Abstract

The US campaign for Biak in 1944 was one of the most challenging, albeit little known, operations of the Pacific war. Major General Horace Fuller’s HURRICANE Task Force faced a tenacious enemy determined to hold the island’s three airfields at all costs. Grossly underestimating the number of Japanese defenders on Biak, MacArthur and Kreuger allocated Fuller only two regimental combat teams for the initial invasion in May 1944. Once ashore, the US troops encountered a shift in Japanese tactics from defending at the water’s edge to using inland fukkaku, honeycombed underground defensive positions that masked Japanese troops and artillery. When the task force failed to deliver the airfields as quickly as desired by General Douglas MacArthur, Lieutenant General Walter Krueger relieved Fuller as task force commander and replaced him with Lieutenant General Robert Eichelberger. This article contends that Krueger did not have good cause to relieve Fuller; rather, he simply did so to placate MacArthur, who, for a multitude of reasons, pressured Krueger for a fast victory. I assess flaws in the planning and execution of the operation, MacArthur’s motives, and personality dynamics between MacArthur and Krueger to support my conclusion that Fuller was ultimately a victim of MacArthur’s impatience.

Overshadowed by larger-scale island campaigns such as Guadalcanal and Iwo Jima, the US campaign for Biak (Operation HORLICKS) in the summer of 1944 was one of the toughest operations of the war in the Pacific. Not only did the American troops of HURRICANE Task Force face a tenacious enemy determined to hold the island’s three airfields at all costs, but the equatorial heat, jungle disease, rugged terrain, and a shift in Japanese defensive tactics also challenged the invading US forces. When the landing forces, which were initially undermanned for their mission, failed to deliver the airfields as quickly as desired by General Douglas MacArthur (Commander, South West Pacific Area [SWPA]), Lieutenant General Walter Krueger (Commanding General, Sixth Army and Alamo Force) relieved Major General Horace Fuller as task force commander and replaced him with Lieutenant General Robert Eichelberger (Commanding General, I Corps). I contend that Krueger did not have good cause to relieve Fuller; rather, he simply did so primarily to placate an impatient MacArthur, who not only wanted to return to the Philippines as quickly as possible but also wanted to maintain his public image as a great commander and potential presidential candidate. This little-known episode in a campaign that is one of the least remembered in the Pacific war provides a compelling glimpse into the machinations of the SWPA command.

1 Biak’s Strategic Significance to the Allies – and to Douglas MacArthur

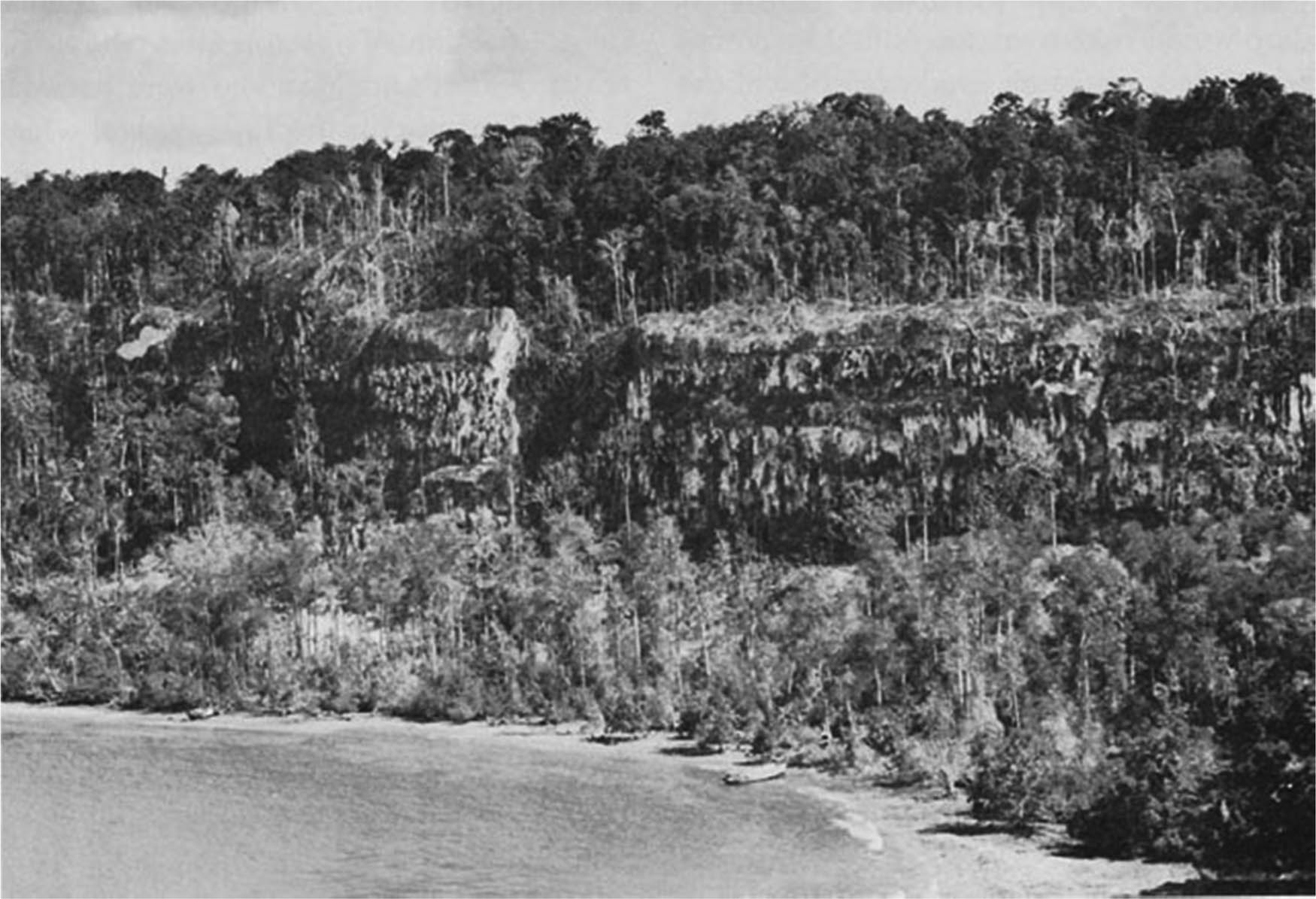

Virtually all historians who have studied the Biak landings in May 1944 describe the island itself as one of the most inhospitable locations imaginable. Situated on the northwest coast of what was then the Netherlands East Indies, Biak is the largest of the Schouten Islands in Geelvink Bay. Fringed by reefs, the island consists mostly of coral ridges and shelves covered by tropical rain forest and jungle overgrowth.[1] The lack of fresh water and abundance of tropical diseases like malaria, scrub typhus, and dysentery afflicted the Japanese and Americans alike. Eichelberger later wrote that no terrain on any other Pacific island was likely tougher than that on Biak, yet the Japanese took these hostile conditions and built themselves “an island stronghold with a considerable claim to impregnability.”[2] By the late spring of 1944, the Japanese had completed three airfields on the south coastal side of the island, close to the shoreline but backed by coral ridges that afforded defenders the opportunity to train fire onto the airstrips. The coral airstrips on Biak provided a surface hard enough to accommodate even heavy bombers. Once destined to be a major air base, Biak was relegated to outpost status in early May 1944 when Japan’s main line of resistance was moved to the west.

