Abstract

The article proposes an analytical model that places the material dimension of texts at the center of mediatization processes. The model, based on identifying “solid,” “liquid,” and “gaseous” mediatizations, can be used to understand a wide range of mediatization processes from a material perspective. It is also a very useful tool for classifying these processes and verifying their mutations over time as well as their coexistence in the same historical period. To exemplify the model, the article presents a series of historical cases of war mediatization, from the mediatization of World War II in newspapers, the Gulf War on TV, and the current mediatization of the invasion of Ukraine in social media like TikTok. Beyond applying the model, the article introduces a series of considerations on the different states of mediatization and the intermedia relationships between them, both from a space and temporal perspective. A final reflection the material dimension of those processes concludes the article.

Although it may sound contradictory, this article proposes a structuralist-inspired analytical model for evidencing the material dimension in mediatization studies. The article moves between two perspectives: On one hand, the text is inspired by one of the classic models developed by Claude Lévi-Strauss; like other models created in the context of structuralism, it takes abstraction to the extreme limits of formalism. On the other hand, the objective of this intervention is to increase the “materiality” of the theoretical approaches to mediatization, proposing an analytical model for framing their material dimension. The model not only facilitates bringing into focus a wide range of mediatization processes from a material perspective, it is also a very useful tool for classifying these processes and verifying their mutations over time and their coexistence in the same historical period.

1 Semiotics and mediatization

If the study of mediatization processes in Europe moved between a constructivist and a socio-institutional approach (e.g., Couldry and Hepp 2013, 2017; Hepp 2020; Hjarvard 2008, 2013, 2014; Krotz 2014; Lundby 2009, 2014a), based on the contributions of researchers like Finnemann (2014) and Jansson (2014), Lundby (2014b) suggested the existence of a possible third perspective: the materialist one (see Section 3.2). In Latin America researchers pointed to the semio-discursive nature of the media construction of reality (e.g., Carlón 2015, 2018, 2022; Fernández 2017, 2018, 2021; Valdettaro 2021; Verón 1987, 1997, 2013, 2014). These approaches, although they are sometimes different due to their disciplinary origins, have many characteristics in common; for example, Krotz and Verón share a similar longue durée conception of mediatization processes, while Hjarvard considered mediatization as a phenomenon of late modernity (Scolari and Rodríguez-Amat 2018; Scolari et al. 2021).

Verón’s semio-discursive approach to mediatization conceives it as a process of social semiosis – that is, the production and transformation of meaning within social practices. Within this framework, media are not merely channels but active agents that modulate how meaning is generated and circulated (Verón 1987, 1997, 2014). This perspective highlights the interplay between material media technologies and symbolic forms (see Verón 2013), shaping social realities. Consequently, mediatization transforms institutions and subjects by embedding media deeply within the processes of meaning-making that structure society.

2 Semiotics and material turn

In parallel, in the last two decades there have been a series of philosophical and theoretical shifts that have led to talk of a “material turn” in the social sciences and humanities (Bennett 2010; Bennett and Joyce 2010; Coole and Frost 2010; Grusin 2015). Media and Communication studies are not excluded from this material turn: from Parikka’s (2015) “geology of media” to Bollmer’s (2019) “materialist media theory” or the more recent “media evolutionary” approaches (Scolari 2023), the material dimension is increasingly present in theoretical conversations on media. In this context, it could be said that any communication process has a material dimension that expresses itself in different textual supports (clay, papyrus, paper, screens, etc.) and infrastructures (libraries, VCR, satellites, server farms, etc.). How does this “materiality” affect mediatization and text circulation processes?

Far from being a passive observer of the “material turn” in the humanities and social sciences, semiotics has actively engaged with this shift. Several scholars have highlighted the significance of materiality in meaning-making processes. Materiality is not a neutral conduit of meaning but actively shapes the conditions under which signs are produced, interpreted, and circulated. As Keane (2003) argues, material forms mediate meaning through indexical and iconic properties that exceed symbolic representation. Björkvall and Karlsson (2011), drawing on social semiotics (Kress and van Leeuwen 2001), show that if artifacts like furniture have “meaning potential,” so do texts, whose materiality “contributes to their meaning potential; language and materiality work together, at different levels of semiosis” (Björkvall and Karlsson 2011: 143). Finally, theorists such as Law (2009, 2019), Latour (2005), and Beetz (2016) advocate for “material semiotics,” which conceptualizes meaning as relational and performative, enacted within networks of human and non-human actors. This article advances a proposal to articulate the material and semiotic dimensions of mediatization processes.

This article is organized as follows: Section 3 deals with the use of formal models in theory building processes. Section 4 opens with an introduction to Harold Innis’ pioneering contribution to the understanding of the material dimension of communication and continues with a brief description of how mediatization theories have dealt with materialities. Section 5 introduces the model based on the “states” of mediatization. The model is exemplified with a series of cases from the mediatization of war. In other words, the model will be used to create an analytical framework to compare and analyze different processes of mediatization over time, like the mediatization of World War II in newspapers, the mediatization of the Gulf War on TV, and the current mediatization of the invasion of Ukraine in social media such as TikTok. Finally, the last section summarizes the main arguments of the article and reflects on the different processes that can be identified within the proposed theoretical model.

Why choose to exemplify the different “material states” of mediatization with wars? Because, like many other institutions, and like education, politics and religion, war has also gone through an accelerated mediatization process. By the turn of the twenty-first century, media had emerged as “the ‘Fourth Branch’ of military operations (beyond the army, air force, and navy)” (Horten 2011: 32). As the research on mediatization of war has been intensive in recent years (e.g., Cornelissen and Mondini 2021; Hoskins and O’Loughlin 2010, 2015), it is not difficult to find cases for exemplifying the different states of mediatization. In this context, the application of the “material states” model to war mediatization processes will facilitate identifying the pertinent traits of these processes and comparing them from an integrated perspective. The final objective of the article is to present a model for classifying and analyzing mediatization processes and, at the same time and based on the possible limits of this formal tool, to open a conversation on the material dimension of mediatizations and text circulation.

