Abstract

The knowledge of the essential role of copper in the human body, especially in its involvement in various important metalloenzymes, such as cytochrome c oxidase, copper-zinc superoxide dismutase, tyrosinase, lysyl oxidase and other, has greatly stimulated research interest in copper coordination compounds from both chemical and medicinal perspectives. Dinuclear copper complexes, in particular, have shown considerable therapeutic potential, as the unique combination of copper chemistry and dinuclear structural modifications has given rise to various highly bioactive compounds and new medicinal possibilities. In this paper, biological activities of medicinally attractive homodinuclear and heterodinuclear copper complexes are reviewed and their therapeutic potential and future perspectives are discussed. An in-depth analysis of key elements that impact their structure-activity relationships was performed and through a rational design approach, supported by the available literature, concluding remarks were given, that could possibly lead to more optimal therapeutic dinuclear copper complex structures. Known limitations regarding copper toxicity, bioavailability, metabolism and clearance were analyzed and possible strategies to mitigate them were discussed as well, including the possibe use of dinuclear copper complexes in targeted therapy and stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems. Finally, the prospects of using dinuclear copper complexes in personalized or combination therapy are postulated.

1 Introduction

Drug discovery has been, for the longest time, heavily oriented towards mostly organic chemistry. 1 Most clinical candidates and new FDA (Food and Drug Administration) approved drugs each year are, in fact, small organic molecules. While this trend persists, it certainly leaves a substantial gap for metal complexes to fill, as they possess their own particular electronic and stereochemical properties. 2 Transition metal complexes, with their incomplete d-subshells, can exist in various oxidation states and can inhabit many different coordination environments, which include a large number of diverse ligands, substrates, bioactive molecules, natural products and biomacromolecules. Transition metal complexes have a long history of medicinal application in the treatment of various diseases and ailments. 3 Platinum complexes were used in chemotherapy, gold complexes for treating arthritis, iron complexes for anemia and porphyria, bismuth complexes for ulcers, silver complexes for microbial infections, technetium complexes for imaging, arsenic complexes for leukemia and zinc complexes for Wilson’s disease.

Copper, in particular, is an essential trace element that has been receiving a continuously growing amount of research attention ever since the solidification of its many biological roles and discovery of various copper-containing metalloenzymes. 4 Copper is involved in many biological processes and the importance of copper homeostasis is noted in a large body of research, particularly pertaining to its relation to iron transport and metabolism 5 , 6 and regulation of human physiology, biochemistry and pathology. 7

Copper, before everything else, has a long-standing historical relationship with humanity. It is among the most abundant transition metals and, more importantly, it is found in its pure, accessible, unalloyed form. The application of copper has propelled the advancement of humanity from the Stone Age to the Industrial Age and continues to be a heavily utilized staple in all technical and industrial sectors of modernity. 8 , 9 Exceptional electrical and thermal conductivity, superior malleability and ductility, excellent corrosion resistance, leading to long-term durability and high recyclability are some of the main reasons why copper is held in high esteem, compared to many other metals. 10 , 11

Copper primarily exists in two oxidation states, Cu(I) and Cu(II), and this redox flexibility allows diverse catalytic cycles, electron transfer processes and biological roles. Copper can readily switch between Cu(I) and Cu(II) under physiological conditions. This redox flexibility is crucial for key biological roles, such as electron transfer in respiration, radical detoxification and oxygen activation. Other biologically essential metals (for example, zinc, magnesium and calcium) are redox-inert and possess a more limited scope of function.

Copper possesses high chemical versatility and its coordination chemistry is rich, with an array of diverse coordination geometries. Copper(I) forms linear, trigonal planar and tetrahedral geometries, while copper(II) forms square planar, square pyramidal and distorted octahedral geometries. Also, the Jahn-Teller effect in Cu(II) complexes leads to a plethora of structural variations and reactivity patterns. This chemical versatility is responsible for its prevalence in various vital copper-dependent enzymes, such as cytochrome c oxidase, superoxide dismutase, tyrosinase, laccase and ceruloplasmin. Copper enzymes also contain mono-, di- and multicopper sites with different geometries and redox states. This structural and functional diversity far exceeds any other known biologically relevant metal. All of these properties underscore the relevance of copper and explain why it is biologically ubiquitous.

Although all transition metals are toxic at sufficient concentrations, 12 copper is considered to be among the least toxic, because copper levels are tightly regulated in cells. Organisms have evolved elaborate transport, storage and detoxification systems that regulate copper levels and ameliorate the effects of copper toxicity, such as high affinity copper uptake protein 1 (CTR1), copper-transporting P-type ATPases (ATP7A/B) and metallochaperones, such as cytochrome c oxidase copper chaperone (COX17), antioxidant 1 copper chaperone (ATOX1) and copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase (CCS).

Current trends in medicinal and bioinorganic chemistry hold copper complexes in high regard due to the plethora of biological activities that they exhibit, as well as their potential uses in medicine. 13 Some of the biological activities they possess include antimicrobial 14 , 15 (antibacterial 16 and antifungal 17 ), antiviral, 16 , 18 larvicidal, 19 anticancer, 20 , 21 antioxidant, 19 , 22 anti-inflammatory, 23 anticonvulsant, 24 anti-ulcer, 25 wound healing, 26 anticoagulant 27 and enzyme inhibition. 28 , 29 Copper complexes can also be applied, for example, in positron emission tomography, to monitor metabolic activity of cells, radioimmunological tracing and cancer radiotherapy. 30 Photodynamic therapy represents another exciting possibility for application of copper complexes, where treatment would involve light-sensitive, photoactive copper complexes, which would, upon illumination with a light source, interact with and inhibit or destroy abnormal cells. 31 , 32

In terms of biological activities and medicinal applications, dinuclear complexes introduce interesting possibilities and represent a hot topic in the field of bioinorganic chemistry. The addition of another coordination center can fundamentally change how a complex interacts with biomolecular targets. 33 This structural modification, with two metal coordination centers connected with either flexible or more rigid bridging ligands, can result in different intramolecular or intermolecular interactions with biomolecules, which can modulate biological activity. This is particularly interesting in the case of heterodinuclear complexes, where the presence of two different metal ions changes the balance between soft-hard acid-base relationships. This often results in the improvement of the biological activities that the metal ions would exhibit individually. 34

In this review, a thorough investigation of the various biological activities of homodinuclear and heterodinuclear copper complexes will be presented. Their therapeutic potential and potential applications in medicine will be discussed, while taking into consideration the current state of the art and future perspectives of these compounds, as well.

2 Dinuclear copper complexes as antimicrobial agents

Increasing antimicrobial drug resistance has become one of the major concerns of modern medicine. 35 This is particularly alarming since infectious diseases still pose as one of the primary causes of death globally. 36 This persisting trend is severely taxing for global medical and economic systems. For this reason, there is a great need for new, more effective drug-like compounds to combat this ongoing issue and hopefully, tip the scales towards resolution. Copper, in its many forms, is a natural antimicrobial agent and its antimicrobial properties have been used since ancient times, even though the very concept of microorganisms was not understood until the nineteenth century. 37

2.1 Antibacterial dinuclear copper complexes

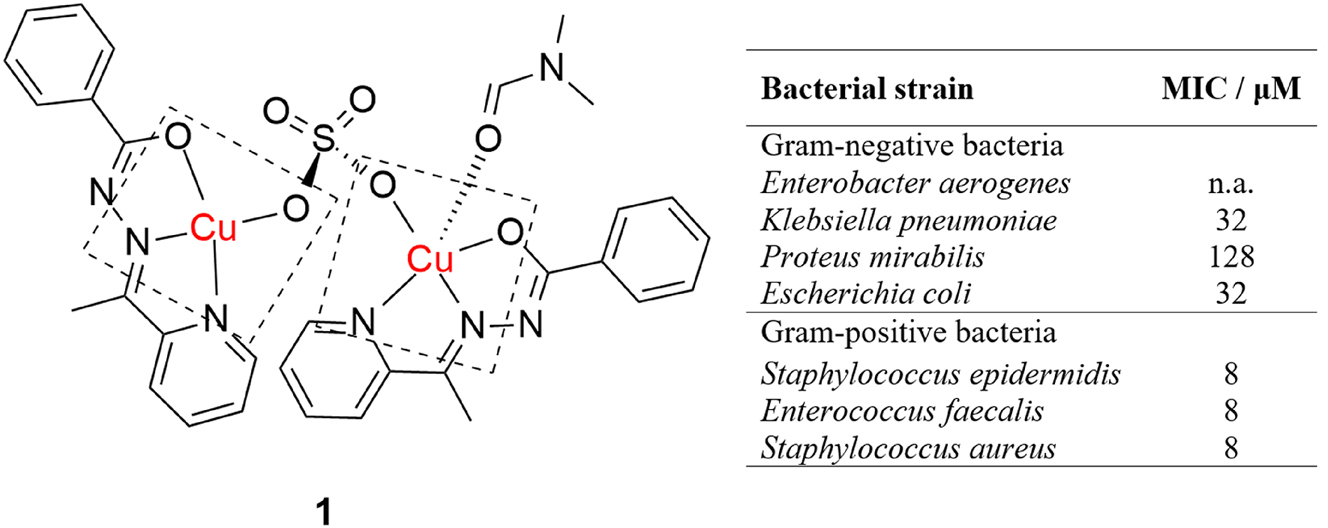

Copper(II) complexes have been screened intensively for antibacterial activity and dinuclear complexes, in particular, were shown to be promising antibacterial agents. 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 Santiago et al. reported a synthesis of a sulfate-bridged dinuclear copper(II) complex with the 2-acetylpyridinebenzoylhydrazone ligand (Figure 1, complex 1). 44 The complex has N,N-dimethylformamide coordinated to only one of the copper(II) ions, resulting in different geometries of the coordination centers. One copper atom is five-coordinated, with a distorted square pyramidal geometry, while the other has a distorted square planar geometry. Antimicrobial activities of the complex were tested on seven bacterial and two fungal strains and it exhibited moderate across-the-board antimicrobial activity, while being particularly active against Gram-positive bacteria, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Enterococcus faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus. The reduced activity against Gram-negative bacteria is proposed to be due to more complex cellular structures, thus requiring better membrane-penetrating properties.

Antibacterial activity of a mixed homodinuclear hydrazone copper complex.

Another dinuclear copper(II) complex, synthesized from pyrazole-3,5-dicarboxylic acid by Soltani et al., exhibited high antibacterial activity (Figure 2, complex 2). 45 Antibacterial activity of the complex was examined on a panel of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and it showed good overall activity, while being more active against the Gram-negative Escherichia coli, according to the OD600 assay. The complex has a square planar geometry, with a water molecule in the axial position in the crystal structure, which would be free in the aqueous medium. This free site is proposed to provide better contact with the bacteria, thus exhibiting antibacterial activity through ROS generation via the suggested site contact mechanism.

Structures and brief SAR of antibacterial dinuclear copper(II) complexes.

Vlasenko et al. reported the synthesis of a series of mono- and dinuclear copper(II) complexes derived from N-{2-[(2-diethylamino(alkyl)imino)-methyl]-phenyl}-4-methyl-benzenesulfonamide. 46 The synthesized complexes were screened for fungistatic, protistoicidal and antibacterial activity. Among them, the dinuclear, azide bridged square pyramidal complex (Figure 2, complex 3) exhibited moderate antimicrobial activity against S. aureus.

N,N′-bisoxamides have been shown to be excellent ligands for the formation of polynuclear transition metal complexes and Li et al. synthesized a square pyramidal dinuclear copper(II) complex bridged by N,N′-bis(N-hydroxyethylaminopropyl)oxamide (Figure 2, complex 4). 47 Its antibacterial properties were tested on a panel of five bacterial strains and the complex showed moderate activity against E. coli and S. aureus.

It seems that in these cases, coordination geometry could play an important factor in the antibacterial activities of the complexes, as the square planar complex 2 exhibited higher activity, especially for the Gram-negative E. Coli. In a proposed site contact mediated ROS generation mechanism, square planar geometry would indeed provide a better contact and possibly higher activity than square pyramidal, especially for Gram-negative bacteria, whose membrane structures are more complex.

