Abstract

The symmetric shock of the Covid-19 pandemic has come with heterogeneous consequences across the world. Within the common institutional framework of the European Union, the outbreak has put under extreme stress governance and interplay between the national and supranational level. Under some coordination, responses have remained largely in the hands and on the shoulders of the Member States. In this context, the article classifies pandemic outbreaks and responses along the containment and fiscal support dimensions to uncover whether a common model for Covid-19 crisis management arises across the EU27 or rather different policy choices patterns emerge within the continent. Based on indicators covering the three dimensions derived from the Oxford Covid Government response tracker, the John Hopkins CSSE Covid-19 database and the European Commission Autumn Forecasts, the paper employs hierarchical cluster analysis to uncover response group across countries and characterize them by the outbreak, containment and fiscal support strengths, delineating as well the geographical distribution across and within the clusters. The findings present the heterogeneity of response models, robust to alternative specifications and timeframes across the first and the second wave, deriving broader implications for the outlook for the vaccine-roll out and exit from the crisis. The dynamics in 2020 are also considered in the context of the shortcomings of supranational governance within the EU and the current policy reform debate, highlighting the high stakes for the upcoming Conference on the Future of Europe. The contribution of the work is furthered by offering a systematic methodology and framework to study heterogeneities of pandemic responses within the EU paving the way for further analysis of contributing factors explaining decision-makers policy choices as well as performance concerning political, social and economic outcomes across the models.

Variables Description

| Description | Stringency | Containment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stringency | Index aggregating all eight restrictions (e.g. schools, stay-at-home, workplace closures, travel limitations, etc.) indicators and information campaigns | |||

| Containment | Index aggregating all contained in stringency plus additional health measures indicators (e.g. testing, tracing, facial covering; vaccination, etc.) | |||

| Schools | C1 | Coding: 0 – no measure; 1 – recommended; 2 – required some; 3 required all | x | x |

| Workplace closing | C2 | Coding: 0 – no measure; 1 – recommended; 2 – required some; 3 required all | x | x |

| Cancel public events | C3 | Coding: 0 – no measure; 1 – recommended; 2 – required | x | x |

| Restrictions on gatherings | C4 | Coding: 0 – no measure; 1– >1000; 2 – >101; 3 – >11; 4 < 10 | x | x |

| Close public transport | C5 | Coding: 0 – no measure; 1 – recommended; 2 – required | x | x |

| Stay at home requirements | C6 | Coding: 0 – no measure; 1 – recommended; 2 – required some exceptions; 3 required minimal exceptions | x | x |

| Restrictions on internal movement | C7 | Coding: 0 – no measure; 1 – recommended; 2 – required | x | x |

| International travel controls | C8 | Coding: 0 – no measure; 1 – screening; 2 – quarantine; 3 – ban some; 4 – ban all | x | x |

| Public info campaigns | H1 | Coding: 0 – no measure; 1 – public officials; 2 – coordinated campaign | x | x |

| Testing policy | H2 | Coding: 0 – no testing; 1 – symptoms & target group (e.g. known case, travel); 2 – symptoms; 3 – also asymptomatic | x | |

| Contact tracing | H3 | Coding: 0 no tracing; 1 – limited tracing; 2 – comprehensive tracing | x | |