Although Japan also valued Biak as a possible fulcrum point for a potential major naval engagement, the three airfields, only 800 miles from major Japanese army and navy bases at Davao, are what gave the island its greatest strategic importance.[3] MacArthur considered the Philippines, which lay on the main sea route between Japan and oil and raw materials in the southwest Pacific, to be the SWPA’s most important strategic objective; indeed, he held no conviction more passionately than his quest to return and liberate the Philippines.[4] Biak was ideally situated to support land-based bomber operations against not only the Philippines but also Japanese naval bases in the western Caroline islands and oil assets in Japanese-occupied Borneo and Sumatra.[5] After Hollandia proved to have inadequate soil to support heavy bombers, MacArthur found himself in even greater need of Biak’s airstrips as a means of fulfilling his pledge to Admiral Chester Nimitz that SWPA would provide land-based bomber support for the Pacific Ocean Area assault on Saipan planned for mid-June 1944.[6]

A quick victory on Biak bore the potential of serving not only Allied strategic goals, but MacArthur’s personal interests as well. Few officers in US military history have matched Douglas MacArthur’s insatiability for public adulation. In the early years of the war, he was wildly popular with the American public, having given them a “badly needed idol at a time when the military altar was almost bare of icons.”[7] Rapid success across northern New Guinea was a means of keeping his name front and center before the American public, perhaps even as a potential presidential candidate. A May 1942 Gallup poll had ranked MacArthur as one of the top four men perceived as “presidential material” for 1944.[8] However, he consistently polled so far behind Thomas Dewey and Wendell Wilkie that his only chance for the Republican nomination lay in the very unlikely event of a deadlock between the two front-runners at the party convention in late June 1944.

Although MacArthur never publicly campaigned for the nomination, he sanctioned the efforts of those willing to do so for him, including his senior staff officers, who met in Washington in 1943 with Senator Arthur Vandenberg (R-Michigan), MacArthur’s most prominent supporter. Notwithstanding MacArthur’s coy demurrals to political aspirations, Eichelberger wrote his wife in mid-June 1943, “My chief talked of the Republican nomination for next year – I can see that he expects to get it and I sort of think so too.”[9] But MacArthur’s “non-campaign” took a critical hit in mid-April 1944 when major newspapers published correspondence between MacArthur and a Republican congressman where MacArthur had disparaged Franklin Roosevelt and the president’s policies. Called out for questioning his commander-in-chief in the midst of war, MacArthur was forced into an unequivocal disavowal of any political aspirations.[10]

2 Hollandia – Prelude to Biak

By early 1944, Allied advances on New Guinea were so successful that the question was not whether the Allies might be able to wrest the remainder of the island from the Japanese, but rather when. The Japanese were unable to replace aircraft, shipping, and manpower losses, while the Allies had more troops; overwhelming air, naval, and logistical superiority; and the strategic and tactical initiative.[11] The sooner MacArthur could secure New Guinea, the sooner he could head for Mindanao, with Nimitz’s operations in the Central Pacific serving as a flanking safeguard for his sweep to the Philippines.[12] Although MacArthur’s Reno IV timetable placed his return to the Philippines in mid-November 1944, he continuously sought ways to accelerate the schedule. Instead of striking next at Wewak, as the Japanese expected, MacArthur “leapfrogged” over Wewak in late April 1944 and landed some 80,000 Allied troops several hundred miles further west at Hollandia.

Eichelberger, commanding general of I Corps, led the two task forces charged with taking Hollandia and Aitape. Both task forces involved units of the 41st Infantry Division (nicknamed the “Jungleers”), which just weeks later would form the core of the HURRICANE Task Force committed at Biak for Operation HORLICKS. The 41st Division, a National Guard unit that had been activated for federal service in September 1940, consisted of the 162nd, 163rd, and 186th infantry regiments. The first division to join the SWPA, it had emerged as one of the theater’s most-respected units.[13] Its three regiments had fought separately in Papua in late 1942 and early 1943 and were ready to return to combat in the spring of 1944. On April 22, 1944, two regiments of the 41st Division landed at Humboldt Bay near Hollandia as part of the RECKLESS Task Force while the third regiment landed at Aitape as the major unit of PERSECUTION Task Force. Japanese resistance during these landings was much lighter than anticipated.

MacArthur’s success in the Hollandia landings spurred him to accelerate his march across northwest New Guinea. He wanted to immediately seize Wadke, a tiny island west of Hollandia that contained a small airfield. This is one of the multiple instances in the war where MacArthur displayed a tendency to conflate putting troops ashore as a victory, notwithstanding the disruption that Japanese resistance might cause his timetable.[14]

Although Eichelberger talked MacArthur out of moving on Wadke quite so rapidly, only 5 days later MacArthur ordered an attack on Wadke and neighboring Sarmi for May 15, 1944, with a view toward invading Biak in early June.[15] Once he learned that the terrain at Sarmi was unsuitable for airstrips, MacArthur modified his strategic plan on May 10, 1944; one regiment of the 41st Division, operating as the 163rd Regimental Combat Team (RCT), would attack Wadke on May 17 and the other two regiments would land at Biak on May 27. The 163rd RCT seized Wadke in 3 days, with a butcher’s bill of fewer than 150 casualties.[16] Biak exacted a much higher toll, with a casualty rate for US troops of 25%; this included 471 soldiers killed, over 2,440 wounded, and several thousand incapacitated by jungle diseases such as scrub typhus and dysentery.[17]