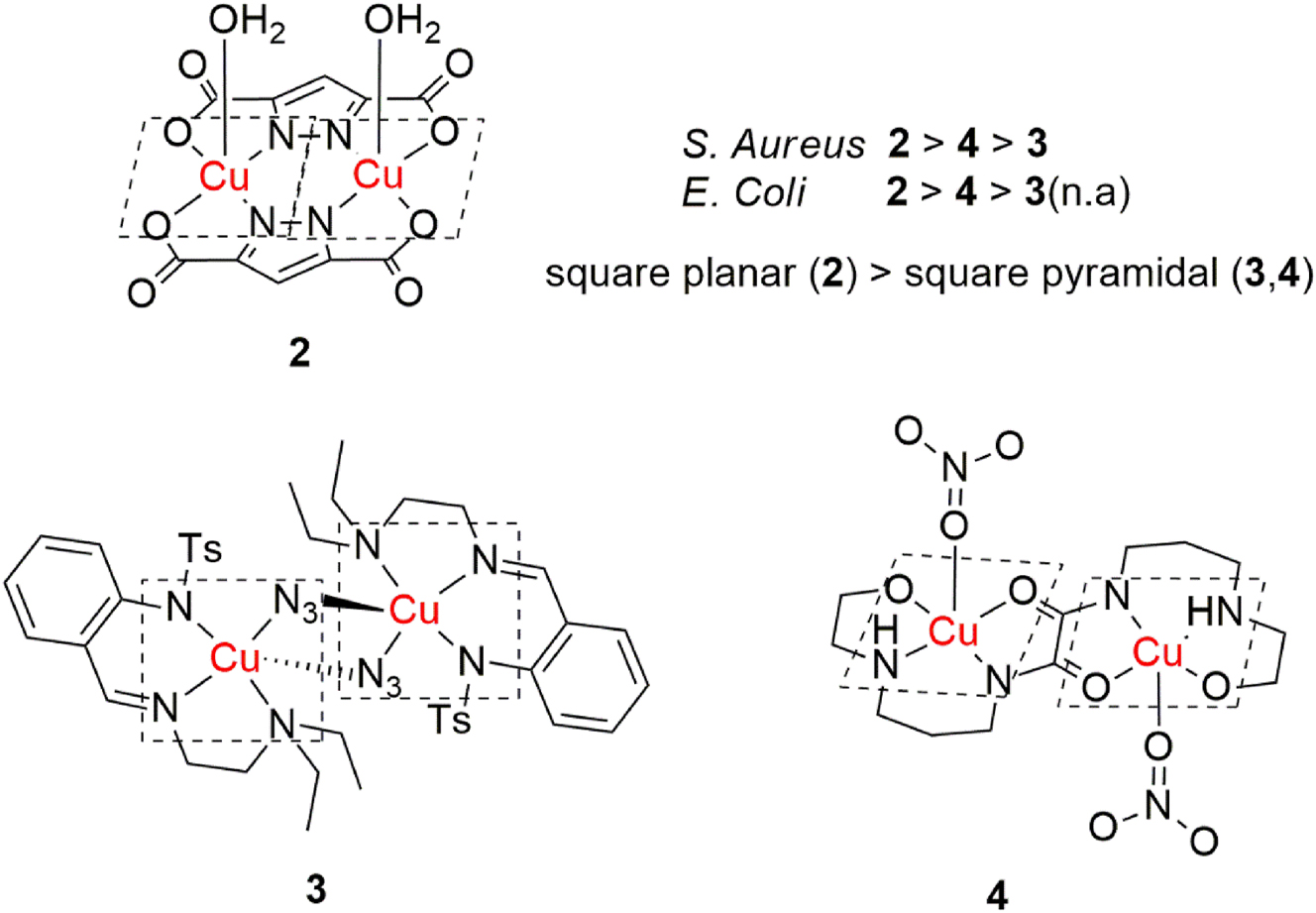

Heterodinuclear copper(II) complexes have shown to be promising antibacterial agents, as well. 48 , 49 Li et al. reported the synthesis of a heterodinuclear copper(II)/zinc(II) complex with a Schiff base ligand, N,N′-bis(salicylidene)propane-1,2-diamine (Figure 3, complex 5). The coordination geometry around the copper atom is distorted square planar, while the zinc atom has distorted tetrahedral geometry in its environment. Antimicrobial activity of the complex was tested on two bacterial strains, S. aureus and E. coli and one fungal strain, Candida albicans. The complex exhibited only moderate activity against E. coli and C. albicans, but showed promising activity against the Gram-positive S. aureus bacteria. 50

Structures and antibacterial activities of heterodinuclear copper(II) complexes (the activitiey of 6 was not compared, as it were determined through the agar diffusion method).

A series of heteronuclear highly active antibacterial oxorhenium (IV) complexes that contain Cu(II), Ni(II), Fe(III), UO2(VI) and Th(IV) was synthesized from 8,17-dimethyl-6,15-dioxo-5,7,14,16-tetrahydrodibenzo[a,h][14]annulene-2,11-dicarboxylic acid. 51 The dinuclear oxorhenium(IV)/copper(II) complex (Figure 3, complex 6) was shown to be highly active against Gram-positive bacteria S. aureus and Gram-negative bacteria, Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas aeruguinosa, while only moderately active against E. coli.

A novel antibacterial heterometallic Cu(II)/Hg(II) complex was synthesized from a 6-bromo-2-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde based Salen-type ligand (Figure 3, complex 7). 52 The copper atom has a distorted square planar geometry, while the mercury atom is hexacoordinated in an irregular pattern. Antimicrobial activities of the complex were tested on a panel of bacteria and fungi and it showed promising antibacterial activity, as it was as effective as the standardly prescribed antibacterial drug, Chloramphenicol, against B. subtilis and E. coli.

Conti et al. examined the antimicrobial potential of highly charged heteronuclear ruthenium(II)/copper(II) polypyridyl complexes with 4,4′-(2,5,8,11,14-pentaaza[15])-2,2′-bipyridilophane and 4,4′-bis-[methylen-(1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane)]-2,2′-bipyridine ligand units. 53 The heterodinuclear ruthenium(II)/copper(II) complex (Figure 3, complex 8) exhibited significant antibacterial activity against the Gram-positive bacterial strain, B. subtilis.

2.2 Comparing antibacterial activities of homodinuclear and heterodinuclear copper complexes

When comparing the antibacterial activities of homodinuclear and heterodinuclear complexes, the heterodinuclear complexes seemingly exhibit greater activity. This phenomenon could possibly be explained by the synergistic action of two different metal coordination centers. Metal complexes can exhibit their antibacterial activity in a number of ways, including inhibition of cell wall synthesis, disruption of cell membrane integrity, inhibition of protein synthesis, disruption of enzyme function, inhibition of nucleic acid synthesis and their function, antimetabolite activity and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The addition of another metal in the dinuclear structure could broaden the scope of their action and these different mechanisms occurring simultaneously could synergistically enhance the activity of such complexes. This could prove to be a valuable strategy for developing novel, more potent antimicrobial agents and combating bacterial resistance.

2.3 Antifungal dinuclear copper complexes

Beyond bacterial infections, the number of cases of invasive fungal infections is on the rise globally and poses a serious health risk, candidiasis most notably. 54 Fungi of the Candida genus are particularly dangerous due to their resistance to most known antifungals. As the need for new, more potent antifungals increases, copper complexes, with their antimicrobial properties, represent an interesting and exciting possibility in finding more powerful and improved antifungal agents.

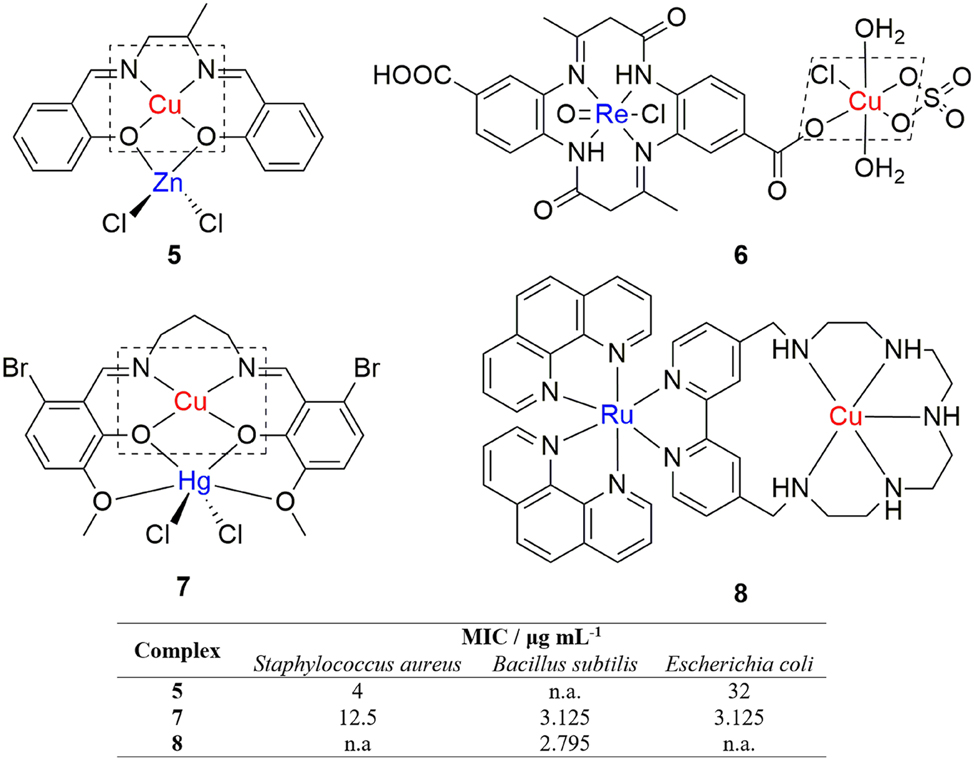

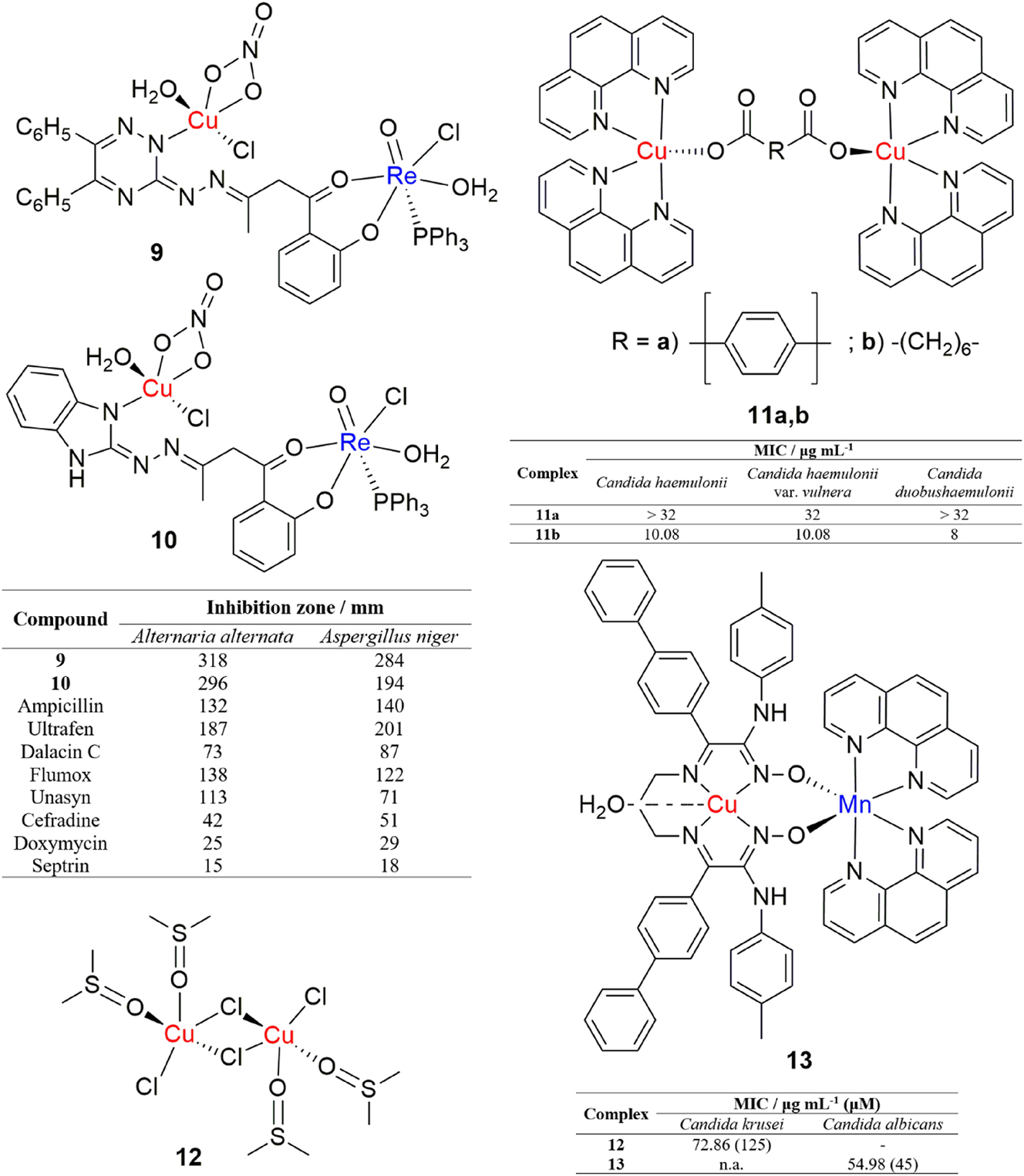

Mashaly et al. synthesized a series of dinuclear oxorhenium(V) complexes with Cu(II), Fe(III), Co(II), Ni(II), Cd(II) and UO2(VI) from 1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)butane-1,3-dione-3-(5,6-diphenyl-1,2,4-triazine-3-ylhydrazone) and 1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)butane-1,3-dione-3-(1H-benzimidazol-2-ylhydrazone). 55 Two copper(II)/oxorhenium(V) complexes (Figure 4, complexes 9 and 10) showed promising antifungal activities, as they were overall more active against common fungal airborne pathogens, Alternaria alternata and Aspergillus niger, than a series of eight commonly prescribed antibiotics.

Structures and antifungal activities of dinuclear copper(II) complexes.

Gandra et al. examined the antifungal potential of a big series of copper(II), manganese(II) and silver(I) complexes against several multidrug resistant fungal species that form the Candida haemulonii complex. 56 The two dinuclear copper(II) complexes (Figure 4, 11) exhibited notable activity against the three tested Candida strains, C. haemulonii, C. haemulonii var. vulnera and Candida duobushaemulonii. Fungal species from the C. haemulonii complex are known to be highly resistant against most known antigungal agents. Complex 11b, in particular, exhibited high activity against all tested fungal strains.

While investigating the reaction of the polymeric complex trans-[CuCl2(dmso)2]n with a 2-thiohydantoin derivative, 3-[(2-hydroxybenzyl-idene)amino]-2-thioxoimidazolidin-4-one, Stanić et al. reported the formation of a dinuclear copper(II) dimethylsulfoxide complex (Figure 4, complex 12). 57 The trigonal bipyramidal dinuclear complex was obtained through thiohydantoin-assisted isomerization and the DMSO ligands that were in trans positions in the starting complex were shifted to cis positions. Antimicrobial activity of the complex was tested on a panel of six bacterial and two fungal strains and the complex was moderately active against the fungal strain Candida krusei.

Yoğurtçu et al. investigated the anticandidal activity of a heterodinuclear copper(II)/manganese(II) Schiff base complex (Figure 4, complex 13) against C. albicans ATCC10231 and examined potential mechanisms of its antifungal action. 58 The complex exhibited strong anticandidal activity and also, it has been shown that the complex induces apoptosis and necrosis through ROS generation and regulation of specific biomarkers.

Dinuclear copper complexes were shown to be prospective antifungal agents, active against a variety of fungal strains. The literature pertaining to their antifungal activities is promising, but leaves much to be desired. There are not enough results to undergo a dedicated structure-activity relationship analysis or even adequately compare homo- and heterodinuclear complexes. It could be possible, however, like in the case of antibacterial complexes, that heterodinuclear copper complexes might exhibit a broader scope of action, due to the synergistic action of two different metal centers. More research is needed on this topic in order to elucidate possible differences in their potencies and mechanisms of action.