3 Formal models in theory building processes

The creation and application of models is one of scientists’ and theoreticians’ favorite resources (Swedberg 2014). Models are useful tools not only for synthesizing complex theoretical constructions, but also for facilitating the understanding and dissemination of a theory even beyond its discipline of origin. In the field of social sciences, structuralism has been responsible for making modelling a fundamental theoretical tool. This interest expressed by structuralism can be very useful for thinking about the different forms that mediatization processes may take, not only at the present time, but also from a long-term evolutionary perspective. In the preface to Jakobson’s Six Lectures on Sound and Meaning, Lévi-Strauss described the significance of structural thinking for his work:

What I was to learn from structural linguistics was that instead of losing one’s way among the multitude of different terms, the important thing is to consider the simpler and more intelligible relations with which they are interconnected. (Lévi-Strauss in Jakobson 1978: xii)

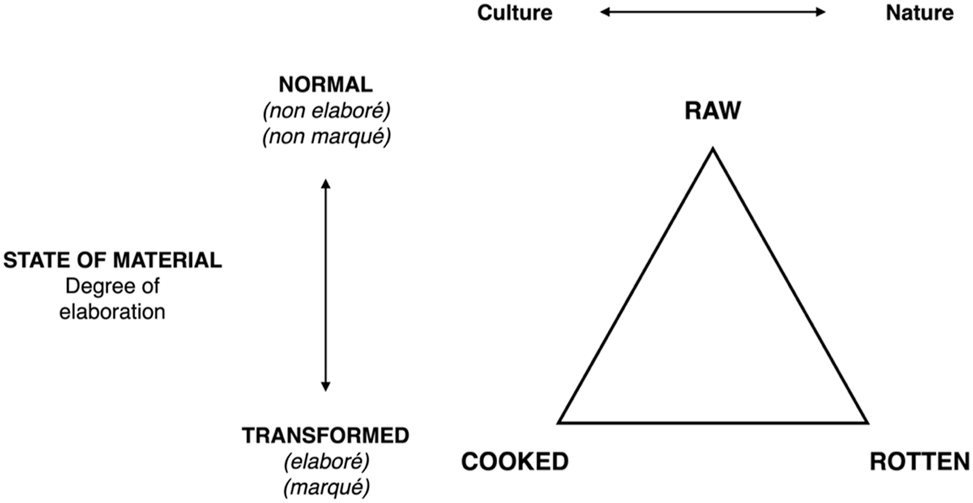

The interconnection of components was one of the key elements of structuralist thinking. Instead of analyzing single elements (phonemes, values, characters, etc.), what matters is their “reciprocal opposition within a phonological system” (Jakobson 1978: 76). Inspired by Jakobson’s “vowel triangle,” Lévi-Strauss proposed one of the most popular models of structuralism: the culinary triangle (Figure 1).

Culinary triangle (Lévi-Strauss 2008).

The model is a triangular semantic field with three positions that correspond to the categories of raw, cooked, and rotten. In cooking, the raw constitutes the unmarked pole, while the other two poles “are strongly marked, but in different directions: indeed, the cooked is a cultural transformation of the raw, whereas the rotted is a natural transformation.” Underlying the triangle, “there is hence a double opposition between elaborated/non-elaborated on the one hand, and culture/nature on the other” (Lévi-Strauss 2008: 29). According to Lévi-Strauss, the cooking of a society should be considered a “language in which it unconsciously translates its structures – or else resigns itself, still unconsciously, to revealing its contradictions” (2008: 35). This type of formal modelling proliferated in the structuralist universe and was applied to countless situations and cultural traditions. For example, Leach (1974) applied it to the traffic light system.

Although this is not the place to consider either the deserved or undeserved criticisms of structuralism (shooting against structuralism was a widespread sport from the late 1960s) (Giddens 1993; Pettit 1975; Ricœur 2004 [1969]), this approach has a virtue: its ability to “bring order to chaos” and give meaning to different types of cultural processes or social situations. In a few pages we will return to these formal models generated by the structuralist tradition.

4 Between media evolution, mediatization, and materialism

4.1 The material evolution of media

Rather than “social forces” or “class struggle,” in Empire and Communications (2007 [1950]) and The Bias of Communication (2008 [1951]) Harold Innis underscored the pivotal role of media as fundamental technologies that shape and influence the analysis of societal and political transformations. Innis’ initial focus on staples led him to examine pulp and paper production, which eventually directed his interest towards newspaper and book printing. In this shift, he moved from analyzing a natural resource-based industry to focusing the attention “to a cultural industry in which information, and ultimately knowledge, was a commodity that circulated, had value, and empowered those who controlled it” (Heyer 2006: 147). According to Innis, the effective governance of large areas “depends to a very important extent on the efficiency of communication” (2007 [1950]: 26). In this framework, the history of the West can be seen as divided into two major periods: the era of writing and the era of printing. Initially, the writing period was characterized by the use of materials such as clay and papyrus, which were later supplanted by parchment. The introduction of paper, brought from the East in the thirteenth century, marked a significant development. The subsequent printing period retained paper as the fundamental medium for textual production but revolutionized dissemination by introducing the first forms of industrial reproduction.

Innis’ exploration of the material supports of writing was closely intertwined with his emphasis on the temporal and spatial dimensions of media. He distinguished between space-binding and time-binding media. Space-binding media, such as papyrus, were lightweight, portable, and facilitated the extension of control and communication over vast distances. These media supported cultures focused on spatial concerns-ranging from land surveillance to voyages, imperial expansion, and governance. Conversely, time-binding media, like stone, were heavy, durable, and resistant to destruction, thus fostering cultures that prioritized continuity, history, religion, myths, and rituals. These cultures were more focused on preserving their knowledge and traditions across generations.

The core of Innis’ theory of cultural change resides in the intersection of political organization, the materiality of media, and the temporal and spatial dimensions:

The concepts of time and space reflect the significance of media to civilization. Media that emphasize time are those that are durable in character, such as parchment, clay, and stone. The heavy materials are suited to the development of architecture and sculpture. Media that emphasize space are apt to be less durable and light in character, such as papyrus and paper. The latter are suited to wide areas in administration and trade … Materials that emphasize time favour decentralization and hierarchical types of institutions, while those that emphasize space favour centralization and systems of government less hierarchical in character. (Innis 2007 [1950]: 27)

Recognizing the risks he faced – particularly the ever-present specter of technological determinism in such discussions – Innis promptly clarified that “it would be presumptuous to suggest that the written or the printed word has determined the course of civilizations” (2007 [1950]: 27), explicitly distancing himself from any form of media determinism. For Innis,

monopolies of knowledge had developed and declined partly in relation to [emphasis added] the medium of communication on which they were built, and tended to alternate as they emphasized religion, decentralization, and time, and force, centralization, and space. (Innis 2007 [1950]: 192)

Innis’ contributions provide a valuable foundation for analyzing the material dimension of mediatization. He emphasized the significance of the material medium of communication, arguing that it shapes a society’s conception of time and space, and profoundly influences the political structures that emerge within that society.

4.2 The material dimension of mediatizations

For Couldry and Hepp (2013) the concept of “mediatization” does not refer to a single theory but to a “more general approach within media and communication research” (2013: 197). In the European context, two intertwined approaches have dominated the theoretical conversations on mediatization: the “institutionalist” and “social-constructivist” traditions. Hepp (2013) synthesized them as follows:

Both differ in their focus on how to theorize mediatization: while the ‘institutional tradition’ has until recently mainly been interested in traditional mass media, whose influence is described as a ‘media logic’, the ‘social-constructivist tradition’ is more interested in everyday communication practices – especially related to digital media and personal communication – and focuses on the changing communicative construction of culture and society. (Hepp 2013: 616)

As already indicated, for Lundby (2014b) it is possible to include a “third material perspective.” According to him, some authors:

neither fit easily under a cultural perspective nor under an institutional one. Finnemann (2014) clearly opposes the cultural as well as the institutional perspective in his defence for what I term a material perspective. It is characterized by a focus on the material properties of the media in processes of mediatization. This perspective underlines that media are always materialized. The material aspect may be related to the particular communication technologies at stake. As such, this perspective comes close to (Joshua Meyrowitz’s) “medium theory.” (Lundby 2014b: 11)

In recent years researchers like Jansson (2014, 2016) and Couldry and Hepp (2017) have dealt with the material dimension of mediatization processes. In both cases the reflection was inspired by Williams’ (1980) concept of ‘cultural materialism’.