3 Planning for Biak

In planning for HORLICKS, Krueger and his Sixth Army staff had very little intelligence about Biak’s terrain, offshore hydrography, and Japanese defenders.[18] The most critical unknown factors for SWPA planners were the number and composition of Japanese defenders on Biak in late May 1944. The SWPA staff knew that Biak was held by the 222nd Infantry Regiment of the Imperial Japanese Army’s 36th Division, composed of highly experienced troops who had fought in northern China from 1941 until their transfer to the island in October 1943.[19] The planners also knew, thanks to an intercepted ULTRA message on May 10, 1944, that the Japanese defenders on Biak had been ordered to hold the island to the best of their ability.[20] But SWPA chief intelligence officer Brigadier General Charles Willoughby expected only “stubborn, but not serious, enemy resistance.”[21] He grossly underestimated the number of Japanese defenders on Biak at 4,400, of which only 2,500 were combat troops.[22] This estimate is perplexing because Willoughby knew of a message intercepted at the end of April that put Japanese troop strength on Biak either, or soon to be, at 10,800.[23] In fact, the actual strength was approximately 11,400, of which some 4,000 were combat effectives.[24]

Colonel Naoyuki Kuzume, “a soldier of the highest caliber and a tactician compelling respect,” commanded the Imperial Japanese Army’s Biak Detachment.[25] In addition to 3,400 men in the 222nd Infantry Regiment, Kuzume’s forces also included a company of light tanks, various artillery units, and approximately 1,500 men in three airdrome construction units.[26] He also had at his disposal 1,500 naval troops and personnel from approximately two dozen service units. After learning in mid-May that Allied operations against Biak were imminent, Kuzume pulled his troops from airfield construction to focus on fortifying the island, particularly the high ground near Mokmer. Thus, the element of surprise that had so contributed to the rapid success at Hollandia was missing from the Allied invasion of Biak.

Relying on Willoughby’s low estimation of Japanese troop strength on Biak, MacArthur and Krueger imprudently split the 41st Division. The assignment of the 163rd RCT to Wadke left only the division’s other two regiments, the 162nd Infantry and 186th Infantry, as the core of HURRICANE Task Force. Although two divisions had landed at Hollandia, the Biak operation – lacking any element of surprise other than the actual landing date – would have only two reinforced regiments, neither of which were fresh. Those regiments were reinforced by two field artillery battalions, two anti-aircraft battalions, and a tank company (minus one platoon).[27]

Krueger appointed Fuller to serve as HURRICANE Task Force commander in addition to his duties as commanding general of the 41st Division. A classmate in West Point ‘09 and a lifelong friend of Eichelberger’s, Fuller spent the bulk of his career as a field artillery officer. His tour as commandant of the US Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth was cut short to permit him to assume command of the 41st Division in December 1941. By May 1944, Fuller had commanded the 41st Division, whose men held him in high regard, for two and a half years. He had performed well enough in the SWPA that MacArthur had promised him command of I Corps after Eichelberger took command of the soon-to-be-stood-up Eighth Army. But as historian Stephen Taaffe notes, Japanese opposition on Biak and “Krueger’s badgering” doused that plan.[28]

Fuller was uneasy about the composition of the task force. Even before leaving Hollandia, he expressed to Eichelberger his apprehension over its size. Eichelberger felt Fuller’s concerns were understandable given that the American forces would not enjoy the 3-to-1 advantage traditionally considered adequate for an invading force.[29] Fuller also expressed concern that his division was expected to undergo two “full-dress” amphibious operations so close in time to each other.[30] Although the Jungleers had “performed magnificently” at Hollandia, they had little time to prepare for the Biak landings.[31] Roger Lawless, a Signal Corps officer who served on Biak, maintains that once sailing times were set for May 25, the 11th-hour acceleration of HORLICKS left insufficient time for all the events required for an amphibious operation, including detailed planning, rehearsals, staging, and intelligence briefings.[32]

Krueger acknowledged after the war that there had been “little time to gain more than sketchy information of Biak” but made the puzzling decision to forego ground reconnaissance because it purportedly would have tipped Allied intentions.[33] Aerial photographs of Biak showed little except coral terrain. Preliminary bombardment had drawn virtually no return fire because the Japanese had stayed hidden in cave fortifications, some of which were capable of holding hundreds of men. The Allies suspected, correctly, that Mokmer airfield, with five dispersal loops, was the largest and the most heavily defended of the airfields.[34] Bosnek, some eight miles east of the airfield, presented the best choice for a beachhead because there was access to the coastal road leading through mangrove swamps and cliffs to Mokmer and inland trails, as well as suitable maneuver room ashore, two jetties, and no apparent Japanese defense installations.[35] But a host of unknown factors remained about the landing site due to inaccurate maps and a lack of knowledge about tides, winds, current, and offshore conditions.[36]

The Biak landings had been scheduled only 10 days after the Wadke landings to enable a heavy bomber group to commence operations from Biak in support of Nimitz’s Central Pacific invasion of the Marianas on June 15.[37] MacArthur thought that the two US RCTs, consisting of 15,677 combat and 5,082 service troops, were capable of capturing the airfields by June 10.[38] However, no such deadline was written into the actual operation plans; Sixth Army Field Order No. 17, dated 12 May 1944, simply ordered HURRICANE Task Force to land near Bosnek, establish a beachhead, and then “quickly seize and occupy Mokmer, Borokoe and Sorido airdromes […].” Similarly, Fuller told his two regimental commanders that the airfields needed to be seized “rapidly.”[39] Unfortunately for Fuller, this vague timeline – which anticipated that the airfields could be wrested from Japanese defenders, repaired of pre-invasion aerial and naval bombardment damage, and stood up for heavy bomber operations within 12 days after US troops landed came ashore on Biak – took on the illusion of a hard deadline.

4 Operation HORLICKS Commences

The extensive aerial and naval gunfire that preceded the landings on Biak caused some American infantrymen who landed on May 27, 1944, to question whether any Japanese could have survived the bombardment.[40] Biak initially seemed as though it would be as relatively easy as the landings at Hollandia and Aitape had been. However, rather than waiting on the beaches, the Japanese forces were patiently waiting inland in the honeycombed natural coral defenses that Kuzume had fortified with pillboxes, bunkers, and mortar emplacements. Knowing that the airstrips were honey pots, Kuzume intended to lure the invading troops into decimating fire from his troops ensconced on the hills and in the caves.[41] Colonel Joseph Alexander describes these underground, honeycombed reinforced sites as fukkaku positions; although they had been used as early as 1942, it was not until Biak that the Japanese developed them “to a disturbingly systematic level.”[42] Biak was a precursor to the Japanese army’s subsequent use of fukkaku positions with devastating results at Peleliu, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa.[43]

The HORLICKS operations plan called for the 186th Infantry to secure the beachhead at Bosnek while the 162nd Infantry moved west along the coast road toward the Mokmer airfield some eight miles away. Although the 186th Infantry was supposed to land east of the 162nd Infantry, an unexpectedly strong current over the reefs carried some elements of the 186th Infantry west of the 162nd Infantry and dumped them in a mangrove swamp.[44] When the commander of the 186th Infantry asked if his regiment should simply switch roles with the 162nd Infantry, Fuller elected to stick with his initial plan.