3 Dinuclear copper complexes as anticancer agents

Ever since the advent of platinum-based anticancer drugs, research interest in metal complexes and bioinorganic chemistry in general has skyrocketed. It has gotten to the point that it seems that metal-based drugs hold a frontier monopoly in anticancer research. Even though platinum-based drugs, cisplatin and the sort, are highly effective against a plethora of malignant cancers, they still possess various drawbacks that hinder the amelioration of the disease as a whole. Some of these drawbacks include dose limitations, drug resistance and various toxic effects. 59

Copper, an essential element, could offer potential solutions to some of these issues, as it is believed that endogenous metals exhibit fewer toxic effects to normal functioning cells, as opposed to tumor cells. 60 Copper and its complexes have shown a quite large potential in anticancer therapy. 61 , 62 Many copper complexes have been synthesized and screened for antitumor activity, but none of them have made it to clinical practice yet. The path of drug discovery, from the lab to the patient, is long and tedious, but there are some promising discoveries being made in the realm of copper based anticancer agents. For example, out of a big family of about a hundred copper compounds, patented under the name Casiopeína®, one has reached phase I of clinical trials. 63

3.1 Dinuclear copper complexes with antiproliferative activity

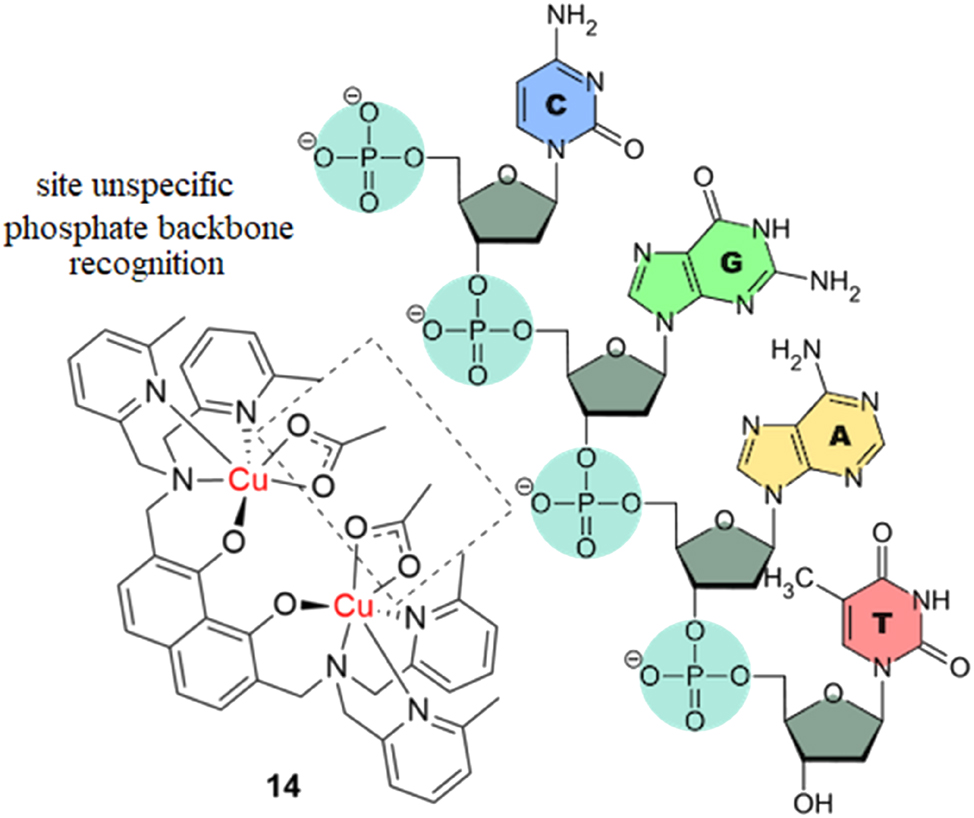

When designing novel metal anticancer agents, the first aspects often considered are their DNA-binding and cleaving capabilities. 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 It is well established in the scientific community that cisplatin mostly binds to two neighboring guanines of a single strand of the DNA double helix. From the purview of a rational drug design mindset, it is important to explore alternative binding modes and mechanisms of action, which is what Jany at al. reported in their work. 77 They synthesized a highly cytotoxic trigonal bipyramidal dinuclear copper(II) complex, with 2,7-bis(N,N-di((6-methylpyridin-2-yl)methyl)-aminomethyl)-1,8-bis(methoxy-methoxy)naphthalene as the bridging ligand (Figure 5, complex 14), which is highly active against the HeLa cervical cancer cell line. The survival rate of the cells drops to zero at 10 μM of the complex. There is, however, no data on the effect of the complex on healthy cells, which is vital for pre-screening for potential adverse effects and safety of the complex. The complex strongly and irreversibly binds to two neighboring phosphate groups at the backbone of the double-stranded DNA and promotes cytotoxicity by inhibiting DNA synthesis. It was specifically designed to avoid the less exposed nucleobases through steric repulsion of the pyridine groups. The rigid naphthalene spacer between the two copper atoms also prevents coordination to one phosphate. The study demonstrates a rational design approach in supramolecular recognition.

Highly cytotoxic dinuclear copper complex that binds to two neighboring phosphate groups in the backbone of DNA.

Anticancer activity of many novel dinuclear copper(II) and copper(I) complexes has been examined and the research has certainly produced some interesting and significant results. 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 For example, Kellett et al. reported a synthesis of novel dinuclear copper(II) and manganese(II) complexes with incredible nano- and picomolar in vitro cytotoxic activities against colorectal tumor HT29, SW480 and SW680 cell lines. 99 The trigonal bipyramidal dinuclear copper(II) 1,10-phenantroline complex, bridged with octanedioic acid (Figure 6, complex 15) is exceptionally cytotoxic towards the HT29 cell line, with a lethal dose (LD50) in the picomolar range after 96 h. The effect of the complex on the survival of healthy HaCaT cells has been examined as well, and the HT29/HaCat selectivity index (SI) is exceptionally high (>719) due to the activity of the complex. ROS generation capabilities were evaluated over a wide concentration range (100,000–195 nM) and it was shown that the complex has low ROS generation activity, lower than that of the positive control, 0.5 μM H2O2. The complex is shown to bind strongly to DNA and is suggested to self-cleave it through an intercalation and copper-mediated π carboxyl radical formation mechanism. The surprisingly high activity of the complex represents a giant leap forward towards novel, more potent chemotherapeutics.

Structure and activity of a dinuclear copper complex with an astonishing picomolar antiproliferative activity.

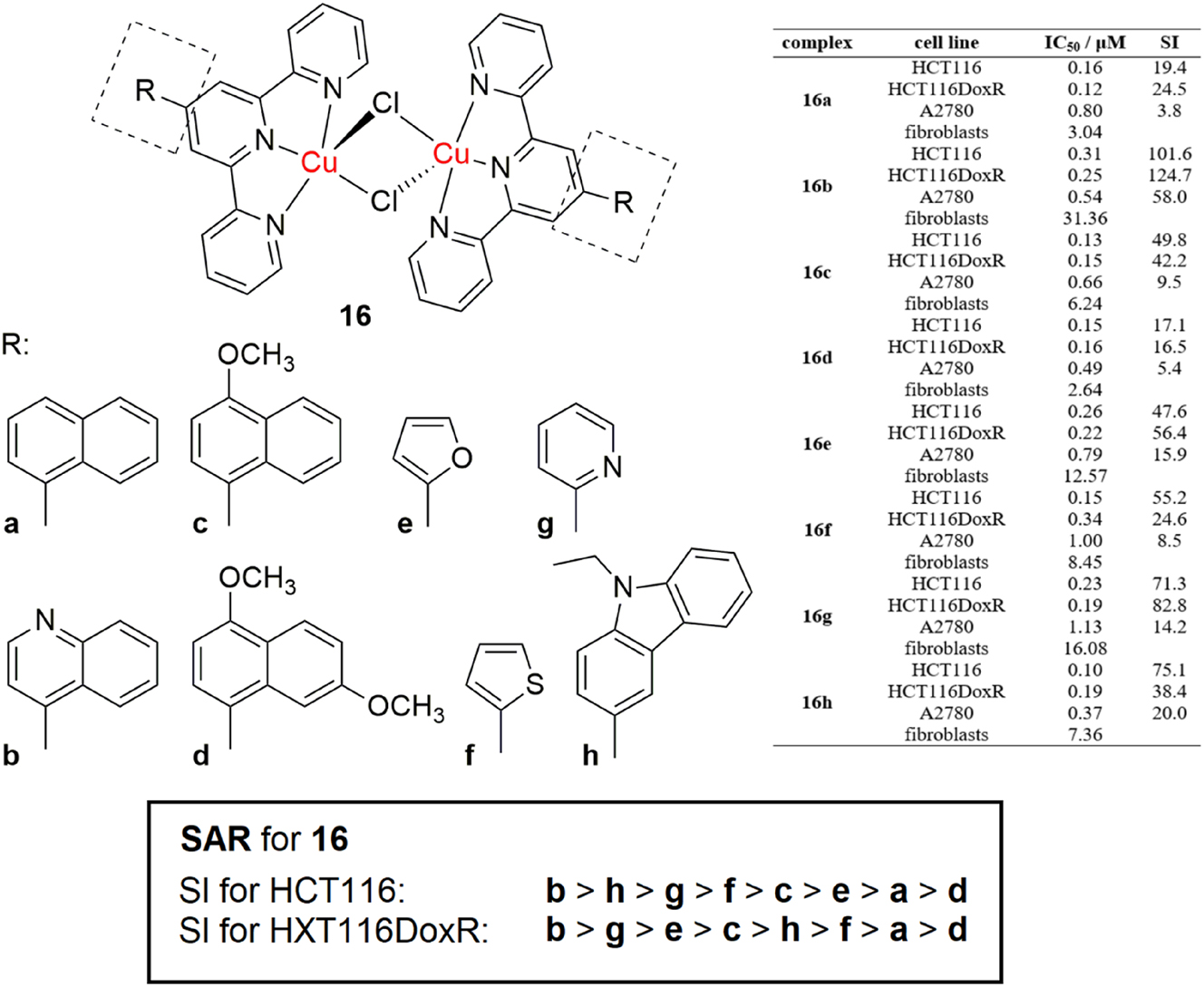

Choroba et al. reported the synthesis of a series of square pyramidal dichlorido−μ−bridged 4′-substituted terpyridine dinuclear copper complexes with highly potent nanomolar antiproliferative activity against A2780 ovarian carcinoma, HCT116 colorectal carcinoma and HCT116DoxR colorectal carcinoma resistant to doxorubicin cell lines (Figure 7, complexes 16a-h). 100 The complexes exhibited reduced cytotoxicity to healthy fibroblast cells, with selectivity indexes up to 124.7. The activities for the A2780 ovarian carcinoma cell line were high, however, the SI values were lower. When comparing the activities of the complexes towards the two colorectal carcinoma cell lines, the SI values are in the order for the HCT116 line are 16b > 16h > 16g > 16f > 16c > 16e > 16a > 16d, while for the doxorubicin resistant call line HCT116DoxR, they are 16b > 16g > 16e > 16c > 16h > 16f > 16a > 16d. The most selective in both cases was 16b. Complex 16g had high selectivity in both cases, while 16e and 16h were more selective towards the doxorubicin resistant cell line. Overall, complexes 16b (4-quinolinyl), 16c (4-methoxy-1-naphthyl), 16e (2-furanyl) and 16g (2-pyridynyl) showed the most promising therapeutic potential. The complexes exhibit their anticancer mechanism through apoptosis, autophagy and ROS generation. At IC50 concentration values, the complexes exhibited ROS generation activity comparable to the positive control (5 μM cisplatin and 42 μM t-butyl hydroperoxide). The complexes also did not exhibit any toxicity in the ex-ovo chick chorioallantoic membrane assay after 48 h of exposure at IC50 concentrations. The therapeutic potential of these complexes is promising, as they exhibit high antiproliferative activity and great selectivity for doxorubicin resistant colorectal HCT116DoxR carcinoma cells and also, no in vivo toxicity. Upon further in vivo preclinical evaluation, they could possibly be proven to be prospective clinical candidates.

Structure and SAR for a series of highly potent antiproliferative dinuclear copper terpyridine complexes.

In the search for new anticancer agents, heterodinuclear complexes offer a variety of interesting possibilities. Many heterodinuclear copper(II) and copper(I) complexes were synthesized and tested for anticancer activity. 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 , 109 The often severe side effects that occur during cisplatin treatment were motivation to explore other metals as alternatives. Combining copper(II) with platinum(II) has produced some interesting results. For example, Pivetta et al. reported that co-administering a copper(II) complex along with cisplatin in a “multi-drug” approach had a synergistic effect, in which improved antiproliferative activity was observed against cisplatin-resistant leukemic cancer cells (CCRF-CEMres) and cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells (A2780res). 110 This effect is believed to arise from the formation of mixed dinuclear complex species that were identified by electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry.