Cultural materialism implicates an understanding of mediatization as a transformational force that is inseparable from, rather than external to, the textures of everyday life. It is a perspective that helps us address two recurring problems in mediatization theory. Firstly, it helps us discern where mediatization ‘begins’, which is essentially a response to the dilemma of identifying what is not mediatization in the realm of culture and everyday life. (Jansson 2016: 2)

Working in a similar theoretical framework, Couldry and Hepp (2017) developed the idea of “materialist phenomenology” to emphasize that “it is fundamental for any analysis of media and communication to consider both the material and the symbolic” dimensions (Hepp 2020: 9). The materiality of communication does not only concern devices, cable networks and satellites:

Since today’s media are largely software-based, it is important to consider that complex tasks can and most likely will be ‘moved’ to algorithms. It is necessary, therefore, to think much more rigorously about the materiality of media and to also pose questions on which kind of agency is involved and at what times. A materialist phenomenology scrutinizes media technologies and infrastructures through and on the basis of contemporary communications. (Hepp 2020: 10)

On the Latin American front, the theoretical reflection on mediatization was dominated by the semio-discursive approach developed by Verón (1987, 1997, 2013, 2014). In tune with Krotz’s (2014) long-term vision, according to Verón (2013, 2014) mediatization started with human culture, when advanced anthropoids created the first stone tools, that is, the first mediatic phenomenon of Homo sapiens. Verón considered that mediatization designates “not just a modern, basically twentieth-century development, but a long-term historical process resulting from the Sapiens’ capability of semiosis” (2014: 163). This exteriorization of mental processes through material devices opened the road to more complex mediatization practices also based on the autonomy of the materialized signs from the sender to receivers, the persistence in time of those signs and the development of a set of social norms around them. In this context,

mediatization is just the name for the long historical sequence of mediatic phenomena being institutionalized in human societies, and its multiple consequences … What is happening in societies of late modernity began in fact a long time ago. (Verón 2014: 165)

According to Verón, the emergence of a medium produces “radial effects” that generate “an enormous network of feedback relationships: mediatic phenomena are clearly non-linear processes, typically far from equilibrium” (2014: 165). He also evidenced periodic accelerations of historical time, for example when, in the Upper Paleolithic, the production of stone tools went from twenty basic types to two hundred varieties, or when Gutenberg’s printing machine multiplied the number of books and changed European society profoundly in a couple of centuries.

Verón dedicated his last extended theoretical contribution, La Semiosis Social 2 (2013), to exploring further the expansion of mediatization, starting from a very remote past and focusing on the material dimension of these processes:

A conversation would be the clearest example of ‘unmediated’ communication. However, the sound waves of spoken language are a material support like a television screen. It is clear, then, that it is not possible to imagine a communication process without the production of a material, sensitive event, differentiated from both the source and the destination. (Verón 2013: 143–44)

The autonomization of the message and its greater or lesser persistence over time are two key aspects of these processes. According to Verón, writing was the “first autonomous medium in the history of linguistic communication” (2013: 145). However, the “materiality that makes the autonomy and persistence of signs possible” needs “the intervention of more or less complex technical operations, and the fabrication of a support” (2013: 146). For Verón “mediatization, in the context of the evolution of the species, is the sequence of historical media phenomena that result from certain materializations of the semiosis, obtained by technical procedures” (2013: 147).

Unlike other theoreticians, who tend to fix the origin of mediatization processes in modernity or late modernity, for Verón the first mediatization phenomenon was the production of stone tools during the “pebble culture” in the Lower Pleistocene (1.8 million to 600,000 years ago). The production of the stone tools “was the first materialization of mental processes endowed, therefore, with autonomy and persistence” (2013: 176). Materiality is also very present in the following chapters of La Semiosis Social 2 (2013), in which Verón analyses the first written mediatizations through papyrus and codex, and the emergence of photography in the nineteenth century.

5 The three states of mediatization: a model

If the reflection starts by considering that there are different ways of ‘materializing’ mediatization, then the next step could be to identify some specific “states” of these processes. Inspired by the works of pioneers of Media Ecology (from Lewis Mumford and Harold Innis to Marshall McLuhan and Walter Ong), scholars like Joshua Meyrowitz (2010) have proposed a model of media and cultural evolution based on four phases (Table 1).

Phases of media and communication evolution (Meyrowitz 2010).