Groups of steep coral ridges paralleled the coastal road between Bosnek and Mokmer. These ridges and cliffs were pockmarked by caves, often connected by tunnels, that served not only as living areas and supply dumps but also emplacements for artillery, automatic weapons, and mortars.[45] The worst section of the coast road included the Parai Defile, a set of seven steep ridges paralleling the coast, spaced roughly 50–75 yards apart and offering the Japanese an ideal defensive location.[46] Other topographical nightmares that the Americans faced on Biak included the West Caves (Kuzume’s headquarters, large enough to shelter a thousand men), the Ibdi Pocket, and the East Caves, portions of which, thanks to concrete reinforcement, withstood an astonishing degree of assault from aerial bombardment, naval gunfire, field artillery, heavy mortars, and tanks.[47] Kuzume placed his troops in positions that best guaranteed the opportunity to execute his mission of denying the airfields to the Americans as long as possible.[48] Thanks to the defender-friendly terrain, the “Japanese seemed to be everywhere, yet nowhere.”[49]

Once the 186th Infantry and 162nd Infantry had reorganized themselves after the landing snafu, the 186th Infantry set about setting up its beachhead. Unloading of troops, weapons, and equipment went well and all 12,000 Z-day troops were ashore by late afternoon, when unloading was halted due to the risk of Japanese air attack.[50] One of the anti-aircraft battalions that went immediately into action was the 476th Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion (Semimobile), which received the Distinguished Unit Citation for “extraordinary heroism” at Biak for destroying or damaging 24 attacking Japanese aircraft in its first week ashore.[51]

Meanwhile, the 162nd Infantry began its march westward on the coast road. Opting for speed, Fuller elected to march all three battalions of the 162nd Infantry along the coast road in lieu of splitting the battalions to send only one down the coast road with its flank protected by the other two battalions from an elevated inland plateau. The regiment encountered little response from the enemy until the spearhead battalion reached the Parai Defile, but tanks helped push the US infantry past Japanese resistance. On the morning of May 28, 3rd Battalion had drawn within 200 yards of the Mokmer airfield. At that point the Japanese attacked in strength, and the Americans’ ability to hold their ground deteriorated over the next 2 days. A Japanese attack early on May 29 erupted into one of the first tank-on-tank battles in the Southwest Pacific, with US General Sherman M4A1 medium tanks easily dispatching seven Japanese Model 95 Ha-Go light tanks in less than an hour.[52] But the 162nd Infantry had to pull back, requiring the spearhead battalion to be extracted by water.

5 Situation “Grave” – Send Reinforcements

At this point, Fuller, calling the situation “grave,” requested Krueger to send his third regiment, the 163rd Infantry, accompanied by a battalion of light artillery, a battalion of combat engineers, and another company of tanks.[53] Krueger, who had planned in advance to use the 163rd Infantry as reinforcements if necessary, promised to send two of the 163rd Infantry’s three battalions, but the other units were purportedly unavailable.[54] Fuller now realized that continuing to advance along the coast road was pointless unless the Japanese were cleared out of the defensive positions on the ridges overlooking the road and airfields. He withdrew the 162nd Infantry to almost where it had landed on Z-Day and waited for the arrival of the 163rd Infantry while the 162nd Infantry patrolled the ridges to determine enemy strength.

In an astonishing move that same day, MacArthur, from the comfort of his headquarters over 2,000 miles away in Brisbane, Australia, issued a communique that suggested that Biak had fallen. “For strategic purposes this marks the end of the New Guinea campaign …. The results of the offensive which was launched in this theater eleven months ago have more than fulfilled my most optimistic hopes and expectations.”[55] MacArthur sent congratulations to Krueger, Fuller, and every officer and soldier of their commands for the “brilliant success attained at Wadke and Biak.”[56] But the battle on Biak was far from won; rather, this was simply another instance of MacArthur’s pattern of closing the “public book on operations well before they were anywhere near finished.”[57]

When two battalions from the 163rd Infantry arrived on May 31, Fuller used them to relieve the 186th Infantry at the beachhead and implemented a new strategy that was simply an enlargement of his original alternate plan, but with regiments rather than battalions.[58] He sent the 162nd Infantry back down the coastal road but with their flank protected by 186th Infantry, which marched westward from Bosnek on trails that paralleled the coral ridges and then descended from the north onto the airfields. Krueger messaged Fuller that he was to push vigorously “with a view to carrying out your mission effectively and expeditiously.”[59] Although a large New York Times front-page headline on June 1 cautioned that “OUR FORCES ON BIAK ARE IN DIFFICULTY,” MacArthur announced on that same day that enemy resistance was “collapsing.”[60] Two days later he announced that troops were “mopping up” at Mokmer airfield.[61] Neither statement was entirely true.

The 186th Infantry encountered rough going on the trails, having to hack through scrub growth that was as high as 12 feet and blocked visibility.[62] Water was so scarce that men were rationed one canteen of water per day. Meanwhile, the 162nd Infantry tried unsuccessfully to get back through the Parai Defile but, even with the help of naval gunfire and a rocket Landing Craft Infantry, they were unable to break through.[63] Fuller ultimately just ordered landing craft pick up the 162nd Infantry (and three tanks) and deposit them ashore on the other side of the defile on June 7.

As the battle for the airfields ground to a yard-by-yard struggle to clear caves, MacArthur pressured Krueger for faster results. On June 5, MacArthur advised Krueger, “I am becoming concerned about the failure to secure the Biak airfields. Is the advance being pushed with sufficient determination? Our negligible ground losses would seem to indicate a failure to do so.”[64] Krueger replied that he had been prodding Fuller and that he was waiting for reports from his staff, whom he had dispatched to Biak.[65] Krueger wrote Fuller that same day that his progress was “very disturbing” and that it is “imperatively necessary that you push forward with the utmost energy and determination and gain your objective quickly.”[66]

Neither Krueger nor MacArthur ever visited Biak. Indeed, because MacArthur decided to move on to Biak so quickly, Krueger was left to juggle multiple campaigns simultaneously and felt it “vitally necessary” to remain at his command post in Hollandia.[67] Instead, Krueger twice sent colonels on his staff to assess the situation on Biak. The first visit was by the Sixth Army operations officer, Colonel Clyde Eddelman, who reported back to Krueger on June 1 that Fuller’s strategy was sound “and would succeed if carried out with aggressiveness and force.”[68]