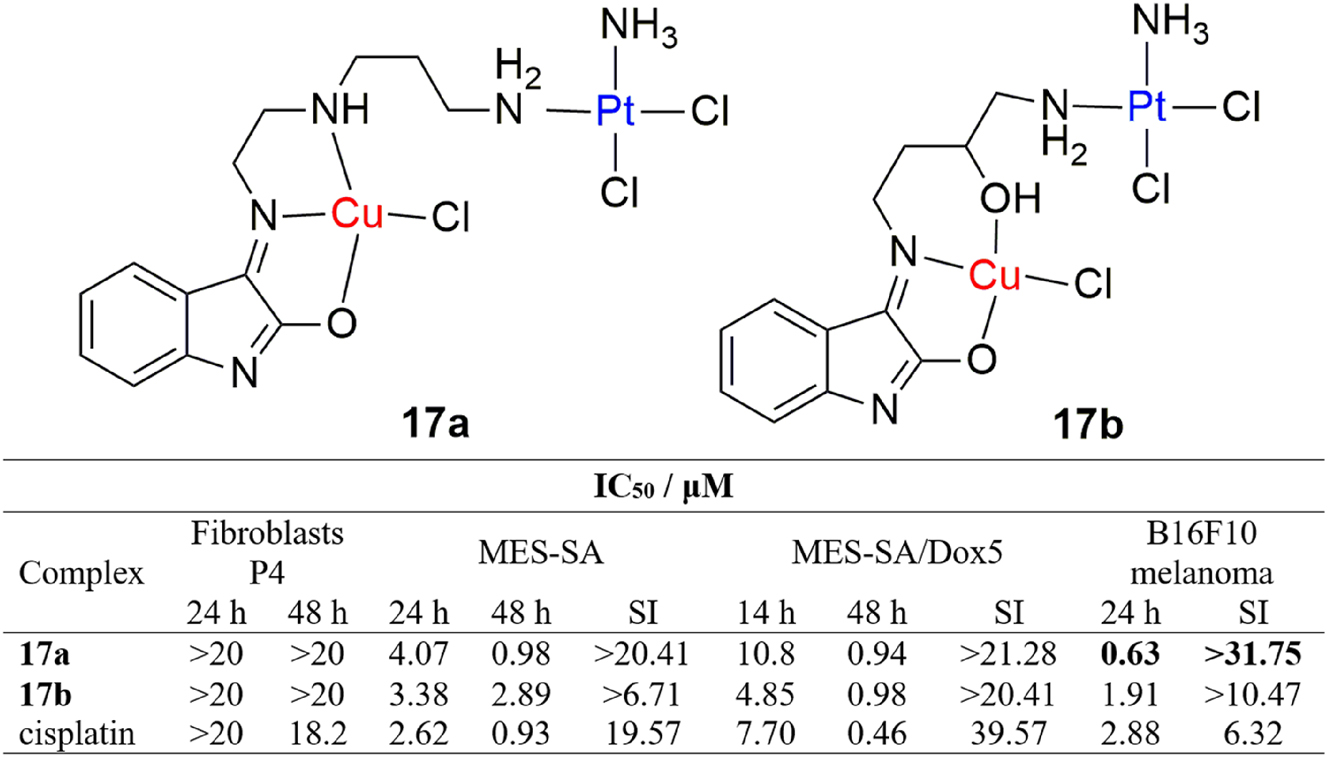

Heteronuclear copper(II)/platinum(II) complexes were shown to be promising anticancer agents. 111 In published work by Aranda et al., a synthesis of cisplatin-derived oxindolimine copper(II) complexes was reported, along with their cytotoxic activities against a panel of tumor cell lines including human uterine sarcoma MES-SA, doxorubicin resistant human uterine sarcoma MES-SA/Dox5 and murine melanoma B16F10 and on healthy fibroblast P4 cells, as well (Figure 8, complexes 17a-b). 112 The complexes exhibited overall comparable cytotoxic activity to cisplatin, except for 17a, which exhibited four-fold improved antiproliferative activity against murine melanoma B16F10 cells, with far greater selectivity (SI > 31.75). The mechanism of their antitumor action involves multiple pathways, including distortion of DNA conformation, ROS-mediated DNA cleavage and cell cycle arrest by inhibiting kinase and phosphatase proteins. 113

Structure and antiproliferative activity of heterodinuclear oxindolimine copper(II)/platinum(II) complexes.

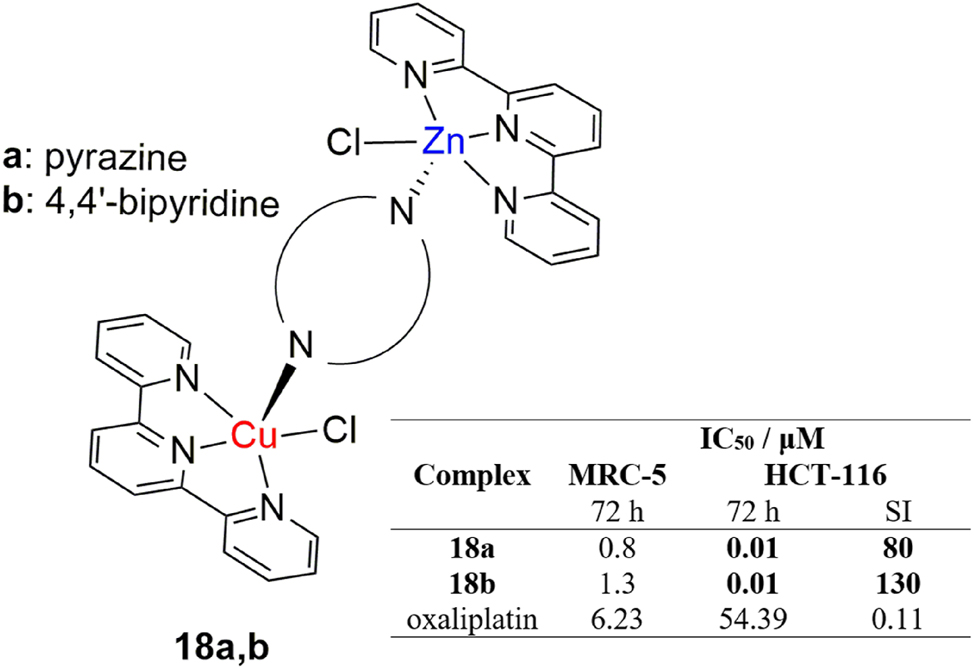

Zinc is another promising candidate for heterometallic anticancer complexes. In a paper by Halilagić et al., two novel dinuclear zinc(II)/copper(II) complexes were synthesized starting from mononuclear zinc(II)-terpyridine and copper(II)-terpyridine complexes, bridged with either pyrazine or 4,4′-bipyridine (Figure 9, 18a,b). 114 Both complexes exerted a highly cytotoxic effect towards the colorectal HCT-116 cell line, induced by a strong prooxidative response, higher than the commonly prescribed drug, oxaliplatin, with even greater selectivity. The complexes were also observed to influence the production of superoxide radical species, indicating that ROS generation is a plausible mechanism of their anticancer action. The results are encouraging and offer an alternative to platinum in the design and synthesis of potential zinc and copper-based anticancer drugs.

Structure and antiproliferative activity of heterodinuclear copper(II)/zinc(II) terpyridine complexes.

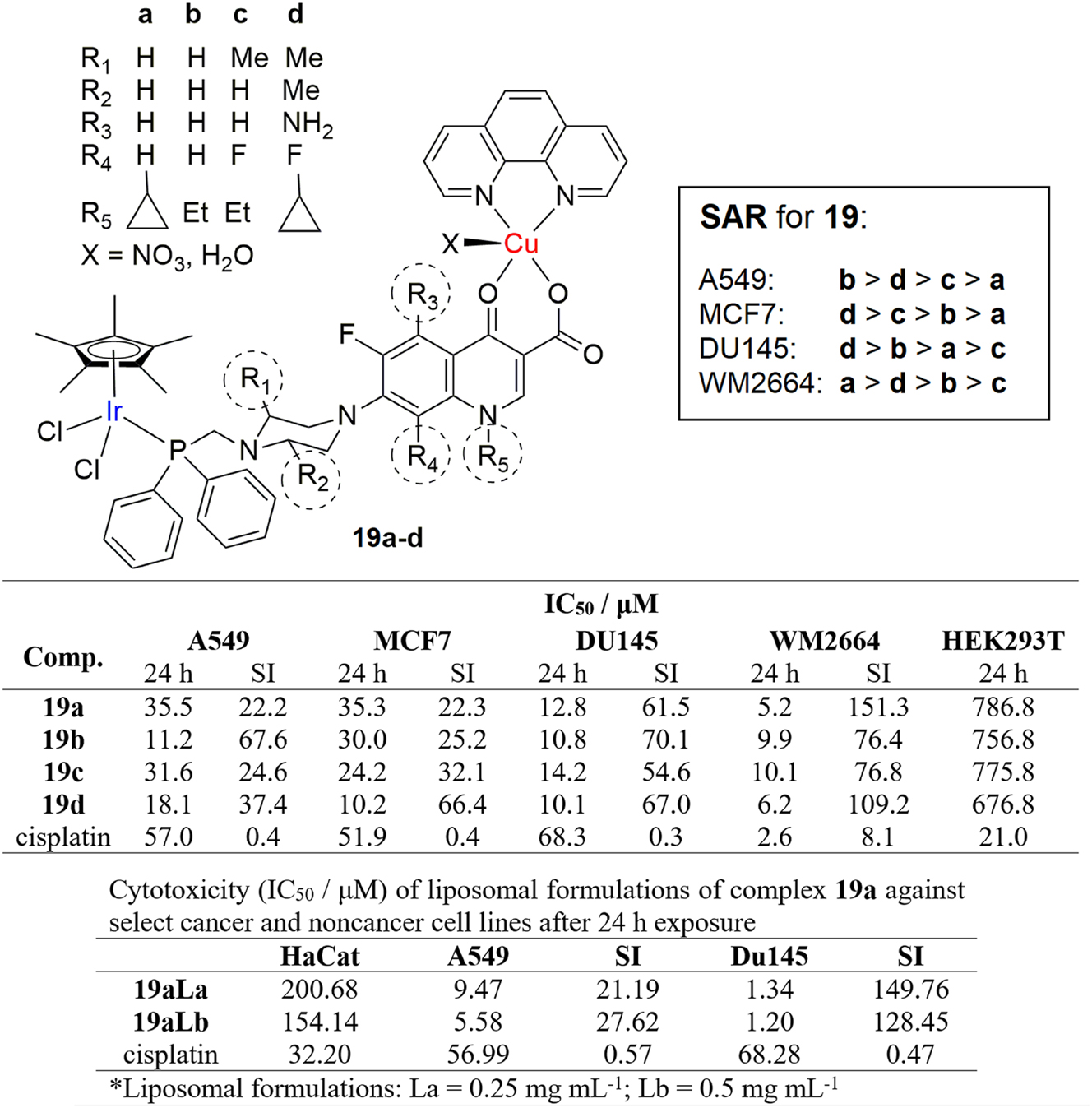

Other metals from the platinum group, albeit obvious, are also promising candidates in the search for new and better chemotherapeutics. 115 Komarnicka et al. reported the synthesis and potent in vitro anticancer activity of novel dinuclear iridium(III)/copper(II) complexes. 116 The complexes consist of square pyramidal copper(II)-phenanthroline and tetrahedral iridium(III)-cyclopentadienyl subunits bridged with phosphine derived fluoroquinolone antibiotics, sparfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, lomefloxacin and norfloxacin (Figure 10, complexes 19a-d). Their in vitro cytotoxic activity was tested on a panel of tumor cell lines and the complexes were more active than cisplatin against A549 lung cancer, MCF7 breast cancer and DU145 prostate cancer cell lines. Effects of the complex on healthy HEK293T cells was tested as well and all the complexes exhibited significantly reduced cytotoxicity than cisplatin, showing great selectivity (SI values are shown in Figure 10). What is even more interesting about these results is that the most redox-active and fluorescent complex 19a showed an increase of cytotoxicity of 10-fold against DU145 prostate cancer cells and 6-fold against A549 lung cancer cells, when loaded in a liposomal formulation, with very high selectivity (SI well above 100). The liposomal formulation was prepared in order to maximize water solubility, transport and biodistribution, while decreasing adverse side effects. These liposomes loaded with 19a have been shown to effectively accumulate inside both A549 lung cancer and DU145 prostate cancer cells, while colocalization has been observed in nuclei. It has been shown through cytometry that apoptotic pathways are predominantly responsible for cytotoxic action of the complexes. These results are quite remarkable, as they describe a potential use of these liposome loaded complexes in targeted prostate cancer therapy.

Structure and cytotoxicity and brief SAR of dinuclear iridium(III)/copper(II) complexes and their liposomal formulations against select cancer and healthy cell lines.

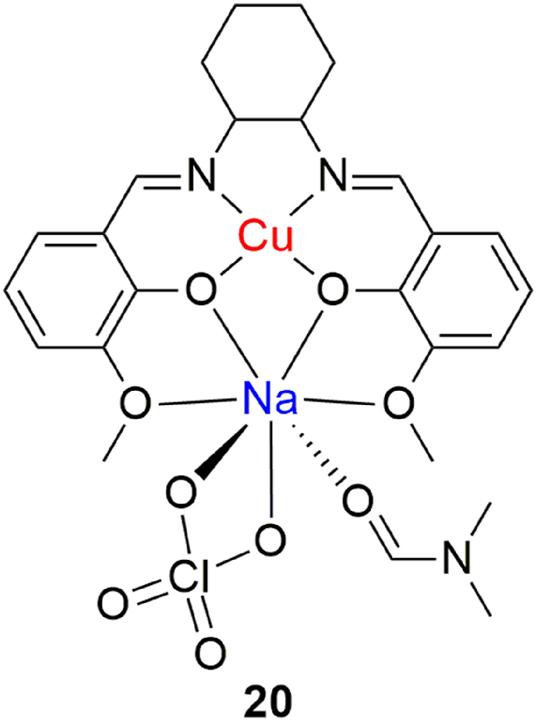

In anticancer research, sometimes less obvious and more unlikely possibilities can yield surprising results. Sodium is certainly not an obvious candidate in the search for novel anticancer agents. Even though alkali metals have a crucial role in numerous biological pathways, results pertaining to anticancer sodium complexes are scarce and leave plenty of space for future research. 117 , 118 Interestingly enough, Usman et al. report in their work the anticancer activity of a heteronuclear copper(II)-sodium(I) complex against human breast tumor cells. 119 The dinuclear complex is synthesized from a Schiff-base ligand derived from 1,2-diaminocyclohexane and o-vanillin (Figure 11, complex 20). The decision to incorporate sodium was built upon strong evidence that sodium channels play an important role in programmed cell death and represent likely targets in cancer therapy. 120 The complex exhibited promising cytotoxic activity (IC5024 h = 6.75 μM) against the MCF-7 breast cancer call line, comparable to that of cisplatin. There is, however, no information on the effect of the complex on healthy cells, which poses the question of potential selectivity and safety. The results show that the complex induces cell death through apoptosis, which is suggested to be induced by ROS generation, oxidative DNA damage and cleavage. The results represent an important footnote, as they show that promising anticancer agents can be found far from the usual platinum group suspects.

