Abstract

This paper examines the military expenditure (milex) economic growth nexus, in selected Balkan and peripheral countries from 1990 to 2022, considering the presence of informality within an institutional framework. Specifically, we employ Principal Components Analysis (PCA) to formulate an index of informality and use the Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares (DOLS) and Fully-Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS) methods to identify the long-run equilibria. To provide a more comprehensive insight, the study also incorporates two types of causality tests – Dumitrescu-Hurlin and Juodis et al. – to determine the direction of the relationships. Our findings indicate that in the long-run milex can be detrimental to economic growth whilst informality boosts it.

![Figure 3:

Evolution (on average) of informality in our sample 1990–2022. Source: Authors’ own calculations [based on data form Elgin and Oztunali (2012) – updated by Elgin et al. (2021) – and Medina and Schneider (2019)].](/document/doi/10.1515/peps-2024-0029/asset/graphic/j_peps-2024-0029_fig_003.jpg)

Evolution (on average) of informality in our sample 1990–2022. Source: Authors’ own calculations [based on data form Elgin and Oztunali (2012) – updated by Elgin et al. (2021) – and Medina and Schneider (2019)].

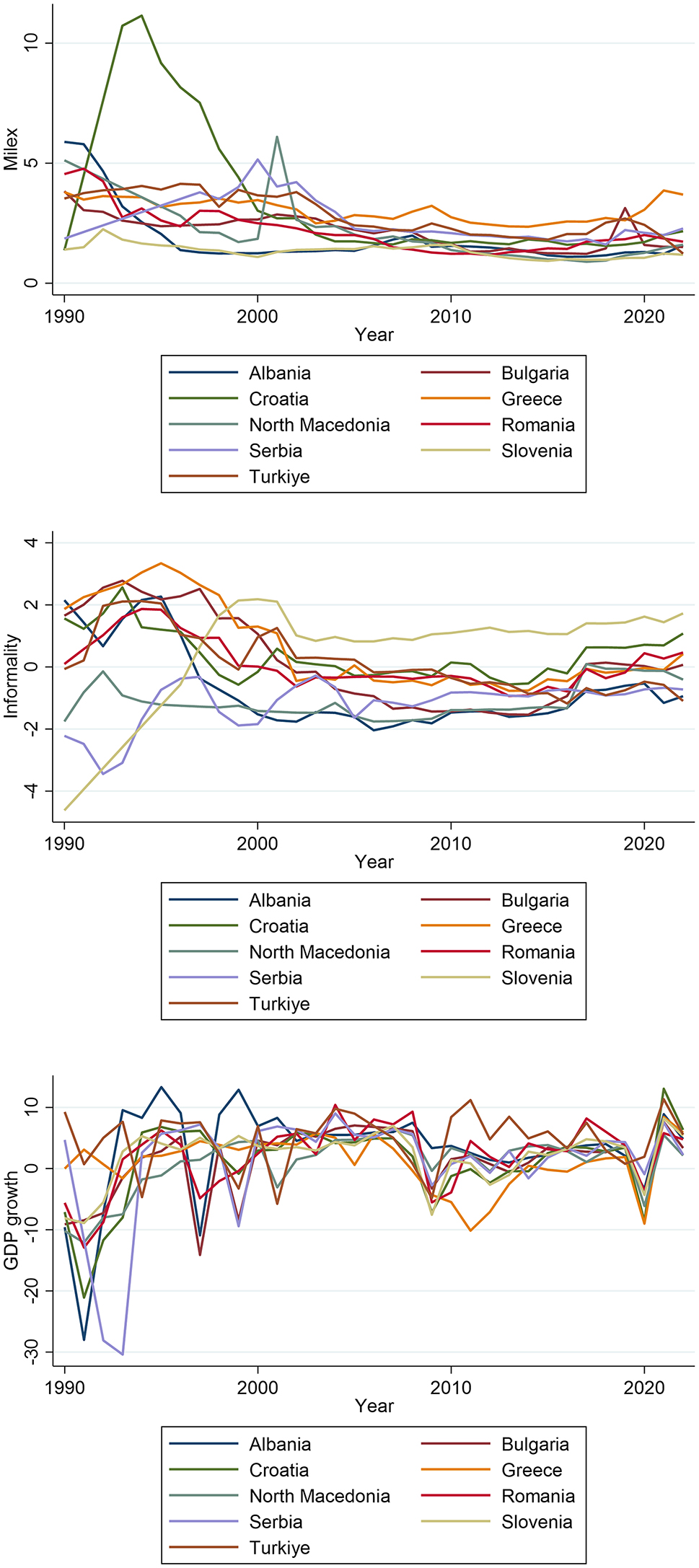

Evolution of Milex, informality, and GDP growth for the sample individual countries 1990–2022. Source: Authors’ processing.