When the 186th Infantry got within visual distance of the airfields on June 7, Fuller directed an immediate assault, which the battalion commander vehemently opposed because he wanted to clear the ridges first.[69] However, Fuller, feeling pressured by Krueger, ordered the 186th Infantry down the ridge to Mokmer – and right into a trap. The Japanese defenders unleashed a tirade of artillery, anti-aircraft, automatic weapons, and mortar fire, but after a 4-hour battle, the 186th Infantry held.[70] The Americans had seized a portion of Mokmer airfield by daybreak on June 8, but the field was unusable because Japanese defenders still held the surrounding higher ridges from which they lobbed mortar and artillery shells onto the runway.[71]

Krueger’s second inspector to report on Biak operations was Colonel George Decker, his chief of staff, who, on June 8, reported to Krueger that Fuller had seized one of Mokmer’s airstrips under extremely challenging conditions, including scarcity of water, temperatures over 100 degrees, imposing terrain, and formidable defenses.[72] Like Eddleman, Decker believed that Fuller would succeed by engaging in “strong, aggressive action.”[73] Decker’s report prompted Krueger to advise MacArthur in a three-page letter on June 8 that he had considered relieving Fuller when the initial attack failed on May 29, but felt that it would be unwarranted “now when, I’m sure, he is about to accomplish his mission successfully.”[74] As Eichelberger wrote his wife on June 9, “Horace [Fuller] had a pretty hard time for a while and Walter [Krueger] told me he had considered sending me in there to help. However, that is no longer necessary.”[75]

On the same date, Fuller wrote Krueger to elaborate on the difficulties the US troops were experiencing.[76] The caves and crevices that permitted the Japanese to attack and then recede had to be cleared one at a time. Once the entrances were discovered, naval gunfire – and even direct 75-mm tank fire – caused little damage except at the mouth of the caves.[77] If the Japanese could not be lured out of the caves, then US troops were forced to use flame-throwers to neutralize the entrance to the caves and then detonate copious amounts of TNT.

6 Fuller’s Relief

Although the 162nd Infantry was able to seize Borokoe airfield on June 11, it, too, was unusable due to continued Japanese presence in the ridges. As Krueger advised Fuller that day, “I again must urge you to liquidate hostile resistance with utmost vigor and speed to permit construction on Mokmer and other dromes to be undertaken. Since you have not reported your losses, it is assumed that they were not so heavy as to prohibit advance.”[78] Fuller requested another regiment on June 13, in large part because his troops had been in combat continuously for 17 days. He had also learned that the Japanese were landing reinforcements on Biak. Krueger disbelieved Fuller’s claim of Japanese reinforcements; rather, he concluded that Fuller simply could not handle duties both as task force commander and division commander.[79] Krueger did, however, order the 34th Infantry Regiment, 24th Division, from Hollandia to Biak.

Robert Ross Smith, SWPA historian, writes that SWPA assessments of the likelihood of Japanese reinforcements on Biak were “simply incorrect.”[80] It is certainly true that three efforts (KON-1, KON-2, KON-3) to reinforce Biak by sea had failed. But the Japanese still managed to transport approximately 1,200 infantry reinforcements to Biak by barges and native canoes from various locations around Geelvink Bay.[81] Most of these troops reached Biak prior to mid-June and were fed into Kuzume’s defensive positions to delay seizure of the airfields.[82]

On June 14, just hours before the Allied landing on Saipan was to start (and just over a week since Eisenhower made the front pages with the invasion of Normandy), MacArthur cabled Krueger an “eyes alone” message, writing “The situation at Biak is unsatisfactory. The strategic purpose of the operation is being jeopardized by the failure to establish without delay an operating field for aircraft.”[83] Krueger replied by advising MacArthur that he was ordering Eichelberger to replace Fuller as commander of HURRICANE Task Force. Eichelberger was “shocked” by the suddenness of Krueger’s decision.”[84]

Upon learning that Eichelberger was en route from Hollandia to assume command of the task force, Fuller tendered his request for relief as division commander. In his request, he wrote that it was “quite apparent” from Krueger’s “numerous messages” that Krueger was rebuking him for the slowness of operations on Biak and his failure to secure the Japanese airfields in the “allotted time.” Fuller maintained his relief was proof that “high command” considered his services as task force commander to have been “totally unsatisfactory.” He believed that his relief as task force commander jeopardized his value as division commander because his troops knew he had been relieved for failing to carry out his assigned task.[85]

Eichelberger’s Chief of Staff, Brigadier General Clovis Byers, tried to convince Fuller that with the addition of the fourth regiment, Allied operations on Biak were simply expanding into a corps-level operation. Fuller, who had reached his breaking point with Krueger, refused to retract his letter of resignation. As Eichelberger wrote his wife, “[Fuller] says he does not intend to serve under a certain man again if he has to submit his resignation every half hour by wire.”[86] Eichelberger had explained to his wife that the delay in seizing Biak was “principally terrain” but also Japanese units who were “well-rested combat troops who have fought back hard.”[87] He tried to convince Fuller to stay on as division commander by reminding him that MacArthur had promised to give Fuller command of a corps.[88] But Fuller told his old friend, “The dignity of man stands for something. I’ll take no more insulting messages.”[89]

Colonel Harold Riegelman, the I Corps chemical officer, similarly tried to convince Fuller to retract his resignation by pointing out that the division “idolized” Fuller and that “the boys” would understand the change in task force command was due to the increase in troops on Biak.[90] In response, Fuller simply stated that the division, knowing he had been “kicked out” as task force commander, would no longer be confident of his ability to lead them.[91] Fuller lamented, “From the beginning I begged and pleaded for one more regiment. I know what this operation needs. With one more regiment we’d have had the airdromes in operation a week ago. Now, they send in another regiment – but not to me.”[92] As Riegelman wished Fuller luck, Fuller replied, “Same to you. You’ll need it. I’m sure you’ll have it, with enough men to do a man-size job.”[93] Before he departed the island by destroyer on June 18, Fuller issued a letter to the officers and men of the 41st Division stating that he was relieved because of his failure to “achieve the results demanded by higher authority” and assuring the men that it was no reflection on their efforts during the operation; he alone was responsible for the failure.[94]

Krueger favorably endorsed Fuller’s request and directed Brigadier General Jens Doe to assume duties as acting commanding general of the division. MacArthur likewise approved the resignation request. Fuller traveled to Australia, where he underwent an appendectomy followed by a lengthy leave period in the United States.[95] In September 1944, Fuller received the Distinguished Service Medal for his service from April 6, 1942, until June 17, 1944. His citation stated that his “personal courage and inspiring leadership made possible the able execution of assigned missions.”[96] Fuller later returned to the Pacific theater, serving as Deputy Chief of Staff, to the Supreme Allied Commander, South East Asia Command (Lord Louis Mountbatten).