Heterodinuclear copper(II)/sodium(I) complex with antiproliferative activity.

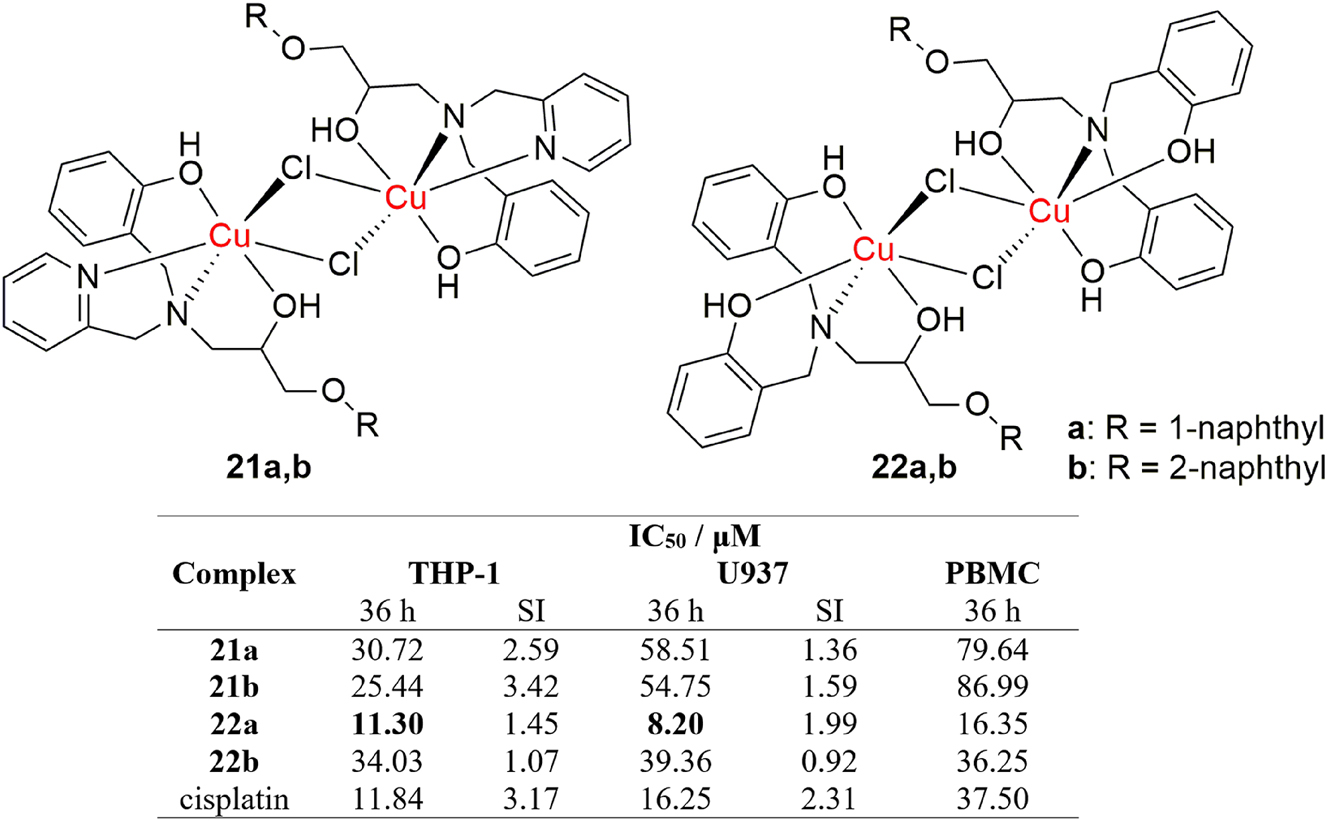

3.2 Dinuclear copper complexes that target death receptors

Beyond DNA damage induced cytotoxicity, there are more ways in which a complex can manifest its anticancer activity and they involve up-regulation of apoptotic pathways by binding to specific receptors, as reported by Fernandes et al. 121 They reported a synthesis of four novel octahedral dinuclear copper(II) complexes (Figure 12, complexes 21a,b and 22a,b) that exhibit cytotoxic activity against THP-1 and U937 leukemia cell lines. Out of the four complexes, 22a showed greater activity than cisplatin. The complexes exhibited greater toxicity than cisplatin on healthy PBMC cells, however, the most active complex 22a exhibited lower in vivo toxicity in mice, compared to cisplatin, which indicates that the complex is potentially safer than cisplatin. Further findings show that the complex induces caspase-8 activation mediated apoptosis, which is initiated by binding to so-called “death” receptors on the cell wall. This is significant because it demonstrates that the complex does not need to enter the cancerous cells in order to destroy them, which is a major drawback related to cisplatin drug uptake. The results are an important footnote in anticancer research, as they show that death receptors are viable and prospective targets for novel copper based anticancer drugs.

Structure and activity of dinuclear copper complexes that target death receptors.

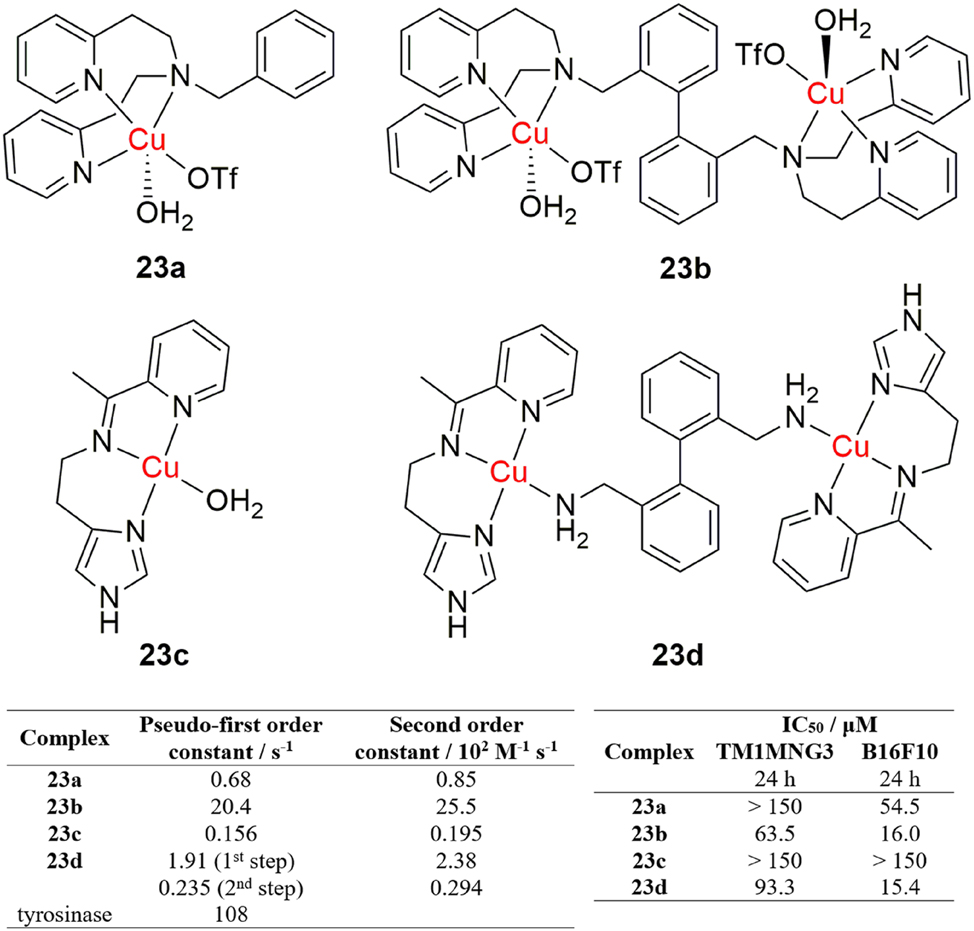

3.3 Dinuclear copper complexes with tyrosinase mimicking activity

In the overall fight against cancer, it is important to consider the various forms it can take, as it is an all-encompassing disease that can afflict virtually any tissue. When a metal complex exhibits more than one biological activity, its potential application in the treatment of more complex forms of cancer increases. This is presented in a paper by Nunes et al., where novel dinuclear copper(II) complexes with both nuclease and tyrosinase mimicking activities were shown to exhibit anticancer activity towards melanoma B16F10 and TM1MNG3 cells (Figure 13). 122 The activity of the dinuclear complexes 23b and 23d was compared with the activity of their mononuclear counterparts 23a and 23c. The mononuclear complexes were a lot less active than the dinuclear complexes and also, a correlation between tyrosinase and anticancer activities of the complexes was established, as the rate of inhibition of melanoma viability rose along with tyrosinase activity (Figure 13). This correlation was made even more apparent by the fact that the highly melanogenic B16F10 cells were more affected by the complexes than the TM1MNG3 cell line, that produces much less melanin. The results produced by this study provide a potential strategy for the treatment of melanoma, which is a frequently occurring, more invasive form of cancer. In a wider frame of reference, the results offer an alternative mechanism in which a copper(II) complex can exhibit anticancer activity.

Tyrosinase mimicking dinuclear copper complexes with anticancer activity.

3.4 Structure-activity relationships of anticancer dinuclear copper complexes

Establishing a systematic understanding of how molecular modifications affect the anticancer activity of a complex is imperative for the rational development of more potent, selective and less toxic compounds. In this chapter, we will shortly discuss the structural elements of dinuclear copper complexes that are most responsible for the modulation of their anticancer activities and propose how fine-tuning these structural features could allow for enhanced binding to cancer cell targets, improved DNA interactions, better cellular uptake, and ultimately, more effective and safer cancer treatment options.

The first structural element to consider is coordination geometry. In the literature reviewed thus far, results consistently show that geometries with axial lability (mainly square pyramidal) at one or both copper centers correlates with higher biological activity. This is most likely because they would allow easier ligand exchange (aquation or glutathione binding), easier access to Cu(II)/Cu(I) cycling with intracellular reductants and easier Fenton-type ROS generation. On the other hand, rigid, fully saturated octahedral sites exhibit lower activity, unless the ligand environment enforces Cu⋯Cu proximity and internal redox cooperation. Mixed geometry systems (square planar and square pyramidal) show enhanced DNA cleavage and lower IC50 values, likely because one site prefers π-stacking and promotes binding, while the other remains substitution-labile and redox reactive.

Ligand design is another crucial element that determines the activity of a complex. Planar aromatic co-ligands, such as phenathroline, terpyridine and bipyridine consistently boost DNA affinity through intercalation or partial stacking, which increases nuclease-like cleavage and cytotoxicity. Results from the analyzed literature seem to indicate that Schiff bases and similar N,O-donors tune redox activity. Strong σ-donors stabilize Cu(II), shift the redox potential (E1/2) of the Cu(II)/Cu(I) system to more negative values and hinder ROS generation. Incorporating phenoxo and alkoxo donors could increase internal redox potentials and accelerate DNA cleavage. It is important to keep the redox potential in the biologically accessible range, so incorporating moderate donating N,O-donors could prove beneficial. Lipophilicity is another important factor in ligand design. Pendant alkyl groups and extended aromatics could improve uptake, but too much hydrophobicity can reduce solubility and bioavailability. Adequate labile ligands (acetate, for example) can be important as well, as they can be displaced by glutathione, which channels the complex into Cu-mediated redox cycling and intracellular ROS generation. It is also important for the complex to maintain an overall cationic character, as dications and tetracations seem to have a higher cellular uptake.

Bridging motifs need to be considered and chosen carefully, because they need to enforce Cu⋯Cu cooperation. μ-Hydroxo, μ-oxo, μ-phenoxo and μ-alkoxo bridges shorten Cu⋯Cu distances, enabling cooperative redox processes like two-site H2O2 activation and superoxide and hydroxyl formation. These systems often show faster oxidative DNA cleavage and lower IC50 than analogous mononuclear complexes. μ-Acetato and μ-benzoato bridges offer a balance of rigidity and lability, as they can keep metals close for inner-sphere ROS generation, yet can rearrange to open a coordination site for biomolecular binding. Azido and pyrazolato bridges form rigid cores with strong magnetic coupling. Their activity, though, still depends on whether the bridge allows for axial lability. Rigid bridges in combination with planar aromatics still form complexes with strong DNA binding. ROS output, however, may be lower unless ancillary ligands are labile. The number of bridges seems to have an impact on activity, as well. Bis-bridged complexes show a pattern of higher ROS generation and DNA cleavage compared to mono-bridged complexes, as long as one axial site remains available. In summary, short, electron-sharing bridges that preserve one labile site often lead to higher ROS-mediated nuclease activity and cytotoxicity.

3.4.1 Homonuclear (Cu–Cu) versus heteronuclear (Cu–M) systems

The main point of contention in the topic of dinuclear complexes seems to be the comparison of homonuclear and heteronuclear complexes. Although there is no definitive answer, the literature does offer some suggestions and guidelines that could be followed in order to yield better results in terms of rational design.

Homonuclear complexes typically show stronger ROS-mediated cytotoxicity and DNA cleavage, especially when μ-oxo, μ-hydroxo and μ-phenoxo bridges enforce short Cu⋯Cu separations and their dual redox-active sites cooperate efficiently. Two proximate Cu sites share electron density through the bridge and the redox potential is often in the ideal range ensuring quasi-reversible redox behavior and faster Cu(II)/Cu(I) cycling. On the other hand, in heteronuclear Cu-M systems (especially when the other metal is redox inactive, like zinc), the redox potential is dominated by the Cu site and can shift to more negative values if the second metal withdraws electron density through the bridge, which can reduce ROS generation rates. If the other metal in the Cu-M system is redox-active, it can show a multi-step cyclic voltammogram with broader windows, which can yield mixed results. In this case, added caution is needed when considering which metal to use and the bridge ligand electronics.

Heteronuclear complexes seem to show more variability in the potency of their activities. For example, in Cu–Zn systems, Zn contributes Lewis acidity and structural rigidity, but no redox potential. The redox activity of this system would rely solely on the Cu center, while the DNA binding would rely on the overall architecture. These systems, however, can exhibit enhanced DNA binding and better selectivity. In Cu–Pt systems, the combination of DNA platination and Cu-mediated ROS generation can improve potency in slow growing tumor cell lines. The caveat in this case is the higher risk of off-target toxicity.