Definitions of variables and sources used for the informalitya index.

| Code | Variable name | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAW | Law and order (index 0–3) | It is scored as a single component with two parts. The risk rating assigned is six points with a minimum of zero. The “Law” element assesses the legal system’s strength and impartiality, while the “Order” element assesses public observance of the law. A nation’s court system may be rated three stars, yet its crime rate may be ranked one star if the law is habitually disregarded without effective enforcement (for instance, massive unlawful strike activity). | The International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) |

| INCONF | Internal conflict (index 0–4) | It assesses the level of political turmoil in the nation and its influence on governance. Most highly rated countries have no armed or civil opposition and no arbitrary violence, direct or indirect, against their own people. A country in a civil war gets the lowest rating. There are three components that make up the risk rating, each with a maximum of four points and a minimum of zero. Four points = Very Low Risk, 0 points = Very High Risk. Terrorism/Political Violence; Civil Disorder. | The International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) |

| BUREAU | Bureaucracy quality | The quality of the bureaucracy acts as a shock absorber, in which it is reducing policy revisions when governments change. Thus, countries with strong bureaucracies that can govern without major policy changes or service interruptions receive high marks. In low-risk countries, the bureaucracy is usually independent of political pressure and has a well-established recruitment and training system. Changes in government are traumatic for policy formulation and day-to-day administrative functions in countries lacking a strong bureaucracy. | The International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) |

| INFLCP | Inflation, consumer prices (annual %) | It quantifies the proportional change in the cost of a set basket of goods and services to the typical consumer over a certain period of time. | World Bank Development Indicators (WDI) |

| MONFREE | Monetary freedom (index 0–100) | It integrates a price stability metric with an evaluation of price regulations. Market activity is distorted by both inflation and price regulations. Without microeconomic interference, price stability is the optimum situation for the free economy. | Euromonitor International |

| TIMEBUS | Time required to start a business (days) | It refers to the time in days required to complete all the formalities for starting a firm lawfully. | World Bank Development Indicators (WDI) |

| POVERTY | Population living below national poverty Line (% population) | It is the percentage of people who live below the country’s poverty threshold. Nationwide calculations are based on sample survey subpopulations estimates. Each nation has its own definition of poverty. | Heritage Foundation |

| CORRUP | Corruption (index 0–6) | This is a political corruption evaluation. Corruption is a danger to foreign capital for numerous reasons: it disrupts the financial and economic atmosphere; it decreases corporate and government efficiency by enabling individuals to obtain power by favour rather than talent; and it adds inherent political turmoil. The risk rating assigned is six points with a minimum of zero. Six points = Very Low Risk, 0 points = Very High Risk. | The International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) |

| INTERNET | Individuals using the Internet (% of the population) | Individuals who have used the internet in the previous three months are considered internet users. The Internet may be accessed via a variety of devices, including computers, mobile phones, PDAs, gaming consoles, and digital televisions. | World Bank Development Indicators (WDI) |

| PRORIG | Property rights (index 0–100) | The property rights component assesses individuals’ ability to accumulate private property. It assesses how well a country’s laws protect private property rights and how well its government enforces them. Additionally, it considers the risk of seizure, the independence of the court, and the capacity of people and enterprises to implement. The score is calculated on a scale of 0–100, with higher values indicating stronger protection of property rights. | The International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) |

| GOVSTAB | Government stability (index 0–4) | It assesses the government’s capacity to deliver and maintain power. Each sub-component of the risk assessment is assigned a maximum of four points and a minimum of zero. Four points = Very Low Risk, 0 points = Very High Risk. There is unity in government, legislative strength, and popular support. | The International Country Risk Guide (ICRG) |

-

aNumerous studies have reached consensus regarding the determinants of informal economy as being economic, political and institutional factors (Chen, Schneider, and Sun 2020; La Porta and Shleifer 2014; Medina and Schneider 2018).