| Phases |

|---|

| Traditional oral cultures |

| The transitional scribal phase |

| Modern print culture |

| Postmodern global electronic culture |

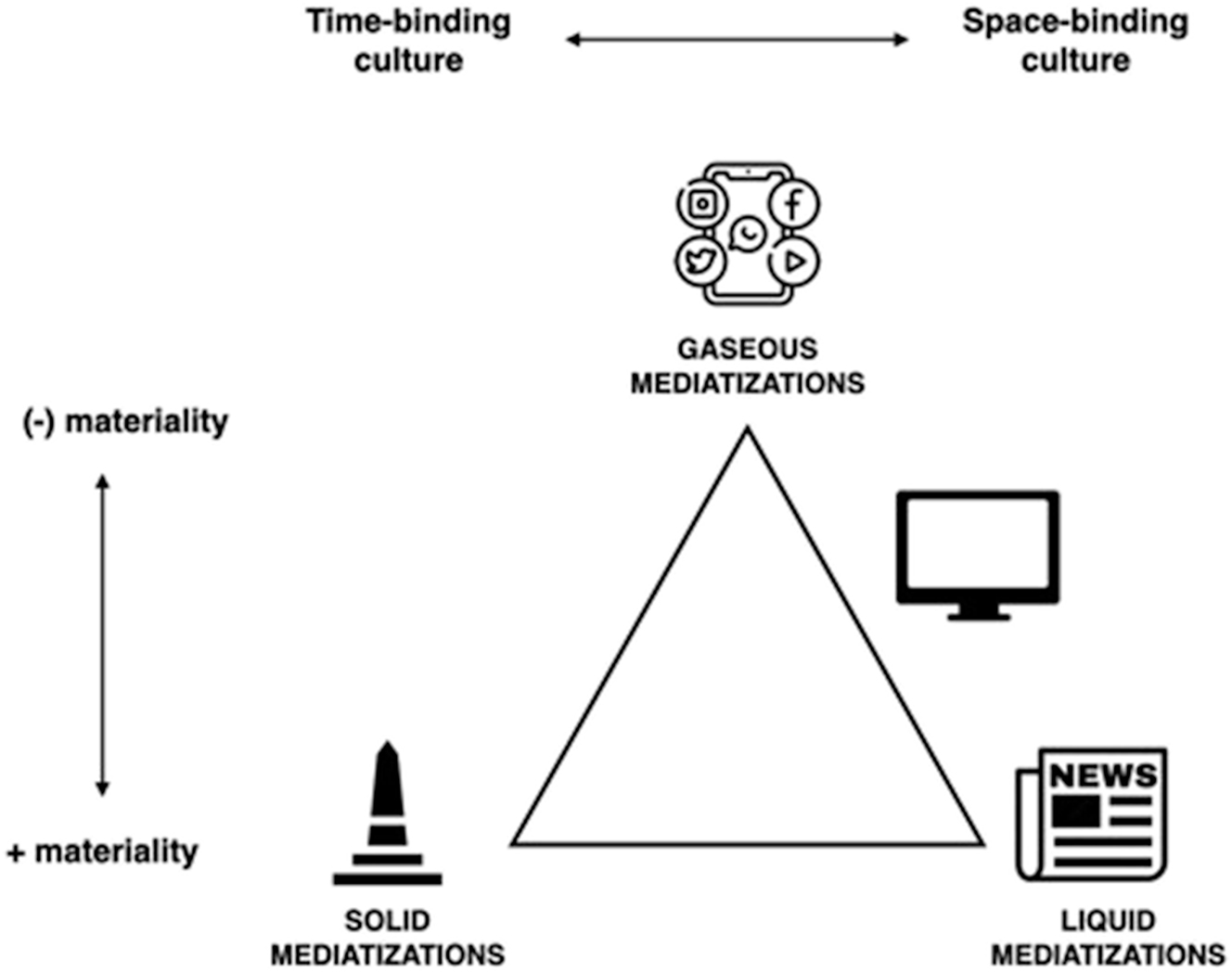

The approach based on the three states of mediatization moves away from these sequential models, based on identifying “phases,” to identify “states” of mediatization. If we return to the triadic model of Lévi-Strauss presented in the first section and project it onto mediatization processes from a material perspective, then three positions emerge (Figure 2). To better explain the model, as indicated in the Introduction, the three positions will be described with examples from the mediatization of war.

The three states of mediatization.

5.1 Solid mediatizations

Solid mediatizations express themselves in rigid and durable supports. This type of mediatization not only embraces religious, legal, and political texts written on stone, like the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi composed on a basalt between 1755 and 1750 BC: following Verón’s broad materialist vision of mediatizations, it also includes sculptures, monuments, war memorials, and all kinds of signs designed and produced to last over time. In this case, Innis would have talked about “time-binding media,” that is, media that promote hierarchical types of institutions made with the idea that they will last in the future. The keywords of this state of mediatization are solidity, sedentism, materiality, and eternity.

War memorials are a good example of the solid mediatization of war that runs through the history of humanity until today. One of the oldest war memorials was built in Syria, on a more than 4,000-year-old artificial mound, the White Monument at Tell Banat (Porter et al. 2021). One of the latest monuments inaugurated was The Iraq and Afghanistan Memorial in London, a memorial unveiled on March 9, 2017 by Queen Elizabeth II that commemorates British military personnel and civilians who participated in the Gulf War, the Afghanistan War and the Iraq War. But the solid mediatization of war also includes other expressions and intersects with other mediatizations. For example, the mediatization of war (that is, the mediatization of the battles, heroes, and sacrifices) is strongly connected to the mediatization of national values. The research by Smith (2017) is very suggestive about how objects mediate nationhood in Germany. Instead of focusing on colossal monuments, such as the Hermann Monument in the Teutoburg Forest (1875), the Germania Monument near Rüdesheim (1883), or the Barbarossa Monument in the Kyffhäuser Mountains (1896), Smith analyzed the pervasiveness of veteran monuments, Kaiser Wilhelm monuments, Bismarck monuments, as well as monuments to Germany’s great intellectuals. Focusing on local events and objects, Smith found that the mediatization of German nationhood had expanded to many other media and everyday objects:

As with veterans and Kaiser Wilhelm memorials, monuments to local heroes found their way onto postcards, plates, napkins, and silver spoons. A sense of local pride mixed with a claim on the national, as monuments and objects asserted that the national canon of great men and women ought to include hometown poets, philosophers, composers, and painters. (Smith 2017: 339)

Smith concluded that the proliferation of monuments in Imperial Germany suggests that “the national imaginary brought together in bric-a-brac fashion elements from the local and the national”; at the same time, the mediatization of the national “worked as much through monuments, festivals, and objects as through ideology”; finally, the author found that the aggressiveness of expressions at the national level “may not always have found clear echoes at the local level” (Smith 2017: 339).

As they are based on texts in which their very materiality guarantees a long future life (like in memorials and other monuments), solid mediatizations dialogue perfectly with war and national values and time-binding cultures that have a predominant interest in history, religion, myths, and rituals. Being honored annually, the great monuments ensure the ritual repetition of the mythical story that saw them born in the past and project them into the future.

5.2 Liquid mediatizations

Using the liquid metaphor in social sciences implies necessarily returning to Zygmunt Bauman’s ideas about modernity but without abandoning Innis’ basic opposition between space-binding media and time-binding media. By a space-binding culture Innis meant a culture with a predominant interest in space, from land surveillance to voyages, imperial expansion, and control. Media that emphasize space like papyrus and paper are suited to the management of complex areas in administration and commerce. The keywords of this state of mediatization are transportability, flow, controlled circulation, and progressive dematerialization.

For Bauman, modernity was born under the “stars of acceleration and land conquest,” and these stars are

a constellation which contains all the information about its character, conduct and fate … The relation between time and space was to be from now on processual, mutable, and dynamic, not preordained and stagnant. The ‘conquest of space’ came to mean faster machines. Accelerated movement meant larger space, and accelerating the moves was the sole means of enlarging the space. In this chase, spatial expansion was the name of the game and space was the stake; space was value, time was the tool. (Bauman 2000: 112–13)

Liquid mediatizations were first expressed in ancient flexible and transportable media such as papyrus, but they started acquiring a dominant position on a global scale with the spread of mechanical printing on paper from the fifteenth century. According to McLuhan (1997), in the same way that the medieval clock made Newtonian physics possible, Gutenberg’s invention

made possible the rectilinear page of print created from movable type, as well as the methods of commerce. At any rate the mechanization of writing was as revolutionary in its consequences as the mechanization of time. And this, quite apart from thoughts or ideas conveyed by the printed page. Movable type was already the modern assembly line in embryo. (McLuhan 1997 [1956]: 295)

The introduction of the steam-powered double-cylinder printing press in the early 19th century consolidated mediatization processes based on a short-lived media materiality that, unlike solid mediatizations, was not originally destined to last over time. The life cycle of a printed newspaper is 24 h, and that of a weekly publication, seven days.