To summarize, Cu–Cu systems offer higher redox activity and faster ligand exchange and should be considered if higher ROS-mediated DNA cleavage is desired. However, Cu-M systems could offer more kinetic and metabolic stability, which could mean less Cu leaching and toxic side effects. Ultimately, Cu-M systems could trade potency for an overall pharmacological balance.

4 Dinuclear copper complexes as anti-inflammatory agents

Copper plays a crucial role in processes related to inflammation and oxidative stress. Natural regulation of inflammatory responses involves an increase in blood copper levels during acute and chronic inflammation. 123

Copper complexes have amassed plenty of research interest due to their potential anti-inflammatory properties. Copper(II) complexes can directly inhibit the activity of enzymes responsible for the production of inflammatory mediators. 124 For example, some copper(II) complexes can mimic the activity of catecholases, enzymes that play an important role in the degradation of catecholamines, neurotransmitters involved in inflammatory processes. 125 Copper(II) complexes can also carry out their anti-inflammatory activity through their action as antioxidants, reducing cell damage caused by reactive oxygen species, which are often involved in inflammatory processes. 126

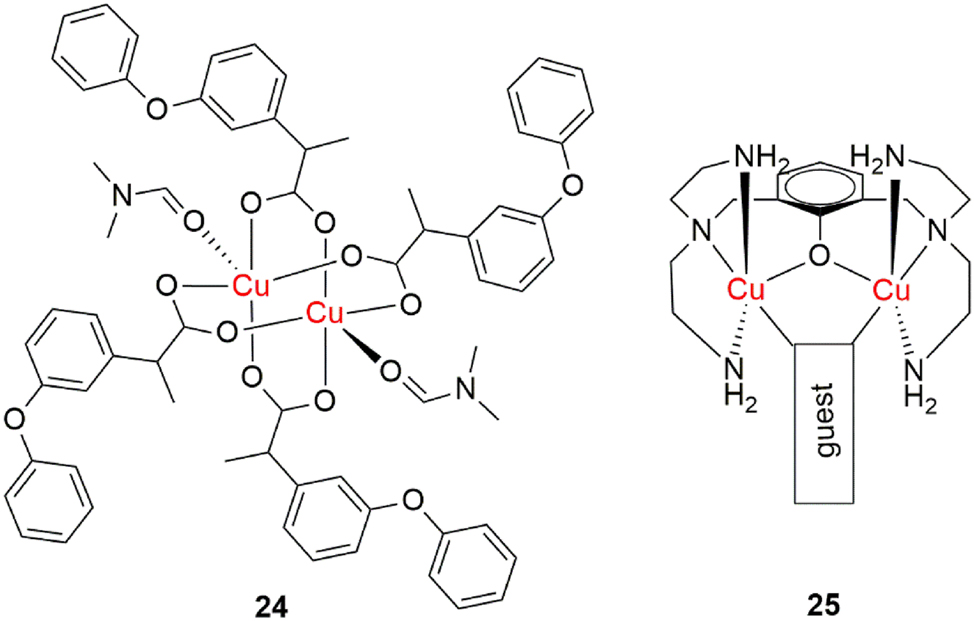

4.1 Dinuclear copper complexes with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Copper(II) complexes formed with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were shown to exhibit enhanced activity in reducing inflammation compared to the parent drugs. In a study by Agotegaray et al., a dinuclear complex, synthesized from calcium fenoprofenate, significantly reduced carrageenan-induced inflammation in experimental mouse models (Figure 14, complex 24). 127 Compared to calcium fenoprofenate, the complex showed prolonged and more intense anti-inflammatory activity. The greatest difference was observed 7 h after administration, when the complex reduced inflammation by 50 %, while the original drug achieved only 20 % reduction. This effect is attributed to the ability of copper centers to bind catecholes and transform them through oxidation, resulting in prolonged pharmacological action.

Anti-inflammatory dinuclear copper(II) complexes.

4.2 Dinuclear copper complexes with nitric oxide scavenging activity

Nitric oxide (NO) has an essential role in inflammatory processes, but its overproduction can lead to tissue damage and autoimmune diseases. A dinuclear copper(II) complex, synthesized by Chiarantini et al. (Figure 14, complex 25), selectively binds and removes NO from biological systems without interfering with the natural expression of the iNOS (inducible nitric oxide synthase) enzyme. 128 In macrophage cell models (RAW 264.7), stimulated with lipopolysaccharides, the complex significantly reduced nitrite levels (an indicator of NO presence) in the culture medium.

5 Dinuclear copper complexes as antioxidants

Dinuclear copper(II) complex structures can be found in active sites of several vital metalloenzymes, such as the aforementioned catechol oxidase, hemocyanin and tyrosinase. 129 Moreover, there is a heterometallic copper(II)/zinc(II) active center in the structure of superoxide dismutase (SOD), an enzyme with an antioxidant role, which is primary involved in the disproportionation of the superoxide radical. Cu/Zn SOD functions as an integral part of a defense system against harmful reactive oxygen radical species (namely superoxide), which it converts to less reactive hydrogen peroxide, which is further eliminated by catalase. The enzyme functions to protect the body from oxidative cellular damage. It has been established that the copper(II) ions in the active site play a key role in the redox-based dismutation process. As a result, dinuclear copper(II) complexes have been studied extensively for their antioxidant activity. 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 , 134

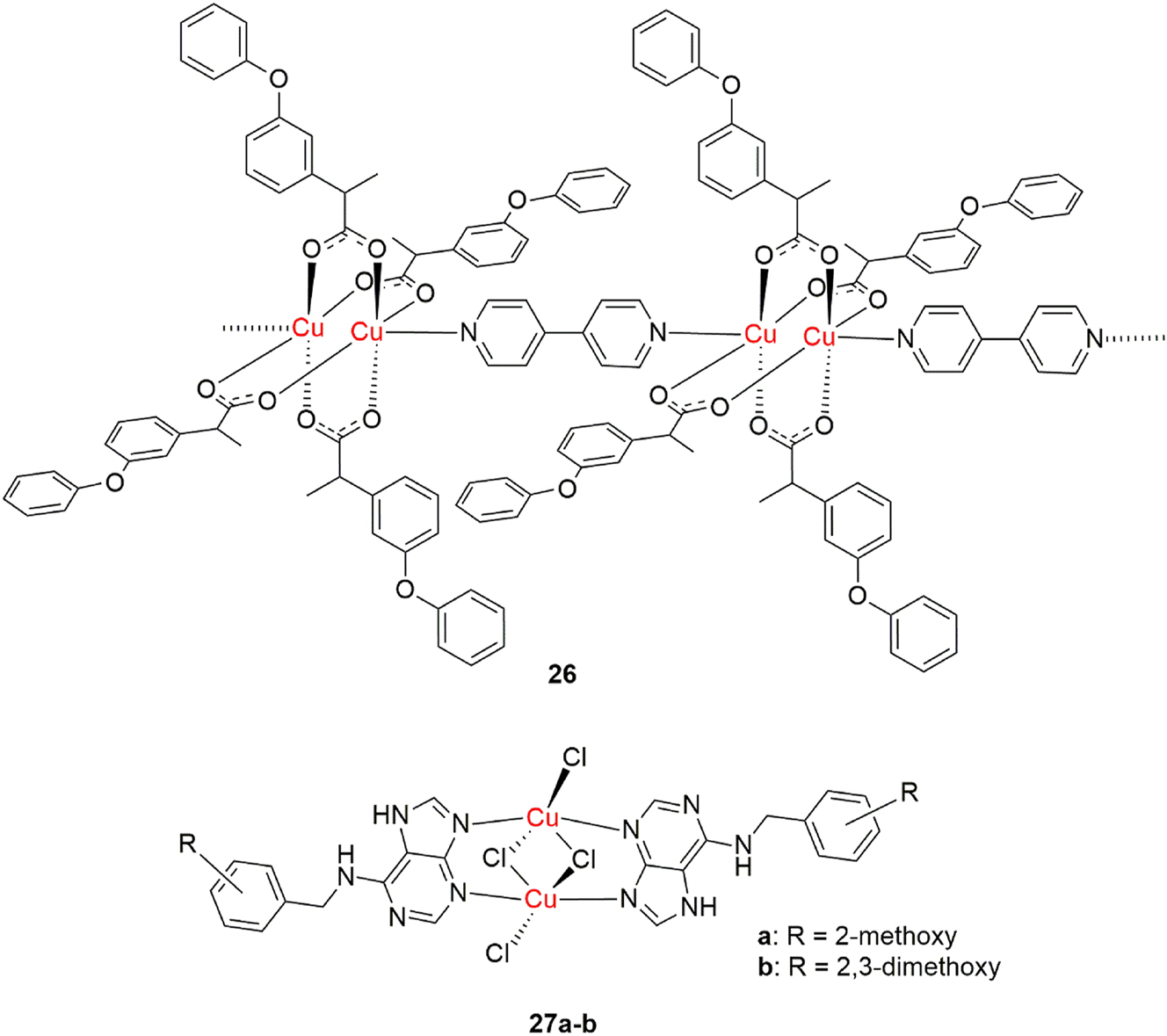

5.1 Dinuclear copper complexes with superoxide dismutase mimicking activity

Copper(II) complexes with NSAIDs, such as fenoprofen, exhibit SOD-mimetic activity, demonstrating potential for enhancing antioxidant properties in oxidative stress therapy. In published research by Agotegaray et al., it was shown that three copper(II) complexes with fenoprofen exhibit higher activity than native bovine Cu/Zn SOD. 135 The fenoprofen copper(II) complex with 4,4′-bipyridine displayed the highest activity (Figure 15, complex 26). In addition to fenoprofen, antioxidant effects of copper(II) complexes with other NSAIDs, such as indomethacin, salicylic acid derivatives and oxaprozin have been investigated. 136 , 137 , 138 These complexes demonstrated significant activity in scavenging superoxide ions, generated by the xanthine/xanthine oxidase system, even greater than that of the uncoordinated drugs. Most notably, the copper(II) indomethacin complex has found use in veterinary medicine.

Antioxidant dinuclear copper(II) complexes.

Antioxidant activity of dinuclear copper(II) complexes with 6-(benzylamino)purine derivatives, synthesized by Štarha et al., was tested in vitro (SOD-mimetic activity) and in vivo (cytoprotective effect against alloxan-induced diabetes in mice). 139 Complex 27a (Figure 15) exhibited exceptional SOD-mimetic activity, surpassing that of the native bovine Cu,Zn-SOD. Complex 27 b also exhibited notable antidiabetic activity, efficiently eliminating free radical metabolites and preventing the rise in blood glucose levels over four days in the alloxan-induced diabetes model. These findings highlight the potential of these complexes for applications in both the prevention and treatment of diseases associated with oxidative stress, including diabetes.

6 Alternative applications

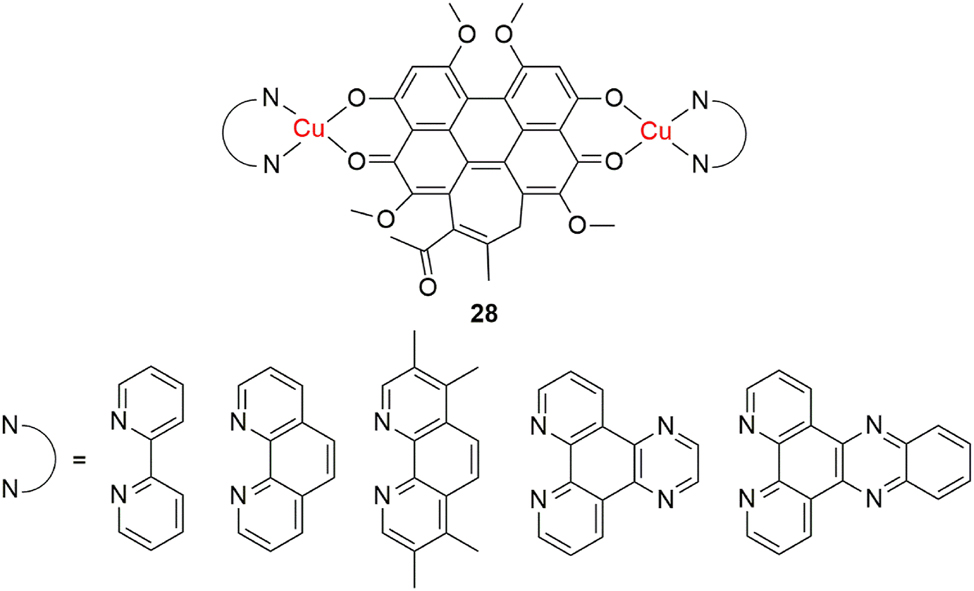

6.1 Dinuclear copper complexes in photodynamic therapy

Apart from rational drug design and discovery, a crucial part, that is integral for the development of therapeutics and pharmacology, is the introduction of novel methodologies and concepts in order to improve medical outcomes. Photodynamic therapy, albeit not so novel, is a form of targeted phototherapy that seems to have very few caveats. 140 It uses non-toxic photosensitizing molecules that are administered either locally or systematically and accumulate in the diseased tissue. Upon radiation, the photosensitizers produce reactive oxygen species that kill the disease afflicted cells. Photodynamic therapy is used in treating skin disorders (such as herpes, psoriasis and acne), age-related macular degeneration, topical microbial infections (which includes drug-resistant bacteria, as well as viral and fungal infections) and various cancers (skin, lung, bladder, neck and head).

Copper(II) complexes, with their redox potential, have sternly placed themselves on the frontline of photodynamic therapy-related research. 141 Using conventional photosensitizers comes with several drawbacks, such as limited solubility, prolonged patient photosensitivity and limited absorption in the phototherapeutic wavelength window of 600–900 nm. These drawbacks can be significantly improved with metalation. 142 Sun et al. expand upon this in their paper, where they report increased photonuclease activity of dinuclear copper(II) complexes of hypocrellin B, a natural product used as a photosensitizer (Figure 16, 28). 143 The complexes exhibited better water solubility, higher absorptivity, as well as higher binding affinity towards double-stranded DNA than uncoordinated hypocrellin B. These results open a window of opportunity for the development of more efficient photosensitizers with enhanced photodynamic activity and improved and broader clinical applicability.