| Cases | Cumulative cases per million people at the indicated cutoffs | |||

| Deaths | Cumulative deaths per million people at the indicated cutoff |

Sensitivity Analysis

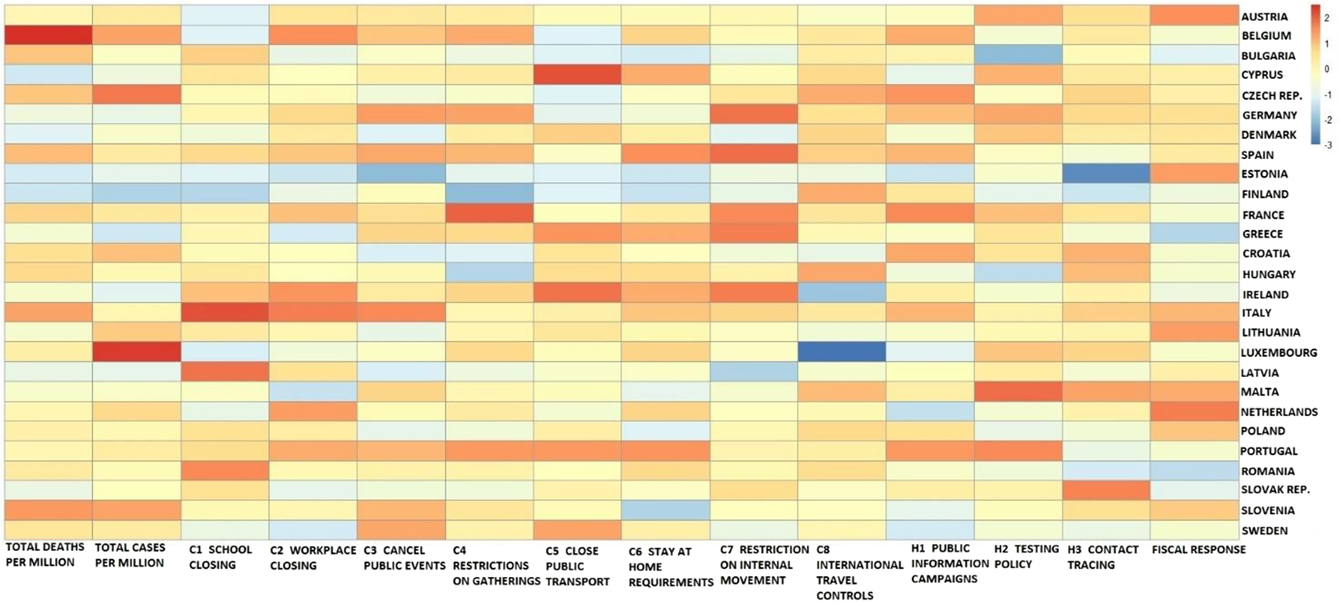

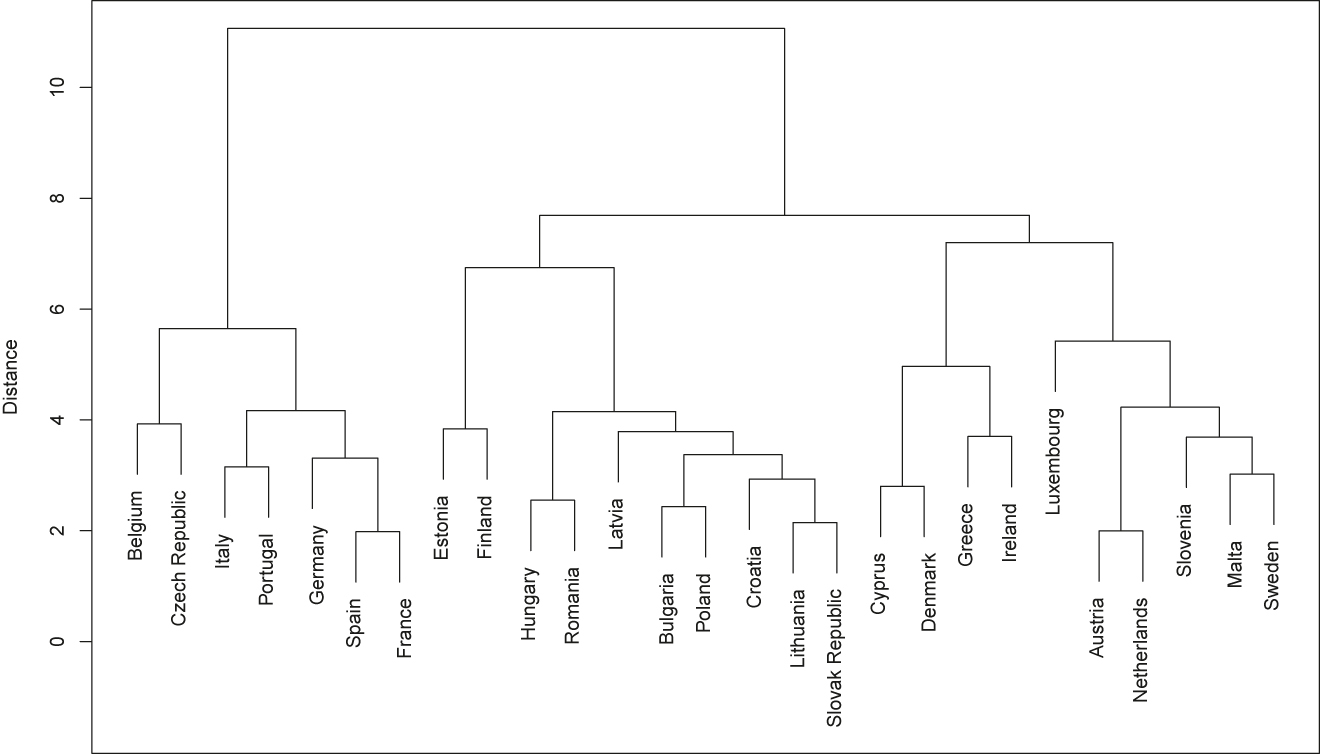

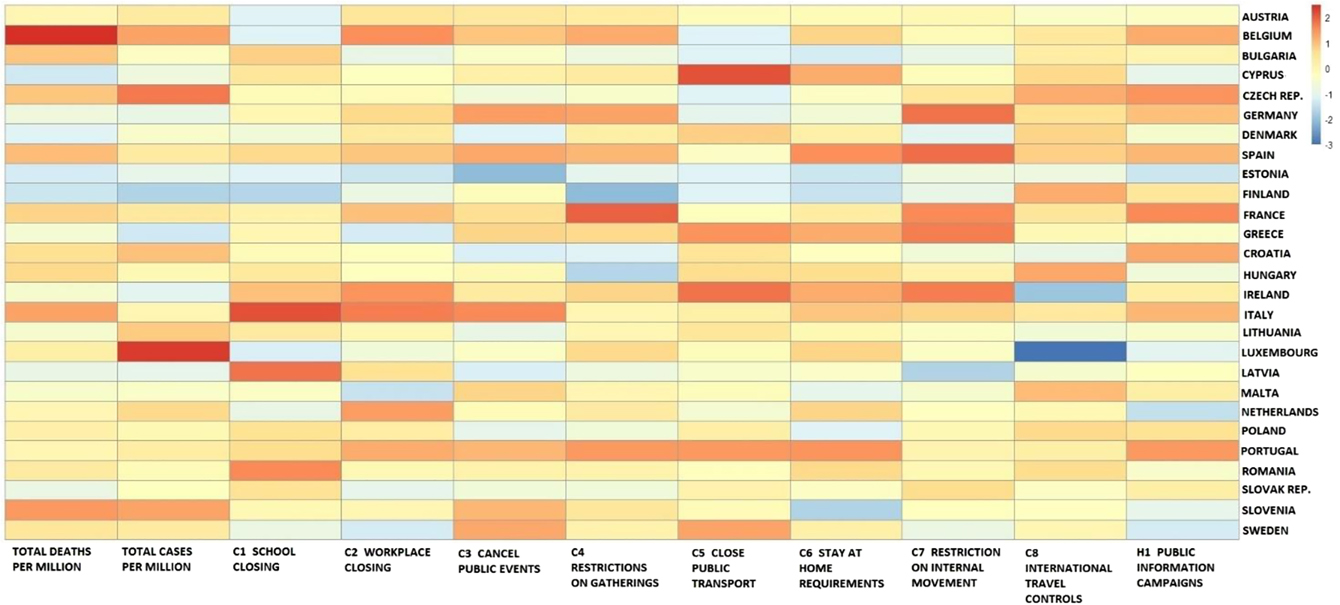

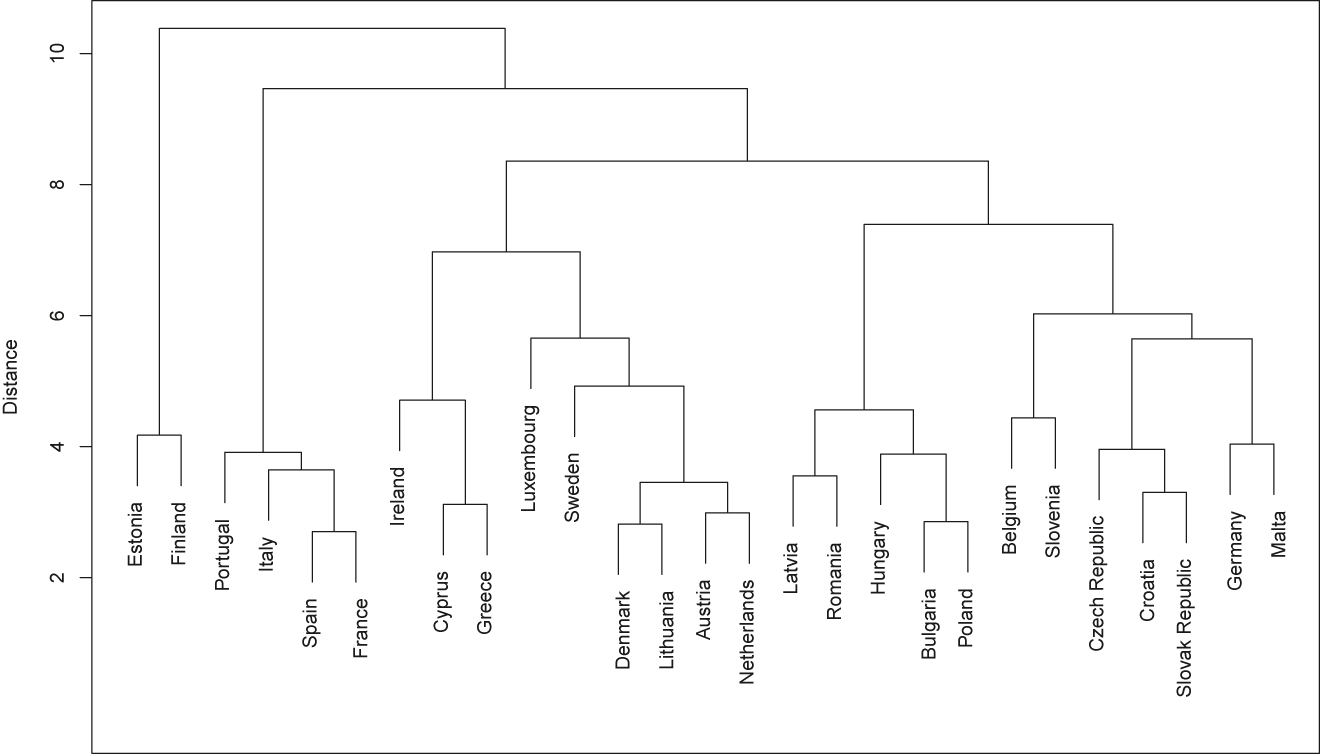

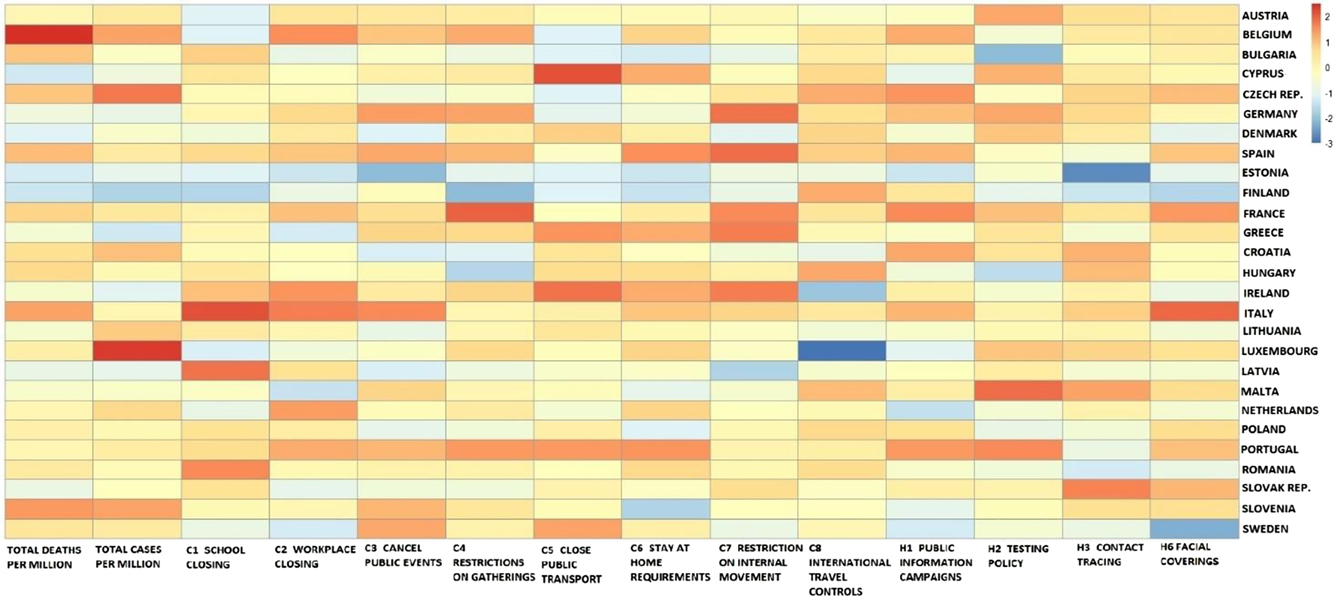

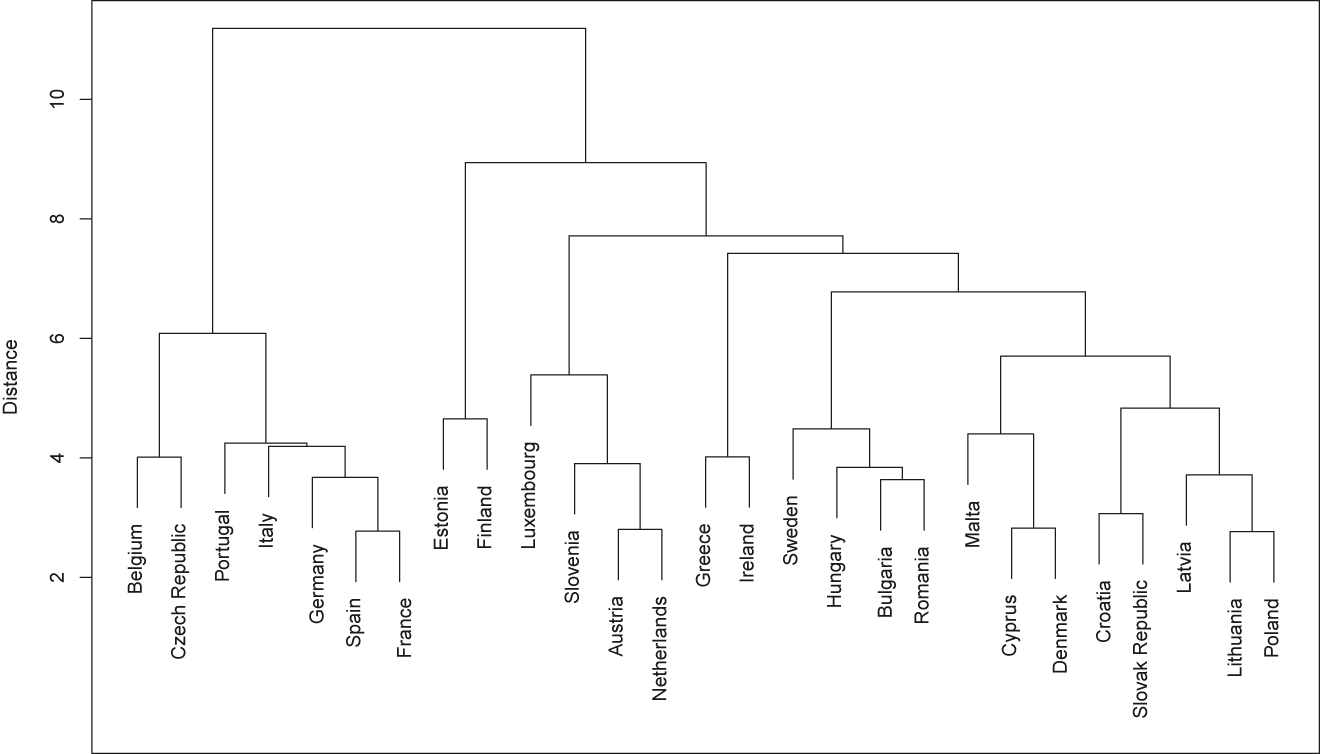

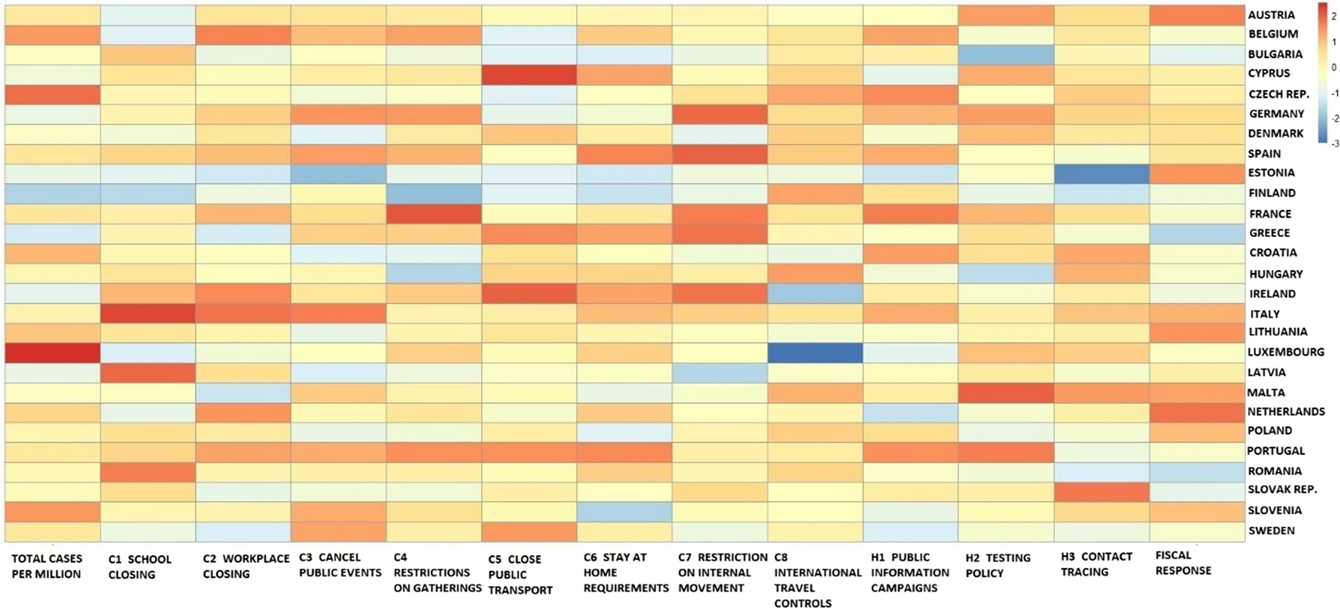

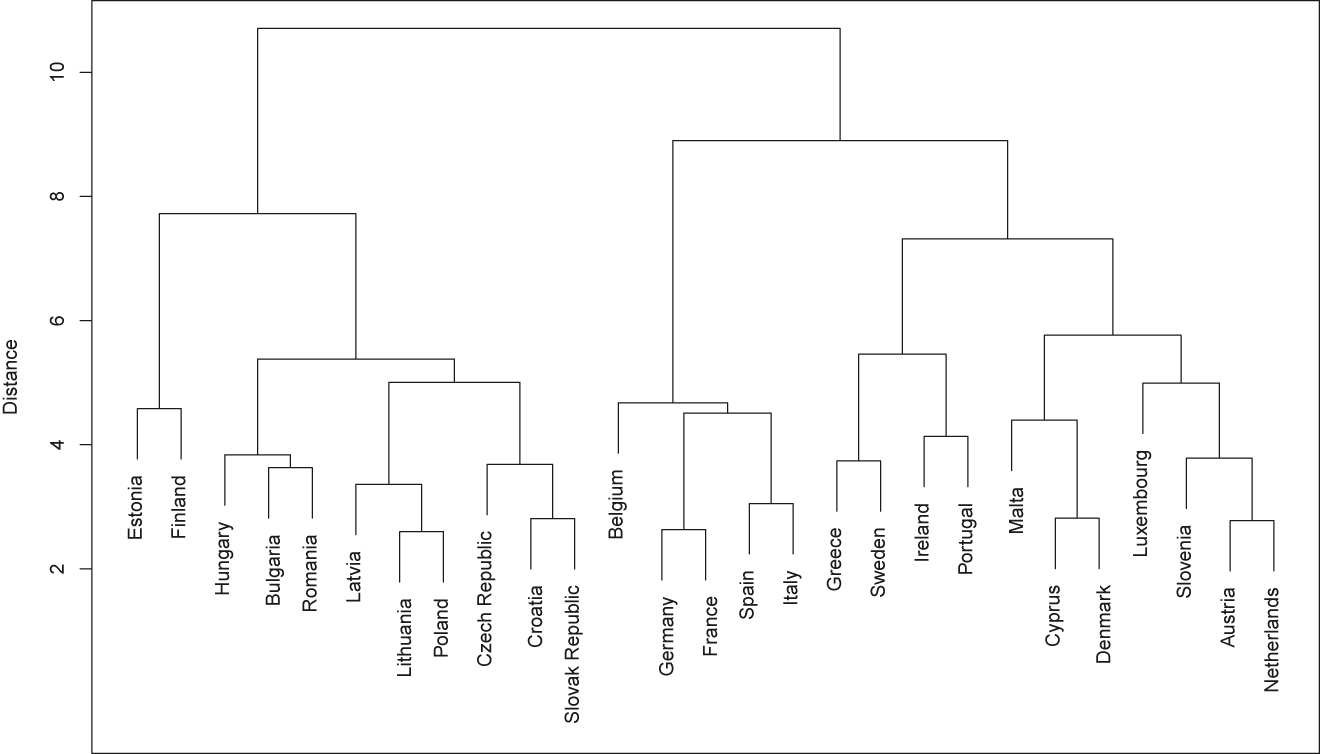

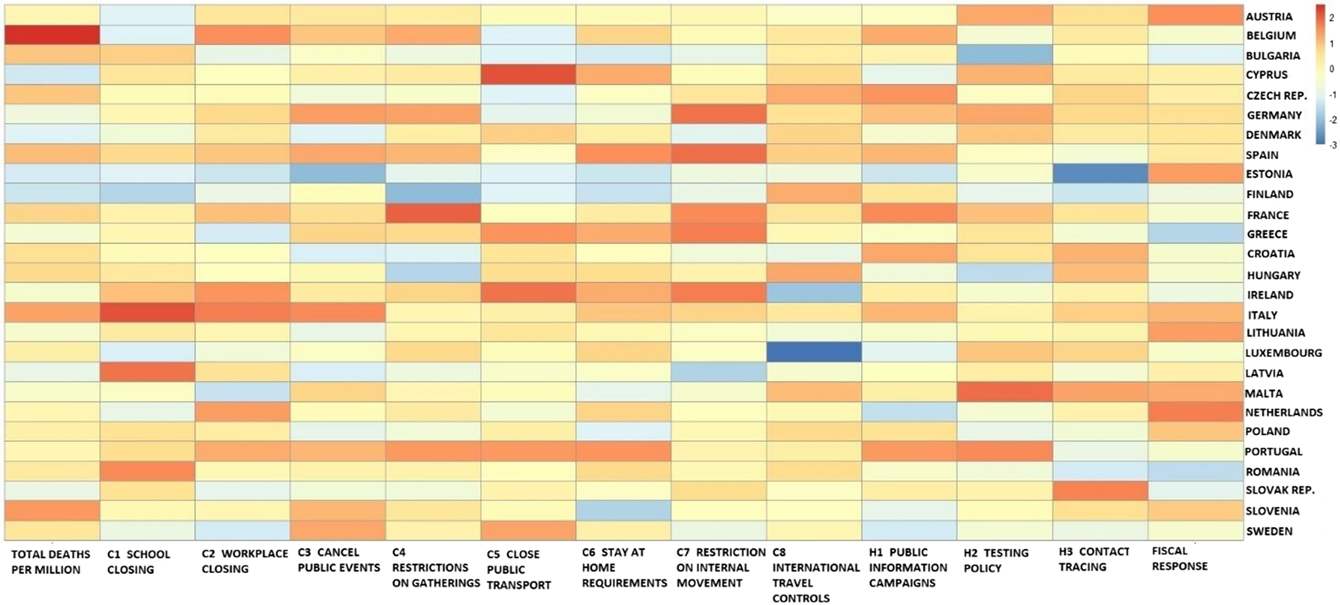

A straightforward candidate for sensitivity analysis relates to the two Oxford pandemic containment indices: the Stringency Index and the Containment and Health Index. The indices are hardly used jointly except for developing a synthetic heatmap as they substantially overlap, given that the first captures containment measures along with public information campaigns and the second the same together with most of the indicators within the health category. Regardless of the overlap, characterizing