We associate ‘lightness’ or ‘weightlessness’ with mobility and inconstancy: we know from practice that the lighter we travel the easier and faster we move. These are reasons to consider ‘fluidity’ or ‘liquidity’ as fitting metaphors when we wish to grasp the nature of the present, in many ways novel, phase in the history of modernity. (Bauman 2000: 2)

It could be said that the passing from a solid to a liquid mediatization is characterized by a progressive “lightening” of the material support of the communication (from stone or metal to paper) and a greater rotation of the content (with the consequent shorter life cycle of the media content). As Bauman put it, “the ‘short term’ has replaced the ‘long term’ and made of instantaneity its ultimate ideal” (2000: 125).

This process deepened in the twentieth century with the emergence of electronic media like radio and television: both the loss of materiality (from paper to audio-visual magnetic tapes and electromagnetic waves) and the reduction of the content lifecycle were two distinctive features of this process. In electronic media, contents are broadcast seamlessly, with no break in continuity. It is no coincidence that the concept of flow became part of the scientific debate on television consumption practices in the 1970s: as Williams (2004 [1974]: 86) put it, flow is “the defining characteristic of broadcasting, simultaneously as a technology and as a cultural form.”

If the solid mediatization of war was based on monuments and war memorials (that is, a storytelling of the past in tune with time-binding media like stone and metal), then the liquid mediatization of war runs parallel to the development of newspapers and electronic media in the last two hundred years. When the American Civil War (1861–1865) was fought, both the newspapers and the telegraph were established media that had coevolved in the previous decades (Scolari 2023). Newspaper coverage of the conflict included details of battles and military campaigns, political controversies, illustrations drawn on site or based on photographs, editorials, maps, and eyewitness accounts of events. This description by Plum (1882) depicts very well the situation and tensions between the different actors involved:

The telegraph was busy everywhere. Business was regulated by the ebb and flow of the Union fortunes. Newspapers in those days were very largely composed of telegrams and telegraphic correspondence, but at this time when every hour was pregnant with great events, only government messages had the right to wire. In the expressive language of operators, the lines were kept ‘red-hot’ with military despatches. Death messages were rushed through, not to say smuggled, whenever possible, but ordinary business and reports for the press were delayed hours after the contending armies were silent in sleep. Offers to bribe operators to prefer one press report over another were not unknown. The newspaper rivalry became very great. This was natural, as every hour brought news more dire than the preceding, and millions of men and women were seeking to allay their fears by telegraphic reports. (Plum 1882: 14)

The emergence of new media such as cinema and radio expanded the mediatization of war. According to Horten (2011), the First World War (1914–1918) saw the development of large propaganda organizations in all combatant countries. Due to the vast expansion of newspapers and magazines, as well as the development of film and radio broadcasting, “government agencies were able to disseminate their propaganda swiftly and effectively” (2011: 4). Both the professionalization of content production and strict censorship characterized the mediatization during World War I, a process that was further heightened and perfected during World War II (1939–45):

Hitler’s use of propaganda and the media are well known. In the United States as well, news censorship flourished even as new information modes such as live overseas broadcasts became feasible. More often than not, American propaganda was privatized, carried out by commercial advertising and media professionals and seamlessly inserted into radio broadcasts, mainstream films and popular magazines. (Horten 2011: 5)

The Vietnam War (1955–1975) became the first televised war of modern history. The coverage of this conflict “often read like a morality play, pitting good, selfless Americans defending South Vietnamese and worldwide freedom against conniving, fanatical Vietcong fighters” (Horten 2011: 34). Since the Tet Offensive of early 1968, the media followed and reflected an increasing trend that eroded the support for the war:

The fighting was savage and, unlike the pictures of American bombing runs, highly personalized. Some of these images literally went around the world, and television commentators accompanied them with harsh criticisms of the Johnson administration. (Horten 2011: 35–36)

The hegemony of television did not imply the disappearance of other forms of mediatization. Although it was fought at a time that television had full hegemony, the conflict that look place in a distant and inaccessible scenario, the war over the Malvinas/Falkland Islands between Argentina and the United Kingdom (1982), was mainly mediatized by printed media (Escudero Chauvel 1996).

If Vietnam was the first televised war, then the Gulf War (1990–1991) was “the first live television war” (Horten 2011: 38). The main limitation of this war was that “there was very little live TV coverage of actual fighting because reporters were effectively barred from the battlefield”: neither the American nor Iraqi soldiers and civilian population were depicted. The prime-time live TV coverage was dominated by footage of bombs illuminating the Baghdad night sky and meticulous smart bombs hitting their targets without fail. For Hoskins and O’Loughlin (2015), the 1990s saw

the final stage of broadcast era war. National and satellite television and the press had a lock on what mass audiences witnessed, and governments could exercise relative control of journalists’ access and reporting. (Hoskins and O’Loughlin 2015: 1320)

To conclude this overview of the liquid mediatization of war, it should be remembered that the passing from a printed paper-centered mediatization of war to Hertzian waves coincided with Bauman’s transition from the “era of hardware,” or “heavy modernity,” to “software capitalism” and “light modernity” (2000: 113–18). This transition from a “heavy” (printed) to “light” (audio-visual) mediatization of war anticipated a new state radically different from solid and liquid mediatizations.

The Gulf War of 1991 was the last war in which the military could effectively control the media and almost completely dominate international coverage. In the media environment of the 21st century, this level of military censorship is no longer possible. In little more than ten years, mediatization took a quantum leap forward, largely due to the development of the internet and social media, new cell phone and satellite technology, as well as the emergence of global rival news networks. As a result, mediatized war would never be the same. (Horten 2011: 39)

Many authors agree that the post-9/11 “war on terror” was the conflict that opened a new phase in the mediatization of war. Hoskins and O’Loughlin (2010) talk about the “emergence of Diffused War,” a new phase after Broadcast War supported by the mass internet penetration and the circulation of user-generated contents, while Horten (2011) considered that the Iraq War (2003–2011) represented “a new chapter in the mediatization of the war because the media indeed functioned increasingly as the fourth branch of military operations” (2011: 43).[1] From the perspective of the states of mediatization, the Iraq War could be considered as a ‘hybrid conflict’ where the typical aspects of liquid mediatization coexisted with new emerging forms of mediatization. This conflict was the first one to express a tension between the control of the mediasphere and the explosion of online alternative news sources and user-generated contents that the military tried to absorb and redirect.

Many of the traits already present in the post-9/11 ‘war on terror’ became consolidated in the following years to give shape to a new state of mediatization. Contemporary conflicts like the Syrian Civil War (2011–present) and the Russo-Ukrainian War (2014–present) are being fought in a fully digitalized media ecosystem that includes a broad spectrum of new actors, media, contents, and practices. It is in this context that a new state emerges: gaseous mediatizations.

5.3 Gaseous mediatizations

The new spaces of digital mediatization (World Wide Web, social networks, mobile applications, platforms) have done nothing more than take on the latest consequences of the dematerializing logic that was already operating in printed and audio-visual liquid mediatizations. In terms of the content lifespan, since the twenty-four-hour cycle imposed by newspapers in the early nineteenth century, we have moved on to the ephemeral and minimal content consumption of the “snack culture” (Scolari 2020). If a printed newspaper lasted 24 h, then a micro video on TikTok of a Russian tank blowing up on the Ukrainian front is consumed immediately and disappears in an infinite and boundless audio-visual ocean. In this state of mediatization, the keywords are virality, acceleration, fragmentation, ephemerality, and radical dematerialization.