References

Abu Alfoul, M. N., I. N. Khatatbeh, and F. Jamaani. 2022. “What Determines the Shadow Economy? an Extreme Bounds Analysis.” Sustainability 14 (10): 5761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14105761.Suche in Google Scholar

Aizenman, J., and R. Glick. 2006. “Military Expenditure, Threats and Growth.” Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 15 (2): 129–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638190600689095.Suche in Google Scholar

Azam, M. 2020. “Does Military Spending Stifle Economic Growth? the Empirical Evidence from Non-OECD Countries.” Heliyon 6 (12): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05853.Suche in Google Scholar

Azam, M., and Y. Feng. 2015. “Does Military Expenditure Increase External Debt? Evidence from Asia.” Defence and Peace Economics 28 (5): 550–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2015.1072371.Suche in Google Scholar

Bahmani-Oskooee, M., and G. G. Goswami. 2006. “Military Spending and the Black Market Premium in Developing Countries.” Review of Social Economy 64 (1): 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346760500530169.Suche in Google Scholar

Baumol, W. J. 1990. “Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive and Destructive.” Journal of Political Economy 98 (7): 893–921. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)00014-X.Suche in Google Scholar

Baumol, W. J., and A. Blinder. 2008. Macroeconomics: Principles and Policy. Cincinnati: South-Western Publishing.Suche in Google Scholar

Benoit, E. 1978. “Growth and Defence in Developing Countries.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 26 (2): 271–80. https://doi.org/10.1086/451015.Suche in Google Scholar

Bovi, M., and R. Dell’Anno. 2010. “The Changing Nature of the OECD Shadow Economy.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 20: 19–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-009-0138-8.Suche in Google Scholar

Chen, H., F. Schneider, and Q. Sun. 2020. “Measuring the Size of the Shadow Economy in 30 Provinces of China over 1995–2016: The MIMIC Approach.” Pacific Economic Review 25 (3): 427–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0106.12313.Suche in Google Scholar

Chudik, A., and M. H. Pesaran. 2012. “Large Panel Data Models with Cross-Sectional Dependence: A Survey.” CAFE Research Paper 13.15 (2013). Also available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2316333.10.2139/ssrn.2316333Suche in Google Scholar

Compton, R. A., and B. Paterson. 2016. “Military Spending and Growth: The Role of Institutions.” Defence and Peace Economics 27 (3): 301–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2015.1060022.Suche in Google Scholar

d’Agostino, G., J. P. Dunne, and L. Pieron. 2017. “Does Military Spending Matter for Long-Run Growth?” Defence and Peace Economics 28 (4): 429–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2017.1324723.Suche in Google Scholar

Darwanto, D. 2018. “Analysis of Institutional Quality Influence on Shadow Economy Development.” JEJAK: Jurnal Ekonomi dan Kebijakan 11 (1): 49–61. https://doi.org/1015294/jejak.10.15294/jejak.v11i1.11322Suche in Google Scholar

De Soto, H. 2001. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. London: Black Swan.Suche in Google Scholar

Dell’Anno, R. 2022. “Theories and Definitions of the Informal Economy: A Survey.” Journal of Economic Surveys 36 (5): 1610–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12487.Suche in Google Scholar

Dimitraki, O., and K. Emmanouilidis. 2023. “Analysis of the Economic Effects of Defence Spending in Spain: A Re-examination through Dynamic ARDL Simulations and Kernel-Based Regularized Least Squares.” Defence and Peace Economics: 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2023.2245698.Suche in Google Scholar

Dimitraki, O., and K. Emmanouilidis. 2024. “Interactional Impact of Defence Expenditure and Political Instability on Economic Growth in Nigeria: Revisited.” Defence and Peace Economics: 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2024.2354992.Suche in Google Scholar

Dreher, A., C. Kotsogiannis, and S. McCorriston. 2009. “How Do Institutions Affect Corruption and the Shadow Economy?” International Tax and Public Finance 16: 773–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-008-9089-5.Suche in Google Scholar

Dumitrescu, E. I., and C. Hurlin. 2012. “Testing for Granger Non-causality in Heterogeneous Panels.” Economic Modelling 29 (4): 1450–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2012.02.014.Suche in Google Scholar

Elbahnasawy, N., M. Ellis, and A. Adom. 2016. “Political Instability and the Informal Economy.” World Development 85 (C): 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.04.009.Suche in Google Scholar