the pandemic response by one or the other alone leads to substantial changes to the clusters, as shown respectively in Figures 15 and 17 below. The respective heatmaps in Figures 16 and 18 show the variable included for clustering and the respective stringency\strength of measures for each indicator. One notable example is that while containment alone singles out as the leftward branch jointly all countries with high severity in their outbreaks (including Belgium), the same is not the case once health measures such as testing and tracing enter the picture with the second index, alike in the main analysis.

A further distinction – given the divergence in the ranking across the two measures – is worth making for the outbreak characterization itself by cases or by deaths per million inhabitants. Clusters do differ running the full analysis (including fiscal measures) by cases or deaths alone. In the first instance, as shown in Figure 19, the high outbreak strength group is homogenously clustered in the leftward branch, prevailing over the limited fiscal response. Looking at the heatmap in Figure 20 along with the clusters characterization in Table 3 shows how the cases-only cluster homogeneously position all geographically eastwards countries on the rightward branch, regardless of their ranges of high-low fiscal responses. The east-west divide remains in considering deaths alone as shown in Figure 21. However, sub-branches do vary across the two clusters. Nonetheless – as shown in Figure 22 – characterization of the emerging clusters is at first glance more problematic as countries like Greece and Sweden, differing both for the severity of the pandemic, containment policy mix and fiscal response are lower-branch grouped together. While the exercise supports the importance of considering both dimensions of the outbreak as in the main analysis, the key intended takeaway regards the instability of groupings depending on the variables considered.

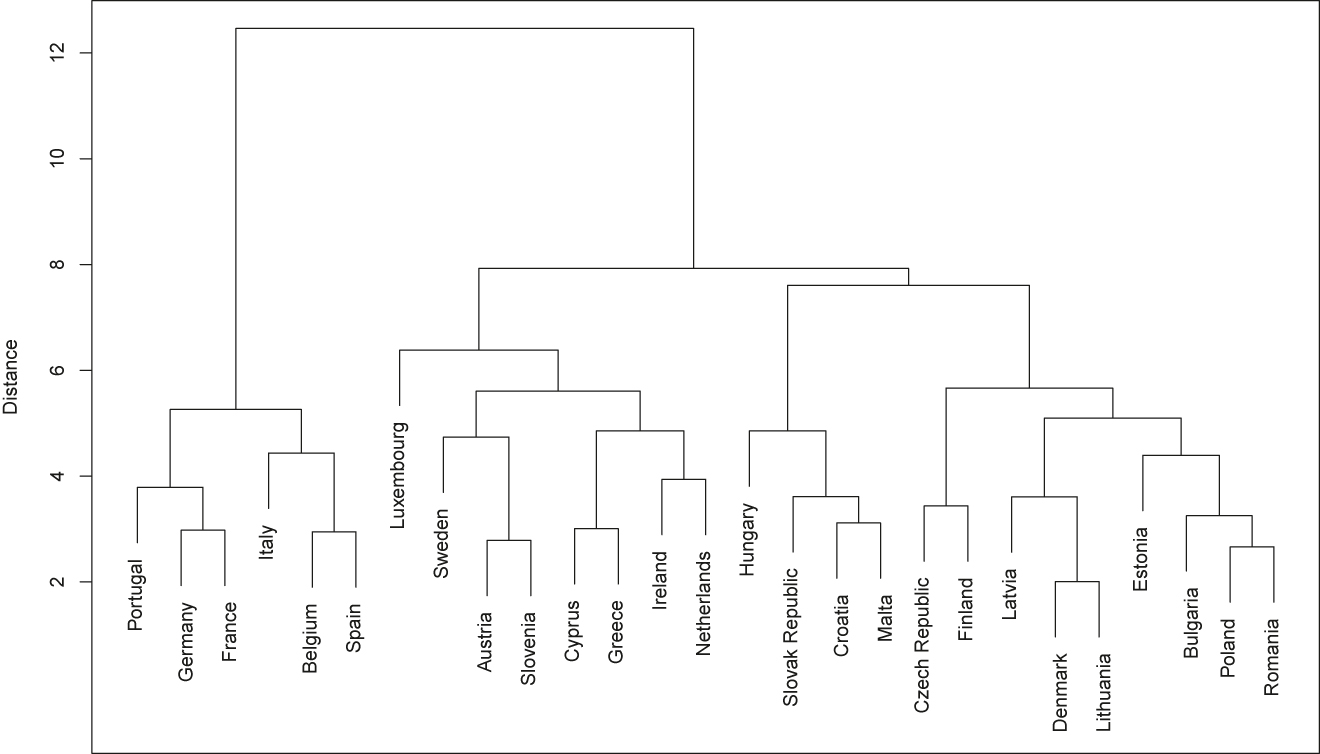

Outbreak and containment clusters in the first wave.