If during the Iraq War warblogs were widespread and “no government or military, not even the Pentagon, can any longer control the visual imagery of war” (Horten 2011: 44), then in contemporary conflicts social media like Telegram or audio-visual platforms like YouTube and TikTok have positioned themselves at the center of the mediatization process, even affecting traditional liquid media.

‘Social media’ in the broadest sense, therefore, has become central to wars and conflicts, imploding with the event, to simultaneously capture it, promote it, denounce it, deny it, spread images, videos, bloopers, memes, jokes, graphics, gifs, and comments, help organise it, raise funds, raise awareness, accrue new recruits, direct combat operations, spread disinformation and propaganda, and rally aid and help for its victims. (Merrin and Hoskins 2020: 6)

Contemporary gaseous mediatization of war has broken the almost complete monopoly of information that characterized the liquid mediatization of previous conflicts (like the Gulf War), when the State and the armed forces were relatively successful in achieving control over war news production. The massive production of brief user-generated audio-visual contents from the war front and the acceleration of the circulation of these contents inaugurates a new way of mediatizing the conflict. In this context social media can make their influence felt in parliamentary debates (Herrero-Jiménez et al. 2018) or be integrated into the official communication strategy of the armed forces (Shim and Stengel 2017).

In this new media ecosystem where broadcasting (liquid) media coexist with (solid) memories of past wars and (gaseous) social media and platforms, mediatization is not just a “process” but a “configuration” that emerges from the interactions of a dense network of human, institutional, technological, and textual actors. The tensions between actors are permanent: if the official policy of armed forces is not to share images that show human suffering – like the antimilitarist “way of seeing” detected by Shim and Stengel (2017) in the German representation of the Afghanistan operation on Facebook – user-generated contents introduce other versions of the conflict and generate “noise” in the official discourses. For example, in the first years of the Russo-Ukrainian War,

the use of social media for visual framing of the war in Donbas facilitated construction of different and often mutually exclusive views on the conflict in Eastern Ukraine among pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian internet users. Unlike pro-Ukrainian users, who presented the conflict in Eastern Ukraine as a limited military action against local insurgents, pro-Russian users interpreted it as an all-out war initiated by an extremist Ukrainian government. Consequently, the propagation of such contradictory interpretations has led to the formation of different views on the nature of the conflict as well as divergent expectations concerning the outcome of the war in Donbas. (Makhortykh and Sydorova 2017: 377)

Other studies have confirmed that in this hybrid media ecosystem (Chadwick 2017) the relationships between mainstream media journalists, “citizen journalists” who produce user-generated contents, and the discourse strategies of the armed forces are not always harmonious (Pantti 2016; Storck 2014). This “gaseous” communicational environment, characterized by a boisterous textual circulation, is the space where memetic forms of disinformation proliferate (such as fake news).

Should gaseous mediatizations be considered as a brand new mediatization of war? No, not at all. Perhaps the closest antecedent to gaseous mediatizations are the old oral forms of communication. Scholars like Havelock (1963) and Ong (1977, 2012 [1982]) have extensively analyzed the characteristics of oral societies and the slow transition to writing. For Ong, oral speech:

is inseparable from our consciousness and it has fascinated human beings, elicited serious reflection about itself, from the very early stages of consciousness, long before writing came into existence. Proverbs from all over the world are rich with observations about this overwhelmingly human phenomenon of speech in its native oral form, about its powers, its beauties, its dangers. (Ong 2012 [1982]: 9)

Human communication before writing was gaseous. There was no material support (beyond the air) to sustain the interpersonal exchanges and fix the contents. A stabilization of the message was impossible. Mnemonic patterns and formulas were the antidote to the ephemeral nature of oral communication. In a primary oral culture, “to solve effectively the problem of retaining and retrieving carefully articulated thought, you have to do your thinking in mnemonic patterns, shaped for ready oral recurrence” (Ong 2012 [1982]: 34). This ephemeral and almost immaterial character of traditional oral exchanges is very similar to contemporary digital communications in media such as TikTok, YouTube and Instagram.[2]

The most famous war of ancient times was initially mediatized through oral communication. As Havelock noted in Preface to Plato (1963), Homer’s Iliad was a written version of a narrative originally developed in an oral community:

In the Homeric or pre-Homeric period, say between twelve hundred and seven hundred, any written version was impossible … Preservation of such a corpus had to rely on the living memories of human beings, and if these were to be effective in maintaining the tradition in a stable form, the human beings must be assisted in their memorization of the living word by every possible mnemonic device which could print this word indelibly upon the consciousness. (Havelock 1963: 291)

According to Havelock, Homer and other poets formed in the oral tradition of Hesiod represented “a whole state of the Greek mind.” Through their formulaic style, they were “speaking in the only idiom of which their whole culture was capable” (Havelock 1963: 138).

6 Discussion and conclusions

In this article I have introduced a model inspired by the structuralist tradition to frame the material dimension of war mediatizations. The model could be applied to any kind of mediatization process, from politics to sport and religion. In any case, the model should not be considered as a rigid taxonomy but rather as a tool for interpreting mediatizations from a material perspective and analyzing specific traits of these processes.

Unlike the models of Meyrowitz (2010) or Hoskins and O’Loughlin (2010, 2015), the “states of mediatization” are not a sequence of “moments” or “phases,” but rather a set of configurations that usually occur simultaneously. In other words, when one state becomes dominant, the others do not disappear. Contemporary wars like the conflict in Ukraine are deeply mediatized on emerging gaseous media like TikTok and Telegram, but they are still present in liquid media such as television; and in the future, these wars will also generate new solid monuments to remember their victims. What is necessary to understand is that the three states, except in specific moments of human evolution (for example, before the invention of writing), never appear alone or isolated.

The states of mediatization, therefore, are not motionless: like in physical environments it is possible to identify transitions and displacements inside each state and between them, for example, the already mentioned passing from a “heavy (printed) modernity” to a “light (audio-visual) modernity” in the liquid state of mediatization, or the transformation of a solid mediatization (a war memorial) into a piece of liquid mediatization (a postcard) or even a gaseous one (a selfie in Instagram).

If we introduce the time variable, what emerges is that solid mediatizations were designed to remember the past in the future, while liquid mediatizations were perfected to mediatize ongoing conflicts. It is in this context that we can talk about “acceleration”: the printed mediatizations of the nineteenth century worked on a twenty-four-hour lifecycle (the newspaper), while twentieth-century broadcasting mediatizations (radio and television) danced the faster rhythm of “breaking news.” Gaseous mediatizations play the game of digital “real time” communication; as they are not designed to last into the future, present tense seems to be “the only time of which our whole culture is capable” of speaking.