Eichelberger, who wrote in a coded letter to his wife that he would have roughly 29,000 troops at his disposal on Biak, spent 3 days assessing the tactical situation and then restarted offensive operations just as the 34th Infantry arrived.[97] His assault plan differed little from Fuller’s.[98] Historian Harry Gailey points out that Eichelberger’s “attack plans were roughly the same as Fuller’s had been” but Eichelberger now had four regiments and more tanks.[99] Roger Lawless, the Signal Corps officer who was present on Biak during HORLICKS, confirms this: “By 15 June, it was only a question of time… After acquainting himself with the situation, the I Corps commander employed the same forces in the same area and in much the same manner as [Fuller] had been using them.”[100] The high ground was secured by June 22, the same day that American fighters started operations from Mokmer airfield.[101] The three primary defensive points – the West Caves, East Caves, and Ibdi Pocket – were all taken through ferocious fighting by June 27, although “mopping up” continued until August 20.[102]

Eichelberger only remained on Biak until June 29, 1944, when he flew out of Mokmer back to Hollandia. In a meeting with Eichelberger, Krueger went into a rant against Fuller and blamed Eichelberger for Fuller’s request to be relieved of division command.[103] Eichelberger retorted by telling Krueger that Fuller had requested his own relief due to Krueger’s treatment toward him.[104] Although Eichelberger found flaws in his classmate’s performance at Biak, he thought Krueger had thrown Fuller under the proverbial tank tread, writing after the war that Fuller had been unfortunate in meeting a “regular regiment of Japanese infantry and there he brought down upon his devoted head the censure of his army commander.”[105]

7 Krueger’s Justification

In his 1953 history of the Sixth Army, Krueger provided the following explanation for why he relieved Fuller:

The slow progress of the operation and delay in gaining control and use of the airdromes had been so disturbing that I had dispatched several radiograms to the Task Force commander directing him to speed up the operation. But it was easier to order this than get it done, for after all the troops were faced by great difficulties. But when reports of lack of coordination at headquarters of Biak Task Force reached me and a radiogram from GHQ pointed out that the failure to secure the Biak airfields at an early date as directed was interfering with the execution of strategic plans, I came to the conclusion that the only way to accelerate the operation was to relieve General Fuller of the burden of commanding the Task Force and have him devote his whole attention to the tactical handling of his division.[106]

Krueger specified here two reasons for the relief: reports of the lack of coordination at headquarters and MacArthur’s radiogram. However, the first justification was a red herring. Krueger learned from Decker on June 8 that there was a lack of coordination at task force level yet advised MacArthur on that date that he was keeping Fuller in command. In fact, as late as June 13, Krueger, according to Eichelberger, was still “hoping that Horace will finish up his job on Biak.”[107]

Rather, it was MacArthur’s June 14 radiogram that sealed Fuller’s fate. MacArthur lamented that the “strategic purpose of the operation is being jeopardized by the failure to establish without delay an operating field for aircraft.” What strategic purpose MacArthur was referring to is unclear. If the strategic purpose of HORLICKS had been to obtain airfields from which to launch heavy bomber support to Nimitz at Saipan, that window was shut and sealed by June 14; carrier air and naval bombardment against Saipan had already commenced and heavy bombers from other US airfields had been pounding Truk, the main threat to US forces landing on Saipan.[108]

However, even if the “strategic purpose of the operation” was simply to wrap up in New Guinea and move on to the Philippines, MacArthur – aware that Krueger had already considered relieving Fuller two weeks before – provided the nudge that pushed Krueger over the edge. MacArthur’s premature announcements of victory meant that every day that delayed US air operations at Mokmer threatened both his reputation and his personal integrity.[109] He had even misled US Army Chief of Staff George Marshall, who in a personal message to MacArthur on June 9 called Biak a model of “strategical and tactical maneuvers.”[110] But MacArthur did not fool everyone. According to Eichelberger biographer Paul Chwialkowski, when the Australian press called out MacArthur for his “duplicity” in claiming on June 3 that operations on Biak were in the “mopping up” phase, the ensuing negative publicity placed MacArthur in a highly embarrassing position that “made him anxious to conclude the operation in the quickest possible manner.”[111] Moreover, he was almost certainly discomfited at failing to make good his pledge to Nimitz.[112] Likely prompted by a variety of motives, MacArthur put pressure on Krueger to close the chapter on Biak. Indeed, Eichelberger’s chief of staff Clovis Byers later stated, in an interview with MacArthur biographer D. Clayton James, that there was no question that MacArthur was pushing Krueger.[113]

Fuller had no control over what was likely one of the most critical contributors to his relief, that being the dynamic between MacArthur and Krueger. Krueger, who had expected to spend the war training troops, was in MacArthur’s debt for requesting him by name for an army command in SWPA.[114] Krueger, whom Byers described as a martinet, was also unduly sensitivity to criticism, a flaw that had earned him a personal counseling session from George Marshall earlier in the war.[115] Marshall had told Krueger in the spring of 1941 that he was troubled by Krueger’s sensitivity to suggestions and “to anything that you think might not reflect to the best advantage for you personally.”[116] This personality quirk likely increased his sensitivity to MacArthur’s impatience, and as MacArthur pressured Krueger, Krueger, in turn, pressured Fuller. By Krueger’s own admission, MacArthur was the “needle from behind.”[117]

8 Fuller’s Relief – A “Great Injustice”

In the words of Colonel Leland Lewis, who served as a non-commissioned officer in the 186th Infantry on Biak in 1944, General Fuller had been “asked to do something he wasn’t given the tools to do.”[118] The Japanese defenses on Biak were the best yet faced by American forces in SWPA, with the Japanese demonstrating what one US Army officer on Biak later described as “superb infiltration techniques and the masterly use of individual features of terrain.”[119] Fuller needed his full division on May 27, not just two-thirds of it. But given the troops at his disposal, Fuller’s performance at Biak, although flawed in some respects, was overall sound; Eichelberger not only acknowledged as such but built on Fuller’s strategy with the four regiments that afforded him concentration of mass.[120]

Fuller made some tactical decisions that are easy to criticize in hindsight, including his June 6 orders to the 186th Infantry to seize Mokmer airfield without first clearing the ridges; however, this decision was almost certainly attributable to Fuller responding to Krueger’s prodding to move faster. At the same time, Fuller has received little credit for his creative use of small craft along the shoreline at Biak. At various points in his time as task force commander, he used amphibious tractors and landing craft to evacuate the spearhead battalion of the 162nd Infantry on May 28; to bypass the Parai Defile with troops and tanks; to resupply US forces at Mokmer; and to evacuate the wounded.[121]