Figure 10 shows the clusters considering the timeframe up to the end of July. While the broad clustering within the heavy outbreak group remains on the left, the Czech Republic is not yet a member of this nefarious club. Moreover, sub-branches change somehow splitting more closely across the death-cases divide (Belgium, Italy, Spain) than the intensity of response measures as in the analysis on 2020 as a whole. Interestingly, the so-far stable couple of Estonia and Finland is split up in the early phase. Finland joins the Czech Republic, one of the subsequently most heavily hit countries (see Figure 11).

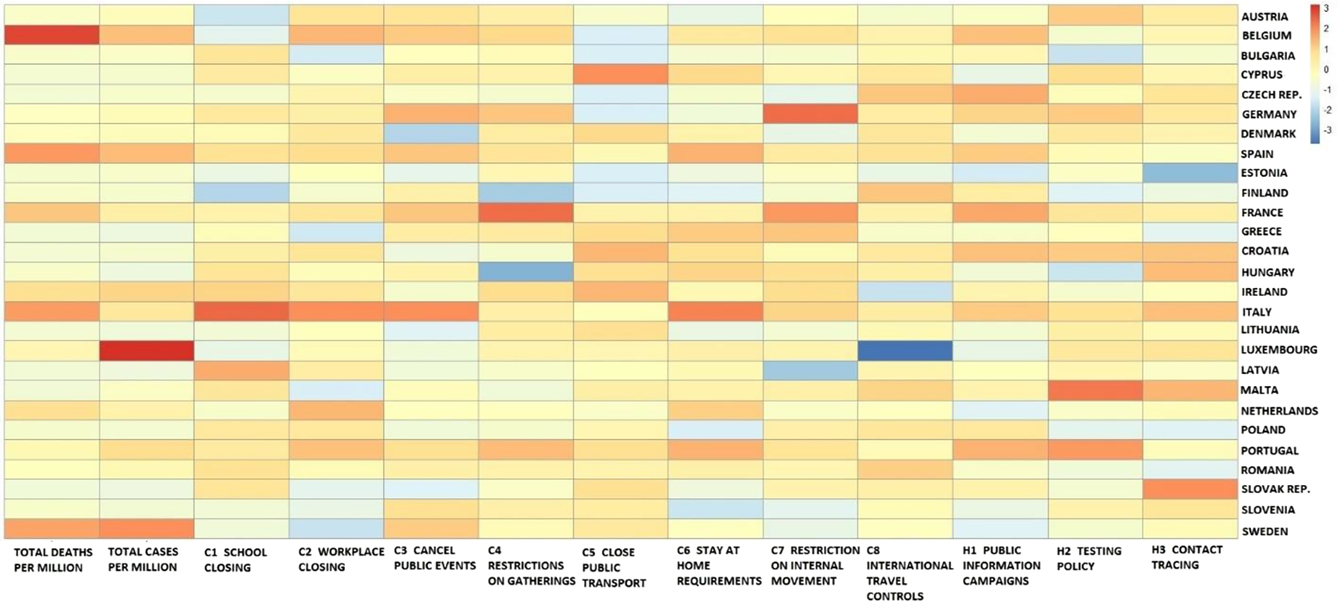

Heatmap of outbreak and containment measures in the first wave.

Short of fully detailing the clusters, four broad groups emerge, the main branch on the left with the heavily impacted Member States and three groups within the branch on the left. As shown in Figure 10, starting from the less sizable group, Hungary, Slovakia, Croatia and Malta are among the most spared by the pandemic, while deploying nonetheless a fairly stringent containment response. The branch to their left is likewise largely spared, but in parallel deploying more modest containment measures. While the remaining branch captures a sizable middle-ground. Heterogeneous responses remain also in the first phase, considering that also in the heavily hit group measures deployed by Italy differ substantially, for example, from the more modest response in Belgium and Spain, among the severely hit countries in the early phase.

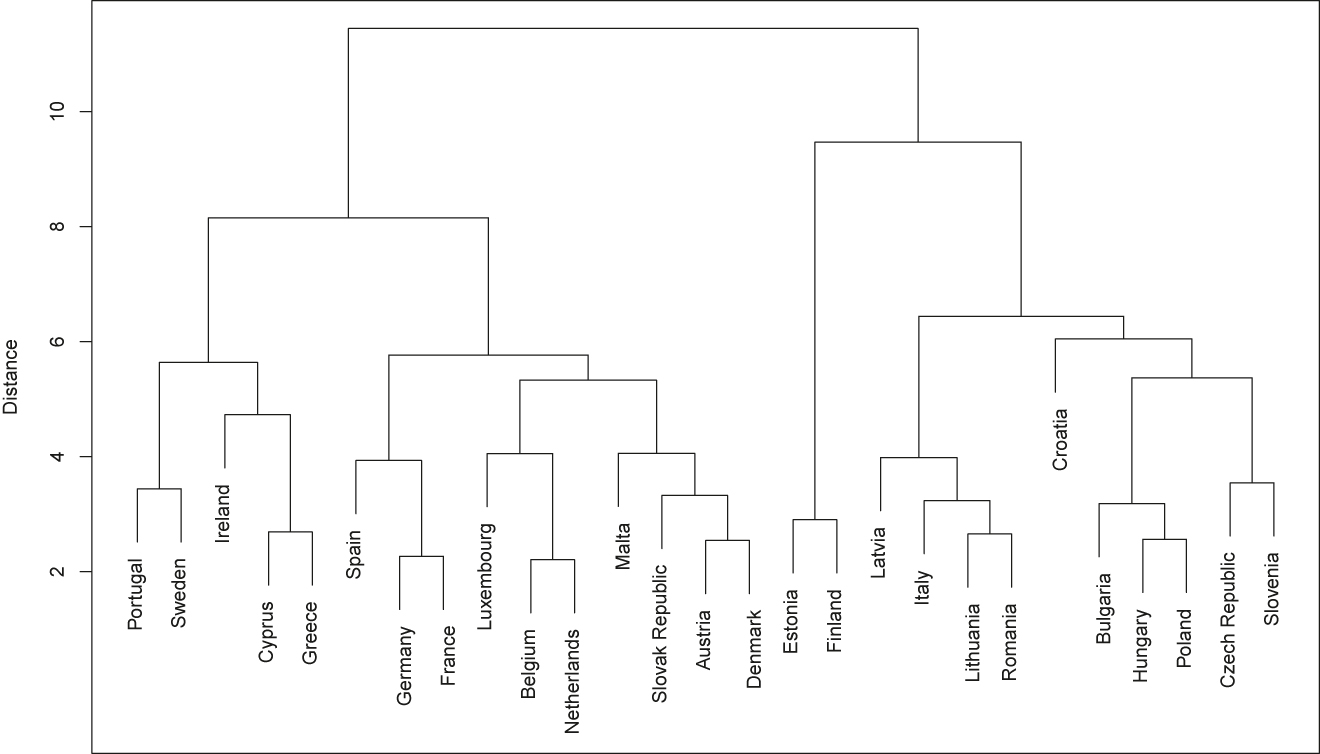

Outbreak and containment clusters in the second wave.