Photodynamic dinuclear copper(II) complexes.

6.2 The possibility of using dinuclear copper complexes topically

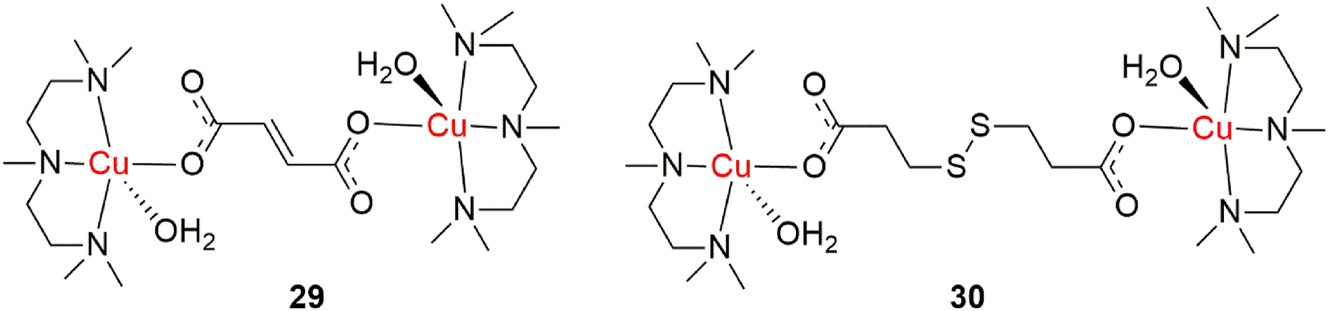

In the second chapter of this review, plenty has been said about antimicrobial activities of dinuclear copper complexes. In order to determine in which way a bioactive compound can be applied pharmacologically, it is important to consider its interactions and activities with important biomolecules that the bioactive compound is bound to encounter on its biochemical journey. Human liver drug-metabolizing cytochromes P450 (CYP) are one of the most important biomolecules that any bioactive molecule interacts with, as they are key enzymes in the initial phase of metabolism of any drug. 144 CYPs are located in the endoplasmatic reticulum membrane in most tissues of the human body and their role is the initial transformation of any drug into its more polar metabolite. It is important to study interactions of drugs and promising drug candidates with these enzymes in order to determine whether these interactions are responsible for undesirable drug-drug interactions with other medications and to determine the best possible mode of administration that prevents these unwanted interactions. Špičáková et al. report this in their findings, as they study interactions of dinuclear copper complexes with liver drug-metabolizing CYPs. 145 These N,N,N′,N″,N″-pentamethyldiethylenetriamine copper(II) complexes, bridged with dicarboxylic acids, were found to be promising antibacterial agents (Figure 17, complexes 29 and 30). 146 It was discovered that the complexes potently inhibited the activities of CYP2C8, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 enzymes and that this would most likely cause unwanted drug-drug interactions with other prescribed and administered drugs. Because of this, it is best that these antimicrobial agents are applied in some sort of topical formulation. These results highlight the impontance of a holistic approach in drug discovery, as there are many limiting factors that intercept the path that a compound has to take from the laboratory to the patient.

Antibacterial dinuclear copper(II) complexes.

7 Limitations, prospects and future perspectives

7.1 Toxicity and limitations in the medicinal applications of dinuclear copper complexes

Although copper is an essential trace element, involved in multiple aspects of redox biology, respiration and enzyme function, when copper levels exceed homeostatic levels, various toxic effects can arise. 147 Excess copper undergoes redox cycling, catalyzes ROS generation and leads to oxidative stress and widespread biomolecular damage, which results in mutagenesis and apoptosis of healthy cells. High copper levels also negatively impact mitochondrial membrane potential and disrupt the electron transport chain, which leads to ATP depletion, induction of apoptosis and systemic toxicity. Copper also binds to various proteins throughout the body, causing structural distortion and aggregation, which leads to proteotoxic stress and neurodegradation. Excessive copper intake causes systemic toxicity and organ damage. Liver and kidneys are particularly vulnerable, due to their central role in copper clearance and metabolism. Copper overload can cause hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity and hemolysis, limiting the therapeutic window of copper-based drugs.

Beyond toxicity issues, other factors that influence the absorption, distribution, metabolism and clearance of dinuclear copper complexes can limit their therapeutic applicability. Many copper complexes suffer from poor oral bioavailability and administration route constraints, as many of them are polar, poorly membrane-permeable, or unstable in gastric/intestinal fluids, so oral absorption is low and parenteral administration (IV) is often required. Parenteral dosing increases systemic exposure and can worsen organ accumulation. 62 After entering the bloodstream, exogenous Cu(II) species (or released Cu ions) rapidly interact with high-abundance carriers (albumin, ceruloplasmin, α-2-macroglobulin) or form ternary species. This reduces free drug concentration, alters tissue distribution, and complicates pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships for dinuclear complexes, that rely on intact structure for activity. 148 , 149 Exchange with biological ligands in serum also reduces tumor delivery of the intact dinuclear species. Dinuclear copper complexes could have limited metabolic stability through biotransformation by plasma and hepatic enzymes. Ligand exchange, reductive/oxidative transformations and metabolic modifications can break dinuclear assemblies or convert them into species with different activity and toxicity. Metabolic lability shortens effective exposure and may produce reactive species that cause off-target toxicity. 150 , 151 The liver is a major sink for circulating copper and many metallodrugs and rapid clearance through hepatic uptake, biliary excretion and renal filtration could cause issues. Hepatic uptake through copper transporters and endocytosis and subsequent biliary excretion reduce systemic half-life and may cause hepatotoxicity. Low molecular weight, hydrophilic degradation products are more readily filtered by the kidneys, shortening exposure to the intact dinuclear complex. Both clearance pathways limit exposure and complicate dosing. 149

7.2 Mitigating copper toxicity, targeted delivery and stimuli-responsive systems

Mitigating copper overload is crucial for developing copper complexes as clinically viable therapeutic agents. Rational ligand design, prodrug strategies and nanomedicine approaches are being utilized to improve therapeutic prospects. Before anything else, fine-tuning the design of ligands in the complex and modulating its overall stability can significantly impact its overall toxicological profile. Stronger chelation can prevent premature copper release in plasma, while tuning lability can ensure controlled release inside cells. Designing sterically hindered ligands can increase ligand rigidity, reduce premature copper release in serum, while enhancing selective DNA cleavage activity in tumor cells. 152 Ligand design can also modulate the Cu(II)/Cu(I) redox potential to favor ROS generation in cancer cells without uncontrolled systemic oxidation. 84

The first step to mitigate copper toxicity beyond design strategies is developing therapeutics with improved selective targeting. Cancer cells often show dysregulated copper homeostasis and overexpression of copper transporters (for example, high affinity copper uptake protein 1 and copper-transporting ATPase 1 and 2). Designing complexes that exploit these differences would enhance tumor accumulation. The aforementioned Casiopeínas® show strong antiproliferative activity but dose-dependent systemic toxicity due to conjugation with tumor-targeting ligands. 63 Bioconjugation can also improve selective targeting, because ligands can be tethered to tumor-targeting moieties (peptides, antibodies, folate, hyaluronic acid), increasing selectivity toward malignant cells, while sparing normal tissues. For example, attaching copper chelators to RGD peptides improves targeting of αvβ3 integrin-expressing cancer cells, enhancing tumor selectivity, while lowering systemic toxicity. 60

Prodrugs are another versatile method for selective targeting. They are inactive forms of bioactive compounds that, after intake, are converted to their pharmacologically active forms, when they reach their intended target. Redox-activated prodrugs, for example, are stable in circulation, but are reduced in the tumor microenvironment and release cytotoxic copper ions only at the tumor site. Redox-activated Cu(II)–phenanthroline complexes, designed to remain inert in plasma, but release ROS-generating Cu(I) inside the reductive tumor microenvironment, can minimize copper overload in normal tissues. 153 Enzyme-responsive copper prodrugs, through conjugation with enzyme-cleavable linkers (cathepsin B-sensitive peptides), could allow copper release specifically in tumor lysosomes. 154

Controlled release nanocarriers could also mitigate copper overload, as encapsulation of copper complexes in liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, or dendrimers allows controlled release, reduces systemic exposure and exploits enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) in tumors. Liposome-encapsulated Casiopeínas® enhance delivery, reduce hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity, while maintaining anticancer efficacy in vivo, by controlling copper release and exploiting the tumor EPR effect. 63

Finally, post-treatment detoxification through chelation therapy can reduce negative toxic side effects of copper. Administration of copper chelators (for example, D-penicillamine, trientine or tetrathiomolybdate) post-treatment can mitigate systemic copper overload, while preserving the anticancer action during therapy. This mirrors strategies for treating Wilson’s disease, but are adapted to oncology. 155

Because copper complexes suffer from issues, such as premature drug release in circulation, non-selective accumulation in liver and kidneys and short plasma half-life and unpredictable biodistribution, there is a clear need for stimuli-responsive delivery systems, that can activate the drug only in tumor tissue, protecting healthy organs and enhancing selectivity. There are a few different stimuli-responsive systems, such as redox-responsive systems, pH-responsive systems, enzyme-responsive systems and light-responsive systems and dinuclear copper complexes could potentially be designed to activate in any of these manners. Tumor microenvironments are reductive due to high glutathione levels. Dinuclear copper complexes could be engineered with redox-sensitive ligands or carriers that release active species upon glutathione reduction. This would exploit cancer-specific redox imbalance while sparing normal cells. Tumors and intracellular compartments (endosomes, lysosomes) are acidic. Dinuclear copper complexes could be stabilized in neutral blood pH, but released under acidic conditions. Many tumors overexpress specific proteases. Dinuclear copper complexes could be conjugated to enzyme-cleavable peptide linkers, releasing the active complex selectively in tumor lysosomes. Copper complexes can act as photosensitizers for ROS generation. Dinuclear systems with photo-cleavable ligands could be activated by light at tumor sites, allowing spatially controlled cytotoxicity.

7.3 Prospects in using dinuclear copper complexes in personalized and combination therapy

Dinuclear copper complexes exert their activities primarily through ROS generation, DNA cleavage, and protein targeting, but their efficacy and toxicity could vary with patient-specific factors. Copper metabolism status can vary, as tumor types differ in expression of copper transporters, metallochaperones, and copper-dependent enzymes. Tumor redox environment, which is high in glutathione levels in some tumors, can quench ROS and deactivate copper complexes. Genetic profiles of patients vary, as sensitivity to copper-induced cuproptosis depends on mitochondrial metabolism and lipoic acid–dependent TCA cycle proteins.

Dinuclear copper complexes could synergize with multiple therapeutic classes, such as chemotherapy, different targeted therapies and immunotherapy. In chemotherapy, dinuclear copper complexes could overcome platinum resistance by damaging DNA through alternative pathways (ROS-mediated cleavage, topoisomerase inhibition), providing additional DNA damage and ROS stress. They could also be combined in targeted therapies. For example, with glutathione-depleting drugs, as they could potentiate ROS-driven cytotoxicity of dinuclear copper complexes, or with metabolic inhibitors, as they could enhance cuproptosis by weakening cellular antioxidant defenses. In immunotherapy, dinuclear copper complexes could synergize with checkpoint inhibitors, enhancing T-cell activation by increasing ROS and causing immunogenic cell death.

Dinuclear copper complexes could be strong candidates for precision therapy. In personalized therapy, they could be used to tailor patient-specific tumor copper biology, redox status, and metabolic vulnerabilities. In combination therapy, they could act as potent ROS amplifiers and DNA-damaging agents, complementing chemotherapy, metabolic inhibitors, and immunotherapies. With the aid of stimuli-responsive delivery systems and biomarker-driven patient selection, dinuclear copper complexes may transition from preclinical promise to clinically useful, individualized treatments.

8 Conclusions

As this overview reaches its conclusion, we hope that this paper helps in establishing a new appreciation for dinuclear copper complexes. Bioinorganic chemistry is still a growing field and copper complexes have certainly made their impact in therapeutics, pharmacology and medicine as a whole. The unique combination of copper chemistry and dinuclear structural modulations have produced many interesting compounds with notable biological activities and substantial therapeutic potentials. The biological activities of dinuclear copper complexes synthesized so far, described in this review and the results therein could provide strategic pathways in developing new and improved therapeutics and treatment options for numerous diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Ministry of science, innovation and technological development of the Republic of Serbia for support (contract numbers 451-03-136/2025-03/200378 and 451-03-137/2025-03/200252).

-

Research ethics: Not applicable.

-

Informed consent: Not applicable.

-

Author contributions: The authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Use of Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools: No Large Language Models, AI and Machine Learning Tools were used in the making of this manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Research funding: None declared.

-

Data availability: Not applicable.