Robert Ross Smith writes that the issue over Fuller’s relief is “a question which cannot be answered categorically.”[122] The primary commentator who supports Fuller’s relief is Kevin Holzimmer, Krueger’s biographer, who questions Fuller’s tactics and leadership.[123] Most commentators, however, conclude that Krueger was not justified in relieving Fuller. Harry Gailey maintains that MacArthur and Krueger “bungled” the Biak operation and simply passed off the blame to Fuller, a “fully competent commander” whose relief was “a great injustice.”[124] Edward Drea maintains that MacArthur stuck with an unrealistic timetable due to inaccurate intelligence on Japanese troop strength on Biak as well as his compulsion to return to the Philippines.[125]

9 Summary

Given that as late as June 13, Krueger planned to keep Fuller in task force command, Fuller would likely have remained as task force commander and secured the three airdromes if MacArthur had not “needled” Krueger “from behind” on June 14 with the radiogram containing the broad allegation that delay was interfering with strategic plans. As Eichelberger summarizes MacArthur’s well-known intolerance for delay, “MacArthur wanted results and quick ones. He was always impatient with failures to win objectives.”[126] In the end, MacArthur’s timetable trumped all else. As Stephen Taaffe concludes, “Fuller failed because he could not win the Biak battle the way MacArthur wanted it won – fast.”[127]

Biak Island Operation, 27 May–20 August 1944.

Source: U.S. Army Center of Military History, Reports of General MacArthur, The Campaigns of Macarthur in the Pacific) I:154 (Plate No. 43). Available at https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/MacArthur%20Reports/MacArthur%20V1/ch06.htm.

The Parai Defile.

Source: Robert Ross Smith, The Approach to the Philippines, United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, Washington, DC, 1984. Available at https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USA/USA-P-Approach/img/USA-P-Approach-p314.jpg.

-

Conflict of interest: Author states no conflict of interest.

References

Adams, John A. If Mahan Ran the Great Pacific War: An Analysis of World War II Naval Strategy. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2008.Suche in Google Scholar

Alexander, Joseph H. Storm: Epic Amphibious Battles in the Central Pacific. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 1997.Suche in Google Scholar

Bleakley, Jack. The Eavesdroppers. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1992.Suche in Google Scholar

Borneman, Walter R. MacArthur at War: World War II in the Pacific. Little, Brown, New York, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

Chwialkowski, Paul. In Caesar’s Shadow: The Life of General Robert Eichelberger. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 1993.10.5040/9798216974215Suche in Google Scholar

Costello, John. The Pacific War. Quill, New York, 1982.Suche in Google Scholar

Craven, Wesley Frank and James Lea Crate. The Army Air Forces in World War II. University of Chicago Press, 1950. Reprint, Office of Air Force History, Washington, DC, 1983.Suche in Google Scholar

Drea, Edward J. “A Tale of Too Many Chiefs.” World War II (December 2006), 42–47.Suche in Google Scholar

Drea, Edward J. MacArthur’s ULTRA: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942–1945. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, 1992.Suche in Google Scholar

Drea, Edward J. New Guinea: The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. U.S. Army Center for Military History, Washington, D.C., n.d.Suche in Google Scholar

Duffy, James P. War at the End of the World: Douglas MacArthur and the Forgotten Fight for New Guinea, 1942–1945. NAL Caliber, New York, 2016.Suche in Google Scholar

Eichelberger, Robert L. Our Jungle Road to Tokyo. Nashville, TN: Battery Classics, Nashville, TN, 1989.Suche in Google Scholar

Gailey, Harry A. “MacArthur, Fuller and the Biak Episode.” The U.S. Army and World War II: Selected Papers from the Army’s Commemorative Conferences, Judith L. Bellafaire, ed. U.S. Army Center for Military History, Washington, D.C., 1998, 303–316.Suche in Google Scholar

Gailey, Harry A. MacArthur’s Victory: The War in New Guinea, 1943–1944. Presidio Press, Novato, CA, 2004.Suche in Google Scholar

Griffith, Thomas E. Griffith, Jr., MacArthur’s Airman: General George C. Kenney and the War in the Southwest Pacific. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, 1998.Suche in Google Scholar

Holzimmer, Kevin C. General Walter Krueger: Unsung Hero of the Pacific War. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

James, D. Clayton. The Years of MacArthur. Vol. 2, 1941–45. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1975.Suche in Google Scholar

Jordon, David M. FDR, Dewey and the Election of 1944. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2011.Suche in Google Scholar

Kluckhohn, Frank L. Leap to Schoutens: Americans Storm Ashore on Biak but Meet Fierce Resistance. New York Times, May 28, 1944.Suche in Google Scholar

Kluckhohn, Frank L. Our Forces on Biak are in Difficulty. New York Times, June 1, 1944.Suche in Google Scholar

Krueger, Walter. From Down Under to Nippon: The Story of the Sixth Army in World War II. Battery Classics, Nashville, TN, 1989.Suche in Google Scholar

Lawless, Roger E. “The Biak Operation.” Part One. Military Review, vol. 33, no. 2 (May 1953): 53–62.Suche in Google Scholar

Lawless, Roger E. “The Biak Operation.” Part Two. Military Review, vol. 33, no. 3 (June 1953): 48–62.Suche in Google Scholar

Leary, William M. “Walter Krueger: MacArthur’s Fighting General.” In We Shall Return! MacArthur’s Commanders and the Defeat of Japan, 1942–1945, ed. William M. Leary, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 1988.Suche in Google Scholar

Luvaas, Jay, ed. Dear Miss Em: General Eichelberger’s War in the Pacific, 1942–1945. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 1972.Suche in Google Scholar

Luvaas, Jay and John F. Shortal. “Robert L. Eichelberger: MacArthur’s Fireman.” In We Shall Return! MacArthur’s Commanders and the Defeat of Japan, 1942–1945, ed. William M. Leary, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 1988.Suche in Google Scholar

MacArthur, Douglas. Reminiscences. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 1964.Suche in Google Scholar

McCarten, John. “General MacArthur: Fact and Legend,” The American Mercury, vol. 58, no. 241 (January 1944): 7–18.Suche in Google Scholar

McCartney, William F. The Jungleers: A History of the 41st Infantry Division. Washington: Infantry Journal Press, Washington, DC, 1948.Suche in Google Scholar

McManus, John C. Fire and Fortitude: The U.S. Army in the Pacific War, 1941–1943. Dutton Caliper, New York, 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

McManus, John C. Island Infernos: The U.S. Army’s Pacific War Odyssey, 1944. Dutton Caliper, New York, 2021.Suche in Google Scholar