Elgin, C., and O. Oztunali. 2012. “Shadow Economies Around the World: Model Based Estimates.” Bogazici University Department of Economics Working Papers, Vol. 5, 1–48.Suche in Google Scholar

Elgin, C., M. Kose, F. Ohnsorge, and S. Yu. 2021. “DP16497- Understanding Informality.” CEPR Discussion Paper No. 16497. Paris: CEPR Press. Also available at: https://cepr.org/publications/dp16497.10.2139/ssrn.3916568Suche in Google Scholar

Erić, O. 2018. “Education and Economic Growth of the Western Balkans Countries.” Economics-Innovative and Economics Research Journal 6 (2): 27–35. https://doi.org/10.2478/eoik-2018-0021.Suche in Google Scholar

Fedotenkov, I., and F. Schneider. 2018. “Military Expenditures and Shadow Economy in the Central and Eastern Europe: Is There a Link?” Central European Economic Journal 5 (52): 142–53. https://doi.org/10.1515/ceej-2018-0016.Suche in Google Scholar

Feige, E. L. 1997. “Underground Activity and Institutional Change: Productive, Protective and Predatory Behaviour in Transition Economies.” In Transforming Post-Communist Political Economies, edited by J. Nelson, C. Tilly, and L. Walker, 21–35. Washington: National Academy Press.10.2139/ssrn.3400240Suche in Google Scholar

Friedman, E., S. Johnson, D. Kaufmann, and P. Zoido-Lobaton. 2000. “Dodging the Grabbing Hand: The Determinants of Unofficial Activity in 69 Countries.” Journal of Public Economics 76 (3): 459–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(99)00093-6.Suche in Google Scholar

Gianaris, N. V. 1996. Geopolitical and Economic Changes in Balkan Countries. London: Praeger.Suche in Google Scholar

Glenny, M. 2012. The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804-2012: New and Updated. Toronto: House of Anansi Press Incorporated.Suche in Google Scholar

Goel, R. K., and J. W. Saunoris. 2014. “Military versus Non-military Government Spending and the Shadow Economy.” Economic Systems 38 (3): 350–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-013-0135-1.Suche in Google Scholar

Goel, R. K., J. W. Saunoris, and F. Schneider. 2017. “Drivers of the Underground Economy Around the Millennium: A Long Term Look for the United States.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 10857. Also available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2998966.10.2139/ssrn.2998966Suche in Google Scholar

Goel, R. K., J. W. Saunoris, and F. Schneider. 2019. “Growth in the Shadows: Effect of the Shadow Economy on US Economic Growth over More Than a Century.” Contemporary Economic Policy 37 (1): 50–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12288.Suche in Google Scholar

Hart, K. 2008. “Informal Economy.” In The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, edited by S. N. Durlauf, and L. E. Blume, 845–6. Palgrave Macmillan.10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_804-2Suche in Google Scholar

Heintz, J. 2012. Informality, Inclusiveness, and Economic Growth: An Overview of Key Issues. Amherst: Univ Massachusetts.Suche in Google Scholar

Iacobuta-Mihaita, A. O., C. Pintilescu, R. I. Clipa, and M. Ifrim. 2022. “Institutional Drivers of Shadow Economy. Empirical Evidence from CEE Countries.” Revista de Economia Mundial 60: 67–100. https://doi.org/10.33776/rem.v0i60.5620.Suche in Google Scholar

Im, K. S., M. H. Pesaran, and Y. Shin. 2003. “Testing for Unit Roots in Heterogeneous Panels.” Journal of Econometrics 115 (1): 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(03)00092-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Joo, D. 2011. “Determinants of the Informal Sector and Their Effects on the Economy: The Case of Korea.” Global Economic Review 40 (1): 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/1226508X.2011.559326.Suche in Google Scholar

Juodis, A., and S. Reese. 2022. “The Incidental Parameters Problem in Testing for Remaining Cross-Section Correlation.” Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 40 (3): 1191–203, https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.2021.1906687.Suche in Google Scholar

Juodis, A., Y. Karavias, and V. Sarafidis. 2021. “A Homogeneous Approach to Testing for Granger Non-causality in Heterogeneous Panels.” Empirical Economics 60 (1): 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-020-01970-9.Suche in Google Scholar