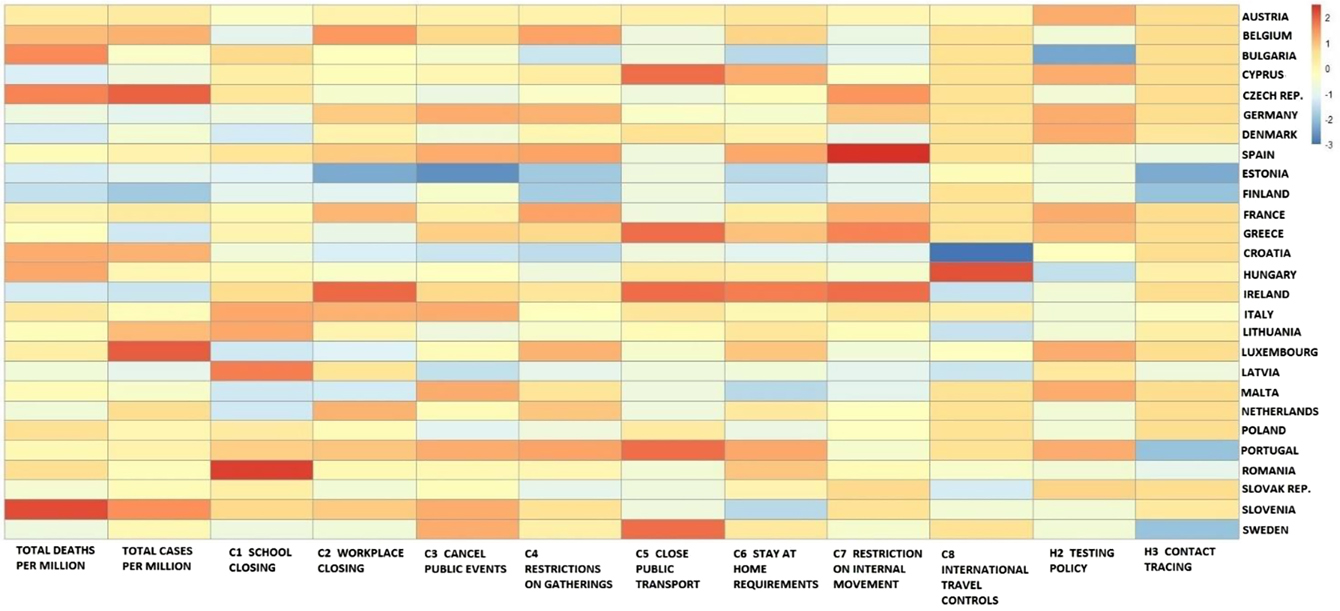

Switching to the post-July period, clusters change substantially. Firstly, some of the usual suspects such as Italy, leave altogether the high incidence group. More in general, the singling out of heavily hit countries is less straightforward. The more moderately hit leftward branch still groups, however, countries such as Italy, Lithuania and Romania with higher responses – especially in terms of school closures – while the heavily hit Czech Republic and Slovenia display limited containment measures, as shown in Figure 12. All to say that regardless of the changes in where countries fall according to outbreak and response, it is not the case that homogeneity emerges in the second wave across the severity of the pandemic and stringency of the deployed measures. Additionally, as well displayed in the heatmap in Figure 12, substantial variation in the chosen policy mix across countries remains even in the later stage. Interestingly, full convergence emerges for information campaigns (hence excluded in the heatmap below) and limited convergence at the extremes emerges for contract tracing. Testing, however, remains heterogeneous and with somewhat limited matching to the severity of the outbreak (see Figure 14).

Heatmap of outbreak and containment measures in the second wave.

Disaggregate Response Model Heatmap

Heatmap showing all disaggregate indices components.

Alternative Specification: Outbreak and Stringency

Outbreak and stringency clusters.

Outbreak and stringency heatmap.

Alternative Specification: Outbreak Plus Containment and Health Index Components

Outbreak and containment and health clusters.

Outbreak and containment and health heatmap.

Alternative Specification: Response Model with Outbreak by Cases

Outbreak (by cases only), containment and fiscal response clusters.

Outbreak (by cases only), containment and fiscal response heatmap.

Alternative Specification: Response Model with Outbreak by Deaths

Outbreak (by deaths only), containment and fiscal response clusters.

Outbreak (by deaths only), containment and fiscal response heatmap.

References

Adamson, G. W., and D. Bawden. 1981. “Comparison of Hierarchical Cluster Analysis Techniques for Automatic Classification of Chemical Structures.” Journal of Chemical Information and Computer Sciences 21 (4): 204–9.10.1021/ci00032a005Suche in Google Scholar

Al-Awadhi, A. M., K. Alsaifi, A. Al-Awadhi, and S. Alhammadi. 2020. “Death and Contagious Infectious Diseases: Impact of the COVID-19 Virus on Stock Market Returns.” Journal of Behavioural and Experimental Finance 27: 100326, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100326.Suche in Google Scholar

Anderson, J., E. Bergamini, S. Brekelmans, A. Cameron, Z. Darvas, M. Domínguez Jíménez, and C. Midões. 2020. The Fiscal Response to the Economic Fallout from the Coronavirus, Bruegel datasets. https://www.bruegel.org/publications/datasets/covid-national-dataset/#france(accessed January 30, 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Arbolino, R., F. Carlucci, A. Cirà, G. Ioppolo, and T. Yigitcanlar. 2017. “Efficiency of the EU Regulation on Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Italy: The Hierarchical Cluster Analysis Approach.” Ecological Indicators 81: 115–23, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.05.053.Suche in Google Scholar

Ascani, A., A. Faggian, and S. Montresor. 2021. “The Geography of COVID‐19 and the Structure of Local Economies: The Case of Italy.” Journal of Regional Science 61 (2): 407–41, https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12510.Suche in Google Scholar

Bartlett, O. 2020. “COVID-19, the European Health Union and the CJEU: Lessons from the Case Law on the Banking Union.” European Journal of Risk Regulation 11 (4): 781–9, https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2020.78.Suche in Google Scholar

Bauer, J., D. Brüggmann, D. Klingelhöfer, W. Maier, L. Schwettmann, D. J. Weiss, and D. A. Groneberg. 2020. “Access to Intensive Care in 14 European Countries: A Spatial Analysis of Intensive Care Need and Capacity in the Light of COVID-19.” Intensive Care Medicine 46 (11): 2026–34, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06229-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Bazzan, G. 2020. “Exploring Integration Trajectories for a European Health Union.” European Journal of Risk Regulation 11 (4): 736–46, https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2020.98.Suche in Google Scholar

Beetsma, R. M. W. J. 1999. “The Stability and Growth Pact in a Model with Politically Induced Deficit Biases.” In Fiscal Aspects of European Monetary Integration, edited by A. Hughes Hallett, M. M. Hutchison, and S. Hougaard Jensen, 189–215. New York: Cambridge University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Begg, I. ed. 2002. Europe: Government and Money; Running EMU: The Challenges of Policy Coordination, London, The Federal Trust.Suche in Google Scholar

Blashfield, R. K. 1976. “Mixture Model Tests of Cluster Analysis: Accuracy of Four Agglomerative Hierarchical Methods.” Psychological Bulletin 83 (3): 377.10.1037/0033-2909.83.3.377Suche in Google Scholar

Bridges, C. C.Jr. 1966. “Hierarchical Cluster Analysis.” Psychological Reports 18 (3): 851–4.10.2466/pr0.1966.18.3.851Suche in Google Scholar

Buiter, W. H. 2006. “The “Sense and Nonsense of Maastricht” Revisited: What Have We Learnt about Stabilization in EMU?” Journal of Communication and Media Studies: Journal of Common Market Studies 44 (4): 687–710, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2006.00658.x.Suche in Google Scholar

Buiter, W., G. Corsetti, N. Roubini, R. Repullo, and J. Frankel. 1993. “Excessive Deficits: Sense and Nonsense in the Treaty of Maastricht.” Economic Policy 8 (16): 57, https://doi.org/10.2307/1344568.Suche in Google Scholar

Bull, M. J. 2018. “In the Eye of the Storm: The Italian Economy and the Eurozone Crisis.” South European Society & Politics 23 (1): 13–28, https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2018.1433477.Suche in Google Scholar

Buonanno, P., S. Galletta, and M. Puca. 2020. “Estimating the Severity of COVID-19: Evidence from the Italian Epicenter.” PloS One 15 (10): e0239569, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239569.Suche in Google Scholar

Buonsenso, D., D. Roland, C. De Rose, P. Vásquez-Hoyos, B. Ramly, J. N. Chakakala-Chaziya, A. Munro, and S. González-Dambrauskas. 2021. “Schools Closures During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 40 (4): e146-50.10.1097/INF.0000000000003052Suche in Google Scholar

Burlina, C., and A. Rodríguez-Pose. 2020. Institutions and the Uneven Geography of the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic (No. 15443). CEPR Discussion Papers.10.1111/jors.12541Suche in Google Scholar

Buthe, T., J. Barceló, C. Cheng, P. Ganga, L. Messerschmidt, A. S. Hartnett, and R. Kubinec. 2020. “Patterns of Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Federal vs. Unitary European Democracies.” Unitary European Democracies. (September 7, 2020).10.2139/ssrn.3692035Suche in Google Scholar

Camous, A., and G. Claeys. 2020. “The Evolution of European Economic Institutions during the COVID‐19 Crisis.” European Policy Analysis 6 (2): 328–41, https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1100.Suche in Google Scholar

Casert, R. 2021. Delay in Pfizer Vaccine Shipments Frustrate Europe. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/europe-north-america-italy-united-kingdom-coronavirus-pandemic-0d45764c6d66cfc655bc048aaf7eeb72 (accessed January 30, 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Ceron, M., and C. M. Palermo. 2020. “La risposta alla pandemia in Francia, Germania, Italia e Spagna durante la prima ondata (Pandemic Response in France, Germany, Italy and Spain during COVID-19 First Wave).” SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3746658.Suche in Google Scholar