Morison, Samuel Eliot. New Guinea and the Marianas: March 1944–August 1944. Vol. 8 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 2002.Suche in Google Scholar

Perry, Mark. The Most Dangerous Man in America: The Making of Douglas MacArthur. Basic Books, New York, 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

Perret, Geoffrey. Old Soldiers Never Die: The Life of Douglas MacArthur. Random House, New York, 1996.Suche in Google Scholar

Prefer, Nathan. MacArthur’s New Guinea Campaign: March–August 1944. Combined Books, Conshohocken, PA, 1995.Suche in Google Scholar

Riegelman, Harold. Caves of Biak: An American Officer’s Experiences in the Southwest Pacific. Dial Press, New York, 1955.Suche in Google Scholar

Rottman, Gordon L. World War II Pacific Island Guide: A Geo-Military Study. Greenwood Press, Westport, CT, 2002.Suche in Google Scholar

Salecker, Gene E. Rolling Thunder Against the Rising Sun: The Combat History of the U.S. Army Tank Battalions in the Pacific in World War II. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2008.Suche in Google Scholar

Shortal, John F. Forged by Fire: Robert L. Eichelberger and the Pacific War. University of South Carolina, Columbia, 1987.Suche in Google Scholar

Spector, Ronald H. Eagle Against the Sun. Free Press, New York, 1985.Suche in Google Scholar

Smith, Robert Ross. The Approach to the Philippines, 50th Anniversary Commemorative Edition. United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific. Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, Washington, DC, 1984.Suche in Google Scholar

Taaffe, Stephen R. MacArthur’s Jungle War: The 1944 New Guinea Campaign. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, 1998.Suche in Google Scholar

Taaffe, Stephen R. Marshall and his Generals: U.S. Army Commanders in World War II. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, 2011.10.1353/book46023Suche in Google Scholar

Turpin, J. G., Murray, J. F., Schenk, D. F., Wray, T., and Stanfield, C. D. Biak Island: A Battlebook. U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, KS, 1983.Suche in Google Scholar

U.S. War Department, Military Intelligence Division. “Intelligence Bulletin,” vol. III, no. 3, Nov. 1944.Suche in Google Scholar

Watson, Robert Meredith. Seahorse Soldiering: MacArthur’s Amphibian Engineers from New Guinea to Nagoya. Xlibris.com, 2003.Suche in Google Scholar

Westerfield, Hargis. 41st Infantry Division Fighting Jungleers II. Turner Publishing, Paducah, KY, 1992.Suche in Google Scholar

Weintraub, Stanley. Final Victory: FDR’s Extraordinary World War II Presidential Campaign. DaCapo Press, Boston, 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2022 Mary T. Hall, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Transformation of Polish Military Administration in the First Half of Seventeenth Century – Ideas and its Realization

- Beyond the Standards of the Epoch – The Phenomenon of Elżbieta Sieniawska Née Lubomirska and Anna Katarzyna Radziwiłł née Sanguszko based on Selected Aspects of Their Economic Activities in Times of Political Unrest in the Saxon Era

- China’s People’s Liberation Army: Restructuring and Modernization

- “A vast and efficient organism” – Admiral Chester W. Nimitz and the art of command

- Difficult alliance. Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Russia against Sweden during the Great Northern War (1700–1721) – an introduction to the problematic

- It all began at Pearl Harbor. The Allied-Japanese Struggle in the Pacific, ed. by John T. Kuehn

- It All Began at Pearl Harbor…

- Pearl Harbor in Context

- The Optics of MAGIC: FDR’s 1941 SIGINT Stumbles and Japan’s Hidden Plans for America (1940–1941)

- Langley’s Great Escape

- Advanced Base Defense Doctrine, War Plan Orange, and Preparation at Midway: Were the Marines Ready?

- American peacetime naval aviation and the Battle of Midway

- MacArthur’s need for speed: Why Fuller was fired at Biak

- Controversial Victory: The “Tanker War” Against Japan, 1942–1944

- 1821 – A New Dawn for Greece. The Greek Struggle for Independence, ed. by Lucien Frary

- 1821 – A New Dawn for Greece. The Greek Struggle for Independence – Contents

- Introduction - 1821 – A new dawn for Greece: The Greek struggle for independence

- Defining a Hellene. Legal constructs and sectarian realities in the Greek War of Independence

- Russian military perspectives on the Ottoman Empire during the Greek War of Independence

- “Little Malta”: Psara and the Peculiarities of naval warfare in the Greek Revolution

- Policing a revolutionary capital: Public order and population control in Nafplio (1824–1826)

- Konstantinos Oikonomos and Russian Philorthodox relief during the Greek war for independence (1821–1829)

- The geopolitics of the 1821 Greek Revolution

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Transformation of Polish Military Administration in the First Half of Seventeenth Century – Ideas and its Realization

- Beyond the Standards of the Epoch – The Phenomenon of Elżbieta Sieniawska Née Lubomirska and Anna Katarzyna Radziwiłł née Sanguszko based on Selected Aspects of Their Economic Activities in Times of Political Unrest in the Saxon Era

- China’s People’s Liberation Army: Restructuring and Modernization

- “A vast and efficient organism” – Admiral Chester W. Nimitz and the art of command

- Difficult alliance. Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Russia against Sweden during the Great Northern War (1700–1721) – an introduction to the problematic

- It all began at Pearl Harbor. The Allied-Japanese Struggle in the Pacific, ed. by John T. Kuehn

- It All Began at Pearl Harbor…

- Pearl Harbor in Context

- The Optics of MAGIC: FDR’s 1941 SIGINT Stumbles and Japan’s Hidden Plans for America (1940–1941)

- Langley’s Great Escape

- Advanced Base Defense Doctrine, War Plan Orange, and Preparation at Midway: Were the Marines Ready?

- American peacetime naval aviation and the Battle of Midway

- MacArthur’s need for speed: Why Fuller was fired at Biak

- Controversial Victory: The “Tanker War” Against Japan, 1942–1944

- 1821 – A New Dawn for Greece. The Greek Struggle for Independence, ed. by Lucien Frary

- 1821 – A New Dawn for Greece. The Greek Struggle for Independence – Contents

- Introduction - 1821 – A new dawn for Greece: The Greek struggle for independence

- Defining a Hellene. Legal constructs and sectarian realities in the Greek War of Independence

- Russian military perspectives on the Ottoman Empire during the Greek War of Independence

- “Little Malta”: Psara and the Peculiarities of naval warfare in the Greek Revolution

- Policing a revolutionary capital: Public order and population control in Nafplio (1824–1826)

- Konstantinos Oikonomos and Russian Philorthodox relief during the Greek war for independence (1821–1829)

- The geopolitics of the 1821 Greek Revolution