Kalaš, B., V. Mirović, and N. Milenković. 2021. “Panel Cointegration Analysis of Military Expenditure and Economic Growth in the Selected Balkan Countries.” Economic Themes 59 (3): 375–90. https://doi.org/10.2478/ethemes-2021-0021.Suche in Google Scholar

Kanniainen, V., J. Pääkönen, and F. Schneider. 2004. “Fiscal and Ethical Determinants of Shadow Economy: Theory and Evidence.” Discussion Paper. Linz: Johannes Kepler University of Linz.Suche in Google Scholar

Kao, C. 1999. “Spurious Regression and Residual-Based Tests for Cointegration in Panel Data.” Journal of Econometrics 90 (1): 1–44, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00023-2.Suche in Google Scholar

Kao, C., and M. H. Chiang. 2004. “On the Estimation and Inference of a Cointegrated Regression in Panel Data.” In Nonstationary Panels, Panel Cointegration, and Dynamic Panels. Nonstationary Panels, Panel Cointegration, and Dynamic Panels (Advances in Econometrics, Vol. 15), edited by B. H. Baltagi, T. B. Fomby, and R. Carter Hill, 179–222. Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.10.1016/S0731-9053(00)15007-8Suche in Google Scholar

Kovtun, D., A. M. Cirkel, M. Z. Murgasova, M. D. Smith, and S. Tambunlertchai. 2014. “Boosting Job Growth in the Western Balkans.” International Monetary Fund, WP/14/16.10.5089/9781484391037.001Suche in Google Scholar

La Porta, R., and A. Shleifer. 2014. “Informality and Development.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 28 (3): 109–26. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.28.3.109.Suche in Google Scholar

Lustrilanang, P., S. Darusalam, L. T. Rizki, N. Omar, and J. Said. 2023. “The Role of Control of Corruption and Quality of Governance in ASEAN: Evidence from DOLS and FMOLS Test.” Cogent Business & Management 10 (1): 2154060. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2154060.Suche in Google Scholar

Maddala, G. S., and S. Wu. 1999. “A Comparative Study of Unit Root Tests with Panel Data and a New Simple Test.” Oxford Bulletin of Economics & Statistics 61 (S1): 631–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0084.0610s1631.Suche in Google Scholar

Matthews, R. 2019. The Political Economy of Defence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/9781108348058Suche in Google Scholar

Medina, L., and M. F. Schneider. 2018. Shadow Economies Around the World: What Did We Learn over the Last 20 Years? Washington: International Monetary Fund.10.2139/ssrn.3124402Suche in Google Scholar

Medina, L., and M. F. F. Schneider. 2019. “Shedding Light on the Shadow Economy: A Global Database and the Interaction with the Official One.” CESifo Working Paper No. 7981. Also available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3502028.10.2139/ssrn.3502028Suche in Google Scholar

North, D. C. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9780511808678Suche in Google Scholar

Pedroni, P. 2001. “Fully Modified OLS for Heterogeneous Cointegrated Panels.” In Nonstationary Panels, Panel Cointegration, and Dynamic Panels (Advances in Econometrics, Vol. 15), edited by B. H. Baltagi, T. B. Fomby, and R. Carter Hill, 93–130. Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.10.1016/S0731-9053(00)15004-2Suche in Google Scholar

Pedroni, P. 2004. “Panel Cointegration: Asymptotic and Finite Sample Properties of Pooled Time Series Tests with an Application to the PPP Hypothesis.” Econometric Theory 20 (3): 597–625. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266466604203073.Suche in Google Scholar

Pesaran, M. H. 2007. “A Simple Panel Unit Root Test in the Presence of Cross‐section Dependence.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 22 (2): 265–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.951.Suche in Google Scholar

Pesaran, M. H. 2021. “General Diagnostic Tests for Cross-Sectional Dependence in Panels.” Empirical Economics 60 (1): 13–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-020-01875-7.Suche in Google Scholar

Pesaran, M.H., and Y. Xie. 2021. “A Bias-Corrected CD Test for Error Cross-Sectional Dependence in Panel Data Models With Latent Factors.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.00408. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2109.00408 Suche in Google Scholar

Philips, P. C. B., and B. E. Hansen. 1990. “Statistical Inference in Instrumental Variables Regression with I(1) Process.” The Review of Economic Studies 57 (1): 99–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297545.Suche in Google Scholar

Polese, A., and J. Morris. 2015. “My Name Is Legion: The Resilience and Endurance of Informality beyond, or in Spite of, the State.” In Informality in Post-Socialism, edited by J. Morris, and A. Polese, 39–53. London: Palgrave.Suche in Google Scholar

