Century of Modern Economic History.” De Nederlandsche Bank Working Paper (Issue 632), 1–40, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3379740.Suche in Google Scholar

Furceri, D., P. Loungani, and A. Zdzienicka. 2018. “The Effects of Monetary Policy Shocks on Inequality.” Journal of International Money and Finance 85: 168–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2017.11.004.Suche in Google Scholar

Galli, R., and R. Van der Hoeven. 2001. Is Inflation Bad for Income Inequality: The Importance of the Initial Rate of Inflation. ILO Employment Paper. No. 2001/29. Suche in Google Scholar

Guerello, C. 2017. “Conventional and Unconventional Monetary Policy vs. Households Income Distribution: An Empirical Analysis for the Euro Area.” Journal of International Money and Finance 85: 187–214, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2017.11.005.Suche in Google Scholar

Inui, M., N. Sudo, and T. Yamada. 2017. “The Effects of Monetary Policy Shocks on Inequality in Japan.” Bank of Japan Working Paper 17-E-3, Bank of Japan, Tokyo.Suche in Google Scholar

Lenza, M., and J. Slacalek. 2018. “How Does Monetary Policy Affect Income and Wealth Inequality? Evidence from Quantitative Easing in the Euro Area.” In ECB Working Paper Series (Issue 2190). Frankfurt a. M.: European Central Bank (ECB), http://dx.doi.org/10.2866/414435.10.2139/ssrn.3275976Suche in Google Scholar

Monnin, P. 2017. “Monetary Policy, Macroprudential Regulation and Inequality.” Council on Economic Policies Discussion Note, 12 April 2017, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2970459.Suche in Google Scholar

Mumtaz, H., and A. Theophilopoulou. 2017. “The Impact of Monetary Policy on Inequality in the UK. An Empirical Analysis.” European Economic Review 98: 410–23, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2017.07.008.Suche in Google Scholar

O’Farrell, R., and L. Rawdanowicz. 2017. “Monetary Policy and Inequality: Financial Channels.” International Finance 20 (2): 174–88, https://doi.org/10.1111/infi.12108.Suche in Google Scholar

Romer, C. D., and D. H. Romer. 1989. “Does Monetary Policy Matter? A New Test in the Spirit of Friedman and Schwartz.” NBER Macroeconomics Annual 4: 121–70, https://doi.org/10.1086/654103.Suche in Google Scholar

Romer, C. D., and D. H. Romer. 2004. “A New Measure of Monetary Shocks: Derivation and Implications.” American Economic Review 94 (4): 1055–84, doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828042002651.Suche in Google Scholar

Saiki, A., and J. Frost. 2014. “Does Unconventional Monetary Policy Affect Inequality? Evidence from Japan.” Applied Economics 46 (36): 4445–54, https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2014.962229.Suche in Google Scholar

Villarreal, F. G. 2014. Monetary Policy and Inequality in Mexico. MPRA Paper 57074. Online at http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/57074/.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editors Note

- Editor’s Note

- Special on COVID-19 Research

- Covid-19 Response Models and Divergences Within the EU: A Health Dis-Union

- Landscape Political Ecology: Rural-Urban Pattern of COVID-19 in Nigeria

- The Relationship Between Poverty and COVID-19 Infection and Case-Fatality Rates in Germany during the First Wave of the Pandemic

- Covid-19: A Trade-off between Political Economy and Ethics

- Special on Inequality, Policy and Society

- Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality – An Overview

- Monetary Policy and the Top 10%: A Time-Series Analysis Using ARDL and ECM

- Trade Intensity, Fiscal Integration and Income Inequality in ECOWAS

- Empirical Analysis of the Effect of Fiscal Policy Shocks in China

- The Political Economy of Sectoral Credit Provisioning in India: An Empirical Analysis

- Perspectives on Gender Stereotypes: How Did Gender-Based Perceptions Put Hillary Clinton at an Electoral Disadvantage in the 2016 Election?

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editors Note

- Editor’s Note

- Special on COVID-19 Research

- Covid-19 Response Models and Divergences Within the EU: A Health Dis-Union

- Landscape Political Ecology: Rural-Urban Pattern of COVID-19 in Nigeria

- The Relationship Between Poverty and COVID-19 Infection and Case-Fatality Rates in Germany during the First Wave of the Pandemic

- Covid-19: A Trade-off between Political Economy and Ethics

- Special on Inequality, Policy and Society

- Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality – An Overview

- Monetary Policy and the Top 10%: A Time-Series Analysis Using ARDL and ECM

- Trade Intensity, Fiscal Integration and Income Inequality in ECOWAS

- Empirical Analysis of the Effect of Fiscal Policy Shocks in China

- The Political Economy of Sectoral Credit Provisioning in India: An Empirical Analysis

- Perspectives on Gender Stereotypes: How Did Gender-Based Perceptions Put Hillary Clinton at an Electoral Disadvantage in the 2016 Election?