References

1. Grygorenko, O. O.; Volochnyuk, D. M.; Ryabukhin, S. V.; Judd, D. B. The Symbiotic Relationship Between Drug Discovery and Organic Chemistry. Chem. Eur J. 2020, 26 (6), 1196–1237. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201903232.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Karges, J.; Stokes, R. W.; Cohen, S. M. Metal Complexes for Therapeutic Applications. Trends Chem. 2021, 3 (7), 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trechm.2021.03.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Abdolmaleki, S.; Aliabadi, A.; Khaksar, S. Bridging the Gap Between Theory and Treatment: Transition Metal Complexes as Successful Candidates in Medicine. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 531, 216477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2025.216477.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Tsang, T.; Davis, C. I.; Brady, D. C. Copper Biology. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31 (9), R421–R427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.054.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Collins, J. F.; Prohaska, J. R.; Knutson, M. D. Metabolic Crossroads of Iron and Copper. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68 (3), 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00271.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Guo, X.; Lin, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Peng, Y.; He, X.; Liu, J. Integrated Metabolomic and Microbiome Analysis Identifies Cupriavidus metallidurans as a Potential Therapeutic Target for β-Thalassemia. Ann. Hematol. 2024, 103 (12), 5169–5179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-024-06016-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

7. Chen, L.; Min, J.; Wang, F. Copper Homeostasis and Cuproptosis in Health and Disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7 (1), 378. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01229-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Vahedi Nemani, A.; Ghaffari, M.; Sabet Bokati, K.; Valizade, N.; Afshari, E.; Nasiri, A. Advancements in Additive Manufacturing for Copper-Based Alloys and Composites: A Comprehensive Review. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8 (2), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp8020054.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Guo, P.; Wu, Y.; Ma, X.; Chen, R.; Zeng, Z.; Li, L.; Su, C.; Wang, S. Enhanced Iodine Capture by Nano-Copper Particles Modified Benzimidazole-Based Molded Porous Carbon. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 708, 163754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2025.163754.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Soleiman-Beigi, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Kohzadi, H. An Overview on Copper in Industrial Chemistry: from Ancient Pigment to Modern Catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 529, 216438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2025.216438.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Lyu, C.; Li, X.; Sun, X.; Yin, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, J. Inhibitory Effect of Zinc on Fermentative Hydrogen Production: Insight into the Long-Term Effect. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 110, 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2025.02.239.Suche in Google Scholar

12. Zhao, L.; Liao, M.; Li, L.; Chen, L.; Zhang, T.; Li, R. Cadmium Activates the Innate Immune System Through the AIM2 Inflammasome. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2024, 399, 111122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2024.111122.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

13. Ashraf, J.; Riaz, M. A. Biological Potential of Copper Complexes: a Review. Turkish J. Chem. 2022, 46 (3), 595–623. https://doi.org/10.55730/1300-0527.3356.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Fabra, D.; Amariei, G.; Ruiz-Camino, D.; Matesanz, A. I.; Rosal, R.; Quiroga, A. G.; Horcajada, P.; Hidalgo, T. Proving the Antimicrobial Therapeutic Activity on a New Copper–Thiosemicarbazone Complex. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21 (4), 1987–1997. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.3c01235.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Dragojević, J. S.; Milanović, Ž.; Matić, J.; Divac, V. M.; Kosanić, M.; Milivojević, D.; Petković, M.; Singh, F. V.; Kostić, M. D. Dual Activity of Newly Synthesized Zn(II) and Cu(II) Schiff Base Complexes as a Potential Solution for Global Challenges in the Fight Against Priority Microorganisms. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1335, 142052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2025.142052.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Arthi, P.; Dharmasivam, M.; Kaya, B.; Rahiman, A. K. Multi-Target Activity of Copper Complexes: Antibacterial, DNA Binding, and Molecular Docking with SARS-CoV-2 Receptor. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2023, 373, 110349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2023.110349.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

17. Frota, H. F.; Lorentino, C. M. A.; Barbosa, P. F.; Ramos, L. S.; Barcellos, I. C.; Giovanini, L.; Souza, L. O. P.; Oliveira, S. S. C.; Abosede, O. O.; Ogunlaja, A. S.; Pereira, M. M.; Branquinha, M. H.; Santos, A. L. S. Antifungal Potential of the New Copper(II)-Theophylline/1,10-Phenanthroline Complex Against Drug-Resistant Candida Species. Biometals 2024, 37 (2), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10534-023-00549-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Srivastava, A. Antiviral Activity of Copper Complexes of Isoniazid Against RNA Tumor Viruses. Resonance 2009, 14 (8), 754–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12045-009-0072-y.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Bursalı, F.; Yavaşer Boncooğlu, R.; Fırıncı, R.; Fırıncı, E. Synthesis, Characterization, Larvicidal and Antioxidant Activities of Copper(II) Complexes with Barbiturate Derivatives. Monatsh. Chem. 2023, 154 (7), 793–799; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00706-023-03081-4.Suche in Google Scholar

20. Wang, Y.; Tang, T.; Yuan, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, X.; Guan, J. Copper and Copper Complexes in Tumor Therapy. ChemMedChem 2024, 19 (11), e202400060. https://doi.org/10.1002/cmdc.202400060.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

21. Balsa, L. M.; Solernó, L. M.; Rodriguez, M. R.; Parajón-Costa, B. S.; Gonzalez-Baró, A. C.; Alonso, D. F.; Garona, J.; León, I. E. Cu(II)-Acylhydrazone Complex, a Potent and Selective Antitumor Agent Against Human Osteosarcoma: Mechanism of Action Studies over in Vitro and in Vivo Models. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2023, 384, 110685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2023.110685.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

22. Menezes, L. B.; Sampaio, R. M. S. N.; Meurer, L.; Szpoganicz, B.; Cervo, R.; Cargnelutti, R.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Prabhakar, R.; Fernandes, C.; Horn, A. A Multipurpose Metallophore and its Copper Complexes with Diverse Catalytic Antioxidant Properties to Deal with Metal and Oxidative Stress Disorders: a Combined Experimental, Theoretical, and in Vitro Study. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63 (32), 14827–14850. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c00232.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Zapata-Catzin, G. A.; Zumbardo-Bacelis, G. A.; Vargas-Coronado, R.; Xool-Tamayo, J.; Arana-Argáez, V. E.; Cauich-Rodríguez, J. V. Novel Copper Complexes-Polyurethane Composites that Mimics Anti-inflammatory Response. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2023, 34 (8), 1067–1089. https://doi.org/10.1080/09205063.2022.2155783.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Grünspan, L. D.; Mussulini, B. H. M.; Baggio, S.; dos Santos, P. R.; Dumas, F.; Rico, E. P.; de Oliveira, D. L.; Moura, S. Teratogenic and Anticonvulsant Effects of Zinc and Copper Valproate Complexes in Zebrafish. Epilepsy Res. 2018, 139, 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.01.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Tuorkey, M. J. F.-A.; Abdul-Aziz, K. K. A Pioneer Study on the Anti-ulcer Activities of Copper Nicotinate Complex [Cucl (HNA)2] in Experimental Gastric Ulcer Induced by Aspirin-Pyloris Ligation Model (Shay Model). Biomed. Pharmacother. 2009, 63 (3), 194–201; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2008.01.015.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Tian, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Diao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Lv, D. Copper–Taurine (CT): a Potential Organic Compound to Facilitate Infected Wound Healing. Med. Hypotheses 2009, 73 (6), 1048–1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2009.06.051.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

27. Toyota, E.; Sekizaki, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Itoh, K.; Tanizawa, K. Amidino-Containing Schiff Base Copper(II) and Iron(III) Chelates as a Thrombin Inhibitor. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 53 (1), 22–26; https://doi.org/10.1248/cpb.53.22.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

28. Shinde, Y.; Patil, R.; Badireenath Konkimalla, V.; Merugu, S. B.; Mokashi, V.; Harihar, S.; Marrot, J.; Butcher, R. J.; Salunke-Gawali, S. Keto-Enol Tautomerism of Hydroxynaphthoquinoneoxime Ligands: Copper Complexes and Topoisomerase Inhibition Activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1262, 133081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.133081.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Uzun, D.; Balaban Gündüzalp, A.; Parlakgümüş, G.; Özmen, Ü. Ö.; Özbek, N.; Aktan, E. Copper(II) Sulfonamide Complexes Having Enzyme Inhibition Activities on Carbonic Anhydrase I: Synthesis, Characterization and Inhibition Studies. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2022, 19 (1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13738-021-02287-9.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Szymański, P.; Frączek, T.; Markowicz, M.; Mikiciuk-Olasik, E. Development of Copper Based Drugs, Radiopharmaceuticals and Medical Materials. Biometals 2012, 25 (6), 1089–1112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10534-012-9578-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

31. Mukherjee, N.; Podder, S.; Mitra, K.; Majumdar, S.; Nandi, D.; Chakravarty, A. R. Targeted Photodynamic Therapy in Visible Light Using BODIPY-Appended Copper (II) Complexes of a Vitamin B6 Schiff Base. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47 (3), 823–835; https://doi.org/10.1039/C7DT03976J.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Lin, R.; Chiu, C.; Hsu, C.; Lai, Y.; Venkatesan, P.; Huang, P.; Lai, P.; Lin, C. Photocytotoxic Copper(II) Complexes with Schiff‐Base Scaffolds for Photodynamic Therapy. Chem. Eur J. 2018, 24 (16), 4111–4120. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201705640.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Franich, A. A.; Đorđević, I. S.; Živković, M. D.; Rajković, S.; Janjić, G. V.; Djuran, M. I. Dinuclear Platinum(II) Complexes as the Pattern for Phosphate Backbone Binding: a New Perspective for Recognition of Binding Modes to DNA. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 27 (1), 65–79; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00775-021-01911-6.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

34. Soldatović, T. V.; Šmit, B.; Mrkalić, E. M.; Matić, S. L.; Jelić, R. M.; Serafinović, M. Ć.; Gligorijević, N.; Čavić, M.; Aranđelović, S.; Grgurić-Šipka, S. Exploring Heterometallic Bridged Pt(II)-Zn(II) Complexes as Potential Antitumor Agents. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2023, 240, 112100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2022.112100.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Ho, C. S.; Wong, C. T. H.; Aung, T. T.; Lakshminarayanan, R.; Mehta, J. S.; Rauz, S.; McNally, A.; Kintses, B.; Peacock, S. J.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C.; Hancock, R. E. W.; Ting, D. S. J. Antimicrobial Resistance: a Concise Update. Lancet Microbe 2024, 100947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanmic.2024.07.010.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Zhang, C.; Fu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, G. Burden of Infectious Diseases and Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in China: a Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2024, 43, 100972; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100972.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

37. Medici, S.; Peana, M.; Nurchi, V. M.; Lachowicz, J. I.; Crisponi, G.; Zoroddu, M. A. Noble Metals in Medicine: Latest Advances. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 284, 329–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2014.08.002.Suche in Google Scholar

38. Song, Y.-L.; Li, Y.-T.; Wu, Z.-Y. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, Antibacterial Assay and DNA Binding Activity of New Binuclear Cu(II) Complexes with Bridging Oxamidate. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008, 102 (9), 1691–1699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.04.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

39. Huang, J.; Shen, Z.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Xu, D.; He, Q. S. Characterization and Biological Activity of Copper Complex. Asian J. Chem. 2013, 25 (4), 2043–2046. https://doi.org/10.14233/ajchem.2013.13294.Suche in Google Scholar

40. Prabu, R.; Vijayaraj, A.; Suresh, R.; Jagadish, L.; Kaviyarasan, V.; Narayanan, V. New Unsymmetric Dinuclear Copper(II) Complexes of Trans-Disubstituted Cyclam Derivatives: Spectral, Electrochemical, Magnetic, Catalytic, Antimicrobial, DNA Binding and Cleavage Studies. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2011, 32 (5), 1669–1678. https://doi.org/10.5012/bkcs.2011.32.5.1669.Suche in Google Scholar

41. Mruthyunjayaswamy, B. H. M.; Ijare, O. B.; Jadegoud, Y. S. Characterization and Biological Activity of Symmetric Dinuclear Complexes Derived from a Novel Macrocyclic Compartmental Ligand. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2005, 16 (4), 783–789. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-50532005000500016.Suche in Google Scholar

42. Chen, R.; Li, B.; Yang, R.-W.; Ma, L.-J.; Zhang, Y. Structural, Computational, Fluorescent Properties and Antibacterial Properties Insights into Perfect Self-Assembly of a Novel Ring-Shaped Dinuclear Copper(Ⅱ) Complex Based on a Bis(Salamo)-Type Ligand. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1330, 141535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2025.141535.Suche in Google Scholar

43. Sevda, ER; Ünver, H.; Dikmen, G. A New Dinuclear Copper(II)-Hydrazone Complex: Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Antibacterial Activity. Lett. Org. Chem. 2023, 20 (4), 376–387. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570178620666221202090558.Suche in Google Scholar

44. Santiago, P. H. de O.; Duarte, E. de A.; Nascimento, É. C. M.; Martins, J. B. L.; Castro, M. S.; Gatto, C. C. A Binuclear Copper(II) Complex Based on Hydrazone Ligand: Characterization, Molecular Docking, and Theoretical and Antimicrobial Investigation. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2022, 36 (1), e6461. https://doi.org/10.1002/aoc.6461.Suche in Google Scholar

45. Soltani, S.; Akhbari, K.; White, J. S. Crystal Structure, Magnetic, Photoluminescence and Antibacterial Properties of Dinuclear Copper(II) Complex. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1214, 128233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128233.Suche in Google Scholar

46. Vlasenko, V. G.; Burlov, A. S.; Koshchienko, Y. V.; Kolodina, A. A.; Chaltsev, B. V.; Zubavichus, Y. V.; Khrustalev, V. N.; Danilenko, T. N.; Zubenko, A. A.; Fetisov, L. N.; Klimenko, A. I. Synthesis, X-Ray Structure and Biological Activity of Mono- and Dinuclear Copper Complexes Derived from N-{2-[(2-Diethylamino(Alkyl)Imino)-Methyl]-Phenyl}-4-Methyl-Benzenesulfonamide. Inorg. 2021, 523, 120408; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ica.2021.120408.Suche in Google Scholar

47. Li, Y.-T.; Zhu, C.-Y.; Wu, Z.-Y.; Jiang, M.; Yan, C.-W. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, Antibacterial Activities, and DNA-Binding Studies of a New μ-Oxamido-Bridged Binuclear Copper(II) Complex. J. Coord. Chem. 2009, 62 (23), 3795–3809. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958970903171078.Suche in Google Scholar

48. You, Z.-L.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Ding, B.-W.; Sun, H.; Hou, P.; Wang, C. Preparation and Structural Characterization of Hetero-Dinuclear Schiff Base Copper(II)–Zinc(II) Complexes and Their Inhibition Studies on Helicobacter pylori Urease. Polyhedron 2011, 30 (13), 2186–2194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poly.2011.05.048.Suche in Google Scholar

49. Uddin, M. N.; Rupa, T. S. S. Characterization and Antibacterial Properties of Some Thiocyanato Bridged Heteronuclear Complexes. ChemXpress 2014, 3 (1), 28–34.Suche in Google Scholar

50. Li, Q.-B.; Xue, L.-W.; Yang, W.-C.; Zhao, G.-Q. A New Cu–Zn Heteronuclear Schiff Base Complex: Synthesis, Structure, and Antimicrobial Activity. Synth. React. Inorg. M. 2013, 43 (7), 822–825; https://doi.org/10.1080/15533174.2012.750342.Suche in Google Scholar