However, it should be remembered that the material dimension is always present in mediatization processes: even the most gaseous mediatizations are based on a concrete network of infrastructures (cables, satellites, server farms, etc.) with a high ecological negative impact on the planet (Crawford 2021). One of the possible limitations of the ‘three states of mediatization’ model is that it could lead one to think that “gaseous” mediatizations circulate in the ‘cloud’ without any material technological infrastructure. Nothing is further from reality.

As it can be seen, the model of the three states allows researchers to analyze and reflect on mediatization processes from a renewed perspective that places materiality at the center of the theoretical conversation. On one hand, the model permits us to take a distance from the sequences implicit in the lineal model of the “phases” (which are not to be discarded, since they fulfil other theoretical functions); on the other hand, the three states model allows us to identify common features, hybridizations, and tensions between the different forms of mediatization.

References

Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid modernity. Cambridge: Polity.Suche in Google Scholar

Beetz, Johannes. 2016. Materiality and subject in Marxism, (post-)structuralism, and material semiotics. London: Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/978-1-137-59837-0Suche in Google Scholar

Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant matter. Durham, NC & London: Duke University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Bennett, Tony & Patrick Joyce. 2010. Material powers: Cultural studies, history, and the material turn. London & New York, NY: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Björkvall, Anders & Anna-Malin Karlsson. 2011. The materiality of discourses and the semiotics of materials: A social perspective. Semiotica 187(1/4). 141–165.10.1515/semi.2011.068Suche in Google Scholar

Bollmer, Grant. 2019. Materialist media theory. London & New York: Bloomsbury Academic.10.5040/9781501337086Suche in Google Scholar

Carlón, Mario. 2015. La concepción evolutiva en el desarrollo de la ecología de los medios y en la teoría de la mediatización: ¿la hora de una teoría general? Palabra Clave 18(4). 1111–1136.10.5294/pacla.2015.18.4.7Suche in Google Scholar

Carlón, Mario. 2018. ¿Cómo seguir? La teoría veroniana y las nuevas condiciones de circulación del sentido. DeSignis 37. 145–155. https://doi.org/10.35659/designis.i29p145-155.Suche in Google Scholar

Carlón, Mario. 2022. ¿El fin de la invisibilidad de la circulación del sentido de la mediatización contemporánea? DeSignis 37. 245–253. https://doi.org/10.35659/designis.i37p245-253.Suche in Google Scholar

Chadwick, Andrew. 2017. The hybrid media system: Politics and power. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780190696726.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Coole, Diana & Samantha Frost. 2010. New materialisms: Ontology, agency, and politics. Durham, NC & London: Duke University Press.10.2307/j.ctv11cw2wkSuche in Google Scholar

Cornelissen, Christoph & Marco Mondini. 2021. The mediatization of war and peace: The role of the media in political communication, narratives, and public memory (1914–1939). Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110707373Suche in Google Scholar

Couldry, Nick & Andreas Hepp. 2013. Conceptualizing mediatization: Contexts, traditions, arguments. Communication Theory 23. 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12019.Suche in Google Scholar

Couldry, Nick & Andreas Hepp. 2017. The mediated construction of reality. Cambridge: Polity Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Crawford, Kate. 2021. Atlas of AI. London: Yale University Press.10.12987/9780300252392Suche in Google Scholar

Escudero Chauvel, Lucrecia. 1996. Malvinas: El gran relato. Buenos Aires: Gedisa.Suche in Google Scholar

Fernández, José Luis. 2017. Las mediatizaciones y su materialidad: revisiones. In Mariana Patricia Busso & Mariángeles Camusso (eds.), Mediatizaciones en tensión: el atravesamiento de lo público, 10–29. Rosario: UNR Editora.Suche in Google Scholar

Fernández, José Luis. 2018. Plataformas mediáticas. Elementos de análisis y diseño de nuevas experiencias. Buenos Aires: La Crujía.Suche in Google Scholar

Fernández, José Luis. 2021. Vidas mediáticas. Entre lo masivo y lo individual. Buenos Aires: La Crujía.Suche in Google Scholar

Finnemann, Niels Ole. 2014. Digitization: New trajectories of mediatization? In Knut Lundby (ed.), Mediatization of communication, 316–321. Berlin & Boston: de Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110272215.297Suche in Google Scholar

Giddens, Anthony. 1993. New rules of sociological method: A positive critique of interpretative sociologies. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Grusin, Richard. 2015. The nonhuman turn. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Havelock, Eric. 1963. Preface to Plato. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.10.4159/9780674038431Suche in Google Scholar

Hepp, Andreas. 2013. The communicative figurations of mediatized worlds: Mediatization research in times of the “mediation of everything.” European Journal of Communication 28. 615–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323113501148.Suche in Google Scholar

Hepp, Andreas. 2020. Deep mediatization. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781351064903Suche in Google Scholar

Herrero-Jiménez, Beatriz, Adolfo Carratalá & Rosa Berganza. 2018. Violent conflicts and the new mediatization: The impact of social media on the European parliamentary agenda regarding the Syrian War. Communication & Society 31(3). 141–157.10.15581/003.31.3.141-155Suche in Google Scholar

Heyer, Paul. 2006. Harold Innis’ legacy in the media ecology tradition. In Casey Man Kong Lum (ed.), Perspectives on culture, technology and communication: The media ecology tradition, 143–161. New York, NY: Hampton Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Hjarvard, Stig. 2008. The mediatization of society: A theory of the media as agents of social and cultural change. Nordicom Review 29(2). 105–134. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0181.Suche in Google Scholar

Hjarvard, Stig. 2013. The mediatization of culture and society. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203155363Suche in Google Scholar

Hjarvard, Stig. 2014. Mediatization and cultural and social change: An institutional perspective. In Knut Lundby (ed.), Mediatization of communication, 199–226. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110272215.199Suche in Google Scholar

Horten, Gerd. 2011. The mediatization of war: A comparison of the American and German media coverage of the Vietnam and Iraq wars. American Journalism 28(4). 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/08821127.2011.10677801.Suche in Google Scholar

Hoskins, Andrew & Ben O’Loughlin. 2010. War and media: The emergence of diffused war. Cambridge: Polity Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Hoskins, Andrew & Ben O’Loughlin. 2015. Arrested war: The third phase of mediatization. Information, Communication & Society 18(11). 1320–1338. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2015.1068350.Suche in Google Scholar

Innis, Harold. 2007 [1950]. Empire and communications. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield.Suche in Google Scholar

Innis, Harold. 2008 [1951]. The bias of communication. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Jakobson, Roman. 1978. Six lectures on sound and meaning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Jansson, André. 2014. Indispensable things: On mediatization, materiality, and space. In Knut Lundby (ed.), Mediatization of communication, 273–295. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110272215.273Suche in Google Scholar

Jansson, André. 2016. Mediatization is ordinary: A cultural materialist view of mediatization. Paper presented at the sixty-sixth Annual ICA Conference, Fukuoka, Japan, June 9–13.Suche in Google Scholar

Keane, Webb. 2003. Semiotics and the social analysis of material things. Language & Communication 23(3–4). 409–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0271-5309(03)00010-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Kress, Gunther & Theo van Leeuwen. 2001. Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. London: Arnold.Suche in Google Scholar