Ceron, M., C. M. Palermo, and V. Salpietro. 2020. “Limiti e prospettive della gestione europea durante la pandemia da Covid-19.” Biblioteca Delle Libertà LV (228): 1–31, https://doi.org/10.23827/BDL_2020_2_3.Suche in Google Scholar

Charron, N., V. Lapuente, and A. Rodriguez-Pose. 2020. “Uncooperative Society, Uncooperative Politics or Both? How Trust, Polarization and Populism Explain Excess Mortality for COVID-19 across European Regions.” The QoG Institute Working Paper Series 2020: 12.Suche in Google Scholar

Chisadza, C., M. Clance, and R. Gupta. 2021. “Government Effectiveness and the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Sustainability 13 (6): 3042, https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063042.Suche in Google Scholar

Colfer, B. 2020. “Public Policy Responses to COVID‐19 in Europe.” European Policy Analysis 6 (2): 126–37, https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1097.Suche in Google Scholar

Creel, J., P. Hubert, and F. Saraceno. 2012. “The European Fiscal Compact: A Counterfactual Assessment.” Journal of Economic Integration 27 (4): 537–63, https://doi.org/10.11130/jei.2012.27.4.537.Suche in Google Scholar

CSSE. 2020. COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19 (accessed January 30, 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

De Grauwe, P. 2007. Economics of Monetary Union, 7th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

de Jong, M., and A. T. Ho. 2020. “Emerging Fiscal Health and Governance Concerns Resulting from COVID-19 Challenges.” Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting and Financial Management: 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-07-2020-0137.Suche in Google Scholar

Eichengreen, B., and C. Wyplosz. 1998. “The Stability Pact: More Than a Minor Nuisance?” Economic Policy 13 (26): 65–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0327.00029.Suche in Google Scholar

European Commission. 2020. Autumn Economic Forecast 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/economy-finance/ip136_en_2.pdf (accessed January 30, 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Eurostat. 2017. Health in the European Union – Facts and Figures. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Health_in_the_European_Union_–_facts_and_figures (accessed January 30, 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Fabbrini, S., and U. Puetter. 2016. “Integration without Supranationalisation: Studying the Lead Roles of the European Council and the Council in Post-Lisbon EU Politics.” Journal of European Integration 38 (5): 481–95, https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1178254.Suche in Google Scholar

Fabbris, L. 1991. Analisi esplorativa di dati multidimensionali. Padova: Cleup.Suche in Google Scholar

Franchino, F. 2020. “In Search of the Ideational Foundations of EU Fiscal Governance: Standard Ideas, Imperfect Rules.” Journal of European Integration 42 (2): 179–94, https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1657858.Suche in Google Scholar

Fineberg, H. V. 2014. “Pandemic Preparedness and Response — Lessons from the H1N1 Influenza of 2009.” New England Journal of Medicine 370 (14): 1335–42, https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1208802.Suche in Google Scholar

Fraiman, R., A. Justel, and M. Svarc. 2008. “Selection of Variables for Cluster Analysis and Classification Rules.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 103 (483): 1294–303, https://doi.org/10.1198/016214508000000544.Suche in Google Scholar

Fraley, C., and A. E. Raftery. 1998. “How Many Clusters? Which Clustering Method? Answers via Model-Based Cluster Analysis.” The Computer Journal 41 (8): 578–88, https://doi.org/10.1093/comjnl/41.8.578.Suche in Google Scholar

Frey, C. B., C. Chen, and G. Presidente. 2020. “Democracy, Culture, and Contagion: Political Regimes and Countries Responsiveness to Covid-19.” Covid Economics (18). https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/publications/democracy-culture-and-contagion-political-regimes-and-countries-responsiveness-to-covid-19/.Suche in Google Scholar

Gambarotto, F., and S. Solari. 2015. “The Peripheralization of Southern European Capitalism within the EMU.” Review of International Political Economy 22 (4): 788–812, https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2014.955518.Suche in Google Scholar

Grasselli, G., A. Pesenti, and M. Cecconi. 2020. “Critical Care Utilization for the COVID-19 Outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: Early Experience and Forecast During an Emergency Response.” Jama 323 (16): 1545–6, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4031.10.1001/jama.2020.4031Suche in Google Scholar

Gruchoła, M., and M. Sławek-Czochra. 2021. “The Culture of Fear” of Inhabitants of EU Countries in Their Reaction to the COVID-19 Pandemic – A Study Based on the Reports of the Eurobarometer.” Safety Science 135: 105–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.105140.Suche in Google Scholar

Gruvaeus, G., and H. Wainer. 1972. “Two Additions to Hierarchical Cluster Analysis.” British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology 25 (2): 200–6.10.1111/j.2044-8317.1972.tb00491.xSuche in Google Scholar

Hale, T., S. Webster, A. Petherick, T. Phillips, and B. Kira. 2020. Oxford Covid-19 Government Response Tracker. Oxford: Blavatnik School of Government, n. 25.Suche in Google Scholar

Heipertz, M., and A. Verdun. 2010. Ruling Europe: The Politics of the Stability and Growth Pact. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511750380.Suche in Google Scholar

Heise, A. 2012. “Governance without Government: Or, The Euro Crisis and What Went Wrong with European Economic Governance.” International Journal of Political Economy 41 (2): 42–60.10.2753/IJP0891-1916410203Suche in Google Scholar

Howarth, D., and A. Verdun. 2020. “Economic and Monetary Union at Twenty: A Stocktaking of a Tumultuous Second Decade: Introduction.” Journal of European Integration 42 (3): 287–93.10.1080/07036337.2020.1730348Suche in Google Scholar

Issing, O. 2011. “The Crisis of European Monetary Union - Lessons to Be Drawn.” Journal of Policy Modeling 33 (5): 737–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2011.07.006.Suche in Google Scholar

Jones, E., R. D. Kelemen, and S. Meunier. 2016. “Failing Forward? The Euro Crisis and the Incomplete Nature of European Integration.” Comparative Political Studies 49 (7): 1010–34, https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015617966.Suche in Google Scholar

Jordana, J., and J. C. Triviño-Salazar. 2020. “Where are the ECDC and the EU-wide Responses in the COVID-19 Pandemic?” The Lancet 395 (10237): 1611–2, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31132-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Knoll, M. D., and C. Wonodi. 2021. “Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccine Efficacy.” The Lancet 397 (10269): 72–4, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32623-4.Suche in Google Scholar

Köhn, H. F., and L. J. Hubert. 2014. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis. Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118445112.stat02449.pub2.Suche in Google Scholar

Lane, P. R. 2012. “The European Sovereign Debt Crisis.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 26 (3): 49–68, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.26.3.49.Suche in Google Scholar

Legido-Quigley, H., J. T. Mateos-García, V. R. Campos, M. Gea-Sánchez, C. Muntaner, and M. McKee. 2020. “The Resilience of the Spanish Health System against the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The Lancet Public Health 5 (5): e251–2, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30060-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Lopes, H. E. G., and M. D. S. Gosling. 2021. “Cluster Analysis in Practice: Dealing with Outliers in Managerial Research.” Revista de Administração Contemporânea 25 (1): 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-7849rac2021200081.Suche in Google Scholar

Matthijs, M., and K. McNamara. 2015. “The Euro Crisis’ Theory Effect: Northern Saints, Southern Sinners, and the Demise of the Eurobond.” Journal of European Integration 37 (2): 229–45, https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2014.990137.Suche in Google Scholar

McEnvoy, E., and D. Ferri. 2020. “The Role of the Joint Procurement Agreement during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Assessing Its Usefulness and Discussing Its Potential to Support a European Health Union.” European Journal of Risk Regulation 11 (4): 851–63, https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2020.91.Suche in Google Scholar

Milligan, G. W., and M. C. Cooper. 1988. “A Study of Standardization of Variables in Cluster Analysis.” Journal of Classification 5 (2): 181–204.10.1007/BF01897163Suche in Google Scholar

Mossialos, E., G. Permanand, R. Baeten, and T. Hervey. 2010. “Health Systems Governance in Europe: The Role of European Union Law and Policy.” In Health Systems Governance in Europe, edited by E. Mossialos, G. Permanand, R. Baeten, and T. K. Hervey, 1–83. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511750496.002.Suche in Google Scholar

Nota, B. 2017. “Gogadget: An R Package for Interpretation and Visualization of GO Enrichment Results.” Molecular Informatics 36 (5–6): 1600132, https://doi.org/10.1002/minf.201600132.Suche in Google Scholar

Notermans, T., and S. Piattoni. 2020. “EMU and the Italian Debt Problem: Destabilising Periphery or Destabilising the Periphery?” Journal of European Integration 42 (3): 345–62, https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1730353.Suche in Google Scholar