Sazvar, M., and Z. Nasrollahi. 2022. “Effect of Military Expenses on Shadow Economy in Iran.” Quarterly Journal of Quantitative Economics 19 (3): 33–61. https://doi.org/10.22055/jqe.2021.30345.2125.Suche in Google Scholar

Schneider, M. F. 2010. “The Influence of Public Institutions on the Shadow Economy: An Empirical Investigation for OECD Countries.” Review of Law & Economics 6 (3): 441–68. https://doi.org/10.2202/1555-5879.1542.Suche in Google Scholar

Schneider, F. 2011. Handbook on the Shadow Economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.10.4337/9780857930880Suche in Google Scholar

Schneider, M. F., and D. H. Enste. 2000. “Shadow Economies: Size, Causes, and Consequences.” Journal of Economic Literature 38 (1): 77–114. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.38.1.77.Suche in Google Scholar

Schneider, M. F., and C. C. Williams. 2013. The Shadow Economy. London: The Institute of Economic Affairs.10.2139/ssrn.3915632Suche in Google Scholar

Tanzi, V. 1999. “Uses and Abuses of Estimates of the Underground Economy.” The Economic Journal 109 (456): F338–F347. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00437.Suche in Google Scholar

Toynbee, A., D. Mitrany, D. G. Hogarth, and N. Forbes. 1915. The Balkans: A History of Bulgaria—Serbia—Greece—Rumania—Turkey. Oxford: Clarendon Press.Suche in Google Scholar

Tran, T. K. P. 2024. “Effects of Military Spending on the Size of Shadow Economy: An Empirical Investigation.” ELIT–Economic Laboratory for Transition Research 20 (1): 109–16. https://doi.org/10.14254/1800-5845/2024.20-1.10.Suche in Google Scholar

Tran, T. P. K., P. V. Nguyen, Q. L. H. T. T. Nguyen, N. P. Tran, and D. H. Vo. 2022. “Does National Intellectual Capital Matter for Shadow Economy in the Southeast Asian Countries?” PLoS One 17 (5): 0267328. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267328.Suche in Google Scholar

Veremis, T. 2015. The Modern Balkans: A Concise Guide to Nationalism, Politics, the Rise and Decline of the Nation State. London: LSEE Research on South Eastern Europe.Suche in Google Scholar

Veremis, T. 2017. A Modern History of the Balkans: Nationalism and Identity in Southeast Europe. London: I.B. Tauris.10.5040/9781350985100Suche in Google Scholar

Westerlund, J. 2005. “New Simple Tests for Panel Cointegration.” Econometric Reviews 24 (3): 297–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/07474930500243019.Suche in Google Scholar

Williams, C. C. 2006. The Hidden Enterprise Culture: Entrepreneurship in the Underground Economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.10.4337/9781847201881.00013Suche in Google Scholar

Williams, C. C. 2019. The Informal Economy. Newcastle: Agenda Publishing.10.1017/9781911116325Suche in Google Scholar

Žarković, M., J. Ćetković, and J. Cvijović. 2024. “Economic Growth Determinants in Old and New EU Countries.” Panoeconomicus 19: 1–32. https://doi.org/10.2298/PAN211122007Z.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The Economic Impact of Arms Spending in Germany, Italy, and Spain

- Defense Burden Sharing and Military Cooperation in the EU27: A Descriptive Analysis (2002–2023)

- Is Geopolitical Risk a Reason or Excuse for Bigger Military Expenditures?

- Asymmetric and Threshold Effect of Military Expenditure on Economic Growth: Insight from an Emerging Market

- Letters and Proceedings

- Examining the Military Spending Economic Growth Nexus in the Presence of Informality: Evidence from the Balkan Peninsula

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Research Articles

- The Economic Impact of Arms Spending in Germany, Italy, and Spain

- Defense Burden Sharing and Military Cooperation in the EU27: A Descriptive Analysis (2002–2023)

- Is Geopolitical Risk a Reason or Excuse for Bigger Military Expenditures?

- Asymmetric and Threshold Effect of Military Expenditure on Economic Growth: Insight from an Emerging Market

- Letters and Proceedings

- Examining the Military Spending Economic Growth Nexus in the Presence of Informality: Evidence from the Balkan Peninsula