Krotz, Friedrich. 2014. Mediatization as a mover in modernity: Social and cultural change in the context of media change. In Knut Lundby (ed.), Mediatization of communication, 131–162. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110272215.131Suche in Google Scholar

Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the social: An introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.10.1093/oso/9780199256044.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Law, John. 2009. Actor network theory and material semiotics. In Brian S. Turner (ed.), The New Blackwell companion to social theory, 141–158. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.10.1002/9781444304992.ch7Suche in Google Scholar

Law, John. 2019. Material semiotics. http://www.heterogeneities.net/publications/Law2019MaterialSemiotics.pdf (accessed 5 August 2025).Suche in Google Scholar

Leach, Edmund. 1974. Claude Lévi-Strauss. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 2008. The culinary triangle. In Carole Counihan & Penny Van Esterik (eds.), Food and culture: A reader, 36–43. New York, NY: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Lundby, Knut. 2009. Mediatization: Concept, changes, consequences. New York, NY: Peter Lang.Suche in Google Scholar

Lundby, Knut (ed.). 2014a. Mediatization of communication. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.Suche in Google Scholar

Lundby, Knut. 2014b. Mediatization of communication. In Knut Lundby (ed.), Mediatization of communication, 3–35. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110272215Suche in Google Scholar

Makhortykh, Mykola & Marina Sydorova. 2017. Social media and visual framing of the conflict in Eastern Ukraine. Media, War & Conflict 10(3). 359–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635217702539.Suche in Google Scholar

McLuhan, Marshall. 1997 [1956]. The media fit the Battle of Jericho. In Eric McLuhan & Frank Zingrone (eds.), Essential McLuhan, 287–306. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203992968Suche in Google Scholar

Merrin, William & Andrew Hoskins. 2020. Tweet fast and kill things: Digital war. Digital War 1. 184–193. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42984-020-00002-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Meyrowitz, Joshua. 2010. Media evolution and cultural change. In John R. Hall, Laura Grindstaff & Ming-Cheng Lo (eds.), Handbook of cultural sociology, 52–63. New York, NY: Routledge.Suche in Google Scholar

Ong, Walter. 1977. Interfaces of the word: Studies in the evolution of consciousness and culture. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Ong, Walter. 2012 [1982]. Orality and literacy. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203103258Suche in Google Scholar

Pantti, Mervi. 2016. Media and the Ukraine crisis. New York. NY: Peter Lang.10.3726/978-1-4539-1878-4Suche in Google Scholar

Parikka, Jussi. 2015. A geology of media. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.10.5749/minnesota/9780816695515.001.0001Suche in Google Scholar

Pettit, Philip. 1975. The concept of structuralism: A critical analysis. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Plum, William. 1882. The military telegraph during the Civil War in the United States. Chicago, IL: Jansen, McClurg.Suche in Google Scholar

Porter, Anne, Thomas McClellan, Susanne Wilhelm, Jill Weber, Alexandra Baldwin, Jean Colley, Brittany Enriquez, Meagan Jahrles, Bridget Lanois, Vladislav Malinov, Sumedh Ragavan, Alexandra Robins & Zarhuna Safi. 2021. “Their corpses will reach the base of heaven”: A third-millennium BC war memorial in northern Mesopotamia? Antiquity 95(382). 900–918. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2021.58.Suche in Google Scholar

Ricœur, Paul. 2004 [1969]. The conflict of interpretations: Essays in hermeneutics. London & New York, NY: Continuum.Suche in Google Scholar

Scolari, Carlos Alberto. 2020. Cultura snack. Buenos Aires: La Marca.Suche in Google Scholar

Scolari, Carlos Alberto. 2023. On the evolution of media: Understanding media change. London: Routledge.10.4324/9781003215233Suche in Google Scholar

Scolari, Carlos Alberto, José Luis Fernández & Joan Ramón Rodríguez-Amat. 2021. Mediatization(s): Theoretical conversations between Europe and Latin America. Bristol: Intellect.10.2307/j.ctv36xvs43Suche in Google Scholar

Scolari, Carlos Alberto & Joan Ramón Rodríguez-Amat. 2018. A Latin American approach to mediatization: Specificities and contributions to a global discussion about how the media shape contemporary societies. Communication Theory 28(2). 131–154. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtx004.Suche in Google Scholar

Shim, David & Frank Stengel. 2017. Social media, gender and the mediatization of war: Exploring the German armed forces’ visual representation of the Afghanistan operation on Facebook. Global Discourse 7(2–3). 330–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/23269995.2017.1337982.Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, Helmut. 2017. Monuments, kitsch, and the sense of nation in imperial Germany. Central European History 49. 322–340. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0008938916000868.Suche in Google Scholar

Storck, Madeline. 2014. Streaming the Syrian War: A case study of the partnership between professional and citizen journalists in the Syrian Conflict. London School of Economics and Political Science Master’s thesis.Suche in Google Scholar

Swedberg, Richard. 2014. The art of social theory. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Valdettaro, Sandra. 2021. Mediatization(s) studies. Rosario: UNR Editora.Suche in Google Scholar

Verón, Eliseo. 1987. La semiosis social. Fragmentos de una teoría de la discursividad. Buenos Aires: Gedisa.Suche in Google Scholar

Verón, Eliseo. 1997. Esquema para el análisis de la mediatización. Diálogos de la Comunicación 48. 9–17.Suche in Google Scholar

Verón, Eliseo. 2013. Ideas, momentos, interpretantes (La semiosis social 2). Buenos Aires: Paidós.Suche in Google Scholar

Verón, Eliseo. 2014. Mediatization theory: A semio-anthropological perspective. In Knut Lundby (ed.), Mediatization of communication, 163–172. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton.10.1515/9783110272215.163Suche in Google Scholar

Williams, Raymond. 1980. Problems in materialism and culture: Selected essays. London: New Left.Suche in Google Scholar

Williams, Raymond. 2004 [1974]. Television: Technology and cultural form. London: Routledge.10.4324/9780203426647Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- 10.1515/sem-2024-0112

- Peirce’s Universal Categories in the S3 symmetry group: an analysis of the basic color terms

- 10.1515/sem-2024-0134

- 10.1515/sem-2024-0130

- The three states of mediatization: the case of war mediatization

- Challenging linguicentrism in translation: a semiotic approach to the emergence of a female counterculture in digital spaces

- TV series and the unveiling of the unknown: a semiology of strangeness

- Performance as discourse: a multimodal perspective on meaning-making in theater

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- 10.1515/sem-2024-0112

- Peirce’s Universal Categories in the S3 symmetry group: an analysis of the basic color terms

- 10.1515/sem-2024-0134

- 10.1515/sem-2024-0130

- The three states of mediatization: the case of war mediatization

- Challenging linguicentrism in translation: a semiotic approach to the emergence of a female counterculture in digital spaces

- TV series and the unveiling of the unknown: a semiology of strangeness

- Performance as discourse: a multimodal perspective on meaning-making in theater