Oksanen, A., M. Kaakinen, R. Latikka, I. Savolainen, N. Savela, and A. Koivula. 2020. “Regulation and Trust: 3-Month Follow-up Study on COVID-19 Mortality in 25 European Countries.” JMIR Public Health and Surveillance 6 (2): 1–12, https://doi.org/10.2196/19218.Suche in Google Scholar

Pacces, A. M., and M. Weimer. 2020. “From Diversity to Coordination: A European Approach to COVID-19.” European Journal of Risk Regulation 11 (2): 283–96, https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2020.36.Suche in Google Scholar

Pagoulatos, G. 2020. “EMU and the Greek Crisis: Testing the Extreme Limits of an Asymmetric Union.” Journal of European Integration 42 (3): 363–79, https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1730352.Suche in Google Scholar

Palermo, C. M. 2020. “Covid-19: US and EU, Why the Outbreak Could Induce an Institutional Evolution.” CESPI/Note and SSRN Electronic Journal, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3568215.Suche in Google Scholar

Petherick, A., B. Kira, N. Angrist, T. Hale, T. Phillips, and S. Webster. 2020. Variation in Government Responses to COVID-19. Blavatnik Centre for Government Working Paper, University of Oxford. https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/publications/variation-government-responses-covid-19 (accessed May 28, 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Pheatmap Package. 2019. Manual of the Pheatmap Package on R-Studio. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/pheatmap.pdf (accessed May 09, 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Power, K. 2020. “The COVID-19 Pandemic Has Increased the Care Burden of Women and Families.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 16 (1): 67–73.10.1080/15487733.2020.1776561Suche in Google Scholar

Renda, A., and R. Castro. 2020. “Towards Stronger EU Governance of Health Threats after the COVID-19 Pandemic.” European Journal of Risk Regulation 11 (2): 273–82, https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2020.34.Suche in Google Scholar

Rhodes, A., P. Ferdinande, H. Flaatten, B. Guidet, P. G. Metnitz, and R. P. Moreno. 2012. “The Variability of Critical Care Bed Numbers in Europe.” Intensive Care Medicine 38 (10): 1647–53, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-012-2627-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Ritter, G. 2014. Robust Cluster Analysis and Variable Selection. Boca Raton: CRC Press.10.1201/b17353Suche in Google Scholar

Romesburg, C. 2004. Cluster analysis for Researchers. Raleigh: Lulu.com.Suche in Google Scholar

Roser, M., H. Ritchie, E. Ortiz-Ospina, and J. Hasell. 2020. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (accessed January 30, 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Rovellini, A., and S. Paniagua Mesa. 2020. “Milano, accertati i primi tre casi di coronavirus: un 38enne italiano è ricoverato a Codogno.” Milano Today. https://www.milanotoday.it/attualita/coronavirus-codogno.html (accessed January 30, 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Sabat, I., S. Neuman-Böhme, N. E. Varghese, P. P. Barros, W. Brouwer, J. van Exel, and T. Stargardt. 2020. “United but Divided: Policy Responses and People’s Perceptions in the EU during the COVID-19 Outbreak.” Health Policy 124 (9): 909–18.10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.06.009Suche in Google Scholar

Saenz, V. B., D. Hatch, B. E. Bukoski, S. Kim, K. H. Lee, and P. Valdez. 2011. “Community College Student Engagement Patterns: A Typology Revealed through Exploratory Cluster Analysis.” Community College Review 39 (3): 235–67, https://doi.org/10.1177/0091552111416643.Suche in Google Scholar

Sebhatu, A., K. Wennberg, S. Arora-Jonsson, and S. I. Lindberg. 2020. “Explaining the Homogeneous Diffusion of COVID-19 Nonpharmaceutical Interventions across Heterogeneous Countries.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (35): 21201–8, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2010625117.Suche in Google Scholar

Steinley, D., and M. J. Brusco. 2008. “Selection of Variables in Cluster Analysis: An Empirical Comparison of Eight Procedures.” Psychometrika 73 (1): 125–44.10.1007/s11336-007-9019-ySuche in Google Scholar

Townend, D., R. van de Pas, L. Bongers, S. Haque, B. Wouters, E. Pilot, N. Stahl, P. Schröder-Bäck, D. Shaw, and T. Krafft. 2020. “What is the Role of the European union in the Covid-19 Pandemic?” Medicine & Law 39 (2): 249–68.Suche in Google Scholar

Vinogradova, K., A. Dibrov, and G. Myers. 2020. Towards Interpretable Semantic Segmentation via Gradient-Weighted Class Activation Mapping. arXiv preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/2002.11434 (accessed January 30, 2021).10.1609/aaai.v34i10.7244Suche in Google Scholar

Vollmer, M., S. Mishra, H. Unwin, A. Gandy, T. Melan, V. Bradley, Z. Harrison, H. Coupland, I. Hawryluk, M. Hutchinson, O. Ratmann, M. Monod, P. Walker, C. Whittaker, L. Cattarino, C. Ciavarella, L. Cilloni, K. Ainslie, M. Baguelin, S. Bhatia, A. Boonyasiri, N. Brazeau, G. Charles, L. Cooper, Z. Cucunuba, G. Cuomo-Dannenburg, A. Dighe, B. Djaafara, J. Eaton, S. van Elsland, R. FitzJohn, K. Fraser, K. Gaythorpe, W. Green, S. Hayes, N. Imai, B. Jeffrey, E. Knock, D. Laydon, J. Lees, T. Mangal, A. Mousa, G. Nedjati-Gilani, P. Nouvellet, D. Olivera, K. Parag, M. Pickles, H. Thompson, R. Verity, C. Walters, H. Wang, Y. Wang, O. Watson, L. Whittles, X. Xiaoyue, A. Ghani, S. Riley, L. Okell, D. Donnelly, N. Ferguson, I. Dorigatti, S. Flaxman, and S. Bhatt. 2020. “Report 20: A Sub-national Analysis of the Rate of Transmission of Covid-19 in Italy.” medRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.05.20089359.Suche in Google Scholar

Whenam, C. 2020. The Gendered Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis and Post-crisis Period. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/658227/IPOL_STU(2020)658227_EN.pdf (accessed May 20, 2021).Suche in Google Scholar

Wyplosz, C. 2017. “The Eurozone Crisis: A Near-Perfect Case of Mismanagement.” In Political Economy Perspectives on the Greek Crisis, Vol. 2009, 41–59. Cham: Springer International Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63706-8_2.Suche in Google Scholar

Yim, O., and K. T. Ramdeen. 2015. “Hierarchical Cluster Analysis: Comparison of Three Linkage Measures and Application to Psychological Data.” The Quantitative Methods for Psychology 11 (1): 8–21, https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.11.1.p008.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editors Note

- Editor’s Note

- Special on COVID-19 Research

- Covid-19 Response Models and Divergences Within the EU: A Health Dis-Union

- Landscape Political Ecology: Rural-Urban Pattern of COVID-19 in Nigeria

- The Relationship Between Poverty and COVID-19 Infection and Case-Fatality Rates in Germany during the First Wave of the Pandemic

- Covid-19: A Trade-off between Political Economy and Ethics

- Special on Inequality, Policy and Society

- Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality – An Overview

- Monetary Policy and the Top 10%: A Time-Series Analysis Using ARDL and ECM

- Trade Intensity, Fiscal Integration and Income Inequality in ECOWAS

- Empirical Analysis of the Effect of Fiscal Policy Shocks in China

- The Political Economy of Sectoral Credit Provisioning in India: An Empirical Analysis

- Perspectives on Gender Stereotypes: How Did Gender-Based Perceptions Put Hillary Clinton at an Electoral Disadvantage in the 2016 Election?

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Editors Note

- Editor’s Note

- Special on COVID-19 Research

- Covid-19 Response Models and Divergences Within the EU: A Health Dis-Union

- Landscape Political Ecology: Rural-Urban Pattern of COVID-19 in Nigeria

- The Relationship Between Poverty and COVID-19 Infection and Case-Fatality Rates in Germany during the First Wave of the Pandemic

- Covid-19: A Trade-off between Political Economy and Ethics

- Special on Inequality, Policy and Society

- Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality – An Overview

- Monetary Policy and the Top 10%: A Time-Series Analysis Using ARDL and ECM

- Trade Intensity, Fiscal Integration and Income Inequality in ECOWAS

- Empirical Analysis of the Effect of Fiscal Policy Shocks in China

- The Political Economy of Sectoral Credit Provisioning in India: An Empirical Analysis

- Perspectives on Gender Stereotypes: How Did Gender-Based Perceptions Put Hillary Clinton at an Electoral Disadvantage in the 2016 Election?